SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2022

VOLUME ELEVEN NUMBER ONE

RAPHAEL SAADIQ

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

JON BATISTE

(December 25-31)

MULGREW MILLER

(January 1- 7)

VALERIE COLEMAN

(January 8-14)

CHARNETT MOFFETT

(January 15-21)

AMYTHYST KIAH

(January 22-28)

JOHNATHAN BLAKE

(January 29--February 4)

MARCUS ROBERTS

(February 5-11)

IMMANUEL WILKINS

(February 12-18)

WYCLIFFE GORDON

(February 19-25)

FREDDIE KING

(February 26-March 4)

DOREEN KETCHENS

(March 5-11)

TERRY POLLARD

(March 12-18)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/johnathan-blake-mn0000776998/biography

Johnathan Blake

(b. July 1, 1976)

Artist Biography by Matt Collar

An adept jazz drummer, Johnathan Blake has distinguished himself as both a first-call sideman and leader in his own right. Steeped in the Philly jazz traditions of players like Mickey Roker and Philly Joe Jones, Blake first emerged in the 2000s on the East Coast. Although primarily known for his work in the acoustic, post-bop style with outfits like the Mingus Big Band and veteran players like Tom Harrell and Kenny Barron, Blake has moved ably between straight-ahead and more genre-bending styles, contributing to projects by Jaleel Shaw, Omer Avital, Questlove, and others. A gifted composer, he has released his own inventive solo albums, including 2012's The Eleventh Hour and 2018's Trion.

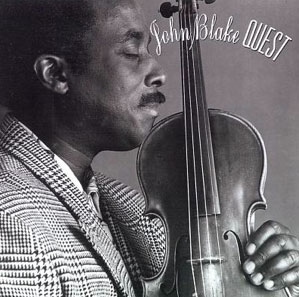

Born in 1976 in Philadelphia, Blake grew up in a musical family the son of jazz violinist John Blake, Jr. He started playing drums at age ten, and by his teens was playing in the Lovett Hines Youth Ensemble, during which time he also began to compose. Also as a teenager, he played with saxophonist Robert Landham in a youth jazz ensemble at the noted Philadelphia institution Settlement Music School, where he rubbed shoulders with contemporaries like Jaleel Shaw, Christian McBride, and Joey DeFrancesco. At night, he also gained valuable experience sitting in at local clubs with veteran legends like Shirley Scott and Mickey Roker. After graduating from George Washington High School, Blake further honed his skills in the jazz program at William Paterson University. There, he studied with such well-regarded teacher/performers as Rufus Reid, John Riley, Steve Wilson, and Horace Arnold. In 2006 he earned an ASCAP Young Jazz Composers Award, and the following year, he received his Masters from Rutgers University, where he focused on composition and studied with Ralph Bowen, Conrad Herwig, and Stanley Cowell.

While in school, he also continued to seek out professional opportunities, working with the Oliver Lake Big Band, Roy Hargrove, Russell Malone, and David Sanchez. As a member of the Mingus Big Band, Blake helped earned Grammy nominations for 2002's Tonight at Noon and 2005's I Am Three. He has also garnered the respect of jazz veterans, working with Randy Brecker, Joe Locke, and Ronnie Cuber, among others. He is also a longtime member of trumpeter Tom Harrell's group, having appeared on many of the trumpeter's albums, including 2007's Light On, 2009's Prana Dance, and 2011's Time of the Sun.

In 2012, Blake released his debut album as leader, The Eleventh Hour, which featured Harrell, as well as Robert Glasper, Jaleel Shaw, Ben Street, and others. More work followed with Harrell, including appearing on the trumpeter's albums like 2013's Colors of a Dream, 2015's First Impressions, and 2016's Some Gold, Something Blue. He also appeared on Dr. Lonnie Smith's 2016 album Evolution and played on pianist Kenny Barron's Grammy-nominated 2016 trio album, Book of Intuition, and 2018 octet date Concentric Circles.

Also in 2018, Blake returned to his solo work with Trion, featuring saxophonist Chris Potter and bassist Linda May Han Oh. He also reunited with Dr. Lonnie Smith for All in My Mind and paired with tenor saxophonist Eric Alexander for 2019's Leap of Faith. In 2020, he joined pianist Barron and bassist Dave Holland for the elegant trio album Without Deception. That same year, he also contributed to tenor saxophonist Oded Tzur's boundary-pushing album Here Be Dragons.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/johnathan-blake

Johnathan Blake

Johnathan Blake, one of the most accomplished drummers of his generation, has also proven himself a complete and endlessly versatile musician. Blake’s gift for composition and band leading reflects years of live and studio experience across the aesthetic spectrum. Heralded by NPR Music as “the ultimate modernist,” he has collaborated with Pharoah Sanders, Ravi Coltrane, Tom Harrell, Hans Glawischnig, Avishai Cohen, Donny McCaslin, Linda May Han Oh, Jaleel Shaw, Chris Potter, Maria Schneider, Alex Sipiagin, Kris Davis and countless other distinctive voices. DownBeat once wrote, “It’s a testament to Blake’s abilities that he makes his presence felt in any context.” A frequent presence on Blue Note records over the past several years, Blake has contributed his strong, limber pulse and airy precision to multiple leader releases from Blue Note artists including Dr. Lonnie Smith’s Breathe (2021), All in My Mind (2018) and Evolution (2016) and Kenny Barron’s Concentric Circles (2018), the latter whose trio Blake has been a vital member for nearly 15 years.

Born in Philadelphia in 1976, Blake is the son of renowned jazz violinist John Blake, Jr. — himself a stylistic chameleon and an important ongoing influence. After beginning on drums at age 10, Johnathan gained his first performing experience with the Lovett Hines Youth Ensemble, led by the renowned Philly jazz educator. It was during this period, at Hines’s urging, that Blake began to compose his own music. Later he worked with saxophonist Robert Landham in a youth jazz ensemble at Settlement Music School. Blake graduated from George Washington High School and went on to attend the highly respected jazz program at William Paterson University, where he studied with Rufus Reid, John Riley, Steve Wilson and Horace Arnold. At this time Blake also began working professionally with the Oliver Lake Big Band, Roy Hargrove and David Sanchez. In 2006 he was recognized with an ASCAP Young Jazz Composers Award, and in 2007 he earned his Masters from Rutgers University, focusing on composition. He studied with the likes of Ralph Bowen, Conrad Herwig and Stanley Cowell. Deeply aware of Philadelphia’s role as a historical nerve center of American music, Blake has immersed himself in the city’s storied legacy — not just jazz but also soul, R&B and hip-hop. In many ways he’s an heir to Philadelphia drum masters such as Philly Joe Jones, Bobby Durham, Mickey Roker and Edgar Bateman, not to mention younger mentors including Byron Landham, Leon Jordan and Ralph Peterson, Jr..

Johnathan Blake's debut release on Blue Note Records signals shifting tides for a career that’s yet to crest.The drummer, composer, and progressive bandleader continually refines and renews an expression bonded to the lineage of Black music that fluoresces across Homeward Bound. Warmth of phrasing abounds as Blake layers a sound that’s at once relaxed and urgent. Alongside an innate ride cymbal, his melodic treatment of the drum kit reflects a generations old understanding of the instrument and allows his compositions to engage the myriad artists who bring them life.

Homeward Bound features Blake’s band Pentad, a quintet of musicians whose expressions inhabit that mystery of time and space. Pentad’s core trio is comprised of longtime collaborator and friend Dezron Douglas whose strong yet reflexive bass presence saturates each track, and acclaimed Cuban-born keyboardist David Virelles on piano, Rhodes and Minimoog. Blake’s Blue Note label mates ImmanuelWilkins and Joel Ross complete the multigenerational quintet on alto saxophone and vibraphone. Though distinct in their expressions, the rising star artists share a cooperative quality intrinsic to their improvising.

“The name represents us as five individuals coming together for a common cause: trying to make the most honest music as possible,” says Blake who assembled the band with the intention of composing for a fuller, more explicit chordal sound than his past projects have featured. The result is a wildly intuitive, tight sound that embraces spontaneity and relies on trust.

“I think the sound also comes from years of Dezron and David and me playing together, and the whole history of Immanuel and me knowing each other from the Philly days, and then Immanuel’s hookup with Joel.” Even Blake and Ross had their own hookup going before forming Pentad from a Jazz Gallery commission the leader received several years earlier. “There’s a bit of history with everybody in the group, so when we come to play together, it’s a unique band sound.”

Opening with a tender foundational gesture from Douglas, the album’s title track celebrates the short effervescent life of Ana Grace Marquez-Greene. Daughter of saxophonist Jimmy Greene and flautist Nelba Marquez-Greene, Ana Grace perished in the Sandy Hook tragedy nearly a decade ago. For Blake, who recalls the moment of her birth, Ana Grace’s time on earth resonates. “When little Ana was born, I remember what a blessing she was,” says Blake, who was on the road with Greene at the time in TomHarrell’s band. “She had such a lively presence. So when I heard she’d been taken away, it affected me and I started writing this tune.”

