SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2022

VOLUME ELEVEN NUMBER ONE

RAPHAEL SAADIQ

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

JON BATISTE

(December 25-31)

MULGREW MILLER

(January 1- 7)

VALERIE COLEMAN

(January 8-14)

CHARNETT MOFFETT

(January 15-21)

AMYTHYST KIAH

(January 22-28)

CHRISTONE INGRAM

(January 29--February 4)

MARCUS ROBERTS

(February 5-11)

IMMANUEL WILKINS

(February 12-18)

WYCLIFFE GORDON

(February 19-25)

FREDDIE KING

(February 26-March 4)

DOREEN KETCHENS

(March 5-11)

TERRY POLLARD

(March 12-18)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/mulgrew-miller-mn0000608135/biography

Mulgrew Miller

(1955-2013)

Artist Biography by Matt Collar

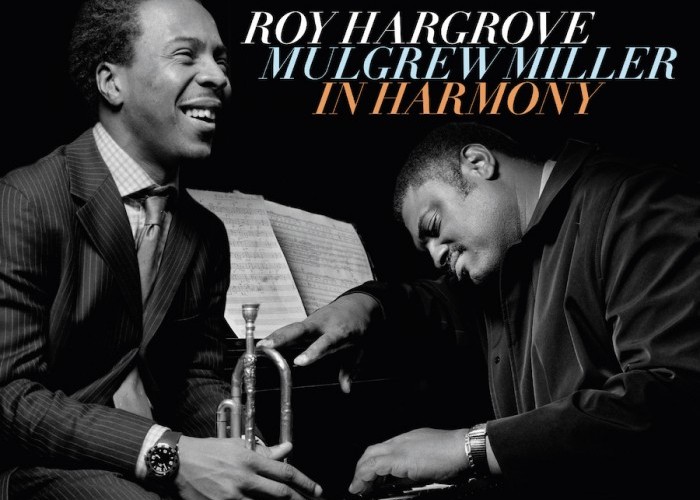

An immensely gifted pianist steeped in the jazz and gospel traditions, Mulgrew Miller had a boldly rhythmic, harmonically rich style that drew from players like Oscar Peterson, McCoy Tyner, and Bud Powell. Miller came into his own as a member of both Woody Shaw's band and Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers in the early '80s, before issuing his own highly regarded trio and small group albums, like 1985's Keys to the City, 1987's Wingspan, and 1994's With Our Own Eyes. All the while, he continued to find himself in demand as a sideman, playing with artists such as Branford Marsalis, Freddie Hubbard, Bobby Hutcherson, Wallace Roney, Tony Williams, and Kenny Garrett. Along with performing, he garnered respect as an educator, holding the position of Director of Jazz Studies at William Paterson University. His only solo piano album, Solo, arrived in 2010, just three years before he died tragically from a stroke. Miller remains one of the most beloved and highly regarded pianists of his generation, a sentiment buoyed by such posthumous archival releases as 2019's The Art of the Duo with Kenny Barron and 2021's In Harmony with Roy Hargrove.

Miller was born in 1955 in Greenwood, Mississippi, where he started to play piano by ear at age six. He began taking piano lessons and excelled, eventually performing at dances and playing gospel music at church. Early on, he gained inspiration from Ramsey Lewis. However, by his teens he was studying the music of Oscar Peterson, along other players like Art Tatum and Erroll Garner. He also began leading his own trio, performing at local functions. After high school, he enrolled at Memphis State University, attending on a band scholarship that found him playing euphonium. However, it was while at school that he met pianists Donald Brown and James Williams, who further encouraged his development, introducing him to the music of players like Bud Powell, Wynton Kelly, and McCoy Tyner. He also met trumpeter Woody Shaw, with whom he would later perform.

Following his university years, Miller spent time in Boston studying privately with Madame Margaret Chaloff. He also found work, playing with saxophonists Ricky Ford and Bill Pierce, before relocating to Los Angeles. In 1976, he accepted the piano chair in the Mercer Ellington Orchestra, touring with the ensemble for three years.

In 1980, he toured with vocalist Betty Carter and then joined Woody Shaw, with whom he made his recorded debut on 1981's United. There were also dates with Johnny Griffin, Bobby Watson, Terence Blanchard, and others. It was on the recommendation of Blanchard and Donald Harrison that Miller was recruited into Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, touring and recording with the legendary drummer from 1983 to 1986. Under Blakey's forceful sway, Miller matured as a player, solidifying his reputation as one of the most authoritative pianists of his generation. His contemporaries and elders took notice, and Miller found himself recording throughout the '80s with such luminaries as Branford Marsalis, Bobby Hutcherson, Wallace Roney, Joe Henderson, Benny Golson, Kenny Garrett, Freddie Hubbard, and more.

As a leader, Miller made his solo debut with 1985's Keys to the City on Landmark, a trio album with bassist Ira Coleman and drummer Marvin "Smitty" Smith. More albums followed on the label, including 1986's Work! with bassist Charnett Moffett and drummer Terri Lynne Carrington, and 1987's Wingspan, a sextet date with Moffett, saxophonist Kenny Garrett, vibraphonist Steve Nelson, and others. He also formed Trio Transition with Reggie Workman and Freddie Waits, recording several albums, including a 1987 session with Oliver Lake. Away from his solo work and after he had parted ways with Blakey, he joined drummer Tony Williams' group, performing with the former Miles Davis alum until the group disbanded in 1993.

In 1992, Miller moved to the Novus label with Hand in Hand, playing in both a quintet and sextet with Kenny Garrett, Christian McBride, Joe Henderson, Eddie Henderson, Steve Nelson, and Lewis Nash. He released several more trio albums with bassist Richie Goods and drummer Karriem Riggins, including 1995's Getting to Know You. He also paired with bassist Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen for 1999's The Duets, drawing inspiration from the 1940s work of Duke Ellington and Jimmy Blanton. The '90s also found him working with a bevy acclaimed performers, including Donald Byrd, Joe Lovano, and Dianne Reeves. He recorded regularly with Wallace Roney, appeared with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, and toured with the New York Jazz Giants, an all-star ensemble featuring Jon Faddis, Tom Harrell, Lew Tabackin, Bobby Watson, Ray Drummond, and Carl Allen.

The early 2000s found Miller continuing to lead his group, releasing albums on MaxJazz like 2002's The Sequel and 2004's Live at Yoshi's, Vol. 1. He also recorded with Brian Lynch, Jeremy Pelt, Ron Carter, Cassandra Wilson, and others. Miller moved into education, accepting the position of Director of Jazz Studies at William Paterson University in 2005. Around the same time, Lafayette College awarded him an honorary doctorate in Performing Arts and hosted him as Artist in Residence. He still remained active as a performer, joining Dave Holland's sextet and John Scofield's band. Solo, a solo piano concert Miller gave at the Jazz en Tête festival in Clermont-Ferrand, France in 2000, arrived on Space Time Records in 2010. That same year, Miller suffered a minor stroke. Following a period of recovery he returned to work, performing in Denmark with the Klüvers Big Band, working in a duo with Kenny Barron, and touring Europe with Yusef Lateef and Archie Shepp. Sadly, Miller suffered a second stroke and died in Allentown, Pennsylvania on May 29, 2013; he was 57 years old.

A posthumous album of duo performances with pianist Barron, The Art of the Duo, arrived in 2019. A second duo album, In Harmony, appeared in 2021 and featured Miller in two concerts from 2006 and 2007 with trumpeter Roy Hargrove.

http://mulgrewmiller.jazzgiants.net/biography/

Biography

Mulgrew Miller (pianist) was born on Aug. 13, 1955, in Greenwood, Mississippi and passed away on May 29, 2013 in Allentown, Pennsylvania at the age of 57.

Miller was born in a small town along the Mississippi delta. Miller’s father purchased a piano when he was six, leaving a big impression on the young boy. Miller would sit at the piano and pick out melodies to popular songs. Mulgrew would often learn hymns by ear and play them for his father when he returned home from work. When he was eight years old, he began to take formal lessons from a local teacher named Albert Harrison.

At the age of ten, Miller began to go to gigs with his older brother, receiving his first experience seeing live music. Throughout his teenage years, Mulgrew received numerous opportunities to perform; performing in church services, a rhythm and blues band and in an assortment of school ensembles. Mulgrew also played the sousaphone in his school’s marching band and formed a trio that would perform at social events.

Miller first became interested in jazz at the age of fourteen when he saw pianist Oscar Peterson on the television program “The Joey Bishop Show.” The years of piano lessons and performing paid off when Mulgrew received a scholarship to study music at The University of Memphis, then called Memphis State University. During college, he studied with pianists James Williams and Donald Brown.

