SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING, 2019

VOLUME SEVEN NUMBER ONE

WADADA LEO SMITH

Featuring the Musics and aesthetic Visions of:

CINDY BLACKMAN

(March 23-29)

RUTH BROWN

(March 30-April 5)

JOHN LEWIS

(April 6-12)

JULIUS EASTMAN

(April 13-19)

PUBLIC ENEMY

(April 20-26)

WALLACE RONEY

(April 27-May 3)

MODERN JAZZ QUARTET

(May 4-10)

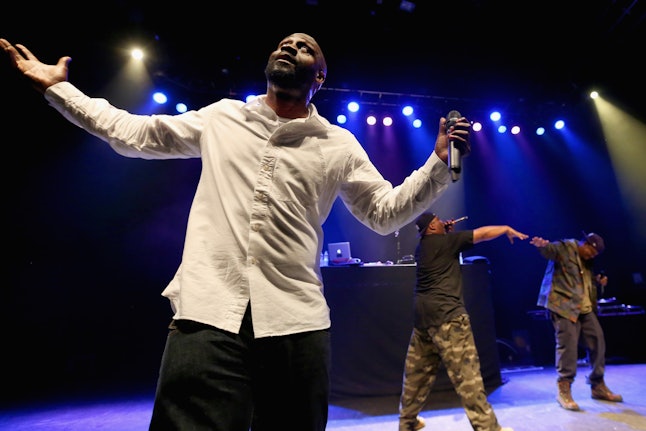

DE LA SOUL

(May 11-17)

KATHLEEN BATTLE

(May 18-24)

JULIA PERRY

(May 25-31)

HALE SMITH

(June 1-7)

BIG BOY CRUDUP

(June 9-15)https://www.allmusic.com/artist/de-la-soul-mn0000238322/biography

De La Soul

(1987-Present)

Artist Biography by Stephen Thomas Erlewine

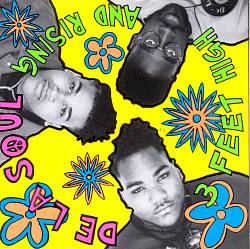

At the time of its 1989 release, De La Soul's debut album, 3 Feet High and Rising,

was hailed as the future of hip-hop. With its colorful, neo-psychedelic

collage of samples and styles, plus the Long Island trio's low-key,

clever rhymes and goofy humor, the album sounded like nothing else in

hip-hop. Where most of their contemporaries drew directly from

old-school rap, funk, or Public Enemy's dense sonic barrage, De La Soul

were gentler and more eclectic, taking in not only funk and soul, but

also pop, jazz, reggae, and psychedelia. Though their style initially

earned both critical raves and strong sales, De La Soul

found it hard to sustain their commercial momentum in the '90s as their

alternative rap was sidetracked by the popularity of considerably

harder-edged gangsta rap.

De La Soul formed while the trio members -- Posdnuos (born Kelvin Mercer, August 17, 1969), Trugoy the Dove (born David Jude Jolicoeur, September 21, 1968), and Pasemaster Mase (born Vincent Lamont Mason, Jr., March 27, 1970) -- were attending high school in the late '80s. The stage names of all of the members derived from in-jokes: Posdnuos was an inversion of Mercer's DJ name, Sound-Sop; Trugoy was an inversion of Jolicoeur's favorite food, yogurt. De La Soul's demo tape, Plug Tunin', came to the attention of Prince Paul, the leader and producer of the New York rap outfit Stetsasonic. Prince Paul played the tape to several colleagues and helped the trio land a contract with Tommy Boy Records.

Prince Paul produced De La Soul's debut album, 3 Feet High and Rising,

which was released in the spring of 1989. Several critics and observers

labeled the group as a neo-hippie band because the record praised peace

and love as well as proclaiming the dawning of "the D.A.I.S.Y. age" (Da

Inner Sound, Y'all). Though the trio was uncomfortable with the hippie

label, there was no denying that the humor and eclecticism presented an

alternative to the hardcore rap that dominated hip-hop. De La Soul were quickly perceived as the leaders of a contingent of New York-based alternative rappers that also included A Tribe Called Quest, Queen Latifah, the Jungle Brothers, and Monie Love; all of these artists dubbed themselves the Native Tongues posse.

For a while, it looked as if De La Soul and the Native Tongues

posse would eclipse hardcore hip-hop in terms of popularity. "Me,

Myself and I" became a Top 40 pop hit in the U.S. (number one R&B),

while the album reached number 24 (number one R&B) and went gold. At

the end of the year, 3 Feet High and Rising

topped many best-of-the-year lists, including the Village Voice's. With

all of the acclaim came some unwanted attention, most notably in the

form of a lawsuit by the Turtles. De La Soul had sampled the Turtles' "You Showed Me" and layered it with a French lesson on a track on 3 Feet High

called "Transmitting Live from Mars," without getting the permission of

the '60s pop group. The Turtles won the case, and the decision not only

had a substantial impact on De La Soul,

but on rap in general. Following the suit, all samples had to be

legally cleared before an album could be released. Not only did this

have the end result of rap reverting back to instrumentation, thereby

altering how the artists worked, it also meant that several albums in

the pipeline had to be delayed in order for samples to clear. One of

those was De La Soul's second album, De La Soul Is Dead.

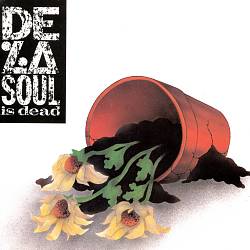

When De La Soul Is Dead

was finally released in the spring of 1991, it received decidedly mixed

reviews, and its darker, more introspective tone didn't attract as big

an audience as its lighter predecessor. The album peaked at number 26

pop on the U.S. charts, number 24 R&B, and spawned only one minor

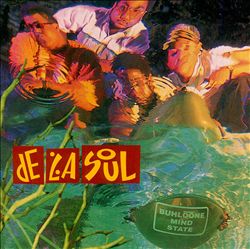

hit, the number 22 R&B single "Ring Ring Ring (Ha Ha Hey)." De La Soul worked hard on their third album, finally releasing the record in late 1993. The result, entitled Buhloone Mindstate,

was harder and funkier than either of its predecessors, yet it didn't

succumb to gangsta rap. Though it received strong reviews, the album

quickly fell off the charts after peaking at number 40, and only

"Breakadawn" broke the R&B Top 40. The same fate greeted the trio's

fourth album, Stakes Is High.

Released in the summer of 1996, the record was well reviewed, yet it

didn't find a large audience and quickly disappeared from the charts.

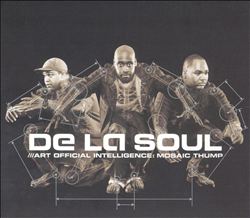

Four years later, De La Soul initiated what promised to be a three-album series with the release of Art Official Intelligence: Mosaic Thump; though reviews were mixed, it was greeted warmly by record buyers, debuting in the Top Ten. The second title in the series, AOI: Bionix, even featured a video hit with "Baby Phat," but Tommy Boy and the trio decided to end their relationship soon after. De La Soul subsequently signed their AOI label to Sanctuary Urban (run by Beyoncé's father, Mathew Knowles) and released The Grind Date in October 2004. Two years later the group issued Impossible Mission: TV Series, Pt. 1, a collection of new and previously unreleased material.

The group then went on hiatus with only the splinter release De La Soul's Plug 1 & Plug 2 Presents...First Serve

released in 2012. A year later, the group created a free download of

all their early albums and packaged the set as You're Welcome, though it

wasn't available for long thanks to the legal efforts of their former

label, Warner Bros. A crowd-funding campaign for a new album was

launched in 2015, and after successful funding, the LP And the Anonymous Nobody

was self-released in August of 2016. The nearly sample-free album

featured the trio's live band and assorted friends playing live

instruments, along with a guest list that included Usher, David Byrne, 2 Chainz, and Damon Albarn, among many others.

“Make Those Records You Make”: Prince Paul Recalls the Making of ‘De La Soul is Dead’

In the summer of 2008 The Smoking Section let me write an extensive oral history of De La Soul’s first four albums. The two-part piece included interviews with authors Ethan Brown and Brian Coleman, V103 DJ and Scratch Atlanta instructor DJ Jaycee, graphic designer and mixtape DJ Scott Williams, and Prince Paul. Jaycee even made an unbelievable De La Soul mixtape

to help promote the article. It was one of the most fun collaborative

efforts I have ever been a part of. Writing the article cemented my love

of all things De La and Prince Paul. It also made me an even more

obsessive student of their work.

