SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2021

VOLUME TEN NUMBER THREE

DONALD HARRISON

(October 2-8)

CHICO FREEMAN

(October 9-15)

BEN WILLIAMS

(October 16-22)

MISSY ELLIOTT

(October 23-29)

SHEMEKIA COPELAND

(October 30-November 5)

VON FREEMAN

(November 6-12)

DAVID BAKER

(November 13-19)

RUTHIE FOSTER

(November 20-26)

VICTORIA SPIVEY

(November 27-December 3)

ANTONIO HART

(December 4-10)

GEORGE ‘HARMONICA’ SMITH

(December 11-17)

JAMISON ROSS

(December 18-24)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/von-freeman-mn0000182113/biography

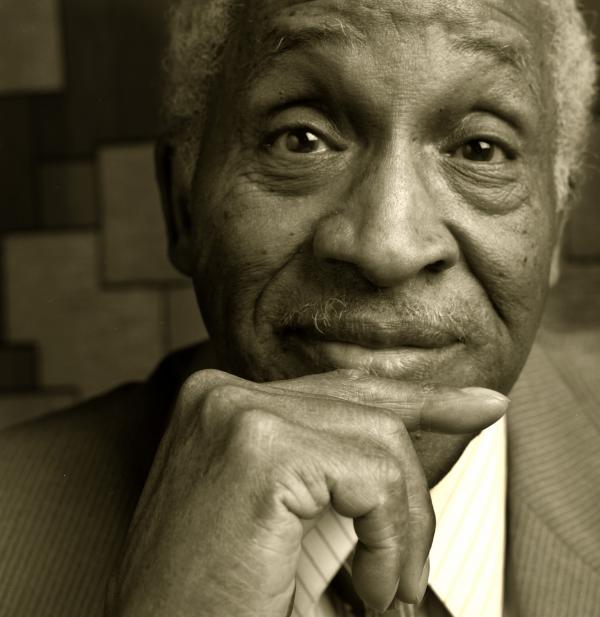

Von Freeman

(1923-2012)

Artist Biography by Chris Kelsey

Not nearly as famous as his son Chico Freeman (also a tenor saxophonist), Von Freeman was nevertheless an equally -- if not more so -- accomplished jazz musician. While not a free jazz player per se, Von exhibited traits commonly associated with the avant-garde: a roughly hewn, vocalic tone; a flexible, somewhat imprecise approach to rhythm, and a fanciful harmonic concept. The son of a ragtime-loving policeman and guitar-playing housewife, Freeman himself began playing music around the age of two, beginning on the family piano. He was surrounded by music from a young age; his maternal grandfather and uncle were guitarists, and his brothers George and Bruz also became jazz musicians (on guitar and drums, respectively). At the age of seven, Freeman made a primitive saxophone by removing the horn from his parents' Victrola and boring holes in it. Shortly thereafter he began playing clarinet, then C-melody saxophone. Louis Armstrong was an early influence.

Freeman attended Chicago's DuSable High School, where his band director was the famed educator Captain Walter Dyett. He also learned harmony from the school's chorus director, Mrs. Bryant Jones. Freeman worked for about a year with Horace Henderson's Orchestra (1940-1941). He played in a Navy band while in the military (1941-1945). Following that, he played in the house band at Chicago's Pershing Ballroom (1946-1950), and for a time with Sun Ra (1948-1949). While at the Pershing, he played with many of the top jazz musicians who passed through town, including Charlie Parker. Freeman developed an underground reputation among Chicago-area musicians, and purportedly influenced members of the city's Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM). Freeman seldom left Chicago and recorded infrequently, therefore never achieving a great measure of fame.

Freeman recorded with Milt Trenier for Cadet in the mid-'60s; Rahsaan Roland Kirk produced a Freeman session for Atlantic in 1972. In the late '70s (as his son Chico became well-known) Von was discovered by a somewhat wider audience. In 1982, Chico and Von shared a Columbia LP with pianist Ellis Marsalis and his sons Wynton and Branford (Fathers & Sons). In the '90s Freeman recorded for the Steeplechase and Southport labels. Freeman was one of the great individualists of the tenor saxophone, and remained creatively vital through the end of the millennium. Freeman died of heart failure in 2012.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/von-freeman

Von Freeman

Earl Lavon Freeman jazz tenor saxophonist, originally became known for his work with the Horace Henderson Group during the Late 1940s, and Sun Ra's band in the early '50s. During that period, he also played with his musical brothers, drummer Bruz (Eldrige) Freeman and guitarist George Freeman, (with pianists including Ahmad Jamal, Andrew Hill, and Muhal Richard Abrams). Chicago Tribune critic Howard Reich says, “...For technical brilliance, musical intellect, harmonic sophistication and improvisatory freedom, Von Freeman has few bebop-era peers.”

The Chicago Reader's Monica Kendrick adds “He changes everything he touches, mostly for the better, with his swaggering tenor tenderness.”

Along with his contemporaries Gene Ammons, Johnny Griffin, and Clifford — the founder of the “Chicago School” of tenor players which adapted the work of Lester Young and Ben Webster, and influenced a number of players including Johnny Griffin & Clifford Jordan. To round out the musical family, the saxophonist's son Chico Freeman is also a well-known jazzman.

In the early 1960s, Freeman toured with Milt Trenier and, despite reasonably regular appearances in New York and Europe, the 75-year-old Freeman has remained to this day in Chicago, where you can see him almost weekly at clubs like Andy's, and has been the host of legendary jam sessions, like his Tuesday events at the New Apartment Lounge. You can catch him with the likes of John Young, Jodie Christian, Mike Raynor, Bettye Reynolds, Kurt Elling, and the rest of his musical family. His 75th birthday was celebrated with a headlining slot at the 1997 Chicago Jazz Festival. He joined one of the city's youngest tenor stars, Frank Catalano, in an afternoon set at the 1999 Fest.

A Fireside Chat With Von Freeman

"It's like apples...Each one tastes differently when you taste it. You get different flavors, which is beautiful. The more you got in you, the more you widen your scope."--Von Freeman

All About Jazz: Let's start from the beginning.

Von Freeman:

Oh, I was very young. I'm back from the victrola. You might be too

young to remember that, Fred, the victrola. But a lot of homes had that

where you played these old-fashioned, round records, the really kind of

heavy ones and my father had a whole bunch of them. I used to be the

winder. You see, Fred, you had to wind them up for each record and I

remember that. I must have been about three years old and I'd climb up

on the stool and get up there and wind it up. I listened to all these

records and that is when I first became very interested in playing

music. I listened to this music and I found out it was the saxophone and

I asked my father because he had no idea that one day I'd be playing

the saxophone. That's when I really started. It was just before I came

out of grade school, like sixth grade. I really started playing on back

porches and beating on garbage cans and that type of thing and just

making sounds. But the neighborhood I was in, there was a bunch of those

kinds of bands. We were always being run off somebody's back porch. My

father had a lot of Louis Armstrong. He had quite a few Louis Armstrong

records. Louis had just started recording when I was very young and he

played them all the time. He had three or four people that he played all

the time and I would be doing the spinning and that caught my

attention. Of course, it could have been my father was so crazy about

jazz music. Actually, he liked all type of music. Literally, I took the

needle on the victrola, it is shaped almost just like a saxophone. It

really is. Of course, my father loved this piece of furniture. It really

was at that time. When he went to work, I would take the head off and

make a mouthpiece out of tissue paper and I was running around the house

playing that thing and when he did come home one day and catch me with

that thing, I thought he was going to go off because my mother had

warned me that he might throw me out the window or something if he

discovered this thing (laughing). It was very disruptive. That is how it

really started out and that is a true story. I actually put some holes

in the head of this victrola that held the needle and was running around

the house blowing on it. My father said that we better get him a horn.

AAJ: You are self-taught.

VF:

You know, Fred, it was really a mistake that I started that way, but a

lot of kids over in the ghetto started like that. You know, I started

out without any lessons of any kind. I remember once, a fella gave me a

piece of paper that had the fingerings to the saxophone to it and that

is how I actually figured out the fingering. But I more or less started

that way. I was just one of the many kids in the neighborhood that did

that on different instruments. We all had something we were beating on

without instructions, which of course is not that good to do. That's the

way most of the kids in the neighborhood that I was running with, we

all were heavily into music and most of us made instruments. It is very

interesting how they made bass. They used to take a tub and a 2 X 4 and

string and everybody knew how to make that one.

AAJ: Was a Chicago sound evident?