Miller stayed at Memphis State for two years, ultimately moving to Boston where he received lessons from Margaret Chaloff, the mother of baritone saxophonist Serge Chaloff. While in Boston, Miller performed with saxophonists Ricky Ford and Billy Pierce. In 1976, Mulgrew decided to move to Los Angeles in order to build his career.

In January 1977, Miller furthered his career when he joined the Duke Ellington Orchestra, led by his son trumpeter Mercer Ellington. Miller was recommended for the job by his friend saxophonist Bill Easley. The job with Ellington brought him to New York City where he began to make a name for himself in the city’s jazz scene.

Miller remained with the group until early 1979 when he joined the rhythm section of singer Betty Carter’s group alongside bassist Curtis Lundy and drummer Greg Bandy. In late 1980, he joined trumpeter Woody Shaw’s group, performing with him until the summer of 1983.

After joining tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin for a brief tour, Miller joined drummer Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, making his debut with the group on 1984’s New York Scene. During his time with Blakey, Miller started to record with several up and coming young jazz musicians including trumpeter Terence Blanchard, tenor saxophonists Donald Harrison, John Stubblefield and Branford Marsalis, alto saxophonist Bobby Watson and vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson.

In 1985, Miller made his debut recording Keys To The City for producer Orrin Keepnews’s label, Landmark. Starting in 1986, Miller became a member of drummer Tony Williams’ quintet.

While with Williams, Miller pursued a dazzling array of side projects. In 1987, Mulgrew formed the cooperative ensemble Trio Transition with bassist Reggie Workman and drummer Freddie Waits. The group toured throughout Europe and sometimes included alto saxophonist Oliver Lake as a featured soloist.

The same year, Miller began to perform with tenor saxophonist Benny Golson, appearing on his album Stardust. 1987 Mulgrew also performed on trumpeter Wallace Roney’s album Verses and also played with the group Wingspan on a self-titled album. In 1992, when Williams dissolved his group, Mulgrew further focused his attention on these other projects.

Miller toured with the New York Jazz Giants before performing with clarinetist Eddie Daniels and vibraphonist Gary Burton.

Miller continued to lead a trio while working as a sideman on various recordings. In 1993, Mulgrew performed with guitarist Ron Muldrow and tenor saxophone Joe Lovano.

The same year, Miller along with pianists Harold Mabern, James Williams, Geoff Keezer and Donald Brown formed The Contemporary Piano Ensemble. Initially starting after a performance at the 1991 Montreaux Jazz Festival, the group consists of four pianists, with one sitting out, performing simultaneously with a rhythm section. The group performed last in 1996.

1993 also saw Mulgrew performing on bassist Steve Swallow’s album Real Book with Lovano, trumpeter Tom Harrell and drummer Jack DeJohnette. On “Bite Your Grandmother,” DeJohnette plays an opening cadenza before the unison melody of Lovano and Harrell begins the top of the form. With the unrestrained performance of DeJohnette, Miller and Swallow prove to be a reliable and interesting rhythmic partnership with the two men utilizing the upper registers of their instruments to contrast with the dark sound of Lovano. Mulgrew’s solos offer brief, but poignant examples of his harmonic intelligence and aptitude.

The following year, Mulgrew performed with trumpeter Nicholas Payton on his debut album From This Moment. In 1995, Miller performed with Lovano at the Village Vanguard and performed with alto saxophonist Charles McPherson on his album Come Play With Me. Two years later, Miller performed with tenor saxophonist Greg Tardy on his album Serendipity. The same year, Mulgrew toured Japan as part of the group “100 Gold Fingers,” featuring fellow pianists Tommy Flanagan, Ray Bryant, and Kenny Barron. In 1998, he performed on vibraphonist Stefon Harris’s album A Cloud of Red Dust.

In 1999, Miller began to work with bassist Niels-Henning Orsted Pedersen, and together they recorded Duets, an album featuring the music of pianist Duke Ellington and bassist Jimmy Blanton. The duo became a trio with the inclusion of drummer Alvin Queen in 2000. The group performed throughout Europe, ultimately deciding to expand in 2005 after the death of Pederson.

On September 17, 2002, Miller released the album The Sequel with Wingspan. Released on the Maximum Jazz label, the album features vibraphonist Steve Nelson, saxophonist Steve Wilson, trumpeter Duane Eubanks, bassist Rickie Goods, and drummer Kareem Riggins.

A highlight from this session is the song “Dreamsville,” which features Miller and Wilson performing as a duo. Miller impeccably sets up the song with a beautiful introduction using rich voicings to evoke the sentimental feeling of the song. On his solo, Mulgrew demonstrates the perfect method for constructing a solo by starting with a small idea and building upon it using different melodic devices and motifs. Mulgrew’s skill as an accompanist is quite clear during Wilson’s performance when he augments Wilson’s sound with bright ornamentations that serve to enhance his overall tone.

In 2003, Miller received a commission from the Dayton Contemporary Dance Company to write an original piece for the company. The result was The Clearing in the Woods, which Miller and Wingspan performed with the company. Noted choreographer Ronald K. Brown choreographed the piece.

The same year, Miller performed on trumpeter Terell Stafford’s album New Beginnings. On “New Beginnings Suite: Berda’s Bounce,” Miller begins the song with a solo that perfectly executes the swift atmosphere of the song. During tempo changes, Mulgrew and drummer Dana Hall lead the ensemble through the changes with care and ease. Mulgrew displays a fervent touch throughout the song, evoking a touch that is reminiscent of McCoy Tyner.

In 2003, Miller performed on bassist Ron Carter’s album The Golden Striker with guitarist Russell Malone. The same year, Miller received the “Distinguished Achievement” award from The University of Memphis. For the 2004-2005 school year, Mulgrew was the Artist in Residence at Lafayette College. His recent releases include Live at the Kennedy Center in 2006 and Live at the Kennedy Center: Vol. 2 in 2007. Both albums are from his trio’s performances at the Kennedy Center in Washington D.C. and feature bassist Derrick Hodge and drummer Rodney Green.

On May 20, 2006, Mulgrew was awarded an honorary doctorate of performing arts from Lafayette College. As of late, Mulgrew has been the director of jazz studies at William Paterson University in Wayne, New Jersey. Miller resides in Easton, Pennsylvania with his wife Tanya, son Darnell and daughter Leilani.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/meet-mulgrew-miller-mulgrew-miller

Meet Mulgrew Miller

"In a trio or quintet, I sometimes tend to become more focused on melodic improvising. And especially in a quintet, I'll have a more concise approach to playing. But as a solo performer, I try to be more orchestral and use more of the entire instrument."

All About Jazz: You were born in Greenwood, Mississippi, and grew up listening to blues, gospel and R&B music. What attracted you to jazz?

Mulgrew Miller: The thing that pulled me toward jazz was jazz itself. By the time I really discovered what jazz was all about, I'd been playing rhythm and blues-mostly for dances. And I'd played gospel music in my church since childhood. In fact, just about all the music I played growing up was permeated with blues and gospel. I was also studying classical music, and in high school I had a trio. We played at cocktail parties, but we really didn't know what we were doing. We were going toward jazz, but we really didn't know how to approach it.

But the thing that really did it was seeing Oscar Peterson

play on a TV show. When I saw him, I realized there was a way to do

something with music—and do it with integrity and in a way that demanded

virtuosity but wasn't classically oriented.

AAJ: Attending Memphis State University was a real key to your development as a jazz pianist, wasn't it?

MM: I met James Williams and Donald Brown

while I was Memphis State, and they became very good friends as well as

fine professional jazz pianists as well. We'd go together to hear Phineas Newborn, Jr.

quite often. On weekends, he'd be playing at a local club called the

Gemini. So that's where I really began to seriously learn jazz.

AAJ: Your first high profile job as a jazz musician was with the Duke Ellington Orchestra, right?

MM:

Yes, I was asked to join the Ellington band in 1977, but I had subbed

for the band's regular pianist while I was still at Memphis State. After

I graduated I went to Boston, then to Los Angeles. I ran into the band again and they asked me to play with them for three weeks. It turned into three years.

AAJ: Being part of the Ellington band must have been a real learning experience.

MM:

It was—both musically and personally. I was only 21 years old when I

joined. It was a real experience working in a big band, and especially

with Ellington's music. And touring with a big band and all the

different personalities definitely was a unique experience too.

