WADADA LEO SMITH

Featuring the Musics and aesthetic Visions of:

CINDY BLACKMAN

(March 23-29)

RUTH BROWN

(March 30-April 5)

JOHN LEWIS

(April 6-12)

JULIUS EASTMAN

(April 13-19)

PUBLIC ENEMY

(April 20-26)

WALLACE RONEY

(April 27-May 3)

MODERN JAZZ QUARTET

(May 4-10)

DE LA SOUL

(May 11-17)

(May 11-17)

KATHLEEN BATTLE

(May 18-24)

WYNTON MARSALIS

(May 25-31)

(May 25-31)

RHIANNON GIDDENS

(June 1-7)

DON PULLEN

(June 8-14)Don Pullen

(1941-1995)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

Don Pullen

developed a surprisingly accessible way of performing avant-garde jazz.

Although he could be quite free harmonically, with dense, dissonant

chords, Pullen

also utilized catchy rhythms, so even his freest flights generally had a

handle for listeners to hang on to. The combination of freedom and

rhythm gave him his own unique musical personality.

Pullen, who came from a musical family, studied with Muhal Richard Abrams (with whom he played in the Experimental Band) and, in 1964, made his recording debut with Giuseppi Logan. In the 1960s, he recorded free duets with Milford Graves, led his own bands, and played organ with R&B groups, backing Big Maybelle and Ruth Brown, among others. Although he worked with Nina Simone (1970-1971) and Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers (1974), Pullen became famous as the pianist with Charles Mingus' last great group (1973-1975). From 1979-1988, he co-led a notable inside/outside quartet with tenor saxophonist George Adams that was in some ways an extension of Mingus' band. In later years, Pullen led his African-Brazilian Connection and recorded with Kip Hanrahan, Roots, John Scofield, David Murray, Mingus Dynasty, and Jane Bunnett,

among others. His last project found the always searching pianist

seeking to fuse jazz with traditional Native American music. Although

his life was too short, Don Pullen

fortunately did make a fair amount of recordings as a leader, including

for Sackville (1974), Horo, Black Saint, Atlantic (his funky "Big

Alice" became a near-standard), and Blue Note.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/donpullen

Don Pullen developed an extended technique for the piano and a strikingly individual style, post-bop and modern, but retaining a strong feeling for the blues. He produced acknowledged masterworks of jazz in a range of formats and styles, crossing and mixing genres long before this became almost commonplace. By chance, unfortunately for his future commercial success if not for his musical development, his first contact on arriving on the New York scene was with the free players of the 1960s, with whom he recorded. It was some years later before his abilities in more straight ahead jazz playing, as well as free, were revealed to a larger audience. The variety in his music made him difficult to pigeonhole, but he always displayed a vitality that at first hearing could shock but would always engross and delight his audience.

Don Gabriel Pullen was born (on 25th December 1941 not in 1944 as sometimes said) and raised in Roanoke, Virginia, USA. Growing up in a musical family, he learned the piano at an early age, played and worked with the choir in his local church, and was heavily influenced by his cousin, professional jazz pianist Clyde “Fats” Wright. He had some lessons in classical piano but knew little of jazz, being mainly aware of church music and the blues. Don sought to play in a very fast style and managed to develop his own unorthodox technique allowing him to execute extremely fast runs while maintaining the melodic line.

Don left Roanoke for Johnson C. Smith University in North Carolina to study for a medical career but soon he realised that his only true vocation was music. After playing with local musicians and being exposed for the first time to records of the major jazz musicians and composers he abandoned his medical studies. He set out to make a career in music, desirous of playing like Ornette Coleman and Eric Dolphy.

In 1964 he went to Chicago for a few weeks where he encountered Muhal Richard Abrams' philosophy of making music, then headed for New York, where he was soon introduced to avant-garde saxist Guiseppi Logan, and absorbed more of the philosophy of creative music. Logan invited Don to play piano on his two record dates, 'Guiseppi Logan'(October 1964) and 'More Guiseppi Logan' (May 1965) on ESP, both exercises in structured free playing. Although these were Guiseppi Logan's recordings, most critical attention was given to the playing of percussionist Milford Graves and the unknown Don Pullen with his astonishing mastery of his instrument.

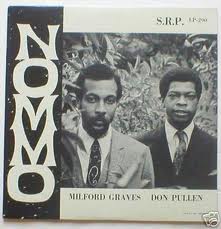

Subsequently he and Milford Graves formed a duo and their piano and drums concert at Yale University in May 1966 was recorded. They formed their own independent SRP record label to publish the result as two LPs. These were the first records to bear Don Pullen's name, second to Milford's. Although not greatly known in the United States, these avant-garde albums were well received in Europe and most copies were sold there. These have never been reissued after the first run sold out.

Finding little money in playing avant-garde jazz, Don began to play the Hammond organ to extend his opportunities for work, transferring elements of his individual piano style to this instrument. During the remainder of the 1960s and early the 1970s, he played with his own organ trio in clubs and bars, worked as self- taught arranger for record companies, and accompanied various singers, including Arthur Prysock and Nina Simone.

He suffered at this time, and for a long time after, from two undeserved allegations; the first (despite his grounding in the church and blues) that he was purely a free player and thus unemployable in any other context, the second that he had been heavily influenced by Cecil Taylor or was a clone of Cecil Taylor, to whose playing Don's own bore a superficial resemblance. Don strenuously denied that he had any link with Cecil Taylor, stating that his own style had been developed in isolation before he ever heard of Cecil. But the assertion of Cecil's influence continued to the end of Don's life, and persists even to this day.

He appeared on no more commercial recordings until 1971 and 1972 when he played organ on three recordings by blues altoist Williams, one being issued under the title of a Pullen composition, “Trees And Grass And Things”. In 1973 drummer Roy Brooks introduced Don to bassist Charles Mingus, and after a brief audition he took over the vacant piano chair in the Mingus group; when a tenor saxophone player was needed, Don recommended George Adams; subsequently Dannie Richmond returned on drums; and these men, together with Jack Walrath on trumpet, formed the last great Mingus group.

Being part of the Mingus group and appearing at many concerts and on three Mingus studio recordings, 'Mingus Moves' (1973), 'Changes One' and 'Changes Two' (both 1974), gave great exposure to Don's playing and helped to persuade audiences and critics that Pullen was not just a free player. Two of his own compositions 'Newcomer' and 'Big Alice' were recorded on the 'Mingus Moves' session but 'Big Alice' was not released until a CD re- issue many years later. However musical disagreements with Mingus caused Don to leave the group in 1975. Don had always played piano with bass and drums behind him, feeling more comfortable this way, but in early 1975 he was persuaded to play a solo concert in Toronto. This was recorded and as 'Solo Piano Album' became the first record issued under Don's name alone. Among other pieces, it contains 'Sweet (Suite) Malcolm' declared a masterpiece by Cameron Brown, Don's long time associate of later years.

There was now growing awareness of Don's abilities but it was the European recording companies that were prepared to preserve it. In 1975 an Italian record company gave Don, George Adams and Dannie Richmond the opportunity to each make a recording under his own name. All three collaborated in the others' recordings. In the same year, Don made two further solo recordings in Italy for different record labels; 'Five To Go' and 'Healing Force', the latter being received with great acclaim. He became part of the regular seasonal tours of American musicians to Europe, playing in the avant-garde or free mode. In 1977, Don was signed by a major American jazz record company, Atlantic. This led to two records, the untypical 'Tomorrow's Promises' and the live 'Montreux Concert'. But after these, Don's association with Atlantic was terminated and he returned to European companies for three recordings under his own name or in partnership; 'Warriors', and 'Milano Strut' in '78 and 'The Magic Triangle' in '79. These, especially the startling 'Warriors' with its strong 30 minute title track, have remained in the catalogues over the years.

