AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING, 2022

VOLUME ELEVEN NUMBER TWO

ROSCOE MITCHELL

MORGAN GUERIN

(March 18-24)

KENNY KIRKLAND

(March 26-APRIL 1)

STACEY DILLARD

(April 2-8)

CHARENÉE WADE

(April 9-15)

JAMAEL DEAN

(April 16-22)

BRUCE HARRIS

April 23-29)

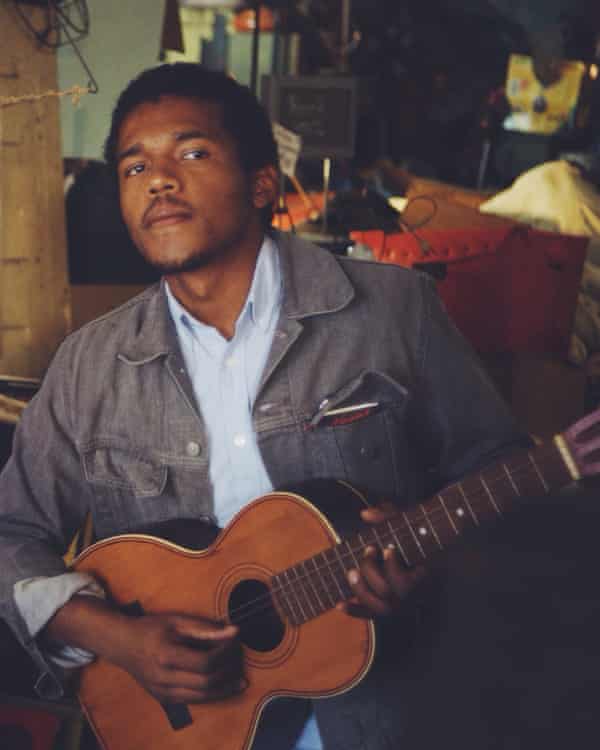

BENJAMIN BOOKER

(April 30-May 7)

UNA MAE CARLISLE

(May 8-14)

JUSTIN BROWN

(May 15-21)

TYLER MITCHELL

(May 22-28)

JONTAVIOUS WILLIS

(May 29-June 4)

CHRIS BECK

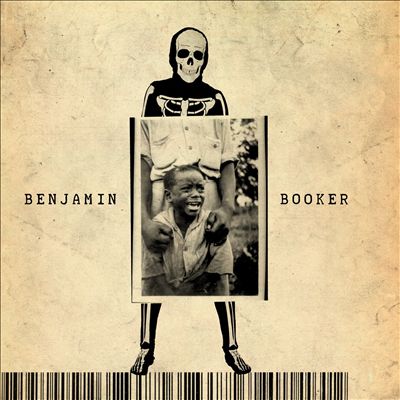

Benjamin Booker

(b. June 14, 1989)

Artist Biography by Stephen Thomas Erlewine

Part of a new breed of bluesmen, New Orleans-based guitarist Benjamin Booker draws equally from postwar electric blues and trashy garage punk. This much was evident from his eponymous debut, released on ATO Records in August of 2014. He recorded the effort with producer Andrija Tokic, who helmed the debut by kindred spirits and labelmates Alabama Shakes. He followed its release with touring in 2014, which included a Lead Belly jam session with Jack White that seemed a bit like a passing of the torch.

Such success suggested Booker was an overnight sensation, and it is true the Tampa Bay native had a sudden rise to success. After spending some time in Gainesville and New Orleans, he returned to his home in Florida and had been playing in a duo with drummer Max Norton -- the two were billed as Booker & Norton -- for just over a year prior to signing to ATO Records. Subsequently, Booker went out as a solo artist while retaining Norton as his main collaborator, with Tokic helping to fill out the sound in the studio. The self-titled Benjamin Booker came out a few months after its recording, appearing in August of 2014 and garnering its fair share of critical acclaim.

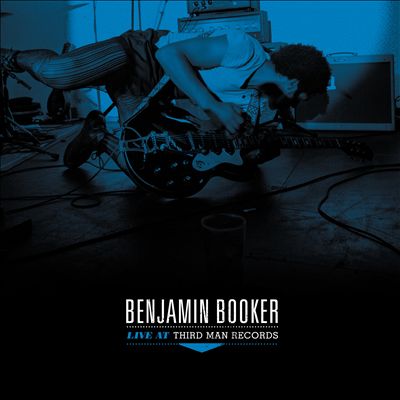

Early the following year, Jack White's label both hosted and released Booker's concert album Live at Third Man Records. In early 2016, looking for a new perspective to fuel his songwriting, Booker spent some time living in Mexico City. It was there he wrote much of the material for his ATO follow-up, beginning with "Witness," a collaboration with Mavis Staples that was Booker's response to racist acts of violence. The album, also called Witness, was released in the summer of 2017.

Mixdown Magazine - December 2014 - #248

Benjamin Booker’s music has some strong roots. He’s based in New Orleans, a city with a tremendous music history stretching from early jazz through to rock’n’roll, funk and hip-hop. His voice recalls the hardened defiance of the early bluesmen. Similarly, his guitar work re-states classic blues riffs and soul-indebted chord changes with more than a touch of rock’n’roll firepower.

Perhaps more significantly, Booker’s debut self- titled album

(released this August) is catapulted by a bounty of energy and curiosity

– undeniable facets of youth. As a result, at first glance Benjamin

Booker could be seen as a collection of fairly rudimentary tunes, but a

closer looks reveals Booker’s unkempt rock’n’roll to be thrilling all

over.

To record the album, Booker plunged in headfirst, sparing any pretension in favour of honest excitement. “There’s a tonne of first takes on the record and I’m fine with that,” he says. “The majority of all the songs were recorded live in the studio. I had six days to record and two days to mix it.

“I recorded it analogue for that reason,” he continues, “because you

can’t really mess around as much as when you record digital. I had been

in the studio before and recorded digitally and it’s kind of

overwhelming – just the possibilities. Like, every word, you miss one

note, you can go back and fix things one note at a time. Stuff like that

would’ve just driven me crazy. But recording analogue and just having

to play the songs [and then] that’s it, it took a lot of the pressure

off.”

Booker is still fairly new to this music caper. Not long after his earliest public performances he got swept into a position of focus – earning a deal with ATO Records and promptly entering the studio to record Benjamin Booker.

“I played my first show in May 2012, I think,” he says. “Then I really didn’t start playing [lots of] live shows until last summer. It was very new. I felt pretty comfortable going in [to the studio], but now when I look back on it, I think we’ve improved so much more since then.”

A lot of this improvement stems from the fact that – backed by drummer Max Norton and bass player Alex Spoto – Booker’s spent the majority of 2014 on tour. Touring alongside the likes of Jack White and Courtney Barnett, it’s been a massive learning curve for the young New Orleans native.