VF:

Yeah, I guess if there is one, on the saxophone especially, it is a

collaboration of Lester Young and Coleman Hawkins I would say. Those two

were very popular in Chicago. I remember as a young kid, I used to go

see Lester Young with Count Basie and Hawk would come through town and

play with different trios with different clubs. In fact, he was a very

good friend of my father's. I actually first met him. One day, my father

told me about Hawkins working somewhere. It was near the house,

actually, about two or three blocks from where we lived. My father was

on duty and he used to go over. You see, Fred, he was a Chicago

policeman. Sometimes he would make extra money by being a bouncer at a

nigh club. That was very popular in that era. I had actually met Coleman

Hawkins when I was very, very young. Of course, later on, I got to know

him and even played with him a couple times.

AAJ: Rather than leave for New York, you remained in Chicago.

VF:

It was just happenstance really. But you know, speaking of that, there

is a bunch of musicians around here that probably would be better known

and might have become stars had they gone on to New York. New York had a

lot of the record companies, most of the record companies, especially

main record companies and they would push their clients and that made

all the difference in the world. So a lot of guys went on to New York

and made big names and perhaps I could have done that also, but it was

just happenstance that I stayed around Chicago.

AAJ: Regrets?

VF:

No, not really. I've become very popular in the last couple of years

(laughing). I guess it all evens out, if you look at it that way. Now

that I am eighty, I can look back and I've been through many trials and

tribulations that the average musicians go through. For instance, both

Fred Anderson and I, I think what caused us to survive was both of us

have been what they call outside players. Fred is much more than myself.

I just think everything sort of evens itself out. Like I said, if you

happen to stay around long enough. Of course, even if you don't, the

people that like you will come. I think for years and years and years, a

lot of New York stars were pushed more harder than Chicago people. And

then a lot of people from here went to New York. So we lost a lot of

people. New York is still the leading capital of jazz music.

AAJ: The Apartment Lounge, where a portion of the new record was recorded live, has been a regular night.

VF:

Well, this time, I've been at The Apartment three or four times, but

this time, in 1982, I started there. I was just going in there because

the lady who booked me, she was booking The Apartment at the time,

different little combos, duets and things. She asked me if I would come

because one of her stars couldn't make it and I went in and I went in on

a Tuesday and I played on Tuesday and she said if I could come back

next week and I went back and it has been about twenty-one years.

AAJ: The Improvisor, befitting title.

VF: Well, it is so kind of you to say. I've done it all my life really.

AAJ: Jason Moran plays piano on a couple of tunes and a guitarist is featured on another handful.

VF:

Actually, I went into The Apartment about twenty-one years ago with a

piano group, piano, bass and drums. I had piano for maybe fifteen years

and I lost a lot of piano players. I lost about seven during that tenure

and I said that maybe I should try going in a different direction

because I never could get a real piano, not that an electric piano is

not real, but I'm speaking of an acoustic piano. I always did miss that

and finally, I said that maybe I will just go with an electric guitar

because it was so hard to find somebody for the kind of money I was

playing to bring their own piano. The guitar is a little easier to carry

than an electric piano and it sounded OK to me and so that is the way I

ended up. I finally found a good one in Michael Allemana and a very

good bassist named Jack Zara and a very good drummer named Michael

Raynor (all on the album). They have all been with me for quite a while

now.

AAJ: You play solo on the opening "If I Should Lose You."

VF:

Well, playing solo, I will tell you, Fred, because on this latest

recording, I did this tune and most of the things to me happen very,

very weirdly. Most of the time when I play solo and I've done that on a

few of my recordings, it is done accidently. I remember one record I did

that and the pianist didn't come back in time. He went somewhere, I

guess out to eat or something and I started playing and it was recorded

(laughing). On this last recording, the way that happened was Jason

Moran and I were playing a duet. I didn't even know that we were going

to do this because I never play duets. I featured him and I went to the

mike and said that it is time to introduce this wonderful pianist from

New York and I said that I am going to take the walk and Jason played

and the moment he got done playing, he said that he was going to feature

this wonderful saxophonist and he was going to take a walk and he was

gone and left me standing out on the stage, me and this saxophone. He

was walking off the stage (laughing) and I just told the crowd that I

would do the best that I could do and that's when I played this tune

that happens to be on this recording. It was just happenstance and I was

so fortunate that it turned out OK because you play by yourself, you

are really taking a big risk because you may lose track of the melody

and there is really no time, so you may start faltering with the time

and you may forget some of the chords. You have to have it all yourself.

AAJ: Turned out to be the best tune on the album.

VF: Well, I was very fortunate. Thank you very much.

AAJ: Rahsaan Roland Kirk produced your first album.

VF:

Rahsaan Roland Kirk, oh, that was sort of interesting because I was

traveling. I have done a little traveling, but it was always mostly

overnight or on the weekends and then I would be right back home. I

happen to go to Toledo if I remember it and I know it was somewhere in

Ohio, where he is from I think. His dad or somebody, uncle or some grown

up brought him to see me and he was a little guy. He must have been

eleven or twelve, but he was already great because somebody had taken me

around to see him (laughing) that I had to see this little genius and

he was with some band that was jamming and he was playing two or three

horns at once and doing circular breathing and all that stuff at his age

and he really had it together. Later on, he looked me up. He heard I

had been by to see him and he said that his uncle brought him by and he

listened to me and where was I from. I told him Chicago and he asked me

my name and he said that he had been taken to see most of the great horn

players, but he had never heard of me and he made the staunchest

statement that one day he was going to be famous and he was going to

look me up and see that I got recorded. Well, he was rather precocious

of course, but I said, "Oh, sure," and everybody in the band laughed a

little bit. But you know, that guy, years later, looked me up right here

in Chicago and actually asked me if I remembered him. He was a big star

at that time and he had this big hit record, Three for the Festival,

where he is on there playing three instruments, four, five instruments

at once and he was like a whole band up there. He said he wanted to take

me on to New York because he was leaving and do you know that he asked

me who I wanted and I told him a couple of guys and he said that he had

to have two from New York and so I told him and I had a pianist, John

Young. We worked on and off for fifty years or so. We went off to New

York because he called me the next morning and he fulfilled what he said

and I went to New York and that is where I made this recording. Of

course, it didn't do anything, but they tell me now that it is doing

very well.

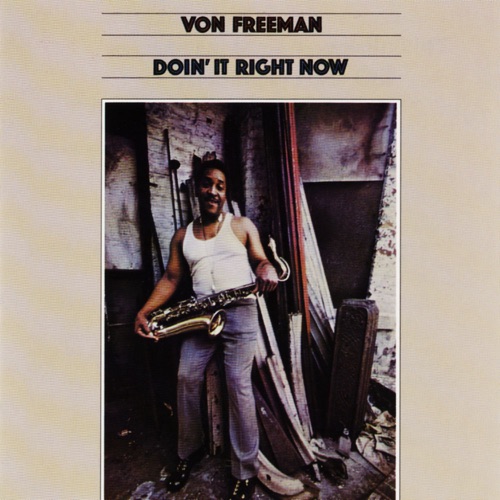

AAJ: KOCH reissued Doin' It Right Now.

VF: Yeah, that's right.

AAJ: You did a live record with your son, Chico at the Blue Note in New York (Half Note Records).

VF:

Yeah, it is always a pleasure and thrill to work with my son. We made

one or two other things for different labels. He was a very smart kid

and he had moved onto college as a mathematician. He won a scholarship

for it to Northwestern, here in Chicago, which is a big time school. I

thought surely, although he was playing trumpet, I didn't think he was

really serious. I thought maybe he would put it down. I used to play

trumpet for years and he went down in the basement and found one of my

old trumpets. The thing was all beat up and battered, but he actually

got it in the band there at school and changed his curriculum around. It

was mathematics and now he was playing the trumpet, but I had another

surprise coming because after he had been in the band for about two

months, which I was very surprised that he made that band. He was fourth

trumpet, but still he made the band. The next thing I know, he came

home with a big case and I asked him that that wasn't a saxophone and he

said, "Oh, yeah, daddy. I think this is where I really belong." I just

looked at him and the next thing I know, the band went to Brazil and

they won honors and he won honors as the best soloist. He went onto New

York and that is where he has been ever since. That was 1971. I just

kind of tipped my hat to him and said, "Go ahead Chico."

AAJ: Do you get many age references being equated with your playing?

VF:

Oh, sure, I run into it all the time. The only thing is, I have been

really blessed and really, just really, really lucky that my health is

as well as it is. A lot of young guys are stunned I blow like this and I

say, "I think I blow harder." It also has to do with I think I play

more instead of just blowing now, along with the knowledge of how to

conserve your energy. It is much easier to play now than at one time.

