SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2020

VOLUME EIGHT NUMBER THREE

BRIAN BLADE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

GIGI GRYCE

(May 16-22)

CLARK TERRY

(May 23-29)

BRANFORD MARSALIS

(May 30-June 5)

ART FARMER

(June 6-12)

FATS NAVARRO

(June 13-19)

BILLY HIGGINS

(June 20-26)

HANK MOBLEY

(June 27-July 3)

RAPHAEL SAADIQ

(July 4-10)

INDIA.ARIE

(July 11-17)

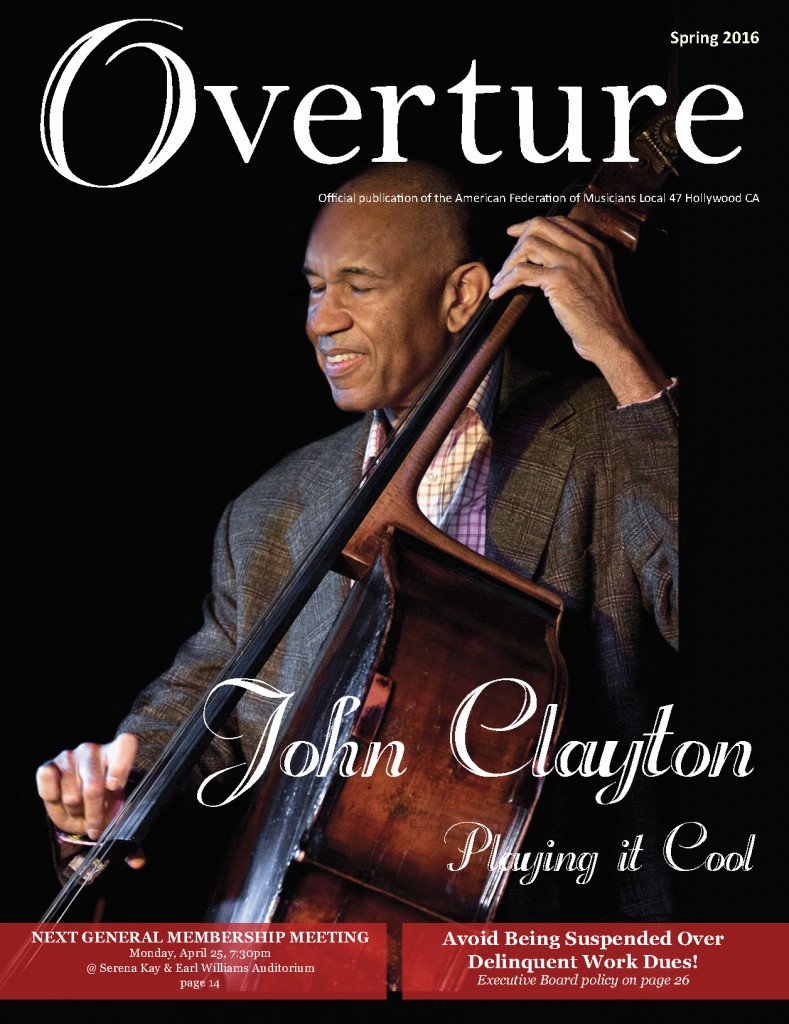

JOHN CLAYTON

(July 18-24)

MARCUS MILLER

(July 25-31)

JAMES P. JOHNSON

(August 1-7)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/john-clayton-mn0000211372/biography

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/john-clayton-mn0000211372/biography

John Clayton

(b. August 20, 1952)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

A multi-talented musician, John Clayton deserves much more recognition. A brilliant bassist whose bowed solos are exquisite, Clayton is also a top-notch arranger and composer. A protégé of Ray Brown (whom he recorded with on a couple of occasions, including a late-'90s collaboration with fellow bassist Christian McBride), Clayton picked up important early experience playing with Count Basie's Orchestra for two years. He has co-led the Clayton Brothers with his younger brother, altoist Jeff, off and on since 1977, and in 1985 put together the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, along with Jeff Clayton and drummer Jeff Hamilton. Clayton's charts for the big band, which are sometimes a little reminiscent of Thad Jones, give it its own musical personality. John Clayton has also worked extensively as a freelance bassist and arranger.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/johnclayton

Career highlights include arranging the 'Star Spangled Banner” for Whitney Houston's performance at Super Bowl 1990 (the recording went platinum), playing bass on Paul McCartney's CD “Kisses On The Bottom,” arranging and playing bass with Yo-Yo Ma and Friends on “Songs of Joy and Peace,” arranging playing and conducting the 2009 CD “Charles Aznavour With the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra,” and numerous recordings with Diana Krall, the Clayton Brothers, Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, Milt Jackson, Monty Alexander, et al.

https://www.vailjazz.org/portfolio-item/john-clayton/

http://www.johnclaytonjazz.com/john-clayton-2-bio/

Artist Blog

John Clayton is a natural born multitasker. The multiple roles in which he excels – composer, arranger, conductor, producer, educator, and extraordinary bassist – garner him a number of challenging assignments and commissions. With a Grammy on his shelf and eight additional nominations, artists such as Diana Krall, Paul McCartney, Regina Carter, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Gladys Knight, Queen Latifah, and Charles Aznavour vie for a spot on his crowded calendar. His many musical pursuits include the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, which he founded along with his brother Jeff in 1986, and the Clayton Brothers quintet, which includes his son Gerald on piano. As a teacher, in addition to presenting individual clinics, workshops, and private students as schedule permits, he directs the educational components associated with the Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival, Centrum Festival, and Vail Jazz Party.

John’s many career highlights include arranging “The Star-Spangled Banner” for Whitney Houston’s performance at the 1990 Super Bowl (the recording went platinum), playing bass on Paul McCartney’s CD “Kisses On The Bottom,” arranging and playing bass with Yo-Yo Ma and Friends on “Songs of Joy and Peace,” and arranging playing and conducting the 2009 CD “Charles Aznavour With the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra,” and numerous recordings with Diana Krall, the Clayton Brothers, the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz, Orchestra, Milt Jackson, Monty Alexander and many others. He will be honored by the California Jazz Society with the Nica Award at the organization’s annual Give the Band a Hand gala at the L.A. Hotel in downtown Los Angeles on April 2.

John took time out of his very busy schedule to speak with Overture’s Linda A. Rapka at his home studio in Altadena.

You are a man of many musical hats, as an accomplished jazz and classical musician as well as performer, composer and arranger. Musically speaking, who do you see yourself as?

It sounds a little cliché, but I identify myself as a music guy. There are kinds of music that I’m drawn to more than other kinds, but that range is pretty broad for me.

Judging from the volumes of music behind us, I don’t doubt that one bit.

I never want to feel like I’ve arrived. I never want to feel like OK, this is what I do. Period, the end. These are the styles of music I play or write. No, please. More. I think most artists are like that.

Who has inspired you, and continues to inspire you?

People inspire me. People give energy. Whether it’s a musician that’s playing something that really touches me and makes my eyes go wide, or an encounter with somebody on the street that really moves me. Somehow that’s going to affect me, and then it’s going to therefore translate through to my music.

What value has the union brought to you as a professional musician?

The union was at the ground level of a lot of negotiating talks when I was doing a lot more studio work. I remember how they fought to go to battle to create better situations, better payment, better conditions for us. When I was younger the Special Payments Fund was brand new. I saw a lot of that going on in the early days. I remember Ray Brown was actually on the Board of Directors when I was a teenager, and he’s the one who really told me what the union could do for me. He said, “Look, if you do a non-union job then the union will never be able to help you. But if you do a union job at least they can go to battle for you if something goes wrong.” I always remembered that.

Let’s talk about your current projects. What is keeping you busy lately?

[Laughs] I don’t want to bore you with the list!

OK – what have you been having fun with lately?

Everything I do I have fun with. I don’t do anything that’s not fun. Period. Life’s too short. A record that we just finished came out with the Clayton Brothers, and I’m really excited about that. We’re a quintet that has my brother Jeff on saxophones and flutes, a great trumpet player who lives in New York named Terell Stafford, a great young drummer named Obed Calvaire, and my son Gerald plays piano. The new album is not only the usual Clayton fun, but also we used it as a vehicle to kind of acknowledge where we are regarding a lot of social struggles that we’re going through right now in this nation. So even though the vibe of the album is basically uplifting, there’s a song on there called “Saturday Night Special.” It’s about a gun that disrupts the peace of a community. I also wrote a song called “Until We Get it Right,” ’cause people are sitting there like, “How long do we have to keep struggling and fighting, and protesting and working?” Basically, until we get it right.