“We’ve basically been on the road since February playing shows,” he says, “so it feels like a tight show. We know how it goes down – what everybody’s doing. I’ve definitely gotten more comfortable doing the whole performing thing and hopefully better at playing guitar.

“Every song is a little bit different [live] than it was when it was

recorded,” he adds. “It just comes with touring and being on the road

every day – you get more experience and you get better at what you do. I

think the show overall is way better than it was at the beginning of

the year. I wasn’t a natural performer; it was really tough at the

beginning to get up on stage and play in front of people. It’s

definitely gotten easier. I enjoy it more now than I used to.”

With any artist, as their abilities develop and creative outlook evolves, attempting to re-apply the naivety effective in their career’s nascent period would be a complete sham – artificial scrappiness doesn’t come over so well. When it comes time for Booker’s sophomore release, he’ll inevitably be influenced by the truckload of experience he’s gathered this year, but he’s not looking to overhaul his approach.

“Hopefully the next record I’ll reach farther with the singing and farther with the guitar playing,” he says. “The record probably won’t be similar at all, but the process, I think, will be similar. I don’t think I’ll ever spend more than a couple of weeks

in a studio and it will probably be analogue and probably mostly recorded live again. That works for me, so I think I’ll try it again next time.”

Booker’s whirlwind 12 months continues into the new year, when he’ll head our way for the Laneway Festival tour. This is but one in an ever- expanding list of incidents from the last year that make him somewhat incredulous.

“Everything that’s happened this year is like, way more than I expected to happen,” he says. “I would’ve been happy just playing my record out. If nobody really bought it I would still have my own record on vinyl. That would’ve been awesome for me.”

Benjamin Booker Talks Southern Racism, ‘Anti-YOLO’ Outlook, New LP

“It’s important for me to do something more with music than just entertain people,” singer says, reflecting on second album ‘Witness

In mid-2014, not long after signing with ATO Records, recording what would be his breakout first LP and making his television debut on Letterman, Benjamin Booker found himself in a bad way. “I was smiling in front of people but I was not handling it well,” says the blues-and-punk-influenced rocker, who following the release of the acclaimed Benjamin Booker found himself playing major festivals, writing and recording with Mavis Staples, and touring with Jack White and Courtney Barnett. “I was just pulling my hair out the whole time,” he told Rolling Stone on a recent afternoon. “It’s not a natural thing to have happen.”

So, early last year, on a whim, Booker headed to Mexico City for several weeks; he says the getaway not only cleared his head but more importantly jumpstarted the process of writing Witness, his gritty, genre-bending second album. Booker says the at-times haunting and bleak full-length – influenced by everything from hip-hop to Sly and the Family Stone and Seventies- Nigerian funk – was a direct reaction to him coming to terms with racism he felt growing up in the South. A harrowing experience in his then-home of New Orleans also played a part. In December 2015, the musician was randomly shot at while riding his bike in the Bywater neighborhood. “I had to turn around and bolt out of there and these guys were chasing me,” Booker recalls. “I’ve had a few life-or-death experiences but this felt particularly important. To be aware that at any time you can die forces you to live your life differently.”

Booker, 27, says his roller-coaster past few years have given him a clearer perspective on both music and life. “I’m wiling to take more risks,” he says in a conversation that touches on his newfound anti-YOLO lifestyle, the state of the country and why making music has become about more than just penning a good tune. Says Booker: “I’m so happy this time. I’ve been able to stabilize myself and can appreciate what’s happening.”

Coming off such a widely praised debut, did you feel pressure going into this new LP?

You

just hope that you’re getting better. But I took the pressure off by

just saying, “OK, well, I’m not going to do the first one again.” Once I

decided I wasn’t going to do the same thing it took a lot of pressure

off. It felt like I was starting a new thing.

I think the sounds we got on this album were closer to the things I had envisioned the music sounding like all along. That was a lot thanks to the producer [Sam Cohen] I was working with. But also I feel farther along as a songwriter and musician. I feel more ready to present this than I was with the last record.

I imagine you were in a different place working on this than when you wrote your first album?

I’m

very grateful I got to do the first record. But yeah, it was a very

different time. I was still working for minimum wage when I was doing

that record and didn’t know if it was going to be put out. I’m happy

that I was able to do it, but I think with the second one for me it’s

been more like, “This is something you’re pretty good at and you should

do your best and make the best record you can.” It’s just a different

feeling. Because I’m not just making it for friends or just writing

songs for myself. Other people are going to see it now. I don’t see it

as being a bad thing, really.

You have to trust yourself. The thing I learned from the first album is I could make a record that is completely personal and do it on my own and not expect people to see it. So when I was doing this record I just had to remember that it’s OK to set everybody aside for a little bit and work on the songs myself and see where they are and trust that the people who enjoyed the first album would enjoy this one even if it’s a little different.

When did your mind start moving toward what became Witness?

Probably

about halfway through the first album cycle which was a couple years. I

started thinking about new stuff. I was constantly recording things on

my phone and writing lyrics. But because the music I make is so personal

and closely linked with where I am at a certain point in my life I

think I had a hard time. I hadn’t moved up. I needed to make changes to

get to the next level of songwriting. I knew I didn’t want to do the

same thing. I was at a block, I guess. I still felt like I was stuck in

the first record because I was still playing those songs every night.

You kind of feel trapped there and I couldn’t progress. But after I got

done with touring and everything was able to take a break I took a trip

to Mexico and was by myself for a while. I was able to work on guitar

playing and work on songwriting and work on lyrics and start piecing

things together. That’s really when it started to come together.

It sounds like you really stepped back and looked at yourself and the way you were raised.

What

you’re talking about, stepping back and looking at yourself and finding

your place in the world, that’s what the whole album is about. It was

important to me to share that experience I was going through with other

people and start the conversation of “Where are you guys at right now?”

That was a big part of the trip. It was a life-changing experience. I

think there’s been a lot of points in my life where I’ve had to stop and

take a break and think about things before I could move forward. This

was one of those times.

You’ve mentioned how the Mexico City trip allowed you to let go of

the belief that you could “outsmart” the racism that surrounded you

growing up in the South.

There is repression that goes on. You

don’t want to live in fear so you push it off to the side and do

whatever you can to get rid of that feeling and focus on other things in

your life. If I was in a different position and worried about my life

on a constant basis or getting in trouble in different ways than I don’t

think I’d be able to play music. I think a big part of it was being

able to push those things to the side and keep trudging forward. That’s

the only way that I was able to do it. Eventually that stuff catches up

with you.

When you’re a college student, it’s easy to think, “I have a plan. I

know what I’m doing and I can forget about those things.” But you can’t.