Meanwhile he recorded with groups led by Billy Hart (drums), Hamiet Bluiett, (baritone sax.), Cecil McBee (bass), Sunny Murray (drums) and Marcello Melis (bass). On the formation of the first Mingus Dynasty band Don occupied the piano chair and appeared on their recording 'Chair In The Sky' in 1979, but he soon left the band, feeling the music had diverged too far from Mingus' intentions. In late 1979 Don, George Adams and Dannie Richmond were booked to play as a quartet for a European tour of a few weeks duration. Don invited Cameron Brown to join them on bass. They were asked to bill themselves as a Mingus group but not wanting to be identified as mere copyists they declined and performed as the George Adams/Don Pullen Quartet. They played more structured music than Don normally favoured, but the immediate rapport among them led to the group touring the world with unchanged personnel until the death of Dannie Richmond in early 1988. From very early in their first tour in 1979, and until 1985, the quartet made a dozen remarkable recordings for European labels, both studio and live. Of these, 'Earth Beams' (1980), 'Live At The Village Vanguard' (1983) and 'Decisions' (1984) provide typically fine examples of their work at that period. Although highly regarded in Europe, the quartet felt they were not well enough known in America so in 1986 they signed to record for the American Blue Note label for which they recorded 'Breakthrough' (1986) and 'Song Everlasting' (1987). Beginning the Blue Note contract with great hope of increased fame and success, (as shown by the title of their first Blue Note album) they became disillusioned by the poor availability of these two records. Although the power of their live concerts maintained their reputation as one of the most exciting groups ever seen, the music recorded for the Blue Note sessions was at first deemed 'smoother' than on their European recordings, and took time to achieve the same high reputation.

After the death of Dannie Richmond the quartet fulfilled their remaining contracted engagements with a different drummer and then disbanded in mid 1988. Their music, usually original compositions by Don, George and Dannie, had ranged from blues, through ballads, to post- bop and avant-garde. The ability of the players to encompass all these areas, often within one composition, removed any sameness or sterility from the quartet format. Except for the early recordings on the vanished Horo label, their European recordings remained regularly available, unlike those made for Blue Note.

During the life of the Quartet, Don also made a duo recording with George Adams 'Melodic Excursions' (1982) and made three recordings under his own name, two further solo albums, the acclaimed 'Evidence Of Things Unseen' (1983) and 'Plays Monk' (1984), then with a quintet, another highly praised recording 'The Sixth Sense' (1985). He also recorded with (alphabetically) Hamiet Bluiett; Roy Brooks, the drummer who introduced him to Mingus; Jane Bunnett; Kip Hanrahan; Beaver Harris; Marcello Melis; and David Murray.

All Don's future recordings under his own name would now be for Blue Note. On 16th December 1988 he went into the studio with Gary Peacock (bass) and Tony Williams (drums) to make his first trio album 'New Beginnings', which astonished even those familiar with his work and became widely regarded as one of the finest trio albums ever recorded. He followed this in 1990 with another trio album 'Random Thoughts', in somewhat lighter mood, this time with James Genus (bass) and Lewis Nash (drums).

In late 1990 Don added a new element to his playing and his music with the formation of his African Brazilian Connection ('ABC'). This featured, as well as Don, Carlos Ward (alto sax), Nilson Matta (bass), Guilherme Franco and Mor Thiam (percussion) in a group which mixed African and Latin rhythms with Jazz. Their exciting first album “Kele Mou Bana” was released in 1991. Their second, but very different, album of 1993, 'Ode To Life' was a tribute to George Adams, who had died on 14th November 1992, containing Don's heartfelt and moving composition in George's memory 'Ah George We Hardly Knew Ya'. A third album 'Live .... Again' recorded in July 1993 at the Montreux festival, but not released until 1995. This featured 'Ah George...' and other songs from their previous albums, in somewhat extended versions. Don achieved more popular and commercial success with this group than with any other. In 1993 'Ode To Life' was fifth on the U.S. Billboard top jazz album chart.

During the last few years of his too short life, Don toured with his trio, with his African Brazilian Connection, as a solo artist, and with groups led by others, making much fine music, but sadly not enough records. The greatest loss to his admirers was that although his solo playing seemed to grow in power, he was never invited to record another solo album. Meanwhile he made important contributions to concerts and recordings of groups led by others, such as (alphabetically) Jane Bunnett (notably their fine Duo album 'New York Duets); Bill Cosby(!); Kip Hanrahan; David Murray (on organ, the best recorded example of his organ style being on Murray's 1991 'Shakill's Warrior'); Maceo Parker (on organ); Ivo Perelman; Jack Walrath (again on organ). He also toured and recorded with the group 'Roots' from its inception.

Don's final project was a work combining the music of his African Brazilian Connection (extended by Joseph Bowie on trombone) with a choir and drums of Native Americans. In 1994 Don was diagnosed with the lymphoma which eventually ended his life but, despite this, he put great physical effort into completing the this important and deeply felt composition. In early March 1995 he played on the recording 'Sacred Common Ground', displaying all his usual power although being but a few weeks away from his untimely death, returning as always to his heritage of the blues and the church. Unable himself to play at the live premiere, his place at the piano was taken by D D Jackson, with whom Don discussed the music from his hospital bed shortly before his death. He died on 22nd April 1995.

Don composed many pieces with melodies and rhythms which linger in the mind, often they were portraits or memories of people he knew. All were published by his own company Andredon but because he himself for a long time suffered from neglect musically so did many of his compositions. His most well known are the humorous 'Big Alice' (for an imaginary fan), the incredible 'Double Arc Jake' (for his son and Rahsaan Roland Kirk), the passionate 'Ode To Life' (for a friend), and the aforementioned lament 'Ah George We Hardly Knew Ya'. Occasionally he wrote pieces with a religious feeling, such as 'Gratitude' and 'Healing Force', or to highlight the plight of Afro-Americans such as 'Warriors', 'Silence = Death, and 'Endangered Species: African American Youth'. Following the assassination of Afro-American activist Malcolm X, Don had written a suite dedicated to Malcolm's memory but this required more instrumental resources than a normal jazz group provides, and only the piano parts of this were ever recorded. Except for the 'Plays Monk' album, Don almost exclusively featured his own compositions on his own recordings, until his time with the African Brazilian Connection. His compositions are well represented on the George Adams/Don Pullen Quartet recordings, but such compositions by Don which were recorded by others, were usually performed by those who had known and worked with him.

Although Don was able to play the piano in almost any style, (the attribute that had made him so important to the wide-ranging music of Mingus) and sometimes gave the impression that there were two pianists at the keyboard, he caused most astonishment by his ability to place extremely precise singing runs or glissandi over heavy chords, reminiscent of traditional blues, while never losing contact with the melodic line. His technique for creating these runs, where he seemed to roll his right hand over and over along the keys, received much comment from critics, was studied by pianists, and heavily filmed and investigated, but could never be totally explained, even by Don who had developed it. His piano technique can be seen on the DVDs 'Mingus At Montreux 1975' and on 'Roots Salutes The Saxophones'. But it is better not to concentrate too much on his technique, especially now that he is gone from among us, and to pay attention to his depth of feeling and the intensity of improvisations, whether these were suggested by the song itself or engendered by the moment. It is easy to forget that those who come to love his music from his records may be totally unaware of his playing method. Even at his concerts, only a minority of the audience would be fully able to see his hands moving along the keyboard and be aware of exactly how he revealed the emotional outpourings of his soul.

Don Pullen, like many other of greatest jazz musicians, had given his life to the music and was greatly missed after his death. Several musicians wrote songs as personal tributes to his memory, including Jane Bunnett, Cameron Brown, D D Jackson, and David Murray.

David Murray and D D Jackson made a whole album 'The Long Goodbye' dedicated to Don.

In 2005 Mosaic issued a set of four long unavailable Blue Note recordings, 'Breakthrough' and 'Song Everlasting' by the 'The Don Pullen/George Adams Quartet, and 'New Beginning' and 'Random Thoughts' by Don's own trio.

Source: Mike Bond

http://www.donpullen.de/collect/coda.htm

Don Pullen: An Interview by Vernon Frazer HOME

The following interview was published first in the jazz magazine "coda", October 1976, Toronto, Canada. Photographs by Bill Smith.

Vernon Frazer: In 1966 I heard you play on a Giuseppi Logan album and read several reviews of your performances and recordings with Milford Graves. After that, I didn't see your name mentioned until about 1972, when you joined Charles Mingus' band. What did you do during those years? Apparently you received very little publicity.