For one thing, I didn't know much about mouthpieces or reeds or horns or

anything and as you get older, Fred, you learn a lot of things that

makes the playing much, much easier. So I can blow pretty strong and

long and loud and I can still dance if I want to and I can still move

around. I think a lot of people come to see if I'm going to faint or

something (laughing).

AAJ: Your latest sounds better than your first.

VF: (Laughing) Well, thank you very much, Fred.

AAJ: And in the end?

VF:

Well, truthfully, that I tried to be a nice guy and I tried to help the

younger guys and gals. I do it all the time, but it is by osmosis

really because I don't claim to have taught anybody anything. I came up

with great saxophone players and nobody ever told me anything. If you

respect what they are doing, you do pick up things. A lot of kids come

around me now and if I know the answer, I tell them. When they ask how

they are going to sound like me, I tell them I could sound like them if I

tried. I am just telling them the truth. It is a singular music, jazz

music is. You must find yourself. That is the only way you are really

playing jazz. You want to enlighten the world with the touch that you

have.

AAJ: And Von Freeman has done his part.

VF: Oh, thank you. And tell your audience, I love them

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Von_Freeman

Von Freeman

VON FREEMAN

Earle Lavon "Von" Freeman Sr. (October 3, 1923 – August 11, 2012) was an American hard bop jazz tenor saxophonist

Biography

Born in Chicago, Illinois, Freeman as a young child was exposed to jazz. His father, George, a city policeman,[1] was a close friend of Louis Armstrong with Armstrong living at the Freeman house when he first arrived in Chicago.[2]

Freeman's father taught him to play piano and bought him his first saxophone when he was seven. His musical education was furthered at DuSable High School, where his band director was Walter Dyett. Freeman began his professional career at the age of 16 in Horace Henderson's Orchestra.

Freeman enlisted into the Navy during World War II and was trained at Camp Robert Smalls in Chicago. "All the great musicians ended up at Great Lakes", he recalled. "It was an incubator for the best and the brightest lights in the jazz world at that time, and the musical jam sessions were simply phenomenal." After training, he was sent to Hawaii as part of the Hellcats[3] stationed at Barbers Point Naval Air Station in a band that starred Harry "Pee Wee" Jackson, the trumpeter from Cleveland whose nickname was Gabriel.[4] The Hellcats were frequent winners of the islands' competitive Battle of the Bands competitions and included musicians who had formerly played in bands fronted by Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, Ella Fitzgerald, Lucky Millinder, Les Hite, Count Basie, Fats Waller, and Tiny Bradshaw.[5]

After his return to Chicago, where he remained for the duration of his career, Freeman played with his brothers George on guitar and Eldridge "Bruz" Freeman on drums at the Pershing Hotel Ballroom. Various leading jazzmen such as Charlie Parker, Roy Eldridge and Dizzy Gillespie played there with the Freemans as the backing band. In the early 1950s, Von played in Sun Ra's band.[6]

Von Freeman's first venture into the recording studio took place in 1954, backing a vocal group called The Maples for Al Benson's Blue Lake label. He appeared on Andrew Hill's second single on the Ping label in 1956, followed by some recording for Vee-Jay with Jimmy Witherspoon and Albert B. Smith in the late 1950s, and a recorded appearance at a Charlie Parker tribute concert in 1970.

In 1972, Freeman first recorded under his own name, the album Doin' It Right Now with the support of Roland Kirk. His next effort was a marathon session in 1975 released over two albums by Nessa. After that he lived, regularly performed, and recorded in Chicago. His recordings included three albums with his son, the tenorist Chico Freeman, and You Talkin' To Me with 22-year-old saxophonist Frank Catalano, following their successful appearance at the Chicago Jazz Festival in 1999. Four live albums for SteepleChase Records, "Inside Chicago" documented his partnership with trumpeter Brad Goode.

One of Freeman's contributions was his mentoring of countless younger musicians such as Corey Wilkes and Ben Paterson as well as his steadfast support of what he liked to call "hardcore jazz" (as he still did in a 2001 article in DownBeat.)[7] Freeman's quartet played Monday nights throughout the 1970s and the mid-1980s at The Enterprise Lounge which closed when he toured Japan, and then Tuesdays at The New Apartment Lounge with his longtime trio of sidemen composed of drummer Michael Raynor, guitarist Mike Allemana and bassist Matt Ferguson. The quartet played a long set first, the vehicle that showcased Freeman's range from sensitively unwound ballads to intense improvisations that utilized his sometimes rough timbre and indefinite pitch to create a unique avant garde style of his own. His performances were also impressive verbal ones, as he served as an important figure that both helped African-American culture thrive on the South Side as well as invited the participation of European Americans and others into the warmth of the community he and the rest of the Enterprise and Apartment created.[8]

Freeman was considered a founder of the "Chicago School" of jazz tenorists along with Gene Ammons, Johnny Griffin and Clifford Jordan. His music has been described as "wonderfully swinging and dramatic" featuring a "large rich sound".[9] "Vonski", as he was known by his jazz fans, was selected to receive the nation's highest jazz honor, the NEA Jazz Masters award.[10] Freeman died of heart failure on August 11, 2012, in his home town, at the age of 88.[11]

Freeman was the father of jazz saxophonist Chico Freeman.[11][12]

Discography

As leader

- 1972: Doin' It Right Now (Atlantic)

- 1975: Have No Fear (Nessa)

- 1975: Serenade and Blues (Nessa)

- 1977: Young and Foolish (Daybreak/Challenge)

- 1981: Freeman & Freeman with Chico Freeman (India Navigation)

- 1989: Walkin' Tuff (Southport)

- 1992: Never Let Me Go (Steeplechase)

- 1993: Lester Leaps In (Steeplechase)

- 1994: Dedicated to You (Steeplechase)

- 1996: Fire (Southport)

- 1999: Von & Ed with Ed Petersen (Delmark)

- 1999: Live at the Blue Note (Half Note)

- 2000: You Talkin' to Me? with Frank Catalano (Delmark)

- 2001: Live at the Dakota (Premonition)

- 2002: The Improvisor (Premonition)

- 2004: The Great Divide (Premonition)

- 2006: Good Forever (Premonition)

- 2009: Vonski Speaks (Nessa)[13]

As sideman

With Brad Goode

- 2001 Inside Chicago, Volume 1 with Von Freeman (SteepleChase)

- 2001 Inside Chicago, Volume 2 with Von Freeman (SteepleChase)

- 2002 Inside Chicago, Volume 3 with Von Freeman (SteepleChase)

- 2002 Inside Chicago, Volume 4 with Von Freeman (SteepleChase)

With April Aloisio

- 1994 Brazilian Heart

- 1996 Footprints

- 1998 Easy to Love

With Francesco Crosara

- 1999 Colors (Southport)

- 2003 Emotions (TCB)

With Kurt Elling

- 1995 Close Your Eyes

- 2000 Live in Chicago

With Chico Freeman

- 1988 You'll Know When You Get There

- 2010 Lord Riff and Me

With George Freeman

- 1969 Birth Sign (Delmark)

- 1973 New Improved Funk (Groove Merchant)

- 1977 All in the Game

- 1995 Rebellion

- 1999 George Burns

- 2001 At Long Last George

With Joanie Pallatto

- 1995 Passing Tones

- 2000 The King and I

With others

- 1978 Lockin' Horns, Willis Jackson

- 1981 Hyde Park After Dark, Clifford Jordan (Bee Hive, 1981)

- 1982 Fathers and Sons, Wynton Marsalis

- 1991 Rhythm in Mind, Steve Coleman (Novus)

- 1992 No One Ever Tells You, Eden Atwood

- 1994 Silvering, Louis Smith

- 1999 Some Cats Know, Connie Evingson

- 1999 Spaces, Doug Hammond

- 2000 Come Walk with Me, Martha Lorin

- 2003 Emotions, Lilian Terry

- 2006 Solitaire Miles, Solitaire Miles[14]

External links

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/19/arts/music/von-freeman-fiery-tenor-saxophonist-dies-at-88.html

Von Freeman, Fiery Tenor Saxophonist, Dies at 88

Von Freeman, who was considered one of the finest tenor saxophonists in jazz but attained wide fame only late in life, died on Aug. 11 in Chicago. He was 88.

The cause was heart failure, his son Mark said.

Though his work won him ardent admirers, Mr. Freeman, familiarly known as Vonski, was for decades largely unknown outside Chicago, where he was born and reared and spent most of his life.

As The Chicago Tribune wrote in 1998, his playing “represents a standard by which other tenor saxophonists must be judged.”

Last year, Mr. Freeman was named a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master, the nation’s highest honor in the field.

