AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING, 2022

VOLUME ELEVEN NUMBER TWO

ROSCOE MITCHELL

MORGAN GUERIN

(March 18-24)

KENNY KIRKLAND

(March 26-APRIL 1)

STACEY DILLARD

(April 2-8)

CHARENÉE WADE

(April 9-15)

JAMAEL DEAN

(April 16-22)

BRUCE HARRIS

April 23-29)

BENJAMIN BOOKER

(April 30-May 7)

UNA MAE CARLISLE

(May 7-13)

JUSTIN BROWN

(May 14-20)

TYLER MITCHELL

(May 21-27)

SONNY SHARROCK

(May 28-June 3)

CHRIS BECK

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/sonny-sharrock-mn0000036987/biography

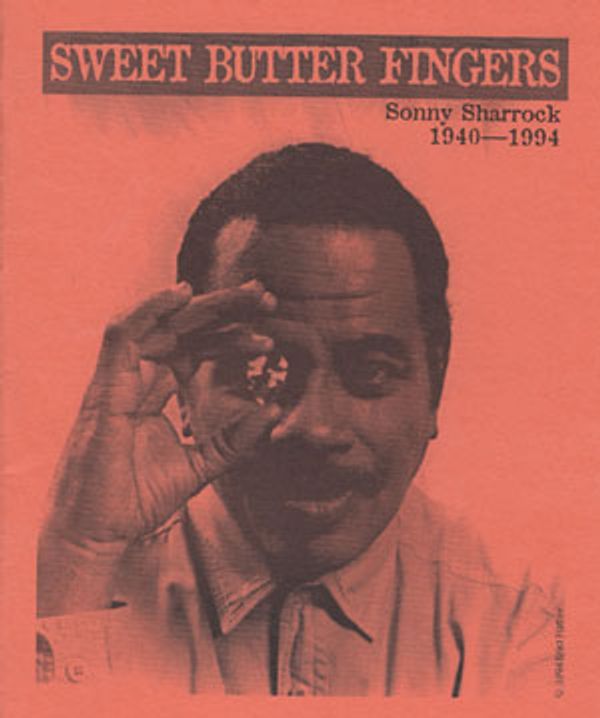

Sonny Sharrock

(1940-1994)

Artist Biography by Steve Huey

Of the electric guitar's few proponents in avant-garde jazz, Sonny Sharrock is easily the most influential; he was one of the earliest guitarists to even attempt free playing, along with Derek Bailey and Sonny Greenwich. Sharrock's visceral aggression and monolithic sheets of noise were influenced by the screaming overtones of saxophonists like Coltrane, Sanders, and Ayler, and his experiments with distortion and feedback predated even Jimi Hendrix. Naturally, he provoked much hostility among traditionalists, but once his innovations were assimilated, he enjoyed wide renown in avant-garde circles.

Born Warren Harding Sharrock in Ossining, NY, in 1940, he began singing in doo wop groups in 1953. He fell in love with jazz through Kind of Blue, but took up guitar (in 1960) instead of saxophone because of his asthma. In 1965 -- four years after a failed stint at Berklee -- he moved to New York, where he first worked with Byard Lancaster and Babatunde Olatunji. He made his recording debut in late 1966 on Pharoah Sanders' Tauhid, and remained with Sanders until 1968; he subsequently joined Herbie Mann's group, where his wild freakouts clashed -- often intriguingly -- with the flautist's accessible leanings. Sharrock's first recordings as a leader, 1969's Black Woman and 1970's Monkey-Pockie-Boo, featured his wife Linda's swooping wordless vocals. In 1970, Sharrock turned down an audition with Miles Davis, feeling that his seismic, uncredited solo on A Tribute to Jack Johnson spoke for itself; unfortunately, the result was years of obscurity after he exited Mann's group around 1972. Fortunately, producer/bassist Bill Laswell invited Sharrock to join the avant-punk-jazz supergroup Last Exit in 1986. Laswell also produced the majority of a series of albums documenting Sharrock at his most unfiltered (1986's unaccompanied Guitar, 1987's Seize the Rainbow, 1990's Highlife, and the Nicky Skopelitis duet album Faith Moves). 1991's Ask the Ages was Sharrock's masterpiece, reuniting him with Pharoah Sanders and capturing his visceral and melodic sides. Sadly, though, just as he was becoming popular with adventurous young rock fans, Sharrock died of a heart attack in May 1994; his last recordings were for the animated series Space Ghost Coast to Coast.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/sonny-sharrock

Sonny Sharrock

The career of the late Sonny Sharrock is unique in modern jazz. He first aspired as a doo-wop singer, determined to take music as his vocation after listening to Miles Davis' “Kind of Blue.” Aspired to play saxophone but instead took up guitar in his early 20's due to asthmatic conditions, nonetheless he emulated his guitar styling after the energy players such as Coltrane and Pharaoh Sanders. He appeared as a cameo in Mile Davis' “Jack Johnson” album and Wayne Shorter's “Super Nova” album as well. His most notable appearance was his duel with Sanders on “Taulid” and “Izipho Zam.” His primal tone with gusto was indeed a one-of-a-kind. Although his didn't employ massive distortion to create the full-on blast, Sharrock's buzz saw lines with slamming dissonant chords were definite a character in the late '60s free jazz scene.

After playing free jazz with Pharoah Sanders, while he was playing funk-jazz with Herbie Mann, guitarist Warren “Sonny” Sharrock recorded three albums with his wife Linda Sharrock's wordless vocals: “Black Woman,” ( 1969), featuring the first version of his signature tune “Blind Willy,” “Monkey-Pockie-Boo,” (1970), possibly his most personal album; and Paradise (1975), introducing electronic keyboards in the sound of the couple and emphasizing Linda's vocal workouts, an avant-funk experiment that predated the new wave of rock music. The background of his guitar playing was fundamentally the blues, but at the same time he displayed a loud, aggressive, feedback-laden, quasi heavy-metal technique.

For six years Sharrock did not make a single record. It was bassist Bill Laswell, a protagonist of the new wave, who rediscovered him for Material's “Memory Serves.” (1981) “Dance with Me Montana,” (1982), not released until 1986, contained embryonic versions of his classics.

Laswell also organized Last Exit, an avant-funk quartet with Sharrock, German saxophonist Peter Brotzmann and drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson that played virulent jazz- rock, influenced by both the brutal edge of punk-rock and the cerebral stance of the new wave. Laswell was the brain, but Sharrock was the epitome: Last Exit played the kind of loud, savage jazz-rock and free jazz that Sharrock had pioneered. The catch, of course, was that Laswell had put together four mad improvisers, ranging from the cacophonic Brotzmann to the hysterical Sharrock to Laswell's dub bass. “Last Exit,” (1986) was a set of totally improvised jams, with frantic peaks, but pale in comparison with the live “Koln.” (1986) The other Last Exit live recording, “The Noise of Trouble,” (1986) was a humbler study in contrasts.

Sharrock overdubbed himself for the solo “Guitar,” (1986), achieving both his most challenging technique and emotional pathos. He then partnered with rock bassist Melvin Gibbs and drummer Pheeroan Aklaff for “Seize the Rainbow,” (1987) that attempted a fusion of heavy metal and fusion jazz.

In the meantime, Last Exit's punk-jazz achieved a different kind of intensity on “The Iron Path,” (1988) a set of ten short pieces, and the live “Headfirst Into The Flames.” (1989)

Sharrock also played on two albums by Machine Gun, a free-form improvising group, “Machine Gun,” (1988) and “Open Fire,” (1989). The duets of “Faith Moves,” (1990) with rock guitarist Nicky Skopelitis (on several different stringed instruments) sounded like an indulgent version of Guitar. A synthesizer and inferior material plagued “Highlife.” (1990).

A quartet with two free-jazz veterans, Pharoah Sanders and Elvin Jones, on “Ask the Ages,” (1991) restored Sharrock's status as a unique guitarist and composer and pushed it to new insane heights. This is Sonny Sharrock's masterpiece, and sadly it was also the last album he would record before his premature death in 1994.

Source: James Nadal

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonny_Sharrock

Sonny Sharrock

Warren Harding "Sonny" Sharrock (August 27, 1940 – May 25, 1994)[1] was an American jazz guitarist. He was married to singer Linda Sharrock, with whom he recorded and performed.

One of few guitarists in the first wave of free jazz in the 1960s, Sharrock was known for his heavily chorded attack, his highly amplified bursts of feedback, and his use of saxophone-like lines played loudly on guitar.

Biography

Early life and career

He was born in Ossining, New York, United States.[1] Sharrock began his musical career singing doo wop in his teen years.[1] He collaborated with Pharoah Sanders and Alexander Solla in the late 1960s, appearing first on Sanders's 1966 album, Tauhid.[1] He made several appearances with flautist Herbie Mann,[1] and an uncredited appearance on Miles Davis's A Tribute to Jack Johnson.