Even that’s empowering because it’s touching on a negative but at the same time positive because you’re saying “Don’t give up.”

Yes, exactly. That was my whole idea. We didn’t want this to be totally a social/political statement and have people feel this dour vibe, this dark cloud, ’cause that’s not what we’re about. We’re playing music, it’s joy, it’s having fun. But there’s another side to us too that is aware and more serious, so we kind of mix that all together. I’m also writing something for the Metropole Orkest, which is this big orchestra in Holland.

What’s unique about it?

The orchestra has been around since shortly after World War II ended, and they still have the same instrumentation. It’s basically a big band with a complete string section and harp and percussion, French horn, oboe, flutes… Vince Mendoza had been the chief conductor of that orchestra for years, and he still spends time there. He asked me to be part of the project, so I wrote something to feature this great singer, Cécile McLorin Salvant. She was one of the past winners of the Thelonius Monk jazz competition. I’m writing right now for the WDR Big Band, which is the Cologne, Germany big band. It’s a lot going on!

I’m amazed you found the time to sit and talk with me.

When you’re gone I’ll get right back to writing!

When you saw your son Gerald becoming this budding musician, were you at all scared your presence as a professional musician might pressure him?

That’s exactly right. We never pushed him, we only encouraged. For instance, I remember having a really negative experience with a professional musician whose music I admire. The experience was so painful to me that I said, I’m not buying any more of his records. I never let Gerald know that experience because if that musician ended up being a really big influence and inspiration to him, I didn’t want to get in the way of it. That’s a small example of supporting, but not pushing.

Let’s talk about your early years, when you first joined the union.

I got to study with Ray Brown when I was 16 years old. Ray Brown saw that I was hungry and interested and eager, so he helped open some doors for me. He would recommend me for jobs he thought I could do. One of them was for an organization that I don’t think exists anymore called the Musicians Wives of Los Angeles. That was probably my first professional job. It was an afternoon luncheon or something like that. I was playing in a quartet or quintet with people, these older jazz guys. I say older; they were older to me then. Jake Hanna was on drums, Bud Shank was on sax, Herb Ellis was on guitar. There I was, 17-year-old kid, scared, green, and I remember Herb Ellis with his one leg up and guitar on his lap, he’d be playing and every now and then he’d kind of swing around and look at me and smile and nod his head. It was so touching, so necessary for this scared kid. I never forgot that. Soon after I needed to be in the union to do these other things I was doing with Henry Mancini and stuff like that.

Ray Brown was very much a mentor.

He was the definition of mentor. He was not kind of a mentor, he was the mentor of mentors for me. Again, he saw how hungry I was. He let me follow him around. He became almost more of a father figure for me than my real father, because he connected with me on this level, this music level that even though my parents supported, they really didn’t understand. Ray Brown would look at me and say, “Here’s what you gotta do.” That was one of his often-used phrases before he started talking to me. I remember one time when I was in the studio with him, and was getting star eyes about studio work. Here’s Ray Brown, here’s Quincy Jones, Sweets Edison, there’s Snooky Young, there’s all these jazz greats. I said to him, “When I’m done with school, do you think you can help me get into studio work?” And he exploded. He started screaming at me and cursing, “Are you out of your effin’ mind, you don’t even know how to play the effin’ bass, and you wanna play this B.S.? First thing you gotta do is get your ass out there and learn how to play the bass from here to here, from top to bottom, and then get out there and make some music. And if you wanna play this when you’re done, it’ll still be here.” I was so frightened, he’d never talked to me that way. So basically I did what he said. And he was right. Years later I said to him, “Do you remember that time you blew up at me?” He said “Oh, do I ever. I was afraid you were gonna get sucked into this studio world and not know how to make any music.” That was a huge lesson for me.

You did eventually find your way to the studio, working with just about everyone. What is that part like, working with other artists?

It’s just an extension of touching the music. It’s an extension of it, but obviously it poses other challenges. Not only do you have to learn how to perform live but the whole recording life and the studio life requires different ways of doing things. If I’m writing or arranging for an artist, then I have to think differently than I would for a live concert if it’s a studio thing. You never know what the song and the vocalist or the instrumentalist is going to require for the project. It may be that you create a sound and a vibe that you can only do in the studio.

Getting into that vibe, that groove – what’s that process? How do you get to that place?

It’s collaborative, but it always starts from within. There’s a mantra that I use: “So go I, so go they.” However I am, I am going to allow others to be that way as well. If I am in a room with my musician friends and I’m upbeat and happy and ready to go and really into it, then that invites them to be that way as well. Because at our core is a big part of us that’s chameleon-like. We want to empathize, we want to be like others around us. Especially as a bandleader I have to remember this, because a lot of times people look to me to set the tone, and I need to set the right one.

That’s a good lesson not only in music, but in life. Well, music is life, so…

[Laughs] You hit the nail on the head! Most of the stuff that I deal with in my music, I’ve learned from life lessons, and books and talks about life lessons. When I do the workshops and teaching that I do, 75% of what I talk about is that — more than playing the instrument, more than the other musical things. There’s a lot of negativity out there so I have to help them understand how they need to bring their light to every situation that they deal with.

What’s the most important thing you share with your students?

You’re going to hear stuff by well-meaning people saying things like, “It’s really rough out there. There aren’t as many jobs as there used to be for all the people graduating.” It’s creating a fear in younger musicians; a fear-based education. I try to help the young people understand, number one, statistics never apply to art. Never in the history of our music have there been, quote, “enough” jobs for the people that are graduating. Ever. Number two, the doors of opportunity open for you based on the level of your art. It’s not the networking, it’s not trying to have something to fall back on. In our world, too often I might hear about a student who wants to be a Music Ed major because they’re encouraged to have something to fall back on. Basically what they’re saying to me is, “I really want to play, but if I fail, let me mold your children’s minds.” [Laughs] I don’t want you near my kids! The teacher says, “I’ve got to teach, I must teach.” That’s the one I want to teach my kids.

There’s the danger of “falling back” in case of failure becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The thing is that we — adults, teachers, professional musicians — too often will look at our trajectory and how we have made it to the point that we are. In everybody’s lives you get to a point where you look back on your life and say, “Things are different now. It’s not like when I was growing up.” But really what’s going on is when we’re younger, we’re learning music, and we’re moving up, and at some point the telephone starts to ring. We start working. Music continues, and at another point the phone doesn’t ring as much anymore. So what do we do? We blame the music business instead of looking at ourselves and saying, “What do I need to add to my music to allow me to have doors open for me as well with what’s going on today?” There are not fewer opportunities. There are more opportunities.

They’re just different. I think a lot of times that gets overlooked.

I do too. Being connected to the world now there are more opportunities, different opportunities. Just like when we were younger, you have to be creative in terms of how your tailor-made life will look. There never has been one recipe for getting where you want to go.

How can musicians better adapt to today’s musical landscape?

Look in a mirror. Admit to yourself what it is that you need to add to your music that will allow you to achieve those higher levels. Too many people are too quick to blame the music business, and it’s on you. We can’t compare ourselves to other people because the beauty of what we do is that it’s tailor made. Once you actually dive into the pool, then you realize, “Yeah, OK, I’m swimming. I didn’t know how I was gonna do this, but I’m doing it.” That still is a part of my life. When I stand in front of a big orchestra and I’m conducting something, I always in the back of my mind think, “Will this be the time that everybody discovers that I really don’t know what the hell I’m doing?” No two people in life have ever followed the same path to get to a lot of the same places. You have to dare.

Learn more about John Clayton and keep

updated on his many current projects

at johnclaytonjazz.com.

https://forbassplayersonly.com/interview-john-clayton/

Performer,

educator and bandleader talks about studying with Ray Brown, working

for Henry Mancini and performing with the Amsterdam Philharmonic

Performer,

educator and bandleader talks about studying with Ray Brown, working

for Henry Mancini and performing with the Amsterdam Philharmonic

Exclusive interview with FBPO’s Jon Liebman

October 18, 2010

John Clayton began learning the double bass at age 16, studying with bass legend Ray Brown. By age 19, John had become a bassist on Henry Mancini’s television series, The Mancini Generation. In 1975, he graduated from Indiana University’s Jacob School of Music with a degree in bass performance.

