SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2020

VOLUME NINE NUMBER ONE

BRIAN BLADE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

SULLIVAN FORTNER

Eddie Henderson

(b. October 26, 1940)

Artist Biography by Matt Collar

Balancing a career in psychiatry with his love of forward-thinking post-bop and fusion, trumpeter Eddie Henderson has cut a distinctive path in modern jazz. Mentored by Miles Davis in his teens, Henderson emerged as an original member of Herbie Hancock's Mwandishi band in the 1970s, appearing on the landmark jazz-funk album Sextant. From there, he embarked on a solo career, issuing several of his own cross-pollinated funk and disco-infused albums for Capricorn, Blue Note, and Capitol Records. These albums, and especially his breakthrough U.K. hit "Prance On" from 1978's Mahal, were influential touchstones for later hip-hop, electronic, and acid jazz musicians. A licensed psychiatrist with a degree from Howard University, Henderson often split his time playing jazz and working in medicine. From the late '80s onward, he has remained a vital presence on the New York City jazz scene, releasing a bevy of well-regarded acoustic jazz albums like 2010's For All We Know and working as a member of the hard bop supergroup the Cookers.

Born Edward Jackson Henderson in New York City in 1940, Henderson grew up in a family steeped in the jazz tradition. His mother was a professional dancer at the Cotton Club, while his father was a member of the legendary Charioteers vocal group. Encouraged to play music, he first picked up the trumpet around age nine, and famously received an early lesson from Louis Armstrong, whom his mother knew from her days in Harlem. During his teens, Henderson moved to San Francisco with his family, where he continued to progress as a musician. A driven, highly disciplined student while in high school, he balanced his music practice, with studying, playing sports, and participating in competitive figure skating. It was during these years that he first met his longtime idol Miles Davis, who stayed at his parent's house when playing in the Bay Area. From the late '50s on, Davis was a heavy influence on the trumpeter's approach to jazz. It was also through Davis that Henderson first met future boss and bandmate Herbie Hancock.

After a stint in the Air Force, Henderson enrolled for medical school, earning his undergraduate degree at the University of California, and later finishing his medical studies at Howard University where he graduated in 1968. During his time at Howard, he would often spend the weekends driving from Washington, D.C. to New York to study with Freddie Hubbard and Lee Morgan. After earning his M.D., he then returned to the Bay Area where he served out a psychiatric residency and played jazz in his off-hours. While there, he was asked to join Herbie Hancock's innovative funk and fusion-based Mwandishi ensemble for a week-long run of shows in San Francisco. This led to a full-time appointment, and from 1970 to 1973, Henderson toured and recorded with the group, appearing on the influential 1973 album Sextant.

As a leader, Henderson debuted with two well-regarded albums on the independent Capricorn Records label, 1973's Realization and Inside Out. Produced by Skip Drinkwater, whom Henderson met via his work with guitarist Norman Connors, these albums essentially featured the Mwandishi band with Hancock on electric keyboards, Bennie Maupin on reeds, Patrick Gleeson on synthesizers, Buster Williams on bass, and Billy Hart on drums. There were also contributions from drummers Lenny White and Eric Gravatt, as well as future-Headhunters percussionist Bill Summers. Both albums showcased a funky, avant-garde, electric fusion style similar to Henderson's previous work with Hancock. More Drinkwater-produced albums followed on Blue Note, including the psychedelia-dipped Sunburst with George Duke and 1976's Heritage, which featured a young Patrice Rushen on keyboards, sax, and flute.

Around this time, Henderson signed with Capitol Records and released three albums beginning with 1977's Drinkwater-produced Comin' Through. These productions built upon his previous efforts, but found him moving in even more of a cross-over direction with a less spacy, more dance-oriented approach to jazz-funk. In 1978, he scored a U.K. hit with the disco-infused "Prance On," off Mahal. His Capitol era culminated in 1979's equally disco- and soul-leaning Runnin' to Your Love. Although somewhat dismissed as "commercial" in the decades following the fusion era of jazz, Henderson's electric recordings enjoyed great popularity with hip-hop and electronic musicians, and are often cited (along with Miles Davis' and Herbie Hancock's work) as influential on the development of trip-hop and acid jazz.

Moving to New York full-time in 1985, Henderson's solo recordings slowed somewhat as he worked increasingly as a physician. Nonetheless, he stayed active, appearing on albums with Billy Hart, Leon Thomas, Gary Bartz, and others. With 1989's Phantoms, he returned to regular recording with a series of albums that found him embracing an acoustic hard bop sound. He presence continued to grow throughout the '90s with harmonically nuanced, hard-swinging albums like 1994's Inspiration, 1995's Dark Shadows, and 1999's Reemergence. These albums still found Henderson indebted to Davis, but displaying his own brand aggressive, post-bop lyricism. It was an approach that only deepened as he entered his sixties, delivering such albums as 2004's Time and Spaces, 2006's Precious Moment, and 2010's For All We Know.

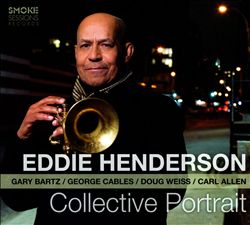

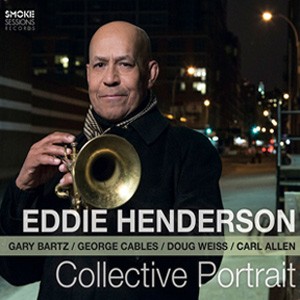

Along with his own work in the 2000s, Henderson also played with the Mingus Big Band, Benny Golson, and others. He worked regularly with Billy Harper, eventually joining the saxophonist in the all-star ensemble the Cookers alongside longtime associates drummer Billy Hart, pianist George Cables, and bassist Cecil McBee, as well as trumpeter David Weiss and saxophonist Donald Harrison. A regular at New York's Smoke nightclub, Henderson has released several albums for their in-house label, starting with 2015's Collective Portrait. That same year, he celebrated his work with Hancock on 2016's Infinite Spirit: Revisiting Music of the Mwandishi Band. In 2018, he delivered his second Smoke Sessions date with Be Cool, featuring Cookers bandmate Harrison, pianist Kenny Barron, bassist Essiet Essiet, and drummer Mike Clark.

Eddie Henderson

Eddie Henderson

Eddie Henderson is one of today's top and most original jazz trumpet players. Henderson was born in New York City October 26, 1940. His father sang with the Charioteers, and his mother danced as one of the Brown twins at the Cotton club. Louis Armstrong gave Eddie his first few trumpet lessons at the age of nine.

Eddie moved with his family to San Francisco when he was 14 years old. He studied at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music from 1954 to '56. Around 1956, Miles Davis was guest at Eddie Henderson's home during a black Hawk Jazz Club gig and was impressed with Eddie's ability to perform his famous “Sketches of Spain” without a fluff but encouraged Henderson to seek his own originality.

Following Air Force service from 1958 to '61, Eddie became the first African American to compete for the National figure skating Championship, winning the pacific and Midwestern titles.

The year 1961 was the beginning of Eddie pursuing dual careers-medicine and music. After receiving a bachelor of science in Zoology at the University of California at Berkeley in 1964,he got his M.D. at Howard university Medical School in 1968. Eddie interned at San Francisco's French Hospital during 1968 and '69 and undertook a two-year residency in psychiatry at the University of California hospital from 1969 to '71.

Henderson first got worldwide recognition for his jazz- trumpet playing from the popular recordings he made with Herbie Hancock's Mwandishi group during the early '70s. other jazz performers Eddie has played with include Pharoah Sanders, Art Blakey, Elvin Jones, Johnny Griffin, Slide Hampton, McCoy Tyner, Benny Golson, Max Roach, Jackie McClean, Dexter Gordon, Roy Haynes, Joe Henderson etc.

Henderson has been on the faculty at Juillard School of Music since 2007.

https://ofa.fas.harvard.edu/blog/eddie-henderson-mark-jazz-musician

Eddie Henderson:

The mark of a jazz musician

by Andrew Chow '14

Harvard University

If there was ever a Forrest Gump of jazz, it would be trumpeter Eddie Henderson.

Of course, the main difference is brainpower: Whereas Tom Hanks’ 1992 character Gump is a simpleton, Henderson is a fully licensed physician who practiced medicine for 13 years. As with Gump, Henderson has lived through a large part of the 20th century, experiencing and even playing a major role in the landmark moments of of jazz culture. At age 9, he blew his first notes into Louis Armstrong’s trumpet. He hung out with Miles Davis as a teenager and joined Herbie Hancock’s trailblazing Mwandishi band in the 1970s.

He will be featured in the Learning from Performers series (3 p.m., November 14 at the Thompson Room in the Barker Center) and then play a concert with the Harvard Jazz Bands (8 p.m., November 16 in Lowell Lecture Hall). Below are excerpts from our conversation about his incredible journey.

