SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2018

VOLUME SIX NUMBER TWO

Featuring the musics and aesthetic visions of:

SMOKEY ROBINSON

(October 6-12)

(October 6-12)

THE TEMPTATIONS

(October 13-19)

JOHN CARTER

(October 20-26)

MARTHA AND THE VANDELLAS(

MARTHA AND THE VANDELLAS(

October 27-November 2)

RANDY WESTON

(November 3-9)

HOLLAND DOZIER AND HOLLAND

(November 10-16)

JELLY ROLL MORTON

(November 17-23)

BOBBY BRADFORD

(November 24-30)

THE SUPREMES

(December 1-7)

THE FOUR TOPS

(December 8-14)

THE SPINNERS

(December 15-21)

THE STYLISTICS

(December 22-28)https://www.allmusic.com/artist/randy-weston-mn0000396908

Randy Weston

(1926-2018)Artist

Biography by Richard S. Ginell

Placing acclaimed pianist Randy Weston

into narrow, bop-derived categories only tells part of the story of

this restless musician. Starting with the gospel of bop according to Thelonious Monk, Weston emerged in the early '50s with a series of albums on the Riverside label and dates playing alongside such luminaries as Kenny Dorham and Cecil Payne.

A virtuosic player, he also made his mark as a composer, writing songs

like "Saucer Eyes," "Pam's Waltz," "Little Niles," and his most

recognizable composition, "Hi-Fly." From the '60s onward, he spent much

of his time in Africa, living in Morocco and traveling throughout the

continent. He gradually absorbed the letter and spirit of African and

Caribbean rhythms and tunes, welding everything together into a

searching, energizing, often celebratory blend. Over the years, his

wide-ranging artistry garnered numerous accolades, including two Grammy

Award nominations, an NEA Jazz Masters Fellowship, and a 2014 Doris Duke

Award.

Growing up in Brooklyn, Weston was surrounded by a rich musical community: he knew Max Roach, Cecil Payne, and Duke Jordan; Eddie Heywood lived across the street; Wynton Kelly was a cousin. Most influential of all was Monk, who tutored Weston upon visits to his apartment. Weston began working professionally in R&B bands in the late '40s before playing in the bebop outfits of Payne and Kenny Dorham. After signing with Riverside in 1954, Weston

led his own trios and quartets and attained a prominent reputation as a

composer, contributing jazz standards like "Hi-Fly" and "Little Niles"

to the repertoire and releasing albums like Jazz á la Bohemia, The Modern Art of Jazz, and New Faces at Newport. He also met arranger Melba Liston, who collaborated with Weston off and on from the late '50s into the 1990s.

Weston's

interest in his roots was stimulated by extended stays in Africa; he

visited Nigeria in 1961 and 1963, during which time he issued albums

like Highlife: Music from the New African Nations, Randy!, and African Cookbook.

He lived in Morocco from 1968 to 1973 following a tour, and

subsequently remained fascinated with the music and spiritual values of

the continent. In the '70s, Weston

made recordings for Arista-Freedom, Polydor, and CTI while maintaining a

peripatetic touring existence, mostly in Europe. His albums like Blue Moses, Tanjah (which earned him his first Grammy nomination in 1973), and Perspective

found him continuing to incorporate African influences along with funk

and soul-jazz, while moving between large-ensemble and small-group sets.

However, starting in the late '80s, after a period when his recording had slowed, Weston's

visibility in the U.S. skyrocketed with an extraordinarily productive

period in the studios for Antilles and Verve. His highly eclectic

recording projects included a trilogy of "Portrait" albums depicting Ellington, Monk, and himself; The Spirits of Our Ancestors, an ambitious two-CD work rooted in African music; a blues album; and a Grammy-nominated collaboration with the Gnawa Musicians of Morocco. Weston's fascination with the music of Africa continued on such works as 2003's Spirit! The Power of Music, 2004's Nuit Africaine, and 2006's Zep Tepi by Weston and his African Rhythms Trio.

In 2010, Weston released the live album The Storyteller,

which featured the then 84-year-old pianist in concert at Dizzy's Club

Coca-Cola as part of Jazz at Lincoln Center. Three years later, he

paired with Billy Harper for The Roots of the Blues. The African Nubian Suite,

an ambitious project conceptualized around Africa's heritage as the

birthplace of humanity and civilization, followed in 2016. Weston issued the solo piano album Sound in 2018. On September 1 of that year, he died at his home in Brooklyn at the age of 92.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/randyweston

After contributing six decades of musical direction and genius, Randy Weston remains one of the world's foremost pianists and composers today, a true innovator and visionary. Encompassing the vast rhythmic heritage of Africa, his global creations musically continue to inform and inspire. “Weston has the biggest sound of any jazz pianist since Ellington and Monk, as well as the richest most inventive beat,” states jazz critic Stanley Crouch, “but his art is more than projection and time; it's the result of a studious and inspired intelligence...an intelligence that is creating a fresh synthesis of African elements with jazz technique”.

Randy Weston, born in Brooklyn, New York in 1926, didn't have to travel far to hear the early jazz giants that were to influence him. Though Weston cites Count Basie, Nat King Cole, Art Tatum, and of course, Duke Ellington as his other piano heroes, it was Monk who had the greatest impact. “He was the most original I ever heard,” Weston remembers. “He played like they must have played in Egypt 5000 years ago.”

Randy Weston’s first recording as a leader came in 1954 on Riverside Records “Randy Weston plays Cole Porter - Cole Porter in a modern mood.” It was in the 50's when Randy Weston played around New York with Cecil Payne and Kenny Dorham that he wrote many of his best loved tunes, “Saucer Eyes,” “Pam's Waltz,” “Little Niles,” and, “Hi-Fly.” His greatest hit, “Hi-Fly,” Weston (who is 6' 8”) says, is a “tale of being my height and looking down at the ground

Randy Weston has never failed to make the connections between African and American music. His dedication is due in large part to his father, Frank Edward Weston, who told his son that he was, “an African born in America.” “He told me I had to learn about myself and about him and about my grandparents,” Weston said in an interview, “and the only way to do it was I'd have to go back to the motherland one day.”

In the late 60's, Weston left the country. But instead of moving to Europe like so many of his contemporaries, Weston went to Africa. Though he settled in Morocco, he traveled throughout the continent tasting the musical fruits of other nations. This led him to settle in Morocco in 1968, where he continued to tour and perform throughout Morocco, Tunisia, Togo, the Ivory Coast, and Liberia.

Weston has made more than fifty recordings throughout his lifetime, the most celebrated including “African Cookbook,” “Little Niles,” “Blue Moses,” “Berkshire Blues,” “Uhuru Africa,” ( in collaboration with arranger Melba Liston) and Grammy-nominated “Tanjah” and “Carnaval.” A prolific composer, Weston’s highly individualistic works have been recorded by jazz virtuosi like Max Roach, Monty Alexander, Dexter Gordon, Jimmy Heath, Kenny Burrell, Abbey Lincoln, Bobby Hutchinson, Lionel Hampton, and Cannonball Adderly.

Weston is an articulate spokesman on the pivotal position of African music, dance, and other arts within world culture; on the diversity and importance of Africa’s vast musical resources; and on encouraging true cultural exchange and mutual learning between creative artists.

In 2006 Brooklyn College honored him with the honorary degree “Doctor of Music”

In 2003 New York University honored him with two weeks artist-in-residence and tribute concert

In 2001 He received the Jazz Masters Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts

In 2000 He received the Arts Critics and Reviewers Ass. of Ghana, Black Music Star Award

In 1999 Harvard University honored him with a 1 week residency and tribute concert

In 1997 He received The French Order Of Arts And Letters

In 1995 The Montreal Jazz Festival gave him a 5 night tribute.

In 1999, 1996 and 1994 he also won Composer of the year from Downbeat Magazine

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/randyweston

Randy Weston

Randy Weston

After contributing six decades of musical direction and genius, Randy Weston remains one of the world's foremost pianists and composers today, a true innovator and visionary. Encompassing the vast rhythmic heritage of Africa, his global creations musically continue to inform and inspire. “Weston has the biggest sound of any jazz pianist since Ellington and Monk, as well as the richest most inventive beat,” states jazz critic Stanley Crouch, “but his art is more than projection and time; it's the result of a studious and inspired intelligence...an intelligence that is creating a fresh synthesis of African elements with jazz technique”.

