SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2022

VOLUME ELEVEN NUMBER ONE

RAPHAEL SAADIQ

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

JON BATISTE

(December 25-31)

MULGREW MILLER

(January 1- 7)

VALERIE COLEMAN

(January 8-14)

CHARNETT MOFFETT

(January 15-21)

AMYTHYST KIAH

(January 22-28)

JOHNATHAN BLAKE

(January 29--February 4)

AUDRA MCDONALD

(February 5-11)

IMMANUEL WILKINS

(February 12-18)

WYCLIFFE GORDON

(February 19-25)

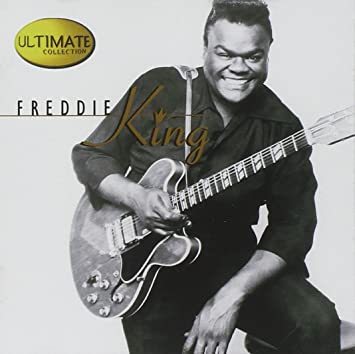

FREDDIE KING

(February 26-March 4)

DOREEN KETCHENS

(March 5-11)

TERRY POLLARD

(March 12-18)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/freddie-king-mn0000186734/biography

Freddie King

(1943-1976)

Artist Biography by Cub Koda

Guitarist Freddie King rode to fame in the early '60s with a spate of catchy instrumentals which became instant bandstand fodder for fellow bluesmen and white rock bands alike. Employing a more down-home (thumb and finger picks) approach to the B.B. King single-string style of playing, King enjoyed success on a variety of different record labels. Furthermore, he was one of the first bluesmen to employ a racially integrated group on-stage behind him. Influenced by Eddie Taylor, Jimmy Rogers, and Robert Jr. Lockwood, King went on to influence the likes of Eric Clapton, Mick Taylor, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and Lonnie Mack, among many others.

Freddie King (who was originally billed as "Freddy" early in his career) was born and raised in Gilmer, TX, where he learned how to play guitar as a child; his mother and uncle taught him the instrument. Initially, King played rural acoustic blues, in the vein of Lightin' Hopkins. By the time he was a teenager, he had grown to love the rough, electrified sounds of Chicago blues. In 1950, when he was 16 years old, his family moved to Chicago, where he began frequenting local blues clubs, listening to musicians like Muddy Waters, Jimmy Rogers, Robert Jr. Lockwood, Little Walter, and Eddie Taylor. Soon, the young guitarist formed his own band, the Every Hour Blues Boys, and was performing himself.

In the mid-'50s, King began playing on sessions for Parrott and Chess Records, as well as playing with Earlee Payton's Blues Cats and the Little Sonny Cooper Band. Freddie King didn't cut his own record until 1957, when he recorded "Country Boy" for the small independent label El-Bee. The single failed to gain much attention.

Three years later, King

signed with Federal Records, a subsidiary of King Records, and recorded

his first single for the label, "You've Got to Love Her With a

Feeling," in August of 1960. The single appeared the following month and

became a minor hit, scraping the bottom of the pop charts in early

1961. "You've Got to Love Her With Feeling" was followed by "Hide Away,"

the song that would become Freddie King's signature tune and most influential recording. "Hide Away" was adapted by King and Magic Sam from a Hound Dog Taylor

instrumental and named after one of the most popular bars in Chicago.

The single was released as the B-side of "I Love the Woman" (his singles

featured a vocal A-side and an instrumental B-side) in the fall of 1961

and it became a major hit, reaching number five on the R&B charts

and number 29 on the pop charts. Throughout the '60s, "Hide Away" was

one of the necessary songs blues and rock & roll bar bands across

America and England had to play during their gigs.

King's first album, Freddy King Sings, appeared in 1961, and it was followed later that year by Let's Hide Away and Dance Away With Freddy King: Strictly Instrumental. Throughout 1961, he turned out a series of instrumentals -- including "San-Ho-Zay," "The Stumble," and "I'm Tore Down" -- which became blues classics; everyone from Magic Sam and Stevie Ray Vaughan to Dave Edmunds and Peter Green covered King's material. "Lonesome Whistle Blues," "San-Ho-Zay," and "I'm Tore Down" all became Top Ten R&B hits that year.

Freddie King continued to record for King Records until 1968, with a second instrumental album (Freddy King Gives You a Bonanza of Instrumentals) appearing in 1965, although none of his singles became hits. Nevertheless, his influence was heard throughout blues and rock guitarists throughout the '60s -- Eric Clapton made "Hide Away" his showcase number in 1965. King signed with Atlantic/Cotillion in late 1968, releasing Freddie King Is a Blues Masters the following year and My Feeling for the Blues in 1970; both collections were produced by King Curtis. After their release, Freddie King and Atlantic/Cotillion parted ways.

King landed a new record contract with Leon Russell's Shelter Records early in 1970. King recorded three albums for Shelter in the early '70s, all of which sold well. In addition to respectable sales, his concerts were also quite popular with both blues and rock audiences. In 1974, he signed a contract with RSO Records -- which was also Eric Clapton's record label -- and he released Burglar, which was produced and recorded with Clapton. Following the release of Burglar, King toured America, Europe, and Australia. In 1975, he released his second RSO album, Larger Than Life.

Throughout 1976, Freddie King toured America, even though his health was beginning to decline. On December 29, 1976, King died of heart failure. Although his passing was premature -- he was only 42 years old -- Freddie King's influence could still be heard in blues and rock guitarists decades after his death.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freddie_King

Freddie King

Freddie King (September 3, 1934 – December 28, 1976) was an American blues guitarist, singer and songwriter. He is considered one of the "Three Kings of the Blues Guitar" (along with Albert King and B.B. King, none of whom are blood related).[1][2] Mostly known for his soulful and powerful voice and distinctive guitar playing, King had a major influence on electric blues music and on many later blues guitarists.

Born in Gilmer, Texas, King became acquainted with the guitar at the age of six. He started learning the guitar from his mother and his uncle. King moved to Chicago when he was a teenager; there he formed his first band the Every Hour Blues Boys with guitarist Jimmie Lee Robinson and drummer Frank "Sonny" Scott. As he was repeatedly being rejected by Chess Records, he got signed to Federal Records, and got his break with single "Have You Ever Loved a Woman" and instrumental "Hide Away", which reached number five on the Billboard magazine's rhythm and blues chart in 1961. It later became a blues standard. King based his guitar style on Texas blues and Chicago blues influences. The album Freddy King Sings showcased his singing talents and included the record chart hits "You've Got to Love Her with a Feeling" and "I'm Tore Down".[3] He later became involved with more rhythm and blues and rock oriented producers and was one of the first bluesmen to have a multiracial backing band at live performances.[4]

He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame by ZZ Top in 2012 and into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1982. His instrumental "Hide Away" was included in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's list of "500 Songs that Shaped Rock".[5] He was ranked 25th in the Rolling Stone magazine's 2003 edition of "100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time"[6] and 15th in the 2011 edition.