Not until the 1980s did he begin performing more often on famous out-of-town stages, including Alice Tully Hall and the Village Vanguard in New York. Earlier in his career Mr. Freeman had made much of his living, as he told The Tribune, playing for “strip joints, taxi dances, vaudeville shows, comedians, jugglers, weddings, bar mitzvahs, jazz clubs, dives, Polish dances, Jewish dances, every nationality.”

If he never got his big break as a young player, Mr. Freeman said, then that was because he never especially sought one.

“I’m not trying to brag or nothing, but I always knew I could play, 50, 60 years ago,” he told The Tribune in 2002. “I really don’t play any different than the way I played then. And I never let it worry me that I didn’t get anywhere famewise, or I didn’t make hit records.”

What he preferred to chasing fame, he said, was playing jazz as he felt it demanded to be played. The result, critics agreed, was music — often dazzling, occasionally bewildering — that sounded like no one else’s.

Mr. Freeman’s playing was characterized by emotional fire (he was so intense he once bit his mouthpiece clean off); a huge sound (this, he said, took root in strip clubs where the band played from behind a curtain); and singular musical ideas.

His work had a daring elasticity, with deliberately off-kilter phrasing that made it sound like speech. He cherished roughness and imperfection, although, as critics observed, he could play a ballad with the best of them.

Where some listeners faulted him for playing out of tune, others praised him for exploiting a chromatic range far greater than the paltry 12 notes the Western musical scale offers.

“Don’t tune up too much, baby,” Mr. Freeman once told a colleague. “You’ll lose your soul.”

His masterly tonal control let him summon unlovely sounds whenever he chose to, and he chose to often. His timbre has been called wheezing, honking, rasping and, in the words of Robert Palmer of The New York Times in 1982, a “billy goat tone” — a description that, as context makes clear, was not uncomplimentary.

Earl LaVon Freeman was born in Chicago on Oct. 3, 1923. (His given name was occasionally spelled Earle.)

His father was a city policeman — a highly unusual job for a black man then — whose beat included the Grand Terrace Ballroom, a storied nightclub. There, Von soaked up the music of Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, Earl Hines and other titans of the age.

Young Von pined for a horn, and as luck would have it there was one in the house. The fact that it was attached to his father’s Victrola did not deter him, and one day when he was about 7, he pried it off, drilled holes in it and began to blow.

Deplorable sounds ensued, and his father overheard. “He picked me up, just kind of shook me, then hardly spoke to me for about a year,” Mr. Freeman later told Down Beat magazine. But if only as a deterrent, his father bought him a saxophone.

By 12, Von was playing professionally in Chicago nightclubs, reporting for work armed with a note from his mother. It read, “Don’t let him drink, don’t let him smoke, don’t let him consort with those women, and make him stay in that dressing room.”

He graduated from DuSable High School, a public school famous for its jazz program (other alumni include Nat King Cole and Dinah Washington), and entered the Navy, playing in its jazz band.

After his discharge, Mr. Freeman resumed his career, sitting in with some of the finest musicians to appear in Chicago, including Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker and John Coltrane.

He was often invited to join them on the road, but he turned most offers down. He was disinclined to leave home: besides his wife and four children, he had his mother to look after. She had been widowed since Von was a young man, when his father was shot and killed in the line of duty.

In later years, Mr. Freeman played at jazz festivals throughout the United States and Europe. But despite his newfound fame, till nearly the end of his life held court each Tuesday night at the New Apartment Lounge, a small Chicago club where he had performed since the early 1980s. “Vonski’s Night School,” musicians called his sessions there, and young players came from around the world for the chance to sit in with him.

Mr. Freeman’s marriage to Ruby Hayes ended in divorce. Besides his son Mark, he is survived by another son, Chico, a prominent tenor saxophonist, and a brother, George, a jazz guitarist. Two daughters, Denise Jarrett and Brenda Jackson, died before him, as did another brother, Eldridge (known as Bruz), a drummer.

His recordings include “Doin’ It Right Now,” (1972), “Young and Foolish” (1977), “The Great Divide” (2004), “Vonski Speaks” (2009) and, with Chico, “Freeman & Freeman” (1981).

Though Mr. Freeman had not looked for it, renown, when it came, was a vindication.

“A lot of people who didn’t pay a lot of attention to me or to my music started coming around when I was heading to my 80th birthday,” he told The Tribune in 2002. “Now they were saying, ‘Well, Vonski, you’re all right after all.’ ”

Remembering my 1973 introduction to Von Freeman

Over the past 30 years, Von Freeman has become one of a handful of jazz musicians internationally known as Chicago icons. He’s not only linked in the public mind with the Chicago jazz scene—alongside Fred Anderson, Patricia Barber, Kurt Elling, and Ken Vandermark—but indisputably admired by his peers on that rarefied list. This summer the National Endowment for the Arts selected him for its last class of Jazz Masters, placing him in the company of about 100 other artists who’ve been so honored since the program began in 1982. Well into his 80s, Freeman continues to play with a power and vigor that mystify his long-term listeners and challenge his younger sidemen.

The luminary of today stands a world apart from the man I encountered when I first wrote about “Vonskis” in 1973. (The nickname derives from his lifelong habit, inspired by bebop slang, of adding the syllable “-ski” or “-skis” to the end of pretty much every acquaintance’s name; I’ve been “Neilski” since the day we met.) The phrase “when I first wrote about” should be read in its most restrictive possible sense: by coincidence or luck, I was in the right place to publish the very first interview with Freeman—in fact, the first major article of any kind about him.

At the time, Freeman was a knockabout south-side Chicago saxist with an iconoclastic style and a resumé that included some pretty impressive credits—he’d made a lo-fi jam-session recording with Charlie Parker in the early 50s, for example, and played with Sun Ra’s band later that decade. Nonetheless, north of Madison only hard-core listeners had ever heard him (or even heard of him). But other musicians certainly knew him. And in 1972 one of them—wild saxophone prophet Rahsaan Roland Kirk—produced Freeman’s first album, Doin’ It Right Now.

For the 1972-’73 school year, I was a senior at Northwestern and hosting a weekly jazz program for the campus radio station, WNUR (89.3 FM). But I might never have bothered with Freeman’s LP when it arrived in the station’s music library, thanks to its self-consciously funky cover photo of Vonskis in a wifebeater, holding his horn in some dilapidated cellar. I had no idea at the time just how ridiculous that image was—even though he turned 88 this month, Freeman always appears in public dressed with dapper distinction.

Fortunately Freeman’s son Chico—then a trumpet player, later to become a saxophonist and an important jazz artist in the 80s and 90s—shared a music-theory class I was taking at Northwestern. He knew I had an interest in jazz, and one day he said to me, “You know, my father plays saxophone.” (I now consider this akin to saying, “You know, Everest is a mountain.”) Chico suggested I bring his father onto my radio show for an interview, and I first met Vonskis on a Sunday night in the spring of ’73, when he drove from the south side to Evanston to be questioned by a very green white boy.

From then on, Freeman would introduce me as “this fellow who owns a radio station in Evanston.” He knew better, but I think he had fun watching me squirm when he said it.

Judging by that interview, I figured Freeman would make a pretty good story for the Reader, the fledgling weekly for which I’d begun writing the previous year. (It turned out to be my first cover feature.) I spent some more time with Vonskis in front of a cassette recorder, and then went down to beard the genial lion in his south-side den—Betty Lou’s at 87th and Vincennes, where Freeman hosted a weekly set that even then included lots of sitting in by proteges and wannabes. I was the only white person in the room and, at 21, one of the youngest. But I still felt comfortable walking in and finding a spot at the bar—right up until Freeman greeted me and offhandedly offered a friendly warning: I’d be “safe as a bug in a rug,” he said, as long as I stuck by him.

Fast-forward to the 90s, by which time Freeman had moved his weekly sessions to Tuesdays at the New Apartment Lounge on 75th Street, where in 2002 the block in front of the club was renamed Von Freeman Way. The room brimmed with people, white and black in almost equal numbers, many of them tourists from Europe or Japan. The kids bringing their horns and hoping to sit in were usually predominantly white, trekking in from area colleges to pay some dues and grab a little of Freeman’s reflected spotlight. (The club recently reopened after renovations that lasted most of 2011, but whether Freeman will return to his weekly gig remains to be seen.)

In the 90s and 00s, Freeman placed his career in the hands of two Chicago record labels. Southport Records got things started with some loosey-goosey projects that put him on the discographical map; then Premonition Records’ Mike Friedman oversaw several more sessions, better planned out and more carefully controlled, that resulted in the albums that will likely endure as the saxophonist’s legacy.

