SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2019

VOLUME SEVEN NUMBER TWO

HOLLAND DOZIER HOLLAND

(L-R: Lamont Dozier, Eddie Holland, Brian Holland)

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

SHIRLEY SCOTT

(June 15-21)

FREDDIE HUBBARD

(June 22-28)

BILL WITHERS

(June 29- July 5)

OUTKAST

(July 6-12)

J. J. JOHNSON

(July 13-19)

JIMMY SMITH

(July 20-26)

JACKIE WILSON

(July 27-August 2)

LITTLE RICHARD

(August 3-9)

KENNY BARRON

(August 10-16)

KENNY BARRON

(August 10-16)

BUSTER WILLIAMS

(August 17-23)

MOS DEF

(August 24-30)

RUN-D.M.C

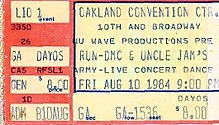

(August 31-September 6)Run-D.M.C.

1981-2002

Artist Biography by Stephen Thomas Erlewine

More than any other hip-hop group, Run-D.M.C.

are responsible for the sound and style of the music. As the first

hardcore rap outfit, the trio set the sound and style for the next

decade of rap. With their spare beats and excursions into heavy metal

samples, the trio were tougher and more menacing than their predecessors

Grandmaster Flash and Whodini. In the process, they opened the door for both the politicized rap of Public Enemy and Boogie Down Productions, as well as the hedonistic gangsta fantasies of N.W.A. At the same time, Run-D.M.C.

helped move rap from a singles-oriented genre to an album-oriented one

-- they were the first hip-hop artist to construct full-fledged albums,

not just collections with two singles and a bunch of filler. By the end

of the '80s, Run-D.M.C.

had been overtaken by the groups they had spawned, but they continued

to perform to a dedicated following well into the '90s.

All three members of Run-D.M.C.

were natives of the middle-class New York borough Hollis, Queens. Run

(born Joseph Simmons, November 14, 1964) was the brother of Russell Simmons, who formed the hip-hop management company Rush Productions in the early '80s; by the mid-'80s, Russell had formed the pioneering record label Def Jam with Rick Rubin. Russell encouraged his brother Joey and his friend Darryl McDaniels (born May 31, 1964) to form a rap duo. The pair of friends did just that, adopting the names Run and D.M.C., respectively. After they graduated from high school in 1982, the pair enlisted their friend Jason Mizell (born January 21, 1965) to scratch turntables; Mizell adopted the stage name Jam Master Jay.

In 1983, Run-D.M.C.

released their first single, "It's Like That"/"Sucker M.C.'s," on

Profile Records. The single sounded like no other rap at the time -- it

was spare, blunt, and skillful, with hard beats and powerful, literate,

daring vocals, where Run and D.M.C.'s

vocals overlapped, as they finished each other's lines. It was the

first "new school" hip-hop recording. "It's Like That" became a Top 20

R&B hit, as did the group's second single, "Hard Times"/"Jam Master

Jay." Two other hit R&B singles followed in early 1984 -- "Rock Box"

and "30 Days" -- before the group's eponymous debut appeared.

By the time of their second album, 1985's King of Rock, Run-D.M.C. had become the most popular and influential rappers in America, already spawning a number of imitators. As the King of Rock

title suggests, the group were breaking down the barriers between rock

& roll and rap, rapping over heavy metal records and thick, dense

drum loops. Besides releasing the King of Rock

album and scoring the R&B hits "King of Rock," "You Talk Too Much,"

and "Can You Rock It Like This" in 1985, the group also appeared in the

rap movie Krush Groove, which also featured Kurtis Blow, the Beastie Boys, and the Fat Boys.

Run-D.M.C.'s fusion of rock and rap broke into the mainstream with their third album, 1986's Raising Hell.

The album was preceded by the Top Ten R&B single "My Adidas," which

set the stage for the group's biggest hit single, a cover of Aerosmith's "Walk This Way." Recorded with Aerosmith's Steven Tyler and Joe Perry,

"Walk This Way" was the first hip-hop record to appeal to both rockers

and rappers, as evidenced by its peak position of number four on the pop

charts. In the wake of the success of "Walk This Way," Raising Hell became the first rap album to reach number one on the R&B charts, to chart in the pop Top Ten, and to go platinum, and Run-D.M.C. were the first rap act to received airplay on MTV -- they were the first rappers to cross over into the pop mainstream. Raising Hell also spawned the hit singles "You Be Illin'" and "It's Tricky."

Run-D.M.C. spent most of 1987 recording Tougher Than Leather, their follow-up to Raising Hell. Tougher Than Leather was accompanied by a movie of the same name. Starring Run-D.M.C., the film was an affectionate parody of '70s blaxploitation films. Although Run-D.M.C. had been at the height of their popularity when they were recording and filming Tougher Than Leather,

by the time the project was released, the rap world had changed. Most

of the hip-hop audience wanted to hear hardcore political rappers like Public Enemy, not crossover artists like Run-D.M.C. Consequently, the film bombed and the album only went platinum, failing to spawn any significant hit singles.

Two years after Tougher Than Leather, Run-D.M.C. returned with Back From Hell, which became their first album not to go platinum. Following its release, both Run and D.M.C. suffered personal problems as McDaniels suffered a bout of alcoholism and Simmons was accused of rape. After McDaniels

sobered up and the charges against Simmons were dismissed, both of the

rappers became born-again Christians, touting their religious conversion

on the 1993 album Down With the King. Featuring guest appearances and production assistance from artists as diverse as Public Enemy, EPMD, Naughty by Nature, A Tribe Called Quest, Neneh Cherry, Pete Rock, and KRS-One, Down With the King became the comeback Run-D.M.C.

needed. The title track became a Top Ten R&B hit and the album went

gold, peaking at number 21. Although they were no longer hip-hop

innovators, the success of Down With the King proved that Run-D.M.C. were still respected pioneers.

After a long studio hiatus, the trio returned in early 2000 with Crown Royal. The album did little to add to their ailing record sales, but the following promotional efforts saw them join Aerosmith and Kid Rock for a blockbuster performance on MTV. By 2002, the release of two greatest-hits albums prompted a tour with Aerosmith

that saw them travel the U.S., always performing "Walk This Way" to

transition between their sets. Sadly, only weeks after the end of the

tour, Jam Master Jay

was senselessly murdered in a studio session in Queens. Only 37 years

old, the news of his passing spread quick and hip-hop luminaries like Big Daddy Kane and Funkmaster Flex

took the time to pay tribute to him on New York radio stations.

Possibly the most visible DJ in the history of hip-hop, his death was

truly the end of an era and unfortunately perpetuated the cycle of

violence that has haunted the genre since the late '80s.

STREET-SMART RAPPING IS INNOVATIVE ART FORM

by Robert Palmer

See the article in its original context from

February 4, 1985, Section C, Page 1

February 4, 1985, Section C, Page 1

Two

years ago, Joseph Simmons was sitting in class at La Guardia Community

College in Queens, jotting rhymes and observations in his notebook to

pass the time. ''One thing I know is that life is short,'' he wrote -

hardly a surprising observation, since the class was in mortuary

science. ''The next time someone's teaching, why don't you get taught,'' he continued, and then added, almost as an afterthought, ''It's like that.''

After

school he showed his rhymes to Darryl McDaniels, a friend he had grown

up with in Hollis, Queens. ''It's like that,'' Mr. McDaniels repeated,

and then added, ''and that's the way it is !'' The afterthought had

become a catch phrase.

The two friends

were chanting their rhymes at each other on the streets of their

neighborhood the same day. Within a few weeks, they were calling

themselves Run-D.M.C. and had recorded ''It's Like That'' for the

independent Profile label with the help of Mr. Simmons' brother Russell,

an associate of the early rap star Kurtis Blow. ''It's Like That'' was

soon a hit, and their first album, simply titled ''Run-D.M.C.,'' went on

to sell more than 500,000 copies, becoming the first rap album to earn a

gold record late in 1984. The album included ''It's Like That'' and a

newer rap, ''Rock Box,'' with Jimi Hendrix-style rock guitar added to

the sparse rap sound of two voices, drum machine and a smattering of

electronic effects.

On their new

Profile album, ''King of Rock,'' D.J. Run (Mr. Simmons) and D.M.C. (Mr.

McDaniels), along with their accompanying disk jockey, Jam Master Jay,

and the guitarist from ''Rock Box,'' Eddie Martinez, have forged a

powerful and impressively varied set of musical performances from the

basics of rap, the New York street music that first developed around the

same time as break dancing, in the late 1970's.