AAJ: From the Ellington band you went directly into playing for singer Betty Carter and her trio. How did that happen?

MM: I had gotten to know Cedar Walton,

and it turned out both he and James Williams recommended me to Betty.

She called, and that was a real turning point for me in my career

because that was when I actually moved to New York City. That's when I got into a whole different kind of circus— the New York jazz scene. And I've been in that circus ever since.

AAJ: You spent eight months with Betty Carter, then moved on to join Woody Shaw's band. He's certainly been a very underrated musician in terms of his contributions to jazz, hasn't he?

MM:

No doubt about it. Woody Shaw wasn't merely a great trumpet player and

bandleader. He was a visionary. He certainly left his mark on the jazz

repertoire in terms of compositions. And he also left his mark on the

language of jazz in terms of the trumpet. I'm thinking of the way he was

dealing with music—the language that he used when improvising really

explored new areas on the trumpet that hadn't been dealt with before, at

least at that level of sophistication. And his compositions were very

forward-looking in terms of harmonic colors.

MM: Actually, I had a short stint playing with Johnny Griffin, then Art Blakey called me to join the Messengers. Then Tony Williams asked me to be a part of the new band he was putting together to record for Blue Note. And I was with Tony almost seven years. So from the Ellington band through Tony Williams, I was literally in a band every single day for 16 years.

AAJ: But somehow you eventually managed to get your own career going as a leader while doing all that. Tony Williams didn't tour nearly as much as the other leaders you played for. Did that give you the time to get your own groups going?

MM: I would say my work as a leader actually started the last year I was with the Messengers, and then really picked up when I was with Tony. So that coincided with doing my initial recordings for the Landmark label in 1985.

AAJ: You've recorded 10 albums as a leader, and worked in a variety of contexts, from a basic trio to the quintet lineup on Wingspan that featured alto sax and vibes. Looking back, do you have a favorite among those recordings—or a preferred lineup?

MM: No, in terms of both recordings and lineups. There are moments on each of those recordings that if I could pick and choose and put together, I'd have something I could really brag about. But there isn't a specific recording I think stands out. And I like both the trio and quintet formats. I still have a regular trio with Richie Goods on bass and Karriem Riggins on drums. And for my Wingspan Quintet I add Steve Wilson on alto sax and Steve Nelson on vibraphone.

AAJ: Given the consistent critical acclaim for your recordings as a leader, it's surprising that your last one, Getting to Know You, came out back in 1995. Surely you've received offers to record. Why have you chosen not to?

MM: I have had several offers, but I haven't pursued them aggressively. Some have been better than others, but I haven't had any really strong, concrete offers that seem rewarding enough to me. You know, I've made enough recordings already. I don't have to do a free record for anybody.

AAJ: Clearly the recording industry—especially in jazz—has a pretty dismal track record in providing the quality of support and distribution needed to give these recordings a decent shot to make it in the marketplace. Some jazz musicians like Gary Bartz have resorted to starting their own independent labels to issue their music. Have you thought of doing that?

MM: Well, first of all, we could do a whole interview on this subject. Let's just say the record industry is totally screwed up. And I have entertained thoughts about putting my own records out. But I'm not sure if I have both the focus and the time to get involved in a complex project like that.

AAJ: How do you approach performing solo? Do you have a set program, or do you just go with the flow?

MM: I'll have a general outline in terms of repertoire of what I'm going to play before I start. But sometimes I'll make spur-of-the-moment decisions to change what I'm going to perform. There are a lot of factors that will determine that, from the type of venue where I'm performing to the reaction of the audience.

AAJ: From a technical standpoint, how does your keyboard approach change from a quintet or trio setting to a solo performance?

MM: In a trio or quintet, I sometimes tend to become more focused on melodic improvising. And especially in a quintet, I'll have a more concise approach to playing. But as a solo performer, I try to be more orchestral and use more of the entire instrument. After all, it's just you, so you need to come up with different things to make the music more interesting. In essence, I do things that are more pianistic.

AAJ: You've been appearing on quite a few recordings lately, from releases by Diane Reeves and Rene Marie to Steve Turre and Gary Burton, Aside from your regular groups, anything else new?

MM: For the last couple of years I've been doing duo appearances with the Danish bassist, Niels-Henning Orsted Pedersen. We started working together as a result of the Ellington centennial celebration. Nils was asked to do a recording to commemorate the bass/piano duos of Ellington and Jimmy Blanton, and he called me to work with him. We've been doing some European concerts since then, and working with him in a duo setting is especially great.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mulgrew_Miller

Mulgrew Miller

Mulgrew Miller (August 13, 1955 – May 29, 2013) was an American jazz pianist, composer, and educator. As a child he played in churches and was influenced on piano by Ramsey Lewis and then Oscar Peterson. Aspects of their styles remained in his playing, but he added the greater harmonic freedom of McCoy Tyner and others in developing as a hard bop player and then in creating his own style, which influenced others from the 1980s on.

After leaving university he was pianist with the Duke Ellington Orchestra for three years, then accompanied vocalist Betty Carter. Three-year stints with trumpeter Woody Shaw and with drummer Art Blakey's high-profile Jazz Messengers followed, by the end of which Miller had formed his own bands and begun recording under his own name. He was then part of drummer Tony Williams' quintet from its foundation, while continuing to play and record with numerous other leaders, mostly in small groups. Miller was Director of Jazz Studies at William Paterson University from 2005, and continued to play and tour internationally with other high-profile figures in the music until his death from a stroke at the age of 57.

Early life

Mulgrew Miller was born in Greenwood, Mississippi,[1] to parents who had been raised on plantations.[2] He had three brothers and four sisters.[3] His family was not musical, but they had a piano, which no one in the house could play.[4] Miller, however, played tunes on the piano from the age of six, playing by ear.[5] He had piano lessons from the age of eight.[6] As a child, he played blues and rhythm and blues for dances, and gospel music in a church.[1] His family was Methodist, but he played in churches of multiple denominations.[7] His principal influence on piano at this stage was Ramsey Lewis.[8]

While at high school, Miller formed a trio that played at cocktail parties.[1] His elder brother recommended that he listen to pianist Oscar Peterson, but there was no way of doing this in Greenwood until Peterson appeared on The Joey Bishop Show on television[4] when Miller was about 14.[8] After watching Peterson's performance, Miller decided to become a pianist: "It was a life changing event. I knew right then that I would be a jazz pianist".[1] Miller later mentioned Art Tatum and Erroll Garner as piano influences during his teenage years.[9] Miller reported years later that he always found that playing fast was easy, so playing slowly and with more control were what he had to work hardest on.[10]

After graduating from Greenwood High School,[3] Miller became a student at Memphis State University in 1973,[11] attending with a band scholarship.[4] He played euphonium, but, during his two years at the university,[4] Miller met pianists Donald Brown and James Williams, who introduced him to the music of players such as Wynton Kelly, Bud Powell, and McCoy Tyner.[5] Still at Memphis State, Miller attended a jazz workshop, where one of the tutors was his future bandleader, Woody Shaw, who stated that they would meet again in two years.[4] They did meet again two years later, and Shaw remembered the young pianist.[4] After leaving university in 1975, Miller took lessons privately in Boston with Madame Margaret Chaloff, who had taught many of the pianists that Miller admired.[8] He later commented: "I should have stayed with her longer, [...] but at that time I was so restless, constantly on the move."[2] Miller played with saxophonists Ricky Ford and Bill Pierce in Boston.[12] That winter, Miller was invited to Los Angeles by a school friend and decided to go, to escape the northern cold.[8] He stayed on the West Coast for a year, playing locally in clubs and a church.[8]

Later life and career

1976–86

Towards the end of 1976, Miller was invited to substitute for the regular pianist in the Duke Ellington Orchestra (by then led by Mercer Ellington; his father died in 1974).[8] Miller had performed the same role for one weekend around a year earlier, and the new work was to be for only three weeks, but he ultimately toured with the orchestra for almost three years.[8][11] His membership of the orchestra helped him, in the words of a piano magazine, to get "respect as a powerful, two-fisted pianist adept at delivering entrancingly lyrical and gracefully introspective runs as well as dazzling and buoyant passages".[10] He left in January 1980,[8] after being recruited by vocalist Betty Carter, with whom he toured for eight months that year.[13] He was then part of Shaw's band from 1981 to 1983, thereby, in Miller's view, fulfilling his destiny from their earlier meetings.[4][14] In 1981, he made his studio recording debut, on Shaw's United.[15]: 11 During the early 1980s, he also accompanied vocalist Carmen Lundy,[16][17] and played and recorded with saxophonist Johnny Griffin.[15]: 11