Reminiscent of a melody she might have hummed as she bounced into the room, “Homeward Bound (forAna Grace)” prompts joyous and contemplative trades between Ross and Wilkins, a luminescent solo from Virelles and a feature from Blake just as effervescent as the spirit it honors. “She was always singing,” says Blake, “any room she went in, she would just sing.”

Another of the album’s buoyant melodies surfaces on “Rivers & Parks.” Featuring solo contributions fromRoss, Wilkins, Virelles, and Douglas, respectively, the composition honors works by Sam Rivers and AaronParks. At his home in New Jersey, Blake had been playing Rivers’ “Cyclic Episode” and Parks’ “Hard-BoiledWonderland” on repeat when a melody of his own emerged. Later he realized all three tunes had in common their 16-bar form. “I didn’t even plan to write a tune like that,” he says. “I guess I was very inspired by listening to those two compositions.”

Throughout Homeward Bound, the artists tangle avenues along what’s grounded and what’s unbound.Wilkins and Blake spark an open dialogue at the start of Douglas original “Shakin’ the Biscuits,” playing off mood colors from Virelles. Laying down the ground rules at 45 seconds into the track, Douglas brings everyone into the groove. Virelles allows textural choices to influence where he takes the music, playing piano, Rhodes and minimoog at different moments.

Soul-cleansing and meditative, “Abiyoyo” reflects Blake’s take on the traditional South African folktale.The chart had been written in 6/8 but, for the recording, the leader was hearing — and feeling —something different. “I wanted it to be something you could feel almost as a lullaby,” he says. “I was hearing this slow 3, and immediately the rest of the band caught the vibe. This wasn’t a piece we were gonna burn out on solos. It was a tone poem.” That burner would happen later on. Blake introduces “LLL”in a swinging gesture of grace and conviction. Limelighting highest level interactivity among band members and solos from Virelles and Ross, the tune is a channel for the vibraphonist’s signature arcs and turns and high-velocity lyricism.

Aligned with his artistry, Blake’s arrangement of Joe Jackson’s “Steppin’ Out” bonds an iconic vamp and enduring melody with the drummer’s intuitive feel and phrasing as well as his harmonic instincts. “It’s one of my favorite songs,” he says. “That melody just plays itself.” The band’s treatment of the 1982 hit reveals critical homework on the part of its younger members. “The only people who were aware of the tune were me and Dezron [laughs],” says Blake. “But they really got inside it. Immanuel played his butt off. He went to some different places.”

HOMEWARD BOUND

The poignant title track “Homeward Bound (for Ana Grace),” which was released today, celebrates the short effervescent life of Ana Grace Marquez-Greene, the daughter of saxophonist Jimmy Greene and flutist Nelba Marquez-Greene who perished in the Sandy Hook tragedy nearly a decade ago. For Blake, who recalls the moment of her birth, Ana Grace’s time on earth resonates. “When little Ana was born, I remember what a blessing she was,” says Blake, who was on the road with Greene at the time in Tom Harrell’s band. “She had such a lively presence. So when I heard she’d been taken away, it affected me and I started writing this tune.”

Reminiscent of a melody Ana Grace might have hummed as she bounced into the room, “Homeward Bound (for AnaGrace)” prompts joyous and contemplative trades between Ross and Wilkins, a luminescent solo from Virelles and a feature from Blake just as effervescent as the spirit it honors. “She was always singing,” says Blake, “any room she went in, she would just sing.

Blake assembled Pentad with the intention of composing for a fuller, more chordal sound than his past projects have featured. The result is a wildly intuitive, tight sound that embraces spontaneity and relies on trust. “The name represents us as five individuals coming together for a common cause: trying to make the most honest music as possible,” he says. “I wanted to create a record where people would get inside my head. I want them to see the story I was trying to tell. That’s my hope.” Heralded by NPR Music as “the ultimate modernist,” the Philadelphia-raised artist has collaborated with Pharoah Sanders,Ravi Coltrane, Tom Harrell, Hans Glawischnig, Avishai Cohen, Donny McCaslin, Linda May Han Oh, Jaleel Shaw, ChrisPotter, Maria Schneider, Alex Sipiagin, Kris Davis and countless other distinctive voices. DownBeat once wrote, “It’s a testament to Blake’s abilities that he makes his presence felt in any context.” A frequent presence on Blue Note records over the past several years, Blake has contributed his strong, limber pulse and airy precision to multiple leader releases from Blue Note artists including Dr. Lonnie Smith’s Breathe (2021), All in My Mind (2018) and Evolution (2016) and KennyBarron’s Concentric Circles (2018), the latter whose trio Blake has been a vital member for nearly 15 years.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johnathan_Blake

Johnathan Blake

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Johnathan Blake, Oslo Jazz Festival 2018

Johnathan Blake (born on June 1, 1976, in Philadelphia) is an American jazz drummer.

Biography

Johnathan Blake is the son of jazz violinist John Blake Jr. He started playing the drums when he was ten; He gained his first experience in his hometown in the Lovett Hines Youth Ensemble. After graduating from George Washington High School, he studied jazz at William Paterson University with Rufus Reid, John Riley, Steve Wilson and Horacee Arnold. During this time he began to work as a professional musician, among other things in the Oliver Lake Big Band, with Roy Hargrove and David Sánchez. In 2006, he received the ASCAP Young Composers Award; the following year he completed his studies with a master's in composition at Rutgers University (studied with Ralph Bowen, Conrad Herwig and Stanley Cowell).[1]

His first recordings were made in 1996 by Norman Simmons; Blake then worked in the Mingus Big Band in the 2000s and appeared on their Grammy-nominated albums Tonight at Noon (2002) and I Am Three (2005). He also played with Ronnie Cuber, Russell Malone, Randy Brecker and Joe Locke, with whom he performed at JazzBaltica in 2009.

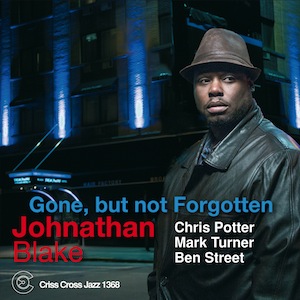

In 2012, Sunnyside Records released Blake's debut album The Eleventh Hour, which featured saxophonists Mark Turner and Jaleel Shaw.[2] With Thomas Maintz and Scott Colley, he presented the joint album Present, which was followed in 2014 by his album Gone, But not Forgotten for Criss Cross Jazz and in 2019, by his double album Trion (with his trio with Chris Potter and Linda Oh). His album Homeward Bound was released on Blue Note in 2021.

Blake recorded the album Brooklyn Jazz Session (2011) with musicians like Benjamin Koppel, Kenny Werner and Scott Colley. In 2018 he worked with Jonathan Kreisberg at Dr. Lonnie Smith's album All in My Mind (Blue Note). In 2019, he was a member of the Kálmán Oláh Quartet (with John Hébert and Tim Ries), and also in the Oded Tzur quartet. He can also be heard on recordings be Omer Avital, George Colligan, Wayne Escoffery, Tom Harrell, Brian Lynch, Donny McCaslin, Monday Michiru, Alex Sipiagin, Jack Walrath and Greg Abate (Magic Dance: The Music of Kenny Barron). In the field of jazz, Blake participated in 72 recording sessions between 1996 and 2020. [3]

External links

"Jonathan Blakes Website". johnathanblake.com. 2018-04-03.

Johnathan Blake at AllMusic

Johnathan Blake discography at Discogs

"Drummer Johnathan Blake | rhythm and grooves". web.archive.org. 2018-08-26. Retrieved 2021-12-10.

Johnathan Blake: Before & After

The drummer of prime pedigree loves his pockets

When the world was in a more social way, the sight of Johnathan Blake behind the drum kit was a sign of maximum support, comfort, and taste. It still is today, as we gather around our laptops to enjoy music online. Ask any of the notable bandleaders who’ve brought Blake onstage over the years, Pharoah Sanders, Tom Harrell, Ravi Coltrane, Kenny Barron, Maria Schneider, Q-Tip, and Dr. Lonnie Smith among them: His balance of drive and openness—locking down a pulse free of a locked-down feel, being propulsive without the push—is one of the subtler charms on the current scene. He also offers one of the more distinctive sights in modern jazz. Other than perhaps Antonio Sánchez, do any drummers position their cymbals lower or flatter? He’s a photographer’s dream, unobstructed from the waist up.

To fans who know Blake’s heritage, and to many followers on Facebook who are learning about it through copious posts filled with childhood photos, he’s to the jazz manor born. Son of violinist John Blake, Jr., he arrived in the U.S.A.’s bicentennial year, growing up in Philadelphia’s rich musical hotbed of the ’80s and ’90s and embraced by giants, literally; among his online throwback images are preteen Johnathan hugged by the likes of Elvin Jones, Joanne Brackeen, and others. In recent years, he has stepped out as a leader, bringing forth albums on a variety of labels—The Eleventh Hour (Sunnyside, 2012), Gone, But Not Forgotten (Criss Cross, 2014), and Trion (Giant Step Arts, 2018). A new recording being readied for Giant Step, Homeward Bound, features his latest group Pentad: saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins, pianist David Virelles, vibraphonist Joel Ross, and bassist Dezron Douglas.

