SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2020

VOLUME NINE NUMBER ONE

BRIAN BLADE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

SULLIVAN FORTNER

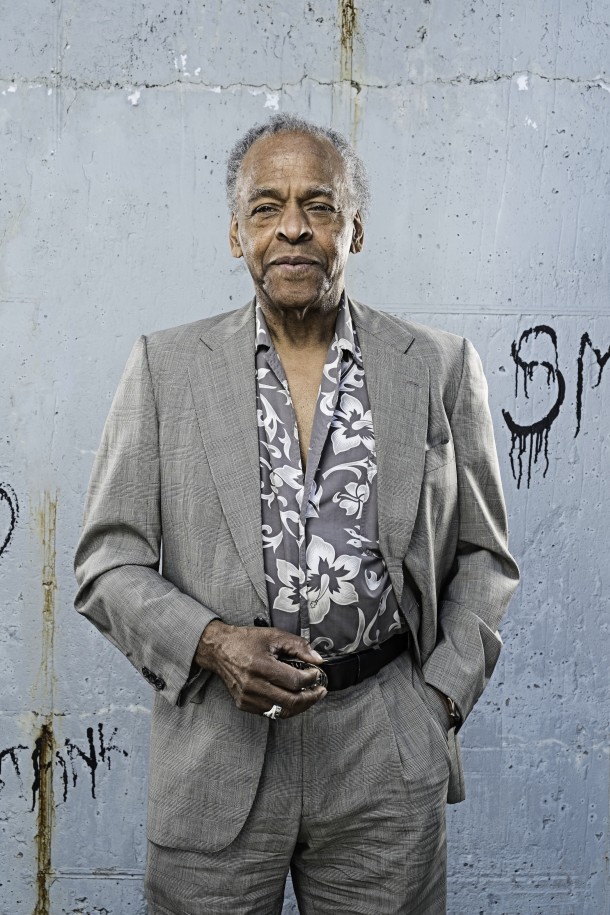

Cecil McBee

(b. May 19, 1935)

Artist Biography by Steve Huey

One of post-bop's most advanced and versatile bassists, Cecil McBee has played with an enormous variety of artists, and is just as capable in a solo or group improvisational context as he is at offering thoughtfully advanced background support. McBee was born May 19, 1935, in Tulsa, and played clarinet as a high schooler before switching to bass at age 17. He studied to be a music teacher and spent two years conducting a military band; he played with Dinah Washington in 1959, and, in 1962, he moved to Detroit to make inroads into the city's burgeoning jazz scene. He joined Paul Winter's folk-jazz ensemble in 1963, and moved to New York with them the following year. McBee found numerous opportunities there, recording and playing with artists like Andrew Hill, Sam Rivers, Jackie McLean, Wayne Shorter, and Keith Jarrett. He worked with Charles Lloyd during the saxophonist's breakthrough year of 1966, and later in the decade recorded with Pharoah Sanders, Yusef Lateef, Alice Coltrane, and Charles Tolliver. The '70s found McBee maintaining many of those connections, while also playing with Abdullah Ibrahim, Lonnie Liston Smith, Joanne Brackeen, Art Pepper, and Chico Freeman, plus leading his first session for Strata East in 1974 (titled Mutima). Two live dates from 1977 featuring Freeman, Music From the Source and Alternate Spaces, followed on small labels. McBee branched out into string-driven chamber jazz on his next effort, 1982's Flying Out. After 1983's Compassion, though, McBee remained largely silent as a leader for quite some time, returning to his familiar sideman role. In 1996, he formed his own quintet and began touring Europe; their music was documented on 1997's Unspoken.

Cecil McBee

Cecil McBee

World-acclaimed Bassist Cecil McBee was born and raised in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a community of rich and varied musical roots. His musical career started in high school, where he first played the clarinet. He and his sister Shirley soon gained local notoriety performing clarinet duets at concerts around the state. By the age of 17, he began to experiment with the string bass and played steadily at local nightclubs with top Jazz and Rhythm and Blues groups.

Because of the great promise he showed on the clarinet, Cecil was offered a full scholarship to attend Central State University in Wilberforce, Ohio and upon his arrival to college, he was immediately embraced as both a fine clarinetist and a promising young bassist. Cecil found the academic atmosphere extremely inspiring, both towards his educational needs as a potential instructor as well as bass performer. Unfortunately, his college education was interrupted by his induction into the U.S. Army where he spent two years as the conductor of the “158th Band” at Fort Knox, Kentucky. There he developed a personal study of the possibilities of bass composition and improvisation.

After his discharge from the army, Cecil returned to college to resume his studies and eventually received Bachelor of Science degree in music education. By the time he graduated from college, Cecil realized that although he had prepared for a career in education, he was more inspired by performing jazz on the world stage. To realize this goal, Cecil decided to move to Detroit, then home to one of the most thriving jazz communities in the world. Within a year, he joined Paul Winter Sextet, which turned out to be an open passage for his eventual arrival in New York City.

Since his arrival in New York, Cecil has been embraced for his talents and has recorded and traveled worldwide with such powerful Jazz personalities as Charles Lloyd, Pharoah Sanders, Elvin Jones, McCoy Tyner, Miles Davis, Bobby Hutcherson, Keith Jarrett, Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Sonny Rollins, Joe Henderson, Andrew Hill, Sam Rivers, Michael White, Jackie McLean, Yusef Lateef, Alice Coltrane, Ravi Coltrane, Abdullah Ibrahim, Lonnie Liston Smith, Buddy Tate, Joanne Brackeen, Dinah Washington, Benny Goodman, George Benson, Nancy Wilson, Betty Carter, Art Pepper, Charles Lloyd, Pharoah Sanders, Dave Liebman, Joe Lovano, Billy Hart, Eddie Henderson, Yosuke Yamashita, Billy Harper and Geri Allen.

The recipient of two NEA composition grants, McBee has written works that are performed worldwide and have been recorded by Elvin Jones, McCoy Tyner, Pharoah Sanders and many others. His music covers all territories of creative improvisation and is unique to his own individuality and incredible abilities on the instrument.

In 1989 he won a Grammy for his performance of “Blues for John Coltrane” featuring Roy Haynes, David Murray, McCoy Tyner and Pharoah Sanders. In 1991, he was inducted into the Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame.

As one of post bop’s most advanced and versatile bassists, Cecil McBee creates rich, singing phrases in a wide range of contemporary jazz contexts.Cecil McBee - Biography

"McBee, of course, is one of the greatest living bassists."

"He's one of the most highly regarded bassists of the post-bop generation."

"Few groups today sound as fresh, generate as high an emotional charge, or leave as lasting an impression as McBee's."

From the time he first arrived in New York City in 1964, Cecil McBee has remained one of the most in-demand bassists in jazz, appearing on hundreds of influential recordings as well as in clubs and concert halls throughout the world. During this same span of five decades, McBee has also become a celebrated composer and teacher, leading his own ensembles and earning a distinguished professorship at the New England Conservatory in Boston, where he has taught for over 25 years. This unparalleled experience is now captured in two remarkable publications: a revolutionary course of instruction to the art of the doublebass and a collection of McBee’s own remarkable compositions, many of which have already joined the canon of jazz standards.

Born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1935, McBee switched from clarinet to the upright bass at the age of 17 and quickly became a sought after voice on his instrument. Following his music studies at Ohio Central State University, the bassist spent two years in the army, conducting the band at Fort Knox. In 1959 he performed with Dinah Washington and moved to Detroit, where his engagement with Paul Winter’s ensemble in 1963–64 brought him eventually to his adopted home, New York City. Within two years McBee had recorded landmark sessions with such major figures as Wayne Shorter, Jackie McLean, Andrew Hill, and Sam Rivers, and held the bass chair in Charles Lloyd’s extraordinary quartet with Jack DeJohnette and Keith Jarrett.

Since that time he has recorded and toured with many of the greatest contemporary jazz artists, including Miles Davis, Yusef Lateef, Pharoah Sanders, Archie Shepp, Freddie Hubbard, Woody Shaw, Alice Coltrane, McCoy Tyner, Mal Waldron, Kenny Barron, Joanne Brackeen, Abdullah Ibrahim, Art Pepper, Anthony Braxton, Elvin Jones, Clifford Jordan, Chet Baker, and Johnny Griffin. McBee has also recorded seven albums as a leader of his own ensembles. In 1988 he received a Grammy Award for his performance on the tribute recording, Blues for Coltrane, a sextet that also featured Pharoah Sanders, David Murray, McCoy Tyner, and Roy Haynes.