Beginnings

"My mother was a dancer at the [prominent Jazz Age Harlem venue] Cotton Club. My father was a singer for a gospel group. So by virtue of both of them being in show business, they knew all the big names. My mother’s roommate, when she was at the Cotton Club, was Billie Holiday. Her best friends were Lena Horne and Sarah Vaughan. All of these people, like Duke, Count Basie and Louis Armstrong, used to come over to the house. Boxer Joe Louis and Sugar Ray Robinson, they were friends of my mother, and I met all these people. I just thought they were average people. I was wrong."

On his first love

"When I was 14, my family moved to San Francisco. I had no friends because I didn’t know anybody. So my stepfather bought me a ticket for the Ice Follies, and I immediately fell in love with ice skating. I started practicing seriously. I’m the first black person on this planet to ever compete and win a national championship in figure skating. I thought that was my calling in life."

On learning the trumpet

"When I was in the 5th grade, my mom took me to the Apollo Theater to hear Louis Armstrong and took me backstage after the show. I didn’t really know who he was--I was just 9-years-old!--but I met him and he taught me how to make a sound on his trumpet. Then I started taking private lessons on the instrument. I started high school in San Francisco when I was 14, where my stepfather was a doctor. When I was 17, one of my stepfather’s patients, Miles Davis, stayed at the house the whole week. He took me to his gig to one night. He had John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley in his band, a bunch of greats from the era. When I heard that music, that’s when the light went on. I said to myself, 'That’s what I want to do with the rest of my life.’ I started trying to learn how to play jazz from that point on."

On joining Herbie Hancock’s band

"After college, I went to medical school and became a doctor. However, I was playing the trumpet all the time, and my heart really was in jazz. Then I heard that Herbie needed a trumpet player. I knew him through Miles. He knew I played trumpet, but he didn’t take me seriously. But I was serious about music. So when he hired me for one week, that one week turned into the rest of my life. That group was way ahead of its time. Herbie had a group before me, playing music like Fat Albert Rotunda. And it was nice. But when he changed personnel, just like in chemistry, when you add different elements, sometimes you can have an explosion, a precipitate. With the Mwandishi group, it was a magical formula. Sometimes the music would jump off the paper and things would take place. We worked together three-and-a-half years, 10 months a year. Everybody got paid only $300 dollars a week. We’d usually travel by van across the country, and you had to pay your own hotel bill on the road. That was big money in those days for a jazz musician."

On self-evolution

"Music is a language. The more idioms and vocabulary the musician learns, the more eloquently he can speak through his instrument. When I got into funk and even disco in the late '70s and '80s, it was a learning experience for me, step by step. The mark of a jazz musician is to play one note, and everyone knows your sound. You just don’t want to be lost in the crowd. When I was younger, I used to imitate people, just like Ray Charles would imitate Nat King Cole. I used to imitate Miles, Lee Morgan, Freddie Hubbard. After a while, I said, ‘Oh, who am I?’ My style is as collection of styles that I had scotch taped together. I just do it a little different. That’s my style."

[Caption: Eddie Henderson]

https://jazztimes.com/archives/eddie-henderson-dr-trumpet/

Eddie Henderson: Dr. Trumpet

There was a stretch of 10 years in San

Francisco, between 1975 and 1985, when trumpeter Eddie Henderson was

juggling two extremely demanding disciplines: practicing medicine and

playing the trumpet. In 1973, Henderson had finished a rewarding stint

with Herbie Hancock’s Mwandishi band, which produced the exceptional,

exploratory records Mwandishi, Crossings and Sextant, and relatively

soon after he felt compelled to return to his other field of study.

I got my M.D. in 1968 but I didn’t start practicing medicine until

1975,” says Henderson. “It was only four hours a day, part time, so I

was always still playing too. I had the fortune to be at a clinic in

San Francisco where the head of the clinic knew I was heavily involved

in music, so whenever I’d get tours or whatever he would let me come and

go as I pleased. So it was the perfect lifestyle. But music was my

number one thing emotionally, even though I was practicing medicine at a

very skilled level.”

Between practicing medicine and keeping his trumpet chops in check, all

of Henderson’s waking hours were consumed during that busy time. “But

it was cool-just a matter of focus and discipline,” he says. “I’ve

always been like that because in high school I was a competitive figure

skater. I think that’s where I really got my discipline, on the ice.

During the summer I was on the ice at least 10 hours a day, from 5:30 in

the morning until the evening. And at the same time I was going to the

[San Francisco Conservatory of Music], going to high school, playing

basketball, too. So I was always pretty focused. And by virtue of that

discipline I got going, everything else that came later was a breeze.

My undergraduate degree at the University of California-that was a

breeze. Also, medical school was a breeze for me, because I was very

focused. I had good study habits, good organization skills. A lot of

the other guys, they wouldn’t come to class for months because they’d be

out partying. But I never missed a class in my life and studied every

day. Those other guys tried to cram and you just can’t do that and

retain information, not the last week before the finals.”

In 1985, Henderson moved to New York to pursue his musical path while

continuing to practice medicine in the early stages of his relocation.

“I practiced medicine here in New York a bit,” he says. “I worked for

the Transit Authority for three months and then at a little clinic for

about a year or two, just a couple hours a day. I moved here for music,

not to practice medicine. And now I have not practiced medicine in

about 11 years.”

For Henderson, music and medicine go hand-in-hand. “Music and medicine

are both divine disciplines,” he explains. “You’re dealing with the

human body, which is a divine creation, on one hand. And then you’re

dealing with the divine creation of music. The universe is made of

music. Everybody’s billions of cells in their bodies-those are

vibrations, the vibrations of the solar system, the movement;

everything’s in a constant flux. And I’m dealing with both of them.

They’re just very different mediums through which you can see yourself.

“But for me, that old adage of ‘physician, heal thyself’ means that I

can’t help anybody else until I’m cool. And music is what cools me out.

I know that music heals me. And I hope my music is healing in some

respect to the listeners too. I try to think of that when I’m playing.

I want to heal people, soothe people. They come out to hear music,

they don’t wanna go away all jagged, you know.”

The soothing title track of Henderson’s latest as a leader, Oasis

(Sirocco Jazz), is a good case in point. A dark, mysterious ballad

performed on flugelhorn, Henderson’s warm-toned, plaintive lines are

echoed by vibist Joe Locke and underscored by pianist Kevin Hays’ gentle

arpeggios as the rhythm tandem of Billy Drummond and Ed Howard creates

subtle and spacious percussive colors underneath. On the other side of

the dynamic coin, “Sandstorm” captures all the kinetic energy of an

express train hurtling along the subway track at breakneck speed.

Drummond’s playing comes alive here with a bristling Max Roach-inspired

ride-cymbal pulse while Howard pushes the forward momentum with his

insistent walking bass lines as Hays delves into serious bebop mode.

Locke wails on top of this uptempo romp with blazing dexterity, while

Henderson’s bold, bright playing here speaks of his trumpet heroes:

Miles Davis, Freddie Hubbard, Clifford Brown. It’s a soundtrack to a

city-New York, not San Francisco.

Always mindful of providing tension and release, Henderson segues from

“Sandstorm”‘s aggressively boppish ride to a beautiful interpretation of

Wayne Shorter’s “Lost.” On Kevin Hays’ “Siddhartha,” he follows the

calming, Zenlike flow of that spacious melody with a dramatic use of

space on muted trumpet. The effect is very Miles-inspired, à la

“Flamenco Sketches” from Kind of Blue. Henderson’s own expansive,

open-ended “Desert Sun” recalls some of the sonic explorations from his

Mwandishi phase with Hancock. “That tune reflects the influence that I

got, in terms of concept, from the old Herbie Hancock sextet. I wanted

some of that aspect represented on this record.”

Elsewhere on Oasis-his seventh recording with the core group of Locke,

Hays and Howard, with Drummond replacing Lewis Nash in the

lineup-Henderson and crew turn in evocative renditions of George Cables’

gentle “Why Not,” Lee Morgan’s “Melancholy” and Herbie Hancock’s

“Cantaloupe Island,” done up in funky fashion with some noticeably

reconfigured harmonies. “I always try to use other people’s tunes,”

says Henderson. “Some records are just that artist, only his

compositions. But I like to incorporate other people’s tunes so that

the album has more balance and scope rather than just my one way of

looking at things. I like more or less collective input rather than a

self-portrait.”

His dramatic arrangement of “Melancholy” has a heavy spiritual vibe

running through it, almost in a “Go Down Moses” vein. “Well, I knew Lee

Morgan personally and I used to practice with him,” says Henderson.

“On this tune I was really trying to reflect that side of Lee. He could

be spirited and fiery but he also had this real beautiful, thoughtful

side.”

