SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2019

VOLUME SEVEN NUMBER TWO

HOLLAND DOZIER HOLLAND

(L-R: LAMONT DOZIER EDDIE HOLLAND BRIAN HOLLAND)

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

SHIRLEY SCOTT

(June 15-21)

FREDDIE HUBBARD

(June 22-28)

BILL WITHERS

(June 29- July 5)

OUTKAST

(July 6-12)

J. J. JOHNSON

(July 13-19)

JIMMY SMITH

(July 20-26)

JACKIE WILSON

(July 27-August 2)

LITTLE RICHARD

(August 3-9)

KENNY BARRON

(August 10-16)

BLIND LEMON JEFFERSON

(August 17-23)

MOS DEF

(August 24-30)

BLIND BOY FULLER

(August 31-September 6)

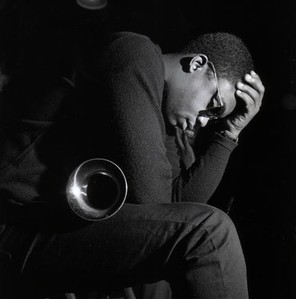

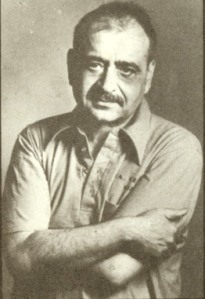

Freddie Hubbard

(1938-2008)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

One of the great jazz trumpeters of all time, Freddie Hubbard formed his sound out of the Clifford Brown/Lee Morgan

tradition, and by the early '70s was immediately distinctive and the

pacesetter in jazz. However, a string of blatantly commercial albums

later in the decade damaged his reputation and, just when Hubbard, in the early '90s (with the deaths of Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis), seemed perfectly suited for the role of veteran master, his chops started causing him serious troubles.

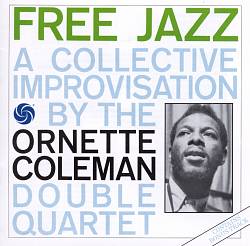

Born and raised in Indianapolis, Hubbard played early on with Wes and Monk Montgomery. He moved to New York in 1958, roomed with Eric Dolphy (with whom he recorded in 1960), and was in the groups of Philly Joe Jones (1958-1959), Sonny Rollins, Slide Hampton, and J.J. Johnson, before touring Europe with Quincy Jones (1960-1961). He recorded with John Coltrane, participated in Ornette Coleman's Free Jazz (1960), was on Oliver Nelson's classic Blues and the Abstract Truth album (highlighted by "Stolen Moments"), and started recording as a leader for Blue Note that same year. Hubbard gained fame playing with Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers (1961-1964) next to Wayne Shorter and Curtis Fuller. He recorded Ascension with Coltrane (1965), Out to Lunch (1964) with Eric Dolphy, and Maiden Voyage with Herbie Hancock, and, after a period with Max Roach (1965-1966), he led his own quintet, which at the time usually featured altoist James Spaulding. A blazing trumpeter with a beautiful tone on flügelhorn, Hubbard fared well in freer settings but was always essentially a hard bop stylist.

In 1970, Freddie Hubbard recorded two of his finest albums (Red Clay and Straight Life) for CTI. The follow-up, First Light (1971), was actually his most popular date, featuring Don Sebesky arrangements. But after the glory of the CTI years (during which producer Creed Taylor did an expert job of balancing the artistic with the accessible), Hubbard made the mistake of signing with Columbia and recording one dud after another; Windjammer (1976) and Splash (a slightly later effort for Fantasy) are low points. However, in 1977, he toured with Herbie Hancock's acoustic V.S.O.P. Quintet

and, in the 1980s, on recordings for Pablo, Blue Note, and Atlantic, he

showed that he could reach his former heights (even if much of the jazz

world had given up on him). But by the late '80s, Hubbard's

"personal problems" and increasing unreliability (not showing up for

gigs) started to really hurt him, and a few years later his once mighty

technique started to seriously falter. In late 2008, Hubbard suffered a heart attack that left him hospitalized until his death at age 70 on December 29 of that year.Freddie Hubbard's

fans can still certainly enjoy his many recordings for Blue Note,

Impulse, Atlantic, CTI, Pablo, and his first Music Masters sets.

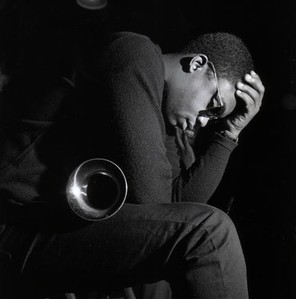

Freddie Hubbard

Freddie Hubbard

Frederick Dewayne Hubbard (born April 7, 1938 in Indianapolis, Indiana) is an American jazz trumpeter.

Frederick Dewayne Hubbard (born April 7, 1938 in Indianapolis, Indiana) is an American jazz trumpeter.In his youth, Hubbard associated with various musicians in Indianapolis, including Wes Montgomery and Montgomery's brothers. Chet Baker was an early influence, although Hubbard soon aligned himself with the approach of Clifford Brown (and his forebears: Fats Navarro and Dizzy Gillespie).

Hubbard's jazz career began in earnest after moving to New York City in 1958. While there, he worked with Sonny Rollins, Slide Hampton, J. J. Johnson, Philly Joe Jones, Oliver Nelson, and Quincy Jones, among others. He gained attention while playing with the seminal hard bop ensemble Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, appearing on such albums as Mosaic, Buhaina's Delight, and Free For All. He left the Messengers in 1964 to lead his own groups and since that time has maintained a high profile as a bandleader or featured as a special guest, but never merely a sideman.

Along with two other trumpeters also born in 1938, Lee Morgan (d. 1971) and Booker Little (d. 1961), Hubbard exerted a strong force on the direction of 1960s jazz. He recorded extensively for Blue Note Records: eight albums as a bandleader, and twenty-eight as a sideman. [1] Most of these recordings are regarded as classics. Hubbard appeared on a few early avant-garde landmarks (Ornette Coleman's Free Jazz, Eric Dolphy's Out to Lunch and John Coltrane's Ascension), but Hubbard never fully embraced free jazz, though it has influenced his playing.

After leaving Blue Note, Hubbard recorded for the Atlantic label and moved toward a more commercial style. His next label was CTI Records where he recorded his best-known works, Red Clay, First Light, and Sky Dive. By 1970, his fiery, melodic improvisation and phenomenal technique established him as perhaps the leading trumpeter of his day, but a series of commercially oriented smooth jazz albums spawned some negative criticism. After signing with Columbia Records, Hubbard's albums were almost exclusively in a commercial vein. However, in 1976, Hubbard toured and recorded with V.S.O.P., led by Herbie Hancock which presented unadulterated jazz in the style of the 1960s Miles Davis Quintet (with Hubbard taking the place of Davis).

1980s projects moved between straight-ahead and commercial styles, and Hubbard recorded for several different labels including Atlantic, Pablo, Fantasy, Elektra/Musician, and the revived Blue Note label. The slightly younger Woody Shaw was Hubbard's main jazz competitor during the 1970s and 1980s, and the two eventually recorded together on three occasions. Hubbard participated in the short-lived Griffith Park Collective, which also included Joe Henderson, Chick Corea, Stanley Clarke, and Lenny White.

Following a long setback of health problems and a serious lip injury in 1992, Hubbard is again playing and recording occasionally, but not at the high level that he set for himself during his earlier career.

https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1127264

Freddie Hubbard: A Jazz Icon Remembered

AUDIO: <iframe src="https://www.npr.org/player/embed/1127264/98787455" width="100%" height="290" frameborder="0" scrolling="no" title="NPR embedded audio player"></iframe>

After personal setbacks left him unable to play, Freddie Hubbard is now making a comeback with a new album. Tom Copi/ Michael Ochs Archives/ Getty Images

Freddie Hubbard is a legendary name in jazz. In the 1960s, he was a popular and critically acclaimed trumpeter and bandleader. But by the 1980s, he had all but disappeared from the jazz scene. Now, he's attempting a comeback.

Hubbard says that the low point in his career came in the early 1990s. After he split his lip and lost the ability to play, he started drinking, suffered an ulcer and almost died.

"I started drinking Jack Daniel's to feel good, you know? Jack Daniel's and Coca-Cola," Hubbard says. "And I had an ulcer. I went over in London and I fell out. I've never passed out, but I lost four pints of blood. And the doctor said, 'You're going to clean up your body, because otherwise you're looking to go.' So I said, 'Well, I'm not ready to go, so let me cool out.'"

Hubbard's decline is more startling when you consider the heights from which he fell. In the early 1970s, Hubbard supplanted Miles Davis as the top jazz trumpeter in polls of fans and critics. Then he won a Grammy for his album First Light.

Critic Stanley Crouch calls Hubbard one of the most important and original jazz trumpeters of the last 40 years.

"From the moment he played one note," Crouch says, "you knew that was Freddie Hubbard. So he had a sound that was distinctive as Miles Davis, as Louis Armstrong, as Clifford Brown. I mean, he's one of those trumpet players.