Many of the touring groups and recordings on which McBee has appeared have also featured his exceptional compositions; Charles Lloyd’s breakthrough album, Forest Flower, released in 1966, includes McBee’s now standard ballad, “Song of Her.” Among his other most-recorded tunes are “Wilpan’s,” “Peacemaker,” “Slippin’n Slidin’,” “Blues on the Bottom,” “Consequence,” and another often-recorded ballad, “Close to You Alone.” With the drummer Billy Hart, McBee is the core of the rhythm section in two different longstanding groups of iconic artists, Saxophone Summit and The Cookers, each of which perform and record many of McBee’s more recent and classic compositions.

For nearly four decades, Cecil McBee has been teaching privately and at distinguished colleges and universities, including artist in residence at Harvard from 2010 to 2011. Throughout this time, he has been refining his teaching techniques and developing an instruction book for the doublebass that is revolutionary in its approach and widely applicable to improvisation for every instrumentalist.

Jazz on a High Floor in the Afternoon:

Cecil McBee

November 15–16, 2019

Floor 8

|

| CECIL MCBEE |

Curated by celebrated jazz pianist, composer, and visual artist Jason Moran and Whitney performance curator Adrienne Edwards, Jazz on a High Floor in the Afternoon is a series of live in-gallery performances presented over nine weekends. The series features cross-generational artists performing within Moran’s three mixed-media “set sculptures”—STAGED: Savoy Ballroom 1 (2015), STAGED: Three Deuces (2015), and STAGED: Slugs’ Saloon (2018). Each installation pays homage to an iconic New York jazz venue.

Born in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1935, Cecil McBee switched from clarinet to upright bass at the age of seventeen and quickly became a sought-after voice on his instrument. McBee moved to New York in the mid-1960s and within two years had recorded landmark sessions with Wayne Shorter, Jackie McLean, Andrew Hill, and Sam Rivers. He held the bass chair in Charles Lloyd’s extraordinary quartet with Jack DeJohnette and Keith Jarrett, and has recorded seven albums as bandleader. In 1988 he received a Grammy Award for his performance on the tribute recording Blues for Coltrane, a sextet that also featured Pharoah Sanders, David Murray, McCoy Tyner, and Roy Haynes. He has recorded with Miles Davis, Yusef Lateef, Archie Shepp, Alice Coltrane, and Joanne Brackeen, among others.

Friday, November 15

7 pm*

Saturday, November 16 (Sold out)

4 pm

Tickets are required ($25 adults; $18 members, students, seniors, and visitors with a disability) and include Museum admission.

*Tickets for performances during Pay-What-You-Wish hours (Fridays, 7–10 pm) will be distributed day-of, on a first come, first served basis at the Museum starting at 7 pm.

See all performances from the Jazz on A High Floor in the Afternoon series.

Bright Moments with Cecil McBee

The bassist tours his brilliant discography

For the past six decades, bassist, composer and educator Cecil McBee has quietly anchored the rhythm section for bands led by Charles Lloyd, Jackie McLean, Pharoah Sanders, Sonny Rollins, Saxophone Summit and countless others. He currently tours with the Cookers, a supergroup featuring saxophonists Billy Harper and Donald Harrison, trumpeters Eddie Henderson and David Weiss, pianist George Cables and drummer Billy Hart. Their most recent album, The Call of the Wild and Peaceful Heart (Smoke Sessions), features originals by McBee and the other band members, with arrangements that recall the postbop milieu in which they cut their teeth. Most of the 81-year-old bassist’s credits are with saxophonist-led bands, and perhaps that has something to do with his first instrument, the clarinet.

McBee got his professional start with Dinah Washington, while putting himself through college at Central State University in Wilberforce, Ohio, where he had a partial scholarship for clarinet. Later, as an Army bandsman stationed at Fort Knox, Ky., he met fellow clarinetist (and then-aspiring jazz pianist) Kirk Lightsey. After playing the day’s marches, “all I did was practice the bass for two years,” McBee recalled recently at his Bedford-Stuyvesant townhouse. “I found a place, believe it or not, in the latrine, where nobody could hear me.”

After the military, McBee and Lightsey moved to Detroit, where the late bassist Bob Cranshaw heard them in duo at the Hobby Bar one night. Cranshaw encouraged McBee to go to New York, and promised to find him a place there if he did. McBee recently sat down with JazzTimes to reflect on what happened next.

Grachan Moncur III

Some Other Stuff (Blue Note, 1965)

Moncur, trombone; Wayne Shorter, tenor saxophone; Herbie Hancock, piano; McBee, bass; Tony Williams, drums

I was living on Great Jones Street, between Lafayette and Broadway, in a loft that was owned by a pianist whose name was Nat Jones. One afternoon I was practicing, and I heard this knock on the door to the far right, where Nat lived. I kept practicing, and about 30 minutes later, I’m engrossed in what I was doing—the intent to include a third finger, pizzicato-wise, on my right hand—and suddenly somebody knocked on my door. It was Grachan!

“Pardon me, McBee,” he said. “I came to find you. I heard you were staying with Nat Jones.” He said, “My name is Grachan Moncur, and excuse me, I was standing outside listening to you for a minute, and I really like what you’re doing. Especially that fast stuff.” And he said, in so many words, “By the way, now that I’ve heard you, I’ve got a recording. Can you meet me for a rehearsal next Tuesday?”

When I arrived at the studio at about 1 o’clock that afternoon, it was Herbie, Wayne and Tony. I froze right away. I said, “I’m not ready to play with these guys!” So the hair rose on the back of my neck, and I didn’t have any. But they were very kind.

Grachan put some music on the stand, some chord changes that were all over the bar line, under the bar line, and I said, “What do I do?” He said, “Just play what I heard you play when you were practicing—that fast stuff. Just play it freely, openly.” That was wonderful until, on the second side, he had us rehearse the only tune that was in time [“Thandiwa”], which was in 6/4, in B-flat minor. I knew nothing about B-flat minor in terms of how to articulate that, so I played just tonics and fifths, all arpeggios. So back to the study after that.

Jackie McLean

Action (Blue Note, 1967)

McLean, alto saxophone; Charles Tolliver, trumpet; Bobby Hutcherson, vibraphone; McBee, bass; Billy Higgins, drums

I remember I was scared to death. I had just arrived in New York City. I’ve never really discussed [Jackie McLean’s] initial call to me for a gig at Slugs’. We had played a birthday celebration in the neighborhood, and one of the owners was there and invited us to play. Slugs’ was then just a neighborhood place to sit and have a drink. Immediately it was a hit, and the club was now announced as a place to hear music.

[McLean] called me in for the [It’s Time! recording] date, and then subsequently we played quite a few gigs locally, and even in Canada once. [It’s Time!] was my third album after having arrived in New York, after Some Other Stuff and then Cathexis with Denny Zeitlin. Grachan’s album as well as Denny Zeitlin’s were more over the edge, insofar as harmony and rhythm, which I felt very comfortable with, because I was just out of college and I was like a triple-A student in harmony and theory. But rhythmically I didn’t feel so comfortable with both [It’s Time! and Action].

Rhythmically, for a bass player, the most important pronouncement of what you do is to understand real clear what that single quarter note is. That one, two—it shouldn’t vary unless expected, and I didn’t know about the dynamic of that, so now that I’m in the studio with Jackie, that realization came to me. But with Bobby and Charles and all those guys, you couldn’t go wrong anyway, so there were some bright moments equal to the more shaky moments. I was just in New York for a minute, and Jackie was very kind.

Charles Lloyd

Forest Flower: Charles Lloyd at Monterey (Atlantic, 1967)

Lloyd, tenor saxophone, flute; Keith Jarrett, piano; McBee, bass; Jack DeJohnette, drums

When I was with Wayne Shorter at Slugs’, there was Roy Haynes on drums and a guy named Albert Dailey on piano. Wayne had just left Art Blakey and was en route to the next phase, and one night there was this tall guy to the right of the bandstand, at the edge of the bar. He was the only one standing up, shaking his head to the music, having a good time.

When we got off the stage, he approached me and said, “Man, I really loved the way you play.” It was Charles Lloyd! “By the way,” he said, “I have a date in Chicago next February. Would you be available?” I said, “Sure.”

So that’s where I met Jack DeJohnette and Gábor Szabó. In Chicago, we did a really wonderful week. Gábor was leaving for California, so Charles asked Jack if he knew anybody who could play piano with the group. Jack mentioned Keith Jarrett, and he said, “Yeah, I know this 19-year-old dude that plays at Berklee, and, actually, he’s a tyrant of sorts, man, because nobody can get along with him. The teachers can’t teach him anything. He’s always criticizing them. It’s relatively unsettling.” Charles said, “Let’s get him.” So the following March, we ended up hitting at the Jazz Workshop in Boston on Boylston Street, and right away it was like, with Keith, the sun shined even brighter.