Benjamin Booker - Witness (Live at Columbus Theatre)

Filmed at the Columbus Theatre in Providence, RI. Special thanks to Tom Weyman.

Drums: David Christian

Bass: Brian Betancourt

Piano/Keyboard/Violin: Oliver Hill

Backing Vocals: Alicia Chakour

Backing Vocals: Saundra Williams

Backing Vocals: Mark Rivers

Viola: Valentina Shohdy

Cello: Samuel Quiggins

Guitars: Sam Cohen

How did the song “Witness,” which features Mavis Staples, come together?

This

album is more thematically tied together than the last one. So

everything is fitting together to put together that journey to Mexico

City and that experience. One of the first songs I wrote was “Right on

You” and that was important for me. Because I was getting off tour,

going back to New Orleans. It’s a city with a lot of distractions and a

lot of trouble you can get into. I was living a very selfish life and

not taking care of myself. The album and that song in particular are

about how it’s important for people to live with death constantly. To be

aware that at any time you can die because it forces you to live your

life differently.

My friends recently told me that I’m a bigger risk taker than a lot of people. But I think it’s because I’m constantly thinking about dying. I don’t know, just the fact that none of this really matters … I’m wiling to take more risks. What I was trying to say with that song is that there was this whole YOLO thing a couple years ago. Like, you only live once so you should party because you could die at any moment. I was doing this the other way: You could die at any moment so don’t be selfish and contribute something to the world. Leave the hedonistic lifestyle and actually do something. It’s an anti-YOLO song.

Why did you decide to leave New Orleans? Your near-death experience there must have played a role.

Yeah,

one of the big reasons I left was because I didn’t feel safe there

anymore. A similar thing had happened to my friend Tony a few months

before. He ditched his bike and hid under a car. New Orleans has a

bullshit education system. A lot of the stuff you hear happening only

seems like it could come from people with nowhere to go and no way out.

We live in a fuckedup country. I want to talk about it more but it’s hard

to talk about, you know.

The first week I started AmeriCorps another AmeriCorps member was shot in the head. 18 years old. That same week someone shot up a six-year-old’s birthday party. There was a shooting in Bunny Friend Park a mile away from my house where 17 people were shot. It’s heartbreaking. People go there to party and completely miss what is happening. The police there are notorious for being a joke. I used to sit in police meetings in Central City, the roughest neighborhood there. They tell kids they have more of a chance dying there than in Iraq. There’s a wealthier neighborhood across the street. The difference in life expectancy for one side of St. Charles to the other is 22 years, I think. Meanwhile I’m sitting in a police meeting watching them text each other jokes.

“We live in a fuckedup country.”

How was working with Mavis? You’d previously written “Take Us Back” for her album Livin’ on a High Note.

Honestly,

I think she connects with everybody. I’m happy that we got along pretty

immediately. We had a phone call the first time but she’s one of those

people that feels like you’ve known them for a long time. She’s almost

like a grandmother. She just has such a positive vibe and outlook on

life that it’s hard to ignore. Honestly that had a big influence on the

album also. When I was writing the song for her last album it was the

first time I wrote a song that wasn’t really a sad song. We talked about

where she was at in her life and career and she was stressing the

importance to me of family and taking the time to appreciate your life

and the people around you. It ended up being a really important

experience for me – realizing that I was able to write about different

things than I thought I was able to.

How do you look back now on your initial breakout fame?

I got signed in October 2013, recorded an album in December and we played Letterman

the next April. It was too much. I’m so happy this time to get out

there because I feel like I have been able to stabilize myself and can

appreciate what’s happening with every show and that people are coming

out. But at that time I was more focused on every day and every week and

how there was something crazy that was happening that was causing me an

insane amount of anxiety.

Now you seem far more engaged with your craft.

Definitely. I

think I had to decide the person I wanted to be and the kind of

musician I wanted to be. I just thought about getting to the end of my

life and thinking about what I was doing with music. If I was just an

entertainer, am I going to be happy? I don’t think I would be. It’s

important for me to do something more with music than just entertain

people.

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2017/jun/21/benjamin-booker-interview-witness-willow-black-america

Benjamin Booker:

How I turned my personal meltdown into a rallying cry for black America

He was overweight, abusing drugs and fleeing from his self-harming past. So he took all his problems – and turned them into the sensational new album Witness

Five years ago, Benjamin Booker had a vision. He was living in New Orleans, just scraping by, when he saw himself on stage, playing a raucous hybrid of blues, punk and soul. He set out to make it a reality. Within a couple of years, he was touring an acclaimed self-titled debut album, supporting Jack White and Courtney Barnett, and playing late-night TV talkshows. It all felt surprisingly easy. It was only when he returned to New Orleans that he realised he was lost.

“It’s

the cliche,” he says with a nervous laugh. “You think that when your

dreams come true, it’s going to get better – and of course it doesn’t.

Everybody knows it, but I guess everybody thinks it will be different

for them. It only got worse.” Booker is sitting in the office of Rough

Trade founder Geoff Travis, surrounded by framed photographs of

legendary musicians. He looks like he belongs on the wall: he’s a

dashing, charismatic 27-year-old with a smile that unfurls like a

banner, but there’s a rawness and urgency about him that keeps you on

your toes. He gets straight to the point.

“Because the songs are so personal,” he says, “if I wanted to make an album that progressed, I needed to progress my personal life. I was feeling overwhelmed. I was not taking care of myself, abusing some substances. It was the worst shape I’ve ever been in. I didn’t recognise myself. I was 15 pounds heavier and looked like shit. When you’re out on tour, it’s easy to not worry about things. Then you come home and realise your life is in pieces.”

Booker needed to get away and clear his head, so

he packed his bags and went to visit friends in Mexico City. On the

flight, he read Don DeLillo’s White Noise

and was struck by this line: “What we are reluctant to touch often

seems the very fabric of our salvation.” He made a bullet-pointed list

of problems he needed to confront: 10 points that became the 10 songs on

his new album Witness,

a sensational record that is more spacious, open and emotionally direct

than his debut. As soon as he returned home, he moved to Los Angeles.

“I have a habit of running away from things,” he says.

Mostly, he is running away from his childhood. Born in Virginia, Booker was raised in a trailer park in Florida according to the strict tenets of evangelical Christianity. “When I was a kid, I thought this is so terrible that one day there’s gotta be some good stuff,” he says. “I used to be a cutter. I was a pretty depressed kid.”

It

was the constant guilt that hobbled him. “I didn’t lose my virginity

until I was 20. I was so uncomfortable around women. I would drink so

much to just be able to talk to them that I would ruin every

opportunity. That overwhelming guilt comes from being told that you’re

going to go to hell and burn forever for the things that you do. The

things you learn as a kid never leave you.” His voice falls. “I don’t

think it will ever go away.”