Miller was recommended for Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers by Blakey members Terence Blanchard and Donald Harrison,[18]: 110–11 and he joined the drummer's band in 1983.[14] Initially, he struggled to fit in with Blakey dominating the rhythm section, but Miller stated that, over his period with the band: "My playing just generally matured. I don't think one single characteristic changed, but the experience certainly boosted my confidence".[18]: 111 At times during concert performances he was allotted a solo piano spot, which Miller used to play medleys.[19][20] His presence in the Jazz Messengers cemented his reputation within jazz.[21] His recording career as a leader began in 1985, with Keys to the City, the first of Miller's several recordings for Landmark,[5] which continued with Work! the following year.[22] Jon Pareles' review of a solo concert in 1986 observed that Miller's playing showed the influence of Powell on some numbers and Kelly on others, but that, overall, he was developing "his own, authoritative style".[23]

Later 1986–94

After leaving Blakey in 1986,[14] Miller was pianist in drummer Tony Williams' quintet from its foundation that year until it disbanded around 1993.[12][24][25] Miller remained active between tours with Williams' band, in part by touring with his own groups.[21] The first of these was formed in 1987 and named Wingspan,[11][26] as, Miller explained, "sort of a dedication to the legacy of Charlie Parker – Bird, you know".[8] It became one of Miller's main bands, enduring through changes of personnel, and featured a lot of his compositions in its performances.[8] Another band was known as Trio Transition, which contained bassist Reggie Workman and drummer Freddie Waits.[21] They released the album of the same name in 1987.[27][28]

Miller also played on Williams bandmate Wallace Roney's first three recordings (1987–89),[29] and many other albums recorded by other leaders in the late 1980s.[30] These included an album with long-term collaborator Steve Nelson,[31]: 1202 a recording by trumpeter Donald Byrd,[32] comeback albums from alto saxophonist Frank Morgan,[31]: 1165 and the first of a series of releases with tenor saxophonist Benny Golson.[12]

Miller and his family moved to Palmer Township, Lehigh Valley, Pennsylvania in 1989.[33][34] In that year, he joined three other pianists in recording a CD tribute to Memphis-born pianist Phineas Newborn, Jr.[35] This group, the Contemporary Piano Ensemble, performed intermittently until 1996, often playing together on four separate pianos.[36] In 1990, Miller traveled to the Soviet Union to appear as pianist in Benny Golson's band at the first Moscow International Jazz Festival.[37] In 1992, Miller also toured domestically and internationally with the New York Jazz Giants, a septet containing Jon Faddis, Tom Harrell, Lew Tabackin, Bobby Watson, Ray Drummond, and Carl Allen.[38][39] Miller continued to accompany vocalists, including on recordings with Dianne Reeves and Cassandra Wilson.[21] Starting in 1993, he also played and recorded with saxophonist Joe Lovano.[40]

The influence of Williams continued into Miller's own projects, including their compositions and arrangements: The Guardian reviewer of Miller's 1992 Hand in Hand, his first for Novus Records, commented that "it's his occasional boss, drummer Tony Williams, who has made the strongest impression on the way he organises the material. The opening 'Grew's Tune' and the bluesier numbers would slot unnoticed into the Williams library."[41]

1995–2013

For several years after he had turned 40, Miller concentrated on composing and playing his own music.[42] He reduced his recording and club appearances, as well as one-day associations.[42] The stimulus for this change had built gradually from Miller's first studio recording in 1981: "my recording activity increased and by the time that it got into 1986–87 I was on so many records it was unbelievable until eventually it became rather overwhelming and stressful, so I had to cut back."[15]: 11 He did continue to record, often with musicians he had established relationships with: in 1996 he reunited with Williams to appear on what became the drummer's final recording, Young at Heart;[43] further albums led by Kenny Garrett, Nelson, Reeves, and others were made in the period 1997–99.[44]

In 1997, Miller toured in Japan with 100 Golden Fingers, a troupe of 10 pianists.[45] He joined bassist Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen in 1999 to record The Duets an album based on 1940s performances by Duke Ellington and Jimmy Blanton.[46] The two men toured Europe the following year, with drummer Alvin Queen added for some concerts.[46][47]

In 2002, Miller's discography as leader began to expand again, as Maxjazz started to release recordings.[30] A series of four concert recordings were released over the following years: Live at The Kennedy Center Vol. 1 and Live at The Kennedy Center Vol. 2 (recorded in 2002), with Derrick Hodge (bass) and Rodney Green (drums); and Live at Yoshi's Vol. 1 and Live at Yoshi's Vol. 2 (recorded in 2003), with Hodge and Karriem Riggins (drums). In 2002 Miller joined bassist Ron Carter's Golden Striker Trio, with guitarist Russell Malone.[48]: 235 The trio occasionally toured internationally for the next decade.[49][50] In 2003, Miller was commissioned to write a score for the Dayton Contemporary Dance Company; after writing The Clearing in the Woods and having it choreographed by Ronald K. Brown, Miller and his band played the piece for performances by the company.[12][51]

In the mid-2000s, Miller joined bassist Dave Holland's band, changing it from a quintet to a sextet, and adding gospel and soul elements to the group's sound.[52] Around this time, Miller had two regular bands of his own: a piano trio, and a quintet featuring saxophone and vibraphone.[53] He also became heavily involved in music education: Miller was the Director of Jazz Studies at William Paterson University from 2005,[6] and was the Artist in Residence at Lafayette College in 2008,[54] which was two years after it had awarded him an honorary doctorate in Performing Arts.[46]

Miller's only solo album, a 2000 concert recording entitled Solo, was released in 2010 and was well received by critics for the imagination and harmonic development in Miller's playing.[55][56] Also in 2010, Miller joined guitarist John Scofield's new band.[57] That year, Miller had a minor stroke.[26] After this, he took medicine, changed his diet and lost weight;[58] he also reduced his touring and recording.[21] In February 2012 he traveled to Denmark to play with Klüvers Big Band; selections from one of the five concerts were released under Miller's co-leadership as Grew's Tune.[59] In autumn 2012, he performed as a piano duo with Kenny Barron,[60] continuing an association that had begun some years earlier.[61] In the winter of that year he toured Europe as part of a quintet led by reeds players Yusef Lateef and Archie Shepp.[62]

On May 24, 2013, Miller was admitted to Lehigh Valley Hospital, near Allentown, Pennsylvania, having suffered another stroke.[6][63] He died there on May 29.[6][63] Miller made more than 15 albums under his own name during his career,[46] and appeared on more than 400 for other leaders.[5] His last working trio consisted of Ivan Taylor on bass and Green on drums.[46] Bassist Christian McBride commented on the day of Miller's death: "I sincerely hope every self-respecting jazz musician takes this day to reflect on all the music Mulgrew left us."[64]

Personal life and personality

Miller was survived by his wife, son, daughter, and grandson.[6] Miller married on August 14, 1982.[3] He was quiet and gentle,[56] and was "a modest man, with a self-deprecating sense of humour".[21] Miller described his own attitude towards music in a 2005 interview:

I worked hard to maintain a certain mental and emotional equilibrium. It's mostly due to my faith in the Creator. I don't put all my eggs in that basket of being a rich and famous jazz guy. That allows me a certain amount of freedom, because I don't have to play music for money. I play music because I love it.[42]

Style and influence

Ben Ratliff, writing for The New York Times, commented that, "As a composer, Mr. Miller is difficult to peg; like his piano playing, he's a bit of everything."[65] Critic Ted Panken observed in 2004 that Miller the pianist "finds ways to conjure beauty from pentatonics and odd intervals, infusing his lines with church and blues strains and propelling them with a joyous, incessant beat".[42] John Fordham in The Guardian commented that Miller's "melodic fluency and percussive chordwork [...] recalled Oscar Peterson [...but] with glimpses of the harmonically freer methods of McCoy Tyner", and that Miller was much more than the hard bop player that he was often stereotyped as being.[26] The obituary writer for DownBeat observed that "Miller could swing hard but maintained grace and precision with a touch and facility that influenced generations of musicians."[5]

Miller had a strong reputation with fellow musicians.[6][21] Pianist Geoffrey Keezer was convinced that he wanted to be a pianist after attending a performance by Miller in 1986.[6] Vibraphonist Warren Wolf stated that Miller helped him early in his career, including by being a link to jazz history: "you're getting that experience of playing with Art Blakey, that attitude of 'Yes, it's my band, but you have to give other people a chance to shine.'"[66] Robert Glasper also cited Miller as an influence,[26] and wrote and recorded "One for 'Grew" as a tribute.[6]

Speaking in 2010, Miller commented on his approach to playing standards, which was more conservative than that of many others: "I believe in giving due respect to the melody, playing it as true as possible, [...] a solo is a creative process that improves the melody."[67] He almost never transcribed recordings (something that jazz musicians are typically taught to do); Miller credited this with slowing his learning process, but also with allowing him to express himself more freely, as he reached his own understanding of the compositions he played.[4]

Miller explained the lack of critical attention he received as follows: "Guys who do what I am doing are viewed as passé."[6][42] He also contrasted his own approach with that of performers who produced "interview music": "something that's obviously different, and you get the interviews and a certain amount of attention".[42]

Discography

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mulgrew Miller. |

- Discography as leader, by Michael Fitzgerald.

