AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING, 2022

VOLUME ELEVEN NUMBER TWO

ROSCOE MITCHELL

MORGAN GUERIN

(March 18-24)

KENNY KIRKLAND

(March 26-APRIL 1)

STACEY DILLARD

(April 2-8)

CHARENÉE WADE

(April 9-15)

JAMAEL DEAN

(April 16-22)

BRUCE HARRIS

April 23-29)

BENJAMIN BOOKER

(April 30-May 7)

UNA MAE CARLISLE

(May 7-13)

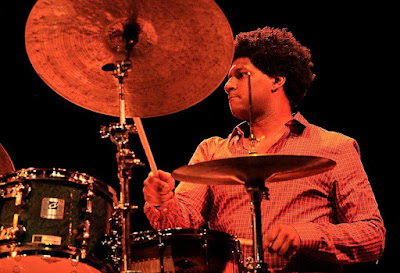

JUSTIN BROWN

(May 14-20)

TYLER MITCHELL

(May 21-27)

JONTAVIOUS WILLIS

(May 28-June 3)

CHRIS BECK

Brown grew up in Oakland, California and played drums as a toddler; He gained his first experience as a musician in the Pentecostal Church . When he was ten, he began taking classes in the Young Musicians Summer Program at the University of California, Berkeley . In 2002 he received a scholarship to study at the Dave Brubeck Institute at the University of the Pacific . After graduating in 2004, he continued his studies at the Juilliard School in New York City. Since then he has worked with musicians such as Kenny Garrett , Christian McBride , Gerald Clayton , Stefon Harris ,Esperanza Spalding , Terence Blanchard , Josh Roseman , Gretchen Parlato , Yosvany Terry , Gonzalo Rubalcaba , Bilal , Marko Churnchetz and Vijay Iyer . Since the 2000s he has been a member of the quintet by Ambrose Akinmusire and Walter Smith III , which can be heard on the Blue Note album The Imagined Savior Is Far Easier to Paint (2014). In 2009 he was a finalist in the Thelonious Monk competition . He also worked with Pacal and Remy Le Boeuf. In the field of jazz he was involved in 21 recording sessions between 2003 and 2014. [2] Brown's album Nyeusi was voted one of the best jazz albums of 2018 by The New York Times . [3]

Portrait in Jazz Hot

Interview

Best Jazz of 2018

JUSTIN BROWN

Justin Brown is a drummer and composer from Oakland, California. His journey so far has seen him play with a multitude of artists including Thundercat, Herbie Hancock, Flying Lotus, Esperanza Spalding, Kenny Garrett and, most recently, touring in Europe with bassist Ben Williams.

Always tasteful in his approach and execution, Justin’s style is progressive and virtuosic yet extremely musical. He began playing drums at a young age and later graduated to playing in clubs by his early teens, before studying at the Manhattan School of Music.

Justin has recently returned to California after being a longtime resident of New York City, where he had initially moved as a student before becoming an active participant in the city’s eclectic music scene. In 2018 he released his first album as a bandleader under the name Nyeusi which gained high accolades from both the New York Times and NPR’s Simon Rentner. The album sits at the intersection of jazz fusion and hip-hop, managing to sound both vintage and incredibly modern at the same time. It features a selection of luminary musicians from the New York jazz scene including Jason Lindner (★) and Fabian Almazan and is available to download here

<a href="https://href.li/?http://justinbrowndrums.bandcamp.com/album/nyeusi">NYEUSI by Justin Brown</a>SIGHT/SOUND/RHYTHM spoke with Justin before a show in Vienna, Austria to talk about his musical background and upbringing, connecting the line between some of his many collaborations, and submitting to the music.

You just moved back to California

after 13 years in New York. What prompted that move for you?

Well, two things.

The main thing was family. My mother is getting older, plus I also

have a fifteen year old nephew and I really want to be more involved

in his life.

There’s no place

like New York as far as the music scene, which is what drew me there,

but it was just the day to day living that I tapped out on. Just the

thought of getting on the train and dealing with all of those

energies in a compact space… I just needed a bit more balance, for

my own sanity.

So those were the main reasons, but I also have a ton of friends in LA, too, that were pulling me there.

L.A. is the type of place where you can’t really beat the quality of living. I might be spending the same amount as far as rent goes but I have more time and I’m able to balance out my day a little bit more. Plus the sun is always out so it’s easier on the body and brain.

What are the things that you’ve

valued the most by being between New York and L.A.? Does one feel

like a better fit than the other?

That’s a good question. Well, I’ve mainly valued the music. Being in New York I feel like I developed faster, just because it’s 24/7 and a lot of the guys that I looked up to and wanted to be around were in New York. By being there I found out who I was and what I actually wanted to do. Also, I always wanted to be involved in more than one thing and New York was the place for me to do that. Whether I wanted to play gospel music, or jazz, or hip hop, it was all happening in that space. I feel like New York made me a little stronger.