In 2020, the world has changed, and Blake continues to rise to the challenges of the day, staying limber, writing music, performing online as often as he can. He chooses to look at the positive side of the lockdown: “It’s been kind of a joy to be able to wake up and not really have any set thing to do, to be home for a change, like I’m back in high school again. I haven’t had this much time off in years, so I’m trying to make the best of it. That’s all we can do.”

Blake is grateful too for the songwriting grant he recently received from the newly formed Jazz Coalition Commission Fund. “I appreciate Brice [Rosenbloom, Jazz Coalition founder with Gail Boyd and Danny Melnick] and everybody doing this. They selected around 50 musicians for this grant, to write a piece of music dealing with the times we’re living in right now and perform it. I had already started writing some music dealing with some of the people we lost because a lot were actually from my hometown.”

In late July after months at home, Blake performed at New York’s Jazz Gallery, whose director Rio Sakairi is doing her best to keep the scene alive, for a live stream with Ravi Coltrane’s “classic” quartet—back with Virelles and Douglas. “That was the first time playing since March. It was very emotional for me hitting those first notes. I was like, ‘Man, this feels really different.’ I was trying to dust off the cobwebs, a lot of Sloppy Joe Jones there, but I was having fun. It just felt good to play with some other people besides playing with Logic [the software, not the DJ]. It just felt great.”

This listening session was conducted online via Zoom with more than 50 people attending, some from as far away as South Africa. It was Blake’s first Before & After.

Listen to a Spotify playlist featuring most of the songs in this Before & After:

1. Aziza

“Sleepless Night” (Aziza, Dare2). Chris Potter, tenor saxophone; Lionel Loueke, guitar; Dave Holland, bass; Eric Harland, drums. Recorded in 2015.

BEFORE: All right. I think I got it. I know that’s Lionel [Loueke]. Even before he came in with the vocals I could tell. I’ve played a lot with him and there’s something he does with effects, like almost a slapping thing he does a lot with the guitar. I’ve always enjoyed hearing that. That sounds like Eric Harland on drums. There’s an attack Eric does that really sounds familiar to me, and also the way he tunes his snare is very unique. That’s Chris Potter, of course.

AFTER: Chris has a certain sound—I’ve played with him for many years so I can pretty much tell it’s him right away, and also Eric. He’s using some different cymbals that I haven’t heard him use in a while, so it took me a second, but as soon as he started playing the snare I was like, “Okay, that’s Harland.” I love his interaction between the snare and bass drum, the conversation he has.

Then Lionel has such a distinct sound on his instrument. I’ve watched him do some solo projects, which are always amazing, and about three or four years ago I was in St. Louis at the Bistro with Dr. Lonnie Smith and he was a special guest with us, with Jonathan Kreisberg. It was just amazing to have two guitars for those four nights, and to listen to the contrast of the two guitars.

I caught Aziza live at the Chicago Jazz Fest … no, no, it was in Europe. I can’t remember. Maybe Perugia [Umbria Jazz Festival] or something like. It was great. Dave gives each member the freedom to create. It’s a beautiful experience. I had the pleasure of working with him recently with Kenny Barron, and I love how he encourages the interaction. He doesn’t want you to just play time. He wants you to interact with everything that’s going around, creating some rhythmic tension or whatever. He’s such a sturdy player so you really feel free, like you can go anywhere.

I’ve noticed Dave’s smaller groups might just be three or four players, but it’ll feel like 10 people onstage.

Yeah. That’s what I loved about that quintet he used to have with Robin [Eubanks] and Chris [Potter] and Steve Nelson. It almost had a big-band feeling to it, and that speaks volumes to the way he composes—you can hear the bigger picture. With Dave, the composing and the playing all goes together. There’s no “I” in band, so in a band situation it has to be everybody that’s involved in the project. When you get great musicians together like these, you’re listening for that interaction, you’re wondering what’s the story they’re telling, what journey are they going to take us on. Everybody gets their chance to interject what they’re feeling. And if the leader is open enough, like Dave is, he just goes along with it and that’s what’s supposed to happen. He got these musicians because he knows how they play, he got them because he respects what they do on and off the bandstand.

2. Lee Morgan

“Beehive” (Live at the Lighthouse, Blue Note). Morgan, trumpet;

Bennie Maupin, tenor saxophone; Harold Mabern, piano; Jymie Merritt,

electric bass; Mickey Roker, drums. Recorded in 1970.

BEFORE: All right! Is that Live at the Lighthouse? I know this composition—it’s by Harold Mabern, “Beehive.” That’s a great record. That’s the history right there—one of my favorites. That’s Joe Henderson, right? Oh, okay, Bennie [Maupin]. I haven’t heard this in a while. I think I had that record on vinyl first before it came out on the boxed set. I wore this recording out.

Mickey [Roker] was my teacher and he has a very distinct sound on the instrument that never left him. I used to go see him when he used to play with Shirley Scott every week at Ortlieb’s Jazzhaus. He was one of the drummers while I was coming up in Philly who was still there, and he and Edgar Bateman and Bobby Durham were the three wise men that took me under their wings, and I was always grateful.

Mickey had this sound that he could get on the snare and I always used to bug him about it. I was like, “Man, how do you get that?” He would always call me “Little Blake” because he knew my dad—“Little Blake, you just gotta listen to the music.” I’d say, “No, that’s not it.” I would bug him, man. He kinda let me work it out, and that’s what a great teacher is supposed to do: They guide you but they want you to figure it out for yourself. Eventually I got to it. It’s still ingrained in my brain, stuck with me forever. He’s a master.

When I was going to William Paterson University, Harold Mabern was one of my ensemble teachers and I remember he brought in that tune, “Beehive.” He always talked about how he wrote it for Philly Joe [Jones] but never got a chance to record it with Philly. Whenever somebody would introduce me to a new tune I would try to see where it was first recorded, and study that original recording. I got used to listening to records all the way through. Now you can just push a button and skip around, but I always liked listening to the whole record. Then turn it over and listen to the B side.

Respecting the sequence—like putting together a set list for a gig.

Yeah, in a way it is. I feel like you get a glimpse in the person’s head, how they were thinking about the overall flow of the album. If you skip around, you just don’t know what the thinking was behind why they put this song where. Even now, if I’ve downloaded something on iTunes, I’ll listen through the whole record.

3. Christian McBride’s New Jawn

“Ke-Kelli Sketch” (Christian McBride’s New Jawn, Mack Avenue). Josh Evans, trumpet; Marcus Strickland, tenor saxophone; McBride, bass; Nasheet Waits, drums. Recorded in 2018.

BEFORE: Is that [Joe] Lovano? Is that Dave King? Something in the way that he’s attacking the drums reminds me of something Dave would do. That’s killin’. I like it. It’s funny, the hi-hats remind me of Tony [Williams] and the cymbals remind me of some stuff I’ve heard Andrew Cyrille do. You’re throwing me with this one, man. I love it, it’s amazing. It’s not a bass player record? It sounds like it is—it’s a bass-heavy record. It’s the overall sound, the first thing I hear is the bass, he like really gets the wood sound and you can almost hear the rosin on the bow. I love hearing that essence, the actual sound of the instrument.

I love the interaction too. I especially love the interaction with the bass and the drums. It reminds me of some other stuff I’ve heard—Gerald Cleaver, some stuff he does. I’m curious to see who it is.

AFTER: Really? Wow. I’ve never heard Christian play like that. It’s refreshing to hear him going there like that. He can go in the big house, so to speak. And Nasheet is always amazing—one of my favorites. I don’t know why I couldn’t recognize him. I’m not used to hearing Christian in this setting, so it kind of threw me. This is an amazing record. I’m thinking, let me investigate this a little more. I’ve seen this group play live a couple times at the Vanguard. They never disappoint, they always kill it.

I should have gotten Nasheet, though, although it also doesn’t sound like the usual cymbals he uses. He has like an old [Zildjian] K that he uses sometimes and it didn’t sound like that. This is his tune?

Nasheet pushes everybody in a different direction too, which is great. I like that he’s willing to … not force, but to interject certain things that will get people out of their comfort zone. I’ve seen him do that with Jason [Moran], of course, and other bands he’s been in, Scott Colley and people like that. He’s a few years older than me, so he was already on the scene when I got here. He’s like me a bit—growing up with his father on the jazz scene, always entrenched in the music. When I came to New York he was still playing with [saxophonist] Antonio Hart, then I think [pianist] Marc Cary had a trio with him and [bassist] Tarus [Mateen] early on. I always learn a lot when I go to see him play. He always stays true to himself as an artist, never wavers in how he plays, and you either come along or you don’t.