John toured with the Monty Alexander Trio and the Count Basie Orchestra before taking the position of principal bass in the Amsterdam Philharmonic Orchestra in the Netherlands, where he stayed for five years. He eventually returned to the U.S. to focus on working in the jazz world. John co-founded the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra with his saxophonist brother Jeff Clayton and drummer Jeff Hamilton. From 1999 to 2001, John served as Artistic Director of the Jazz for the Los Angeles Philharmonic program at the Hollywood Bowl and has also led many jazz education programs.

FBPO: Tell me about your musical upbringing. How did you end up as a bass player?

JC: Music was always in my home because my mom played piano and organ and led the church choirs. When I was in junior high school, I asked the band director if I could play that “big thing over there.” He wrote down tuba on his pad. As I was walking out the door, I saw these four gorgeous, brown, wooden majestic instruments and said, “Ooh. Can I play that instead?” He crossed off tuba and wrote down my future.

FBPO: Studying bass with Ray Brown must have been quite an experience! What kind of teacher was he? What kind of man was he?

JC: Ray Brown was the perfect teacher, mentor and father figure for me and for many others. I learned so many life lessons from him. I learned about bass, patience, respect, joy, jokes, business, record companies, traveling with the bass, being a member of the “bass family” and so much more. In the extension course he taught at UCLA, he had all of us learn all the major and minor scales in two and three octaves, all chord types, walking bass lines and singing melodies while accompanying ourselves on the bass. He brought in Carol Kaye, classical players and played recordings of bassists like Richard Davis, Scott LaFaro and Israel Crosby. I was only 16 at the time and I had never heard of any of these people! Based on those examples alone, I think you can imagine what kind of a person he was.

FBPO: How did you get the gig on Henry Mancini’s TV show? Weren’t you still a teenager at the time?

JC: Ray Brown! He is the one that opened many doors for me. When I was 19 years old, I got a call from Mr. Mancini’s contractor, saying that he wanted me to play his TV show. The dates conflicted with my plans to start at Indiana University. I called Ray, of course. “Meet me at RCA studios at 10 a.m. on Monday. I’ve got a recording session with Hank. We’ll talk to him.” Nervous, scared and green, I went to the studio. Ray introduced me to Henry Mancini on a ten-minute break. “I’ve heard a lot about you. Will you be able to play my show?” Ray explained that I could only do a portion of the show and then needed to start school. Would it be okay to do the show until I had to leave? “Sure! Bloomington? Good school. I get my touring orchestra out of Bloomington.” And that was that. During those years, I toured with Henry Mancini to pay my way through school.

FBPO: What kind of experience did you have at Indiana University? Were Stuart Sankey and Murray Grodner there at the time? Did you study with either of them?

JC: It’s embarrassing how naïve I was. I had never heard of Murray Grodner, though he was a good friend of Abe Luboff, my classical teacher in LA. I hadn’t heard of jazz icon, David Baker, either! Both were at IU. Murray Grodner was the perfect no-nonsense, supportive pedagogue that I needed. He had tissues on his desk for the students that would break down under his pressure! I still love the guy. And, by the way, I never broke down!

FBPO: I’ve always thought of you as a jazz guy with good, solid arco chops. In looking at your history, though, it almost seems like you’re a classical guy who got bitten by the jazz bug. What’s the story?

JC: To be honest, it all kind of happened at the same time. As a kid, I was in beginning strings, junior orchestra, high school jazz band, orchestra and a soul/R&B group. It was all just music and I loved every situation. I loved to swing as much as I loved playing concerti. I’m still that way. My chicken and egg arrived simultaneously.

FBPO: How did you get the gig with the Amsterdam Philharmonic? What was it like living over there for five years?

When I moved to Holland, I told a drummer friend that I was interested in playing solos with orchestras. He knew people in the orchestra world and he told me there was an opening in the Amsterdam Philharmonic for a “Solo” bassist. Solo bass means “principal.” Of course, I didn’t mean principal – I meant that I wanted to stand in front and play solos! But I took the information, thought about it, took the audition and was invited to join. Incidentally, I eventually did get to play a concerto with our orchestra. It was an awesome time for me. I love Holland, the people there, the way of life, their music scene… It was hard to leave.

FBPO: Why did you? What brought you back to the U.S.?

JC: I wanted to pursue writing for films, playing in studios, that sort of thing. I do write and I love writing, but I am no longer interested in writing for film. I had planned on being in Holland for two years. It was so wonderful that I stayed for five! In that five-year period, my wife and I started a family. We have a daughter and a son.

FBPO: Tell me about the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra. How did that group come to be?

JC: Drummer Jeff Hamilton, my best friend, and I would often listen to records together. A lot of the recordings were of our favorite big bands, like Thad Jones & Mel Lewis, Count Basie, Woody Herman, Duke Ellington, etc. I got bitten by the writing bug when I was with Count Basie and we started talking about how cool it would be to start something when I would eventually return to LA. Along with my brother Jeff, that’s what we did. We’ve been together twenty-six years now. It’s like a family. In our band, people either quit or die. It’s a pretty wonderful family vibe.

FBPO: In addition to being a long-established performer and prolific composer/arranger, you’re also known as a music educator. Tell me a little about that part of your career.

JC: I’m lucky that I love to teach. Well, guide, really. I don’t believe I teach anyone anything; I think we teach ourselves. But the role of coach, inspirer, guide … whatever, is important. Ray Brown and the musicians in his world were people who gave and shared their talent and knowledge. Ray especially never allowed me to understand anything but passing on knowledge and giving to others. I give as many clinics and workshops as time will allow and only recently gave up my post at USC. I taught there for 21 years.

FBPO: I had the pleasure of seeing you perform in a bass trio with Christian McBride and Rodney Whitaker at last year’s Detroit International Jazz Festival. Do you find people comparing your bass trio to that of Stanley Clarke, Marcus Miller and Victor Wooten? Or even the one made up of Jeff Berlin, Stuart Hamm and Billy Sheehan?

JC: No. Even if someone does make those comparisons, it wouldn’t affect what I do. It’s all about honestly presenting what you have to express. The worst thing you can do is compare your insides to someone else’s outsides.

FBPO: What lies ahead for you and your career? What can we look forward to seeing from John Clayton in the future?

JC: We just released a new Clayton Brothers Quintet recording, called The New Song and Dance. That was a big deal for me. A lot went into that project! Other things include concerts with the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, launching a recording series called “The John Clayton Parlor Series,” innovative programming for the Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival and the Centrum Jazz Workshop, some recordings I’ve produced and preparing more Bass Tips to post on my website. There’s more, but I don’t want to bore you with even more talk about myself!!!

FBPO: What do you like to do when you’re not immersed in music?

JC: Cooking, fishing, hiking, discovering wine and…oh, wait. Did you say when I’m not immersed in music? Okay. That answer would be … sleep. And I don’t often get to do a whole lot of it.

https://www.notreble.com/buzz/2012/12/06/brotherly-love-an-interview-with-john-clayton/

Few names are as ubiquitous in the jazz community as John Clayton. As a prominent bassist, arranger, and composer, Clayton’s incredible musicianship has kept him busy since he was a teen with artists like Henry Mancini, Quincy Jones, Queen Latifah, DeeDee Bridgwater, and Dr. John, just to name a few. Most recently he collaborated with Paul McCartney for Macca’s Kisses on the Bottom album and Live Kisses DVD.

He’s also an experienced band leader with The Clayton/Hamilton Orchestra and The Clayton Brothers Band. Featuring brother Jeff on sax and son Gerald on piano, the Clayton Brothers have just released The Gathering on the crowdfunding label ArtistShare.

A pupil of bass legend Ray Brown, Clayton’s commitment to bass is evident in his playing as well as his dedication to education. He often teaches workshops, but has been offering free bass tips on his website for general guidance.

We reached the bassist at his home studio in Los Angeles to ask about the new Clayton Brothers album, arranging, working with Paul McCartney, bass education, and studying with Ray Brown.

Great! We had a lot of support, and it’s really fun to play with this group. I don’t have to think, you know? I don’t have to adjust. Everybody knows what everybody else kind of likes and we kind of push each other along and inspire [each other]. It’s not business as usual, but there are so many basic things you don’t have to think about.

