SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2018

VOLUME SIX NUMBER TWO

ARETHA FRANKLIN

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

SMOKEY ROBINSON

(October 6-12)

THE TEMPTATIONS

(October 13-19)

JOHN CARTER

(October 20-26)

MARTHA AND THE VANDELLAS

(October 27-November 2)

RANDY WESTON

(November 3-9)

HOLLAND DOZIER AND HOLLAND

(November 10-16)

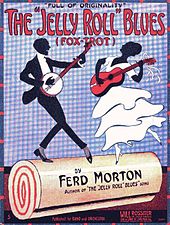

JELLY ROLL MORTON

(November 17-23)

BOBBY BRADFORD

(November 24-30)

THE SUPREMES

(December 1-7)

THE FOUR TOPS

(December 8-14)

THE SPINNERS

(December 15-21)

THE STYLISTICS

(December 22-28)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/jelly-roll-morton-mn0000317290/biography

Jelly Roll Morton

(1890-1941)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

One of the very first giants of jazz, Jelly Roll Morton did himself a lot of harm posthumously by exaggerating his worth, claiming to have invented jazz in 1902. Morton's accomplishments as an early innovator are so vast that he did not really need to stretch the truth.

Morton was jazz's first great composer, writing such songs as "King Porter Stomp," "Grandpa's Spells," "Wolverine Blues," "The Pearls," "Mr. Jelly Roll," "Shreveport Stomp," "Milenburg Joys," "Black Bottom Stomp," "The Chant," "Original Jelly Roll Blues," "Doctor Jazz," "Wild Man Blues," "Winin' Boy Blues," "I Thought I Heard Buddy Bolden Say," "Don't You Leave Me Here," and "Sweet Substitute." He was a talented arranger (1926's "Black Bottom Stomp" is remarkable), getting the most out of the three-minute limitations of the 78 record by emphasizing changing instrumentation, concise solos and dynamics. He was a greatly underrated pianist who had his own individual style. Although he only took one vocal on records in the 1920s ("Doctor Jazz"), Morton in his late-'30s recordings proved to be an effective vocalist. And he was a true character.

Jelly Roll Morton's pre-1923 activities are shrouded in legend. He started playing piano when he was ten, worked in the bordellos of Storyville while a teenager (for which some of his relatives disowned him) and by 1904 was traveling throughout the South. He spent time in other professions (as a gambler, pool player, vaudeville comedian and even a pimp) but always returned to music. The chances are good that in 1915 Morton had few competitors among pianists and he was an important transition figure between ragtime and early jazz. He played in Los Angeles from 1917-1922 and then moved to Chicago where, for the next six years, he was at his peak. Morton's 1923-24 recordings of piano solos introduced his style, repertoire and brilliance. Although his earliest band sides were quite primitive, his 1926-27 recordings for Victor with his Red Hot Peppers are among the most exciting of his career. With such sidemen as cornetist George Mitchell, Kid Ory or Gerald Reeves on trombone, clarinetists Omer Simeon, Barney Bigard, Darnell Howard or Johnny Dodds, occasionally Stomp Evans on C-melody, Johnny St. Cyr or Bud Scott on banjo, bassist John Lindsay and either Andrew Hilaire or Baby Dodds on drums, Morton had the perfect ensembles for his ideas. He also recorded some exciting trios with Johnny and Baby Dodds.

With the center of jazz shifting to New York by 1928, Morton relocated. His bragging ways unfortunately hurt his career and he was not able to always get the sidemen he wanted. His Victor recordings continued through 1930 and, although some of the performances are sloppy or erratic, there were also a few more classics. Among the musicians Morton was able to use on his New York records were trumpeters Ward Pinkett, Red Allen and Bubber Miley, trombonists Geechie Fields, Charles Irvis and J.C. Higginbotham, clarinetists Omer Simeon, Albert Nicholas and Barney Bigard, banjoist Lee Blair, guitarist Bernard Addison, Bill Benford on tuba, bassist Pops Foster and drummers Tommy Benford, Paul Barbarin and Zutty Singleton.

But with the rise of the Depression, Jelly Roll Morton drifted into obscurity. He had made few friends in New York, his music was considered old-fashioned and he did not have the temperament to work as a sideman. During 1931-37 his only appearance on records was on a little-known Wingy Manone date. He ended up playing in a Washington D.C. dive for patrons who had little idea of his contributions. Ironically Morton's "King Porter Stomp" became one of the most popular songs of the swing era, but few knew that he wrote it. However in 1938 Alan Lomax recorded him in an extensive and fascinating series of musical interviews for the Library of Congress. Morton's storytelling was colorful and his piano playing in generally fine form as he reminisced about old New Orleans and demonstrated the other piano styles of the era. A decade later the results would finally be released on albums.

Morton arrived in New York in 1939 determined to make a comeback. He did lead a few band sessions with such sidemen as Sidney Bechet, Red Allen and Albert Nicholas and recorded some wonderful solo sides but none of those were big sellers. In late 1940, an ailing Morton decided to head out to Los Angeles but, when he died at the age of 50, he seemed like an old man. Ironically his music soon became popular again as the New Orleans jazz revivalist movement caught fire and, if he had lived just a few more years, the chances are good that he would have been restored to his former prominence (as was Kid Ory).