Broadening the Raps

Watchers

of pop music have been touting rap as a current trend, and predicting

its rapid demise, since the first rap hit, the Sugarhill Gang's

''Rapper's Delight'' in 1979. There did not seem to be much future for

an idiom that consisted of two or more M.C.'s shouting catch phrases and

boasts at one another while a disk jockey accompanied them by playing

back and repeating parts of records on two turntables.

But

rap has confounded the doubters. M.C.'s have broadened their raps by

making up rhymes on war and poverty, living conditions and cultural

issues, while continuing to toast their own prowess at rapping and

romance in the tradition of earlier black blues, rhythm-and-blues, and

soul. The disk jockeys have become virtuoso improvisers, using

''scratching'' (moving a record back and forth on a turntable by hand),

and other collagist techniques to build fresh musical structures from

bits and pieces of existing records, ''found-object'' tape recordings,

and other sound sources. Films about rapping (''Wild Style'' and ''Beat

Street'') have come and gone, but the music has survived being a fad and

continues to grow.

When rapping and

the creative techniques of the disk jockey are combined effectively, as

they are on ''It's Not Funny,'' ''Jam-Master Jammin','' and other

selections from Run-D.M.C.'s ''King of Rock'' album, the result has as

much musicality and richness as any other brand of popular or

improvisational music. Rap, or hip-hop as the overall musical idiom is

often called, has become an art form that is consistently enlivened by

innovations and infusions of new talent, a form that is winning a

national and international audience while retaining strong ties to the

rhythms and lore of New York's streets. And rap has brought a measure of

financial stability to several low-overhead independent record

companies, despite the domination of the pop record business by a

handful of corporate conglomerates.

Run-D.M.C.

recently headlined a package tour that featured a variety of hip-hop

artists and was sponsored by a watch manufacturer: the Swatch Watch New

York City Fresh Fest. The show, which also included hot new performers

like Whodini and UTFO (UnTouchable FOrce), played to arena crowds of

15,000 to 20,000 in Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit and other cities.

''We'd ask them to scream and they'd all scream,'' D.J. Run reported.

'A Cross-Racial Audience'

''Even

in cities like Chicago, where no rap music is played on the radio, the

show attracted 15,000 people, which is some indication of rap's

underground appeal,'' said Run- D.M.C.'s manager, a former rock critic

named Bill Adler. ''At this point, the audience is predominately black

teen-agers, but we also drew crowds in some Midwestern cities where

there isn't a large black population. The rap industry now is a lot like

black rhythm-and-blues just before it was discovered by the mass

audience, in the 50's. The major radio programmers and record labels are

trying to ignore that, but it's building a strong cross-racial audience

anyway.''

Hip-hop

is now an international phenomenon. One of the most popular new rap

groups, Whodini, was put together in Brooklyn but records in Britain,

where the pop star Thomas Dolby took an active interest in its work.

Whodini had won a large and loyal following in Britain and on the

European continent before it began to attract a substantial audience on

the fiercely competitive New York hip- hop scene. But Whodini's second

album, ''Escape'' (on the Jive/ Arista label), went gold soon after

''Run-D.M.C.'' and Whodini dance singles like ''Five Minutes of Funk''

and ''Freaks Come Out at Night'' are now heard almost constantly in New

York dance clubs, as well as on local urban-contemporary radio stations.

Another

current rap hit, UTFO's ''Roxanne, Roxanne,'' reportedly sold more than

150,000 copies in its first three weeks of release, and has been heard

on at least one local top-40 radio station. Like the Force M.D.'s, who

have recorded several hits on the Tommy Boy label, the members of UTFO

sing as well as rap, and they are first-rate dancers as well. This

versatility could be a key factor in establishing rap with a wider

audience.

Ironically, rap groups that

have been as successful as Run-D.M.C. or Whodini are currently having

trouble finding suitable places to perform in their hometown. They feel

they have outgrown the Roxy and smaller clubs, but despite the

cross-country success of the Swatch tour in arenas the size of Madison

Square Garden, the Garden itself has yet to present a comparable rap

show. ''We're ready for the Garden,'' say Run-D.M.C. members, and though

the rap groups lack the major record-label clout of other Garden-scale

performers, one suspects their emergence into upper- echelon pop

circuits is only a matter of time.

A version of this article appears in print on , Section C, Page 13 of the National edition with the headline: STREET-SMART RAPPING IS INNOVATIVE ART FORM. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper

Run-D.M.C. Is Beating the Rap

Three kids from Queens are ‘Raising Hell’ at their shows. Run-D.M.C. set the record straight on rap music and violence

Run-D.M.C. on the cover of Rolling Stone.

Moshe Brakha

December 4, 1986

Rolling Stone

Run (Joe Simmons), D.M.C. (Darryl McDaniels, also known as D) and Jam Master Jay (Jason Mizell) — the trio that has recently injected rap into the American mainstream with its double-platinum album Raising Hell – are blasting the white-gloved Jackson and other glitzy pop stars

Kids can look up to us,” yells Run, so named because of his motor mouth. “We don’t do any dumb shit.”

“We don’t paint our faces neither,” says Jay, 21.

Run, 22, who is careful to distance his group from Boy George and “homo-assed drug takers,” says, “Michael wants us to make a record with him, and we don’t really want to make a record with Michael. We really dig Barry White.” The rappers have discussed collaborating with White, the rotund soul man who had a string of sexy hits in the Seventies.

“Michael’s not really us,” says Jay.

“He doesn’t fit the program,” says Darryl, 22. “Michael? If I met Michael Jackson and he had that thing on his face [Jackson’s famed surgical mask], I’d rip it off. I’ve got no germs, man.”

“Michael doesn’t feel the way I feel,” snaps Run, a native of Hollis, a middle-class neighborhood in Queens, New York. “He wants us on his next album. He wants to make a record about crack. We have good rhymes about it because we still see it, we live in the neighborhood still. I’ve made a lot of money, but I still live in Hollis. It’s so funny. I don’t have a big mansion and beautiful clothes. I see the crack on the corner. I need to get rid of this thing. Michael probably would like me to lay some of this on his album. Michael writes lyrics, but I write what I think. I see and feel all day.”

While their remarks have the same uncompromising grittiness as their music, the tension behind their words reveals that Run-D.M.C. is now at a crossroads. Having broken through to white radio with “Walk This Way,” its collaboration with the hard-rock group Aerosmith, Run-D.M.C. must decide how to be pop and streetwise at the same time. Run-D.M.C. also faces another crisis. As its fame has increased, the trio has consistently been associated with violence. A riot between two youth gangs at the Long Beach Arena last August left forty-two people injured. It was the fifth time this past summer that a Run-D.M.C. concert led to mass arrests or serious injuries. Bloody incidents also plagued some theaters showing Krush Groove, the 1985 film in which the group appeared, leading Parents’ Music Resource Center spokeswoman Tipper Gore to claim that rappers tell fans, “It’s all right to beat people up.” While promoters have canceled Run-D.M.C. shows or added to the hysteria with talk of hiring extra security guards for concerts, more dispassionate observers have suggested that the group is getting a bum rap.

Yet the image has stuck. To much of white America, rap means mayhem and bloodletting.

So as Run leaves his penthouse suite to collect a rented black Corvette at the hotel’s carport, he looks concerned. He insists that he, D and Jay have come to Los Angeles to promote a truce among warring “gang-bangers,” not simply to clean up their image. As Run explains, the group will take phone calls at KDAY, a local radio station, “just so a small beginning can be made to stop gangs, stop drugs. If only one kid turns away from gangs or drugs, we’ve been successful.”

That squeaky-clean image is reinforced outside the hotel when Run encounters a black deputy marshal from the L.A. municipal court. Moving through a group of well-dressed businesswomen to shake Run’s hand, the marshal says, “Boy, is my son a fan of yours! All because of you he wants to be a DJ. I just bought him a mixer.”

“That’s how I started out. DJing and playing basketball,” Run coos boyishly, staring at the man’s shiny badge and gun. “Give your son the word: DJing is good, it’s def. Tell your son you were hanging out with me.”

“I will, I will,” the marshal says. “My son will go wild about this.”

Run’s smile broadens once his car arrives. Instead of renting a large silver or gold Mercedes like other members of the Run-D.M.C. entourage, Run prefers the sportier feel of a Corvette. As he dials his wife, Valerie, and his three-year-old daughter, Vanessa, on the car’s cellular phone, he says, “I’m a real family man now. I even took them to Europe this summer, and we had a ball. I’m the kind of guy who gets lonely after a show and takes a flight home.”

Run chats with Valerie for ten minutes, learning that his daughter spent the day at Belmont Racetrack. He promises to call again later that evening, and that reminds him about Michael Jackson’s dinner invitation.

Run knows that it’s one thing to scratch, rhyme and scat over Aerosmith’s tune, but it’s a different move to cross into Jackson’s pasteurized pop world. He burrows deeper in the comfy front seat and sighs. “I have to go for a ride to clear the bees out of my head. Later I’ll get in the Jacuzzi – that way I can get my brain together. I have to decide if I want to hang out with Michael. I just don’t know. I.”