Freeman owes both labels a great deal of gratitude for helping to bring his utterly unique, devastatingly authentic talent to the world’s attention. He had rarely traveled outside Chicago when he began recording semiregularly in the 1980s; in this century, he’s performed frequently in New York and Europe. Covered widely in jazz journals, chronicled in the Chicago Tribune, reviewed in the New York Times, Freeman as a senior citizen enjoyed a career boost that would have dazzled a jazz musician half his age. Nonetheless, throughout the 80s and 90s, he often referred to me as “that young man who made me famous” and mentioned the Reader cover story from decades earlier. This “young man” turned 60 last month, and I still think that it was really more the other way around.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Neil Tesser, author of The Playboy Guide to Jazz, began covering jazz for the Reader in 1972 and most recently contributed a 2008 feature about Sonny Rollins‘s time in Chicago.

https://www.jazzwise.com/features/article/life-changing-albums-von-freeman-s-doin-it-right-now

Life-changing albums: Von Freeman's 'Doin' It Right Now'

Monday, January 7, 2019

Saxophonist Steve Coleman talks about the album that changed his life, 'Doin’ It Right Now', by Von Freeman.

Interview by Brian Glasser

For me, it’s not really about records so much as live gigs. There was a guy called Von Freeman – not everyone’s heard of him! – in Chicago where I grew up. He didn’t formally give me lessons, but he was kind of like a mentor. Watching him year after year definitely changed my life. I would make private recordings and listen to them. I started off with stereo reel-to-reel, later on cassettes. I’d be in the audience, these were nightclubs so it wasn’t so much of a stage. I’d just be there recording, because I was trying to learn the music. I was 18, 19 – that’s when I started learning what the music was about.

When I played them back later, there was so much to get: the rhythm, the way it flowed, melody, harmony, saxophone stuff like fingering and breathing – there’s so much that you’re getting all at once when you see somebody live. The earliest album I heard of his was Doin’ It Right Now, but it’s different on record. I listened to records of course, but for me the much more important thing was seeing people live.

With the tapes, I had to work it all out myself – I didn’t understand anything at the beginning. These guys were older professionals in my father’s generation and they wouldn’t tell you anything – it wasn’t like a school situation where they’re telling you what the chords are and so on. They learned the same way – so I figured if they could do it, so could I. For me, it’s way better than going to jazz school – it’s not even close. Actually, it’s not even a matter of ‘better’ – it’s not the same thing. It’s a whole different kind of learning.

I’ve never taken one improvisation lesson in my life. I won’t say that I didn’t try to study with Von – but he said, ‘No – I don’t teach’. I asked another guy in Chicago for lessons – Bunky Green. And he told me ‘No’ too! They were my two favourite saxophone players in Chicago at the time; so, I thought, if these guys aren’t going to teach me, then forget it – I’ll just get it like they got it.

Primarily, what I did was this: there were people like Charlie Parker who I’d found out about; and I wanted to know how they learned how to play; and I wanted to copy it. Not mimicking what they were playing but how they learned how to play – their process. I knew that that process produced great musicians, so I wanted to know what it was. That’s what they’d done in their time – they didn’t go to schools like Berklee. I thought: ‘These guys didn’t learn to play in school – so I’m not going to learn how to play in school’. To me, that was kind of obvious.

Initially, I went to a particular concert to see Sonny Stitt, because he sounded like Bird to me, so I had that sound in my head. Von Freeman, who I didn’t know at the time, was the other saxophonist on the concert. But Sonny Stitt didn’t live in Chicago; whereas Von did. When I talked to Von afterwards he said, ‘I have these sessions that happen every week on the South Side’; and gave me the address. It wasn’t far from where I lived, so I started going. That’s how I hooked up with him. It wasn’t because I thought he was amazing – I couldn’t hear that in the beginning. I only heard that later, after I started hanging around. Even that took a while, because my ears weren’t developed.

I was always aware of death – I knew everyone wasn’t going to be around for ever; so I tried to get as much as I could from people while they were still around. Whether it was Thad Jones, Woody Shaw, Joe Henderson – I tried to see them as much as I could. If you want to be a master shoemaker, you hang around master shoemakers! It’s osmosis.

Having said that, when I listened back to the tapes of Von when I was young, I did try and emulate him – I tried to play the notes and transcribe them. You have to do that to know what they’re doing – you have to get into the detail. I listened to Von from 1975 – when I was 18 – till when he died. I only played professionally on a gig with him two or three times, and I made a couple of recordings with him. Usually he was playing with his group and I was playing with mine.

The learning part never stops – I’m still trying to figure out what people are doing! For me, ‘doing my own thing’ and ‘learning’ is the same thing, it’s not separate – learning is my own thing …

https://londonjazzcollector.wordpress.com/2014/02/25/von-freeman-have-no-fear-1975-nessa/

Von Freeman: Have No Fear (1975)

Nessa Records

Artists

David Shipp (bass), Wilbur Campbell (drums), John Young (piano), Von Freeman (tenor saxophone) Recorded June 11, 1975, engineer Stu Black

Music

Finding myself owner of this record, but knowing nothing about the artist, the label, or the genre of Chicago jazz, I first fact-checked the usual suspects, just in case I put my foot firmly in my mouth. The results were encouraging:

Dusty Groove say:

One of the best studio albums ever from the legendary Von Freeman – and a date that really captures some of the careful essence of his live performances in Chicago. … This easy-going Nessa session really lets him open up and take off – blowing tunes that are straight ahead, but always with that offbeat style that turns the songs inside out – making them rich exploratory fields for inventive and creative solos.

Amazon reviewer says:

This is one of the best tenor sax players of his day, hopefully with his passing his legacy will come to light. The playing on this is crisp and swinging. … Not a household name outside of Chicago but for many years he held court in the windy city. I would rate this five stars, straight ahead jazz at it’s finest.

Wiki add:

Freeman was considered a founder of the Chicago School of jazz tenorists along with Gene Ammons, Johnny Griffin and Clifford Jordan. His music has been described as “wonderfully swinging and dramatic” featuring a “large rich sound”.

“Vonski,” as he was known by his jazz fans, was selected to receive the nation’s highest jazz honor, the NEA Jazz Masters award. He died of heart failure at the age of 88. on August 11, 2012.

LJC says:

Both Nessa and Von Freeman were new to me, drawn to my attention by LJC poster Andy C – hat tip. I’m not proud, I can learn. An unfamiliar artist but you feel immediately at home with the music. A little homework indicated that Von Freeman was a heavyweight.

During the golden years of the ’50s and ’60s he worked only as a sideman but with some big names, making his first recording as leader as late as 1972. Over the following four decades he released a string of albums in the genre he liked to call “hardcore jazz” but remained a stalwart of the Chicago jazz scene.

Perhaps it made sense to stay home in Chicago. By the early ’70s many jazz greats were prematurely deceased, had fled New York for Europe or followed the money to LA scoring for film/TV. Worse, some had donned gold lame pants and embraced the funky chicken, or even worse, the “F” word, Fusion.

Freeman’s commitment to the mainstream jazz tradition is worthy of exploration. Mounting Have No Fear on the turntable, I pretty soon found myself wondering where the last twenty minutes had gone. It may not be ground-breaking or boundary-pushing, but it is thoroughly enjoyable jazz.

Vinyl: Nessa N-6 Stereo

Great feisty sounding record – gutsy tenor, strong piano, firm bass and punchy drums. Solid pressing. The build- quality of the cover is another matter Makes you appreciate those thick card laminated Blue Note and Impulse all the more.

Report this adCollector’s Corner

Source:

Rarely frequented vintage vinyl shop off tourist mecca Portobello Road West London.

LJC poster Andy C pointed me at Nessa, a Chicago based specialist small jazz label founded by one Chuck Nessa, a name I keep coming across on the Groovisimo forum (frequented by some of the usual suspects here, you know who you are).

Andy recommended the tenor player on the Nessa label, Von Freeman . I knew I had seen the name Von Freeman on an album somewhere, but for the life of me couldn’t remember where or when. It’s a strange thing, that. While looking through hundreds may be thousands of records a month, you can actually remember seeing one record title and artist name for a split second, and you can remember the name and vaguely a cover, despite giving it no thought, passing on it. However you can’t remember anything important, like the date of your wedding anniversary.

A month later, for no better reason than looking for a birthday card from a shop I knew that had nice cards, I found myself in Notting Hill. Notting Hill resident Prime Minister David Cameron was busy issuing flood warnings, Julia Roberts was on answerphone and Hugh Grant’s line was engaged: so much for blending in with the locals. The card shop had closed down, what else but take a rare browse through a local record store that rarely has anything, and what should pop up in hand? Von Freeman, on Nessa. Spooky.

