SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2022

VOLUME ELEVEN NUMBER ONE

RAPHAEL SAADIQ

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

JON BATISTE

(December 25-31)

MULGREW MILLER

(January 1- 7)

VALERIE COLEMAN

(January 8-14)

CHARNETT MOFFETT

(January 15-21)

AMYTHYST KIAH

(January 22-28)

JOHNATHAN BLAKE

(January 29--February 4)

AUDRA MCDONALD

(February 5-11)

IMMANUEL WILKINS

(February 12-18)

WYCLIFFE GORDON

(February 19-25)

FREDDIE KING

(February 26-March 4)

DOREEN KETCHENS

(March 5-11)

TERRY POLLARD

(March 12-18)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/immanuel-wilkins-mn0003503146/biography

Immanuel Wilkins

(b. 1998)

Artist Biography by Thom Jurek

Immanuel Wilkins is a jazz saxophonist, composer, and bandleader from Upper Darby in greater Philadelphia. He is possessed of a round, warm, emotionally powerful tone, informed not only by the jazz tradition but gospel as well. Since his late teens, he has been a first-call touring sideman for a remarkable variety of artists who include Jason Moran, Gretchen Parlato, Solange Knowles, Bob Dylan, and Wynton Marsalis. Though the alto is his primary horn, he is also adept on soprano and tenor. In the studio he's worked as a sideman with bassists Ben Wolfe and Harish Raghavan, and vibraphonist Joel Ross; he also serves as an altoist in Orrin Evans & the Captain Black Big Band. In 2020, Wilkins released the Moran-produced Omega, his leader debut for Blue Note. Two years later he returned with his sophomore outing The 7th Hand, an hour-long suite in seven movements.

Wilkins was raised in Upper Darby, about a mile outside Philadelphia, by music-loving parents. He began playing violin at age three, switched to piano a couple of years later, and in third grade picked up the saxophone. His rationale for moving over to the horn was that he'd heard you could join band a year early if you had your own instrument (which he told his mother that when asking for a horn). Impressed by his logic as well as his musical appetite and ability, she bought him one. Wilkins honed his skills playing in church and studying in programs dedicated to teaching jazz at the city's storied Clef Club of Jazz and Performing Arts. At age 12, he was selected to play the "Star Spangled Banner" at a Philadelphia Eagles game. He studied music in high school and at the Kimmel Center, where, in addition to its regular instructors, it played host to top-tier jazz musicians including drummer Mickey Roker, bassist Jamaaladeen Tacuma, saxophonist Steve Coleman, and Sun Ra Arkestra bandleader Marshall Allen, who offered workshops and classes. Wilkins moved to New York City in 2015 to attend the Juilliard School, where he earned his bachelor's degree. There he studied with Bruce Williams and Joe Temperley. In the city, he met trumpeter and composer Ambrose Akinmusire, who acted as both mentor and facilitator in helping Wilkins navigate the jazz scene. He also met Moran, who admired the young saxophonist's sound and immediately grasped his potential. Moran took the young saxophonist on tour playing his tribute show, "In My Mind: Monk at Town Hall, 1959," a series of live performances honoring the legacy of the great jazz pianist.

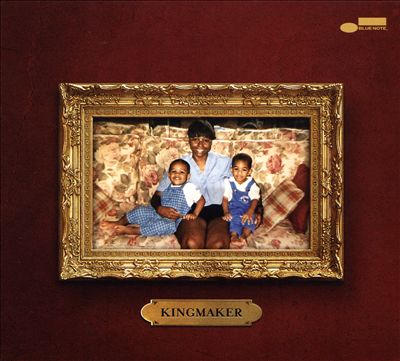

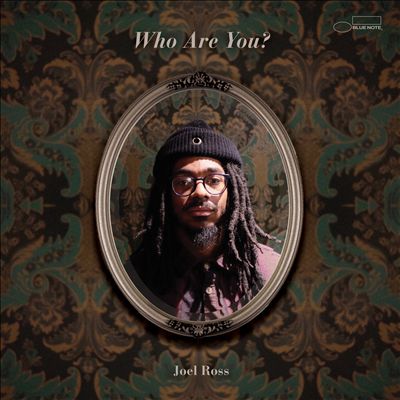

Along with his work as a musician, Wilkins is an instructor. He has taught at NYU and the New School, and/or given master classes and clinics at Oberlin, Yale, and the Kimmel Center. He formed his own quartet while attending Juilliard with pianist Micah Thomas, bassist Daryl Johns, and drummer Kweku Sumbry. The group worked in New York, backed singers and other soloists, and performed original material. In 2018, Wilkins began working with vibraphonist Joel Ross and was featured prominently on his Blue Note debut, KingMaker, the following year. In 2019, Wilkins and Ross, along with Thomas and Sumbry, also worked with bassist/arranger Harish Raghavan on his Whirlwind Recordings debut, Calls for Action. Later in the year, Wilkins signed a record deal with Blue Note.

Entering Sear Sound Studio in New York with his quartet and Moran as producer, Wilkins cut Omega, a collection of 11 originals, as his debut leader album. The date's music, as evidenced by the April pre-release single "Warriors," was informed by history, the Civil Rights movement, and the spiritual teachings of the Black church, as well as the continuing struggle for racial justice in America. The latter is directly signified by two tunes on the set: "Ferguson -- An American Tradition" and "Mary Turner -- An American Tradition." Omega was released in August of 2020. Wilkins appeared on two other key dates that year: vibraphonist Joel Ross' sophomore outing, Who Are You? and Orrin Evans & The Captain Black Big Band's The Intangible Between.

In January 2022, Wilkins released The 7th Hand, his second Blue Note offering. An hour-long suite composed in seven movements, it was performed by a quartet with pianist Micah Thomas, bassist Daryl Johns, and drummer Kweku Sumbry, with guest appearances by flutist Elena Pinderhughes and the Farafina Kan Percussion Ensemble.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/immanuel-wilkins

Immanuel Wilkins

Immanuel Wilkins is a saxophonist, composer, educator, and bandleader from the greater Philadelphia area. While growing up, Wilkins honed his skills in the church and studied in programs dedicated to teaching jazz music like the Clef Club of Jazz and Performing Arts. After moving to New York in 2015, he proceeded to earn his bachelor’s degree in Music at Juilliard (studying with the saxophonists Bruce Williams and the late, great Joe Temperley) while simultaneously establishing himself as an in demand sideperson, touring in Japan, Europe, South America, The United Arab Emirates, and the United States and working and/or recording with artists like Jason Moran, the Count Basie Orchestra, Delfeayo Marsalis, Joel Ross, Aaron Parks, Gerald Clayton, Gretchen Parlato, Lalah Hathaway, Solange Knowles, Bob Dylan, and Wynton Marsalis to name just a few. It was also during this same period that he formed his quartet featuring his long-time bandmates: Micah Thomas(piano),Daryl Johns(bass)and Kweku Sumbry(drums).