He wanted to play tenor saxophone from his youth after hearing John Coltrane on Davis's Kind of Blue on the radio at age 19, but his asthma prevented this. Sharrock said repeatedly, however, that he still considered himself "a horn player with a really fucked up axe."[2]

Three albums under Sharrock's name were released in the late 1960s through the mid-1970s: Black Woman[1] (which has been described by one reviewer as bringing out the beauty in emotions rather than technical prowess), Monkey-Pockie-Boo, and an album co-credited to both Sharrock and his wife, Paradise (an album by which Sharrock was embarrassed and stated several times that it was not good and should not be reissued).[3][4]

Career revival

After the release of Paradise, Sharrock was semi-retired for much of the 1970s, undergoing a divorce from his wife and occasional collaborator Linda in 1978. In the intermittent years until bassist Bill Laswell coaxed him out of retirement, he worked as both a chauffeur and a caretaker for mentally challenged children. At Laswell's urging, Sharrock appeared on Material's (one of Laswell's many projects) 1981 album, Memory Serves. In addition, Sharrock was a member of the punk/jazz band Last Exit, with Peter Brötzmann, Laswell and Ronald Shannon Jackson.[1] During the late 1980s, he recorded and performed extensively with the New York-based improvising band Machine Gun, as well as leading his own bands. Sharrock flourished with Laswell's help, noting in a 1991 interview that "the last five years have been pretty strange for me, because I went twelve years without making a record at all, and then in the last five years, I've made seven records under my own name. That's pretty strange."[5]

Laswell would often perform with the guitarist on his albums, and produced many of Sharrock's recordings, including the entirely solo Guitar, the metal-influenced Seize the Rainbow, followed by one of his more universally accessible albums, High Life. Sonny was quoted as saying that this was his favorite band ever, with Abe Speller on drums, Lance Carter on drums, Charles Baldwin on bass and David Snider on keyboards. This was followed by the well-received Ask the Ages, which featured John Coltrane's bandmates Pharoah Sanders and Elvin Jones. "Who Does She Hope To Be?" is a lyrical piece harkening back to the Coltrane/Davis Kind of Blue sessions that had inspired him to play. One writer described Ask the Ages as "hands down, Sharrock's finest hour, and the ideal album to play for those who claim to hate jazz guitar."[6] Sharrock is also known for the soundtrack to the Cartoon Network program Space Ghost Coast to Coast with his drummer Lance Carter, one of the last projects he completed in the studio before his death.[1] The season 3 episode "Sharrock" carried a dedication to him at the end, and previously unheard music that he had recorded for the show featured throughout most of the episode. "Sharrock" premiered as the 23rd episode on March 1, 1996 on Cartoon Network.

Death

On May 26, 1994, Sharrock died of a heart attack in his hometown of Ossining, New York, on the verge of signing the first major label deal of his career.[1] He was 53.[1]

Tributes

French guitarist Noël Akchoté's 2004 album Sonny II features tracks written, performed and inspired by Sharrock. In August 2010, S. Malcolm Street in Ossining was officially renamed "Sonny Sharrock Way".[7][8] A sign was erected on Saturday, October 2, 2010.[9] Sharrock was also inducted into Ossining High School's Hall of Fame.

Discography

As leader

- 1969: Black Woman (Vortex)

- 1970: Monkey-Pockie-Boo (BYG Actuel)

- 1975: Paradise (Atco)

- 1982: Dance with Me, Montana (Marge)

- 1986: Guitar (Enemy)

- 1987: Seize the Rainbow (Enemy)

- 1989: Live in New York (Enemy)

- 1990: Highlife (Enemy)

- 1991: Faith Moves (CMP) duo with Nicky Skopelitis

- 1991: Ask the Ages (Axiom)

- 1996: Space Ghost Coast to Coast (Cartoon Network)

- 1996: Into Another Light (Enemy) compilation

With Last Exit

- Köln (ITM, 1990)

- Last Exit (Enemy, 1986)

- The Noise of Trouble (Enemy, 1986)

- Cassette Recordings '87 (Enemy, 1987)

- Iron Path (Venture, 1988)

- Headfirst into the Flames: Live in Europe (MuWorks, 1993)

As sideman

With Ginger Baker

No Material (1989) record in 1987

- Think About Brooklyn (Delabel DE 391 382, 1993)

With Pheeroan akLaff

- Sonogram (Mu Works, 1989)

With Roy Ayers

- Daddy Bug (Atlantic, 1969)

With Ginger Baker

- No Material (ITM, 1989)

With Brute Force

- Brute Force (Embryo, 1970)

With Don Cherry

- Eternal Rhythm (MPS, 1968)

With Miles Davis

- A Tribute to Jack Johnson (Columbia, 1970)

- The Complete Jack Johnson Sessions (Columbia, 1970 [2003])

With Green Line

- Green Line (Nivico, 1970) with Steve Marcus, Miroslav Vitous and Daniel Humair

With Byard Lancaster

- It's Not Up to Us (Vortex, 1966 [1968])

With Machine Gun

- Machine Gun (Mu, 1988)

- Open Fire (Mu, 1989)

With Herbie Mann

- Windows Opened (Atlantic, 1968)

- The Inspiration I Feel (Atlantic, 1968)

- Memphis Underground (Atlantic, 1969)

- Concerto Grosso in D Blues (Atlantic, 1969)

- Live at the Whisky a Go Go (Atlantic, 1969)

- Stone Flute (Embryo, 1970)

- Memphis Two-Step (Embro, 1970)

- Herbie Mann '71 (Embryo, 1971)

- Hold On, I'm Comin' (Atlantic, 1973)

With Material

- Memory Serves (Celluloid, 1981)

With Pharoah Sanders

- Tauhid (Impulse!, 1966)

- Izipho Zam (My Gifts) (Strata-East, 1969 [1973])

With Wayne Shorter

- Super Nova (Blue Note, 1969)

With The Stalin

- Fish Inn (1986 Mix) (Tokuma Onkou, 1986)

With Marzette Watts

- Marzette Watts and Company (ESP-Disk, 1966)

External links

- Bill Laswell discography (includes profiles on Laswell-produced Sharrock projects)

- Ossining, New York profile

How Avant-Guitar Godfather Sonny Sharrock Reconciled Terror and Beauty

Get a fuller picture of the sui generis six-stringer seen playing a fiery, unforgettable solo in new Summer of Soul doc

PHOTO: Sonny Sharrock, right, onstage with Pharoah Sanders in 1968. Philippe Gras/LePictoriu/Newscom/MEGA

"I don't like guitar," Sharrock once told an interviewer. "I've always been influenced by horn players."

“With black musical expression, there’s a certain kind of release and catharsis,” the critic and musician Greg Tate says in the film, contextualizing the Sharrock clip. “There’s also rage; there’s also trauma. This notion of spirit possession from Africa gets translated into this horrific American experience. The artists connect with the pain. It’s like, ‘Yeah … I want you to feel who Sonny Sharrock really is right now.'”

Watching the film, you do feel who Sonny Sharrock really was, in the most visceral way, but after checking out this brief episode, you might be curious to learn more. He can be a hard figure to get a handle on, partly because any one glimpse of the guitarist — who died of a heart attack in 1994, at age 53 — tended to give you only a fragmentary idea of his artistic identity. On one hand, Sharrock was a staunchly perverse player, whose fierce, trilling right-hand attack (“the buzzsaw, the rip,” he once called it) and stun-blasts of cacophony were his way of emulating the free-jazz saxophone pioneers such as John Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders, and Albert Ayler who were his greatest musical heroes. (In a 1989 interview with Ben Ratliff, Sharrock explained that he initially chose guitar over tenor saxophone only because he had asthma. “I’m a tenor player, man. I’ve always thought of myself as one,” Sharrock added. “I don’t like guitar, I don’t like it at all, and I’ve always been influenced by horn players.”)

But much like Ayler, Coltrane, and Sanders — with whom Sharrock made his recorded debut, on 1967’s Tauhid — the guitarist also had a deep fascination with soul-stirring melody. He grew up singing doo-wop, and his first album as a leader, 1970’s Black Woman, which featured his then-wife Linda on alternately soothing and shrieking vocals, featured its share of folky, hummable themes. The producer of that album was Mann, the jazz-meets-R&B flutist in whose otherwise amiable-sounding band Sharrock served as a welcome fly in the ointment for several years in the late Sixties and early Seventies; asked about his fondness for Sharrock, Mann once said, “Lots of people say they can’t understand how Sonny Sharrock can be in my band. The only reason for them saying that is: possibly they think that when you’re a bandleader you expect all your children to be brought up in your exact image. Which just shows that people and critics don’t know anything about individuals.”

In this same period, Sharrock also recorded with Roy Ayers and Wayne Shorter, and made an uncredited appearance on Miles Davis’ early fusion landmark Jack Johnson. And from the mid-Eighties through the early Nineties — when he often gigged with saxophonist Peter Brötzmann, bassist Bill Laswell, and drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson in the brilliantly boorish noise-jazz supergroup Last Exit — he was riffing on gemlike original tunes on his revelatory multi-tracked solo album Guitar and flirting with glossy pop on the charming Sonny Sharrock Band release Highlife.

The stunning clip below, a full live set recorded in Prague in 1990, features a double-drum quintet similar to the one heard on Highlife, but with the great Melvin Gibbs, later of the Rollins Band and Harriet Tubman, on bass. On pieces like “My Song,” from 1987’s high-energy Seize the Rainbow, and a medley of “Venus”/”Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt,” two Sanders works that Sharrock had played on Tauhid, you can hear Sharrock relishing the contrast between the bright, hopeful compositions and the stormy turbulence of his trademark buzzsaw solos.

In a 1991 New York Times interview, Sharrock reflected on his omnivorous sonic appetite.

“In the last few years, I’ve been trying to find a way for the terror and the beauty to live together in one song,” he said. “I know it’s possible. I remember seeing John Coltrane standing there, his saxophone screaming, hearing the Flamingos sing at the Apollo. All that pretty music! I hope I’m as greedy as those musicians were. I want the sweetness and the brutality, and I want to go to the very end of each of those feelings.”

Sharrock would harness all of that — the terror and the beauty, the sweetness and the brutality — on the final album he released before his death, the Laswell-co-produced Ask the Ages, a powerhouse quartet session featuring his old friend Pharoah Sanders, former Coltrane drummer Elvin Jones, and bassist Charnett Moffett. It’s a gorgeously varied set that ventures from the white-hot heavy-metal bebop of opener “Promises Kept” to the hushed lyricism of “Who Does She Hope to Be?,” the lowdown doom-blues of “Many Mansions” (a reprise of a theme Sharrock first played with saxophonist Byard Lancaster on 1968’s It’s Not Up to Us), and the sky-kissing melodic shred of “Once Upon a Time.” As Andy Cush put it in a deep, insightful Pitchfork Sunday Review of Ask the Ages published this past April, the album found Sharrock “in the best form of his life, playing with impossible tenderness on one tune and unbearable force on the next.”

