Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

TEDDY WILSON

(July 14-20)

GEORGE WALKER

(July 21-27)

BILLY STRAYHORN

(July 28-August 3)

LEROY JENKINS

(August 4-10)

LAURYN HILL

(August 11-17)

JOHN HICKS

(August 18-24)

(August 18-24)

ANTHONY DAVIS

(August 25-31)

RON MILES

(September 1-7)

RON MILES

(September 1-7)

A TRIBE CALLED QUEST

(September 8-14)

NNENNA FREELON

(September 15-21)

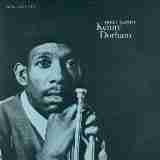

KENNY DORHAM

(September 22-28)

KENNY DORHAM

(September 22-28)

FATS WALLER

(September 29-October 5)https://www.allmusic.com/artist/kenny-dorham-mn0000768027/biography

Kenny Dorham

(1924-1972)

Artist Biography by Ron Wynn

Kenny Dorham

had a deeply moving, pure tone on trumpet; his sound was clear, sharp,

and piercing, especially during ballads. He could spin out phrases and

lines, but when he slowly and sweetly played the melody it was an

evocative event. Dorham

was a gifted all-round trumpeter, but seldom showcased his complete

skills, preferring an understated, subtle approach. Unfortunately, he

never received much publicity, and though a highly intelligent,

thoughtful individual who wrote insightful commentary on jazz, he's

little more than a footnote to many fans.

Dorham studied and played trumpet, tenor sax, and piano. He was a bandmember in high school and college; a college bandmate was Wild Bill Davis. Dorham started during the swing era, but was recruited by Dizzy Gillespie and Billy Eckstine to join their bands in the mid-'40s. He even sang blues with Gillespie's band. He recorded with the Be Bop Boys on Savoy in 1946. After short periods with Lionel Hampton and Mercer Ellington, Dorham joined Charlie Parker's

group in 1948, staying there until 1949. He did sessions in New York

during the early and mid-'50s, making his recording debut as a leader on

Charles Mingus and Max Roach's Debut label in 1953. He then cut Afro-Cuban for Blue Note with Cecil Payne, Hank Mobley, and Horace Silver in 1955.

Dorham was a founding member of Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers in 1954, and also led a short-lived similar band, the Jazz Prophets. Dorham played on the soundtrack of A Star Is Born in 1954, then spent two years with Max Roach from 1956 to 1958. There were dates for Riverside in the late '50s with Paul Chambers, Tommy Flanagan, and Art Taylor,

plus other sessions with ABC-Paramount, three volumes for Blue Note

done live at the Cafe Bohemia, and an intriguing but uneven session with

John Coltrane and Cecil Taylor, Coltrane Time, in 1958.

Dorham

taught at the Lenox School of Jazz in 1958 and 1959, and wrote scores

for the films Les Liaisons Dangereuses and Un Témoin dans la Ville in

1959. During the mid-'60s, he co-led a band with tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson that was shamefully neglected. There were such classic Blue Note releases as Whistle Stop, Una Mas, and Trumpet Toccata. Dorham made one album for Cadet in 1970, Kenny Dorham Sextet, with Muhal Richard Abrams. He died in 1972. Several of his Blue Note albums have been reissued, while his Prestige and Riverside

dates have come out in sporadic fashion, some in two-record samplers.

Other material for Pacific Jazz, United Artists, Steeplechase, Xanadu,

and Time isn't as widely available.

http://kennydorham.jazzgiants.net/biography/

Biography

McKinley

Howard “Kenny” Dorham was born on August 30, 1924 in Fairfield, Texas

and passed away on December 5, 1972 in New York City at the age of 48.

Born into a musical family, Dorham began playing piano at age seven

and switched to trumpet while attending Anderson High School in Austin.

Music was not Dorham’s only hobby as a teenager; he spent much of his

time in the boxing ring as a member of the school boxing team.

Dorham briefly attended Wiley College in Marshall, Texas, where he

studied chemistry and physics while performing in the dance band

alongside musicians such as trumpeter “Wild” Bill Davison, saxophonist

Harold Land, and drummer Roy Porter. It was in this group that Dorham

first began honing his arranging and compositional skills.

Dorham was drafted into the Army in 1942 and joined their boxing

team. In 1943 after his discharge, he worked with the orchestra of

trumpeter Russell Jacquet, the brother of saxophonist “Illinois”

Jacquet, in Houston before joining Frank Humphries’ band in 1944.

In 1946, Dorham got his first major gigs, joining the trumpet section

in Dizzy Gillespie’s original big band and then replacing Fats Navarro

in Billy Eckstine’s band at Diz’s recommendation.

Dorham was now associating with the most modern players on the jazz

scene, recording in 1946 and 1947 with the likes of drummer Kenny

Clarke, pianist Bud Powell, saxophonist Sonny Stitt, and drummer Art

Blakey. He also played in the big bands of Lionel Hampton and Mercer

Ellington. Dorham made his mark as an arranger as well, arranging charts

for Lucky Millander (“Okay for Baby”), Benny Carter, Cootie Williams

(“Malibu”), and ghosting arrangements for Gil Fuller.

In 1948, he studied composition and arranging at the Gotham School of

Music under the G.I. Bill. In December 1948, Dorham got his first big

break as Miles Davis recommended him as his replacement in Charlie

Parker’s quintet. Dorham performed for the first time with Parker on

Christmas Eve at the Royal Roost in Manhattan, with pianist Al Haig,

bassist Tommy Potter, and Max Roach on drums. The gig, which was

recorded, included a festive take on “White Christmas.”

Dorham stayed with Parker into 1949, recording on one of the

altoist’s most solid Verve sessions, which produced the tracks

“Passport,” “Visa,” “Segment,” and “Cardboard.” Following their return

from the Paris Jazz Fair at the end of May 1949, Dorham was replaced by

Red Rodney. He returned to Parker’s group intermittently as a

replacement over the next few years, notably on March 4th, 1955 at

Birdland: Parker’s final performance before his untimely death seven

days later.

Finding it difficult to make a living as a jazz trumpeter, Dorham

moved to California from 1950 to 1952, where he worked day jobs. He then

moved back east, settled in New York and began freelancing, working

with the likes of Bud Powell, Sonny Stitt, and Mary Lou Williams. He

recorded with Thelonious Monk on May 30, 1952, on tracks which ended up

on Monk’s release, Genius of Modern Music Volume 2. He led his

first session as a leader on December 15th,1953, with Jimmy Heath on

saxophone, Walter Bishop on piano, Percy Heath on bass, and drummer

Kenny Clarke, which was released by Debut as Kenny Dorham Quintet.

Work followed with altoist Lou Donaldson and tenorman Sonny Rollins

before Dorham replaced Clifford Brown in Horace Silver and Art Blakey’s

Jazz Messengers, recording their co-led hard-bop classic Horace Silver and the Jazz Messengers album for Blue Note in November 1954 and February 1955.

Dorham’s

fleet lyricism is showcased on “Hankerin’,” his running style and taste

for melodic logic on “The Preacher,” and he blows some of his best

blues choruses on Silver’s funky classic “Doodlin.’” Dorham also plays

spiritedly on The Jazz Messengers at Café Bohemia Vols. 1-3, which was recorded on November 23rd, 1955.

Dorham also recorded what many believe was his greatest album for Blue Note in 1955, Afro-Cuban. Recorded

in two sessions, on January 30, 1955 with a sextet, and March 29,1955

with a nonet, this album showcases Dorham’s interest in combining Latin

music with jazz and his distinct compositional and arranging skills. It

also features a who’s who of Blue Note hard-boppers—Hank Mobley, Cecil

Payne, J.J. Johnson, Art Blakey, Horace Silver, Percy Heath and Oscar

Pettiford. “La Villa,” taken from the sextet session, features fine

blowing by all.

Dorham led a short-lived group called the Jazz Prophets in 1956 which

featured J.R. Montrose on tenor sax, Sam Jones on bass, Arthur Edgehill

on drums, and Dick Katz on piano, who was later replaced by Bobby

Timmons. The group recorded for Blue Note at the Café Bohemia and three

albums were released under Dorham’s name:‘Round About Midnight at the Café Bohemia Vols. 1-3.

Dorham also recorded in 1956 with the likes of Tadd Dameron, Phil

Woods, Cecil Payne, Matthew Gee, Hank Mobley, Sonny Rollins, Gil Melle,

and Ernie Henry.

After Clifford Brown’s tragic death in a car accident in September of

1956, drummer Max Roach called upon Dorham to replace the great

trumpeter in his quintet. Dorham stayed with Roach for nearly two years,

and is heard on Jazz in 3/4 Time (which features the trumpeter

alongside Sonny Rollins on “Blues Waltz” and “Lover,” Max Roach + Four, Max Roach 4 Plays Charlie Parker, and Max.

Dorham’s own Jazz Contrasts was recorded in 1957, teaming him

with Roach frontline mate Sonny Rollins on “I’ll Remember April” and

also accompanied on half of the tracks by harpist Betty Glamann. After

the Roach group disbanded, Dorham recorded some memorable albums as a

leader in 1958 and 1959, including his pristine Quiet Kenny, which featured “Blue Spring Shuffle,” and even a vocal album, Kenny Dorham Sings and Plays: This Is the Moment.