Being a bandleader with a working group for over four years has allowed Wilkins to grow both as a composer and as an arranger — and has led to him receiving a number of commissions including, most recently, from The National Jazz Museum in Harlem, The Jazz Gallery Artist Residency Commission Program (A collaboration with Sidra Bell Dance NY, 2020 ) and The Kimmel Center Artist in Residence for 2020 ( a collaboration with photographer Rog Walker and videographer David Dempewolf). Being emerged in the scene at a young age and sharing the stage with various jazz masters has inspired Wilkins to pursue his goal of being a positive force in both music and in society. This includes quite an impressive resumé as an educator. In addition to teaching at NYU and the New School, he has taught and given master classes and clinics at schools/venues like Oberlin, Yale and the Kimmel Center. Ultimately, Wilkins’ mission is to create music and to develop a voice that has a profound spiritual and emotional impact.

Immanuel Wilkins’s Divinely Inspired Jazz

The alto saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins is in pursuit of epiphany. The twenty-four-year-old jazz artist has said that he aspires to sprezzatura—a studied nonchalance that enables unconscious, idiosyncratic performance—and wants his music to be guided by the divine. Plucked out of Juilliard, in 2017, and taken on tour by the pianist Jason Moran, Wilkins made his name playing for artists such as Wynton Marsalis, Bob Dylan, and Solange, and recording on projects for the vibraphonist Joel Ross and the double bassist Harish Raghavan. Now both an accomplished composer and bandleader, he seeks to realize Black spirituality in his sound, and to find God in his music—or, at least, in the act of playing it.

Wilkins started performing on sax in church, at the age of four. He learned jazz at the storied Philadelphia Clef Club of Jazz and Performing Arts, where he was introduced to jazz greats such as Marshall Allen and Mickey Roker. Since 2016, he’s played in a quartet with Daryl Johns on bass, Kweku Sumbry on drums, and Micah Thomas on piano. Each player has his own religious outlook, but shares Wilkins’s conception of jazz as a conduit for worship. As a Philly native, Wilkins counts John Coltrane—whose home in the city’s Strawberry Mansion neighborhood is like a house of worship for jazz devotees—as an important influence on his music. With Coltrane’s vision of Black consciousness and spirituality as a guide, Wilkins’s music explores Black religiosity as a corrective to secular injustice.

On his 2020 début for Blue Note Records, “Omega,” which Moran produced, Wilkins depicted the Black experience as harrowing, beautiful, and consistently guided by faith. Songs referencing the lynching of Mary Turner and the shooting of Michael Brown, each appended with the tag “An American Tradition,” hinted at recurrent Black trauma with striking compositions that were both, by turns, chaotic and enthralling. On the former track, Wilkins’s sax screams out, interrupting a flitting, panicked tune; on the latter, he plays screeching notes that whiz out from the racket of his rhythm section. But the record also recognizes the Black church as a sanctuary from violence. “The Dreamer,” inspired by a poem by James Weldon Johnson (the lyricist of the hymn “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” which is widely known as the Black national anthem), is ruminative and full of longing, with gospel voicings that nod to the reassuring influence of Sunday services.

Wilkins sees the process of music-making as a religious experience in itself. “I’m trying to write music that facilitates a space for us to be religious vessels for the music—have us actually act as vessels for Jesus,” he told Jazz Speaks in 2018. For him, such an encounter can be articulated through jamming—through surrendering to songs and allowing the music to reveal itself. Wilkins’s new album, “The 7th Hand,” seeks Providence; the record attempts to define the role of ritual in Black spirituality, particularly the communal rite of performing with a band and serving as part of a whole.

The record’s brilliance lies in its effortless sense of unity; the interconnectivity of the performers feels entirely instinctive. (Wilkins opted to produce this album himself, in an effort to preserve his tight-knit band’s natural chemistry and closeness.) On “Don’t Break,” the sax and piano melodies overlap, as if setting a stage for the expanded drum section, played by the Farafina Kan Percussion Ensemble. When the band incorporates the flutist Elena Pinderhughes across two later tracks, it is as if the players have seamlessly realigned themselves to maintain musical equilibrium. On “Witness,” the drums recede into the background and Wilkins reins in his incendiary playing to give his twittering guest space to roam freely. They reconvene for “Lighthouse,” which makes the bedlam of bop sound calculated.

The music gets less and less constructed over the course of the album, but the players stay tethered together through their uncanny feel for one another. Even when ad-libbing, they find a balance between spontaneity and order. “Fugitive Ritual, Selah” is calm and reflective, turning over the same phrase repeatedly, with Wilkins’s plaintive sax underscored by soft, sobering work on the keys. His bleats whimper out in the early stages of the noirish “Shadow,” circling the track until the entire arrangement comes undone and his sublime playing loosens. In the fluidity and harmony of unscripted performance, Wilkins invites flickers of divine intervention.

Instruments are vessels for players, but “The 7th Hand” asks if players themselves can be vessels for something greater. The delivery certainly makes it feel like something is being conjured. The songs here build to an epic, fully improvised, twenty-six-minute conclusion, “Lift,” which evokes possession by the Holy Spirit. The song rarely dips in intensity for its entire run, and Wilkins’s sax reëmerges at several key moments to reëstablish the tone and pace: he opens with scattering notes, drops into nearly inaudible foghorn-like rips, ascends to points of instrumental virtuosity, and finishes pushing long, puffed inflections out over mashed piano chords. Throughout the track, the movement is uproarious, prone to outbursts, gurgling bass, chattering drums, and squawking sax. In this last stage of the band’s transcendent journey, the four players seem to give themselves up to an unseen power.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Sheldon Pearce is the music writer and editor for Goings On About Town.

Immanuel Wilkins: Omega

The brilliance of the 22 year old altoist and composer is plainly evident on each track of Omega, as is the deep and transformative talents of the young quartet he leads. Pianist Micah Thomas, bassist Daryl Johns and drummer Kweku Sumbry leave the listener with the understanding that these young artists are bound by the common thread of leading jazz music deep into the new century, bringing with them a style that is neither straight ahead or avant-garde. The quartet plays in a new firmament that employs deep lyricism and melodic content, surrounded by more than ample room for imaginative soloing that bears the imprint of modern life in this medium we can refer to as modern jazz. As an alto player, Wilkens glides between Charlie Parker and Ornette Coleman with no apparent degree of separation. The adventurous spirit of Gary Bartz comes to mind as well, most notably within the notion that Wilkens' playing more bears the traits of unbound restlessness and musical adventurism heard from intrepid tenor players following the vapor trail of the great John Coltrane.

That's a heap of praise and expectation for this young artist, and an entire generation of young players. To Wilkins' advantage is his time spent being mentored by the likes of Wynton Marsalis, Joel Ross, Gerald Clayton, Orrin Evans and Ambrose Akinmusire. Time spent touring with pianist Jason Moran provided refinement and positive direction, making him the perfect producer for this effort that represents one of the finest of this turbulent and historic trip around the sun for humanity.

The opener, "Warriors," epitomizes modern jazz in 2020, with an intricate melody swinging within polyrhythms, providing ample space for post-bop interpretation. Wilkins plays with fire, and shape shifts into more tender moments. It carries a message and a call to action and social responsibility, or as Wilkins remarks, "It's about us serving as warriors for whatever we believe in."

"Ferguson—an American Tradition," imagines the pulse of the nation in 2014, when Mike Brown Jr., an unarmed teenager, was shot and killed by a police officer in Ferguson, Mo. Officer Darren Wilson was not indicted, triggering a rage in the black community, and shedding light on centuries of deadly aggression directed toward African-Americans at the hands of the police. Wilkins' playing constitutes a dialog of revolution, his social awareness expressed through the lens of his sublime discipline of virtuosity rising from, and channeled towards, the real, everyday threat of police violence experienced by Black Americans.