Given Sharrock’s range, it’s not surprising that he’s inspired musicians across the musical spectrum. He has fans in exploratory contemporary artists from free-spirited guitarist Ryley Walker to ecstatic punk-jazzers Sunwatchers; Living Colour’s Vernon Reid, who has called him a “massive [influencer] of alternative & outsider guitar”; Thurston Moore, who paid homage to Sharrock after the guitarist’s death on an episode of eccentric cartoon talk show Space Ghost Coast to Coast (which featured an outer-limits blues-rock theme song by Sharrock); and Carlos Santana, who has covered Sharrock live and was set to work with him before Sharrock’s passing. Speaking to Premier Guitar in 2016, Santana summed up Sharrock’s achievement — the way, as Greg Tate noted, he made us feel the totality of who he was in every cathartic outburst — and, just as importantly, the freeing effect it could have on those who paid witness.

“Sonny — I would call him a liberator,” Santana said. “If you really listen, artists like that can liberate you from your own fear. He’s like Coltrane — he’s the cosmic lion. And when he roars he wakes people up from the nightmare of feeling limited and unworthy.”

Sharrock (1940-1994) is an interesting piece of the jazz puzzle. He was the first and for the longest time the only guitarist working in the area of free jazz. Though his day job in the late '60s was playing in Herbie Mann's band, his work with Pharoah Sanders, notably on Tauhid, found him really cutting loose, showing a certain genius for creating sound sheets of blistering noise with bop-styled runs. At this point in his life, Sharrock used feedback to duplicate the rips from the brass men he played with, before Jimi Hendrix and Pete Townsend would make it fashionable in the mainstream. His early records as a leader are solid, but he really came together in the '80s when, surprisingly enough the players who were influenced by him began to be noticed in the downtown New York scene. The unaccompanied Guitar (1986) and Seize the Rainbow (1987) were shocking in their unabashed genius, but his last record, Ask the Ages, is unquestionably the greatest achievement of his entire career.

Teaming back up with Sanders, Sharrock does not waste a single note on this record. He summons both his forward sonic attack and a beautifully melodic side with equal ease. Sonny also leads this band with his best compositions ever laid to wax. Working within a variety of time signatures and dropping in riffs that work against the grain of the melody, he maintains a high interest level. Certainly the recording represents a change from what even the most intricate jazz players of the time were doing. He takes nods from Coltrane's modal work and provides a solid and eclectic base.

From the opening run in "Promises Kept," Sharrock builds a fusion-esque groove with drummer Elvin Jones and bassist Charnett Moffett, allowing Sanders to churn out some his strongest playing since the '70s. With the tracks "Little rock" and "As We Used to Sing," the record can almost be seen as a single composition broken into six parts in much the same way as Miles Davis' early-'70s work. These two tracks are the centerpiece and are taken from the same single jam. This makes the whole of the record just as interesting as the individuality of each track. Though they are each unique compositions, after playing the disc through a few times it seems evident that there is a central concept being executed.

One of the highlights on this record is the return of Pharoah Sanders to some of his finest playing in years. Whatever the reason for the renewed enthusiasm, it shows itself throughout. Not only is his playing hot, but there is a true spiritual vibe to his choice of notes and riffs, recalling his classic Impulse work. Sanders' freedom to work outside the perimeter while building up bulk mass fits perfect into the individuality of each tune. The reunion of these two free greats seems to have reenergized their sound, making this recording feel that much more special, especially since it was the last one before Sharrock's death.

The other huge input on this record comes from the man behind the scenes of Sharrock's rise in popularity from the mid-'80s onward: Bill Laswell. Laswell's work on multi-tracking helps to add depth and groove the CD. Laswell is one of the most eclectic voices in music. From the underground noise blasts of his work with Sharrock in Last Exit to his remixes of early rap and dub, he has turned his hand to any number of genres and build a solid vibe. His playing and producing plays as much a role of the final output as Teo Macero's work did with Bitches Brew.

Though Ask the Ages may not be the easiest for jazz guitar fans to get into at first, it is extremely rewarding. Throughout the record Sharrock utilizes a variety of sounds and pushes the limits of his playing. The band certainly picks on the vibe and rips the guts the free jazz's ideas and sound while simultaneously pulling right toward Sharrock's jazz roots.

Spending time in the Sharrock world will certainly help newer jazz fans to understand where players like Bill Frisell, Derek Bailey, and Fred Frith are coming from. Sharrock is without a doubt the brightest beacon of early avant-garde jazz guitar. Running across his records is a schematic that NY downtown guitarists are still using. Certainly the experimental forays of records by Frisell and Frith carry on ideology that Sharrock brought using the guitar as the weapon of means. While most players were spending their woodshedding time learning Wes Montgomery licks, Sonny Sharrock was opening up the jazz guitar to a new world of endless possibility.

Personnel: Sonny Sharrock—Guitar; Pharoah Sanders—Sax; Elvin Jones—Drums; Charnett Moffett—Bass

Track Listing: 1. Promises Kept, 2. Who Does She Hope to Be?, 3. Little Rock, 4. As We Used to Sing, 5. Many Mansions, 6. Once upon a Time

https://www.nytimes.com/1991/05/05/arts/pop-music-a-musician-with-lightning-in-his-hands.html

POP MUSIC: A Musician With Lightning in His Hands

by Mark Dery

May 5, 1991

New York Times

Sonny Sharrock knows what it's like to hold lightning in his bare hands. During the late 60's, in an attempt to emulate the atonal squeals and spluttering trills of saxophonists like Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler, Mr. Sharrock turned up his amplifier and invented free jazz guitar. It was a music of raw power and high voltage.

Since then, he has become best known for his performances on records by Pharoah Sanders, Herbie Mann, Wayne Shorter, Don Cherry and Miles Davis. More recently, the guitarist, who is based in Ossining, N.Y., has been recognized as the gray eminence of Manhattan's downtown avant-garde. The eclectic producer-bass player Bill Laswell, the deconstructionist fusion group Machine Gun and the "no-wave" guitarist-turned-balladeer Arto Lindsay have all cited him as a seminal influence. It would be hard to imagine their music without Mr. Sharrock's blistering noise, brute volume and unorthodox picking techniques in a jazz context.

With the back-to-back appearance of three new albums, Mr. Sharrock stands a chance of reaching a wider audience. "Highlife" (Enemy), the latest from the Sonny Sharrock Band, is currently in record stores. Next month will bring "Faith Moves" (CMP), an album of duets with the guitarist Nicky Skopelitis. In July will come "Ask the Ages," (Axiom/Island), Mr. Sharrock's first solo effort for a major label since 1975. It is a long-awaited collaboration with Mr. Sanders on alto saxophone, Elvin Jones on drums and Charnett Moffett on bass. (This month the guitarist also begins a 28-city European tour.)

Mr. Sharrock's public profile is higher than it has been in years, and the age of the audiences who pack his concerts at lower Manhattan nightclubs seems to be getting younger and younger. During their last show at the Knitting Factory, the Sonny Sharrock Band -- Mr. Sharrock on guitar, Dave Snider on keyboards, Charles Baldwin on bass, Abe Speller and Lance Carter on drums -- tore through numbers like "Dick Dogs," an instrumental that peels out with a heavy-metal figure, sideswipes a filigreed fusion jazz line, then fishtails into Mr. Sharrock's skidding, crashing solo. In the brief lulls between songs, the overflow crowd whooped itself hoarse. Mr. Sharrock, who will turn 51 in August, is the hottest thing in punk jazz.

The brindle-haired, bearish guitarist views his newfound popularity with what might be called good-natured cynicism. "If I had done things differently, I might be getting grants, performing in museums, smoking a pipe," he says with a poker face. "I would be rich by now, or at least well respected -- which I'm neither!" He burst into booming laughter, then turned serious.

"The other night, my wife told me that one of my problems is that I'm always changing before people have a chance to catch up with what I've already done. But the music is evolving, and I can't wait around. It gets to be very frustrating, talking to record companies who told me 20 years ago, 'Sonny, you're 20 years ahead of your time.' Well, I've waited 20 years and now what? I go back to the record companies, and they say, 'Uh, we don't know; it's a little far out.' "

Even so, Mr. Sharrock knew his route would be a rocky one, even before he took his first step. In 1959, at the age of 19, Mr. Sharrock had a life-changing experience. Lying awake one night, his radio tuned to the jazz disk jockey Symphony Sid, the young musician suddenly found himself enveloped by the impressionistic, modal strains of "Kind of Blue" by Miles Davis.

"I didn't sleep for about three days, the music was so incredible," he recalls. "I said to myself, 'I have to play this music, and I'm scared to death because I really don't think you can do this and be successful.' I was frightened, but I thought, 'Hell, this is probably the only thing in the world that I'm ever going to have enough courage to stand up for.' "

Shortly thereafter, Mr. Sharrock took up the guitar (were it not for his asthma, he would have been a saxophonist), and in the years that followed he set about translating the highly idiosyncratic gestures of his horn-playing idols to his own instrument. He conjured Mr. Sanders's screeching tone, generated by overblowing, by bearing down heavily on his strings and pushing his amplifier past its limits to produce notes so rich in distorted overtones that they sounded almost chordal.

To summon the key clicks and breathy chuffing of Albert Ayler, he muted his strings with one hand, scrubbing and scrabbling at them with the other. And from both players he derived his patented "buzz-saw trill" -- rapid, mandolinlike picking meant to suggest flutter-tonguing, a technique used by reed players to produce flurries of notes.

