SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2019

VOLUME SEVEN NUMBER TWO

HOLLAND DOZIER HOLLAND

(L-R: Lamont Dozier, Eddie Holland, Brian Holland)

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

SHIRLEY SCOTT

(June 15-21)

FREDDIE HUBBARD

(June 22-28)

BILL WITHERS

(June 29- July 5)

OUTKAST

(July 6-12)

J. J. JOHNSON

(July 13-19)

JIMMY SMITH

(July 20-26)

JACKIE WILSON

(July 27-August 2)

LITTLE RICHARD

(August 3-9)

KENNY BARRON

(August 10-16)

KENNY BARRON

(August 10-16)

BUSTER WILLIAMS

(August 17-23)

MOS DEF

(August 24-30)

RUN-D.M.C

(August 31-September 6)https://www.allmusic.com/artist/mos-def-mn0000927416/biography

Mos Def

(b. December 11, 1973)

Artist Biography by Jason Birchmeier

Initially regarded as one of the most promising rappers to emerge in the late '90s, Mos Def, aka Yasiin Bey,

turned to acting in subsequent years as music became a secondary

concern for him. He did release new music from time to time, including

albums such as The New Danger (2004), but his output was erratic and seemingly governed by whim. Mos Def

nonetheless continued to draw attention, especially from critics and

underground rap fans, and his classic breakthrough albums -- Black Star (1998), a collaboration with Talib Kweli and Hi-Tek; and Black on Both Sides (1999), his solo debut -- continued to be revered, all the more so as time marched forward. Mos Def

often used his renown for political purposes, protesting in the wake of

Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the Jena Six incident in 2007, for

instance.

Born Dante Terrell Smith Bey on December 11, 1973, in New York City's Brooklyn borough, Mos Def

began rapping at age nine and began professionally acting at age 14,

when he appeared in a TV movie. After high school, he began acting in a

variety of television roles, most notably appearing in 1994 on a

short-lived Bill Cosby series, The Cosby Mysteries. In 1994, Mos Def formed the rap group Urban Thermo Dynamics

with his younger brother and sister, and signed a recording deal with

Payday Records that didn't amount to much. In 1996, his solo career was

launched with a pair of high-profile guest features on De La Soul's "Big Brother Beat" and Da Bush Babees' "S.O.S." A year later, in 1997, Mos Def

released his debut single, "Universal Magnetic," on Royalty Records,

and it became an underground rap hit. This led to a recording contract

with Rawkus Records, which was just getting off the ground at the time,

and he began working on a full-length album with like-minded rapper Talib Kweli and producer Hi-Tek. The resulting album, Black Star (1998), became one of the most celebrated rap albums of its time. A year later came Mos Def's solo album, Black on Both Sides, and it inspired further attention and praise. Yet, aside from appearances on the Rawkus compilation series Lyricist Lounge and Soundbombing,

no follow-up recordings were forthcoming, as the up-and-coming rapper

turned his attention elsewhere, away from music.

During the early 2000s, Mos Def

acted in several films (Monster's Ball, Bamboozled, Brown Sugar, The

Woodsman) and even spent some time on Broadway (in the Pulitzer

Prize-winning Topdog/Underdog). He simultaneously worked on the Black Jack Johnson project with several iconic black musicians: keyboardist Bernie Worrell, guitarist Dr. Know, drummer Will Calhoun, and bassist Doug Wimbish. This project aimed to reclaim rock music, especially the rap-rock hybrid, from such artists as Limp Bizkit, who Mos Def openly despised. Mos Def

hoped to infuse the rock world with his all-black band, and during the

early 2000s, he performed several small shows with his band around the

New York area. In October 2004, he finally delivered a second solo

album, The New Danger, which involved Black Jack Johnson on a few tracks.