The

gospel influences on Witness reflect the straitened soundtrack to

Booker’s childhood. Until he was 16, he’d never even heard of the

Beatles. When he first heard Nirvana, he was so stunned that such a

thing existed he listened to little else for the next two years. After

school, he went to college in Gainesville, Florida, where he interviewed

musicians and writers he admired for the college paper.

However, Booker couldn’t find a place in Gainesville’s thriving punk scene. “I didn’t feel like I could fit in, especially being a black guy. The punk scene is supposed to be inclusive, but it’s the opposite.” After college he moved to New Orleans to work for a non-profit company, HandsOn New Orleans. The gruelling experience wrought havoc on both his idealism (“It was hard learning that everything comes down to money”) and his health. “I literally ate bread and butter and drank beer for six months. It was a bad time.” He shrugs. “I don’t know. I got a record out of it, I guess.” His debut’s fierce and wrenching tales of unravelling lives stem from that period.

Booker doesn’t consider Witness a political record, but many listeners will. The knockout title song, which features gospel matriarch Mavis Staples, squarely addresses the killing of innocent African Americans by the police. “I have zero interest in politics,” he says. “I’m very interested in how people get through life and that’s what I write about.”

He mentions the killing of Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida, in 2012. Booker lived a 90-minute drive away. He was used to being pulled over by the police and viewed with suspicion, but had always felt that he’d be OK as long as he did the right thing. Martin’s death made him realise he’d been kidding himself.

“When it’s just a kid walking down the street, or a guy who serves lunch in schools, this is you,”

he says. “It really affected me. You realise it doesn’t matter if you

are in college and moving towards something. They don’t care. It was the

first time I came to terms with the idea that there are people who

don’t even see me as a person. I’m basically an animal. My life is

disposable. I’m glad I’ve come to that knowledge. It could have been

more dangerous if I still felt I could get away from it.”

The

title of Witness comes from an interview with James Baldwin, one of

Booker’s heroes, about being a witness rather than a spokesman, though

Booker worries that witnessing is not enough. “With police shootings,

there’s camera footage on TV. Everybody knows what’s happening. It’s not

enough to just see it, there has to be action.”

The album comes, he says, from a sense of obligation. “It’s important to do more than just entertain people. I guess my biggest fear is looking back on my life and feeling like it was all a waste.” It’s really about learning to be a better person. “People are the sum of their actions and I was a piece of shit,” he says flatly. “It’s not enough to have good intentions, you have to make good decisions – all the time.”

What rescued him from his cycle of self-destruction was love. For the past 18 months, he’s been in the first serious relationship of his life and that has made all the difference. Has he finally stopped running away? “Ah,” he sighs, “let’s hope so, but who knows? Things change. I have no idea what’s going to happen.” He wipes away a tear. “Sorry, I’m getting all emotional.”

Booker is devoted to honesty even though it’s clearly difficult – or perhaps because it is difficult. He’s like that with his music, too. “There’s a fear of putting your stuff out there,” he says, “but my fear of being a shitty artist is more intense.”

Benjamin Booker plays Moth Club, London, 4 July. Witness is out now on Rough Trade.Early life

Benjamin Booker was born in Virginia Beach, Virginia. His family relocated to Tampa, Florida, where he attended all-ages DIY punk shows as a teenager.[5] He attended Orange Grove Middle School, a magnet school for the performing arts, followed by Hillsborough High School, where he studied in the International Baccalaureate Program. He then attended the University of Florida in Gainesville, studying journalism with intentions of going into music journalism.[5] After college, he moved to New Orleans to work for a non-profit organization and began playing shows.[5][6] He self-released the four-track EP Waiting Ones in 2012, a collection of "low-fi blues-influenced folk-punk recordings and handclap percussion" that gained the attention of music blog Aquarium Drunkard.[6][7] The track "Have You Seen My Son" eventually landed on Sirius XM satellite radio. In 2013, he began touring as an electric duo and signed with ATO Records to produce his debut album.[6]

Career

2013–present: Benjamin Booker

Booker's self-titled debut album was recorded in December 2013 at The Bomb Shelter, an analog studio in Nashville. Produced by Andrija Tokic (Alabama Shakes, Hurray for the Riff Raff), the album was released on August 19, 2014 via ATO Records in the United States and Rough Trade Records in Europe.[8] The first single from the album, "Violent Shiver," was released in April 2014.[9] The album received early praise, debuting in the top 10 of Billboard's Alternative Albums and Independent Albums charts[10] and leading to Benjamin Booker being named an "artist you need to know" by Rolling Stone,[11] "the best of what's next" by Paste[12] and a "contender for rock record of the year" by Spin.[13] Benjamin Booker also performed on late night television programs Late Night with David Letterman,[14] Conan[15] and Later With Jools Holland.[16]

Since release, in addition to touring with Jack White and Courtney Barnett,[17] Booker, accompanied by drummer Max Norton and bassist Alex Spoto,[18][19] has played international headlining tours and performed at a number of festivals. In 2013, he performed at FYF Fest, the Newport Folk Festival, the Austin City Limits Music Festival,[20] Voodoo Experience[21] and Lollapalooza, where Rolling Stone named his performance the festival's "best rock star moment... best experienced live and turned up to 11".[22] Internationally, he has appeared on the lineups of France's Festival Les InRocks Philips and Australia's St Jerome's Laneway Festival.[23][24]

2017: Witness

Booker's second album Witness was released on June 2, 2017. The album was announced with the premiere of its title track "Witness" (featuring Mavis Staples) alongside an essay written by Booker which detailed the experience that led him towards writing the album's title track.[25] The song "Witness" was called "a piano-pounding hymn for Black Lives Matter" by The New York Times.[26] The title track's references to police brutality and activism garnered Booker coverage in politically-leaning outlets including Mic, which noted the album's "urgent synthesis of blues, gospel and soul — forms with long histories of translating black pain into uplifting and enduring compositions … with a raw and unforgiving candor that's reminiscent of downtown New York punk."[27] The opening track "Right on You" was shared on April 19 by The Fader which called it "a staticky, high-tempo ballad that packs a punch".[28] The third song to be released from the album, "Believe", was premiered by Time magazine on May 23.[29] Since the album's release on June 2, 2017, WNYC has described Booker as "a punk & grit-infused songwriter whose ecstatic and soulful sounds channel vintage soul-rock, gospel, and blues."[30] On June 19, "Witness" was shared by Pitchfork alongside a review saying Benjamin "makes retro music feel modern, reflecting on racism in America while drawing on blues, soul, and gospel."[31]

Following the tours to support Witness, Booker was relatively quiet for the remainder of the decade. In September 2020, he released the single "Black Disco" with proceeds going to the Southern Poverty Law Center.[32]

Discography

Studio albums

- Benjamin Booker (2014)

- Witness (2017)

Live albums

- Live at Third Man Records (2015 – exclusively on vinyl)[33]

EPs

- Waiting Ones (2012)

- Spotify Sessions (2014 – Digital exclusive via Spotify)

Singles

- "Violent Shiver" (2014)

- "Witness" (2017)

- "Black Disco" (2020)

Interview: Benjamin Booker

Benjamin Booker: “I don’t write songs unless

it’s something meaningful to me”

We catch up with the soulful American rocker to learn how a trip to Mexico City inspired his new record

When Benjamin Booker burst onto the garage rock scene with a Violent Shiver in 2014, his arrival felt like a genuine shot in the arm for the genre. His self-titled debut album was rightly lauded as an explosive dose of amped-up blues from the Virginia Beach-born artist and announced him as a talent to be closely watched.