Randy Weston, born in Brooklyn, New York in 1926, didn't have to travel far to hear the early jazz giants that were to influence him. Though Weston cites Count Basie, Nat King Cole, Art Tatum, and of course, Duke Ellington as his other piano heroes, it was Monk who had the greatest impact. “He was the most original I ever heard,” Weston remembers. “He played like they must have played in Egypt 5000 years ago.”

Randy Weston’s first recording as a leader came in 1954 on Riverside Records “Randy Weston plays Cole Porter - Cole Porter in a modern mood.” It was in the 50's when Randy Weston played around New York with Cecil Payne and Kenny Dorham that he wrote many of his best loved tunes, “Saucer Eyes,” “Pam's Waltz,” “Little Niles,” and, “Hi-Fly.” His greatest hit, “Hi-Fly,” Weston (who is 6' 8”) says, is a “tale of being my height and looking down at the ground

Randy Weston has never failed to make the connections between African and American music. His dedication is due in large part to his father, Frank Edward Weston, who told his son that he was, “an African born in America.” “He told me I had to learn about myself and about him and about my grandparents,” Weston said in an interview, “and the only way to do it was I'd have to go back to the motherland one day.”

In the late 60's, Weston left the country. But instead of moving to Europe like so many of his contemporaries, Weston went to Africa. Though he settled in Morocco, he traveled throughout the continent tasting the musical fruits of other nations. This led him to settle in Morocco in 1968, where he continued to tour and perform throughout Morocco, Tunisia, Togo, the Ivory Coast, and Liberia.

Weston has made more than fifty recordings throughout his lifetime, the most celebrated including “African Cookbook,” “Little Niles,” “Blue Moses,” “Berkshire Blues,” “Uhuru Africa,” ( in collaboration with arranger Melba Liston) and Grammy-nominated “Tanjah” and “Carnaval.” A prolific composer, Weston’s highly individualistic works have been recorded by jazz virtuosi like Max Roach, Monty Alexander, Dexter Gordon, Jimmy Heath, Kenny Burrell, Abbey Lincoln, Bobby Hutchinson, Lionel Hampton, and Cannonball Adderly.

Weston is an articulate spokesman on the pivotal position of African music, dance, and other arts within world culture; on the diversity and importance of Africa’s vast musical resources; and on encouraging true cultural exchange and mutual learning between creative artists.

In 2006 Brooklyn College honored him with the honorary degree “Doctor of Music”

In 2003 New York University honored him with two weeks artist-in-residence and tribute concert

In 2001 He received the Jazz Masters Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts

In 2000 He received the Arts Critics and Reviewers Ass. of Ghana, Black Music Star Award

In 1999 Harvard University honored him with a 1 week residency and tribute concert

In 1997 He received The French Order Of Arts And Letters

In 1995 The Montreal Jazz Festival gave him a 5 night tribute.

In 1999, 1996 and 1994 he also won Composer of the year from Downbeat Magazine

http://www.wbgo.org/post/pianist-randy-weston-eloquent-spokesman-jazzs-bond-african-culture-dies-92#stream/0

Pianist Randy Weston, An Eloquent Spokesman For Jazz's Bond with African Culture, Dies at 92

Randy

Weston, a pianist and composer who devoted more than half a century to

the exploration of jazz’s deep connection with Africa, died on Saturday

at his home in Brooklyn. He was 92.

His death was announced by his wife and business partner, Fatoumata Weston.

Over the course of an extraordinarily long and distinguished career, Weston carried on the pianistic and composerly tradition of Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk before him. But he was steadfast in a specific sense of mission: he regarded jazz as an extension of African music, from its foundational essence to its living expression. He made this argument not only in eloquent conversation but also in powerful musical terms, often in recent years with his band African Rhythms.

An imposingly tall but soft-spoken man, Weston embodied the connections he espoused. His touch at the piano was emphatically percussive, but also elegant, resonant and clear. He worked with a sophisticated harmonic language often shaded in blue, and in his compositions — like “Hi-Fly” and “Little Niles,” which have become standards — he drew an unmistakable line from the African continent to the swinging verities of hard-bop and other strains of modern jazz.

“When you go to Africa, you become very humble,” Weston told Sheila Anderson last year, in a Salon Session interview at WBGO. “You realize that you are from thousands and thousands of years of civilization, and how much we have to learn from these people.”

Weston

made his first visit to the African continent in 1961, as part of a

tour for the U.S. State Department. He visited Lagos, Nigeria on that

trip, and returned there under the same auspices two years later. After a

third visit in 1967, he decided to move to Morocco, finding deep

spiritual resonance in the traditional music of the Gnawa. In Tangier,

he opened and operated a popular jazz club, also called African Rhythms,

from the late ‘60s into the ‘70s.

But it would be an oversimplification to imply that Weston had an awakening during his trips abroad. Born in Brooklyn, New York, on April 6, 1926, he came up in a household conversant in African culture. His mother, Vivian, was born in Virginia; his father, Frank, was Panamanian, and a strong admirer of Marcus Garvey, whose pan-African message made a formative impression.

Weston studied classical piano before his professional career began after the Second World War, with bluesmen like Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson and Bullmoose Jackson. He encountered some important encouragement when, in 1951, he took a summer job as a breakfast chef at the Music Inn in the Berkshires. There he met the scholar and historian Marshall Stearns, who eventually asked Weston to accompany his lectures, some of which drew a decisive musicological lineage between jazz and the folkloric music of West Africa.

That connection gradually became more legible to Weston. “My good friend, the bassist Ahmad Abdul-Malik’s people were from the Sudan, and he played the oud, which has this thing of playing notes between the notes,” he recalled roughly a decade ago, in an appearance on NPR’s Piano Jazz. “I couldn’t get that sound on the piano. But when I heard Thelonious Monk play, I heard this same magic on the piano; even his way of swinging had that same element.”

Weston released his debut album, Cole Porter in a Modern Mood, on Riverside Records in 1954. The following year he was named New Star Pianist in the Down Beat International Critics' Poll. When he then released The Randy Weston Trio, featuring Sam Gill on bass and Art Blakey on drums, it notably opened with a composition titled “Zulu.”

During the ‘60s, Weston released a succession of boldly realized albums, including Uhuru Africa, which featured African hand drumming front and center, alongside a big band stacked with talent: Clark Terry, Yusef Lateef, Max Roach and Gigi Gryce, just for starters. The arrangements were by Melba Liston, a close collaborator who also worked with Weston on albums like Highlife (1963), Tanjah (1973) and The Spirits of Our Ancestors (1991).

But Uhuru Africa, which also incorporates lyrics and poetry by Langston Hughes, belongs in a category of its own. As Robin D.G. Kelley has observed, the album “acknowledged Africa’s cultural ties to its descendants, honored African womanhood and promoted the idea of a modern Africa, a beacon for a new future.”

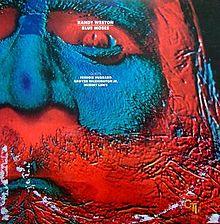

Weston had some more commercial outings in the ‘70s, none more so than Blue Moses, released on CTI Records. It features Freddie Hubbard in peak swashbuckling form, and a rhythm team that often features bassist Ron Carter and drummer Billy Cobham, along with several percussionists.

In African Rhythms: The Autobiography of Randy Weston, a book written with Willard Jenkins and published in 2010, Weston recalls being unpleasantly surprised by the slick production of Blue Moses, but appreciative of the fact that it was the biggest hit of his career.

By and large, Weston’s success was less a matter of commercial performance than cultural influence. He was a 2001 NEA Jazz Master, a 2011 Guggenheim Fellow, and a 2016 inductee in the DownBeat Critic’s Poll Hall of Fame. He won a 2014 Doris Duke Artist Award and received several honorary doctorate degrees. Two years ago his personal trove of musical scores, correspondence, recordings and other materials were acquired by Harvard Library, in collaboration with the Jazz Research Initiative at the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research.

Along with his wife, Weston is survived by three of his four children, Cheryl, Pamela and Kim; seven grandchildren; six great grandchildren; and one great-great grandchild.

