SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2019

VOLUME SEVEN NUMBER TWO

HOLLAND DOZIER HOLLAND

(L-R: Lamont Dozier, Eddie Holland, Brian Holland)

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

SHIRLEY SCOTT

(June 15-21)

FREDDIE HUBBARD

(June 22-28)

BILL WITHERS

(June 29- July 5)

OUTKAST

(July 6-12)

J. J. JOHNSON

(July 13-19)

JIMMY SMITH

(July 20-26)

JACKIE WILSON

(July 27-August 2)

LITTLE RICHARD

(August 3-9)

KENNY BARRON

(August 10-16)

BLIND LEMON JEFFERSON

(August 17-23)

MOS DEF

(August 24-30)

BLIND BOY FULLER

(August 31-September 6)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/jimmy-smith-mn0000781172/biography

Jimmy Smith, byname of James Oscar Smith, (born Dec. 8, 1928, Norristown, Pa., U.S.—found dead Feb. 8, 2005, Scottsdale, Ariz.), American musician who integrated the electric organ into jazz, thereby inventing the soul-jazz idiom, which became popular in the 1950s and ’60s.

Smith grew up outside of Philadelphia. He learned to play piano from his parents and began performing with his father in a dance troupe at an early age. After serving in the navy he studied bass and piano at the Hamilton School of Music (1948) and the Ornstein School of Music (1949–50). He also toured (1951–54) with Don Gardner’s rhythm-and-blues group the Sonotones.

After hearing swing stylist Wild Bill Davis, one of the few organists in jazz, Smith was inspired to learn to play the Hammond organ. Earlier, players had used two-handed chords to make organs imitate the power of big bands; Smith’s innovation was to use the organ in the manner of horn players and bop pianists to play nimble single-note melodic lines accompanied by gospel music harmonies. In 1955 Smith formed a trio that became highly successful. That year, he began using the B3 model of the Hammond organ, which he was widely credited with popularizing. His series of hit albums, including A New Sound, A New Star: Jimmy Smith at the Organ, Vols. 1–2 (1956) and The Sermon! (1958), helped establish Blue Note as a major jazz record label.

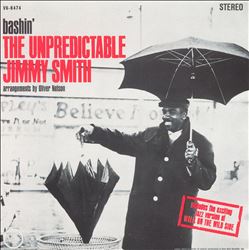

In the early 1960s, Smith began recording with Verve Records. His biggest hit was “Walk on the Wild Side,” from his Verve album Bashin’ (1962), on which he was accompanied by Oliver Nelson’s big studio band. Smith also recorded albums with guitarist Wes Montgomery and owned his own Los Angeles supper club during the 1970s. His 2001 album, Dot Com Blues, marked a departure from his customary jazz style, incorporating blues elements and showcasing collaborations with guest artists that included Etta James and B.B. King. Smith’s last album, Legacy (2005), was released posthumously and featured some of his greatest hits.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/jimmy-smith-master-of-the-hammond-b-3-jimmy-smith-by-mark-sabbatini.php

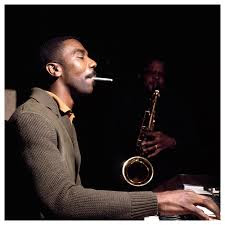

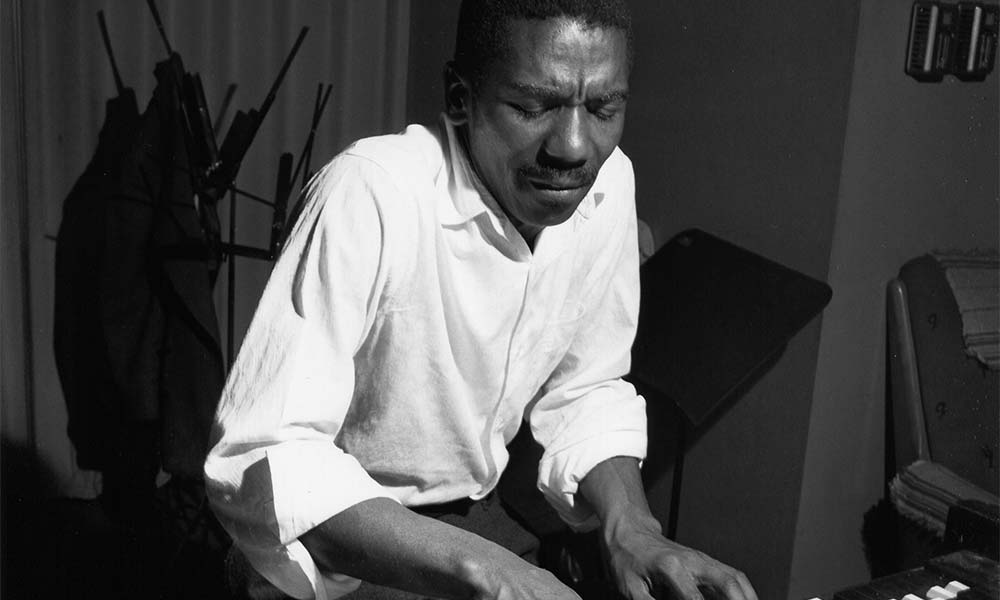

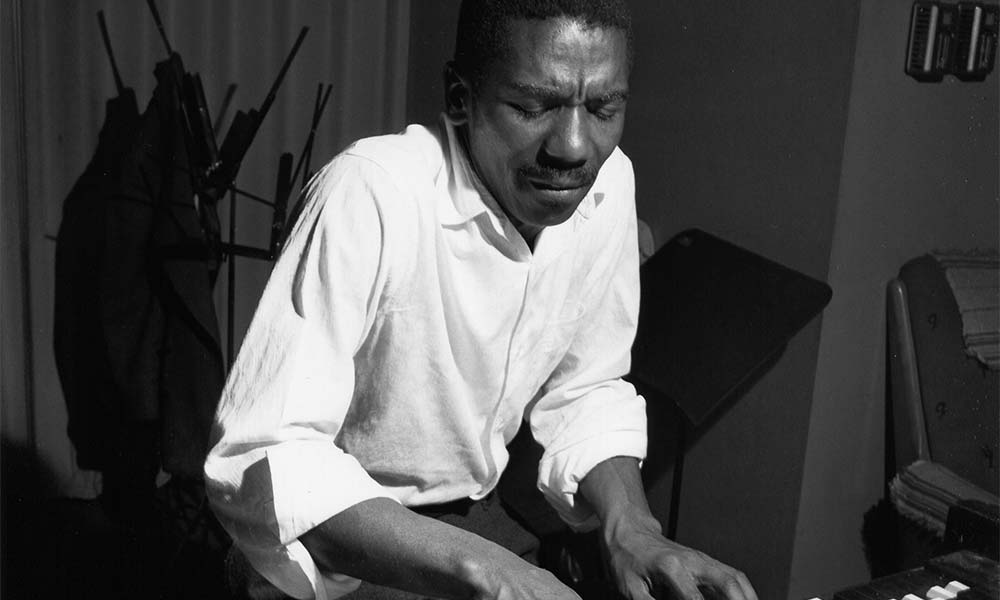

Photo: Francis Wolff/Mosaic Images

Photo: Francis Wolff/Mosaic Images

People way too often overlook Jimmy Smith today, and that’s been true for a far too long. His Hammond organ playing influenced just about everyone that followed him in jazz and in rock, and it is all too easy to downplay his achievements in taking the electric organ out of the lounges and bars and putting it centre stage, He broke down the barriers between the genres to get people listening to his Hammond B3. Jon Lord of Deep Purple acknowledged the influence of Smith, as did Peter Bardens, Brian Auger, Rick Wakeman and Keith Emerson. Without Smith, Booker T would not have developed his sound; he influenced Gregg Allman, and Greg Rolie of Santana.

The shock that people felt on hearing Jimmy’s Hammond organ in full flight is impossible to measure today. We’ve become so used to every kind of synthesised sound that we take for granted that with today’s keyboards we can make anything, sound like anything. When Jimmy came along his playing was revolutionary, but somehow or another it’s got overtaken by new technology, but let’s not let anything take away from what he achieved.

‘It took me two and a half weeks to find my sound and when I did I pulled out all the stops, all the stops I could find.’ – Jimmy Smith

James Oscar Smith’s father had a song-and-dance act in the local clubs, so it was perhaps no surprise that as a young boy his son took to the stage at six years old. Less usual though was that by the age twelve, he had taught himself, with occasional guidance from Bud Powell who lived nearby, to be an accomplished “Harlem Stride” pianist. He won local talent contests with his boogie-woogie piano playing and his future seemed set, but his father became increasingly unable to perform and turned to manual labour for income.

Smith left school to help support the family and joined the Navy when he was fifteen years old. With financial assistance from the G.I. Bill of Rights, set up in 1944 to help Second World War veterans rehabilitate, Smith was able to return to school in 1948, this time studying bass at the Hamilton School of Music in Philadelphia. At this point he was juggling school with working with his father and playing piano with several different R&B groups. It was in 1953 while playing piano with Don Gardener’s Sonotones that Smith heard Wild Bill Davis playing a Hammond organ and was inspired to switch to the electric organ.

His timing was perfect. As a kickback against the cool school, jazz was returning to its roots, leaning heavily on the blues and gospel that infused Smith’s upbringing. At the time, Laurens Hammond was improving his Hammond organ model A first introduced in 1935 by refining the specifications and downsizing it from two keyboards and an excess of foot pedals and drawbars, to the sleeker, more sophisticated B3 design.

Smith got his first B3 in 1953 and soon devised ways to navigate the complex machine: ‘When I finally got enough money for a down payment on my own organ I put it in a warehouse and took a big sheet of paper and drew a floor plan of the pedals. Anytime I wanted to gauge the spaces and where to drop my foot down on which pedal, I’d look at the chart. Sometimes I would stay there four hours or maybe all day long if I’d luck up on something and get some new ideas using different stops.’