On "Tauhid" (Impulse), recorded with Mr. Sanders in 1966, and "Black Woman" (Vortex) and "Monkey Pockie Boo" (BYG), released under his own name in 1969 and 1970, respectively, Mr. Sharrock seemed determined to challenge the a priori assumptions of jazz guitar. Whereas classic jazz guitarists such as Jim Hall or Joe Pass play lush, pianistic chord solos enlivened by walking bass lines, Mr. Sharrock substitutes simple triads and sometimes eschews chords altogether, using buzzing drones to anchor an improvised passage.

When they solo, guitarists invariably gravitate toward the higher strings, whose piercing, trebly tone slices through the accompaniment; Mr. Sharrock lingers in the instrument's lower registers, where the sound is dark and robust. Most strikingly, jazz guitarists, from Django Reinhardt to George Benson, are noted for their warm, brassy tone and cleanly articulated phrases; Mr. Sharrock's tone is grungy, his articulation muddy. Fumbling at the strings with his stubby fingers, he makes his guitar stammer. The effect is one of awkward honesty.

In 1980, that painfully truthful quality caught the ear of the producer Bill Laswell. It was Mr. Laswell who introduced Mr. Sharrock to the East Village experimental music scene, spotlighting the guitarist on "Memory Serves" (Elektra/Musician), a 1982 release by the fractured jazz-funk band Material. Mr. Laswell subsequently produced two of the guitarist's American releases, "Guitar" (Enemy) and "Seize the Rainbow" (Enemy), and invited him to join the band Last Exit, an exercise in musical gene splicing that crossbred free jazz, blues, heavy metal and noise. Especially noise.

It is Mr. Sharrock's use of noise that led one jazz critic to dream wistfully of tossing him and his electric guitar into a water-filled bathtub, and it is noise that has earned him a following among alternative-rock fans. But Mr. Sharrock's musical persona has another, equally significant face. It is a side that is bewitched by beauty, the one that still hears echoes of the Orioles, the Moonglows, the Flamingos and all the other doo-wop groups whose ethereal, honeyed harmonies floated from his radio when he was a teen-ager. Happily, that side comes to the fore on his new recordings.

On the forthcoming album "Faith Moves," Mr. Sharrock threads dreamy, pastel melodies through multicultural folk music, played by Mr. Skopelitis on acoustic stringed instruments from all over the world. On "Ask the Ages," he pays tribute to what he calls "a time of much magic," the heyday of free jazz in the 60's, framing soulful phrases with Elvin Jones's jittery drums and Pharoah Sanders's blatting saxophone.

On the record "Highlife," he turns "All My Trials," a winsome folk tune popularized by Harry Belafonte, into a bitter-sweet mingling of kick-up-the-heels ebullience and lump-in-the-throat sadness. By shifting the song from its traditional time signature to a highly syncopated one, he gives it a sunny, sprightly feel, then adds a yearning guitar solo for dramatic effect.

"Highlife," based on a traditional African melody Mr. Sharrock first encountered while playing with the Nigerian percussionist Babatunde Olatunji, offers exuberant Afro-pop, festooned with splashes of bright color. And "Kate" reworks a swooningly beautiful melody from "Wuthering Heights," by the English pop singer Kate Bush. Atonality and angularity poke through in spots, as in the slashing guitar solo near the end of "Venus/ Upper Egypt," by Mr. Sanders, but there is a sense of balance, of proportion in "Highlife" that is new to Mr. Sharrock's music.

"In the last few years," he says, "I've been trying to find a way for the terror and the beauty to live together in one song. I know it's possible. I remember seeing John Coltrane standing there, his saxophone screaming, hearing the Flamingos sing at the Apollo. All that pretty music! I hope I'm as greedy as those musicians were. I want the sweetness and the brutality, and I want to go to the very end of each of those feelings." His laughter peals like a bent blues note. "I want it all!"A version of this article appears in print on May 5, 1991, Section 2, Page 30 of the National edition with the headline: POP MUSIC; A Musician With Lightning in His Hands. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper

https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/sonny-sharrock-ask-the-ages/

RATING: 9.5

by Andy Cush

Genre:

Experimental / Jazz

Label:

Axiom

Reviewed:

April 25, 2021

Each Sunday, Pitchfork takes an in-depth look at a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. Today we examine the monumental final album by a singularly talented guitarist with a conflicted relationship to his instrument and an ecstatic vision for his music.

Sonny Sharrock never wanted to play guitar. He disliked the instrument when he first tried it out, as a 20-year-old in 1960, and he remained stubbornly committed to that attitude even after he’d radically expanded its expressive possibilities, remade it to suit his vision, established himself as one of the greatest ever to play it. Or so he claimed, to almost anyone who ever got him on the record, until just about the day he died. In 1970: “I hate the guitar, man.” In 1989: “I don’t like guitar, I don’t like it at all.” In 1991, two months after the release of his last and greatest album: “I don’t like it.” In 1992: “I despise the sound of the guitar.” In 1993, less than a year before his death: “I didn’t like the instrument very much.”

Sharrock had asthma as a teenager, which didn’t stop him from singing doo wop, or dabbling in any street-level mischief that was available to a ’50s kid in his hometown of Ossining, New York. But it did rule out the tenor saxophone he coveted after an encounter with Kind of Blue converted him to the church of John Coltrane. An acquaintance had a guitar on hand, so he picked that up instead. The decision, he would later be sure, had saved his life from “whatever young men die of in the street.” Still, he went on resenting the guitar, which he believed was not suited to the outbursts of ecstatic humanity he heard in Coltrane or the other tenor players he came to love, like free jazz pioneers Pharoah Sanders and Albert Ayler, Coltrane associates who took their music even further toward an oblivion outside Western ideas about melody and rhythm. The guitar, to Sonny Sharrock, always sounded the same, no matter who was playing it. It had no feeling.

Just about every musician Sharrock admired had worked on bandstands, or at least begun seriously honing their craft, while they were still teenagers. As a young man, he felt he was arriving to jazz late in life, too late to learn the music by the usual methods: studying other players, absorbing their licks, eventually developing your own. So he decided to simply express himself as purely as he could within the bounds of his ability at the time, on an instrument he didn’t care for. Had he gone searching for guitar idols, he wouldn’t have found any, because no one before Sonny Sharrock played guitar like him.

Only Jimi Hendrix did as much as Sharrock, as early, to push the electric guitar to its limits and explore what sounds were there. Hendrix’s wildest music, like 1970’s “Machine Gun,” involved extreme volume and the ensuing feedback and distortion, spontaneous outer energy that he harnessed and redirected; if he put the guitar down in the middle of a solo, it might go on roaring without him. Sharrock, who liked to keep the volume on his amp at 4 out of 10, was more like a horn player, animating an object that would otherwise lie mute. Everything that came out—as his slide shot past the end of the fretboard, as his pick struck muted strings, as he strummed chords so quickly and ferociously that they began to resemble approaching tornadoes—came from kinetic effort. The energy was inside him.

Sharrock always considered himself a saxophonist who happened to play the wrong instrument. His closest kindred spirit may be Ayler, whose approach to the tenor was as uncompromising as Sharrock’s to the guitar. Both men favored melodies so bright and clear a child could have composed them, then turned them inside out. They might begin with a folk tune and end with music you couldn’t represent on a staff any more than you could notate shattering glass. The sound itself was the thing. A single instant of noise could be as expressive as an entire melody; there was hardly any difference between the two. They were Black visionaries who rejected the strictures of the white European thought that sought to govern all musical expression. But their music wasn’t only, or even primarily, about negation. It was about freedom, transcendence, a joyous embrace of whatever lay beyond.

Even in the revolutionary world of free jazz in mid-1960s New York City, where Sharrock moved not long after dropping out of Berklee College of Music, his music was a difficult proposition. Before he arrived, “jazz guitar” meant the elegantly melodic soloing of Wes Montgomery or Charlie Christian. Most free groups didn’t have a place for the instrument, which seemed stuck inside the buttoned-up tonality of an earlier era in jazz, and was fast becoming an emblem of the current day’s white pop music. On top of that, there was Sharrock’s fondness for sing-song simplicity, not otherwise particularly fashionable among the avant-garde.

No one quite knew what to do with this strange and singular talent. His first few years on the scene produced one masterwork under his own name—1969’s Black Woman, a collaboration with his then-wife, the equally radical vocalist Linda Sharrock—and a series of electrifying but brief appearances on records by other players. They tended to use him like a scene-stealing character actor, letting him dazzle the audience for a moment and then ushering him out of the frame. As a result, being a Sonny Sharrock fan can feel like being on a long scavenger hunt. Have you heard that crazy R&B album he plays on? Do you know about the uncredited cameo with Miles? It’s a lot of sitting through Herbie Mann records, waiting for him to cut the tasteful flute stuff for a minute and let Sonny rip.

And then there is Ask the Ages. In a catalog that is otherwise unruly and difficult to navigate, Sharrock’s final album is clearly the mountaintop. When it was released in 1991, he was 50 years old, five years into an unlikely creative resurgence after a decade in which he hardly worked at all. He was in the best form of his life, playing with impossible tenderness on one tune and unbearable force on the next. For the first time since Black Woman, he was leading an ensemble of peers and equals—players who could match his intensity, but also exerted a certain solemn gravity, befitting his status as a master, that his last few albums had missed: Pharoah Sanders, the fire-breathing saxophonist who had given Sharrock his first gigs back in the ’60s; Elvin Jones, the John Coltrane Quartet drummer whose torrential cymbal work was a key early influence on the guitarist’s guitar-averse approach; and Charnett Moffett, a virtuosic 24-year-old double bassist who understood when to carve space for himself among these elders and when to sit back.

Three years after Ask the Ages, Sharrock died of a heart attack. Viewed from one angle, the album looks divinely inspired: the culmination of Sharrock’s artistry, reuniting him with towering figures from his past and offering a chance to express the sound inside him once and for all, in a dignified final stand against the instrument he treated like a sparring partner—the instrument that saved his life—before he put it down and moved on to the next one.