Don Pullen: During that time the music critics were especially adverse to what they called the New Music, Avant Garde or whatever. After the period with Milford Graves, I worked with a trio around New York, had an organ group and played for a lot of singers. I just made it any way I could and still stay in music.

V.F.: How did you join Mingus?

D.P.: Roy Brooks recommended me. Mingus just called me and I made the gig.

V.F.: And you stayed with him for three years?

D.P.: Approximately.

V.F.: Why did you decide to leave Mingus?

D.P.: Personal reasons. It was just time to go, time to leave.

V.F.: Do you want to be more specific ?

D.P.: I would rather not, right now.

V.F.: During the time you played with him, did Mingus influence you in any way?

D.P.: No. Before I met Mingus, I was playing virtually the same way I play now. My way of playing had to be a little more contained with him because of the form of the tunes, the changes and so forth. I had to stay within a certain framework to do justice to his tunes, you see. lf I had ventured to play them the way I think they should be played, there might have been a little conflict.

V.F.: What have you been doing since you left his band?

D.P.: I've been doing a few things. I've recorded for an Italian label, a European label, done solo concerts up in Canada. I've worked with a trio here in New York, using Bobby Battle on drums and Alex Blake, whenever he's available, on bass.

V.F.: In the mid-sixties you and Milford Graves recorded, produced and distributed an album by yourselves. Why did you choose this over the more conventional avenues of recording?

D.P.: For awhile, the critics and record producers were turning thumbs down on the New Music and the New Musicians. Milford and I were having difficulty getting recorded, as I am even today. We weren't getting any play from the White Establishment. They were only recording those they felt were more Establishment-inclined, so we just decided to do it ourselves. During that time, you see, the lack Revolution was happening. The social and political aspects made it just about the right time for us to go into this venture. Musicians were thinking about controlling their own music. We weren't going to sit back and wait on the Man to say, "Well, here. Take this crumb." We said, "We'll do it ourselves." That was the impetus. We did a concert at Yale, decided to record it and try to do it ourselves, to expose ourselves. And we were successful to a very big degree, you know. We sold a lot of records, we got our name out there. We achieved what we set out to do.

V.F.: Were any other opportunities for recording available at that time, possibly through ESP Records or through Bill Dixon, when he was at Savoy?

D.P.: I came to New York, I think, a little bit after Bill Dixon and the Savoy thing. I did record two albums for ESP with Giuseppi Logan but I never did an album for him under my own name. Bernard Stollman, by that time, had - has even now- a lot of good music. He recorded everybody, all the cats. Some of it he released, some of it he didn't.

V.F.: When you put out your own record, did you hope to attract the attention of a major Jazz label?

D.P.: Not really. We were mainly concerned with trying to build our own company and eventually control our own music. When I traveled with Mingus and even now, wherever I go, people always ask about the record. Milford and I get letters now, every day, from people asking where they can get the record. We only did two. I think eventually we're going to have to reissue both albums. One avenue might be to lease the masters to a larger company. There's a lot of headaches, a lot of trouble, in trying to take care of the business and play also. lt would be easier for another company to put it on the market.

V.F.: How did you handle the distribution of the record?

D.P.: We went into mail order. We got some play from the music magazines Downbeat, Jazz, all the major Jazz magazines. Different music critics would write about, you know, and people would write in and ask for it. Some distributors in Europe and Japan asked for five hundred or a thousand copies. But in the U.S. we never had any distribution to speak of. We sold more records in Europe and Japan than we did in the States.

V.F.: lt seems you've recorded more outside the States than you have inside.

D.P.: Yeah. I've got three in Europe and one in Canada in 1975, you know, and can't get a record date in America.

V.F.: Why can't you get a record date here?

D.P.: I have no idea. I don't think they like me here. I think they're trying to run me out of the country. (Laughs) I don't know, man. I really don't know. I have certain opinions I might venture, but I really can't say.

V.F.: Would you put out your own record now, if you felt it was necessary?

D.P.: If I felt it was necessary, I would do it. Like I said, I really don't want the headache of doing it. I enjoy the work that's involved, but I would prefer to let somebody else do it while I concentrate on the music. The machinery that's necessary, the distribution, is a major problem with any venture such as producing. You have to have world-wide distribution. It means collecting your money - all this takes a big operation to be really big, you know? If necessary, I do it on a small level - you know, myself. And I'm almost to that point now. I've done it before, so I can do it again.

V.F.: Although independent recording has received less publicity than it did during the sixties, it seems that, in recent years, the number of musicians who release their own work on their own labels has increased. Do you think these musicians are acting on the same motivation as you and Graves?

D.P.: Yeah. The same things. In fact, a lot of the cats that are trying to produce their own records today come to us from time to time for advice, to see how we did it. They're doing it their own way, but I think Milford and I, during the sixties, were pioneers in that aspect of doing it yourself. Of course, other musicians have done it before: Sun Ra, Mingus. But during that time, we were the youngest cats out there and it was like phenomenal for two young dudes to be doing it, you see. So it inspired other cats to say, "Yeah, we'll try it too."

V.F.: Over the past decade, what changes do you think have taken place in the New Music?

D.P.: Looking back and comparing then with now, I don't see that real drive. Like, cats were I hate to just say "into it", but that's the best I can explain - they were into it. It was like a community, you know, even though they might be separated for miles. Nowadays, I think they're going more towards the Jazz-Rock - that bullshit, you know - trying to sound like Miles. There's no real influence, no leadership, out there. Which is one reason why I think they won't record me. If they ever give me a chance, I'm gonna lay something heavy on 'em and they really don't want anything like that - too heavy - out. The people in power always say, "Well, people don't want to hear this" or "People don't understand it." They're always looking down on people. I think one of the prime purposes of music is enlightenment, to elevate people. Music is supposed to elevate the person. If you always play down to people, they don't move anywhere. For instance, different things I was doing in the sixties I hear cats in Rock doing now. But in the sixties, they said it was nonsense.

V.F.: They didn't understand it at the time.

D.P.: Exactly. And they said, "People can't understand it, they'll never understand it. " But they're doing it. I'm playing basically the same way I've been playing all my life and more and more people are digging it. But what if I had stopped back then? If nobody ever does anything new, if nobody tries to advance the music, then everything is going to become dead. Everything is going to become stagnant. Everybody was talking about "Jazz is Dead " because there was no innovation, there were no new things out. But there were. It was happening, but it wasn't being given to the people. It wasn't being exposed at all. So they said, "Well, it's dead." Damn right it's dead, if you keep playing something over and over for twenty years.

V.F.: The media made it appear dead, although a lot was really going on.

D.P.: Yeah. That's what was happening when the so-called Revolution in Music was happening. They called it the "October Revolution". They used the term "revolution" because there was a call for something new. When I first came to New York in 1964, Bill Dixon had a club - on 96th Street, I think. He was doing that thing and I was there every night. I heard them cats and I said, "Goddamn! What is this shit? What is this here?" That was what I had been looking for, searching for. People used to say I played strange. I really didn't know anybody else who was playing, you know? So when I went there I had heard Eric Dolphy and Ornette - they were the two main influences on me - but aside from them, I didn't know there were many other musicians playing. I said, "Well, this is it. I'm not alone"

V.F.: During that period, the New Musicians were attempting to develop an aesthetic which didn't necessarily require or follow a preconceived structure -

D.P.: That's not true. The critics used to say that because they didn't know what the structure was, what the form was. The form was different, something they never heard, so they said there was no form. They didn't know what it was. On a higher level there is a communication among musicians that gives its own form to what you're doing, you see. This is why I don't like to play with a lot of people. If I do, I like for everybody's head to be in the same direction. That way you can create on that higher level. Like I said, the form, the structure, everything was there. People weren't used to hearing it and so they said there was none. Now, one critic wrote about me and said I didn't have one touch of rhythm at all. He said I didn't have no melody, no rhythm, no nothing. It was dumbass! (Laughs.) He didn't know.