"He's also an extraordinary powerful player — great stamina, great range," Crouch says. "He swung very hard, was a beautiful ballad player and seemed to have very few limitations in terms of getting through material, whether the material was very simple material or very complex material. He was quite a musician."

Trumpeter Wynton Marsalis says that Hubbard was one of his main influences.

"All the trumpet players in the '70s, you can hear Freddie Hubbard's sound and everything worth playing," Marsalis says. "He's such a phenomenal trumpet player — just the largeness of his sound, the velocity and the swing."

Hubbard was a little-known bebop player imitating Miles Davis solos when he dropped out of college in Indianapolis and moved to New York. In the late 1950s, the 20-year-old trumpeter shared an apartment with saxophonist and flutist Eric Dolphy, and he quickly established himself at jam sessions across the city. Hubbard says he was playing with John Coltrane at Birdland one night when Davis dropped by.

"Miles was sitting in the front of the stage," Hubbard says, "so I was copying his solo off of one of his records. And so when I saw him, I said, 'Oh my God. I've got to make up something else very quick.' So I came up with something pretty good. So when I got off the stage, he said, 'Come here, man. I want to talk to you.' So I talked to him, and then he introduced me to Alfred Lion. And he told Alfred, 'Sign him up.'"

And that's just what Alfred Lion did, signing Hubbard to a four-record deal with his legendary Blue Note label. Hubbard's reputation burned even brighter as the horn player of choice among leaders of more adventurous jazz.

In addition to turning up on Eric Dolphy's Out to Lunch, Hubbard appeared as a side man on John Coltrane's Ascension, East Broadway Rundown by Sonny Rollins, Herbie Hancock's Maiden Voyage and Oliver Nelson's Blues and the Abstract Truth.

"I don't know how I met all these people," Hubbard says, "but a lot of them came to get me, too. They sought me out because they saw I wanted to experiment, and during that period, I was changing the style of the trumpet. I was trying to play the trumpet like a saxophone. Instead of saying, 'Dah, dah, du, du, di, di, di, do,' I was saying, 'Diddly, do, du, do, dah, do, wham, bam, be,' playing more intervals. And I was trying to make those as long glissando runs, like 'trun, da, dun, dun, da, lun, da, da, da, da, da,' and trumpet players don't do that."

Hubbard says that, in all, he played on more than 300 records. Then, in the 1970s, he moved to Hollywood.

"You know, lifestyle out there is different from mine than in New York," Hubbard says. "I mean, I was in the Hollywood Hills, above the Bowl. I could look at the ocean on this side. I can hear the concerts free at the Bowl. And I had a big swimming pool. I had parties all the time, and the trumpet just was in the corner a lot of the time, when it should have been on my lips."

When he did pick up his trumpet, Hubbard played pop and R&B.

Ten years ago, Hubbard split his lip in Philadelphia by playing without warming up. He continued to perform until the lip got infected and he had to stop. In the 1990s, he says he managed to make a living on royalties when rap musicians sampled his music. Sometimes, he was even asked to play a few notes.

"I guess they'd call me up," Hubbard says, "and like I said, do 16 bars and the money was good, so I didn't feel the need to go out on the road and hustle and bustle."

After some soul searching, Hubbard says he decided to try to play real jazz again. This spring, he released his first record in six years. But the 63-year-old trumpeter says that he'll never have the chops he once had.

"It's mind-boggling to me," Hubbard says, "but I come to the conclusion that I'm not going to play that way again. And as far as giving up all the 30 choruses I used to play — and I used to play with such intensity, trying to play like Coltrane and play, you know, hard and long. I think now I have to dig down and play from my soul."

Hubbard says that he plans to continue working with his current band, The New Jazz Composers Octet, and he wants to visit schools, in part to encourage a new generation of composers.

"We've got to wind this music back to the real deal," Hubbard says. "If you've noticed, nobody's written any good songs lately. What song can you name me that's famous that they've written in the last 10 years? Like a 'Sidewinder.' You remember that? You remember 'Red Clay'? You remember Herbie [Hancock]'s 'Maiden Voyage'? You remember Miles' 'All Blues'? You see what I'm saying? But when we came along behind Coltrane and Miles, then you had to come up with some songs."

Freddie Hubbard revisits some of his best-known songs with new arrangements on his latest CD, New Colors.

https://www.arts.gov/honors/jazz/freddie-hubbard

NEA Jazz Masters

"I feel very blessed and honored to have received this award. I feel as though I owe all the great jazz trumpeters before me gratitude. I sincerely hope that I have contributed something to [the] art of playing the trumpet, writing, and composing."

One of the greatest trumpet virtuosos ever to play in the jazz idiom, and arguably one of the most influential, Freddie Hubbard played mellophone and then trumpet in his school band and studied at the Jordan Conservatory with the principal trumpeter of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra. As a teenager, he worked with Wes and Monk Montgomery and eventually founded his own band, the Jazz Contemporaries, with bassist Larry Ridley and saxophonist James Spaulding. After moving to New York in 1958, he quickly astonished fans and critics alike with his depth and maturity, playing with veteran artists Philly Joe Jones, Sonny Rollins, Slide Hampton, J.J. Johnson, Eric Dolphy, and Quincy Jones, with whom he toured Europe.

In June 1960, on the recommendation of Miles Davis, he recorded his first solo album, Open Sesame, for Blue Note Records, just weeks after his 22nd birthday. Within the next 10 months, he recorded two more albums, Goin' Up and Hub Cap, and then in August 1961 made what many consider to be his masterpiece, Ready for Freddie, which was also his first Blue Note collaboration with Wayne Shorter. That same year, Hubbard joined Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, replacing Lee Morgan. By now, he had indisputably developed his own sound and had won the DownBeat "New Star" award on trumpet.

Hubbard remained with the Jazz Messengers until 1964, when he left to form his own small group, which over the next years featured Kenny Barron and Louis Hayes. Throughout the 1960s, Hubbard also played in bands led by other legends, including Max Roach, and was a significant presence on the Blue Note recordings of Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter and Hank Mobley. Hubbard was also featured on four classic, groundbreaking 1960s sessions: Ornette Coleman's Free Jazz, Oliver Nelson's Blues and the Abstract Truth, Eric Dolphy's Out to Lunch, and John Coltrane's Ascension.

In the 1970s, Hubbard achieved his greatest popular success with a series of crossover albums on Atlantic and CTI Records, including the Grammy Award-winning First Light. He returned to acoustic hard bop in 1977 when he toured with the V.S.O.P. quintet, which teamed him with the members of Miles Davis' 1960s ensemble: Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams. In the 1980s, Hubbard again led his own groups, often in the company of Joe Henderson, and he collaborated with fellow trumpet legend Woody Shaw on a series of albums for the Blue Note and Timeless labels.

Selected Discography

Ready for Freddie, Blue Note, 1961

Hub-Tones, Blue Note, 1962

Straight Life, Columbia, 1970

Live, CLP, 1983

New Colors, Hip Bop Essence, 20

https://jazztimes.com/features/profiles/freddie-hubbard-red-clay/

Freddie Hubbard: Red Clay

The legacy of the trumpeter’s 1970 album for CTI

It was a transitional period in jazz; the tectonic shift beginning with Miles Davis’ In a Silent Way, recorded the previous year. Hubbard’s entry into this crossover territory on Red Clay was characterized by the slyly syncopated beats of drummer Lenny White on the funky 12-minute title track, an infectious groover that was soon covered by budding crossover groups all over America. Essentially an inventive line set to the chord changes of “Sunny,” Bobby Hebb’s hit song from 1966, “Red Clay” would become Hubbard’s signature tune throughout his career. As trumpeter, friend and benefactor David Weiss, who is credited with bringing Hubbard out of self-imposed retirement in the late ’90s, explains, “Later in life Freddie would always announce it as ‘the tune that’s been keeping me alive for the last 30 years.’ We played ‘Red Clay’ every night and he would quote ‘Sunny’ over it every night.”

That looseness can be attributed in large part to drummer White, whose wide beat and interactive instincts characterize the track. “Freddie always credited Lenny with that,” says Weiss. “He said Lenny came up with the beat and that he himself had nothing to do with it. He was always happy to give Lenny credit on that track.”

White, who had just turned 20 a month before the Red Clay sessions, was in the midst of an extremely productive period as a young drummer coming up on the scene. Two months earlier (Nov. 7-14, 1969) he had played on Andrew Hill’s Passing Ships for Blue Note. Before that (Aug. 19-21, 1969) he had participated in Miles Davis’ landmark Bitches Brew sessions. Later in 1970, he would play on two other cutting-edge albums: Joe Henderson’s If You’re Not Part of the Solution, You’re Part of the Problem for Milestone (Sept. 24-26) and Woody Shaw’s Blackstone Legacy for Contemporary (Dec. 8-9). “I had gotten a call from Freddie asking me if I wanted to do a record date,” recalls White. “Freddie Hubbard’s a hero to me, so naturally I said, ‘Sure, I’d love to.’ But then I asked him a stupid question. I said, ‘Who’s on it?’ And he said, ‘Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and Joe Henderson.’ When he said that, inside I was screaming but outside I tried to stay cool: ‘Oh, right. No problem.'”