Now, when I first heard Ray Brown, I was so humble I couldn’t practice for three months after that. Literally. But the night before the Monterey recording, we were at Shelly’s Manne-Hole, in L.A., with the Charles Lloyd Quartet. The very last night, as I’m reaching over to get my case to put it on the bass, somebody touches me on the back. I looked up—it was Ray Brown! I almost fainted. He said, “McBee, you sounded wonderful.” Then he said, “By the way, would you take me somewhere and show me how to play with that third finger?” And I gave him a lesson. That was my moment of passage. The Forest Flower album happened the very next day.

Yusef Lateef

The Blue Yusef Lateef (Atlantic, 1968)

Lateef, tenor saxophone, flutes, various world instruments,

vocals; Blue Mitchell, trumpet; Sonny Red, alto saxophone; Buddy Lucas,

harmonica; Kenny Burrell, guitar; Hugh Lawson, piano; McBee, bass; Bob

Cranshaw, electric bass; Roy Brooks, drums; the Sweet Inspirations,

vocal group; plus strings

This is one of my first uses of the synthesizer—my very first, and quite frankly, that was overdubbed after the fact. When I heard it, I thought it was just a passing thing. Kenny Burrell was out of Detroit also. They were all brothers and sisters really. It was like everybody was part of the same family, and now I’d become part of the family.

I had concluded the stint with the Charles Lloyd Quartet—this was in ’67—and I began with Yusef Lateef. That came about because of a lady in Detroit whose name was Alice McLeod, who was a celebrated pianist there amongst the many fine, great musicians that emanated from the Detroit area. She was highly respected, and lived in a sizable Victorian house. In those parts of the world, especially during that time, those sorts of edifices were easily come by if you had reasonable amounts of money. This was in 1962. So a sizable place where her living room was—you wouldn’t believe how large it was, centered by a grand piano—and this was the lady who was eventually going to become Alice Coltrane.

Every Sunday, when appropriate, she would have jam sessions there in that parlor—we called it “the parlor.” And whoever was in town—Elvin Jones, Joe Henderson, Yusef Lateef—they would come there and touch base and check everybody out, find out what’s going on and play something. I was always invited, which began my contact with those who were necessary for my survival socially and musically.

Pharoah Sanders

Thembi (Impulse!, 1971)

Sanders, saxophones, alto flute, various world instruments,

percussion; Michael White, violin, percussion; Lonnie Liston Smith,

keyboards, percussion; McBee, bass, percussion; Roy Haynes, Clifford

Jarvis, drums, percussion; James Jordan, ring cymbal; plus African

percussion

I’m worldwide respected because of [the solo bass track “Love”], so people say. Through that association with Alice Coltrane in Detroit, she called me to do a recording called Journey in Satchidananda, and she introduced me to Pharoah Sanders, who participated in that album. By that time I felt very comfortable, especially modally. During that experience, Pharoah Sanders said, “It was really nice to play with you,” and he went his own way. But then I called him. I said, “Pharoah, I want to play with your band. I must play with your band.” He said, “Come on. I thought about you, too.” So I ended up with him for a wonderful stint of about three years.

Now that we’re in the studio [for Thembi], we were about to play one of his tunes that we had rehearsed, and he said, “OK, take number one. Let’s go!” And then Pharoah said, “Wait a minute! McBee, why don’t you just play something out front? I’m thinking of an intro which I can’t find, so why don’t you just play something?” I had never experienced anything like that. So I simply closed my eyes and went back to my living room on 106th Street and practiced, and just played whatever I was trying to achieve for the future. I just went there, and it turns out, when it was released, lo and behold, after all the previous recordings and performances, the world said, “There’s a new bass player!”

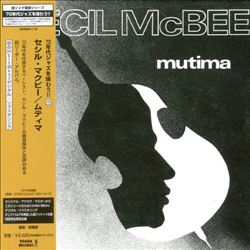

Cecil McBee

Mutima (Strata-East, 1974)

McBee, bass; Tex Allen, trumpet, flugelhorn; Art Webb,

flute; Allen Braufman, alto saxophone; George Adams, tenor and soprano

saxophones; Onaje Allan Gumbs, keyboards; Jimmy Hopps, drums; Jaboli

Billy Hart, cymbal, percussion; Lawrence Killian, congas; Michael

Carvin, gong, percussion; plus Dee Dee Bridgewater, guest vocalist;

Cecil McBee Jr., electric bass; Allen Nelson, drums

Mutima was really an album that was very much anticipated by myself, because now I had the opportunity to express, in broad terms, Cecil McBee the composer. Upon entering New York City, I felt very capable of writing music and arranging music, which I had qualitative experience with when I was in Detroit, and with Kirk and other groups.

To this day, there’s one tune on there that I feel is one of the best that I’ve ever come about, and that’s “Mutima” itself, which means “from the heart” [in Swahili]. And I’m looking forward to introducing it to the Cookers. Over the years, occasionally my compositions have been heard and most of the time appreciated. But as a composer, I’m seen as somebody who is more of a sideman.

And to this day, with “Mutima” being my favorite tune, Alternate Spaces is my favorite album. In America it’s not known, but it’s the best thing I’ve ever done. I’m a professor at the New England Conservatory, where “Mutima” and Alternate Spaces are among the favorites, so I understand. The young kids who are now emerging think it’s contemporary, that I wrote the music yesterday, when in fact it’s from the 1970s.

Freddie Hubbard & Woody Shaw

Double Take (Blue Note, 1985)

Hubbard, trumpet, flugelhorn; Shaw, trumpet; Kenny Garrett,

alto saxophone, flute; Mulgrew Miller, piano; McBee, bass; Carl Allen,

drums

That is one of the albums that I feel very fortunate to be a part of. Freddie Hubbard had announced that his favorite rhythm section at the time was Elvin Jones, McCoy Tyner and me. So I said a salute to my good friend Jimmy Garrison for that moment in the eyes of Freddie Hubbard. And I’d performed a lot with Woody Shaw, so when they decided to do the album, it was really one of my best moments, because they both chose me to play with Mulgrew and Carl Allen.

It’s a great album, one that I find no criticism of. I use it as an example for my trumpet students at the college in Boston—that level of competence and so forth, not only when playing the music, but the level of creativity and the very powerful urgency of expressing oneself collectively. And I can say no more.

Woody appeared conceptually to have something very similar to what I was working on with the bass, because now that I was more comfortable with utilizing and including my third finger, harmonically he was doing the same thing. We tried to infuse the mystery of the unexpected tone as points of departure and arrival to accent what’s happening before or after the fact. So I heard that in him, and with Freddie being so advanced everywhere, especially harmonically, it was just a dream.

The Leaders

Mudfoot (Black Hawk, 1986)

Lester Bowie, trumpet; Chico Freeman, tenor saxophone,

soprano saxophone, bass clarinet, vocals; Arthur Blythe, alto saxophone;

McBee, bass; Kirk Lightsey, piano; Famoudou Don Moye, drums

“Song of Her” was on the second side of Forest Flower. The Leaders was great. It was a group that was very alive, very energetic, and mirrored the thing with Charles Lloyd. We were very much like brothers, but with the Leaders, the expertise, composition-wise, and the ability to play those tunes were broadly diverse from person to person, which made the music even more interesting. We were together about 10 years, traveled all over Europe, and when you play with a group that long, you can close your eyes and play the music and everything’s all right.

McCoy Tyner

Blues for Coltrane: A Tribute to John Coltrane (Impulse!, 1987)

Tyner, piano; David Murray, Pharoah Sanders, tenor saxophones; McBee, bass; Roy Haynes, drums

When you put four people together who haven’t played together in some time—I had never played with David Murray before—and you are now in the studio with no rehearsal, expected to do something, you’re on your toes, right? Here I am again with Pharoah Sanders, and I was with Roy Haynes at Slugs’ for about three years, which was a great lesson from him. But speaking of McCoy, previously we had done an album called Quartets 4 X 4. Previous to that I had never played with McCoy, and I was a little nervous because of the greatness of this man.

So now that we’re in the studio and he has begun to play, I felt extremely comfortable! Why? Because everybody that I played with played just like him! Kirk Lightsey didn’t play like him; Keith didn’t play like him; but everybody else was right in that zone. Just as most people were in Ray Brown’s zone, or Paul Chambers’ zone, Scott LaFaro. So it was very easy. I was surprised that it got a Grammy, and I’m very proud of that.