The earthy cover of “Cantaloupe Island,” he explains, came out of some

recent playing experiences with Hancock during his Gershwin’s World

tour. “We went out for about a year and a half and the tour finally

ended last September. It was supposed to be the Gershwin Project

representing his album, but the music really evolved way past that. By

the end of the tour it really reminded me of the old Herbie Hancock and

Mwandishi band that I played in about 30 years ago. The music went off

the music paper to where you’re experimenting like explorers or

travelers. It was a wonderful experience.”

The original Mwandishi band recently played a rare reunion concert in

San Francisco as a benefit for trombonist Julian Priester, who underwent

a liver transplant a year ago and exhausted his funds in the process.

(A review of the concert is posted on the “Live” section of www.jazztimes.com.)

As Henderson explains, “It was the old Herbie Hancock sextet: Buster

Williams, Julian, Benny Maupin, myself and Herbie. The one difference

was that Billy Hart wasn’t there, because he was in Japan, but Terri

Lynne Carrington filled in for him. And it was great. We hadn’t played

together in 27 years and it was like we never stopped.”

Henderson had originally met Hancock in the mid-1960s, when the pianist

was making jazz history with the Miles Davis quintet that also featured

Wayne Shorter, Ron Carter and Tony Williams. “I knew Herbie when he was

with Miles and all we talked about back then was cars because I loved

sports cars and he did too. And then in late 1969, when Herbie had his

sextet with Joe Henderson, Johnny Coles, Garnett Brown, Buster Williams

and Tootie Heath, he came to San Francisco to play a weeklong

engagement. And Johnny Coles was going on a sabbatical with Ray Charles

for six months so Herbie needed a trumpeter. He heard that I played

trumpet but I don’t think he took it seriously at first. But then he

tried me for that one week in San Francisco that they had, and it went

well because I was familiar with all of his music and he seemed to

appreciate the way I played. And that opened the door for me.”

Hancock must’ve intuitively sensed the Miles Davis influence in

Henderson’s playing. Henderson had, in fact, absorbed Miles’ repertoire

from the time he was a teenager and actually had gotten some valuable

trumpet playing tips from the maestro himself. “He used to stay at my

parents’ house when I was in high school,” says Henderson. “This was

when Miles had Cannonball and Coltrane in the band. I was studying

trumpet at the conservatory in San Francisco but when he took me to the

gig at the Blackhawk and I heard Trane and Cannonball with Philly Joe,

Paul Chambers and Wynton Kelly-it blew my mind. That was my first real

eye-opener to modern jazz. And I’ve been on the trail ever since.”

Henderson did have a previous eye-opening lesson or two with another

trumpet legend. “My first trumpet teacher in life was Louis Armstrong,”

he recalls. “My mother knew him because she was at the original Cotton

Club as a dancer. If you’ve ever seen that videotape of Fats Waller

playing and a real pretty lady is sitting on the piano bench with him,

singing ‘Ain’t Misbehavin” to him, that’s my mother. She knew everybody

in show business and she took me down to the Apollo in 1949 to meet

Louis Armstrong. I was just nine years old at the time and I didn’t

realize who he really was until I got older. But that’s how I started

playing the trumpet.”

But it was Miles who would make the biggest impression on Henderson.

“When I met Miles when I was 17 or 18, I played for him by ear

everything off Sketches of Spain. I had been practicing with the record

and when I finally played it for him I didn’t miss a note. I was so

proud of myself and when I finished I asked him, ‘How did you like

that?’ And he said, ‘You sound good, but that’s me!’ Which was another

eye-opener. That awareness was very important. And then he sat down

and showed me a few things, wrote on a little napkin certain

relationships about chords and things. But the most important part of

my learning from him was by listening to him and observing him, to

understand the etiquette of what you do and what you don’t do-and how to

leave space. A lot of good players are very good technically, but you

know-you can’t play all the time. You gotta take a breath or you’ll

overload the audience. That space is the pause that refreshes. And

also it energizes. It gives the music life-in-breathing and

out-breathing. That’s the key.”

In the ’70s, like his mentor Miles, Henderson got way into the fusion

thing by incorporating electronic exploration into the fabric of his

playing. That quality is readily apparent through his reverb-soaked

trumpet playing on Hancock’s Sextant album from 1972, but Henderson

pushes the envelope on his own mid-’70s recordings for Blue Note,

Sunburst and Heritage. “I played trumpet with wah-wah and all of those

albums and I really enjoyed it,” he says. “In fact, an album recently

came out in England (on Soul Brother Records) called Anthology, which is

a compilation of all of my hits from the fusion era. It’s funny but in

England, I’m like a rock star. I didn’t even know that but I did a

tour over there about a month and a half ago and it was amazing. I sold

out the biggest venue in London; there were mobs of people-just

unbelievable. For that tour they got an Echoplex for me, a phase

shifter, a wah-wah pedal. I like to use technology. I’ll use any tools

I can to explore the possibilities of sound.”

Henderson says his recent tour of England in support of the

fusion-oriented Anthology made him consider the possibility of

resurrecting the wah-wah sound once again. “That whole tour opened my

eyes to the fact that I don’t really want to be stuck in just one genre.

So I’m considering maybe updating some of those fusion things because

there’s a big audience for that still. And besides, I like to take

chances and use my imagination. I don’t want to just play jazz in a

traditional sense all the time. That’s cool too, but I also want to

represent that other side of me too.”

The medical practice might have to wait a little longer.

Gearbox

“For a while I was endorsing Selmer trumpets. I have two or three

Selmers and I also have two Martins, a Bach and a Schilke. All horns

are good but some people get fanatical about this mouthpiece or that

mouthpiece. An analogy that I like to make is something that Art Blakey

once told Clifford Brown. See, Clifford had chewing gum patching up

one of the middle valve casings and had a rubber band for the third

valve slide, and that’s the horn that sounded so golden! And one day

Blakey said, ‘Clifford, here’s $300, go get yourself a nice new shiny

horn.’ So Clifford said, ‘Thank you Mr. Blakey but the problem’s not

with the horn, the problem’s with me.’ Check that out! You have to

realize that you play the instrument, the instrument doesn’t play you.

Some people search a lifetime trying to find the top-of-the-line horn

but that’s wasting a lot of time. They should get home and be

practicing and stop worrying about the horn.

“Mouthpiece-wise, what I’ve been playing all my life feels comfortable

to me: a Bach 7C, Mount Vernon model. And only recently this mouthpiece

maker named Scott Holbert laid something on me. He’s a trumpet player

and he’s one of my fans so he looked at my mouthpiece and made me a new

one and sent it to me. And it really enhanced the sound. It’s similar

to the one I was always using but it’s state-of-the-art now. So that’s

cool, but I really don’t go around shopping for things.”

Listening Pleasures

“When I was coming up I used to listen to records and cop things off the

records all the time-innuendos, phrasings and licks and stuff. But I

don’t listen to records anymore. I do love classical music, which I

listen to on the radio. When I was competitive figure skating, the

music was always Stravinsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, things like that. I love

all types of music-Indian music, Chinese music, Japanese music,

Brazilian, Latin. The more music you’re exposed to the more it enhances

one’s vocabulary. I don’t just want to listen to, quote-unquote,

bebop. No, I love all kinds of music. But I don’t buy records anymore.

And I’m lucky enough to travel so much these days so when I’m in

different countries I like to go out and hear the musicians from that

country playing their music authentically.”

http://21cm.org/magazine/artist-exclusives/2018/03/08/a-conversation-with-dr-eddie-henderson/

A Conversation with Dr. Eddie Henderson

There’s a legend walking among us, and his name is Eddie Henderson.

Jazz aficionados will be familiar with Henderson and his associations with iconic artists, most notably Herbie Hancock throughout the 1970s. Known as “The Funk Surgeon,” Henderson also led a number of groups that played electric jazz and fusion – although the man eschews the kind of sub-categorizations to which jazz is prone; he prefers to think of it all under the umbrella of “ethnic improvised music.”

As impressive as Henderson’s playing is his seemingly endless supply of mind-boggling life stories. He grew up in the midst of the Harlem Renaissance with a mother who danced at the Cotton Club and a father who sang in The Charioteers. He took his first trumpet lesson with Louis Armstrong. He claims the title of the first African-American to compete in national figure skating championships. What else? He was also a practicing medical doctor throughout his early years of playing and touring with jazz greats.

During a recent visit to DePauw University, 21CM director Mark Rabideau got the chance to sit down with Eddie Henderson and hear some of his stories first-hand.

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS

On Eddie Henderson’s first trumpet lesson with Louis Armstrong…

My mother’s friends Lena Horne and Sarah Vaughan – I think they both took me to the Apollo Theater to hear Louis Armstrong. I really hadn’t heard of him. I do remember I could see [him] behind the curtain warming up. I thought, “Wow! He really has a big sound!”

So my mother took me backstage. That was my first lesson on the trumpet, on Louis Armstrong’s horn and his mouthpiece. He taught me how to make a sound.