Heaven knows what this record’s ownership history was, adorned by a gold sticker from an Amsterdam record store, The Jazz Inn. I wonder if they are still around. Sounds like my sort of place.

Hi LJC, another genever? Had this great record come in. Von Freeman…You don’t know him? He’s great.

And so he is.

https://tedpanken.wordpress.com/tag/von-freeman/

For Von Freeman’s 97th Birth Anniversary, a 1991 WKCR Interview with Von and pianist John

Von Freeman and John Young

November 20, 1991, WKCR

copyright © 1991, 1999, Ted Panken

Q: Von Freeman and John Young were both born in 1922, and both went to DuSable High School. When did the two of you first meet?

VF: Well, I remember John from a long time ago. Let’s just put it that way. For a long time.

Q: Was it in school?

VF: Oh, I don’t know. I . . .

Q: Was it in a musical situation?

VF: Well, I knew about him long before I really knew him. I always admired his playing, way-way-way back.

JY: I remember, Von, when we first played together, when was it, 1971, at . . . What was the name of that place?

VF: The New Apartment Lounge?

JY: At the New Apartment Lounge, yes. The other piano player, Jodie Christian, couldn’t make it. So Von called me to work with him, and we’ve been working with each other on and off ever since that time.

Q: But you had known each other back in high school undoubtedly.

JY: Well, I knew him, but our paths didn’t cross. He had his family band, his brother on drums and another brother playing guitar, and he played tenor saxophone, and I think he had Chris [Anderson?] . . . Anyway, he was using other piano players at the time. I was working with a dude named Dick Davis.

Q: So this was in the 1940’s, after the War.

VF: After the War, uh-huh.

JY: Or the 1950’s, I think it was.

Q: Both of you studied under Walter Dyett, and I believe John Young was in one of the first classes at DuSable High School as well. Didn’t it open around that year?

JY: Well, I was in the second year. What happened was, in ’34 they attempted to extend the old Wendell Phillips High School. It was called the new Wendell Phillips High School. But then they decided not to tear down old Wendell Phillips; they decided to keep it, and changed the name to DuSable. So it started off in 1934 as the new Wendell Phillips High School. They had to go into that stone and change the name to DuSable.

Q: There were a number of very talented young piano players in your class at that time.

JY: Well, I was in there with Dorothy Donegan and a fellow named Dempsey Travis, who wrote that book (he was playing the piano then, at that time), and Marbetha Davis. Nat Cole had just graduated not too long before that. Nat Cole and somebody else, I can’t think of him. Those were the piano players. We used to do what they called the Hi-Jinx at DuSable High School.

Q: The Hi-Jinx was a show band type . . .

JY: Yeah, it was a show to raise money. It was a fundraiser. And I was in the Hi-Jinx with these dudes, as a matter of fact, Redd Foxx was in one of those Hi-Jinx, a tramp band. But that was one of our fundraisers.

Q: So there was really tremendous musical talent all concentrated in this one high school, and there continued to be for many, many years.

JY: That’s right. Captain Dyett was at the root of it all. He’d cuss us out and make us do better than we did the previous time. He’d throw us out of the band, and if we came back the next day and didn’t make that same mistake, he’d pretend like he didn’t notice that we came back. He’d let us stay. [Von laughs]

Q: John Young, how long had you been playing piano at the time you entered high school? Had you already developed your musicality?

JY: Yes. I had my first lesson when I was about eight, I think it was. I had a private teacher for about ten years. Two, because I had one lady for five and then a gentleman for the other five. The lady didn’t want me to play jazz; she said, “That old devil jazz.” She wanted me to be a classical artiste. But I’d been listening to Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington and Basie, and I said, “Well, that’s me.”

Q: You could be an artiste of another sort. But this was all music that was really part of the Chicago scene when you were a youngster coming up.

JY: Yes, that’s right.

Q: I don’t know how much first-hand exposure you were able to get as a teen and pre-teen. But give us a little flavor of what things were like in Chicago when your consciousness about music was starting to emerge.

JY: Well, if you want to know what things were like in Chicago, I’d better let Von . . .

Q: Von Freeman, I’ve been neglecting you.

VF: No, it’s fine. John is doing fine. [John laughs] But I really don’t remember.

Q: You don’t remember?

VF: No, man. Listen . . .

JY: It’s just like “Stardust,” huh?

VF: Yeah, listen.

JY: “Oh, but that was long ago . . . “

VF: See, because things were so groovy then that you had a tendency not to even realize how good it was. For instance, John was talking about Art Tatum before; of course, anybody with any musical sense at all loved that man’s piano playing. And I was lucky to have the fellow who first told me about him playing in a group of mine. His name was Prentice McCarey. Prentice was just like John. He loved him. He was a great piano player himself. Every time Coleman Hawkins would come through town . . . And this was way back, before I went to the War, so it was in the ’30s. See, I lived over Prentice McCarey. I used to listen to him practice on the piano. He was playing a place called the Golden Lily on 55th Street with one of my idols, which of course was Coleman Hawkins. And later on, I happened to have acquired a job at this same club on 55th Street on the south side of Chicago, upstairs. And it was funny . . . We were playing there, and Prentice said to me, “Man, guess who I’m gonna bring by your club tonight?” Well, I couldn’t guess. I thought he meant Prez, because he knew I loved Lester — Lester Young. But it was Art Tatum.

I’ll never forget that night, because when we got through playing, he went somewhere and picked up Art, and brought Art back. Let’s see, we got off at about one; it must have been about 2 o’clock in the morning. And Art played for about four or five hours just on the piano. And the piano wasn’t that great; a couple of keys were broken. He just missed them all night long. And that’s one of the high evenings of my lifetime. I had just gotten married, I think I was 23 years old or something like that. I didn’t realize how great that was.

The reason why I brought that up is that’s the way Chicago was. It was so good and there were so many big people in town . . . Like 63rd Street was full of musicians, full of clubs. 64th Street, the great Pershing Lounge up there. They would bring everybody in . . .

Q: But in the ’30s, when you were a teenager . . .

VF: Oh, that’s when it started. That’s when all that got started, and it really lasted until just about to the end of the ’40s . It started really dying out around 1950.

Q: For instance, as teenagers, were you able to go, say, to the Grand Terrace and hear Earl Hines, or was that off-limits to you?

VF: No, I never went. I was too young for that.

JY: Well, they broadcast from there, so we . . .

VF: But we heard that, though.

JY: We heard it on the radio.

Q: And was this what you were trying to come in under? Was Earl Hines the band that you admired? Von, when you were a young saxophonist, who were some of your models?

VF: Well, one of the persons is still living. What’s his name, John? He plays at Andy’s a lot now. On Mondays. He plays clarinet and tenor . . . Sort of a red looking fellow. He was on there with Budd Johnson. Oh, his name is Franz Jackson.

But see, during that era, Earl was just one of the many bands. Like, Count Basie was out here and all those big bands. Because that was the big band era. And of course, Earl had one of the better bands, and it just happened that he was based in Chicago. But then when Earl left, King Kolax brought a band in (do you remember that, John?) for a while.

JY: Yeah.

VF: He was a great trumpet player around town. And of course, he had Bennie Green with him, Gene Ammons . . . In fact, Billy Eckstine took some guys out of his band. Gene Ammons was in the Kolax band.

It was so good, and there were so many different personalities coming in from around the country. Now when you look back, when there’s nobody coming in on the south side, hardly, you think about how good it really was. That’s the reason why it’s hard to remember, because you should have been writing down all that stuff, really, but you didn’t. You had a tendency to think to think it was going to last forever, and of course it didn’t.

[MUSIC: Von and Chico Freeman, “Mercy, Mercy Me”; Gene Ammons, “My Way”]

Q: John Young joined Andy Kirk and His Clouds of Joy as a pianist in the early 1940’s.

JY: That’s right.

Q: What was your progression from high school to the point where Andy Kirk was calling you to join his band?

JY: Andy Kirk was on the road and needed a piano player, so he called the Harry Gray, the President of the Musicians Union, to send him a piano player, and he recommended me for the gig. Harry Gray was the type of fellow that has a big voice and talks loud; he was one of those kind of guys that believes in talking loud on the phone to get his point over. He calls me up on the telephone, and he says: “Mister Young!” He scared me half to death because I was young; I was only 19 or 20 years old. “Young! We have a job for you. It’s with Andy Kirk. Can you make it?” Hey-hey! I didn’t know what to say, you know what I mean. I said, “Uh-unh-uh-unh . . . ” He said, “Well, I’ll call you back.” So he called me back . . . I had to talk about it with my mother because I wasn’t 21 years old yet, see. So I had to tell my mother about it, and beg her to let me go. So anyway, he called me back, and I said, “Yes, sir, Mr. Gray. I’ll make it.” So he said, “Yes, well, okay then, I’ll call Andy.” So that’s how I got with Andy Kirk.