Jelly Roll Morton's early piano solos and classic Victor recordings (along with nearly every record he made) have been reissued on CD.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/jellyrollmorton

Jelly Roll Morton

Jelly Roll Morton

The city of New Orleans has the distinction of being the ‘birthplace of jazz’ so its appropriate that in New Orleans in or around 1885 to 1890 would be born the self-proclaimed “inventor of jazz.”

Ferdinand Joseph Lemott (Lamothe) and his story is one of mystery, legend, genius, with an incredulous outcome, and original musical score.

Being considered a Creole in the Crescent City had its advantages in the fact that he was exposed to the fine arts and music as a child. He would undertake formal piano lessons with one Tony Jackson who was considered a wunderkind piano professor with exceptional musical ability, mirrored by the young student, who demonstrated an elevated level of talent, and the confidence to perform it.

We pick up on his trail as he moved to Biloxi, Mississippi to stay with his godmother, and so begins life on the road. He became a professional pianist at this time, playing in the brothels in Biloxi, then back to New Orleans where he played in the red light district of Storyville, learning and absorbing the styles of the famous ‘professors’, who were known for their vast repertoires and dazzling technique. This would prove to be an invaluable experience as he would also absorb classical, vaudevillian, theatrical, opera, marches, blues, stomps, ragtime, French and Spanish music. The Spanish would be a factor as he mentioned in coining the phrase “Latin tinge”. New Orleans was a conduit for the music that was coming out of Cuba since before the turn of the century, and the habaneras were all the rage in the early 1900’s.

Sometime along the way, he changed his name to Morton, and then added Jelly Roll as a stage name. The pianist known as Jelly Roll Morton went on a cross country tour that literally covered most of the U.S. He was quite the bon vivant, and pianist extraordinaire becoming very adept at ‘cutting heads’ where he would boldly challenge the local piano players, and wind up as the house pianist until he moved on, which from what we can gather, was continually. He can be verified as turning up in Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Colorado, Missouri, Houston, California, Texas, and in New York. We are privy here to a live witness account by the stride piano player James P. Johnson, who saw him play in New York in 1911, first describing his flamboyant dress and entry with two beautiful women, then his elaborate ritual at the piano before sitting down, striking a first sustained chord then “he’s gone”!

By the time he hit New York, he had already written quite a few tunes as “New Orleans Blues”, “Jelly Roll Blues”, “King Porter Stomp”, and “Georgia Swing”, all around 1905 to ’07. He then surfaced again in Los Angeles in 1917, and was running a hotel with his then wife Anita Gonzales. He played in Denver, traveled some more, until he showed up in Chicago in 1923.

In Chicago he wrote “Wolverine Blues” which was published by Melrose Publishing. He would go on to write many more songs for them and start a relationship that would turn out to be ill fated for him. He recorded solo and duets with King Oliver, and with the New Orleans Rhythm Kings for the Gennett label, in the “hot style’, of the period.

He did his legendary piano rolls recordings between ’23 and ’24. I would like to quote here from Ardie Wodehouse, an authority on Jelly Roll’s piano rolls. “These roll renditions combine the sound world of a jazz ensemble, the rhythmic complexities of African drumming, the contrapuntal intricacy of a Bach fugue, and the structural momentum of a classical sonata”.

In 1926 he recorded what would be his crowning achievement when he did sixteen sides for Victor as “Jelly Roll Morton and the Red Hot Peppers”. The band was a collection of top tier New Orleans musicians, and the arrangements were skilled, and complex, leaving plenty of room for individual soloing. He would prove to be a brilliant composer for hot ensembles, being able to capture and portray the musical feel of New Orleans. These sessions with the Red Hot Peppers still hold up today as innovative and significant in revealing his development of melody and harmony, control of tempo and dynamics and his pioneering in syncopation.

He moved to New York in 1928 and from then until ’30 he recorded fifty eight more sides for Victor. There would be a lot of different names of his bands under which his recordings were done. Most of these of course start with Jelly Roll Morton then we have Orchestra, Jazz Trio, Trio, Six/Seven, Incomparables, Kings of Jazz, Steamboat Four, Jazz Band, and Jazz Kids. There was also The Levee Serenaders, and the St. Louis Levee Band.

By 1930, there was to be a dramatic turnaround for Jelly Roll, Victor did not renew his contract, and his luck started to run out. He worked in small clubs and became something of a novelty act. The fad and focus at the time was the big bands and he was viewed as archaic. The music which helped to shape an American musical identity was slipping through the cracks into obscurity. He was receiving no royalty for his songs even though big names like Benny Goodman were covering his songs and getting rich. He scuffled around New York, and in 1935 decided to move to Washington D.C., where he became a bartender.

After a few more lean years, he was approached by musicologist Alan Lomax to record his songs and story for the Library of Congress. (Thank Goodness!!) This took place between May 23 and June 7, 1938. He narrated his own story accompanying himself on piano.