- "The Folk Element Is Intact: (Four Mulgrew Miller Solos)" by Ethan Iverson.

- Mulgrew Miller discography at Discogs

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/30/arts/music/mulgrew-miller-jazz-pianist-dies-at-57.html

Mulgrew Miller, Influential Jazz Pianist, Dies at

57

Credit: Hiroyuki Ito for The New York Times

Credit: Hiroyuki Ito for The New York Times

Mulgrew Miller, a jazz pianist whose soulful erudition, clarity of touch and rhythmic aplomb made him a fixture in the postbop mainstream for more than 30 years, died on Wednesday in Allentown, Pa. He was 57.

The cause was a stroke, said his longtime manager, Mark Gurley. Mr. Miller had been hospitalized since Friday.

Mr. Miller developed his voice in the 1970s, combining the bright precision of bebop, as exemplified by Bud Powell and Oscar Peterson, with the clattering intrigue of modal jazz, especially as defined by McCoy Tyner. His balanced but assertive style was a model of fluency, lucidity and bounce, and it influenced more than a generation of younger pianists.

He was a widely respected bandleader, working with a trio or with the group he called Wingspan, after the title of his second album. The blend of alto saxophone and vibraphone on that album, released on Landmark Records in 1987, appealed enough to Mr. Miller that he revived it in 2002 on “The Sequel” (MaxJazz), working in both cases with the vibraphonist Steve Nelson. Among Mr. Miller’s releases in the past decade were an impeccable solo piano album and four live albums featuring his dynamic trio.

Mr. Miller could be physically imposing on the bandstand — he stood taller than six feet, with a sturdy build — but his temperament was warm and gentlemanly. He was a dedicated mentor: his bands over the past decade included musicians in their 20s, and since 2005 he had been the director of jazz studies at William Paterson University in New Jersey.

If his sideman credentials overshadowed his solo career, it wasn’t hard to see why: he played on hundreds of albums and worked in a series of celebrated bands. His most visible recent work had been with the bassist Ron Carter, whose chamberlike Golden Striker Trio featured Mr. Miller and the guitarist Russell Malone on equal footing; the group released a live album, “San Sebastian” (In+Out), this year.

Born in Greenwood, Miss., on Aug. 13, 1955, Mulgrew Miller grew up immersed in Delta blues and gospel music. After picking out hymns by ear at the family piano, he began taking lessons at age 8. He played the organ in church and worked in soul cover bands, but devoted himself to jazz after seeing Peterson on television, a moment he later described as pivotal.

At Memphis State University he befriended two pianists, James Williams and Donald Brown, both of whom later joined Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. Mr. Miller spent several years with that band, just as he did with the trumpeter Woody Shaw, the singer Betty Carter and the Duke Ellington Orchestra, led by Ellington’s son Mercer. Mr. Miller worked in an acclaimed quintet led by the drummer Tony Williams from the mid-1980s until shortly before Williams died in 1997.

Mr. Miller, who lived in Easton, Pa., is survived by his wife, Tanya; his son, Darnell; his daughter, Leilani; a grandson; three brothers and three sisters.

Though he harbored few resentments, Mr. Miller was clear about the limitations imposed on his career. “Jazz is part progressive art and part folk art,” he said in a 2005 interview with DownBeat magazine, differentiating his own unassuming style from the concept-laden, critically acclaimed fare that he described as “interview music.” He added, “Guys who do what I am doing are viewed as passé.”

But Mr. Miller worked with so many celebrated peers, like the alto saxophonist Kenny Garrett and the tenor saxophonist Joe Lovano, that his reputation among musicians was ironclad. And his legacy includes a formative imprint on some leading players of the next wave, including the drummer Karriem Riggins and the bassist Derrick Hodge, who were in one of his trios. The pianist Robert Glasper once recorded an original ballad called “One for ’Grew,” paying homage to a primary influence. On Monday another prominent pianist, Geoffrey Keezer, attested on Twitter that seeing Mr. Miller one evening in 1986 was “what made me want to be a piano player professionally.”

Today Is The Question: Ted Panken on Music, Politics and the Arts

Mulgrew Miller, R.I.P. (1955-2013)

A Downbeat Article and Several Interviews

I am deeply saddened at the death of Mulgrew Miller, who succumbed yesterday to his second severe stroke in several years. He cannot be replaced, but his impact will linger. It’s hard to think of a pianist of his generation more deeply respected by his peers. He found ways to refract various strands of post World War Two vocabulary — Oscar Peterson and Bud Powell, Monk and McCoy, Chick Corea and Woody Shaw — into a singular soulful, swinging conception. I heard him live dozens of times, whether in duos and trios at Bradley’s or Zinno’s, or with his magnificent, underrated, and influential group Wingspan at the Vanguard and other venues, with his working trios, and on dozens of sideman dates with the likes of Joe Lovano, Von Freeman, and a host of others. I can’t claim to have known Mulgrew well, but nonetheless had many opportunities to speak with him, casually between sets at a gig, and more formally at several sitdowns on WKCR and, once over dinner for an article — I didn’t have quite as much space as I hoped to get — that appeared in DownBeat in 2005. I am appending the article, the transcript of that conversation,of a conversation a month before that on WKCR, and an amalgam transcript of separate WKCR encounters in 1988 and 1994, one of them a Musician’s Show. We did a very far-ranging WKCR interview in 2007, as yet un-transcribed.

Mulgrew Miller: No Apologies:

Down Beat

Ironies abound in the world of Mulgrew Miller.

On the one hand, the 49-year-old pianist is, as Eric Reed points out, “the most imitated pianist of the last 25 years.” On the other, he finds it difficult to translate his exalted status into full-blown acceptance from the jazz business.

“It’s a funny thing about my career,” Miller says. “Promoters won’t hire my band, but they’ll book me as a sideman and make that the selling point of the gig. That boggles my mind.”

“Mulgrew is underrated,” says Kenny Garrett, who roomed with Miller in the early ‘80s when both played with Woody Shaw. “He’s influenced a lot of people. I’ll hear someone and go, ‘Man, is that Mulgrew or someone who’s playing like him?’ When they started talking about the ‘young lions,’ he got misplaced, and didn’t get his just due.”

Miller would seem to possess unsurpassed bona fides for leadership. As the 2004 trio release Live At Yoshi’s [MaxJazz] makes evident, no pianist of Miller’s generation brings such a wide stylistic palette to the table. A resolute modernist with an old-school attitude, he’s assimilated the pentagonal contemporary canon of Bill Evans, McCoy Tyner, Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, and Keith Jarrett, as well as Shaw’s harmonic innovations, and created a fluid personal argot. His concept draws on such piano-as-orchestra signposts as Art Tatum, Oscar Peterson, Ahmad Jamal and Erroll Garner, the “blowing piano” of Bud Powell, the disjunctive syncopations and voicings of Thelonious Monk, and the melodic ingenuity of gurus like Hank Jones, Tommy Flanagan and Cedar Walton. With technique to burn, he finds ways to conjure beauty from pentatonics and odd intervals, infusing his lines with church and blues strains and propelling them with a joyous, incessant beat.

“I played with some of the greatest swinging people who ever played jazz, and I want to get the quality of feeling I heard with them,” Miller says. “For me it’s a sublime way to play music, and the most creative way to express myself. You can be both as intellectual and as soulful as you want, and the swing beat is powerful but subtle. I think you have to devote yourself to it exclusively to do it at that level.”