V.F.: Would it be more accurate to say that the New Musicians used a wide variety of structures, sometimes within the same piece, to enhance their expression?

D.P.: Yeah. They used to call it freedom because you were free to do whatever you wanted to do. But that wasn't really now in the sense that, for instance, Mingus' compositions, though from a different era, have always been free. Duke's were like that. Duke used whatever he felt that he should use to express whatever ideas he had, so that was really nothing new. It was just a different way of expressing the same thing. You see, there are no limits to music, to anything. The only limitation is your own mind. If you say, "Well, this is what I want to do," then stop there, that's as far as it's gonna go. But somebody else is gonna say, "No, I can take it a little bit farther than that." Everything builds, one on top of the other, you know. It's like a stack, one up. You just stop whenever you go as high as you want to go. That's the end of it. There's one area of music that if you do get into is very dangerous for your life, but I don't want to get into that. I really don't know much about it.

V.F.: In what ways do you feel your own music has evolved over the years?

D.P.: It's difficult for me to discuss my own music because I've never really satisfied myself. I know that I have done some good things. I think the solo album I did for Sackville is good. I like that more than anything else I've done. But now I don't even like that. I can't say because I'm continually growing. What I played five minutes ago, I won't like the next five.

V.F.: Do you prefer to play solo or with a group?

D.P.: At this point, I enjoy both. When I come out with a group, I do parts of a performance solo and parts of it with the group. I play differently with a group than I do solo. Solo gives me a different kind of freedom of expression than with a group. For example, Song Played Backwards. I started at the end and played it backwards.

V.F.: What was the song?

D.P.: I didn't have a title for it. I played it by myself, you know, so I just...played it backwards. (Laughs.) There are different ways of doing things. I just felt like doing it, so I did it. When I solo, it's only my mind. You can do anything you want to do with a group, you know. Like I said, you set your own limitations. When I play with a group, I have another kind of freedom of expression because I have the other minds, the other vibrations of the musicians working, you see. There's interplay. You have to consider them and they have to consider you. So a group adds another aspect to the music. I enjoy both, you know, and it doesn't matter to me if I play solo or with somebody else.

V.F.: Have you performed any of your solo pieces in a group setting?

D.P.: No, I haven't. Some of them are not adaptable to groups. At least, I haven't figured out a way to do it. I imagine I can. Some I just like to play solo. Richard's Tune is one of my favorites. It's adaptable to group or trio or whatever, but I prefer to play it solo. The Malcolm piece is part of a suite which has seven or eight different...tunes, I guess you'd call them. The only one that I can play solo is the one I recorded, Malcolm, Memories and Gunshots. That's the only one that's adaptable to piano. The rest of it is integrated into the full wide spectrum - small group, strings, full orchestra.

V.F.: Then you've written for large ensembles, also?

D.P.: Yeah, I used to be Arranger and Conductor for King Records a few years back. That was also in the sixties. Not jazz things, but for singers: Arthur Prysock, Irene Reid.

V.F.: In recent years, jazz musicians have recorded solo piano albums more frequently than they have in the past. Why do you think this is happening?

D.P.: I really don't know, but it's nothing new. Tatum did it. Monk has done it. Duke. On one cut I remember, Eric Dolphy played solo saxophone - God Bless The Child, I believe. Solo isn't really new, you know. My cousin, who was a big influence on my playing - Clyde "Fats" Wright used to tell me that unless you could play solo, you couldn't play at all. I think every piano player has to. If you sit home and practise, you develop a way of playing solo, anyway. I think more people are becoming aware of the beauty of just piano alone. Classical music, you know, has solo concerts, so it's not strange for jazz to do the same thing. It's always been there.

V.F.: Do you think the increase in solo piano recordings could be, in part, a reaction to the increased use of electronic keyboard instruments?

D.P.: I don't know. I don't deal with electronics too much. I don't know anything about them, really. I've played electric piano, but I think all those things will pass, you know. It's not real, it's not the real thing. I break up electric pianos, so I can't play them. I have to be very careful with them or else they won't last ten minutes. My own piano is in such bad shape, man, that I've been trying to tune it myself. I'm ashamed to call a tuner over here to try to fix it. So I need something sturdy.

V.F.: An electric piano wouldn't lend itself to your percussive style of playing.

D.P.: It doesn't lend itself at all. It doesn't have the sound, the overtones - I make use of overtones. The electric piano. Well, there can't be. There might be electronic ones. But I don't think I want to get into that.

V.F.: In your solo pieces, you sometimes play the strings inside the piano. Did you learn this formally or pick it up on your own?

D.P.: I did it on my own. My technique is my own. I don't know if anybody can teach you to play strings. You have to do it yourself, find out where they are and play them.

V.F.: When you improvise, do you consciously move "inside" or "outside", as the terms are customarily used?

D.P.: No, I wouldn't say so. It depends on the particular composition that I'm playing. If I'm playing a tune with a set structure, say the structure is "in" and I want to move "out", then I don't consciously say that I want to move "out". I try to let the flow of the music direct me. If you feel it's going in a particular direction, don't force it. Other times it might be necessary to force it in some direction, whatever it is. If you don't feel like you're getting what you want out of the music, then you have to force it. We have to get out of the concept of "in " and "out ". I might say, "This cat is out, " but I don't mean it in the sense of "as a way of playing". There's no such thing as playing "in " or "out ". It's a way of playing. Period. It's just what you feel, how you're playing. You have to let it move you, instead of moving yourself. There's no feeling of what to do next, or whatever. You don't really know what you're going to do next.

V.F.: A number of your compositions appear simple in their melodic content, in that a listener can easily sing the melodies. How does this relate to the complexity of your improvisation? Some musicians use relatively simple compositions because the simplicity allows them more freedom to improvise.

D.P.: Well, the majority of my compositions are about people that I know. Dee Arr is Danny Richmond. Richard is Richard Abrams. And Traceys of Daniel that's my daughter, Tracey Danielle. Melodies are moods, rhythms and feelings that remind me of certain people. I find that within people there's just one thing and that's very simple. Their ways of acting, the things they do, the way they go through certain changes, gets complex. But, basically everything is the same. We come from one source, you know. So that's the way my little melodies come out. And I find that I'm not that complex anyway, so far as music is concerned. Simplicity is very difficult to achieve - to play simple, I mean. Mal Waldron is a good friend of mine. I remember I was at school when I first heard him. It was amazing to me how he could take about four or five notes and play nothing but those four or five, or just play within a scale, and just weave those notes in and out, in and out and still keep building. He's a master of simplicity and there's so much beauty in simplicity. But I can think of a person and play something that would remind me of him. I do things like that.

V.F.: In the sixties, your playing was frequently compared to Cecil Taylor's -

D.P.: That's only dumb critic's talk! When I came to New York, I didn't even know who Cecil Taylor was. In fact, I met Cecil three times over the last ten years and I have never yet heard him play.

V.F.: Not even on records?

D.P.: I've heard one or two records by him. One of them, I think, was at Bill Smith's house in Canada. The last time I saw Cecil was in Switzerland, at Montreux. We talked just about all day, hung out all day together. I got to know him a little better then, but this was about ten years later, you see. He's aware that I don't play like him and I'm aware that he doesn't play like me, either. We appreciate each other, we dig each other as people. I used to purposely avoid him because when I came to New York the first review was, "Don Pullen sounds like Cecil Taylor." If the critics said anything about me, Cecil's name had to be mentioned. Now, I didn't know who this motherfucker was, never even seen him. If he was playing somewhere, I wouldn't go there because I didn't want to sound like anybody. I was insecure in my position because he's been established for twenty or thirty years and I supposedly sounded like him. So I said, 'Whoever he is, I'm gonna stay away from him so that I can be free to develop my own way and go my own way." If I sounded that much like him, as young as I was, then I might have been influenced by him.

V.F.: Which would have been dangerous for your future growth.

D.P.: Yes, of course. So l stayed away from him. As I became secure in my position, that I could play my own way, it didn't matter. So now I consider him a friend and I still don't know what he sounds like. From what I've heard of him, we might have the same way of doing things. But if you play C-D-E-F-G and I play the same thing, it's going to sound different. People haven't tuned their ears to hear the difference between your C and my C. Or maybe they're not taking the time to hear the difference. Cecil's background and my background are so different that we could never possibly sound alike.