4. Terri Lyne Carrington + Social Science

“Pray the Gay Away” (Waiting Game, Motéma). Nicholas Payton,

trumpet; Morgan Guerin, tenor saxophone, EWI, bass, vocals; Matthew

Stevens, guitar, vocals; David France, Layth Sidiq, Mimi Rabson,

violins; Aaron Parks, synthesizers, vocals; Chris Fishman, Edmar Colón,

keyboards; Carrington, drums, percussion, vocals; Nêgah Santos,

percussion; Debo Ray, vocals; Brian “Raydar” Ellis, MC; Kassa Overall,

MC, turntables. Recorded in 2019.

BEFORE: That’s killin’. Is that Nate [Smith]? I liked the overall arrangement but I especially loved the pocket. It reminded me of how Nate plays grooves. He has a certain attack when he hits the drums, especially when he’s crashing on the cymbal. Always in the pocket, never lets the groove suffer. Hmmm. I’m not sure. I thought for a second it might be Chris [Dave]. Hold on. Let me try to figure this one out. I don’t know, is it the Drumhedz?

AFTER: Oh, it’s Terri. Well, that makes sense. She can play pocket like no other. Is this the new record, with Kassa? They did an [NPR] Tiny Desk concert recently and it was great. Terri’s one of my favorites—one of the ones that can play straight-ahead but also play the groove, and it always feels good. No hiccups in the playing, so to speak—such a complete player.

The very first time I saw her was when she was playing on The Arsenio Hall Show. I think the first time I met her she was playing with Herbie [Hancock] and that had to be in the mid-’90s. They were on tour and I got to see her in Barcelona. I was just in awe. I never want to bother somebody when they first come off the stage, but I just wanted to tell her how much I enjoyed her playing. It was like, “Yo, I’m a big fan.” [Laughs] A really brief conversation.

Recently we’ve gotten a bit closer. I guess it was last year Kenny Barron did a residency at SFJazz and the first night was different duos, with Regina Carter, Eddie Henderson, and Terri Lyne. I sat backstage and watched and then we got to talking afterwards. She’s an amazing player, and an amazing person too. I like that she’s also getting into the educational component of the music too, teaching at Berklee. It’s a different mindset when you have working artists that are also teachers. They can tell you exactly what it’s like to be on the road and what the overall vibe is.

It’s also interesting to see she’s surrounding herself with some up-and-coming musicians, and the message that’s in her music. That’s an important part of this music too. I think back to all the luminaries who came before when it wasn’t as easy to speak out as it is now, but still they weren’t afraid to do so—Billie [Holiday], Max [Roach], Abbey [Lincoln], Miles. They put that in their music, like Terri and others are still doing. It’s important to keep these conversations open. You have to because that’s the only way that change can come about. Enough is enough, and we have to make changes. Stuff can’t keep continuing to go along the way it’s been. Seeing more and more of that happening now in the music is a beautiful thing. It’s being led now by people like Terri, and especially by this younger generation.

5. Philly Joe Jones

“Gone” (Showcase, Riverside). Blue Mitchell, trumpet; Julian

Priester, trombone; Bill Barron, tenor saxophone; Pepper Adams, baritone

saxophone; Sonny Clark, piano; Jimmy Garrison, bass; Jones, drums.

Recorded in 1959.

BEFORE: [Immediately] Classic! [Shifts to mock understatement] It’s all right. If this is the best you got, whatever. [Laughs] What a great recording. I haven’t heard that in a long time. Of course, this is Philly … Philadelphia Joe Jones. Oh man, classic. It just speaks for itself. Everything he plays is just so in the pocket, it has this soulfulness to it. Every time I hear him, you can always tell this was a dance music. It’s like you can dance to his solos, man, it just feels so good every single time. Everything is just perfect. You can’t mistake that man. If I got that wrong, Kenny Washington would have disowned me. I know Kenny’s online here with us.

Philly was such a heavy presence even though he wasn’t in Philadelphia when I was coming up. He still set the bar really high for drummers in Philly, and continues to do so even after all these years of being gone. We’re all striving to get to that sound and overall vibe on the instrument, making people forget about their troubles.

I got to meet him one time when I was two years old and my father took me to see him. No, I don’t remember being two, but I think it was at this place called the Bijou Café in Philadelphia. There was another gentleman that played with him and with my father, the great pianist Sid Simmons. When I got a little older Sid would tell me stories about being on the road with Philly. He said he was a character, but was always really serious about the music. When it came time to hit, it was take-no-prisoners. That comes through on this recording. There’s also a video I love of Thelonious Monk and I don’t know who the drummer is playing with him. At one point Monk gets him off the drums and brings Philly on, who’s waiting in the wings, and he just kills it. He left nothing on there.

[Looks at image of Showcase LP] I still have that on vinyl too. Everything on it just … just makes you so happy, man. For me, that’s what music is supposed to do, it’s supposed to uplift and up-build. He just had a way of bringing the joy. Every time I hear him I remember why I wanted to start playing this instrument. Thank you, I needed that.

6. Nate Smith

“Paved” (Pocket Change, Waterbaby). Smith, drums. Recorded in 2018.

BEFORE: Where was that recorded at? A home studio, really? That sounds amazing. Is that Jamire [Williams]? I know he did a solo record and experimented with different drum kits and filters trying to get different sounds. I don’t know. It’s cool. It doesn’t speak to me in the same way when it’s played right after Philly Joe, but I dig it. I wasn’t ready for it, but let’s just go there. Wait, is that Nate? That’s the record called Pocket Change, right?

He’s a special dude. His pocket stuff is just unbelievable. I remember hearing him very early on with Betty Carter. He had a certain groove even when he was playing straight-ahead that was just unbelievable. Then I heard him later on one of his first gigs with Dave Holland—coming in after Billy Kilson had been in that band for ages, at least six years, which was not an easy thing to do. It was really interesting to hear what he was doing with the music, making it his own. He took it to some places that made Dave and the rest of the band play differently.

Then with his own band, with Fima [Ephron] and Jaleel [Shaw]. His writing is very creative and he never forsakes the groove and never forgets about the melody. I feel like sometimes when people are writing more in this vein they want to write something so complicated, and you don’t really have to do that, man. You want something that people can walk away remembering, singing what’s been written. For me, Nate always has a way of doing that. He writes some complex rhythmic stuff, some odd-meter stuff, but it’s always in a groove.

Nate’s amazing, and I got to experience that firsthand. We recorded a record together a few years back with a friend of mine, a trumpet player named Nabaté Isles [2018’s Eclectic Excursions], and there were a couple of tracks where we’re actually playing together. It was nice to have him right next to me, seeing his whole approach, how he attacks the snare. He has these deliberate moves that really make his sound consistent. He’s a monster. One of my favorites.

Have you been tempted to do a beats project like this?

I’m always into trying to find new colors with the set, so I am curious about getting into that vein a little more. But I want it to sound honest. I don’t want to sound like it’s forced. I’ve been taking my time and trying to experiment with different setups and presets and Logic, trying to figure out what I can do. For me, it’s a slow process. I’m really new to this type of thing, but it is interesting and I love hearing what can happen.

Gerald Cleaver just released a record experimenting with more electronic stuff and it’s killin’ [Signs, 577 Records, 2020]. At some point I would love to incorporate that into my playing. Originally Published

7. Billy Hart Quartet

“Teule’s Redemption” (One Is the Other, ECM). Mark Turner, tenor saxophone; Ethan Iverson, piano; Ben Street, bass; Hart, drums. Recorded in 2013.

BEFORE: Billy Hart. I know that sound immediately. It’s a combination of both cymbal and drums. There’s nobody that tunes his bass drum like that. From the tuning, to the tips of the sticks that he uses, the way he attacks the cymbal … very distinct. Is this from All Our Reasons or One Is the Other? They feature the same band, Mark [Turner] and Ethan [Iverson] and Ben Street. He’s another one that’s always had a distinct sound. He always has one foot in the present and one foot in history. You can hear the history of Max and all those players in his playing, but he’s also inspired by what’s around him now. He’s one of my favorites.

I watched one of his live streams from the Vanguard during lockdown, and I tuned in both days. The first night he played this solo, an intro to this tune that they closed the set with. He told a whole story but it was the way he brought it back, he started with this idea and when he came back after playing all this other stuff, he came back to it and it just completed the story. It had this clear beginning, middle, and end. I called him the next day, and said, “Yo, what was that? What did you do there?” Of course he’s not going to tell me. He was like, “Aw man, you know that stuff.” We stayed on the phone for two hours and I still didn’t get the answer but it was all right. I was there with him in that moment, so it was perfect.

He’s known me since I was about two years old so he’s like my uncle,

and I actually talked to him maybe a couple weeks ago for two hours on

so many different subjects, like him coming up in D.C. He talks about

that a lot. All his work with Jimmy Smith and the R&B scene. I’ll

think I got it under my belt and then I go and hear him and I’m like,

“Damn, I gotta go back to the drawing board.”

Jabali never gets old. I feel like he’s always growing as an artist, never comfortable, never remains stagnant. He’s pushing this music and challenging himself too. He doesn’t shy away from challenges.

8. Carlos Santana and Cindy Blackman Santana

“The Star-Spangled Banner” (pre-game ceremony at Game 2 of 2015 NBA Finals, YouTube video). Carlos Santana, electric guitar; Cindy Blackman Santana, drums. Recorded in 2015.