On May 13th, 2016, De La Soul is Dead will turn 25 years old. After my Smoking Section

piece I aspired to write a oral history about the making of, reception,

and legacy of the album to coincide with the anniversary. I love 99% of

De La Soul’s output, but for me, De La Soul is Dead

is their Mount Rushmore and my favorite album of all time. During my

various attempts to write the book 7L, 88-Keys, DJ Neil Armstrong, and

Prince Paul were all kind enough to do extensive interviews with me.

While they provided me with some great material, a book would require

many more interviews with artists and admirers of the album.

2016

is here. The anniversary is staring me in the face and there is no way I

will write a worthwhile book about the album in time. That said,

writing a book about the album is still a dream of mine and something I

hope to accomplish. In the meantime I’ve decided to share a snippet of

my interview with Prince Paul where he breaks down the equipment and

creative process that was used to make De La Soul Is Dead.

If nothing else, I hope this interview sparks conversation about De La Soul Is Dead and gives people an inside look at what it was like produce sample-based music during the early 90s.

“Now you could probably throw it in the computer and slap it together in two minutes. But at the time we thought we were ahead of the curve in technology.”

Gino: Everyone I interview about De La Soul is Dead mentions how

the production stands out, especially for the time. Given the equipment

you guys were using, it’s crazy that the beats are so layered and all

of the samples are perfectly on beat and in key.

Prince Paul: We had the experience of making the first album to give us a better idea of how to do it on the second album with the equipment we had. It’s funny, at the time that equipment was considered kind of new. Making records before those samplers was hard. On De La Soul is Dead, we were like, “Wow, we can lock things up, we have delays, we can move samples around, and we have pitch shifters.” Now you could probably throw it in the computer and slap it together in two minutes. But at the time we thought we were ahead of the curve in technology.

Prince Paul: We had the experience of making the first album to give us a better idea of how to do it on the second album with the equipment we had. It’s funny, at the time that equipment was considered kind of new. Making records before those samplers was hard. On De La Soul is Dead, we were like, “Wow, we can lock things up, we have delays, we can move samples around, and we have pitch shifters.” Now you could probably throw it in the computer and slap it together in two minutes. But at the time we thought we were ahead of the curve in technology.

Gino:

I know in talking to you for an earlier interview that you guys were

using an Akai S-900, an Emu SP-12, and a Casio SK-5 on 3 Feet High and Rising. Did you use the same equipment for De La Soul is Dead?

Prince Paul: Yeah, we used all of the same stuff. We were at the same studio, Calliope. I think we mixed the album at Island Media in New York. We basically used the same format.

Prince Paul: Yeah, we used all of the same stuff. We were at the same studio, Calliope. I think we mixed the album at Island Media in New York. We basically used the same format.

Gino: Can you explain the difference between an SP-12 and SP-1200?

Prince Paul:

The SP-12 doesn’t have a disk drive so you can’t save the samples. The

1200 has a floppy disk drive that you can save your music in. So we had

an early one, the very first one.

Gino:

I’m amazed that you guys were utilizing an SK-5. I know that’s a very

limited sampler. Did you just use the external mic device to sample?

Prince Paul: I honestly don’t remember. I still have that sampler, but it’s in my attic. I think there was a mic input and it also had mic built in on top of it that you could speak into. I think we just plugged into the mic input and sped samples up. Obviously the sound was kind of jacked up, but nobody was concerned about quality back then. We were just impressed by the novelty of sampling. Everyone was like, “Ooh, I can take a piece of something and play it on a keyboard.”

Prince Paul: I honestly don’t remember. I still have that sampler, but it’s in my attic. I think there was a mic input and it also had mic built in on top of it that you could speak into. I think we just plugged into the mic input and sped samples up. Obviously the sound was kind of jacked up, but nobody was concerned about quality back then. We were just impressed by the novelty of sampling. Everyone was like, “Ooh, I can take a piece of something and play it on a keyboard.”

“Obviously the sound was kind of jacked up, but nobody was concerned about quality back then. We were just impressed by the novelty of sampling.”

Gino: Did you have a favorite sampler that you were using at the time?

Prince Paul: Probably the S-900. I could navigate that pretty easily. I broke it out recently because I have a couple in racks in my basement. I plugged them in and played some old samples through them. Even though it’s big and bulky, nothing sounds like that. It’s pretty flexible, it’s easy to work, and it’s easy to truncate your sample and get things tight. You can trigger certain sounds with different keys on the drum machine.

Prince Paul: Probably the S-900. I could navigate that pretty easily. I broke it out recently because I have a couple in racks in my basement. I plugged them in and played some old samples through them. Even though it’s big and bulky, nothing sounds like that. It’s pretty flexible, it’s easy to work, and it’s easy to truncate your sample and get things tight. You can trigger certain sounds with different keys on the drum machine.

When

you look at all this new technology, everything sounds very sterile.

Everything is clean and super quiet. It kind of lacks something. When I

plug that in, it’s like, “Wow, this is hip hop.” It makes a big

difference…a way bigger difference than having an MPC or something. It

has its own character. Certain pieces of equipment make you program a

certain way because you are limited. That’s the beauty of those

machines.

“Certain pieces of equipment make you program a certain way because you are limited. That’s the beauty of those machines.”

Gino: I’m curious how Tommy Boy responded to the album. 3 Feet High and Rising was so successful, was there an outcry when you submitted De La Soul is Dead? I would assume some people were worried about how dark and different it was.

Prince Paul: They were pretty supportive, basically because we were tried and tested. The success of 3 Feet High came as a surprise to everyone. After it came out, we were able to come in and tell them what we wanted and how we wanted it done because we were so ahead of the curve on everything. They couldn’t figure out our thinking, our sensibilities, or how we created. They were like, “You tell us what to do”, which was nice. It was nice to have a little more control over your projects. A little more respect, I should say.

Prince Paul: They were pretty supportive, basically because we were tried and tested. The success of 3 Feet High came as a surprise to everyone. After it came out, we were able to come in and tell them what we wanted and how we wanted it done because we were so ahead of the curve on everything. They couldn’t figure out our thinking, our sensibilities, or how we created. They were like, “You tell us what to do”, which was nice. It was nice to have a little more control over your projects. A little more respect, I should say.

Gino:

The way you were getting financially compensated by Tommy Boy might not

have been ideal, but it is cool that you were given that level of

creative freedom.

Prince Paul: On the first album, there were concerns. They had Dante come in and more or less be their eyes and ears so that he could report back to them. On the second album they said, “You guys know what you’re doing. We trust you. Make those records you make.” It was cool. I think their main concern for the second record was keeping track of the samples because they had messed up the first one so bad with clearing them.

Prince Paul: On the first album, there were concerns. They had Dante come in and more or less be their eyes and ears so that he could report back to them. On the second album they said, “You guys know what you’re doing. We trust you. Make those records you make.” It was cool. I think their main concern for the second record was keeping track of the samples because they had messed up the first one so bad with clearing them.

“The success of 3 Feet High came as a surprise to everyone. After it came out, we were able to come in and tell them what we wanted and how we wanted it done.

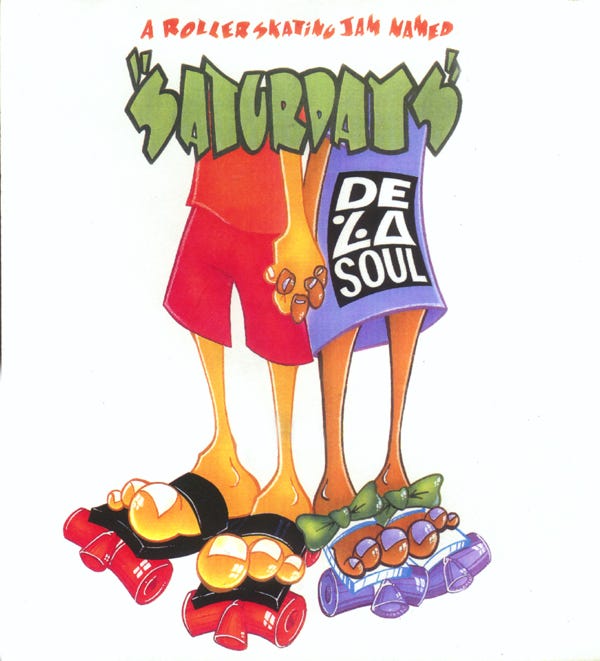

Gino: That seems to always get overlooked when people discuss this album. De La Soul is Dead

was made after a sample lawsuit against you guys that was pretty

historic…and it’s so sample heavy. When I look at the sample list for “A

Roller Skating Jam Named ‘Saturdays’”, you have seven or eight samples

that make up that beat. For a label to clear that many samples seems

unfathomable by today’s standards.