Elvin Jones

It Don’t Mean a Thing… (Enja, 1994)

Jones, drums; Nicholas Payton, trumpet; Delfeayo Marsalis,

trombone; Sonny Fortune, tenor saxophone, flute; Willie Pickens, piano;

McBee, bass; Kevin Mahogany, guest vocalist

It was a grand experience with Elvin Jones. When I was up at 84th Street right off Riverside Drive, I met Jimmy Garrison. We hung out every now and then and I became not only familiar with him as a good friend, but had begun to acknowledge his great addition to Coltrane and also to the music at large. I began to focus on him, past Paul Chambers and Richard Davis, who were my heroes. Richard Davis was the contemporary guy, and Paul Chambers was the one from whence it all comes for me, still to this day, insofar as that pronouncement of tone.

I realized that Jimmy Garrison was very essential to the string bass in terms of what its responsibilities were beyond the other great guys, because the way he placed his tone on the floor on that beat was absolutely perfect for John Coltrane. There was no variance. He was right on it, which is what Elvin Jones needed. And I knew that, so when I played with Elvin Jones, he just loved the fact that I was respectful enough to just put that note right on the button and I would let him let the cat out of the bag. I played with him off and on for some time, and I ended up doing one record with him and John Hicks called Power Trio, which utilized one of my simple tunes called “‘D’ Bass-ic Blues.” He just loved it. After that, every time he saw me, he would want to embrace me. “McBee! Let’s play that blues!” And you don’t want Elvin Jones to embrace you, ’cause he’ll break your back.

The Cookers

The Call of the Wild and Peaceful Heart (Smoke Sessions, 2016)

Eddie Henderson, David Weiss, trumpets; Donald Harrison,

alto saxophone; Billy Harper, tenor saxophone; George Cables, piano;

McBee, bass; Billy Hart, drums

Truthfully speaking, it was one of the most difficult albums I’ve ever recorded, because that day I was chemically not connected with myself. I just didn’t feel that good that day—my energy level was lower than expected. And I’m in the studio about to play music that was very demanding, so, as I tell my students, it’s going to be what it is. Just concentrate on who you are at that particular time. Because if you studied and practiced and studied and practiced in search of excellence, only excellence, whatever you do is going to be excellent if you know nothing else. So, especially “The Call of the Wild and Peaceful Heart” was [a composition] that calls for intense concentration, because the notes on the instrument had to be from an upper area to the extreme lower area—back and forth.

George Cables’ “Blackfoot” is a wonderful tune that I love so much. Any time I even think about it I want to sing and dance. And my tune, which is called “Third Phase,” is one that I am proud of. It’s a composition that provides harmony that is related with unusual intervals between the chords, just all over the place, that works really well with a melody that is accented at irregular spots within the measure. It’s called “Third Phase” because when I completed the Army and went back to school and got my degree, it took me nine years to do that. In New York, I entered a situation where for a long time I stopped playing music except for a few clubs and little gigs. I had entertained driving a taxi and washing dishes, but something happened to me for nine years where I was off the stage.

So I was sitting at the piano at the school one day when a student didn’t show up, and I started playing as I usually do, and these things that I just explained came to me, and the more I played the more excited I got about the possibility of a new tune. And when I finished and it was comfortable, I said, “Oh, the third phase,” because I’m happy now. I’m now in front of all of that.

Originally Published

Jazz Unlimited for February 11, 2017 will be “The Career of Cecil McBee.” Bassist extraordinaire Cecil McBee has been a force in jazz for 58 years. He has contributed heavily to the music of Andrew Hill, Sam Rivers, Jackie McLean, Wayne Shorter, Charles Lloyd, Woody Shaw Alice Coltrane, Vanessa Rubin, McCoy Tyner, Yusef Lateef, George Adams, Saxophone Summit, The Leaders, Charles Tolliver, Grachan Moncur III, Chico Freeman and The Leaders Trio. He is currently a member of The Cookers and teaches at the New England Conservatory.

The Slide Show has my photographs of some of the artists heard on this show.

The Archive of this show will be available until the morning of February 19, 2018.

Here is Saxophone Summit playing John Coltrane's "Expression" with Joe Lovano, Dave Liebman & Ravi Coltrane (ts) Randy Brecker (tp) Phol Markowitz (p) Cecil McBee (b) and Billy Hart (d). The date was not given.

Bassist Cecil McBee is currently touring with The Cookers, an All Stars band featuring Billy Harper, Eddie Henderson, George Cables, Billy Hart, Donald Harrison and paying tribute to Freddie Hubbard’s eponymous Blue Note LP. But he has been putting his own footprints on Jazz history for a long time: as a composer first and also as a musician. And if he’s only recorded a handful of LPs under his own name, these LPs for such respected labels as Strata East as well or India Navigation have become real classics for spiritual jazz lovers.. We are very proud to publish this (too brief) interview with one of our heroes.

You’re touring with The Cookers, the type of group you often

participated in (The Leaders for example …). What pleasure do you find

in this kind of summit meeting?

That I’m participating in creating some of the world’s most powerful music. Unlike what I generally am exposed to these days.

Between you all how many years of experience, albums recorded?

The Cookers have over 300 years of experience combined and have performed on over 1,000 albums combined.

Your are 80 years… Do you remember your professional debut? What brought you into music?

When I was 17, I performed with a blues singer named Jimmy “Cry

Cry” Hawkins in my hometown of Tusla, Oklahoma. The blues got me off to

a good start. I started on the clarinet when I was in middle school and

showed a certain proficiency on the instrument. I began playing bass as

well when I was 17 years old. Because of my skills on the clarinet, I

went to college at Central State University in Ohio as a music major.

While there, I got exposed to a lot of Jazz for the first time.

Later, you played on stage in Detroit. What was so special about that scene in the 1960s?

I was invited to move to Detroit by Kirk Lightsey who I had met

while in the Army. We both performed together in the Army band on

clarinet. After we were honorably discharged from the Army, we moved to

Detroit and I met all the great Detroit musicians who would inspire to

get to the next level over the next few years.

New York was something else, right? Do you think you experienced something unique in the 1970s?

New York was wonderful and from the moment I arrived, it was an

extremely unique experience for me. However, I must add that from the

very moment I arrived in New York I found myself performing at the

highest level with some of the world’s greatest musicians such as Herbie

Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Jackie McLean and Charles Lloyd etc etc.

Mutima from “Mutima” (Strata East)

Audio Player

You even have actively participated in the experience of an

independent label : Strata East. What was the philosophy behind it? Is

it something still possible nowadays?

The philosophy was simply that on all accounts we would take

ownership entirely of our music and at the highest level of business.

This sort of thing is still possible today with a bit of hard work and

insight and the willingness of musicians to work together for a greater

good.

You were part of the Strata-East tour last year with Charles

Tolliver and Stanley Cowell (with great gigs in Paris and London). Is it

gonna be a following on this? More dates, a new album…?

It was nice to see the guys again. We plan to do a few more dates in the near future.

Jackie McLean and Yusef Lateef, Pharoah Sanders and Sam

Rivers, Anthony Braxton and Horace Tapscott … Among all these stars you

played with, who impressed you the most?

They all impressed greatly and in different ways. They were all of great importance to me.

What are the essential qualities of the so-called sideman? The listening? The sense of collective? The will to serve?

I don’t consider myself a sideman but an equal partner in the

creation of this music. I have also know that I have a lot to contribute

to this music as a bandleader and composer and being labeled as a

sideman keeps me from getting the proper exposure I believe my music

deserves.

The Cookers…

‘Consequence’ from “Alternate Spaces” (India Navigation)

Audio Player

Your album “Alternate Spaces” on India Navigation is one of our favorite! Can you give us details about the recording session?

“Alternate Spaces” to this day has been one of the albums I’m

most proud of. The complex nature of the compositions introduced quite

realistically a more in depth natural quality of who I am as a composer.

It was India Navigation label that respectfully provided an open door

for me to showcase where I was as a composer at the time. I felt

entirely individual in my effort to be my own voice for the first time.

Will we be lucky enough to have another opportunity to listen a new album under your name after all these years?

I have completed many original compositions that I feel would

make a great CD. However it takes a lot of time to properly prepare to

record my music and I also need the right collaborators to fully realize

this project. The goal is to record again in the future and I hope to

realize this soon.

Thanks to David Weiss, Tom Woods and all New Morning’s crew!

Cecil McBee

World-acclaimed Bassist Cecil McBee was born and raised in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a community of rich and varied musical roots. His musical career started in high school, where he first played the clarinet. He and his sister Shirley soon gained local notoriety performing clarinet duets at concerts around the state. By the age of 17, he began to experiment with the string bass and played steadily at local nightclubs with top Jazz and Rhythm and Blues groups.