Biography

1934–1952: Early life

According to his birth certificate he was named Fred King, and his parents were Ella Mae King and J. T. Christian.[7] When Freddie was six years old, his mother and his uncle began teaching him to play the guitar. In autumn 1949, he and his family moved from Dallas to the South Side of Chicago.[7]

In 1952 King started working in a steel mill. In the same year he married another Texas native, Jessie Burnett. They had seven children.[7]

1952–1959: Move to Chicago and early works

Almost as soon as he had moved to Chicago, King started sneaking into South Side nightclubs, where he heard blues performed by Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, T-Bone Walker, Elmore James, and Sonny Boy Williamson. King formed his first band, the Every Hour Blues Boys, with the guitarist Jimmie Lee Robinson and the drummer Frank "Sonny" Scott. In 1952, while employed at a steel mill, the eighteen-year-old King occasionally worked as a sideman with such bands as the Little Sonny Cooper Band and Earl Payton's Blues Cats. In 1953 he recorded with the latter for Parrot Records, but these recordings were never released. As the 1950s progressed, King played with several of Muddy Waters's sidemen and other Chicago mainstays, including the guitarists Jimmy Rogers, Robert Lockwood Jr., Eddie Taylor, and Hound Dog Taylor; the bassist Willie Dixon; the pianist Memphis Slim; and the harmonicist Little Walter.

In 1956 he cut his first record as a leader, for El-Bee Records. The A-side was "Country Boy", a duet with Margaret Whitfield.[8] The B-side was a King vocal. Both tracks feature the guitar of Robert Lockwood, Jr., who during these years was also adding rhythm backing and fills to Little Walter's records.[7]

King was repeatedly rejected in auditions for the South Side's Chess Records, the premier blues label, which was the home of Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, and Little Walter. The complaint was that King sang too much like B.B. King. A newer blues scene, lively with nightclubs and upstart record companies, was burgeoning on the West Side, though. The bassist and producer Willie Dixon, during a period of estrangement from Chess in the late 1950s, asked King to come to Cobra Records for a session, but the results have never been heard. Meanwhile, King established himself as perhaps the biggest musical force on the West Side. He played along with Magic Sam and reputedly played backing guitar, uncredited, on some of Sam's tracks for Mel London's Chief and Age labels,[7] though King does not stand out on them.

1959–1962: Federal Records

In 1959 King got to know Sonny Thompson, a pianist, producer, and A&R man for Cincinnati's King Records. King Records' owner, Syd Nathan, signed King to the subsidiary Federal Records in 1960. King recorded his debut single for the label on August 26, 1960: "Have You Ever Loved a Woman" backed with "You've Got to Love Her with a Feeling" (again credited as "Freddy" King). From the same recording session at the King Studios in Cincinnati, Ohio, King cut the instrumental "Hide Away", which the next year reached number five on the R&B chart and number 29 on the Pop chart, an unprecedented accomplishment for a blues instrumental at a time when the genre was still largely unknown to white audiences. It was originally released as the B-side of "I Love the Woman". "Hide Away" was King's melange of a theme by Hound Dog Taylor and parts by others, such as "The Walk", by Jimmy McCracklin, and "Peter Gunn", as credited by King. The title of the tune refers to Mel's Hide Away Lounge, a popular blues club on the West Side of Chicago.[9] Willie Dixon later claimed that he had recorded King performing "Hide Away" for Cobra Records in the late 1950s, but such a version has never surfaced.[10] "Hide Away" became a blues standard.

After their success with "Hide Away", King and Thompson recorded thirty instrumentals, including "The Stumble", "Just Pickin'", "Sen-Sa-Shun", "Side Tracked", "San-Ho-Zay", "High Rise", and "The Sad Nite Owl".[11][12] They recorded vocal tracks throughout this period but often released the tunes as instrumentals on albums.

During the Federal period, King toured with many notable R&B artists of the day, including Sam Cooke, Jackie Wilson, and James Brown.

1966–1974: Cotillion, Shelter, RSO Records

King's contract with Federal expired in 1966, and his first overseas tour followed in 1967. His availability was noticed by the producer and saxophonist King Curtis, who had recorded a cover of "Hide Away", with Cornell Dupree on guitar, in 1962. Curtis signed King to Atlantic in 1968, which resulted in two LPs, Freddie King Is a Blues Master (1969) and My Feeling for the Blues (1970), produced by Curtis for the Atlantic subsidiary Cotillion Records.[13]

In 1969 King hired Jack Calmes as his manager, who secured him an appearance at the 1969 Texas Pop Festival, alongside Led Zeppelin and others,[14] and this led to King's signing a recording contract with Shelter Records, a new label established by the rock pianist Leon Russell and the record producer Denny Cordell and recorded at their studio, The Church Studio in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The company treated King as an important artist, flying him to Chicago to the former Chess studios to record the album Getting Ready and providing a lineup of top session musicians, including Russell.[15] Three albums were made during this period, including blues classics and new songs, such as "Going Down", written by Don Nix.[16]

King performed alongside the big rock acts of the day, such as Eric Clapton[17] and Grand Funk Railroad (whose song "We're an American Band" mentions King in its lyrics), and for a young, mainly white audience, along with the white tour drummer Gary Carnes, for three years, before signing with RSO Records. In 1974 he recorded Burglar, for which Tom Dowd produced the track "Sugar Sweet" at Criteria Studios in Miami, with the guitarists Clapton and George Terry, the drummer Jamie Oldaker and the bassist Carl Radle. Mike Vernon produced the other tracks.[18] Vernon also produced a second album for King, Larger than Life,[19] for the same label. Vernon brought in other notable musicians for both albums, such as Bobby Tench of the Jeff Beck Group, to complement King.[20]

Death

Nearly constant touring took its toll on King—he was on the road almost 300 days out of the year. In 1976 he began suffering from stomach ulcers. His health quickly deteriorated, and he died on December 28 of complications from this illness and acute pancreatitis, at the age of 42.

According to those who knew him, King's untimely death was due to stress, a legendary "hard-partying lifestyle",[21] and a poor diet of consuming Bloody Marys because as he told a journalist, "they've got food in them."[22]

Musical style

King had an intuitive style, often creating guitar parts with vocal nuances.[23] He achieved this by using the open-string sound associated with Texas blues and the raw, screaming tones of West Side, Chicago blues. King's combination of the Texas and Chicago sounds gave his music a more contemporary feel than that of many Chicago bands who were still performing 1950s-style music, and he befriended the younger generation of blues musicians. In his early career he played a solid-body gold-top Gibson Les Paul with P-90 pickups.[24] He later played several slimline semi-hollow body Gibson electric guitars, including an ES-335, ES-345, and ES-355.[24] He used a plastic thumb pick and a metal index-finger pick.[24]

Legacy

By proclamation of the governor of Texas, Ann Richards, September 3, 1993, was declared Freddie King Day, an honor reserved for Texas legends, such as Bob Wills and Buddy Holly.[25] He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2012,[26] and placed 15th in Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 100 greatest guitarists of all time.[27]

Several of King's early 1960s instrumentals found their way into the repertoire of surf music bands:[28] "Those instrumental hits Freddy King had – 'Hideaway', 'San-Ho-Zay', 'The Stumble' – [t]he way white kids were relating to it was like surf guitar in a way; instrumental music that you could dance to."[29] One band that mixed R&B and surf instrumentals occasionally included Jerry Garcia.[29] He later explained: "When I started playing electric guitar the second time, with the Warlocks, it was a Freddie King album that I got almost all my ideas off of, his phrasing really. That first one, Here's Freddie King, later it came out as Freddie King Plays Surfin' Music or something like that, it has 'San-Ho-Zay' on it and 'Sensation" and all those instrumentals"[30] (King's 1961 instrumental album, Let's Hide Away and Dance Away with Freddy King, was retitled Freddy King Goes Surfin' for a 1963 re-release).