Never. I tried that, but it doesn’t work. The kind of stuff we do

requires that you have your own instrument; not just a decent

instrument. I can get my hands on a decent instrument, but strings are

going different, the setup is going to be different – the strings might

be closer to the fingerboard or the might be further from the

fingerboard – and next thing you know you can’t get a sound or you’re

killing yourself to play it. Now we’re talking physically when you’re

plucking those strings… it gets bloody. [laughs] Literally. So I kind of

want my own instrument.

I keep it high enough to keep the instrument happy. In other words,

if the strings are too high off the fingerboard it chokes off the sound.

If the strings are too close to the fingerboard, you don’t get a sound.

I can adjust, so there’s not like a certain millimeter that I look for

from the string to the fingerboard, I mainly just go for whatever is

going to allow [the instrument to sound].

And I try to make sure it’s playable. My criteria is that if I take the bow and try to play forte with the bow and make it really full, when I push down with the bow, if the string touches the fingerboard then the strings are too low. So then I’ll raise it up to just beyond that point.

Well it was kind of my brother’s idea. He wanted to do something that

would allow us to basically gather: gather friends, gather music, and

the gathering of friends meant in a sense that we were gathering a new

sound, if you will. And that was really it. That was the vibe, just kind

of like, “What can we do that will be fun for us and also give us a new

sound?”

Yeah, but not a lot of jazz. My mother played piano and organ in

church and sang in the choir. So we always had music in the house with

her practicing and rehearsing with groups. Then we listened to the

radio, but we were listening to our pop music of time, which was rhythm

and blues and soul music. Stevie Wonder, The Temptations, The Four Tops,

Gladys Knight and the Pips, Ray Charles… That’s what we were listening

to. Then my brother and I got into the high school jazz band and that

just opened up our heads.

You know the whole family thing was almost accidental. My brother and

I, we didn’t have a group. We were just playing music separately and

together, but less together than when we were adults. As kids, we just

did all the kid stuff: playing in the high school bands and in our own

little bands. He’d have his little bands and I’d have my little bands.

We played in church occasionally. My mom allowed me to play in Church as

often as I wanted, but she didn’t allow my brother in the beginning to

play that “heathen” saxophone in church. [laughs] He ended up singing in

the choir and eventually she turned her thoughts around and he was able

to play sax in church.

But that was really it. As for the family thing, like with Gerald… my brother and I put together [The Clayton Brothers] in the ’70s and recorded then. After Gerald was born, of course he grew up at our side watching and listening and all that. When he started playing piano and progressed, I had a couple of little gigs for him and said, “Hey, want to play with us here?”, and he did. When he was graduating from college I said, “You know, of course we’d love to have you in the Clayton Brothers more permanently, but it’s totally your decision. If you want to go your own way and all that, [I understand].” I didn’t want to pressure him to play in “dad’s group.” He’s got his own ideas, but he said, “Actually, luckily for me it’s been my dream to play in The Clayton Brothers group.” So that was a really nice thing to hear.

Yeah, especially since I wanted his voice there. So that’s kind of how all that happened. It all just sort of naturally flowed.

I think in the jazz world, it’s heading more and more like that. I

like it, because it gives you a chance to develop a relationship with

the people who are interested in what you do. With the other model we

got used to, you’d walk into a record store – remember those things?

[laughs] You’d walk in and you’d kind of browse through CDs that look

interesting. That’s gone. You can’t do that anymore.

So when [someone] puts out a new CD, there’s no way I’m going to know it exists because I can’t go browse in a record store anymore.

Now there are just so many hundreds of thousands of choices online that I have to look through to discover somebody’s CD. That ain’t gonna happen either. Radio stations are a really great way to discovers sounds I want to find, too, but that’s still limited. I’m not going to be able to find the fly-under-the-radar people. The other thing about the old model is that when I would by your CD, I’d pay for it – whether online or in a store – and I would take it home and enjoy it and you would never know that I existed. You would just hopefully get your royalty from the sales and that would be it.

With this other model, that’s gone. Now, if somebody in Kentucky is interested in what I’m doing, I now have their contact information. I can send them a thank you note. I can let them know that I’m actually going to be playing in Louisville and hopefully we can meet. Not only are you developing your relationship with people who like what you do, but you’re also creating this community atmosphere where since I’m in touch with you I can build this community. I can let you know what I’m doing and you’re not paying anymore for a CD. You’re paying for a chance to be part of the whole artistic process, which I find really cool.

Can you imagine if more artists were doing this? If you could follow along with Herbie Hancock or Wayne Shorter in the beginning and see what songs they’re thinking of doing on their next project and how their songs are evolving, or maybe peek in on one of Herbie Hancock’s rehearsals. You know, I think everyone would jump at that chance. That’s the goal of what we’re doing with ArtistShare. It lets people really be a part of the whole process, not just get a CD at the end of the day. They get to watch it unfold.

Well, another reason I don’t want to is because I own my music. When

you record for Concord or Verve or Blue Note or whatever, you don’t own

your music. They pay for the recording, sure. They pay for the

musicians, they pay to have it pressed, they pay for advertising and all

that stuff. But then they say, “You’re not going to get any money until

we recoup our expenses, and then we’re going to pay you a royalty of

less than ten percent.” So less than ten percent of your work, of your

blood sweat and tears, of your sales… that’s what you’re going to get

after [they] recoup all the money that they pay in. And the big lie is

that they never tell you when they recoup. You could say, “Hey by the

way, am I going to start getting royalties now for that last record I

made?” And they’ll say, “No, we’re still paying off the expenses, you

know. We took out an ad here, we took out an executive here, and we had a

deal there, and we had a broiled salmon lunch there.” [laughs] And as a

result, they can keep stringing you along and you never see a royalty.

Then also, think about the fact that let’s say [you] move on to your next record label. Everything that you have done on Blue Note is still on Blue Note. Maybe your sales weren’t really great on Blue Note, but suddenly you’re a hit on this other label. Well, because you’re a hit on that other label, out of the vaults come all of these rejected cuts and b-rolls that you did on the first label that at the time they said wasn’t up to snuff and wouldn’t sell. Now, since you’re so popular and the world is going crazy over your music, they look in their vaults and they start finding things that they can now release that you weren’t happy with initially. And they do things like try to ride the wave of your new success by repackaging some of your old CDs. Suddenly there’s a “best of” CD on your old label that you’re no longer with. Why can that happen? It’s because they own your music and they can do anything they want with it because they paid for the recording, they paid for the pressing, the mastering, artwork, all that stuff.

With [the crowdfunding model], I take the monies that we get – and I usually have to add my own money to it as well – and pay for the recording and the pressing and the cover art and all that stuff. But I own it. The thing about ArtistShare is instead of the old model where they keep ninety percent and give you ten percent or less in royalties, they take fifteen percent of all money coming in, and the artist gets eighty-five percent.

I’ve never been with a record label where I get eighty-five percent of the monies taken in. That’s from day one when somebody says they’re going to be a participant. If a participant comes in at the basic level, then I get eighty-five percent of that. To me, it’s better all around.

I would say focus on the music and build your audience one

participant at a time. Think of it as building your house and you’re

going to build your house one brick at a time. When you build your

house, you don’t get impatient. You can see that this brick is going

there. It’s like, “I’ve got a house to build, but hey – I’m doing it!”

To me, that’s what it’s all about. Just be patient and keep working. If

you stop laying bricks, then the house isn’t going to get built.

But I think the focus needs to be about the music. The buzz that’s going to be created about you is always going to be about your music. It’s not going to be about who you know, who you date, who you marry, or how big your house is. No, it’s always going to be about the music. If you focus on the music then the other stuff falls into place.

I keep things fresh by thinking about the sounds of each person.

First of all, mood kind of directs the compositions I write. So maybe

I’ll think, “Ok, I need an exciting song.” Then I think, “I need an

exciting song for Jeff and for Terrell [Stafford].” Then I start

thinking about Terrell and Jeff’s sounds, and I think, “Where do I want

to go with this,” because I’m hearing how they sound when they’re really

exciting to me, and I’m hearing what Gerald is doing on the piano when

he’s really exciting to me. When I have those elements in place, it

takes me down whatever road. That’s what keeps it really fresh for me. I

just think about the musicians and what they do and how they impress

me, then I go from there.

Definitely. I know that I’m not capable of doing something like that.

It’s coming from another source. You know, the universe, the spirit in the air, whatever it is. I’m just the conduit.