Run’s last words are lost in a loud vroooom as he puts his foot to the gas and screeches out of the carport.

Run-D.M.C.’s Raps Echo the Sounds of the City, capturing the aggressive boasts and frustrated threats of street-toughened youths. The group’s debut album, Run-DM.C. was a bravado-filled jaunt on which Run urgently bragged that he was “the coolest and the baddest.” Run-D.M.C. was the first rap album to go gold and the first to have a song featured on MTV. The follow-up LP. King of Rock, was similarly boastful but less stark, as the group drifted into entertaining musicality, adding some reggae riffs and hard-rock guitar.

Raising Hell, the record that’s catapulted Run-D.M.C. into the realm of appearances on Saturday Night Live and The Late Show Starring Joan Rivers (they rapped with Rivers), teems with raw messages about the streets, drugs and promiscuity. The huge success of the album – it’s the first rap LP to go platinum – and the “Walk This Way” single has caused Run-D.M.C. to soar far beyond hip-hop. With sales of Raising Hell now well over 2 million, Run-D.M.C. has more than mainstream credibility. It is now one of the hottest groups in America.

And although their defiant, socially urgent anthems certainly speak to inner-city youths, Run, D and Jay are hardly products of Watts or Harlem. Friends since childhood, all three grew up in Hollis, a neighborhood of one-family homes and well-tended gardens. Both of Run’s parents worked, holding down respectable jobs with the city. So little Joey played basketball, listened to his Stevie Wonder and Barry White records and otherwise led a genteel life.

Still the doting son, Run is quick to pay homage to his father, Daniel Simmons, a New York Board of Education employee who inspired him to write poetry at age ten. “My father is a great person,” says Run, sounding like a true product of the middle class. “My mother and my father made sure I was never deprived of anything.

“The worst thing that ever happened to me as a kid was that gym class would run out of time. I couldn’t play my basketball game. Oh yeah, I couldn’t bring my box to school neither. But that’s it. No way was I brainwashed or hurt by being black . . . It’s not like I never had any money. I’ve always had money.”

By the time Joey became a teenager, the staccato, thumping beats of rap were beginning to replace disco in black nightclubs nationwide. Acts like Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five made Sugarhill Records the king of the ghetto blaster. Run’s brother Russell, whose life story is depicted in Krush Groove, was also starting to make noise. Establishing Rush Productions, he began to book rappers into his college, and it was under his aegis that Curtis Walker became Kurtis Blow, the early rap superstar responsible for the smash hit “The Breaks.” Blow would often sleep over at the Simmonses’. “I knew my brother and Kurt were having a great time,” says Run. “I wanted to be with them.”

So Joey started scratching over records, modeling his style after Blow’s. Soon Joey’s DJ’ing was so inspired that he toured along with his mentor, billed as “The Son of Kurtis Blow.”

Joey played tapes of his appearances with Kurtis Blow shows for Darryl, a friend at St. Pascal Baylon, a Catholic elementary school in Queens. A comic-book aficionado, Darryl gave up drawing Spiderman and Captain America to start rapping with Joey. The pair didn’t team up officially with Jay, an old basketball friend of Joey’s, until after they’d graduated from high school. Their first single, “It’s Like That/Sucker M.C.’s,” coproduced by Russell, became a hit in 1983, as did their next release, “Hard Times/Jam-Master Jay.” Rap music, which had seemingly peaked in popularity, suddenly rebounded. And Joey Simmons, eager to become rap’s most recognizable star, decided to make a final commitment to the genre. He gave up studying mortuary science at LaGuardia Community College for a life on the run.

I knew there was going to be trouble, there had to be,” says Chino, a gang member, recounting how violence erupted at the Long Beach Arena last August 17th between his gang, the Bloods, and their rivals, the Crips. “We were just sitting there, listening to LL Cool J [one of the opening acts], and these Crips started to show their colors under their jackets. That wasn’t right, man. Then they started snatching gold chains and breaking chairs, you know, to use the legs as clubs. We had to do the same shit.”

As Run-D.M.C. looked on from backstage, club-wielding policemen swept through the packed 14,500-seat arena, and over the next three hours fights raged in and out of the hall. Run-D.M.C. never made it to the stage.

“It was crazy,” says another member of the Bloods, eighteen-year-old Mafia Dick. “Everybody was messing with everybody. We don’t get along outside, so we’re not going to get along inside. Some go to get a kick out of Run-D.M.C.’s music, but most of the guys just go there to fight. I did. We knew other gang bangers would be there. Run’s music is up-to-date. We like their rhymin’. It’s hip, it says something to me, and I like their clothes – it’s B-boy style to the highest degree. So gangs want to see them, and when you put all these groups together, you’re lookin’ for trouble.”

That view is supported by Steve Young and Lloyd Smith, two Inglewood detectives, both of whom are veteran observers of the gang lifestyle and its deadly eruptions of machismo. They have little patience for liberal-toned explanations of violence. To them, all gang strife is to be condemned and swiftly punished. And yet, as they sit in an office strewn with photos of gang members, they take a far different stance from the usual Run-D.M.C. headlines.

“It could’ve been a dog or pony show at the arena, the violence would’ve still broken out,” says Young. “Run-D.M.C. gets a bad rap because of the crowds they draw. There are long-held grudges between these gangs, and when they converge in one place, the paybacks will come. Sure, Run-D.M.C.’s music touches a nerve, and the raps are all street, but even if Reagan was speaking, there’d have been bloodshed.”

The legacy of Long Beach – and the reverberations from other incidents this past summer in Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Atlanta, Cincinnati and New York – is not yet forgotten. For many, Run-D.M.C.’s name is now synonymous with rioting crowds, wailing ambulances and wholesale arrests. Newspaper editorials have blamed the group’s driving lyrics for drawing crowds “bent on havoc.” Jittery politicians have tried to ban the group from playing in various cities. Dates in L.A. and Providence, Rhode Island, were canceled, and after a Run-D.M.C. appearance at an L.A. street fair was scrubbed in September, Deputy Mayor Tom Houston proclaimed, “I’ll be damned if we’ll have them.”

For Run, however, the most hurting blast came from Kurtis Blow. In several interviews, Run’s former mentor rebuked him for laying down raps that might encourage violence. Run is still smarting from the charge. Attributing Blow’s outburst to jealousy, Run bristles. “Kurt tried to ruin us,” he says. “He’s so jealous. He never had a gold album in his life. He’s disgusting.”

Run also dismisses criticism from the media and politicians, boasting, in typically grand fashion, “They say we’re putting out bad messages to the kids. All – you hear? – all our messages are good . . . Our image is clean, man. Kids beat each other’s heads every day. They are fighting because they were fighting before I was born. I’m no sociologist, but we’re role models, man, big-time role models . . . I get bigger and bigger, and I don’t care what people think.”

Considering some of the press his group has received recently, it’s not very surprising that Run seems defensive, even nervous, about talking with reporters. At a morning press conference to discuss the next day’s KDAY event, he looks away as we shake hands, and he bitterly asks, “What type of article is this going to be, anyway?” Further irritated by the photographers buzzing around him, he snaps, “I talk from the heart, but no matter what I try to say, people always dis [criticize] us. They sensationalize everything . . . They have to stereotype us.”

His temper cools once the conference begins. Wearing green pants, a matching work shirt, characteristically unlaced white Adidas low tops and a porkpie hat, he grins at the TV cameras as Barry White compliments the group for its social concern. After various community activists pay their own tributes to Run-D.M.C, White describes the L.A. gang problem – 268 gang killings last year – as “the coming Armageddon at your front door.”

White’s intensity brings a look of anguish to Jay’s face. Run nervously fondles a miniature gold sneaker dangling from his neck and tells the crowd, “Life is hard enough without drugs or joining gangs. We have great positive messages for kids. We’re in touch with all the kids. They’ll listen to us before they’ll listen to their teachers or mothers and fathers. We’re cooler than them as far as the kids are concerned, and being cool is staying in school.”

The follow-up questioning is rather timid. Only one reporter challenges Run’s sincerity, suggesting the group’s L.A. visit was a necessary act of public relations after the Long Beach riot. Dismissing that implication, Run reiterates the group’s positive message. “We offer kids alternatives. We tell them they can go play ball, go to school. There are lots of other things you can do besides taking drugs or joining gangs . . . We’re positive.”

The conference unceremoniously ends on that note, and in keeping with their pure-boy image, America’s hottest rappers want to go to a national landmark for lunch: McDonald’s.