BEFORE: [The video performance ends with a back announcement identifying both players] Oh! You should have cut it out before that. That was great, though. Was that for a football game or something? Okay, NBA Finals. Was that the first or second year they did that?

AFTER: Incredible. Cindy’s a beast. I mean, I could tell that it was Carlos and the way she plays pocket is very distinctive too, very heavy with the floor tom and also on the bass drum. It kind of threw me for a minute because I’m not used to hearing them play duo.

I remember all those records that she did with Lenny [Kravitz] back in the day. I don’t know, there was always something about when she would play funk or rock, it was very bottom-heavy. I think she has a 16″ [kick drum] and a 14″ floor tom and she utilizes both quite a bit. It’s really funky—it almost reminds me of some stuff you would hear Zigaboo Modeliste play with the Meters. I loved it, man.

The spotlight’s really on Cindy, and Carlos plays it so straight.

He does, he does. It was nice to hear that he gave Cindy that room to breathe and to stretch out and she took full advantage of it. He doesn’t really do any variations with it, which is interesting. A lot of times when you hear “The Star-Spangled Banner” being played, you’re used to people taking so many liberties with that song. And on electric guitar, your mind always goes to the Hendrix version. It’s actually a beautiful melody so hearing it played it that way, you’re really able to put the words to the melody.

Carlos is another one that has a very distinct sound on his instrument. It’s really personal, and you can always tell it’s him. But this time it’s like he knows people have heard that song a million times. Even if he’s out in the forefront, he’s not thinking about himself, he’s thinking about the other people that are complementing him. It sounds great.

9. Andrew Cyrille Quartet

“Coltrane Time” (The Declaration of Musical Independence, ECM). Bill Frisell, guitar; Richard Teitelbaum, synthesizer; Ben Street, bass; Cyrille, drums. Recorded in 2016.

BEFORE: [Immediately] Andrew Cyrille. I

just know that sound, man. It’s funny the way the cats of a certain

generation, the way each tunes their drums is really unique to

themselves. The way he was playing the snare right in the beginning, I

was like, “Okay, that’s Andrew.” Is that with [Bill] Frisell? That’s a

great record. I have that one—I actually saw them at the Vanguard before

they recorded this. I love the palettes they create within the music. I

love that military thing Andrew does over that padding, a lot of

five-stroke rolls. Even the way he attacks the snare, like his first

attacks, you can hear the influence of Max, he’s a direct descendant,

and it’s amazing to hear how he’s taken those influences and shaped it

into his own. It’s also great to hear how his playing changed over time,

from playing with Cecil Taylor in the ’60s. There’s a video from ’68 or

around then, and you can hear how he was evolving back then into who he

is now.

I did a discussion with Andrew a few years back for Winter Jazzfest when he was artist-in-residence, at the New School—I remember I talked about how when I listen to him I hear the influences of Max, but what was interesting is that he said he didn’t hang out with Max that much, he said he hung more with Philly Joe and Elvin. They were more inviting to him when he was coming up. I was surprised, but it showed me just because people are listening to each other doesn’t mean they’re going to be tight.

10. Earl Van Dyke

“Ode to Benny B.” (The Motown Sound, Motown). Stevie Wonder,

harmonica; Robert White, Eddie Willis, guitars; Earl Van Dyke, electric

piano; James Jamerson, bass; Uriel Jones, drums; Jack Ashford or Eddie

Bongo, percussion. Recorded in 1969.

BEFORE: What year was that recorded? It’s funny because I don’t know what it sounds like for you, but the recording for me is a little weird, like the balance is off for me. Is that Idris [Muhammad]? The way he’s playing the groove reminds me of something he would do. He’s coming from an R&B place. This one throws me.

It also reminds me of a band Ed Thigpen had in the ’70s when he was playing more pocket stuff. The harmonica player reminded me of Stevie [Wonder]. Wait, who’s that on bass? Is that [James] Jamerson? Did this come out on Motown?

AFTER: Wow. “Ode to Benny B.”—that’s for Benny Benjamin. Am I a fan? Are you kidding me? He’s on all the iconic Motown recordings. He played all those famous pickups that open up all the hits, and he knew how to find the pocket in anything he played. I read it or saw it somewhere that a lot of times the Motown session guys would defer to him to find the correct tempo of a tune, where it laid the best, where it made it feel good, and so he’d kick off the tune. He’s definitely one of my favorites.

11. John Coltrane

“Saturn” (Interstellar Space, Impulse!). Coltrane, tenor saxophone; Rashied Ali, drums. Recorded in 1967.

BEFORE: [Immediately] Rashied. It’s a duo with him and Trane, something on Interstellar Space. What a great record. I knew it was him right before Trane came in. He had this feel that sounded just like him. I love that period of Trane too, but it sometimes gets overlooked. There’s some really beautiful moments after Elvin [Jones] and McCoy [Tyner] left, and what Jimmy [Garrison] and Rashied got to was really special. Like that live from Temple University recording [Offering, Impulse!/Resonance], just the way they played “Naima,” Rashied flowing over it is just unbelievable. You talk about stretching the bar line, man, it’s in his rearview mirror! [Laughs] It’s just amazing what he was hearing, and how he was making Trane play too. It just takes it to a whole new level for me every time I hear it.

I first met Rashied in Philly. There was an outdoor festival there and after he played I followed him around, stalked him a bit. [Laughs] Another time, I want to say it was at the Knitting Factory, we had a chance to sit down and chat for a while. He was a very humble person, a very positive person too. I had one question I always wanted to ask him, and I did—what was he thinking about when he was playing with Trane, what was going through his head? He said he was thinking about colors, oranges and blues and things like that. So it wasn’t so much coming from a rhythmic aspect, he was thinking more in terms of trying to match the colors that he was seeing. I don’t know how that translates to the drum kit, but it was really interesting to hear him articulate it in that way. It’s funny because when you talked to Elvin about playing with Trane, he felt it more as a spiritual thing, while Rashied talked about colors and not necessarily feeling the spirit. I’m sure that was in there for both [of them] in some way, just they felt it differently.

12. Ghost-Note

“Pace Maker” (Swagism, Ropeadope). Jonathan Mones, Sylvester

Uzoma Onyejiaka II, saxophones; Nigel Hall, Bobby Ray Sparks, keyboards;

Anthony “A.J.” Brown, Dwayne “MonoNeon” Thomas, Jr., basses; Robert

“Sput” Searight, drums; Nate Werth, percussion. Recorded in 2018.

BEFORE: Oh man, that’s another one that’s killin’. This reminds me of this band from Chicago, Sabertooth. Do you know them? Is it a group—it’s not Galactic? I liked his pocket, and I loved the groove. It’s not something I would listen to every day because it’s not my go-to vibe. I listen more to stuff from the ’70s like Stevie, the Meters, Sly and the Family Stone. But I appreciate this sound too and I do listen to it sometimes. Is that Larnell Lewis, with Snarky Puppy?

You’re in the right neighborhood, for sure.

AFTER: Ghost-Note! That’s a talented group with MonoNeon, and it’s definitely coming out of the Snarky Puppy vein, which is nice. I love Sput, he’s a bad dude. Before lockdown Ghost-Note were doing a few of those Zildjian Days [live events sponsored by the cymbal manufacturer], they were like the house band. Now that I have time, I’ve been watching a lot of videos of them. I just watched one last night with this young cat, JD Beck, ridiculous. I saw Sput right before he left Snarky at the Monterey Jazz Festival. There’s a picture somewhere of four or five of us drummers, Jamison Ross, Sput, Justin Faulkner, Otis Brown, myself, all together in the lobby while we were waiting to check into the hotel. Another road moment.

Thanks for doing this, Johnathan—I hope it wasn’t too painful.

No, I had a ball. I like the pain sometimes. Originally Published

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER:

Ashley Kahn is a Grammy-winning American music historian, journalist, producer, and professor. He teaches at New York University’s Clive Davis Institute for Recorded Music, and has written books on two legendary recordings—Kind of Blue by Miles Davis and A Love Supreme by John Coltrane—as well as one book on a legendary record label: The House That Trane Built: The Story of Impulse Records. He also co-authored the Carlos Santana autobiography The Universal Tone, and edited Rolling Stone: The Seventies, a 70-essay overview of that pivotal decade.

https://downbeat.com/news/detail/johnathan-blake-always-has-been-focused-on-rhythm

Johnathan Blake Always Has Been ‘Focused on Rhythm’

Johnathan Blake takes musical cues from his late father, John Blake Jr., a violinist who performed with McCoy Tyner and Archie Shepp. (Photo: Michael Jackson)

It’s a biting-cold January day in Manhattan.

The wind howls around corners and between the buildings with enough force, seemingly, to peel your skin off. Five stories up from the street, though, there’s enough heat coming off the Jazz Gallery’s stage to warm the whole block.