L.A. has a beautiful music scene. It’s a little more close knit because you have a lot of people who are from there and who grow up with each other. It’s almost like these little pockets of families who grow up with this musical journey.

It feels as though it’s a little more open now, especially with a lot of the younger dudes, where you get into playing more jazz and experimental music. Although it is still a part of it, it’s just not as studio focused. On the flip side of that, L.A. is teaching me a lot about the studio because it’s sort of the mecca for that. I’m learning lots about mics and EQs.

I do feel like the two places are still connected. I used to say that if you wanted to become a hardcore musician then you move to New York, and if you wanted to have more stability then you’d move to L.A., but it’s changing, mainly because of the younger generation and having access to the internet.

What was your experience like growing up as a kid?

Well, being in the Bay Area, there was a vast amount of artistry, from Tower of Power, to Sly and the Family Stone, from the Black Panther movement to the Hawkins Family. It was really cool to be in an environment where art was prominent.

I was fortunate to go to Berkeley High School where I met Thomas Pridgen and a lot of other amazing musicians. Even though it was a public school, the school band was really good and it had this stature for being one of the best in the country. That school was just a bunch of creatives.

I was there with Daveed Diggs, who was in Hamilton, as well as Chinaka Hodges. There were a bunch of different creatives there and that was really cool to be around. There were also outreach programs like the Young Musician’s Program, which is a summer school at the University of California, Berkeley for kids under eighteen and they’re basically teaching you at a college level. From being there, and being around the people that I grew up with, I knew what I wanted to pursue. I knew as a kid that I had a talent but I didn’t start to exude in it until after I left the Bay Area.

I was very active in music, plus my mother is also a gospel musician, so I was learning a lot. I was fortunate enough to have good parents who helped me to cultivate my craft and I’m very thankful for having been in that environment. I had opportunities to play small gigs. I really commend my mother because from the ages of thirteen to fifteen, she used to let me play at late night clubs and she’d come pick me up at two in the morning. I’m very fortunate that she allowed me to have that outlet.

That’s some good parenting.

Yeah! She’s a musician as well so she saw an opportunity for me to go in a direction that she didn’t really go in. She would go out on tour but it was a struggle because she wanted to be at home with the family. Whenever I wanted to practice or hang out with musicians or go to shows, she was always there to take me. At a young age I got to see a lot of guys playing who would be coming through the Bay Area, like Dennis Chambers and Brian Blade.

You’ve been friends with Thomas

Pridgen for a long time.

Yeah, we grew up together. I met Thomas

when I was 8, and I think he was 9. I actually just talked to him

earlier. To this day he’s like my brother. I’m fortunate enough to have

grown up with a guy like that, especially with playing drums.

Were you learning from each other?

Man, he was at such a high level that I was learning from him, for sure. He had access to a lot of the guys that we were watching and he was exposed to the instrument at a very young age. I think the most that I gained from Thomas was how to find yourself through the instrument and how to really dedicate yourself to the craft. We used to cut high school together to go shed the whole day. We’d meet up at school, go to his house to play drums, and then go back to school for band. (laughs)

I also met Ronald

Bruner through Thomas. I remember that Thomas would call Ronald and

they would play drums over the phone! Those two are my brothers for

sure.

Is Ronald still playing with Kamasi Washington?

Yeah, he is. I’m not sure what Thomas is doing right now but he does everything. I know that he was playing with Residente and before that Trash Talk. He’s playing a lot in the bay area and he’s always super active. I got to see him play with The Mars Volta and that was unreal.

Yeah. All of the drummers who have

passed through that band have been phenomenal.

Yeah! Jon

Theodore, Deantoni Parks,

Thomas, Dave Elitch. All special dudes, for sure.

When you left the Bay Area, did you

go straight to New York?

Not right away. I

ended up auditioning for the Dave Brubeck Institute, which is at the

University of Pacific, in Stockton, California. So I studied there

for two years before moving to New York, which was actually a smart

move because when I look back on myself at eighteen, I wouldn’t have

been ready for New York, as a human and as a musician.

It was cool to still be somewhat closer to home and to still be able to take the time to really figure it out. Eric Moore also lived in Stockton, California so I became really good buddies with him. He was my shed partner and we played drums every single day. Being there allowed me to really focus in on the instrument and that’s where it hit me that I wanted to do this.

I learned that in order to be good you had to put in the time and the work. So that put me in a really good space and it became a habit of me just trying to get better.

Was it after studying in California

that you went to the Julliard School for Music in New York?