Last year Weston released The African Nubian Suite — his 50th album, and the first on his own African Rhythms label, supported by a Guggenheim Fellowship. Recorded in concert in 2012 at New York University’s Skirball Center for the Performing Arts, it features narration by the scholar Wayne Chandler and poetry by the late Jayne Cortez.

Weston was planning to tour and record when he died; his fall calendar was to include an Oct. 17 concert for the World Music Institute at the New School. His message now lives on in his recordings and concert footage, and will continue to exert influence by personal example. “When I touch the piano,” he said in an All Things Considered profile last year, “it becomes an African instrument. It’s no longer a European instrument. I say that in a positive way, not a negative way.”

A previous version of this story, relying on information from a publicist, mistated Randy Weston's award from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. It was a Doris Duke Artist Award, not a Doris Duke Impact Award.

His death was announced by his wife and business partner, Fatoumata Weston.

Over the course of an extraordinarily long and distinguished career, Weston carried on the pianistic and composerly tradition of Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk before him. But he was steadfast in a specific sense of mission: he regarded jazz as an extension of African music, from its foundational essence to its living expression. He made this argument not only in eloquent conversation but also in powerful musical terms, often in recent years with his band African Rhythms.

An imposingly tall but soft-spoken man, Weston embodied the connections he espoused. His touch at the piano was emphatically percussive, but also elegant, resonant and clear. He worked with a sophisticated harmonic language often shaded in blue, and in his compositions — like “Hi-Fly” and “Little Niles,” which have become standards — he drew an unmistakable line from the African continent to the swinging verities of hard-bop and other strains of modern jazz.

“When you go to Africa, you become very humble,” Weston told Sheila Anderson last year, in a Salon Session interview at WBGO. “You realize that you are from thousands and thousands of years of civilization, and how much we have to learn from these people.”

But it would be an oversimplification to imply that Weston had an awakening during his trips abroad. Born in Brooklyn, New York, on April 6, 1926, he came up in a household conversant in African culture. His mother, Vivian, was born in Virginia; his father, Frank, was Panamanian, and a strong admirer of Marcus Garvey, whose pan-African message made a formative impression.

Weston studied classical piano before his professional career began after the Second World War, with bluesmen like Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson and Bullmoose Jackson. He encountered some important encouragement when, in 1951, he took a summer job as a breakfast chef at the Music Inn in the Berkshires. There he met the scholar and historian Marshall Stearns, who eventually asked Weston to accompany his lectures, some of which drew a decisive musicological lineage between jazz and the folkloric music of West Africa.

That connection gradually became more legible to Weston. “My good friend, the bassist Ahmad Abdul-Malik’s people were from the Sudan, and he played the oud, which has this thing of playing notes between the notes,” he recalled roughly a decade ago, in an appearance on NPR’s Piano Jazz. “I couldn’t get that sound on the piano. But when I heard Thelonious Monk play, I heard this same magic on the piano; even his way of swinging had that same element.”

Weston released his debut album, Cole Porter in a Modern Mood, on Riverside Records in 1954. The following year he was named New Star Pianist in the Down Beat International Critics' Poll. When he then released The Randy Weston Trio, featuring Sam Gill on bass and Art Blakey on drums, it notably opened with a composition titled “Zulu.”

During the ‘60s, Weston released a succession of boldly realized albums, including Uhuru Africa, which featured African hand drumming front and center, alongside a big band stacked with talent: Clark Terry, Yusef Lateef, Max Roach and Gigi Gryce, just for starters. The arrangements were by Melba Liston, a close collaborator who also worked with Weston on albums like Highlife (1963), Tanjah (1973) and The Spirits of Our Ancestors (1991).

But Uhuru Africa, which also incorporates lyrics and poetry by Langston Hughes, belongs in a category of its own. As Robin D.G. Kelley has observed, the album “acknowledged Africa’s cultural ties to its descendants, honored African womanhood and promoted the idea of a modern Africa, a beacon for a new future.”

Weston had some more commercial outings in the ‘70s, none more so than Blue Moses, released on CTI Records. It features Freddie Hubbard in peak swashbuckling form, and a rhythm team that often features bassist Ron Carter and drummer Billy Cobham, along with several percussionists.

In African Rhythms: The Autobiography of Randy Weston, a book written with Willard Jenkins and published in 2010, Weston recalls being unpleasantly surprised by the slick production of Blue Moses, but appreciative of the fact that it was the biggest hit of his career.

By and large, Weston’s success was less a matter of commercial performance than cultural influence. He was a 2001 NEA Jazz Master, a 2011 Guggenheim Fellow, and a 2016 inductee in the DownBeat Critic’s Poll Hall of Fame. He won a 2014 Doris Duke Artist Award and received several honorary doctorate degrees. Two years ago his personal trove of musical scores, correspondence, recordings and other materials were acquired by Harvard Library, in collaboration with the Jazz Research Initiative at the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research.

Along with his wife, Weston is survived by three of his four children, Cheryl, Pamela and Kim; seven grandchildren; six great grandchildren; and one great-great grandchild.

Last year Weston released The African Nubian Suite — his 50th album, and the first on his own African Rhythms label, supported by a Guggenheim Fellowship. Recorded in concert in 2012 at New York University’s Skirball Center for the Performing Arts, it features narration by the scholar Wayne Chandler and poetry by the late Jayne Cortez.

Weston was planning to tour and record when he died; his fall calendar was to include an Oct. 17 concert for the World Music Institute at the New School. His message now lives on in his recordings and concert footage, and will continue to exert influence by personal example. “When I touch the piano,” he said in an All Things Considered profile last year, “it becomes an African instrument. It’s no longer a European instrument. I say that in a positive way, not a negative way.”

A previous version of this story, relying on information from a publicist, mistated Randy Weston's award from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. It was a Doris Duke Artist Award, not a Doris Duke Impact Award.

Tags: Randy Weston. RIP

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/01/obituaries/randy-weston-dead.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/01/obituaries/randy-weston-dead.html

All,

Randy was a GIANT whose legacy is immense.

I was very fortunate to have seen and heard the man

on many occasions when I lived in Boston and New York during the ‘70s and ‘80s and he never failed to have a riveting impact on his audiences both as a consummate musician/composer/performer and scholar/spokesman for the music as both a national and disaporic force. Thankfully the fact that he did live a long and productive life (and produced many indelible recordings especially during the ‘golden age’ of the music from the late 1940s to the 1980s and beyond means that he and his indispensable contributions will never die. "HI-FLY" indeed…

Randy Weston, Pianist Who Traced Roots of Jazz to Africa, Dies at 92

New York Times

Randy

Weston, an esteemed pianist whose music and scholarship advanced the

argument — now broadly accepted — that jazz is, at its core, an African

music, died on Saturday at his home in Brooklyn. He was 92.

His death was confirmed by his lawyer, Gail Boyd.

On

his earliest recordings, in the mid-1950s for the Riverside label, Mr.

Weston almost fit the profile of a standard bebop musician: He recorded jazz standards and galloping original tunes in a typical small-group format.

But his sharply cut harmonies and intense, gnarled rhythms conveyed a

manifestly Afrocentric sensibility, one that was slightly more barbed

and rugged than the popular hard-bop sound of the day.

Early

on, he exhibited a distinctive voice as a composer. “Hi-Fly,” which he

first released in 1958 on the LP “New Faces at Newport,” became a

standard. And he eventually distinguished himself as a solo pianist,

reflecting the influence of his main idol, Thelonious Monk.

But more than Monk, Mr. Weston liked constantly to reshape his cadences, rarely lingering on a steady pulse.

Reviewing a concert

in 1990, Peter Watrous of The New York Times wrote of Mr. Weston,

“Everything he played was edited to the essential notes of a phrase, and

each phrase stood on its own, carefully separated from the next one;

Mr. Weston sat rippling waves of notes down next to glossy and

percussive octaves, which led logically to meditative chords.”

At 6 feet 7 inches tall, often favoring flowing garments from North or West Africa, Mr. Weston was an imposing, though genial, figure whether performing onstage or teaching in university classrooms. Even before making his first album, he was giving concerts and teaching seminars that emphasized the African roots of jazz. This flew in the face of the prevailing narrative at the time, which cast jazz as a broadly American music, and as a kind of equal-opportunity soundtrack to racial integration.