Subsequently, though, it turns out that Booker wasn’t happy with his life in New Orleans and in the press material for his new album he describes himself as being “a songwriter with no songs”. Witness, a genre-expanding evolution in sound, was born from his decision to flee the city and fly to Mexico City, a place where he could neither speak the language nor knew anyone, where solitude and freedom could help him rediscover his muse.

We had a chat with Booker during his recent visit to London to talk about the soul-searching road that led him back to songwriting…

Congratulations on the new album!

“I’m very excited about it. The last album was one of those records where I didn’t know that it was going to be seen by anyone. This time, because I knew that people would do, I tried to really put everything into it and I feel really proud of it.”

Can you remember the exact point when you began writing again?

“I was on the plane and I was reading White Noise by Don Delillo, an amazing book, and I came across a sentence ‘What we are reluctant to touch often seems the very fabric of our salvation.’ At that point I took out a piece of paper and I was like, ‘Okay Ben, for once in your life be honest with yourself about the person you are and your faults and problems and the things you really need to address,’ and I made a bullet-pointed list of all those things and wrote them down and that basically became the different tracks on the album.”

You then kept that list on you in Mexico and referred back to it?

“Correct, I just referred back to it for the different songs that I was writing. It’s really crazy because I always have problems and it just felt amazing on that plane – everything kind of fell into place a little bit.”

Where did you tend to write previously?

“I’m one of those people who can’t just sit down and write a song. I don’t write songs unless it’s something meaningful to me, so it’s hard to just pick a topic and sit down and write about it. It’s usually when there’s an overwhelming feeling that I have to get out, then I’ll pick up a guitar and write something. For the last album, a song like Violent Shiver was written in like five minutes, just like an immediate ‘this is what’s coming out right now’ kind of thing and that’s usually the way that I write songs. I don’t usually spend a lot of time pouring over songs. I wait for them to come in.”

What’s the next step in that process?

“Well, I think that you just have to sit with them for a while. The thing about Mexico, just being alone and isolated and not being able to speak Spanish, meant I basically spent a month in silence. The nice thing was that all of those things, the list and all of those things, I spent a lot of time walking around the city sitting in old cathedrals and museums and things like that. It was the first time in a long time that I had time to myself to think about where I was at that point and I think it was easier to write. Everything came together in a very short period because I had more time than ever to sit and be quiet.”

Were you recording songs at that point?

“I recorded a bunch of demos when I was there and then I found Sam [Cohen] from listening to the Kevin Morby record that I loved. I met with Sam about a month after recording and we had three days when I came in with the demos and we just edited the songs, which was really nice. I think it’s really important to spend a lot of time editing yourself and being honest about what is good and what is bad. We both had the intention of trying to make the best songs that we could. Some of the songs went from five or six minutes to two-and-a-half minutes, we just really cut stuff out and tried to save the best bits.

“Off The Ground is the one I’m thinking about, that song was six-and-a-half minutes long. We cut it down. A lot of them were like that. I also wanted ten songs on the album specifically, I just wanted to have time to focus on them and make sure that they were good. I didn’t want filler songs.”

Booker: “Even if I’m scared to do it I’d rather put myself out there than put out bad music.”

Yet the album includes a lot of different genres, like soul and gospel. Was that a deliberate decision?

“Yeah totally. I started listening to a bunch of different music over the last couple of years and I think I was more focused on the rhythm this time because I’d been listening to a lot of funk music from Nigeria and also the Sly & The Family Stone album called Fresh. I was listening to a bunch of hip hop also, so when we were recording the album anything that I came in with that was maybe more punk and like the last record we broke apart and I tried to get a groove going. It was a whole different mindset that was a little hard to adjust to but I was very happy with the end results.”

Do you think you can hear Mexico City in there at all?

“There was more Mexico City in the demos. If you heard the demos you’d definitely get a bit of that influence in there but it got a little filtered out during the process of editing the songs. We didn’t go into the studio with any plan of how we were going to record the songs, when I was working with Sam the focus was just on the chord progressions and the structure of the song and the lyrics and melodies. Just the bare bones of the songs and that’s the most important thing to me, that you can play the song with just one instrument and sing it, that’s when you know that it’s a good song. When we got to the studio we would just try the songs out in a bunch of different ways until we found something that we were happy with. But we didn’t go in with anything except what we thought were good songs.”

How long did it take to get them to the point that you were happy with them?

“Sometimes we did like twelve different ways. I had two weeks to record the album, we spent a week in Woodstock, New York and a week in Brooklyn, New York. I think the majority of the album was probably done in about four days, it was pretty quick. The rest of the time was spent editing it, taking things out and adding little parts and things like that.”

Does that editing process take away from the immediacy at all?

“I definitely enjoyed the first album but when I listen back to it now I wish that I had done more editing and so that was the focus this time, to have the best things on the album.”

It also covers issues like police brutality and racism, was that easy for you to write about?

“The fear of being a bad artist outweighed my fear of exposing myself. So even if I’m scared to do it I’d rather put myself out there than put out bad music.”

Does your writing style change at all depending on the subject matter?

“It’s a very different process to last time. Honestly, the point of my life was pretty rough writing the first album and I don’t even remember writing most of those songs. So this was a very different experience, I was very much present for all of the songwriting. It was a hazy few years of my life that I don’t really remember.

“I think that you really need to be completely focussed to be able to write. When people talk like ‘oh I need to drink or smoke to write’, I don’t think you can write good songs like that. For me at least, I need to be present.”

But going back to a song like Violent Shiver, that has a distinct energy to it. Can you capture that if you’re not in the moment?

“That riff was literally the first thing that I wrote when I picked up the guitar. The words were written and the song came together in five minutes, I can’t even explain to you. That’s why it takes me forever to write songs, I just wait for the song. I can’t sit down and write. I have tried to do it but they’re just all terrible, it just feels forced and doesn’t feel real.”