Hubbard directed White to show up at Van Gelder’s studio on the morning of Jan. 27. But as he was setting up his drums and trying them out, he encountered a problem. “I had this bass drum which was made from a big oil can. This guy who made it for me had fashioned it into an actual drum. He shaved off the edges and made hoops and everything. It’s the same drum I used on Bitches Brew. But as soon as I hit it, Ron Carter said, ‘No, man. That’s not gonna work. That drum is too resonant.’ So we went in the back where Rudy had a whole bunch of equipment stored. And Rudy pulled out this 26- or 28-inch bass drum that had a painting of a moonlit lake on it. I thought it sounded horrible. But that’s the bass drum that I played on the session, and for 10 years after that record came out I didn’t listen to it because I hated the way I sounded on it. It was a traumatic thing for me, because here I got an opportunity to play with all my heroes and I had to play this horrible drum. I thought I didn’t sound good so I didn’t listen to it for so long.”

Carter’s memory of this scenario is detailed in his ArtistShare biography, Finding the Right Notes, by noted jazz writer Dan Ouellette:

“I told Lenny, ‘Listen, Rudy is ready to walk up the stairs and leave and then we’d be done,'” said Ron. “We’d been there for two hours, and it was obvious the steel drums weren’t working. The song wasn’t going anywhere. Freddie was getting more and more anxious, Joe Henderson was just waiting for something to happen. The energy was dissipating, attitudes were starting to show up and the vibe was turning strange.”

Outside Ron tried to talk sense to Lenny, who still wanted to use the pans. “I can appreciate you want to get your sound,” said Ron. “But playing in the studio isn’t like playing in a club. Certain things don’t apply. In this case, your drums don’t apply. My recommendation to get some real music going here is to stash that drum in your trunk. We can’t keep doing this. I won’t keep doing this. We don’t want to be doing take 503 with that drum.”

Forty years later, trumpeter Randy Brecker is amused to learn about the whole drum controversy surrounding Red Clay. “My first thought after hearing that album back then was, ‘It sure doesn’t sound like the drums that Lenny would normally play … especially the bass drum. Something was really weird with that. The bass drum sounded real dull and kind of separated from the rest of the kit, like it was out in the middle of nowhere somehow.”

Brecker’s second impression of Red Clay concerned the presence of the young drummer amidst all those celebrated jazz veterans. “Lenny was in our small inner circle of younger guys who were jamming all the time at Dave Liebman’s place or at Mike Garson’s place. Lenny is a few years younger than me. The first time I played with him he was 17. And, to me, to see him playing on a record with Ron, Herbie, Joe and Freddie was like, ‘Wow!’ Because these were the higher-echelon cats. It was a big break for Lenny to actually be playing with them, so I was really happy about the fact that he was on that record. I didn’t know he had done this session until I had bought Red Clay, so it was a thrill to see that he had made it, so to speak.”

In the studio, Hubbard had no specific direction for the young drummer on the Red Clay session. As White recalls, “He just said, ‘Man, I need a beat. Gimme a beat.’ And that was it. So I came up with a beat and I put a triplet feel in there, and nobody has ever picked up on that. Everybody who played that tune after me didn’t actually get that beat right because they didn’t put that triplet feel in.”

White’s loosely syncopated, interactive approach to the kit-a kind of marriage between Clyde Stubblefield’s locked-down, funky-drummer signature with James Brown and Roy Haynes’ unpredictable yet bop-rooted approach-ultimately went against the grain of Creed Taylor’s slicker tendencies that came to define the CTI sound throughout the ’70s. As White recalls, “I did another CTI date with Freddie after that [1974’s Polar AC, Hubbard’s last recording for the label]. But Creed didn’t call me for a lot of record dates, because I think he really wanted a more structured and tight beat.”

White also reveals that he was not the first choice for the Red Clay sessions. “The inside story on this-and this is what I had gotten from Wallace Roney, who had talked with Tony Williams about it-[was that] apparently Freddie had originally called Tony to do the record, but Miles was kind of upset with that rhythm section playing on other people’s albums and making everybody else sound good. So Tony decided that he wasn’t going to do it, and he recommended me for the session. And it turned out to be a really nice opportunity for me, even though I did hate my bass drum sound on that record.”

The rest of this article appears in the September 2010 issue of JazzTimes.

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/30/arts/music/30hubbard.html

Music

Freddie Hubbard, Jazz Trumpeter, Dies at 70

Freddie

Hubbard, a jazz trumpeter who dazzled audiences and critics alike with

his virtuosity, his melodicism and his infectious energy, died on Monday

in Sherman Oaks, Calif. He was 70 and lived in Sherman Oaks.

The cause was complications of a heart attack he had on November 26, said his spokesman, Don Lucoff of DL Media.

Over

a career that began in the late 1950s, Mr. Hubbard earned both critical

praise and commercial success — although rarely for the same projects.

He

attracted attention in the 1960s for his bravura work as a member of

the Jazz Messengers, the valuable training ground for young musicians

led by the veteran drummer Art Blakey, and on albums by Herbie Hancock,

Wayne Shorter and many others. He also recorded several well-regarded

albums as a leader. And although he was not an avant-gardist by

temperament, he participated in three of the seminal recordings of the

1960s jazz avant-garde: Ornette Coleman’s “Free Jazz” (1960), Eric

Dolphy’s “Out to Lunch” (1964) and John Coltrane’s “Ascension” (1965).

In

the 1970s Mr. Hubbard, like many other jazz musicians of his

generation, began courting a larger audience, with albums that featured

electric instruments, rock and funk rhythms, string arrangements and

repertory sprinkled with pop and R&B songs like Paul McCartney’s

“Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey” and the Stylistics’ “Betcha by Golly,

Wow.” His audience did indeed grow, but his standing in the jazz world

diminished.

By

the start of the next decade he had largely abandoned his more

commercial approach and returned to his jazz roots. But his career came

to a virtual halt in 1992 when he damaged his lip, and although he

resumed performing and recording after an extended hiatus, he was never

again as powerful a player as he had been in his prime.

Frederick

Dewayne Hubbard was born on April 7, 1938, in Indianapolis. His first

instrument was the alto-brass mellophone, and in high school he studied

French horn and tuba as well as trumpet. After taking lessons with Max

Woodbury, the first trumpeter of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, at

the Arthur Jordan Conservatory of Music, he performed locally with,

among others, the guitarist Wes Montgomery and his brothers.

Mr.

Hubbard moved to New York in 1958 and almost immediately began working

with groups led by the saxophonist Sonny Rollins, the drummer Philly Joe

Jones and others. His profile rose in 1960 when he joined the roster of

Blue Note, a leading jazz label; it rose further the next year when

he was hired by Blakey, widely regarded as the music’s premier talent

scout.

Adding

his own spin to a style informed by Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis and

Clifford Brown, Mr. Hubbard played trumpet with an unusual mix of

melodic inventiveness and technical razzle-dazzle. The critics took

notice. Leonard Feather called him “one of the most skilled, original

and forceful trumpeters of the ’60s.”

After

leaving Blakey’s band in 1964, Mr. Hubbard worked for a while with

another drummer-bandleader, Max Roach, before forming his own group in

1966. Four years later he began recording for CTI, a record company that

would soon become known for its aggressive efforts to market jazz

musicians beyond the confines of the jazz audience.

His

first albums for the label, notably “Red Clay,” contained some of the

best playing of his career and, except for slicker production and the

presence of some electric instruments, were not significantly different

from his work for Blue Note. But his later albums on CTI, and the ones

he made after leaving the label for Columbia in 1974, put less and less

emphasis on improvisation and relied more and more on glossy

arrangements and pop appeal. They sold well, for the most part, but were

attacked, or in some cases simply ignored, by jazz critics. Within a

few years Mr. Hubbard was expressing regrets about his career path.

Most

of his recordings as a leader from the early 1980s on, for Pablo,

Musicmasters and other labels, were small-group sessions emphasizing his

gifts as an improviser that helped restore his critical reputation. But

in 1992 he suffered a setback from which he never fully recovered.

By

Mr. Hubbard’s own account, he seriously injured his upper lip that year

by playing too hard, without warming up, once too often. The lip became

infected, and for the rest of his life it was a struggle for him to

play with his trademark strength and fire. As Howard Mandel explained

in a 2008 Down Beat article, “His ability to project and hold a clear

tone was damaged, so his fast finger flurries often result in blurts and

blurs rather than explosive phrases.”

Mr.

Hubbard nonetheless continued to perform and record sporadically,

primarily on fluegelhorn rather than on the more demanding trumpet. In

his last years he worked mostly with the trumpeter David Weiss, who

featured Mr. Hubbard as a guest artist with his group, the New Jazz

Composers Octet, on albums released under Mr. Hubbard’s name in 2001 and

2008, and at occasional nightclub engagements.