Two years later, after a few more acting roles --

including the Golden Globe-winning Lackawanna Blues and the Emmy-winning

Something the Lord Made, both of which were made-for-television movies

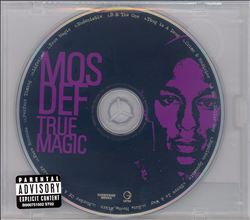

-- Mos Def released his third solo album, True Magic

(2006). A contract-fulfilling release for Geffen, which had absorbed

Rawkus years prior, the album trickled out in a small run during the

last week of 2006. Bizarrely, the disc came with no artwork and was sold

in a clear plastic case -- though its single, "Undeniable," did manage

to grab a Grammy nomination for Best Rap Solo Performance. Released on

the Universal-distributed Downtown label, The Ecstatic followed in June 2009. At that point, Mos Def had significant acting roles in Michel Gondry's Be Kind Rewind (in which he co-starred with Jack Black) and Cadillac Records (he played Chuck Berry). The Ecstatic nabbed another Grammy nomination. Throughout the next few years, he lengthened his acting résumé and contributed to Gorillaz' Plastic Beach, Robert Glasper Experiment's Grammy-winning Black Radio, and A$AP Rocky's At. Long. Last. A$AP, among other albums. In January 2016, he made an announcement through Kanye West's

website; after he disputed a recent arrest in South Africa for breaking

an immigration law, he declared his retirement from the entertainment

industry and the forthcoming release of his final album, due later in

the year.

https://brooklynrail.org/2007/04/music/mos-def-and-the-new

Mos Def’s True Magic is anything but the throwaway recording it is often accused of being; it is in fact a very serious culmination of this hip-hop artist’s musical progression. Released quietly by Geffen in late December, it featured no artwork or sleeve, simply a photo of Mos stenciled straight onto the CD inside a clear case. It was quickly and mysteriously yanked from stores by the label shortly thereafter, the rumor being that it would be re-released “properly” sometime in the spring. After Mos’s much-ballyhooed 1999 debut, Black On Both Sides, and his followup, the 2004 rock/hip-hop hybrid The New Danger, accusations that he was operating on cruise-control dogged True Magic. But whereas those earlier records felt mashed together to make a whole, True Magic is a lean, straightforward hip-hop record. Stripped down and spare, it’s a retro b-boy tome—lyrical dexterity coupled with Mos’s unique vocal take on the African-American musical tradition. Along with a series of gigs he and his live band performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in February, True Magic represented a deep reflection on the state of hip-hop in 2007.

Mos has become famous for the spirited live performances he’s sprinkled across New York over the past few years—experimentation with his hard-rock band, Black Jack Johnson, as well as performances with various jazz ensembles. His shows at Blue Note in 2004, in which he reportedly stepped aside and let the musicians rule the night, explored Miles’ Bitches Brew along with an energetic, if eyebrow-raising, interpretation of Beyonce’s “Crazy in Love.” Along with an early 2007 performance at Jazz at Lincoln Center, these performances have become legend. At BAM, Mos performed with pianist Robert Glasper and a bass/drums/guitar core band, along with a DJ, Preservation. The band’s tenor and soprano saxes were augmented by the eight-member Hypnotic Brass Ensemble, recently transplanted from Chicago. Blowing away the BAM Opera House with rich, textured horns, this was a band to be taken seriously. Everyone, including Mos, wore matching T-shirts with a photo of Barack Obama and the words “So Fresh, So Clean” stenciled in green-and-red block lettering. (On the back was a photo of the slain Sean Bell.)

What was startling to attendees of the BAM performance’s mixture of classic hip-hop, R&B, jazz interpretation, and rock—a different kind of American Songbook—was the realization that this was the promise hip-hop offered back in the 1980s: a sampling and reinterpretation of songs from across the musical spectrum. The Brooklyn audience—culturally diverse like the borough itself, but heavily African-American—was so taken with the band’s lively cover of BBD’s “Poison” (Mos recreating the crouching circle dance from the music video straight-faced) that the house was nearly brought down. Imagine a blaring horn riff in place of the line “That girl is—poi-sunnnn.” Mos’s powerful interpretation of “I Put a Spell on You,” starting out a cappella and then taken up by the band, was nuanced, owing as much to Nina Simone’s cover as Screamin’ Jay’s original. A sense of rapture permeated the air in the Howard Gilman Theater as Mos connected African-American musical traditions, the audience like starving multitudes fed food they hadn’t realized they were hungry for.