V.F.: What is your background? l know Cecil graduated from the New England Conservatory. Their catalogue lists him as one of their Distinguished Alumni although, from what I've read about him, he hated the place.

D.P.: (Laughs.) I imagine he would. He's a free spirit and a very beautiful person. So I imagine that they probably did give him hell. But my background was the Rhythm and Blues, chitterlings circuit and the church.

V.F.: Did you have any conservatory training?

D.P.: No.

V.F.: Any lessons?

D.P.: Oh yeah. The lady across the street was a piano teacher. But that was it. I went to school to become a doctor, but split after awhile. The pull of music, the influence of music, was too great. School was just a diversionary tactic. I knew all along I was going into music. So here I am: got my shingle hanging out and an eviction notice on my door.

V.F.: Some musicians who play Fusion music -

D.P.: Fusion music?

V.F.: Yeah. The Jazz-Rock that Miles is doing, for example.

D.P.: Oh, that's what they call it?

V.F.: That's the most common label for it.

D.P.: Oh yeah?... Fusion music.

V.F.: The fusion of Jazz and Rock.

D.P.: Oh, I see. Okay...Con-fusion.

V.F.: (Laughs.) Anyway, some of the musicians playing Fusion music have openly stated that they're playing to make money so they can survive, as well as invest in the equipment and facilities required to make their music. Do you think you could alter your style to achieve greater commercial success?

D.P.: I could do it easily. It's hard, man, when you see cats out there making a whole bunch of money playin' shit while you're trying to elevate the music and by elevating the music elevate yourself. It's a feather in your cap when you are being true to the music. So it's sort of difficult. I imagine anybody might be tempted to do something. But with me it's only lasted for a minute because I wouldn't be able to live unless I got some sort of satisfaction from the music that I was playing. I would probably die right quick, so there's only one way for me to go. I have to be true to myself and play the music that I feel I'm supposed to play. Otherwise, there's no purpose to it. What have I been doing all these years if I'm gonna sit down and play some shit, some garbage, you know? Then I've wasted half my life because I don't need training, I don't need thought, I don't need mental abilities, I don't need insight, I don't need creative power - I don't need any of that, you dig? I could just sit down and bullshit! If the cats that are doing it feel that's where they belong, then I've got no criticism of them. But a lot of it's more business and greed than anything else.

V.F.: It's difficult for you to get your music heard. What do you do to survive?

D.P.: What do I do? I do the same thing I'm doing now, just make it from day to day and keep my music on a high level. If I take care of the music, it'll take care of me. Then I go out, try to help myself. I don't just lay on my ass. I do whatever is necessary. If I believe in the music like I say I do, then I've got to do something to make the music heard. There's different ways of doing it. But I've managed these years. I might take a gig at the corner bar, playing some funk or fatback, whatever you want to call it, to survive, all for the music. There are bad periods in everyone's life, you know, periods when nothing is happening or happening the way you would like it to. But if you endure those periods, your playing becomes that much stronger. You learn from those periods, gain strength from them and the strength you gain comes out in your music. If you play truthful music, it's going to prevail, no matter what. My music is too good to be ignored, so I'll do whatever I have to do to keep it on a high level and get it out to the people. Like I said, if I take care of the music, the music will take care of me.

https://www.nytimes.com/1995/04/24/obituaries/don-pullen-pianist-53-dies-distinctive-improviser-in-jazz.html

The cause was lymphoma, said Don Lucoff, a publicity representative for Blue Note Records.

Mr. Pullen was one of the most percussive pianists in jazz. His improvisations brimmed with splashed clusters, hammered notes and large two-handed chords. His solos often started out traditionally, with single note lines articulating a composition's harmony, then grew richer with bright explosions of tones. Mr. Pullen used the backs of his hands, or occasionally an elbow; he managed to take techniques from the modern European classical repertory and use them in his music without ever losing a jazz sensibility. Mr. Pullen's importance lies in part in his ability to synthesize so many different forms of expression.

Although Mr. Pullen began as a church pianist and became interested in the work of Art Tatum, he was quickly accepted into the ranks of the avant-garde of the 1960's. In 1965 in New York, he worked with Giuseppe Logan and played for a series of rhythm-and-blues singers including Big Maybelle, Ruth Brown and Arthur Prysock, often using the organ instead of the piano. But his main allegiance was to the free jazz of the era, and he regularly performed with the drummer Milford Graves in the mid-1960's.

In 1973 he began a two-year association with Charles Mingus, who helped introduce Mr. Pullen's style to a wider audience. He was heard on two important albums, "Changes 1" and "Changes 2." Mr. Mingus prized what Mr. Pullen had to offer: a church-driven power, a blues sensibility and a harmonic sophistication.

In the late 1970's and early 80's, he and the drummer Beaver Harris led a rocking group, 360 Degree Music Experience, which included steel drums and the powerful saxophonist Ricky Ford. And in 1979, with the saxophonist and Mingus alumnus George Adams, he started a group that recorded 10 albums over the next decade. Mr. Pullen had begun his own career as a soloist in 1975, recording for the Canadian Sackville label. In the 1970's he recorded for Atlantic Records, among others, and in 1985 he released an exceptional album, "The Sixth Sense," for the Italian label Black Saint. He also regularly worked in clubs.

He continued with a series of stunning albums for Blue Note Records. Some were trio recordings that allowed Mr. Pullen to draw on all his experiences as a musician; the church, rhythm-and-blues, pop and jazz all came out in them, as did his extraordinarily inventive and distinct improvisational style. And he recorded three albums of Brazilian-influenced jazz. Mr. Pullen was still recording and performing several weeks ago, and in early March he finished his last recording, due out next year.

He is survived by his companion, Jana Haimsohn; three sons, Andre, Don and Keith; a daughter, Tracey; his father, Aubrey; a sister, Doris; three brothers, Keith, Aubrey and James, and a granddaughter.

A version of this obituary; biography appears in print on April 24, 1995, on Page B00012 of the National edition with the headline: Don Pullen, Pianist, 53, Dies; Distinctive Improviser in Jazz.

Pianist Don Pullen (1941–1995) was known for his melodic brilliance, swirling chords and glissandos; his kinetic, cascading piano attack could ignite any band. He gained his first experiences playing African-American church music and R&B, and his career took off when he joined Charles Mingus' band in the 1970s. He went on to form his own quartet with saxophonist George Adams.

In this 1989 episode of Piano Jazz, Pullen performs one of his original compositions, "Jana's Delight." He and host Marian McPartland get together for "All The Things You Are."

Originally broadcast in the fall of 1989.

SET LIST:

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/donpullen

Don Pullen

Don Pullen

Don Pullen developed an extended technique for the piano and a strikingly individual style, post-bop and modern, but retaining a strong feeling for the blues. He produced acknowledged masterworks of jazz in a range of formats and styles, crossing and mixing genres long before this became almost commonplace. By chance, unfortunately for his future commercial success if not for his musical development, his first contact on arriving on the New York scene was with the free players of the 1960s, with whom he recorded. It was some years later before his abilities in more straight ahead jazz playing, as well as free, were revealed to a larger audience. The variety in his music made him difficult to pigeonhole, but he always displayed a vitality that at first hearing could shock but would always engross and delight his audience.

Don Gabriel Pullen was born (on 25th December 1941 not in 1944 as sometimes said) and raised in Roanoke, Virginia, USA. Growing up in a musical family, he learned the piano at an early age, played and worked with the choir in his local church, and was heavily influenced by his cousin, professional jazz pianist Clyde “Fats” Wright. He had some lessons in classical piano but knew little of jazz, being mainly aware of church music and the blues. Don sought to play in a very fast style and managed to develop his own unorthodox technique allowing him to execute extremely fast runs while maintaining the melodic line.

Don left Roanoke for Johnson C. Smith University in North Carolina to study for a medical career but soon he realised that his only true vocation was music. After playing with local musicians and being exposed for the first time to records of the major jazz musicians and composers he abandoned his medical studies. He set out to make a career in music, desirous of playing like Ornette Coleman and Eric Dolphy.

