Transcript of conversation with David Baker

David Baker: One thing that I've found, that

anywhere I go on earth, where there is music, more often than not, the

music that we call jazz, the music that came out of America, is a music

which is like the lingua franca of music to the rest of the world. I

can't imagine a world without jazz, and the fact that it's a living,

functioning, exciting organism.

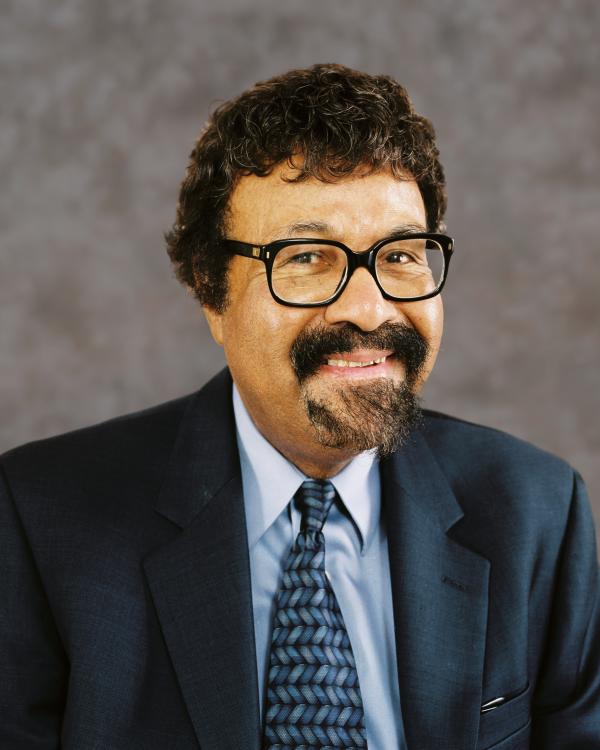

Jo Reed: That was NEA Jazz Master David Baker. Welcome to Art Works,

the program that goes behind the scenes with some of the nation's great

artists to explore how art works. I'm your host, Josephine Reed. Born

In Bloomington, Indiana in 1931, David Baker has pretty much done it all

in the world of jazz: he plays the trombone and the cello, composed

more than 2,000 pieces of music including symphonic works as well as

jazz. He led a big band in the late 50s/early 60s and is now conductor

and artistic director of the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra.

He’s Chair of the Jazz Studies Department at Indiana University's

Jacobs School of Music, and he’s written 70 books. He’s received

many honor, most particularly he was named an NEA Jazz Master in the

year 2000. I spoke to David Baker recently and began by asking him what

drew him to jazz.

David Baker: In my particular case, growing up

in segregated America, because where I went to high school, it's a high

school that was built in 1927 called Crispus Attucks High School, and it

was built because it was the first of the segregated schools in

Indiana. And so the music I heard on the radio in the black community

was music of Louis Jordan, of Charlie Parker, of Dizzy Gillespie. So I

was really drawn to that, and really to all music in fact, but that

music was the music that I had access to and the music that I had a

realistic chance of being a part of, because basically at that time, the

symphony orchestras were not as open as they are now, and even there,

it's still somewhat limited. And I certainly wasn't going to be writing

opera. It was the music which was available to me. When I listened to

the radio, listened to my parents talk, that's the music they were

playing, that's the music they listened to. And I still believe that

it's axiomatic that people love the music that they fall in love to.

Jo Reed: And you were born in 1931, so when you were at Crispus Attucks, it was kind of the mid '40s then.

David Baker: Yes. I graduated in 1949 from high

school, and at that time, Indiana, particularly Indianapolis, had become

a focal point for the rest of the country, as far as jazz goes. It gave

us Wes Montgomery, JJ Johnson, Freddie Hubbard, Monk Montgomery, and it

goes on and on.

Jo Reed: Well you mention JJ Johnson. He was one of

the first trombonists to really play bebop and he wasn’t just from

Bloomington, he went to the same high school as you, didn’t he?