Prince Paul: It’s just how we made records in those days, so it didn’t seem uncommon. Once Tommy Boy became so concerned with making sure every little sound was cleared, it made it a little different than the first album. The first album, when it came to sampling, they were like “Eh, whatever, you guys probably won’t sell that much anyway.” But when it was all eyes on De La they were keeping track of every sound we used. Even with stuff that wasn’t sampled. They were really anal about a whole lot of sample stuff, which is understandable. But having the lawsuit wasn’t our fault to begin with. We were like, “You created this problem. We’ll always give you all of the sample information, that’s without a doubt. How you guys retain the information and what you do with it is up to you.”

Prince Paul: It’s just how we made records in those days, so it didn’t seem uncommon. Once Tommy Boy became so concerned with making sure every little sound was cleared, it made it a little different than the first album. The first album, when it came to sampling, they were like “Eh, whatever, you guys probably won’t sell that much anyway.” But when it was all eyes on De La they were keeping track of every sound we used. Even with stuff that wasn’t sampled. They were really anal about a whole lot of sample stuff, which is understandable. But having the lawsuit wasn’t our fault to begin with. We were like, “You created this problem. We’ll always give you all of the sample information, that’s without a doubt. How you guys retain the information and what you do with it is up to you.”

“The first album, when it came to sampling, they were like “Eh, whatever, you guys probably won’t sell that much anyway.” But when it was all eyes on De La they were keeping track of every sound we used.”

Gino:

The composition of the samples is incredible. I’m curious if any of the

beats stand out as being particularly difficult to compose. For

instance, on “A Roller Skating Jam Named ‘Saturdays’”, you have the baby

scratching, the drums, the “and roller skates” vocal, and then the main

loop comes in. And I’m only breaking down the beginning of the song.

How difficult was it to get all of that to sound right?

Prince Paul: It’s all about the arrangement. Pos came up with the main loop and a lot of the other ideas for that song. I showed De La a lot about how to navigate through the equipment and how to make everything layer properly. The key to making it work isn’t necessarily how much you layer, it’s how you arrange the samples. You have to put samples in key so everything sounds like it belongs. How you EQ everything…there’s a science to it.

Prince Paul: It’s all about the arrangement. Pos came up with the main loop and a lot of the other ideas for that song. I showed De La a lot about how to navigate through the equipment and how to make everything layer properly. The key to making it work isn’t necessarily how much you layer, it’s how you arrange the samples. You have to put samples in key so everything sounds like it belongs. How you EQ everything…there’s a science to it.

Early

Public Enemy production used layers upon layers and layers, and their

arrangements were always super duper incredible to me. We were kind of

like students to what they did. To me, our production didn’t even come

close to what they were doing…almost like a fake version of how well

they sampled and meshed stuff together. (Laughs) It makes it easier when

you have a blueprint of what to do or how to make something sound. When

I listened to Public Enemy, my guidelines were for us to always be high

quality. To me, what I was making wasn’t quite at their level, but it

was good enough. (Laughs)

“Early Public Enemy production used layers upon layers and layers, and their arrangements were always super duper incredible to me. We were kind of like students to what they did.

Gino:

Today’s equipment makes it easy for people to arrange samples so that

everything sounds in key. With the equipment you were using, I would

think that you either had some musical training or you just had an

incredibly good ear for hearing what went well together.

Prince Paul: A lot of the engineers that we used were also musicians. We wouldn’t always go by what they would say, ‘cause engineers will make you do some real stupid stuff, but it’s always good to get another opinion. And a lot of it was us just listening. If we cringed at something, we’d say, “That’s wrong” and adjust it until it sounded right. There might be things you try to put together that don’t mesh well, so you know not to put them at the same time during the song.

The bulk of it is feel and the other part is common sense. It’s like putting clothes together. You’ll say, “Oh my god, I love this hat, this jacket, and these pants”, but they might not all go together. You have to rock them in different ways with different shoes, shirts, and whatever else. Even though in your gut you want to rock them all together, you have to get that out your mind. Same thing with music. Everything has to fit right; you can’t force things together just because you like them.

Prince Paul: A lot of the engineers that we used were also musicians. We wouldn’t always go by what they would say, ‘cause engineers will make you do some real stupid stuff, but it’s always good to get another opinion. And a lot of it was us just listening. If we cringed at something, we’d say, “That’s wrong” and adjust it until it sounded right. There might be things you try to put together that don’t mesh well, so you know not to put them at the same time during the song.

The bulk of it is feel and the other part is common sense. It’s like putting clothes together. You’ll say, “Oh my god, I love this hat, this jacket, and these pants”, but they might not all go together. You have to rock them in different ways with different shoes, shirts, and whatever else. Even though in your gut you want to rock them all together, you have to get that out your mind. Same thing with music. Everything has to fit right; you can’t force things together just because you like them.

Obscure Records, Mistakes, and Mixing By Hand: Prince Paul Reconstructs the Making of 3 Feet High…

This is a modified and updated version of an article that first appeared on The Smoking Section in August of 2008. Many…medium.com

This is a modified and updated version of an article that first appeared on The Smoking Section in August of 2008. Many…medium.com

I am a director of academic support/special education teacher who loves to write about books, music, records, and samplers. I also love interviewing people about these things. If you enjoyed this piece, please consider sharing it on Facebook, Twitter, and recommending it on Medium.

You can also check out my Bookshelf Beats publication.

De La Soul’s Legacy Is Trapped in Digital Limbo

On Valentine’s Day in 2014, De La Soul did something surprising: The group gave away almost all of its work.

After

gathering fans’ email addresses in an online call-out, this hip-hop

trio from Long Island sent out links to zip files for its first six

albums. Those albums — including its 1989 debut, “3 Feet High and

Rising,” a platinum record in the Library of Congress’s National

Recording Registry — are some of the genre’s most influential and

sonically adventurous, threading samples from obscure, kitschy records

alongside recognizable pop, jazz and funk hooks.

The

links were available for a day, and the group says the response

overloaded the servers hosting the music files. They also attracted the

attention of Warner Music, which has owned those records since 2002,

when it acquired the catalog of Tommy Boy Records, a pioneering indie

hip-hop label.

The attention wasn’t

just because the group was giving its catalog away. It was because those

six albums have never been available to buy digitally or to stream.

In a recent interview, the group explained that it had reached a boiling point.

“We

were frustrated with people not being able to just get it,” Vincent

Mason, 46, the group’s D.J., known as Maseo, said, adding that the

financial impact of digital invisibility was amplified by the fact that

their work with Damon Albarn’s Gorillaz had introduced them to another

audience.

Warner

Music Group, which controls the albums’ distribution, was quick to

reach out. “They did tap on our window,” said David Jolicoeur, 47,

formerly known as Trugoy the Dove (now just Dave), rapping his knuckles

on a table for emphasis. “‘Hey guys, what the [expletive] are you

doing?’”

“We spent years and years

trying to figure this out with Warner,” said Kelvin Mercer, 46, known as

Posdnuos, who added that label personnel kept shifting and allies were

“shuffled out” over time.

But in

gathering a list of dedicated fans, De La Soul may have laid the

foundation for its new record. “And the Anonymous Nobody,” out Aug. 26,

is a largely sample-free affair financed by a Kickstarter campaign that accumulated over $600,000 — more than a third of which was raised in eight hours, the group members say.

Mr.

Mason said they considered how much money they would earn from a record

label and decided owning the album was worth more. “The faith, I would

say, really kicked in when we gave away the music.”

“And

the Anonymous Nobody” is a drastic departure for the group. Rather than

use samples, De La Soul spent three years recording more than 200 hours

of the Rhythm Roots Allstars, a 10-piece funk and soul band it has

toured with. Then the group mined that material for the basis of the 17

tracks (25 musicians ended up playing on the album). From the opening

horn fanfare of “Royalty Capes” to the Queen-esque metal of “Lord

Intended” to the loping cowboy funk of “Unfold” (an exclusive track for

those who contributed to the Kickstarter campaign), the record explores a

number of genres, with extended instrumental passages. And a wild

variety of guests — Usher, Snoop Dogg, David Byrne, Little Dragon — help

shift the moods. The proposed guest list was even more ambitious — Tom

Waits, Jack Black and Axl Rose were also approached. “Willie Nelson

kindly declined,” Mr. Jolicoeur said.