Because of the great promise he showed on the clarinet, Cecil was offered a full scholarship to attend Central State University in Wilberforce, Ohio and upon his arrival to college, he was immediately embraced as both a fine clarinetist and a promising young bassist. Cecil found the academic atmosphere extremely inspiring, both towards his educational needs as a potential instructor as well as bass performer. Unfortunately, his college education was interrupted by his induction into the U.S. Army where he spent two years as the conductor of the “158th Band” at Fort Knox, Kentucky. There he developed a personal study of the possibilities of bass composition and improvisation.

After his discharge from the army, Cecil returned to college to resume his studies and eventually received Bachelor of Science degree in music education. By the time he graduated from college, Cecil realized that although he had prepared for a career in education, he was more inspired by performing jazz on the world stage. To realize this goal, Cecil decided to move to Detroit, then home to one of the most thriving jazz communities in the world. Within a year, he joined Paul Winter Sextet, which turned out to be an open passage for his eventual arrival in New York City.

Since his arrival in New York, Cecil has been embraced for his talents and has recorded and traveled worldwide with such powerful Jazz personalities as Charles Lloyd, Pharoah Sanders, Elvin Jones, McCoy Tyner, Miles Davis, Bobby Hutcherson, Keith Jarrett, Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Sonny Rollins, Joe Henderson, Andrew Hill, Sam Rivers, Michael White, Jackie McLean, Yusef Lateef, Alice Coltrane, Ravi Coltrane, Abdullah Ibrahim, Lonnie Liston Smith, Buddy Tate, Joanne Brackeen, Dinah Washington, Benny Goodman, George Benson, Nancy Wilson, Betty Carter, Art Pepper, Charles Lloyd, Pharoah Sanders, Dave Liebman, Joe Lovano, Billy Hart, Eddie Henderson, Yosuke Yamashita, Billy Harper and Geri Allen.

The recipient of two NEA composition grants, McBee has written works that are performed worldwide and have been recorded by Elvin Jones, McCoy Tyner, Pharoah Sanders and many others. His music covers all territories of creative improvisation and is unique to his own individuality and incredible abilities on the instrument.

In 1989 he won a Grammy for his performance of “Blues for John Coltrane” featuring Roy Haynes, David Murray, McCoy Tyner and Pharoah Sanders. In 1991, he was inducted into the Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame.

As one of post bop’s most advanced and versatile bassists, Cecil McBee creates rich, singing phrases in a wide range of contemporary jazz contexts.

Website: http://www.cecilmcbeejazz.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cecil_McBee

Cecil McBee

Cecil McBee (born May 19, 1935) is an American jazz bassist. He has recorded as a leader only a handful of times since the 1970s, but has contributed as a sideman to a number of jazz albums.

Biography

Early life and career

McBee was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, on May 19, 1935. He studied clarinet at school, but switched to bass at the age of 17, and began playing in local nightclubs. After gaining a music degree from Ohio Central State University, he spent two years in the army, during which time he conducted the band at Fort Knox. In 1959 he played with Dinah Washington, and in 1962 he moved to Detroit, where he worked with Paul Winter's folk-rock ensemble in 1963–64.

New York

His jazz career began to take off in the mid-1960s, after he moved to New York, when he began playing and recording with a number of significant musicians including Miles Davis, Andrew Hill, Sam Rivers, Jackie McLean (1964), Wayne Shorter (1965–66), Charles Lloyd (1966), Yusef Lateef (1967–69), Keith Jarrett, Freddie Hubbard and Woody Shaw (1986), and Alice Coltrane (1969–72).

Later career

In the 2000s, McBee unsuccessfully sued a Japanese company that opened a chain of stores under his name.[1]

He was an artist in residence at Harvard from 2010 to 2011.[2] He teaches at the New England Conservatory in Boston, Massachusetts.

Awards

- 1991 he was inducted into the Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame.

Grammys

- Blues for Coltrane: A Tribute to John Coltrane (MCA, 1987), Pharoah Sanders/David Murray/McCoy Tyner/Cecil McBee/Roy Haynes – Winner, Best instrumental performance, individual or group, Grammy Awards, 1988.

Discography

As leader

- 1975: Mutima (Strata-East)

- 1977: Music from the Source (Enja)

- 1977: Compassion (Enja)

- 1979: Alternate Spaces (India Navigation)

- 1982: Flying Out (India Navigation)

- 1986: Roots of Blue (RPR) – duets with Muhal Richard Abrams

- 1997: Unspoken (Palmetto)

As sideman

With George Adams

- America (Blue Note, 1990)

With Ray Anderson

- Old Bottles - New Wine (Enja, 1985)

With Chet Baker

- Blues for a Reason (Criss Cross Jazz, 1985)

With Bill Barron

- Live at Cobi's 2 (SteepleChase, 1885 [2006])

With Kenny Barron

- Landscape (Baystate, 1984)

- What If? (Enja, 1986)

- Live at Fat Tuesdays (Enja, 1988)

With the Bob Thiele Collective

- Sunrise Sunset (Red Baron, 1990)

With Joanne Brackeen

- Snooze (Choice, 1975)

- Tring-a-Ling (Choice, 1977)

- Havin' Fun (Concord Jazz, 1985)

- Fi-Fi Goes to Heaven (Concord Jazz, 1986)

- Turnaround (Evidence, 1992)

With Dollar Brand

- African Space Program (Enja, 1973)

With Anthony Braxton

- Eight (+3) Tristano Compositions, 1989: For Warne Marsh (hatArt, 1989)

With Roy Brooks

- The Free Slave (Muse, 1970 [1972])

With Joe Chambers

- The Almoravid (Muse, 1974)

With Alice Coltrane

- Journey in Satchidananda (Impulse!, 1970)

With Junior Cook

- Pressure Cooker (Catalyst, 1977)

With Stanley Cowell

- Equipoise (Galaxy, 1979)

- Close to You Alone (DIW, 1990)

With Ted Curson

- Blue Piccolo (Whynot, 1976)

With Ricky Ford

- Looking Ahead (Muse. 1986)

With Chico Freeman

- Morning Prayer (India Navigation, 1976)

- Chico (India Navigation, 1977)

- The Outside Within (India Navigation, 1978)

- Kings of Mali (India Navigation, 1978)

- Spirit Sensitive (India Navigation, 1979)

- Destiny's Dance (Contemporary, 1981)

With Hal Galper

- Now Hear This (Enja, 1977)

With Johnny Griffin

- Birds and Ballads (1978)

With Louis Hayes

- Variety Is the Spice (Gryphon, 1978)

With Roy Haynes

- Thank You Thank You (Galaxy, 1977)

- Vistalite (Galaxy, 1977 [1979])

With Andrew Hill

- Compulsion! (Blue Note, 1965)

With Freddie Hubbard and Woody Shaw

- Double Take (Blue Note, 1986)

With Elvin Jones

- Power Trio (Novus, 1990) – with John Hicks

- When I Was at Aso-Mountain (Enja, 1990)

- Elvin Jones Jazz Machine (Trio, 1997)

- It Don't Mean a Thing (Enja, 1993)

With Clifford Jordan

- Two Tenor Winner (Criss Cross, 1984)

With John Klemmer

- Magic and Movement (Impulse!, 1974)

With Prince Lasha

- Inside Story (Enja, 1965 [1981])

With Yusef Lateef

- The Complete Yusef Lateef (Atlantic, 1967)

- The Blue Yusef Lateef (Atlantic, 1968)

- Yusef Lateef's Detroit (Atlantic, 1969)

- The Diverse Yusef Lateef (Atlantic, 1970)

With The Leaders

- Mudfoot (Black Hawk, 1986)

- Out Here Like This (Black Saint, 1987)

- Heaven Dance (Sunnyside, 1988) – The Leaders Trio with pianist Kirk Lightsey and drummer Don Moye

- Unforeseen Blessings (Black Saint, 1988)

- Spirits Alike (Double Moon, 2007)

With Dave Liebman

- The Seasons (Soul Note, 1992)

- John Coltrane's Meditations (Arkadia Jazz, 1998)

With Charles Lloyd

- Dream Weaver (1966, Atlantic)

- Forest Flower (1966, Atlantic)

- The Flowering (1966, Atlantic)

- Charles Lloyd in Europe (1966, Atlantic)

With Raphe Malik

- Storyline (Boxholder, 1999) – with Cody Moffett

With Joe Maneri

- Dahabenzapple (hat ART, 1993 [1996])

With Jackie McLean

- It's Time! (Blue Note, 1964)

- Action Action Action (Blue Note, 1964)