David Baker: He sure did. Graduated in 1942, and

he was my idol, because I chose to be a trombone player, and I can't

tell you how many days I would go to school and go down the hall where

they had the pictures of the people who graduated in 1942 and look at

JJ, anticipating a time when hopefully I would meet him. And as it

turned out, we did meet and he became my teacher, and a friend and a

mentor. That story can be replicated a whole bunch of times with people

in Indianapolis, who represented, I guess, the icons.

Jo Reed: You met first JJ Johnson at the Lenox School of Jazz, is that right?

David Baker: No, I didn't. The fact is, I knew

JJ before, but I knew him in a much more casual setting, because I would

see him, and when he would come to Indianapolis, I would just go up and

remind him that I too come from Indianapolis, and he would ask my name

again. And when I got to Lenox School of Jazz, JJ was my trombone

teacher. And he would always say, "I don’t do this for a living. I

don't know how to teach, so here's what I'll give you." And it always

was wonderful wisdom. And sometimes you'll have knowledge and more

knowledge and none of it comes out finally as wisdom. But with JJ it

was. He knew that he was not specifically a teacher, but all of the

things that he did were the things he learned on the street, and he was

able then to convey to us by simply telling us how he did it and why he

did it, and what makes it go.

Jo Reed: The Lenox School of Jazz really was

something. I mean it had such a simple premise: you get the world's

greatest jazz musicians to teach jazz to promising young musicians. And

even though it was open for such a short time, I think maybe three

years, it really left a legacy.

David Baker: I can't think of anything that's

more important to jazz education than the Lenox School of Jazz. I'll

tell you why, it became the model, the paradigm for almost all the

programs. And people really don't know this, which I find disturbing

sometimes, and try to do what I can to help people understand, but with

John Lewis and Gunther Schuller and you had people who actually had

teaching experience in a university or in a high school. But you had

people who were street cred, people like the Modern Jazz Quartet, the

people like Sonny Rollins. And so you had this wonderful, wonderful, as

Quincy Jones liked to call it “gumbo.†And I thought it's a

beautiful way to say that what happened there is the reason why jazz

classes exist at most of the universities, whether we're talking about

Indiana University or North Texas, or even Berkeley.

Jo Reed: I like gumbo, bringing a little bit of New Orleans up to the Berkshires.

David Baker: And what beautiful gumbo it is and was.

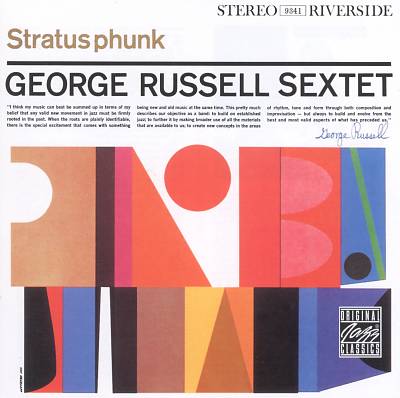

Jo Reed: David, you studied with George Russell who

wrote the first theoretical contribution to come from jazz. He was very

influential in your career, wasn’t he?

David Baker: And I think to really the life of

jazz in America, because George, in my estimation, has been the most

important theoretician to come out of this music. He's the only one, I

think, that has found the system, or a set of systems, that have been

verified. We find they work. We know they work. George Russell, over

across those years when he left Cincinnati where he was born, put

together a system that I've been unable to find any holes in it. And

that's hard to say, because even in traditional theory, there are

things, "Don't do this, don't do that. This doesn't work." But with

George, he gave you all the tools, without demanding that you follow his

route or whatever. He gave you the tools: this is it. These are the

possibilities and you'll probably find other possibilities.

Jo Reed: I think we need to say what it is that

Russell did. Very simply put he expanded harmonic language and he moved

passed the major-minor system which dominated Western music for over 300

years. And Russell encouraged his students to continue to push the

music, to explore, didn’t he?

David Baker: Very, very much so. Well, in fact, I

think he insisted. He said that's why the system was devised, why he

came up with it, and he worked on it for many, many years. And in 1959 I

think was the first time I had seen the results of what he had put

together, because he had had tuberculosis. While he was in that

hospital, he pulled all the parts together. Finally, it was presented in

loose-leaf pages when we were at Lenox School of Jazz. A great man,

probably one of the most important voices, because when you talk about

Miles Davis, you talk about Gil Evans, all of them pay homage to him for

the fact that he brought an order to information that they possessed.