Benjamin Booker: “It’s important to me not just to be an entertainer.”

We’re guessing you have no desire to be a backroom songwriter then?

“Those people can’t be happy, it’s bullshit.”

If you’re writing a song about a specific incident that’s happened to you, does that memory then change once it’s become a song?

“I think that it’s just weird because you have to relive those moments over and over again. I guess it does change it but I don’t know how it changes. Those things will never leave me now because I’ve sung them. It’s like a time capsule that you’re always keeping with you.”

When you’re going through a bad experience is there ever a part of you that’s thinking ‘at least it’s giving me something to write about’?

“In the past yes totally, I’ve had some unbelievably terrible things happen to me where I should be losing it and there’s a little smirk. There are people who aren’t musical who if they’re angry with something they’ll write it down on a piece of paper and that’s enough to get it out. There’s something weirdly therapeutic about just seeing it or hearing it out loud so it’s not just stuck in your head.”

Is it important to you that listeners know the back story behind the album?

“Yeah totally, it’s very important to me. Really the reason why people write music, or why I write music I guess, is that you have faults and things that you’re going through, it is therapeutic. You’re telling people ‘hey these are the problems with me’ and just hoping they accept you. When you’re out there singing these songs to people and they’re clapping and showing you love, selfishly it just makes you feel better about your life.”

By writing about those flaws do you think you’ve become a better person?

“Oh yes, my life couldn’t be more different than it was during that time. A lot of things have changed. I’m living out in California now, I’m in the most serious relationship I’ve ever been in. Living a lot healthier lifestyle. I’m just in a happier place.”

A California place!

“It really is a nice place. I totally recommend it. Going from New Orleans to that couldn’t be more different.”

Does that then make you even prouder of the music, that it’s had a noticeable effect on you?

“It’s important to me not just to be an entertainer. If when I’m older I look back on the work that I’d done and all I did was entertain people like a song and dance man I wouldn’t be very happy. It’s important to me to make stuff that is meaningful to me and that will hopefully mean something to other people.”

What would you like the listener to take from the album?

“From this album, in particular, I hope people see that it can be very difficult to forgive yourself and to look at your own faults and address those problems but at the end I think that you come out better. This is an optimistic album overall, it can be dark but I think you come out on the other side a better person. I hope that people look at their lives and think about who they are. I had a hard time realising that you really are the sum of your actions, it’s not enough just to have good intentions. You have got to make good decisions all the time. Those are the kind of things that I want people to think about when they’re listening to the album.”

Interview: Duncan Haskell

Witness is out now. For details on the album and his upcoming tour check out benjaminbookermusic.com

http://benjaminbookermusic.com/witness.html

“Once you find yourself in another civilization you are forced to examine your own.”-- James Baldwin

By February of 2016, I realized I was a songwriter with no songs, unable to piece together any words that wouldn’t soon be plastered on the side of a paper airplane. I woke up one morning and called my manager, Aram Goldberg.

“Aram, I got a ticket south,” I said. “I’m going to Mexico for a month.”

“Do you speak Spanish,” he asked.

“No,” I answered. “That’s why I’m going.”

The next day I packed up my clothes, books and a cheap classical

guitar I picked up in Charleston. I headed to to Louis Armstrong

Airport and took a plane from New Orleans to Houston to Mexico City.

As I flew above the coast of Mexico, I looked out the plane window and saw a clear sky with the uninhabited coast of a foreign land below me.

I couldn’t help but smile.

My heart was racing.

I was running.

I rented an apartment on the border of Juarez and Doctores, two neighborhoods in the center of the city, near the Baleras metro station and prepared to be mostly alone. I spent days wandering the streets, reading in parks, going to museums and looking for food that wouldn’t make me violently ill again. A few times a week I’d meet up with friends in La Condesa to sip Mezcal at La Clandestina, catch a band playing at El Imperial or see a DJ at Pata Negra, a local hub.

I spent days in silence and eventually began to write again. I was almost entirely cut off from my home. Free from the news. Free from politics. Free from friends. What I felt was the temporary peace that can comes from looking away. It was a weightlessness, like being alone in a dark room. Occasionally, the lights would be turned on and I’d once again be aware of my own mass.

I’d get headlines sent to me from friends at home.

“More arrests at US Capitol as Democracy Spring meets Black Lives Matter”

“Bill Clinton Gets Into Heated Exchange with Black Lives Matter Protester”

That month, Americans reflected the murder of Freddie Gray by Baltimore police a year earlier.

I’d turn my phone off and focus on something else. I wasn’t in America.

One night, I went to Pata Negra for drinks with my friend Mauricio. Mau was born and raised in Mexico City and became my guide. He took me under his wing and his connections in the city made my passage through the night a lot easier.

We stood outside of Pata Negra for a cigarette and somehow ended

up in an argument with a few young, local men. It seemed to come out of

nowhere and before I knew it I was getting shoved to the ground by one

of the men.

Mau helped me get up and calmly talked the men down. I brushed the dirt off of my pants and we walked around the block.

“What happened?” I asked him.

“It’s fine,” he said. “Some people don’t like people who aren’t from here.”

He wouldn’t say it, but I knew what he meant.

It was at that moment that I realized what I was really running from.

Growing up in the south, I experience my fair share of racism but I managed to move past these things without letting them affect me too much. I knew I was a smart kid and that would get me out of a lot of problems.

In college, if I got pulled over for no reason driving I’d casually mention that I was a writer at the newspaper and be let go soon after by officers who probably didn’t want to see their name in print.

“Excuse me, just writing your name down for my records.”

I felt safe, like I could outsmart racism and come out on top.

It wasn’t until Trayvon Martin, a murder that took place about a hundred miles from where I went to college, and the subsequent increase in attention to black hate crimes over the next few years that I began to feel something else.

Fear. Real fear.

It was like every time I turned on the TV, there I was. DEAD ON THE NEWS.

I wouldn’t really acknowledge it, but it was breaking me and my lack of effort to do anything about it was eating me up inside. I fled to Mexico, and for a time it worked.

But, outside of Pata Negra, I began to feel heavy again and

realized that I might never again be able to feel that weightlessness. I

knew then that there was no escape and I would have to confront the

problem

This song, “Witness,” came out of this experience and the desire to do more than just watch.

If you grew up in the church you may have heard people talk

about “bearing witness to the truth.” In John 18:37 of the bible Pilate

asked Jesus if he is a king. Jesus replies, “You say that I am a king.

For this I have been born, and for this I have come into the world, that

I may bear witness to the truth. Everyone being of the truth hears My

voice."