Mr.

Hubbard won a Grammy Award for the album “First Light” in 1972 and was

named a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master in 2006.

He is survived by his wife of 35 years, Briggie Hubbard, and his son, Duane.

Mr.

Hubbard was once known as the brashest of jazzmen, but his personality

as well as his music mellowed in the wake of his lip problems. In a 1995

interview with Fred Shuster of Down Beat, he offered some sober advice

to younger musicians: “Don’t make the mistake I made of not taking care

of myself. Please, keep your chops cool and don’t overblow.”

A version of this article appears in print on , on Page A18 of the New York edition with the headline: Freddie Hubbard, Jazz Trumpeter, Is Dead at 70.

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/goings-on/freddie-hubbard-r-i-p

http://www.suzannepittson.com/hubreviews.html

The New York City Jazz Record (October 2010)

Although he’s considered one of jazz’s greatest trumpeters, Freddie Hubbard is not generally viewed as a composer or as one whose songs are often sung. He had success with “Up Jumped Spring,” and “Little Sunflower,” but, otherwise, his originals have tended to remain challenging instrumentals.

Vocalist Suzanne Pittson, who considers Hubbard one of her most important influences, met the trumpeter in 2008 (a few months before he died) and gained permission to record several of his songs with new lyrics written by her and/or her husband, pianist Jeff Pittson. Out of the Hub features the singer, Jeff Pittson and an all-star group: bassist John Patitucci, drummer Willie Jones III, and on five of the 11 songs, trumpeter Jeremy Pelt and saxophonist Steve Wilson.

Three of the performances are jazz or pop standards that Hubbard recorded (“You’re My Everything.” “Moment to Moment,” and Betcha By Golly, Wow!”). Of the eight originals by the trumpeter, six have lyrics by Suzanne, Jeff and/or son Evan Pittson. While “Up Jumped Spring,” which utilizes Abbey Lincoln’s lyrics, is both joyful and conventional, many of the other songs — “Our Own (Gibraltar), “Out of the Hub (One of Another Kind)” and “We’re Having a Crisis (Crisis)” — are not easy to sing. Yet Pittson makes her interpretations sound fairly effortless, both in her often up-tempo melody statements and her scat-filled improvisations.

Sprinkled throughout are notable solos by Pelt, whose playing hints at both the sound and ideas of Hubbard; by the ever-inventive Wilson, who alternates between alto and soprano saxes; and by Patitucci and Jeff Pittson. But the star of the session is Suzanne Pittson. Her voice is particularly lovely on the ballads, even while navigating the complex and haunting vocals of “Bright Sun (Lament for Booker).”

During an era when jazz singers struggle to find fresh repertoire, Suzanne Pittson offers an appealing option with these “new” Freddie Hubbard songs.

http://www.freddiehubbardmusic.com/landing.php

B I O G R A P H Y

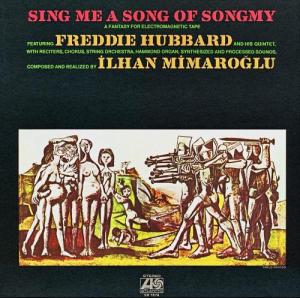

https://cageian.wordpress.com/2013/02/15/ilhan-mimaroglu-freddie-hubbards-sing-me-a-song-of-songmy/

Ilhan Mimaroglu

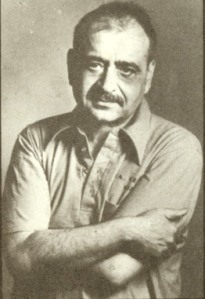

In July last year, the strange story of İlhan Mimaroğlu came to a close due to complications from pneumonia.

The son of a famed Turkish architect, Mimaroğlu moved to New York in the 1950s and eventually became an integral, and relatively undersung inventor and pioneer in the John Cage-championed realm of electronic and avant garde composition exploding behind the scenes in the city at the time. Mimaroğlu thrived as both a composer in his own right, and as a producer and owner of Finnadar Records; working with, recording and releasing works by a wide range of musical titans – including Charles Mingus, John Cage, Edgar Varese and, to somewhat bizarre effect, Freddie Hubbard.

One of Mimaroğlu’s defining characteristics – and arguably his

greatest contribution to 20th century American music – was in his

marriage of jazz with classical avant garde & musique concréte. As

an executive and producer at Atlantic Music, Mimaroğlu worked mostly in

the late-60s and early-70s, recording the likes of Charles Mingus, John

Lee Hooker, and Ornette Coleman, and he kept his expertise and intrigue

with tape music and minimalism somewhat sidelined. Mingus’ Mingus Moves

from 1973 (produced by Mimaroğlu), for example, plays like a relatively

straight-forward post-bop record from the period, albeit with a

slightly more “searching and unpredictable” style. Whereas the unusual Sing Me a Song of Songmy,

made in collaboration with the normally less adventurous Freddie

Hubbard, was an occasion where Mimaroğlu utilised his stature and the

tools at his disposal to create a high-budget piece of avant garde music

– a fusion of post-bop with musique concréte, united by a generally

“anti-war” message, that still doesn’t quite sound like anything that’s

come before or since.

Freddie Hubbard was arguably the only rival to Miles Davis’ crown as jazz’s greatest trumpeter (& flugelhornist) at the close of the 1960s, and while Davis explored modality and the influence of psychedelia and expanding timbral colour on his music with In A Silent Way & Bitches Brew, Hubbard introduced soul and funk in a much more subtle way on his Herbie Hancock-informed 1970s opuses, Red Clay & Straight Life, expanding the pallet of his music, yet still remaining firmly on Earth while Davis explored outer space. Furthermore, Hubbard’s First Light, recorded after Sing Me a Song of Songmy in 1971 saw Hubbard become even less musically adventurous (although still brilliant), injecting string arrangements into the mix in an uncharacteristically high-budget affair, creating an album of soul & big-band influenced fusion. All of which make his involvement in Mimaroğlu’s strange Songmy project all the stranger.

The “Songmy” in Sing Me a Song of Songmy, undoubtedly must refer to “Son My”, a village in South Vietnam and the location of the mass murder, rape and mutilation of some 400 unarmed civilians by the US Army during the tumultuous events of the US’ Vietnam campaign in 1968. The event caused outrage in the States, and was one of the driving factors in the burgeoning anti-war sentiment in the nation that arguably cost the US the war later in the 70s.

As afroementioned, Mimaroğlu’s album can take rank with the multitude of similar anti-war compositions coming out of both popular and jazz music at the time, and furthermore sit comfortably alongside the “Afro” focused music culture of the day, when the likes of Archie Shepp, Melvin van Peebles and Gil Scott-Heron really put the African back into African-American. The record takes the form of a montage, patch-working its pieces together in an almost Dark Side of the Moon fashion.

Album opener, Threnody for Sharon Tate, sees synthesizer

tones, dissonant string arrangements and other processed sounds bed a

rising crescendo of strange recitations about death, music and love –

voices in the heads of the young soldiers sent to murder innocent

Vietnamese. “I feel I can hold a guitar, I know I can hold a know, I think I can kill…” This quickly segues into This Combat I Know,

a track that starts as a relatively straight-forward post-bop,

piano-led romp by Hubbard & his Quintet, before gradually

introducing Mimaroğlu’s own spacey synthesizer work, and ultimately

losing its romp atmosphere and drifting along sparsely morphing from

soulful to jazz to dissonant avant-garde, reintroducing recitations by

Turkish poet, Fazıl Hüsnü Dağlarca (“This is combat, do whatever you want, burn my sky…but don’t burn my prize cows”). This atmosphere of horro-movie dissonance with poetic anti-war recitation continues into The Crowd,

a musique conréte montage littered with moments courtesy of Hubbard’s

quintet as well as the aforementioned string orchestra and the

Barnard-Columbia Chorus, becoming increasingly unhinged like Jazz’s own Lumpy Gravy.

The album’s highlight is arguably the couplet of two shorter pieces – Monodrama and Black Soldier –

that open the LP’s second side. Mimaroğlu creates a processed

atmosphere of reversed horn and synthesizers, while Hubbard improvises a

reverbed bugle call over the madness. This segues nicely into

Stravinsky-esque string arrangements, twisted by Mimaroğlu’s production,

harkening Hubbard himself to recite another Dağlarca passage,

translated into an African-American context.