“Wherever I go, I try to explain that if you love music, you have to know where it came from,” Mr. Weston told the website All About Jazz in 2003. “Whether you say jazz or blues or bossa nova or samba, salsa — all these names are all Africa’s contributions to the Western Hemisphere. If you take out the African elements of our music, you would have nothing.”

As countries across Africa shook themselves free of colonial exploitation in the mid-20th century, Mr. Weston recorded albums that explicitly saluted the struggle for self-determination. “Uhuru Afrika” (the title is Swahili for “Freedom Africa”), released in 1960, included lyrics written by Langston Hughes, and sales were banned in South Africa by its apartheid regime.

That album — and others throughout his career — featured the marbled horn arrangements of the trombonist Melba Liston, who left an indelible stamp on Mr. Weston’s oeuvre.

In

1959 he became a central member of the United Nations Jazz Society, a

group seeking to spread jazz throughout the world, particularly in

Africa. In 1961 he visited Nigeria as part of a delegation of the

American Society for African Culture, beginning a lifelong

trans-Atlantic exchange.

After two

more trips to Africa, he moved to Morocco, in 1968, having first arrived

there on a trip sponsored by the State Department. He stayed for five

years, living first in Rabat and then in Tangier, where he ran the

African Rhythms Cultural Center, a performance venue that fostered

artists from various traditions.

Mr. Weston drew particular inspiration from musicians of the Gnawa tradition, whose music centered on complex, commingled rhythms and low drones. While in Morocco he established a rigorous international touring regimen and played often in Europe.

In the late 1980s and early ’90s, Mr. Weston released a series of high-profile recordings for the Verve label, all to critical acclaim. Those included tributes to his two greatest American influences, Duke Ellington and Monk, as well as a record dedicated to his own compositions, “Self Portraits,” from 1989.

Mr. Weston earned Grammy nominations in 1973 for his album “Tanjah” (for best jazz performance by a big band), and in 1995 for “The Splendid Master Gnawa Musicians of Morocco” (in the best world music album category), a recording that he produced and released under his name but on which he left most of the playing to 11 Moroccan musicians.

In 2001, the National Endowment for the Arts gave Mr. Weston its Jazz Masters award, the highest accolade available to a jazz artist in the United States. He was voted into DownBeat magazine’s hall of fame in 2016.

Randolph Edward Weston was born in Brooklyn on April 6, 1926. His father, Frank, was a barber and restaurateur who had emigrated from Panama and studied his African heritage with pride. His mother, Vivian (Moore) Weston, was a domestic worker who had grown up in Virginia.

Though

his parents split up when he was 3, they stayed on good terms and lived

near each other in Brooklyn. Randy spent time with both throughout his

childhood, receiving his father’s teachings about the cultures of Africa

and the Caribbean while absorbing the music of the African-American

church from his mother, who made sure that Randy and his half sister,

Gladys, were in the pews every Sunday.

In his memoir, “African Rhythms” (2010), written with Willard Jenkins, Mr. Weston recalled that his father — a supporter of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association — hung “maps and portraits of African kings on the walls, and was forever talking to me about Africa.”

Mr. Weston wrote of his father, “He was planting the seeds for what I would become as far as developing my consciousness of the plight of Africans all over the world.”

Mr. Weston took

classical piano lessons as a child but did not fall in love with the

instrument until he started studying with a teacher who encouraged his

already growing interest in jazz, particularly the music of Ellington,

Count Basie and the saxophonist Coleman Hawkins.

Mr. Weston was drafted into the Army in 1944 while World War II was underway, serving three years in an all-black unit under the military’s segregationist policies and rising to staff sergeant. While stationed in Okinawa, Japan, he was in charge of managing supplies, and frequently tried to share leftover materials and food with local residents, many of whom had lost their homes in the war.

Upon returning to Brooklyn, he took over managing his father’s restaurant, Trios, which became a hub of intellectuals and artists. Mr. Weston began playing jazz and R&B gigs in the borough, seeking wisdom from older musicians. He became particularly close to Monk.

“When I heard Monk play, his sound, his direction, I just fell in love with it,” Mr. Weston told All About Jazz in 2003. “I would pick him up in the car and bring him to Brooklyn, and he was a great master because, for me, he put the magic back into the music.”

Heroin use was rampant on the jazz scene then, and Mr. Weston sometimes used the drug, though he never developed a full-blown addiction. In 1951 he left New York, seeking a fresh start in Lenox, Mass. He made frequent trips to the Music Inn, a venue in nearby Stockbridge, and while working there he met Marshall Stearns, a leading jazz scholar with strong beliefs about jazz’s West African roots, who was giving lectures and leading workshops there.

Mr. Weston started to perform regularly, and he and Mr. Stearns collaborated on a series of round tables about the history of jazz. Mr. Weston met musicians from across the African diaspora, including the Nigerian drummer Babatunde Olatunji, the Cuban percussionist Cándido Camero and the Sierra Leonean drummer Asadata Dafora.

When he returned to Brooklyn, he was brimming with ideas about the synchrony of African tradition and jazz innovation.

He later received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and United States Artists, as well as awards from the Moroccan government and the Institute of the Black World.

He held honorary doctorates of music from Brooklyn College, Colby College and the New England Conservatory, and had served as artist in residence at universities around New York City. Mr. Weston’s papers are archived at Harvard University’s Hutchins Center for African & African American Research.

He is survived by his wife, Fatoumata Mbengue; three daughters, Cheryl, Pamela and Kim; seven grandchildren; six great-grandchildren; and one great-great-grandchild. Mr. Weston’s first marriage, to Mildred Mosley, ended in divorce. A son, Azzedin, is deceased.

In 2016, he released his 50th and final album as a bandleader, the two-disc “African Nubian Suite,”

which featured an orchestra-size iteration of African Rhythms. Through

music and spoken word, the suite traces humanity’s origins back to the

Nile River delta.

His last public concert was in July at the Nice Jazz Festival in France, with his African Rhythms Quintet. At his death, his website listed performances scheduled through October.

For Mr. Weston,

music was a way of connecting histories with the present, and a communal

undertaking. Looking back on his career, he told All About Jazz: “I

have been blessed because I have been around some of the most fantastic

people on the planet. I have become a composer and become a pianist. I

couldn’t ask for anything more.”

A version of this article appears in print on , on Page D8 of the New York edition with the headline: Randy Weston, Pianist Who Emphasized The African Roots of Jazz, Is Dead at 92. Order Reprints | Today’s Pape

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/11216655/Randy-Weston-interview-African-music-is-for-the-world.html

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/11216655/Randy-Weston-interview-African-music-is-for-the-world.html

Randy Weston interview: 'African music is for the world'

The great jazz pianist talks about racism, discovering Africa and the power of music to change lives

The power of positive thinking is something the great jazz

pianist and composer Randy Weston has never had to learn. Now aged 88,

he exudes a wise benevolence which sees the good side of everything.

Even the memory of the racism that marked his early life is something he

recounts mildly, without rancour.

It’s as if Weston is attached by a hidden umbilical chord to some secret

source of nourishment, and it soon becomes clear what that is. “You

know, every day I give thanks for the culture I grew up in, in

Brooklyn,” he says. “Our parents would bring all kinds of music into the

house, it could be Billie Holiday or

Duke Ellington or Louis Armstrong. They used to take us to the Apollo

Theatre to hear shows.” Was it mostly jazz they listened to? “Oh no, it

was all kinds, jazz, calypso, gospel. It was all part of our

African-American heritage, even if we didn’t play it. And we heard

classical music too, when we went to the opera.”

Young Randy soaked it all up, and soon began taking lessons. “It was

something everybody did, it was a requirement not just in my household,

but the neighbourhood.” One gets the sense of a constant effort at

self-improvement in the black community, coupled with a pride in their

cultural roots. “When I was six my father said to me, ‘My son, you’re an

African born in America. The only history you’re ever going to hear is

the one about colonialism and slavery, but you need to learn about the

great African empires.’ So we would go to the museum and look at the

artefacts from Nubia and Ghana. I used to dream as a kid of these things.”

Getting in touch with his roots wasn’t just a

matter of learning a suppressed history. The young Weston was

inculcated into a whole way of thinking about music. “We look on music

as something that has a role in the community, not just for

entertainment. A musician is a storyteller and healer, he makes music

for a baby being born, music for harvesting. African music is rooted in

the sounds of Mother Nature, of wind and bird songs and animal sounds.

Even the instruments are rooted in daily life. You don’t go to the shop

to make an instrument, you make one yourself, with whatever is around

you. That’s how it was in Africa, and wherever African people have been

taken they’ve kept their memory of art. You see the same thing in Cuba

and Venezuela and Brazil.”

All this would bear fruit in Weston’s own music, but first he had to master African music in its local, acceptable form: jazz. And that wasn’t easy, at a time when the bar was set so high. “You got to remember this was the time of great jazz pianists like Willie 'The Lion' Smith, Eddie Condon, Nat King Cole, Art Tatum. These are our royalty. So I never thought I could turn professional. Of course I was playing before that, at local gigs and dances and so forth. But faced with that perfection and originality I was bound to be a little timid, until I realised I had something to say.”

Then in the 1960s came the reunion with Africa he’d always dreamed

of. “First I went to Nigeria in 1961, with 29 American artists including

the poet Langston Hughes, who I wrote a piece with, and Lionel Hampton

and Nina Simone, and two dancers from the Savoy ballroom. I went back to

Lagos in 1963 and I felt so comfortable, like I’d never left. In 1967 I

was asked to do a tour by the State Department, and Morocco was the

last stop. I felt a special bond with that country, because they also

had experienced slavery. Our slavery came from over the Atlantic, theirs

came from over the Sahara desert. I had a club in Tangiers for three

years. We would bring over blues bands from Chicago, singers from the

Congo, from Brazil, from Niger. I wanted to reflect the fact that

African culture has become a global culture.”

It’s only when I ask Weston whether things are better now than in the days of segregation that his optimism dims. “No, because we’ve forgotten the roots of our culture. I always say to young musicians, if you study the roots of music you will have more respect for your elders and your ancestors. The more they learn it, the more they appreciate what African music has given the world, but the problem is it has zero representation in the media.”

But Weston can’t be gloomy for long. “I think when the dust has settled people will go back to the music that is for all times. The great thing about African music is it’s not music for the young, or the old, it’s music for everybody. We have this situation in the modern world where music is something you choose just to please yourself, but with us, music is always for the people.”

Randy Weston appears with Billy Harper and JD Allen at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on 17 November as part of the EFG London Jazz Festival. Tickets: 0844 875 0073; efglondonjazzfestival.org.uk

https://nmbx.newmusicusa.org/remembering-randy-weston-1926-2018-a-true-musical-giant/

On September 1, 2018, we lost a true musical giant, innovator,

NEA Jazz Master, and a warrior for the elevation of African-American

pride and culture. His compositions disseminating the richness and

beauty of the African aesthetic are unparalleled.

Randy Weston was born during an era of extreme racism, segregation, and discrimination in the United States. His life’s mission was one of unfolding the curtain that concealed the wonderful greatness and extraordinary accomplishments inherent on the African continent.

I am super blessed and honored to have been a member of Randy’s band for 38 years. Baba Randy was a spiritual father and mentor for myself, and so many people. Our last public performances were in Rome and Nice in July, with Billy Harper on tenor sax, Alex Blake on bass, Neil Clarke on percussion, and myself on alto saxophone and flute.

I will always remember Weston’s extreme kindness and generosity. My first four impressions of him revealed who he was and what he cherished:

The first time I ever heard Randy Weston perform live was at The East in Bed-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, in the early 1970s. His band was a duo with his son Azzedin on African percussion. The communication and symmetry of father and son were beyond belief. This was a clear demonstration of his love for and mentorship of his children. I also remember Randy inviting the great James Spaulding to sit in on flute.

In the late 1970s, I performed with the legendary South African pianist Abdullah Ibrahim at Ornette Coleman’s Artist House Loft in Soho, New York City. Randy attended this show with his father Frank Edward Weston and his manager Colette. I witnessed first-hand his profound love, respect, and reverence for the elders and his admiration for other musicians especially from the continent of Africa.

Also in the late 1970s, I had my first opportunity to perform with Randy. It was at a fundraiser in support of the South West African People’s Organization, which fought against apartheid in South Africa. This was yet another demonstration of his commitment to the struggle for civil and human rights worldwide.

Then during the summer of 1980, I was overjoyed by having my first hired performance with Randy and his African Rhythms group at the House Of The Lord Church in Brooklyn, which again displayed his support and commitment to keep jazz alive in the black community and his in-depth love for the African-American church.

Much more recently, when my mom Lois Marie Rhynie passed in 2014, there was a last-minute issue with the church piano. Weston paid for the rental of a beautiful baby grand and performed gratis.

My last visit to Randy’s place in Brooklyn was on August 18, 2018. He was so happy and energetic. Coincidentally when I walked in the room he was listening to a CD of his solo improvisatory piano incursions of the highest level. With each note and phrase, both of us were in a profound state of excitement. I asked, “Hey Chief, where’s this from?” He candidly replied, “The Spirits of Our Ancestors.”

May 20, 1991 marked the first day recording sessions for The Spirit of Our Ancestors, a landmark recording by Randy Weston and African Rhythms at the world-famous BMG studios in New York City. When I arrived at the building lobby, the elevator door opened and standing inside was Dizzy Gillespie with his longtime close friend and associate Jacques Muyal, who was living in Switzerland. On my first trip to Tangiers in 1985, I visited Jacques’s home and met his mother and brother. Mr. Muyal is an extraordinary gentleman and jazz producer with a deep love of our music.

I was quite overwhelmed knowing I would be on the same recording as the great Dizzy Gillespie, responsible for the major evolution in jazz history called bebop. We hit it off right away and Maestro Gillespie greeted me with a warm smile and hug. Once we started the session I handed Dizzy a Bb trumpet lead sheet for “African Sunrise.” He stated his preference for a concert lead sheet. After his perusal of the music he noticed an E minor7(b5) to A7(b9) resolving to D minor7. Dizzy then went to the piano and said, “Look at the E minor7(b5) as a G minor6 with the 6th in the bass.” Then he proceeded to play the most gorgeous chord progression. He was a pure musical genius! When he later did the first and only take of “African Sunrise,” Dizzy never looked at the music.

Soon to arrive in the studio were the leader Randy Weston and his longtime arranger and trombonist Melba Liston. Melba had recently endured a stroke and was confined to a wheel chair. However she taught herself how to compose and arrange on the computer using her left hand only. (Her right hand was incapacitated due to the stroke.) Preceding this recording Randy and I were performing in Los Angeles and we would frequently check on Melba to see how she was doing health wise and how the arrangements were unfolding.

Shortly after their arrival an A list of jazz practitioners blessed the room with their astonishing presence: First Idrees Sulieman, the great trumpet player and who also could burn on alto sax. Next was Benny Powell and we had become really close since our joint performances and tours for African Rhythms dating back to 1985. (I was also featured on his album Why Don’t You Say Yes, Sometimes? which was recorded around the same time as Spirits of Our Ancestors.)

There were three tenor sax legends. Billy Harper—I first heard Billy with his band at Joe Lee Wilson’s jazz loft The Ladies Fort Festival in the mid-1970s. He was on fire and I also heard him later with Max Roach. Dewey Redman—Dewey often spoke very highly about a young upcoming tenor titan that was not yet very well known, but soon to be the unconquerable master tenor sax player Joshua Redman, who also happened to be his son. It was my first time to play with Dewey and he was also featured with Randy’s band for a concert at Lincoln Center not too long before he passed away. He was a gentle man and a giant on the tenor sax! Up next was Pharoah Sanders—I was a huge fan of Mr. Sanders since my high school days in Long Island. During my senior year the early 1970s “The Creator Has A Master Plan” was our anthem. It was quite awe-inspiring to have an opportunity to record with a master and spiritual beacon of improvisation.