Two pieces are more inspired by respect for generations past who have paved the way, both in terms of activism and musicianship for Wilkins, and a new generation of jazz artists. "The Dreamer" honors activist/author James Weldon Johnson, a ground floor founder of the NAACP. "Grace and Mercy" carries a similar vibe, with Wilkins and Thomas leading the way forward harmonizing the melody, and soloing introspectively between the graceful playing of Johns and Sumbry. While jazz composition among new generation artists tends to fall somewhere between jazz and modern classical music, these two melodies seem to eschew jazz music's transition to institutions of higher learning, and follow the path of jazz more in a neo-folk vein. Sumbry's drum and cymbal work creates a wider, more ethereal transition for the listener. His playing alone, alludes to this piece being the spiritual center of the album.

Undoubtedly, the four-part suite composed by Wilkins while still a student at Julliard stands out as the emotional epicenter of the entire concept from which this project arose. Both contemplative and unwound, "The Key" and "Saudade" feature exhilarating expressionism and melodic discipline, culminating in Wilkins' most explosive playing on the record. "Eulogy" features diametric ends of a thread that begins with Thomas' elegance and transitions into Wilkins' spiritual, soul searching intensity. Sumbry leads the band into "Guarded Heart," the finale of this 20 minute suite that lyrically characterizes the album.

The title track is the closer, and perhaps the most spiritually joyous of this collection of Wilkins' original compositions. Once again, Thomas is the piece of the rhythm section that stands out, gifting Wilkins with a harmonic and rhythmic base to solo with a profound sense of freedom.

As a new generation arrives on the international jazz scene, one comes to the realization that while much changes generation to generation, much as well, remains the same. It seems there is always young, unabashed talent waiting in the wings in jazz, which is of course, a huge positive. What makes this new generation special is the ability to blend generational traditions, delving into new modes and developing them with a tap root still firmly inplanted in generations of jazz history. Innovation has a habit of floating endlessly in a sea of isolation and emptiness without being attached to something that has meaning over time. Wilkins can be aggressively austere, searing and unabashed, as well as sensitive and embracing, often within the confines of a single solo. His playing is electric within a staggering tonal range. Omega just may be one of the most relevant recordings of this epic year of 2020, if not for its acceptance of social responsibility, then for its sheer virtuosity, and colorful melodicism. The future of jazz is in the hands of musicians like Wilkins, and a host of others too populous to name. That marvelous fact gives jazz fans much needed worldwide hope, steeped in trust.

Track Listing

Warriors; Ferguson-An American Tradition; The Dreamer; Mary Turner- An American Tradition; Grace and Mercy; Part 1: The Key; Part 2: Saudade; Part 3: Eulogy; Part 4: Guarded Heart; Omega

Personnel

Immanuel Wilkins: saxophone, alto; Micah Thomas: piano; Daryl Johns: bass; Kweku Sumbry: drums.

Album information

Title: Omega | Year Released: 2020 | Record Label: Blue Note Records

http://www.immanuelwilkins.com/about

About

The music of saxophonist and composer Immanuel Wilkins is filled with empathy and conviction, bonding arcs of melody and lamentation to pluming gestures of space and breath. Listeners were introduced to this riveting sound with his acclaimed debut album Omega, which was named the #1 Jazz Album of 2020 by The New York Times. The album also introduced his remarkable quartet with Micah Thomas on piano, Daryl Johns on bass, and Kweku Sumbry on drums, a tight-knit unit that Wilkins features once again on his stunning sophomore album The 7th Hand.The 7th Hand explores relationships between presence and nothingness across an hour-long suite comprised of seven movements. “I wanted to write a preparatory piece for my quartet to become vessels by the end of the piece, fully,” says the Brooklyn-based, Philadelphia-raised artist who Pitchfork said “composes ocean-deep jazz epics.”

Conceptually, the record evolves what Wilkins begins exploring on Omega, which included a four-part suite within the album. On The 7th Hand, all his compositions represent movements, played in succession. “They deal with cells and source material like a suite would,” says Wilkins, “but they function as songs, as well.”

While writing, Wilkins began viewing each movement as a gesture bringing his quartet closer to complete vesselhood, where the music would be entirely improvised, channeled collectively. “It’s the idea of being a conduit for the music as a higher power that actually influences what we’re playing,” he says. The 7th Hand derives its title from a question steeped in Biblical symbolism: If the number 6 represents the extent of human possibility, Wilkins wondered what it would mean — how it would sound — to invoke divine intervention and allow that seventh element to possess his quartet.

Wilkins often draws inspiration from critical thought. Even the striking album artwork challenges convention: “I wanted to remix the Southern Black baptism, and also provide critique on what is considered sanctified and who can be baptized.”

On “Emanation,” Wilkins’ hallmark conviction arrives in the first phrase. Imaginative and buoyant, he navigates layered interactivity before passing lead energy to a receptive Thomas. The movement finishes seemingly in the middle of a vamp — a reflection of Wilkins’ treatment of time. “In music, time is questionable,” he says. “It can challenge the notion of what time is and how you feel time.”

Wilkins sought to create an upside-down triangle of metric modulation through the recording. “Each piece is related to the next rhythmically by a triplet meter,” he says, “so it goes down by a triplet until the fourth movement, then it goes up by a triplet to the fifth movement, then to the sixth, and the seventh is free.” He crafted this concept in part for the feeling of seamless motion.

“Don’t Break” honors Wilkins’ friendship with Sumbry, and the influence they have on each other’s expressions. Featuring the Farafina Kan Percussion Ensemble, with which Sumbry regularly performs, the composition provides cyclical elasticity and an explicit representation of Wilkins’ concept. “When I think about vesselhood, I think of African practices of spirit possession,” he says. “You see that in most of the African Diasporic spiritual practices; Yoruba, it’s on the drums to call down a deity, and then the dancer gets possessed by that deity. But it’s kind of universal, across all African practices — including in the Black Church where you catch the Holy Spirit — and it’s directly linked with the spiritual power that the drum carries and how it’s able to channel that power.”

Wilkins composed “Fugitive Ritual, Selah” as a hymn to Black spaces. He drew inspiration from the energy of places where Black people gather in celebration, praise and refuge, away from a pervading culture of surveillance. “Selah means pause — one definition is to give space for the Holy Spirit,” he says. “I was fascinated with the idea that generally there are no white people in Black churches. If you go to a Black church, there’s no white people there [laughs]. It’s not like they’re not welcome. But somehow, the Black church has proven to be a space where magical things can transpire, within the space, on a quantum level.” Johns’ tender treatment of an introductory melody channels that feeling. “Daryl takes really beautiful solos,” says Wilkins. “I’m always pretty intentional about giving him space to do that and tailor-make a moment for him.”

The middle point of the seven movements, “Shadow” serves as the lowest-metered piece. Wilkins offered his bandmates Wayne Shorter’s composition “Fall” from the Miles Davis album Nefertiti as a musical reference, modeling “Shadow” after its essence. “I wanted them to be almost minimalist in their approach,” he says. “I wanted it to be pretty stripped down to basic swing, basic walking, to allow me and Micah to be a little creative but still have the melody going at the same time. It’s really about the melody, but it lends itself to creativity.”