With Lloyd McNeill

- Treasures (1976)

With Charles McPherson

- New Horizons (Xanadu, 1977)

With Grachan Moncur III

- Some Other Stuff (Blue Note, 1964)

With Tisziji Munoz

- Visiting This Planet (Anami Music, 1980's)

- Presence of Joy (Anami Music, 1999)

- Divine Radiance (Anami Music, 2003)

With Amina Claudine Myers

- Salutes Bessie Smith (Leo, 1980)

With Almanac

- Almanac (Improvising Artists, 1977)

With Art Pepper

- Winter Moon (Galaxy, 1980)

With Dannie Richmond

- "In" Jazz for the Culture Set (Impulse!, 1965)

With Sam Rivers

- Dimensions & Extensions (Blue Note, 1967)

- Streams (Impulse!, 1973)

- Hues (Impulse!, 1973)

With Charlie Rouse

- Social Call (Uptown, 1984) with Red Rodney

With Buddy Tate and Dollar Brand

- Buddy Tate Meets Dollar Brand (Chiaroscuro, 1977)

With Pharoah Sanders

- Izipho Zam (My Gifts) (Strata-East, 1969 [1973])

- Jewels of Thought (Impulse!, 1969)

- Thembi (Impulse!, 1970)

- Black Unity (Impulse!, 1971)

- Live at the East (Impulse!, 1972)

- Village of the Pharoahs (Impulse!, 1973)

- Love in Us All (Impulse!, 1973)

With Saxophone Summit

- Gathering of Spirits (Telarch, 2004)

With Zbigniew Seifert

- Man of the Light (MPS Records, 1977)

With Woody Shaw

- The Moontrane (Muse, 1974)

- Love Dance (Muse, 1975)

- The Iron Men with Anthony Braxton (Muse, 1977 [1980])

With Archie Shepp

With Wayne Shorter

- Et Cetera (Blue Note, 1965)

- Odyssey of Iska (Blue Note, 1970)

With Sonny Simmons

- Burning Spirits (Contemporary, 1971)

With Lonnie Liston Smith

- Astral Traveling (Flying Dutchman, 1973)

- Expansions (Flying Dutchman, 1975)

- Rejuvenation (Doctor Jazz, 1985)

- Make Someone Happy (Doctor Jazz, 1986)

With Buddy Tate and Dollar Brand

- Buddy Tate Meets Dollar Brand (Chiaroscuro, 1977)

With Leon Thomas

- Spirits Known and Unknown (1969)

With Horace Tapscott

- The Dark Tree, Vol. 1 & 2 (hatOLOGY, 1989)

With Leon Thomas

- Spirits Known and Unknown (Flying Dutchman, 1969)

With Charles Tolliver

- Live at Slugs', Volume I & II (Strata-East, 1970)

- Music Inc. (Strata-East, 1971)

- Impact (Strata-East, 1975)

With Mickey Tucker

- Sojourn (Xanadu, 1977)

- Mister Mysterious (Muse, 1978)

With McCoy Tyner

- Quartets 4 X 4 (Milestone, 1980)

- Blues for Coltrane (1987)

With James "Blood" Ulmer

- Revealing (1977)

With Mal Waldron

- What It Is (Enja, 1981)

With Michael White

- The Land of Spirit and Light (Impulse!, 1973)

With Paul Winter

- Jazz Meets the Folk-Song (1963)

With Yōsuke Yamashita

- Sakura (Verve, 1990)

- Kurdish Dance (Verve, 1993)

- Dazzling Days (Verve, 1993)

- Fragments 1999 (Verve, 1999)

- Spider (Verve, 1996)

- Delightful Contrast (Universal, 2011)

With Denny Zeitlin

- Cathexis (Columbia, 1963)

References

External links

Cecil McBee: Masterful, And Always Equipped

A natural, he was quick to connect with musicians in his hometown of Tulsa, Oklahoma. But helping him along the road to becoming a top-flight musician was a series of encounters where people would come asking for him. They were people he didn't know, but who would boost him to the next step, the next chapter.

In each of these episodes, there was a degree of good fortune. But it was more than that. Each time someone came looking for the young Okie who could play the bass, McBee was equipped. He wasn't an advanced player when regional blues favorite Jimmy "Cry Cry" Hawkins came calling on the high school lad. But he was equipped enough to make the gig. He didn't have much experience when the strong tenor saxman Red Prysock asked for him. But he was equipped enough. He wasn't fully formed as a player when his high school music teacher told him, "Boy, get your ass to school," meaning off to college. But he was equipped.

The circumstances McBee encountered kept him on the road to a place not many people reach. He is a bassist of distinct flair, respected by others, and a fertile composer of jazz music with feeling and sophistication. He's played over the years with Elvin Jones, McCoy Tyner, Miles Davis, Keith Jarrett, Wayne Shorter, Charles Lloyd, Lester Bowie, Arthur Blythe, Jack DeJohnette, Joe Lovano, Ravi Coltrane and many more. These days, he is part of the superb, hard-driving septet, the Cookers, that has been making waves in the jazz world for few years now, gaining many fans along the way.

"It's been a great life for me," says McBee relaxing on an autumn afternoon. "Quite frankly, and I say this convincingly: I am just beginning. I am just beginning my career. That's the way I feel in terms of what I'm doing on the stage, the way I'm writing and teaching and existing in this world of music, at this level and at this point in my life. I am just beginning."

One of the things that has given McBee a jolt in recent years is the Cookers, a collection of excellent musicians, many of whom he has known and played with going back decades. It features the "younger" set of trumpeter David Weiss and saxophonist Donald Harrison, and the older veterans who have been friends, musically and otherwise, for longer: saxophonist Billy Harper, trumpeter Eddie Henderson, pianist George Cables and drummer Billy Hart. Their CD Time and Time Again (Motema Records) is one of the year's best.

"It's going great. Realistically, the popularity of the group, as I was discussing with my wife this morning at breakfast, is moving on up," he says."Wherever we are performing, people are coming out by the numbers and have proven to be very excited about what we're doing. As a person that's been around for awhile, it's truly rewarding for me to be around something like that."

The recording, "brings a lot of joy to me personally," he says, "because a lot of my music hasn't been heard over time as well as it should be." He has two compositions on the record, "Slippin' and Slidin'" and "Dance of the Invisible Nymph." McBee began writing music with frequency in the 1970s and it's something he takes pride in. "At that particular time, my music was considered a little too far out or unattainable conceptually, for what was going on at the time. That has been eventually erased and cast out. It seems that my creativity is now being heard and appreciated loud and clear."

He explains "Dance of the Invisible Nymph" is something he began working on in Germany for the Cookers. "I sat at the piano and came up with a tune with a bass line that was in 5/4. To answer that statement, the only response was a bar of 6/4. So rather than challenge the guys to play [counts aloud the two time signatures], I just put the bars together and I ended up with an 11/4 measure. I was forced to write a melody on top of that. It took me three and a half months. It turns out it really swings. To the extent it makes you want to move your body and dance a little bit, which is why I included the word 'dance.' [in the title] I thought I'd get your attention with 'of the invisible nymph.' [chuckles] But it has a nice feeling to it ... 'Slippin' and Slidin'' is a blues that's a little bit varied. Those tunes have been highly regarded, in performance. So I'm really happy about what I'm doing compositionally."

The bands soloing is always crisp and fiery, but they retain a group sound. Part of that is because they have all been around the block a few times, and have prior musical association in most cases.

"Being that we're rather mature musically, and personally, it gives us reason to accept all the varietal dimensions of the music that transpires. The variety of music that we have easily, measurably provides quality listening because of the flexibility of each individual mind toward things we feel are rather novel. So the combination of the past, the moment, and even bits of the future, are something people are picking up on and we're all excited about that."

Says drummer Hart, "We have similar experiences. Not only musical. We see the world similarly. When things are stressful, like when George Cables had to have his liver and kidney operation and we thought we were going to lose him, we would pull together. It's more of a family ... I moved to New York in 1968. How many years is that? That's when I first met George and Billy Harper. And I knew Eddie Henderson before that. Cecil McBee, I met in '64 or '65. So when it's a distressful situation, we can all share that. But most times, it's a joyful situation. It's really funny. It makes me wonder what we would have been like if we were members of a corporation." [chuckles]

McBee, always the composer, says he's working on a Cecil McBee Songbook that will include tunes he's written over the years and new ones. He'd like to see many of them recorded as well. "This was inspired by an ex-student of mine. There are 25 or 30 tunes that I've written from the 70s until now that have never been heard. I'm excited to get those compositions heard and eventually to find myself in the studio, surrounded by my music, with Cecil McBee on the bass. Hopefully, that's what's coming."