I auditioned for

the New School and Julliard, where I ended up getting a full

scholarship. Once I saw the curriculum though I realised that it

wasn’t for me. Their curriculum was something that I had already been

through, with all of my studies at high school and also at the

Brubeck Institute.

I actually dropped out on the first day of school. I woke up and just thought, ‘I can’t do this’. I didn’t even go to class, I went straight to the Dean and told him that it wasn’t for me.

At

the time there were so many musicians that I looked up to, from

Steve Coleman to Yosvany Terry to Josh Roseman… I mean, Steve

Coleman had a workshop every Monday at the Jazz Gallery and I used to

go there and study. Then it was really about playing and learning

what that experience was like, so I dropped out of school. It was the

best thing for me because I was just ready to play.

That was a smart move.

Yeah. I mean, sometimes I look back on it and it probably would’ve been easy to go back to school and to get a degree and get my masters but I wasn’t in that headspace. I was ready to play and I was on a mission to try to get better. So I dropped out of Julliard and spent one year in New York working. I got a day job at Guitar Centre just so I could survive. After six months I thought, 'if I’m really going to do this, I just have to fall face first’. I had to be involved in anything and everything that I could, from a restaurant gig to a jazz gig. I knew it was going to be really hard but I had to do it.

After that first year there I ended up going back to school. I went to the Manhattan School for Music and that’s when I met other cool musicians and started to build a name for myself. While I was in school I got the call play with Kenny Garrett and after that I started touring.

After leaving Julliard and taking a year to work, do you feel like you benefitted from not fully going down the academic route at that point?

Absolutely. It

felt like a better move for me to do that.

I still consider myself to be a jazz musician, and in New York you still have the masters there who are the great practitioners of this music. I was going to shows and sitting right up under the drums and watching everyone from Brian Blade to Billy Hart, and I even got see Max Roach when he was still around. So it was about going to check out the masters, asking them questions and really learning about the culture.

If I was doing a hip hop gig, I was going to the hip hop clubs and asking Rich Medina what albums to check out. CBGBs was still around, so I got to and see what that was like and to experience that. So it was about learning the culture of each music and I feel like that’s something that they aren’t going to teach you in school. It’s something you have to find for yourself.

What would you like to see implemented in music education that wasn’t present when you were studying, or that you feel is just absent?

That’s a really good question. I think allowing more students the opportunity to check out the masters. They need to be bringing in people who have the real experience and not just a teacher who went to school, learned the methods and then says, 'here’s how to be a jazz musician’. That’s not the way to do it.

Colleges bring in master musicians but it’s only a minuscule part of the thing. It’d be great to be able to call someone like Billy Hart and to take students to them, to see the show. Also, it’s an economic game. Berkley and the Manhattan School for Music have the money to do it but I think it’s really about grabbing a hold of the experience. You’re not going to really grow unless you’re out there doing it. You can be taught a bunch of theory but to be in the moment and playing is where it’s at.

You’ve collaborated with a multitude

of different artists including Flying Lotus, Thundercat and Esperanza

Spalding, How have you found it adapting to all of those different

situations?

It’s all about connecting the line. They’re all unique individuals but they’re also very like-minded. They’re vessels submitting to this music and they’re all willing to grow. I feel like the more music you go and check out, the easier it is to connect the dots and be able to adapt.

I learned that I would play differently in certain situations, whether I was playing with Esperanza Spalding or Thundercat, but it was really all about submitting to the music and setting a foundation to make things feel good. It’s all music and I just want to be able to bring out the characteristics of what the artist is trying to say. At the end of the day it’s about having the mindset that it’s really not about me. It’s about a bigger picture and to be a vessel in a way that gives someone hope or inspiration throughout their daily life.

The physical aspect between the people I play with can also be different. Once I started playing with Thundercat, I knew that I could play in that style but I knew that I didn’t have the physical capability and stamina to do it. So I had to go back to the drawing board in some ways. I even went to Thomas (Pridgen) and asked him, 'how do you not get tired playing these gigs?’ He told me that not only do you have to play like that in your practice but you have to take care of yourself by getting proper sleep, drinking a lot of water and stretching. Over time it became easier.

I had a regimen

within my practice where I would work on independence and groove, but

then it just became about playing and getting my body in the flow. It takes a lot of patience to understand

what works and how your body reacts to certain things, like when you

play from fast to slow. Trying to relax the mind and body within

that. It really comes down to submitting to it.

So it’s mainly

been the physical changes between gigs that I’ve had to adapt to more

than the musical ones. I guess there are stylistic things which are

different. I mean, with Esperanza it’ll be sort of samba and

bossanova, but with Thundercat it’s more backbeat rock. Essentially it’s

about grooving, making the music feel good and always being open to

learning. I try not to be single-minded in music, because the more

things you’re able to expose yourself to, the greater

the musical language is that you can draw from.