The introduction of lyrical and textural dimension from flutist Elena Pinderhughes proves intentional, as well. Appearing on “Lighthouse” and “Witness,” whose melody features blossoming half-notes, Pinderhughes serves as an element of activation. Combined with Thomas’ mellotron, her flute acts as a vehicle to invoke divine intervention: “I thought of subtly introducing two new voices that emanate from the source of the band. There’s this Bible verse: “When two or three are gathered here in my name, there am I in the midst.”

Perhaps the most compelling movement develops over the course of 26 minutes. When they’d perform “Lift” live, the quartet never quite knew how the music would manifest. Sometimes the gesture would conclude after 10 minutes, sometimes 45. “We had no idea of how long it would be,” says Wilkins, “but in the studio we were like, ‘Let’s just go until it’s right to stop.’” The Pentecostal character of “Lift” tasks the listener with practicing radical empathy, according to Wilkins; the ritual of speaking in tongues emanates across arcs and cycles. “To an outsider, it’s gibberish or meaningless,” says Wilkins. “But those tongues send codes to the Creator. To the slave owner, Aunt Hester’s screams were just screams. But to the other slaves, those screams carried messages to flee, to sing, to run, to keep working — a host of things. So, I was fascinated with that, too — stream of consciousness or speaking in tongues carrying messages that listeners may not understand.”

Whether The 7th Hand reaches full vesselhood matters less than the attempt itself. Wilkins and his bandmates reveal their collective truth by peeling themselves back, layer by layer, movement by movement. “Each movement chips away at the band until the last movement — just one written note,” says Wilkins. “The goal of what we’re all trying to get to is nothingness, where the music can flow freely through us.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/01/arts/music/immanuel-wilkins-7th-hand-review.html

Critic’s Pick

On ‘The 7th Hand,’ Immanuel Wilkins Sees Jazz as an Escape Pod

The alto saxophonist’s second album is blues-based, gospel-infused, intellectually considered music that secures his quartet’s commanding status on the scene.

- The 7th Hand

- NYT Critic's Pick

The alto saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins and his quartet make bristling, physical music, both leaning into and pulling against the swing rhythm that has historically been the backbone of jazz. There’s a certain sensuality to classic swing, an element of taking your time that doesn’t seem at home amid the hamster-wheel feeling of life today. Wilkins has wisely left that part behind in favor of a layered, exploding-grid approach to rhythm.

Still, there’s no confusing that this is blues-based, gospel-infused, intellectually considered music, from concept down to craft. All of which qualifies it neatly as part of the jazz tradition (pardon the four-letter word).

But it’s much harder to locate his major saxophone influences than to position him in a broad lineage — which is a sign of how widely Wilkins, 24, has listened. Soon after Blue Note Records released his debut album, “Omega,” in 2020, I found myself nagged by that question: Whose alto playing casts the biggest shadow over Wilkins? Comparisons to legends like Jackie McLean or contemporaries like Logan Richardson didn’t feel right. It was J.D. Allen, a saxophonist one generation ahead of Wilkins, who solved the riddle, in a chat that summer: When he listened to Wilkins, he said, James Spaulding came to mind. It made sense on a few levels.

One of jazz history’s crucial supporting cast members, Spaulding was a frequent presence on classic Blue Note albums in the early ’60s. But he also spent time playing rougher, more atonal stuff with Pharoah Sanders, Sun Ra, Billy Bang and others. Skating alongside the tempered scale, Spaulding, now 84, might blow squirrelly, zigzagging lines at a thousand notes a minute, or pause to tug at a single note from multiple sides. These are shoes that Wilkins walks in.

But he has made himself known as a composer, too, to a degree Spaulding never did, and in just a few years, his quartet — with Micah Thomas on piano, Daryl Johns on bass and Kweku Sumbry on drums — has become a band that members of the young generation can measure their own ideas up against.

“The 7th Hand,” Wilkins’s newly released second album, confirms the quartet’s commanding status on the scene. Another collection of all originals, it is just as unrelenting as “Omega.” On tunes like “Don’t Break” and “Shadow,” Wilkins and Thomas play the melody in loosely locked unison, shifting in and out of keys, tilting and rocking the harmonic floor beneath them. Moving like this, Wilkins can switch emotional registers, even genres, with the flick of a wrist: A simple blues lick transposes into what sounds like a heart-tugging soul line, then scrambles up into something that’s undeniably jazz.

“Don’t Break” includes a cameo from the Farafina Kan percussion ensemble (with which Sumbry often performs), weaving its West African hand percussion into the flow of the quartet and proving that Wilkins’s progressive take on rhythm still connects easily with its roots. The album’s other guest artist, the flutist Elena Pinderhughes, makes a strong impression on back-to-back tracks, “Witness” and “Lighthouse,” with a hard-blown and soaring sound that will be immediately recognizable to listeners who’ve heard her in Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah’s recent groups. Throughout the album, Thomas’s dazzling presence across the entire keyboard gives the quartet much of its depth; he’s on his way to becoming a prominent bandleader in his own right.

Wilkins has said that with “The 7th Hand,” he was looking for nothing less than spiritual transmission — to make himself and the quartet into a “vessel” for the divine, in the way of a Mahalia Jackson, or a John or Alice Coltrane. Biblically, the number seven represents completion and the limits of human endeavor: On the seventh day, we rest. The album’s seventh and final track is a 26-minute free improvisation titled “Lift,” which Wilkins saw as an opportunity to set aside his own map and let spirit take over. The quartet unspools its finely woven, vigilant group sound into something wide open, achieving a kind of escape. Thomas and Sumbry sometimes sound like the free-jazz pioneers Cecil Taylor and Sunny Murray going at it; elsewhere, Wilkins and the drummer collide with the combustive power of John Coltrane and Elvin Jones.

Wilkins’s idea to use this album as a means of transcendence — of exiting the body and disappearing into sound — isn’t just about worship. In interviews, he has cited contemporary theorists like Arthur Jafa with providing crucial inspiration, and he’s spoken about seeking an aesthetics of abstention: from being watched, from being sorted into commercial bins. It’s in line with a larger current in Black radical thought today, shepherded by figures like Jafa and Fred Moten. In “Glitch Feminism,” published in 2020, the writer and curator Legacy Russell proposes rethinking our entire relationship to the human body — a site of so much labeling and othering. “The glitch,” she says, is a place where we might reject capture and embrace “refusal.”

It’s possible to hear “The 7th Hand” in a similar way. In her liner notes, the poet Harmony Holiday calls this album “the sound of turning away from ourselves to get back to ourselves, of how abandon can be organized into liberation with the right set of adventures and a beat to unpack them by.”

Immanuel Wilkins

“The 7th Hand”

(Blue Note)

A version of this article appears in print on Feb. 3, 2022, Section C, Page 5 of the New York edition with the headline: Working to Become A Vessel for the Divine. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper

Immanuel Wilkins Aims to Communicate the Spirit Within on The 7th Hand

The alto saxophonist speaks of the Pentecostal Church, the Book of Ezekiel, the concept of vesselhood—and braising short ribs

On an unseasonably warm evening in December, just at the opening break of Omicron and yet another shift in everyone’s lives, alto saxophonist/composer Immanuel Wilkins is busy in his new Brooklyn home. Cooking. A lot.