At BAM, Mos visited portions of the old-school “Undeniable” and the love-gone-wrong plea “U R the One,” comfortably traversing a spectrum of musical styles, making them his own. (Unfortunately, he didn’t perform “Napoleon Dynamite,” one of True Magic’s high points, a blaxploitation funk tune with choir-like accompaniment and a layer of lyricist-lounge storytelling on top.) The sheer breadth of the material was bewildering: Neil Young’s “Like a Hurricane,” the Pharcyde’s “Passing Me By.” If indeed hip-hop is a contemporary cousin to jazz, then experimentation with its parameters must be the rule rather than the exception.

Like its predecessors, True Magic finds Mos singing as often as MC’ing. There are those who take exception to his tendency to croon unabashedly as much as he raps, but they miss the point: This is the complete package. Mos puts any number of contemporary R&B singers to shame, pairing vocal range with impressive lyrical and spiritual depth. Vamping on Stevie Wonder’s “That Girl” with his own “Hip-Hop” at BAM, he is Marvin Gaye enveloped inside KRS-One—a deadly combination. When Mos put aside his singing to spit “Life Is Real” off The New Danger, he was refusing to be pigeonholed as one particular type of performer. Often accused of neglecting music in favor of his burgeoning acting career, he responds with these periodic, powerful live performances. True Magic, a rap record with hints of soul, rock, and spoken-word jazz, represents what hip-hop really is: all of these and yet none. Like jazz, attempting to define hip-hop in a world of Lauryn Hill, Japanese turntablists, reggaeton, and Brazilian baile (and retro heavy-rockers Earl Greyhound, who played upstairs in the BAMcafé after Mos’s Saturday performance as part of a Black Rock Coalition residency) is pointless.

Something of a political artist, if anyone in hip-hop or popular music can don that hat, Mos has produced one of the most unabashedly scathing critiques of the Bush administration’s response to Hurricane Katrina in “Dollar Day (Surprise, Surprise),” off of True Magic (with beats borrowed from New Orleans’ Juvenile). A selected sampling of its lyrics, verses of which were performed at BAM:

As powerful as the BAM performance was, it was not impeccable—extremely loose to the point of being informal, like sitting in on a rehearsal. The long rests between songs invited much verbal jockeying from the rowdy balcony crowd. And True Magic itself comes off more like a demo than a finished product at times. I’m still not sure what to make of Mos’s incessant sampling of well-known, previously used hip-hop beats. On The New Danger it was Jay-Z’s “Takeover,” while True Magic uses the GZA’s “Liquid Swords” and the UTP crew’s “Nolia Clap.” Is there some kind of referential language being spoken, or is it just lazy filler? Mos appears to be attempting to connect historical and musical dots (Juvenile and UTP being from New Orleans), but a deeper meaning seems elusive.

A colleague who is a fan says that though she finds “U R the One” candid about the politics of romantic breakups, she nevertheless thinks the lyrics overly provocative and profane. Mos finds himself donning the “conscious rapper” mantle for one wing of the hip-hop community, but too “street” for those expecting constant political piety. Of course, most of our hip-hop heroes straddle the line between saint and pariah, and doing so is more a sign of vitality than a negative.

With at least half a dozen films set to be released soon, as well as book deals and his music, Mos has evolved into a potential heir to the title of “hardest working man in showbiz.” Anyone who doubts his being one of the most exciting artists in contemporary music need only have caught one of his BAM performances. Indeed, it’s a shame that more people outside of New York City will never see these live performances—the hip-hop world in 2007 needs the example, if only to remind us what hip-hop can be, and as a counterpoint to limited interpretations on MTV and BET. An MC accompanied by a live brass band interpreting Madvillain’s “Rainbows” should be beheld by as many contemporary music listeners as possible.

For all of its shortcomings, True Magic’s promise is immense—minimalist hip-hop with bursts of rich, textured song. Whether the record will be given a proper release is anyone’s guess. We need this type of record though, as we need Mos Def. At BAM he closed, appropriately, with De La Soul’s “Stakes Is High.” Giving the crowd a little of what it wanted—he had been badgered from the balcony all night with requests for Black Star’s “Definition”—Mos enfolded inside the De La verses from his “Umi Says.” It was a poignant close to a powerful night.