From another angle, it looks kind of like a fluke. Sharrock and producer Bill Laswell conceived of the album, down to its title, in a single conversation at a bar in Berlin. They intended to make music that would put the guitarist in touch with his own history. “I want to reconnect with the music of John Coltrane,” Sharrock said, in Laswell’s recollection. “That energy, that possession, that power. I want to get back to that level, that quality again. Make something serious.” The guitarist’s primary focus in those years was the Sonny Sharrock Band, his touring group, a burly rock-oriented outfit with two hard-hitting drummers. Their music is as delirious and uplifting as a carnival ride. It does not sound very much like John Coltrane, nor would you necessarily reach for “serious” as an adjective to describe it.

Sharrock was obviously thrilled with Ask the Ages, but the players weren’t making long-term plans; he seemed to see the album as an enlightening diversion from his main gig. When an interviewer asked him about what would come next, he enthused about Sonny Sharrock Band records he planned to make, which would possibly be influenced by hip-hop. The last bit of music he released before dying was the soundtrack to Cartoon Network’s cult-classic talk show parody Space Ghost Coast to Coast, reflecting a deep playful streak that the imposing Ask the Ages doesn’t always convey on its own. (“I think a cat like Al Di Meola would play better if he smiled a little bit,” he told an interviewer in 1989. “The shit ain't that serious.”) Sharrock’s death makes it easy to apprehend Ask the Ages as his magnum opus, but he might have resisted that idea himself. In life, he rarely traveled by such straight lines.

Laswell and Sharrock had been close collaborators ever since the producer helped the guitarist come back from an involuntary early retirement. Herbie Mann, a mainstream-friendly pop-jazz fusionist, had been Sharrock’s most reliable employer in the late 1960s and early ’70s, despite their considerable musical differences. After they parted ways, Sharrock made another album with Linda—1975’s surreal funk experiment Paradise—and his career soon hit the skids. He began supporting himself with gigs as a chauffeur and at a school for children with mental illness, spending years woodshedding and writing but rarely performing and never recording.

Things started to change when Laswell invited him to play on Memory Serves, a 1981 album by his art-punk-dance band Material. Laswell, who plays bass but is perhaps most important for the myriad connections he’s facilitated between experimental musicians across genres, began bringing Sharrock in on more projects after that. Chiefly, there was Last Exit, a band whose ruthlessly discordant music, improvised from scratch every night, favored pummeling punk rhythms over the swing that underpinned even the furthest-out free jazz, sounding more like what was coming to be known as noise rock.

After washing up on the shores of jazz, Sharrock was suddenly celebrated as a visionary progenitor to a new generation of adventurous rock musicians and listeners. Thurston Moore bought a pile of Herbie Mann records and isolated all Sharrock’s solos, dubbing them onto a single cassette. “It was one of the best things I had ever seen and heard,” he said of a Sonny Sharrock Band performance he attended at the Knitting Factory. “It was enlightening. It kind of informed me further, as far as what I wanted to do with the guitar.” The world of experimental electric guitar playing, where white artists often win the most acclaim today, would not exist as we know it without Sharrock.

Ask the Ages brings the intensity of Sharrock and Laswell’s previous collaborations into a format more easily recognizable as jazz. Sharrock, who composed the material himself, channeled his taste for simple and direct melodies into the opening tune of each piece. In these sections, he frequently overdubbed multiple interlocking guitar lines, which massed together with Sanders’ tenor into something liquidy and metallic, a mutant horn section. Most tracks, for the first minute or so, are swinging and approachable, maybe even a little old-fashioned. Then comes the fire.

On “As We Used to Sing,” a stately minor theme ascends to a breaking point, and Sharrock’s solo takes over: first furious and serpentine, then jaunty and staccato, then out somewhere past the horizon. (Despite his stated preference for plugging straight into his Marshall amplifier at moderate volume, it’s hard to believe he’s not getting some more juice from the amp or a pedal.) Even as he departs from the melody and begins summoning waves of pure sound, there is a distinct emotional trajectory. He valued feeling above all else in his playing, and professed disinterest in noise for its own sake. At the passage’s peak, rather than winding down, Sharrock abruptly stops, and the resulting negative space is as striking as the previous cacophony. When Sanders steps in and offers a series of birdlike calls on his horn, it’s like witnessing the first signs of new life after a disaster that wiped the earth clean.

Sharrock spoke in his later years of a sense that he was paring down any extraneous elements in his playing in an effort to get closer to the heart of a given melody. This effort is audible throughout Ask the Ages, and most clearly in “Who Does She Hope to Be?,” the shortest and sweetest tune. Jones and Sanders recede to the margins, hardly playing anything at all. Sharrock’s phrases are spacious and melancholy. He isn’t doing anything fancy, just letting the melody speak. Your attention moves to Moffett, whose fluid self-possession on the bass turns the arrangement on its head. For an album so concerned with legacy, Ask the Ages never gives the sense that this music is anything other than a living thing. “Who Does She Hope to Be?” underscores this attitude powerfully: The young sideman, for a moment, has become the leader.

The album reaches its astonishing apex with “Many Mansions,” the track that most recalls Sharrock’s sojourns in avant-rock. Its pentatonic theme has the elemental quality of A Love Supreme’s “Acknowledgement” section, but as it repeats across nine minutes, it also begins to resemble a Black Sabbath riff. Sanders takes the lead before Sharrock, with a solo that reaches a climax before it even gets going, beginning with an ecstatic fit and growing only more frenzied from there. With the cry of a single sustained note, or a babbling trill between two, he conveys lifetimes. Elvin Jones, in his mid-60s, seems even more potent than he was as a young man, urging the soloists to ever-greater heights. Thanks in part to advances in recording fidelity over the previous several decades, his kit has become a visceral entity, almost multisensory; each bass drum hit is a wallop to the chest, the shimmer of ride cymbals is nearly visible in front of you. According to Sharrock, there is an audible mistake in his guitar solo, a flicker of lost composure brought on by Jones’ rhythmic onslaught. “I flashed back to Birdland when I used to see him with Coltrane,” he said. “And I lost it. For a second you can hear this bump, because I was gone.” Good luck finding it.

Articulating the beauty of Ask the Ages is difficult, because it seeks something that can’t be described. Sharrock was unsparing in his dismissals of music that sidelined feeling—indulging in artifice and imitation, or betraying a desire to impress the listener—including his own less satisfying efforts. “That's not making music; that’s putting together puzzles,” he told an interviewer about a year before his death. “Music should flow from you, and it should be a force. It should be feeling, all feeling.”

“The whole thing,” he said in the same interview, was “just to get this thing in me, get it out, you know? Make it real. Because it’s in you and it’s fine, but it isn’t real yet until you make it music.” Near the end of his life, Sharrock seemed to feel that he was closer than ever to finding that thing. He continued to profess hatred for the instrument he was stuck with, but the love in his late music is unmistakable. Like his hero John Coltrane, he died in the middle of a visionary period, leaving behind work that suggests further revelations to come. “I don’t even think about age,” he told another interviewer. “I’m just so happy to be playing good that I don’t care...I’ve got a long way to go. I’ve just discovered myself, you know? It’s just now started to happen for me musically. I now am able to play the things that I hear.”

Sharrock once said that he was only religious insofar as he believed that Coltrane is God. Still, his quest for truth of expression in his playing was not unlike Coltrane’s more explicitly spiritual yearning. Coltrane wanted a higher power; Sharrock just wanted feeling. Listening to him and the band speaking in tongues across Ask the Ages, you might wonder whether those are two names for the same thing.

May 31, 1994

08:55

Remembering Sonny Sharrock.

Sonny Sharrock was a guitarist. His genre was the free-jazz movement of the late 1960's Jon Pareles said in the New York Times that Sharrock's "guitar solos streaked and clanged, using blistering speed and raw noise to create music that had both the openness of jazz and power of rock." (Rebroadcast of 10/23/1991)

Queue

January 27, 1992

16:28

Jazz Guitarist Sonny Sharrock.

Jazz musician Sonny Sharrock. He's been called America's leading free jazz guitarist. His new album is called "Ask the Ages." (It's on Axiom records).(REBROADCAST. ORIGINALLY AIRED 10/23/91).

Queue

October 23, 1991

16:35

Jazz Guitarist Sonny Sharrock.

Jazz musician Sonny Sharrock. He's been called America's leading free jazz guitarist. His new album is called "Ask the Ages." (It's on Axiom records).

Sonny Sharrock, 53, Guitarist In Avant-Garde and Free Jazz

Sonny Sharrock, a major figure in free-jazz guitar, died on Thursday at his home in Ossining, N.Y. He was 53.

The cause was a heart attack, said his manager, Mary McGuire.

Mr. Sharrock was a pioneering guitarist in the free-jazz movement of the late 1960's. His guitar solos streaked and clanged, using blistering speed and raw noise to create music that had both the openness of jazz and the power of rock.

He performed with many important musicians in both the jazz avant-garde of the 1960's and the downtown New York improvisation scene of the 1980's, and he has been cited as an influence by guitarists from Carlos Santana to Elliott Sharp. First Love: the Saxophone

Mr.

Sharrock was born in Ossining and sang in a doo-wop group as a

teen-ager. He decided to become a jazz musician after hearing Miles

Davis's "Kind of Blue" in the late 1950's.

Factoid: After Sharrock's death in 1994, the Black Rock Coalition held a memorial concert in his honor in New York City's Central Park. This booklet was produced for the event.

Because he had asthma, he ruled out playing his favorite instrument, the saxophone, and instead took up the guitar in 1960. His idols were saxophonists, however, and he worked to transfer the expressiveness of improvisers like John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler to his guitar. He developed a personal vocabulary of overdriven amplifiers, high-speed tremolos and percussive picking on muffled strings. Like Ayler, he often built solos atop resonant melodies based in folk and blues.