On bass, Alex Blake—Alex and I are best friends and his artistry on the bass is quite breathtaking. This was our first recording together, but I had first heard him in duo with Randy at the Village Vanguard in the mid-1970s. Also on bass, Jamil Nasser—Maestro Jamil and Randy were extremely tight. Randy credited Jamil with introducing him to four great pianists: Oscar Dennard, Lucky Roberts, Phineas Newborn, and Ahmad Jamal. (I was blessed to be a member of Benny Powell’s Quintet since the late 1980s and Jamil was one of the bassists. His knowledge was vast and deeply spiritual.)

Idris Muhammad played the drums. It was my first opportunity to perform with Idris. Wow, he always displayed an in-depth sensibility for the second-line New Orleans aesthetic and kept everything modern with melodic underpinnings. Randy loved Idris dearly and they had previously recorded together for Verve Records. Arriving next was Big Black, an outstanding percussionist. Words are inadequate to describe his dexterous rhythmic interplay and soulful drive on the hand drums rooted in the Mississippi delta blues, jazz, and the traditions of Africa and its diaspora. (I was so overjoyed to perform many concerts with Big Black since then; his sense of time and swing was quite astounding!)

Randy’s son Azzedin Weston also played percussion and his rhythmic pulsating groove remained ever present. He was a natural genius who also spoke several languages fluently and his artwork could rival Picasso’s!!! (We were like brothers and I was very sad at his passing.)

Finally, there was Yassir Chadly on genbri and karkaba. Yassir was part of the Gnawa musical tradition from Morocco and he resided on the west coast. Randy’s original plan was to have six Gnawa musicians from Morocco but they were not allowed visas at the last minute. Yassir did a wonderful job as their replacement.

I will always remember Randy’s extreme happiness to have so many heavyweights in the same room. Randy treated all of the musicians as family and our respect for the Chief was quite evident. There was so much history between Randy and Melba, Melba and Dizzy, Idres Sulieman and Jamil Nasser, Big Black and Randy—they already had tremendous musical collaborations during one of the most fruitful and fertile period of jazz’s evolution. But there was an unbelievable bond established among all participants. The first 2 and 1/2 hours of very expensive studio time was dedicated solely to warm greetings, hugs, handshakes, more hugs, more handshakes, etc.

Finally the producer asked me to help him coral the troops so we could start recording. It was physically difficult for Melba to direct, so I was called to the task. I also had to solo after Dizzy on “African Sunrise,” which was a daunting endeavor. Melba wrote some immensely memorable arrangements capturing the spirit of our ancestors. Please check out the three tenor saxophones in battle on “The African Cookbook”!!!

Subsequently I went on to record the following projects with Dr. Weston: Volcano Blues, Saga, Khepera, and Spirit, The Power of Music. And on his last two ensemble recordings—The Storyteller and The African Nubian Suite—my duties included being an associate producer. I was truly fortunate to spend 38 years performing, recording, and touring the world with Randy Weston, a true African Griot.

Randy Weston is the last pianistic link between Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk. His forays into improvisation are clearly a manifestation of the highest tier regarding a creative genius with astounding originality. His compositions are in the pantheon of renowned jazz standards.

Words are inadequate to express my love, admiration, appreciation, and gratitude for such an incredible human being. May his spirit rest in paradise for eternity. We will miss you Baba Randy!!!

https://www.wnyc.org/story/randy-weston-and-billy-harper-in-studio/

On his latest recording, The Roots Of The Blues, Weston continues his longstanding musical collaboration with saxophonist Billy Harper -- a soulful partnership that dates back to the 1974. Recorded in early 2013, the duo's record showcases inventive arrangements and improvisations and a shared love for the blues and rich global music traditions. It's another high mark for the distinguished musicians.

Set List:

AllAboutJazz

In my youth, a television news magazine aired a feature on how the map of the world we, as kids, were taught in school was in fact, biased. In reality, Europe and America are not nearly as vast as they seem in the Thomas Guide and Africa and Asia, not nearly as insignificant. South Africa, for instance, is nearly twice the size of Texas and has a stock exchange that is among the largest in the world. But South Africa, even with pop culture's politically correct fondness of Mandela, is a world away. To history, it must even be farther. And that is why Randy Weston has fought to educate musically, the history of Africa, unbiased by Euro-American stigmas. For that, Weston has been rewarded with mainstream obscurity, critical categorization, and corporate malice. I have a heavy heart most days because of such things. Perhaps in time, we will learn. Until then, may I present, Randy Weston, unedited and in his own words.

All About Jazz: Let's start from the beginning.

Randy Weston: My father wanted me to play music. I loved music, but I didn't think I had any talent. I was lucky to have parents who made sure I took music lessons.

FJ: I was of the understanding that Wynton Kelly was a cousin of yours.

RW: That is right. We were very close. He was playing like that at fifteen years old. Yeah, at fifteen, he was already playing like crazy. He was also a very fine organist. We used to go to his uncle's church and he would play the organ for us. Wynton had perfect pitch. He could hear anything and play it. He was a genius. What a great, great musician and a beautiful human being.

FJ: Your profound relationship with Thelonious Monk has been chronicled as well.

RW: My first real hero of music was Coleman Hawkins when he did 'Body and Soul.' I loved Coleman Hawkins so much that whenever he played in New York, I would go to hear him. I also would experience that he also had the best of the younger musicians. I heard Hank Jones with Coleman Hawkins. I heard Sir Charles Thompson with Coleman Hawkins. I heard a number of people. When I first heard Monk, I heard Monk with Coleman Hawkins. When I heard Monk play, his sound, his direction, I just fell in love with it. I spent about three years just hanging out with Monk. I would pick him up in the car and bring him to Brooklyn and he was a great master because, for me, he put the magic back into the music.

FJ: People fear and condemn what they don't understand.

RW: They sure do.

FJ: Monk fell victim to that due in large part to his reticent personality.

RW: They said that he couldn't play. His thought of a different way to play the piano than what everybody else was playing, so they said that he couldn't play and they recognize him as a great composer. But I heard his piano. When I heard the way he played the piano, that is why I love what he does. People put all kinds of labels on people, but the people who knew, they knew Monk was a master, an absolute master of piano and composition. When I heard him do that, it made me want to be closer to him to learn because when you are with masters like Monk, Duke, and Dizzy and people like that.

It’s only when I ask Weston whether things are better now than in the days of segregation that his optimism dims. “No, because we’ve forgotten the roots of our culture. I always say to young musicians, if you study the roots of music you will have more respect for your elders and your ancestors. The more they learn it, the more they appreciate what African music has given the world, but the problem is it has zero representation in the media.”

But Weston can’t be gloomy for long. “I think when the dust has settled people will go back to the music that is for all times. The great thing about African music is it’s not music for the young, or the old, it’s music for everybody. We have this situation in the modern world where music is something you choose just to please yourself, but with us, music is always for the people.”

Randy Weston appears with Billy Harper and JD Allen at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on 17 November as part of the EFG London Jazz Festival. Tickets: 0844 875 0073; efglondonjazzfestival.org.uk

https://nmbx.newmusicusa.org/remembering-randy-weston-1926-2018-a-true-musical-giant/

Remembering Randy Weston (1926-2018)—A True Musical Giant

Randy Weston was born during an era of extreme racism, segregation, and discrimination in the United States. His life’s mission was one of unfolding the curtain that concealed the wonderful greatness and extraordinary accomplishments inherent on the African continent.

I am super blessed and honored to have been a member of Randy’s band for 38 years. Baba Randy was a spiritual father and mentor for myself, and so many people. Our last public performances were in Rome and Nice in July, with Billy Harper on tenor sax, Alex Blake on bass, Neil Clarke on percussion, and myself on alto saxophone and flute.

I will always remember Weston’s extreme kindness and generosity. My first four impressions of him revealed who he was and what he cherished:

The first time I ever heard Randy Weston perform live was at The East in Bed-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, in the early 1970s. His band was a duo with his son Azzedin on African percussion. The communication and symmetry of father and son were beyond belief. This was a clear demonstration of his love for and mentorship of his children. I also remember Randy inviting the great James Spaulding to sit in on flute.

In the late 1970s, I performed with the legendary South African pianist Abdullah Ibrahim at Ornette Coleman’s Artist House Loft in Soho, New York City. Randy attended this show with his father Frank Edward Weston and his manager Colette. I witnessed first-hand his profound love, respect, and reverence for the elders and his admiration for other musicians especially from the continent of Africa.