The

album’s title, Mr. Jolicoeur said, represented part of the

collaborative process. “This is about a person selflessly giving

everything they could to make something cool or new or fun or better

happen,” he said. “That became the vibe of the record. It wasn’t really

about a concept of the song; it was about, out of nowhere: ‘I play

trumpet. I want to contribute.’”

Mr.

Jolicoeur said he had learned that a similar, freewheeling approach

often led to the kinds of sounds the group had sampled in the past.

“When these guys from the Ohio Players to Parliament-Funkadelic were

just jamming, that’s where the songs came from,” Mr. Jolicoeur said. “It

was allowing something to happen organically.”

In

its third decade as a group, De La Soul is in a special position. Along

with the Bomb Squad’s collaborations with Public Enemy and the Dust

Brothers’ production for the Beastie Boys, its work with the producer

Prince Paul resulted in some of hip-hop’s pioneering sounds,

establishing the melodic and harmonic possibilities of sampling. Now the

group is re-emerging with new music after 12 years, during which the

genre has gone through sonic and aesthetic revolutions: Hip-hop has

become a top-performing genre on streaming music sites,

and the internet has helped coronate a new crop of blockbuster rappers.

But with the exception of “The Grind Date,” released through BMG in

2004, De La Soul has not been able to earn anything off its catalog from

digital services.

“We’re

in the Library of Congress, but we’re not on iTunes,” Mr. Mercer said,

adding that when the group interacts with fans in person or online, they

always ask the same question: “Yo, where’s the old stuff?”

That

old stuff — which also includes “De La Soul Is Dead” (1991), “Buhloone

Mindstate” (1993) and “Stakes Is High” (1996) — may be fraught with

problems, according to people familiar with the group’s recording and

publishing history. In 1989, obtaining the permission of musical

copyright holders for the use of their intellectual property was often

an afterthought. There was little precedent for young artists’ mining

their parents’ record collections for source material and little

regulation or guidelines for that process.

Deborah

Mannis-Gardner, a sample-clearance agent who worked with De La Soul on

its new record, said that lack of guidelines could be why Warner Music

is keeping the catalog in digital limbo.

“My

understanding is that due to allegedly uncleared samples, Warners has

been uncomfortable or unwilling to license a lot of the De La Soul

stuff,” Ms. Mannis-Gardner said. “It becomes difficult opening these

cans of worms — were things possibly cleared with a handshake?”

An

added possible complication lies in the language of the agreements

drafted for the use of all those samples. (There are more than 60 on “3

Feet High and Rising” alone — the group was sued by the Turtles in 1991

for the use of their song “You Showed Me” on a skit on that album and

settled out of court for a reported $1.7 million.) If those agreements,

written nearly three decades ago, do not account for formats other than

CDs, vinyl LPs and cassettes, Warner Music would have to renegotiate

terms for every sample on the group’s first four records with their

respective copyright holders to make those available digitally.

In

a statement, a person speaking for Rhino, a subsidiary of Warner Music

Group that deals with the label’s back catalog, said: “De La Soul is one

of hip-hop’s seminal acts, and we’d love for their music to reach

audiences on digital platforms around the world, but we don’t believe it

is possible to clear all of the samples for digital use, and we

wouldn’t want to release the albums other than in their complete,

original forms. We understand this is very frustrating for the artists

and the fans; it is frustrating for us, too.”

A

number of people interviewed say the legal phrase “now known or

hereafter discovered” may determine De La Soul’s digital future. It

ensures that samples cleared in the past are legal for use on streaming

services and for digital music retailers.

De La Soul in 1993. From left: David Jolicoeur, Vincent Mason and Kelvin Mercer.CreditDavid Corio/Michael Ochs Archives, via Getty Images

Michelle

Bayer, who handles De La Soul’s publishing administration, said that

phrase’s potential absence on the group’s contracts for samples could

complicate matters for Warner Music. (Warner Music would not provide

details about the sample contracts.)

“It’s

tricky because someone could deny the sample use now, or negotiate high

upfront advances, maybe even higher percentage or royalty than was

originally negotiated, which lessens what the label can earn,” she said.

“Before, people were like, ‘Oh yeah, whatever you want to do, we don’t

even know what you’re talking about, sampling, who cares, whatever.’

Now, it’s like, ‘Wow, that’s a big piece of real estate.’”

Ms. Bayer added that people are still filing copyright claims on samples from De La Soul’s early records.

“Two

songs from the first album just came up that had never come up before,”

Ms. Bayer said. “I think when Warner got the catalog, I think people

started making claims, people were kind of coming out of the woodwork

going, ‘Oh, well now it’s a major label involved, and we can possibly

get more from them than we might have gotten from an independent label

like Tommy Boy.’”

But others,

including Paul Huston, the producer known as Prince Paul, who worked

closely with the group on its first three albums, say they did their due

diligence. “Sampling was obviously new, but we were told, ‘Hey, here’s

some sample-clearance forms — you have to fill these out,’” Mr. Huston

said, adding that Tommy Boy became much more careful after the success

of “3 Feet High and Rising.” “It got to the point where it was like,

‘What is that scratch!?’”

“Stakes Is High” (1996)

“Stakes Is High” (1996)

Tom

Silverman, the founder of Tommy Boy Records — which also put out albums

by Digital Underground and Queen Latifah — said that making the group’s

catalog available digitally would not be difficult, considering that

Warner Music should know the copyright holders who have been receiving

royalties for the physical sales of the records.

Mr.

Silverman said: “Cutting a deal, you would think, to give them more

money, shouldn’t be that hard, especially if you’re fair and logical and

say, ‘Let me pay you the same percentage that we’ve always paid you on

physical on digital, too, so you can make that much money.’ So it

doesn’t really make a lot of sense that they’ve haven’t even tried.”

For

De La Soul, Warner Music and the owners of the copyrighted samples, the

catalog’s absence from digital media can be felt in an absence of

income. That money would have come from downloads (the iTunes Music

Store opened in 2003); streaming; ringtones (Mr. Silverman points out

the group’s 1991 single “Ring Ring (Ha Ha Hey)” as a potential ringtone

windfall); and deals with television, movies and advertisers.

The cultural loss, said Ahmir Thompson, the Roots drummer known as Questlove, is just as significant.

“Unless

Warner’s illustrious history is so disposable that they can let one or

two classics just fall by the wayside,” Mr. Thompson said, “and live in

this sort of storied folklore — I mean, ‘3 Feet High and Rising’ is very

much in danger of being the classic tree that fell in the forest that

was once given high praise and now is just a stump.”

“Buhloone Mindstate” (1993)

Lonnie

Lynn, the rapper known as Common who has appeared on De La Soul albums,

said the lack of a digital presence is a blow to available hip-hop

history. “It’s obviously disappointing, because I feel like De La is

timeless music, and I feel like there’s a 16-year-old that would find De

La and be like, ‘Aw, man, that’s cool.’”

The

group says it volunteered to bear the administrative burden of making

the catalog available but that Warner Music was not interested.

Mr.

Jolicoeur acknowledges the potential task Warner faces is “a lot of

work,” but Mr. Mason argues the time to do that work is now. “When I try

my best to tap into the psyche of record execs and how they think, they

know there’s some value — that’s why they’re not letting go,” he said.

“But on this side of the fence, you’re like, ‘I’d appreciate you don’t

wait until one of us die to do this.’ Can I enjoy some of the fruits of

my own labor, while I’m alive? Obviously, we’re in the music industry —

more people are more valuable dead than alive, you know? Can we change

that landscape?”

“It

really financially hurts these guys,” Ms. Mannis-Gardner said. “If

Warners won’t license it, perhaps they could sell it back to the band

members.”

Mr. Huston said that

several independent labels had approached him about releasing these

records but that interest fizzles when he directs them to Warner Music.

“It’s

like almost when you’re a kid and somebody says, ‘Hey, can I borrow

your bike?’” he said, laughing. “And it’s like, ‘I don’t know, my mom

won’t let me; you can ask my mom,’ and they go: ‘Ohhh, that’s all right.

I don’t need to borrow it.’”

Mr.

Silverman, who still runs Tommy Boy, hopes to obtain his label’s entire

back catalog from Warner Music, and making De La Soul’s disputed albums

available digitally is the first thing he said he would do. “They’ll be

making a lot more money when that stuff becomes available,” he said.