Run-D.M.C.’s common-man approach to dining is also in sync with other aspects of their lives. All three guys continue to live in Hollis, either in houses they grew up in or close by. Run insists that the trappings of success – platinum and gold albums, offers from Adidas and Technics to do commercials, a forthcoming line of B-boy clothes – haven’t spoiled them. “Move?” Run says. “What for? Beverly Hills? That’s corny and fake, man. If Michael Jackson is happy out here, more power to him. I just need two dollars in my pocket and a basketball game.”

Unlike Jay and D.M.C., who stud their fingers with diamond rings, Run wears little jewelry. “I don’t want money,” he says. “I’ve made money. Right now I don’t need ten cars, but I have enough money for fifty cars. I don’t want anything. I’m so happy. I look at my daughter sleeping. I kiss her while she’s asleep. I sit with a pen and see if I can write something. If not, I go shine up my ’66 Oldsmobile [he also has an ’86 Riviera], gas it up and drive my wife to work. She works at a doctor’s office. Then I go call Jay.”

Run punctuates that self-portrait with a rhyme: “People always saying/’Yo, Run, you made a killing/Where’s your car, where’s your gold?’/Yo, man, I’m just chilling/I’m not rhyming for the money/This is straight from the heart/People think my car is funny/But I get it to start.”

But now that Run-D.M.C. hats and T-shirts have supplanted Michael Jackson items in American households, Run is not your ordinary two-cheeseburger man at McDonald’s. Even before he could ride to the Golden Arches in the group’s gold Mercedes and before he had a troop of P.R. agents to pamper him, he never knew the crippling destitution of many black lives. So how can he really talk to a fourteen-year-old who sees selling drugs as the only way out of the ghetto? This philosophical discussion with Run must be shelved; he doesn’t want any company during the group’s jaunt to McDonald’s. When he finally appears back at the hotel, he gives me a long, hard stare. He sits sullenly near a window, twirling his hat and staring at the bleak airport environs.

Jay said earlier, “I don’t think nobody’s after me; I forgive those reporters who fucked us.” Now he takes the lead. “Bad lyrics? Bullshit! We’re not talking about laying the girl down or doing this drug. . . We’re the only people who can talk to kids. Besides Bruce Springsteen, Born in the U.S.A., I haven’t heard a decent record.”

Yeah, I love Bruce Springsteen,” Run quickly interjects. “Like us, he has a positive message. We’re gonna sell as much as him, if not more, ’cause we feel the same way. I hang with Bruce. I know him. I did a record with Bruce Springsteen, we made ‘Sun City’ because we would never play there [in South Africa] . . . I’m making lots of money now. I’m going to go over there with suitcases filled with money and build things . . . We’re also going to open drug rehabilitation centers. I’m not going to call them the Run-D.M.C. House, I’ll just open them.”

“Yeah, we’re bigger and better than any bullshit bands,” yells D. The usually quiet, six-foot-plus McDaniels takes off his thick, black-rimmed shades and continues. “The reason why they are listening to us is because we are the Michael Jackson of now. Prince was it when Purple Rain came out. But we are what’s going on right now. We are the music. We are what’s hot.”

“We are the world, we are the children,” sings Run. Jerking himself up in his chair, he says he doesn’t want to be known as the man who ended crack in America. “But, oh, my God,” he says, “my mission is so big. We just left New York. We did a big thing with Mayor Koch, Cuomo [an anticrack rally for New York City schoolchildren], and the kids didn’t care about them. We came onstage, and we all did it . . . Kids listened.

“I’d just like to ask Tipper Gore if she ever listened to my records,” continues Run. Then he launches into the autobiographical “Here We Go” rap: “Cool chief rocker, I don’t drink vodka/I keep a microphone inside my locker/Go to school every day/On the side make them pay/The things I do make me a star/And you can be too if you know who you are/Just put your mind to it, you’ll go real far/Like the pedal to the metal when you’re driving a car.”

Grimacing and disgustedly shaking his head, Run expands on this beat to talk about the Aerosmith collaboration. “Nag, nag, nag, everybody is nagging me because of ‘Walk This Way.’ Everyone’s talking about crossovers. ‘Hey, son, didn’t you do this to get more radio play?’ . . . I hope nobody wants to talk to me next year. I’m ready for a flop. You know why? If everybody is nagging me about ‘Walk This Way,’ they can get my dick head.” Run bangs his fist on the table before continuing. “You know why? Because I made that record because I used to rap over it when I was twelve. There were lots of hip-hoppers rapping over rock when I was a kid. Now I made it and everyone wants to nag me. As for my trying to get more radio play, I’ll never . . . I always say what I feel.”

Run doesn’t advise other rappers to move into rock, saying, “You have to do what’s real. It’s like how my ideas come to me, naturally. That’s how I came up with the idea for ‘My Adidas.’ I thought one day of all the incredible things I’ve done with these sneakers on. Live Aid and all the concerts.”

Talk then turns to the group’s next movie. Run wants Tougher Than Leather, which is about to go into production, to be more “real” than Krush Groove. “Krush Groove was nothing but a Walt Disney movie,” Run says. “The Fat Boys [another rap group that appeared in the film] were just being funny, and I didn’t do nothing. This next one is going to be action filled, a real mystery.”

All three guys start screaming at once. Jay keeps saying, “Leather‘s going to be much more violent, a lot more violent.” And this prompts D to chime in: “That’s right, it’s gonna be like a good John Wayne flick. The violence is there, but you don’t mind if the good guys are doing it.”

Run says that the film will revolve around the group’s search for the killers of their beloved real-life roadie, Runny Ray. Since the murderers plant drugs on Ray, the cops view the case as “just another dead nigger.” So the boys must become detective-avengers, or a cross between Eddie Murphy in 48 HRS. and Sylvester Stallone in Rambo.

Run says it will be “the best movie in the world. At the end, we’re all heroes. You’re happy we’re kicking their butts. It has to be violent because it has to be violent. Sometimes violence is needed.”

Playing the diplomat, Jay insists, “We don’t promote violence to the kids.” As for the violence at the Long Beach concert, he says, “I wanted to bang some bangers’ heads out there. Whoever I see fucking up in my concert, I want to be the big motherfucking Bruce Lee and kick the gang’s ass, throw them all in fucking jail and do my concert.”

“We’re positive,” says Run. “We’ve played so many beautiful gigs. We’re not a threat. I want to be happy every day. I’m fighting to help things . . . I’ve got a movement of happiness. We are not thugs. We don’t use drugs. People try to stereotype us . . . “

“Yeah, we look like young black kids that are going to rob you,” says Darryl, laughing.

But they all say that it wouldn’t be happening if they were a white band. “Some people just want to stop rap,” says Run. “The politicians blame it on us. Other people are hoping we’ll mess up . . . But we’re investing our money wisely, we have good accountants, and the three of us are so close we think the same. We’re not gonna do anything to hurt ourselves, nothing.”

Russell Simmons is worried – not about the public-relations problem caused by violence at Run-D.M.C.’s shows but about the group’s current do-good attitude. The cochairman of Def Jam Recordings and the manager of Whodini, the Beastie Boys and Run-D.M.C, Simmons worries that the group is becoming too “straight,” that its edge will be dulled by too many anticrack, antigang campaigns. He wants to make them “harder” but is worried that Run is on a “mission” that could undermine their commercial clout. “I look at them and say, ‘Stop being a pussy.’ But Joey really thinks he owes these kids something. This crack thing is a serious concern . . . Let’s hope a year from now people don’t think they’re suckers.”

Simmons admits that he sees how his little brother’s lyrics could lead to antisocial behavior. Still, he calls his brother’s group “one of the most positive teenage bands there is. These lyrics are done with kids in mind that should be able to understand them. If they can’t, that’s not even a tragedy . . . The guys sing about staying in school, going to church, respecting your mother, don’t take drugs . . . They’re positive; that’s the bottom line.”

But Russell Simmons feels the “preachy” lecturing of the group’s civic-minded projects, like the Jackson collaboration, will sabotage Run’s promise of “not doing anything to hurt ourselves.”

“This preaching scares me,” he says. “It gets on people’s nerves . . . They [Run-D.M.C.] spend so much time wanting to do shit like this Michael Jackson thing . . . I said, ‘Yeah, but fuck that. You have a career to worry about.’ The idea of Michael and Run is kinda soft . . . This is something that’s certainly not going to make Run-D.M.C. bigger or better; it could kill them. It could kill their careers in front of their first audience.”

Kday has called its call-in show Day of Peace, but outside the studio, dozens of husky security guards expect trouble. It’s rumored the Rollin’ Sixties branch of the Crips gang will disrupt Run-D.M.C.’s appearance. And when a youth in a passing car shouts, “Those Bloods shot my momma and brother,” a nervous worker at the event says, “This whole thing is a farce. Kids with Uzis and sawed-off shotguns are not going to stop their shit because of a radio program.”