Dorham also performed on one of the more unusual albums of the 1950s

alongside John Coltrane and the avant-gardist Cecil Taylor, who forces

his uncompromising, vigorous piano playing into an otherwise

hard-bop-oriented affair. The uneven album would be ultimately released

on Blue Note as Coltrane Time in 1962. Other session work included dates with Abbey Lincoln, Betty Carter, Jackie McLean, Oliver Nelson, and Eric Dolphy.

In 1961, Dorham recorded the fantastic album Whistle Stop for

Blue Note. In 1963, he began a prolific partnership with tenorman Joe

Henderson. The trumpeter was an early proponent of the young tenorist,

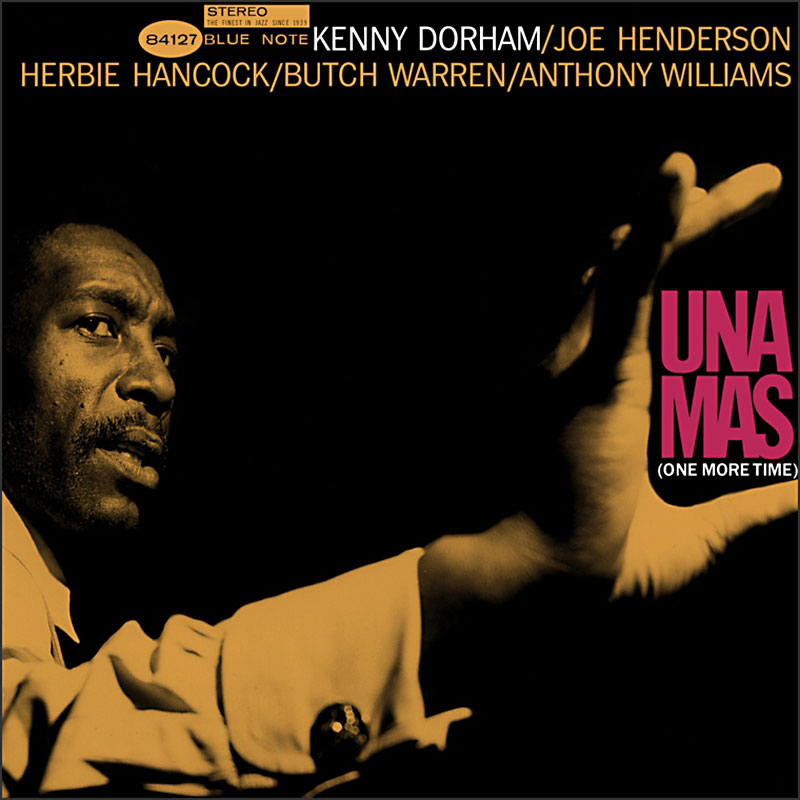

and his brilliant Una Mas was Henderson’s first recording

session. Dorham was now associating with musicians over ten years his

junior, and their forward-thinking ways pushed the trumpeter into

greater, more daring territory. In particular, Henderson’s harmonically

adventurous improvisations forced Dorham to intensify his own playing

and include more open modal structures within his compositions.

“Una Mas” featured Herbie Hancock, Butch Warren, and Tony Williams in

the rhythm section, backing Dorham as he blows one of his more

aggressive and bold statements on record. Dorham’s most lasting

contribution to the jazz canon, “Blue Bossa,” was the opening track on

Henderson’s first album as a leader, Page One. Henderson’s Our Thing followed in 1963, which featured a swinging title track, and his In ‘n Out was recorded in 1964.

The intrepid pianist Andrew Hill requested both Henderson and

Dorham’s services on his breakout, avant-garde Blue Note masterpiece Point of Departure in

1964. Now nearly forty years old, Dorham is audibly pushing himself in

the company of these younger progressives, deeply investigating the

possibilities inside Hill’s ambiguously open harmonies with intense

arpeggios, repeated intervals and contrasting lyrical flurries. Listen

to his edgy improvisation on the fiery “Refuge.”

Dorham recorded his final session as a leader, Trumpet Toccata,

later that year. He became less active into the later 1960s and as he

again found it difficult to make a living playing jazz trumpet; he found

work at times at a sugar refinery, the post office, and medical plants.

He recorded with Cedar Walton, Toshiko Akiyoshi, Barry Harris, and

Clifford Jordan in the late 1960s while also writing record reviews for Down Beat magazine.

Dorham continued to study music at New York University, was a

consultant for the Harlem Youth Act anti-poverty program, and held a

position on the board of the of the New York Neophonic Orchestra. By

1970, his health began to seriously deteriorate and a kidney ailment

forced him into fifteen hours of weekly dialysis at a local hospital. He

died on December 5, 1972 of kidney failure.

Kenny Dorham

Kenny Dorham

Overshadowed for most of his career by the likes of Dizzy Gillespie,

Fats Navarro, Miles Davis, Clifford Brown, and Lee Morgan, Kenny

Dorham's abilities as a composer and unique voice as an advanced bop

trumpet player are underrated to this day.

McKinley Howard Dorham

was born on August 30, 1924 on a ranch called Post Oak, near Fairfield,

Texas. He attended Anderson High School in Austin, where he began

teaching himself to play piano and trumpet, and spending much of his

time on the school boxing team. He later enrolled at Wiley College in

Marshall, Texas, studying chemistry and minoring in physics. During this

time he experimented with arranging, writing for the stage band, where

he met such players as Wild Bill Davis, Harold Land, and Roy Porter.

He was drafted into the army in 1942 (spending some time with the army boxing team) and was discharged about a year later.

In

late 1943 he joined the Russell Jacquet orchestra in Houston, and he

spent much of 1944 playing the band of Frank Humphries. By 1945, Dorham

had gained positions with Dizzy Gillespie's short-lived first big band,

and then replaced Fats Navarro in Billy Eckstine's orchestra. In 1946 he

recorded with the Be Bop Boys (aka the 52nd Street Boys, including Fats

Navarro), and spent time playing in the bands of Lionel Hampton and

Mercer Ellington.

During this time, Dorham continued to compose

and arrange (he arranged “Okay for Baby” for Lucky Millinder and Benny

Carter, and “Malibu” for Cootie Williams), ghosting arrangements for

Walter 'Gil' Fuller which were sold to several name big bands, including

Harry James, Jimmy Dorsey, and Gene Krupa.

In 1948, Dorham

studied composition and arranging at the Gotham School of Music under

the G.I. Bill. On Christmas Eve of that year, Dorham performed for the

first time as replacement for Miles Davis in the Charlie Parker quintet,

where he would play for about a year (Davis had recommended Dorham for

the job), including an appearance at the 1949 Paris Jazz Fair.

After

a two-year hiatus starting in 1950, during which Dorham lived and

worked day jobs in California, he settled in New York City and began a

busy career as a free-lance musician, perorming with players such as Bud

Powell, Sonny Stitt, Thelonious Monk, and Mary Lou Williams. In 1952

Dorham recorded with Monk and in late 1953 led his first recording as a

leader, a 10-inch record on the Debut label.

In 1954, Dorham

replaced Clifford Brown with Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers when Brown

left the group to form the legendary Brown/Roach quintet, and that same

year formed a band called the Jazz Prophets which recorded for Blue

Note. Dorham left Blakey's band in late 1955, and shortly found work

playing with the Birdland All-Stars (along with Conte Candoli, Phil

Woods, and Al Cohn) and recording with the likes of Tadd Dameron, Phil

Woods, Cecil Payne, Matthew Gee, Hank Mobley, and Gil Melle.

In

August, 1956, Dorham recorded some interesting material for Riverside

with alto saxophonist Ernie Henry. Upon Clifford Brown's untimely death

in September of that year, Dorham replaced him in Roach's group, an

association which would produce several EmArcy recordings and last

almost two years.

Once Roach disbanded the group in 1958, Dorham

led several groups of his own, recording for Riverside (including a

vocal album! and the notable Quiet Kenny), New Jazz, and Time.

In

1961 began a fruitful period recording again with Blue Note records,

where he recorded some of his most significant albums, especially with

up-and-comers Joe Henderson, Herbie Hancock, and Tony Williams.

By

the mid-1960s, economic circumstances made it impossible for Dorham to

maintain his group with Henderson, and he was forced to find employment

outside of music (this time working for the post office). He still

studied music (at the NYU School of Music) and wrote record reviews for

Down Beat magazine, but by the early 1970s his health began to

deteriorate; development of a kidney ailment forced him to make regular

hospital trips for 15 hours a week on dialysis. He passed away at the

age of 48.

Source: Jeff Helgesen

This

week, a secondary figure in jazz is receiving a primary re-evaluation.

Kenny Dorham, who died of kidney disease in 1972 at the age of 48, was a

trumpet player of authority and great style; he moved from his early

days in the be-bop era to the 1960's progressions of the music

gracefully, without showing the permanent markings of his youth.