Drummer Johnathan Blake is guiding a student, a young man in his twenties, through a Thelonious Monk tune, showing him how to be expressive while maintaining the solid swing of the legendary pianist’s era. The student takes a turn at the kit, and then stands up at his teacher’s signal. Blake, a tall, stocky player, moves to the drum throne and offers a demonstration of what he’s looking for: a slow, rumbling shuffle beat that seems to wander and explore, but never goes fully off the path. The student nods thoughtfully, absorbing it all.

The lesson ends, and Blake descends from the stage, sitting at one of the Jazz Gallery’s small tables, a calm smile on his face. A 42-year-old Philadelphia native, he’s the son of John Blake Jr. (1947–2014), a violinist who worked with McCoy Tyner, Cecil McBee, Archie Shepp and others, and made a string of albums as a leader, beginning in 1984.

“My first exposure to live music was through my father, of course,” Blake recalled. “When I was born, my dad was playing with Grover Washington Jr., and Grover was using a drummer by the name of Pete Vincent, a great drummer from Philly. I was really young, 1 or 2 years old, but my parents said when the music started I would just lock in. I was in a trance, nothing could break my attention, and I was always focused on rhythm.”

Despite that, Blake followed in his father’s footsteps at first, picking up the violin at 3 and studying at home, then at Settlement Music School, an organization with multiple branches throughout Philadelphia. It wasn’t until fifth grade that he became a drummer in his elementary school band. By the time he was a teenager, Blake was gigging and sitting in at local jam sessions, and connecting with as many elders as possible. He’d also added another instrument to his arsenal.

“When my dad saw that I was really gravitating to the drums, he made it a point to tell me, ‘All right, if you’re gonna play the drums, I need you to also learn about the piano,’” he said. “So, I started taking piano lessons at 11 or 12. I never really felt that I was great at it, but I could figure out chords and read. I write at the piano; I have keyboards sometimes, and I use them to figure out chords. Sometimes, I’ll sing into my phone—I’ll sing an excerpt or a piece of something that enters my head, and later on, when I have time to sit at the piano I’ll try to flesh it out. I’ll play the melody and try to figure out some chords that go with it.”

Johnathan Blake -- "One for Honor"

Blake enrolled in the jazz program at William Paterson University and later earned his master’s degree in composition from Rutgers University, where he studied with Stanley Cowell. The pianist was able to pull Blake out of a compositional rut by setting challenges for him. Each week, the drummer had to compose a piece for piano using a particular set of parameters, like making the left and right hands play patterns that were a mirror image of each other. “I composed nine or 10 tunes, not that I’d play all of them publicly,” he chuckled, “but it did get me started writing again and flushing out those ideas that I couldn’t get out.”

But it was a gig Blake landed in his late teens that put him on the New York jazz scene’s radar. He became the drummer for the Mingus Big Band, which played every week at Fez, a small room beneath Time Café in Greenwich Village. Blake found it a thrill, as well as a major learning experience.

“When I started getting inside that music, it opened up a whole new world for me. I really learned how the drums are supposed to function in a band. You’re talking about 15 other guys, so you have to learn how to push the band. ... When [the arrangement featured] a soloist, I started thinking about it like a quartet was inside the big band, and really trying to focus on how the soloist was going to shape his solo.”

Blake first encountered saxophonist Chris Potter in the big band, and they’ve continued to work together—Potter is on Blake’s 2014 album, Gone But Not Forgotten (Criss Cross Jazz), and his new release, the live two-CD set Trion (Giant Step Arts). “He had been playing with the band for a couple of years before I joined, and I thought, ‘This dude is special, the way he’s hearing chords and how he’s playing off the harmony,’” Blake recalled. “He really had a unique approach, even back then. It was coming out of Michael Brecker and Joe Lovano and Trane, so he was still developing his own sound, so to speak, but it was really fascinating to hear him.”

“The core of what makes Johnathan great is the depth of his jazz swing feeling,” Potter said. “He literally grew up in it, and you can tell that he feels it and he lives it with his entire self. His ride cymbal beat, the way he approaches it, just feels right—there’s no way you can’t connect with that.”

The Mingus gig led to a unique opportunity for Blake in 2001, when he met hip-hop icon Q-Tip, then breaking out as a solo artist after achieving success with A Tribe Called Quest. The Mingus Big Band’s weekly performances were routinely packed and attracted a crowd of celebrities and other musicians: Members of Metallica or rapper Mos Def might show up to check out the music. “The first time I met [Q-Tip],” Blake recalled, “he was there with Robert De Niro, and he called me over to his table.” The rapper was looking to move in a new direction, and he needed a creative partner. “He was like, ‘I have this idea of doing a live band with me emceeing.’ It was organic, ’cause he was trying to figure it out himself.”

Blake assembled a band that included some of his fellow students and some well-known jazz names, including alto saxophonist Kenny Garrett and guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel. “We kind of did an audition at my place, and he dug the musicians I put together. We grooved out on some stuff and Q-Tip dug the way we played together, so we would go to his house and start rehearsing. He didn’t have any music, so we would come up with ideas and start recording.”

The resulting album, Kamaal The Abstract, was rejected by Arista Records and sat on the shelf until 2009, when it was released by Jive/Battery. “The timing was a little weird,” Blake recalled. “[Q-Tip] had just put his first record out as a leader [1999’s Amplified], so the label was saying, ‘We can’t put out a record with you singing and a live band. We’d have to change your whole fan base.’”

Since then, Blake has become one of the most in-demand drummers around. He regularly works with trumpeter Tom Harrell, pianist Kenny Barron and organist Dr. Lonnie Smith, among others. He’s also a member of the band the Black Art Jazz Collective. Each setting demands something different, but it’s a testament to Blake’s abilities that he makes his presence felt in any context.

“With Doc, he’s all about the groove,” the drummer said. “Whether we’re playing straightahead or more funk and r&b stuff, he wants that pocket to remain there. And he wants it to be full—he wants it to sound like a big band almost, even if it’s a trio. So, some of the challenges for me [are] how to make that band sound really full without necessarily overpowering it, but still complementing guitar and organ. He’s not so much about chops or anything. He really wants it to be about the groove and finding the pocket, so for me, it took editing some of my own way of playing and thinking to really blend in, and I like those kind of challenges. I like to remain true to myself, but give the leader what he wants out of the band.”

With Barron, Blake’s role is very different—more engine than foundation. “Kenny doesn’t really say much at all. I think I can count on one hand the number of times we’ve rehearsed,” he said with a laugh. “One of the things I’ve learned from being in his band all these years is really pacing myself, and really telling a story. Kenny’s 75 now, so there’s an energy that a younger musician brings that an older musician might not bring, that he looks for. Because he has to play off that. He needs that to give him the fuel to play. If it’s somebody that’s just gonna be as relaxed as him, it’s not gonna work,” he said, laughing again. “He didn’t want me to come in and play all my bebop licks that I studied. He could get somebody that grew up in that tradition and be more authentic. He wanted me to stretch out and play how I normally play and just give him energy.”

As a leader, Blake prefers to let music marinate on the bandstand before it’s committed to tape—another lesson he learned from his father. “Right after my father passed, I was helping my mother clean out the house, and he had kept an old calendar and I found it. One of the first things he did when he joined McCoy Tyner’s band was, he went out on tour for what seemed like a month in Japan. This was summer of ’79 or something. When they came back, that’s when they recorded [Horizon, on which Blake’s violin and compositions are featured]. They had been playing night after night; when they went into the studio, he said it just felt so natural. It was almost like playing another show.”

Blake chose the title of his 2012 debut, The Eleventh Hour (Sunnyside), because he’d waited so long to record it, playing its tunes in public until the band had them down cold. His second release, though, came together quickly. Gone But Not Forgotten was recorded after a makeshift performance at the Jazz Gallery. Blake was asked to put a band together to cover a cancellation, and he recruited Potter, saxophonist Mark Turner (who’d played on The Eleventh Hour) and bassist Ben Street.

“I’ve always been a huge fan of Mark’s, and saxophone players don’t always get a chance to play together,” Potter recalled, “so that was nice to get that experience, to feel like you’re bouncing ideas off him while he’s actually standing next to you.”

Trion showcases Blake in a trio with Potter and bassist Linda May Han Oh, and was recorded at the Jazz Gallery by photographer, recording engineer and Giant Step Arts founder Jimmy Katz, a frequent DownBeat contributor.

The new album includes four Blake compositions, a version of his father’s “Blue Heart,” two by Potter, one by Oh, a version of Charlie Parker’s “Relaxin’ At Camarillo” and a 17-minute take on The Police’s “Synchronicity I,” which Potter and Blake have played together on tour. “It was a great opener [live] and a way to engage people, ’cause if you listen closely you’ll recognize it [and say] ‘Now I’m engaged, now I’m in a trance, now I want to see what they’re gonna do next.’”

While many pieces are muscular and hard-swinging, verging on free at times, Oh’s “Trope” is a throbbing mood piece that begins in near silence. “For me, that particular tune was something a little mysterious,” Oh said. “The way I wrote it was, the melody’s relatively simple, but it starts super low on the tenor, and then it has some other twists and turns, but it’s a simple, relatively open tune. They did such a great job with it—everyone was super sensitive with it.

