SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2018

VOLUME SIX NUMBER ONE

SONNY ROLLINS

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

TEDDY WILSON

(July 14-20)

GEORGE WALKER

(July 21-27)

BILLY STRAYHORN

(July 28-August 3)

LEROY JENKINS

(August 4-10)

LAURYN HILL

(August 11-17)

JOHN HICKS

(August 18-24)

(August 18-24)

ANTHONY DAVIS

(August 25-31)

RON MILES

(September 1-7)

RON MILES

(September 1-7)

A TRIBE CALLED QUEST

(September 8-14)

NNENNA FREELON

(September 15-21)

KENNY DORHAM

(September 22-28)

FATS WALLER

(September 29-October 5)A Tribe Called Quest

(1990-2017)

Artist Biography by John Bush

Without question the most intelligent, artistic rap group during the 1990s, A Tribe Called Quest

jump-started and perfected the hip-hop alternative to hardcore and

gangsta rap. In essence, they abandoned the macho posturing rap music

had been constructed upon, and focused instead on abstract philosophy

and message tracks. The "sucka MC" theme had never been completely

ignored in hip-hop, but Tribe

confronted numerous black issues -- date rape, use of the word nigger,

the trials and tribulations of the rap industry -- all of which

overpowered the occasional game of the dozens. Just as powerful

musically, Quest built upon De La Soul's jazz-rap revolution, basing tracks around laid-back samples instead of the played-out James Brown fests that many rappers had made a cottage industry by the late '80s. Comprising Q-Tip, Ali Shaheed Muhammad, and Phife, A Tribe Called Quest debuted in 1989 and released their debut album one year later. Second album The Low End Theory

was, quite simply, the most consistent and flowing hip-hop album ever

recorded, though the trio moved closer to their harder contemporaries on

1993's Midnight Marauders. A spot on the 1994 Lollapalooza Tour showed their influence with the alternative crowd -- always a bedrock of A Tribe Called Quest's support -- but the group kept it real on 1996's Beats, Rhymes and Life, a dedication to the streets and the hip-hop underground.

A Tribe Called Quest was formed in 1988, though both Q-Tip (b. Jonathan Davis) and Phife (b. Malik Taylor) had grown up together in Queens. Q-Tip met DJ Ali Shaheed Muhammad while at high school and, after being named by the Jungle Brothers (who attended the same school), the trio began performing. A Tribe Called Quest's recording debut came in August 1989, when their "Description of a Fool" single appeared on a tiny area label (though Q-Tip had previously guested on several tracks from De La Soul's 3 Feet High and Rising and later appeared on Deee-Lite's "Groove Is in the Heart").

Signed to Jive Records by 1989, A Tribe Called Quest released their first album, People's Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm, one year later. Much like De La Soul, Tribe looked more to jazz as well as '70s rock for their sample base -- "Can I Kick It?" plundered Lou Reed's classic "Walk on the Wild Side" and made it viable in a hip-hop context. No matter how solid their debut was, second album The Low End Theory outdid all expectations and has held up as perhaps the best hip-hop LP of all time.

The Low End Theory had included several tracks with props to hip-hop friends, and A Tribe Called Quest cemented their support of the rap community with 1993's Midnight Marauders. The album cover and booklet insert included the faces of more than 50 rappers -- including obvious choices such as De La Soul and the Jungle Brothers -- as well as mild surprises like the Beastie Boys, Ice-T, and Heavy D. Though impossible to trump Low End's brilliance, the LP offered several classics (including Tribe's most infectious single to date, "Award Tour") and a harder sound than the first two albums. During the summer of 1994, A Tribe Called Quest

toured as the obligatory rap act on the Lollapalooza Festival lineup,

and spent a quiet 1995, marked only by several production jobs for Q-Tip. They returned in 1996 with their fourth LP, Beats, Rhymes and Life, which prominently featured Q-Tip's nephew Consequence and production from Jay Dee (aka J Dilla). The album was nominated for a Grammy in the Best Rap Album category and reached platinum status.

Before they released their next album, 1998's The Love Movement,

the group announced it would be their final album and that they were

splitting up. Each member pursued solo careers to varying degrees of

success, but the call of the band proved strong enough that they

reunited many times over the years. They headlined the Rock the Bells

concert in 2004, toured heavily in 2006, featured on the Rock the Bells

tours of 2008 and 2010, and played a series of shows in 2013, including

some with Kanye West in N.Y.C. Though at the time Q-Tip

stated that this was the last time the group would play together, they

reunited again in November of 2015 to play The Tonight Show in

conjunction with the 25th anniversary reissue of People's Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm.