1 Threnody For Sharon Tate 2:04

2 This Is Combat, I Know 8:57

3 The Crowd 7:03

4 What A Good Time For A Kent State 1:27

Info

Download

Footnotes:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freddie_Hubbard

Frederick Dewayne Hubbard (April 7, 1938 – December 29, 2008) was an American jazz trumpeter.[1] He was known primarily for playing in the bebop, hard bop, and post-bop styles from the early 1960s onwards. His unmistakable and influential tone contributed to new perspectives for modern jazz and bebop.[2]

Then in May 1961, Hubbard played on Olé Coltrane, John Coltrane's final recording session for Atlantic Records. Together with Eric Dolphy and Art Davis, Hubbard was the only sideman who appeared on both Olé and Africa/Brass, Coltrane's first album with Impulse!. Later, in August 1961, Hubbard recorded Ready for Freddie (Blue Note), which was also his first collaboration with saxophonist Wayne Shorter. Hubbard joined Shorter later in 1961 when he replaced Lee Morgan in Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers. He played on several Blakey recordings, including Caravan, Ugetsu, Mosaic, and Free for All. In all, during the 1960s, he recorded eight studio albums as a bandleader for Blue Note, and more than two dozen as a sideman.[4] Hubbard remained with Blakey until 1966, leaving to form the first of several small groups of his own, which featured, among others, his Blue note associate James Spaulding, pianist Kenny Barron and drummer Louis Hayes. This group recorded for Atlantic.

It was during this time that he began to develop his own sound, distancing himself from the early influences of Clifford Brown and Morgan, and won the DownBeat jazz magazine "New Star" award on trumpet.[5]

Throughout the 1960s Hubbard played as a sideman on some of the most important albums from that era, including Oliver Nelson's The Blues and the Abstract Truth, Eric Dolphy's Out to Lunch!, Herbie Hancock's Maiden Voyage, and Wayne Shorter's Speak No Evil.[6] Hubbard was described as "the most brilliant trumpeter of a generation of musicians who stand with one foot in 'tonal' jazz and the other in the atonal camp".[7] Though he never fully embraced the free jazz of the 1960s, he appeared on two of its landmark albums: Coleman's Free Jazz and Coltrane's Ascension, as well as on Sonny Rollins' 1966 "New Thing" track "East Broadway Run Down" with Elvin Jones and Jimmy Garrison.

Hubbard achieved his greatest popular success in the 1970s with a series of albums for Creed Taylor and his record label CTI Records, overshadowing Stanley Turrentine, Hubert Laws, and George Benson.[8] Although his early 1970s jazz albums Red Clay, First Light, Straight Life, and Sky Dive were particularly well received and considered among his best work, the albums he recorded later in the decade were attacked by critics for their commercialism. First Light won a 1972 Grammy Award and included pianists Herbie Hancock and Richard Wyands, guitarists Eric Gale and George Benson, bassist Ron Carter, drummer Jack DeJohnette, and percussionist Airto Moreira.[9] In 1994, Hubbard, collaborating with Chicago jazz vocalist/co-writer Catherine Whitney, had lyrics set to the music of First Light.[10]

In 1977 Hubbard joined with Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams, Ron Carter and Wayne Shorter, members of the mid-sixties Miles Davis Quintet, for a series of performances. Several live recordings of this group were released as V.S.O.P, V.S.O.P. The Quintet, V.S.O.P. Tempest in the Colosseum (all 1977) and V.S.O.P. Live Under the Sky (1979).[2]

Hubbard's trumpet playing was featured on the track "Zanzibar", on the 1978 Billy Joel album 52nd Street (the 1979 Grammy Award Winner for Best Album). The track ends with a fade during Hubbard's performance. An "unfaded" version was released on the 2004 Billy Joel box set My Lives.

Following a long setback of health problems and a serious lip injury in 1992 where he ruptured his upper lip and subsequently developed an infection, Hubbard was again playing and recording occasionally, even if not at the high level that he set for himself during his earlier career.[11] His best records ranked with the finest in his field.[12]

On December 29, 2008, Hubbard died in Sherman Oaks, California from complications caused by a heart attack he suffered on November 26.[13]

Freddie Hubbard had close ties to the Jazz Foundation of America in his later years. He is quoted as saying, "When I had congestive heart failure and couldn't work, The Jazz Foundation paid my mortgage for several months and saved my home! Thank God for those people."[14] The Jazz Foundation of America's Musicians' Emergency Fund took care of him during times of illness. After his death, Hubbard's estate requested that tax-deductible donations be made in his name to the Jazz Foundation of America.[14]

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/goings-on/freddie-hubbard-r-i-p

Freddie

Hubbard, who was perhaps the most skillful, fluent, and versatile jazz

trumpeter of the nineteen-sixties, died yesterday, at age seventy. Old

enough to be raised on bebop and young enough to assimilate heady

avant-garde stylings, he was a high-flying sideman for Art Blakey and

also the answer to a fascinating trivia question: who was the only

musician to appear on both Ornette Coleman’s “Free Jazz” and John

Coltrane’s “Ascension,” the era’s two most celebrated large-group

settings for collective improvisation? Hubbard’s own dates as a leader,

most of them for Blue Note, stuck close to the hard-bop tradition of

harmonically intricate reframings of the blues. His debut as a leader,

“Open Sesame,” from 1960, finds him ideally paired with the great,

short-lived tenor saxophonist Tina Brooks, who returned the favor six

days later and had Hubbard alongside him for the album “True Blue.”

Perhaps his single greatest recorded performance was as a sideman on Herbie Hancock’s “Maiden Voyage,” which features, in effect, Miles Davis’s quintet with Hubbard in Davis’s stead. After a decade in the haze of fusion, Hubbard returned to a changed jazz world; his lip injury in 1992 curtailed his playing in recent years. This clip, from 1963, of the twenty-five-year-old Hubbard with Blakey (and the powerful bassist Reggie Workman), displays his clarion-bright tone, amazingly rapid articulation, adventuresome chromaticism, and sure sense of drama.

Perhaps his single greatest recorded performance was as a sideman on Herbie Hancock’s “Maiden Voyage,” which features, in effect, Miles Davis’s quintet with Hubbard in Davis’s stead. After a decade in the haze of fusion, Hubbard returned to a changed jazz world; his lip injury in 1992 curtailed his playing in recent years. This clip, from 1963, of the twenty-five-year-old Hubbard with Blakey (and the powerful bassist Reggie Workman), displays his clarion-bright tone, amazingly rapid articulation, adventuresome chromaticism, and sure sense of drama.

http://www.suzannepittson.com/hubreviews.html

REVIEWS / OUT OF THE HUB: THE MUSIC OF FREDDIE HUBBARD

The New York City Jazz Record / Andrew Vélez / October 2010

L.A. Jazz Scene / Scott Yanow / March 2011

All About Jazz / Wilbert Sostre / March 2011

Jazz Inside New York / Bob Gish

JazzTimes (March 2011)

Pasatiempo / Paul Weideman / March 2011

Jazz Weekly / George W. Harris / September 2011

JAZZIZ / Mark Holston / Spring 2011

L.A. Jazz Scene / Scott Yanow / March 2011

All About Jazz / Wilbert Sostre / March 2011

Jazz Inside New York / Bob Gish

JazzTimes (March 2011)

Pasatiempo / Paul Weideman / March 2011

Jazz Weekly / George W. Harris / September 2011

JAZZIZ / Mark Holston / Spring 2011

The New York City Jazz Record (October 2010)

Andrew Vélez

Her voice is a high and sweet soprano. She can

scat like nobody’s business. There’s some kinship with the sound of

Diane Schuur but warmer. She credits John Coltrane, Carmen McRae and

Sarah Vaughan as her influences, but like all genuinely innovative

musicians, Suzanne Pittson’s creativity, musicianship and

improvisational skills are off and away on their own, ably demonstrated

in the company of her fine band. Out of the Hub: The Music of Freddie

Hubbard, Pittson’s third recording, salutes one of her musical heroes

and mentors. One cannot speak of Hubbard and his technically virtuosic

trumpeting and composing without mentioning his participation in two

seminal 1960 classics, Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz and, shortly

thereafter, Oliver Nelson’s Blues and the Abstract Truth. The latter was

saluted by and the title of Pittson’s first recording.

The opener, “Our Own” (based on “Gibraltar”), a

Hubbard tune with Catherine Whitney lyrics, gets things off at a

swinging pace. Sounding a bit like a vocalese cousin to the Annie Ross

of the Lambert, Hendricks and Ross days, Pittson is light and fun as

trumpeter Jeremy Pelt swings behind her husband Jeff Pittson’s sharp

company on piano, solid have-a-goodtime music. Another Hubbard tune is

the meditative “Up Jumped Spring”, with characteristically beautiful

lyrics by the late Abbey Lincoln. The swinging is at a gentler pace,

with Pittson’s piano and Willie Jones III’s brushes making for

empathetic company. Pittson sings her own lyrics to Hubbard’s “Like A

Byrd” (“Byrd Like”) and “We’re Having a Crisis” (“Crisis”), appealingly

scatting, floating, soaring and speeding along. Her fun with the music

is clear, irresistible and still further evidence that we have a fresh

new jazzbird to celebrate.