According to music critic Cub Koda, King has influenced guitarists such as Eric Clapton, Mick Taylor, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and Lonnie Mack.[4] In Michael Corcoran's words, King "merged the most vibrant characteristics of both [Chicago and Texas] regional styles and became the biggest guitar hero of the mid-sixties British blues revivalists, who included Eric Clapton, Savoy Brown, Chicken Shack, and Peter Green-era Fleetwood Mac".[31] Clapton said in 1985 that King's 1961 song "I Love the Woman" was "the first time I heard that electric lead-guitar style, with the bent notes ... [it] started me on my path." He later added in an interview with Dan Forte of Guitar World that King's guitar playing on his rendition of "I Got a Woman": "That just sent me into a complete kind of ecstasy, and it scared the shit of me. I'd never heard anything like it, and I thought I'd never get anywhere near it. And I know now that I never will, but it was what immediately made me want to carry on."[This quote needs a citation] As Rolling Stone later wrote, "Clapton shared his love of King with fellow British guitar heroes Peter Green, Jeff Beck and Mick Taylor, all of whom were profoundly influenced by King's sharpened-treble tone and curt melodic hooks on iconic singles such as 'The Stumble,' 'I'm Tore Down' and 'Someday, After Awhile.'"[27]

King was among many pioneering African-American blues musicians to embrace the British blues scene and tour its club circuit in the late 1960s.[32] Robert Christgau credited King's embrace of Britain with creating his renown as a pioneer of electric blues guitar.[33] In Gary Graff's MusicHound Rock (1996), the entry on King states: "Although his reputation rests with his guitar, King also sang with an underrated, powerful style. His lasting influence has insured Freddie King's recognition as one of the great postwar blues masters."[34]

Appraisal of recording work

Recommending what albums of King's music to hear, MusicHound Rock cited the 1993 Rhino compilation The Best of Freddie King, for focusing on "the fruitful abundance" of his recordings for King Records (1961–66), and the 1995 Black Top CD Live at the Electric Ballroom, 1974, for its "blasting, ripping concert" recording along with "a rare pair of acoustic" performances; Freddie King Is a Blues Master (1969) and My Feeling for the Blues (1970) were named records to avoid, as they "both suffer from thin accompaniment, too little guitar and reedy vocals".[34] John Swenson, writing in The Rolling Stone Jazz & Blues Guide (1999), also recommended the Electric Ballroom recording, along with "Home Cooking's Live at the Texas Opry House (documenting a 1976 show in Houston)", saying they are "the best antidotes to King's lackluster studio work from these years".[35]

In his only review of a King album, The Best of Freddie King (1975) by Shelter Records, Christgau wrote in Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981) that the 1971–73 recordings are "a bunch of Leon Russell and Don Nix boogies, [King's] voice blurred, his guitar all fake and roll." He added that, while the guitarist had recorded some "acute R&B" singles early in his career, he later "coast[ed] for years".[33] However, in a review of King's 1974 album Burglar for AllMusic, Joe Viglione called it "entertaining and concise" and believed the album "stands as a solid representation of an important musician which is as enjoyable as it is historic".[36]

Discography

Studio albums

List of studio albums with year, title, record label, and chart peak Year Title Label

(Cat. No.) Peak chart

position

R&B US

1961 Freddy King Sings King

(762)

Let's Hide Away and Dance Away with Freddy King King

(773)

1962 Boy – Girl – Boy

Freddy King, Lulu Reed & Sonny Thompson King

(777)

1963 Bossa Nova and Blues King

(821)

Freddy King Goes Surfin' King

(856)

1965 Gives You a Bonanza of Instrumentals King

(928)

1969 Freddie King Is a Blues Master Cotillion

(SD 9004)

1970 My Feeling for the Blues Cotillion

(SD 9016)

1971 Getting Ready... Shelter

(SW8905)

1972 Texas Cannonball Shelter

(SW8913)

1973 Woman Across the River Shelter

(SW8921) 54 158

1974 Burglar RSO

(SO4803) 53

1975 Larger Than Life RSO

(SO4811)

Selected compilation albums

List of selected compilation albums with year, title, label, and chart peak Year Title Label

(Cat. No.) Peak chart

position

R&B US

1966 Vocals and Instrumentals King

(964)

1975 The Best of Freddie King Shelter

(SR-2140)

1977 Freddie King 1934–1976 RSO

(RS-1-3025)

1986 Just Pickin' Modern Blues

(MB2LP-721)

1992 Blues Guitar Hero: The Influential Early Sessions Ace

(CDCHD 454)

1993 Hide Away: The Best of Freddie King Rhino

(R2 71510)

2000 The Best of Freddie King: The Shelter Records Years The Right Stuff

(72435-27245-2-9)

2002 Blues Guitar Hero Volume 2 Ace

(CDCHD 861)

2009 Taking Care of Business Bear Family

(BCD 16979 GK)

2010 Texas Flyer 1974–1976 Bear Family

(BCD 16778 EK)

Charting singles

List of singles with year, title, label, and chart peak Year Title Label

(Cat. No.) Peak chart

position

R&B[37] US[37]

1956 "Country Boy" / "That's What You Think" El-Bee

(157)

1960 "Have You Ever Loved a Woman" Federal

(12384)

/ "You've Got to Love Her with a Feeling" Federal

(12384)

92

1961 "Hide Away" (i) / "I Love the Woman" Federal

(12401) 5 29

"Lonesome Whistle Blues" /

"It's Too Bad Things Are Going So Tough" Federal

(12415) 8 88

"San-Ho-Zay" (i) Federal

(12428) 4 47

/ "See See Baby" Federal

(12428) 21

"I'm Tore Down" / "Sen-Sa-Shun" (i) Federal

(12432) 5

"Christmas Tears" / "I Hear Jingle Bells" Federal

(12439) 28

Bibliography

- Busby, Mark (2004). The Southwest. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32805-3.

- Clapton, Eric (2007). Clapton: The Autobiography. Broadway Books. Digitized September 4, 2008. ISBN 978-0-385-51851-2.