My uncle Louie gave me his trumpet. I took lessons every week and studied very hard. After about a year I could play “Flight of the Bumblebee.” So my mother took me back to see Louis Armstrong. I remember his voice. He said, “Hey little Eddie, you still playing?” I grabbed his horn and played “Flight of the Bumblebee.” Louis Armstrong shrieked and fell out of his chair. He got up and said, “Hey little Eddie, that’s some of the baddest stuff I ever heard in my life!” Meaning good – I hope.

He told his wife to bring a book of ten of his solos transcribed. He wrote at the top, “To little Eddie, this is to warm your chops up. You sound wonderful, keep playing. Love, Satchmo.”

On a profound, early experience with Herbie Hancock…

After I finished medical school, I did my internship. The other doctors were going into specializations where you had four more years of being on call every other night. I was still playing every night. I came across psychiatry, which had an on-call schedule of one day every 45 days. So I picked psychiatry.

I did two years of that. In my last year – it was a three-year residency – Herbie Hancock, who I knew, came through San Francisco. He needed a trumpet player for a week. Somebody recommended me. He said, “Oh no, he’s a doctor.” They said, “Well, just give him a try.” That one week opened the door for me. All the musicians that I revered figured, well, Eddie plays with Herbie. His credentials must be in order. People like Dexter Gordon, Art Blakey, Elvin Jones, McCoy Tyner, Joe Henderson. They all started hiring me by virtue of the fact that I was affiliated with Herbie Hancock. So that changed my whole life. I went with Herbie – it was supposed to be one week. It turned into three and a half years.

I moved back to San Francisco and got a job at this doctor’s office. He gave me the option that I could work five days a week, four hours a day. If I got tours, I could go. He still paid me even though I wasn’t there. I had my cake and ate it. I was playing every night and practicing medicine four or five hours a day. I did that for 11 or 12 years.

On emulating your heroes and finding your own voice…

[Finding my voice] was a slow process. When I first met Miles Davis, I asked, “How do you play?” I had been imitating his solos. I asked him to listen to me. I put on his record and played with it. He said, “You sound good, but that’s me.” So, it’s fine to have influences. That’s the way he learned. But then you reach a point in life where you realize, who am I?

The next time Miles came to town, he said, “Hey Eddie, you still trying to sound like me?” But in the interim, I found out that his hero, who he imitated when he was just beginning, was a gentleman named Freddie Webster. Miles’s sound, style, conception, everything, was a sad carbon copy. So when [Davis] asked me [that], I said, “You mean Freddie Webster?”

The look on Miles Davis’s face was shock. He said, “Oh man, I didn’t know you was hip to that.” Then he smiled and said, “Everybody’s a thief. I just made a short-term loan.”

Everybody is a derivative of their predecessors. It’s so important to study the past before you can think about forging ahead. It’s a cumulative process. It’s a lineage.

On being a bandleader…

In the five years I played with Herbie [Hancock], he never told anybody how to play. If you have to tell them how to play, why hire them? If you hire race horses, let them run. That’s what I took away from my greatest experience, and the lesson given to me about going on in my future career. If you hire people, let them be themselves. Evolve together. It’s a collective effort when people play together. One person dictating – that limits it.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Trumpet Great Eddie Henderson with All-Star Quintet Mixes Burners and Ballads to Perfection Via ‘Shuffle and Deal’ (ALBUM REVIEW)

http://jazzbluesnews.com/2020/08/10/cd-review-eddie-henderson-shuffle-and-deal-2020-video-cd-cover/

CD review: Eddie Henderson – Shuffle and Deal 2020: Video, CD cover

It’s never been wise to bet against Eddie Henderson. Not that the trumpet great is a gambling man, despite what the jackpot ride and shades-masked poker face on the cover of his invigorating new album, Shuffle and Deal, might imply. “I play War, but that’s about it,” Henderson jokes. “I’m not sophisticated enough for more than ‘high card wins.’”

Henderson’s storied biography suggests otherwise. The son of a vocalist father and a mother who danced at the Cotton Club, young Eddie received his first trumpet lesson from Louis Armstrong. His parents’ coterie of friends included Miles Davis, who provided the fledgling trumpeter with some typically sharp-toned mentorship. Henderson’s own remarkable career has included tenures with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers and Herbie Hancock’s Mwandishi band along with his successful parallel life as a psychiatrist in the Bay Area.

Due out July 31 via Smoke Sessions Records, Shuffle and Deal finds Henderson turning over yet another winning hand. It doesn’t hurt that he arrived with four aces up his sleeve – namely, the members of his stellar quintet: pianist Kenny Barron, alto saxophonist Donald Harrison, bassist Gerald Cannon and drummer Mike Clark. Add the leader into the mix and you end up with an unbeatable royal flush.

The album features a mix of familiar standards and original compositions by both Henderson’s musical and actual families – in addition to pieces by Barron and Harrison, the repertoire also includes pieces by the trumpeter’s wife Natsuko Henderson and his daughter, musician and educator Cava Menzies. The collection adds up to a blend of identities and voices that Henderson likes to refer to as a “collective portrait.”

Released just in time for Henderson’s landmark 80th birthday, Shuffle and Deal reveals a master at the height of his powers, able to unleash blistering, agile runs on bop burners as well as explore ballads with an exquisite fragility (yet more evidence that a lack of sophistication isn’t what’s keeping him away from the card table). If anything about this date looks backwards through the trumpeter’s eight-decade history, it’s not the vitality of the playing but the structure of the program, which keeps an engaged audience firmly in mind throughout.

“I want the audience to really feel the music and start moving,” Henderson insists. “Jazz started as dance music in the first place, so I want to bring that element back into the music. The telltale common denominator when people are really enjoying themselves is when they feel like they want to get up and dance. Not the European concept of listening to music, just sitting still and static, shushing people and politely clapping at the end of the tune. No! I thought it was supposed to be fun. That’s the way I grew up.”

Henderson’s newly penned title track should do the trick from the outset, jolting listeners out of their chairs with its insinuating shuffle beat (the actual source of the album’s title). The feel of the tune was inspired by Henderson’s early mentor, in particular Miles’ shadowboxing rhythmic feel on Jack Johnson.

“Miles just had this aura when he played,” Henderson explains, citing the goal he envisioned when playing the tune. “In the liner notes to My Funny Valentine they used the word ‘duende,’ which refers to the presence that matadors have, like they could walk on eggshells without breaking them. It’s a master’s approach; it leaves an indelible imprint on your memory. I always have some ideal in my mind when I play. I close my eyes and there’s a blank screen, but I envision elegance and purity. So I know where I want to go, but I don’t know how I’m going to get there.”

Henderson described a similar approach to “Over the Rainbow,” which he was inspired to play after seeing Judy Garland perform the song in a documentary. The tragic life imbued the song with a very different meaning than it possessed in the more innocent and whimsical context of her original version in The Wizard of Oz. That emotional resonance makes it a perfect companion piece with “God Bless the Child,” which is impossible to imagine separate from Billie Holiday’s emotion-laden voice. Both are rendered with aching tenderness by Henderson and the quintet, held aloft by Clark’s delicate yet foundational brushwork.

Barron contributed two pieces to the album. The barbed “Flight Path” was the title track to the 1983 second album by his Monk-inspired quartet Sphere, while “Cook’s Bay” was originally recorded for 2000’s Spirit Song with Henderson on trumpet. The two men share a long history and a matchless chemistry, nowhere more gorgeously evident than on their intimate album-closing duet on Charlie Chaplin’s “Smile.”

“Kenny Barron is invaluable to me,” Henderson says. “He’s always right there, always supportive and knowing exactly what I need. It’s just like breathing in and breathing out with Kenny. It’s like he’s part of my thoughts.”

The album’s final standard is a lyrical evocation of the classic “It Might As Well Be Spring.” Menzies’ offering for the album is the smoldering, dark-hued “By Any Means,” which echoes the tone of “Nightride,” her contribution to Henderson’s previous album, Be Cool. “Both those tunes are mysterious,” her father laughs. “I guess she got the mysterious side of her character from me.”

A crisp call-and-response between Cannon and Clark ignites “Boom,” Natsuko Henderson’s soulful new piece. It’s as aptly named as “Burnin’,” reprised by Harrison from his own 2001 album Paradise Found (which introduced his young nephew Christian Scott on trumpet). Like much of the album, the tune was nailed in a single take – in this case, an off-the-cuff rendition captured when Harrison was unaware that tape was even rolling. “I thought we were just rehearsing,” he says, shrugging off the effortless brilliance of his sharp solo. “I thought we were just jiving around but everybody else thought it was killing.”

That modesty, belied by the compelling beauty of his playing on Shuffle and Deal, is typical of Henderson, who has always preferred to keep his cards close to his chest. That doesn’t seem likely to change as the trumpet maestro turns 80. “That just happens to be another inch along the way,” he says. “I’m not close to finished. I feel like I’m just beginning.”