Sadly, Tribe co-founder Phife

-- suffering from diabetes for many years and the recipient of a liver

transplant -- died in March of 2016 at the age of 45. Later that year, Q-Tip

announced that the group had finished a new album. The night of their

Tonight Show appearance, the original four members of the group had

decided to put aside their differences and start recording again.

Sessions were held in Q-Tip's well-appointed home studio, and the group welcomed guests like Busta Rhymes, Elton John, Kendrick Lamar, and André 3000 to contribute. Though Phife passed before the album was finished, Q-Tip

was able to power through and complete it. We Got It from Here... Thank

You 4 Your Service was released in late 2016, topping the American

charts and earning the group attention from a new generation of fans.

https://observer.com/2016/09/a-tribe-called-quest-sparked-hip-hops-love-affair-with-jazz-on-low-end-theory/

https://observer.com/2016/09/a-tribe-called-quest-sparked-hip-hops-love-affair-with-jazz-on-low-end-theory/

A Tribe Called Quest Sparked Hip-Hop’s Love Affair With Jazz on ‘Low End Theory’

by

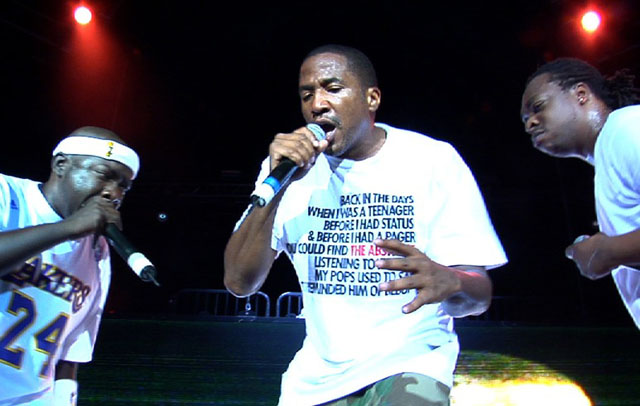

A Tribe Called Quest. Photo: Screen shot/YouTube

Senior year of high school is only as memorable as its soundtrack.

For the Class of 1992, it was raining masterpieces our senior year: Nevermind, Use Your Illusion I & II, Achtung Baby, We Can’t Be Stopped, Apocalypse 91: The Enemy Strikes Black, Cypress Hill, Badmotorfinger, Ten, Bandwagonesque, Steady Diet of Nothing, Laughing Stock, Metallica, Blood Sugar Sex Magick, Angel Dust, Check Your Head, Wish, the list goes on and on and on.

But perhaps no other record that year had more impact on the musical climate than A Tribe Called Quest’s legendary second LP, The Low End Theory.

Especially for this particular senior, who was driving to school for the first time. If you hung out in the parking lot before homeroom or after dismissal in 1991, The Low End Theory an unmistakable staple you heard everyone bumping out of their cars, especially if they had a nice kickerbox in the trunk.

What was it that made this most important Tribe LP sound so nice in a booming system? Well, those beats, of course. Those perfect, soulful grooves crafted by Ali Shaheed Muhammad for MC’s Q-Tip, Phife Dawg and Jarobi White to drop science over, establishing rhythms so quintessentially aligned with each of their highly distinctive flows.

Almost none of us rolling around in the fall of 1991 were listening to much jazz, at least in my immediate circle of friends. But the funny thing is, while we were all wilding out to such faves as “Buggin’ Out”, “Check the Rhime”, “Everything Is Fair” and, undoubtedly the epic, epic posse cut “Scenario” that closes out the album, everyone who spent a significant amount of time with The Low End Theory was receiving a serious education in jazz appreciation, whether they knew it or not.

“Tribe

influenced a generation of young people who had never really been

exposed to jazz. They were trailblazers of a modern hip-hop generation

not obsessed with violence.”—Jameio Brown

For the lay people who rocked this record back in the day, chances are the fact that every one of these songs features at least one jazz sample was of minimal concern. However, for anyone who was raised on The L.E.T., be it first, second or third hand, it was the quintessential gateway drug into the art form and its infinite universe of classic recordings comprising its genetic makeup.