The

clean, soft definition of his tone, and his writing on albums like

''Una Mas'' and ''Quiet Kenny'' -- and such commonly played tunes as

''Blue Bossa'' -- have influenced many contemporary players; he was a

composer whose tunes are still played, a pianist, a singer and possibly

the most famous jazz musician to write a considerable amount of jazz

criticism, for Downbeat magazine, for which he was a staff reviewer in

the mid-1960's. But for many reasons -- he wasn't a leading force of any

particular school and some of his most memorable tunes appear on other

people's albums -- he has been a little difficult to canonize.

That's

where Don Sickler, the trumpeter, arranger, producer and music

publisher, steps in. The pro forma reason for presenting six days of

Dorham's music at the Jazz Standard, through Sunday night, is that

Dorham would have been 75 this year. The real reason is that Dorham's

music is still underplayed and underappreciated. Mr. Sickler is a

low-profile crusader: where exhaustive tasks concerning the modern jazz

of the 1950's and 60's are being suggested he is often first in line,

because his vested interests lie in both performance and preservation.

Through his company, Third Floor Music, he has published arrangements of

Dorham's music for the educational field, and has convinced band

directors and band leaders to play some of it.

Mr.

Sickler is not famous enough to put his own career as a musician ahead

of his behind-the-scenes work, and band leading does not suit him

constitutionally. ''I was never one of those guys carrying my horn

around to clubs and trying to sit in,'' he said recently. ''I'm

basically sitting at home and I'm a workaholic, doing arrangements,

producing records.''

Mr.

Sickler did not know Dorham, and saw him play only a few times. Mr.

Sickler completed his music degree at Manhattan School of Music in 1970

and he played at Broadway shows, weddings, bar mitzvahs and with jazz

and rhythm-and-blues bands. He was soon working in the music business

for United Artists, as production manager for the print division in

their publishing arm, and doing a lot of transcribing himself; that's

when he had his epiphany about Dorham's work. ''I was always attracted

to his music,'' said Mr. Sickler. ''And I didn't really know why until I

started transcribing it. I realized the intricacies he put in for the

rhythm section.''

''With

Kenny Dorham's music, you can't just take a lead sheet,'' Mr. Sickler

said of a skeletal score showing only the melody and chord changes of a

piece, ''and hand it out to the bass player, the pianist and the

drummer, expecting to get what he did on the records.''

''Once

he started getting involved with Hank Mobley and the Jazz Messengers,

his rhythm-section approach became very unique,'' he said. ''Every

player has his own little role, and you really have to write out parts

for each to make it work. Most guys still try to take Dorham's stuff,

make a lead sheet and hand it out to everybody, and wonder why they

can't get it to work.''

Mr.

Sickler believes that Dorham's compositional talent flowed from the

great rhythm sections he worked with. ''Dorham always worked with the

great drummers: Art Blakey, Kenny Clarke, Max Roach,'' he said. ''The

drummers are the ones that define the music, no matter what anybody

says, and Kenny had the ability to know how to write for the drummers,

to get the drummers to play their music. You listen to tunes like

'Minor's Holiday' and you know that's written for Blakey.''

Accordingly,

this week at the Jazz Standard the rhythm section includes two

musicians who knew Dorham and performed with him: the bassist Ron Carter

and the pianist Ronnie Mathews as well as a jazz scholar, the drummer

Kenny Washington, who has worked extensively as a disc jockey on the

jazz radio station WBGO (88.3-FM).

Tonight's

program will focus on the recordings Dorham made with the saxophonist

Joe Henderson. As he has done through the week, Mr. Sickler is to play

the trumpet and the young tenor saxophonist Mark Shim is to play the

saxophone.

Tomorrow

night's program, ''As I Live and Breathe,'' creates a kind of Kenny

Dorham songbook: vocalized versions of his instrumental tunes, songs he

sang on one record he made for Riverside in the late 50's with his

light, swooping blues voice, as well as two originals he wrote and never

recorded; Roberta Gambarini, an Italian vocalist who was a finalist in

last year's Thelonious Monk vocal competition, is to sing.

Sunday's

concert, ''Blues in Be-Bop,'' honors Charlie Parker's birthday, so a

set of tunes that Dorham performed with Parker in the mid-40's will fill

the program; the saxophonist Ralph Moore is to be a guest.

A Celebration

The

Kenny Dorham 75th-birthday celebration is at the Jazz Standard, 116

East 27th Street, Manhattan. Sets through Sunday are at 8 and 10:30 P.M.

The cover charge is $20 tonight and tomorrow, $15 on Sunday; there is

also a $10 minimum all evenings. Information: (212) 576-2232.

Correction: August 31, 1999

An article in Weekend on Friday about the trumpeter Kenny Dorham

misstated the name of the company owned by the trumpeter, arranger and

music producer Don Sickler, which has published arrangements of Dorham's

music. It is Second Floor Music, not Third Floor Music.

A version of this review appears in print on August 27, 1999, on Page E00027 of the National edition with the headline: Kenny Dorham, From Be-Bop On.

In Miles Davis' autobiography, one of the mightiest forces in music, let alone jazz, recounts a 1956 winter date at Cafe Bohemia, a onetime Greenwich Village staple. The trumpeter hadn't yet banished saxophonist John Coltrane and all-time drummer Philly Joe Jones from his short-lived "first great quintet" despite both addicts having become liabilities. Davis' critical confirmation from the four-album Prestige Records run with the quintet and his indomitable Columbia Records debut, 'Round About Midnight, remained imminent.

His friend Dorham asked if he could sit in. Davis rarely ceded the stage to anyone, but he loved and respected the Texas-born trumpeter, whom he recognized as a peer. In the only anecdote of its kind in the book, the bandleader recalls working over the packed venue before introducing his guest. Dorham swelled in his trademark romantic elegance to the chagrin of the infamously prideful Davis, who quickly realized he was being buried alive.

In search of solace afterward, Davis asked saxophonist Jackie McLean how he had sounded: "[Jackie] looked me straight in the eye and said, 'Miles, tonight Kenny is playing so beautiful, you sound like an imitation of yourself.'"

Davis gathered his possessions angrily, including his self-esteem, and walked out without saying a word. He glanced over at his compatriot, who he remembered "had this shit-eating grin on his face and was walking like he was 10 feet tall."

"[Dorham] knew what had gone down – even if people in the audience didn't," wrote Davis about his defeat, residual steam still evident in 1989. "He knew, and I knew what had happened."

Dorham wanted the audience to know. He had come all this way to tell them before it was too late.

McKinley and Minnie Dorham (née Manning), a sharecropper and homemaker respectively, had four children in all: Eva Lois Manning, Kenny, Cloteat, and Joel, who would become a noted Bay Area jazz musician. "Fragments" begins by reminiscing about the sounds of the "big Southwest" during its author's youth in Post Oak, an unincorporated community three miles south of Fairfield in central Freestone County. Aspiring to either a "top cowhand" or "a hobo" because they train-hitched and sang songs of the frontier, Dorham might have craved the land's inherent freedom as an antidote to the sick norms of Jim Crow Texas.

Thumping out boogie-woogie piano at age 7, he picked up the trumpet some three years later. Dorham asserts that his sister recognized, and ostensibly spoke into existence, her little brother's prodigious talent. She bought him his first trumpet at age 15, a silver Conn model.

By 1936, the family settled in Austin, east of then-East Avenue (now I-35) with the bulk of the city's black families. Dating back to at least the 1940 U.S. Census, 1218 E. 12th remained the Dorham homestead through Minnie's death in 1992. Attending high school at the then-all-black L.C. Anderson, the young horn enthusiast played in the Yellow Jackets marching band under the tutelage of legendary director B.L. Joyce, who chastised him for freelancing more than once.

After school, Dorham jammed at brothers Roy and Alvin Patterson's home at 1709 Washington Avenue. In tow were trombonist Buford Banks, Austin jazz great Martin Banks' father, and trumpeters Paris Jones, Warner Ross, and Gil Askey, the latter of whom gained distinction as a Motown arranger. Starting a prevailing theme throughout his career, Dorham deferred to Hermie Edwards, then Austin's pre-eminent trumpeter.

Following a brief stop at Wiley College, he was drafted into the Army

in 1942 and excelled on the boxing team. After his discharge a year

later, he spent a short stint in California, playing in Russell

Jacquet's big band. Stopping over in Houston, Dorham then made his way

to New York City in 1944, a meteor in search of Dizzy Gillespie.

Career finally off to a running start, he demonstrated first-rate attributes within the big bands of Lionel Hampton, Mercer Ellington, then Gillespie. He soon replaced cherub-faced dynamo Fats Navarro in Billy Eckstine's band. Nevertheless, inconsistencies plagued Dorham, and it showed in early recordings with Navarro.

"Fats had a big, beautiful, round sound, and K.D. had a pretty squeaky sound at that time. We're talking about in the late Forties," explains trumpeter and friend Jimmy Owens. "As time went on, K.D.'s sound became sweeter. When he found that warmth in his sound, he became noticed by the public."

During 1946-47, Dorham freelanced with pianist Bud Powell, saxophonist Sonny Stitt, and charismatic drummer Art Blakey, with whom he'd have less fortunate associations. In 1948, he studied composition at the now-defunct Gotham School of Music, using his G.I. Bill benefits.