Calm in the face of a just-canceled show at the Village Vanguard while readying The 7th Hand—his second Blue Note album with his longtime quartet (pianist Micah Thomas, bassist Daryl Johns, drummer Kweku Sumbry)—Wilkins passionately runs through cuisine-related minutiae as if he were tightening his ligature or wetting his reeds.

Preparing braised short ribs with more tinkling and crashing than you might hear from his drummer’s cymbals at a gig, Wilkins laughs as he discusses the joy of cooking. “I had spent so much money on exorbitant dinners before COVID that I didn’t want to suddenly start having sad meals while stuck at home,” he says of having hooked himself up with quality chef tools to prepare his favorites. “My easy go-to is salmon, but I can cook a mean duck breast. I can also do vegan. Both ends of the spectrum.”

Having moved during the pandemic from the Philadelphia area’s Upper Darby Township, where he was born and raised, Wilkins has made many recent changes beyond honing his culinary skills. The most immediately noticeable one for those familiar with his debut album—August 2020’s raw, sometimes mournful, sometimes incendiary Omega, which got him a Best New Artist nod in this magazine’s Critics’ Poll last year—is in the production department. Whereas Omega was produced by pianist Jason Moran, on The 7th Hand Wilkins has taken the reins himself.

“The desire to produce came from the fact that this music was special to me, a little more sacred,” he says. “The band and I had a natural way of playing through this music. Everything was pretty set, and I thought that it was just best if we had no outside influence in the recording process.” (There’s been no break with Moran, the man who took Wilkins under his wing, brought the saxophonist on a tour of Europe, and introduced him to Blue Note president Don Was; he remains a close friend.)

When Wilkins says that the music was sacred, he means it in both a figurative and a literal sense. The 7th Hand’s connection to God, and to spiritual reverence, is deep. “My relationship to my spiritual practices and to the church has grown more philosophical,” he says. “With that, I’ve come to realize the parallels—that my music sits in a really interesting intersection between my spiritual practices and my critique of Black social life and Black America [as heard on Omega tracks like “Ferguson (An American Tradition)”]. That intersection is a place that essentially escapes the white gaze of the outside: a place where amazing and beautiful things happen, hilarious things happen, and where there is mental and musical growth.”

“I was writing a suite that would prepare me to become a vessel for the Creator.”

Vesselhood

The church Wilkins speaks of, in Upper Darby (and in his heart, of course), is where this all starts. He and his family started off as Baptists, but they became part of the Pentecostal Church—Prayer Chapel Church of God in Christ, to be precise—and have never left. Even though he lives in Brooklyn now, the saxophonist and his quartet are still involved in the church’s outreach programs, giving out food to community members on Fridays. Wilkins also plays piano at the Upper Darby church on Sundays when he gets back to town, taking on hymns and popular gospel songs.

“I started playing saxophone when I was at the Baptist church,” Wilkins says, referring to himself at age four. “By the time we got to the Pentecostal church, I continued on the saxophone and picked up the bass and piano. What’s special about that church—and it’s known for its high caliber of musicianship—is that everyone is coming there of their own volition. No one playing in church is getting paid. Though I was a specialist by playing saxophone, you learn to become more utilitarian and play other instruments because you never know when you have to fill in.”

Among the things that interest Wilkins, and that The 7th Hand is meant to explore, are (in his words) “how to act as water, how we progress as a people yet still hold onto core values, how the church exists on an unexplainable quantum level—the special things that happen when you have oppressed people, who continue to be oppressed, gathering in a space to celebrate.”

As he says this, I’m reminded of Brian Wilson saying how the Beach Boys’ Smile album was a teenage symphony to God, or how John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme served as the highest extension of his religious beliefs. Like A Love Supreme, The 7th Hand is a suite, but in seven parts rather than four. And with that Biblically symbolic number, the heart of Wilkins’ thesis statement is revealed: In the Book of Ezekiel, God commands the prophet to build an altar measuring six cubits and one handbreadth. The number six represents the extent of human possibility, while seven connotes divine intervention. “I was writing a suite,” Wilkins says plainly, “that would prepare me to become a vessel for the Creator.

“In a lot of ways, I see this vesselhood directly related to performance art in that we are presenting our bodies as a sacrifice,” he continues. “By the seventh movement [the 26-minute “Lift”], we’re completely surrendered to the piece. There is no written material, so it’s all completely improvised. The player has no option but to be filled, no option but to catch the Holy Spirit, no option but to be a vessel by that seventh movement.” As in church, there’s no conscious decision; the Spirit happens to you. Through you. With you.

“I think that I created the seven movements as a preparatory piece,” Wilkins says, “a conveyor belt where, once you’ve entered and are on it, you’re on your way. That’s what makes The 7th Hand more inherently spiritual than Omega to me, that feeling of surrender and its intentionality: how each movement deals with a certain sector of Black life pertaining to spirituality. By that seventh movement, or vignette, we have achieved liftoff into another realm.”

Collective Spirit

That “we” includes the rest of Wilkins’ quartet: Thomas, Johns, and Sumbry, all of whom have been playing with the saxophonist since 2016. What spoken and/or unspoken discussion makes them fully in tune with their leader’s trip? Is his God their God?

“I have a fair picture of their individual spiritual walks,” Wilkins says of his bandmates. He and Sumbry lived together in Harlem for three years, with Thomas visiting often. “They knew what was going on from jump. Being friends for such a long time meant that they were down for whatever I dream up. More importantly, there’s an understanding that this is their experience as well, that they can use it as a vehicle for themselves, to experience their own idea of vesselhood. Because we’re all surrendering. Without surrender, this music doesn’t work.”

Like Wilkins, Micah Thomas is a proud believer who credits church organists such as Eddie Brown and Derrick Jackson (along with Cecil Taylor, Sullivan Fortner, and Moran) as direct inspirations. He met Wilkins when both were attending Juilliard, and he was immediately attracted to the saxophonist’s skill sets. “His playing felt strong to me right off the bat, and his compositions felt like home,” Thomas says. “By about a year of playing together, I started noticing that we had—almost unconsciously—produced a ‘sound’ together, and that it was now easier for me to play with him than other horn players.

“Often it seems like we either arrived at similar conclusions at the same time, or one of us will influence the other and then we’ll forget where the idea started,” he continues. “I think Immanuel’s writing pushed me into checking out the Black gospel music tradition. I’d also say that he is the more gifted and developed composer, so playing his music and talking to him about writing has helped me on my compositional path.”

And what about this vesselhood thing? Thomas says that, while playing the newer material, there exists “a sense in which I feel like I’m not in control when I’m playing music. At that ideal stage, it feels like I am obeying instructions from somewhere else—that I’m simply making what I know somewhere deep inside of me to be the right call at any moment. I wonder if that’s a deeper, truer part of me that lies beneath my ego and operates in a way that my ego doesn’t understand. And that feels like the part of me that would be closer to God.”