"I'm excited to immerse myself in the center of my compositions, my music, which hasn't been done in a great long time, and express myself that way. I think people will hear who I really am, which I think has gotten past the wanting years. It appears the people in position at recording companies have not realized what I can do on paper and even what I can do on the bass. Which is why I've never been able to get recording dates or many gigs to state, on stage, in the presence of audiences, that I'm a composer and bassist."

Another steady gig for McBee is being part of the Saxophone Summit group with Lovano, Coltrane and Dave Liebman. It includes Hart on drums and Phil Markowitz on piano. He also performs with pianist Yosuke Yamashita out of Tokyo. "He calls it the New York Trio. Pheeroan AkLaff [drums] and I have been traveling to Japan for 25 years, consecutively for the most part, each fall to do tours."

Strangely enough, McBee's first instrument was clarinet, which he started playing in his middle school years in Tulsa. "Almost immediately, I was selected as the best clarinetist. I placed myself in this bubble of joy, that I was so popular; I could play better than others." He was to replace a graduating senior. He had an awakening when he was asked to play a piece of classical music, but couldn't cut all the passages. "Why? Because all the time, from middle school to then, I was not reading. I was playing by ear. When the music showed up on the paper, I had to respect its worth. I couldn't play, so that very day my teacher put me into private lessons."

McBee continued to play clarinet in high school and would eventually go to college on a clarinet scholarship. But toward the end of his junior year, after band practice, he was putting his instrument away in a storage closet. As fortune would have it, there was something obstructing his way. Maybe it was patiently waiting for discovery.

"I looked down and there was a bass. An old metal bass. Dust was all over it. The first thing that hit me was I'd been reaching over that bass for almost two years, not even noticing. So I picked it up. I pulled one of the strings. And that was it. I tried to play some boogie woogie on it. Then I brought it to some of the jam sessions. The word got out after a month or so that there was a new bassist in town," he says, chuckling at he recollection. There weren't many bass players around and McBee was enjoying it, jamming around Tulsa.

One particular evening during a jam session, there was a knock at the door. The man who entered was a site to see. "He had long, shiny shoes. Big bell-type pants and a plaid coat. He had a gold tooth and his hair all slicked back. A big smile. A very dark-skinned fella. And he asked for Cecil McBee. And my buddy said, 'Wow, man. Do you know who that is? That's Jimmy 'Cry Cry' Hawkins Turns out Jimmy was a great, popular blues singer in the community. He was looking for a bassist. I ended up going with him and that was my intro into the world of music. I played the saxophone for the first couple of gigs. The third gig was at a high school for a junior-senior prom. They had a bass in the music room. I went down and got the bass and played the gig and I have not looked back. I was 17."

It was quite an experience for the young McBee. "Jimmy 'Cry Cry' was one who would eventually, when singing the blues, stand on his head and cry. He would support himself with one hand, with his feet in the air, and the microphone in his left hand, singing the blues, crying for his lady to come back. It was rather humorous, but effective for the audience."

After some time, the blues bassist was rehearsing for Hawkins' at the Flamingo Club in downtown Tulsa. Again, a figure walked in, seeking a bassist. The young bassist's friends were amazed, but McBee didn't know who it was. In strode Prysock. "He was a very famous saxophonist that had come to Tulsa to play a gig at a place called Clarence Love's Lounge, which was the jazz club there. He asked for Cecil McBee. It blew me away. I raised my hand. I had a bass there with me. He looked at me in a very curious manner with a rather disturbed face. He said, 'How long have you been playing?' I thought I'd impress him, I said 'three months.' He said, 'Can you play it?' I said, 'Yeah, I think so.' He said, 'Meet me tomorrow at Clarence Love's Lounge.' His bassist hadn't showed up from New York and he needed something. So I went over."

He spent a week with the band. "They played a lot of blues, which I had been accustomed to play with Jimmy. So I just had to fashion my notes for different purposes." After that, an all-female orchestra from Harlem led by Anna Mae Winburn, who went on to fame with her International Sweethearts of Rhythm, took McBee on a tour of Texas. He returned home to finish high school. "My senior year of high school was on-hand learning. When I got to college, I knew most of my changes and most of my tunes."

But at that point, going to college was not exactly on McBee's docket. An unexpected hero stepped up.

"I hadn't planned to go to college after playing music like that... Upon graduating from high school, I thought I would just hang and play music and explore the world. But my band director came by one evening. I'm the product of a single parent with six children. He literally, without invitation, came to my home. He told my mother he was going to send me to college. If she didn't like it, too bad. He pulled me out and said, 'Boy, get your ass in school. Take this ticket and get on the Santa Fe Railroad.' That was a Friday. I had to get on the train that Monday. This is the guy directing the band when I was making mistakes on clarinet. He told me, in a very forceful way, 'Get your ass in school. You be on the train at 9 o'clock Monday morning.' There was a train station not too far from me where you caught the Santa Fe Railroad that would take you to the world. I wrapped my bass in a cardboard box with rope. I had a bag of clothes and I went to college. I never looked back."

"Mr. Fields, the band director, put me on that train. My greatest hero. I thought he was going to punch me. [chuckles] 'Get your ass in school.' He knew I didn't have a father." McBee was off to Central State College in southwest Ohio and began to see the world outside Tulsa. And listen to the music of the world.

"When I arrived in college, it was absolutely wonderful. There were distinguished people there of thought, of learning. Something that I knew nothing about. The sun shone brightly in my life. Still today, I'm inspired." He was in college on a clarinet scholarship, but took the bass with him and played it in college.

McBee began to encounter serious jazz. In Oklahoma, it was mostly rhythm and blues, "and a few jazz things here and there of which I knew nothing about except playing by ear. When I got to college, there was Bird. There was Miles. My very first jazz experience that inspired me greatly was Chet Baker, the song "Isn't It Romantic." Chet Baker is out of Oklahoma City. Oscar Pettiford is out of Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, just south of Tulsa. I can go on and name Don Cherry, Charlie Christian, members of Count Basie's band [all from Oklahoma]. Tulsa, Oklahoma, represented at that time a central energy that provided great musicians to the world. I ended up picking up the bass in that environment. That's how I learned."

McBee was accepted by the older students. "These were the guys that turned me on to Miles and Charlie Parker and Shorty Rogers. All the great masters of the music. It was amazing. Music turned out to be natural to me. To hear music at that level and to have the opportunity to one day perform that way was just so exciting. Being in college was the best thing to happen to me. I never went back to Oklahoma. I never chose to return."

But not everything went smoothly. There was romance for the usually shy Tulsa kid and it affected his studies. He ended up losing his scholarship but, determined, continued working various jobs so he could continue his music education. The sporadic nature of work and other circumstances made it a drawn-out process. It took McBee seven years to finish his degree. At the end of his junior year, with jobs scarce, he found himself in Dayton, Ohio, about 30 minutes away from school. Without a college deferment, McBee was drafted. This proved fortuitous, however. He calls it "the best thing that could have happened to me because now I had a roof over my head, I had three meals a day and man, I could practice my bass."

McBee became part of the 158th Army Band at Fort Knox, Kentucky, playing clarinet again. There he met Gus Nemith, a bassist who had studied classical technique and played with two fingers. "He was so articulate. He impressed me with his ability to get around the bass with two fingers. At that point I had no formal study on the instrument and was playing with a single finger. He showed me how to play with two fingers, which is the technique I teach young players today. It opened the horizon to me toward the future."

McBee practiced the bass at every opportunity, six or seven hours a night sometimes, until the end of his military responsibility. "In the interim, I met Kirk Lightsey, who was a clarinetist. He was a pianist who was getting through the military by playing the clarinet. We became the closest of friends. When I finished the service, I went back to school because now I had enough money to finish college. I got a degree in music education. I looked up Kirk in Detroit."

He stayed at the Detroit home of Lightsey, an outstanding jazz pianist, being treated "like a second son" by Mrs. Lightsey until he got his own apartment. The two began playing around the city, particularly the Hobby Bar. "We had become the top group in the city that attracted music lovers all over," says McBee. "We played there a whole year. Bob Cranshaw, who was in town with Sonny Rollins, heard about us and came in. He advised me if I would ever come to New York, he'd have a place for me to stay, because he thought I should come to New York. He liked the way I played. One night Tony Williams came in. Another night Aretha Franklin came in. I ended up meeting Freddie Waits, a fantastic drummer, who would play with Kirk and I every once in a while. We played other gigs elsewhere throughout Detroit. Here were three men who were honing their wares out of the joy of finding success in expressing something and giving people enjoyment. I never thought of going to New York."