He got his first significant break in December 1948, joining sax deity Charlie Parker's quintet at the behest of group predecessor Miles Davis. By his admission, the 22-year-old Davis, at times, could be eaten up by Parker's speed. Dorham quickly presented remarkable maturity – and an ability to keep pace with Bird.

By age 25, the Lone Star blower broadened his tone, consistently rising to Bird's level, whether recording at New York hot spot the Roost or glowing at Paris' first international jazz festival in 1949. Flaunting a unique capacity to speak and sing with his instrument, versus running scales vertically, Dorham added considerable subtlety and discipline to any session.

During his year in Parker's group, an ultimate proving ground, and then subsequent work with pianist Thelonious Monk, Dorham settled neatly into his career-defining melodic and nuanced comportment. Saxophonist Jimmy Heath, now 91, calls him a "romantic."

"He was on that level with Dizzy, on the level with these other guys," says renowned and now retired saxman Sonny Rollins from his home in New York. "And he had a unique sound. Once you heard it, you knew, 'Oh yeah, that's Kenny Dorham.'"

"When you hear the way he plays, you know it's Kenny," echoes avant-garde pianist Steve Kuhn, who debuted on 1960 Dorham LP Jazz Contemporary.

Both Rollins, 88, and fellow saxophone great Lou Donaldson, 91, state with emphasis that Dorham's gifts equaled those of Miles Davis. Some will cry hyperbole, and indeed there's calculus necessary for a full appraisal, but there's recording greatness, and then there's greatness in performance. Kenny Dorham produced terrific, all-time moments on dozens of records, but he's even more respected as a live player.

Nearly everyone interviewed herein and a dozen more made explicit

mention of the "K.D. turnback," or turnaround, an improvisation

technique the trumpeter learned from sharpening his sword against

Navarro and Davis. A turnaround exists at the end of a tune, where

instead of carrying through a chord in an eight-bar frame, the player

applies two measures flipping back to the start. For the listener, it

spurs anticipation with a minor-major note combination as the song dives

back into the meatier parts – perfect for Dorham, who lived in longing

gradients of minor chords.

Dorham capably blended his older influences with newer bebop and hard bop sensibilities. He also played tenor sax, which influenced his stronger horn within the middle registers.

"His phrasing is more like a saxophone player, in the way a tenor phrases," says Brian Lynch, a Grammy Award-winning trumpeter. "It was a darker, a little bit less resonant sound, but adapted to the kind of expressiveness that he put into melodies."

"Historically, he's interesting because he was a modern bebop artist, yet he used traditional techniques and devices, like flutter tonguing," offers Dave Oliphant, poet and author of KD: A Jazz Biography. "There's no doubt about [his greatness], and he was the equal of Dizzy Gillespie."

1955's spectacular Blue Note debut Afro-Cuban and 1959's Quiet Kenny established Dorham as a force in composition, but his sophisticated 1961 classic Whistle Stop – the bluesy, Southwestern-tinged bop album he was destined to make – evened the recording competition with his peers despite not making him a household name. All three albums exhibited a continually developing bandleader, particularly with his layered arrangements.

"Most guys then, they would hand a lead sheet to the guys, and the rhythm section did what they wanted to do," explains Don Sickler, publisher of Dorham's catalog, on his purposeful compositional skills. "Kenny wrote a specific part for the piano player to play that was different than what the bass player played, and that was different from what the drummer would play."

And yet, though he enjoyed unending respect from his peers, Dorham believed he wasn't being heard by the listening public to the point of exasperation. He desired the elusive broad appeal. Kuhn, unprompted, says Dorham resented the absence of attention yielded to Davis or Gillespie, two stubborn alpha male types willing to deviate from bebop and hard bop purity out of survival.

Neither an assertive man nor one supported by aggressive management, Dorham never learned to "play the game," to leverage his ability in navigating the music industry's choppy waters. The consummate creative, he believed overwhelming talent alone generated all avenues. Enterprising squeaky wheel, Dorham was not.

"Kenny just never seemed to have that promotion, and that could be because he was too sweet a guy," says Rollins.

According to the liner notes of his 1964 forward-leaning opus, Point Of Departure, pianist Andrew Hill saw Dorham as the most underrated player around.

"His problem is that he's so nice, and people seem to associate greatness with meanness or bitterness," wrote Hill. "In this business, you have to create some angry or tough image of yourself to be accepted, and therefore, too many people take Kenny for granted."

Horn in hand, Dorham didn't necessarily get out of his own way. When big names began migrating left of the needle, as Coltrane and Davis eventually had, Dorham tended to maintain bop strictness. Whereas he likely could've pursued numerous opportunities doing so-called "free jazz," and later fusion, Dorham showed only occasional interest, including his essential date with Hill.

Additionally, away from performances and studio sessions, Dorham's love of the lifestyle often undercut whatever efforts he would have pursued to further his career. Chief amongst his issues remained a nasty heroin addiction he'd been carrying around since the late Forties.

"He was the one that you could run to, sit on his lap, and have a father-daughter conversation," recalls Keturah. "He had a wonderful personality, very handsome, well dressed. He wasn't a mean father. He didn't whip us, beat us, or anything like that."

"My father had a wonderful laugh; I do remember that," says Evette. "But often, he was more on the serious side. People mistake that sometimes for being angry, and it's not. He was always thinking about what he was doing, and the next thing after that."

The paterfamilias' warm, if utilitarian, marriage with his wife, now Rubina Robinson, proved a little less pronounced. A vague separation in 1964 isn't entirely defined by the daughters, either in reasoning or resolution. It's believed he left his family, but family members maintain the discovery of various details in his life occurred only after his passing.

Through his 40s, Dorham existed perpetually short: on time,

maintaining obligations to himself, and upkeep of a family that needed

him. Evette recalls going out in search of her father, who regularly

relocated with various women, wishing for fatherly intangibles he

couldn't offer.

"There were some moments when I thought, especially when I started getting a little bit older, it would have been great if my dad was here, or I could ask him to do this thing, or I could talk to him right now," she laments. "I'd call, and I'd wait for him to get back to me, or I'd go find him."

By the late Sixties, Dorham worked day jobs for sustenance – food and sometimes heroin. The addiction, picked up during his sessions with Blakey, Navarro, Hank Mobley, and others, wreaked havoc on his organs. With a wink and a slow nod, Dorham hinted at the dependence in "Fragments."

"Of course, we all belonged to Local 802, but I'm speaking of union in union, or our union."

This destructive "union," accompanied by high blood pressure, destroyed his progressively overtaxed renal system.

Not that Dorham wasn't making an effort. He became a student at New York University in the late Sixties and instructed in various youth music programs. He also wrote reviews for Downbeat. In heartbreaking logic connected to the resurrection of his worth, Dorham told former classmate and trumpeter Paul Ayick he wanted to become an educator, to get his family back together.

Ayick, who also took lessons from Dorham, describes being over at Dorham's residence when a handful of possibly hostile men arrived: "They went up to the bedroom for 10 minutes and when they came out, they were all, y'know, changed."

Like others contacted, Ayick softens Dorham's penchant for self-destructiveness.

"I don't think it was a thing he had to do all the time in those days," he says. "I think it was something he did now and then."

While Dorham's fixes eventually broke down his body, a fickle audience broke down his resolve.

His seemingly minimalist horn matured to the point of resolute

greatness, openly challenging Davis and Freddie Hubbard's pomp and pose

with increasingly cerebral approaches, negotiating each note with a

surgeon's precision. Alternating legato runs, flutters, and tonguing

techniques, Dorham exhibited wistful romance with each phrase. Where Lee

Morgan, Herbie Hancock, and Wayne Shorter were amongst jazz's vanguard,

Dorham existed as living orthodoxy, its stable underpinning.

Even so, the trend of missing due recognition continued through 1963's exceptional, Brazilian-influenced Una Mas and 1964's Trompeta Toccata, both featuring the young Henderson. In the liner notes to the former LP, Dorham addresses his elephant in the room:

"All I can say is that if it's going to happen, it'll happen. But it's going to have to happen within a reasonable time. After all, I'll soon be into my 25th year on the trumpet."

Concurrently with his bandleading output, he turned in tremendous work on his protégé Henderson's first few Blue Note recordings, specifically singular 1963 debut Page One and Our Thing the following year. On the former, "Blue Bossa" maintains great intrigue. The composition itself is an all-time standard, but despite his closeness with Henderson, one wonders why Dorham didn't keep the instant classic for himself.

In fact, a great deal of Dorham's best efforts reside on other artists' discography, credited or not.

"His problem is that he's so nice."

Do-or-die time was at hand, believed Dorham at age 40. Clock hard wound, he appears to have accepted the grim reading of its hands. He concluded the audience wasn't listening.

Not helping matters were breakthroughs by young guns like Lee Morgan, who crossed over with 1964's The Sidewinder, which featured Henderson. The massive hit title track was initially recorded as filler. Dorham's Trompeta Toccata in September 1964 marked the swift conclusion of what should've been his prolific prime stage as a bandleader.