It’s about always

being 100% in it. Always checking out music and going to shows.

Always talking about music, and just being a musical nerd. The more

experience you get the more natural it becomes.

You played with Herbie Hancock. What was it like getting that call?

Bro. That was

crazy. Playing with Herbie was a surreal experience. He’s been a

major influence on me throughout my musical journey so it was a dream

come true.

I think it was Terrence Martin that recommended me. I got the call and did the rehearsal… I rarely get nervous but I was starstruck. I couldn’t believe it was happening. For the first few days of the tour, it took me a little while to get over the hump. Like, 'oh, man, I’m on an airplane with Herbie Hancock! I’m eating with Herbie Hancock!’ (laughs) On the third or forth day he walked up to me and said, 'Yo, Justin! You’ve been killing it these last few days!’ And it just kind of took a load off me, because he was cool and he was feeling what I was doing.

I got to ask him a bunch of questions about Miles (Davis) and Tony (Williams). He actually told me that Tony played with John Coltrane, which was mind boggling to me.

What period would this have been in?

This would have been in the '60s. Herbie was really good friends with Tony, so I asked him: 'Man, did Tony ever play with Coltrane?’ and he said that, yes, he did. There was a week at Birdland where something had happened with Elvin (Jones), where I think he might have got arrested, I believe. So Coltrane asked Tony to play that whole week. I asked Herbie, 'Are there any recordings of it?’ and he said, “Yeah. I believe his wife has the recordings.” So it was documented.

Herbie never heard the recordings but he saw Tony afterwards and he said that Coltrane was the reason why Tony switched to playing with bigger sticks. Coltrane had so much stamina from playing as much as he did that Tony wanted to get on that same level. This was in the '60s, so already early on he was trying to get more energy and more power after playing with Coltrane. So that was a really cool moment that he shared with me.

Herbie’s full spectrum, on a musical level and on a human level. He’s extremely open and is very technically minded. We were all sitting at the dinner table one night and we’re taking pictures on our phones. Herbie walks up and says, “you guys want to see something? You ever seen a 3D camera phone?” A company called Red made the first 3D camera phone and they sent him the first one. He was like, “yeah, they sent me the aluminium one. I asked for the titanium one, so that’ll be waiting for me when I get back!” He’s always been that guy. When Sony first started making CDs, they called him. When Midi was first starting to be used, he was one of the first guys to know about it. So it was just really cool to be in that space. I got to chat to him everyday.

He’s not going back but he’s moving forward into the beyond. I’ll definitely cherish that moment [of playing with him] for the rest of my life. I knew going into it that I had be humble; to be thankful and learn as much as I could from Herbie. It definitely made me a better musician and a better human, just from that one month on the road with him. Just seeing how focused he is… it was unreal.

What have been some of the

milestones in your playing that have pushed you creatively?

Meeting Herbie was

definitely a milestone for me. Anytime I get to talk to one of the

masters, I feel like that makes me a stronger human and a

stronger musician. It makes me more confident in what I want to

achieve. Playing with Kenny Garrett… as well as being able to

play with my peers, you know. It’s really cool to just be able to

grow together.

The day I heard Caravan by Art Blakey when I was ten years old blew my mind. Just hearing how he played the drums and how much authority he had over the instrument was one of those moments where I thought, 'oh, so that’s how you do it!’

For me it’s about

adapting to the energy of the room and being open in that sense as to

how I can inspire someone. It goes back to submitting to the music.

All of the practice, as well as checking out videos and seeing

drummers live definitely helps, but I also want to be a musician that

is completely in the moment. I don’t ever want to go onto the

bandstand thinking that I know what’s going to happen. I want to have

a mindset that is ready to expect the unexpected and to always play

what is called for in the music. You have to be able to open yourself

up to what’s going to come out naturally and not try to force anything

to come out.

All of those

things have made me a better musician.

What’s something that you’ve been paying attention to recently that’s been inspiring you, either musically or non-musicially?

Well, I’m not

really political but I am paying more attention to issues in the

world, because as a black man, I feel like I have no choice, you

know? I have no choice but to find a way to dumb down the bullshit. So I’m trying to

pay more attention to what’s going on in the world; to try and

inspire someone to get through, because these are tough times.

I’ve been given a

gift… in church you learn at a very young age that it’s not about

the accolades or being seen, it’s about being a spiritual vessel, to

give back and to give praise to the most high.