“Not the download part, the streaming part. It’s like they missed the

entire era of downloads.”

Given the success of its Kickstarter campaign, De La Soul hasn’t ruled out turning to crowdfunding to free its catalog.

“Maybe that’s what’s next,” Mr. Jolicoeur said. “This music has to be addressed and released. It has to. When? We’ll see. But somewhere it’s going to happen.”

A version of this article appears in print on , on Page AR14 of the New York edition with the headline: A Hip-Hop Legacy Stuck in Digital Limbo. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

Related Coverage:

Hip-Hop and R&B Fans Embrace Streaming Music Services

Steal This Hook? D.J. Skirts Copyright Law

De La Soul’s Kickstarter Campaign Raises $600,874

A Music Critic In 2016 Listens To De La Soul’s Classic 1989 Debut Album For The First Time

Why are the 3 Feet Rising, and what can we do to stop it?

6/3/2016

MTV News

This weekend, the beloved rap group De La Soul will be performing in New York City as part of the Governors Ball festival. The highly influential '90s act also just released "Pain," a new single featuring Snoop Dogg, in advance of their first album in over a decade, And the Anonymous Nobody. My colleagues tell me that "Pain" is "mad good" and "so dope" and, "Seriously, David, listen to this song." Now, all of that is cool and awesome, but personally I found it hard to form an opinion on "Pain," since I have never heard a complete De La Soul album. Nothing personal — I just never got around to it. To fix this problem, my editors kindly suggested — or, I guess, technically, told me, since I work for them — that I should spend today listening to De La Soul's classic Tommy Boy Records debut, 3 Feet High and Rising, and cataloguing my thoughts below. Please be warned: I talk a lot about yoga, bagels, and A Tribe Called Quest. Sorry!

0:45 — Game shows are chill, but I'm not sure how cool it is to make one the opening skit to a rap album. I’m not exactly clear on the setup of the show, and that’s making me nervous about how much I’m already missing about this album. I also just ate a bagel with cream cheese and my stomach feels weird.

3:46 — I’m growing increasingly stressed. No one’s announced their name, nor have there been any distinctive ad libs to tell these dudes apart. I know 1989 didn’t have emojis, but it would be nice if there was some marker of who's who — like if one had a real nasally voice or something? "The Magic Number" is fun, but it's also super-super-sample-based, which I know is real hip-hop, but feels so distant to what I enjoy about the genre in 2016. The stuff I like is all about instrumentals and ad libs that come closer to contemporary EDM than old-school rap.

6:15 — Holy shit, I regret eating this bagel.

9:10 — I’ve def heard "Can U Keep a Secret," and I don’t like it. I can be pretty hard to please with certain musical aesthetics, and rap music prior to ‘92 — the year I was born, of course — is something I’ve struggled with a lot in my life. Too often, going that far back can feel like a chore. Even classics from 2 Live Crew can sound too dated for me, and that’s just a drum machine and offensive lyrics, which in theory I should be all about.

16:26 - Not to stay fixated on the samples on the record, but I cannot get out of my head just how not rap this album sounds. Obviously there is a lot of rapping, and it’s pretty fine ("Ghetto Thang"), but all the samples and references give a real vibe of a sound collage. Maybe it’s the bagel I ate that is upsetting my stomach, but the duct-tape-and-glue nature of the album is distracting.

23:48 — Now we're in a skit where they just yell about taking different clothes, shoes, and hairstyles off, for some reason?

26:58 — There are so many more songs to go. :upside-down smiley face emoji:

35:00 — "Say No Go" is fun, I guess. I’m about halfway through with this album and I cannot wait for it to end. De La Soul is no Major Lazer.

Yesterday after yoga class, the teacher, who is new to the studio, asked if there was anything he might do to help with the class. I mentioned that the music was loud and could’ve been a bit softer. He replied back that it didn’t seem too loud to him, and that it was even soft compared to other classes. What I said back at that point was something that had been running through my head through the whole class — I spend all day sitting at a desk listening to music, and the last thing I want at the end of the day is to be stuck in a small room focusing on my breathing as more music blasts into my ears. This electric tour of 3 Feet High and Rising is offering a quick reminder of how much music I’ve never heard, and how much music I’ve just accepted that I probably won’t let into my life. I have a professional obligation to be familiar with music both new and old, so listening to De La Soul is worthwhile for sure. Still, forced music listening always places me in an awkward position, where I feel less like I'm engaging with an artist's creative work and more like I'm doing a homework assignment. I can complete the task, but isn't music also supposed to elicit an emotional response?

Meanwhile, back in De La World ...

38:42 — There is a bunch of yelling happening and, like, nah. I’m gonna listen to "Real Love" by Mary J. Blige for a little bit.

This song is one part house anthem and another part sad new jack swing. I cannot even pretend to think of a better combination of genres. The keyboard riff, the chunky drums and that hook are all so so so so sweet. But sadly I must return back to De La World.

39:16 — This album makes Views sound like a Ramones album. Jesus Christ, there is another skit.

41:46 — The bagel I ate earlier was a mistake. Also: Maybe it's strange that I’ve never really given much time to De La Soul, because I looooove A Tribe Called Quest, and I certainly hear a lot of them here. But Tribe songs are so much tighter. They don’t meander in the same way these tracks do ("Plug Tunin’ (Last Chance to Comprehend)"). "De La Orgee" was stupid in the way all rap sex skits are garbage, which is assuming that sex sounds and jokes are going to be funny in the middle of an album rather than best left on the recording room floor. Then again, I might just be a prude. Please let me know at @_davidturner_ on Twitter dot com.

45:50 — Q-Tip! Wow, his voice is so calming in this nonsense. "Buddy" is the first song that I can say I enjoy. It also sounds exactly like it could just be a lesser Tribe song. I made a vegan hot dog for lunch — just thought that y'all should know.

52:38 — "Me, Myself and I" is back to the bullshit of too many obvious samples, a thin hook, and accenting too many moments with little vocal effects that could be novel if they weren’t already used over the last 50 minutes of retreading the same ideas.

1:02:54 — Holy shit, the game show is still happening. The announcer says to mail the record label’s address, which is fucking insane, but kind of cool. Remember physical mail? Records? Postal addresses? Flesh? Corporeal bodies? Any of that stuff?

Perhaps I’ll give De La Soul another listen someday. I can feel the roots of music I should enjoy, but it just didn’t connect today. Right now, I’m gonna go listen to ATC’s eurodance classic "Around the World" and keep praying for the weekend.

De La Soul Talks the Group's Bold New Album and Legendary Past

by Tom Barnes

On Wednesday, Posdnuos, aka Kelvin Mercer, aka the group's Plug One, spoke with Mic about the group's new undertaking. He talked about how their creative process evolved over time and nodded to some of today's rappers he feels share that same perspective decades later.

Mic: Congratulations on your Kickstarter. One day. That's incredible. How much of that did you guys anticipate?

Pos: I mean, you know, you wanna be the person that's saying, "Hey, we're De La Soul, of course we did that." You say you wanna do it and you're gonna do it because you think positive. But I guess those butterflies in anticipation — you never know what's going to happen. And for that to happen in one day? In like nine hours or so? That was just amazing.

Mic: You mention in the Kickstarter video that you're doing this in response to the sampling lawsuits you went through. You guys were involved in those first few big lawsuits shaping the standards the industry has. The first was with the Turtles in 1991. What was that like for you?

Pos: It was definitely a shock in the negative sense. I just feel bygones is bygones, but we had handed in all that information to the correct people at Tommy Boy Records, which is what we were on at the time.

I believe that there was a crowd of people internally who loved the album. But since there wasn't a group before us that tested the waters, to show our label that what we were doing could be successful, we were pretty much the first of our kind. So I guess they didn't clear certain samples because they didn't think the album would sell. They looked at it like, "It's a skit on their album. Why clear the song with the Turtles?" And that's what happened.

We had their legal people reach out and place a suit upon us. The funny thing that I always tell people about this story is that in meeting their lawyer, he was a fan of our music. He even asked that — while handling the legal process — he wanted an autograph.

Pos: It was an organic response to years of people wanting our music and not being able to get it — seeing new listeners interested in learning about us because they found out or learned about us through a record or a feature with the Gorillaz. New fans were coming along like, "Hey man, love the song you did, but I've been trying to find your other stuff, because I hear so many great things about you. I could only see this random video on YouTube, etc." So it was a response like, "You know what? That would be an amazing statement on Valentine's Day to show our appreciation to the people who love us and give them our music." And that's what we did.