Also in the late 1970s, I had my first opportunity to perform with Randy. It was at a fundraiser in support of the South West African People’s Organization, which fought against apartheid in South Africa. This was yet another demonstration of his commitment to the struggle for civil and human rights worldwide.

Then during the summer of 1980, I was overjoyed by having my first hired performance with Randy and his African Rhythms group at the House Of The Lord Church in Brooklyn, which again displayed his support and commitment to keep jazz alive in the black community and his in-depth love for the African-American church.

Much more recently, when my mom Lois Marie Rhynie passed in 2014, there was a last-minute issue with the church piano. Weston paid for the rental of a beautiful baby grand and performed gratis.

My last visit to Randy’s place in Brooklyn was on August 18, 2018. He was so happy and energetic. Coincidentally when I walked in the room he was listening to a CD of his solo improvisatory piano incursions of the highest level. With each note and phrase, both of us were in a profound state of excitement. I asked, “Hey Chief, where’s this from?” He candidly replied, “The Spirits of Our Ancestors.”

May 20, 1991 marked the first day recording sessions for The Spirit of Our Ancestors, a landmark recording by Randy Weston and African Rhythms at the world-famous BMG studios in New York City. When I arrived at the building lobby, the elevator door opened and standing inside was Dizzy Gillespie with his longtime close friend and associate Jacques Muyal, who was living in Switzerland. On my first trip to Tangiers in 1985, I visited Jacques’s home and met his mother and brother. Mr. Muyal is an extraordinary gentleman and jazz producer with a deep love of our music.

I was quite overwhelmed knowing I would be on the same recording as the great Dizzy Gillespie, responsible for the major evolution in jazz history called bebop. We hit it off right away and Maestro Gillespie greeted me with a warm smile and hug. Once we started the session I handed Dizzy a Bb trumpet lead sheet for “African Sunrise.” He stated his preference for a concert lead sheet. After his perusal of the music he noticed an E minor7(b5) to A7(b9) resolving to D minor7. Dizzy then went to the piano and said, “Look at the E minor7(b5) as a G minor6 with the 6th in the bass.” Then he proceeded to play the most gorgeous chord progression. He was a pure musical genius! When he later did the first and only take of “African Sunrise,” Dizzy never looked at the music.

Soon to arrive in the studio were the leader Randy Weston and his longtime arranger and trombonist Melba Liston. Melba had recently endured a stroke and was confined to a wheel chair. However she taught herself how to compose and arrange on the computer using her left hand only. (Her right hand was incapacitated due to the stroke.) Preceding this recording Randy and I were performing in Los Angeles and we would frequently check on Melba to see how she was doing health wise and how the arrangements were unfolding.

Shortly after their arrival an A list of jazz practitioners blessed the room with their astonishing presence: First Idrees Sulieman, the great trumpet player and who also could burn on alto sax. Next was Benny Powell and we had become really close since our joint performances and tours for African Rhythms dating back to 1985. (I was also featured on his album Why Don’t You Say Yes, Sometimes? which was recorded around the same time as Spirits of Our Ancestors.)

There were three tenor sax legends. Billy Harper—I first heard Billy with his band at Joe Lee Wilson’s jazz loft The Ladies Fort Festival in the mid-1970s. He was on fire and I also heard him later with Max Roach. Dewey Redman—Dewey often spoke very highly about a young upcoming tenor titan that was not yet very well known, but soon to be the unconquerable master tenor sax player Joshua Redman, who also happened to be his son. It was my first time to play with Dewey and he was also featured with Randy’s band for a concert at Lincoln Center not too long before he passed away. He was a gentle man and a giant on the tenor sax! Up next was Pharoah Sanders—I was a huge fan of Mr. Sanders since my high school days in Long Island. During my senior year the early 1970s “The Creator Has A Master Plan” was our anthem. It was quite awe-inspiring to have an opportunity to record with a master and spiritual beacon of improvisation.

On bass, Alex Blake—Alex and I are best friends and his artistry on the bass is quite breathtaking. This was our first recording together, but I had first heard him in duo with Randy at the Village Vanguard in the mid-1970s. Also on bass, Jamil Nasser—Maestro Jamil and Randy were extremely tight. Randy credited Jamil with introducing him to four great pianists: Oscar Dennard, Lucky Roberts, Phineas Newborn, and Ahmad Jamal. (I was blessed to be a member of Benny Powell’s Quintet since the late 1980s and Jamil was one of the bassists. His knowledge was vast and deeply spiritual.)

Idris Muhammad played the drums. It was my first opportunity to perform with Idris. Wow, he always displayed an in-depth sensibility for the second-line New Orleans aesthetic and kept everything modern with melodic underpinnings. Randy loved Idris dearly and they had previously recorded together for Verve Records. Arriving next was Big Black, an outstanding percussionist. Words are inadequate to describe his dexterous rhythmic interplay and soulful drive on the hand drums rooted in the Mississippi delta blues, jazz, and the traditions of Africa and its diaspora. (I was so overjoyed to perform many concerts with Big Black since then; his sense of time and swing was quite astounding!)

Randy’s son Azzedin Weston also played percussion and his rhythmic pulsating groove remained ever present. He was a natural genius who also spoke several languages fluently and his artwork could rival Picasso’s!!! (We were like brothers and I was very sad at his passing.)

Finally, there was Yassir Chadly on genbri and karkaba. Yassir was part of the Gnawa musical tradition from Morocco and he resided on the west coast. Randy’s original plan was to have six Gnawa musicians from Morocco but they were not allowed visas at the last minute. Yassir did a wonderful job as their replacement.

I will always remember Randy’s extreme happiness to have so many heavyweights in the same room. Randy treated all of the musicians as family and our respect for the Chief was quite evident. There was so much history between Randy and Melba, Melba and Dizzy, Idres Sulieman and Jamil Nasser, Big Black and Randy—they already had tremendous musical collaborations during one of the most fruitful and fertile period of jazz’s evolution. But there was an unbelievable bond established among all participants. The first 2 and 1/2 hours of very expensive studio time was dedicated solely to warm greetings, hugs, handshakes, more hugs, more handshakes, etc.

Finally the producer asked me to help him coral the troops so we could start recording. It was physically difficult for Melba to direct, so I was called to the task. I also had to solo after Dizzy on “African Sunrise,” which was a daunting endeavor. Melba wrote some immensely memorable arrangements capturing the spirit of our ancestors. Please check out the three tenor saxophones in battle on “The African Cookbook”!!!

Subsequently I went on to record the following projects with Dr. Weston: Volcano Blues, Saga, Khepera, and Spirit, The Power of Music. And on his last two ensemble recordings—The Storyteller and The African Nubian Suite—my duties included being an associate producer. I was truly fortunate to spend 38 years performing, recording, and touring the world with Randy Weston, a true African Griot.

Randy Weston is the last pianistic link between Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk. His forays into improvisation are clearly a manifestation of the highest tier regarding a creative genius with astounding originality. His compositions are in the pantheon of renowned jazz standards.

Words are inadequate to express my love, admiration, appreciation, and gratitude for such an incredible human being. May his spirit rest in paradise for eternity. We will miss you Baba Randy!!!

https://www.wnyc.org/story/randy-weston-and-billy-harper-in-studio/

Randy Weston And Billy Harper: Unearthing The 'Roots Of The Blues'

Randy Weston is one of jazz's most renowned and visionary pianists and composers. Over six decades' Weston has been a true innovator, crafting thoughtful works that seamlessly meld jazz and blues theory with African rhythms.On his latest recording, The Roots Of The Blues, Weston continues his longstanding musical collaboration with saxophonist Billy Harper -- a soulful partnership that dates back to the 1974. Recorded in early 2013, the duo's record showcases inventive arrangements and improvisations and a shared love for the blues and rich global music traditions. It's another high mark for the distinguished musicians.