I guess musically I’m really paying a lot of attention to the drum community and seeing how social media is having an affect on it. I saw the transition with my generation, so it’s a little harder for me to go all in and just post things up all of the time. I don’t want to over expose myself, but I also just want to be a positive example for someone and to inspire the next generation of younger players, to show them that it’s possible. I’m also paying more attention to my health, because with the older I get and the more I’m touring, my health is key to staying strong.

You put out the Nyeusi record a

little while ago. Are planning on doing anything more with that

project?

I’m still trying

to figure it out. I am starting to hear the music and I am starting

to get the inspiration to do another album, but I’m not sure if I’m

going to call it Nyeusi, because I’m in a different space. With where

my life is moving, and all the things I draw inspiration from, there

might be a different message.

I wanted Nyeusi to be a theme of who I am more than anything. Even though it’s my music it’s still not about me whatsoever, and I wanted room for all the other musicians to speak in that project. I mean, I might do a Nyeusi II, just because it was well received and people gravitated towards it, which gave me the push to keep going.

It took a lot of energy and a lot of time to put that album out, and once it was out I didn’t really do much touring. There was another side that I had to learn about which was how to be an artist and to present the music. Now, I’m more in a head space of wanting to play and wanting to get the music out live and create more content. So it’s very loose and in the air, but I will say that for 2020 I’ll be doing more shows with Nyeusi and I’m going to have more live content out, so that’s where I’m at with it.

Any European dates for 2020?

Yeah, in the fall,

and maybe even later on, and then just doing some shows in New York

and L.A..

If you could give three albums to a

drummer, which would you choose and why?

This is really difficult. Man.

Ok, I would say:

James Brown –

Funky Drummer, or The Payback. Why James Brown? Because that’s where

hip-hop is coming out of, with backbeats and breakbeats. So it can

provide a good foundation for someone wanting to become a

hip-hop drummer and to have an understanding of the language. Not

just James Brown but soul and funk music.

Miles Davis –

Kind of Blue. Just because that’s a quintessential record for jazz.

You can hear where it’s coming from and where it’s going.

Stevie Wonder –

Songs in the Key of Life. He’s an amazing songwriter and he plays

every instrument. Being a drummer, you can get so caught up in the

drums that you lose sight of what the message is, and Stevie Wonder

is a beautiful storyteller. The music is killing but there’s also a

message which makes you want to investigate the lyrics. You get a

sense of purpose and what music is actually meant for; what your role

is as a drummer, too.

What are some of the things that are currently challenging you, either as a musician or just on a human level?

On a human level,

learning to love and respect everyone for who they are and what they

do. To never knock another person’s path. To always be encouraging

and spread love, if you will.

As a player, and this is going to sound crazy, but playing louder and faster. (laughs)

I mean, that’s a really hard thing for me so I’m really trying to develop and get my phrases and musical statements to be a lot stronger, so that it becomes a part of a language and not just a lick or a fill. So I really want to keep developing and getting better as a person.

Good answer. Thanks for taking the

time to sit down and do this.

Man, no problem! Thanks for asking!

Interview & live photo by Dave Jones.

PHOTO: Drummer Justin Brown’s leader album features two keyboardists. (Photo: Hadas)

The electro-funk fusion album Nyeusi (Biophilia) marks drummer Justin Brown’s debut as a bandleader, but he’s no newcomer. The 34-year-old has spent about two decades cultivating his reputation as a first-class jazz musician.

By the time he graduated from high school, Brown was a veteran of both the Grammy Band and the Brubeck Institute. He forsook a free ride to The Juilliard School to tour with saxophonist Kenny Garrett and trombonist Josh Roseman. A few years later, he began working regularly in bands led by trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire and pianist Gerald Clayton, both childhood friends. He was runner-up in the 2012 Thelonious Monk International Drums Competition, and since 2014 he has been the drummer for genre-busting bassist/vocalist Thundercat.

“It’s his curiosity and his commitment to the craft,” said Akinmusire, explaining why he’s worked with Brown for so long. “Every time we play together, he brings something new.”

What, then, took so long to record the debut?

“I guess my frame of thinking with anything is just patience,” said the bicoastal Brown, speaking by phone from the Bay Area. “I was writing songs here and there, and taking the opportunity to perform as a bandleader in places like [New York’s] Jazz Gallery. But it was something I didn’t want to rush, because I’m still learning throughout the process.”

Nyeusi (Swahili for “black”) includes 11 original compositions written during the past 10 years. Much of the album—featuring Jason Lindner and Fabian Almazan (both on keyboards), Mark Shim (electronic wind controller) and Burniss Earl Travis (bass)—was recorded in 2015. One of the album’s two non-original tracks is a version of Tony Williams’ 1971 tune “Circa 45,” while the influence of hip-hop is obvious on tunes like “Replenish” and “FYFO,” and interludes “Waiting (DUSK)” and “At Peace (DAWN)” skirt the avant-garde.