In 1984, The New York Times printed an article titled

“Reflections of a Maverick” about a hero of mine, James Baldwin. Baldwin

has the following conversation with the writer, Julius Lester:

Witness is a word I've heard you use often to describe yourself. It is not a word I would apply to myself as a writer, and I don't know if any black writers with whom I am contemporary would, or even could, use the word. What are you a witness to?

Witness to whence I came, where I am. Witness to what I've seen and the possibilities that I think I see. . . .

What's the difference between a spokesman and a witness?

A spokesman assumes that he is speaking for others. I never

assumed that - I never assumed that I could. Fannie Lou Hamer (the

Mississippi civil rights organizer), for example, could speak very

eloquently for herself. What I tried to do, or to interpret and make

clear was that what the Republic was doing to that woman, it was also

doing to itself. No society can smash the social contract and be exempt

from the consequences, and the consequences are chaos for everybody in

the society.

“Witness” asks two questions I think every person in America needs to ask.

“Am I going to be a Witness?” and in today’s world, “Is that enough?”

https://hero-magazine.com/article/97264/benjamin-booker

“Get out there”

Benjamin Booker on funk, soul searching, and why we can’t stand by on world issues

In February 2016, Benjamin Booker had a problem. Despite the rousing success of his debut (self-titled) album and after some eighteen months touring he felt, in his words: “a songwriter with no songs, unable to piece together any words that wouldn’t soon be plastered on the side of a paper airplane”. He packed a bag, called his agent, and booked a flight to Mexico City. A month later he returned with an album, written and ready for production.

That album – Witness – is being released today, Friday 2nd June. Along with the Mavis Staples-featuring title track, which was released in March, Booker provided a statement detailing some of what was going through his head during his brief self-imposed exile, including a heartfelt consideration of the moral obligations that accompany being a witness in the age of Black Lives Matter. We talked to Booker about the creative and political influences behind Witness, art as a form of protest, and sharing an album name with Katy Perry.

GALLERY

Johnny Crisp: How are you feeling about the release of your second album?

Benjamin Booker: I’m feeling really good

about it. The response so far has been good. To me this was the hardest

thing that I’ve probably done, but it’s also the thing I’m most proud

of, so I’m excited to get it out there.

Johnny: Is there anyone you’ve been listening to since the last one that might come through?

Benjamin: Oh yeah – I’ve been listening to a

load of 70s funk music from Africa, so of course William Onyeabor, but

there’s a bunch of other bands from Nigeria and Ghana that I was pretty

heavily into as well. Also Sly and the Family Stone, they have this album called Fresh…

obviously I try not to take anything too directly but I think that if

people listen to the new record now they’ll hear that the album is more

rhythmic than last time. There was a strong emphasis on rhythm when we

were making it.

Johnny: Tell us about your trip to Mexico.

Benjamin: Almost everything was written in

the month that I was in Mexico City. It was on the plane ride over there

that things started to fall into place. I was reading this book, White Noise, by

Don DeLillo, and there was this sentence that said: “What we are

reluctant to touch often seems the very fabric of our salvation.” And I

was like, “Oh, man.” It just jumped out at me. I got a piece of paper

and said: “OK, for once just be honest with yourself about the kind of

person you are and the things that you need to deal with,” and I wrote

it all down. Then that bullet-pointed list became the outline for the

record. It was definitely the quickest that I’ve ever been, writing. I

think it just all made sense.

Johnny: What was it like working with Mavis Staples?

Benjamin: Oh, she’s the best. She was a big

influence on the album also. I wrote a song for her last record and it

was nice to really get to talk to her. She’s a bit older now and it was

nice to hear her talk about how she was just focussing on being present

and enjoying her family and her friends. That conversation was

important.

“[Mavis Staples is] a bit older now and it was nice to hear her talk about how she was just focussing on being present and enjoying her family and her friends. That conversation was important.”

Benjamin Booker. Photography Tomas Turpie

Johnny: You mentioned Trayvon Martin and the drastically altered political climate in the US. How much of an inspiration was BLM on the album?

Benjamin: Black Lives Matter was an inspiration for the main song on the album, Witness,

but the rest of the album isn’t about that at all, really. Most of the

album is about trying to work through your problems and hopefully come

out on the other side as a better person. I think that I had some demons

that I needed to get rid of. It’s about this period where I fled and

isolated myself, did a lot of soul searching, and came out hopefully a

little bit better.

Johnny: It’s certainly a bit different to 2014, out there.

Benjamin: For a long time I think it was

believable that people didn’t know the kinds of things that were

happening on the streets every day but what’s weird now is that people do know.

Everybody has camera phones and we see videos of these things happening

all the time, so it’s just more about just doing something. You know

what it is and if you choose now to not act, you have no excuses. I

guess that’s what I’m trying to say. Nobody can say that they don’t know

about what’s happening. You’ve seen it with your eyes.

“Nobody can say that they don’t know about what’s happening. You’ve seen it with your eyes.”

Johnny: Do you think art will become more of a stimulus for social action in the US?

Benjamin: I do think that. Look at Kendrick Lamar, his last album… and Alright,

they were chanting that at marches… I think that people just have to do

that now. People are realising… when I was in school or until recently

you would see civil rights videos and you would always think: “Wow, I’m

really glad that we got that out of the way.” Now people are

more: “Oh, shit! Not that much has really changed.” So I think that

there’s more work to be done. But I feel optimistic about it.

Johnny: Being aware of that is a positive thing, at least.

Benjamin: Yeah, we’ll see what they do. I

remember there was a women’s march here that I went to and there was a

sign that somebody had that said, “Now all you nice white ladies are

going to be at the Black Lives Matter march, right?” I don’t

know. People look out for their own interests, so I don’t know who’s

going to be the person to pull people together, you know. There’s not

really a leading figure. I guess there’s Bernie Sanders… we tried, we

tried.

Johnny: Did you know you are going to share an album name with Katy Perry?

Benjamin: Yeah! I found out about that, but I heard that her Witness

was about her travelling the world and witnessing all these cool

things, so I think it’s a little different. I don’t think anyone’s going

to get confused… but I would totally hang out with Katy Perry if she

wanted to do something.

Johnny: Anything else you’d like to add?

Benjamin: I just try and tell people that

it’s definitely overwhelming out there, but that they just have to get

outside. For me, I’ve been trying to volunteer more, reading, keeping up

on what’s happening. Go to marches. Donate money to organisations that

support people who need support. Doing little things that will make you

feel better about what’s happening and will help everybody a little bit.

Those are the kinds of things I’m trying to spread the word about. Just

do a little bit. Get out there. Volunteering is fun and you can only

watch so much Netflix. You gotta get outside.