Kweku Sumbry is not affiliated with the Pentecostal Church; he was raised in the traditional spiritual practice of the Akan from Ghana, West Africa. While Wilkins was at Juilliard, Sumbry was a student at the New School. During a 2015 rehearsal sub session there with a mutual friend, vibraphonist Joel Ross, the drummer got his first opportunity to jam with the saxophonist. “Not exactly sure why, but Immanuel and I hit it off immediately,” he says. “Maybe it had something to do with us both having dreadlocks, but we became really good friends after that session. Immanuel has always given the band free will with his music, stressing that the drums pretty much be the director of the band. I think that my strong background in percussion, and West African folklore has helped drive Immanuel to include the African diaspora in what he writes, and what we play.”

Sumbry sees his role as conduit for a higher power differently from Wilkins. “We all are critical free-thinking folk, and even though I wasn’t raised in the church, my family is very committed to prayer, ceremony, and spirit. Micah’s father is actually a preacher, and he and I always make room for religious and spiritual dialogue. I remember we played in Philly in the summer of 2018 and Immanuel put us up in his family’s home, and his mother literally dragged us to church Sunday morning after our gig. I think we all look at music as a language of the holy spirit. This band is filled with really special people, and each individual has his own way of igniting spirit within the music.”

“I’m always Philly. I may live in New York but I’m Philadelphia, through and through.”

Past Inspiration

As we discuss the elements of spirit, ritual, and repetition in his newer music, Wilkins and I reach the topic of latter-day Coltrane: A Love Supreme, Ascension, Meditations. “I’ve been having these conversations with friends as to why John Coltrane’s music sounds like church,” he says. “And what I arrived at was that Trane with his quartet was employing spiritual practices in the music. So along with repetition, there’s sheets of sound and modality in which to contend—straight-up spiritual practices such as Buddhist chants or tarrying as in Black churches. Implementing this was important.”

Wilkins’ levels of longtime influence include various elders of Philly jazz: Jamaladeen Tacuma, Orrin Evans, Mickey Roker. “We carry our ancestors and traditions on our back, Philadelphia included, especially as we play a naturally improvisatory music,” he says. “Besides, I’m always Philly. I may live in New York but I’m Philadelphia, through and through.”

In past conversations with this writer, Wilkins has discussed his love of Coltrane, Mingus, Ellington, Benny Carter, Ornette Coleman, and Henry Threadgill. Brazilian guitarist Pedro Martins is a more recent love, as are Albert Ayler, Cecil Taylor, Charles Lloyd, and Milford Graves. His affection for Graves is so ardent that Wilkins and Sumbry recently joined John Zorn in a memorial celebration for the late multi-discipinarian. “Me and Kweku have bonded over Graves for a while, especially his time playing for Ayler. And Micah is very into Cecil Taylor too at present.”

Much of the angularity of Ayler and Taylor can be found in the more frenzied phases of The 7th Hand. The lengthy percussive slot during the looped lullaby of “Don’t Break” (an exhaustive treatise on “Black footwork where the dancer is in a trance and dances like the deity which possesses them,” says Wilkins says) conjures elements of James Brown. The quick curlicues in the middle section of “Emanation” are even reminiscent of Frank Zappa’s 1970s-era chord changes. “My father is a huge Zappa fan—that must be coming through the genes,” Wilkins says, laughing.

Beyond all of it, there’s the blues, much more of it here than on Omega (especially during the track “Shadown,” on which Ornette looms large). “How the blues came about, those transformative moments of inception, were important to this album,” Wilkins says. “The blues coming out of Negro spirituals, songs sung on the plantation mixed with moans and cries, is how we got this nearly-unexplainably spiritual sound that then infiltrates the Black church to become the centerpiece of hymns, and the way that Black sacred music moves from that point forward.”

Becoming Water

The cover image of The 7th Hand—a baptismal ritual with Wilkins at its center—depicts a transformative moment: “when Africans became African Americans, something that surely happened on the water,” he says. “I was thinking of water as a transformative element. The immersion of being baptized, and the immersive experience of becoming a vessel, what it means to catch the Holy Spirit.”

Catching the Holy Spirit is one thing, but releasing it was quite another. For the follow-up to Omega, Wilkins and crew had several albums’ worth of material ready to go. “We’re backlogged with music that we’re comfortable with but have not yet recorded,” Wilkins acknowledges. What was comfortable enough to warrant forward movement were The 7th Hand’s tracks, honed during a vigorous four-day residency at SEEDS::Brooklyn in Prospect Heights. “Within the conditions of a pandemic with no tour, it’s tricky to catch a live vibe, so that residency was nice, and led directly to us going into the studio in August. We knocked it all out in one day, then focused on refining it.”

The power of gathering, as depicted in “Emanation,” unfolds on the axis of the Bible verse that inspired it. “When two or three gather together, there am I in the midst,” Wilkins repeats. “I love that idea, how gathering can generate an emanation.” “Fugitive Ritual, Selah” looks at Black church custom with an eye toward Twitter and TikTok (“super-hilarious stuff inside of churches with people cutting up, but also being introspective and prayerful”). With “Don’t Break,” the shouting of Black church ritual, African dance, and Double Dutch become one.

In Wilkins’ experience, as The 7th Hand makes plain, God is never on a shelf or stuck in a book; God is a living, breathing thing. The saxophonist connects that experience to his other daily practice beyond prayer: playing jazz.

“I feel this way on the bandstand,” he says. “When you get into this mode and are no longer in control of what is being played. You’re just watching the rest of the world pass you by—you become a witness. That’s the pillar of vesselhood, the mark of being there.”

Read about Wilkins’ first album, Omega.

Immanuel Wilkins and Itamar Borochov Are “Rising Stars”

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immanuel_Wilkins

Immanuel Wilkins (born 1998 ) is an American jazz musician ( alto saxophone , composition ) of modern jazz . [1] [2]

Live and act

Wilkins grew up in Upper Darby , in the Philadelphia area. He gained his first musical experiences in his community church, which led him to attend jazz courses at the Clef Club of Jazz and Performing Arts . In 2009, as a teenager, he was given the opportunity to perform the national anthem before the Philadelphia Eagles game . Wilkins studied at the Juilliard School with Bruce Williams , Steve Wilson and Joe Temperley . In the course of his career to date he has worked e.g. starring Jason Moran , Gerald Clayton , EJ Strickland , David Weiss , Ben Wolfe, the Count Basie Orchestra ( Ghost Band ), Gretchen Parlato , Solange Knowles , Bob Dylan , Harish Raghavan ( Calls for Action , 2019) and Wynton Marsalis ; he also contributed to Michael Dease 's album Father Figure (PosiTone, 2015). [3]

Wilkins led his own band in the late 2010s, performing his own compositions and performing at jazz clubs and venues such as The Jazz Gallery , Smoke , Jamaica Center of Arts [4] and Smalls . In 2020 he presented the debut album Omega , which he had recorded with Micah Thomas , Daryl Johns and Kweku Sumbry ; [1] [2] because Wilkins has "the inventiveness of a veteran" despite his age, it is one of the important jazz albums of the year for Die Zeit . [6]

He is also a member of the quartet Dezron Douglas / Jonathan Blake and The Generation Gap and the formations of Philip Dizack and Noam Wiesenberg [5] and is part of the band Good Vibes on the first two albums by Joel Ross , KingMaker (2019) and Who are you? (2020) and Blake's Homeward Bound (2021).