Yes, but not in a religious way.

I knew how to transpose for the instruments and I asked Count Basie if he would mind if I wrote a piece. He said to go ahead and I did. I brought it in and the band rehearsed it and it bombed. It was so bad. It just sucked. The guys were like, “Ok John! Alright man!”, but I knew it sucked. We had like a two week break and I went home and I took this record that the Basie band had made that I loved. It had a song on it we played every night called “Splanky,” and it has this amazing shout chorus. I just transcribed it. I couldn’t hear every note, but I transcribed as much as I could. I analyzed it, and I used a lot of what I learned from that to write my own song, which is called “Blues for Stephanie.” I went in and the band played it, then Count Basie said, “Let’s do that one more time.” It was very cool.

It would always be two steps forward and one step back, because as soon as I thought I knew what I was doing I would write something and it would really sound terrible. I’d try to edit it and stuff, and the guys in the band would say, “What are you doing?” I’d say, “Well I’ve gotta change this and change that,” and they would say, “Why?” I’d say, “Well, it didn’t sound right,” and they would always say, “Just write another one! Don’t try to edit the one you did. If there’s stuff you didn’t like – don’t do that!” They really encouraged me to write right, and that’s how I learned.

You have no idea. I could call the saxophone section to my hotel room

to read 16 bars of something I wrote just to see what it sounded like.

The brass would rehearse 24 bars of something I’d written just before

the concert. [They were] always accommodating. They never said no. It

was very cool.

He’s one of the most normal yet sensitive, fun-loving, easy people

I’ve ever worked with. He can laugh with you. He is totally honest about

himself. So, he would say things like, “I don’t know what this chord

is, but this is what I’m hearing. I don’t know what you call this, but

this is what I’d like for us to do.”

For instance, one of the songs that we did was “The Glory of Love.” We did it and rehearsed it in the studio and everyone contributed ideas. Then we recorded it and when we were done, it was kind of like, “Ok, let’s move on.” But Diana Krall said, “Can we do that one more time? And this time, Paul, I just want to have it be a duet between you and John in the beginning.” So that’s the way we did it. He’s open that way, and that’s the kind of freedom that he encourages. That’s the kind of creativity that he’s about. So I highly respect that guy.

He also would make you feel comfortable. He never made you feel like

he was a prima donna or that he was the great Sir Paul McCartney. Never.

Not one time. Being in the studio, every day I’d see him. He’d see me

and he’d walk over and give me a big hug. He initiated it – it wasn’t

like I was.. [laughs] I thought, “Man, how lucky am I to wake up in the

morning and have Paul McCartney give me a hug.”

I have to say it was an amazing experience, and he’s one of the loveliest people on the planet.

I remember working on a video with Ray Brown, and his whole thing was

he didn’t want the video to take the place of a private teacher. He

wanted it to be something that a player could go to and reference at

anytime they wanted to when they weren’t there in the studio with their

private bass teacher. Here’s something hopefully that they could

supplement what the rest of their life was about.

I’m kind of picking up on that theme. I know that there are a lot of people who are scratching their heads about how to do things. And maybe their school director doesn’t have the answers that they’re looking for, so I kind of was thinking from that perspective of “Ok, what are the common denominators that we all realize and that we all do?” You know: left hand, right hand, posture, etcetera. There are so many different ways of playing the bass and to me they’re all good unless they do damage to you physically. That’s the only criteria for me. If it’s hurting you physically then no, but other than that you can have the bass higher, you can have the bass lower, you can have the bass tilted, you can have the bass straight up, you can have the bass with an angled endpin, you can have a straight endpin. There are so many ways to play the instrument and they all work for the individual. So I try to find the common denominators and focus on those and also talk about the things that work for me. I use the angled endpin after 30 years of playing with a straight endpin. I know the benefits of both.

So it’s like that. I want my bass tips to naturally go wherever I see the need for some commentary and some visual instruction. Through the years with all the teaching I’ve done, I kind of have a list of things that I often say, and I’m allowing those things to guide how I make my bass tips installments. Stuff that you already know, like why should the elbow be more up? Well, because when you’re touching the strings on the fingerboard and your elbow is down, look at the shape of your hand and the shape of your wrist. That shape shows you that you’re going to have a blood flow problem, and when you have a blood flow problem and you have to use your muscles with that impeded blood flow, now you’re looking at possible severe problems. All those things are things we’ve learned as we’ve learned more and more about the bass and playing the bass. So, those are the kind of things that are on my list that I always talk to people about, and I’m just trying to kind of go down [that list].

[laughs] Yeah, I guess. I feel like it’s not about making a DVD to

sell. I think for the most part those days are gone. As soon as you make

a DVD, it’s going to be on YouTube. Why charge somebody for it, because

eventually eventually everyone is going to have it free anyway.

Demanding, but not unreasonable. Everything he said made sense. He’d

say, “You have to learn all of your triads – major triads, minor triads.

All of your chord types – major 6th, minor 6th, dominant 7ths, minor

7ths, major sevenths, minor with a major 7th, augmented 7ths, diminished

7ths. You have to learn all of your scales. You have to learn how to

play the whole bass – from the scroll to the bridge.” He’d say, “You

know, music is going to kick your butt enough. You don’t want to have

the bass kick your butt, too.” He was relentless about that. He’d say,

“You’re playing tunes. You’ve got to learn tunes. Learn them in all

keys.” It was like that. He was tough, but not unreasonable.

Yes. I wouldn’t say tough when I talk about his personality. I would

say strong. He was strong about what he felt and strong in his business

practice. Strong in his conviction about the bass. But, he was such a

community guy. He was such a village guy. He was totally about fun. He

hated being in L.A. because he thought about the fun that he could be

having touring. If he was home two or three weeks in a row, he’d say,

“Get me out of here!” [laughs] He just loved playing. He was a

remarkable guy.

Next for me is a mixture of writing and playing projects. So I’ve got

some commissions I’m doing for various ensembles. I’ve got that writing

stuff to do. I’m going to bring out a new series on CD that initially

will start out as a duo series. I’m calling it “The Parlor Series,” as

if I would invite you into my home and into my parlor and say, “Hey, put

your feet up. Here’s a drink, and so-and-so and I are going to play

some music for you.” The first one is going to be out… I’m shooting for

the spring. It’s going to feature my son and myself. I’ve already

recorded two others – one with Hank Jones and one with Mulgrew Miller.

So those are going to come out eventually, too. It’s just my own little

bucket list dream. Stuff that I want to do, like make some duo

recordings with people that I want to play with. Right now it’s piano

but I expect to expand it. It could be guitar, it could be two basses,

whatever.

https://jazztimes.com/archives/john-clayton-band-on-off-the-hill

https://tedpanken.wordpress.com/2014/08/20/for-bassist-john-claytons-62nd-birthday-a-downbeat-feature-from-2010/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Clayton_(bassist)

Clayton began studying double bass at age 16 with Ray Brown. Three years later he was bassist on the Henry Mancini's television series The Mancini Generation. In 1975, he graduated from Indiana University.

He went on to tour with the Monty Alexander Trio and the Count Basie Orchestra before taking the position of principal bass in the Amsterdam Philharmonic Orchestra in Amsterdam, Netherlands. After five years he returned to the U.S. for break from the classical genre and founded the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra with his brother, saxophonist Jeff Clayton, and drummer Jeff Hamilton. He also performed in a duo as the Clayton Brothers with musicians such as Bill Cunliffe and Terell Stafford.

He has been Artistic Director for the Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival, Sarasota Jazz Festival, Santa Fe Jazz Party, Jazz Port Townsend Summer Workshop, Jazz at Centrum[1] and Vail Jazz Workshop. From 1999 to 2001 was Artistic Director of Jazz for the Los Angeles Philharmonic program at the Hollywood Bowl. He conducted the All-Alaska Jazz Band. He has taught at the University of Southern California Thornton School of Music and has served as president of the International Society of Bassists.

He has composed and arranged for The Count Basie Orchestra, Diana Krall, Whitney Houston, Carmen McRae, Nancy Wilson, Joe Williams, Ernestine Anderson, Quincy Jones, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Natalie Cole, Till Bronner, and The Tonight Show Band.

In 2006, his son Gerald Clayton came in second at the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Piano Competition.

With others

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/johnclayton

John Clayton

John Clayton

John Clayton is a natural born multitasker.