His timing was perfect. As a kickback against the cool school, jazz was returning to its roots, leaning heavily on the blues and gospel that infused Smith’s upbringing. At the time, Laurens Hammond was improving his Hammond organ model A first introduced in 1935 by refining the specifications and downsizing it from two keyboards and an excess of foot pedals and drawbars, to the sleeker, more sophisticated B3 design.

Smith got his first B3 in 1953 and soon devised ways to navigate the complex machine: ‘When I finally got enough money for a down payment on my own organ I put it in a warehouse and took a big sheet of paper and drew a floor plan of the pedals. Anytime I wanted to gauge the spaces and where to drop my foot down on which pedal, I’d look at the chart. Sometimes I would stay there four hours or maybe all day long if I’d luck up on something and get some new ideas using different stops.’

Developing his playing style independent from any outside influence, by cutting himself off from the outside world for three months, was perhaps the key to his singular success. His technique, steeped in the gospel tradition, with rapid runs across the keyboard using the palm of his hand and quirky use of the pedals to punch out entire bass lines, was like nothing ever heard before; there is not a single organist since that does not acknowledge a debt to the incredible Jimmy Smith.

Smith began playing Philadelphia clubs in that same year, taking in a young John Coltrane for a short two-week stint at Spider Kelly’s, “It was Jimmy Smith for about a couple of weeks before I went with Miles – the organist. Wow! I’d wake up in the middle of the night, man, hearing that organ. Yeah, those chords screaming at me.” Remembers Coltrane.

Shortly afterwards Smith left Philly behind, heading for his New York debut. From his first gig in Harlem, it was patently obvious that this was something quite new, and it was not long before his novelty was attracting considerable attention, not least from the Blue Note label owner Alfred Lion, who offered him a record deal. Smith had almost instantaneous success with the presciently titled A New Sound… A New Star… This launched Smith’s hugely successful career, and gave Blue Note a much-needed income from a steady stream of albums over the next seven years. Albums such as The Sermon (1958), Prayer Meetin’ (1960) and Back at the Chicken Shack (1960) all secured the label hit jukebox singles: a rarity for many jazz artists.

Smith’s Blue Note sessions partnered him with Kenny Burrell, Art Blakey, Lee Morgan, Lou Donaldson, Stanley Turrentine, Jackie McLean and many others, before he move to Verve in 1962 where he immediately released a critical and commercial success in the form of Bashin’: The Unpredictable Jimmy Smith, which included the hit track ‘Walk On The Wild Side’. A song written by Elmer Bernstein, it was the title track to a movie. The album benefited greatly from the arranging skills of Oliver Nelson and ‘Walk On The Wild Side’ made No. 21 on the Billboard pop chart and was the biggest hit of his career.

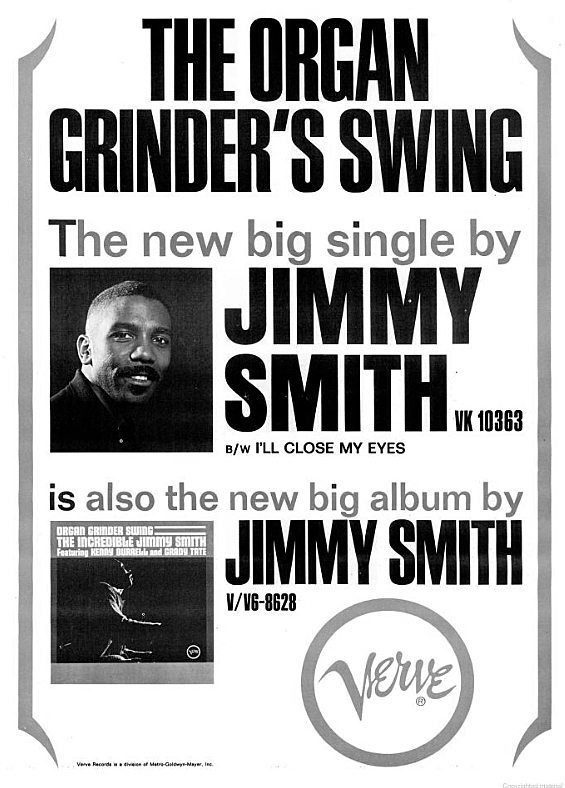

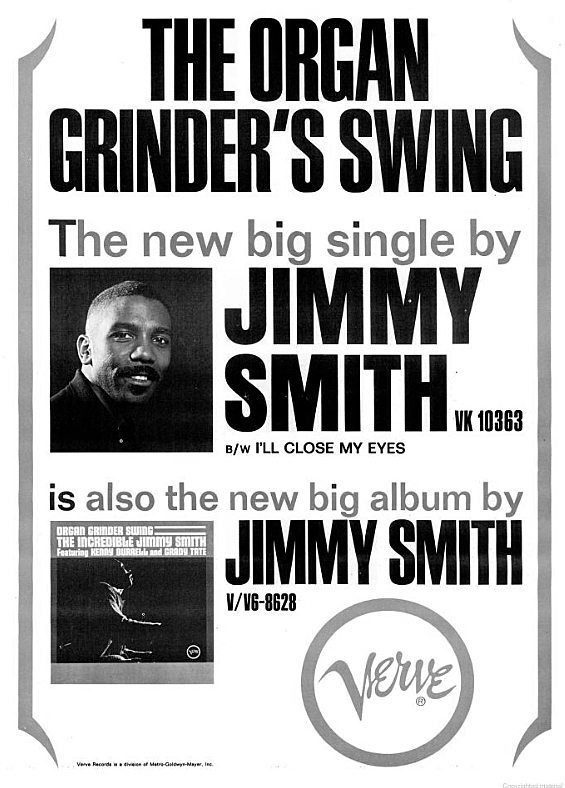

Bashin’… made the Billboard album chart in June 1962 climbing to No. 10, and for the next four years his albums rarely failed to chart. Among his biggest successes were Hobo Flats (1964), Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf (1964), The Cat (1964), Organ Grinder Swing (1965) and Jimmy & Wes – The Dynamic Duo (1967).

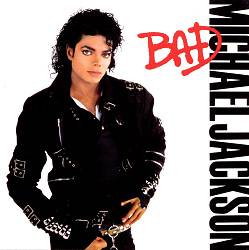

Following the last of a series of European tours in 1966, 1972 and 1975, rather than continuing to travel to play, Smith chose to settle down with his wife in the mid-1970s and run a supper club in California’s San Fernando Valley. Despite his regular performances, the club failed after only a few years, forcing a return to recording and frequent festival appearances, albeit not to the kind of acclaim that he had received previously. In fact, it wasn’t until the late 1980s that Smith produced several well-reviewed albums. He also received recognition for a series of live performances with fellow organ virtuoso Joey DeFrancesco, and his reinvigorated profile even led producer Quincy Jones to invite him to play on the sessions for Michael Jackson’s album, Bad in 1987; Smith plays the funky B3 solo on the title track and it went on for more than 20 minutes in the studio; it was edited on the final track to just over a minute. At the other end of the pop spectrum, he played on Frank Sinatra’s L.A. Is My Lady album in 1984 produced by Quincy Jones.

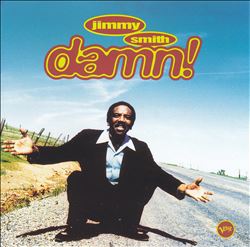

As his reputation grew again, Smith toured afar, playing with small groups in Japan, Europe and the United States, helped by hip-hop DJs spreading his name by sampling Smith’s funky organ grooves, exposing him to a new generation of fans through the Beastie Boys, Nas, Gang Starr, Kool G Rap and DJ Shadow. Returning to Verve in 1995, Smith recorded the album Damn! and Dot Com Blues in 2001, featuring legendary R&B stars, including Etta James, B. B. King, Keb’ Mo’, and Dr. John.

After moving to Scottsdale, Arizona, Smith died in 2005, less than a year after his wife. His final recording, “Legacy” with Joey DeFrancesco, was released posthumously. DeFrancesco dedicated the album, ‘To the master, Jimmy Smith—One of the greatest and most innovative musicians of all time.’ It’s time for a reappraisal of The Incredible Jimmy Smith who did as much to popularize jazz as almost any of his contemporaries.

https://www.jazzwax.com/2018/07/jimmy-smith-portuguese-soul.html

One of organist Jimmy Smith's most interesting experimental albums is Portuguese Soul. Recorded for Verve in February 1973, the album remains little known by many, largely because it was out of print for years. The album wasn't well-served by the cover's design, which looks like a horror film poster. Those who are new to the album may be surprised to learn that it was arranged by Thad Jones, who conducted a large orchestra whose members sadly were never listed on the back of the jacket and remain anonymous. [Photo above of Jimmy Smith by Francis Wolff © Mosaic Images]

As Smith writes in the album's liner notes, "It all started at 4 a.m., Sunday, November 13, 1972, after our segment of the Newport Jazz Festival had just wrapped up [along with] our last concert of the three-month European tour, in Cascals, a little town on the outskirts of Lisbon, Portugal. We were packed, and the other guys had crashed, but this guy was pacing with all sorts of music twisting my head, going in so many directions. I knew it couldn't be just another tune or two tunes, but a whole damn suite.

"I was rapping on tables, glasses, suitcases—anything that would get near the sounds I heard. I stayed on this 'musical high' for days and when I felt I had it all together, there was no doubt who the one man was who could musically dissect my brain, hear what was there and get on the same trip, and that was Thad Jones."

The music on the album is fascinating. The recording opens with Don McLean's And I Love You So, which Smith first heard in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. He missed the first verse and song's title before he was able to turn on his tape recorder, but he says in the notes he managed to capture enough of it to know he had to record it. Next up is Blap, a 10:53 original that must have come from the banging on tables and glasses. It completes Side 1.

On Side 2, there's a four-minute opening instrumental prologue. Next come three movements that finish the album. The first and third movements are by Smith while the second is by Jones. What's fascinating about this album is that the music is heavily perfumed by Jones's expansive orchestral arranging style punctuated by Smith's organ ruminations throughout. It's also deeply complex and moody music.