Discography

- Omega ( Blue Note Records 2020) [7] [2]

- The 7th Hand (Blue Note, 2022)

Web links

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/the-7th-hand-immanuel-wilkins-blue-note-records__3415

Immanuel Wilkins: The 7th Hand

| Play Immanuel Wilkins on Amazon Music Unlimited (ad) | |

Searching for nothingness in a culture of excess, "Lift," the seventh and closing exhortation to empathy that guides The 7th Hand, is majestic in its creation. It emanates, it culminates, it blesses. From clouds of revelation, it formulates, like Om, like Ascension, into holy music which must be heard. Wilkins, the ever determined spirit, while his stalwart compatriots—pianist Micah Thomas, bassist Daryl Johns, and drummer Kweku Sumbry—provide the shifting sands at his feet, the winds which blow equally with him and against him.

"Lift" alone is worth the price of admission. "Lighthouse," "Witness," "Emanation," and the thrilling whole of The 7th Hand cover the drink minimum, dinner, and taxi home. This is music on a whole other level. Tight as a three-minute-single, the quartet seizes each of Wilkins' heady concepts and questions of time with a cutting vigor and dynamic which only comes by once in every generation.

In closing, The 7th Hand proves that we can think big again, that we can imagine beyond self-inflicted or political margins again, and that the zeal for something better is not only possible, but truly within our grasp.

Track Listing

Emanation; Don’t Break; Fugitive Ritual, Selah; Shadow; Witness; Lighthouse; Lift.

Personnel

Immanuel Wilkins: saxophone, alto; Micah Thomas: piano; Daryl Johns: bass; Kweku Sumbry: drums.

Additional Instrumentation

Elena Pinderhughes: flute; Farafina Kan Percussion Ensemble: Kweku Sumbry: lead djembe, bass djembe; Agyei Keita Edwards: lead djembe; Adrian Somerville Jr.: sangban; Jamal Dickerson: doundunba; Yao Akoto: kenkeni.

Album information

Title: The 7th Hand | Year Released: 2021 | Record Label: Blue Note Records

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/immanuel-wilkins-omega-is-just-the-beginning-immanuel-wilkins

Immanuel Wilkins: Omega is Just the Beginning

"It's important that there are inner city schools with music programs, there are things that really work toward gender equality, making sure everybody feels welcome in these spaces. "—Immanuel Wilkins

All About Jazz caught up with Wilkins after his stellar Newport set and along with three-time JazzWeek Jazz Programmer-Of-The-Year winner and music director Derrick Lucas of Jazz 90.1 WGMC, Rochester, NY (All About Jazz and Derrick collaborated on this interview, and we identify Derrick Lucas' questions with 'AAJ-DL.') we were able to learn more about Wilkins and his journey from a childhood in Philadelphia to the stage of the Newport Jazz Festival.

All About Jazz-Derrick Lucas: Immanuel, congratulations on that burning set.

AAJ-DL: Immanuel, tell me what did you learn last year as an artist, as a man with everything that happened?

IW: That's a good question. Wow, what did I learn? I learned to be more patient and to sit on my ideas longer, honestly. That was a good thing about the pandemic, we had time to sit with ourselves and sit with our ideas and actualize them and realize them in the best way possible, so slowing down is important.

AAJ-DL: So, as you know as an artist, a lot of folks just want you to play your saxophone but then there are a lot of people who say, "Say something with your saxophone. Bring social change, do something, make the world a better place." As an artist how do you deal with that, you've got so many different worlds pulling at you but you're an artist, you want to create so how do you handle that?

AAJ-DL: Who do you perform for, yourself, the musicians on the bandstand, or the audience?

IW: You know I actually go back and forth, I think it's a combination of myself and the musicians on the bandstand. I think the beautiful thing about all types of art is the onlooker gets to listen in and that's the beauty of what we do. The onlooker gets to hear the conversation the musicians are having. A lot of it is an experience for me and an experience for the band mates, I think that the art world is completely, music, movies, everything in the art world exercises that muscle of empathy. The beautiful thing is that we can listen in to what these people are doing and put ourselves into their shoes and go on the journey with them.

AAJ-DL: Immanuel, what does it mean for you to play at the Newport Jazz Festival?

IW: Man, it's a dream, it's an honor. I played here for the first time 2 years ago before the pandemic, the last Newport Jazz Festival, with vibraphonist Joel Ross and they were gracious enough to have me bring my band out this time. You know, as I was playing I was having images going through my head of Trane (John Coltrane) at Newport or Pops (Louis Armstrong) at Newport, you know what I mean, you see pictures and think wow, this is a high honor. I'm thankful, grateful and humbled to be on these hallowed grounds.

AAJ-DL: You work in the school systems, you work with kids. Why is it so important to you to make sure that you can connect the youngsters with this music because so often as you know and you can see so many public schools don't have music programs, don't have instruments anymore and you know the dollars are falling, why is it important for you to keep the dominos from falling?

AAJ-DL: So inside and outside of jazz who have you been listening to these days?

IW: Good question, lets think,.Okay, there's this really great artist Taja Cheek, her stage name is L'Rain, she has a record out called Fatigue (Mexican Summer, 2021) that has been on Sirius loop since it came out. Its a really amazing record.I've also been listening to Ruben Fox who's an amazing tenor saxophonist, he just released a really amazing record Introducing Ruben Fox (Rufiio Records Limited, 2021) and then I've been listening to Coleman Hawkins and listening to a lot of Johnny Griffin.

AAJ: During your set it was like I could see all those great players that came before you nodding their head in approval.

IW: Thank you, that means a lot I try my best but I'm standing on the shoulders of my ancestors so I'm trying to sound like them (laughs)

AAJ: So, who did you listen to back in the day, who influenced you?

IW: Oh man, growing up it was Kenny Garrett that was my first love,soon after that was Ben Webster, Johnny Hodges, those two really sold me. My big brother of sorts was Justin Faulkner, he plays in Branford's (Branford Marsalis) band. So he would come off tour, he had just got that gig he was like 16 I was like 9,10 something like that. Anyway he had just got the gig and he would come off the road and kind of regurgitate all that information to me. Brandford was telling him you need to be checking out Ben Webster, Lester Young, Johnny Hodges so that became an influence of mine, and Fletcher Henderson, so I was getting this like polar situation where I was listening to the big alto saxophonist at the time, Kenny Garrett, the 1990s early 2000s. Then I was getting really older musicians like Johnny Hodges and Lester.They were early influences for me, then it was Charlie Parker and then once I moved to college Ornette Coleman changed my life. Henry Threadgill, Benny Carter, those were my top three.

AAJ: Do you remember your first gig?

IW: Oh, I don't remember my first gig.I have no idea, it was probably at the Clef Club in Philadelphia with Lovett Hines as the director, that basically was a union house back in the day, and they have an education program now. It's deeply integrated into the scene so like my teachers were Ornette's last band, Mickey Roker, Trudy Pitts, just a super amazing cast of people to learn from and I think my first gig was probably through the Clef Club.

AAJ: You started writing your outstanding record, Omega around 2013-2015, were you thinking then that this was going to be an album?

IW: I had no idea it was going to be an album. I figured maybe I'd record it if it started to go well, but I didn't know it was going to be a record until I started playing it with the band I assembled about 4 or 5 years ago and we were like yea, maybe we should record this music. Those tunes had still been in rotation in the repertoire we had and we felt comfortable with that music. Most of the music was written in college but the second half of the album was pretty much written in high school.