Set List:

- "Roots Of The Nile" (Randy Weston solo piano)

- "If One Could Only See" (Billy Harper solo sax)

- "Blues To Senegal" (Weston and Harper duo)

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/a-fireside-chat-with-randy-weston-randy-weston-by-aaj-staff.php

byAllAboutJazz

In my youth, a television news magazine aired a feature on how the map of the world we, as kids, were taught in school was in fact, biased. In reality, Europe and America are not nearly as vast as they seem in the Thomas Guide and Africa and Asia, not nearly as insignificant. South Africa, for instance, is nearly twice the size of Texas and has a stock exchange that is among the largest in the world. But South Africa, even with pop culture's politically correct fondness of Mandela, is a world away. To history, it must even be farther. And that is why Randy Weston has fought to educate musically, the history of Africa, unbiased by Euro-American stigmas. For that, Weston has been rewarded with mainstream obscurity, critical categorization, and corporate malice. I have a heavy heart most days because of such things. Perhaps in time, we will learn. Until then, may I present, Randy Weston, unedited and in his own words.

All About Jazz: Let's start from the beginning.

Randy Weston: My father wanted me to play music. I loved music, but I didn't think I had any talent. I was lucky to have parents who made sure I took music lessons.

FJ: I was of the understanding that Wynton Kelly was a cousin of yours.

RW: That is right. We were very close. He was playing like that at fifteen years old. Yeah, at fifteen, he was already playing like crazy. He was also a very fine organist. We used to go to his uncle's church and he would play the organ for us. Wynton had perfect pitch. He could hear anything and play it. He was a genius. What a great, great musician and a beautiful human being.

FJ: Your profound relationship with Thelonious Monk has been chronicled as well.

RW: My first real hero of music was Coleman Hawkins when he did 'Body and Soul.' I loved Coleman Hawkins so much that whenever he played in New York, I would go to hear him. I also would experience that he also had the best of the younger musicians. I heard Hank Jones with Coleman Hawkins. I heard Sir Charles Thompson with Coleman Hawkins. I heard a number of people. When I first heard Monk, I heard Monk with Coleman Hawkins. When I heard Monk play, his sound, his direction, I just fell in love with it. I spent about three years just hanging out with Monk. I would pick him up in the car and bring him to Brooklyn and he was a great master because, for me, he put the magic back into the music.

FJ: People fear and condemn what they don't understand.

RW: They sure do.

FJ: Monk fell victim to that due in large part to his reticent personality.

RW: They said that he couldn't play. His thought of a different way to play the piano than what everybody else was playing, so they said that he couldn't play and they recognize him as a great composer. But I heard his piano. When I heard the way he played the piano, that is why I love what he does. People put all kinds of labels on people, but the people who knew, they knew Monk was a master, an absolute master of piano and composition. When I heard him do that, it made me want to be closer to him to learn because when you are with masters like Monk, Duke, and Dizzy and people like that.

Growing up in New York, I would just go and hang out with these people. So from Monk to Eubie Blake to Bud Powell, every night, I was with the greats. But Monk was the one that really reached me because of his sound. He put the magic, for me, into the music. For me, his music is very natural, very logical, a combination of both. He didn't play a lot of notes. He didn't have to play a lot of notes. He made statements. All of the songs had meaning. He wrote songs about his family. He was a great composer and a great pianist, but he had a different approach. You see, Fred, my first love was Count Basie and what I loved about Basie was that he knew the importance of space. Basie was a master of that and so was Monk. I love them both for that. Ellington also had that sound, that incredible sound, that magical sound on the piano. They would get sounds that are not really in the piano. That's what I loved. To me, he was incredible.

FJ: Do you miss Melba Liston?

RW: Oh, my God, yes. She is with me every second of my life. What a great, great woman. Her commitment to her people, like Duke and Basie and all the older people, they not only just made music, but their music was also a commitment to African people and African-American people. That is why she was so rich. She has written for Motown and for Dizzy and she did concerts with symphony orchestras with me. She was a total arranger, but she had the commitment of her people and this is the key because you can play great, but if you lose you people, something is missing. She paid for that. She sacrificed for that.

FJ: There is a rather sinister tendency in the mainstream media to discredit the contributions of black musicians by breaking their legacies apart into bits and pieces.

RW: That is a great point. Music is free. There is so many directions to go in music. You can be an entertainer or whatever. For me, my music is African rhythms. That is what I call my music. I have been trying to project the history of our music, which is Africa. But as far as categories are concerned, it all depends on each artist. My point is that music is free. You can do or not do. If you want to categorize, you do that. If you don't want to, you don't. That is what is so wonderful about music because there are so many different directions you can go.

FJ: There are antagonists who would claim you have, to a fault, placed too much of an importance on African rhythms.

RW: I have a lot of young people who come to me and thank me for my persistence and my consistency with African music and showing the whole connection and showing that music first happened in Africa in the first place. Before there was a Europe and before there was an Asia, African people created music and we come from that. I have a lot of young people today that come to me and thank me for the work that I have done through the years to show the importance of African heritage, which has enriched the whole, entire world.

As

far as Africa is concerned, my father, when I was six years old, he

said to me, 'My son, you are an African born in America. Don't let

anybody tell you that you are anything else but that. Look in the mirror

and look at me and describe what you see. Therefore, you have to know

your history as an African.' And therefore, as a boy, I was always

reading about Africa before colonialism, before the exploitation and

during the time of great African civilizations. My dad started me at a

very early age and so I had no choice.

Plus, he made me take piano lessons. I was lucky to have two great parents. It all came from them and everything I do is based on what they taught me. All music began in Africa. All music began in Africa. The ancient Egyptians had schools of music. They were the first ones to write music. They were master instrument makers of harps and flutes and horns. So the whole concept of music was created in Africa and then spread to Europe and spread to other parts of the world. Most people don't understand or realize that.

Wherever I go, I try to explain that if you love music, you have to know where it came from. Music was based upon spiritual values. In other words, you can't have a civilization unless they had music. African traditional societies have music for every single activity. So our ancestors brought that concept, even in slavery, they brought that concept to the Americas. So whether we were taken to Brazil or Cuba or Jamaica, whatever, that whole concept of Africa continues. All the names, whether you say jazz or blues or bossa nova or samba, salsa, all these names are all Africa's contributions to the Western hemisphere. If you take out the African elements of our music, you would have nothing. But Africa has been put down so much that we have not had a true history of Africa when it had its great civilizations. So that is where music came from, Africa in the first place.

FJ: Why does modern history being taught in schools today, ignore those contributions?

RW: That is not modern. That has happened from the time we arrived. When you are taken away from your home and you are taken as a slave and your history is taken away. That is not something modern. When I was a kid, luckily, I had strong parents at home that made sure that I knew my history. But at the schools and at the movies, Africa was a place of people who had no culture and no history and the whole world has come from African civilization. Everything has come from African civilization, but you have to take time to read and study and listen and watch and I did all that. When I heard Monk play the piano, I heard African music. You don't hear nothing like that in Europe. It doesn't exist. In traditional African society, there is music for every single activity and that is where we come from. That is why, because of slavery. When you are defeated and you are taken as slaves, the first thing they do is take away your history.

FJ: Is it fear of the black man?

RW: Just ignorance, omission. If you don't get it in school and you don't get it at home, you don't know any better. I would chant like Tarzan just like all the other kids. I didn't know any better because it is not being taught. All humanity comes out of Africa. All people come out of Africa. Africa has enriched the whole, entire planet. Once people start to realize that, then they would have a different way of looking at us. They say that jazz began in New Orleans. That is ridiculous. This music began thousands of years ago. It was just carried on to European instruments, European languages. We have just not had the true history of Mother Africa, which has enriched the whole planet.

FJ: You have made the journey to Africa numerous times.

RW: Yes, I was there this year.

FJ: Has Western civilization changed the face of Africa and have those changes been positive?

RW: That is a very deep question because when I go to Africa, I go for the ancestors. I go for the spirits. I don't go for the people that are there. What I mean by that is, of course, I know people there and of course, I have good friends there and of course, we have the chaos and the sickness and the wars and all the terrible things, but when I go to Africa, I go for the ancestors. I look for the elders. I look for the elder musicians. I look for the monuments. I read the books of the civilizations, of the spirits, and of the ancestors. That never changes. But for me, I have been very fortunate. I have been to fourteen countries in Africa and performed there. Everybody has been very beautiful to me, very wonderful to me, just wonderful. But when I go, I go for the ancestors.

FJ: Your music has gone undocumented for a handful of years.