In 1964 he went to Chicago for a few weeks where he encountered Muhal Richard Abrams' philosophy of making music, then headed for New York, where he was soon introduced to avant-garde saxist Guiseppi Logan, and absorbed more of the philosophy of creative music. Logan invited Don to play piano on his two record dates, 'Guiseppi Logan'(October 1964) and 'More Guiseppi Logan' (May 1965) on ESP, both exercises in structured free playing. Although these were Guiseppi Logan's recordings, most critical attention was given to the playing of percussionist Milford Graves and the unknown Don Pullen with his astonishing mastery of his instrument.

Subsequently he and Milford Graves formed a duo and their piano and drums concert at Yale University in May 1966 was recorded. They formed their own independent SRP record label to publish the result as two LPs. These were the first records to bear Don Pullen's name, second to Milford's. Although not greatly known in the United States, these avant-garde albums were well received in Europe and most copies were sold there. These have never been reissued after the first run sold out.

Finding little money in playing avant-garde jazz, Don began to play the Hammond organ to extend his opportunities for work, transferring elements of his individual piano style to this instrument. During the remainder of the 1960s and early the 1970s, he played with his own organ trio in clubs and bars, worked as self- taught arranger for record companies, and accompanied various singers, including Arthur Prysock and Nina Simone.

He suffered at this time, and for a long time after, from two undeserved allegations; the first (despite his grounding in the church and blues) that he was purely a free player and thus unemployable in any other context, the second that he had been heavily influenced by Cecil Taylor or was a clone of Cecil Taylor, to whose playing Don's own bore a superficial resemblance. Don strenuously denied that he had any link with Cecil Taylor, stating that his own style had been developed in isolation before he ever heard of Cecil. But the assertion of Cecil's influence continued to the end of Don's life, and persists even to this day.

He appeared on no more commercial recordings until 1971 and 1972 when he played organ on three recordings by blues altoist Williams, one being issued under the title of a Pullen composition, “Trees And Grass And Things”. In 1973 drummer Roy Brooks introduced Don to bassist Charles Mingus, and after a brief audition he took over the vacant piano chair in the Mingus group; when a tenor saxophone player was needed, Don recommended George Adams; subsequently Dannie Richmond returned on drums; and these men, together with Jack Walrath on trumpet, formed the last great Mingus group.

Being part of the Mingus group and appearing at many concerts and on three Mingus studio recordings, 'Mingus Moves' (1973), 'Changes One' and 'Changes Two' (both 1974), gave great exposure to Don's playing and helped to persuade audiences and critics that Pullen was not just a free player. Two of his own compositions 'Newcomer' and 'Big Alice' were recorded on the 'Mingus Moves' session but 'Big Alice' was not released until a CD re- issue many years later. However musical disagreements with Mingus caused Don to leave the group in 1975. Don had always played piano with bass and drums behind him, feeling more comfortable this way, but in early 1975 he was persuaded to play a solo concert in Toronto. This was recorded and as 'Solo Piano Album' became the first record issued under Don's name alone. Among other pieces, it contains 'Sweet (Suite) Malcolm' declared a masterpiece by Cameron Brown, Don's long time associate of later years.

There was now growing awareness of Don's abilities but it was the European recording companies that were prepared to preserve it. In 1975 an Italian record company gave Don, George Adams and Dannie Richmond the opportunity to each make a recording under his own name. All three collaborated in the others' recordings. In the same year, Don made two further solo recordings in Italy for different record labels; 'Five To Go' and 'Healing Force', the latter being received with great acclaim. He became part of the regular seasonal tours of American musicians to Europe, playing in the avant-garde or free mode. In 1977, Don was signed by a major American jazz record company, Atlantic. This led to two records, the untypical 'Tomorrow's Promises' and the live 'Montreux Concert'. But after these, Don's association with Atlantic was terminated and he returned to European companies for three recordings under his own name or in partnership; 'Warriors', and 'Milano Strut' in '78 and 'The Magic Triangle' in '79. These, especially the startling 'Warriors' with its strong 30 minute title track, have remained in the catalogues over the years.

Meanwhile he recorded with groups led by Billy Hart (drums), Hamiet Bluiett, (baritone sax.), Cecil McBee (bass), Sunny Murray (drums) and Marcello Melis (bass). On the formation of the first Mingus Dynasty band Don occupied the piano chair and appeared on their recording 'Chair In The Sky' in 1979, but he soon left the band, feeling the music had diverged too far from Mingus' intentions. In late 1979 Don, George Adams and Dannie Richmond were booked to play as a quartet for a European tour of a few weeks duration. Don invited Cameron Brown to join them on bass. They were asked to bill themselves as a Mingus group but not wanting to be identified as mere copyists they declined and performed as the George Adams/Don Pullen Quartet. They played more structured music than Don normally favoured, but the immediate rapport among them led to the group touring the world with unchanged personnel until the death of Dannie Richmond in early 1988. From very early in their first tour in 1979, and until 1985, the quartet made a dozen remarkable recordings for European labels, both studio and live. Of these, 'Earth Beams' (1980), 'Live At The Village Vanguard' (1983) and 'Decisions' (1984) provide typically fine examples of their work at that period. Although highly regarded in Europe, the quartet felt they were not well enough known in America so in 1986 they signed to record for the American Blue Note label for which they recorded 'Breakthrough' (1986) and 'Song Everlasting' (1987). Beginning the Blue Note contract with great hope of increased fame and success, (as shown by the title of their first Blue Note album) they became disillusioned by the poor availability of these two records. Although the power of their live concerts maintained their reputation as one of the most exciting groups ever seen, the music recorded for the Blue Note sessions was at first deemed 'smoother' than on their European recordings, and took time to achieve the same high reputation.

After the death of Dannie Richmond the quartet fulfilled their remaining contracted engagements with a different drummer and then disbanded in mid 1988. Their music, usually original compositions by Don, George and Dannie, had ranged from blues, through ballads, to post- bop and avant-garde. The ability of the players to encompass all these areas, often within one composition, removed any sameness or sterility from the quartet format. Except for the early recordings on the vanished Horo label, their European recordings remained regularly available, unlike those made for Blue Note.

During the life of the Quartet, Don also made a duo recording with George Adams 'Melodic Excursions' (1982) and made three recordings under his own name, two further solo albums, the acclaimed 'Evidence Of Things Unseen' (1983) and 'Plays Monk' (1984), then with a quintet, another highly praised recording 'The Sixth Sense' (1985). He also recorded with (alphabetically) Hamiet Bluiett; Roy Brooks, the drummer who introduced him to Mingus; Jane Bunnett; Kip Hanrahan; Beaver Harris; Marcello Melis; and David Murray.

All Don's future recordings under his own name would now be for Blue Note. On 16th December 1988 he went into the studio with Gary Peacock (bass) and Tony Williams (drums) to make his first trio album 'New Beginnings', which astonished even those familiar with his work and became widely regarded as one of the finest trio albums ever recorded. He followed this in 1990 with another trio album 'Random Thoughts', in somewhat lighter mood, this time with James Genus (bass) and Lewis Nash (drums).

In late 1990 Don added a new element to his playing and his music with the formation of his African Brazilian Connection ('ABC'). This featured, as well as Don, Carlos Ward (alto sax), Nilson Matta (bass), Guilherme Franco and Mor Thiam (percussion) in a group which mixed African and Latin rhythms with Jazz. Their exciting first album “Kele Mou Bana” was released in 1991. Their second, but very different, album of 1993, 'Ode To Life' was a tribute to George Adams, who had died on 14th November 1992, containing Don's heartfelt and moving composition in George's memory 'Ah George We Hardly Knew Ya'. A third album 'Live .... Again' recorded in July 1993 at the Montreux festival, but not released until 1995. This featured 'Ah George...' and other songs from their previous albums, in somewhat extended versions. Don achieved more popular and commercial success with this group than with any other. In 1993 'Ode To Life' was fifth on the U.S. Billboard top jazz album chart.