AAJ: It was close to a six-year span between the beginning of the album, of what was to become the album, and the finished product. Did you find your style of writing, or your way of writing change over the years? Did you have a different mindset by the time you got to the end?

IW: Definitely, definitely! It was a slow and steady kind of change of repertoire, of how I wrote. It was a challenge, I guess especially for that older music, for it to still feel new and updated and it was kind of a last revival that we had. You know we really don't play that music that much anymore like the stuff I wrote in high school because it's pretty much like that was probably the best, the most alive we could make it. But you know it's interesting, you know music kind of changes over time, every two or three years there's a completely different writing style from before.

AAJ: Do you feel any kind of pressure with the success of Omega for the next one?

IW: No, no. I think it's because we have about five albums of repertoire that we've been playing for a long time. So, we're just on to the next one. I feel even more confident about the other music. You write differently every so often so I'm feeling very confident. But I guess I feel pressure just in a way, being on Blue Note, the legacy of Blue Note, the pressure just to be good. Knowing that Charlie Parker played this music I have to be good! That's where the pressure is, comes from me.

AAJ: Immanuel, thank you so much for taking the time to talk to us. We hope to see and hear you again soon.

IW: Oh, it was my pleasure, thank you.

Sax star Immanuel Wilkins: ‘Hands are a symbol of praise – but they are also lifted up at police’

At 24, the saxophonist is being hailed as one of the most promising jazz artists in the US – and his music, which explores faith and Black cultural vitality, is utopian in an America that isn’t

Immanuel Wilkins appears on a video call from his flat in Brooklyn, looking intently at the laptop perched on top of his Fender Rhodes keyboard. A column of light bounces off his forehead, and his red circular glasses magnify his eyes ever so slightly, making him look particularly absorbed in conversation.

We’re speaking before the release of The 7th Hand, the follow-up to his Blue Note Records debut (“an alto saxophonist whose playing is at once dazzlingly solid and perfectly lithe”, trilled the New York Times, as the album topped its best jazz of 2020 poll). He’s warm, effusive and a tad nervous. There’s a tantalising moment where he considers playing the Rhodes to explain a point, before getting tongue-tied, reconsidering and starting again. He’s only 24, and yet this new album – which examines spirituality in its artwork and contemporary dance in its videos – is mature and adventurous.

“At the core of Black existence, which is to say jazz music as well, is this idea of the in-between,” he says. “What makes jazz so great – it’s the solo, right? We play the head [the central theme], then we remix, we do our own thing in-between.”

He was born in Philadelphia, moving 20 minutes east to the suburb of Upper Darby for grade school: “I had grass. I had a playset in the backyard. I had the quintessential suburban kid life.” An only child, music was Wilkins’ way of making friends, via school bands and the historic Philadelphia Clef Club of Jazz and Performing Arts. Back home, his parents encouraged his music, perhaps living out their abandoned artistic dreams – he recently stumbled upon Archie Shepp and Benny Golson transcriptions compiled by his dad, who flirted with professional work as a trombonist and flautist.

Wilkins is a member of the Pentecostal Church of God in Christ, and began his musical career as resident pianist in the worship band at his local church. “I realised early on that there was a correlation between the atmosphere in the room and what I played. That was a turning point for me as a composer, player, everything. The idea of being responsible for how people consumed the spirit.”

He moved quickly through his early instruments: “I started on violin when I was three, and yeah, it didn’t really work out. Then I tried piano, and was not good. I tried singing. Yeah …” he says, chuckling. To convince his parents he was serious about the saxophone (and to fork out the money for one of his own), Wilkins returned home from church one Sunday and found he “could already play through one of the hymns [on it], like halfway, just.” They said yes.

Growing up, it was all about saxophonist Kenny Garrett (“third grade, fourth grade, fifth, sixth, seventh …”) and tips passed down from Branford Marsalis, whose band his unofficial “big brother” Justin Faulkner had recently joined on drums. Fellow Philly dweller Marshall Allen, leader and longtime member of the Sun Ra Arkestra, invited Wilkins aged 12 to the famed Arkestra House in Germantown, where the interstellar adventurers have lived since 1968. Wilkins got to sit next to Allen and experience his caustic sound. “Marshall used to tie a red rope around the bell of his saxophone, and I got a red wristband and put it round mine to be just like him.”

Why did he leave, then? “There’s some good Philly colleges, but I just wanted to go to Juilliard, I wanted to be around Wynton [Marsalis]” – the Pulitzer Prize-winning trumpeter and teacher who typifies august, classy jazz. “So I got up and left.” Marsalis pointed him towards Ornette Coleman’s Town Hall, 1962 album (“Emulating [Coleman’s] sound became a big part of what I do”), and the move to New York also brought him closer to forward-thinking pianist Jason Moran, who would later produce his first album. “I first met him at an Aretha Franklin concert when I was a child. Then, whenever he was in Philly, I went to all his gigs. When his drummer heard me in New York he said to Jason, ‘Hey, you know that cat who used to come to all our gigs? He doesn’t sound that bad, you should probably give him a chance.’” It was at Juilliard that Wilkins also met his quartet (Micah Thomas, Daryl Johns and Kweku Sumbry); there’s now an expectant buzz developing around all four of them.

Juilliard’s jazz department shares a floor with the dance and acting divisions, and Wilkins regrets not branching out across disciplines earlier (his mum was a dancer, and still dances in church on occasion). The 7th Hand makes up for lost time, a collective creative statement with roots in Black critical thought. The cover art, featuring Wilkins mid-immersion, remixes established ideas of southern Black baptism, placing women in the traditionally male leadership role. “I guess I’m trying to ask, who is really worthy of being baptised? Or, what is the established imagery around holiness that we see?” Meanwhile, the video Emanation/Don’t Break (featuring Farafina Kan Percussion Ensemble, and directed by Cauleen Smith, above) searches for the connections between Black dance styles – footwork, line-dancing and double-dutch – weaving yet more rich symbolism into Wilkins’ creation.

The album’s title comes from the Book of Ezekiel, where God commands Ezekiel to build an altar with the measurements of “six cubits and one handbreadth”.

“Hands are at the centre of spiritual life, they’re so powerful,” says Wilkins. “Those lifted hands in the church are some symbol of praise, right? But those same hands are also lifted up at the police.” His philosophy, and music, is utopian in an America that isn’t: “It’s about imagining a scenario that is so far beyond our reach, but that gets us to a certain truth that meets us farther than we are now.”

The album continues where Omega’s rhapsody on the totality of Black life left off: seven movements that flow into one another and culminate in the 27-minute immersive tapestry of Lift. Collective improvisation gradually subsumes the quartet as the record progresses; the group morphs into vessels through whom divine inspiration can flow freely. The sound is excitingly diverse, flowing quickly from harsh, driving dissonance towards gentler gospel tones, before exploding back into vibrant improvisation.

I ask Wilkins where he stands on the idea of spiritual jazz, a genre now bound up with cosmic psychedelia. “I like the phrase sacred music better,” he says. “Like, John Coltrane had A Love Supreme, and Duke Ellington had Come Sunday. I wonder if maybe this is my sacred music period.” Either way, as band members gradually peel themselves away from the group and embrace Wilkins’ idea of vesselhood with transcendent solos, his music always feels carried by spirit.