- Corcoran, Michael (2005). All Over the Map: True Heroes of Texas Music. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70976-8.

- Forte, Dan (2000). "Freddie King". In Rollin' and Tumblin': The Postwar Blues Guitarists. Jas Obrecht, ed. San Francisco: Miller Freeman Books. pp. 275–280. ISBN 0-87930-613-0, 978-0-87930-613-7.

- Hardy, Phil; Laing, Dave; Stephen, Barnard; Perretta, Don (1988). Encyclopedia of Rock. 2nd ed., rev. Schirmer Books. Digitized December 21, 2006. ISBN 978-0-02-919562-8.

- Koster, Rick (2000). Texas Music. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-25425-4.

- Lawrence, Robb (2008). The Early Years of the Les Paul Legacy 1915–1963. Hal Leonard. ISBN 978-0-634-04861-6.

- O'Neal, Jim; Van Singel, Amy (2002). The Voice of the Blues: Classic Interviews from Living Blues Magazine. 10th ed. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-93653-8.

- Pruter, Robert (1992). Chicago Soul. 5th ed., reprint. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06259-9.

- Whitburn, Joel (1988). Joel Whitburn's Top R&B Singles 1942-1988. Record Research, Incorporated. ISBN 0898200695.

External links

- Official website

- Freddie King at AllMusic

- Freddie King discography at Discogs

20 articles ARTICLES IN LIBRARYLive Review by Guy Stevens, Record Mirror, 4 April 1964 ON STAGE WITH THE R&B LEGENDS ... Junior Walker & the Allstars, Freddie King, Jimmy Cliff: Saville Theatre, London Live Review by Norman Jopling, Record Mirror, 21 October 1967 IT WAS A 'soul show' at the Saville last Sunday, in the very widest sense of the term. Jimmy Cliff started off, and when he ... Junior Walker and The All-Stars, Jimmy Cliff, Freddie King: Saville Theatre, London Live Review by Chris Welch, Melody Maker, 21 October 1967 GREAT THUNDERING jackanapes! An all-round good show at the Saville: No goofs, no curtains falling down, great music, a nice audience and even, wonder of ... Electric Flag; Freddie King; Buddy Guy: Fillmore West, San Francisco CA Live Review by Philip Elwood, The San Francisco Examiner, 10 July 1968 Lots of Room at Fillmore West ... Review by uncredited writer, Hit Parader, March 1969 New Albums from Jeff Beck, Freddie King et al ... Freddie King: Freddie Takes a British Cold Back Home Interview by Max Jones, Melody Maker, 22 March 1969 "I DIDN'T have it tonight," said Freddie King after a hard workout at Art Saunders' Wood Green club on Tuesday last week. ... Payin' Some Dues — Blues at Ann Arbor Live Review by Miller Francis jr., The Great Speckled Bird, 18 August 1969 "I'd like for them to hear the real things. I don't think yet that most of the white people like my music because it's blues. I ... Freddie King, Juke Boy Bonner, Jo-Ann Kelly, John Dummer: 100 Club, London Live Review by Max Jones, Melody Maker, 15 November 1969 TUESDAY OF last week was Big Blues Night at London's 100 Club where a large, good-humoured crowd was afforded almost non-stop entertainment by the Killing ... Freddie King: Ash Grove, Los Angeles Live Review by David Rensin, The Valley State Daily Sundial, 18 December 1970 No one matches F. King ... Freddie King, Juke Boy Bonner: The Ash Grove, Los Angeles CA Live Review by John Mendelssohn, Los Angeles Times, 2 July 1971 Freddie King Performs on Ash Grove Stage ... B.B. King and Freddie King: Kings Of The Blues Interview by Richard Green, New Musical Express, 11 December 1971 Two bluesmen who have become living legends talk about their careers and the state of the blues today. And B.B. King and Freddie King both ... Grand Funk Railroad, Freddie King: Madison Square Garden, New York NY Live Review by Ian Dove, The New York Times, 25 December 1972 Grand Funk Railroad Steams Into the Garden at Full Throttle ... Freddie King: The Cannonball Blows Into Town Interview by Jerry Gilbert, Sounds, 28 July 1973 WHEN THE Texas Cannonball blows into town it's quite an event, and when he's only in for a couple of days then everybody wants to ... Freddie King: Roundhouse, London Live Review by Philip Norman, The Times, 2 December 1974 AN IMPRESSIVE crowd awaited Freddie King at the Roundhouse last night, wound about its cylindrical structure or massed on its inhospitable boards for several hours ... Review by Charles Shaar Murray, New Musical Express, 3 May 1975 If you're a living blues master, are you better off dead? ... Freddie King: New Victoria, London Live Review by Chas de Whalley, New Musical Express, 1 November 1975 A NIGHT TO remember. "It's Blues time, ladies and gentlemen. Please welcome Freddie King." ... The Crystal Palace Garden Party: E.C. Was Here…But Coryell Was Better Live Review by Chris Welch, Melody Maker, 7 August 1976 THERE IS an aura of faded grace and decaying dignity about Crystal Palace, set upon the heights of Norwood in South London. Perhaps it stems ... Freddie King: King of rhythm 'n' blues Obituary by Max Jones, Melody Maker, 15 January 1977 SOME BLUESMEN are pure country artists, folk musicians really, others are traditional-mixed-with-Chicago, others West Coast, jazz-blues Memphis stylists soul singers and what-have-you. ... Freddie King and Howard Tate are the Soul of Gospel and Blues Report by Kirk Silsbee, Pasadena Weekly, 16 February 2006 TOO OFTEN we're reminded that soul – the fundament of black gospel and blues—is fast slipping away from us. Losing Wilson Pickett and Lou Rawls in ... Retrospective by Ted Drozdowski, Guitar World, August 2012 NOTE: This is an expanded version of a piece that was in the Rock 'n' Roll Hall of Fame's induction program in 2012: the lengthier ... back to LIBRARY |

|---|

King, Freddie (1934–1976)

by Amy Van Beveren and Laurie E. Jasinski

Type: BiographyPublished: February 1, 1995

Updated: August 30, 2015

King, Freddie (1934–1976).Freddie King, blues musician, was born Freddie Christian in Gilmer, Texas, on September 3, 1934. He was the son of J. T. Christian and Ella Mae (or May) King. At the age of six he began playing guitar with his mother and an uncle, Leon King. As a youth he purchased a Roger's acoustic guitar with money he had earned picking cotton.

He moved to Chicago with his family in 1949. At the age of sixteen he snuck into a Chicago blues club and sat in with the house band, which included Howlin' Wolf. King developed his style under the influence of Lightnin' Hopkins, T-Bone Walker, B. B. King (not a relative), Louis Jordan, and others. He married Jessie Burnett by 1952. By day he worked in a steel mill, and he played shows at night. King formed his own band, the Every Hour Blues Boys, which included Eddie Taylor, Jimmy Rogers, Jimmy Lee Robinson, and Sonny Scott. He recorded songs on the Parrot Label in 1953.