“I can’t remember the first time I played with Johnathan, but I’ve played with him in quite a few contexts—including with Kenny Barron’s trio on various gigs and in slightly augmented versions of that—as well as with Dave Douglas and some other musicians,” Oh continued. “[Blake] has such an incredible feel—a beautiful, wide beat, but the snap to his playing is just incredible. It’s exciting to play with, super malleable but such a strong vibe. And Chris, he’s out of this world, such an incredible musician—incredible ears, but so quick. It was a great experience.”

Blake expressed a sense of astonishment at Giant Step Arts’ support of his new work: “Jimmy is really encouraging us to make this artistic statement—he really wants us to showcase our music. Record companies don’t want you to do that all the time, and people producing records don’t want you to do that—they want you to play tunes that everybody knows, and they don’t want to hear your original music. So, to have somebody give us so much space to do what we want to do was very special.” DB

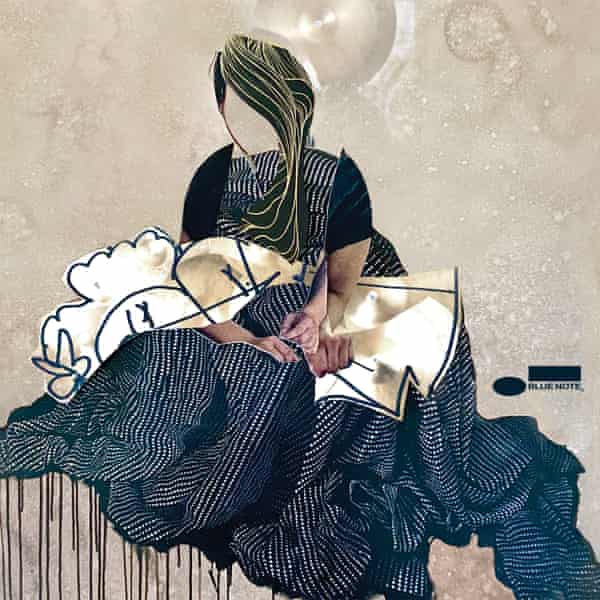

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2021/nov/05/johnathan-blake-homeward-bound-review-blue-note

Johnathan Blake: Homeward Bound review – virtuosi jazz unit scorch and shimmer

(Blue Note)

Drummer

Blake joins with Dezon Douglas, Immanuel Wilkins, Joel Ross and David

Virelles to create enthralling post-bop, soul jazz and Coltraneian pop

In Philadelphia in the late 1970s, a two-year-old Johnathan Blake used to be wheeled to his jazz violinist father John Blake’s gigs with saxophonist Grover Washington – where he would sit entranced by the sight, sound and rhythms of the band’s powerful Philly drummer Pete Vinson. Those memories would help to turn Blake into one of the most creatively supportive drummers of recent times, whose perceptive power has been embraced by heavyweights from the Mingus Big Band, Q-Tip and Dr Lonnie Smith, to post-bop innovators Tom Harrell and Maria Schneider.

Homeward Bound is Blake’s exhilarating debut for the Blue Note label. Pentad, his new quintet, is a contemporary dream-band lineup with longtime bass partner Dezron Douglas, and three acclaimed young virtuosi in alto saxist and fellow-Philadelphian Immanuel Wilkins, vibraphonist Joel Ross, and the Cuba-born global jazz keyboardist David Virelles.

Blake’s ability to float elusively around a groove while implying an emphatic snap that’s felt rather than heard is the constant undertow to this intricate but always open music. The title track emerges from a long-toned sax-led sway to become an enthralling jam, with Wilkins and Ross swapping warmly intricate lines, and Virelles breaking out into typically clipped, concise figures and glistening double-time streams. The soul-jazzy Shakin’ the Biscuits sets the saxophonist blurting exclamatory sounds against a synth-playing Virelles’ shimmery chords, the beautiful South African lullaby Abiyoyo dreamily unfolds over Blake’s lazily handclap-like pulse, and LLL is a contrastingly breakneck postbop sprint. The standout is the quintet’s scorching account of the Joe Jackson night-on-the-town classic Steppin’ Out – double-takingly turning from a respectful nod to an earworm pop hit into an anthemically roaring Coltranesque sermon.

https://www.johnathanblake.com/

https://www.johnathanblake.com/about

Johnathan Blake, one of the most accomplished drummers of his generation, has also proven himself a complete and endlessly versatile musician. Blake’s gift for composition and band leading reflects years of live and studio experience across the aesthetic spectrum. Heralded by NPR Music as “the ultimate modernist,” he has collaborated with Pharoah Sanders, Ravi Coltrane, Tom Harrell, Hans Glawischnig, Avishai Cohen, Donny McCaslin, Linda May Han Oh, Jaleel Shaw, Chris Potter, Maria Schneider, Alex Sipiagin, Kris Davis and countless other distinctive voices. DownBeat once wrote, “It’s a testament to Blake’s abilities that he makes his presence felt in any context.” A frequent presence on Blue Note records over the past several years, Blake has contributed his strong, limber pulse and airy precision to multiple leader releases from Blue Note artists including Dr. Lonnie Smith’s Breathe (2021), All in My Mind (2018) and Evolution (2016) and Kenny Barron’s Concentric Circles (2018), the latter whose trio Blake has been a vital member for nearly 15 years.

Born in Philadelphia in 1976, Blake is the son of renowned jazz violinist John Blake, Jr. — himself a stylistic chameleon and an important ongoing influence. After beginning on drums at age 10, Johnathan gained his first performing experience with the Lovett Hines Youth Ensemble, led by the renowned Philly jazz educator. It was during this period, at Hines’s urging, that Blake began to compose his own music. Later he worked with saxophonist Robert Landham in a youth jazz ensemble at Settlement Music School. Blake graduated from George Washington High School and went on to attend the highly respected jazz program at William Paterson University, where he studied with Rufus Reid, John Riley, Steve Wilson and Horace Arnold. At this time Blake also began working professionally with the Oliver Lake Big Band, Roy Hargrove and David Sanchez. In 2006 he was recognized with an ASCAP Young Jazz Composers Award, and in 2007 he earned his Masters from Rutgers University, focusing on composition. He studied with the likes of Ralph Bowen, Conrad Herwig and Stanley Cowell. Deeply aware of Philadelphia’s role as a historical nerve center of American music, Blake has immersed himself in the city’s storied legacy — not just jazz but also soul, R&B and hip-hop. In many ways he’s an heir to Philadelphia drum masters such as Philly Joe Jones, Bobby Durham, Mickey Roker and Edgar Bateman, not to mention younger mentors including Byron Landham, Leon Jordan and Ralph Peterson, Jr..

Johnathan Blake's debut release on Blue Note Records signals shifting tides for a career that’s yet to crest.The drummer, composer, and progressive bandleader continually refines and renews an expression bonded to the lineage of Black music that fluoresces across Homeward Bound. Warmth of phrasing abounds as Blake layers a sound that’s at once relaxed and urgent. Alongside an innate ride cymbal, his melodic treatment of the drum kit reflects a generations old understanding of the instrument and allows his compositions to engage the myriad artists who bring them life.

Homeward Bound features Blake’s band Pentad, a quintet of musicians whose expressions inhabit that mystery of time and space. Pentad’s core trio is comprised of longtime collaborator and friend Dezron Douglas whose strong yet reflexive bass presence saturates each track, and acclaimed Cuban-born keyboardist David Virelles on piano, Rhodes and Minimoog. Blake’s Blue Note label mates ImmanuelWilkins and Joel Ross complete the multigenerational quintet on alto saxophone and vibraphone. Though distinct in their expressions, the rising star artists share a cooperative quality intrinsic to their improvising.

“The name represents us as five individuals coming together for a common cause: trying to make the most honest music as possible,” says Blake who assembled the band with the intention of composing for a fuller, more explicit chordal sound than his past projects have featured. The result is a wildly intuitive, tight sound that embraces spontaneity and relies on trust.

“I think the sound also comes from years of Dezron and David and me playing together, and the whole history of Immanuel and me knowing each other from the Philly days, and then Immanuel’s hookup with Joel.” Even Blake and Ross had their own hookup going before forming Pentad from a Jazz Gallery commission the leader received several years earlier. “There’s a bit of history with everybody in the group, so when we come to play together, it’s a unique band sound.”

Opening with a tender foundational gesture from Douglas, the album’s title track celebrates the short effervescent life of Ana Grace Marquez-Greene. Daughter of saxophonist Jimmy Greene and flautist Nelba Marquez-Greene, Ana Grace perished in the Sandy Hook tragedy nearly a decade ago. For Blake, who recalls the moment of her birth, Ana Grace’s time on earth resonates. “When little Ana was born, I remember what a blessing she was,” says Blake, who was on the road with Greene at the time in TomHarrell’s band. “She had such a lively presence. So when I heard she’d been taken away, it affected me and I started writing this tune.”