Mic: Was there any backlash? How did the label respond?

Pos: So far there hasn't been any major backlash. I'm sure that the label wasn't happy about it. But I would hope they did think, "Wow, look how many millions of people attached themselves to this situation because they love the music." And that maybe helped ignite a dollar-and-cents reading for them, like, "Hey man, we gotta take care of this situation, because we don't gotta be De La Soul fans to realize the money we could be making."

Pos: It was cool at first. But it isn't all of who we are. We purposefully named ourselves "De La Soul" because we came from the soul, and whatever we learned, that is where we were gonna be. That's why De La Soul Is Dead was completely different. People thought that was a bad move for our career, but that's also why I think we can still stand here. We continued to change as we grew up — as young boys becoming men — and that's what we wanted to do.

Mic: You, Q-Tip and Jay Z are the first class of hip-hop elder statesmen. How do you feel the genre is going to change as more of the original founders age and their perspectives on life and music change?

Pos: Something is dead if it isn't changing. It may not necessarily benefit you to where it's changing, but you have to respectfully understand that and not be upset about it. And I think some of the people you name alongside us — like A Tribe Called Quest — that's what they did: They continued to evolve. They weren't the same as the group as on their first album by their second album.

That's why I feel blessed, standing here now, to do this new album. [Fans] as well look to be a part of what's been missing in the music, which is a balance in the genre. A lot of what's going on is cool, but there's not a balance on each side. You don't have 80 Kendricks, amongst 80 Drakes, amongst 90 Young Thugs. There has to be a balance of music and you don't hear that.

https://hiphopdx.com/news/id.14674/title.de-la-souls-3-feet-high-and-rising-added-to-library-of-congress-national-recording-registry#

De La Soul's '3 Feet High And Rising' Added To Library Of Congress' National Recording Registry

April 7, 2011

The 25 albums were chosen by Librarian of Congress James H. Billington with the help of the Library’s National Recording Preservation Board. The records are chosen based on their cultural, aesthetical, or historical impact.

Other notable additions to the registry included Al Green’s Let’s Stay Together and New Orleans, blues artist Professor Longhair’s Tipitina album.

3 Feet High And Rising served as the debut album from De La Soul and remains one of Hip Hop’s most recognized albums. Released by Tommy Boy Records the album featured several well-known tracks including “Me Myself And I” and “Buddy.”

https://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/hip-hop/8500624/de-la-soul-interview-tommy-boy-jay-z-tidal

HIP-HOP

De La Soul on Tommy Boy Postponing Digital Release, Wanting Jay-Z to Bring Their Catalog to TIDAL: Exclusive

"It's a victory," Pos, of De La Soul, tells Billboard. "It's great that people who supported and understood what we mean to the culture, whether it's someone who's so dear and close to us like a Q-Tip, or someone who could admire the moves we've made creatively, but we ain't necessarily been in the room with each other nothing but maybe three times together, like a Jay-Z. You can have people just feel like, 'Culturally, I support and understand where they are coming from.'"

After the group members vocalized their displeasure with what they deemed "unbalanced, unjust terms" regarding Tommy Boy's proposed deal earlier this week, Jay-Z declared his allegiance to the trio by barring the catalog from release on his TIDAL streaming service.

"I spoke to [TIDAL's culture and content editorial director] Elliott [Wilson] and Elliott was like, 'Jay said, 'What y'all trying to do?,'" Maseo explains to Billboard. "I ain't gonna lie to you, I was torn because I would want them to win with the catalog, just based on where things is at for powerful black men. Jay could have been the one [to buy the catalog]. As far as the competitors and what people are making on streaming everyday, I would want him to be the one to succeed with the catalog and really go up against his competitors. He's TIDAL, dog. That's an amazing achievement, especially with where we come from and being a part of this culture. So, for it not to be on TIDAL, it speaks volumes."

Currently, De La Soul's catalog remains in the hands of Tommy Boy founder and CEO, Tom Silverman. Silverman signed the group during the late 1980s, and they then released their first two albums 3 Feet High and Rising and De La Soul Is Dead. Marred by sample clearance issues, the trio explained how they never benefited from the fruits of their labors, despite their projects seeing commercial success. "There's an asterik next to our name when it comes to sampling. We have been deemed copyright criminals," says Maseo.

After a bevy of stars, including Nas, Questlove and more, shared their support for De La, Silverman reached out to the group that signed with his label in the late '80s in an effort to reach a resolution. According to the group, little progress has been made.

"We've been bringing this to his attention," says Maseo. "He's been ignoring us for some time, it just got to the final hour where he expected to us to be on-board and make things smooth and dandy. When he finally addressed it, there were no changes in how he felt things needed to be. He used words like, 'what's customary" and 'what's standard.'"

He adds: "He can legally do what he wants, but the issues that I raised [was that] in all that you're doing with what you're able to do, did you clear it? Did you clear those samples? When he got the catalog back, is it cleared? What he said on the phone was, 'If anything comes up, we will deal with it the way we've dealt with it in the past.' And what I know that to be is that if a lawsuit comes up, we're gonna settle because we're in the wrong. I say we because we do suffer from that."

This year, De La Soul will be releasing their 10th album through Mass Appeal with production by DJ Premier and Pete Rock.

https://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/hip-hop/8500860/de-la-soul-interview-three-feet-and-rising-anniversary-tommy-boy-jay-z

HIP-HOP

De La Soul On '3 Feet High & Rising' 30th Anniversary, Working With DJ Premier, Ongoing Battle With Tommy Boy

It's a frigid Thursday night in New York City and the W Hotel serves as a refuge for one of hip-hop's most esteemed groups, De La Soul.

After a contentious week -- which included a verbal tussle with their

former label Tommy Boy over "unjust" contract terms regarding their back

catalog -- De La's Maseo and Pos plop themselves on the fifth-floor

studio couch to regain their strength.

What was supposed to be a celebratory week for the trio became a weary seven days consumed by drama. On Sunday (March 3), their 1989 debut album, 3 Feet High and Rising, reached its 30th anniversary. Equipped with sharp wordplay, diverse samples and lush production by Prince Paul, 3 Feet High and Rising became an instant classic and in 2010, was added to the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress. Along with platinum sales, the album's funky single "Me, Myself and I" rocketed to No. 1 on the Billboard R&B Charts three decades ago.

"3 Feet High and Rising was the first baby, and it gave birth to so many other things," Maseo tells Billboard. "I’m very appreciative and thankful for that — the ups and downs. I’m truly thankful for the opportunity, especially when you think back at those times and how life was just going in general with your dream being this, and mind you for us it was platooning. It led up to 3 Feet High and Rising, and we were pretty content with that."

Not only did 3 Feet High and Rising place the group in a rarefied space musically, it also paved the way for more diverse and much deeper sampling: for better and for worse. Months after the album went gold, lawyers for 1960s classic rock group The Turtles filed a lawsuit against De La for using the first four bars of their 1968 song “You Showed Me” on the song "Transmitting Live From Mars." Though Da La managed to settle with the band, going forward, their discography was thrown into digital limbo due to worries about simliar legal action over samples.

After Warner Music acquired the catalog of Tommy Boy Records in 2002, fans were unable to buy or stream the group’s first six albums due to uncleared samples. To remedy the situation, on Valentine’s Day 2014, De La offered fans an opportunity to download their first seven albums for free.

"That’s how bad we wanted it out there,” says Maseo. “We even went to Warner to get the thing up. You guys do it first. By them feeling there were too many infractures around it, and rightfully so, I get their point. This was a mess."

Now, Tommy Boy founder and CEO, Tom Silverman, is back in possession of De La's catalog and according to the group, allegedly offered them a 90/10 split of the profits if he were to take their music to streaming services. Outraged by the rumored imbalanced percentages, De La issued a boycott on social media, which caught the eyes of Nas, Questlove, and Jay-Z, among many others.

"We’ve always been very respectful," Pos explains. "There have been times in the past where we straight up had an issue with how Tommy Boy was doing things. We’ve never, even at a young age, have tried to physically harm anyone up at the office. We’ve never had people try to run up there and do anything. That has been an issue sometimes in our career where we’re the nice guys."

So far, the boycott has worked in their favor. Not only did Jay-Z offer to not post their catalog on his streaming service TIDAL, but Tommy Boy opted to not post their music on Friday (March 1) after the backlash they received on social media.