During the 1950s King played local clubs and also worked with the Sonny Cooper Band and Earlee Payton's Blues Cats. In 1960 he signed with King/Federal, a label that had other impressive artists such as pianist Sonny Thompson who collaborated with King on a number of recordings. Some of King's classic songs were "Have You Ever Loved a Woman," "Woman Across the River," and "Hide Away," which became a major crossover hit from blues to pop.

King toured the United States and appeared in concert halls, night clubs, and at jazz and blues festivals. Weary of her husband's brutal recording and touring schedule, King's wife Jessie and their six children moved to Dallas in 1962. King left Chicago and moved to Dallas and back to his family in spring 1963. There he worked on perfecting his own soulful vocal style. In 1966 he made a series of appearances on The !!!! Beat, a weekley rhythm-and-blues Dallas television program whose house band was headed by Clarence "Gatemouth" Brown.

He signed with Cotillion in 1968 and recorded two albums, Freddie King is a Blues Master and My Feeling for the Blues. That same year he toured England. In 1969 he was one of the headlining acts at the Texas International Pop Festival. Like many blues artists in the late 1960s and early 1970s, King had close ties to rock-and-roll. Musicians such as Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck recorded his songs, and King toured with Clapton in the mid-1970s. In 1971 he recorded the first major live album ever made in Austin at Armadillo World Headquarters, known sometimes as "the House That Freddie King Built." He regularly played at the club and returned periodically for fund-raisers. His recordings with Shelter Records brought him recognition throughout the state as a "top notch Texas bluesman."

King died on December 28, 1976, of bleeding ulcers and pancreatitis at the age of forty-two. He was buried in Hillcrest Memorial Park, Dallas. In 1982 he was inducted into the Blues Foundation's Blues Hall of Fame. Texas Gov. Ann Richards declared September 3, 1993, as "Freddie King Day," and in 2003 Rolling Stone ranked King twenty-fifth among its list of the 100 greatest guitarists. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2012.

http://www.acidlogic.com/im_freddie_king.htm

by

Wil Forbis

About twelve years ago I was wandering around Beale Street in Memphis, Tennessee, an area often called the "birthplace of the blues." Given such a reverent title, I was expecting to find an awe inspiring musical wonderland populated with a never ending parade of skilled musicians. But it was about 3 in the afternoon and the place was quiet - dead as ghost town. I was strolling along and I came across an open lot. In the middle of the lot was this old, frail black guy sitting atop an open gazebo. He was starting to tune up an electric guitar that he had hooked up to powerful sound system with giant speakers that hung from wire above him.

"This is great!" I thought to myself. "Here I am in the birthplace of my favorite form of music and I've stumbled across some forlorn master of the blues arts." I felt like Alan Lomax discovering Leadbelly, or Mick Jagger discovering Stevie Ray Vaughn, or adult filmmaker Doris Wishman discovering the mellon breasted Chesty Morgan. I was, no doubt, about to uncover a great talent. I waited for the guy to finish tuning up and start bedazzling me with his musical expertise.

And I waited. and I waited. But all the stupid fuck did was sit there tuning the guitar for twenty minutes, babbling on apologies like, "Hold on there young fellah, I'll be done in a second, Jus' got to get it jus' right. hold on." Eventually he did get it tuned, and then proceeded to detune the instrument as if he were completely oblivious to what a tuned guitar sounded like. (Years later, I think he became the guitar tech for Sleater Kinney.) Finally, he started to play a song, and it was awful. (He must've also became the main songwriter for Sleater Kinney.) All my hopes of discovering the next blues genius were dashed and I thought to myself, "I sure hope this guy isn't Freddie King."

Did I really think that? Well, no. But I've been trying to get that story off my chest for some time, and I figured there'd be no better place to do it than in an article about Freddie King, the quintessential yet vastly underrated master of blues guitar. In actuality, there were a quite few things that made it very clear that this decrepit old bastard wasn't my favorite blues guitarist.

1) Freddie was kind of fat, whereas this guy was skinny

2) Freddie was a great guitar player, whereas this guy sucked.

3) Freddie King was dead. whereas this guy should have been.

As you probably know, in the blues game, "King" is a recurring family name. The most successful bluesman of all time is B.B. King, a cat who's still alive knocking out albums and doing ads for diabetes monitors. There was also Albert King, who, until his death in the 90's had great success with songs like "The Sky is Crying" and "Born Under a Bad Sign" as well as being an artistic father figure for a young Stevie Ray Vaughn. I was particularly impressed with Earl King when I caught his show in Hollywood about 15 years ago. Jimmy King was making the scene over through the course of the nineties until his recent death at the age of 37. (Jimmy toured extensively with Albert King, and once, while I was stopped at the Canadian border, both musicians came in and I had the chance to have a long conversation with Jimmy - but that's another story.)

You might wonder how and why so many blues musicians could be named "King" but it's worth noting that none of these guys actually had "King" as their birth name. (Sorta like how none of the Ramones were born to a "Mr. And Mrs. Ramone.") And despite similarities in their signatures, each of these players had a pretty distinctive style. B.B., despite his success, has my least favorite King sound, a somewhat chirpy collection of clichés he pumps out of his guitar, "Lucille." Albert had a great, stinging style that was absorbed by most of the white players like Eric Clapton and Mick Taylor. I remember Earl being very aggressive sounding and Jimmy was something of an offshoot of Albert, combining classic licks with a more modern tone.

But Freddie. Freddie was something else.

There were, in my opinion, really two Freddie Kings to take note of. The first Freddie King can be defined by the mostly instrumental material he recorded on the King/Federal label during the first half of the sixties. The second Freddie can be found on the 70's recordings on the Cotillion, Shelter, and RSO releases which feature quite a bit of Freddie singing as well as playing guitarFreddie in the 60's

Early Freddie sounds pretty dated today, but for the era he was really

adding a modern sound to the style of blues. His first instrumental hit,

"Hideaway," is an uptempo, playful number. (Note: you can hear several

samples of some of the tunes I mention by going here:

http://www.cduniverse.com/productinfo.asp?style=MUSIC&pid=2850825&cart=132460080)

Freddie starts out with a now classic opening melody, and then cycles the 12 bars blues through a variety of mutations: an accented funk groove, a Chuck Berry-ish double-stop* frenzy, and a spy music section lifted from the theme to "Peter Gunn." The song also provides an example of Freddie's talent of creating extremely catchy guitar riffs that could be mistaken for Beatles melodies were they placed in a vocal context.

*Double Stop: playing two notes at the same time, similar to Check Berry's opening solo on "Johnny B Goode"

Though "Hideaway" is probably Freddie's best-known song of that era, I've always placed a lesser-known tune, "San-Ho-Zay" (San Jose - get it?!) as my favorite. The song begins with the rhythm section playing a blues/funk riff that's since become a cliché, but still grabs me every time. Freddie comes in with a series of fairly restrained guitar licks, but uses each turn of the chord progression to continually push things up a notch, finally ending on a studio fade. "San-Ho-Zay" also shows off another common Freddie King technique - that of taking a base melody and twisting and shaping it with each iteration. (Similar to the "variations on a theme" concept so popular in classical music.)