What's unfortunate is that the musicians on the date aren't listed. Saxophonist Bill Kirchner, who knew Thad Jones and sat in with Mel Lewis Band and the Jazz Orchestra in the 1980s, told me the following:

"The band is the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Big Band, but with Grady Tate on drums and Mel on percussion. On one movement, there are two tenor solos, by Billy Harper and Ron Bridgewater, the band’s two tenor players at the time. My educated guess is that Jimmy probably insisted on Grady (who did most if not all of Smith’s big band albums) playing drums, so out of respect for Mel, they didn’t identify the band as the Jones-Lewis band. But it’s only a guess."

If I have time, I'll see if New York's Local 802 has the session sheets.

Jimmy Smith died in 2005:

JazzWax tracks: Fortunately, Jimmy Smith's Portuguese Soul is available as a download for only $6.99 here.

The album also is available at Spotify.

JazzWax clip: Here's And I Love Her So...

https://www.nytimes.com/2005/02/10/arts/music/jimmy-smith-jazz-organist-and-pioneer-is-dead-at-76.html

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2005/feb/11/guardianobituaries.artsobituaries

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jimmy_Smith_(musician)

James Oscar Smith (December 8, 1925 or 1928[1][1] – February 8, 2005)[2] was an American jazz musician whose albums often charted on Billboard magazine. He helped popularize the Hammond B-3 organ, creating a link between jazz and 1960s soul music.

In 2005, Smith was awarded the NEA Jazz Masters Award from the National Endowment for the Arts, the highest honor that America bestows upon jazz musicians.[3]

Smith signed to the Verve label in 1962. His first album, Bashin', sold well and for the first time set Smith with a big band, led by Oliver Nelson. Further big band collaborations followed, most successfully with Lalo Schifrin for The Cat and guitarist Wes Montgomery, with whom he recorded two albums: The Dynamic Duo and Further Adventures of Jimmy and Wes. Other albums from this period include Blue Bash! and Organ Grinder Swing with Kenny Burrell, The Boss with George Benson, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Got My Mojo Working, and Hoochie Coochie Man.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Smith recorded with some of the great jazz musicians of the day such as Kenny Burrell, George Benson, Grant Green, Stanley Turrentine, Lee Morgan, Lou Donaldson, Tina Brooks, Jackie McLean, Grady Tate and Donald Bailey.

The Jimmy Smith Trio performed "When Johnny Comes Marching Home" and "The Sermon" in the 1964 film Get Yourself a College Girl.

In the 1970s, Smith opened his own supper club in the North Hollywood neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, at 12910 Victory Boulevard and played there regularly with Kenny Dixon on drums, Herman Riley and John F. Phillips on saxophone; also included in the band was harmonica/flute player Stanley Behrens. The 1972 album Root Down, considered a seminal influence on later generations of funk and hip-hop musicians, was recorded live at the club, albeit with a different group of backing musicians.

Smith had a career revival in the 1980s and 1990s, again recording for Blue Note and Verve, and for Elektra and Milestone. He also recorded with Quincy Jones, Frank Sinatra, Michael Jackson (he can be heard on the title track of the Bad album), Dee Dee Bridgewater, and Joey DeFrancesco. His last album, Dot Com Blues (Blue Thumb/Verve, 2001) was recorded with B. B. King, Dr. John, and Etta James.

Smith and his wife moved to Scottsdale, Arizona, in 2004. She died of cancer a few months later. Smith recorded Legacy with Joey DeFrancesco, and the two prepared to go on tour.[8] However, before the tour began, Smith died on February 8, 2005 at his Scottsdale home where he was found by his manager, Robert Clayton. He died in his sleep of natural causes.[9]

While the electric organ had been used in jazz by Fats Waller, Count Basie, Wild Bill Davis and others, Smith's virtuoso improvisation technique on the Hammond helped to popularize the electric organ as a jazz and blues instrument. The B3 and companion Leslie speaker

produce a distinctive sound, including percussive "clicks" with each

key stroke. The drawbar setting most commonly associated with Smith is

to pull out the first three drawbars on the "B" preset on the top manual

of the organ, with added harmonic percussion on the 3rd harmonic. This

tone has been emulated by many jazz organists since Smith. Smith's style

on fast tempo pieces combined bluesy "licks" with bebop-based

single note runs. For ballads, he played walking bass lines on the

bass pedals. For uptempo tunes, he would play the bass line on the lower

manual and use the pedals for emphasis on the attack of certain notes,

which helped to emulate the attack and sound of a string bass.

Smith influenced a constellation of jazz organists, including Jimmy McGriff, Brother Jack McDuff, Don Patterson, Richard "Groove" Holmes, Joey DeFrancesco, Tony Monaco and Larry Goldings, as well as rock keyboardists such as Jon Lord, Brian Auger and Keith Emerson. Later, he influenced bands such as Medeski, Martin & Wood and the Beastie Boys, who sampled the bassline from "Root Down (and Get It)" from Root Down—and saluted Smith in the lyrics—for their own hit "Root Down". Often called the father of acid jazz, Smith lived to see that movement come to reflect his organ style. In the 1990s, Smith went to Nashville, taking a break from his ongoing gigs at his Sacramento restaurant which he owned and, in Music City, Nashville, he produced, with the help of a webmaster, Dot Com Blues, his last Verve album. In 1999, Smith guested on two tracks of a live album, Incredible! (the hit from the 1960s) with his protégé, Joey DeFrancesco, a then 28-year-old organist. Smith and DeFrancesco's collaborative album Legacy was released in 2005 shortly after Smith's death.[10]

Verve

Milestone

Other labels

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/jimmy-smith-mn0000781172/biography

Jimmy Smith

(1928-2005)

Artist Biography by Mark Deming

Jimmy Smith wasn't the first organ player in jazz, but no one had a greater influence with the instrument than he did; Smith

coaxed a rich, grooving tone from the Hammond B-3, and his sound and

style made him a top instrumentalist in the 1950s and '60s, while a

number of rock and R&B keyboardists would learn valuable lessons

from Smith's example.

James Oscar Smith was born in Norristown, Pennsylvania on December 8, 1925 (some sources cite his birth year as 1928). Smith's father was a musician and entertainer, and young Jimmy joined his song-and-dance act when he was six years old. By the time he was 12, Smith

was an accomplished stride piano player who won local talent contests,

but when his father began having problems with his knee and gave up

performing to work as a plasterer, Jimmy quit school after eighth grade and began working odd jobs to help support the family. At 15, Smith

joined the Navy, and when he returned home, he attended music school on

the GI Bill, studying at the Hamilton School of Music and the Ornstein

School, both based in Philadelphia.

In 1951, Smith

began playing with several R&B acts in Philadelphia while working

with his father during the day, but after hearing pioneering organ

player Wild Bill Davis, Smith was inspired to switch instruments. Smith bought a Hammond B-3 organ and set up a practice space in a warehouse where he and his father were working; Smith

refined the rudiments of his style over the next year (informed more

closely by horn players than other keyboard artists, and employing

innovative use of the bass pedals and drawbars), and he began playing

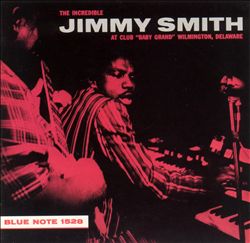

Philadelphia clubs in 1955. In early 1956, Smith made his New York debut at the legendary Harlem nightspot Small's Paradise, and Smith was soon spotted by Alfred Lion, who ran the well-respected jazz label Blue Note Records. Lion signed Smith to a record deal, and between popular early albums such as The Incredible Jimmy Smith at Club Baby Grand and The Champ and legendary appearances at New York's Birdland and the Newport Jazz Festival, Smith became the hottest new name in jazz.

A prolific recording artist, Smith recorded more than 30 albums for Blue Note between 1956 and 1963, collaborating with the likes of Kenny Burrell, Stanley Turrentine, and Jackie McLean, and in 1963, Smith signed a new record deal with Verve. Smith's first album for Verve, Bashin': The Unpredictable Jimmy Smith, was a critical and commercial success, and the track "Walk on the Wild Side" became a minor hit. Smith

maintained his busy performing and recording schedule throughout the

1960s, and in 1966 he cut a pair of celebrated album with guitarist Wes Montgomery. In 1972, Smith's

contract with Verve expired, and tired of his demanding tour schedule,

he and his wife opened a supper club in California's San Fernando

Valley. Smith performed regularly at the club, but it went out of business after only a few years. While Smith continued to record regularly for a variety of labels, his days as a star appeared to be over.

However, in the late '80s, Smith began recording for the Milestone label, cutting several well-reviewed albums that reminded jazz fans Smith was still a master at his instrument, as did a number of live performances with fellow organ virtuoso Joey DeFrancesco. In 1987, producer Quincy Jones invited Smith to play on the sessions for Michael Jackson's album Bad. And Smith found a new generation of fans when hip-hop DJs began sampling Smith's funky organ grooves; the Beastie Boys famously used Smith's "Root Down (And Get It)" for their song "Root Down," and other Smith performances became the basis for tracks by Nas, Gang Starr, Kool G Rap, and DJ Shadow.

In 1995, Smith returned to Verve Records for the album Damn!, and on 2001's Dot Com Blues, Smith teamed up with a variety of blues and R&B stars, including Etta James, B.B. King, Keb' Mo', and Dr. John. In 2004, Smith was honored as a Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts; that same year, Smith relocated from Los Angeles to Scottsdale, Arizona. Several months after settling in Scottsdale, Smith's wife succumbed to cancer, and while he continued to perform and record, Jimmy Smith was found dead in his home less than a year later, on February 8, 2005. His final album, Legacy, was released several months after his passing.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/jimmysmith

Born James Oscar Smith in Norristown, Pennsylvania, USA. Smith was influenced by both gospel and blues. He first achieved prominence in the 1950s where his recordings became popular on jukeboxes before there were commonly used terms to describe his unique musical flavor. In the sixties and seventies he helped create the jazz style known as 'funk' or 'soul jazz'.