On the cusp of their 30th anniversary of 3 Feet High and Rising, Billboard spoke to De La Soul about their classic debut album, their favorite studio moments, their ongoing battle with Tommy Boy, Jay-Z's co-sign and more. Check out the interview below.

3 Feet High and Rising is 30 years old. Describe what that number means for you guys.

Maseo: 30 years and to still be here. 3 Feet High and Rising was the first baby and it gave birth to so many other things. I’m very appreciative and thankful for that. The ups and downs. I’m truly thankful for the opportunity, especially when you think back at those times and how life was just going in general with your dream being this, and mind you for us it was platooning. It led up to 3 Feet High and Rising and we were pretty content with that.

[Pos] was getting ready to head off to college, Dave was [heading to] architecture school, and I was getting ready to graduate and go to the military. But the opportunity kept coming back. Even with the idea of the second single, which was “Jenifa Taught Me” and “Potholes In My Lawn,” and doing the video behind that, we felt like we was in the game when it was on the radio with [DJ] Red Alert. That was good and that we could even have a relationship with Red, that was pretty much enough especially knowing what hip-hop was at that time. I was cool and content with how that transpired. The opportunity kept coming back all within that one and a half year span of when I was supposed to graduate and when I actually graduated. I wouldn’t change them times for nothing. It all led up to where we celebrate today and we can have this conversation.

Looking back, there’s a ton of classic records like “Jenifa” and “Me, Myself, and I.” What were some of your favorite studio sessions individually?

Pos: It’s hard to say, man. Any session while recording that album, it was truly a lot of fun. Like Mase was saying, we were really living our dream. The studio we were using to record that album was called Calliope Studios. It was a loft. It didn’t feel like a studio. Out the window you could see the Empire State Building. It felt like a home. It just was a real comfortable vibe and Prince Paul did a great job setting our mind up to just have fun. Outside of making sure we set up assignments of, “Today we’re going to work on this. Tomorrow, make sure you have some rhymes ready,” it was almost always spontaneity and having a good time. It was a great way to just walk up into the studio, so for me, it’s hard to pick a favorite day because they were all amazing.

Maseo: You never knew what was going to happen or who was going to show up. It would be moments where we’re working and Daddy O’s coming through or Keith Sweat is in the next room figuring out what he’s going to do. Milk and Giz. [MC] Lyte would come through.

Pos: She would come through on a day we’re doing a skit and she would wind up in the crowd yelling and doing something silly. The day Jungle came through, they just happen to come through on the day we were forming what would become “Buddy.” We didn’t plan for them to be one that record. That was just the day they came by and chilled. In the spirit of what Paul had placed in our minds, we were like, “Hey, you wanna get on this record?” If they had came the day before, they would have been on "Ghetto Thang.” It was just always a lot of fun.

Since you guys were 17-18 at the time, this all must have felt like a candy shop.

Maseo: A music candy shop. Definitely. Going from 4-track, to W cassettes, to playing with radio whites and putting samples up against speakers, to going to a 24-track studio, that was like, amazing. That was it.

Do you guys miss that? I know y’all have been in the studio with Pete Rock and DJ Premier, but do you miss that nostalgia?

Maseo: You could never recreate those innocent moments, but the reality of knowing you love to create, and you season that creating and now you get with others that have acquired as much success [feels beautiful.] I guess there’s somewhat of an innocence with marking a new territory with someone you admire. We couldn’t recreate those times because they were brand new.

Pos: We could always make new times.

Maseo: Absolutely, and that’s the beauty of always wanting to make music.

I heard you guys were in the studio with Premier the other night. How did that go?

Maseo: I always heard about Preme’s creative process. I’ve been in the studio with him, but after that process. This time, I got to see him directly in that process. Preme’s process reminds me of an old jazz musician. He gotta be in the moment. He’s not the one to sit in his own scientifical world and then send you a batch. It has to be a relationship, it has to be a conversation, it has to be an overall development and collaboration. We’d be in the room together and feeling the energy of us as people. Preme banged out another classic, in my opinion. We’re waiting to hear what gets laid to it lyrically, but the music speaks for itself.

Pos: It’s dope because he’s literally one of those artists who are literally encoding the true moment into what now he’s doing. Me talking, Mase in there laughing, and he’s sitting there in the corner. He sees I’m nodding my head so he keeps going. It was really dope. It was magical.

Though this month is the 30th anniversary of 3 Feet High and Rising, the word "bittersweet" has been floating around lately. Why bittersweet?

Pos: We’re blessed to still be here. We’re blessed to be able to be one of those groups where we’re celebrating the 30-year anniversary of an incredible piece of work and we’re a group that is actually still together. It’s not like we came back together and dusted off our hate for each other. We as a group have been together for more than 30 years and we have this piece of work that has been loved by the world.

Maseo: It shifted culture and it gave inspiration and gave a template for what a lot of other rappers were doing, especially the skits. I haven’t said this, they said this, the artists themselves. It’s in the library of Congress. It’s a part of American history. It’s one of the records that opened up a new business for lawyers in the world of sampling. It’s a historical piece. It has missed the relevant wave of the digital era. Moments and times where I look at people like Missy Elliott when she performed “Work It” maybe 15 years after it was out at a football game and it had a million plus downloads after she did that one performance. We have had more performances like that over the course of our career and we never had the opportunity to benefit from that media.

I actually want to jump into that. You guys made it known that in the download era, you weren’t able to thrive. Now that we’re in the streaming era with the new album coming, how do you guys look to prevent those previous missteps?

Maseo: Here’s the overall concern: due to the fact that it wasn’t able to come out then, how is it able to come out now and those infractures could still potentially come up? The samples and people coming out the woodworks. There’s someone who just came out recently. This is what continued to happen. We don’t know what Tommy Boy has cleared and not cleared and they’re looking to release this record recklessly on the administrative side, which would still be at a demise to us because based on how it’s been dealt with in the past, we paid 50 percent of whatever they choose to settle for.

I was listening to the Sway In the Morning interview and Mase, you said for the first three albums, y’all got “pennies” for royalties.

Maseo: Absolutely.

Pos: It was definitely a deal not in our favor. We’re young, we don’t know. The majority of this group, we didn’t have super hard lives growing up. Speaking for myself, coming from a middle class/working class household, if you have a label shoving $12,000 in front of myself at 17-18 year old kid...

Maseo: ... $13,000 advance.

Pos: There’s people who’d do one song for $13,000 and we did an entire album with 20 cuts. So you’re talking about, look, a bad deal that we accepted due to our lawyer saying this is the best it could be and we didn’t have a problem with it. But then I also say on our end, creatively where we were, we didn’t think to not put 12 songs on one record. We have a part to play in that, too.

Maseo: Being kids, though. Fuck all of that. We’re kids, man.

Would y’all blame youth and inexperience for taking such a bad deal at the time?

Maseo: We’re kids. People want to blame just like when you look at sports and they want to blame a player for losing their cool, but these are kids getting money. But let me take the line off that and put it back on this. We were kids, man. Someone was willing to invest in our dream. $13,000, or $2,000, at the end of the day, creatively, we’re allowed to do whatever the hell we want musically. What happens from what they do with it to when we’re making it, we don’t know this part.

Pos: We could turn around and be the ones who someone could say you’re sharing this little bit of seven drops of water Tommy Boy gave you to now have to come and split with the people you sampled. At least from the administrative aspect of this, we did share the information with Tommy Boy to clear this stuff. They chose not to clear it. At the time, there was no litmus test, there was no way to know if an album sounded like this, people don’t look like the average rappers that it was going to sell like this. There were people in front of us that were considered what hip-hop is and what was the standard that would sell records in the tri-state area.

This record not only attached itself to black and brown youth, it attached itself to white, it attached itself to poor, higher class, middle class, people who didn’t even like hip-hop. It sold a lot of records and got a lot of people looking and listening. If you’re talking about in today’s world of streaming, well no. We’re older gentlemen and we’ve been through this enough times. With this Pete and Preme record for example, we went into it as a partnership with Mass Appeal and Nas, and we set things straight on how it’s supposed to be. Of course they can turn around as a company and be like, “watch sampling” and we can listen or not listen. But we are still partners in things as opposed to someone saying not saying nothing and giving you a fuckin’ nickel.