The Texan occasionally produced ardent moments as a sideman, as on Cecil Payne's impressive 1973 release Zodiac. Effectually, however, the 10-foot colossus Miles Davis remembered quickly shrank. He performed and recorded less, year by year, following 1964, the year he separated from his wife and children.

By the end of the decade, his existence depended on dialysis three days a week.

In hindsight, what makes Dorham's short memoir for Downbeat,

"Fragments of an Autobiography," disheartening is that it represents

the truncated chronicle of a musician awaiting his fast-approaching

departure. As an addendum to his music, he documented significant

minutes that had mattered, but the magazine's then-editor Dan

Morgenstern believes the text belonged to a fuller, future book Dorham

wished to write.

That's what Dorham told former Boston Globe critic Bob Blumenthal, then a reporter at the now-defunct Boston Phoenix, at Old West Church. According to horn blower Jimmy Owens, roughly three weeks earlier saxophonist Cecil Payne told Dorham he could receive funds for blood transfusions from his musicians' union. The latter replied that his union card had expired.

The week leading up to Dorham's death on Tuesday, December 5, 1972, he told his young friend Owens to catch him after an appointment. Owens wanted to interview his hero about his health problems and causes. Dorham told him to call after dialysis, because he'd feel stronger. This happened twice. The interview never happened.

Reedman Jimmy Heath says Dorham had made up his mind about dialysis.

"He decided not to go," reveals Heath. "He'd had enough of it, and he said he wasn't going. His lady friend told him, she said, 'Man, if you don't go, K.D., then you can't stay. You're gonna die, man.' He got tired of that dialysis thing, and he split."

Both Heath and Owens agree that their friend knew his fate. Many things had not cut Dorham's way. He would make sure the last thing would.

Dorham miraculously arrived at his own benefit at Old West Church in Boston on Sunday, December 3, an event created with the help of trumpeter Claudio Roditi and associate minister/player Mark Harvey.

"It was quite remarkable because he was not in good health," says Harvey, now a Ph.D. holding senior lecturer status at MIT. "We started talking trumpet, and he said, 'Well, I have my horn, could I play?'"

As the show's closer, a 10-man trumpet choir began Dizzy Gillespie's 1942 standard "A Night in Tunisia," with Dorham taking the first solo. It was the last tune he played in public.

"He showed everybody what perfect trumpet playing was about. That's how good he was," remembers Harvey. "Beautiful sound, beautiful technique. It was a master class from a master. We had about 300 people at the benefit, and there was a sustained standing ovation. It was a truly memorable moment."

If only for a fleeting moment, a 10-foot titan once again stood head and shoulders above his peers.

Blumenthal recalls a wrenching quote from Dorham: "I played one tune and got a standing ovation. It was beautiful, but it makes me sad too – that the ovations never happened when I was healthy."

On Whistle Stop, Dorham closes the masterwork with the unusually brief "Dorham's Epitaph." It remains an appropriate prophecy of immense talent, abruptly overcast in a tragic, unrequited romance with an audience he desperately desired. He needed the public to understand what he was trying to communicate.

At a certain point, Kenny Dorham knew he wasn't long for the world. He'd come from an unincorporated dust bowl in Texas to tell everyone, in so many notes, to listen. You can hear him still.

Whistle Stop (Blue Note, 1961)

The definitive Dorham album brims with originals that borrow liberally from his Southwestern roots. The bluesy "Buffalo" lopes in a regional funk. "Sunrise in Mexico" features bassist Paul Chambers' strolling bass wrapping around Philly Joe Jones' persuasive drums. Synergy recommences between Dorham and tenorist Hank Mobley.

Afro-Cuban (Blue Note, 1955)

Latin-influenced and swinging, this is a hard bop classic of the highest order, with Dorham cooking. Drummer Art Blakey blisters through "La Villa" with Mobley and baritone saxophonist Cecil Payne keeping pace. "K.D.'s Motion" swings, while "Afrodisia" nails the call-and-response motif.

Kenny Dorham Sings and Plays: This Is The Moment! (Riverside, 1958)

Few critics would list this surprising project amongst his best. However, it's one of the most honest and intriguing offerings in Dorham's discography. Though there are prior instances of him singing blues, Dorham inexplicably croons through all 10 tracks.

Una Mas (Blue Note, 1963)

First of all, as critic Scott Yanow once pointed out, Dorham's willingness to introduce and develop new players can't be overstated. The lineup includes Joe Henderson on sax, bassist Butch Warren, pianist Herbie Hancock, and teenage drummer Tony Williams.

Joe Henderson: Page One (Blue Note, 1963)

Henderson's debut shows the potential of a young genius. Dorham, meanwhile, shines throughout and contributes the jazz standard "Blue Bossa." Pleasant bossa novas (including "Recorda Me") carry the album. Dorham's stewardship of Henderson set the latter on a path to popular and critical prominence.

Cecil Payne: Zodiac (Strata-East, 1973)

Probably Dorham's finest moments during the last years of his life, he buys into Payne's funk sways. Recorded in 1968, the underrated classic launches with a tribute to the slain Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The track starts with Dorham's last transcendent solo.

"I've tried to strategically set up situations that educate folks about history they might not already know," says DiverseArts founder Harold McMillan. "If they do know, I'm offering ways for those folks to share in celebrating and acknowledging the importance of that history. The 'Backyard' provides an opportunity for us to let folks know who Dorham was."

The Urban Renewal Agency-controlled site sits on property owned by the city. The URA manages property targeted for redevelopment – per the city's master plan – which means the Backyard's occupancy at the current address isn't at all a given. Its existence depends on a series of 12-month leases.

"The vacant lots on the block we are on will ultimately be offered up for commercial development, according to the plan," says McMillan. "So, our future there is tied to that process and that timetable. The encouraging thing is that since we have shown that there is a want and need for a venue such as ours, the neighborhood plan for the block does now include a carve-out for an outdoor venue/green space that must be included in whatever development ultimately happens there."

A version of this review appears in print on August 27, 1999, on Page E00027 of the National edition with the headline: Kenny Dorham, From Be-Bop On.

Trumpet Colossus Kenny Dorham Towers Alongside the Jazz Gods

The Austin musician stands alone in showing up Miles Davis in his autobiography

by Kahron Spearman

September 14, 2018

The Austin Chronicle

Kenny Dorham was once 10 feet tall, lean and healthy.In Miles Davis' autobiography, one of the mightiest forces in music, let alone jazz, recounts a 1956 winter date at Cafe Bohemia, a onetime Greenwich Village staple. The trumpeter hadn't yet banished saxophonist John Coltrane and all-time drummer Philly Joe Jones from his short-lived "first great quintet" despite both addicts having become liabilities. Davis' critical confirmation from the four-album Prestige Records run with the quintet and his indomitable Columbia Records debut, 'Round About Midnight, remained imminent.

His friend Dorham asked if he could sit in. Davis rarely ceded the stage to anyone, but he loved and respected the Texas-born trumpeter, whom he recognized as a peer. In the only anecdote of its kind in the book, the bandleader recalls working over the packed venue before introducing his guest. Dorham swelled in his trademark romantic elegance to the chagrin of the infamously prideful Davis, who quickly realized he was being buried alive.

In search of solace afterward, Davis asked saxophonist Jackie McLean how he had sounded: "[Jackie] looked me straight in the eye and said, 'Miles, tonight Kenny is playing so beautiful, you sound like an imitation of yourself.'"

Davis gathered his possessions angrily, including his self-esteem, and walked out without saying a word. He glanced over at his compatriot, who he remembered "had this shit-eating grin on his face and was walking like he was 10 feet tall."

"[Dorham] knew what had gone down – even if people in the audience didn't," wrote Davis about his defeat, residual steam still evident in 1989. "He knew, and I knew what had happened."

Dorham wanted the audience to know. He had come all this way to tell them before it was too late.

Hobo Romanticism

"I was born at 8:30am on Aug. 30, 1924, close to Fairfield, Texas – the nearest village or township with a name recognizable to big-city folk," writes Dorham in "Fragments of an Autobiography," from Downbeat magazine's 1970 yearbook.McKinley and Minnie Dorham (née Manning), a sharecropper and homemaker respectively, had four children in all: Eva Lois Manning, Kenny, Cloteat, and Joel, who would become a noted Bay Area jazz musician. "Fragments" begins by reminiscing about the sounds of the "big Southwest" during its author's youth in Post Oak, an unincorporated community three miles south of Fairfield in central Freestone County. Aspiring to either a "top cowhand" or "a hobo" because they train-hitched and sang songs of the frontier, Dorham might have craved the land's inherent freedom as an antidote to the sick norms of Jim Crow Texas.

Thumping out boogie-woogie piano at age 7, he picked up the trumpet some three years later. Dorham asserts that his sister recognized, and ostensibly spoke into existence, her little brother's prodigious talent. She bought him his first trumpet at age 15, a silver Conn model.