The multiple roles in which he excels — composer, arranger, conductor,

producer, educator, and yes, extraordinary bassist — garner him a number

of challenging assignments and commissions. With a Grammy on his shelf

and eight additional nominations, artists such as Diana Krall, Paul

McCartney, McCoy Tyner, Milt Jackson, Regina Carter, Dee Dee

Bridgewater, Gladys Knight, Dr. John, Queen Latifah, and Charles

Aznevour vie for a spot on his crowded calendar.

He began his bass career in elementary school playing in strings class, junior orchestra, high school jazz band, orchestra, and soul/R&B groups. In 1969, at the age of 16, he enrolled in bassist Ray Brown's jazz class at UCLA, beginning a close relationship that lasted more than three decades. After graduating from Indiana University's School of Music with a degree in bass performance in 1975, he toured with the Monty Alexander Trio (1975-77), the Count Basie Orchestra (1977-79), and settled in as principal bassist with the Amsterdam Philharmonic Orchestra in Amsterdam, Netherlands (1980-85). He was also a bass instructor at The Royal Conservatory, The Hague, Holland from 1980-83.

In 1985 he returned to California, co-founded the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, rekindled the The Clayton Brothers quintet, and taught part-time bass at Cal State Long Beach, UCLA and USC. In 1988 he joined he faculty of the University of Southern California Thornton School of Music, where he taught until 2009. Now, in addition to individual clinics, workshops, and private students as schedule permits, John also directs the educational components associated with the Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival, Centrum Festival, and Vail Jazz Party.

He began his bass career in elementary school playing in strings class, junior orchestra, high school jazz band, orchestra, and soul/R&B groups. In 1969, at the age of 16, he enrolled in bassist Ray Brown's jazz class at UCLA, beginning a close relationship that lasted more than three decades. After graduating from Indiana University's School of Music with a degree in bass performance in 1975, he toured with the Monty Alexander Trio (1975-77), the Count Basie Orchestra (1977-79), and settled in as principal bassist with the Amsterdam Philharmonic Orchestra in Amsterdam, Netherlands (1980-85). He was also a bass instructor at The Royal Conservatory, The Hague, Holland from 1980-83.

In 1985 he returned to California, co-founded the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, rekindled the The Clayton Brothers quintet, and taught part-time bass at Cal State Long Beach, UCLA and USC. In 1988 he joined he faculty of the University of Southern California Thornton School of Music, where he taught until 2009. Now, in addition to individual clinics, workshops, and private students as schedule permits, John also directs the educational components associated with the Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival, Centrum Festival, and Vail Jazz Party.

Career highlights include arranging the 'Star Spangled Banner” for Whitney Houston's performance at Super Bowl 1990 (the recording went platinum), playing bass on Paul McCartney's CD “Kisses On The Bottom,” arranging and playing bass with Yo-Yo Ma and Friends on “Songs of Joy and Peace,” arranging playing and conducting the 2009 CD “Charles Aznavour With the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra,” and numerous recordings with Diana Krall, the Clayton Brothers, Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, Milt Jackson, Monty Alexander, et al.

https://www.vailjazz.org/portfolio-item/john-clayton/

john clayton | website

Los Angeles native John Clayton began seriously studying the bass at 16 with Ray Brown. At 19, the Grammy® winner and eight-time Grammy® nominee became the bassist for Henry Mancini’s television series “The Mancini Generation.” After receiving a Bachelor of Music degree in double bass in 1975 from the University of Indiana, John toured with Monty Alexander and Count Basie & His Orchestra. He moved to Amsterdam and was principal bassist in the Amsterdam Philharmonic for five years. Highly regarded for his work as a composer and arranger, John has been guided by, among others, Robert Farnon, Count Basie, Johnny Mandel, Mancini, Marty Paich and Frank Foster. He has written and arranged music for Diana Krall, Dee Dee Bridgewater (including her Grammy®-winning Dear Ella), Natalie Cole, Regina Carter, Milt Jackson, Nancy Wilson, Quincy Jones, George Benson, Paul McCartney and Dr. John. He is co-leader of the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra and the Clayton Brothers Quintet. John directs the educational components associated with the Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival and Centrum Jazz Workshop, he is Director of Education and a Board member of the Vail Jazz Foundation and has been Director of the Vail Jazz Workshop for the past 20 years.http://www.johnclaytonjazz.com/john-clayton-2-bio/

Biography

John Clayton is a natural born multitasker. The multiple roles in which he excels — composer, arranger, conductor, producer, educator, and yes, extraordinary bassist — garner him a number of challenging assignments and commissions. With a Grammy on his shelf and eight additional nominations, artists such as Diana Krall, Paul McCartney, Regina Carter, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Gladys Knight, Queen Latifah, and Charles Aznavour vie for a spot on his crowded calendar.

He began his bass career in elementary school playing in strings class, junior orchestra, high school jazz band, orchestra, and soul/R&B groups. In 1969, at the age of 16, he enrolled in bassist Ray Brown’s jazz class at UCLA, beginning a close relationship that lasted more than three decades. After graduating from Indiana University’s School of Music with a degree in bass performance in 1975, he toured with the Monty Alexander Trio (1975-77), the Count Basie Orchestra (1977-79), and settled in as principal bassist with the Amsterdam Philharmonic Orchestra in Amsterdam, Netherlands (1980-85). He was also a bass instructor at The Royal Conservatory, The Hague, Holland from 1980-83.

In 1985 he returned to California, co-founded the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra in 1986, rekindled the The Clayton Brothers quintet, and taught part-time bass at Cal State Long Beach, UCLA and USC. In 1988 he joined the faculty of the University of Southern California Thornton School of Music, where he taught until 2009. Now, in addition to individual clinics, workshops, and private students as schedule permits, John also directs the educational components associated with the Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival, Centrum Festival, and Vail Jazz Party.

Career highlights include arranging the ‘Star Spangled Banner” for Whitney Houston’s performance at Super Bowl 1990 (the recording went platinum), playing bass on Paul McCartney’s CD “Kisses On The Bottom,” arranging and playing bass with Yo-Yo Ma and Friends on “Songs of Joy and Peace,” and arranging playing and conducting the 2009 CD “Charles Aznavour With the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz Orchestra,” and numerous recordings with Diana Krall, the Clayton Brothers, the Clayton-Hamilton Jazz, Orchestra, Milt Jackson, Monty Alexander and many others.

Copyright © 2020 John Clayton Jazz

An Interview with John Clayton

NOTE: Interview conducted by Paul Read on Jan 10, 2018 at 2:30 PST.

ISJAC: Hey, John. Thanks for doing this.

JC: Happy to do it

ISJAC: Where are you at the moment, Los Angeles?

JC: Yes, I am in Los Angeles. I actually was born and raised here and finished school at Indiana University… hit the road for four years and then moved to Holland to be with my, then, girlfriend, now my wife, and played in a symphony orchestra for five years.1

ISJAC: You were with the Basie band before you went to Amsterdam?

JC: Yes. After I finished school I went on the road with Monty Alexander and Jeff Hamilton for two years. And I missed out on my dream to play with Duke Ellington – he died while I was still in college – and one of my other dreams was to play with Count Basie. I was studying with Ray Brown and I knew that Ray knew Count Basie very well. So I asked him if he could look into helping me get in touch with him. He said, “Sure” and the next day I was talking to Count Basie [laughter]. He called me and said, “Young man, I hear you would like to play in my orchestra.” and I said, “Yes, sir, Mr. Basie”. And he said, “Well, I’ll have my manager call you.” and it just so happened that his bass player was leaving in two weeks, so I let Monty Alexander know I had this opportunity and he gave me his blessing. I went with Count Basie and that’s where I really got bit by the writing bug. I’d never studied composition or arranging but I fell in love with that music being able to hear it every night there in real time. I knew how to transpose for instruments and I had some fantasies. So, I asked Mr. Basie if I could write some music, and he said, “sure”. I wrote something that was embarrassingly bad. [Laughter] I was frustrated, certainly, but I wasn’t put off and I wasn’t discouraged. That’s the best way to put it. So on one of my breaks I took the recording that Basie had done years before with Neal Hefti of a song called “Splanky.”2

ISJAC: Right.