Maseo: Here’s the deal. Regardless of what he wants to give us, the type of business since Tommy Boy’s demise has been nothing but partnerships and better. Why would I do anything less? I know my value. And now, with the slap in the face of not even trying to come to the table, I think I deserve a lot more than that now. I was being more than fair then. What’s really fair now is ownership. That’s what’s really fair. The focus of this discussion is splits. Now we’re talking about ownership and splits.

Besides getting the wrong end of the deal, y’all had creative freedom. Looking back, would you guys have traded some of that creative freedom for a better percentage off those royalties?

Pos: I would say no because there was nowhere someone told us that that was the difference. Tommy Boy never stood in the way of our creative freedom.

Maseo: Made a few suggestions. Even down to when we delivered 3 Feet, they were loving this record. They said, “We don’t hear anything we could go to radio with.” And that was understandable from their standpoint. “We don’t really hear anything that the DJ could spin.” We all got their point, but the thing about that period of time, every artist struggled with not selling out. Understanding this, how could we make a radio record our way? It has to be genuine and honest.

A lot of the records that went on radio were organic and radio picked up on it coming out of the club and the street. It wasn’t the other way around, hence “Me, Myself and I,” which is still a torn feeling because Paul genuinely loved “Funkadelic” and I was always a stickler to use “Knee Deep.” Fellas wasn’t too keen about it. But in having that meeting with Tommy Boy, going to a Zulu Nation party at Hotel Amazon, Jazzy J throwing on “Knee Deep” in the club and everybody going crazy in there, and it’s one of my favorite records, I hit Dave and said, "That’s the one.” I got a call out of nowhere from Paul and he said, “Bring those records to the studio.” We just started putting things together and I could see them in the back not too happy about this, but just letting it go how we normally let things go. Let the creative process happen.

Pos: I was a big fan of that record and even in my mind at that period of time, there were just certain things you shouldn’t touch. That’s such a masterpiece and you’re going to touch that? I just didn’t think taking “Knee Deep” was dope to me, but at the same time, me and Dave said we just wanna fuck off on the rhymes, we’re going to take Jungle Brothers’ cadence “Black Is Black” how they were rhyming, and fuck it off. God was having too much fun with us and said, “I’m going to make this your biggest record.”

In an interview with HipHopDX, Mase, you said that if it weren’t for Quest coming out and talking how he’s been talking, you guys probably would have remained mum regarding your current situation with Tommy Boy.

Pos: A lot of these people were hitting us directly because they were disappointed and concerned. You have one person who’s like, “Fuck that. I’m setting it off.”

Maseo: The trick is they want us to think we won’t ever make money in this. Let’s call it for what it is. The economic side of this is really unfair.

Pos: We’re saying this from a passion standpoint. It’s just being appalled from this bullshit. We’re not some 18-year-old weary guys who transformed into some broke ass middle class middle-aged dudes. We’ve been blessed to be out here making our money without the benefit of benefitting from our catalogue. We’ve been touring, merch, partnerships, sneakers, features, doing all types of stuff. Whether it’s the first to make an album with Nike. We’ve done so many things and keeping ourselves more than afloat.

Maseo: Grammy nomination without Tommy Boy. Let’s talk business here. My value next to his is much stronger. [Tom Silverman] folded. He’s just coming back. He has other businesses going on via sampling companies. That baffles me,too. Why do you wanna go into a business recklessly when you have another business that’s about sampling? Why repeat a behavior that we know has been damaging in the past? That’s the most underlying thing right now. There are still people who would potentially come out the woodworks, paying attention to what’s happening. There’s an asterisk next to our name when it comes to sampling.

We have been deemed copyright criminals. For argument’s sake, let’s say we accept the split. Why are we doing this with potential infractures? It’s not quite clear. His words exactly, “If somebody comes, we’ll deal with it exactly as we dealt with in the past.” And how was that? We settled with whatever we settled with out of court, whether it be a million dollars, $100,00, $50,000.

Pos: And that comes out of the ten percent given to us. I’m just personally trying to make sure you understand that I’m making this clear. I don’t necessarily know what Tommy Boy means in the scheme of things. I don’t give a fuck if they were Def Jam. What is wrong is wrong. If we were on Universal right now and they were talking the same shit, it would be the same energy and same argument. It’s just unfortunately they would have to understand, you just offered us a drip of water out of a money faucet. Hear me out. He literally offered us a drip, but what you have to understand sir is that it may baffle you “Why didn’t the n---er take the drip if water?” is because we’ve been surviving without the faucet on.

We literally, by the grace of our own wit, our own creativity, our own treating people fairly, where we can treat a gentleman like [Warner Music's senior vice president/head of urban marketing], Chris Atlas fairly when he was working at Tommy Boy to where years later he can make sure we get 2 Chainz on our album because he’s the head honcho at Def Jam. We’ve always treated people fairly, so those people always root for us. That’s why I’m not surprised people came out on our behalf. People are like, “Yo, this is De La. These are decent guys.”

Thirty years in the game and you have six albums under Tommy Boy, you’d think especially with what’s been going on the last few days that a sense of morality has to come in where Tom reaches out to have a conversation. Have there been any talks?

Pos: Like I said, man, personally I don’t want to make it seem like I’m attacking this dude. I don’t care about his morality. I’m concerned from a business standpoint trying to understand that in negotiating things, there’s a level of fairness and respect.

Maseo: Especially if you claim the relationship you claim to have with us. It’s clear to us we never had a relationship and he’s always going to do business that’s favorable to him. I did speak to him. I spoke to him a few hours before we did the first interview.

Pos: I didn’t want to talk to him. If he wanted to talk, I wanted him to step up and not be the person that [he] always seems to [be], because I felt he is the person who feels he can talk to us on a more personal standpoint without involving the legal.

Maseo: I was on the phone with legal when that happened, and when he realized that was going on, he got on the phone with his team, which was necessary. I wanted that. What I didn’t want was him being able to say he never spoke to us, because once it hits this and we hadn’t really spoken, based on the relationship he claims he has, he’s a good manipulator. He’s been doing this a long time. He gets you to believe he tried to reach out and try to come to some resolution or we never brought this to his attention. We’ve brought this to his attention. He’s been ignoring us for some time until it got to the final hour where he expected us to be on-board to make things smooth and dandy, and it’s just not.

We’ve been asking him to address these issues for a minute. It’s been up to the final hour when he really addressed this. When he finally addressed it, there were no changes on how he felt things needed to be. He used words like what’s “customary” and what’s “standard”? He can legally do what he wants. The issue that I raise is, in all of doing what you’re able to do, did you clear it? Did you clear the samples when you bought the catalogue back? Is it cleared? And what he said on the phone that if anything comes up, we will deal with it the way we’ve dealt with it in the past. And I know if that happens, we’re going to settle because we’re in the wrong. You notice I’m saying “we.” Why am I saying “we”? Because we suffer from that.

What if by chance somebody just came in and tried to buy the catalog back?

Maseo: I hope that’s an option. I hope that’s possible. At this point, we don’t got nothing to lose. Like Pos said, we’ve been surviving without the faucet.

Pos: It’s just about us trying to stay on course. We’ve always been very respectful. There have been times in the past where we straight up had an issue with how Tommy Boy was doing things. We’ve never, even at a young age, have tried to physically harm anyone up at the office. We’ve never had people try to run up there and do anything. That has been an issue sometimes in our career where we’re the nice guys.

Loyalty is a motherfucker.

Pos: We’ve always tried to treat their company like it was our own.

Maseo: All in all, man, we’ve done things with integrity. Even as children. We’ve apologized for our mistakes and we own our mistakes if there have been any tantrums along the way but there’s never been anything threatening. We deserve better than this, much better than this. There’s nothing to really say anymore. Let the story be told. We don’t mint this being the litmus test for things to come. Maybe this can change legislation. Who knows? This can’t happen to any other artist. It’s totally bigger than us. Let this be a lesson to any artist that’s out there if there’s any other artist that’s going through this, come out and speak out. We’re setting the tone. Let us know what’s up. Let’s figure out how to stop these culture vultures. I'm going to stop calling names, but it hurts that rich powerful dudes still get down like this greedy manner and think this is OK.

With Jay-Z helping out on the Tidal front, he's someone that has the money to buy the catalog back for you guys, right? Wouldn't that be an option?

Maseo: If someone’s willing to sell. The person has to be willing to sell at the same time. At this point, we see how it goes from here. All I could say is, our story is finally being told.

Pos: Our story is told, but it definitely ain’t over.

Maseo: If the fans want to help out from here on out, don’t press play until this thing is resolved. It’s gonna go up. Just don’t press play.