Exuding far more optimism, Barry White arrives in an ivory Rolls, and once again he effusively praises Run-D.M.C. The hefty, stringy-haired White has lost a brother in the gang wars, but he’s upbeat today. “This day’s a beginning,” he says. “We can put a stop to drugs and gangs . . . The young people, blacks, white, Hispanic, all colors, love Run-D.M.C. They have reached the nerve of the people through their young grooves, their rapping genius.”

Excited by the prospect of doing an antidrug song with Run-D.M.C., White gives each of the three a bear hug upon their arrival. But as the boys enter the studio, they all but forget White. Now the talk is only of Michael Jackson.

“He’s the best man in the world,” says Run, making sure the depth of his new feelings is understood. “He’s an incredible human being. We ate soul food at Michael’s studio last night, and it seemed like he was in touch with God. He’s so calm, so content, and I’m going to go into the studio to do a tape with him. It’ll be an anticrack song. The guy who did Mean Streets and Taxi Driver [director Martin Scorsese] is going to make the video. The whole thing was just great. Michael kept asking me, about rap. I asked him about record sales. And when the fried chicken came, I knew he was cool.”

Smiling beatifically as a KDAY worker adjusts his headset, Run keeps raving about Michael. “He’s just a normal, nice man. He’s just as D described him. Have you ever seen Bambi? Well, he’s just like that. If he went outside and saw a flower, he’d probably say, “That’s beautiful.’ People say he’s gay and stuff. I don’t believe that . . . In the middle of the evening I was just thinking, ‘Gee, I’m sitting next to Michael Jackson, a superstar,’ and then I realized he’s just normal, sitting there eating his rice and playing with my gold sneaker.”

This story is from the December 4th, 1986 issue of Rolling Stone.

ROCK AND ROLL HALL OF FAME

Run-D.M.C.

INDUCTED: 2009

Category: Performers

Members:

- Darryl “DMC” McDaniels

- Jason “Jam Master Jay” Mizell

- Joseph “Rev Run” Simmons

Run DMC was a group of firsts.

First rappers on MTV, first rappers on Saturday Night Live, first rappers on the cover of Rolling Stone, first rappers to win a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. They broke down barriers for future rap acts, crossed boundaries between rap and rock and dispelled old notions of what rap could be.

Biography

Run DMC exploded out of Hollis, Queens in 1983, changing the sound of rap music, street fashion and popular culture in general.

Their approach was stripped-down and spare, and they innovated by rapping over rock beats, even incorporating hard-rock guitar samples on occasion. Most important they stayed true to the realities of the street. Their first release, the 12-inch single “It’s Like That”/”Sucker MCs” inaugurated a revolution in rap. Released on Profile Records and produced by Kurtis Blow, it was the first rap single with a hard beat and stripped-down, no-nonsense delivery.

Run DMC gave rap both its first gold album (Run-D.M.C., 1984) and its first platinum album (King of Rock, 1985). They also took rap into the Top Ten when they collaborated with Aerosmith on a rap remake of that group’s “Walk This Way.” After that single and video conquered radio and MTV, the racial and stylistic barriers between rock and rap were never again quite so pronounced.

The list of “firsts” for Run DMC continues: first rappers to turn up on MTV, Saturday Night Live and the cover of Rolling Stone. They were the first rap act nominated for a Grammy Award (Best R&B Vocal Performance by a Group), for 1986’s Raising Hell. They even turned up at Live-Aid and on American Bandstand. Rap and its messages became more assimilated into the American mainstream following the trailblazing lead of Run DMC They did it all by being themselves—dressing without image or affectation, popularizing black tennis shoes in the process. They even did a popular ode to their favorite footwear, “My Adidas,” which also saluted the “beat of the street.”

Run DMC were to rap what Sam and Dave were to soul, defining their respective genres as frontmen in a duo format. It all started when a youthful DJ Run—nicknamed for his speedy turntable prowess—was deejaying for rap artist Kurtis Blow, who was managed by Run’s brother, Russell Simmons. (Simmons would go on to found Def Jam Recordings, becoming one of America’s premier black entrepreneurs.) The trio of Run, D.M.C. and Jam Master Jay, who had grown up and gone to school together in Hollis, Queens, issued their first single, which was produced by Kurtis Blow.

Coming four years after the earliest rap records, “It’s Like That”/”Sucker MCs” was hailed by critics as the first b-boy (“bad boy”) record, signaling a hardcore, streetwise new direction for rap. The delivery was straightforward, the words hard-hitting and the beats and backing sparse and powerful, with lots of space. Hip-hop writer Sasha Frere-Jones noted the “legible, populist minimalism” of Run DMC’s records, and made this observation about their interplay as rappers: “The rhymes go back and forth like beach balls between sea lions, with one finishing the other’s line, a strategy that hasn’t been heard since battle crews like Cold Crush Brothers ruled in 1980 and 1981.”

The albums that followed—Run-D.M.C. (1984), King of Rock (1985) and Raising Hell (1986)—firmly cemented Run DMC’s stature in the vanguard of this harder-edge “new school” rap. (A quarter century and several schools later, they are now viewed as the progenitors of “old school” rap.) The self-titled debut album was a veritable greatest-hits release in itself, with four of its songs—“It’s Like That,” “Hard Times,” “Rock Box” and “30 Days”—placing high on the R&B charts. King of Rock kept the streak going by contributing three Top 20 R&B hits of its own: the title track, “You Talk Too Much” and “Can You Rock It Like This.”

Run DMC’s third album, Raising Hell, made them rap’s first superstars. The album sold 3 million copies in the first year of its release, making it the best-selling rap album to date and pointing the way toward the ascension of rap and hip-hop as the dominant genres in popular music in the Nineties. The album yielded the titanic hits “My Adidas” (Number Five R&B), “You Be Illin’” (Number Twelve R&B, Number Twenty-Nine pop) and “It’s Tricky” (Number Twenty-One R&B, Number Fifty-Seven pop). The biggest breakthrough, however, came with their collaboration with Aerosmith on a remake of “Walk This Way.” The single and hugely popular accompanying video brought down the walls between rap and rock, ushering rap into the musical mainstream. With “Walk This Way,” Run DMC actually found themselves charting higher on the pop chart (Number Four) than the R&B chart (Number Eight). Their Together Forever Tour with the Beastie Boys furthered the union between black and white audiences.

While Run DMC unflinchingly rapped about urban realities, they also spread positive messages—pro-education, pro-voting, anti-gang and anti-drug—to help change the paradigm. “Our image is clean,” Run said in a 1986 cover story in Rolling Stone. “I’m no sociologist, but we’re role models, man, big-time role models.”

Run DMC’s fourth album, Tougher Than Leather (1988), provided the title and inspiration for a feature film in which they starred as themselves. On Back from Hell, they broke new ground by rapping over instrumental R&B grooves. The title alluded to the fact that this album followed a darker period in the business and personal lives of the group members. They finished out their six-album run for Profile Records with Down With the King, released in 1993. This ended their remarkable ten-year reign in rap’s vanguard. An attempted comeback on the Arista label in 2001 resulted in the disparaged Crown Royal album.

Despite their clean image, behind the scenes there were some issues with alcohol and drugs, which Darryl McDaniels (“D.M.C.”) forthrightly addressed in his autobiography, King of Rock: Respect, Responsibility, and My Life with Run-D.M.C. All the tribulations of the high life led his partner Run to become a born-again Christian. Now known as Rev. Run, he launched a family-based reality series, Run’s House. Tragically, Jam Master Jay fell victim to the sort of violence Run DMC deplored. After returning from a Run-D.M.C. tour, he was shot to death at his studio in Hollis, Queens in October 2002. His murder has never been solved.

The key albums in Run-D.M.C.’s catalog—Run-D.M.C., King of Rock, Raising Hell and Tougher Than Leather—were re-released in deluxe editions with bonus tracks in 2005. As new generations discover the old-school sound, Run DMC continue to receive their due for kicking the rap revolution into high gear. As R&B singer Pharrell noted in 2009, “Run DMC has been at the core of what could be possible for kids who liked big beats, catchy rhymes and hard guitars. From ‘Walk This Way’ to ‘My Adidas’ they changed the face of music forever.”

Inductees: Darryl "D.M.C." McDaniels (born May 31, 1964), Jason William Mizell "Jam Master Jay" (born January 21, 1965, died October 30, 2002), Joseph "Rev Run" Simmons (born November 14, 1964)

Run-D.M.C.

Music Interviews

RUN DMC On The Birth Of Rap

April 3, 2009 • Twenty-five years after RUN DMC's first single was released, member Darryl McDaniels sees the group's success as coming from a deliberate decision to create music that was sparse, hard-hitting and extremely rhythmic — just the way it sounded in those city parks.