Jo Reed: You played in his sextet, didn't you?

David Baker: Yes, I was one of the founding

members of his sextet, and let me tell you, those were the most exciting

years of my life. And it's the reason why really I decided to settle

in, because I could have played and done the other things I do, compose.

But because of George as the model, and in fact, George's having

convinced me, as well as many other people, how important that would be

the transmission of this information. And fortunately, he was able to

bring it to fruition at New England Conservatory where he taught and the

private students that he had, and they are numerous. And every one of

them is a part of the George Russell legacy.

Jo Reed: As you mentioned, you started playing

the trombone, but then you had an accident that affected your playing.

What happened and when did it happen?

David Baker: Well, the accident actually took

place in 1953, a car accident where they didn't expect that I would

live. I was thrown through the front. This was before seatbelts. We had

the accident. Somebody hit the car that I was in and I was thrown 18

feet through the front window. And they had already started funeral

proceedings. And I think that God in my life makes a big, big

difference, because these are the things that led me to other paths,

other routes to take. Had I not had that accident in 1953, I probably

would not have been a teacher. I would probably have composed and just

played. And I found out that every time there was a door that closed

because of some accident, or because somebody who touched me, it opened

another door that ultimately intended and finally worked out to be a

door that I should have gone through. But George Russell saw that, and I

was in his band and Quincy's band when the efforts, when the results of

that accident started to manifest themselves. For instance, in '53, I'd

found out after I started trying to play again that one side of my face

had hypertrophied, while the other side atrophied, and I'd been playing

on this imbalance, and constantly making adjustments. And ultimately,

none of them worked, and another door opened for me, because without

that, I probably would not have become a teacher and become a student of

George Russell's across the years, and able to transmit some of that

information he gave to me and so many other people.

Jo Reed: Well, you turned to the cello, which is a little bit of an unusual choice for a jazz guy.

David Baker: It is indeed, and sometimes I

really go back and say, "Boy, how stupid was I to think at that age that

I could start playing a cello?" It was a strange choice, but it was a

choice that was pretty much governed by my exposure to it by my band

teacher in high school. And he said, "David, these other instruments are

not going to give you the challenge that playing a cello will." And I

could have strangled him when I look back on it now and think, "Boy,

that instrument defies…" I don’t think a cello likes human beings,

but I have had the good fortune to be around people like Janos Starker,

who has been so instrumental in helping me with that instrument. And I

think maybe just because it was an instrument that nobody else at that

time of note was playing, it gave me a challenge, but it gave me a

chance then to find the voice that would be distinctly my own voice,

despite the fact that it was an instrument that is so difficult to play,

that there were times, as I said before, I wanted to strangle Mr.

Brown. Unfortunately, he died before I could get to it.

Jo Reed: Is it fair to say with that switch to the cello, it also opened you up to focus more on composition?

David Baker: You're very prescient. You're

absolutely right. That instrument lent itself to my spending a lot of

time listening to the music of Shostakovich, of Kodaly, of Bela Bartok,

and in the process, I began to understand that I was put on that

instrument for a specific reason, and the reason was that that was the

door that opened me to composition.

Jo Reed: Well, let's talk about you as a composer. You have composed thousands of pieces

David Baker: One thing is that my curiosity is

such that I don't draw lines about anything other than the worth of the

music: is it good or is it bad? So there never was for me this chasm

that exists sometimes between classical and jazz music. So for me, with

the cello now the instrument that I was playing, I started to look and

really examine, and I had a chance to study then with Gunther Schuller

and with John Lewis, as well as with JJ. So all of a sudden, my world

exploded into all of these different things, and all of them closely

related one to the other, and it's just a question of what you intended

to do or what you chose to do with that information. For me, it was to

write, to compose, to make music. And for a long time, I was very, very

fruitful in what I was writing and stuff. And I hit a dry spot about ten

years into that, and I thought, "Boy, I'm running out of ideas

already." And then when I realized, I was starting to be more critical

of what I was writing, so I was not nearly as fruitful, that I was

turning out so many pieces. Now I think it's under control where I

recognized that it has to be given great scrutiny if you're going to

hope that the music would continue to grow.