Q: Were you familiar with the band from records before that?

JY: No. All this was completely new. Mary Lou Williams had left the band, and the piano player who replaced her had just recorded “The Boogie-Woogie Cocktail.” “The Boogie-Woogie Cocktail” was getting over. So I had to take the record home and learn it off the record. [sings theme] So I took it home and laid my ear on it, and got back and played it as close as I could to the way the record sounded.

Q: Were you working in Chicago after high school?

JY: Yes!

Q: What were you doing in the interim? Tell us a little about your activities, John Young.

JY: Well, after I left high school, a fellow called me up and he took me to Grand Rapids, Michigan, and I worked with him. I forget his name. But my earliest recollection of working in Chicago was some striptease joints. So I enjoyed that.

VF: [laughs] Look out, John!

Q: Was it solo piano?

JY: No-no . . .

Q: Did they have a little band?

JY: No, no, they had a group. It was a striptease joint downtown on . . . I think it’s called Clark Street — at a striptease joint down there. And then I worked in a place called Calumet City. What they would do . . .

Q: The notorious Calumet City. [Von: loud laugh]

JY: They would hang some drapes, some see-through drapes in front of the band, because they didn’t want the customers to think that the musicians were too familiar with the striptease artists, you know what I mean? So we played . . . Some of these striptease artists had some very difficult music while they was out there taking clothes off. And you’d be mad, because they got you there, and you’re back there sweating, and all they’re doing is just walking, traipsing around and taking a piece off here and there. And you’re back there sweating, trying to play the “Rhapsody In Blue” while they’d be walking around. But that’s what they liked. That’s what the striptease person wanted. And they’d want you to play that music. So I did . . . [sings ‘Rhapsody In Blue’] . . . and they’d just walk around, taking a little piece off here and there.

So that was my first gig before I really made a living. You know, you always make gigs here and there. But the first gigs that I remember where I really made a living was them striptease joints.

Q: Were you playing a lot of blues then, too?

JY: Oh, yeah. Well, you had to play that.

Q: Just talk about the piano styles in Chicago that you’d have to be going through.

JY: Yeah, yeah, that’s right. You had to play a little boogie here and there, and a little . . . Anyway, you had to know a little bit about most styles. Play a little of what they called stride, and you had to play a little boogie, and you had to play a little oom-pah, oom-chunk, oom-chunk-chunk — “boom-chink,” you would call it. You had to do a little bit of everything in order to try to make a living at it — which is the same thing I’m doing now. In order to make a living, you’ve got know a little bit about all of this.

Q: Well, subsequently (and we’ll talk about this later), you played with quite a few singers.

JY: Yes.

Q: Von, what were your earliest gigs after high school? Or were you also working during high school, outside?

VF: Well, you know, it was just about the same.

Q: You worked in the same strip joints.

VF: Oh, yes! [John laughs] And in fact, one of the first groups that I worked with, I can’t quite remember this man’s name now, but he was the drummer. The only thing I can really remember about him was he sat so low. He sat like in a regular chair, and it made him look real low down on the drums. I said, “I wonder why this guy sits so low.” You could hardly see him behind his cymbals. And we were playing a taxi dance. Now, you’re probably too young to know what those were.

Q: Well, I’m certainly too young to have experienced them first-hand.

VF: Oh! Well, see, what you did was, you played two choruses of a song, and it was ten cents a dance. And I mean, two choruses of the melody.

Q: No more, no less!

VF: And the melody. And man, when I look back, I used to think that was a drag, but that helped me immensely. Because you had to learn these songs, and nobody wanted nothing but the melody. I don’t care how fast or how slow this tune was. You played the melody, two choruses, and of course that was the end of that particular dance. Now, that should really come back, because that would train a whole lot of musicians how to play the melody. And I was very young then, man. I was about 12 years old.

Q: Were you playing tenor then?

VF: Oh, C-melody.

Q: C-melody was your first instrument.

VF: Yeah, my first one. And that really went somewhere else, see, because that’s in the same key as the piano. But it was essential. And of course, I worked Calumet City for years, and I learned a lot out there! Like John said, you played a lot of hard music, and you essentially played the melody out there. You had to learn the melody to tunes.

And so right today, I try never to forget the melody. Because I’ve found out that the people don’t forget the melody. So no matter how carried away I get, I try to remember the melody. All this stuff that you learned early in your career, you come to find out most of the things . . . Like, I wasn’t that crazy about Walter Dyett’s teaching. He was . . .

Q: Too authoritarian?

VF: . . . a disciplinarian and whatnot. But see, as you go along, and especially when you start getting in those 60s and closer to 70, see, you learn . . . One lesson is that most of the people who patted you on the back all the time and said, “Blow!” didn’t really mean it. The folks that you really think about are the ones that said, “Hey, man, that doesn’t sound good” or “Hey, that’s wrong.” They don’t really mean that it’s wrong. It’s incorrect; let’s put it that way. But you learn and you look back, you say, “Hey, they were trying to help me.”

Q: Von, let me get back to your career. When did you graduate from C-melody to the tenor?

VF: Well, I was playing dances. See, there was a famous lady named Sadie Bruce, and she gave me my first job. I must have been about . . . My first local job on the south side of Chicago was in her dance room. Because see, I used to tap dance.

JY: Yeah?

VF: Yes. So she asked me one day, “Somebody told me that you play an instrument.” I said, “Well, yes, Mrs. Bruce, I do.” She said, “Well, have you got a little old band? Because I’m planning to start some socials in my basement.” I said, “Well, I don’t know whether we’re good enough to play for that.” She said, “Well, I heard you on one of these back porches; you sound pretty good to me.” We used to do a lot of back porch clowning and playing.

But the interesting thing about that was that I had James Craig with me. Now, you may have never heard of James Craig, but he’s the piano player on Gene Ammons’ “Red Top” that did that little thing that’s kind of got . . . When you play “Red Top,” you have to play that little thing that he put in that song. He was a very good pianist. I had a vibe player named Norris from out of DuSable, and then I had Marvin Cates on drums. And that was my little group. I guess I was about 15. And it was the first job I played on the south side of Chicago, although I had been working in Gary and working downtown in the strip places.

So you know, my history is similar to John’s and almost everybody around Chicago. Because most of the jobbing was done in strip places in Calumet City and Hammond . . .

Q: Did those gigs get set up through the union?

VF: No-no-no. In fact, the union didn’t know anything about it.

Q: So those were things to avoid . . .

VF: Well, you worked eight hours for ten dollars. The union would have had a fit.

JY: Yeah, they were strict about that.

VF: It was like . . . the mines, we used to call them. But you could earn a living.

JY: That’s right.

Q: And learn a lot of music.

VF: Oh, listen! Now, when I look back, what you learned was invaluable. Because you learned discipline. You’d sit there playing the melody of the songs all night long . . .

Q: And I guess ten dollars went a long way in 1937.

VF: Oh, man, you dig? And it helped my lung power a whole lot, too.

Q: Smoke-filled rooms and all.

VF: Listen, you learned how to put that air in that horn there. Piano players learned how to really get a touch.

Q: I know that later Captain Dyett would form bands of his students and join them in the union, and they’d play gigs around that town? Was he doing that when you were there?

VF: Well, that was the one band that he called . . . See, we were all out of school, our high school called DuSable, and he called his band the DuSableites. He kept it for a while. He started it about two years before I went into the service, and then I came out of the service, then went back into it and stayed until about ’46 — about two more years. So he had that group from about 1941 until maybe ’47 or ’48.

Q: The years after World War II, from 1945 and ’46, were thriving years musically in Chicago. Von Freeman, you and your brothers — George, the great guitar player, and Eldridge “Bruz” Freeman, a drummer — had the house band at one of the most prestigious rooms in Chicago, the Pershing Ballroom. What were the circumstances behind that? And talk a bit about the geography of the Jazz scene in Chicago in that particular time and around that area.

VF: Oh, man, that’s when it was buzzing. From 31st Street all the way on up to let’s say 64th Street — well, 66th — Chicago was the place to be. John Young was at the Q Lounge, Dick Davis — everybody was in town and had a gig. It was right after the War, and the town was booming . . . They had a great promoter around town named McKie Fitzhugh. This guy came out of DuSable, and he was promoting. And he called me one day and he said, “Would you be interested in maybe getting your two brothers . . . ” See, because my brother George was very popular around that time.