Tribe were not the first hip-hop act to sample a jazz record. But they were certainly the first to feature a bonafide giant of the craft such as double-bass legend Ron Carter on a song like “Verses From The Abstract”. Carter even returns in pre-recorded form on “Skypager”, which lifts from Eric Dolphy’s “17 West” featuring the man on bass.

A quarter century later, The Low End Theroy is as ubiquitous to the language of modern jazz as Kind of Blue and A Love Supreme, its seamless fusion of beats and bop providing the seeds for future greats such as Digable Planets, J Dilla, Madlib, Greg Osby, The Roots, Flying Lotus, Kamasi, Kendrick and D’Angelo to further blur the line between jazz and hip-hop in an even more organic way than in the early ’90s. In 2016, the genres are knotted beyond the point of no return.

In commemoration of its Silver Anniversary, the Observer spoke with several modern figures on the jazz scene, plus an exclusive quote from Carter on his experience recording with Tribe, about the impact The Low End Theory has had on this most distinctive American music as the craft enjoys one of its most innovative and exploratory periods since the disco/new wave era.

Ron Carter

Q-Tip had called me and said, “I’m trying to do a record and I’m a fan of Charlie Mingus and was wondering if you could record with us.” I didn’t know who they were, so I told him, “Let me get back to you.” And I called my sons, who were into hip-hop, and asked them who this person Q-Tip is and what do you know about this band A Tribe Called Quest?

They told me they were one of the more musical groups at the time and seemed like they were more interested in making music rather than simply utilizing beats and samples. So I got back to him and said, “O.K., my sons told me this is a good thing for me to do and I trust their judgment. But I do have some caveats here. If you guys start cursing and talking like everyone else does on these records, I’m gonna unplug and go home, because that’s not my point of view. I don’t like those lyrics, I hate those kinds of words and I think they are demeaning. So if that’s what you got me into, I’m not there.”

He was immediately like, “No, no, no, we’re O.K., we’re O.K.!”

I got to the studio on time, went to the control room, plugged directly into their board, did three takes and went home. I was sorry to see them break up, but that’s what success does. However, they were really good guys and they all wanted to play piano and learn about chords. At the time, they seemed like the only ones who understood the relationship between the rhythm and the beat.

And by the way, I’m still available to anyone who wants to make some music. They keep on sampling my bass lines, but I’m still available for some live recording with hip-hop acts. So if there’s any top dog/big fish kinda guys who want to have an old man playing an antique, have them give me a call.

Robert Glasper

Tribe was my gateway to hip-hop. Literally I got into rap music because of A Tribe Called Quest. The funny thing is that it was the jazz connection, because the first thing I heard when I was like, “Wait, what’s that!” was the joint they did with Freddie Hubbard’s “Suite Sioux” off Red Clay…“Jazz (We’ve Got)”!

Being from Houston, Texas, I was listening to The Low End Theory when it came out when I was in elementary school, so I didn’t know what the hell they were talking about [laughs]. They were from Queens, while I was in Geto Boys country. So for me, it was all about the beats, and when I heard Low End Theory and “Jazz (We’ve Got)”, it just blew me away. It was really intriguing to me.

Derrick Hodge

The cool thing about The Low End Theory is that it all starts with Q-Tip and his mind, and his appreciation for, in the moment, what might be considered abstract and an abstract way of thinking. Q-Tip’s always been drawn to certain elements that he could hear the new dope thing within. Even if on the surface you might not hear it all, Tip has a knack for not only hearing it, but gravitating towards it as well.

It’s no surprise that marriage between J Dilla and Q-Tip happened. It’s just no shock, man. But it all started with Tip’s appreciation for those types of minds and that type of thinking.

And because of that, I think the music—especially on Low End Theory—has a musicality to it where an instrumentalist, whether its classical or jazz or rock or R&B or gospel, you can go do your instrument and pick up and play these songs because they’re cut up in a way that an actual horn player or bassist can play along. Songs like “Check The Rhime” and “Jazz (We’ve Got)” have a certain familiar way about them where you can play it and everybody will recognize it. The album really inhibits that feeling of natural playing.

Jameio Brown

A Tribe Called Quest’s The Low End Theory was one of the most influential albums of my life. I was not only influenced by the music, but by the culture they represented. As an African-American they reinforced the idea that to be cool was to be laid-back and intelligent, which was a contrast to groups like N.W.A. at the time. They had courage to promote being an individual.