McBee was content, having gotten through the rigors of working different jobs and worrying about money, while getting his education. Now he was making good music; he was part of a strong scene. But one day, Waits came to him with the news that Paul Winter was looking for a bassist. "I didn't know who the hell Paul Winter was," recounts McBee. "I met Paul, he heard me play. After having been in Detroit for almost one year, I went on the road with Paul and moved to New York. I called Bob Cranshaw and he arranged for an apartment for me to stay. There was a loft there—that's how I moved to New York."

"It was wonderful," he says. "By contrast to Tulsa and even Detroit, it was a place where I could find the entirety of myself, so long as I chose to do that by working hard and being smart about it and respectful. I just went out and heard all the great bass players—Richard Davis was my main idol at the time—and other players. I would listen to them and go home and practice and practice."

Winter told McBee that pianist Denny Zeitlin was making a record that would include drummer Waits. It was good that he was now a fluent reader of music. "Denny Zeitlin had some very complex music. That album was called Cathexis (Columbia, 1964). It was on Columbia Records, on which John Hammond was the producer. I thought we fared rather well. I had never heard music of that conceptual level that had directly not much to do with triads and scales and things like that. The sounds were rather obscure to me, but going back to the clarinet years, I had a very good ear. I had experience with improvised music and I was able to fashion, reasonably well, tonal and chordal sounds that were required given the movement of the music."

"It came to a point where I had a solo. I don't know what the hell I played, but I found out later after that cut, John Hammond called into the studio and said, 'Cecil McBee, where did you get that technique? I love it.' So I became John Hammond's favorite bassist. Benny Goodman was his favorite clarinetist. Billie Holiday was his favorite singer... that kind of thing. John Hammond, after the session, took me over and signed me in as a member of ASCAP."

McBee was picking up other work as well. One day, he was practicing in his room in the Third Street loft. On his own, he had started moving beyond the two-finger technique he had learned. "I thought I would add another one and give myself one-third more possibilities." While working on that one day, he heard a conversation outside a room at the other end of the loft. After a while, someone knocked on his door. "There was this guy standing there with a funny hat on, a trombone in his hand. Stylish attire. His name was Grachan Moncur III. He said, 'McBee. I heard about you. I came to find out if you're available to do some things. I stood outside listening to you practice for a while and I like what you're doing.' I didn't know who he was. I said, 'Sure.' He asked me to a record. He said, 'Next Tuesday, meet me at Lynn Oliver Studio, 87th between West End Avenue and Broadway. That was the place where all Blue Note recordings would be rehearsed. I entered on time, at one o'clock, I almost hit the floor."

In the room chatting and getting set for the session were Tony Williams, Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock.

"I froze," says McBee, recalling the day with both respect and humor. "I had just finished practicing trying to measure up to these guys. What am I doing here? Tony and the guys had heard about me. They were caring and respectful. Happy to see me and hear me, which calmed me down. Come the music, which I was quite concerned about, Moncur put this music on my stand and I said, 'What do I do with it?' He said, 'Just play what I heard you practicing. Just play that.' The record was called Some Other Stuff (Blue Note, 1965). It was a third-stream type concept in the sense that you have no beat responsibility between the bar lines and you just play fluently, in terms of what you hear. He heard me playing that way when I was practicing. It turned out to be OK."

It led to a gig with Shorter at Slug's in New York City with Roy Haynes and Albert Dailey. "The place was packed the whole week. To this day, people talk about that band because it was very exciting for the audience and us. I remember that was really happening. By then, I'd gained a lot of confidence. I was just going where it took me, and playing pretty well at the time. That's how I entered the upper level of the music."

It also led to one of McBee's most cherished musical experiences. During the gig with Shorter, McBee noticed "this tall guy with bushy hair standing at the end of the bar. He was going gracefully wild over what we were doing. Noticeably." Afterward, the man introduced himself. Charles Lloyd approach. He had heard about the bassist and asked him to audition, in advance of a gig in Chicago. McBee agreed. But he flunked the audition. "To this day," he notes, "I can only get to my juices, to myself, when I'm on stage. I can't just practice and demonstrate to anybody that I can do this or that. I have to be on the stage. That's when it comes to me. Period."

But apparently unable to fill the bass chair, Lloyd eventually hired McBee for the gig, which included Jack DeJohnette on drums and Gabor Szabo on guitar. "It was a wonderful experience, especially with Jack, who I had become friends with on the lower east side. We hooked it up. Conceptually. Energy. The whole thing. We were like one person. Whatever would be possible or impossible, we went there. Charles fell in love with that and decided he would keep us together."

Szabo, however, was leaving the group. "Charles asked Jack if he knew a pianist. We were going to do a gig in Boston. He asked if he knew a pianist that might fit in with us. Jack said, 'Yeah. there's this young guy, 19 years of age, in Berklee. Nobody can get along with him, especially teachers because he knows more than them. They can't talk to him. They can't teach him anything.' Charles said, 'What's his name?' Jack said, 'Keith Jarrett.'"

McBee wasn't familiar with the pianist when the group hit at the Jazz Workshop in Boston, but, he says with glee, "Man, that's the best thing that ever happened to me. It was amazing. We did a record called Dream Weaver the following week. (Atlantic, 1966) We ended up going to Europe."

In the midst of that, McBee had an encounter with Miles Davis that he found less than fulfilling. He had decided he wanted more cutting-edge music than Miles was playing at the time, which was still standard-based and not yet into Miles' wilder experiments. Hancock summoned him to a rehearsal at the 77th Street Manhattan home of the trumpeter.

"Truthfully, I had no interest in Miles Davis at all, because of the excitement of having played with Keith and Jack and Charles. I had heard Miles Davis throughout my college years. I knew all about that. I wanted something different. I wanted to go into my area of thought. So we rehearsed all day. I read the music and played it rather well. I think I impressed everybody in the group. Miles was not there, but at the very end of the rehearsal, Wayne and Herbie were at the piano trying to decide how to voice a G7 chord, how to alter it. They couldn't decide what to do. All of a sudden, in through the door came Miles Davis. He went straight to the piano. I was standing next to the piano and Miles didn't acknowledge me at all. He went to the piano and played this chord that was just so beautiful. It called my attention to evidence that Miles is the one that taught everyone, conceptually, what to do at all of those levels that the world loved... Then he turned his back and walked out. Didn't say hello. Didn't say goodbye."

But at a gig in Buffalo days later, it didn't go as well. "We were called onto the stage, Miles being last and the people going crazy, he turned around and looked at me for the first time and said, 'Let's play "So What."' [counts off a fast tempo] Paul Chambers would play [medium tempo]. That's the tempo I'm used to. It's a tune we didn't practice at his home. I had never even played the tune, I had just heard it. [Counts off the fast tempo again]. I was trying to get the notes in the right place, then the bridge came. Just when Miles ends his solo, I miss a beat going into the next solo and Miles looked at me and walked off the stage."

While disappointing, says McBee "I didn't want to play with Miles in the first place. Hindsight told me I should have, because of the opportunity. I just didn't want to repeat what he had done, myself being a composer and an individualist on the instrument who's trying to explore double and triple fingering, which brings other concepts to my bass and writing. With all due respect to Miles Davis and his heroic, world-respected stuff, I was a young kid who wanted to do something else. Keith and Jack were comfortable to me. I was happy to get back to that. Playing with Charles Lloyd's group was well past where I thought Miles was at the time. [The Lloyd group] even discussed it, quite briefly, that we thought we were the select group that had the chance to take the music to the next spot. Keith, Jack, myself, and Charles—all composers."

"When we hit first in Europe, people followed us. We played the Antibes Festival in '66. People followed us all over Europe to hear us play again. We were like the young Beatles of jazz at the time. We were held in Stockholm an extra week because of the popularity of the music. They couldn't get enough people in there. That's what I'm talking about. We had this novel voice. You expected the unexpected. The expectation of something new. It was wonderful."

That was all part of the career of a bassist's bassist, who has played and recorded with some of the best that creative, improvised music has to offer. His name hasn't jumped to the forefront over the years, but he doesn't complain. He takes things in stride and continues to apply himself to his art. "With the Saxophone Summit and the Cookers the last six years, I'm existing again," he says, adding with laughter, "I saw [the great bassist] Buster Williams last night and he said, 'Man, I haven't seen you in years.' I said, 'Well, I'm here.'"

"I'm just starting out," says the artist extraordinaire. "I got a few gray hairs, but they're just starting out too... Hopefully, I can continue to evolve, which is my greatest desire. Music is something that never ends if you're thinking and your creative process is healthy."

Cecil McBee

Professor

- Jazz Double Bass