Consequential apprenticeships with the Mercer Ellington Orchestra, Betty Carter, Johnny Griffin and Shaw launched Miller’s career. A 1983-86 stint with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers put his name on the map, and he cemented his reputation during a long association with Tony Williams’ great cusp of the ‘90s band, a sink-or-swim environment in which Miller thrived, playing, as pianist Anthony Wonsey recalls, “with fire but also the maturity of not rushing.” By the mid-‘80s he was a fixture on New York’s saloon scene. Later, he sidemanned extensively with Bobby Hutcherson, Benny Golson, James Moody, and Joe Lovano, and from 1987 to 1996 he recorded nine well-received trio and ensemble albums for Landmark and RCA-Novus.

Not long after his fortieth birthday, Miller resolved to eschew club dates and one-offs, and to focus on his own original music. There followed a six-year recording hiatus, as companies snapped up Generation-X’ers with tenuous ties to the legacy of hardcore jazz.

“I won’t call any names,” Miller says. “But a lot of people do what a friend of mine calls ‘interview music.’ You do something that’s obviously different, and you get the interviews and a certain amount of attention. I maintain that jazz is part progressive art and part folk art, and I’ve observed it to be heavily critiqued by people who attribute progressivity to music that lacks a folk element. When Charlie Parker developed his great conception, the folk element was the same as Lester Young and the blues shouters before him. Even when Ornette Coleman and Coltrane played their conceptions, the folk element was intact. But now, people almost get applauded if they don’t include that in their expression. If I reflected a heavy involvement in Schoenberg or some other ultra-modern composers, then I would be viewed differently than I am. Guys who do what I am doing are viewed as passé.

“A lot of today’s musicians learn the rudiments of playing straight-ahead, think they’ve got it covered, become bored, and decide ‘let me try something else.’ They develop a vision of expanding through different areas—reggae here, hip-hop there, blues here, soul there, classical music over here—and being able to function at a certain level within all those styles. Rather than try to do a lot of things pretty good, I have a vision more of spiraling down to a core understanding of the essence of what music is.”

This being said, Miller—who once wrote a lovely tune called “Farewell To Dogma”—continues to adhere to the principle that “there is no one way to play jazz piano and no one way that jazz supposed to sound.” He is not to be confused with the jazz police. His drummer, Kareem Riggins, has a second career as a hip-hop producer, and has at his fingertips a lexicon of up-to-the-second beats. When the urge strikes, bassist Derrick Hodge might deviate from a walking bass line to slap the bass Larry Graham style. It’s an approach familiar to Miller, who grew up in Greenwood, Mississippi, playing the music of James Brown, Aretha Franklin and Al Green in various Upper Delta cover bands.

“It still hits me where I live,” he says. “It’s black music. That’s my roots. When I go home, they all know me as the church organist from years ago, so it’s nothing for me walk up to the organ and fit right in. I once discussed my early involvement in music with Abdullah Ibrahim, and he described what I went through as a community-based experience. Before I became or wanted to become a jazz player, I played in church, in school plays, for dances and for cocktail parties. I was already improvising, and always on some level it was emotional or soul or whatever you want to call it. I was finding out how to connect with people through music.

“By now, I have played jazz twice as long as I played popular music, and although that style of playing is part of my basic musical being, I don’t particularly feel that I need to express myself through it. To me, it’s all blues. The folk element of the music doesn’t really change. The blues in 1995 and in 1925 is the same thing. The technology is different. But the chords are the same, the phrasing is the same, the language is the same—exact same. I grew up on that. It’s a folk music. Folk music is not concerned with evolving.”

For all his devotion to roots, Miller is adamant that expansion and evolution are key imperatives that drive his tonal personality. “I left my hometown to grow, and early on I intended to embrace as many styles and conceptions as I could,” he states. “When I came to New York, I had my favorites, but there was a less celebrated, also brilliant tier of pianists who played the duo rooms, and I tried to hear all of those guys and learn from them. The sound of my bands changes as the musicians expand in their own right. I’m very open, and all things are open to interpretation. I trust my musicians—their musicianship and insights and judgments and taste—and they tend to bring things off in whatever direction they want to go. In the best groups I played with, spontaneity certainly was a strong element.”

Quiet and laid-back, determined to follow his muse, Miller may never attain mass consumption. But he remains sanguine.

“I have moments, but I don’t allow myself to stay discouraged for

long,” he concludes. “I worked hard to maintain a certain mental and

emotional equilibrium. It’s mostly due to my faith in the Creator. I

don’t put all my eggs in that basket of being a rich and famous jazz

guy. That allows me a certain amount of freedom, because I don’t have to

play music for money. I play music because I love it. I play the kind

of music I love with people I want to play with. I have a long career

behind me. I don’t have to apologize to anybody for any decisions I

make.”

[-30-]

* * *

Mulgrew Miller (11-22-04) – (Villa Mosconi):

TP: I’m going to ask you a broad question. It might be embarrassing or hard to answer. For a lot of pianists, a lot of people your age and younger, and some who are older than you, too, you’re regarded as the heir to the throne. You know this. Tommy Flanagan was quoted a few times. A lot of pianists in their mid-40s think of you as the guy who brings the tradition into the present in a way that they admire. I don’t mean this as a way for you to brag on yourself. But what is the position that you think you occupy within the piano lineage at this point? What is it you think you represent? What is it you think you’ve been able to accomplish?

MILLER: Whoo! Well, first of all, I consider myself an eternal student of the music. Perhaps I have been able to bring a fairly wide palette of ideas and a range of stylistic things that I have amalgamated into a sound. That sound that I have probably lends itself to a lot of different ways of playing. Because one can be a student of sort of a narrow range of styles. For instance, one can be a student of maybe the ‘60s piano players, and be good at that; or one can be a student of that as well as some of the earlier styles; and so on. My initial influences were people like Oscar Peterson and Ahmad Jamal and Phineas Newborn and Art Tatum and those kind of people, and sometimes you don’t find that in a guy my age and younger. A lot of times, their biggest influences are maybe Oscar, but usually it’s… [CAESAR SALAD ARRIVES] Usually, a guy might start off liking one of Miles’ many piano players, which I do love, too.

TP: In the Musician Shows that we did, Wynton Kelly was in there, Bill Evans was in there…

MILLER: Yes. But my foundation in jazz comes from an earlier basis, the old Art Tatum thing and Erroll Garner and Oscar.

TP: Did you get to that early?

MILLER: In my mid-teens. When I started playing jazz, those were the players that I heard first. A little while later, I heard McCoy Tyner and Herbie and Chick Corea and Keith Jarrett.

TP: There are quite a few players who have become adept at playing a fairly broad timeline, but you seem to have been there a little earlier than some of them. But maybe it’s just because you’re older.

MILLER: Yeah! [LAUGHS]

TP: Perhaps you came first in that generation by dint of playing with Mercer Ellington and Woody Shaw and Art Blakey. But sensibility-wise, is that something you’re predisposed to? Are you very open-minded? Did you come from an open-minded background? Because it’s not like you’re from one of the big cities. You’re from a fairly small town in Mississippi. You played in the church, you played rhythm-and-blues. I’m sure there was some talent, but maybe a parochial world-view or maybe not—I don’t know. But tell me something about what you see giving you the curiosity and wherewithal to explore all this.

MILLER: Expansion and evolution is part of my motto. The reason I left my hometown was to expand and grow, and if I was going to do that, I had the notion early on to embrace all these different things, especially in terms of piano styles and ranges of conception and so on. If I heard a great piano player, I liked him. When I came to New York, I made it a point to hear every good pianist who was playing, not just my favorites, so that I could learn something from everybody who was playing.

TP: Give me a few examples.

MILLER: My favorites would be Cedar Walton or McCoy Tyner or Herbie Hancock, Ahmad Jamal—or among my favorites. But of course, in New York playing the duo rooms there was another less celebrated tier of pianists you heard, but brilliant all the same. I tried to hear all of those guys and learn from them.

TP: Let’s talk about the Memphis approach to piano playing. You and James and Donald Brown coming up behind Mabern and Phineas Newborn…there’s a distinctive approach. It seems like gravitating to New York was a natural. You all fit into what the New York thing was or was becoming. Can you talk about some of the stylistic things you brought to the table when you arrived?

MILLER: I’m glad you brought that up, because I have never ascribed to a Memphis school of piano. Even though there are similarities in our styles, but most of the people who influenced either one of the pianists that you are naming from Memphis, are not from Memphis. If you talk to the late James Williams and Donald Brown and myself, you’d find that, yes, we were all inspired and influenced by Phineas Newborn and Harold Mabern and Charles Thomas. That’s the soil in which we were rooted. But you would also find that we’re all influenced by Herbie Hancock and McCoy Tyner and Hank Jones and OP and all these people who were not from Memphis, and in various ways and various degrees. So I don’t ascribe to a city as a way of identifying a certain sound.