Tribe influenced a generation of young people who had never really been exposed to jazz. They were trailblazers of a modern hip-hop generation not obsessed with violence. Sonically they fused the ’60s and ’70s with hip-hop drums. Even though my father was a jazz bassist, I didn’t feel connected to the acoustic bass until I heard them use it.

Musically and culturally they showed us the common denominators. I don’t know if I would have pursued a career as a jazz musician if it were not for what they introduced. Sampling has played a large part in the music that I have been passionate about creating because of Tribe. There are certain emotions and sounds that can only be achieved by sampling and I see that as an art. On many levels I don’t see hip-hop and jazz as different styles of music and The Low End Theory demonstrates why.

Jason Stein

Jazz has a problem finding a way to fit comfortably into contemporary culture in a way that has meaning and is not anachronistic. The Low End Theory is a great example of a band using elements of jazz in a way that felt exciting, and significant.

It also just plain sounded dope and spent months in my Walkman when I was 15. It remains an important influence to me by helping me to remember the infinite potential in the raw materials of jazz to move people’s minds, souls and especially their feet.

Jeremy Pelt

While I think Low End Theory was a record that stood out in its time, I don’t necessarily connect its brilliance with having a direct or even indirect impact on jazz when it came out. However, when you look at what some jazz artists are doing with their music now, i.e., Glasper and others, one can make an argument that there are certain elements contained in their music that harken from the things that A Tribe Called Quest incorporated in their tracks.

Makaya McCraven

Hip-hop has a long history of drawing from jazz from its inception but jazz hasn’t always been so accepting of hip-hop. Often purists question hip-hop’s musical integrity. Low End Theory was a major step in bringing respect and interest from the jazz community. Now many players of my generation grew up listening to this classic record, and it, as well as hip-hop in general, have shaped the way we hear music, approach groove, sound and composition.

Using Ron Carter on bass as well as the heavy sampling of jazz greats including Jack Dejohnette, Art Blakey, Dr. Lonnie Smith, Gary Bartz, The Last Poets and more, really opened up hip-hop as a genre with real musical integrity and value to some it’s harsher critics. A cosign from a legend such Ron Carter carries weight in a genre where purists often look down at people who “cross over.” This was especially true in the ’90s when these types of cross overs were more radical. To younger musicians who played jazz but were at home listening to hip-hop this record opened up the possibilities of pursuing new sounds and collaborations.

Low End Theory was one of the very first cassette tapes I ever purchased. Riding the line as a player and a hip-hop head was not always easy. I constantly had to try to prove that hip-hop was worthwhile musically. Low End Theory was a record I could always come back to when addressing elitists about hip-hop as a genre, pointing to the material sampled, its musicality and the depth of the rhythmic and lyrical content. Low End Theory definitely had a profound impact on me as an artist as my introduction to hip-hop and encouragement that I could follow the sounds I want to.

Anwar Marshall

The Low End Theory works as a bridge between the Jazz and Hip Hop worlds in a very unique way. The use of the upright bass, the samples that were used, and the overall sound of the mix, this record relates to jazz musicians like no other hip-hop record has.

I personally remember realizing that one of the main samples for “Butter” was Weather Report’s “Young and Fine”, which appears on their 1978 release Mr. Gone. I feel like Tribe went to great lengths to relate to instrumentalists in ways that other hip-hop groups were’t concerned with. I thought it was telling for them to feature Mr. Ron Carter on the second song of the record.

Unfortunately, the importance of the upright bass is over looked in live jazz performance and on jazz recordings, but with Bob Power on the mixing board, Tribe accentuated that sound and presented it to younger audience in a way that was palatable and really groovy.

Also, there’s at least three or four tracks that are just bass, drums and vocals, which functions as a jazz trio of sorts. This was one of the first hip-hop records that I was introduced to, and it took me years to realize how unique and ground breaking it is!

Macie Stewart

To help put things in perspective, Low End Theory and I are about the same age. That means my view of the record has always been from its future looking back, and at the age of 15 it was my gateway into hip-hop.

There was something about it that resonated with me beyond the music I had been studying and listening to at the time, catching my ear with its samples of my father’s favorites like Weather Report, Cannonball Adderley and Funkadelic. It made that music seem like something I had discovered on my own, and encouraged me to delve deeper into the world of jazz and all that it entails.