Q: Had he been in Chicago during the war?

VF: Yes. You see, he didn’t go to the war; he was too young. He stayed around Chicago, man, and his name was buzzing. So he said, “Hey, why don’t you get together with your two brothers and get a piano player and a bass player? I’ve got an idea; I want to book a lot of names into the Pershing.”

Q: He likes to pick with a silver dollar, your brother.

VF: Right. That’s what he does now, yeah. So I said, “Okay, that will be fine.” So there was a fellow named Chris Anderson, a little blind pianist, and I had Leroy Jackson on bass (Leroy has since passed), and Alfred . . . What was Alfred’s last name, John? Do you remember Alfred?

JY: White.

VF: Alfred White. I was using two bassists at the time, concurrently, you know. So we went in, man, and that’s where I met Diz and Bird, Billie Holiday — everybody came down there.

Q: What sort of room was that? That was part of a complex of clubs . . .

VF: Oh, that was the ballroom itself. See, but the Pershing Lounge was beautiful, too. I played that later on. But at that time I was playing the ballroom.

Q: How was it set up? The national musicians would come in, and there would be dances?

VF: Yeah, dances. Dances Fridays and Saturdays.

Q: So people would be dancing to Bird, dancing to Diz . . .

VF: That’s right.

Q: Dancing to the people who would come in with you.

VF: Well, around that time things had changed a lot. They would stand around the bandstand, and there wasn’t that much dancing going on any more. And we used to play, man. I used to have a ball just playing with the stars, listening to them or whatever. I’m very lucky to have gotten chosen for that particular job.

Q: So who came through? We’re talking about the major stars in music at that time?

VF: Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie and Billie Holiday, Lester Young, Coleman Hawkins, Roy Eldridge — you name them. He brought everybody to Chicago, man. And he was paying so nice for those times. What he’d do is, he’d bring them in, and they would come in with no music, no nothing, and you were expected to know the tunes. And I had this little genius at the piano who knew everybody’s tunes. So we were very fortunate. We were able to play behind them.

Q: You’re referring to Chris Anderson.

VF: Yes.

Q: Von said that you, John Young, were working at the Q Lounge during this time.

JY: The Quality Lounge.

Q: The Quality Lounge. A high-quality joint, was it?

JY: Ah-ha-ha . . .

Q: I see.

JY: I was only in two shootings.

VF: At least! [laughs]

Q: Where was it? Which street was it on?

JY: The Quality Lounge was on 43rd Street. So if you know anything about 43rd Street, you know it wasn’t on the uppity-uppity-uppity-up. The Quality Lounge, I was in there with a fellow named Dick Davis who played tenor saxophone. I was the piano player, the drummer’s name was Buddy Smith, Eddie Calhoun was on bass. And I was singing . . .

Q: Singing, too.

JY: But at that time I had laryngitis. When (?) asked me to sing, I suddenly developed a case of laryngitis. All three of them called it “lyingitis” — because it was a gitis that never left. But the Q was cool . . . Like I say, it was a relaxed joint. You could come in there with tennis shoes on if you wanted to. It wasn’t nothin’ uppity, you know. And it was on 43rd Street. We had a good time in there for a number of years, the Quality Lounge on 43rd Street. I lost my point . . .

Q: Oh, I was talking to you about working in Chicago in the late 1940’s and late ’50s. When did you start working with a lot of singers?

JY: Well, a piano player always has a hundred singers around, you know.

Q: But you later became an accompanist for some major singers.

JY: Well, I was with Nancy Wilson for a hot minute in the ’60s. See, John Levy, the booking agent, he was a bass player around Chicago, so he just about knew everybody that he thought would fit with this or that person. So he thought that I would be a perfect fit for Nancy Wilson. He didn’t know that I was really into jazz, and that I wanted to be a jazz piano player. I wanted to be out front. You know what I mean? I won’t say out front, but I wanted to receive some of the same recognition that soloists receive rather than accompanists. But anyway, he hooked me up with Nancy Wilson, and I stayed with Nancy for a short spell.

And I had to write him a letter to explain to him why I didn’t stay. He thought that I should have stayed with her, because he gone to the trouble of booking me with Nancy Wilson, he felt that we were a perfect match, some kind of match anyway — and Nancy had struggled with me to try to get me to play here things like she liked them. So he thought I was going to be with Nancy Wilson for life. And I explained to him that, no, that ain’t what I had in mind.

When the piano player is a singer’s right arm, as they say, there are certain limitations to what he can do and what he . . . I’ve seen piano players be accompanists for life with certain singers or performers, and they stay in a rut for a long time. There’s only so much you can do as an accompanist. When you get thrown out there where you have to play the melody or have to carry the load, you’re lost.

Q: Well, we can get back to that in a minute. But I’d like to return to someone Von was talking about: Chris Anderson, who had a great impact really on the piano players in Chicago.

VF: Oh, man, he’s unsung. When I first met him, I met him in a big arena that we used to play on the south side, on 63rd Street and King Drive. I forget who I had on piano this time, but whoever he was, wasn’t making it. Chris happened to be sitting there, and he walked up and whispered in my ear, “I think I could play that.” I kind of looked at him, because I’d had people at different times to do that, say things like “Hey, man, I think I can do it a little better than what so-and-so is doing; I think I’ll feed you a little more” and blah-blah-blah. I generally don’t even listen. But for some reason or another, I said, “Oh, really?” Because this cat didn’t know the tune. I had asked him if he knew it, and he said, “Yeah,” and then when I got to playing the tune, he didn’t really know the tune.

So meanwhile, I guess the piano player heard Chris, and he said, “Hey, man, if you can play it, play it.” So he played it. And I said, “Hey, man, what’s your name?” And I noticed he was a little short fellow, you know . . . I said, “Hey, man, you stay there. I’ll pay both of you.” I told the other guy, “I’ll pay you, man, not to play.” So that’s how we began.

Chris heard a lot of things, just naturally, that I was trying to hear. And he was a very nice person about his knowledge. So I’d ask him, “Chris, where did you go there?” And he’d say so-and-so and so-and-so and so-and-so. So I learned a lot from him. At the time, I had been using Ahmad Jamal. And then Ahmad . . . He had a guitar player, I forget where this fellow was from, I think from Pittsburgh, where Ahmad was from. [Ray Crawford] So Ahmad had told me that he was giving me a two-week notice, that he was going to form his own trio. He’d stayed with me, I think, about two years, and then he formed his own trio. And then he started hanging with Chris, too. And I really noticed a big difference in his playing after he had been around Chris. Almost anybody who had been around him, it kind of opened them up a little bit — because he was very advanced for those times. In fact, I still think he is.

Q: So do a lot of other musicians around New York.

VF: Mmm-hmm.

Q: But his influence seems to go through a couple of generations in Chicago.

VF: Yeah, well, I think . . .

Q: Was Andrew Hill checking out Chris? Herbie Hancock?

VF: Well, Andrew worked with me a long time, too, you know. But Andrew was more or less into bebop at that time. But Chris to me wasn’t a bebop player, he wasn’t a swing player, he didn’t play like Art Tatum. To me, he was . . .

JY: He had his own thing.

VF: Yeah, he had his own thing. He was a conglomeration of all of that. And he didn’t flaunt his knowledge or anything. Maybe being blind helped him a lot, I don’t know. But he could hear a lot of things that I had always heard, and that I think everybody eventually wanted to hear. He was advanced for that time. See, now I’m speaking about 40 years ago.

Q: I’d like to ask you about a couple of the other great musicians who were working around Chicago a lot at that time? I’d like to ask you both about Ike Day, and if you both came into contact with him, played with him?

VF: Well, we used to go around playing tenor and drum ensembles together. He was a great drummer. And he was one of the first guys I had heard with all that polyrhythm type of playing; you know, sock cymbal doing one thing, bass drum another, snare drum another. He was very even-handed. Like the things Elvin does a lot of? Well, Ike did those way back in the ’40s and the late ’30s.

Q: Did you know Ike well enough for him to tell you about the drummers he was paying attention to as a young drummer?

VF: I know he liked Chick Webb. He never really mentioned anyone to me other than Chick Webb. And he liked Bird’s drummer . . . .

Q: Oh, Max Roach.

VF: Yeah.

Q: And I know Max Roach liked Ike Day, because he’s said so publicly on a number of occasions.

VF: Right.

Q: He was also a very versatile drummer, is what I gather. He would play big- band, piano trio combos. He was a totally versatile drummer, with great ears, a great listening drummer and so forth. Does that jibe with your recollection?