L.A. Jazz Scene (March 2011)

by Scott Yanow

Suzanne Pittson, a fine vocalist who is a

superior scat singer, is based in New York. On Out Of The Hub, she

performs eight Freddie Hubbard compositions and three other songs that

the late great trumpeter had recorded. For five of the numbers she (and

often her husband keyboardist Jeff Pittson) wrote new lyrics, two of

which include vocalese based on Hubbard's recorded solos. Using an

all-star group (Jeff Pittson, bassist John Patitucci, drummer Willie

Jones III. and, on five of the songs, trumpeter Jeremy Pelt and Steve

Wilson on alto and soprano), Suzanne Pittson holds her own with her

illustrious sidemen and does Hubbard's music justice. To sing such tunes

as “Gibraltar,” “One Of Another Kind” and “Crisis” is not an easy task,

but she makes it sound natural, swinging all the way and improvising

within Hubbard's style. Highly recommended and available from

www.suzannepittson.com.

All About Jazz (March 2011)

By Wilbert Sostre

The vocalese and scatting tradition is alive and

well in singer Suzanne Pittson. With “Out of the Hub: The Music of

Freddie Hubbard,” Pittson continues to establish herself as one of the

best singers on today’s jazz scene.

Out of the Hub includes tunes written by or

associated with trumpet legend Freddie Hubbard, with Pittson writing or

co-writing five lyrics, which Hubbard approved just three months before

his passing in 2008.

To honor Hubbard, Pittson recruited a group of

extraordinaire musicians, including trumpeter Jeremy Pelt and bassist

John Patitucci, who add – along with saxophonist Steve Wilson and the

rest of Pittson’s quintet – dazzling improvisations throughout.

More than just a singer, Suzanne Pittson is a

jazz musician. With a fluid phrasing and stunning tone, Pittson uses

her voice as another instrument, improvising and playing with the

melodies. Pittson’s striking sense of melody and amazing vocal range

allow her to express a vast palette of colors and txtures on swinging

tracks like “True Vision,” “You’re My Everything” and “We’re Having a

Crisis,” and on ballads including “Bright Sun,” “Moment to Moment” and

“Betcha by Golly, Wow!” Following in the steps of the great Ella

Fitzgerald, Pittson is also a master of the scatting technique, as shown

on “Our Own” and “Out of the Hub.”

All the arrangements are by pianist/husband Jeff

Pittson, and the cover design is a creation of their son Evan, who also

wrote the lyrics to “Out of the Hub.”

Jazz Inside New York

By Bob Gish

Some controversy exists over just what makes a

jazz vocalist. Listen to Suzanne Pittson and you’ll know. So it’s a

perfect match for her to make a recording devoted exclusively to the

compositions of the inimitable jazz composer and musician Freddie

Hubbard. Pittson does his songs up royally and the musicians on the

project are up to the task too, delivering first rate performances on

every track.

Jeremy Pelt’s trumpet points the way with great

unison lines with Pittson. The other Pittson, husband Jeff on piano,

lives up to the standards of their shared names—and their mutual love of

jazz.

Suzanne Pittson more or less fell in love with

jazz as a teenager when she first heard Freddie Hubbard play with Wayne

Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams. That was an

imprint to last a lifetime, taking Ms. Pittson through classical

training and a graduate degree in music but always leading her back to

jazz and the yearning to perform as a jazz vocalist. Her homage here to

Hubbard is an extension of years of transcribing and singing Hubbard’s

songs and harmonies.

All eleven tracks live up to the genius and

expected quality associated with Hubbard and his legacy. You can’t just

spontaneously sing the songs heard on this recording, and still get the

lyrics out of your mouth in an intelligible way. Improvisation is

another matter and its here in grand order – Pittson’s scatting growing

out of her understanding of theory and the piano.

“Out of the Hub,” the title track is a tour de

force, full of all the runs and riffs of a joyful jazz ride. The same

goes for “Up Jumped Spring,” a personal favorite of this writer’s. But

then who’s to choose, all of the songs here, as conceived and arranged,

sung and played are the stuff to blow you away—much in the same way

Pittson was blown away when she first heard Hubbard when she was a

teenager.

Every musician, of whatever persuasion, can point

to that special time when they knew music would be a large if not the

controlling part of their life. Maybe it’s listening to Johnny Smith at

Eddie’s Lounge in Colorado Springs those many years back which seem as

fresh and recent as yesterday, if not this morning. Each person

provides their own lyrics and memory of of melody.

So there’s an extra benefit to this CD, and

that’s empathizing with Pittson’s inspiration and motivation for Hubbard

as a hero. One could do no better than the result, only a partial

culmination, heard in Pittson’s beautiful vocals. Check out “Bright

Sun” a poignant account of every artist’s, especially jazz artists’

compulsion for epic quest.

JazzTimes (March 2011)

Two albums ago, for her recording debut, vocalist

Suzanne Pittson shaped an appropriately abstract tribut to Oliver

nelson’s essential The Blues and the Abstract Truth. By association,

she also honored one of her foremost jazz heroes, Freddie Hubbard. Now

Pittson, whose intervening project was a penetrating Coltrane

exploration, is back with a full-length salute to Hubbard.

In June 2008, Pittson and her husband

pianist-arranger Jeff Pittson, visited Hubbard and asked permission to

record five of his compositions, refitted with their lyrics. That

September, Hubbard approved their request. Three months later he dies,

making this initiative all the more significant. To paint vocal

canvases that match the power and glory of Hubbard’s work is a tall –

some would say insurmountable order. Pittson’s ability to rise

fearlessly to the challenge goes beyond mere vocal legerdemain,

revealing soul-deep creative empathy. While it takes a true Hubbard

connoisseur to fully grasp the profundity of Pittson’s homage, it only

requires a working pair of ears to appreciate her effervescent

transformation of “Gibraltar” into “Our Own,” or the cunning way in

which she narrows the spectrum of “Crisis” to focus specifically on

romantic tumult or the unimpeded gaiety of her “Up Jumped Spring.”

Of course, none of this magic is achieved

single-handedly. In addition to her husband, Pittson is surrounded with

equally sapient disciples, including trumpeter/flugelhornist Jeremy

Pelt, saxophonist Steve Wilson, bassist John Patitucci and drummer

Willie Jones III.

Pasatiempo (March 2011)

By Paul Weideman

Suzanne Pittson grew up listening to jazz and

loved singing Freddie Hubbard’s solos. Her tribute CD opens with his

composition “Our Own (Gibraltar)” and a bright intro courtesy of soprano

saxophonist Steve Wilson, bassist John Patitucci and drummer Willie

Jones III. Pittson is just reckless enough with her intonation and

rhythmic attack (shades of Flora Purim), works satisfyingly with and

without vibrato, and is a killer scat artist. The song also offers

swell solos by trumpeter Jeremy Pelt and pianist Jeff Pittson, the

singer’s husband. On “Out of the Hub (One of Another Kind),” Jeff

Pittson creates a romantic wash of piano strings, Patitucci sets up a

bouncier beat, Wilson burns, and the singer paints with lyrics penned by

her son, Evan Pittson. She and her husband sought out Hubbard at a New

York jazz club in June 2008 (six months before the jazz veteran died at

age 70) to get his blessing on this and four other songs on which the

Pittsons innovated lyrics. She remembers trumpeter Booker Little on

“Bright Sun,” performing the Hubbard song – “He played with scalar

exhilaration/pushing past the last generation” – with her beautifully

jazz voice and phrasing and a vocalese segment based on Hubbard’s solo

from 1962’s Hub-Tones. Her voice is a virtual horn on “True Visions

(True Colors).” All in all, it’s really cool vocal and instrumental

jazz.

Jazz Weekly (September, 2011)

By George W. Harris

This is the kind of record I like: take a

songbook (in this case, trumpeter Freddie Hubbard’s) and do it with a

completely different instrument, in this case with the soothing voice of

Suzanne Pittson. Oh, sure, she allows some room for Jeremy Pelt’s

trumpet (good call!), as well as Steve Wilson’s saxes, but for the most

part she just lets it ride with the rhythm team of Jeff Pittson/p, John

Patitucci/b and Willi Jones III/dr for literally lyrical takes of “Byrd

Like,” “Lament For Booker” (done in vocalese) and “Up Jumped Spring.”

The two horns provide excellent framework on an exciting “Gibraltar” and

assertive “Crisis” with Pittson executing the tricky course with grace

and clarity. A fitting tribute to not only the great late trumpeter, but

to the art of singing.

JAZZIZ — Sing a Song of Freddie: Suzanne Pittson pays

vocal tribute to an integral influence. (Spring 2011)

Mark Holston

As a graduate student at San Francisco State

University in the 1970s, vocalist Suzanne Pittson set aside her dreams

of becoming a classical pianist when she developed hand problems. But

the classical world’s loss was the jazz world’s gain, as she refocused

on the improvisor’s art.

Not that she was a stranger to the genre. Her

family had listened to jazz while she was growing up. And when Pittson

chose to devote herself to jazz, she thought back to an artist whose

music she had fallen in love with years before: Freddie Hubbard. The

trumpeter and composer, whose songs she vocally interprets on her album

Out of the Hub: The Music of Freddie Hubbard (Vineland), provided the

perfect point of entry.