Just as he exercised patience in completing Nyeusi, Brown is in no particular hurry to follow it up. Instead, he said, his next step will be “becoming a better human. I want to help us come together and help one another, you know? A better human and a better musician: I’m just trying to do my part.” DB

https://jazztimes.com/features/profiles/justin-brown-reflecting-the-now/

Justin Brown: Reflecting the Now

For his debut outing, the drummer puts a modern spin on classic jazz-funk

UPDATED

April 25, 2019

by KEN MICALLEF

JazzTimes

Justin Brown (photo: Hadas)

“To be a black artist in these times means that I have to present myself in a positive manner,” Brown says on the phone from Amsterdam. “I have to be an example for young kids who look up to me. I want to utilize my platform in an honest, positive way to give back, and to be a vessel to inspire. I’ve been given this gift to play music. The only true gratification is inspiring people and figuring out a way to give people hope through the music.”

Brown titled his full-length debut as a leader Nyeusi (Biophilia), which means “black” in Swahili, a language the 34-year-old studied in his California high school. His colleagues on the album include Fabian Almazan and Jason Lindner (keyboards), Mark Shim (electronic wind controller), and Burniss Earl Travis II (bass). Nyeusi (pronounced “nee-o-see”) recalls the golden age of ’70s jazz-funk—think the Headhunters’ Thrust, George Duke’s The Aura Will Prevail, or Tony Williams Lifetime’s Believe It—with a touch of the surreal. Brown’s lightning-sharp drumming propels his front-line players into flights of improvisational wizardry. Shim’s solos soar over Almazan’s honeyed Wurlitzer and Lindner’s searing analog synths, as the thudding drums and papery cymbals agitate all within.

“Throughout writing and workshopping the material I used different configurations,” Brown says, “even playing the music in acoustic settings. But ultimately, I wanted music that reflected the now. I’m inspired by a lot of music from the ’70s and ’60s, but what’s happening in the now sounded better with this instrumentation.”

Nyeusi covers a broad range of textures and atmospheres, all within Brown’s “now”-inspired vision. Tony Williams’ “Circa 45” enters lazily, Shim’s loping melodies and Brown’s wind-flapping rhythms evoking a deranged sitcom theme. The catchy melody of “Lesson 1: Dance” is relayed via brooding synths and sonar-like sound effects. “Jupiter’s Giant Red Spot” increases the velocity—it’s basically a through-composed drum solo bathed in woozy Wurlitzer melodies—while the low-riding “Replenish” dials the pace back down. “‘Replenish’ came out of a moment realizing that, as a traveling musician, you just have to slow down and decompress,” its author explains. “You can’t always go with the in crowd, you have to fall back and look at yourself. Check that you’re okay. Maybe someone in their life will hear ‘Replenish’ as reflective.”

Befitting Nyeusi’s retro vibe, Brown’s drums sound flat and muffled, as if he transported himself and his Craviotto drum set (augmented by two side snares, a Leedy and a “lovely old” 10×15 Ludwig) to 1975 and recorded at L.A.’s Sound City. His cymbals are similarly trashy-sounding, like broken brass and shattered bells. “It was about making sure the funk was in it,” he says. “When you go back and listen to James Gadson or Bernard Purdie, sometimes their toms and bass drums didn’t have bottom heads. The drums are really dead-sounding. So I tuned my drums really low. I even put cloth on the floor tom to deaden it. I stacked my Istanbul Agop hand-hammered cymbals, and put shakers, a tambourine, or a splash cymbal on the snare drum. Sometimes that makes the drums sound programmed. But everything is played live.”

How will today’s screen-addicted music fans react to Nyeusi’s J Dilla-warped future soul?

“We live in an age where there’s a generation that’s exposed to everything because of the internet,” Brown responds. “But they’re also using it as a tool to learn and dissect music. Therefore, the palette is a lot wider now, so people are more open to creative improvisational instrumental music. Some people have reached out to say this album keeps them going forward in music, and that’s ultimately my goal.”

A native of Richmond, Calif., Brown grew up surrounded by music; his mother, Nona Brown, is a pianist and singer who worked extensively with the Edwin Hawkins Singers. After attending Stockton’s Brubeck Institute for two years, Brown relocated to New York, where he promptly blew off a full scholarship to the Juilliard School. “Sometimes I think it would have been nice to say, ‘Yeah, I went to Juilliard,’ but I’m very happy with my decision and where my life is and where it’s going,” he says.

Brown’s ongoing work with Akinmusire, Thundercat, Yosvany Terry, and Linda Oh has been supplemented by yet-to-be-released recordings with Flying Lotus and John Escreet, the latter featuring Brown playing double drums with Eric Harland.

“I definitely think long-term,” he says. “One goal is bettering myself as a person spiritually, mentally, and musically. I want to write and continue to make albums and figure out ways to give back, not only through music but through actions, whether that’s teaching or helping others. I just want to live and learn and write and let the music speak for itself.”

Originally Published October 8, 2018

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/27/arts/music/justin-brown-nyeusi.html

Justin Brown Is a Monster on Drums. Now He’s a Bandleader, Too.

The drummer Justin Brown first arrived in New York almost 15 years ago, scholarship in hand, to attend Juilliard. He lasted at school for exactly one day.

He said he looked at the traditional jazz-based curriculum and made the decision to leave immediately. “Man, this is stuff that I kind of have studied already,” he remembered thinking. “I’m at a point to expand and grow.”

Sitting in Harlem’s Jackie Robinson Park on a recent evening, he spoke with a mix of shy introspection and lighthearted confidence. “I just couldn’t help but to feel that a real jazz musician is going to adapt to new music,” he said. “They’re not going to have one level or one way of thinking.”

So Mr. Brown quit school and set about finding as much work as possible. He joined rock bands, attended hip-hop and R&B jam sessions religiously, practiced nonstop, sought out mentors. It started paying off immediately. Today, at 34, he is one of the most highly regarded drummers in music.

For many years he has held down the drum chair for Ambrose Akinmusire, probably jazz’s most influential bandleader under 40. And Mr. Brown has recently been playing festivals and rock clubs around the world with Stephen Bruner, known as Thundercat, the oddball prince of modern-day fusion, who skates between jazz, hip-hop and psychedelia. (Mr. Brown also collaborates with Flying Lotus, Esperanza Spalding and Terence Blanchard, to name just a few.)

On Friday Mr. Brown opens a new chapter, releasing “Nyeusi,” his debut album as a bandleader. (He celebrates the release with a show that night at Nublu 151, in Alphabet City.) It would be too simple to call the record a hybrid of his work with Mr. Akinmusire and Mr. Bruner, though stylistically it does incorporate both Mr. Akinmusire’s flair for irresolution and the woozy, wafting ambrosia of Mr. Bruner’s music.

[Never miss a pop music story: Sign up for our weekly newsletter, Louder.]

Mostly it’s a ringing testament to Mr. Brown’s own, unmapped path. Burniss Earl Travis’s fortified bass and the swarming force of Mr. Brown’s drums work as a kind of magnetic therapy, softening your senses and opening your ears. Above, the keyboards and synths of Fabian Almazan and Jason Lindner swim together, Mark Shim’s electronic wind instrument curving and drifting against them.

You can hear the album as the next step in a hybrid subgenre — the stuff of J Dilla and Madlib, Karriem Riggins and Chris Dave and Jamire Williams. It’s dreamy, air-and-stars beat music that retains a hardened undertow. You can also hear it as a gentle reminder that gospel music lies near the heart of American popular music: The taut, thwacked, polyrhythmic musculature of African-American church drumming offers depth and flexibility across styles.

“Nyeusi” also works as a revival of the electrified fusion of the 1970s, a maligned era that’s being reclaimed by many adventurous improvisers these days. (The only cover on the album is “Circa 45,” a Tony Williams number from 1971)

The album’s title, which Mr. Brown also uses as this band’s name, means black in Swahili. (He learned the language in high school.) He likes the various meanings of the word — the way its aesthetic implications are now inseparable from its political and historic ones, and the way in which darkness and beauty can cohabitate within the color. “You can think of it as about being a black man, you can think of the color itself,” he said. “There’s some density in the record, but it’s got a lot of beauty in there too. It connects with culture, learning, growing.”

Jazz, as a largely instrumental music, has always been affective as well as linguistic — some of its best moments involve moving beyond artistic idiom or music-as-language, drawing more directly from intuition and personal hybridity. “Nyeusi” gets there.

“I wanted to have these ethereal developments sort of represent emotion,” he said. “It’s not just like you have the harmony and the melody and that’s it.”

Mr. Akinmusire describes playing with Mr. Brown in admiringly abstract terms. “It feels like you’re making music with an element. He feels like nature, he feels like water, like the earth,” he said. “What nature does, it just blows a little wind in your face, and that can mean that there’s a storm coming. The tide coming in means something. I think that’s something that he’s developed in his playing more recently.”

It helps that Mr. Brown embeds so many crossing cadences and interleaved harmonies in this music that you have no choice: You can only lose track of things, sit back, feel and absorb.

“It’s almost like he has an unlimited number of graphs going on at the same time, and they’re all grooving,” Mr. Akinmusire said. As a result, when trying out ideas over Mr. Brown’s beats, he added, “almost anything works.”