https://www.thedailybeast.com/how-hip-hop-lost-mos-def-yasiin-bey-announces-retirement-and-final-album

https://brooklynrail.org/2007/04/music/mos-def-and-the-new

Music

Mos Def and the New Old Magic

Mos Def’s True Magic is anything but the throwaway recording it is often accused of being; it is in fact a very serious culmination of this hip-hop artist’s musical progression. Released quietly by Geffen in late December, it featured no artwork or sleeve, simply a photo of Mos stenciled straight onto the CD inside a clear case. It was quickly and mysteriously yanked from stores by the label shortly thereafter, the rumor being that it would be re-released “properly” sometime in the spring. After Mos’s much-ballyhooed 1999 debut, Black On Both Sides, and his followup, the 2004 rock/hip-hop hybrid The New Danger, accusations that he was operating on cruise-control dogged True Magic. But whereas those earlier records felt mashed together to make a whole, True Magic is a lean, straightforward hip-hop record. Stripped down and spare, it’s a retro b-boy tome—lyrical dexterity coupled with Mos’s unique vocal take on the African-American musical tradition. Along with a series of gigs he and his live band performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in February, True Magic represented a deep reflection on the state of hip-hop in 2007.

Mos has become famous for the spirited live performances he’s sprinkled across New York over the past few years—experimentation with his hard-rock band, Black Jack Johnson, as well as performances with various jazz ensembles. His shows at Blue Note in 2004, in which he reportedly stepped aside and let the musicians rule the night, explored Miles’ Bitches Brew along with an energetic, if eyebrow-raising, interpretation of Beyonce’s “Crazy in Love.” Along with an early 2007 performance at Jazz at Lincoln Center, these performances have become legend. At BAM, Mos performed with pianist Robert Glasper and a bass/drums/guitar core band, along with a DJ, Preservation. The band’s tenor and soprano saxes were augmented by the eight-member Hypnotic Brass Ensemble, recently transplanted from Chicago. Blowing away the BAM Opera House with rich, textured horns, this was a band to be taken seriously. Everyone, including Mos, wore matching T-shirts with a photo of Barack Obama and the words “So Fresh, So Clean” stenciled in green-and-red block lettering. (On the back was a photo of the slain Sean Bell.)

What was startling to attendees of the BAM performance’s mixture of classic hip-hop, R&B, jazz interpretation, and rock—a different kind of American Songbook—was the realization that this was the promise hip-hop offered back in the 1980s: a sampling and reinterpretation of songs from across the musical spectrum. The Brooklyn audience—culturally diverse like the borough itself, but heavily African-American—was so taken with the band’s lively cover of BBD’s “Poison” (Mos recreating the crouching circle dance from the music video straight-faced) that the house was nearly brought down. Imagine a blaring horn riff in place of the line “That girl is—poi-sunnnn.” Mos’s powerful interpretation of “I Put a Spell on You,” starting out a cappella and then taken up by the band, was nuanced, owing as much to Nina Simone’s cover as Screamin’ Jay’s original. A sense of rapture permeated the air in the Howard Gilman Theater as Mos connected African-American musical traditions, the audience like starving multitudes fed food they hadn’t realized they were hungry for.

At BAM, Mos visited portions of the old-school “Undeniable” and the love-gone-wrong plea “U R the One,” comfortably traversing a spectrum of musical styles, making them his own. (Unfortunately, he didn’t perform “Napoleon Dynamite,” one of True Magic’s high points, a blaxploitation funk tune with choir-like accompaniment and a layer of lyricist-lounge storytelling on top.) The sheer breadth of the material was bewildering: Neil Young’s “Like a Hurricane,” the Pharcyde’s “Passing Me By.” If indeed hip-hop is a contemporary cousin to jazz, then experimentation with its parameters must be the rule rather than the exception.

Like its predecessors, True Magic finds Mos singing as often as MC’ing. There are those who take exception to his tendency to croon unabashedly as much as he raps, but they miss the point: This is the complete package. Mos puts any number of contemporary R&B singers to shame, pairing vocal range with impressive lyrical and spiritual depth. Vamping on Stevie Wonder’s “That Girl” with his own “Hip-Hop” at BAM, he is Marvin Gaye enveloped inside KRS-One—a deadly combination. When Mos put aside his singing to spit “Life Is Real” off The New Danger, he was refusing to be pigeonholed as one particular type of performer. Often accused of neglecting music in favor of his burgeoning acting career, he responds with these periodic, powerful live performances. True Magic, a rap record with hints of soul, rock, and spoken-word jazz, represents what hip-hop really is: all of these and yet none. Like jazz, attempting to define hip-hop in a world of Lauryn Hill, Japanese turntablists, reggaeton, and Brazilian baile (and retro heavy-rockers Earl Greyhound, who played upstairs in the BAMcafé after Mos’s Saturday performance as part of a Black Rock Coalition residency) is pointless.