There had been earlier limited use of the electronic organ in jazz (notably by Fats Waller and Count Basie), though these early examples sometimes had a novelty feel. Smith is widely recognized as introducing the electric organ as a legitimate musical instrument, capable of virtuoso improvisation.

Smith employed a unique technique to emulate a string bass player on the organ. Although he played walking bass lines on the pedals on ballads, for uptempo tunes, he would play the bass line on the lower manual and use the pedals for emphasis on the attack of certain notes. His solos were characterised by percussive chords mixed with very fast melodic improvisation with the right hand. He generally used a drawbar registration of 868000000 or 888000000 on the lower manual, which he used for the bass line and comping chords. He used a similar registration on the upper manual, which he used for soloing, but with the addition of the Hammond's percussion circuit.

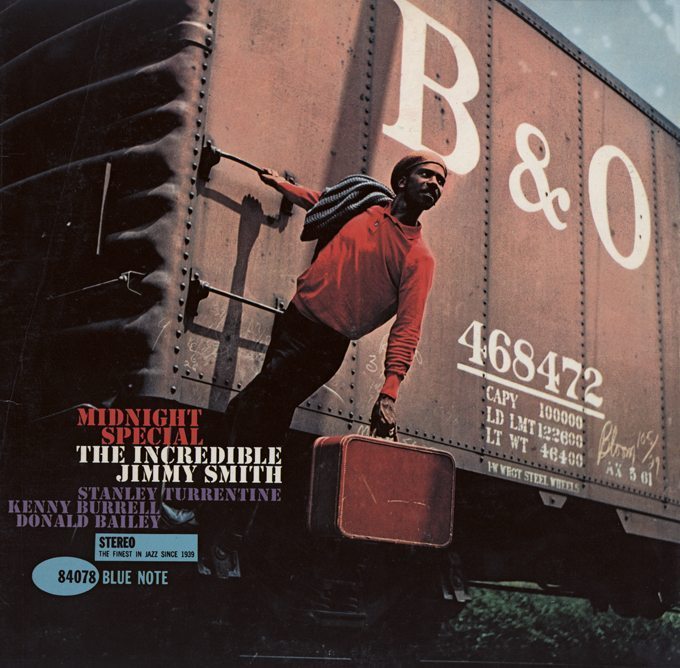

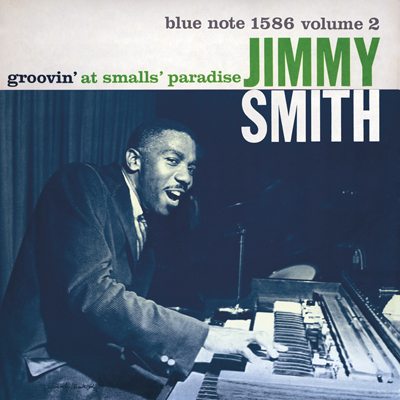

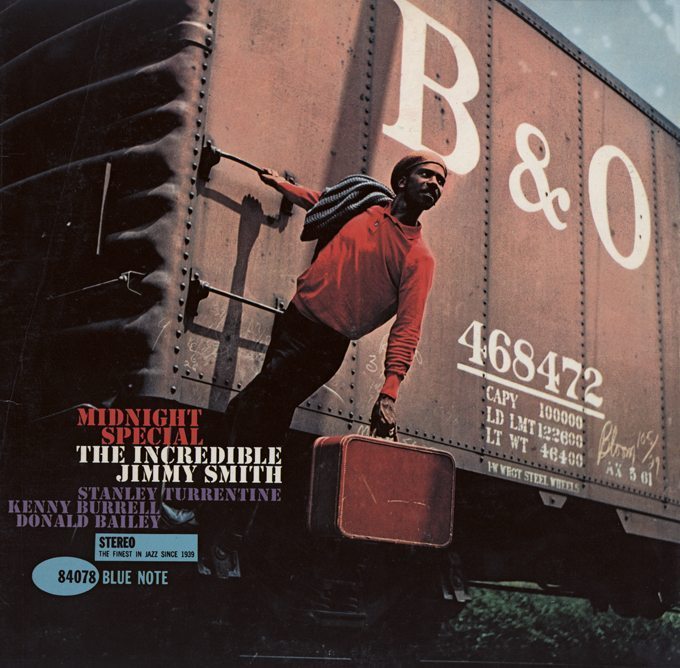

Smith was a prolific recording artist. He first recorded with the Blue Note label in 1956. His early albums with Blue Note sold very well, improving its financial viability and aiding the label's efforts to promote other artists. They include Home Cookin' , The Sermon!, Midnight Special, Prayer Meetin' , and Back at the Chicken Shack.

Smith signed to Verve Records label in 1963. Smith's albums with Verve include: The Cat, The Boss, Root Down, Peter & The Wolf, Any Number Can Win, The Incredible..., Bashin' , Got My Mojo Workin' , Christmas Cookin' , and Organ Grinder Swing.

It was in this period that he began a regular collaboration with Guitarist Wes Montgomery, with whom he recorded two albums: The Dynamic Duo with Wes Montgomery and Further Adventures Of Jimmy and Wes.

Smith recorded with a full orchestra and worked with arrangers and conductors such as Lalo Schifrin and Oliver Nelson. He also worked in small groups that featured many of the best jazz musicians of his era: Kenny Burrell, Donald “Duck” Bailey, Grady Tate, Lee Morgan, Lou Donaldson, Tina Brooks, Jackie McLean and Stanley Turrentine among them.

Smith had a career revival in the 'eighties and 'nineties, again recording for Blue Note and Verve, as well as for the Milestone label. There are also numerous recordings with other artists available including: Love And Peace: A Tribute To Horace Silver with Dee Dee Bridgewater (1995) and Blue Bash! with Kenny Burrell (1963).

His influence has been felt across multiple generations and musical styles; nearly every subsequent jazz organist owes a large debt to Smith. The Beastie Boys (who sampled the bassline from Smith's “Root Down (and Get It)””and saluted Smith in the lyrics”for their own hit “Root Down”), Medeski, Martin & Wood, and The Hayden-Eckert Ensemble are among the better known contemporary bands that pay tribute to Smith's sensibilities and sound. The Acid Jazz movement also reflects Smith's influences.

Smith died on February 8, 2005, in Scottsdale, Arizona, USA.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jimmy-Smith

Jimmy Smith

Jimmy Smith

Born James Oscar Smith in Norristown, Pennsylvania, USA. Smith was influenced by both gospel and blues. He first achieved prominence in the 1950s where his recordings became popular on jukeboxes before there were commonly used terms to describe his unique musical flavor. In the sixties and seventies he helped create the jazz style known as 'funk' or 'soul jazz'.

There had been earlier limited use of the electronic organ in jazz (notably by Fats Waller and Count Basie), though these early examples sometimes had a novelty feel. Smith is widely recognized as introducing the electric organ as a legitimate musical instrument, capable of virtuoso improvisation.

Smith employed a unique technique to emulate a string bass player on the organ. Although he played walking bass lines on the pedals on ballads, for uptempo tunes, he would play the bass line on the lower manual and use the pedals for emphasis on the attack of certain notes. His solos were characterised by percussive chords mixed with very fast melodic improvisation with the right hand. He generally used a drawbar registration of 868000000 or 888000000 on the lower manual, which he used for the bass line and comping chords. He used a similar registration on the upper manual, which he used for soloing, but with the addition of the Hammond's percussion circuit.

Smith was a prolific recording artist. He first recorded with the Blue Note label in 1956. His early albums with Blue Note sold very well, improving its financial viability and aiding the label's efforts to promote other artists. They include Home Cookin' , The Sermon!, Midnight Special, Prayer Meetin' , and Back at the Chicken Shack.

Smith signed to Verve Records label in 1963. Smith's albums with Verve include: The Cat, The Boss, Root Down, Peter & The Wolf, Any Number Can Win, The Incredible..., Bashin' , Got My Mojo Workin' , Christmas Cookin' , and Organ Grinder Swing.

It was in this period that he began a regular collaboration with Guitarist Wes Montgomery, with whom he recorded two albums: The Dynamic Duo with Wes Montgomery and Further Adventures Of Jimmy and Wes.

Smith recorded with a full orchestra and worked with arrangers and conductors such as Lalo Schifrin and Oliver Nelson. He also worked in small groups that featured many of the best jazz musicians of his era: Kenny Burrell, Donald “Duck” Bailey, Grady Tate, Lee Morgan, Lou Donaldson, Tina Brooks, Jackie McLean and Stanley Turrentine among them.

Smith had a career revival in the 'eighties and 'nineties, again recording for Blue Note and Verve, as well as for the Milestone label. There are also numerous recordings with other artists available including: Love And Peace: A Tribute To Horace Silver with Dee Dee Bridgewater (1995) and Blue Bash! with Kenny Burrell (1963).

His influence has been felt across multiple generations and musical styles; nearly every subsequent jazz organist owes a large debt to Smith. The Beastie Boys (who sampled the bassline from Smith's “Root Down (and Get It)””and saluted Smith in the lyrics”for their own hit “Root Down”), Medeski, Martin & Wood, and The Hayden-Eckert Ensemble are among the better known contemporary bands that pay tribute to Smith's sensibilities and sound. The Acid Jazz movement also reflects Smith's influences.

Smith died on February 8, 2005, in Scottsdale, Arizona, USA.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jimmy-Smith

Jimmy Smith

American musician

Jimmy Smith, byname of James Oscar Smith, (born Dec. 8, 1928, Norristown, Pa., U.S.—found dead Feb. 8, 2005, Scottsdale, Ariz.), American musician who integrated the electric organ into jazz, thereby inventing the soul-jazz idiom, which became popular in the 1950s and ’60s.

Smith grew up outside of Philadelphia. He learned to play piano from his parents and began performing with his father in a dance troupe at an early age. After serving in the navy he studied bass and piano at the Hamilton School of Music (1948) and the Ornstein School of Music (1949–50). He also toured (1951–54) with Don Gardner’s rhythm-and-blues group the Sonotones.

After hearing swing stylist Wild Bill Davis, one of the few organists in jazz, Smith was inspired to learn to play the Hammond organ. Earlier, players had used two-handed chords to make organs imitate the power of big bands; Smith’s innovation was to use the organ in the manner of horn players and bop pianists to play nimble single-note melodic lines accompanied by gospel music harmonies. In 1955 Smith formed a trio that became highly successful. That year, he began using the B3 model of the Hammond organ, which he was widely credited with popularizing. His series of hit albums, including A New Sound, A New Star: Jimmy Smith at the Organ, Vols. 1–2 (1956) and The Sermon! (1958), helped establish Blue Note as a major jazz record label.

In the early 1960s, Smith began recording with Verve Records. His biggest hit was “Walk on the Wild Side,” from his Verve album Bashin’ (1962), on which he was accompanied by Oliver Nelson’s big studio band. Smith also recorded albums with guitarist Wes Montgomery and owned his own Los Angeles supper club during the 1970s. His 2001 album, Dot Com Blues, marked a departure from his customary jazz style, incorporating blues elements and showcasing collaborations with guest artists that included Etta James and B.B. King. Smith’s last album, Legacy (2005), was released posthumously and featured some of his greatest hits.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/jimmy-smith-master-of-the-hammond-b-3-jimmy-smith-by-mark-sabbatini.php

Jimmy Smith: Master of the Hammond B-3

by

Jimmy Smith ignited a jazz revolution on an instrument associated at

the time with ballparks, despite never playing one until the age of 28.

His legendary multi-part technique on the Hammond B-3 organ, playing bass with the foot pedals and Charlie Parker-like single-line passages with his right hand, shook up the traditional trio as co-players could explore new roles. Yet, while the consensus is Smith's playing is a jazz landmark, his recordings fall short of such acclaim.

Not a single album is listed among the 200 most important recordings in the book Essential Jazz Library by New York Times critic Ben Ratcliff. The Penguin Guide To Jazz On CD notes "it was disappointing... to hear how quickly Smith's albums become formulaic." Rolling Stone calls much of his late career work "substandard."

The joy in building a Smith collection is one can almost always count on his worthwhile albums being fun, fast, and spiritual blues romps with lots of his patented tonal color.

The drawback is... pretty much the same thing.

There's a sameness to much of his work, and many of his "outside the box" efforts into genres such as fusion and soundtracks are less than stellar. Adding to this discouragement is a number of his best early albums are out of print.

Still, it's hard to dispute the more than 100 albums in Smith's discography feature not only a rich collection of commercially popular music, but works of exceptional artistry.

Other players such as Count Basie experimented with the organ as far back as the 1930s, but Smith pioneered the fusion of R&B, gospel and jazz in addition to his unique playing style. He was an enormous success almost immediately and, following a commercial and critical lull during the 1970s and '80s, rebounded with several quality late-career recordings and saw his work influence artists from organist Joey DeFrancesco to hip-hop and jam bands incorporating digital samples of Smith's playing into their performances.

He died February 8, 2005, in his sleep at the age of 76 at his Scottsdale, Arizona, home.

"Jimmy was one of the greatest and most innovative musicians of our time," wrote DeFrancesco in a message at his Web site dated February 9, 2005, six days before the release of Legacy, his second album recorded with Smith. "I loved the man and I love the music. He was my idol, my mentor and my friend."

Smith was born in 1928 in Norristown, Pa., near Philadelphia, to a musically inclined family that saw him playing piano and bass as a youth. This combination proved an essential element of his one-man-band approach on the organ. He joined the Navy at age 15 to escape his hometown and after World War II studied at several Philadelphia music schools. He subsequently played piano for local R&B groups during the 1940s and 50s.

He explains his development on the organ in an oft-quoted interview:

"I got my organ from a loan shark and had it shipped to the warehouse," he said. "I stayed in that warehouse, I would say, six months to a year. I would do just like the guys do—take my lunch, then I'd go and set down at this beast. Nobody showed my anything, man, so I had to fiddle around with my stops."

His New York debut came in 1956 with Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers and the organist was an almost immediate hit.

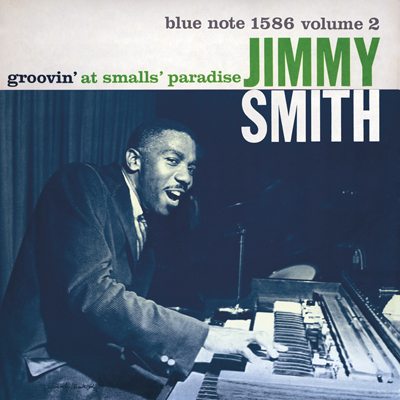

Smith's early recordings were so successful Blue Note set up a special division to develop the genre he formed. He typically recorded numerous projects every year for the label between the late 1950s and his departure in 1962, including career highlights such as 1957s Groovin At Small's Paradise and 1960s Back At The Chicken Shack, perhaps his best-known album. Many are also noteworthy for all-star rosters of co-players such as guitarist Kenny Burrell, trumpeter Blue Mitchell, and saxophonists Stanley Turrentine and Jackie McLean.

His association with Verve Records beginning in 1962 saw both an expansion and limitation of his work. Among the most successful were a pair of albums recorded with guitarist Wes Montgomery and 1962's Bashin': The Unpredictable Jimmy Smith, with "Walk On The Wild Side" from the latter album making pop charts as a single.

However, new formats such as big bands often featured something other than the lengthy blowing sessions best suited to his strength of building up passages over time. Many also sought crossover audiences—toying, for instance, with show tunes and hard rock—and are frequently considered weak points of his discography.

Smith's struggles continued during the 1970s as synthesizers caused the B-3 to fall out of audience favor. He toured regularly until 1975, when he opened a Los Angeles jazz club with his wife, Lola. Recordings and appearances became infrequent and undistinguished until the early 1980s and, while many subsequent recordings are quality dates, the frequency of new albums continued to be sparse. Later-career highlights include two albums from a 1990 live reunion with Burrell and Turrentine (Fourmost and Fourmost Return), and the live 1999 Incredible! collaboration with DeFrancesco.

A revival of interest in the B-3 sound also resulted in Smith's music influencing and being performed by a wide range of players such as John Medeski and the Beastie Boys (noteworthy for their use of "Root Down"). The elder organist, who Miles Davis once proclaimed the "eighth wonder of the world," also reemerged as a popular performer, including weekly jam sessions with DeFrancesco during the years preceding his death.

"He had a spirit and a sound that comes across, and there was nothing like it," DeFrancesco said in a newspaper interview. "He was full of fire and soul, just the complete musician."

Albums

New listeners looking for a single get-acquainted album can't go wrong with the 1960 "classic? Back At The Chicken Shack , although some consider 1958's The Sermon and 1960's Crazy! Baby superior. Best of all may be 1957's live Groovin' At Small's Paradise if the budget allows for a double-disc.

Those looking for a good career retrospective might first consider the four-disc Retrospective featuring Blue Note highlights from the 1950s and '60s. A supplemental, or less expensive alternative, is the two-disc Walk On The Wild Side: The Best Of The Verve Years. An in-depth career-spanning boxed set remains elusive.

Groovin' At Small's Paradise (1957)

Perhaps the best of his initial albums currently in release, this live double-CD Blue Note collection with guitarist Eddie McFadden and drummer Donald Bailey plays heavily to Smith's strengths. There's a mix of standards, jazz and blues, mostly extended enough in length to allow the organist sufficient room for development. Some early pieces such as "My Funny Valentine" are more restrained than subsequent romps such as the widely acclaimed "After Hours."

The Sermon (1958)

Another strong early effort in a relatively straight-ahead vein, especially for those looking to hear Smith with a variety of players outside his familiar trio format. Among those on the all-star list are trumpeter Lee Morgan, guitarists Kenny Burrell and Eddie McFadden, alto saxophonists George Coleman and Lou Donaldson, and drummer Art Blakey. A reissued disc adds five tracks to the original three extended-length songs.

Crazy! Baby (1960)

There are two solid positives on this album: 1) he plays with his regular trio of guitarist Quentin Warren and drummer Donald Bailey instead of "name? players and 2) the opportunity, especially for newcomers to his music, to hear him play accessibly and yet with classic flair on familiar tunes such as "When Johnny Comes Marching Home" and "Makin' Whoopie." Not all agree: the Penguin guide calls it "discouragingly rational" and ranks it one of his two worst Blue Note recordings.

Back At The Chicken Shack (1960)

A stellar album, although its rank as the pinnacle of Smith's discography can be disputed. Smith is in high form on the roaring title track as well as standards such as "On The Sunny Side Of The Street," but his co-players score some of the most notable accomplishments. Tenor saxophonist Stanley Turrentine delivers what many consider the breakthrough performance of his career and guitarist Kenny Burrell provides a smooth counterpresence to the organist's madness. Both would still be playing with him decades later on some of his best late-career work.

Prayer Meetin' (1963)

This was Smith's final Blue Note recording until 1986. It was also the fourth album he recorded in a week as, eager to move to the Verve label, he put out a rush of albums to fulfill his existing contract. Even so, this is a quality work highlighted by Turrentine's tenor. Items of note include the rare inclusion of a bassist (Sam Jones) and two bonus tracks from the Chicken Shack era ("Lonesome Road" and "Smith Walk").

Jimmy And Wes: The Dynamic Duo (1966)

Interestingly, a number of critics refer to Smith's best musical partners providing a subtle ying to his intense yang. This big band-aided collaboration is among his most notable, as he and guitarist Wes Montgomery are as mismatched and yet strangely compatible as The Odd Couple, although a few apparent "crowd pleasers" are real clunkers ("Baby It's Cold Outside" is frequently cited). A second album from the session is The Further Adventures Of Jimmy And Wes.

Peter And The Wolf (1966)

Included with the disclaimer some critics rank this among the least of Smith's works ( All Music Guide's Scott Yanow is a notable exception) and it's probably accurate to say the playing is hardly his best. But since many of those same critics attack the sameness of his work and the concept of a jazz interpretation of these children's compositions is intriguing, this is as good a way as any to experience him "outside the box." Smith keeps the compositions recognizable, but with liberal doses of his own accent which are easy to distinguish given the simple and widely-known frame of reference.

Root Down (1972)

This Verve release is perhaps best-known for the Beastie Boys' cover of the title track in 1994, but also ranks as one of the strongest entries in Smith's work for the label. This live performance in Los Angeles is heavy on funk, supported by younger players such as Steve Williams on harmonica, Arthur Adams on guitar and Wilton Felder on bass. Smith's playing is generally raw and energetic—a refreshing change from arranged big band—especially on cuts such as "For Everyone Under The Sun."

Fourmost and Fourmost Return (1990)

Some of Smith's best late-career playing comes on this pair of discs recorded live with Turrentine, Burrell and drummer Grady Tate. The long-form arrangements ranging from standard ballads such as "My Funny Valentine" to the storming of a revived "Back At The Chicken Shack" suit the players well. Smith also contributes some scratchy vocals on "Ain't She Sweet" which, if accepted as the audience-pleaser they are, make for an entertaining extra.

Incredible! (1999)

This live performance is really more of a Joey DeFrancesco album, with Smith joining the younger organist for the final half of the hour-long set. But hearing the evolution of Smith's influence through DeFrancesco is reason enough to make this worthwhile, and it's intriguing to hear their two extended duets evolve into differing compositions (the titles, such as "Medley, No. 1: The Reverend/Yesterdays/ My Romance" are self-explanatory). The results may be audience-pleasing than artistic, but there's no denying both sound like they're having fun and generally complimenting each other well while doing so.

Boxed Sets/Compilations

Retrospective

This four-disc, 38-song collection representing Smith's Blue Note work from 1956 to 1963 is an excellent overview for listeners not attached to individual albums. Highlights include his 1956 performance of Dizzy Gillespie's "The Champ," the emerging freeform with Art Blakey on "The Duel," and a number of famous pieces such as "The Sermon? and "Incredible." Expanding the collection to include some of his "comeback" Blue Note work during the 1980s and '90s would be welcome, but they didn't reach the peaks Smith achieved during the earliest parts of his career.

Walk On The Wild Side: The Best Of The Verve Years (1962-73)

This 25-song, two-disc collection features many of his most popular songs, including the title track and some works with Wes Montgomery. It also features a range of small and large ensembles, making it more varied than the Blue Note collection. But the overall level of playing is less accomplished and it's a much less satisfactory listen for those seeking a truly representative overview of Smith's highlights and career. Still, it's a far superior choice to single-disc Verve compilations such as Ultimate Jimmy Smith and Jimmy Smith's Finest Hour, which contain too many overlapping tracks and lack significant depth.

DVD

Jazz Scene USA—Phineas Newborn Jr. and Jimmy Smith (1962)

There aren't a lot of Smith performances on DVD, but he puts on an impressive three-song trio performance with Quentin Warren and Donald Bailey during their half of this 60-minute Jazz Scene USA program. The casual, short-lived TV series does a fine job capturing Smith's technique on camera and the rendition of "Walk On The Wild Side" builds to a frenzy worthy of its title. Pianist Phineas Newborn Jr.'s performance on the other half of the disc came during a peak time in his career, a nice bonus.

https://www.udiscovermusic.com/stories/the-incredible-and-influential-jimmy-smith/

His legendary multi-part technique on the Hammond B-3 organ, playing bass with the foot pedals and Charlie Parker-like single-line passages with his right hand, shook up the traditional trio as co-players could explore new roles. Yet, while the consensus is Smith's playing is a jazz landmark, his recordings fall short of such acclaim.

Not a single album is listed among the 200 most important recordings in the book Essential Jazz Library by New York Times critic Ben Ratcliff. The Penguin Guide To Jazz On CD notes "it was disappointing... to hear how quickly Smith's albums become formulaic." Rolling Stone calls much of his late career work "substandard."

The joy in building a Smith collection is one can almost always count on his worthwhile albums being fun, fast, and spiritual blues romps with lots of his patented tonal color.

The drawback is... pretty much the same thing.

There's a sameness to much of his work, and many of his "outside the box" efforts into genres such as fusion and soundtracks are less than stellar. Adding to this discouragement is a number of his best early albums are out of print.

Still, it's hard to dispute the more than 100 albums in Smith's discography feature not only a rich collection of commercially popular music, but works of exceptional artistry.

Other players such as Count Basie experimented with the organ as far back as the 1930s, but Smith pioneered the fusion of R&B, gospel and jazz in addition to his unique playing style. He was an enormous success almost immediately and, following a commercial and critical lull during the 1970s and '80s, rebounded with several quality late-career recordings and saw his work influence artists from organist Joey DeFrancesco to hip-hop and jam bands incorporating digital samples of Smith's playing into their performances.

He died February 8, 2005, in his sleep at the age of 76 at his Scottsdale, Arizona, home.

"Jimmy was one of the greatest and most innovative musicians of our time," wrote DeFrancesco in a message at his Web site dated February 9, 2005, six days before the release of Legacy, his second album recorded with Smith. "I loved the man and I love the music. He was my idol, my mentor and my friend."

Smith was born in 1928 in Norristown, Pa., near Philadelphia, to a musically inclined family that saw him playing piano and bass as a youth. This combination proved an essential element of his one-man-band approach on the organ. He joined the Navy at age 15 to escape his hometown and after World War II studied at several Philadelphia music schools. He subsequently played piano for local R&B groups during the 1940s and 50s.

He explains his development on the organ in an oft-quoted interview:

"I got my organ from a loan shark and had it shipped to the warehouse," he said. "I stayed in that warehouse, I would say, six months to a year. I would do just like the guys do—take my lunch, then I'd go and set down at this beast. Nobody showed my anything, man, so I had to fiddle around with my stops."

His New York debut came in 1956 with Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers and the organist was an almost immediate hit.

Smith's early recordings were so successful Blue Note set up a special division to develop the genre he formed. He typically recorded numerous projects every year for the label between the late 1950s and his departure in 1962, including career highlights such as 1957s Groovin At Small's Paradise and 1960s Back At The Chicken Shack, perhaps his best-known album. Many are also noteworthy for all-star rosters of co-players such as guitarist Kenny Burrell, trumpeter Blue Mitchell, and saxophonists Stanley Turrentine and Jackie McLean.

His association with Verve Records beginning in 1962 saw both an expansion and limitation of his work. Among the most successful were a pair of albums recorded with guitarist Wes Montgomery and 1962's Bashin': The Unpredictable Jimmy Smith, with "Walk On The Wild Side" from the latter album making pop charts as a single.

However, new formats such as big bands often featured something other than the lengthy blowing sessions best suited to his strength of building up passages over time. Many also sought crossover audiences—toying, for instance, with show tunes and hard rock—and are frequently considered weak points of his discography.

Smith's struggles continued during the 1970s as synthesizers caused the B-3 to fall out of audience favor. He toured regularly until 1975, when he opened a Los Angeles jazz club with his wife, Lola. Recordings and appearances became infrequent and undistinguished until the early 1980s and, while many subsequent recordings are quality dates, the frequency of new albums continued to be sparse. Later-career highlights include two albums from a 1990 live reunion with Burrell and Turrentine (Fourmost and Fourmost Return), and the live 1999 Incredible! collaboration with DeFrancesco.

A revival of interest in the B-3 sound also resulted in Smith's music influencing and being performed by a wide range of players such as John Medeski and the Beastie Boys (noteworthy for their use of "Root Down"). The elder organist, who Miles Davis once proclaimed the "eighth wonder of the world," also reemerged as a popular performer, including weekly jam sessions with DeFrancesco during the years preceding his death.

"He had a spirit and a sound that comes across, and there was nothing like it," DeFrancesco said in a newspaper interview. "He was full of fire and soul, just the complete musician."

Albums

New listeners looking for a single get-acquainted album can't go wrong with the 1960 "classic? Back At The Chicken Shack , although some consider 1958's The Sermon and 1960's Crazy! Baby superior. Best of all may be 1957's live Groovin' At Small's Paradise if the budget allows for a double-disc.

Those looking for a good career retrospective might first consider the four-disc Retrospective featuring Blue Note highlights from the 1950s and '60s. A supplemental, or less expensive alternative, is the two-disc Walk On The Wild Side: The Best Of The Verve Years. An in-depth career-spanning boxed set remains elusive.

Groovin' At Small's Paradise (1957)

Perhaps the best of his initial albums currently in release, this live double-CD Blue Note collection with guitarist Eddie McFadden and drummer Donald Bailey plays heavily to Smith's strengths. There's a mix of standards, jazz and blues, mostly extended enough in length to allow the organist sufficient room for development. Some early pieces such as "My Funny Valentine" are more restrained than subsequent romps such as the widely acclaimed "After Hours."

The Sermon (1958)

Another strong early effort in a relatively straight-ahead vein, especially for those looking to hear Smith with a variety of players outside his familiar trio format. Among those on the all-star list are trumpeter Lee Morgan, guitarists Kenny Burrell and Eddie McFadden, alto saxophonists George Coleman and Lou Donaldson, and drummer Art Blakey. A reissued disc adds five tracks to the original three extended-length songs.

Crazy! Baby (1960)

There are two solid positives on this album: 1) he plays with his regular trio of guitarist Quentin Warren and drummer Donald Bailey instead of "name? players and 2) the opportunity, especially for newcomers to his music, to hear him play accessibly and yet with classic flair on familiar tunes such as "When Johnny Comes Marching Home" and "Makin' Whoopie." Not all agree: the Penguin guide calls it "discouragingly rational" and ranks it one of his two worst Blue Note recordings.

Back At The Chicken Shack (1960)

A stellar album, although its rank as the pinnacle of Smith's discography can be disputed. Smith is in high form on the roaring title track as well as standards such as "On The Sunny Side Of The Street," but his co-players score some of the most notable accomplishments. Tenor saxophonist Stanley Turrentine delivers what many consider the breakthrough performance of his career and guitarist Kenny Burrell provides a smooth counterpresence to the organist's madness. Both would still be playing with him decades later on some of his best late-career work.

Prayer Meetin' (1963)

This was Smith's final Blue Note recording until 1986. It was also the fourth album he recorded in a week as, eager to move to the Verve label, he put out a rush of albums to fulfill his existing contract. Even so, this is a quality work highlighted by Turrentine's tenor. Items of note include the rare inclusion of a bassist (Sam Jones) and two bonus tracks from the Chicken Shack era ("Lonesome Road" and "Smith Walk").

Jimmy And Wes: The Dynamic Duo (1966)

Interestingly, a number of critics refer to Smith's best musical partners providing a subtle ying to his intense yang. This big band-aided collaboration is among his most notable, as he and guitarist Wes Montgomery are as mismatched and yet strangely compatible as The Odd Couple, although a few apparent "crowd pleasers" are real clunkers ("Baby It's Cold Outside" is frequently cited). A second album from the session is The Further Adventures Of Jimmy And Wes.

Peter And The Wolf (1966)

Included with the disclaimer some critics rank this among the least of Smith's works ( All Music Guide's Scott Yanow is a notable exception) and it's probably accurate to say the playing is hardly his best. But since many of those same critics attack the sameness of his work and the concept of a jazz interpretation of these children's compositions is intriguing, this is as good a way as any to experience him "outside the box." Smith keeps the compositions recognizable, but with liberal doses of his own accent which are easy to distinguish given the simple and widely-known frame of reference.

Root Down (1972)

This Verve release is perhaps best-known for the Beastie Boys' cover of the title track in 1994, but also ranks as one of the strongest entries in Smith's work for the label. This live performance in Los Angeles is heavy on funk, supported by younger players such as Steve Williams on harmonica, Arthur Adams on guitar and Wilton Felder on bass. Smith's playing is generally raw and energetic—a refreshing change from arranged big band—especially on cuts such as "For Everyone Under The Sun."

Fourmost and Fourmost Return (1990)

Some of Smith's best late-career playing comes on this pair of discs recorded live with Turrentine, Burrell and drummer Grady Tate. The long-form arrangements ranging from standard ballads such as "My Funny Valentine" to the storming of a revived "Back At The Chicken Shack" suit the players well. Smith also contributes some scratchy vocals on "Ain't She Sweet" which, if accepted as the audience-pleaser they are, make for an entertaining extra.

Incredible! (1999)

This live performance is really more of a Joey DeFrancesco album, with Smith joining the younger organist for the final half of the hour-long set. But hearing the evolution of Smith's influence through DeFrancesco is reason enough to make this worthwhile, and it's intriguing to hear their two extended duets evolve into differing compositions (the titles, such as "Medley, No. 1: The Reverend/Yesterdays/ My Romance" are self-explanatory). The results may be audience-pleasing than artistic, but there's no denying both sound like they're having fun and generally complimenting each other well while doing so.

Boxed Sets/Compilations

Retrospective

This four-disc, 38-song collection representing Smith's Blue Note work from 1956 to 1963 is an excellent overview for listeners not attached to individual albums. Highlights include his 1956 performance of Dizzy Gillespie's "The Champ," the emerging freeform with Art Blakey on "The Duel," and a number of famous pieces such as "The Sermon? and "Incredible." Expanding the collection to include some of his "comeback" Blue Note work during the 1980s and '90s would be welcome, but they didn't reach the peaks Smith achieved during the earliest parts of his career.

Walk On The Wild Side: The Best Of The Verve Years (1962-73)

This 25-song, two-disc collection features many of his most popular songs, including the title track and some works with Wes Montgomery. It also features a range of small and large ensembles, making it more varied than the Blue Note collection. But the overall level of playing is less accomplished and it's a much less satisfactory listen for those seeking a truly representative overview of Smith's highlights and career. Still, it's a far superior choice to single-disc Verve compilations such as Ultimate Jimmy Smith and Jimmy Smith's Finest Hour, which contain too many overlapping tracks and lack significant depth.

DVD

Jazz Scene USA—Phineas Newborn Jr. and Jimmy Smith (1962)

There aren't a lot of Smith performances on DVD, but he puts on an impressive three-song trio performance with Quentin Warren and Donald Bailey during their half of this 60-minute Jazz Scene USA program. The casual, short-lived TV series does a fine job capturing Smith's technique on camera and the rendition of "Walk On The Wild Side" builds to a frenzy worthy of its title. Pianist Phineas Newborn Jr.'s performance on the other half of the disc came during a peak time in his career, a nice bonus.

https://www.udiscovermusic.com/stories/the-incredible-and-influential-jimmy-smith/

Features

The Incredible (And Influential) Jimmy Smith

People way too often overlook Jimmy Smith today, and that’s been true for a far too long. His Hammond organ playing influenced just about everyone that followed him in jazz and in rock, and it is all too easy to downplay his achievements in taking the electric organ out of the lounges and bars and putting it centre stage, He broke down the barriers between the genres to get people listening to his Hammond B3. Jon Lord of Deep Purple acknowledged the influence of Smith, as did Peter Bardens, Brian Auger, Rick Wakeman and Keith Emerson. Without Smith, Booker T would not have developed his sound; he influenced Gregg Allman, and Greg Rolie of Santana.

The shock that people felt on hearing Jimmy’s Hammond organ in full flight is impossible to measure today. We’ve become so used to every kind of synthesised sound that we take for granted that with today’s keyboards we can make anything, sound like anything. When Jimmy came along his playing was revolutionary, but somehow or another it’s got overtaken by new technology, but let’s not let anything take away from what he achieved.

‘It took me two and a half weeks to find my sound and when I did I pulled out all the stops, all the stops I could find.’ – Jimmy Smith

James Oscar Smith’s father had a song-and-dance act in the local clubs, so it was perhaps no surprise that as a young boy his son took to the stage at six years old. Less usual though was that by the age twelve, he had taught himself, with occasional guidance from Bud Powell who lived nearby, to be an accomplished “Harlem Stride” pianist. He won local talent contests with his boogie-woogie piano playing and his future seemed set, but his father became increasingly unable to perform and turned to manual labour for income.

Smith left school to help support the family and joined the Navy when he was fifteen years old. With financial assistance from the G.I. Bill of Rights, set up in 1944 to help Second World War veterans rehabilitate, Smith was able to return to school in 1948, this time studying bass at the Hamilton School of Music in Philadelphia. At this point he was juggling school with working with his father and playing piano with several different R&B groups. It was in 1953 while playing piano with Don Gardener’s Sonotones that Smith heard Wild Bill Davis playing a Hammond organ and was inspired to switch to the electric organ.

His timing was perfect. As a kickback against the cool school, jazz was returning to its roots, leaning heavily on the blues and gospel that infused Smith’s upbringing. At the time, Laurens Hammond was improving his Hammond organ model A first introduced in 1935 by refining the specifications and downsizing it from two keyboards and an excess of foot pedals and drawbars, to the sleeker, more sophisticated B3 design.

Smith got his first B3 in 1953 and soon devised ways to navigate the complex machine: ‘When I finally got enough money for a down payment on my own organ I put it in a warehouse and took a big sheet of paper and drew a floor plan of the pedals. Anytime I wanted to gauge the spaces and where to drop my foot down on which pedal, I’d look at the chart. Sometimes I would stay there four hours or maybe all day long if I’d luck up on something and get some new ideas using different stops.’

His timing was perfect. As a kickback against the cool school, jazz was returning to its roots, leaning heavily on the blues and gospel that infused Smith’s upbringing. At the time, Laurens Hammond was improving his Hammond organ model A first introduced in 1935 by refining the specifications and downsizing it from two keyboards and an excess of foot pedals and drawbars, to the sleeker, more sophisticated B3 design.

Smith got his first B3 in 1953 and soon devised ways to navigate the complex machine: ‘When I finally got enough money for a down payment on my own organ I put it in a warehouse and took a big sheet of paper and drew a floor plan of the pedals. Anytime I wanted to gauge the spaces and where to drop my foot down on which pedal, I’d look at the chart. Sometimes I would stay there four hours or maybe all day long if I’d luck up on something and get some new ideas using different stops.’

Developing his playing style independent from any outside influence, by cutting himself off from the outside world for three months, was perhaps the key to his singular success. His technique, steeped in the gospel tradition, with rapid runs across the keyboard using the palm of his hand and quirky use of the pedals to punch out entire bass lines, was like nothing ever heard before; there is not a single organist since that does not acknowledge a debt to the incredible Jimmy Smith.

Smith began playing Philadelphia clubs in that same year, taking in a young John Coltrane for a short two-week stint at Spider Kelly’s, “It was Jimmy Smith for about a couple of weeks before I went with Miles – the organist. Wow! I’d wake up in the middle of the night, man, hearing that organ. Yeah, those chords screaming at me.” Remembers Coltrane.

Shortly afterwards Smith left Philly behind, heading for his New York debut. From his first gig in Harlem, it was patently obvious that this was something quite new, and it was not long before his novelty was attracting considerable attention, not least from the Blue Note label owner Alfred Lion, who offered him a record deal. Smith had almost instantaneous success with the presciently titled A New Sound… A New Star… This launched Smith’s hugely successful career, and gave Blue Note a much-needed income from a steady stream of albums over the next seven years. Albums such as The Sermon (1958), Prayer Meetin’ (1960) and Back at the Chicken Shack (1960) all secured the label hit jukebox singles: a rarity for many jazz artists.

Smith’s Blue Note sessions partnered him with Kenny Burrell, Art Blakey, Lee Morgan, Lou Donaldson, Stanley Turrentine, Jackie McLean and many others, before he move to Verve in 1962 where he immediately released a critical and commercial success in the form of Bashin’: The Unpredictable Jimmy Smith, which included the hit track ‘Walk On The Wild Side’. A song written by Elmer Bernstein, it was the title track to a movie. The album benefited greatly from the arranging skills of Oliver Nelson and ‘Walk On The Wild Side’ made No. 21 on the Billboard pop chart and was the biggest hit of his career.