TP: Is it more some of the influences that were available Memphis, or a way of filtering that information? Or does it have to do with all of you playing R&B and church music?

MILLER: Well, yeah. But what I’m saying is that a person living in Texas, having the experience, if he didn’t announce where he was from, you might not know if he was from Memphis or not.

TP: I’ll take your point.

MILLER: Or Alabama, let’s say, Do you think a guy from Birmingham…

TP: Are you thinking specific?

MILLER: No, I’m not.

TP: Because in the Jazz Messengers, for ten years, it was James, Donald and you coming out of that nexus. So it’s not as though I’m trying to put capital letters…

MILLER: One of the things I think we have in common is that we all studied a certain breed of piano players, which critics call the mainstream. We’re all students of that breed of piano player. But we’re not the only ones. And my point is, I don’t think we all sound alike.

TP: That wasn’t my implication at all.

MLLER: Right. So a guy from Hot Springs, Arkansas, might sound more like me than a guy from Memphis.

TP: But I suppose I’m trying to trace the continuity from when you started forming your ideas about how music should take shape up to this point. And music being such a social art and having such an oral component… I’m just thinking that this was the early ‘70s, the type of jazz you play wasn’t particularly popular or in the air, you were playing a lot of different music, and you each have a personal way of bringing the lineage into the future.

MILLER: I was discussing my early involvement in music with Abdullah Ibrahim one time, and he had an excellent term for describing that experience. He called it a community-based experience. Which I had early on. One of the interesting things about jazz is that players come from all kinds of backgrounds and experiences. But before I became a jazz player or wanted to become a jazz player, I had varying experiences playing in the community. I played in church. I played in school plays. I played proms. I played for dances in an R&B band. I played for cocktail parties. So there’s what I’d like to call a social connection there that I think maybe was nurtured early on in my playing, a kind of connection to people. The point I’m trying to make is that before I became a jazz player, I was already improvising, and I was always on some level emotional or soul or whatever you want to call it. I was already in the process of finding out how to connect with people through music.

TP: Is that still how you see what you do?

MILLER: Yes.

TP: It’s still consistent.

MILLER: It maybe isn’t as consistent as I’d like it to be. But you hear different players, and some people communicate… It’s something about what they do that reaches people on a certain level more than some other players. I’m not sure where I fit into that whole thing. But I began trying to make that connection real early in my development.

TP: What’s more important on some level, communication or the aesthetic?

MILLER: As I think I understood you, for me, one is not different from the other. Communicating in the moment is what… I’m a very moment kind of guy. I’m not an over-organized musical mind by any means. My intention, my agenda when I sit down at the piano is to connect with people. I think that comes first.

TP: You’re talking about coming up in this community-based experience. The scene has changed so much.

MILLER: It has.

TP: And the social nature of music-making has changed a great deal. I was just noticing in the recording session, these guys who are half our age, how they’re behaving and what they’re thinking about. The drummer, who is extremely talented, is relaxing between takes by scratching on Doug E. Fresh. The trumpet player’s twin is doing a video verité of the whole thing. Everyone is, on one level, extremely sophisticated about technology and art and ideas, and on the other hand, there’s a sort of naiveté that’s kind of charming as well. Not that I went to so many sessions 20 years ago, but that scene would seem unimaginable twenty years ago. You relate and employ in your band very young musicians, people who will commit to you.

MILLER: Well, they are products of their own time, as I am a product of my own time. However, as you stated, the scene is different now. I think one of the things is that musicians don’t find the scene now as enticing as it was when I came on the scene. There aren’t as many bands, there’s not as many clubs to play in across the country. Sometimes they look in other directions for a way to express themselves and for other career options. Let’s face it. The scene as it is now is not terribly encouraging to a young artist, and they come on the scene and see another little fellow in another arena making hundreds of thousands of dollars just rapping, rhyming. They’ve grown up with that. So in their minds, this beats sitting at home waiting for the phone to ring.

TP: Well, Kareem Riggins, your present drummer, is a successful hip-hop producer. So you’re experiencing all that first-hand.

MILLER: Yes. And my bassist is involved in pop music as well.

TP: When you were coming up… I know Donald Brown was a house musician at Stax/Volt. Did you ever do anything like that?

MILLER: At Stax? No. I came in a little town where there was nothing like Stax…

TP: I meant once you got to Memphis.

MILLER: No. That scene was just about on its last legs.

TP: But do you think that then… It seems the young players today maybe compartmentalize a little more. It’s like hip-hop is hip-hop… It’s like Lampkin was saying to Duck when Duck was doing that rap, and saying, “No one my age raps,” and he said, “Jazz musicians!” So here’s a young guy who obviously has a lot of respect for what being a jazz drummer means, but he also has respect for what the other thing is. He’s not trying to conflate one with the other. I think at that time, a lot of jazz musicians were trying to mix the two, sometimes with success and sometimes not so successfully.

MILLER: True. For one thing, jazz musicians playing in R&B bands go way back! Benny Golson and Coltrane played in R&B as it was known then. Which at the time, though… what we called R&B then sounded a lot more like jazz than it does now.

TP: Tadd Dameron was arranging for one of those bands.

MILLER: Yeah! And through the decades, people like Idris Muhammad, who was playing with Sam Cooke and so forth…

TP: He invented the Meters beat. Not to mention Blackwell.

MILLER: Yeah, exactly. So all these people… McCoy played with Ike and Tina Turner at one point! So this thing about straddling the fence, so to speak, is really old. As I said, I grew up playing the music of James Brown and Aretha Franklin and Al Green and all that kind of stuff.

TP: Does that music still mean a lot to you?

MILLER: I still enjoy it. Because it’s soul music. It’s black music. And that’s my roots. It still hits me where I live.

TP: But there some musicians among your contemporaries who present that music and arrange it and work with it on records. You haven’t done that so much on your records. There may be implications of that vibe on one tune or another. But it isn’t an explicit reference in what you do. Is that deliberate?

MILLER: Well, you see, by now, I have played jazz twice as long as I played pop music. By now. Although that is a part of my basic musical being, I don’t feel particularly that I need to express myself through that style of playing. However, I am not against paying homage to my roots, as it were. It’s nothing for me to go into a Baptist church… Like, when I go home, it’s nothing for me to go to church and walk right up to the organ and fit right in. I do it. I did it this August.

TP: Do you do it in Pennsylvania?

MILLER: No. I don’t have time to be involved in a church. But if I go home and visit a church in my community, they all know me there as the church organist from years ago. So they all assume that that’s what I’ve come to do.

TP: There are different ways that artists construct their persona as they grow and develop. Some people want to be completely autobiographical and encompass everything. For instance, such as Cassandra Wilson did in the last few years. You played with her on one of the best straight-ahead singing records of the period. But now she’s bringing in everything. But it doesn’t seem that to do this gnaws at your insides.

MILLER: No, it does not. Well, my experience is that I played with some of the greatest swinging people that played jazz—Art Blakey and Tony Williams and Johnny Griffin and Woody Shaw. I’ve been so captivated by that whole experience that I want to deepen that. Not necessarily to isolate myself from everything else. But that’s my focus because I see how that is so special. The way THEY did it was so special! Not everybody who’s playing swing music (let’s call it that for now…swing-based music) swings with that same quality. In today’s world, it’s possible to be expansive, to do a little bit of this and a little of that. But somehow, when I hear some of those groups, I don’t hear the quality of the feeling of swing that I heard when I played with those guys. So my focus… Rather than to dilute that by trying to do a whole lot of things pretty good, I want to do that really well.

TP: Let’s talk about what it is that makes that approach to music so special. There are a number of people, your peers included, who love bebop and swing music, and it’s about the only thing they love. Or at least, publicly that’s what they say…

MILLER: Well, it’s not the only thing I love. But what makes it so special for me is that, of all the different areas of music that I might delve into, that is, I’ve found, the most creative way of expressing myself. You can express power and beauty all at the same time, and yet express intellect. And the swing beat is powerful but yet subtle. So I am just enthralled with all of that. When I played with guys like Art Blakey and Tony Williams, and when I heard Elvin Jones, and when I play with Ron Carter, and all of the great swingers that I’ve played with, I see how that music affects people. For me, it’s a sublime way of playing music. So I think you have to be devoted to that in a singular way almost to do it at that level.

TP: When did you begin to be that devoted to it?

MILLER: When I heard Oscar Peterson. I knew that I wanted to play this music with that kind of quality of feeling, and with that kind of integrity.