Another piece in the "San-Ho-Zay" vein is "The Stumble." Named after its rhythm, which is an illustration of the standard, "stumbling" blues shuffle, this tune features more of Freddie's singable melodies with a blues break reminiscent of the culmination of Zeppelin's "Whole Lotta Love."

What's not often mentioned about this early King material is how similar it is to the surf music of bands like the Ventures or Dick Dale. Freddie didn't use the heavily reverbed guitar tone of such artists, but he did have the same goal in mind, which was to start out with a standard melody and then keep in interesting by subtly changing the rhythm and feel of the song. No doubt Freddie and the surf bands were at least somewhat familiar with each other and influences may have rubbed off.

In the latter half of the sixties, the blues, as championed by such white rock and roll groups like the Rolling Stones, Cream, and the Jeff Beck Group, were hitting the big time, and a lot of the Black artists who'd defined the style were experiencing a resurgence. Clapton and Jeff Beck were raving about guys like Muddy Waters, Albert King, and our man Freddie, which gave Black players the chance to enjoy the spotlight and expand their reputation beyond black audiences and (to borrow a phrase) "white negroes." The fact that players like Freddie and Albert had to ride the coattails of white musicians could be said to insinuate blatant racism: white audiences weren't willing to listen to rhythm and blues when it was played on mostly black "race records," but ate it up when served by long haired honkeys such as Clapton, Beck, Peter Green, or Jimmy Page. Of course there's a lot of truth to this argument, but I've always found it unnecessarily simplistic. A more honest way of looking at it is to say that it wasn't racism (e.g. fear or hatred of another race) that kept the early rock fans from seeking out black artists as much as it was a lack of knowledge and general awareness of black culture. Segregation was still alive, and the odds of a young white kid, crossing over to the black side of town and walking into a scary looking R&B club were slim, but not demonstrative of said youth being racist. (Hell, when's the last time you walked into a ghetto rap club, cracker?) And once the white artists did break open the door for earlier black musicians, white fans wasted no time becoming intimately familiar with the creators of the genre, to the degree that some partook to almost completely undiscerning worship of musicians simply because they were black. Just as the "punk" packaging of Nirvana caused fans to go back to earlier punk bands like the Ramones or the Meat Puppets, the packaging of electric blues via players like Clapton encouraged fans to return to the roots. (In the late 90's, the blues, which had become "old man's music," was repackaged via longhaired pretty boys like Kenny Wayne Shepard and Johnny Lang and successfully resold to the younger generation.)

Freddie in the 70'sHmmm. not sure how I ended up on that tangent. However, it leads us up to the 70's where King, burgeoned by the success the late 60's blues explosion had granted him, moved away from instrumentals towards vocal numbers. The epitome of this would be, in my opinion, (course, everything in this article is "in my opinion.") his recordings for Shelter records, a label partly owned by rock pianist Leon Russell. Leon took an active interest in Freddie's output for the label, writing songs for him and playing on many of the recordings. The Shelter recordings are a point of contention amongst King fans. Personally, I think they're great, but some argue that they're overproduced and featured Freddie playing on material he wasn't comfortable with. What can I say? There's two sides to every story: my side and the wrong side.

There are a lot of reasons I love this period of King's music. For one thing, many of the songs step away from the standard 12 bar blues pattern and offer some variety in composition. One of my favorites, "Palace of the King," is more of an R&B number, replete with female background vocals. "Living on the Highway," a tribute to Howling Wolf, has a pumping "A" section before modulating down for a short solo from Freddie. "Me and My Guitar" returns to the 12 bar formula but features a pumping base riff, while Freddie boasts about making his guitar sing, "just like my woman should."

In addition, I think Freddie's guitar tone (or at least the technology recording it) improved a bit on the Shelter records. The 60's instrumentals had a sharp, high-pitched quality, but the 70's recordings have more mid range and beef to the guitar solos.

While a lot of blues artist found their careers waning in the 70's, Freddie held his own. The Shelter records kept his profile up and he did a tour with Eric Clapton. Unfortunately, he died in 1976 at the young age of 42 from heart failure. While probably the least popular of the "triumvirate of Kings" (including B.B and Albert) his songs are still oft played in blues halls and his recordings continue to be pressed and sold to the public.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Wil Forbis is the pen name shared by such noted authors as James Ellroy, Katie Roiphe, and Jim Thompson. E-mail him, I mean, them, at acidlogic@hotmail.com

https://www.vinylmeplease.com/blogs/magazine/freddie-king-liner-notes

Freddie King Played an Eternal Game

How ‘My Feeling for the Blues’ started an echo across blues and rock for generations

by Andrew WinistorfOut of the Three "Kings" of the Blues, Freddie King is often mentioned behind Albert and B.B., the third wheel like Theodore, Moe or the guy who brought Christ myrrh. And that makes some sense: Freddie died young — at 42, of a combination of stomach ulcers and pancreatitis — and his recording career is the shortest of the Three Kings, mainly lasting the 15 years between 1960 and 1975, the year before his death. And while B.B. and Albert would have career-defining singles — “The Thrill is Gone” and “Born Under a Bad Sign,” respectively — Freddie’s hits were more diffuse; his biggest single, “Hide Away,” was released in the early days of rock ’n’ roll, and while it showcased his nimble fingers and ability to pick out complicated guitar lines, it didn’t really capture the fullness of what made Freddie, well, Freddie. Because Freddie King, perhaps more than his other sovereigns, was about a sound more than any specific song. That sound, a blending of the lightning-in-a-dry-field pyrotechnics of the Texas country blues with the el-train-in-a-blizzard thrust of Chicago blues, would spiral out from Freddie to inspire entire waves of white rock artists from Eric Clapton and Peter Green to Stevie Ray Vaughan and ZZ Top. While he was the last of the Three Kings to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the Texas Cannonball, as he was called, certainly belonged there.

But because pioneering a sound doesn’t necessarily translate to record sales, Freddie would spend most of his career hopping between record label heads who believed in him, who could hear his unique sound and think, “This guy deserves to ply his trade here,” and serve as something like his patrons, releasing his records and helping him provide loss leaders for his robust touring schedule. It would start with the early home of James Brown, King Records, and would end, mostly, with Leon Russell’s Shelter Records. But for a brief two-year period, during which he would release his best recordings — including My Feeling for the Blues — Freddie would be shepherded by a legendary saxophonist who made him one of the first signings to an Atlantic subsidiary, Cotillion, where he selected artists to record himself. King Curtis would serve as producer and arranger of Freddie’s greatest recordings, including his finest album-length statement, My Feeling for the Blues. It wouldn’t be any more of a hit than his other studio albums, but again, Freddie is about a sound, and the sound Freddie conjures up on My Feeling would echo out across blues and rock for generations to come. Record sales are a box score that don’t tell you the finer details of the game. The game Freddie King played here was eternal.