Mr. Sharrock moved to New York City in 1965 and worked as a sideman with musicians including Pharoah Sanders, Cannonball Adderley and Miles Davis. In 1966, he recorded the influential album "Tauhid" with Mr. Sanders, and he went on to record with Wayne Shorter and Don Cherry; he appears, uncredited, on "Yesternow," from Miles Davis's 1970 album "A Tribute to Jack Johnson."

From 1967 to 1974, he worked regularly with a group led by the flutist Herbie Mann, which also included the singer Linda Sharrock, who was then his wife. In the mid-1970's, the Sharrocks started their own group, Sharrock. They were divorced in 1978. 'The Terror and the Beauty'

In 1980, Mr. Sharrock began working with the producer Bill Laswell, who introduced him to New York's experimental downtown improvisers. He appears on Material's 1982 album "Memory Serves," produced by Mr. Laswell, who also produced Mr. Sharrock's albums "Guitar" and "Seize the Rainbow." Mr. Sharrock was a member of the high-powered improvising group Last Exit with Mr. Laswell on bass, Ronald Shannon Jackson on drums and Peter Brotzmann on saxophone.

He also led his own groups, which performed regularly at jazz and rock clubs, and he recorded albums in the United States and Europe. "In the last few years," he told an interviewer in 1991, "I've been trying to find a way for the terror and the beauty to live together in one song. I know it's possible."

Mr. Sharrock is survived by his wife, Nettie, and his daughter, Jasmyn, both of Ossining.

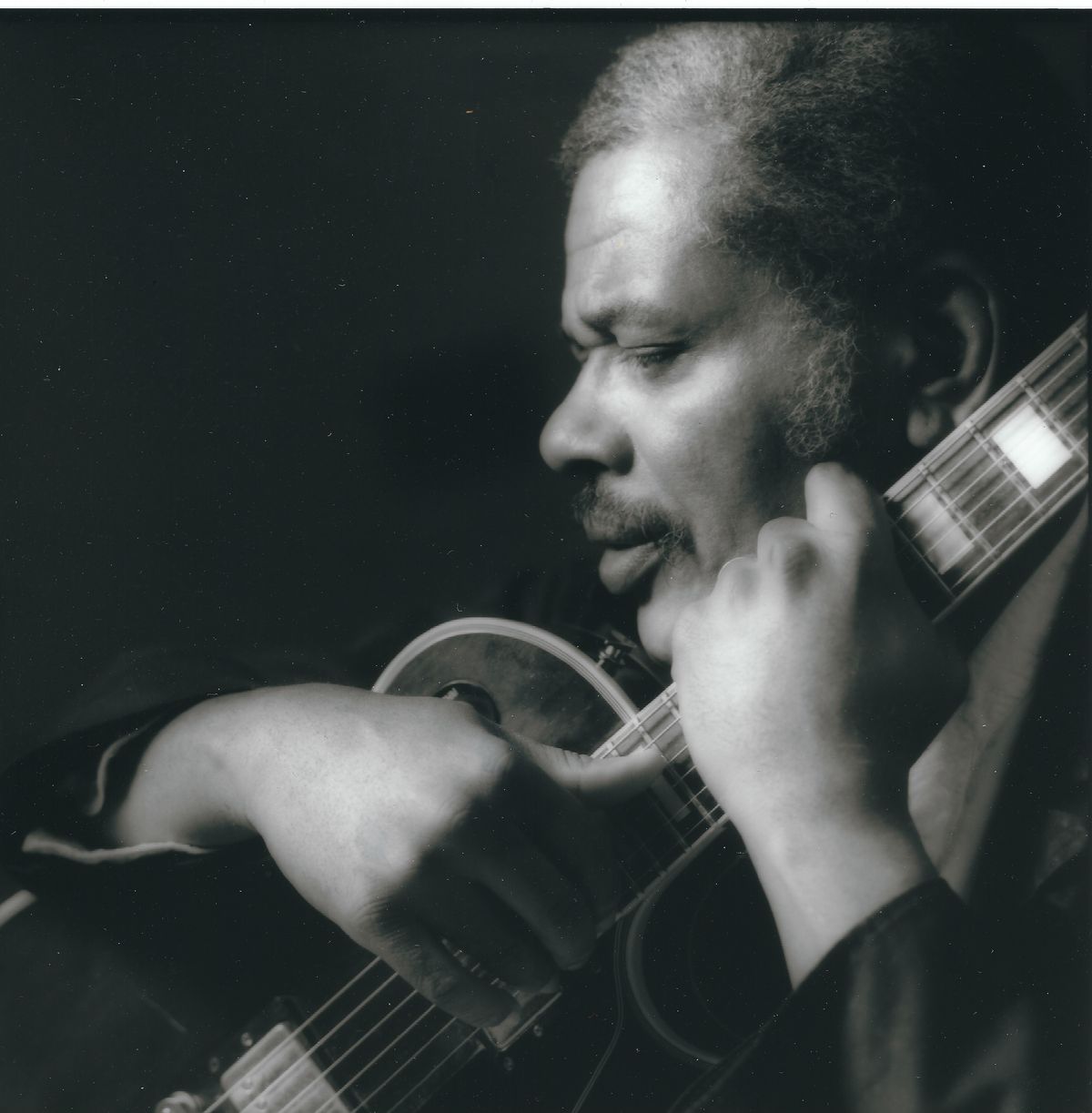

Sharrock created a unique language on the guitar, inspired by the horns of John Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders, bringing free jazz into the 6-string lexicon. Photo by John Soares

Sonny Sharrock, whose guitar playing harnessed the explosiveness and beauty of a summer thunderstorm, recorded Seize the Rainbow

in 1987. By then, he'd been doing just that for more than two decades,

using his guitar as a prism to reflect his glorious, Technicolor vision

of music and life. Along the way, he helped invent free-jazz guitar.

The flautist and bandleader Herbie Mann, who employed Sharrock and his

then-wife Linda in the late '60s, referred to the unfettered guitarist

as “my Coltrane." And, indeed, Sharrock's own awakening as a musician

happened as a teenager when he heard John Coltrane's performances on the

immortal Miles Davis album, Kind of Blue. Although it took until

1966, when he was 26 and playing with Coltrane's sax-wielding friend

Pharoah Sanders, for the light bulb that illuminated his approach to

ignite.

“I remember the very day I learned to play 'out,'" Sharrock told me when

we first met in 1988. “Pharoah had this technique of overblowing the

horn. It sounded like very fast tonguing, like a buzz saw. I tried to

copy it by trilling on the guitar and found that I could get a huge

sound, but more human, like a voice. Then I tried to stretch it by

pulling strings and bending notes, and that was the beginning."

The end came too soon. After decades of struggle—even leaving performing and recording to work as a chauffeur and a music therapist for mentally challenged children—Sharrock died just as the world's doors were fully opening for him and his music. Three years after releasing 1991's majestic Ask the Ages, a graceful, expansive, and clamorous return to the '60s free-blowing aesthetic that had inspired his beginnings—an album that ended up on major jazz and rock critics' top 10 lists and propelled Sharrock toward stardom—he was on the verge of signing his first major-label deal. To prepare for that milestone, he was exercising at his home in Ossining, New York—the small city in the shadow of the notorious maximum-security prison called Sing Sing—and dropped dead from a heart attack. He was 53.

Sharrock left behind an amazing legacy of recordings. As a sideman, he'd played on Miles Davis' A Tribute to Jack Johnson paired with John McLaughlin, and he made seven albums with Mann, including the influential Memphis Underground. He also played on Sanders' 1966 classic Tauhid, Wayne Shorter's innovative Super Nova, Don Cherry's Eternal Rhythm, and discs by Ginger Baker, Roy Ayers, soul/avant jazz-fusion band Brute Force, and new-wave avant-funk outfit Material, among many others.

Before his '80s re-emergence, Sharrock had recorded two albums as a leader—his 1969 debut Black Woman and 1970's Monkey-Pockie-Boo—and cut 1975's Paradise co-billed with Linda Sharrock. When he returned to full service, he did it with passion, making seven albums from 1986 to 1993, ranging from the all-solo instrumental Guitar to the blithe, melody possessed Highlife to the soundtrack for the cartoon Space Ghost Coast to Coast. He was also a member of Last Exit, perhaps the wildest bunch of free-improvising gunslingers to ever take a stage, along with bassist/auteur Bill Laswell, drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson, and reedman Peter Brötzmann. They'd never played together until Laswell summoned them to a festival in Köln to perform and simultaneously record an album in February 1986. In Last Exit, Sharrock delivered some of his most furious, unpredictable solos—often employing the solid Stevens bar he used for slide to conjure the kinds of sounds one would expect to emit from the gates of hell. (And the Pearly Gates, too, because Sharrock had a gift for creating angelic melodies.)

By the Horns

The great American improvising guitarist Henry Kaiser bought his first guitar and slide the day he heard Sharrock on Sanders' Tauhid. Kaiser went on to play with Sharrock (and scores of others), and recently released the tribute album, Echoes for Sonny,

with fellow Sharrock cohort and guitarist Robert Musso. He summarizes

the late genius thusly: “Sonny was the kind of guitarist who comes along

once in a generation—if that—as special as Hendrix, Django, and B.B.

King. A magical person. No one has made a more original statement on the

instrument. Sonny had as much heart as B.B. or Carlos Santana. He stood

in the middle of what was happening in black jazz in the '60s, socially

and politically, and in the beginning of free jazz. Without Sonny

Sharrock, there is no Vernon Reid, no Sonic Youth … so many things

people have embraced musically.