Something of a political artist, if anyone in hip-hop or popular music can don that hat, Mos has produced one of the most unabashedly scathing critiques of the Bush administration’s response to Hurricane Katrina in “Dollar Day (Surprise, Surprise),” off of True Magic (with beats borrowed from New Orleans’ Juvenile). A selected sampling of its lyrics, verses of which were performed at BAM:

It’s Dollar Day in New Orleans It’s water, water everywhere and people dead in the streets And Mr. President he ’bout that cash He got a policy for handlin’ the niggaz and trash And if you poor or you black I laugh a laugh they won’t give when you ask You better off on crack Dead or in jail, or with a gun in Iraq And it’s as simple as that God save these streets One dollar per every human being It’s that Katrina Clap (Clap, clap, clap, clap)This is something of the political promise of hip-hop twenty years ago. One can only imagine Geffen’s reaction when Mos was arrested by police outside Radio City Music Hall during the 2006 MTV Video Music Awards, attempting to perform “Dollar Day” from a truck bed stage. (Peep the YouTube footage.)

As powerful as the BAM performance was, it was not impeccable—extremely loose to the point of being informal, like sitting in on a rehearsal. The long rests between songs invited much verbal jockeying from the rowdy balcony crowd. And True Magic itself comes off more like a demo than a finished product at times. I’m still not sure what to make of Mos’s incessant sampling of well-known, previously used hip-hop beats. On The New Danger it was Jay-Z’s “Takeover,” while True Magic uses the GZA’s “Liquid Swords” and the UTP crew’s “Nolia Clap.” Is there some kind of referential language being spoken, or is it just lazy filler? Mos appears to be attempting to connect historical and musical dots (Juvenile and UTP being from New Orleans), but a deeper meaning seems elusive.

A colleague who is a fan says that though she finds “U R the One” candid about the politics of romantic breakups, she nevertheless thinks the lyrics overly provocative and profane. Mos finds himself donning the “conscious rapper” mantle for one wing of the hip-hop community, but too “street” for those expecting constant political piety. Of course, most of our hip-hop heroes straddle the line between saint and pariah, and doing so is more a sign of vitality than a negative.

With at least half a dozen films set to be released soon, as well as book deals and his music, Mos has evolved into a potential heir to the title of “hardest working man in showbiz.” Anyone who doubts his being one of the most exciting artists in contemporary music need only have caught one of his BAM performances. Indeed, it’s a shame that more people outside of New York City will never see these live performances—the hip-hop world in 2007 needs the example, if only to remind us what hip-hop can be, and as a counterpoint to limited interpretations on MTV and BET. An MC accompanied by a live brass band interpreting Madvillain’s “Rainbows” should be beheld by as many contemporary music listeners as possible.

For all of its shortcomings, True Magic’s promise is immense—minimalist hip-hop with bursts of rich, textured song. Whether the record will be given a proper release is anyone’s guess. We need this type of record though, as we need Mos Def. At BAM he closed, appropriately, with De La Soul’s “Stakes Is High.” Giving the crowd a little of what it wanted—he had been badgered from the balcony all night with requests for Black Star’s “Definition”—Mos enfolded inside the De La verses from his “Umi Says.” It was a poignant close to a powerful night.

https://www.thedailybeast.com/how-hip-hop-lost-mos-def-yasiin-bey-announces-retirement-and-final-album

IS THIS GOODBYE?

How Hip-Hop Lost Mos Def: Yasiin Bey Announces Retirement and Final Album

The

artist formerly known as Mos Def announced his retirement amid bitter

legal woes in South Africa. We should be saddened: Black culture is

better when Mos Def is part of it.

MOS DEF

Valery Hache/AFP/Getty

Hip-hop artist, singer and actor Yasiin Bey (formerly Mos Def) has been detained by South African authorities

after he attempted to leave the country to perform at a show in

Ethiopia—and the situation has apparently driven the artist to retire

from music and film entirely.

Bey moved to South Africa in 2013 as an American, but according to South Africa’s Department of Home Affairs, he and members of his family have overstayed their visa. Last week, Bey’s legal representative told OkayAfrica that the star was arrested for using a fraudulent document to travel—his “world passport.”

“From what I’ve read their allegations are wrong. He attempted to leave the country for a professional commitment and was denied the ability to board an airplane after providing his World Passport,” Bey’s rep stated.

“It’s issued by the World Service —in support of the UN Declaration of Human Rights. His understanding is that the South African government has previously accepted the World Passport to enter the country and to provide visas as recently as August.”

When asked if the rapper’s family had stayed past their visa term, the rep responded, “They may have stayed past their visa term, however, his arrest is because of the claim that he was allegedly using a false and fraudulent document.

“He considers himself a world citizen and wanted to to use his World Passport in support of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. Although South Africa did not sign the declaration in 1948—probably because they were governed by Apartheid at the time—Nelson Mandela believed it was a necessary document for the continued growth of South Africa after the abolishment of Apartheid.”

According to South African Home Affairs officials, Bey had 14 days to leave the country. But in a frustrated audio message posted on his longtime friend Kanye West’s official website, he says he was held “unlawfully.”

An emotional-sounding Yasiin kicks a freestyle called “No More Parties In S.A.” over the phone before offering his version of what’s going on.

“This is Yasiin Bey. At this present time, I am currently in Capetown, SA. I’m being prevented from leaving unjustly, unlawfully and without any logical reason,” he says. “They’re saying that they want to deport my family. They are making false claims against me, some of these government officials even in the press are making false claims against me. Saying that my travel document that I was traveling with is fictitious. It’s not. Anyone can do research on a world passport, it’s not a fictitious document. It’s not designed to deceive or rob any benefit from the state. In fact, the world passport has been accepted here on numerous occasions.”

Bey continues to voice his frustrations with how he and his family have been treated throughout the message.

“I am not a liar. I’ve made no false claims. I have not misrepresented myself. I’m under unnecessary state supervision and scrutiny.”

In 2013, Bey teamed with the human-rights group Reprieve and released a video reenactment of a force-feeding similar to the ones endured by hunger strikers jailed in Guantanamo Bay. He also spoke about the serenity he’d found living in South Africa.

“I lived in Brooklyn 33 years of my life. I thought I’d be buried in that place,” he told Rolling Stone that same year. “Around seven years ago, I was like, you know, ‘I gotta go, I gotta leave.’ It’s very hard to leave. And I lived in a lot of places. Central America. North America. Europe for a while.

“And I came to Cape Town in 2009, and it just hit me. I was like, ‘Yeah.’ I know when a good vibe gets to you. And, you know, I thought about this place every day from when I left. I was like, ‘I’m comin’ back.’”

“For a guy like me, who had five or six generations not just in America but in one town in America, to leave America, things gotta be not so good with America,” he said.

In 2014, Bey was forced to cancel a U.S. tour due to “immigration issues.”

An official statement from Boston’s Together Music Festival explained: “We regret to inform you that due to immigration/legal issues Yasiin Bey is unable to enter back into the United States and his upcoming US tour has been canceled.”

In yesterday’s message, Yasiin Bey made it clear that he feels he’s being targeted.

“I have reason to believe or suspect that there are political motivations behind the way that I’m being treated because this is following no reasonable strain of logic,” he wearily stated. “And it’s curious. I haven’t broken any law and I am being treated like a criminal. I know that I’m not unique in that regard and I’m grateful that I’m here with my family and I haven’t been physically harmed or anything like that. However, I have been detained and people in this state have taken punitive action against me. Unnecessarily.

“All I seek is to leave this state. I’m not looking to stake any future claims against them for damages or none of that. People can keep the little state jobs they’re concerned about losing.

“The state of South Africa is interfering with my ability to move or even fulfill my professional obligations. We don’t have to be enemies and we don’t have to be friends, either,” he continued. “We don’t have to be here. We’re complying in every possible way reasonably. Just today, state officials visited my domicile, asking questions about me and my family and they had no legal right to do so.”

Before signing off with a “thank you” to his friends and supporters, including West, Talib Kweli, Q-Tip, and the Zulu Nation, Bey also made the unexpected announcement that he was done with music and film.

“I’m retiring from the music recording industry as it is currently assembled today and also from Hollywood, effective immediately,” he said. “I’m releasing my final album this year and that’s that. Peace to all. Fear of none.

“All of the people who have supported me, this is no reflection on you,” he shared. “I love the people of this continent. I love this country. But I’m not going to sit idly by and be persecuted by the state.”

If the artist formerly known as Mos Def really is done—done with making music and film, done with voicing his creativity for the public, done with contributing to the landscape of hip-hop—then we should all be saddened. We should be saddened that an industry isn’t more conducive to nurturing the best of our creators. We should be saddened that a culture stifled that creativity to the point that he had to seek peace via nomadic existence. We should be saddened that an art form didn’t value him more. And we should do as much as we can to ensure that this generation of high-profile black creatives don’t get so frustrated with the industry and their audience that they, too, decide the best solution is to walk away.

When I was a young man in the late ’90s, I thought of Mos Def similarly to the way a generation of hip-hop fans view Kendrick Lamar now. He was passionate and thoughtful, he could rhyme his ass off and Black On Both Sides was an album that blew me away from the very first listen. I would start my days with “Umi Says” playing in the background and ride to work blasting “Ms. Fat Booty” and “Mathematics.” Mos Def became quieter and quieter in hip-hop as years passed, seemingly finding more solace in acting and activism. As a new generation of thoughtful emcees has emerged, maybe the weight of Yasiin Bey walking away won’t be immediately felt. Maybe he’d been gone for a long time already, and this just made it official. We don’t know all that has happened and is happening to him as he embarks on his unorthodox personal journey and it may not be for us to know. But contemporary black culture is better when Mos Def is a part of it. Here’s hoping Yasiin Bey finds his way home.

https://www.dazeddigital.com/music/article/20897/1/mos-def-vs-petite-noir

Bey moved to South Africa in 2013 as an American, but according to South Africa’s Department of Home Affairs, he and members of his family have overstayed their visa. Last week, Bey’s legal representative told OkayAfrica that the star was arrested for using a fraudulent document to travel—his “world passport.”

“From what I’ve read their allegations are wrong. He attempted to leave the country for a professional commitment and was denied the ability to board an airplane after providing his World Passport,” Bey’s rep stated.

“It’s issued by the World Service —in support of the UN Declaration of Human Rights. His understanding is that the South African government has previously accepted the World Passport to enter the country and to provide visas as recently as August.”

When asked if the rapper’s family had stayed past their visa term, the rep responded, “They may have stayed past their visa term, however, his arrest is because of the claim that he was allegedly using a false and fraudulent document.

“He considers himself a world citizen and wanted to to use his World Passport in support of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. Although South Africa did not sign the declaration in 1948—probably because they were governed by Apartheid at the time—Nelson Mandela believed it was a necessary document for the continued growth of South Africa after the abolishment of Apartheid.”

According to South African Home Affairs officials, Bey had 14 days to leave the country. But in a frustrated audio message posted on his longtime friend Kanye West’s official website, he says he was held “unlawfully.”

An emotional-sounding Yasiin kicks a freestyle called “No More Parties In S.A.” over the phone before offering his version of what’s going on.

“This is Yasiin Bey. At this present time, I am currently in Capetown, SA. I’m being prevented from leaving unjustly, unlawfully and without any logical reason,” he says. “They’re saying that they want to deport my family. They are making false claims against me, some of these government officials even in the press are making false claims against me. Saying that my travel document that I was traveling with is fictitious. It’s not. Anyone can do research on a world passport, it’s not a fictitious document. It’s not designed to deceive or rob any benefit from the state. In fact, the world passport has been accepted here on numerous occasions.”

Bey continues to voice his frustrations with how he and his family have been treated throughout the message.

“I am not a liar. I’ve made no false claims. I have not misrepresented myself. I’m under unnecessary state supervision and scrutiny.”

In 2013, Bey teamed with the human-rights group Reprieve and released a video reenactment of a force-feeding similar to the ones endured by hunger strikers jailed in Guantanamo Bay. He also spoke about the serenity he’d found living in South Africa.

“I lived in Brooklyn 33 years of my life. I thought I’d be buried in that place,” he told Rolling Stone that same year. “Around seven years ago, I was like, you know, ‘I gotta go, I gotta leave.’ It’s very hard to leave. And I lived in a lot of places. Central America. North America. Europe for a while.

“And I came to Cape Town in 2009, and it just hit me. I was like, ‘Yeah.’ I know when a good vibe gets to you. And, you know, I thought about this place every day from when I left. I was like, ‘I’m comin’ back.’”

“For a guy like me, who had five or six generations not just in America but in one town in America, to leave America, things gotta be not so good with America,” he said.

In 2014, Bey was forced to cancel a U.S. tour due to “immigration issues.”

An official statement from Boston’s Together Music Festival explained: “We regret to inform you that due to immigration/legal issues Yasiin Bey is unable to enter back into the United States and his upcoming US tour has been canceled.”

In yesterday’s message, Yasiin Bey made it clear that he feels he’s being targeted.

“I have reason to believe or suspect that there are political motivations behind the way that I’m being treated because this is following no reasonable strain of logic,” he wearily stated. “And it’s curious. I haven’t broken any law and I am being treated like a criminal. I know that I’m not unique in that regard and I’m grateful that I’m here with my family and I haven’t been physically harmed or anything like that. However, I have been detained and people in this state have taken punitive action against me. Unnecessarily.

“All I seek is to leave this state. I’m not looking to stake any future claims against them for damages or none of that. People can keep the little state jobs they’re concerned about losing.

“The state of South Africa is interfering with my ability to move or even fulfill my professional obligations. We don’t have to be enemies and we don’t have to be friends, either,” he continued. “We don’t have to be here. We’re complying in every possible way reasonably. Just today, state officials visited my domicile, asking questions about me and my family and they had no legal right to do so.”

Before signing off with a “thank you” to his friends and supporters, including West, Talib Kweli, Q-Tip, and the Zulu Nation, Bey also made the unexpected announcement that he was done with music and film.

“I’m retiring from the music recording industry as it is currently assembled today and also from Hollywood, effective immediately,” he said. “I’m releasing my final album this year and that’s that. Peace to all. Fear of none.

“All of the people who have supported me, this is no reflection on you,” he shared. “I love the people of this continent. I love this country. But I’m not going to sit idly by and be persecuted by the state.”

If the artist formerly known as Mos Def really is done—done with making music and film, done with voicing his creativity for the public, done with contributing to the landscape of hip-hop—then we should all be saddened. We should be saddened that an industry isn’t more conducive to nurturing the best of our creators. We should be saddened that a culture stifled that creativity to the point that he had to seek peace via nomadic existence. We should be saddened that an art form didn’t value him more. And we should do as much as we can to ensure that this generation of high-profile black creatives don’t get so frustrated with the industry and their audience that they, too, decide the best solution is to walk away.

When I was a young man in the late ’90s, I thought of Mos Def similarly to the way a generation of hip-hop fans view Kendrick Lamar now. He was passionate and thoughtful, he could rhyme his ass off and Black On Both Sides was an album that blew me away from the very first listen. I would start my days with “Umi Says” playing in the background and ride to work blasting “Ms. Fat Booty” and “Mathematics.” Mos Def became quieter and quieter in hip-hop as years passed, seemingly finding more solace in acting and activism. As a new generation of thoughtful emcees has emerged, maybe the weight of Yasiin Bey walking away won’t be immediately felt. Maybe he’d been gone for a long time already, and this just made it official. We don’t know all that has happened and is happening to him as he embarks on his unorthodox personal journey and it may not be for us to know. But contemporary black culture is better when Mos Def is a part of it. Here’s hoping Yasiin Bey finds his way home.

https://www.dazeddigital.com/music/article/20897/1/mos-def-vs-petite-noir

Text

Ignatius Mokone

Wikiquote has quotations related to:

Wikiquote has quotations related to:  Wikimedia Commons has media related to

Wikimedia Commons has media related to