Like Q-Tip says in ‘Excursions”:

“You could find the abstract listening to hip-hop/ My pops used to say, it reminded him of bebop/ I said, well daddy don’t you know that things go in cycles/ The way the Bobby Brown is just ampin like Michael.”

Music moves in cycles. Jazz is creeping its way back into the mainstream time and time again, I can see it in the recent music of Kendrick Lamar, Robert Glasper, Thundercat and even David Bowie.

The Low End Theory and Tribe sampled jazz in such a unique way that it enabled their voices to solo effortlessly over the track much like Dizzy or Coltrane would. That record defied boundaries and created a space for music to exist just for the sake of itself. It took something familiar to the youth (hip-hop) and made it accessible to the previous generation by paying homage to all of the great artists that came before them, and pushed the generations after them to explore what it means to make music. In that way it continues to feed future musicians, encouraging them to create by building on traditions of the past.

Eric Slick, Dr. Dog

I remember first hearing The Low End Theory in 2007. My best friend Dominic turned me onto it. We went to jazz school together, but I soon dropped out. I thought the whole thing was just so square. Dom stuck it out and ended up playing on countless sessions with Dice Raw, Peedi Crakk and members of the Roots Crew. He was aghast that I had never heard Tribe, so we drove around and listened to all of Low End Theory.

I remember thinking that the album was somehow simultaneously futuristic and stark. I was also disappointed in myself that I’d never given it a shot before.

Over the course of the next few years, I would go to Silk City Diner in Philly every Monday night for a live jazz/hip-hop improv night. I’m fairly certain The Philadelphia Experiment started there. Another jazz/hip-hop bridge! Questlove, Anthony Tidd, Spanky and many MCs and other luminaries would come through and devastate the place.

I remember sitting in and feeling so inspired to try something different. It was a jazz school education that I didn’t have to pay tuition for. It’s hard to think of sessions like that happening without the forward-thinking influence of Low End Theory, and I’m incredibly grateful for it.

Shabaka Hutchings, Shabaka and the Ancestors

One of the remarkable aspects of this album is the opening phrase from Q-Tip—”You could find the abstract, listening to hip-hop/ my pops used to say it reminded him of bebop/ I said well daddy don’t you know that things go in cycles.”

This is an artist overtly positioning his music, and the music of his generation, within a lineage stemming from jazz yet manifested through a music form championing a very different set of aesthetic values.

This quote made me think at a young age about how the musical sensibilities of a given community can be represented in differing forms/genres across generational lines. It also made me start considering the role of the artist himself in framing the way his music is perceived (as opposed to academics and “historians”). This has definitely influenced my desire to take the reins in articulating the historical forces, which comprise the music I make.

Mark Guiliana

Low End Theory is a modern day masterpiece. The carefully selected samples, often from seminal jazz records made decades earlier, provide a warm and organic sonic foundation for Tribe’s masterful rhymes.

Corey King

This album was definitely a defining moment in my life. I remember listening to it in my uncle’s car and knowing instantly that I would pursue music. This record not only brought my generation to love hip-hop but also, to a certain degree, educated my generation on jazz music. The bass lines sampled on this album were genius and the delivery from Phife and Q-tip was reminiscent to a horn player’s phrasing over a blues.

In high school, my friends and I would try and arrange jazz standards with ideas inspired by The Low End Theory. This was years after this record was released and it was still buzzing in my network of friends. The Low End Theory’s colors and layers were ahead of its time. In my opinion, it was a total game changer.

Matt Moran, Slavic Soul Party

When I was a student at Berklee College of Music I read that a hip-hop group called A Tribe Called Quest had put out a jazz-influenced record, and I went out and bought it almost immediately (on cassette). I listened to it about three times in a row, trying to figure out what was going on.

For me, deep in an obsessive and still immature relationship to jazz, the album was a bit of a revelation: while it sampled a lot of jazz records—and what a thrill to hear a shout-out to Ron Carter in popular culture!—it didn’t feel at all like jazz to me, in fact it felt like its opposite. It started with an MC saying that hip-hop today was the be-bop of its day, but I wasn’t hearing it, and that was a shot across the bow.