During the last few years of his too short life, Don toured with his trio, with his African Brazilian Connection, as a solo artist, and with groups led by others, making much fine music, but sadly not enough records. The greatest loss to his admirers was that although his solo playing seemed to grow in power, he was never invited to record another solo album. Meanwhile he made important contributions to concerts and recordings of groups led by others, such as (alphabetically) Jane Bunnett (notably their fine Duo album 'New York Duets); Bill Cosby(!); Kip Hanrahan; David Murray (on organ, the best recorded example of his organ style being on Murray's 1991 'Shakill's Warrior'); Maceo Parker (on organ); Ivo Perelman; Jack Walrath (again on organ). He also toured and recorded with the group 'Roots' from its inception.

Don's final project was a work combining the music of his African Brazilian Connection (extended by Joseph Bowie on trombone) with a choir and drums of Native Americans. In 1994 Don was diagnosed with the lymphoma which eventually ended his life but, despite this, he put great physical effort into completing the this important and deeply felt composition. In early March 1995 he played on the recording 'Sacred Common Ground', displaying all his usual power although being but a few weeks away from his untimely death, returning as always to his heritage of the blues and the church. Unable himself to play at the live premiere, his place at the piano was taken by D D Jackson, with whom Don discussed the music from his hospital bed shortly before his death. He died on 22nd April 1995.

Don composed many pieces with melodies and rhythms which linger in the mind, often they were portraits or memories of people he knew. All were published by his own company Andredon but because he himself for a long time suffered from neglect musically so did many of his compositions. His most well known are the humorous 'Big Alice' (for an imaginary fan), the incredible 'Double Arc Jake' (for his son and Rahsaan Roland Kirk), the passionate 'Ode To Life' (for a friend), and the aforementioned lament 'Ah George We Hardly Knew Ya'. Occasionally he wrote pieces with a religious feeling, such as 'Gratitude' and 'Healing Force', or to highlight the plight of Afro-Americans such as 'Warriors', 'Silence = Death, and 'Endangered Species: African American Youth'. Following the assassination of Afro-American activist Malcolm X, Don had written a suite dedicated to Malcolm's memory but this required more instrumental resources than a normal jazz group provides, and only the piano parts of this were ever recorded. Except for the 'Plays Monk' album, Don almost exclusively featured his own compositions on his own recordings, until his time with the African Brazilian Connection. His compositions are well represented on the George Adams/Don Pullen Quartet recordings, but such compositions by Don which were recorded by others, were usually performed by those who had known and worked with him.

Although Don was able to play the piano in almost any style, (the attribute that had made him so important to the wide-ranging music of Mingus) and sometimes gave the impression that there were two pianists at the keyboard, he caused most astonishment by his ability to place extremely precise singing runs or glissandi over heavy chords, reminiscent of traditional blues, while never losing contact with the melodic line. His technique for creating these runs, where he seemed to roll his right hand over and over along the keys, received much comment from critics, was studied by pianists, and heavily filmed and investigated, but could never be totally explained, even by Don who had developed it. His piano technique can be seen on the DVDs 'Mingus At Montreux 1975' and on 'Roots Salutes The Saxophones'. But it is better not to concentrate too much on his technique, especially now that he is gone from among us, and to pay attention to his depth of feeling and the intensity of improvisations, whether these were suggested by the song itself or engendered by the moment. It is easy to forget that those who come to love his music from his records may be totally unaware of his playing method. Even at his concerts, only a minority of the audience would be fully able to see his hands moving along the keyboard and be aware of exactly how he revealed the emotional outpourings of his soul.

Don Pullen, like many other of greatest jazz musicians, had given his life to the music and was greatly missed after his death. Several musicians wrote songs as personal tributes to his memory, including Jane Bunnett, Cameron Brown, D D Jackson, and David Murray.

David Murray and D D Jackson made a whole album 'The Long Goodbye' dedicated to Don.

In 2005 Mosaic issued a set of four long unavailable Blue Note recordings, 'Breakthrough' and 'Song Everlasting' by the 'The Don Pullen/George Adams Quartet, and 'New Beginning' and 'Random Thoughts' by Don's own trio.

Source: Mike Bond

http://www.donpullen.de/collect/coda.htm

Don Pullen: An Interview by Vernon Frazer HOME

The following interview was published first in the jazz magazine "coda", October 1976, Toronto, Canada. Photographs by Bill Smith.

Vernon Frazer: In 1966 I heard you play on a Giuseppi Logan album and read several reviews of your performances and recordings with Milford Graves. After that, I didn't see your name mentioned until about 1972, when you joined Charles Mingus' band. What did you do during those years? Apparently you received very little publicity.

Don Pullen: During that time the music critics were especially adverse to what they called the New Music, Avant Garde or whatever. After the period with Milford Graves, I worked with a trio around New York, had an organ group and played for a lot of singers. I just made it any way I could and still stay in music.

V.F.: How did you join Mingus?

D.P.: Roy Brooks recommended me. Mingus just called me and I made the gig.

V.F.: And you stayed with him for three years?

D.P.: Approximately.

V.F.: Why did you decide to leave Mingus?

D.P.: Personal reasons. It was just time to go, time to leave.

V.F.: Do you want to be more specific ?

D.P.: I would rather not, right now.

V.F.: During the time you played with him, did Mingus influence you in any way?

D.P.: No. Before I met Mingus, I was playing virtually the same way I play now. My way of playing had to be a little more contained with him because of the form of the tunes, the changes and so forth. I had to stay within a certain framework to do justice to his tunes, you see. lf I had ventured to play them the way I think they should be played, there might have been a little conflict.

V.F.: What have you been doing since you left his band?

D.P.: I've been doing a few things. I've recorded for an Italian label, a European label, done solo concerts up in Canada. I've worked with a trio here in New York, using Bobby Battle on drums and Alex Blake, whenever he's available, on bass.

V.F.: In the mid-sixties you and Milford Graves recorded, produced and distributed an album by yourselves. Why did you choose this over the more conventional avenues of recording?

D.P.: For awhile, the critics and record producers were turning thumbs down on the New Music and the New Musicians. Milford and I were having difficulty getting recorded, as I am even today. We weren't getting any play from the White Establishment. They were only recording those they felt were more Establishment-inclined, so we just decided to do it ourselves. During that time, you see, the lack Revolution was happening. The social and political aspects made it just about the right time for us to go into this venture. Musicians were thinking about controlling their own music. We weren't going to sit back and wait on the Man to say, "Well, here. Take this crumb." We said, "We'll do it ourselves." That was the impetus. We did a concert at Yale, decided to record it and try to do it ourselves, to expose ourselves. And we were successful to a very big degree, you know. We sold a lot of records, we got our name out there. We achieved what we set out to do.

V.F.: Were any other opportunities for recording available at that time, possibly through ESP Records or through Bill Dixon, when he was at Savoy?

D.P.: I came to New York, I think, a little bit after Bill Dixon and the Savoy thing. I did record two albums for ESP with Giuseppi Logan but I never did an album for him under my own name. Bernard Stollman, by that time, had - has even now- a lot of good music. He recorded everybody, all the cats. Some of it he released, some of it he didn't.

V.F.: When you put out your own record, did you hope to attract the attention of a major Jazz label?

D.P.: Not really. We were mainly concerned with trying to build our own company and eventually control our own music. When I traveled with Mingus and even now, wherever I go, people always ask about the record. Milford and I get letters now, every day, from people asking where they can get the record. We only did two. I think eventually we're going to have to reissue both albums. One avenue might be to lease the masters to a larger company. There's a lot of headaches, a lot of trouble, in trying to take care of the business and play also. lt would be easier for another company to put it on the market.

V.F.: How did you handle the distribution of the record?

D.P.: We went into mail order. We got some play from the music magazines Downbeat, Jazz, all the major Jazz magazines. Different music critics would write about, you know, and people would write in and ask for it. Some distributors in Europe and Japan asked for five hundred or a thousand copies. But in the U.S. we never had any distribution to speak of. We sold more records in Europe and Japan than we did in the States.

V.F.: lt seems you've recorded more outside the States than you have inside.

D.P.: Yeah. I've got three in Europe and one in Canada in 1975, you know, and can't get a record date in America.