Reminiscent of a melody she might have hummed as she bounced into the room, “Homeward Bound (forAna Grace)” prompts joyous and contemplative trades between Ross and Wilkins, a luminescent solo from Virelles and a feature from Blake just as effervescent as the spirit it honors. “She was always singing,” says Blake, “any room she went in, she would just sing.”

Another of the album’s buoyant melodies surfaces on “Rivers & Parks.” Featuring solo contributions fromRoss, Wilkins, Virelles, and Douglas, respectively, the composition honors works by Sam Rivers and AaronParks. At his home in New Jersey, Blake had been playing Rivers’ “Cyclic Episode” and Parks’ “Hard-BoiledWonderland” on repeat when a melody of his own emerged. Later he realized all three tunes had in common their 16-bar form. “I didn’t even plan to write a tune like that,” he says. “I guess I was very inspired by listening to those two compositions.”

Throughout Homeward Bound, the artists tangle avenues along what’s grounded and what’s unbound.Wilkins and Blake spark an open dialogue at the start of Douglas original “Shakin’ the Biscuits,” playing off mood colors from Virelles. Laying down the ground rules at 45 seconds into the track, Douglas brings everyone into the groove. Virelles allows textural choices to influence where he takes the music, playing piano, Rhodes and minimoog at different moments.

Soul-cleansing and meditative, “Abiyoyo” reflects Blake’s take on the traditional South African folktale.The chart had been written in 6/8 but, for the recording, the leader was hearing — and feeling —something different. “I wanted it to be something you could feel almost as a lullaby,” he says. “I was hearing this slow 3, and immediately the rest of the band caught the vibe. This wasn’t a piece we were gonna burn out on solos. It was a tone poem.” That burner would happen later on. Blake introduces “LLL”in a swinging gesture of grace and conviction. Limelighting highest level interactivity among band members and solos from Virelles and Ross, the tune is a channel for the vibraphonist’s signature arcs and turns and high-velocity lyricism.

Aligned with his artistry, Blake’s arrangement of Joe Jackson’s “Steppin’ Out” bonds an iconic vamp and enduring melody with the drummer’s intuitive feel and phrasing as well as his harmonic instincts. “It’s one of my favorite songs,” he says. “That melody just plays itself.” The band’s treatment of the 1982 hit reveals critical homework on the part of its younger members. “The only people who were aware of the tune were me and Dezron [laughs],” says Blake. “But they really got inside it. Immanuel played his butt off. He went to some different places.”

Above all else, Homeward Bound is a narrative celebration of life and legacy. “I wanted to create a record where people would get inside my head,” says Blake. “I want them to see the story I was trying to tell.That’s my hope.”

EQUIPMENT

Yamaha Absolute Maple :

18"x14"-Bass Drum with mount for Rack Toms

Coated Drum Head on Front of the Drum, Clear Head on Back of the Drum

NO HOLE IN BASS DRUM

16"x14"-Floor Tom with legs

NOT MOUNTED ON CYMBAL STAND

14"x14"-Floor Tom with legs

NOT MOUNTED ON CYMBAL STAND

(2) 14"x5 1/2" Snare Drum

12"x8" Rack Tom

Mounted on Bass Drum

NOT MOUNTED ON CYMBAL STAND

10"x8" Rack Tom

Mounted on Bass Drum

NOT MOUNTED ON CYMBAL STAND

4 Cymbal Stands (2 Straight Stands + 2 Boom Stands)

1 Yamaha HI-Hat Stand

1 Spiral Drum Throne

1 Yamaha Snare Drum Stand

1 Yamaha Bass Drum Pedal

http://westviewnews.org/2019/12/01/johnathan-blakes-explosive-debut-as-bandleader-at-the-village-vanguard/gcapsis/

Johnathan Blake’s Explosive Debut as Bandleader at the Village Vanguard

by Karen Rempel

Johnathan Blake with the Tom Harrell Infinity Band at Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola in November. Tom is standing at the left while a surprise guest trombonist takes the stage. Check out the gorgeous color of Johnathan’s shirt, reflected in the window, and the low rise of the high hats on Johnathan’s kit. Photo by Karen Rempel.

I first saw Johnathan Blake at the Village Vanguard in October 2015, where he was playing drums with Ravi Coltrane’s quartet. I was completely blown away by the intensity of his performance, and by the unique percussion elements he added. His dominance as a drummer was evident even to the neophyte I was at the time. I went backstage to meet him, and we became friends at once. When I brought my mother to see him play with Ravi at the Vanguard in October 2018, Johnathan sat down to chat with my mom after the first set and delayed the start of the second set to talk to her. She was enamored of his kindness and graciousness.

I am a big fan of Johnathan’s, and catch his playing whenever I can. Most recently, I saw him at Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola on November 10th with the Tom Harrell Infinity Band. He was incredible on this night. His complex rhythms sounded like he was playing multiple instruments simultaneously, laying a carpet of notes under, over, and through everything. He told me some wonderful news after the show, which is that he will be headlining for the first time in New York, as Johnathan Blake and Pentad, December 3 to 8, 2019 at the Vanguard. If you like jazz, you must check him out in this lineup.

Johnathan Blake has played with the greats—New York’s favorite bandleaders from Ravi Coltrane to Maria Schneider and other top ensembles. Johnathan has laid down the foundation and set the mood for all the great stalwarts in town. He was a member for years in the Tom Harrell Quintet and the Kenny Barron Trio. His bassist pal Dezron Douglas and pianist David Virelles will be playing with him for his headlining gig at the Vanguard, and I can’t wait to see these jazzcats together on stage again. Other members of Pentad include Immanuel Wilkins on alto sax, Joel Ross on vibraphone, and Kris Davis on piano on the weekend.

Johnathan has toured the globe for many years and is truly a world-class, internationally renowned beat-maker. A Grammy-nominated drummer and composer, Johnathan is no light-weight. His discography stretches back to 1996, with his first headlining album, The Eleventh Hour, in 2012, a second CD in 2014, and a new release this year, Trion, featuring Chris Potter and Linda May Han Oh.

Johnathan began playing violin at age three under his violinist father’s guidance, but he never felt at home with the instrument. When he was 10 years old, he scored perfectly on a music aptitude test and a visiting music teacher allowed him to choose an instrument. Without hesitation, Johnathan picked the drum set. We are glad he did!

Johnathan inspired this recording at Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola in December, 2015, New York Love Affair #19. You can also check out his website for many more excerpts of his music.

https://www.bluenote.com/johnathan-blake-makes-his-blue-note-debut-with-homeward-bound/

September 10, 2021

Homeward Bound—the remarkable Blue Note Records debut by drummer, composer, and bandleader Johnathan Blake—signals shifting tides for a career that’s yet to crest. The album, which will be released on October 29, is a celebration of life and legacy featuring Blake’s quintet Pentad with alto saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins, vibraphonist Joel Ross, keyboardist David Virelles, and bassist Dezron Douglas.

The poignant title track “Homeward Bound (for Ana Grace),” which was released today, celebrates the short effervescent life of Ana Grace Marquez-Greene, the daughter of saxophonist Jimmy Greene and flutist Nelba Marquez-Greene who perished in the Sandy Hook tragedy nearly a decade ago. For Blake, who recalls the moment of her birth, Ana Grace’s time on earth resonates. “When little Ana was born, I remember what a blessing she was,” says Blake, who was on the road with Greene at the time in Tom Harrell’s band. “She had such a lively presence. So when I heard she’d been taken away, it affected me and I started writing this tune.”

Reminiscent of a melody Ana Grace might have hummed as she bounced into the room, “Homeward Bound (for Ana Grace)” prompts joyous and contemplative trades between Ross and Wilkins, a luminescent solo from Virelles and a feature from Blake just as effervescent as the spirit it honors. “She was always singing,” says Blake, “any room she went in, she would just sing.”

Blake assembled Pentad with the intention of composing for a fuller, more chordal sound than his past projects have featured. The result is a wildly intuitive, tight sound that embraces spontaneity and relies on trust. “The name represents us as five individuals coming together for a common cause: trying to make the most honest music as possible,” he says. “I wanted to create a record where people would get inside my head. I want them to see the story I was trying to tell. That’s my hope.”

Heralded by NPR Music as “the ultimate modernist,” the Philadelphia-raised artist has collaborated with Pharoah Sanders, Ravi Coltrane, Tom Harrell, Hans Glawischnig, Avishai Cohen, Donny McCaslin, Linda May Han Oh, Jaleel Shaw, Chris Potter, Maria Schneider, Alex Sipiagin, Kris Davis and countless other distinctive voices. DownBeat once wrote, “It’s a testament to Blake’s abilities that he makes his presence felt in any context.” A frequent presence on Blue Note records over the past several years, Blake has contributed his strong, limber pulse and airy precision to multiple leader releases from Blue Note artists including Dr. Lonnie Smith’s Breathe (2021), All in My Mind (2018) and Evolution (2016) and Kenny Barron’s Concentric Circles (2018), the latter whose trio Blake has been a vital member for nearly 15 years.

Firm Roots