“And his slide playing is unprecedented," Kaiser continues. “It's technical and non-technical at the same time, so it was accessible to me the moment I heard it. Just how original was he? Well, if you look to B.B. King, first there was T-Bone Walker. For Jimi Hendrix, you've got the influence of Curtis Mayfield and Muddy Waters. For Sonny, there ain't nuthin'. He's the first guitarist with his footprint on the moon."

Sharrock's Earthly arrival was on August

27, 1940, in Ossining, where he spent much of his life. “Dad's full

name was Warren Harding Sharrock, Jr., after my grandfather, but he

never liked that name," says his daughter, Jasmyn Sharrock. The stories

of the 29th president's affiliation with the Ku Klux Klan were a thorn,

and Sharrock quickly adopted what his family called him as his handle.

His first musical obsession was vocal groups, like the Moonglows and

Orioles. “The greatest thing I'd seen until then was Red Ryder and

Little Beaver on their horses," Sharrock recalled, “but these groups

were the hippest. They had matching suits, did coordinated steps, and

they sounded incredible." At 14, his baritone singing earned him a spot

with an integrated group of neighborhood kids who called themselves the

Echoes. “The other guys were a lot older, but I'd just pencil in my

moustache and go right on into the club."

A few years later, in 1959, he was listening to Symphony Syd, the hot jazz DJ on New York City's WJZ, and heard Kind of Blue.

“I saw Miles' band that summer and I was gone from that moment on,"

Sharrock recalled. He began a lifelong obsession with horns and drums.

“But I couldn't afford either, and I had asthma, so I knew I couldn't

play the saxophone." His consolation prize was his first guitar, which

he purchased in 1960, and he split Ossining for Boston and the Berklee

College of Music in '61.

“There were 26 guitarists enrolled, and I was ranked 25th," he

recounted. “Then the 26th guy left and I was at the bottom." He didn't

stay much longer. Armed with the basics of music theory, Sharrock moved

to California in 1962 and lived in a trailer with several other

struggling musicians while trying to pick up gigs and sessions. But not

before suffering one more indignity.

“I got into a band and we worked for just one night at a coffeehouse in

Cambridge," he said. “Sam Rivers and Tony Williams were in town and

decided to sit in, and they destroyed us." He laughed and shook his

head. “They played 'Milestones' at a tempo I'd never realized existed!"

Ultimately, he found his musical home in mid-'60s New York City. “When I got there, I ran into Sun Ra on 125th Street and I asked to study with him. He said, 'Come by.' So I went to his place and Pat Patrick, Marshall Allen, and all these heavies from his band were there, and Sun Ra showed me two movies. That was the extent of the lesson. Real weird! But while I was there, they got a call from [Nigerian drummer and bandleader] Olatunji about a gig. I heard Pat say, 'Yeah, I've got a guitar player here.' I thought, 'He can't be talking about me.' That's how I ended up working with those guys. They were very nice to me, because I didn't know what the hell I was doing."

So Sharrock's bona fide apprenticeship on the bandstand and in the studio began, including the important work with Sanders that set him exploring dissonance, distortion, slurred licks, and skittering, screaming slide, as well as melodic excursions inspired by horn players, classical music, and blues. His tone grew darker, richer, and bigger, and would continue to do so throughout his career as he upgraded gear and further defined himself. He also began using distortion pedals, so he could compete with the sound of an overblown tenor sax.

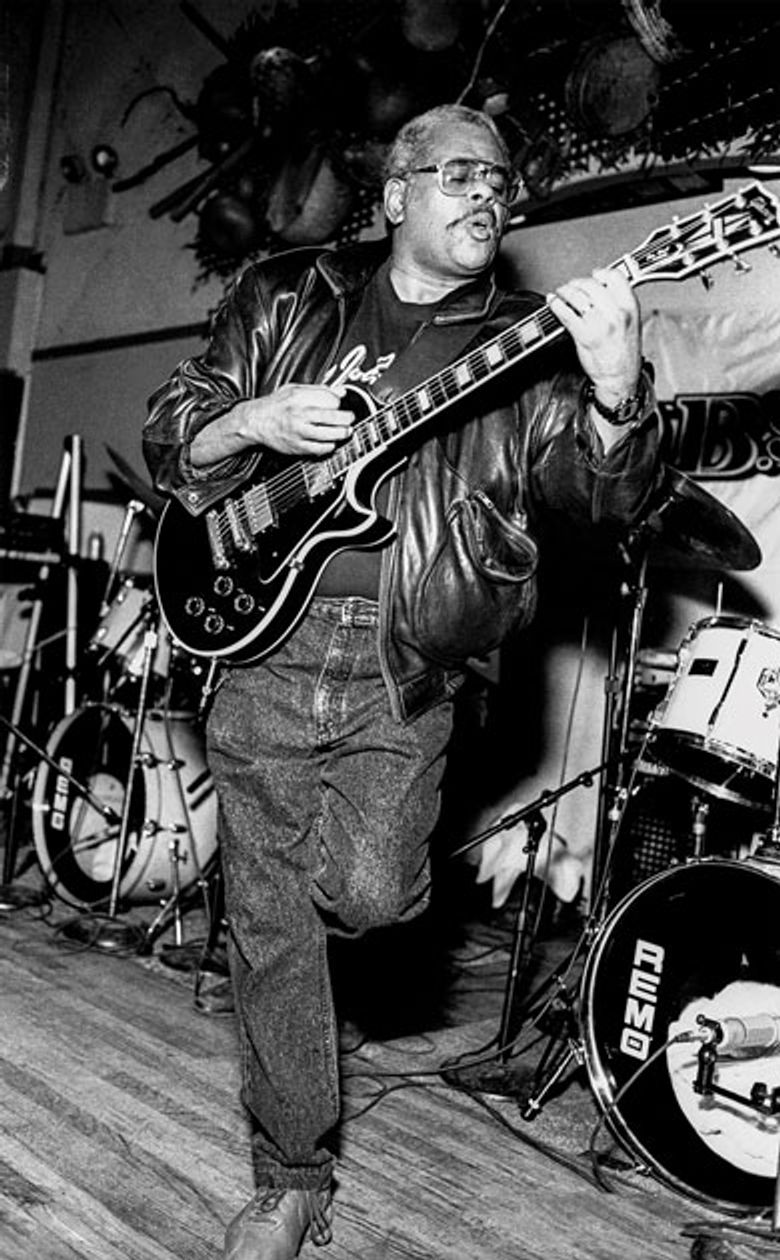

In mid-flight during a 1992 concert, Sharrock fused energy and intellect into a breathtaking dialog with his audience. Note his T-shirt, from a Last Exit performance at Johnny D's in Somerville, Massachusetts, on February 2, 1990, one of the band's three U.S. performances. Photo by Jack Vartoogian/FrontRowPhotos

Clearing the Room

Sharrock was recording and performing with reed player Byard Lancaster

when he got a telegram—he was so broke that he didn't have a

phone—asking him to call Herbie Mann.

Mann fused jazz and pop, and had been among the musicians who'd

popularized the bossa nova in the States during the early '60s. He sold a

lot of records across a spectrum of listeners. He also had broad tastes

and was looking for a connection within his own music to the free jazz

sounds that were exciting him. Soon, Sonny was getting the spotlight

once at every Mann concert, and he was joined there by vocalist Linda

Chambers, who he'd later marry, when she was also hired for Mann's

group.

“I'd reached a point where I wanted to have some contrast

in the band," Mann told me in 1988. His audience had not. “The reaction

was often hate—total hate," Mann said.

Sharrock remembered a gig with Mann at a Florida jazz festival. “It was

at a marina, and all these people came in yachts," he said. “In the

middle of Herbie's set, Linda and I came out to do 'Black Woman'."

The song was the title track to Sharrock's debut album, the result of a

deal Mann has brokered with the Atlantic Records subsidiary Vortex.

“They all sailed away," the guitarist recalled, chuckling.

Decades

and an upswing in his popularity didn't necessarily change all

audiences. When he and Henry Kaiser took the stage to play duets at an

Italian jazz festival in 1987, following the staid Modern Jazz Quartet,

“the audience was like a tidal wave," Sharrock recounted. “We cleared

the room instantly. My [second] wife, Nettie, cried, because she'd never

seen anything like that before." He laughed, gently. “I said, 'C'mon,

that's nothing! Do you want me to clear out the ushers, too?'"

Humor was another of Sharrock's trademarks. And his friends and

bandmates loved him for his wicked one-liners and playful skewerings.

“It was as if I was on a laughing-gas high," recalls Pheroan akLaff, one

of the two drummers in Sharrock's juggernaut Seize the Rainbow

band. “If we went on the road, there would be continuous Don

Rickles-style jokes hurled about you from the moment of airport check in

until we said goodbye. In fact, I don't ever remember him saying

goodbye, unless it came in an insult. That was his way of expressing

love."

His daughter Jasmyn also loved Sharrock for his playful spirit. Dad was by no means the disciplinarian among her parents. He encouraged her to dance as they listened to music together, and took her on frequent excursions into New York City. “The time he spent in Manhattan shaped him as a young man," she says. “He wanted me to experience the heartbeat of the city, and because of that I became a city rat as an adult and have never lived in the suburbs."

At our first meeting, I asked Sharrock how he felt about his decades of struggle. His reply: “I've been trying to sell out for years, but nobody's been buying."

And despite Sharrock's avowal to “find a way for the terror and

the beauty to live together in one song," there was also humor in his

music. It was woven into the grinning, peppy melody of “Blind Willie," a

sweet 'n' droney composition on his first album, and the chipper

theme—and even the title—of his Seize the Rainbow tune “The Past

Adventures of Zydeco Honey Cup." He also laughed and joked with his

audiences—often with pointed wit. A video from a 1988 show at the

original Knitting Factory, his New York home base in the '80s, features

this song introduction: “This is dedicated to the South African

government, the Israeli government, and those brothers that are gonna

git yo' ass on the way home. It's called 'Stupid Fuck.'"