Music Interviews

RUN DMC Crashes Rock's Hall Of Fame, Again

April 3, 2009 • When it's inducted on Saturday, RUN DMC will not be the first rap group to make it into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame — that was Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five. But RUN DMC did achieve a number of historic firsts during its heyday in the 1980s.

- Download

- Transcript

Music Interviews

Run-D.M.C.'s Reverend Run Goes Solo

October 24, 2005 • Farai Chideya talks with Reverend Run aka Rev Run, formerly of the rap trio Run-D.M.C. He's back with his first solo CD, Distortion, and his own reality show on MTV, Run's House.

- Download

- Transcript

The History of Hip-Hop

Rapper Darryl McDaniels of Run-D.M.C.

Fresh Air

August 30, 2005 • Darryl McDaniels is the "D.M.C" of the seminal rap group Run-D.M.C, which brought new fashion and language to popular culture. Their self-titled first album — the first rap record to go gold — was the first of a string of successful releases. (This interview originally aired May 19, 1997.)

https://www.spin.com/featured/run-dmc-raising-hell-interview/

Hell Raisin’

Run-D.M.C.'s Raising Hell turns 31 years old today. In honor of the anniversary, we've republished our feature on the album, which ran in our August 1986 print issue.

This is Mom’s Place, a combination Jamaican restaurant/car

service/pool hall on Hollis Avenue and 200th Street in Hollis, Queens,

the middle-class black neighborhood where the three members of Run-D.M.C.

grew up. On a cold, rainy Tuesday night, a couple dozen neighborhood

teenagers and slightly older folks have gravitated from the sidewalk in

front of a Chinese take-out place down the block and into Mom’s. Brown

paper sacks holding 40 dogs (40-ounce bottles of Olde English Malt

Liquor) circulate, and the sweetish chemical smell of crack cuts through

the damp air. A jukebox blares the Temps’ “Just My Imagination” over

the shrill bleeps from the video game, as someone sings along, off-key:

“Of all the skeezers in New York…” Mom surveys the crowd with a look you

could use to cut glass.

“Yo, turn us on to the box. We need two skeezers. I’m a

single-minded man with a plural. Yo, where the skeezers be hanging out

at?”

“You think you made up skeezers? Like Jonah said to the whale, I ain’t swallowing that.”

“Can I get some sidewalk here?”

“You gonna get the next 40, Jay? Jay! Jay!“

“Yo, I just heard your new album.”

“What did you think? You know it’s a winning album. Either that or

leave Hollis now. You can’t front on my album. You know it’s the best

shit. You don’t like ‘My Adidas’? You don’t like ‘Peter Piper’? You

don’t like ‘Hit It Run’?”

“You liked it, but you liked it in your mouth.”

“Run” (Joe Simmons), “D.M.C.” (Daryll McDaniels), “Jam-Master Jay”

(Jason Mizell), and I had been sitting in Jay’s 1986 black Lincoln for

about 20 minutes, discussing whether Mom would let me in. There’d been a

problem with a white guy before. But D.M.C. didn’t want to go bowling,

and on a Tuesday night in Hollis there isn’t a hell of a lot else to do.

So here we are. No problems. Everyone seems to think I’m someone else.

“Yo, Danny! … You’re not Danny? I’m gonna call you Danny anyway.”

Run explains: MC Danny White Boy. The only white guy in Hollis.

“Are you down with the Beastie Boys?”

This is the Hollis crew, the people who remember when Run and D.M.C.

were 15 and part of the Magnificent Super Seven, rapping in Hollis Park

in checkered blazers. Back in the di-days, the people who gathered

around Jay when he cut up Queen’s “We Will Rock You” and Billy Squier’s

“Big Beat” on the biggest sound system in the neighborhood included:

Butter Love, formerly Dougie Bee of the Magnificent Super Seven, now

part of the rap group called the Hollis Crew; Runnie Ray, with his

ghetto blaster wrapped in plastic against the rain; Cool Tee, a Super

Seven alumnus; stocky, nappy-haired Country; Shane, who compares

Cadillacs with D.M.C.; Daryl Woods, an almost skin-headed guy in a

varsity jacket who put laces into Jay’s Adidas; barrel-chested Jocko in a

gray down jacket and a gray Adidas ski hat.

“We made Run-D.M.C. what they are,” says a childlike 17-year-old

named Lamont, or Little L. “We go to all their jams and we boost them

and get the crowd pumping. Get the girls motivated. You know, we’re the

party motivators. Run used to hang out with my cousin, so they used to

be at the house a lot. He used to come with a book of rhymes. This was

back in the days. And Daryl, he used to be battling my cousin, drawing

Bruce Lee pictures.”

Everybody has a story: about boxing with D.M.C. using nine pairs of

socks for gloves, about how Run’s going to give them their big break.

“This guy’s the best rapper around here,” says Run, pointing to Romeo, a

handsome, caramel-complexioned youth with a transparent mustache and

leather gaucho hat. “We’ll go outside and jam.” And in the cold rain,

Run spits, lip farts, and otherwise human beatboxes while Romeo reels

off a sly string of rhymes. Jay comes out to join in, and picks the jam

way up with a counter rhythm.

“They don’t forget nobody,” adds Leslie, a 16-year-old with light

brown braids and a bright gold front tooth. “They play ball in the park.

And then the thing is, they say what’s true. It’s a rap, but it’s the

truth, and it’s all about life. You gotta be around it, and everything’s

out here.”

The crew is all here, and scattered among them is the most powerful

group playing any genre of music today: Run, in a black Def Jam baseball

jacket, black Adidas pants with the string hanging out, and beige

Kangol hat; D.M.C., in a furry blue Kangol, fur-trimmed snorkel parka,

blue Adidas warm-up top, unfaded blue Levis, and his trademark

black-framed glasses; and Jay, shooting pool with Country, in a nylon

Fila hooded warm-up top, black denim Lees, and the first example of

hip-hop merchandising, a black Kangol with the Run-D.M.C. logo.

Run-D.M.C. are on edge tonight. As they shoot the shit and swill 40s at Mom’s, they are waiting for their third album, Raising Hell,

to hit the racks. It will either break them out to a huge new audience

or signal that they’ve gone as far as they can. They also know that

they’ve got a motherfucker in the can. But the also know that rap

careers tend to be meteoric, then collapse. Their last album, the weakly

meandering King of Rock, raised some doubts that only two

strong non-LP singles could erase. And they know that LL Cool J, dishing

out the best of their old hard b-boy sound, is more than ready to push

them aside. King of Rock sold better than 800,000 copies, but

that was only a slight improvement over the sales of their debut album,

despite heavy MTV exposure. All three members believe that the rock

route was a mistake. This album could be their last chance.

“Everybody is looking for us to go downhill now,” says Jay.

“Everybody’s praying and planning for our downfall. If we come with

another weak album, we could be over with. Know what I’m saying? So we

went to work. A couple of people say, ‘Hey, you know if you come weak

this time, I’ll just be happy to step up.’ I ain’t going to say no

names. Like when Run’s lung collapsed (in December), I know a lot of

rappers who was real happy. There were people who actually talked about

it. That’s real fucked up. Some people think if Run-D.M.C. is out of the

race, it’s easy to go for yours out there.”

“Myself,” says Run, “I’m not interested in reaching a giant audience.

I could sell a million and be happy every time. I like the b-boys that I

know to buy records. I don’t want to go stretching my neck out to go

find a rock crowd or whatever, trying to sell 50 million, cause I don’t

even really understand that too much. I only know how to make what I

know how to make. If there’s a million b-boys that buy that type of

record, I’m straight. I’m not really trying to catch that Live Aid crowd

or whatever.”

Despite their boasts and middle-brow moralizing, Run-D.M.C.’s lyrics

have always been strikingly, powerfully banal autobiography. Cold, stark

pedestrianism, as if any deviation from the straight and narrow were a

step toward damnation. They rap about their friends, their glasses,

about taking airplane flights at huge heights. On the Aerosmith

collaboration, “Walk This Way,” their clumsy fumbling with Steve Tyler’s

jaded lyrics drives home just how unsexual the group is. They’ve always

been more about slicing away the bullshit than expanding a vision.

Drug rumors follow the band, and they probably aren’t as straight as

they play it. But they really are victoriously mundane, directed guys.

Family men.

Their money is in their cars: Jay’s Lincoln, D.M.C.’s Cadillac

Fleetwood, Run’s Buick Riviera, all 1986, all black. Run wants to trade

his in for a Jaguar; D.M.C. wants to give his to his father and buy a

van with a water bed in the back. But there are plenty of Caddies in

Hollis, and the three seem otherwise no different from the rest of the

people at Mom’s. “I gave my moms a lot of money,” says Jay. “Fixed up my

basement. Couple of color TVs, couple of VHSs, little bit of jewelry,

some gold. Santa Claus at Christmas. Few thousand in the bank.”