It was my first visceral awareness that what I loved about jazz was not what most of America heard in jazz; to me, the digital looping of a few notes or bars was the very opposite of jazz, and the expressionist spirit of those instrumentalists had been harshly confined. It was a lesson in orchestration: the instruments used and how they sounded was more important to listeners than what was actually played.

Over the years I listened to the album occasionally, and gradually gained an appreciation for the cultural significance of the album, and the artistic goal of creating a new African-American music that showed respect for jazz. I came to love that there was a contemporary dance music being made that did use the orchestration of jazz, when those sounds were being increasingly sidelined in popular culture.

Jarobi White, Q-Tip, Phife Dawg and Ali Shaheed Muhammad of A Tribe Called Quest perform in Austin, Texas, at SXSW. Photo: John Sciulli/Getty Images for Samsung

Ben Wendel

When I was growing up in Los Angeles, I had a record/tape/radio player. Most of what I listened to was jazz LPs that my neighbor gave me and hip-hop from a 24-hour AM station called KDAY. When you are 13, you don’t necessarily categorize music—you listen to everything with open ears. I was moving between John Coltrane, Charles Mingus and Miles Davis and Tribe Called Quest, De La Soul and Busta Rhymes. It felt seamless—even then I felt like there was a connection between these two art forms.

I can look back now and see that in fact there has been a long history between jazz and hip-hop. I would argue that hip-hop is jazz in the larger context, or at least part of the continuum of improvised music. Tribe was the first group I discovered using jazz masters like Ron Carter in their recordings. Since then, there have been so many more examples of this connection, and not surprisingly those artists/albums tend to be my favorite.

A few collaborations that come to mind include Mos Def working with Robert Glasper, Q-Tip working with Kurt Rosenwinkel, Snoop Dogg working with Terrace Martin and Kendrick Lamar working with Kamasi Washington and Thundercat.

Thanks to Terrace Martin, I actually got to tour with Snoop Dogg briefly. The feeling I came away with from that experience is that all music is interconnected and, at the highest level, free of genre. That’s what I feel I have learned from groups like Tribe Called Quest—that true creativity is open to any and all input.

The Unlikely, Triumphant Return of A Tribe Called Quest

The

new album from A Tribe Called Quest, “We Got It from Here . . . Thank

You 4 Your Service,” is about trying to be a better person: to engage

with the world in deeper, more mindful, and more loving ways.

Photograph by Chad Batka / The New York Times / Redux

On a recent Friday evening, the hip-hop journalist Elliott Wilson had gathered Q-Tip and Jarobi White, two members of A Tribe Called Quest, along with the rapper Busta Rhymes and the producer Consequence, two recent Tribe collaborators, onstage at Webster Hall, a club in the East Village. The event was part of #CRWN, an interview program hosted by Wilson, the founder of the Web site Rap Radar and a former editor-in-chief of XXL; the show is recorded in front of a live audience and later broadcast on the music-streaming service Tidal. All five men were seated on tufted red-velvet chairs.

A week earlier, A Tribe Called Quest had released “We Got It from Here . . . Thank You 4 Your Service,” its first new album in eighteen years. That same week, the group was the musical guest on an episode of “Saturday Night Live,” hosted by Dave Chappelle—the first to air after the election. At Webster Hall, Q-Tip, who was wearing shiny leather pants and a leopard-print coat, described it as “the blackest ‘S.N.L.’ ever”—or at least, he suggested, the blackest since 1975, when Richard Pryor and Gil Scott-Heron appeared on the show together. Early estimates indicated that “We Got It from Here” was about to début at No. 1 on the Billboard chart. (It did.) The mood in the room was appreciative, grateful: here, at least, were developments that felt redemptive.

Nobody was expecting A Tribe Called Quest to announce a new album in 2016. Last spring, Phife Dawg, one of the group’s founding members, died, at age forty-five, of complications related to his diabetes. The group had been on some kind of vague but seemingly interminable hiatus since 1999, just after the release of its fifth LP, “The Love Movement.” Its members reunited periodically for live performances, but there were complicated and long-standing interpersonal tensions between Q-Tip and Phife. The band’s influence might have been permanently threaded through the pop charts, but a true return seemed unlikely.