Benjamin Booker’s second album, ‘Witness,’ is out June 2nd on ATO Records.

https://smashcutreviews.com/benjamin-booker-album-review-benjamin-booker/

Benjamin Booker Album Review: “Benjamin Booker”

https://www.wbur.org/news/2015/04/01/benjamin-booker

Benjamin Booker: Part Blues, Part Punk, The Whole Truth

When Benjamin Booker sings, people invariably think of the blues. His voice is like sandpaper trimmed in velvet, or asphalt cooked in the hazy summer heat: roughness enveloped by warmth. His songs are personal, visceral things. Although he takes a casual approach to diction, he says as much with his world-weary delivery as in his most starkly honest lyric.

“I was having a hard time, but really, the people around me were having a way worse time,” says Booker of the two years during college that inspired the songs on his self-titled debut. (He plays a sold-out show at the Sinclair in Cambridge on April 4.) “That was really, I guess, the hard part. And I really just wrote songs, individual songs, for people, that I would just share with friends. And that ended up being the first record. It’s just a collection of the songs I was writing for friends and family.”

As raw as Booker’s music is, the comparison to blues is somewhat facile. “Benjamin Booker” begins with “Violent Shiver,” a crescendoing garage rock number with furious drumming and a delirious “ooh-ooh” hook. The album is marked by manic cymbal crashes, dirty, distorted guitars, and rockabilly’s dramatic punctuations. The occasional blues riff makes its way in, along with the far-off warble of an electric organ.

Though Booker cites bluesmen like Blind Willie Johnson and Furry Lewis as influences, it was punk and noise music that prompted him to pick up the guitar in high school. He elected to attend college in Gainesville, Florida, primarily because of the punk scene there. Listening to his music, it is easy to see why Jack White was an early champion. Both are able to mine the needle-fuzzy rock ‘n’ roll of yore without ripping it off entirely, and Booker has an indie rocker’s penchant for descriptive specificity and wry philosophizing. “Even though computers are taking up my time/ Even though there are satellites roaming in space,” he sings in the soaring “Slow Coming,” “The future is slow coming.” (The new music video for “Slow Coming” puts the song’s political implications into blunt relief with references to the Civil Rights and #BlackLivesMatter movements and frank depictions of police brutality against African-Americans.)

“I really don’t make the music that I listen to, you know,” says Booker. “It’s weird because you can tell—I can see parts of things that I’ve listened to in the music, but I’ve listened to, I guess, so many different kinds of music that it comes out very differently. Yeah, I listened to a bunch of blues music, but I was also into Sonic Youth, so ‘Violent Shiver’—which is one of the songs off the album—I remember wanting a riff like ‘Teen Age Riot,’ the Sonic Youth song.”

WBUR is a nonprofit news organization. Our coverage relies on your financial support. If you value articles like the one you're reading right now, give today.

Booker, who lives in New Orleans, spent most of his childhood in Florida. His father was in the Navy and the family was very religious. Booker says that he began to question his faith at around age 13. Many of the songs on “Benjamin Booker” touch obliquely on religion (and losing it), but the impassioned “Have You Seen My Son” is perhaps the most nakedly autobiographical. “Told me that the world is full of sinners/ And placed a Bible at my feet/ I could hardly understand you/ I had just learned to chew my meat,” it begins.

But the song is not so much a rejection of religion or an admonition to its acolytes as it is a painful reckoning with the loss of faith. What does it feel like to know that your mother is praying for your salvation? “Heard that you were calling out my name, my name/ And you cried for a whole week/ Said ‘Have you seen my son?/ He’s lost in the world somewhere,’” Booker howls, his voice cracking with empathy. “They say that when a mother loves a child/ She would do most anything.” His break with religion is the final, wrenching fissure between mother and son that began with the cutting of the umbilical chord, and Booker, from the other side of the rupture, feels it. “I know I can never make it right.”

“It was also me realizing I couldn’t change the way that my family and other people felt,” says Booker. “And that even though we do see things differently, that [we were] just going to have to learn to respect each other.”

Booker has spoken candidly in interviews about some of the hard knocks that have influenced his songwriting: drinking and drugs at an early age, a friend struggling with addiction, his first year in New Orleans working for AmeriCorps and surviving on food stamps. Out of that lowness came swift success. Booker was signed to ATO Records on the strength of his first demo and, with the release of “Benjamin Booker” in 2014, found himself opening for Jack White and performing on the “Late Show With David Letterman.” These days, he tours practically nonstop. He has been slowly working up new material for the next record.

“The songs, and stuff that I’ve been writing about, [are] still about the people around me,” says Booker. “I guess a lot of bands, for their second record, it ends up just being about life on the road and sleeping in hotels and that kind of thing. And I was just like, ‘Ugh.’ I mean I just really don’t want to do that.”

Booker’s success has also made him cagier about the details of some of the events and people he sings about. “The songs are about them, and they know that they’re about them,” he says. “So it’s weird to talk about them in interviews and then see it in some magazine or something.”

Yet the singer retains a charming, easy openness. Towards the end of the interview, he laughs as he remembers vomiting right before going onstage to play a gig—not from nerves, but out of sheer exhaustion. In the pantheon of harrowing tour tales, it’s a particularly bleak one. But Booker has never been one to sugarcoat things. The unvarnished truth is always more interesting, especially if you can sing it.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Amelia Mason is an arts and culture reporter and critic for WBUR where she covers everything from fine art to television to the inner workings of the Boston music scene.

Her work has been broadcast on NPR’s Here & Now

and published on NPR Music, where she is proud to have contributed to

the canon-redefining “150 Greatest Albums Made By Women.” Once, she was a

Listening Party panelist for All Songs Considered and another time she won a regional Edward R. Murrow Award in feature reporting. In her spare time she plays the fiddle.

THE MUSIC OF BENJAMIN BOOKER: AN EXTENSIVE VIDEO OVERVIEW, A CROSS SECTION OF RECORDINGS, MUSICAL ANALYSIS AND COMMENTARY, PLUS VARIOUS INTERVIEWS WITH BENJAMIN BOOKER:

Benjamin Booker - Believe (Official Music Video)

Benjamin Booker - Full Performance (Live on KEXP)

Benjamin Booker - Witness (Official Audio)

Benjamin Booker: NPR Music Tiny Desk Concert

Benjamin Booker - Have You Seen My Son? (Official Video)

Benjamin Booker - Witness (Live at Columbus Theatre)

Benjamin Booker - Right On You (Live at Columbus Theatre)

Benjamin Booker - Believe (Official Music Video)

Benjamin Booker - Slow Coming (Official Video)

Benjamin Booker - Have you seen my son? - A Take Away Show

"The Slow Drag Under" (Free At Noon Concert)

Benjamin Booker - Violent Shiver (Live at The Current)

Song of the Day: Benjamin Booker - Violent Shiver - KEXP