01. Shuffle and Deal (5:30)

02. Flight Path (5:15)

03. Over the Rainbow (8:11)

04. By Any Means (3:15)

05. Cook’s Bay (7:20)

06. It Might as Well Be Spring (9:23)

07. Boom (4:04)

08. God Bless the Child (6:53)

09. Burnin’ (4:57)

10. Smile (4:14)

Eddie Henderson – trumpet

Donald Harrison- alto sax

Kenny Barron -piano

Gerald Cannon – bass

Mike Clark – drums

https://downbeat.com/reviews/detail/collective-portrait

Eddie Henderson was a formidable presence in San Francisco’s thriving fusion scene in the 1970s. Known back then as “Dr. Trumpet” (he worked part-time as a psychiatrist when not on tour with the likes of Herbie Hancock and Art Blakey), Henderson has long since given up his medical practice, but he hasn’t finished experimenting. On Collective Portrait, the fiery-toned trumpeter revisits 10 fusion classics in an intimate, small-ensemble setting. By removing these tunes from their familiar context, the musicians—Gary Bartz on alto saxophone, George Cables on piano and Fender Rhodes, Doug Weiss on bass and Carl Allen on drums—are able to freely explore the melodic aspects of the material. This is no easy task because fusion, with its high-energy vamps and complex melodies, almost beckons for electronic enhancement. But here, Henderson and his crew provide all the power needed. A new version of Cables’ “Morning Song,” originally recorded in 1979 with electric piano and electric bass, sustains a groove courtesy of Weiss’ upright acoustic bass and Cables’ bouncy left-hand piano line. On the Woody Shaw tune “Zoltan,” it’s Allen who serves as band’s dynamo, weaving together three distinct rhythms with equal poise: a rat-a-tat shuffle, a Latin-funk groove and straightahead swing. Solo turns by each of the members provide another jolt of energy. Henderson’s take on “Beyond Forever” finds the one-time hard-bopper leaping through the upper registers of his horn, and Bartz’s blend of bebop and modal idioms on “Gingerbread Boy” floats effortlessly atop the tune’s driving swing feel. Even the album’s slower tracks—the ballads “You Know I Care,” “Together” and “Spring”—are brimming with energy, though on a quieter, more refined scale. With Collective Portrait, Henderson demonstrates that in the right hands, and with the right touch, any song can become timeless.

Eddie Henderson (musician)

Role: Jazz trumpeter

May 7, 2018

Alchetron

Education San Francisco Conservatory of Music, Howard University, University of California, Berkeley

Eddie Henderson (born October 26, 1940) is an American jazz trumpet and flugelhorn player. He came to prominence in the early 1970s as a member of pianist Herbie Hancock's band, going on to lead his own electric/fusion groups through the decade. Henderson earned his medical degree and worked a parallel career as a psychiatrist and musician, turning back to acoustic jazz by the 1990s.

Henderson's influences include Booker Little, Clifford Brown, Woody Shaw, and Miles Davis.

Ronald D. Henderson (deceased), Kenneth C. Henderson of Norwalk Connecticut, Cava Menzies of Oakland California

Family influence and early music history

Henderson's

mother was one of the dancers in the original Cotton Club. She had a

twin sister, and they were called The Brown Twins. They would dance with

Bill "Bojangles" Robinson and the Nicholas Brothers. In the film

showing Fats Waller playing "Ain't Misbehavin'", Henderson's mother sat

on the piano whilst Waller sang to her. His father sang with Billy

Williams and The Charioteers, a popular singing group

|

At the age of nine he was given an informal lesson by Louis Armstrong, and he continued to study the instrument as a teenager in San Francisco, where he grew up, after his family moved there in 1954, at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. As a young man, he performed with the San Francisco Conservatory Symphony Orchestra.

Henderson was

influenced by the early fusion work of jazz musician Miles Davis, who

was a friend of his parents. They met in 1957 when Henderson was aged

seventeen, and played a gig together

After completing his medical education, Henderson went back to the Bay area for his medical internship and residency - and the break that thrust him fully into music. It was a week-long gig with Herbie Hancock's Mwandishi band that led to a three-year job, lasting from 1970-73. In addition to the three albums recorded by the group under Hancock's name, Henderson recorded his first two albums, Realization (1972) and Inside Out (1973), with Hancock and the Mwandishi group.

After leaving Hancock, the trumpeter worked extensively with Pharoah Sanders, Mike Nock, Norman Connors, and Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, returning to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1975 where he joined the Latin-jazz group Azteca, and fronted his own bands. He also recorded with Charles Earland (popular for his version of "Let the Music Play" in 1978), and later, in the 1970s, led a rock-oriented group. While he gained some recognition for his work with the Herbie Hancock Sextet (1970–1973), his own records were considered too "commercial".

Medical Career

After three years in the Air Force, Henderson enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, graduating with a B.S. in zoology in 1964. He then studied medicine at Howard University in Washington D.C., graduating in 1968. Though he undertook his residency in psychiatry, he practiced general medicine from 1975 to 1985 in San Francisco, part-time for about four hours a day working at a small clinic. Henderson said, "The head doctor knew I was into music and he hired me with the stipulation that whenever I get tours I can go and come as I please. They would even pay me when I was gone. It was lovely", he recalled. "I just wanted to play music. But I never in my wildest dreams thought I'd ever have a chance to play with the big guys."

In the 1970s, Henderson recorded a series of fusion albums during the disco era that were later re-released. He recorded two albums on the Blue Note label, Sunburst (1975) and Heritage (1976); three for Capitol Records, Comin' Thru (1977), Mahal (1978) and Runnin' to Your Love (1979); and two for Capricorn Records, Realization (1973) and Inside Out (1974).

UK Success

Henderson's only UK hit was the single "Prance On" recorded for Capitol which reached No. 44 in the UK Singles Chart in November 1978. The newly introduced 12" vinyl single format for this track helped promote it on the disco/club scene at the time. His previous single recorded in 1977, "Say You Will" / "The Funk Surgeon" failed to chart in the UK. "Cyclops" was an instrumental LP track only, although it was so popular at the wrong speed that Capitol pressed a 12" vinyl single with the regular version, and the fast version, back to back.

Recent work and influences

In the 1990s, he returned to playing acoustic hard bop, touring with Billy Harper in 1991 while also working as a physician.

In

recent years Henderson has played at festivals in France and Austria.

In May 2002, Henderson recorded an album of Miles Davis compositions,

called So What?. The group included Bob Berg on sax, Dave Kikoski on piano, Ed Howard on bass and Victor Lewis on drums.

Henderson's fusion period has also been revisited in a live setting in the last few years, having played the UK and Europe to positive reviews, most notably his two night stint at the Jazz Café in London being cited by Blues & Soul Magazine as one of the concerts of the year. His backing band for these concerts was a UK band called Mr. Gone. The musicians in the band, at various points, included Simon Bramley on electric bass, Phil Nelson on drums, Tommy Emmerton on guitar, Neil Burditt on keyboards, Robin Jones on percussion and Jamie Harris on saxophone.

Recent recordings by Henderson have included Oasis (2001 on Sirocco Jazz Limited label), So What?, a tribute to Miles Davis (2002, EPC, Sony, Columbia), Time and Spaces (2004 Sirocco Jazz Limited), Manhattan Blue (2005, unreleased), Precious Moment (2006 on the Kind of Blue label) and For All We Know (2010 Furthermore Recordings).

The composer of Tender You, Precious Moment, Around the World in 3/4 and Be Cool is his wife, Natsuko Henderson.

Henderson is a faculty member of Juilliard music school since 2007 and is Associate Professor of Trumpet at the Oberlin Conservatory jazz department, beginning in 2014.

As leader

Compilations

As sideman

References

After completing his medical education, Henderson went back to the Bay area for his medical internship and residency - and the break that thrust him fully into music. It was a week-long gig with Herbie Hancock's Mwandishi band that led to a three-year job, lasting from 1970-73. In addition to the three albums recorded by the group under Hancock's name, Henderson recorded his first two albums, Realization (1972) and Inside Out (1973), with Hancock and the Mwandishi group.

After

leaving Hancock, the trumpeter worked extensively with Pharoah Sanders,

Mike Nock, Norman Connors, and Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, returning

to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1975 where he joined the Latin-jazz

group Azteca, and fronted his own bands. He also recorded with Charles

Earland (popular for his version of "Let the Music Play" in 1978), and

later, in the 1970s, led a rock-oriented group. While he gained some

recognition for his work with the Herbie Hancock Sextet (1970–1973), his

own records were considered too "commercial".