D.M.C.: “I had a dream last night I was in a Datsun 280-Z, came

out my house, and the cops just started chasing me and shit. And I went

up on the sidewalk and shit. I said, this shit is def. I woke up, I was

so happy.”

Run: “I dreamed we was in a fucking Datsun 280-Z, too. And the cops came up to us and Jay went through the light. And we said something to ‘em, and one cop said, ‘I don’t give a fuck what you do.’ It was a black cop, man. You know about wild dreams, man?”

Run is trying to make a point here. “Note that,” he says, as two more

members of the Hollis crew make their way into Mom’s. Daryl Woods hugs

each of them and wrestles him to the ground. Is this the usual Hollis

greeting? “No,” he says. “That’s they own dumb shit.” Run keeps asking

me about the new album. “You like ‘You Be Illin’ a lot, though? That’s

the deffest shit. “You Be Illin’ is def, Jay. You think the record ‘[My]

Adidas’ is going to do good, all the little kids are going to like it

and everybody? What do you think of ‘[It’s] Tricky’?”

A penny falls to the floor. “Waste not,” screams Daryl Woods,

slapping his huge palm over it, “want not.” Run and D.M.C., fortified by

Olde English, break into an impromptu version of “Hit It Run,” with Run

sputtering a beat behind D.M.C.’s raps. “Everybody likes that beatbox

shit,” he says. “Bugs everybody the fuck out. Lets motherfuckers know

what time it is.”

After their unsuccessful flirtation with musicality on King of Rock, Run-D.M.C.

have returned to their roots. They ditched producer Larry Smith (he

still makes great pop records with Whodini) and produced most of Raising Hell

themselves in a street style. Despite the cover version of Aerosmith’s

“Walk This Way,” the album is almost exclusively hard b-boy jams, with

little or not music. Just beats and rhymes– the style that they invented

in 1983 with “Sucker M.C.’s,” the B-side of their first single, and

turned into the dominant form in hip hop. The shit that put them on top

in the first place.

“Before us,” says Jay, “rap records was corny. Everything was soft.

Nobody made no hard beat records. Everybody just wanted to sing, but

they didn’t know how to sing, so they’ll just rap on the

record. There was no real meaning to a rapper. Bam[baataa] and them was

getting weak. Flash was getting weak. Everybody was telling me it was a

fad. And before Run-D.M.C. came along, rap music could have been a fad.”

“None of them was hard-hitting street jams,” says Run. “We came and got ill. There it is.”

“There was never a b-boy record made until we made ‘Sucker M.C.’s.'” Jay continues. “Now you got groups that just try to be all

b.boy. Rappers wasn’t even street before we came out at all. Rappers

used to dress up, leather this, leather that, chains. Did you ever see

them back in the days? Motorcycle-gang-looking-people. When we came in,

we dressed the way we always dressed, and we just did our thing. We was

street. We was hard. When people seen us, they seen that we was regular,

normal people. Didn’t go around with no braids in our hair, flicking

them around. People tend to like what’s real. And we was real.

“‘Sucker M.C.’s.,’ ‘Jam-Master Jay,’ those records were trendsetting

records. People based their whole lives on the way we looked. Even LL

Cool J used to wear boots when he started rapping. His image wasn’t

Kangol and rough and all that. He got that from us. We told him, ‘If you’re going to be from around our way, you can’t be like that.'”

You’re a five dollar boy and I’m a million dollar man

You’ze a sucker M.C., and you’re my fan. You’re tryna bite lines or rhymes of mine You’re a sucker M.C. in a pair of Calvin Kleins

You’ze a sucker M.C., and you’re my fan. You’re tryna bite lines or rhymes of mine You’re a sucker M.C. in a pair of Calvin Kleins

–from “Sucker M.C.’s”

Run: “I had a dream last night I have my girl a car, but she

didn’t want it. She wanted to paint it. But it turned into a barbecue

grill that could make French fries and everything. How ’bout a car that

could make French fries?”

D.M.C: “I had a crazy dream I was on the road with Michael

Jackson. We went into a room, and we didn’t have to be at the show till

five or something, and there was three Chinese girls in there tending to

all my needs; it was real crazy, ironing my clothes. I went and took a

shower, and I’m in the shower naked, and in the dream someone said,

‘Someone’s coming, someone’s coming.’ And I couldn’t see the face, but

someone came in there with a knife. And it was like, what’s that movie?

Alfred Hitchcock. Psycho. And then I just woke myself up. Word.”

“Everybody’s trying to call us the second generation of rap,” says

Jay. “But we was doing it back in the days. We just wasn’t televised.

Run was out there. Before the Sugar Hill Gang made ‘Rapper’s Delight,’ I

was scratching already.

I was about 15 by that time, so I been

scratching.”

You can neatly divide rap history at Run-D.M.C.’s first single,

“Sucker M.C.’s.” It was as radical and influential a record as “Anarchy

in the UK.” With “The Message,” Sugar Hill abandoned the dominant

production machine in rap music, and the label’s house band left. The

artists who built the music from a Bronx subculture to a national

phenomenon were suddenly hurled into a collective decline. As rappers

tried to repeat the huge crossover success of “The Message” with

transparently insincere social-consciousness raps, and break dancers

made their way into soft-drink commercials, hip hop was losing its

essential street urgency. In a little over three minutes, “Sucker

M.C.’s” literally revived and redefined the anemic genre. Two guys and a

gunshot drum machine (Jay hadn’t joined the group yet,) slicing through

the malaise with the rawest kind of street talk: the dozens. Almost

overnight, the dis (disrespect) rap controlled the street, and rappers

started stripping their sound of all music. Hip hop was no longer, as

Afrika Bambaataa called it, a renegade breed of funk. “Sucker M.C.’s”

gave it its own brutal sound.

“It was just out there,” says Run, “like basketball, man. Something

to do. Found out I was good at scratching and made a record. There it

is.” This sort of “case closed” ejaculation, condensing eight years of

his life into an epigram, is typical Run. He’s the loud member of the

group, periodically screaming a line from a song or pumping bravado.

“Bloods aren’t going to fuck with us, I’m telling you.” I know my town.”

But when he’s drawn into conversation, he’s uncomfortable and closemouthed. In the pool hall he’s jumpy, running outside, never spending much time with anybody.

“I ain’t usually out here,” he says. “I never go nowhere. I’m not

into going out. I just play basketball, come in the house, eat dinner,

and go to sleep. I don’t like it out. I just stay in the house.”

“Run never was a hang-out guy,” Jay confirms. “Ever. He would go to a

party and go home. ‘Cause Run always had to go home to his wife and

kid.” Run just bought a house in Hollis, but for now he still lives with

his father, his girlfriend of more than six years, and their almost

three-year-old daughter, Vanessa. He is almost constantly looking for a

phone to call home.

“Yes. No. No, I’m coming right home after this.”

“Cut Creator!” Shane yells, mimicking the line from LL Cool J’s “Rock the Bells”: “What’s your DJ’s name? / Cut Creator.”

“Valerie,” says Run. “That ain’t funny, man. She should read that in the article, then you in trouble.”

Run’s earned a reputation for being rude and smart-assed. He doesn’t

pay much attention to anything I say unless it concerns his music. (By

the end of our three says, he’s able to tell me just about every record I

like, which mix, and why.) He got his start as DJ Run Love, the Song of

Kurtis Blow. Blow and Run’s older brother, Russell,

who now runs the Def Jam label and manages Run-D.M.C., LL Cool J,

Whodini, the Beastie Boys, and a host of other rappers, were freshmen at

the City University of New York in Harlem, where Simmons started Rush

Productions to book rap acts into college parties. At 12, Run joined

Blow onstage and the two traded places in the spotlight before an

audience that was hungry for this new music.

Simmons has been the group’s guiding influence. At 28, Run’s

prematurely balding older brother, who rarely leaves the house without a

Kangol, may be the most powerful figure in hip hop. His career formed

the center of the film Krush Groove, and his Rush Productions

groups have traditionally been the heart of any big rap tour. When Slick

Rick split from Doug E. Fresh, he signed with Rush. And with Def Jam,

as all new Rush artists now automatically do.

“The first year,” says Jay, “Russell had us out there working for

free. That means a lot of towns had big packed shows, and Run-D.M.C. was

working free. He wasn’t just trying to get money, he was trying to

build something. So I love Russell for that, cause he built us.”

Unlike his protégés, the older Simmons left Hollis and lives in

Manhattan. He’s a visionary while Run is content. He has worked very

hard as an independent businessman, and built a small empire. His vision

is probably all that stands between Run-D.M.C. and the facile

satisfaction of being local heroes. Like obedient younger brothers, Run,

D.M.C., and Jay dutifully do what he wants.