V.F.: Why can't you get a record date here?

D.P.: I have no idea. I don't think they like me here. I think they're trying to run me out of the country. (Laughs) I don't know, man. I really don't know. I have certain opinions I might venture, but I really can't say.

V.F.: Would you put out your own record now, if you felt it was necessary?

D.P.: If I felt it was necessary, I would do it. Like I said, I really don't want the headache of doing it. I enjoy the work that's involved, but I would prefer to let somebody else do it while I concentrate on the music. The machinery that's necessary, the distribution, is a major problem with any venture such as producing. You have to have world-wide distribution. It means collecting your money - all this takes a big operation to be really big, you know? If necessary, I do it on a small level - you know, myself. And I'm almost to that point now. I've done it before, so I can do it again.

V.F.: Although independent recording has received less publicity than it did during the sixties, it seems that, in recent years, the number of musicians who release their own work on their own labels has increased. Do you think these musicians are acting on the same motivation as you and Graves?

D.P.: Yeah. The same things. In fact, a lot of the cats that are trying to produce their own records today come to us from time to time for advice, to see how we did it. They're doing it their own way, but I think Milford and I, during the sixties, were pioneers in that aspect of doing it yourself. Of course, other musicians have done it before: Sun Ra, Mingus. But during that time, we were the youngest cats out there and it was like phenomenal for two young dudes to be doing it, you see. So it inspired other cats to say, "Yeah, we'll try it too."

V.F.: Over the past decade, what changes do you think have taken place in the New Music?

D.P.: Looking back and comparing then with now, I don't see that real drive. Like, cats were I hate to just say "into it", but that's the best I can explain - they were into it. It was like a community, you know, even though they might be separated for miles. Nowadays, I think they're going more towards the Jazz-Rock - that bullshit, you know - trying to sound like Miles. There's no real influence, no leadership, out there. Which is one reason why I think they won't record me. If they ever give me a chance, I'm gonna lay something heavy on 'em and they really don't want anything like that - too heavy - out. The people in power always say, "Well, people don't want to hear this" or "People don't understand it." They're always looking down on people. I think one of the prime purposes of music is enlightenment, to elevate people. Music is supposed to elevate the person. If you always play down to people, they don't move anywhere. For instance, different things I was doing in the sixties I hear cats in Rock doing now. But in the sixties, they said it was nonsense.

V.F.: They didn't understand it at the time.

D.P.: Exactly. And they said, "People can't understand it, they'll never understand it. " But they're doing it. I'm playing basically the same way I've been playing all my life and more and more people are digging it. But what if I had stopped back then? If nobody ever does anything new, if nobody tries to advance the music, then everything is going to become dead. Everything is going to become stagnant. Everybody was talking about "Jazz is Dead " because there was no innovation, there were no new things out. But there were. It was happening, but it wasn't being given to the people. It wasn't being exposed at all. So they said, "Well, it's dead." Damn right it's dead, if you keep playing something over and over for twenty years.

V.F.: The media made it appear dead, although a lot was really going on.

D.P.: Yeah. That's what was happening when the so-called Revolution in Music was happening. They called it the "October Revolution". They used the term "revolution" because there was a call for something new. When I first came to New York in 1964, Bill Dixon had a club - on 96th Street, I think. He was doing that thing and I was there every night. I heard them cats and I said, "Goddamn! What is this shit? What is this here?" That was what I had been looking for, searching for. People used to say I played strange. I really didn't know anybody else who was playing, you know? So when I went there I had heard Eric Dolphy and Ornette - they were the two main influences on me - but aside from them, I didn't know there were many other musicians playing. I said, "Well, this is it. I'm not alone"

V.F.: During that period, the New Musicians were attempting to develop an aesthetic which didn't necessarily require or follow a preconceived structure -

D.P.: That's not true. The critics used to say that because they didn't know what the structure was, what the form was. The form was different, something they never heard, so they said there was no form. They didn't know what it was. On a higher level there is a communication among musicians that gives its own form to what you're doing, you see. This is why I don't like to play with a lot of people. If I do, I like for everybody's head to be in the same direction. That way you can create on that higher level. Like I said, the form, the structure, everything was there. People weren't used to hearing it and so they said there was none. Now, one critic wrote about me and said I didn't have one touch of rhythm at all. He said I didn't have no melody, no rhythm, no nothing. It was dumbass! (Laughs.) He didn't know.

V.F.: Would it be more accurate to say that the New Musicians used a wide variety of structures, sometimes within the same piece, to enhance their expression?

D.P.: Yeah. They used to call it freedom because you were free to do whatever you wanted to do. But that wasn't really now in the sense that, for instance, Mingus' compositions, though from a different era, have always been free. Duke's were like that. Duke used whatever he felt that he should use to express whatever ideas he had, so that was really nothing new. It was just a different way of expressing the same thing. You see, there are no limits to music, to anything. The only limitation is your own mind. If you say, "Well, this is what I want to do," then stop there, that's as far as it's gonna go. But somebody else is gonna say, "No, I can take it a little bit farther than that." Everything builds, one on top of the other, you know. It's like a stack, one up. You just stop whenever you go as high as you want to go. That's the end of it. There's one area of music that if you do get into is very dangerous for your life, but I don't want to get into that. I really don't know much about it.

V.F.: In what ways do you feel your own music has evolved over the years?

D.P.: It's difficult for me to discuss my own music because I've never really satisfied myself. I know that I have done some good things. I think the solo album I did for Sackville is good. I like that more than anything else I've done. But now I don't even like that. I can't say because I'm continually growing. What I played five minutes ago, I won't like the next five.

V.F.: Do you prefer to play solo or with a group?

D.P.: At this point, I enjoy both. When I come out with a group, I do parts of a performance solo and parts of it with the group. I play differently with a group than I do solo. Solo gives me a different kind of freedom of expression than with a group. For example, Song Played Backwards. I started at the end and played it backwards.

V.F.: What was the song?

D.P.: I didn't have a title for it. I played it by myself, you know, so I just...played it backwards. (Laughs.) There are different ways of doing things. I just felt like doing it, so I did it. When I solo, it's only my mind. You can do anything you want to do with a group, you know. Like I said, you set your own limitations. When I play with a group, I have another kind of freedom of expression because I have the other minds, the other vibrations of the musicians working, you see. There's interplay. You have to consider them and they have to consider you. So a group adds another aspect to the music. I enjoy both, you know, and it doesn't matter to me if I play solo or with somebody else.

V.F.: Have you performed any of your solo pieces in a group setting?

D.P.: No, I haven't. Some of them are not adaptable to groups. At least, I haven't figured out a way to do it. I imagine I can. Some I just like to play solo. Richard's Tune is one of my favorites. It's adaptable to group or trio or whatever, but I prefer to play it solo. The Malcolm piece is part of a suite which has seven or eight different...tunes, I guess you'd call them. The only one that I can play solo is the one I recorded, Malcolm, Memories and Gunshots. That's the only one that's adaptable to piano. The rest of it is integrated into the full wide spectrum - small group, strings, full orchestra.

V.F.: Then you've written for large ensembles, also?

D.P.: Yeah, I used to be Arranger and Conductor for King Records a few years back. That was also in the sixties. Not jazz things, but for singers: Arthur Prysock, Irene Reid.

V.F.: In recent years, jazz musicians have recorded solo piano albums more frequently than they have in the past. Why do you think this is happening?

D.P.: I really don't know, but it's nothing new. Tatum did it. Monk has done it. Duke. On one cut I remember, Eric Dolphy played solo saxophone - God Bless The Child, I believe. Solo isn't really new, you know. My cousin, who was a big influence on my playing - Clyde "Fats" Wright used to tell me that unless you could play solo, you couldn't play at all. I think every piano player has to. If you sit home and practise, you develop a way of playing solo, anyway. I think more people are becoming aware of the beauty of just piano alone. Classical music, you know, has solo concerts, so it's not strange for jazz to do the same thing. It's always been there.

V.F.: Do you think the increase in solo piano recordings could be, in part, a reaction to the increased use of electronic keyboard instruments?