Medical Career

After three years in the Air Force, Henderson enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, graduating with a B.S. in zoology in 1964. He then studied medicine at Howard University in Washington D.C., graduating in 1968. Though he undertook his residency in psychiatry, he practiced general medicine from 1975 to 1985 in San Francisco, part-time for about four hours a day working at a small clinic. Henderson said, "The head doctor knew I was into music and he hired me with the stipulation that whenever I get tours I can go and come as I please. They would even pay me when I was gone. It was lovely", he recalled. "I just wanted to play music. But I never in my wildest dreams thought I'd ever have a chance to play with the big guys."

In the 1970s, Henderson recorded a series of fusion albums during the disco era that were later re-released. He recorded two albums on the Blue Note label, Sunburst (1975) and Heritage (1976); three for Capitol Records, Comin' Thru (1977), Mahal (1978) and Runnin' to Your Love (1979); and two for Capricorn Records, Realization (1973) and Inside Out (1974).

UK Success

Henderson's only UK hit was the single "Prance On" recorded for Capitol which reached No. 44 in the UK Singles Chart in November 1978. The newly introduced 12" vinyl single format for this track helped promote it on the disco/club scene at the time. His previous single recorded in 1977, "Say You Will" / "The Funk Surgeon" failed to chart in the UK. "Cyclops" was an instrumental LP track only, although it was so popular at the wrong speed that Capitol pressed a 12" vinyl single with the regular version, and the fast version, back to back.

Recent work and influences

In the 1990s, he returned to playing acoustic hard bop, touring with Billy Harper in 1991 while also working as a physician.

In recent years Henderson has played at festivals in France and Austria. In May 2002, Henderson recorded an album of Miles Davis compositions, called So What?. The group included Bob Berg on sax, Dave Kikoski on piano, Ed Howard on bass and Victor Lewis on drums.

https://www.namm.org/library/oral-history/eddie-hendersonThe 2 Lives of Eddie Henderson

by Mike Zwerin

International Herald Tribune

Eddie Henderson was 9 and was practicing scales on his trumpet one day when Louis Armstrong came by to visit his folks. Satchmo taught the kid a few tricks.

By the time he came around again a year or so later, Eddie was playing "The Flight of the Bumble Bee." Armstrong was so impressed that he fell backward into a chair, laughing. Exclaiming some version of "that's some of the baddest stuff I ever heard," he dedicated a copy of a transcribed collection of his solos: "To little Eddie. You sure sound good. This is to warm your chops up." Henderson still has the book.

His mother was in the original Cotton Club Revue in Harlem, billed with her twin sister as the Brown Twins, and she was Bill (Bojangles) Robinson's dancing partner. His father, Billy Williams, led a group called The Charioteers. As a child, Henderson thought celebrities like Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Fats Waller, who would visit his parents when they were in New York, were "just normal people."

Do not confuse Eddie Henderson with (no relation) notables with the same surname, like Fletcher, Horace and Joe. Musically, Eddie combines an unmistakable personality with, at the age of 57, an unusual supply of vim and vigor. And biographically his is not exactly a "normal" tale. At first he'd wanted to play the clarinet, but his school only had violins and accordions. He said "the heck with that stuff." His mother's brother owned a trumpet.

His father died, and when his mother married a doctor in San Francisco some years later, they moved out west. His stepfather had many musician patients, Miles Davis among them. The patients were often houseguests. Miles asked Eddie what he wanted to do in life. "I play the trumpet," he answered. Miles lay back and looked him over. "I bet you do," he said.

When he was 18, Miles took him to a concert. It was the band with Coltrane, Cannonball, Philly Joe Jones, Paul Chambers and Wynton Kelly. Henderson had never heard "the real deal" up close like that.

Then he learned the trumpet solos on "Sketches of Spain" and "Kind of Blue," playing them by ear along with the records, and by the time Miles returned to San Francisco, he knew them by heart. "How did you like that?" the cocky teenager asked after not missing a note. Miles looked at him and said: "You sound good. But that's me."

It was like being hit on the head by a baseball bat. All of a sudden, he knew the meaning of paying dues, and he he had not even started yet. His stepfather influenced him to study medicine.

After undergraduate work at the University of California at Berkeley, he went on to medical school at Howard University in Washington, following that with a residency in psychiatry. While studying at Howard, he would run up to New York on weekends to talk trumpet and play with Freddie Hubbard and Lee Morgan. He only graduated from med school "by the grace of God."

"People ask me, 'How can you be a doctor and a musician at the same time?' It boils down to good study habits, organization, self-discipline and energy. I went to sleep at 5 and got up at 7. I was just 23. I never missed a class. Not one. You might say I was focused."

He played with Herbie Hancock and Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers but "the money was funny" with the latter so he quit and moved back to San Francisco. He practiced medicine for 10 years in this little clinic a surgeon friend of his ran: "It was like four hours a day. I could come and go as I wanted when I had a gig or a tour."

There is only a smidgeon of a smile as he says: "A monkey could be a doctor. I'm not kidding. You just have to go to school. But I also have a personality. I'm not just a doctor, I am an individual. I want to express . . . me, myself. You cannot learn that in school. Music was always my main thing.

"You know that old adage? 'Physician, heal thyself'? How can I help anybody else unless I'm cool with myself? And music is what cools me out. When I had a chance to go with Herbie Hancock, I said 'Yeah!' There was no question in my mind, no hesitation: 'I'm going. Right away."'

He never practiced psychiatry as a specialty: "That's like doing construction work. It's emotionally and physically depleting. But I did have a residency for awhile. I would ask patients, 'What seems to be wrong today?' and they'd say, 'Well, you're the doctor. You tell me.' They played all those mind games.

"Basically, I just wanted people to come in and say 'ah' and not bother me. I didn't have any time for head trips. Everybody in San Francisco knew I played music. People would come to my office and the nurse's aid would say: 'He's in the back practicing. He's got a gig tonight. Don't bother him. If his chops aren't right he's unhappy.' That's the kind of lifestyle I had."

Meanwhile, on the free-market end of the great wide world of jazz, Henderson was discussing Ferraris with Miles Davis. Miles owned one. He owned three ("I've never had trouble with bread"). Practicing medicine in his surgeon friend's clinic four hours a day while playing with people like Jackie McLean and Roy Haynes was "like a dream."

He has just finished a Gershwin recording with Hancock and next month he'll play for two weeks with Elvin Jones during the Umbria Jazz Festival in Perugia, Italy.

When people ask him: "Do you still practice, Eddie?" they mean medicine. But when he answers "Yeah, every day," he's talking about the trumpet.

Throughout history, music always reflects what is happening in society at that time."

Eddie Henderson: Dr. Jazzman

Eddie Henderson is one of today's top and most original jazz trumpet players. Henderson was born in NYC in 1940. His father sang with the Charioteers, and his mother danced as one of the Brown twins at the Cotton club. Louis Armstrong gave Eddie his first few trumpet lessons at the age of nine. Eddie moved with his family to San Francisco when he was 14 years old. He studied at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music from 1954 to '57. Around 1956, Miles Davis was guest at Eddie Henderson's home during a black Hawk Jazz Club gig and was impressed with Eddie's ability to perform his famous "Sketches of Spain" without a fluff but encouraged Henderson to seek his own originality. Following Air Force service from 1958 to '61, Eddie became the first African American to compete for the National figure skating Championship, winning the pacific and Midwestern titles. The year 1961 was the beginning of Eddie pursuing dual careers-medicine and music. After receiving a bachelor of science in Zoology at the University of California at Berkeley in 1964,he got his M.D. at Howard university Medical School in 1968.

Eddie interned at San Francisco's French Hospital during 1968 and '69 and undertook a two-year residency in psychiatry at the University of California hospital from 1969 to '71. Henderson first got worldwide recognition for his jazz-trumpet playing from the popular recordings he made with Herbie Hancock's Mwandishi group during the early '70s. other jazz perfomers Eddie has played with include Pharoah Sanders, Art Blakey, Elvin Jones, Johnny Griffin, Slide Hampton, McCoy Tyner, Benny Golson, Max Roach, Jackie McClean, Dexter Gordon, Roy Haynes, Joe Henderson etc. Henderson has been on the faculty at Juillard school of music since 2007 and Oberlin University jazz department faculty since 2014. His discography consists of albums under his name on Capricorn, Blue Note, Capital, Columbia, Steeplechase, Sirocco, Kind of Blue, Furthermore and Smoke records.

Special Thanks: Natsuko Henderson

How has the Jazz music (and people of) influenced your views of the world and the journeys you’ve taken?

It has opened my eyes to the possibilities in life.

How do you describe your sound and music philosophy? What touched (emotionally) you from the sound of trumpet?

First of all, Miles Davis' sound inspired me. Then I became attracted to Freddie Hubbard and Lee Morgan's sound. I tried to make my sound combination of all three.

Which meetings have been the most important experiences for you? What was the best advice anyone ever gave you?

My first experience to play with Herbie Hancock's sextet. The best advice I've received was from Miles Davis when he told me to get my own style.