“I just wanted to learn the jazz language,”

recalls Pittson of her initial foray into the world of improvisational

music. “I couldn’t seem to make the switch as a pianist, so it made

sense to start singing. I started writing out solos, and Freddie’s

recordings were among the first that I was interested in. HIs harmonic

concept and his language as a soloist have always intrigued me. He was

so strong as a soloist, you could almost say he had no peers. I’d go to

hear him and was always blown away.”

“Byrdlike” was one of the first Hubbard

originals she tackled , its degree of difficulty establishing a high

standard for what would follow. “That set my goal, which was to learn

how to sing the jazz language like a horn,” she reflects. “I was

studying how approached different chords, and what he did was very

complex.”

Now teaching jazz-vocal studies at the City

College of New York, Pittson never forgot her crucial, early influence.

Her fascination with Hubbard, who died in late 2008, is reflected in the

lovingly rendered and stylistically expansive survey of his music on

Out of the Hub. The CD features husband Jeff Pittson’s arrangements and

keyboards, along with an A-list band, comprising trumpeter and

flugelhorn player Jeremy Pelt, alto saxophonist Steve Wilson, bassist

John Patitucci and drummer Willie Jones III.

Out of the Hub comes more than a decade after

Pittson first experimented with singing the works of another jazz giant

on Resolution: A Remembrance of John Coltrane. With the Hubbard project,

however, the singer was able to meet the source of her inspiration.

Visiting the trumpeter at the Iridium Jazz Club in New York City,

Pittson obtained his blessing to add lyrics to tunes such as “Crisis,”

“The Melting Pot” and the aforementioned “Byrdlike.” Contributions by

Jeff and their 18-year-old son, Evan, made it truly a family effort.

With no prompting, violist and bassist Evan simply presented his mother

with lyrics to the title tune, based on Hubbard’s “One of Another

Kind.”

Organizing the recording session before she had

to return to classroom in the fall of 2008—and before her dream

bandmates scattered—created some last-minute drama. Although Hubbard had

been flattered by the singer’s attention, he still harbored some

doubts.

“Jeremy Pelt told me that Freddie had actually

called him to find out more about me.” Pittson say “And he said, “I

don’t see how a singer is going to be able to do my music!” Pittson had

previously sent several sets of her lyrics, but he hadn’t responded.

Then, a week before the scheduled recording date, he asked to hear a

demo of her singing the tunes. That prompted a mad scramble to lay down

barebones, home-studio versions of several pieces and get them in the

trumpeter’s hands.

“Two weeks later, Freddie approved our lyrics,”

she remembers with a tinge of remorse. “He said that he looked forward

to hearing it, but he passed away on December 29th, before that was

possible. He was a mentor, and it was a great honor to me that he

approved of and was enthusiastic about what I was doing.”

JAZZIZ (Spring 2011)

Scott Yanow

Although he’s considered one of jazz’s greatest trumpeters, Freddie Hubbard is not generally viewed as a composer or as one whose songs are often sung. He had success with “Up Jumped Spring,” and “Little Sunflower,” but, otherwise, his originals have tended to remain challenging instrumentals.

Vocalist Suzanne Pittson, who considers Hubbard one of her most important influences, met the trumpeter in 2008 (a few months before he died) and gained permission to record several of his songs with new lyrics written by her and/or her husband, pianist Jeff Pittson. Out of the Hub features the singer, Jeff Pittson and an all-star group: bassist John Patitucci, drummer Willie Jones III, and on five of the 11 songs, trumpeter Jeremy Pelt and saxophonist Steve Wilson.

Three of the performances are jazz or pop standards that Hubbard recorded (“You’re My Everything.” “Moment to Moment,” and Betcha By Golly, Wow!”). Of the eight originals by the trumpeter, six have lyrics by Suzanne, Jeff and/or son Evan Pittson. While “Up Jumped Spring,” which utilizes Abbey Lincoln’s lyrics, is both joyful and conventional, many of the other songs — “Our Own (Gibraltar), “Out of the Hub (One of Another Kind)” and “We’re Having a Crisis (Crisis)” — are not easy to sing. Yet Pittson makes her interpretations sound fairly effortless, both in her often up-tempo melody statements and her scat-filled improvisations.

Sprinkled throughout are notable solos by Pelt, whose playing hints at both the sound and ideas of Hubbard; by the ever-inventive Wilson, who alternates between alto and soprano saxes; and by Patitucci and Jeff Pittson. But the star of the session is Suzanne Pittson. Her voice is particularly lovely on the ballads, even while navigating the complex and haunting vocals of “Bright Sun (Lament for Booker).”

During an era when jazz singers struggle to find fresh repertoire, Suzanne Pittson offers an appealing option with these “new” Freddie Hubbard songs.

http://www.freddiehubbardmusic.com/landing.php

Freddie Hubbard

B I O G R A P H Y

In

the pantheon of jazz trumpeters, Freddie Hubbard stands as one of the

boldest and most inventive artists of the bop, hard-bop and post-bop

eras. Although influenced by titans like Miles Davis and Clifford Brown,

Hubbard ultimately forged his own unique sound – a careful balance of

bravado and subtlety that fueled more than fifty solo recordings and

countless collaborations with some of the most prominent jazz artists of

his era. Shortly after his death at the end of 2008, Down Beat

called him “the most powerful and prolific trumpeter in jazz.” Embedded

in his massive body of recorded work is a legacy that will continue to

influence trumpeters and other jazz artists for generations to come.

Hubbard

was born on April 7, 1938, In Indianapolis, Indiana. As a student and

band member at Arsenal Technical High School, he demonstrated early

talents on the tuba, French horn, and mellophone before eventually

settling on the trumpet and flugelhorn. He was first introduced to jazz

by his brother, Earmon, Jr., a piano player and a devotee of Bud Powell.

Hubbard’s

budding musical talents caught the attention of Lee Katzman, a former

sideman of Stan Kenton. Katzman convinced the young trumpeter to study

at the Arthur Jordan Conservatory of Music with Max Woodbury, the

principal trumpeter of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra.

As

a teenager, Hubbard worked and recorded with the Montgomery Brothers –

Wes, Monk and Buddy. His first recording session was for an album called

The Montgomery Brothers and Five Others. Around that same time,

he also assembled his first band, the Jazz Contemporaries, with bassist

(and manager) Larry Ridley, saxophonist/flutist James Spaulding, pianist

Walt Miller and drummer Paul Parker. The quintet became recurring

players at George’s Bar, the well known club on Indiana Avenue.

In

1958, Hubbard moved to New York at age 20 and quickly established

himself as one of the bright young trumpeters on the scene, astonishing

critics and fans alike with the depth and maturity of his playing.

Within the first two years of his arrival in the Big Apple, he landed

gigs with veteran jazz artists Philly Joe Jones, Sonny Rollins, Slide

Hampton and Eric Dolphy. He joined Quincy Jones in a tour of Europe that

stretched from 1960 to 1961.

https://secretsociety.typepad.com/darcy_james_argues_secret/2008/12/rip-freddie-hubbard.html

https://secretsociety.typepad.com/darcy_james_argues_secret/2008/12/rip-freddie-hubbard.html

30 December 2008

Freddie Hubbard: The Show Must Go On

The blue-neon sign of the Iridium Jazz Club glowed softly

behind Freddie Hubbard. The legendary trumpeter wore a yellow-straw

fedora, a gold tie and a tailored dark suit with a handkerchief peeking

out of the jacket pocket. He was celebrating his 70th birthday in New

York two-and-a-half months late by leading an all-star octet that

included some of his longest-standing collaborators, among them Curtis

Fuller, Louis Hayes and James Spaulding.

On “Jodo,” the first tune of the second set on June 28, the bandleader picked up his silver flugelhorn, which had been resting on Larry Willis’ piano. Hubbard played a short passage that had the slashing phrasing of the original 1965 Blue Note recording.

But the notes that filled that phrasing came out cracked, strangled and far from their intended pitch. Hubbard held the horn horizontally at waist level and stared at it quizzically, as if there were something wrong with it. He didn’t see anything, so he tried the solo again. Again the notes sputtered off-pitch. Obviously frustrated, Hubbard cut his solo short and motioned for his old friend Spaulding to take over.

The evening was meant to showcase the hard-bop great’s return to active duty. He had a new album with the New Jazz Composers Octet, On the Real Side (Times Square), and a spate of newspaper and magazine articles suggesting that he had largely recovered from the health problems that had marred his playing since 1992. But Hubbard himself knew better. You could tell from the way he winced that the notes coming out of his horn were far different from the notes he heard in his head. There was nothing wrong with his ears; his embouchure was the problem.

His sharp ears were obvious as his bandmates soloed on “Jodo.” Hubbard moved gingerly, the result of severe back problems, but he punched the air with the rhythmic accents of his composition. During the head of the next tune, “Little Sunflower,” he barked out that the chord was A, not E. Music director David Weiss looked puzzled, but saxophonist Javon Jackson pointed at the score on the music stand. Hubbard was right. The bandleader cheered on the adventurous solos by Jackson and Willis, beaming with pleasure at hearing his music played as he heard it in his head. But when he picked up the flugelhorn again, there were more winces.