Though he made his name in Chicago, Freddie King was born in Gilmer, Texas, in 1934, and was taught the ins and outs of guitar from his mom and his uncle. He’d move to Chicago as a teen when, like many other Black families from the South, his relatives uprooted to find union jobs in a bigger Northern city and took Freddie with them. While he’d come to fame as part of the new generation of Chicago blues players forming in Muddy Waters' and Howlin’ Wolf’s wake, it was his time in Texas that would have the most tangible impact on his guitar playing, his sound. Where B.B. was known to make his guitar cry by bending notes at his will, and Albert hammered on his guitar like it had wronged him gravely, Freddie’s technique — finger picking and strumming hard at the same time — has its roots in Texas country and western swing and the fleeter Texas blues. Western swing is probably the most secretly impactful music we never talk about — name any 20th century artist with roots in Texas, and they grew up on the stuff — and you can hear the clipped lines and flutter of that regional music in Freddie’s guitar riffs. Freddie’s sound was eventually influenced by rock ’n’ roll, but you could always tell it was him on record: He shoots out of your speakers like a ’57 Cadillac screaming across the Texas oil flats. Once he arrived in Chicago, he’d add the blues flourishes of Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf — with whom he routinely gigged starting in his late teens — and eventually make a name for himself in Chicago's South Side blues scene. It’s here where I’m obligated to mention Freddie’s unique way of holding his guitar, the strap dangling off his right shoulder like a mailman carrying a mailbag. Nonchalant in its carelessness and so cool in its effortlessness. It’s a sight to behold in nearly every live video of Freddie.

Freddie’s time rising up the ranks in Chicago didn’t lead to a deal with local powerhouse Chess Records, however: The Chess brothers thought Freddie was destined to never sell, didn’t think that he had the talent necessary to be signed to their roster. He could occasionally book session work but never anything under his own name (which echoes how the Chess brothers handled Buddy Guy in the ’60s — they ostensibly signed Buddy but just never put out any records by him). Freddie recorded his first single, “Country Boy” b/w “That’s What You Think,” for a tiny local label, which didn’t sell but did feature an electric bass before it was en vogue for all blues bands to have someone pick the bass electrically.

In 1960, King Records, fresh off success with James Brown, opened a Chicago office and, upon hearing that Freddie was repeatedly passed on by Chess, saw an opportunity to stick it to their rivals and signed him. He hit the label’s studio in Cincinnati, and among the songs he cut was “Hide Away” — dedicated to the Chicago bar Mel’s Hideaway — which would be far and away his biggest hit, climbing to No. 29 on the pop charts. The rollicking instrumental would later be covered by Eric Clapton during his stint in John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers, which gave Freddie some notoriety amongst the rock ’n’ roll set and influenced basically every British rock guitarist of the mid-’60s. Freddie made seven LPs with King and the label’s subsidiary Federal between 1961 and 1965. At the beginning of 1966, King declined to renew Freddie’s recording contract, however, as his sales never again hit the peak of “Hide Away,” leading to the axeman relocating his wife and six kids to Dallas to be closer to home. He’d still tour the blues circuit, but 10 years into his professional career, he more or less thought his time as a recording artist might be finished, especially with R&B and soul dominating the airwaves.

A man instrumental (pun intended) in the sound of R&B and soul on Atlantic Records thought otherwise. Formed in 1968, Cotillion was an imprint under Atlantic, which, at least in its first few years until King Curtis’ death in 1971, served as the home of blues, soul and R&B artists who might not be big enough for the full Atlantic push but who still could make interesting albums in their own right. Curtis was fresh off playing sax on “Respect” and serving as Aretha’s musical director for live shows, and was a central figure in Atlantic building its soul sound in the late ’60s, so he was given free rein to sign and produce a variety of artists. The first LP to come out on Cotillion was by R&B crooner Brook Benton, and the third was Freddie’s eighth LP, Freddie King is a Blues Master. When King Curtis came calling, Freddie had been out of the recording studio for three years. But Curtis came upon a sound that captured Freddie’s talents better than any producer would before or after. Instead of leaning away from R&B and soul, Curtis paired Freddie with members of his own band, The Kingpins, who gave Freddie a sonic landscape to drive his guitar like an ATV, blasting over hills, through drum breaks and mowing down cacti. The rock-solid horn section and the pliant basslines provided firm bedrock for Freddie to be Freddie. But Blues Master plays like a tentative first step; Curtis recorded Freddie’s guitar a bit too high in the mix, and Freddie’s voice sometimes gets washed out in the saxes and horns.

By the next year, however, for the recording of My Feeling for the Blues, Freddie, King Curtis and The Kingpins were in lockstep, allowing Freddie to finally realize his destiny as the Third King of the Blues and ensconce himself as the missing link between Muddy Waters and Buddy Guy. My Feeling starts with a cover of Elmore James’ “Look On Yonder Wall” (shortened here to “Yonder Wall”), which Freddie sprays his Texas Cannonball shrapnel all over, from the machine gun solos to the interlocking grooves with the heavy horn section. King updates the lyrics to reference the war in Vietnam amid the tale of bailing on a romantic dalliance due to a paramore’s lover arriving home, atop a groove laid down by the band so thick you could float in it. King’s “Yonder Wall” would become the version aped by future players like Stevie Ray Vaughan and a staple of the legend-making international tours he’d undertake in the early ’70s (some footage of which is viewable on YouTube).

The other 10 songs alternate between upbeat ramblers and downtrodden, wide-eyed ballads, all buoyed by King’s emphatic and emotional playing. “Stumble” blasts off like an update to “Hide Away,” an instrumental that delays a monster Freddie solo to its final third as he smashes into the song’s stomp like a surprise guest at his own party. A cover of Texas blues legend T-Bone Walker’s “Stormy Monday” crawls slowly through its message that Tuesdays suck as bad as Mondays, and “Ain’t Nobody’s Business What We Do” could serve as a Freddie King highlight reel for his howling vocal performance and the number of solos he stomps out. “Woke Up This Morning” shoots out of your speakers like a firehose run amok, while “The Things I Used to Do” shows Freddie could do the down-home country blues of Muddy Waters with the best of them. By the time he gets to the mission-statement title track, you don’t need a guide to know much more about Freddie’s blues: he’s laid them all down on the line throughout My Feeling for the Blues.

Like most other blues albums released in 1970, My Feeling didn’t chart and neither did any of its singles. King left Cotillion the next year, signing to Leon Russell’s Shelter Records for three LPs (including 1972’s superlative The Texas Cannonball). His last album was released in 1975 on RSO (a label run by Bee Gees’ manager Robert Stigwood, another of Freddie’s label patrons), and in 1976, after years of touring 300 nights a year, King died of pancreatitis after cancelling a show in late 1976 complaining of stomach pains.