JC: “Splanky” has an amazing shout chorus,3 and I got goose bumps every time we played it, so I wrote a sketch of everything that was happening in that arrangement. The intro, I wrote it in words…you know: piano – Ab pedal in the left hand, drums plays with sticks, bass playing the pedal. Roman numeral two: melody played in unison by the brass with mutes (and I didn’t know which so I wrote cups, buckets, question mark). Sort of walked through it in words like that, and then I went back and I transcribed as many of the notes that I could hear. From that, I noticed that when we got to the shout chorus I could hear on the recording that the lead trumpet note happened to be the same note that the lead trombone player was playing and the same note that the lead alto was playing so I had discovered this ‘triple lead’ concept of writing…

ISJAC: Yeah, I hear that from time to time in your writing…

JC: Yeah, and the thing that it provides is a lot of clarity for the melody. So I learned that whenever I want that kind of clarity I could use ‘triple lead’ or even ‘double lead’. Anyway, that was the beginning.

ISJAC: How much music did you write while you were with Basie? Were you producing an arrangement or composition once a week, once a month?

JC: It went from once a month or every three weeks or so…it was never once a week.

ISJAC: Yeah, that’s a lot!! [Laughter]

JC: I also acknowledged that I did not have the chops to write that fast. And, by the way, they paid me for the arrangements.

ISJAC: That’s great of course.

JC: It was kind of shocking that I wrote my first endeavour and I got paid for it. So that was great. And they not only paid for the chart, they paid for the copying too.

ISJAC: What a tremendous learning experience. To be inside a band like that, to be playing with the band, and hearing all those colours, and the orchestration. Everything is right there for you. As opposed to learning about those things from a purely theoretical standpoint.

JC: I absolutely agree.

ISJAC: Whenever I played saxophone in a big band, I would particularly notice what the trumpets and trombones were doing…. I mean I couldn’t avoid it…they were sitting right behind me [laughs]. But it is a truly amazing story that you started writing while you were in the Basie band!

JC: And, of course, the guys were very helpful. They had excellent writers in the band: Bobby Plater, Eric Dixon, and Dennis Wilson. Dennis was my homey because he was my age. He was a schooled writer because he studied at Berklee, and he would show me things about writing technically. And the other guys in the band would say things to me off the cuff that turned out to be invaluable – things that I think too many writers don’t know or don’t do. For instance, they’d see me working on a score, and that I was frustrated because we just played it and I’d be making some edits and corrections and they’d say, “Hey, what are you doing?” and I’d say, “Oh, this didn’t sound very good and I just want to change this or that”, and they’d say, “Well don’t change that! Just write another one! And the stuff you didn’t like in this one, don’t put it in the new one.”

ISJAC: Great advice.

JC: And that was so spontaneous on their part, but so deep for me and I followed their advice. With their encouragement, I kept writing and writing and writing. Another time, earlier on, one of the writers in the band was looking at a score of mine and he asked, “You write a ‘C’ score?” I replied [hesitating] “Yeah”, and asked me, “Well why?” and I said, “I don’t know” and then he said, “Don’t do that! Write a transposed score.” So I said, “OK” and that was that.

ISJAC: And is that what you do now?

JC: Yes. I write my sketches in C but then I always write transposed scores. Honestly, I’m at the point now where I have an assistant, so I usually write detailed sketches and use shorthand that she understands and can decipher. I’m in a lot of situations now where I have to write very quickly and so having an assistant is very helpful.

Incidentally, when I write a score, I don’t use notation software. I have Sibelius because I thought I should have it but I really don’t use it. I had Finale before that because I thought I might use it, but I have so many shortcuts that the software slows me down. It’s just the way I write.

ISJAC: I totally get that. It’s so much easier to write something on paper rather than have to look on page 135 of the manual to find out how to put something or other on the score for the first time.

JC: Yeah, and also, let’s say I’m writing a more extended piece. I sit at my piano and to my left is my desk and to the left of my desk, are two music stands. Now, I may need to refer to page 12, or 23 and 35 and, if I have to scroll on a computer, and have a couple of screens open, it really slows me down. But I do understand the importance of that technology and all my charts are computer-generated now and it is great to have those files. I do recognize the value of it. Its just that writing-wise, it’s just not the way I work.

ISJAC: And your assistant puts it into the software? Is that what happens?

JC: Yes. She copies them into the software. I’m not the kind of person who writes one line and says, “Here, make this sound like Thad Jones.” [Laughter]. I mean all the notes on the score are my notes.

ISJAC: You mentioned Thad Jones. He was in the Basie band long before you, right?

JC: Yes, long before.

ISJAC: Was he an influence on your writing?

JC: Huge. Yeah, Duke Ellington, Thad Jones, Quincy Jones, Billy Byers, Oliver Nelson and Henry Mancini. I got to work with him [Mancini] in my early days, so I really got to hear his treatment of orchestra and big band and big band with strings and all that. And – I’m sure I’m leaving somebody out – those are some of the people that really had an influence.

ISJAC: That’s a pretty heavy list. I read a story recently about Thad writing on the band bus. I think the story was in that book that came out last year, “50 Years at the Village Vanguard.”4 Do you know that book?

JC: Yes, I know about that. I don’t have that yet.

ISJAC: I haven’t read all of it yet, it’s pretty comprehensive, but at one point one of the members of the band noted that Thad would be writing a score while riding the band bus and that he was able to shut out everything. Just completely absorbed in what he was doing. Apparently the music was for whatever event they were heading to – a recording session or whatever it was. It takes such great concentration to be able to do that with so much going on around you. Really amazing.

JC: I think that’s something you learn to do, I mean, if you desire to do it, you figure it out. In fact, I got my chops together doing the exact same thing on the Basie bus. I would sit in the back of the bus and write my scores and then, when we got to the concert hall, or wherever we were going, I’d go to the piano to check things. You know, you do write a little differently when you write away from the piano. It’s not that you write more safely, it’s just that you write things that are a little more familiar to you. And so, yeah, I still write that way. At one point, I had a lesson with Johnny Mandel and he encouraged me to write that way because I played him one of the songs I had composed, and he said, “Mmm, did you write that at the piano?” And I thought about it for a moment, and I said, “Yes I did”, and he said, “Yup, sounds like it. You know people don’t sing chord changes, they sing melodies.” And so, whenever possible I try to write away from the piano. That was a major lesson for me. So to this day I write away from the piano and use the piano it to check what I’ve written.

ISJAC: Do you find yourself singing while you write?

JC: Yes. You know, the musicians have to have a chance to breathe when they play or sing what I’m writing.

ISJAC: I’m curious about something that I think every writer faces as they evolve, and that is developing good judgement or taste. You know, how much you decide to put here or put there. Or when there is enough of a particular idea and its time to move on. I guess I’m referring to the intuitive side of things. Finding rhythmic ideas that feel good, sound good and swing. Do you have any thoughts that would be helpful to students or up and coming composer/arrangers that you might want to share?

JC: I’m big on models. I find training wheels are a really good thing because we’ve all got ideas. We’ve all got fantasies. But if you are in the beginning stages of it, there’s a lot that you don’t know. And if you write from rules, it sounds like you are writing from rules. To free yourself from that you need to put your feet in the shoes of the masters – the people you are interested in and that have influenced you. When you put your feet in their shoes, you go well beyond the analytical level. You develop a feel for what they are doing. You develop a feel for the phrases and textures and for the apex of the phrase or the piece – and, of course, that’s really what you want. You don’t merely want to write from an analytical, left brain, point of view. You want to naturally flow the way that the music you enjoy listening to does.

I haven’t had that many composition/arranging students but sometimes I believe sincerely that they kind of don’t want to do what I say. And that’s fine…that’s cool…but if someone was studying with me, I’d would have them work on a three-tiered project. The first part would be to find a piece that they like, that’s close to their level. Don’t focus on a ‘level 25’ piece right now. Focus on something with an ‘11’ or ‘12’ level of complexity. They are going to have to work hard to get it right, but because it is close to their level it will be an attainable goal. So, for someone who is just starting out writing, I’m not going to send them to a later Thad chart or later Brookmeyer work. I’m going to send them instead to explore a piece they love. It might be Neal Hefti or early Quincy Jones or something like that where the textures are more at their level.