What kind of special agony is it to be mentally sharp, as Hubbard obviously is, and unable to physically execute the sounds you can so clearly imagine? What must it be like to still harbor the fire for making music and yet be constantly dissatisfied with the results?

“What I play is not too bad,” Hubbard said defensively a few days later. “It was all right. It wasn’t like I was 100 percent; I was tired.” Then he grew combative, asserting, “The young cats can’t play what I play. My stuff is way ahead; they don’t play with the chordal sense that I do; they don’t know nothing about that. I’ve got more maturity than they’ve got, even though my chops are down.”

Those chops are what once made his reputation. Between 1958, when he first arrived in New York from Indianapolis, and 1992, when he suffered a devastating lip injury, Hubbard could play the trumpet as fast and as hard, as agilely and as accurately, as anyone on the planet. Just listen to the records he made as a leader for Blue Note and Impulse in the ’60s, the solos he played on records by Art Blakey, Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy and Wayne Shorter in the same decade, the hits he had with CTI in the ’70s.

On his 1961 album, Ready for Freddie, Hubbard unveiled “Birdlike,” his tribute to Charlie Parker, with a bravura trumpet solo that machine-gunned notes across several octaves at a dizzying, Parker-like tempo pushed along by Elvin Jones. Each note, whether a piercing 16th or a bluesy quarter, was precisely pitched and crisply articulated. When Hubbard played the same song at Iridium this year, he attempted the same solo on flugelhorn, but the pitch was hit-and-miss and the articulation uncertain.

“I don’t have the embouchure and strength I had when I was 25,” Hubbard admitted before the gig. “You realize you’re getting older and can’t do the same thing you once did. Miles once told me, ‘You can’t play like that forever; you have to find something you’re comfortable with.’ That’s what I’m looking for.

“The most difficult thing for me is to say to myself, ‘You can’t do what you used to do,’ and to find a way to play, so I’m still happy with it and the audience is still happy with it. People know what I used to sound like, but they appreciate that I’m still trying. Maybe they’re just coming out to see if I’m still alive. Maybe they’re saying, ‘He’s still alive; let’s see how far he can go.'”

I arrived at the Buckingham Hotel in midtown Manhattan at 5 p.m. and a barefoot Hubbard opened his door wearing nothing but a white Los Angeles Marathon T-shirt and a pair of blue-and-white plaid shorts. He immediately crawled back into bed and did the interview with his head tilted sideways atop two pillows. He catalogued all his physical ailments.

“I’ve been through so much,” he lamented, “in addition to my lip problems. I had congestive heart failure a few years ago, and I also had something cut out of my lung. Last year, all of a sudden, my neck got stiff, and my doctor said I have a pinched nerve between my second and third vertebrae. That’s probably the most serious of all, because it affects the way I walk and move.”

He sounded like nothing so much as an aging athlete, bewildered that the same body that brought him so many triumphs had now betrayed him. It echoed those moments when an aging Cal Ripken Jr. would flail in vain at a grounder to his left, or when an aging Sammy Sosa would swing at a fast ball just after it had passed him.

We don’t usually compare trumpeters to athletes. After all, horn players stand in one place onstage for a few hours a day-what can be so physically demanding about that? Hubbard insists, however, that the bodily toll is similar, especially for trumpeters. And he has the injuries to prove it.

“Just like an athlete,” he argues, “your bones get tired unless you move just right. Like an athlete, you’re trying to be a little bit better than the next guy, so you push yourself a bit harder. A trumpeter pushes that metal mouthpiece against his lip, squeezing it against his teeth; the more he presses the louder and harder he can play.

“I always played with too much pressure because I felt I needed it to get that feel I wanted. You want to stay in the pocket, but the drums are usually so loud that you have to play really hard to be heard over them. That leads to injuries, but like an athlete, a musician can’t wait to get back out there and start playing again. You feel good so you take the jobs, but then it hurts again because it didn’t have time to heal.”

Young musicians, like young athletes, feel indestructible. Both are encouraged by their teammates and managers to shake off aches and pains and to keep playing as hard as they can. For years Hubbard would get blisters on his lips, but he’d keep playing and they’d go away. As he got older, however, he noticed that all the older trumpeters had scar tissue.

“I once asked Miles, ‘What are those spots on your lips?'” Hubbard recalled. “He said, ‘That’s from blowing the horn.’ Then I noticed that Harry James had spots on his lips. I did this ‘Satchmo Tour’ in Russia, and they had this big photo of Louis [Armstrong] behind the stage. I’d look up at that picture and the scar on his lip was in the same place as mine. It drilled me every time I saw it.

“I heard stories about Louis. The crowd would be cheering and hollering, so he would overexert himself. Instead of playing two choruses, he’d play four or five or 10. The same thing happened to me. You get caught up in the moment; you want to play with the same intensity as the drummer, so you play too loud and too long. But lips are very delicate, I’ve learned-there are a lot of different muscles in there. I didn’t realize how hard I was blowing. I thought I was the strongest trumpet player in the world, but that shit caught up with me.”

So what should Hubbard have done earlier in his career? It’s hard to say. If he had played it safe, he’d be healthier and have better chops today. But if he had played it safe, he might never have become the extraordinary player he did. Even as a teenager in the mid-’50s, he wowed his elders.

“I was in the Army in 1954,” recalled Spaulding. “I was stationed at Fort Harris in Indiana, and I met Freddie at a Saturday afternoon jam session at the Cotton Club in Indianapolis when he was 16 and I was a year older. He was one of the most talented musicians I’d ever heard. Even then he was fiery and had a flair about him, that outgoing personality. He had perfect pitch; he’d hear someone’s car blowing in the street and tell you what note it was.”

When Hubbard first arrived in New York from Indianapolis as a 20-year-old in 1958, his prodigious ability quickly landed him jobs with Sonny Rollins, Philly Joe Jones, Slide Hampton and J.J. Johnson.

“Imagine me, a kid, with those giants,” he exclaimed, the astonishment still in his voice 50 years later. “I could hardly play for listening. They’d start and-whoosh-they’d be gone. I’d say, ‘How’d you do that? How’d you come up with that?’ Then I figured out that they did it by listening to the guys before them. A lot of what Sonny and Trane were playing was no different than what Lester Young played; they just played with more intensity.

“Prez would sit there in his chair with his horn out to the side and it was so lovely. That’s what I need to figure out how to do now. Ben Webster was the same way. I played with him once at a jazz festival in Norway in the ’80s, and he’d sit there playing so lightly, but he had tears in his eyes because it was so beautiful. I had tears in my eyes too.”

Like every other young trumpeter in the late ’50s, Hubbard was an imitator of Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis and Clifford Brown. To distinguish himself from his contemporaries (most notably Lee Morgan, Booker Little and Donald Byrd), Hubbard needed a different sound.

“I started practicing with tenor players,” he revealed. “I’d hear what Rollins and Trane would do, and their passages were so involved, so hip, that I figured it’d make me sound different. But passages that come naturally to a saxophonist don’t come easy to a trumpeter. You need a lot of elasticity, because your embouchure is so different than a tenor player’s.

“You can’t play a trumpet as long as you can a tenor, because the mouthpiece is against your lips while the tenor’s mouthpiece is inside your lips. If you’re going to play lots of choruses like Trane and Sonny, you have to be really strong. When I practiced with Sonny, he’d have me lift weights to build up my strength.”

When he mastered the challenge of playing those long, slipping and sliding tenor passages with the brassy attack of the trumpet, Hubbard had a sound like no one else. He further refined it by eschewing the dominant trumpet tone of the time.

“Most trumpeters back then had a pinched sound, like tee-tee-tee,” he pointed out, “but Clifford Brown had an open sound, more like doo-doo-doo. It’s harder to control an open sound than a pinched sound, so most trumpeters avoid it, but I had played tuba, French horn and E-flat mellophone in school, and I was used to a larger mouthpiece. You have to blow a certain way to get that sound, but I figured it out. It’s difficult to control when you open up that wide, but if you can, you sound like no one else.”

“He always had the confidence to experiment and try things,” Spaulding added. “He was able to funnel all these different trumpet players, all the way from Louis Armstrong down to Dizzy and Miles, until he found his own voice. That’s what I think this music is all about, finding your own voice. When you heard Trane, you knew it was Trane. When you heard Dizzy, you knew it was Dizzy. When you heard Freddie, you knew it was Freddie.”

The combination of the Rollins-like phrasing and the Brown-like openness gave Hubbard a one-of-a-kind voice on the horn. That voice attracted Art Blakey, who made the trumpeter a Jazz Messenger from 1961 through 1966. That voice dominated Hubbard’s own recordings as a leader, most memorably Ready for Freddie, Breaking Point and The Artistry of Freddie Hubbard. That voice earned Hubbard a key role on such landmark recordings as Herbie Hancock’s Maiden Voyage, Wayne Shorter’s Speak No Evil, John Coltrane’s Ascension and Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz.