AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING, 2022

VOLUME ELEVEN NUMBER TWO

ROSCOE MITCHELL

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

MORGAN GUERIN

(March 18-24)

KENNY KIRKLAND

(March 26-APRIL 1)

STACEY DILLARD

(April 2-8)

CHARENÉE WADE

(April 9-15)

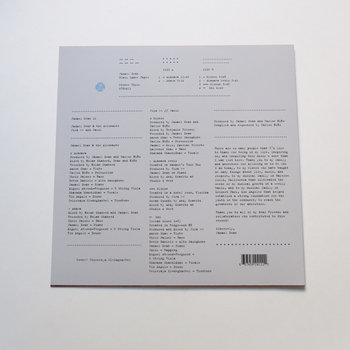

JAMAEL DEAN

(April 16-22)

MILES MOSELY

April 23-29)

JONTAVIOUS WILLIS

(April 30-May 7)

UNA MAE CARLISLE

(May 8-14)

JUSTIN BROWN

(May 15-21)

TYLER MITCHELL

(May 22-28)

BENJAMIN BOOKER

(May 29-June 4)

CHRIS BECK

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/jamael-dean-mn0003871612/biography

Jamael Dean

(b. 1998)

Artist Biography by Matt Collar

Pianist and producer Jamael Dean is a harmonically sophisticated pianist with a bent toward expansive, boundary-pushing jazz and hip-hop. A gifted player since his teens, he emerged in the 2010s in Los Angeles, playing with Kamasi Washington, Thundercat, and his grandfather, drummer Donald Dean, before issuing his 2019 Stones Throw debut, Black Space Tapes.

Born in 1998 in Bakersfield, California, Dean was introduced to music at a young age and initially started out on violin while in the third grade. At age nine, he was given a keyboard and soon began teaching himself how to play by ear. Under the guidance of his grandfather, longtime Les McCann and Yusef Lateef drummer Donald Dean, he became interested in jazz and spent much of his adolescence mentoring and playing gigs with the elder Dean. By his teens he was attending the prestigious Los Angeles County High School for the Arts, and studying under such well-respected veteran pianists as Doug Davis, Bill Cunliffe, and Eric Reed. Accolades followed, including a membership in the 2014-2016 Thelonious Monk Institute National Performing Arts High School Septet, winning a 2016 Dolo Coker Scholarship, and earning a spot on the 2016 Grammy Band Jazz Combo. His talent also caught the attention of players on the greater Los Angeles jazz scene, including saxophonist Kamasi Washington and bassist/singer Thundercat; both of whom took him on tour while he was still in high school. He began expanding his interests, crafting electronic beats on his computer and merging jazz, funk, and hip-hop. Following high school, he enrolled as a Jazz Performance major at the New School in New York City. In 2019, he released his debut album, the genre-bending Black Space Tapes on Stones Throw.

https://www.stonesthrow.com/artist/jamaeldean/

https://www.passionweiss.com/2020/02/27/jamael-dean-interview-stones-throw/

“Leimert Park is the Fountain of Youth:” An Interview with Jamael Dean

Photos by Sam Lee

To Pimp a Butterfly was released a half-decade ago to instant acclaim. It’s strong jazz modalities owed a lot to a gifted battery of musicians and producers including Terrace Martin, Josef Leimberg, Thundercat, and Kamasi Washington. All of whom released stellar jazz projects of their own shortly thereafter, with Kamasi’s debut The Epic gaining the most traction. So it’s safe to say the “LA jazz renaissance” has been around for quite some time. It’s added to the mythology of the city and its rich music history, but beyond the myths are genuine artists living and breathing in the city that forged them.

Because he’s played with scene linchpins like Kamasi and Thundercat, the pianist and keyboardist Jamael Dean has easily been linked to discussion of the “jazz renaissance.” However, the various musical projects that he’s released go much deeper than a quick check of the box. Released last November, his Stones Throw debut Black Space Tapes features a number of musicians from his circle, including scene driving force Carlos Niño as co-producer. Mixing various traditions, the album goes beyond conventional genre boxes to include ambient, jazz, beats, instrumental solos, field recordings, raps, and samples.

Often borrowing from Yoruba cosmology, the track titles reflect the spirituality that runs through his work. Black Space Tapes conceptualizes the color black as something original and elemental– what came before anything was. Whether it’s as the bandleader of The Afronauts, or as a keyboardist for the legendary L.A. jazz ensemble the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra, afrocentricity is ubiquitous within his practice. The deep connection to Black culture stems from his roots in Leimert Park and the surrounding community, a place that holds a special place for him.

I met Jamael in L.A. during the Thanksgiving holidays. We found ourselves hanging out at the Leimert Park landmark The World Stage, the house show series the “Garage” in Inglewood, and recording sessions at Bedrock.LA. Shortly thereafter, Jamael returned to New York where he studies jazz at the New School; this interview was conducted over the phone the following month. — Samuel Lamontagne

Generally speaking, what was your introduction to music?

Jamael Dean: My first experience with music […] According to my parents I started pulling out pots and pans and beating on them. But as early as I can remember, I always loved my grandfather’s playing. I don’t know if you’re familiar with him.

Yeah. Donald Dean.

Jamael Dean: Yeah. He used to take me around to gigs with him all the time. So I got to experience that part of the culture with him.

What drew you to playing keys and piano?

Jamael Dean: There were a couple different things that happened. I knew that if my grandfather played drums and I wanted to play with him, I couldn’t play drums. So piano was like the next best thing to me. Then around eight years old, Christmas came around and by that time my parents had cut out video games completely from my life. So they ended up getting me a small Yamaha keyboard for Christmas, one that you could get for $100 or something. I started playing by ear and later on I started taking lessons. That’s kind of how I got started.

Instead of playing video games, you were playing the Yamaha keyboard.

Jamael Dean: Yeah. I would end up practicing for like three hours a day on school days, and sometimes six or more on other days.

What would you say was your introduction to jazz? At what point do you remember being like “Oh, this is jazz.”

Jamael Dean: I always kind of knew jazz because my dad used to have this record that my grandfather was on called Swiss Movement in the car all the time. So he would play it and I used to love to sing along to the songs. I always asked my dad to play it. So I guess that would be the earliest experience.

On your album Black Space Tapes, there are straight jazz tunes and then beats. It’s all one in the same for you?

Jamael Dean: Yeah, very much so. And a lot of the beats sample the jazz stuff too. Some of the things came out by accident. I just liked the way it sounded because I was improvising. Then I decided to use it and improvise more on top of it. Expression is the key aspect of the music and I think it always has been. Even before it was known as jazz, when it was still one with the African drums that we used to play. I don’t know why we look at it different now and take the whole sacred aspect out of the music. But for people who are in tune with it, you can feel it in their music. Pharoah Sanders, Alice Coltrane, Sun Ra, even Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter. You have people who are very in tune with not only the cosmos but the science behind it as well. Music is a science, it’s dealing with frequency, which is the same thing as light. It’s the same thing as matter. It’s the same thing as me and you. So they’re teaching people how to live harmoniously through what they do.

How about your introduction to hip-hop? What is the first time you remember encountering it?

Jamael Dean: My sister Jasmine used to bump hip-hop a lot when I was younger. My parents used to not let me listen to it so much because of how vulgar it could be. But she had this one album in particular by Lil Wayne, Tha Carter III. And there was one song on there called “Phone Home,” where he’s talking like an alien.

“Phone Home!”

Jamael Dean: Yeaaah! As a kid I thought it was the tightest thing. The intro and everything that goes into it. So I guess that would be like my first moment really loving hip-hop. The thing that I thought was dope was how he rapped a whole skit for every song. Even “Dr. Carter” where he pretended to be a doctor and he was helping his patients with their flows and everything. Then when I heard Flying Lotus for the first time, it was the same type of feeling. It’s the same type of feeling you get when you hear Herbie Hancock’s Speak Like a Child or even Donuts by J Dilla.

Talk about The Afronauts. How did it form? How did it come to be?

Jamael Dean: We all have been playing together for a while at that point. We’ve been looking for a name. I’m sitting there, sitting at Devin’s [Daniels], just making beats. We used to hang out damn near every weekend. I used to call his mom my second mom. We were just chilling. And also thinking about space and everything as usual, thinking about astronauts in ways that related to Africa and yeah Afronauts. At that same time, I came up with the idea for Black Space Tapes too. So I feel like those ideas just birthed each other.

There are a lot of reference to African culture and heritage in your various musical projects. Why is it important for you to express this connection with Africa in the music?

Jamael Dean: Because everything works in loops, whether it’s time, whether it’s rhythm, harmony, or the way you think. It’s all loops. History will repeat itself. You can’t escape certain things and certain things will be able to be predicted to the exact detail. With that being said, I feel that it’s important to know where you come from in order to stand on the shoulders of the ancestors who came before you, and do that with integrity and character. So that’s kind of the idea with Black Space Tapes. The whole idea was that what came before anything is nothing. What is the color of nothing? We can see it in outer space. When comes nighttime, you see the color of nothing and it’s black. So that’s Black Space Tapes right there.

How did you connect with Stones Throw?

Jamael Dean: I connected with Stones Throw through Carlos Niño who knows Matthewdavid. Carlos gave me a residency at the Del Monte Speakeasy for a while. In fact, he was one of the first people who started supporting The Afronauts. After years of performing, we finally had some music ready to record. We did some mixes and everything. We were about to put it out on another label. But Carlos sent it to Stones Throw at the last minute and they were like “Oh snap! We want to release it”. So that happened. After a while I met with them in person; that was actually with Carlos again. So I guess Carlos is the main person behind it.

When and what was the residency at the Del Monte Speakeasy?

Jamael Dean: That was with The Afronauts. That might have been four years ago, in 2015 or 2016. Miguel Atwood-Ferguson had a residency that was every third Friday, and I think we were every fourth Thursday or something like that. That was every month. I kept it going for about a year into college and couldn’t keep it going. But it was cool because when I was gone I started letting Aaron and Lawrence Shaw run it, and they started coming out with all the Black Nile stuff.

What was your introduction to the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra? Do you remember the first time you heard about it? Pretty much from birth too I guess because your grandpa is part of it.

Jamael Dean: That was actually on some Congo Square shit man. I used to live in Bakersfield at that time, so my parents took me to L.A back and forth every weekend. I was part of JazzAmerica. So I played there in the morning. Then later on we went to Leimert Park. I saw Mekala [Session] there, and Kamasi [Washington] was playing with the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra. Michael Session was there too. Michael saw my grandpa and was telling him how I play piano, so they just got me up there for a song. I just started playing with them. The sense that I felt was freedom. The music wasn’t easy. It was something that for a 12-year-old who first starts playing is really difficult. So I was nervous. But while playing, I just felt uplifted. It was support from something that wasn’t visually in front of me, but connected me to the people through the sounds. The fact that it was in Leimert Park too. A whole cultural center with the big water fountain in the center that people gather around and drum around all the time. That’s why I say it’s like that for me, it’s the whole spirit of the music right there. Jazz came out of Congo Square. There’s different Congo Squares throughout America. So it’s not just jazz, hip-hop and culture in L.A but all throughout America and the African diaspora. At the end of the day, the first people who are on this planet that birthed all of our ideas about existence were from that place. So it’s down to the core with it.

You mentioned a program you were part of called JazzAmerica. What was it?

Jamael Dean: That program was founded by Buddy Colette. It was about getting young kids in a band to essentially help preserve the tradition. The winter time would be dedicated to music of the 1930s and earlier, while the summertime would be stuff from the 1960s and later. So, as young kids, we would cover a whole lot of different jazz music in that band.

Knowing your grandpa has been part of the Arkestra for a long time, and yourself being part of it now. What does it mean to you to play and be part of the Ark?

Jamael Dean: From the very beginning, it was like not knowing your family and being introduced for the first time. I’ve known them for a while now and developed really good relationships with a lot of people. It has a whole bunch of different characters. It’s really the main inspiration behind my art and what I do. Being a kid without video games and having to do a whole bunch of work all the time, people around you start to matter a lot. Now it’s just about learning and maturing with myself while still maintaining that. But they definitely helped my sense of respect and discipline as a man, as a human being. The Arkestra is definitely a teaching experience.

What does Horace Tapscott, the founder of the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra mean to you?

Jamael Dean: To me Horace represents teaching, healing. He’s very much the main source about it. You hear stories about how some people didn’t know how to play music so he would write them simpler parts and have them play and fuel their love for music. He understood the healing power of teaching. He’s like the epitome of harmony. It’s funny because a lot of his chords sometimes can be dissonant. He liked to wake people up with his sound, which is another thing I love about Horace. He’s not going to let you sleep through no music. I sometimes find myself falling asleep to music, so Horace was definitely the man. His compositions are crazy too.

You are one of the pianists/keyboardists in the Arkestra. Do you feel a special connection with Horace because you two share the same instrument?

Jamael Dean: I feel that way for several different reasons. For example, one of the other students he had was Nate Morgan. And Nate Morgan was with Nedra Wheeler, who when I first moved out to L.A had this scholarship program that she was teaching called the Roderick D. Jones scholarship Foundation, where she taught and mentor me. So it’s directly linked up to them and their realm of thinking and their philosophies. So even outside of just knowing Mekala, or getting the opportunity to play with the Arkestra, a lot of the teachers and elders have played a whole factor in that. Not only that, the Ark was the symbol of the bigger community.

We were talking about Leimert Park earlier. How does it resonate with you?

Jamael Dean: Leimert Park is the fountain of youth – to put it simply. I think people are realizing that, and that’s why it’s getting gentrified. That’s why people are coming through, buildings are changing and all of that. But you know what I mean, it’s like the Black Hollywood. You have Horace Tapscott’s name in plaque on the ground where everybody can see, you have Billy Higgins, Charles Mingus, Barbara Morrison. You have so many elders in our community who help. So it’s really just the fountain of youth. It’s a place to immortalize our community and more specifically, the Black people who get overlooked on a daily basis, the men, the women, the children, who can be represented through us as The Afronauts, and the elders through the Arkestra.

https://daily.bandcamp.com/features/jamael-dean-black-space-tapes-interview

FEATURES

Jamael Dean’s Spiritual Jazz

By

Marcus J. Moore

·

November 14, 2019

Talking to pianist, producer, and rapper Jamael Dean is like talking to a wise elder. It’s a cold, rainy Sunday, and the 21-year-old is in his apartment in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, breaking down the components of Yoruba culture. “It’s the spirit of nothing that expanded the universe into what it is now, but it’s almost like an unfathomable wisdom as well,” he says of Akamara, which, in Yoruba cosmology is the source of all existence. It’s also the basis of “Akamara,” the sprawling opening track on Black Space Tapes, Dean’s recently released debut album. It’s a slow-churning, polyrhythmic blend of spiritual jazz, full of sporadic drum fills, meditative chants, and dark piano chords. “I just wanted the band to have complete freedom to move in and out of things—almost like a standard jazz song, where you play the head-in solos or you head out. I still wanted to make it about the tradition,” he says.

A mix of jazz, vocal and instrumental hip-hop, and neo-soul, Black Space Tapes crams a host of genres into a single, 38-minute set without ever losing focus. Occasionally, those sounds arise within the frame of one song: “Emi” begins with Dean rapping, then glides into a brief breakdown of saxophone, acoustic drums, and piano, setting up an outro of Cali-centric electronica. Dean says the idea is to show how all forms of life and music originated in Africa. On a more personal level, it highlights the music that shaped his upbringing—from his time as a child playing piano in Bakersfield, California, to a young man now studying jazz at The New School in Manhattan. Dean was given his first keyboard as a Christmas present when he was eight years old. Dean’s parents were giving him early encouragement to be a great musician—like his grandfather, Donald, a noted jazz drummer best known for his work with pianist Les McCann in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. He’d practice piano three hours a day during the school year, and six or more per day in the summer months, while all of his friends were outside enjoying the warm weather. “My dad used to be like, ‘Well, while they’re out there doing that, you’re here working on this, and it’s probably gonna pay off for you in the long run,’” Dean recalls. “He’s like, ‘There’s gonna be tons of times for you to have fun with your friends,’ which in a way made me cherish it more. It wasn’t something that happened so regularly.”

Dean has always been an old soul who idolized his grandfather and admired the camaraderie he shared with his band. “I would spend time with them at gigs and stuff,” he says. “That’s what made me want to play jazz. Because watching him interact with his buddies—that was something I could see for myself.” Dean moved to L.A. from Bakersfield when he was 14 and attended an arts high school, where he met peers who liked the same kind of music. He soon started making jazz-inflected beats in his spare time. From there, he formed a band called Jamael Dean & the Afronauts, and started performing around the city. A year later, Dean caught the attention of jazz superstar Kamasi Washington, and appeared on the song “Tiffakonkae,” from 2018’s Heaven and Earth. Then he went on the road with bassist Thundercat as part of his trio.

Composer Miguel Atwood-Ferguson first played with Dean six years ago as a member of Nedra Wheeler’s band. Soon after, Ferguson started calling the pianist to work on music and perform with him on the road, and the two formed a creative connection. “I took him to South Africa last year and we played at the Cape Town International Jazz Festival, and that was such a huge honor,” Ferguson recalls. The city was in the midst of a severe drought: “We started to play the concert, and then it started to rain. And as our set intensified, the rain intensified. When we finished our set, it stopped raining and they started calling me (in Afrikaans) The Bringer of Rain—they said, ‘Don’t stop playing.’” That was Dean’s first trip to the continent. He remembers being nervous about going there because, as an American, he didn’t know how he’d be accepted. But once he got to Cape Town, he says it felt like home. Perhaps on purpose, Dean’s music has become metaphysical—like he’s fully tapped into his heritage. “He’s really evolved a lot more,” says Ferguson, who appears on Black Space Tapes. “He kind of goes to another zone. He’s aware of what’s going on around him harmonically, but he’s completely going spiritual with it, and he’s leaving traditional harmony and going to this place where it’s almost like he’s dialoguing with some other spirit.”

Carlos Niño gave Jamael’s band their first residency at his club, The Del Monte Speakeasy in Venice, Ca., in 2016. Niño, a celebrated bandleader and producer in his own right, became an immediate fan the minute he heard Dean play. “He’s a piano prodigy,” Niño says. “He can not only play, but he’s also an incredible composer. When I think about Jamael, I think about the lineage of musicians I love, and how early in their lives they started really going for it. And he’s just one of them. He’s completely in it.” Niño co-produced, compiled, and sequenced Black Space Tapes, which he says is just a small sampling of Dean’s vast artistry. “He could’ve easily come out the gate with a triple album of music. This almost reads like a short LP, but it’s really an introduction. This is a variety of what this guy does.” If nothing else, Dean hopes the album nudges listeners to absorb Yoruba culture. “Just to research it and find out what it means for themselves,” he says. “That’s what I hope will happen with the music, too. I want them to hear how it applies to their life. Maybe it’s through a feeling they get when someone plays a certain way, but I want them to remember that and figure out why.”

https://www.15questions.net/interview/jamael-dean-about-improvisation/page-1/

Name: Jamael Dean

Occupation: Pianist, producer, improviser, composer

Nationality: American

Current release: Jamael Dean's Primordial Waters is out via Stones Throw. He is also currently touring Europe:

11 Nov 21 Berlin – Badehaus

12 Nov 21 Utrecht – Le Guess Who?

14 Nov 21 Paris – Bambin

If you enjoyed this interview with Jamael Dean, visit his personal profile on the homepage of his label, Stones Throw. He is also on Instagram, and twitter.

https://jamaeldean.bandcamp.com/album/primordial-waters?from=embed

Tell

me about your instrument and/or tools, please. How would you describe

the relationship with it? What are its most important qualities and how

do they influence the musical results and your own performance?

The

tools I use are the piano, keyboards, Ableton, a pen, and paper. I use

them every day and the relationship I’ve come to have with them is one

of stability and reliance. They’re always there for me.

The most

important quality of the piano for me is the ability to hold many voices

at once in a harmonious way. It allows me to make combinations of

different sounds and energies that create different thoughts, feelings,

and patterns for me to experiment with. Each note has a different energy

so when used together it creates layers for me to paint with, not

forgetting to mention the rhythms it allows me to interact with using

both hands. It feels like I have multiple instruments in one and I love

it.

Keyboards are amazing for the different textures the

electronic sounds provide. It takes the energies of the piano and

provides another context for their usage. Ableton is amazing because I

can really dive into frequency in a methodical way allowing me to take

the mathematics of music and apply them to mixing and grooves in a whole

other way. It also allows me to record many ideas and hear them all at

once while allowing me to do a live arrangement in its clip mode.

Arrangement view is amazing too when I’d like to slow down the composing

process and go deeper into my intent.

The pen and paper allow

me to tap into my imagination and actually see them whether it’s symbols

or literal words. It’s all important to the creation process.

What do improvisation and composition mean to you and what, to you, are their respective merits?

Improvisation

is the key to life. It allows you to express freely and be in the

moment at the same time. It allows me to be present with the external

world while being in tune with what’s happening internally.

I’ve

been taught by many teachers that composition is improvisation slowed

down. It’s a very similar process where you never truly know where the

ideas come from, but you can decipher them with presence, persistence,

and the help of inspiration. The inspiration can be anything really.

Derek

Bailey defined improvising as the search for material which is

endlessly transformable. Regardless of whether or not you agree with his

perspective, what kind of materials have turned to be particularly

transformable and stimulating for you?

Life, the planet,

and the elements are the most transformative materials that stimulate

me. Every day is different with new ideas, feelings, and desires which

make writing a way for me to work through those things in a way that

truly brings joy.

Purportedly, John Stevens of the

Spontaneous Music Ensemble had two basic rules to playing in his

ensemble: (1) If you can't hear another musician, you're playing too

loud, and (2) if the music you're producing doesn't regularly relate to

what you're hearing others create, why be in the group. What's your

perspective on this statement and how, more generally, does playing in a

group compare to a solo situation?

I totally relate to

number 1, but number 2 is not something I can agree with as easily

because in life there are times you can’t always relate to what’s

happening around you.

However, the ability to discuss and come

together creates a common ground and foundation for understanding and

bettering ourselves and our character while increasing our wisdom. That

leads to making possible the impossible, and creating things never

imagined. It’s the same musically.

There are many

descriptions of the ideal state of mind for being creative. What is it

like for you? What supports this ideal state of mind for your

improvisations and what are distractions? Are there strategies to enter

into this state more easily?

Every emotion and mental

state I’m in leads to creation. We’re constantly creating the flow of

our lives as we experience it and make decisions every second of every

day. Music is a way to process those things.

Not saying it’s always easy as somethings are difficult to process, but the more you do it the easier it becomes.

The best strategy for that creative state is to live your life, be healthy, and be honest and truthful.

There

are no distractions just new developments in the creation of our lives

and music. The best support can be managing your own space and finding

ways to take care of yourself.

Can you talk about how your decision process works in a live setting?

Making

decisions in a live setting works the same as having a conversation.

You don’t want to cut anyone speaking off, but sometimes it happens and

you have to find a way to live in integrity with your desires while

honoring those around you.

It never hurts to listen and doesn’t cost anything to pay attention. Respect is important.

How

do you see the relationship between sound, space and performance and

what are some of your strategies and approaches of working with them?

Everything

in the space of our existence is a literal frequency from the light we

see to the materials that make up our physical body. Just as your body

can only hold so much food, the music can only take so much input before

it explodes, implodes, or transforms into something completely

different and it isn’t to be criticized.

Performance becomes the

ability to make decisions based on that and manage how you contribute

to the feeding of the music. The best strategy I have for that is

listening and being in the moment because sometimes our best plans don’t

go according to how we think it should go. So the best strategy is

adaptability and patience.

How is playing live in front

of an audience and in the studio connected? What do you achieve and draw

from each experience personally?

Playing live with an

audience and in a studio is only different based on your knowledge of

the people listening and being aware of their energy. In the studio

sometimes we as artists feel less pressure because we can edit things

and feel safer with making “mistakes”.

However, at the same

time, it can be a lot of pressure to make something that we hope is

received well by a greater mass of people. We feel that same thing when

performing live, but take solace in the fleeting nature of a moment.

I

find great value in the fast nature of a live performance and have

great love for being able to slow things down. The greatest experience

comes from the balance both provide. It allows me to approach the other

differently and creates new perspectives I may have missed in one at

some time, giving new routes to take on the journey of creation.

Can

you talk about a breakthrough work, event or performance in your

career? Why does it feel special to you? When, why and how did you start

working on it, what were some of the motivations and ideas behind it?

One

breakthrough I had was going to perform in Cape Town South Africa with

Miguel Atwood-Ferguson with Suite for Ma Dukes. It was very special

because of my love for Miguel’s arrangements and imagination, J Dilla’s

music, lush bigger groups of musicians, Africa, and nature.

At

the time Cape Town was experiencing a major drought and we when we were

playing the music in the outside concert it began to rain. It gave me

great appreciation for the frequency of nature and the ability to not

only invoke thought, emotion, and actions but also influence nature

itself. I then began focusing on the frequencies naturally occurring in

this dimension. Through Miguel’s benevolence he was able to touch

nature’s heart and restore balance even if briefly to that environment.

In

a way, improvisations remind us of the transitory nature of life. What,

do you feel, can music express about life and death which words alone

may not?

I was in my penultimate year of college and it

completely shifted my thinking of music as it was something I actually

experienced and not just a theory. I understood how violent music could

make people violent, but it was amazing to see beautiful music create

beauty on the physical planet.

Music can express the motion of

planets, the wind blowing, the earth changing, the destructive nature of

fire, the healing aspects of water, and our own thoughts and feelings

more than we can even rationalize at any one given moment. Everything

here as we know it works in a rhythm, and harmony, all for the sake of

balance. Sometimes we are not aware of the things that need to be worked

out, but if you ever left for a concert feeling overwhelmed, and came

back feeling refreshed, inspired, and having new ideas without having

any conversations being had, you know what I mean.

http://www.royalstateofmind.com/2020/06/jamael-dean-on-black-music-art-education-spirituality/

Jamael Dean:

On Black Music, Art Education, & Spirituality

Today for Royal State of Mind, I’m presenting a conversation with Jamael Dean — a jazz pianist, composer, hip-hop producer, and rapper out LA. Jamael is the leader of “Jamael Dean and the Afronauts,” plays with the Pan-Afrikan People’s Arkestra, has toured and played alongside Miguel Atwood-Ferguson, Thundercat, and Kamasi Washington. Dean can also be heard on Washington’s 2019 album “Heaven and Earth.” Playing music since he was young, Dean is now in school at the New School.

Dean’s affinity for cosmology and astrology is evident all throughout his music, from his album art to song titles. Perhaps due to this, listening to Dean’s music often makes me feel like I’m in outer space, floating by myself but being pulled — maybe lured — by the music: a swirling stream of sound and rhythm that ebbs and flows and beats and cracks and relaxes; a lulling sonic journey led decisively by Dean’s graceful keys. And yet, although Dean’s piano provides constancy, his music is effortlessly expansive, intertwining expressions of spiritual and free jazz with vocal-enhanced ambience and beats reminiscent of Ras G’s Ghetto Sci-Fi. The limitlessness of Dean’s musical orbit can be heard on two of his more prominent releases: “Black Space Tapes,” Dean’s tight, 38-minute debut album from 2019; and “Oblivion,” a 30-minute project Dean recently released this past April.

Jamael and I spoke on April 26, 2020, and we touched on a wide range of topics: Dean’s musical origins and influences; the role of art education in Black community and life throughout history; how his spiritual practices inform his life, compositions, and creations; the relationship between music and unknown ancestry; Dean’s recent release, “Oblivion”; and more. To listen and buy Jamael’s music, visit his Bandcamp page here.

ART by AMIRI MIKEL

Introducing: Jamael Dean

Jamael Dean has signed to Stones Throw. Here’s a couple tracks: “Eledumare” and “People Tell Olo.” Look out for an album later this year.

Pianist, producer, jazz prodigy, and just 20 years old, Jamael Dean

has already collaborated and performed with the likes of Kamasi

Washington, Thundercat, Miguel Atwood-Ferguson and Carlos Niño. His

music reflects the dual influence of his Los Angeles contemporaries and

jazz ancestors – Sun Ra, Alice Coltrane, Herbie Hancock and soul jazz

drummer Donald Dean, who is also his his grandfather. The Los Angeles

scene, he says, is “the only place I can go in the same day to a jam

session with music from the 20s and 30s to another session with music in

the 40s through the 80s, and after that play music with my friends from

that era onwards.”