Bashin’… made the Billboard album chart in June 1962 climbing to No. 10, and for the next four years his albums rarely failed to chart. Among his biggest successes were Hobo Flats (1964), Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf (1964), The Cat (1964), Organ Grinder Swing (1965) and Jimmy & Wes – The Dynamic Duo (1967).

Following the last of a series of European tours in 1966, 1972 and 1975, rather than continuing to travel to play, Smith chose to settle down with his wife in the mid-1970s and run a supper club in California’s San Fernando Valley. Despite his regular performances, the club failed after only a few years, forcing a return to recording and frequent festival appearances, albeit not to the kind of acclaim that he had received previously. In fact, it wasn’t until the late 1980s that Smith produced several well-reviewed albums. He also received recognition for a series of live performances with fellow organ virtuoso Joey DeFrancesco, and his reinvigorated profile even led producer Quincy Jones to invite him to play on the sessions for Michael Jackson’s album, Bad in 1987; Smith plays the funky B3 solo on the title track and it went on for more than 20 minutes in the studio; it was edited on the final track to just over a minute. At the other end of the pop spectrum, he played on Frank Sinatra’s L.A. Is My Lady album in 1984 produced by Quincy Jones.

As his reputation grew again, Smith toured afar, playing with small groups in Japan, Europe and the United States, helped by hip-hop DJs spreading his name by sampling Smith’s funky organ grooves, exposing him to a new generation of fans through the Beastie Boys, Nas, Gang Starr, Kool G Rap and DJ Shadow. Returning to Verve in 1995, Smith recorded the album Damn! and Dot Com Blues in 2001, featuring legendary R&B stars, including Etta James, B. B. King, Keb’ Mo’, and Dr. John.

After moving to Scottsdale, Arizona, Smith died in 2005, less than a year after his wife. His final recording, “Legacy” with Joey DeFrancesco, was released posthumously. DeFrancesco dedicated the album, ‘To the master, Jimmy Smith—One of the greatest and most innovative musicians of all time.’ It’s time for a reappraisal of The Incredible Jimmy Smith who did as much to popularize jazz as almost any of his contemporaries.

https://www.jazzwax.com/2018/07/jimmy-smith-portuguese-soul.html

July 30, 2018

Jimmy Smith: Portuguese Soul

One of organist Jimmy Smith's most interesting experimental albums is Portuguese Soul. Recorded for Verve in February 1973, the album remains little known by many, largely because it was out of print for years. The album wasn't well-served by the cover's design, which looks like a horror film poster. Those who are new to the album may be surprised to learn that it was arranged by Thad Jones, who conducted a large orchestra whose members sadly were never listed on the back of the jacket and remain anonymous. [Photo above of Jimmy Smith by Francis Wolff © Mosaic Images]

As Smith writes in the album's liner notes, "It all started at 4 a.m., Sunday, November 13, 1972, after our segment of the Newport Jazz Festival had just wrapped up [along with] our last concert of the three-month European tour, in Cascals, a little town on the outskirts of Lisbon, Portugal. We were packed, and the other guys had crashed, but this guy was pacing with all sorts of music twisting my head, going in so many directions. I knew it couldn't be just another tune or two tunes, but a whole damn suite.

"I was rapping on tables, glasses, suitcases—anything that would get near the sounds I heard. I stayed on this 'musical high' for days and when I felt I had it all together, there was no doubt who the one man was who could musically dissect my brain, hear what was there and get on the same trip, and that was Thad Jones."

The music on the album is fascinating. The recording opens with Don McLean's And I Love You So, which Smith first heard in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. He missed the first verse and song's title before he was able to turn on his tape recorder, but he says in the notes he managed to capture enough of it to know he had to record it. Next up is Blap, a 10:53 original that must have come from the banging on tables and glasses. It completes Side 1.

On Side 2, there's a four-minute opening instrumental prologue. Next come three movements that finish the album. The first and third movements are by Smith while the second is by Jones. What's fascinating about this album is that the music is heavily perfumed by Jones's expansive orchestral arranging style punctuated by Smith's organ ruminations throughout. It's also deeply complex and moody music.

What's unfortunate is that the musicians on the date aren't listed. Saxophonist Bill Kirchner, who knew Thad Jones and sat in with Mel Lewis Band and the Jazz Orchestra in the 1980s, told me the following:

"The band is the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Big Band, but with Grady Tate on drums and Mel on percussion. On one movement, there are two tenor solos, by Billy Harper and Ron Bridgewater, the band’s two tenor players at the time. My educated guess is that Jimmy probably insisted on Grady (who did most if not all of Smith’s big band albums) playing drums, so out of respect for Mel, they didn’t identify the band as the Jones-Lewis band. But it’s only a guess."

If I have time, I'll see if New York's Local 802 has the session sheets.

Jimmy Smith died in 2005:

JazzWax tracks: Fortunately, Jimmy Smith's Portuguese Soul is available as a download for only $6.99 here.

The album also is available at Spotify.

JazzWax clip: Here's And I Love Her So...

https://www.nytimes.com/2005/02/10/arts/music/jimmy-smith-jazz-organist-and-pioneer-is-dead-at-76.html

Jimmy

Smith, who made the Hammond organ one of the most popular sounds in

jazz beginning in the mid-1950's, died on Tuesday at his home in

Phoenix. He was 76.

He

died of unspecified natural causes, said his stepson and former

manager, Michael Ward, who also said that his age of 76 was based on his

birth certificate and not the birth date found in most reference books.

Before

Jimmy Smith, the electric organ had been nearly a novelty in jazz; it

was he who made it an important instrument in the genre and influenced

nearly every subsequent notable organist in jazz and rock, including

Jimmy McGriff, Jack McDuff, Larry Young, Shirley Scott, Al Kooper and

Joey DeFrancesco.

By

1955 -- which coincidentally was the year Hammond introduced its most

popular model, the B-3 -- he had an organ trio with a new sound that

would thereafter become the model for groups in what became known as

"organ rooms," the urban bars up and down the East Coast specializing in

precisely the kind of blues-oriented, swinging, funky music that Mr.

Smith epitomized. He continued touring and recording until just before

his death.

Born

in 1928, Mr. Smith grew up in a musical family in Norristown, Pa., near

Philadelphia; by his early teens he was competently playing stride

piano and performing as a dancer in a team with his father, a

day-laboring plasterer who also played piano at night.

He

left school in the eighth grade, never to return, and joined the Navy

at the age of 15. When he finished his service in 1947, he played

professionally and studied music for two years on the G.I. bill at the

Ornstein School of Music.

In

the early 1950's he worked around Philadelphia, playing rhythm and

blues with Don Gardner's Sonotones. In 1952, or perhaps 1953, he met

Wild Bill Davis, the organ player who pioneered the organ-trio format,

at a club. Mr. Smith asked him how long it would take to learn the

organ; Davis replied that it would take years to learn the pedals alone.

(In Mr. Smith's retelling, the number of years varied between 4 and

15.) Playing piano at night and practicing organ during the day, Mr.

Smith studied a chart of the instrument's 25 foot pedals and claimed

that he played fluent walking-bass lines with his feet within three

months.

By 1955 he was on his way to making his new organ trio sound pervasive.

Like

many other great jazz musicians, Mr. Smith insisted that the key to

finding his own sound was through studying musicians who did not play

his instrument.

"While

others think of the organ as a full orchestra," he wrote in a short

piece for The Hammond Times in 1964, "I think of it as a horn. I've

always been an admirer of Charlie Parker, and I try to sound like him. I

wanted that single-line sound like a trumpet, a tenor or an alto

saxophone."

He

also made heavy use of the B-3's "percussion" sound, a circuit

controlled by one of its drawbar switches that gives it a leaner tone,

closer to that of a piano.

Partly

through the agency of Babs Gonzalez, the singer and radio disc jockey,

Mr. Smith was signed to the Blue Note label, making his first albums for

the label in 1956; some well-received gigs that year at the Cafe

Bohemia in New York heightened the excitement about his new sound.

He

made many popular records for Blue Note and Verve, among them "Groovin'

at Small's Paradise," "The Cat" (with the arranger Lalo Schifrin), a

few records with the guitarist Wes Montgomery and in 1965 his vocal

version of "Got My Mojo Workin'," arranged by Oliver Nelson.

In

the mid-1970's Mr. Smith moved to Los Angeles, where he opened a club,

Jimmy Smith's Jazz Supper Club; he played there when he could and

otherwise toured in order to keep the club afloat.

He

married and had a family; his survivors include a son, Jimmy Jr., and a

daughter, Jia, both of Philadelphia, as well as two sisters, Anita

Johnson and Janet Smith, also of Philadelphia.

Mr.

Smith had lived in Phoenix since January 2004. Last summer he recorded

"Legacy," to be released next week on Concord, which paired him in duets

with Mr. DeFrancesco.

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2005/feb/11/guardianobituaries.artsobituaries

Jimmy Smith

Jazz organist who brought sophistication to the Hammond sound

Jimmy Smith, the Philadelphia-born Hammond organ pioneer, who has died

aged 76, generally approached his performances like a man who was

certain he was in showbusiness, rather than art. Smith's gigs regularly

involved plenty of stagey gesticulation, badinage with audiences, and

mopping his brow with towels. The music was mostly rooted in that most

accessible 20th-century formula, the twelve-bar blues.

But the art was never far below the surface. Smith refined and

modernised a musical instrument better designed for travelling

preachers, magic shows or the end of the pier. He brought a

sophisticated and high-powered pianist's technique to it, and in

coupling the Hammond's holy-rolling aptitudes to bebop, helped open up

modern jazz to audiences otherwise impatient with its intricacies.

With full-on performances such as 1962's Walk On The Wild Side (pitting his careering keyboard playing against a smoky Oliver Nelson big-band score) and The Sermon, Smith became one of the biggest stars on Norman Granz's Verve label in the early 60s, a hero of the earthy jazz school known as hard bop, and a model for all aspiring Hammond players.

He was born James Oscar Smith in Norristown, Pennsylvania. His parents taught him piano, and he won a radio talent contest in Philadelphia, playing boogie-woogie, when he was nine.