By 1936, the family settled in Austin, east of then-East Avenue (now I-35) with the bulk of the city's black families. Dating back to at least the 1940 U.S. Census, 1218 E. 12th remained the Dorham homestead through Minnie's death in 1992. Attending high school at the then-all-black L.C. Anderson, the young horn enthusiast played in the Yellow Jackets marching band under the tutelage of legendary director B.L. Joyce, who chastised him for freelancing more than once.

After school, Dorham jammed at brothers Roy and Alvin Patterson's home at 1709 Washington Avenue. In tow were trombonist Buford Banks, Austin jazz great Martin Banks' father, and trumpeters Paris Jones, Warner Ross, and Gil Askey, the latter of whom gained distinction as a Motown arranger. Starting a prevailing theme throughout his career, Dorham deferred to Hermie Edwards, then Austin's pre-eminent trumpeter.

“He was on that level with Dizzy,” says Sonny

Rollins from his home in New York. “And he had a unique sound. Once you

heard it, you knew, ‘Oh yeah, that’s Kenny Dorham.’”

Career finally off to a running start, he demonstrated first-rate attributes within the big bands of Lionel Hampton, Mercer Ellington, then Gillespie. He soon replaced cherub-faced dynamo Fats Navarro in Billy Eckstine's band. Nevertheless, inconsistencies plagued Dorham, and it showed in early recordings with Navarro.

"Fats had a big, beautiful, round sound, and K.D. had a pretty squeaky sound at that time. We're talking about in the late Forties," explains trumpeter and friend Jimmy Owens. "As time went on, K.D.'s sound became sweeter. When he found that warmth in his sound, he became noticed by the public."

During 1946-47, Dorham freelanced with pianist Bud Powell, saxophonist Sonny Stitt, and charismatic drummer Art Blakey, with whom he'd have less fortunate associations. In 1948, he studied composition at the now-defunct Gotham School of Music, using his G.I. Bill benefits.

He got his first significant break in December 1948, joining sax deity Charlie Parker's quintet at the behest of group predecessor Miles Davis. By his admission, the 22-year-old Davis, at times, could be eaten up by Parker's speed. Dorham quickly presented remarkable maturity – and an ability to keep pace with Bird.

By age 25, the Lone Star blower broadened his tone, consistently rising to Bird's level, whether recording at New York hot spot the Roost or glowing at Paris' first international jazz festival in 1949. Flaunting a unique capacity to speak and sing with his instrument, versus running scales vertically, Dorham added considerable subtlety and discipline to any session.

During his year in Parker's group, an ultimate proving ground, and then subsequent work with pianist Thelonious Monk, Dorham settled neatly into his career-defining melodic and nuanced comportment. Saxophonist Jimmy Heath, now 91, calls him a "romantic."

Toot Sweet

"They holler, 'Freedom! Freedom! Avant-garde!' That's fine," writes Dorham in "Fragments of an Autobiography.""He was on that level with Dizzy, on the level with these other guys," says renowned and now retired saxman Sonny Rollins from his home in New York. "And he had a unique sound. Once you heard it, you knew, 'Oh yeah, that's Kenny Dorham.'"

"When you hear the way he plays, you know it's Kenny," echoes avant-garde pianist Steve Kuhn, who debuted on 1960 Dorham LP Jazz Contemporary.

Both Rollins, 88, and fellow saxophone great Lou Donaldson, 91, state with emphasis that Dorham's gifts equaled those of Miles Davis. Some will cry hyperbole, and indeed there's calculus necessary for a full appraisal, but there's recording greatness, and then there's greatness in performance. Kenny Dorham produced terrific, all-time moments on dozens of records, but he's even more respected as a live player.

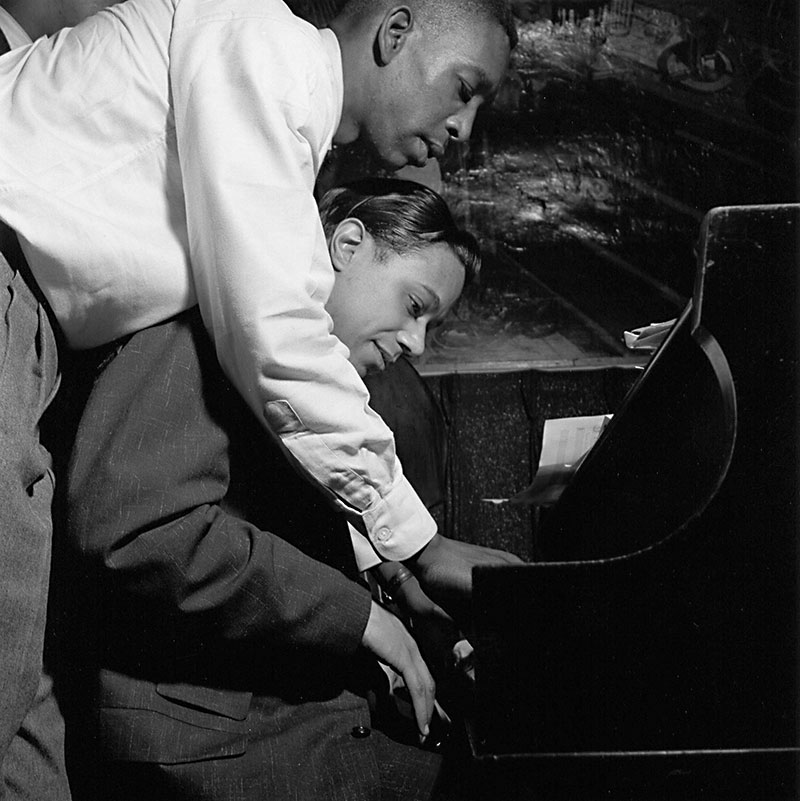

Kenny Dorham (r) with Eric Dolphy at Andrew Hill's Point Of Departure session, Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., March 21, 1964 (Photo by Francis Wolff / ©Mosaic Images LLC)

Dorham capably blended his older influences with newer bebop and hard bop sensibilities. He also played tenor sax, which influenced his stronger horn within the middle registers.

"His phrasing is more like a saxophone player, in the way a tenor phrases," says Brian Lynch, a Grammy Award-winning trumpeter. "It was a darker, a little bit less resonant sound, but adapted to the kind of expressiveness that he put into melodies."

"Historically, he's interesting because he was a modern bebop artist, yet he used traditional techniques and devices, like flutter tonguing," offers Dave Oliphant, poet and author of KD: A Jazz Biography. "There's no doubt about [his greatness], and he was the equal of Dizzy Gillespie."

1955's spectacular Blue Note debut Afro-Cuban and 1959's Quiet Kenny established Dorham as a force in composition, but his sophisticated 1961 classic Whistle Stop – the bluesy, Southwestern-tinged bop album he was destined to make – evened the recording competition with his peers despite not making him a household name. All three albums exhibited a continually developing bandleader, particularly with his layered arrangements.

"Most guys then, they would hand a lead sheet to the guys, and the rhythm section did what they wanted to do," explains Don Sickler, publisher of Dorham's catalog, on his purposeful compositional skills. "Kenny wrote a specific part for the piano player to play that was different than what the bass player played, and that was different from what the drummer would play."

And yet, though he enjoyed unending respect from his peers, Dorham believed he wasn't being heard by the listening public to the point of exasperation. He desired the elusive broad appeal. Kuhn, unprompted, says Dorham resented the absence of attention yielded to Davis or Gillespie, two stubborn alpha male types willing to deviate from bebop and hard bop purity out of survival.

Neither an assertive man nor one supported by aggressive management, Dorham never learned to "play the game," to leverage his ability in navigating the music industry's choppy waters. The consummate creative, he believed overwhelming talent alone generated all avenues. Enterprising squeaky wheel, Dorham was not.

"Kenny just never seemed to have that promotion, and that could be because he was too sweet a guy," says Rollins.

According to the liner notes of his 1964 forward-leaning opus, Point Of Departure, pianist Andrew Hill saw Dorham as the most underrated player around.

"His problem is that he's so nice, and people seem to associate greatness with meanness or bitterness," wrote Hill. "In this business, you have to create some angry or tough image of yourself to be accepted, and therefore, too many people take Kenny for granted."

Horn in hand, Dorham didn't necessarily get out of his own way. When big names began migrating left of the needle, as Coltrane and Davis eventually had, Dorham tended to maintain bop strictness. Whereas he likely could've pursued numerous opportunities doing so-called "free jazz," and later fusion, Dorham showed only occasional interest, including his essential date with Hill.

Additionally, away from performances and studio sessions, Dorham's love of the lifestyle often undercut whatever efforts he would have pursued to further his career. Chief amongst his issues remained a nasty heroin addiction he'd been carrying around since the late Forties.

Union Local 802

From all indications, Dorham was a tender, contemplative man. His brother Joel speaks as glowingly of him as his contemporaries. Dorham's wife, Rubina, had five daughters: Keturah, Leslie, Yuba Evette, Lejuine, and Lamesha.

"He was the one that you could run to, sit on his lap, and have a father-daughter conversation," recalls Keturah. "He had a wonderful personality, very handsome, well dressed. He wasn't a mean father. He didn't whip us, beat us, or anything like that."