TP: Let’s talk about why this music, against all odds, and with this culture the way it is, still survives. There may not be a big market, but there sure as heck are a lot of young musicians who can play. And most of them are willing to learn. Obviously, there’s jazz education. But if it were just jazz education, then the music would be an artifact. And it’s not. Perhaps you can address through some of the young musicians who play with you.

MILLER: I think young musicians are hearing and feeling the same thing I felt when I first heard the music. When they first hear this music, they see an opportunity to express themselves at a level that they had not been able to do previously in whatever other musical pursuits they were pursuing. I think this music that we call jazz is the only form of music that offers that opportunity, to have an integration of sophisticated harmony and sophisticated melody and sophisticated rhythm all at the same level, and be creative and improvise within that. I mean, you have sophistication in classical music in terms of harmony and melody, but the creative level is not there. I’ve played all of these musics on some level—R&B, and I’ve studied classical. But Jazz is the most enthralling music because you can express all of that. You can be as intellectual as you want to and yet be as soulful as you want to at the same time. So to me, that’s what captivates the young musician.

TP: For instance, John Lampkin knows all the hip-hop and drum-bass stuff. His beats are up to the second. I’m sure Karriem is the same way.

MILLER: Yes, he is.

TP: Though with you he plays the function. But are you paying attention to all these things? Are you incorporating what’s happened since Art Blakey and Tony Williams died, and the music of your sidemen into your own conception?

MILLER: Only what they bring themselves. At this stage of the game, I’m not trying to delve into that area with them. But they bring their own sensibilities from that. And things might happen on the bandstand that might not have happened with an older group of musicians. And I mean, just slightly older. For instance, Derrick might slap the bass a la Larry Graham.

TP: Whereas Peter Washington wouldn’t.

MILLER: Yeah. Peter Washington wouldn’t do that.

TP: Lewis Nash probably wouldn’t be playing those beats that Lampkin…

MILLER: Yes. However… [LAUGHS] That wouldn’t be called for with me. But something like that might happen.

TP: So you think all this is healthy. People incorporating this inclusive… For instance, Donald seems to want to do rap as well as rappers, and do smooth jazz as well as anyone doing smooth jazz. That’s sort of his stated purpose, and he doesn’t do a bad job, and doing these things doesn’t dilute what he’s able to do. I don’t know what the total effect is, but…

MILLER: I don’t see it as unhealthy. Let me put it that way. However, I don’t see how being good at rapping will help your understanding of what melody is, or deepen your knowledge of what harmony is. Most jazz musicians today have a pretty good knowledge of melody and harmony. But even with the vast knowledge that’s out there, many of us are not even close to the core of what that is all about.

TP: Who is?

MILLER: Who is? Well, I can tell you who was.

TP: We also have to be careful not to search for the unreachable Holy Grail. Those cats may not have thought they had it either.

MILLER: Well, for instance, Bobby Hutcherson is a person who is creative on a deep level, and his involvement with harmony and melody and rhythm is very deep.

TP: Mr. Nelson seems like he contemporary embodiment of that.

MILLER: Without a doubt. Kenny Garrett is a person who is involved with music on a very deep level. There are others. But I find that a lot of musicians have learned the rudiments of playing straight-ahead and become bored with it. [LAUGHS] But they think that they’ve got that covered, so “let me try something else.”

TP: Why do you think they get bored with it?

MILLER: Well, in a lot of cases it’s because they haven’t had a chance to explore that with one of the great ones. Because if you’ve just come through four years at Berklee School of Music, or you’ve copied X amount of saxophone solos, and haven’t had a chance to do the thing I’m talking about, to see how that works in communicating and connecting with people, then you might be able to think that you’ve attained a certain amount of mastery, but in fact, all you might have is rudiments. And a lot of that will not be effective if you get on the bandstand with Art Blakey or Elvin Jones or Roy Haynes or Ron Carter or Sonny Rollins or Johnny Griffin.

TP: What’s it been like playing with Ron Carter lately? You’ve been doing the trio thing for a year or so now. Is it your first sustained playing with him?

MILLER: Yes. Let me tell you this. When I was listening to Four and More and all those records in college, I never in my wildest dreams imagined that I would have two different relationships with people on that record—Tony and Ron. For me to have an ongoing relationship with Ron just blows my mind.

Ron is such a deep bass player. He’s unique in a lot of ways, but particularly he’s unique in the sense that he’s found a way to… Well, let’s say that he epitomizes the long, sustained note and the bouncing beat. Sometimes it’s hard to find those two together. A lot of times you find guys with the long sustained note, but no beat. Sometimes you find a guy with a big beat and he gets a thump out of the instrument. But Ron epitomizes that thing about the sustained note and the bouncing beat. His walking conception is second to none. It’s very advanced, Ron’s walking conception.

TP: It seems to me he’s the master of a certain type of counterpoint that’s singular to jazz, both rhythmic and melodic, with a call-and-response feel. Is the record The Golden Striker emblematic of how the trio sounds?

MILLER: Pretty much. We’ve stretched out a bit more since we did that record. Ron is a big fan of the MJQ with John Lewis, and this trio reflects his conception. That’s the kind of effect he wants to get over.

TP: Are there any other situations in which you’re playing with someone’s band as steadily as that?

MILLER: No. My priority now is my band.

TP: So with Ron, it’s because there’s still something you can learn and garner.

MILLER: Well, yes. Ron is one of the few people that I would do sideman work with now. But even in that case, it takes a back seat to my own stuff as a leader.

TP: He understands that, no doubt. He’s an eminently practical man. So you’re not talking about recording sessions or coming in for hire.

MILLER: No, I’m not talking about that. I’m talking about appearing on club dates.

TP: I have seen you as a sideman on some club dates. What are the criteria? Does it have to be musically satisfying? Someone you have a long-standing relationship with?

MILLER: Basically, it has to in some way serve my career (let’s be honest about it), and it has to be musically edifying. It has to be challenging. It just has to be on a certain level. Playing with Ron and Bobby Hutcherson. Those are two people that I’ve singled out who I’d play club dates with as a sideman. That being said, over the years I’ve worked a lot with Benny Golson, James Moody, and Joe Lovano. But I’ve scaled back from just doing sideman appearances. This thing with Ron is kind of an ongoing project. It’s not just dropping in on a club to be a sideman. It’s a conception and an idea… And where else would I play with a bass player like Ron Carter?

TP: And the piano plays a very prominent role…

[PAUSE]

TP: Is it important for you to have a trio as such… It might tempt you

to do your next record with Ron Carter and Lewis Nash, let’s say. But I

get the feeling you’d think twice about it because you see the trio as

an extension of your vision more than just what you play.

MILLER: Exactly. That’s very well said. And with an organized, more or less, trio…

TP: Well, the thing is, it doesn’t seem that organized. You don’t seem to approach it that way.

MILLER: Well, it’s not, in that sense. But it is in the sense that there’s a continuation of musical thought from gig to gig, and if you have a set group of musicians, it evolves over time. That’s the main reason why one would do that.

TP: Is there also a sense of following through on your own experience of having played with elders and passing down information? Do you feel some broader sense of responsibility beyond your career?

MILLER: I do.

[END OF SIDE A]

TP: Kenny does it, Terence does it. Wynton does it even.

MILLER: Some musicians have a vision of themselves as expanding through different areas of music—reggae here, hip-hop there, blues here and soul there, and classical music over here—and being able to function at a certain level within all those styles. I have a vision more of spiralling down to a core, to a core understanding of the essence of what music is. What playing melody really is beyond the language that we have come to know as the vocabulary…

TP: You’re trying to get to something that’ s beyond vocabulary?

MILLER: Yes. For instance, a young musician might have transcribed many solos and be armed with an expansive amount of vocabulary, but may still not understand what creative melodic expression is. Not to mention harmonic expression. Or a drummer might study the styles of several different drummers, but still not have insight. To me, knowledge and insight are two different things. Knowledge has to do with intellectual facts about something. Insight has more to do with a sort of understanding of what the essence of something is, beyond what the facts might be.

TP: You made a comment on the radio in 1994 that people make a mistake about McCoy Tyner. They talk about him as a phase of music or a style of music that is something to get beyond, and you said they’re missing a fundamental point, that he and Coltrane created a sound, that the sound had profound implications and was almost a metaphor for something beyond itself, and that it fundamentally changed the sound of jazz. Which also implies the notion of the music as something broader than itself, as actual narrative, having a similar force. Is that something that you are striving to communicate on some level?