Jo Reed: Okay, here's a question from someone

who's not a musician, but I just wonder, can you talk about the

difference between playing the music and composing the music?

David Baker: Yes, I can. Composing the music is

different from the improvisation and playing the music, in that

decisions are instant when you're playing. I mean, you don't have a

chance to go back with an eraser. You don't have a chance to go back and

try to say, "Well, maybe this would be better." Of course, we do,

because we have the technology to do that. With jazz, every performance

is absolutely different, even when you intend to play it the same way a

second time or a third time. It's brand new. So I call composition

frozen improvisation.

Jo Reed: But I would imagine when you compose

for jazz you would have to leave room for a certain amount of

improvisation within the performance?

David Baker: Yes. I think that 90 percent of the

time that's probably true, even though Ellington and others would very

often write out the entire piece. And, you know, to have the best of

both worlds, where there are pieces that I write that I don't want

anybody to improvise on because basically, I don’t know that they

would take the path that I intended the piece to go. But there are other

pieces that I write in this third stream that Gunther named in 1958, I

think, that I want them to have time to be able to play. And I have the

best, you know, I know how blessed I am to have the best of both worlds.

Jo Reed: Throughout your career, even when you

were playing, you always kept a focus on education as well. And you went

back to school as you were playing and got a masters degree and then

worked on a doctorate. Why were you doing that?

David Baker: Well, I suppose part of it was just

the fact that I was born with a huge curiosity about how the world

works. And I think I wanted to know, you know, I tell people now that

very often, it's hard for me to go to sleep. I need less sleep than most

people, simply because I'm so afraid something will happen while I'm

asleep, and I want to know all of the things. I know that none of us is

omniscient. Only God is that but everything that there is to know I want

to know. A new book comes out, I read the book. New techniques come

out, even though I'm a dinosaur in terms of technology, it does not

prevent me from being absolutely curious and also seeking out those

people who can make available to me this wealth of information that is

almost out of control, there is so much of it. When I stop and think,

from the time I started to play to now, music has changed in such a way

that it's unbelievable and it looks like every five years or so, it

undergoes another metamorphosis.

Jo Reed: But David, back in the day when you were working on your advanced degrees, it's not like there were jazz programs out there.

David Baker: No, there were no jazz programs

then, of course. Nature abhors a vacuum and so consequently, because we

didn't have those books, we didn't have people teaching it, and people

would come to me-- and I was very fortunate because I had a number of

students who became famous like Freddie Hubbard, like the Brecker

Brothers and whatever, I knew that there was a vacuum. And because there

was a vacuum, it meant that I could write, I could teach, I could do

these things, not only me, but Jerry Coker, Jamey Aebersold, and a host

of others. I just happen to be one of those people in the right place at

the right time.

Jo Reed: What's important when you're putting together a curriculum for jazz?

David Baker: Well, veracity is the first thing,

to make sure that you've done homework, that you really have a sense of

what's true and isn't true. It's almost like you have to go to the

Griots in Africa, the older people, and you say, "Is this what happened

for real?" And of course now, with the oral history projects that happen

like at the Smithsonian, now we can go back and make sure. So I like to

make sure first of all that I'm in possession of as much information as

I can before I write about it. And it was just my good fortune to get

there at a time when there were only a handful of books that dealt with

how to transmit this information to other people. Now there are volumes

that would probably fill a room if you just stacked them. But

fortunately, they're now accessible, because of the iPod and all of

these other things now that make it possible for a student to walk about

with 2,000 tunes in their breast pocket.

Jo Reed: So, it’s safe to say you’ve seen a lot of changes over the 40 years you’ve been teaching.