"My father had a wonderful laugh; I do remember that," says Evette. "But often, he was more on the serious side. People mistake that sometimes for being angry, and it's not. He was always thinking about what he was doing, and the next thing after that."

The paterfamilias' warm, if utilitarian, marriage with his wife, now Rubina Robinson, proved a little less pronounced. A vague separation in 1964 isn't entirely defined by the daughters, either in reasoning or resolution. It's believed he left his family, but family members maintain the discovery of various details in his life occurred only after his passing.

Dorham (l) with Horace Silver at a rehearsal for Dorham's Afro-Cuban session, the Village Vanguard, NYC, January 1955 (Photo by Francis Wolff / ©Mosaic Images LLC)

"There were some moments when I thought, especially when I started getting a little bit older, it would have been great if my dad was here, or I could ask him to do this thing, or I could talk to him right now," she laments. "I'd call, and I'd wait for him to get back to me, or I'd go find him."

By the late Sixties, Dorham worked day jobs for sustenance – food and sometimes heroin. The addiction, picked up during his sessions with Blakey, Navarro, Hank Mobley, and others, wreaked havoc on his organs. With a wink and a slow nod, Dorham hinted at the dependence in "Fragments."

"Of course, we all belonged to Local 802, but I'm speaking of union in union, or our union."

This destructive "union," accompanied by high blood pressure, destroyed his progressively overtaxed renal system.

Not that Dorham wasn't making an effort. He became a student at New York University in the late Sixties and instructed in various youth music programs. He also wrote reviews for Downbeat. In heartbreaking logic connected to the resurrection of his worth, Dorham told former classmate and trumpeter Paul Ayick he wanted to become an educator, to get his family back together.

Ayick, who also took lessons from Dorham, describes being over at Dorham's residence when a handful of possibly hostile men arrived: "They went up to the bedroom for 10 minutes and when they came out, they were all, y'know, changed."

Like others contacted, Ayick softens Dorham's penchant for self-destructiveness.

"I don't think it was a thing he had to do all the time in those days," he says. "I think it was something he did now and then."

While Dorham's fixes eventually broke down his body, a fickle audience broke down his resolve.

Do or Die

The end of Kenny Dorham's life began immediately following an especially productive two-year period, 1963-1964, wherein he composed some of his most exceptional work, both for himself and alongside tenor maverick Joe Henderson.

His seemingly minimalist horn matured to the point

of resolute greatness, openly challenging Davis and Freddie Hubbard’s

pomp and pose with increasingly cerebral approaches, negotiating each

note with a surgeon’s precision.

Even so, the trend of missing due recognition continued through 1963's exceptional, Brazilian-influenced Una Mas and 1964's Trompeta Toccata, both featuring the young Henderson. In the liner notes to the former LP, Dorham addresses his elephant in the room:

"All I can say is that if it's going to happen, it'll happen. But it's going to have to happen within a reasonable time. After all, I'll soon be into my 25th year on the trumpet."

Concurrently with his bandleading output, he turned in tremendous work on his protégé Henderson's first few Blue Note recordings, specifically singular 1963 debut Page One and Our Thing the following year. On the former, "Blue Bossa" maintains great intrigue. The composition itself is an all-time standard, but despite his closeness with Henderson, one wonders why Dorham didn't keep the instant classic for himself.

In fact, a great deal of Dorham's best efforts reside on other artists' discography, credited or not.

"His problem is that he's so nice."

Do-or-die time was at hand, believed Dorham at age 40. Clock hard wound, he appears to have accepted the grim reading of its hands. He concluded the audience wasn't listening.

Not helping matters were breakthroughs by young guns like Lee Morgan, who crossed over with 1964's The Sidewinder, which featured Henderson. The massive hit title track was initially recorded as filler. Dorham's Trompeta Toccata in September 1964 marked the swift conclusion of what should've been his prolific prime stage as a bandleader.

The Texan occasionally produced ardent moments as a sideman, as on Cecil Payne's impressive 1973 release Zodiac. Effectually, however, the 10-foot colossus Miles Davis remembered quickly shrank. He performed and recorded less, year by year, following 1964, the year he separated from his wife and children.

By the end of the decade, his existence depended on dialysis three days a week.

Resurrection in Boston

In hindsight, what makes Dorham’s short memoir for Downbeat,

“Fragments of an Autobiography,” disheartening is that it represents

the truncated chronicle of a musician awaiting his fast-approaching

departure.

That's what Dorham told former Boston Globe critic Bob Blumenthal, then a reporter at the now-defunct Boston Phoenix, at Old West Church. According to horn blower Jimmy Owens, roughly three weeks earlier saxophonist Cecil Payne told Dorham he could receive funds for blood transfusions from his musicians' union. The latter replied that his union card had expired.

The week leading up to Dorham's death on Tuesday, December 5, 1972, he told his young friend Owens to catch him after an appointment. Owens wanted to interview his hero about his health problems and causes. Dorham told him to call after dialysis, because he'd feel stronger. This happened twice. The interview never happened.

Reedman Jimmy Heath says Dorham had made up his mind about dialysis.

"He decided not to go," reveals Heath. "He'd had enough of it, and he said he wasn't going. His lady friend told him, she said, 'Man, if you don't go, K.D., then you can't stay. You're gonna die, man.' He got tired of that dialysis thing, and he split."

Both Heath and Owens agree that their friend knew his fate. Many things had not cut Dorham's way. He would make sure the last thing would.

Dorham miraculously arrived at his own benefit at Old West Church in Boston on Sunday, December 3, an event created with the help of trumpeter Claudio Roditi and associate minister/player Mark Harvey.

"It was quite remarkable because he was not in good health," says Harvey, now a Ph.D. holding senior lecturer status at MIT. "We started talking trumpet, and he said, 'Well, I have my horn, could I play?'"

As the show's closer, a 10-man trumpet choir began Dizzy Gillespie's 1942 standard "A Night in Tunisia," with Dorham taking the first solo. It was the last tune he played in public.

"He showed everybody what perfect trumpet playing was about. That's how good he was," remembers Harvey. "Beautiful sound, beautiful technique. It was a master class from a master. We had about 300 people at the benefit, and there was a sustained standing ovation. It was a truly memorable moment."

If only for a fleeting moment, a 10-foot titan once again stood head and shoulders above his peers.

Blumenthal recalls a wrenching quote from Dorham: "I played one tune and got a standing ovation. It was beautiful, but it makes me sad too – that the ovations never happened when I was healthy."

Dorham's Epitaph

Up the road from where his 1218 E. 12th abode once stood, in a nondescript corner of Evergreen Cemetery, Dorham lies close to his parents.On Whistle Stop, Dorham closes the masterwork with the unusually brief "Dorham's Epitaph." It remains an appropriate prophecy of immense talent, abruptly overcast in a tragic, unrequited romance with an audience he desperately desired. He needed the public to understand what he was trying to communicate.

At a certain point, Kenny Dorham knew he wasn't long for the world. He'd come from an unincorporated dust bowl in Texas to tell everyone, in so many notes, to listen. You can hear him still.

Six Essential Dorham Sides

Whistle Stop (Blue Note, 1961)

The definitive Dorham album brims with originals that borrow liberally from his Southwestern roots. The bluesy "Buffalo" lopes in a regional funk. "Sunrise in Mexico" features bassist Paul Chambers' strolling bass wrapping around Philly Joe Jones' persuasive drums. Synergy recommences between Dorham and tenorist Hank Mobley.

Afro-Cuban (Blue Note, 1955)

Latin-influenced and swinging, this is a hard bop classic of the highest order, with Dorham cooking. Drummer Art Blakey blisters through "La Villa" with Mobley and baritone saxophonist Cecil Payne keeping pace. "K.D.'s Motion" swings, while "Afrodisia" nails the call-and-response motif.

Kenny Dorham Sings and Plays: This Is The Moment! (Riverside, 1958)

Few critics would list this surprising project amongst his best. However, it's one of the most honest and intriguing offerings in Dorham's discography. Though there are prior instances of him singing blues, Dorham inexplicably croons through all 10 tracks.

Una Mas (Blue Note, 1963)

First of all, as critic Scott Yanow once pointed out, Dorham's willingness to introduce and develop new players can't be overstated. The lineup includes Joe Henderson on sax, bassist Butch Warren, pianist Herbie Hancock, and teenage drummer Tony Williams.

Joe Henderson: Page One (Blue Note, 1963)

Henderson's debut shows the potential of a young genius. Dorham, meanwhile, shines throughout and contributes the jazz standard "Blue Bossa." Pleasant bossa novas (including "Recorda Me") carry the album. Dorham's stewardship of Henderson set the latter on a path to popular and critical prominence.

Cecil Payne: Zodiac (Strata-East, 1973)

Probably Dorham's finest moments during the last years of his life, he buys into Payne's funk sways. Recorded in 1968, the underrated classic launches with a tribute to the slain Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The track starts with Dorham's last transcendent solo.