But he had nearly a decade of hurdles to clear before becoming a darling

of the downtown Manhattan music scene. Driven to experiment with pop

due to lagging record sales and gigging opportunities, he and Linda, an

astoundingly potent vocalist who, like Sonny, worked in sheets of sound

rather than conventional language, made the album Paradise. Sonny declared it a disaster, and the disc headed straight to the cutout bins. Today, Paradise

is appreciated for its beauty and riskiness, but the guitarist

considered the album on Atlantic's Atco subsidiary a self-betrayal of

the creative aesthetic he'd forged.

“I worked hard to be me," he

declared. “I like drums and I like Coltrane. People used to get mad at

me because I'd get hired for a gig and I'd say, 'I ain't gonna play

chords. That's guitar. I'm a horn player. I just play a fucked-up horn.'

"

In 1978, he put down his “horn"—at least in public. He and Linda got

divorced and he moved back to Ossining. “I worked with disturbed kids

for a while, which was very demanding," he said. “Then I got a job as a

chauffeur. Not a bad gig, but not what I'm supposed to do." He also

remarried, to Jeanette Hill, and they had Jasmyn.

Thankfully, Bill Laswell knew what Sharrock was supposed to do. He'd

fallen under Sharrock's spell in his early teens. “In high school, when

we first heard him, it was on Herbie Mann records," Laswell says. “When

Sonny's solo came on, we'd pick the needle up off the record to see what

was wrong. It sounded like the guitar exploded." At age 15, Laswell

hitchhiked from Michigan to the Newport Jazz Festival and saw Sharrock

play with Mann. “He made a great impression on me," Laswell recalls.

The

bassist/producer caught one of Sonny and Linda Sharrock's final gigs in

a small club after moving to New York City in the late '70s. He also

got Sharrock's number. In 1981, he used it, inviting Sharrock to come

play in the punk clubs as a guest with his band Material. Sharrock also

played on the group's debut album, Memory Serves—a gloriously fractured mix of rock, free improv, and funk grooves.

While his own star rose as a producer for Mick Jagger, Fela Kuti, Peter

Gabriel, and others, Laswell dedicated himself to nurturing Sharrock's

comeback, producing Guitar and Seize the Rainbow, and

organizing Last Exit. And Sharrock, thus encouraged, assembled a quartet

around the rhythm section of drummers akLaff and Abe Speller, and

bassist Melvin Gibbs, who's gone on to play with the Rollins Band and

currently co-leads the ambitious jazz group Harriet Tubman.

Seize the Rainbow was unprecedentedly hard-rocking jazz: less ornate and overtly virtuosic than the Mahavishnu Orchestra and other volcanic fusion outfits, while more rooted, basic, and expressive—at least until Sharrock took off on one of his slide solos that seemed destined for Pluto. Live and on album, he drove his guitar to unpredictable places, and yet, within the framework of a few carefully selected notes, could return to a song's core melody in seconds and with perfect, logical balance. It was breathtaking.

The Pinnacle

By '87, Sharrock was playing a Les Paul Custom through a Marshall

half-stack, sidestepping the hollowbody jazz guitars and Fender amps

he'd used in his earlier work, opting for more volume and tube gain

instead of an overdrive pedal. “I'd come back from England, producing

Motörhead, and I told him about using Marshalls real loud, and he got

into it," says Laswell. “When we got to Japan with Last Exit, he had a

whole wall of Marshalls and he'd gotten his black Les Paul, and that was

his sound." But his sound, even via that classic combination of guitar

and amp, was uniquely liquid and colorful—a thick, sweet sonic syrup

that could suddenly leap like lava.

Laswell also turned guitarist and engineer Robert Musso on to Sharrock's music. Musso mixed and engineered Seize the Rainbow

and most of Sonny's recordings that followed. He also drafted Sharrock

to record and gig with his own band, Machine Gun, and they became

running buddies.

“He used slightly different guitars and amps every time I recorded him,"

Musso recalls. “Sometimes I'd use an SM57 and sometimes a Sennheiser MD

421 on his amp, and he'd use Les Pauls and wah-wah pedals set in

certain positions to get the tone he was looking for. No matter what he

did, it was Sonny and it sounded great."

For Gibbs, Seize the Rainbow was one of the most memorable album sessions he's done. “When Sonny started playing around town again, I started following him until he hired me," says Gibbs, who'd just quit playing in Ronald Shannon Jackson's Decoding Society. “I remember one gig where I said, “Let me just play some shit and see what Sonny does, and I played wild and he just kinda smiled like, 'yeah, I got you,' and played it back at me. Playing with him helped me figure out who I was."

After a handful of shows with Sharrock, Gibbs was instructed to be at Electric Lady Studios at 7 on a night in May 1987. “We couldn't have spent more than two hours recording," he recalls. “We recorded 'Dick Dogs' first, and I was still kind of fuckin' around with my headset during the take, and Sonny was like, 'That's great. On to the next song.' I thought, 'Oh, we're not fuckin' around today!' When we were done, I looked up at the clock and it was like, 'Shit! 10 o'clock!'"

The seven-song Rainbow was edgy, accessible, and adventurous at the same time, and it introduced Sharrock to the rock world as well, earning him a new audience that continued to expand for the remaining years of his life.

Live in New York, cut at a 1989 Knitting Factory show, came next. It was followed by Highlife, which features Jasmyn and her dad on the cover and is Sharrock's most melody-focused album—a calculated effort to boost his audience even more as he worked toward a grand vision of recapturing the glories of '60s free jazz in the studio. Touring behind this succession of albums and hitting the stage and studio with Last Exit kept accumulating the capital he needed to realize that vision. A set of guitar duets with Nicky Skopelitis, who worked regularly with Laswell, called Faith Moves was next. And then Sharrock reached goal in 1991 with Ask the Ages.

With

Laswell producing and Jason Corsaro engineering, he entered Sorcerer

Sound in Soho with free jazz giants Sanders and drummer Elvin Jones, and

Charnett Moffett, a 24-year-old bass wunderkind who nailed the vibe of

elder statesmen like Paul Chambers and Percy Heath. The result was a

musical perfect storm. In six tunes, Sharrock built a sonic bridge

between his own past and future, supported by big, buttery guitar tones

that boldly laid out succulent, easily digestible riffs. The guitar and

horn unison head of “Promises Kept," the loving melody of “Who Does She

Hope to Be?" (written for Jasmyn), and the riveting, intense “Many

Mansions" were the work of an artist who'd tied together all the

elements of his soul.

Sharrock set the scene for cutting that last, magical tune: “Pharoah was

in the glass booth on one side of the room. Charnett was on the other

side. I was out on the floor sitting across from Elvin laying down the

drone, and I flashed back. Looking at him and hearing him up close, it

was suddenly the first time I saw him back at Birdland with Coltrane.

And I lost it. I totally lost the tune, because he was playing such a

deep, deep groove. I went into a total fan thing and forgot about being a

musician, because it was just too good. You can hear my mistake on the

record, too, because I wanted to keep that."

Sure, the sound of Ask the Ages was something he'd begun

sculpting in '67, but, Sharrock explained, “it wasn't complete at that

point. Now it is complete, and it's ready to be heard." And today it's

ready to be heard again. Late last year Laswell reissued Ask the Ages on his M.O.D. Technologies label, and it's still stunning and full of heart.

The album gave Sharrock wings. He toured more, and he felt that his

playing continued to improve—as odd as that sounded to us knocked-out

acolytes. And then, he died. Leaving so much fantastic music unmade.

“I remember him saying that after his grandmother told him he should go to church, he told her, 'No grandma you should listen to John Coltrane,'" says akLaff. “His generation had that clarity. Him, Carlos Santana—they each have the depth of spirituality as their most earnest goal, and to reach it through their instruments and share it with others. That came out in Sonny's playing."

“The biggest thing I

learned from being around my dad is to never compromise who you are,"

say Jasmyn Sharrock. “Integrity is the first word that comes to mind. My

dad never changed who he was regardless of who was around. He stood up

for what he believed in: doing the right thing and being a kind person.

It sounds corny, but he believed if you do the right thing, then things

will work out. He was always a class act."

Santana Talks Sharrock

When Sharrock traveled to Japan, he took two Les Paul Customs. One had extremely high action, for practice. The other was set close to the neck, for speed. Photo by Paul Robicheau

Given Sonny Sharrock's relative obscurity and the iconoclastic nature of his music, it's surprising to hear a high-profile artist like Carlos Santana work one of Sharrock's tunes into his sets. Nonetheless, “Dick Dogs" from Seize the Rainbow is occasionally a hard-rocking highlight of Santana concerts, and Carlos says his solo for “Bliss" draws straight from the well.

“I was ready to do a tour with him, record with him, and then he left us," Santana explains. “We talked a few times on the phone after he found out I was fully into him, and he was such a gentlemen and very gracious and encouraging. To me, he was a tornado when he played and he left an imprint with his melodies, of course, but I was also into the energy."

The guitar legend says he first heard Sharrock on Wayne Shorter's 1969 fusion classic Super Nova. The next year, Santana caught Sharrock live in Montreux, playing with Herbie Mann. “He had a big 'fro and a fringe jacket and was laying into it, and I was, like, 'Dang, this is a very radical dude!' I couldn't take my eyes off of Sonny, because when he went into his solo it was like Coltrane and Jimi Hendrix, Albert King, John Gilmore, Pete Cosey, and Larry Young all together—interdenominational intergalactic music. It was a thing of beauty. I remember a lot of people got up and left because they were not ready; their minds were, like, 110 and he was 220. I was like, 'This is the shit!' Sonny Sharrock and [P-Funk's] 'Maggot Brain'—that was a new way. So refreshing to hear something so different from Queen, Hendrix, Jeff Beck, or Led Zeppelin, but at that level of mastery."