They would start by describing the piece in some detail using words – including describing the moods. Is it an exciting piece? Is it a romantic piece? What does the mood of this music say to you? Because that’s what we are ultimately doing as writers: we’re expressing ourselves and taking those moods that we want to express and attaching sounds to them. And they would have to describe the structure of the piece. For example, they would describe the intro, where the melody is, who is playing it, what the textures are…just in words. And then they would have to go back and, as best they can, transcribe the notes of the entire piece. There are some options here if the task is too difficult. It could be that they don’t transcribe the bass line, or only transcribe a sample of the piano voicings, or not transcribe exactly what the drummer is doing with all of his or her limbs. Then the work is not as daunting as it might seem at first.

So that’s the first tier or part of the project, and then the second tier would be that they would have to write their own piece based on what they just analyzed and transcribed. Of course they can change things, but they should respect the model they’ve just analyzed. So, instead of an 8 bar intro, they might write a 12 bar intro instead for the new piece. They should note things that were particularly noticeable in the piece they transcribed. For example, they might hear that the trumpets were in a certain register and so, in their piece they would write the trumpets in a similar register. It could be that the composer stuck to tensions like 13s and 9s and maybe just occasional alterations to a certain harmonic structure. Well, they should do the same thing. In other words, if you are going to write something in the style of Mozart, you probably shouldn’t use Ravel-like harmony.

And then, the third part of the project would be to write something that has nothing to do with the first two. You know, whatever you’re feeling – wherever your fantasies take you. So you don’t feel like you’re becoming a carbon copy of that other music.

And then I would have them go through that whole process three or four times. Then they would have a good 12 pieces that they have have really put their heart and soul into. Some of this is analysis based, and some of it is putting your feet in the shoes of another composer and imitating certain aspects of their writing. And then finally they do whatever they want to do.

Along with that advice I would address three things that I define as gaps in the skills composers or arrangers that I see today. Number one would be transposing. Become comfortable with writing transposed scores. I can’t tell you how many times, having been instructed by writers in the Basie band to do this has saved my bacon. I’ve been in so many recording situations or rehearsals when I’m standing in front of an orchestra and a hand goes up, the red light is on, and someone says, “John, can you tell me what my note is in the first bar of letter C?” I look and I see that they are playing French horn, and then I have to do an immediate vertical analysis of the score and figure out what that person’s note has to be changed to. Well, someone else could say that they never write a transposed score and still would be able to answer the French horn player’s question, but then, you don’t know what kind of situations you are going to be in and you may have to conduct someone else’s score and that score might be transposed.

Also, I think that the tendency nowadays in education is to allow students to prepare just enough to get through the gig; just enough to get through the recital; just enough to make it through the lesson; just enough to get through the concert and then move on to the next thing. And that’s kind of the nature of what happens in a lot of schools. But if you look at all the things that you feel good about having done, they reflect, I think, over-learning. You’ve done it so many times you don’t have to think about it. It feels really comfortable. But I think that it is too easy in some instances to be satisfied with doing an adequate job –accepting that that was your best effort and then moving on.

Luckily in my life I’ve had enough people who wouldn’t let me do that. You know, Ray Brown told me, (I can’t tell you how many times – maybe hundreds) – he would say to me, “Here’s what you got to do.” And then he would tell me whatever that was and I’d do it! I trusted him. And if I questioned his advice, I’d kind of put those questions aside for the time being. Often, it would take me a certain amount of time – sometimes years – to look back and say, “Oh, that’s why he had me do that!”

ISJAC: Ha! [Both laugh]

JC: So Ray Brown, and like I said, the guys in the Basie band would give me that kind of advice. Even Basie. At one time, I was really writing a lot and the band was playing more and more of my stuff, and I said to him, “Chief,” – we used to call him Chief, “ – would you ever consider allowing me to write an album for the band? It would be an honour for me and I would love to do it.” And he kind of looked at the ceiling and looked around and you know, like he wasn’t quite hearing me. So I sort of slithered out of the room and never brought it up again. Well, years later – because I know he heard me – I’d already left the band and I was living in Holland and I found some cassette tapes of some rehearsals and some things I’d done with band, and I’m listening to them and the light bulb went on. And I thought, oh my god, I wasn’t ready. He knew that I wasn’t ready and he allowed me to discover, at some point in life, that I wasn’t ready. He didn’t say ‘no’ to me and he didn’t say ‘yes’ either. He left it alone and that is one example of those lessons that Basie allowed me to learn.

ISJAC: What a wonderful lesson. I wanted to mention that I had occasion to play some of your charts many years ago while playing piano in a big band, I think in Vancouver, and there were several guest artists – one of them being Diana Krall. I expected her to play piano for her part of the concert and I started to get up and she said, “No, you play,” so I was in the, what I think was the unusual position of playing piano behind her. I think some of the charts might have been on the From this Moment On recording that you arranged for her. I can’t remember exactly. But one of the things I noticed while I was playing your music was the economy, that’s the word that comes to mind…there wasn’t a note out of place, and there wasn’t too much of anything. It was just right. Everything was clear and beautiful. And I haven’t forgotten that experience. It was a great lesson for me about writing music to accompany a singer, or any other writing for that matter.

JC: Wow, thank you!

ISJAC: It’s so easy to overwrite (I do it all the time!).

JC: Yes, it truly is. [Laughs]. You’re absolutely right and we learn that by…overwriting! There are no shortcuts, you know. Again, I’ve been so lucky that I’ve been around people that have encouraged me and been patient with me as I developed my writing skills. They saw how eager I was and how much I wanted to do it. Nobody said, “You’re going to have to figure this out on your own.” Or, “I don’t have time for you.” It was never that. And that helped me understand the familial relationship that we musicians have with each other, with this community that we are a part of. But the ‘economy’ thing… the older I get, the simpler I want to write. And the reason I want to write simpler is because I am striving for clarity. Even if I’m writing a piece that has a lot of information in it, and has a lot going on, I want there to be a lot of clarity in the textures and the complexities I’m involving myself in.

Here’s an example: I might have a two-fisted chord with 10 or 11 notes in it…oh I guess there would have to be 10, wouldn’t it? [Laughs] Or I guess it could have 11, but anyway, what I’ll do is play a crunchy, thick, dark chord, and I’ll just start lifting fingers and play the chord again with those fingers lifted and if I still get the effect that I’m going for, then I’ll lift another finger and I’ll think, can I eliminate that? And sometimes I think, no, I need that one, and I’ll put my finger back down.

When you write for a vocalist – and Bill Holman said this – it’s almost like taking candy from a baby. A lot of ‘givens’ are already in place. You already know the length of the piece, you already know the key, and you already know the tempo. You already know the time signature. You already know the melody. You know, there are so many givens and you remember the basic rules: enhance the mood and probably before that, don’t step on the singer. Then continue to do what you can to draw the ear toward the vocalist. So with all those parameters known, it makes it pretty easy to work with them and adapt them to your taste. Versus, if someone says, “I’d like you to write a composition for me – write whatever you want”. Now I have to come up with virtually everything. And even though we love doing that, it’s definitely going to take more time and thought and effort than doing an arrangement for a vocalist.

ISJAC: You encourage those who you are around because that is what others did for you. And with respect to that, I have a question related to your son, Gerald. I love his playing and everything he does.

JC: Thanks.

ISJAC: I have a daughter and when she was young I decided not to teach her. It was a difficult decision, but I thought it best to separate the dad part from the teacher part. As I was thinking about interviewing you, I thought I’d ask how you approached that with him as he was growing up. Did you teach him, or just encourage him, or…?

JC: Yeah, I think that it was more of the latter. My wife and I supported and encouraged, but we never pushed. And his older sisters, they are a year older than he is, and they both were taken to concerts and there was always music around. Actually, I didn’t have a stereo in the house but they heard a lot of music and knew what was going on. Once that I saw that Gerald was interested in going the music route, I just did my best, like most parents, to supply him with things that hopefully would help him move forward. So it was not only taking him to concerts, but also showing him a melody or showing him a chord that he was trying to figure out or, maybe just chiming in, but then stepping back and leaving him alone. I just didn’t want him to feel pressured. But then, often I’d be in the kitchen cooking dinner and Gerald would be in the other room practicing and he’d be playing a tune that I knew and I’d call out, “No, that’s an A-flat!” [Laughter]. So there’d be moments like that, but for the most part I was, as you say, more encouraging.

ISJAC: Thank you for sharing that. I suppose it was a bit of a departure, but I thought I’d ask you about that.

JC: How old is your daughter?

ISJAC: She turned 41 on New Year’s Eve. She was into music and played piano and flute, but ultimately she became a graphic designer and art director, which, interestingly enough, is what her grandmother did.