He moved back to New York that same year, and tried to fight for his song rights and royalties but to no avail. Melrose never sent him much anyway, and had included his own name as composer so Jelly Roll was essentially ripped off. He tried going to ASCAP but that was futile also and received just a fraction of what he should have.

He did some last sessions in Dec. 1939 with the New Orleans Jazzmen featuring Sidney Bechet, but was not in good health due to recent heart problems.

He moved back out to Los Angeles in in 1940, but was too ill to work or move around much. He died there in July 10, 1941.

This is just a short profile on a seminal figure in the history of jazz. I recommend people to go seek out his music and really listen to what he was doing. Jelly Roll Morton was light years ahead of everyone else in ability, knowledge, technique and confidence. He would reflect in his later lean years about his contribution, and believed he was deprived of a lot of the credit he felt he deserved. It’s a shame he did not get his due when he was alive, but he would be glad to know how his reputation and status as legend has grown and there’s a lot of us who consider him Mr. Jelly Lord, “inventor of jazz”.

Source: James Nadal

https://www.rockhall.com/inductees/jelly-roll-morton

Jelly Roll Morton

1998

A true giant of jazz.

He did not, as he claimed, invent jazz, but there’s no denying that he was a major influence on the genre. Jelly Roll Morton was a master composer, arranger and pianist who blended genres in an early form of jazz.

He did not, as he claimed, invent jazz, but there’s no denying that he was a major influence on the genre. Jelly Roll Morton was a master composer, arranger and pianist who blended genres in an early form of jazz.

Biography

https://www.neworleans.com/things-to-do/music/history-and-traditions/jelly-roll-morton/

Jelly Roll Morton

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jelly-Roll-Morton

Jelly Roll Morton

American musician

Alternative Title:

Ferdinand Joseph La Menthe

Jelly Roll Morton, byname of Ferdinand Joseph La Menthe, (born Oct. 20, 1890, New Orleans, La., U.S.—died July 10, 1941, Los Angeles, Calif.), American jazz composer and pianist who pioneered the use of prearranged, semiorchestrated effects in jazz-band performances.

Morton learned the piano as a child and from 1902 was a professional pianist in the bordellos of the Storyville district of New Orleans. He was one of the pioneer ragtime

piano players, but he would later invite scorn by claiming to have

“invented jazz in 1902.” He was, nevertheless, an important innovator in

the transition from early jazz to orchestral jazz that took place in

New Orleans about the turn of the century. About 1917 he moved west to California,

where he played in nightclubs until 1922. He made his recording debut

in 1923, and from 1926 to 1930 he made, with a group called Morton’s Red

Hot Peppers, a series of recordings that gained him a national

reputation. Morton’s music was more formal than the early Dixieland

jazz, though his arrangements only sketched parts and allowed for

improvisation. By the early 1930s, Morton’s fame had been overshadowed

by that of Louis Armstrong and other emerging innovators.

As

a jazz composer, Morton is best remembered for such pieces as “Black

Bottom Stomp,” “King Porter Stomp,” “Shoe Shiner’s Drag,” and “Dead Man

Blues.”

Jelly Roll Morton was the first great composer and piano player of

Jazz. He was a talented arranger who wrote special scores that took

advantage of the three-minute limitations of the 78 rpm records. But

more than all these things, he was a real character whose spirit shines

brightly through history, like his diamond studded smile. As a teenager

Jelly Roll Morton worked in the whorehouses of Storyville as a piano

player. From 1904 to 1917 Jelly Roll rambled around the South. He worked

as a gambler, pool shark, pimp, vaudeville comedian and as a pianist.

He was an important transitional figure between ragtime and jazz piano

styles. He played on the West Coast from 1917 to 1922 and then moved to

Chicago and where he hit his stride. Morton's 1923 and 1924 recordings

of piano solos for the Gennett label were very popular and influential.

He formed the band the Red Hot Peppers

and made a series of classic records for Victor. The recordings he made

in Chicago featured some of the best New Orleans sidemen like Kid Ory, Barney Bigard, Johnny Dodds, Johnny St. Cyr and Baby Dodds. Morton relocated to New York in 1928 and continued to record for Victor until 1930. His New York version of The Red Hot Peppers featured sidemen like Bubber Miley, Pops Foster and Zutty Singleton.

Like so many of the Hot Jazz musicians, the Depression was hard on

Jelly Roll. Hot Jazz was out of style. The public preferred the smoother

sounds of the big bands. He fell upon hard times after 1930 and even

lost the diamond he had in his front tooth, but ended up playing piano

in a dive bar in Washington D.C. In 1938 Alan Lomax recorded him in

for series of interviews about early Jazz for the Library of Congress,

but it wasn't until a decade later that these interviews were released

to the public. Jelly Roll died just before the Dixieland revival rescued

so many of his peers from musical obscurity. He blamed his declining

health on a voodoo spell.

For more information about Jelly Roll Morton's life and music you are encouraged to visit Monrovia Sound Studio's Jelly Roll Morton Page

For more information about Jelly Roll Morton's life and music you are encouraged to visit Monrovia Sound Studio's Jelly Roll Morton Page