Mr. Bruner is just as succinct. “Justin is a monster, to say the least, on his instrument,” he said. “His playing is beyond.”

Mr. Brown grew up in Richmond, Calif., just north of Oakland, in a musical family. His mother, Nona Brown, is a respected singer and pianist who worked for years with the gospel icon Edwin Hawkins. Richmond was a hard place to raise a family; Mr. Brown remembers his family’s car being stolen, his house being robbed. But before any of that, he recalls seeing the impact of music on a religious congregation.

“They call it the Holy Ghost — when you see something like that hit someone,” he said. “Even though I couldn’t really understand it, I was absorbing it.”

He added: “You start to realize that you’re just a vessel.”

He met Mr. Akinmusire at Berkeley High School, where they were part of a crowd of young musicians who would eventually become pros (Jonathan Finlayson, Thomas Pridgen, Charles Altura). After quitting Juilliard, Mr. Brown tried one more time to find an academic setting that might work, enrolling in the Manhattan School of Music a year later. But just as the semester started, he got called to go on tour with Kenny Garrett, the primo alto saxophonist whose band has launched more than a few careers.

By 2012, he was the broad favorite to win the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition, focused that year on the drums. But after a blistering, pyrotechnic performance, Mr. Brown placed second. He missed the grand prize, which included a contract with Concord Records, but he gained some perspective.

“Music is not meant for a competition in the first place,” he said. “It goes back to spirituality, and why I made this album. I made this album to say to myself, ‘Keep going. There’s a vision. You have a purpose. Give back to the world, give back to the trees.’”

https://www.drumeo.com/beat/justin-brown-drumeo-gab-podcast-135/

by Seamus Evely / Drumeo Gab #135 /

Oct 7

“You wanna be everything but have the sense that you are nothing at all.”

Justin Brown is a world-class, bi-coastal musician originally from Oakland, California. He has gained a notable reputation as both a bandleader (NYEUSI) and a sideman (the latter being for Thundercat, Ambrose Akinmusire, Christian McBride, Kenny Garrett, and Esperanza Spalding among others).

Justin grew up with gospel music as his mother, Nona is a gospel singer and pianist. Music chose Justin, not the other way around. As he explains in this interview, when his mother was pregnant with Justin, she would feel him kicking to the beat as she played her music. He attended Berkeley High School and attended a summer music program for several years. Both he and Ambrose Akinmusire went to the same school and began their friendship there.

Justin would eventually receive a fully paid scholarship to attend the esteemed music school, Juilliard. This lasted for one day. Justin was offered the opportunity to tour and also felt that for him to grow he had to experience music in the real world instead of being subjected to more traditional methods of education. Essentially, he wanted to form his ideas about music on his terms.

To my knowledge, this is the first-ever podcast episode featuring Justin. He has received a lot of positive press concerning his debut album, NYEUSI, but until now we have not heard him speak on a podcast about his life, career, and artistic process.

In this episode:

You will hear about:

- Justin’s early formative years with music

- Does natural talent exist?

- Justin’s beliefs on giving back

- The importance of patience

- The costs involved in getting where he is with his craft

- Justin’s approach to leading his own band

- How to maintain control of one’s self when we become overloaded with sensation during a performance

- Justin’s thoughts on improvised music

- Why we should abandon the security of being a big fish in a small pond

Why you should listen:

This episode is a reminder of why we must remain humble in the pursuit of knowledge and our greatness. It can be easy to become disenchanted with all of what we don’t understand and feeling defeated that we can’t reach our fullest potential.

Justin is a world-class musician who has devoted his life to music. Just listen to how sincerely humble he is. Justin is a fantastic example of a person who understands the importance of learning, giving back, being honest, working hard and exercising patience. We can all use this message to check ourselves from time to time.

Music used in this episode:

NYEUSI

“Lesson 1: Dance”

“Lots for Nothin’”

“Lesson 2: Play”

“Waiting on Aubade”

“Entering Purgatory”

“Jupiter’s Giant Red Spot”

“Burniss”

“Circa 45”

Follow Justin:

Instagram

Twitter

YouTube

Get NYEUSI

Follow Drumeo Gab:

Instagram

Facebook

"All About Love": A Conversation with Justin Brown

January 26, 2012

Justin Brown has a busy 2019 with at least three different touring projects.

When drummer Justin Brown released his debut album Nyeusi in June, he set his sights on taking his band out on the road early this year. Then work got in the way. Rather than lead his own ensemble on the road, Brown has the first half of 2019 booked in the bands of trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire, bassist Thundercat and saxophonist Chris Potter, and he’s hoping that the pianist he toured with in South America in November, Herbie Hancock, will give him a call as well.