While his name might not be the first in the lineup of the Three Kings of the Blues, Freddie King’s feeling for the blues deserves more recognition, more love, and more attention. May this reissue serve as an opportunity for you, and for all of us, to give him his flowers.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Andrew Winistorfer is VMP’s Classics & Country Director, and a writer and editor of their books, 100 Albums You Need In Your Collection and The Best Record Stores In The United States. He’s written Listening Notes for more than 20 VMP releases, and co-produced the VMP Anthologies The Story of Philadelphia International Records, The Story of Quincy Jones, The Story of Impulse and the VMP Classics release of Nat Turner Rebellion's Laugh to Keep From Crying, and executive produced the VMP Anthology The Story of Vanguard. He lives in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

https://www.donstunes.com/freddie-king/

Freddie King- The Texas Cannonball

Freddie King was one of three blues giants with the surname King—along with B.B. and Albert—who were all unrelated.

Freddie was a forceful presence and formidable figure in two of the most prominent blues scenes. In the state he was born in (and to which he eventually returned), he was known as the “Texas Cannonball.” For much of the Fifties and early Sixties, he was a Chicago blues legend, particularly on the city’s West Side. Revered by his fans and respected by his peers, King was best-known for his searing, assertive solos and dynamic showmanship.

Living and singing the Blues

Born in Gilmer, Texas, King got his first guitar when he was five years old. “You might say I came from a blues family,” he said in 1971, noting that his mother and uncles played blues.

“Blues was the music I was born with.”

He grew up listening to and learning the styles of such country-blues figures as Blind Lemon Jefferson, Arthur Crudup, Big Bill Broonzy and Ligntnin’ Hopkins. He was also heavily influenced by B.B. King and T-Bone Walker.

His first guitar was a silvertone acoustic. His most prized guitar at that time was his Roy Roger acoustic. In a interview years later he recalled going to the general store to order it. The store owner asked him if his mother knew he was trying to order a guitar on her store account. Freddie replied ” no”. The store owner told him to get permission. His mother said “no”. She told him, “if you want a new guitar you will have to work for it.” He stated that he picked cotton just long enough to earn the money to purchase a Roger’s guitar.

After King’s family moved to Chicago from Texas, the teenager began playing the same local blues scene as Muddy Waters, Buddy Guy, Otis Rush and other Windy City legends, often joining in with Jimmy Rogers’s band.By night, Freddie mixed with Chicago’s finest bluesmen: Howlin’ Wolf told him, “Son, the Lord sure put you here to play the blues.” It was the usual sort of tale for an aspiring electric bluesmen, but there were many of those in ‘50s Chicago, and Freddie didn’t have it all easy. King signed with Federal Records in 1960 and began cutting a string of influential records produced by the label’s owner Syd Nathan. His first single on Federal was “Have You Ever Loved A Woman.” It reached 92 on the pop chart, but became part of blues and rock history. Eric Clapton and Duane Allman recorded their historic guitar-duet version on Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs.

King was still fingerpicking his guitar in the classic country blues style when he arrived in Chicago, but was soon influenced by Muddy Waters and his guitarist Jimmy Rogers to use a thumb pick and finger picks. Although King recalled that Waters and Rogers used two picks, King was using a thumb pick and two finger picks until Eddie Taylor showed him “how to get speed” playing with two picks. An important component of the stinging lead style that King developed was the use of a plastic thumb pick with a metal fingerpick (although some close observers claim that he sometimes also utilized his bare middle finger), as well as the use of his palm to dampen the strings to further emphasize the attack of the notes. King also cited Robert Lockwood, Junior (a.k.a. “Robert Junior” Lockwood), as a mentor.

Perhaps because of this “vocal-lead” style of guitar playing, King specialized in instrumentals that generally had a lot more swagger and swing than the rest of the genre. Even without lyrics, such numbers as “San-Ho-Zay,” “The Stumble” and “In the Open” (Stevie Ray Vaughan’s set-opener for years) set a vivid scenario. Chief among King’s wordless classics, however, is “Hide Away,” which has been the compulsory blues instrumental for 30 years. If you’ve spent any time in Texas blues clubs, you’ve heard it. Playing “Hide Away” is like showing your license to play the blues, and although the song’s structure was nicked from Hound Dog Taylor, with riffs pirated from “Peter Gunn” and “The Walk,” it remains a rich part of the legacy of Freddie King.

In 1969, King hired Jack Calmes as his manager, who secured him an appearance at the 1969 Texas Pop Festival, alongside Led Zeppelin and others, and this led to King’s being signed to Leon Russell’s new label, Shelter Records. The company treated King as an important artist, flying him to Chicago to the former Chess studios for the recording of Getting Ready and gave him a backing line-up of top session musicians, including rock pianist Leon Russell.

“Freddie is truly one of the all-time greats. He’s just one of those guys who seemed to be able to summon this limitless energy. When it was time to go, he just had another gear that most people just do not have.” Derek Trucks

Rock audiences and Blues loyalists all enjoyed a great run in the early to mid seventies when Freddy King carried the torch of the Blues for all to see. Performing close to 300 shows a year and enduring a brutal, constant schedule, King started to experience health issues. On December 28, 1976, Freddy King passed away due to complications from stomach ulcers. The world lost one of the greatest musicians to ever grace the planet. King was a giant in every sense of the word.

Legacy

In a 1985 interview, Eric Clapton cited Freddy King’s 1961 B side “I Love the Woman” as “the first time I heard that electric lead-guitar style, with the bent notes… [it] started me on my path.” Clapton shared his love of King with fellow British guitar heroes Peter Green, Jeff Beck and Mick Taylor, all of whom were profoundly influenced by King’s sharpened-treble tone and curt melodic hooks on iconic singles such as “The Stumble,” “I’m Tore Down” and “Someday, After Awhile.” Nicknamed “The Texas Cannonball” for his imposing build and incendiary live shows, King had a unique guitar attack. “Steel on steel is an unforgettable sound,” says Derek Trucks, referring to King’s use of metal banjo picks. “But it’s gotta be in the right hands. The way he used it – man, you were going to hear that guitar.” Trucks can still hear King’s huge impact on Clapton. “When I played with Eric,” Trucks said recently, “there were times when he would take solos and I would get that Freddy vibe.”

Texas blues are about loving all kinds of music with guts, whether it’s country, jazz or R&B, and they’re about respecting the past while blazing new trails. Although T-Bone Walker practically invented this rawhide style of electric blues, it was King who revved it up for the rock crowd by hoeing the turf between Walker and B.B. King.

During a 20-year recording career, King registered only one top-40 hit, when “Hide Away” peaked at No. 29 on the Billboard singles chart in 1961, but he was a sensation at hippie rock clubs all over the United States, from the Fillmore East to the Fillmore West. And he always stole the show in the European festivals.

“He taught me just about everything I needed to know…. when and when not to make a stand…when and when not to show your hand,” said Clapton in 1977. “And most important of all… how to make love to your guitar.”