Kenny Dorham's Backyard

Named after the legendary jazz trumpeter and East Austinite, Kenny Dorham's Backyard is located in the historic East End cultural district, a shout away from Dorham's former East 12th Street home. The 11th Street venue, maintained by nonprofit DiverseArts Culture Works, hosts the Austin Jazz & Arts Fest, East End Summer Music Series, and most recently, the RAS Day Festival. It's one of the remaining vestiges that black music and culture existed in Austin."I've tried to strategically set up situations that educate folks about history they might not already know," says DiverseArts founder Harold McMillan. "If they do know, I'm offering ways for those folks to share in celebrating and acknowledging the importance of that history. The 'Backyard' provides an opportunity for us to let folks know who Dorham was."

The Urban Renewal Agency-controlled site sits on property owned by the city. The URA manages property targeted for redevelopment – per the city's master plan – which means the Backyard's occupancy at the current address isn't at all a given. Its existence depends on a series of 12-month leases.

"The vacant lots on the block we are on will ultimately be offered up for commercial development, according to the plan," says McMillan. "So, our future there is tied to that process and that timetable. The encouraging thing is that since we have shown that there is a want and need for a venue such as ours, the neighborhood plan for the block does now include a carve-out for an outdoor venue/green space that must be included in whatever development ultimately happens there."

A version of this article appeared in print on September 14, 2018 with the headline: Ten Feet Tall

December 5th marks the 41st anniversary of the bebop

trumpeter Kenny Dorham’s death. Only 48 years old at the time of his

passing from kidney disease, Dorham’s professional life enjoyed a great

measure of respect from his fellow musicians, but, as Nat Hentoff

pointed out in the liner notes to Dorham’s 1963 Blue Note recording Una Mas,

“he has yet to break through to the kind of wide public acceptance

which has occasionally seemed imminent.” His recordings are timeless –

each and every one packed with delicious passion and brilliant playing

that still sounds fresh — but Dorham never did “break through” in his

lifetime, and continues to be classified by important jazz historians as

“underrated.” In a Jerry Jazz Musician-hosted conversation on

underrated jazz musicians, the most eminent jazz writer Gary Giddins

said “when anybody wrote about [Dorham] it was de rigeur to preface his

name with that word.” While the “break through” to a wider audience

Hentoff wrote about was important to Dorham, to him, “if it’s going to

happen, it’ll happen…However it goes, I’ll just keep playing. That’s

where the basic satisfaction is at.”

His music remains more than basically satisfying to his listeners. It smokes! Check out Whistle Stop, a recording Giddins calls “one of the great jazz albums,” as well as Una Mas,

on which tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson made his debut. Dorham is also

found on many other records as leader, and in the bands of Dizzy

Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Lionel Hampton, Thelonious Monk, Art Blakey,

Sonny Rollins and Max Roach.

The following “Conversation with Gary Giddins” is from a January 5, 2004 interview, where the topic was underrated musicians. This excerpt focuses on underrated trumpeters, which Dorham was characterized as throughout his career

JJM In your final Village Voice

column of December 15, 2003, you lamented about not having written

columns on the likes of Booker Ervin, Charlie Rouse, Wardell Gray and

others.

GG When I mentioned musicians

like Wardell and Rouse in that column, I was very consciously limiting

myself to dead musicians, because once we expand the dialogue and

include living musicians, it can be an endless thing. Dave Liebman, for

example, is somebody I never wrote a column about, though I’ve often

thought about it. I wrote quite a bit about Anthony Braxton in the early

years, but insufficiently about his later work. There are many others.

JJM Perhaps this is a good time,

then, to discuss neglected and underrated jazz musicians in general. I

thought we could go instrument by instrument, starting with the trumpet.

GG One musician I wanted to

write about is Malachi Thompson — I must have started a column on him

four or five times, but something always intervened. He’s a trumpet

player from Chicago, not a great virtuoso, but a solid player who works

within the bebop idiom but does so using a variety of avant-garde bells

and whistles. He allows himself and those who work with him lots of

freedom, yet it is disciplined. There’s usually some sort of harmonic

predisposition in the way he plays. I would call him an inventive

recording artist, because his albums are often thought through

conceptually, and, of course, he’s an engaging soloist. I don’t always

like when he gets into vocals and poetry and that kind of thing, but

he’s been out there a long time, making a commanding series of records —

mostly for Delmark — that haven’t gotten much attention. There are many

musicians like that; you feel your way into their work and try to get a

grip on it, and sometimes it takes longer than you would like.

Another trumpet player that I never actually did a whole column

on — and it sort of spooks me that I didn’t because he’s one of my

favorites — is Fats Navarro, one of the very pivotal players of the late

forties. I wrote a number of times about Clifford Brown, who in some

ways arrived as Navarro’s heir apparent, but he’s another musician I

feel I never did justice to because he takes my breath away. I can’t

imagine life without Clifford Brown. I rate him pretty close to the top.

But I think I need to say here that the decision about what I wrote

about was partly affected by circumstances and partly by my own

craziness. For example, when the complete Navarro Blue Notes were

collected, that would have been a good opportunity, but more pressing

stories may have intervened, or maybe I had just done a couple of

historical pieces and was focusing on newcomers — I always attempted to

balance old and new. The craziness is more emotional — I have to get

myself worked up by someone’s music to write at length about it.

JJM I think Brown is underexposed, at least to the present day audience.

GG At this point he may be, but

certainly anyone who grew up with jazz knows that Clifford is

practically a holy figure. I don’t think it’s unfair to say that his

passing, some forty-eight years ago, is still mourned. When I listen to

the tracks he recorded in a club in Philadelphia on the night of his

death, “A Night in Tunisia” and “Donna Lee,” I am torn between utter

exhilaration and tremendous sorrow for what he did not have the chance

to become. Do you know his solo on “Delilah”? — the perfect trumpet

solo. “I Can Dream, Can’t I” is another. And that opening solo on

“Tunisia” is pure genius.

JJM Did you see Warren Leight’s play Sideman?

GG Absolutely. The scene I am

sure you are reminded of is the one in which they play a tape of the

“Night in Tunisia” solo. During the performance I attended, when that

scene was over, the audience cheered and applauded. I was astounded by

that. Here we were, watching a dramatic play, which basically comes to a

stop while two guys sit at a bar and listen to a record for five

minutes. That is unheard of in theatre. Yet the audience was enthralled,

and when that solo was over, there was the kind of response you’d hear

at a musical. That is so rare. Now, how many people in the theatre went

out and bought a Clifford Brown album? That would be interesting to

know, but I think the reaction indicates how powerful his music is.

JJM You were talking about Navarro before I got you sidetracked on Brown…

GG Yes. Navarro was one of the

musicians whose influence you hear most predominantly in Clifford. He

had an absolutely spotless sound and was a brilliantly inventive player.

He was very different from Dizzy in that his phrases had a more

cautious architectural structure that allowed him to sustain a luscious

tone, and very different from Miles in that he was a solidly extroverted

player. He was one of those musicians who, no matter what the moment

called for, could come up with something creative, imaginative and

exciting. Like Brown, he died terribly young — twenty-six — part of

tragic cadre of trumpet players who died ridiculously early, including

Sonny Berman, Clifford Brown, Booker Little, and Lee Morgan, who at

least made it out of his twenties and died at thirty-three. Little was

another unique trumpet player, who came along right after Brownie. The

two trumpet players we usually think of from the early sixties are

Freddie Hubbard, the great virtuoso, and Don Cherry, the great “free”

player. Little walks between them. He is probably best known for his

work with Eric Dolphy, but he was also an interesting composer. He never

completely got his approach on track to the degree that Brownie and

Fats did. But he was so imaginative, and when you listen to him now he

still sounds modern in a suggestive way. He had a gorgeous sound,

personal and supple.

JJM Nat Hentoff’s record company recorded Little if I recall…

GG Yes, that’s right. Little

wrote and recorded a suite for Candid, where Nat produced albums. Nat

made a lot of good albums by Mingus, Phil Woods, a reunion of Hawkins

and Pee Wee Russell, Otis Spann.

JJM What about Kenny Dorham?

GG Will Friedwald once wrote a piece for me in the Voice in

which he said something like, if you look up “underrated” in the

dictionary, it says, “See Dorham, Kenny,” because when anybody wrote

about him it was de rigeur to preface his name with that word. Dorham

was the other guy who came up during the late forties bop period who

never quite achieved stardom. Yet, his Blue Note records — especially Whistle Stop,

one of the great jazz albums — show that he had his own very sleek,

very beautiful, and emotional sound. He loved long phrases that would

kind of wind in and out of the changes, and he had a tremendous sense of

time. He was a marvelous player. I’ll tell you a funny story about KD

that involves another gifted and neglected trumpet player from the

period of the late fifties and sixties, Ted Curson. Ted worked with

Cecil Taylor and played beautifully on those Mingus Candid albums with

Dolphy, and made a couple of very attractive albums on his own for

Prestige and other small labels. In the sixties, he got a shot with

Atlantic when his band had the equally underrated tenor saxophonist Bill

Barron, Kenny’s big brother. So he made a really fine album called The New Thing and the Blue Thing, which shows off what an inventive tunesmith Ted was in that period, and KD was reviewing records for Down Beat.

He reviewed Ted’s album and went on and on about how great it is, and

gave it three and a half stars. Ted asked him, “Kenny, if you love the