Are there any memories from gigs, jams, tours and studio sessions which you’d like to share with us?

All of the above have contributed to my development as an artist.

What do you miss most nowadays from the Jazz of the past? What are your hopes and fears for the future of?

In the past, musicians shared ideas and more than they do nowadays. My hopes are that there are more opportunities for musicians coming out of the various music schools.

"My first experience to play with Herbie Hancock's sextet. The best advice I've received was from Miles Davis when he told me to get my own style."

(Photo: Eddie Henderson)

What are some of the most important lessons you have learned from your experience in music paths?

Practice makes perfect and it is most important to play with best musicians possible.

What is the impact of Jazz on the socio-cultural implications? How do you want it to affect people?

Throughout history, music always reflects what is happening in society at that time.

The Doctor Is In: Eddie Henderson On Life As 'The Funk Surgeon'

Eddie Henderson has just released what he considers an audio autobiography, an album that covers many of the tunes he's played through his career. It's called Collective Portrait, and as he tells NPR's Arun Rath, it's brought out a lot of old memories –- like the time when he was 9 years old and his mother and Sarah Vaughan took him to see Louis Armstrong at The Apollo Theater.

"They took me backstage; Louis Armstrong gave me my first lesson, on his horn and mouthpiece, of how to make a sound on the trumpet," he says. "I had no idea of the stature of this gentleman; you know, I was just 9 years old. I really didn't know that trumpet was gonna turn into the rest of my life."

People hearing Henderson for the first time on Collective Portrait might get the impression that he's a fairly traditional jazz musician. Fans, however, have known him to get into some pretty funky electric music. When he answered a call from Herbie Hancock for a one-week gig, he ended up as part of the Mwandishi group Hancock would lead through the early 1970s.

Henderson's nickname, The Funk Surgeon, owes to that side of his career — and to the fact that he actually holds a medical degree. After the Mwandishi group broke up, he got a job at a doctor's office in San Francisco, though he did set one condition: "I told him I would like to work at his office and help him, but my real love was music, and if I ever got a tour I'd have to go."

As it turned out, the music came to him. Henderson ended up treating the jazz great Thelonious Monk as a patient, when the latter was struggling with his mental health.

"They

really didn't know what to do with this gentleman. He gave them a fit,"

Henderson says. "After they found out that I knew who he was, they

allowed me to take him to his gigs. It was just a little bizarre; that's

the best way I can put it."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eddie_Henderson_(musician)

Eddie Henderson (musician)

Eddie Henderson (born October 26, 1940) is an American jazz trumpet and flugelhorn player. He came to prominence in the early 1970s as a member of pianist Herbie Hancock's band, going on to lead his own electric/fusion groups through the decade. Henderson earned his medical degree and worked a parallel career as a psychiatrist and musician, turning back to acoustic jazz by the 1990s.

Henderson's influences include Booker Little, Clifford Brown, Woody Shaw, and Miles Davis.

Family influence and early music history

Henderson's mother was one of the dancers in the original Cotton Club. She had a twin sister, and they were called The Brown Twins. They would dance with Bill "Bojangles" Robinson and the Nicholas Brothers. In the film showing Fats Waller playing "Ain't Misbehavin'", Henderson's mother sat on the piano whilst Waller sang to her. His father sang with Billy Williams and The Charioteers, a popular singing group.

At the age of nine he was given an informal lesson by Louis Armstrong, and he continued to study the instrument as a teenager in San Francisco, where he grew up, after his family moved there in 1954, at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music.[1] As a young man, he performed with the San Francisco Conservatory Symphony Orchestra.

Henderson was influenced by the early fusion work of jazz musician Miles Davis, who was a friend of his parents.[1] They met in 1957 when Henderson was aged seventeen, and played a gig together.

After completing his medical education, Henderson went back to the Bay area for his medical internship and residency - and the break that thrust him fully into music. It was a week-long gig with Herbie Hancock's Mwandishi band that led to a three-year job, lasting from 1970-73. In addition to the three albums recorded by the group under Hancock's name, Henderson recorded his first two albums, Realization (1972) and Inside Out (1973), with Hancock and the Mwandishi group.

After leaving Hancock, the trumpeter worked extensively with Pharoah Sanders, Mike Nock, Norman Connors, and Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, returning to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1975 where he joined the Latin-jazz group Azteca, and fronted his own bands. He also recorded with Charles Earland (popular for his version of "Let the Music Play" in 1978), and later, in the 1970s, led a rock-oriented group. While he gained some recognition for his work with the Herbie Hancock Sextet (1970–1973), his own records were considered too "commercial".[2]

Medical career

After three years in the Air Force, Henderson enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, graduating with a B.S. in zoology in 1964. He then studied medicine at Howard University in Washington D.C., graduating in 1968. Though he undertook his residency in psychiatry, he practiced general medicine[3] from 1975 to 1985 in San Francisco, part-time for about four hours a day working at a small clinic. Henderson said, "The head doctor knew I was into music and he hired me with the stipulation that whenever I get tours I can go and come as I please. They would even pay me when I was gone. It was lovely", he recalled. "I just wanted to play music. But I never in my wildest dreams thought I'd ever have a chance to play with the big guys."

In the 1970s, Henderson recorded a series of fusion albums during the disco era that were later re-released. He recorded two albums on the Blue Note label, Sunburst (1975) and Heritage (1976); three for Capitol Records, Comin' Thru (1977), Mahal (1978) and Runnin' to Your Love (1979); and two for Capricorn Records, Realization (1973) and Inside Out (1974).

UK success

Henderson's only UK hit was the single "Prance On" recorded for Capitol which reached No. 44 in the UK Singles Chart in November 1978.[4] The newly introduced 12" vinyl single format for this track helped promote it on the disco/club scene at the time. His previous single recorded in 1977, "Say You Will" / "The Funk Surgeon" failed to chart in the UK. "Cyclops" was an instrumental LP track only, although it was so popular at the wrong speed that Capitol pressed a 12" vinyl single with the regular version, and the fast version, back to back.[citation needed]

In the 1990s, he returned to playing acoustic hard bop, touring with Billy Harper in 1991 while also working as a physician. In May 2002, he recorded So What?, an album of Miles Davis compositions, with Bob Berg on sax, Dave Kikoski on piano, Ed Howard on bass, and Victor Lewis on drums.

Discography

As leader

- Realization (Capricorn, 1973)

- Inside Out (Capricorn, 1974)

- Sunburst (Blue Note, 1975)

- Heritage (Blue Note, 1976)

- Comin' Through (Capitol, 1977)

- Mahal (Capitol, 1978)

- Runnin' to Your Love (Capitol, 1979)

- Phantoms (SteepleChase, 1989)

- Think On Me (SteepleChase, 1990)

- Colors of Manhattan with Laurent De Wilde (Gazebo, 1990)

- Flight of Mind (SteepleChase, 1991)

- Manhattan in Blue (Videoarts, 1994)

- Inspiration (Milestone, 1995)

- Tribute to Lee Morgan with Joe Lovano, Cedar Walton, Grover Washington Jr. (NYC, 1995)

- Dark Shadows (Milestone, 1996)

- Reemergence (Sharp Nine, 1998)

- Oasis (Sirocco, 2001)

- So What (Eighty-Eight's, 2002)

- Time & Spaces (Sirocco, 2004)

- Echoes (Marge, 2004)

- Precious Moment (Kind of Blue, 2006)

- Dreams of Gershwin (Videoarts, 2010)

- For All We Know (Furthermore, 2010)

- Collective Portrait (Smoke Sessions, 2015)

- Be Cool (Smoke Sessions, 2018)

- Shuffle and Deal (Smoke Sessions, 2020)

As sideman

With Kenny Barron

- Live at Fat Tuesdays (Enja, 1988)

- Quickstep (Enja, 1991)

- Things Unseen (Gitanes Jazz, 1997)

- Spirit Song (Verve, 2000)

With Gary Bartz

- Dance of Magic (Cobblestone, 1975)

- Music Is My Sanctuary (Capitol, 1977)

- Reflections On Monk (SteepleChase, 1989)

- The Red and Orange Poems (Atlantic, 1994)

With Norman Connors

- Dance of Magic (Cobblestone, 1972)

- Dark of Light (Cobblestone, 1973)

- Love from the Sun (Buddah, 1973)

- Slew Foot (Buddah, 1974)

- Saturday Night Special (Buddah, 1975)

- Invitation (Arista, 1979)

With The Cookers

- Cast the First Stone (Plus Loin Music, 2010)

- Warriors (Jazz Legacy, 2011)

- Believe (Motema, 2012)

- Time and Time Again (Motema, 2014)

- The Call of the Wild and Peaceful Heart (Smoke Sessions, 2016)

With Stanley Cowell

- Talkin' 'Bout Love (Galaxy, 1977)