David Baker: And you know to me, that's the

thing that makes it so exciting and makes it so important, it isn't

frozen. It's, like I said, a living organism. And what seems like

immutable truth, five years later we find out that that really isn't it

at all, or that it has changed so much that you don't even recognize

what it was when it was at that other place. But as a teacher, the thing

that is great for me, and I think other teachers, is that we are the

repositories of that information, so that when I talk about Ellington

and I teach a course on Ellington, I have to talk about the Ellington of

1927, when he opened at the Cotton Club. And that's not anywhere near

the Ellington of 1985 or 1945 or 1955. And to be constantly aware, and

it takes me hours to prepare my classes. And people say, "When you've

been teaching a class for 40 years, why do you spend two hours preparing

it?" The facts don't change. What happens is our perception and how it

affects other people, how it has been modified by new information, is so

important, so that we don't get frozen and think that music stopped at a

particular time. Even if we can say it was the classical period, it was

the romantic period, even our perception of those things changed as we

uncover new information.

Jo Reed: Let me ask you, while we're talking about teaching is there a class that you always look forward to teaching?

David Baker: Yes, basic improvisation because

that, to me, is the root of everything else we do. If you don't have

that, all the other things are pretty much doomed. I can't imagine,

certainly for the layperson, there's a different level. But for jazz

people who are serious, you really have to have improvisation as the

basis for what you do.

Jo Reed: What excites you about your students

now when they're playing. And I mean, just what excites you about the

younger generation of jazz musicians?

David Baker: Is their ability to access and

process information. You know, the thing is, if I was starting now, I

couldn't even get into Indiana University, or into any of the other jazz

schools. Even though we were maybe the crème de la crème of our time,

those things keep changing. And I think the beautiful thing about it is

our ability to adjust and adapt to those changes without destroying

where they came from. And to me, the most exciting thing is the fact,

watching these kids, and I teach at a little place called Ravinia in the

summertime with a camp I have right outside of Chicago. And the level

of these kids now. I don't mean they have the wisdom and knowledge all

the time, but they have physical skills, they have mental skills, that

over the years have grown and grown and grown to the point where now

they pick up an instrument and do things that Charlie Parker and

Coltrane would have been amazed that somebody who's 17 or 18 years old,

or, for that matter, a different gender, a woman, can do all of these

things, and that's exciting for me. That's the reason why I keep

teaching, because when I walk into that classroom and there are 60

people who are hungry to know; it's the reason why, when I give a

lecture, I tell them, "The most important part of my lecture is the

questions that you ask me, because you make me have to re-examine my

positions. Do I still think this way? Is that really the truth? Has it

changed since I started?" And I find that so exciting, being around

young people.

Jo Reed: Okay, and finally, can you just recall

how you found out you were made a Jazz Master? What that was like for

you, what the whole event was like?

David Baker: Yes. And it was so exciting,

because I got the letter and the first thing is incredible. You say, "Oh

me? Really?" And then I can remember, I think it was in 2000, Mary

Mcpartland and Donald Byrd, and the three of us received the NEA award

at that time. And I remember I was probably the youngest of the bunch.

But to see the excitement in this cross-generational group, receiving

this from the United States government with the big letter from the

President and the whole thing. Nothing can adequately describe how

exciting it is, not just for me, but I'm looking at these hardcore

musicians, Herbie Hancock, a musician like the late Miles Davis, and

they have that same excitement. You know, I don't know anything that we

do that really equals that as far as how it affects our lives. And to

me, when I go, I feel so proud of my country that in fact we have taken

the time to invest money, resources, to make sure that the rest of the

world knows how we feel about this music.

Jo Reed: David Baker, thank you so much. I appreciate it.

David Baker: Jo, thank you.

Jo Reed: And I'll see you at Jazz Masters.

David Baker: I'll see you then.

Jo Reed: That was NEA Jazz Master David Baker, talking about his career in music.You’ve been listening to Art Works, produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. The music is “To Dizzy with Love†and “Some Links for Brother Tedâ€

Composed by David Baker, and performed by the Buselli/Wallarab Jazz Orchestra They’re from the CD titled, Basically Baker.

The Arts Work podcast is posted every Thursday at

www.arts.gov. Next week, the focus is opera. I speak with legendary

composer, Carlisle Floyd. To find out how art works in communities

across the country keep checking the Art Works blog, or follow us @NEArts on Twitter. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

Music up, hot.