School girl sleazy with classy kinda sassy

Little skirt hanging way up her knee

It was three young ladies in the school gym locker

And I found they were looking at D.

Little skirt hanging way up her knee

It was three young ladies in the school gym locker

And I found they were looking at D.

–from “Walk This Way”

Two car stories:

I’m riding with Jay in his Continental, breathing the strawberry

and green apple scent of ten pine-tree air fresheners: two hanging from

the rear-view mirror, four from the ceiling, and two from each side of

the backseat. An ’86 black Cadillac Fleetwood pulls up beside us. The

automatic windows of each car lower. Run sticks his head out the

passenger-side window of the Fleetwood and yells: “Burger King!”

Run: “I was driving past Daryl Woods on his bicycle one day, and I

said, ‘Let me just dis him real quick.’ I pulled over and said, ‘I

believe that’s a hard way to get around.’ He said, ‘Perhaps’.”

A fleet of cruisers are assembled in front of D.M.C.’s house. There’s

Jay’s back Continental, Run’s black ’96 Buick Riviera, Fat Boy Markie

Dee’s silver Mercedes, and, just pulling up, D.M.C.’s black Fleetwood.

Fifteen or 20 people from the neighborhood are hanging out around the

cars.

“Where’s the kid at?” says Run, and finding me, leads me and D.M.C.

inside; no, he tells Mrs. McDaniels, it isn’t necessary to get a

pizza. D.M.C.’s brother Al and a light-skinned, freckled guy named Bimmy

follow us down to the basement, where a row of two-liter soda bottles

and an ice bucket flank candy dishes filled with nuts.

“This is like my waiting room,” says D.M.C., cueing up and scratching a copy of Yellowman and Fathead’s Bad Boy Shanking

album on the glass-enclosed stereo. “When people come over, I gotta get

up, take a shower, brush my teeth, clean my sneakers, shave. So I tell

them to come down here and wait. I’m just living a life, man.” He grins

broadly.

Like Run, D.M.C. is a hard man to get a word out of. He just doesn’t

understand why you want to know, why you aren’t as beatifically content

as he is. “Today,” he says, “I ain’t got nothing to worry about. I

washed my car, I gave my friend some money, he gonna pay me back

tonight.” Five days into kicking cigarettes, he seems happy.

“I used to draw the comic books,” says D.M.C. “Spiderman, the Hulk,

Captain America, Superman, and all that. Until I was 12. When I turned

12 I found out about rap and started rapping. First, I was a DJ. I used

to DJ in my basement. Then I got tired of deejaying, and I just started

writing rhymes. I used to rhyme for hours. Drink a 40-ounce beer, Olde

English, and I wouldn’t be able to shut up for the whole day and the

whole night. Be rhyming all night loud everywhere I go. Everybody’d tell

me, ‘Yo, why don’t you shut up, you been rhyming all night. Shut up, I

don’t like this guy he won’t shut up.’ Rapping was more fun than being a

DJ for me. ‘Cause I could get on the mike and tell people how

devastating I am.”

After a few Yellowman and Fathead tracks, he pulls out an album of

old hip-hop instrumentals, and plays a rapless version of Grandmaster

Flash’s “Freedom.”

“Remember this?” he asks, and passes the album jackets around. It’s a

generic white sleeve, custom decorated as the first record by the

Magnificent Super Seven. In different-colored felt-tip pens, Easy Dee

(D.M.C.), DJ Run, Terrible Tee, Runny Ray, Capri, Masta Tee Thiggs, and

Dougie Bee invested the jacket with their names and their most unguarded

hopes. It’s a beautiful artifact of innocence and diligence ,a

meticulous enshrinement of seven adolescents’ most prized icons–their

names and their dreams.

He’s the better of the best

Best believe he’s the baddest

Perfect timing when I’m climbing

I’m a rhyming apparatus Lotta guts when he cuts Girls move their butts His name is Jay come to play He must be nuts

Best believe he’s the baddest

Perfect timing when I’m climbing

I’m a rhyming apparatus Lotta guts when he cuts Girls move their butts His name is Jay come to play He must be nuts

From “Peter Piper”

Jay lives in an apartment in the basement of his mother’s house with

his girlfriend and their newborn baby, Jason Jr. Possibly because he’s a

new father, Jay seems the most responsible member of the group. In

Burger King, he was the only one to throw out his garbage; D.M.C. saw

him, looked back at the table, and continued to the checkout counter to

deliver autographs. In the pool hall, when Daryl Woods tried to put

Danny White Boy and me into a mock lineup, Jay put a stop to it. “I

believe if one of my live homeboys came here,” he told Woods, “he’d fuck

one of y’all up.” Then, to me: “I don’t even come down here no more.

You bring a friend down here, and they try to disrespect you. Ain’t

nobody in here anything compared to nothing.”

“I was a wild kid,” he says. “I hung out late. Hung out till the

morning sometimes with my friends. I was the motivator. When I was 14,

15, all the big guys would say, ‘Where we going tonight?’ Any event that

went down, I was on that train. I stopped being wild when I was 16. I

started wanting to go to school all the time, wanting to be into books,

When I say wild, I just didn’t care. I was smarter than everybody in my

class all the time, so I just felt like I didn’t have to do the work. I

was going to school, but I was messing up in school.

“After my father died, I really wised up. Everything changed for me

then. I wanted to do what was right. Settled down, got a girlfriend. I

was never really close, close friends with Run and D.M.C., but me and

Run used to play basketball together, and me and D.M.C. used to drink

Olde English.”

As a kid, Jay played bass and drums at block parties in a corny band,

but saw that DJs had more pull than bands. “I had a turntable,” he

says, “my friend had a turntable, all I had to do was buy a mixer. They

had mixers for like 39 dollars. So my moms got me a mixer, and I started

off like that. DJ battles was a fun thing. It was like a big park, and

you’re over there and I’m over here. My crew used to have so much

equipment that if you was anywhere that we could see you, they couldn’t

hear you. Parties in Hollis, I was the DJ. Best guy in the neighborhood,

for sure.

“The night I gave my biggest party, Run and D. went to the studio and

put down ‘It’s Like That.’ I couldn’t go. They couldn’t be at my party.

I was mad that D. and Run wasn’t at my party. Next day they came around

with a tape. We started doing shows.”

When “It’s Like That” and “Sucker M.C.’s” became hits, Jay dropped

out of Queens College, in the middle of his freshman year. Run dropped

out of LaGuardia Community College, where he was studying mortuary

science, and D.M.C. left St. John’s. For a group that claims to be a the

first street-rap crew, these middle-class citizens aren’t exactly

street kids.

“The feeling inside of me was never a soft feeling,” says Jay. “It’s

no matter where you’re from. It’s who you are. There’s no difference

between the Bronx and Queens. It’s just that we live in houses and they

live in projects. So what? They went outside and had a fight with the

guy down the block, we went outside and had a fight with the guy around

the corner. No difference. Everybody seems to think that cause we come

from a nice neighborhood… yo, everything that was everywhere else was in

Queens, too. Drugs was out there. And then, I think that people from

Queens have something more to prove than people from the Bronx. Mo Dee

[from the Tenacious Three] and them, since they came from a rough

neighborhood, they tried to act like they was from somewhere else. They

used to be b-boys, but now they want to change their image to be like

pop or something.”

As far as Run-D.M.C.’s label is concerned, Jay is not a member of the

group. He isn’t signed to the label, and his picture appears on the

back but never the front of the album covers. Until the new album, his

royalties were half those of his partners: one percent of the retail

sales. On Raising Hell, he gets two. “I spent the most time in

the studio,” he says. “I put the album together. It’s all coming from a

DJ’s point of view, instead of a musician’s point of view. If there was a

producer of this album, Jason Mizell would be the producer of the

album. But it’s not. Russell Simmons and Rick Rubin [Simmons’ partner at

Def Jam] are. But I feel I produced it more than anybody produced it.”

A gold Cadillac insignia the size of a tennis ball hangs from a chain

around D.M.C.’s neck, and a slightly smaller one gleams on his finger.

“Anybody that sees him knows that that’s a rapper,” says Run, his friend

since kindergarten. Though he limits his wardrobe to Adidas-wear and

jeans (Run-D.M.C. recently posed for an Adidas promotional poster), he

has the biggest beeper and the most gold. He gets up to change the

record.

“You hear this record,” Run says, peeling the decals off a Rubik’s

cube in frustration to get one all-black side. “‘You can’t change your

fate.’ I don’t appreciate that. You can change your fate.”

But D.M.C. isn’t concerned. Nor is he worried about the band’s

competition. “I’m telling you,” he tells his nervous partner, “Niggers

don’t put us down for not being out. Niggers still love us. LL could