- New World (Galaxy, 1981)

- Setup (SteepleChase, 1994)

With Benny Golson

- I Remember Miles (Alfa, 1993)

- Terminal 1 (Concord Jazz, 2004)

- New Time, New 'Tet (Concord Jazz, 2009)

With Herbie Hancock

- Mwandishi

- Crossings (Warner Bros. 1972)

- Sextant (CBS, 1973)

- V.S.O.P. (Columbia, 1977)

- Gershwin's World (Verve, 1998)

With Billy Harper

- Live on Tour in the Far East (SteepleChase, 1992)

- Live on Tour in the Far East Vol. 2 (SteepleChase, 1993)

- Somalia(Omagatoki, 1994)

- Live on Tour in the Far East Vol. 3 (SteepleChase, 1995)

- Destiny Is Yours (SteepleChase, 1990)

- If Our Hearts Could Only See (DIW, 1997)

- Soul of an Angel (Metropolitan, 2000)

With others

- Mina Aoe, The Shadow of Love (Victor, 1993)

- Dale Barlow, Hipnotation Spiral (Scratch, 1991)

- Bill Barron, Higher Ground (Joken 2 1993)

- T. K. Blue, Another Blue (Arkadia Jazz, 1999)

- Donald Brown, Sources of Inspiration (Muse, 1990)

- George Cables, Morning Song

- Joe Chambers, Mirrors (Blue Note, 1998)

- Jimmy Cobb, Remembering Miles (Eighty-Eight's, 2011)

- Michael Davis, Trumpets Eleven (Hip-Bone, 2003)

- Richard Davis, Fancy Free (Galaxy, 1977)

- Richard Davis, Way Out West (Muse, 1980)

- Steve Davis, Say When (Smoke Sessions, 2015)

- Laurent de Wilde, Off the Boat (Ida, 1988)

- Dilba, Dilba (WEA, 1996)

- Will Downing, A Dream Fulfilled (Island, 1991)

- Ray Drummond, Maya's Dance (Nilva, 1989)

- Charles Earland, Leaving This Planet (Prestige, 1974)

- Charles Earland, The Dynamite Brothers (Prestige, 1974)

- Ilhan Ersahin, She Said (Pozitif Muzik Yapim 1996)

- Ilhan Ersahin, Silver (Nublu, 2019)

- Pete Escovedo & Sheila Escovedo, Happy Together (Fantasy, 1978)

- Joe Farnsworth, Beautiful Friendship (Criss Cross, 1998)

- John Farnsworth, The Good Life (Smoke Sessions, 2010)

- Sonny Fortune, From Now On (Blue Note, 1996)

- Rick Germanson, Live at Smalls (SmallsLIVE, 2011)

- Winard Harper, Be Yourself (Epicure, 1994)

- Billy Hart, Enchance (Horizon, 1977)

- Billy Hart, Rah (Gramavision, 1988)

- Kevin Hays, Sweet Ear (SteepleChase, 1991)

- Bertha Hope, Elmo's Fire (SteepleChase, 1991)

- J. J. Johnson, The Brass Orchestra (Verve, 1997)

- Willie Jones III, Groundwork (WJ3, 2015)

- Willie Jones III, My Point Is... (WJ3, 2017)

- Azar Lawrence, Mystic Journey (Furthermore, 2010)

- Babatunde Lea, Levels of Conciousness (Theresa, 1979)

- The Leaders, Spirits Alike (Double Moon, 2006)

- Victor Lewis, Know It Today, Know It Tomorrow (Red 1993)

- Bennie Maupin, Slow Traffic to the Right (Mercury, 1977)

- Ron McClure, Never Forget (SteepleChase, 1991)

- Mingus Big Band, Live in Tokyo (Sunnyside, 2006)

- Butch Morris, Nublu Orchestra Conducted by Butch Morris (Nublu, 2006)

- Mulgrew Miller, Hand in Hand (BMG/RCA, 1993)

- Nicholas Payton, Lew Soloff, Tom Harrell, Eddie Henderson, Trumpet Legacy (Milestone, 1998)

- Courtney Pine, Modern Day Jazz Stories (Antilles, 1995)

- Martha Reeves, Gotta Keep Moving (Fantasy, 1980)

- Justin Robinson, Just in Time (Verve, 1992)

- Pharoah Sanders, Journey to the One (Theresa, 1980)

- Sonny Simmons, Mixolydis (Marge, 2002)

- Archie Shepp, Something to Live For (Timeless, 1997)

- Jarek Smietana, Live at the Jazz Jamboree (GOWI, 1996)

- Jarek Smietana, Autumn Suite (JSR, 2006)

- Bill Stewart, Snide Remarks (Blue Note, 1995)

- Buddy Terry, Lean On Him (Mainstream, 1972)

- Buddy Terry, Pure Dynamite (Mainstream, 1972)

- John Thompson, Romantic Night (AMH 2002)

- McCoy Tyner, Journey (Verve/Birdology 1993)

- Roseanna Vitro, Catchin' Some Rays (Telarc, 1997)

- Mal Waldron, My Dear Family (Alfa, 1994)

- Tim Warfield, Spherical (Criss Cross, 2015)

- Grover Washington Jr., All My Tomorrows (Columbia, 1994)

- Wax Poetic, Three (Doublemoon, 1998)

- Buster Williams, Dreams Come True (Buddah, 1980)

- Lenny Williams, Rise Sleeping Beauty (Motown, 1975)

- Gerald Wilson, New York, New Sound (Mack Avenue, 2003)

- Gerald Wilson, In My Time (Mack Avenue, 2005)

- Leon Thomas Precious Energy (Mapleshade, 1990)

- Pete Yellin, Dance of Allegra (Mainstream, 1972)

- Pete Yellin, Mellow Soul (Metropolitan, 1998)

- Denny Zeitlin, Invasion of the Body Snatchers (United Artists, 1978)

References

- Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). London: Guinness World Records Limited. p. 250. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

External links

- Eddie Henderson discography at Discogs

Music Review

Looking Back, a Horn Player Dips Into Every Mood

Past the midpoint of his second set at Smoke on Friday night, the trumpeter Eddie Henderson announced the first composition he ever wrote, a dose of drifting intrigue titled “Dreams.” His preamble almost could have seemed sheepish, coming from someone else: “I’m not really a composer,” he said. “I just write sketches, and let the band fill them in.”

But then Mr. Henderson doesn’t do sheepish. A jazz-funk paragon, a hard-bop survivor and an inveterate swashbuckler on the horn, he also carries himself with a confidence born of other ventures, like his years as a doctor, and his youthful distinction as a trailblazing African-American figure skater. At 74, he exudes a self-secure authority rooted in experience on and off the stage.

He has a strong new studio album — “Collective Portrait,” due out Tuesday on the Smoke Sessions label — that can be understood as a selective rumination on the breadth of his career. It makes no allusion to his roles in Mwandishi, Herbie Hancock’s lionized early fusion band, or the Cookers, a present-day postbop superhero squad. But its track list includes “Dreams,” along with several pieces from Mr. Henderson’s crossover albums of the 1970s, and tunes associated with his chief trumpet lodestars, Freddie Hubbard, Miles Davis and Woody Shaw.

Perhaps more significant, its personnel features the impeccable pianist George Cables and the intently soulful alto saxophonist Gary Bartz, working colleagues of Mr. Henderson’s for about the last 40 years. Both were on hand for his weekend run at Smoke, in a quintet expertly anchored by Doug Weiss on bass and Billy Drummond on drums. (Mr. Weiss appears on the album, with another fine drummer, Carl Allen.)

This set opened with “Sunburst,” the title track of a jazz-funk album Mr. Henderson released on Blue Note in 1975. The only concession to that lineage in this new arrangement was a Fender Rhodes piano played, with chiming cool, by Mr. Cables. And the following tune — “Morning Song,” a funk ballad by Mr. Cables, first heard on Mr. Henderson’s 1977 crossover album “Comin’ Through” — was remade as an acoustic soul-jazz number, buoyant and bittersweet.

On these and the other tunes in the set, including the Duke Pearson ballad “You Know I Care,” the older musicians in the band gave what amounted to a master class. Mr. Bartz played the seeker, turning most of his solos into fluttery expeditions, with a phrasing that conveyed momentum even when it sat behind the beat. Mr. Cables took an adaptable approach, flowing through the material with eloquent refinement and not a small amount of the blues.

And Mr.

Henderson kept his ironclad composure, whether he was charging through

his postbop cadences or tracing a more delicate melodic arc. There was

too much reverb on his microphone, and he occasionally reverted to

trusted patterns in his improvising. But he cut a commanding figure

whenever he played — and no less when he was just standing and nodding

in the background, watching the action unfold.

http://jazztrumpetproject.blogspot.com/2010/07/my-lesson-with-eddie-henderson.html

MONDAY, JULY 26, 2010