The glimpses, though, had been tantalizing. In late 2015, the original lineup—Q-Tip, Phife, White, and the d.j. and producer Ali Shaheed Muhammad—appeared on “The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon,” to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of their début album, “People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm.” They performed a single from that album, “Can I Kick It?,” with the Roots, Fallon’s house band and a hip-hop institution on its own. In the footage, Fallon, who is famously excitable, appears to be quivering with anticipation as he introduces them. (After the performance, when Q-Tip disappears from the stage, Fallon hollers “Oh, my God!” five times.)

“Can I Kick It?” samples the spindly, loping bass line from Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side,” and bits of “What a Waste,” by the British new-wave act Ian Dury and the Blockheads; “Spinning Wheel,” by the jazz organist Dr. Lonnie Smith; “Dance of the Knights,” by the Russian pianist and composer Sergei Prokofiev; and “Sunshower,” by the swing-influenced disco outfit Dr. Buzzard’s Original Savannah Band. This sort of caste-free cross-pollination seems unremarkable now, in an era in which everything is instantly available and unmoored in time, but in the early nineteen-nineties Tribe’s eclectic and carnivorous sampling felt bold, almost obscene. It is, at least, a metaphor for the group’s ideological mission—a reiteration of the idea that the generous intermingling of cultures yields beauty and understanding. “Can I Kick It?” is a docile song that opens with a self-ratifying call and response: “Can I kick it? Yes, you can.” Q-Tip’s voice—nasal, mousy, bookish—is steadying. He remains disinterested in the histrionics that plague less confident m.c.s.

For years, there was a mumbled consensus that A Tribe Called Quest, with its socially conscious lyrics and avaricious sampling, was hip-hop for college-educated white people who were frightened by Ice Cube. This is a reductive and unproductive idea, of course, but it is probably somewhat true—though the group also inspired plenty of young black artists, too. (“Tip’s kind of like the father of all of us, like me, Kanye, Pharrell,” André 3000, one half of the Atlanta-based duo OutKast, recently told the Times.)

The two highest-charting rap songs in 1990—the year that A Tribe Called Quest released its début—were Vanilla Ice’s “Ice Ice Baby” and M.C. Hammer’s “U Can’t Touch This.” In Los Angeles and Miami, groups like N.W.A. and 2 Live Crew were making artful and provocative records—building a vehement case for rap as a reimagining of folk music, a medium for populist unease, distrust, and insurgency—but for most casual American listeners hip-hop was a novelty genre. You either built a clever, hyper-verbal, honking pop song around a familiar hook or you seethed.

A Tribe Called Quest suggested a different path. The group’s gentler, more cerebral approach borrowed plainly from the spirituality and rhythms of jazz, and, along with De La Soul, Queen Latifah, Monie Love, and Jungle Brothers, Tribe became the nucleus of a New York City-based collective known as Native Tongues. The movement was deeply Afrocentric, preoccupied by obscure samples sourced from rare vinyl, and resistant to violence and misogyny as lyrical themes.

The electricity of last year’s “Tonight Show” performance is what facilitated the recording of new material. “We were talking so much shit that night. It was crazy—it was a great night,” Q-Tip recalled. Tribe reconciled, and the group, along with a cabal of guests—including Kendrick Lamar, Jack White, André 3000, Elton John, Kanye West, Anderson Paak, and Talib Kweli—retreated to Q-Tip’s New Jersey home, where he keeps a professional studio. He was insistent that the work be done there, collaboratively. Verses would not be phoned in. A giggly, domestic warmth is palpable on some tracks; this is a place artists get to only when they have been alone in a basement for too many hours, stabbing at cartons of congealing takeout. But Phife, who was receiving dialysis treatments, might have been weakened by the work. “He basically gave his life to make this album,” Jarobi White said.

“We Got It from Here” is a record about trying to be a better person: to engage with the world in deeper, more mindful, and more loving ways. This has been a theme for A Tribe Called Quest since the group’s outset. Recorded several months before the election, the album feels farseeing if not prophetic in its accounting of current affairs. “The world is crazy and I cannot sleep,” Q-Tip announces on “Melatonin.” (His advice? “Pop melatonin like they Swedish Fish.”) On “We the People . . . ,” he offers a plainspoken entreaty for solidarity and understanding: “When we get hungry, we eat the same fucking food—the ramen noodle.” The chorus, meanwhile, is a recounting of a nightmarish America, in which Mexicans, black folks, poor folks—all must go. “Muslims and gays, boy, we hate your ways,” Q-Tip sings.

At the #CRWN taping, the election results were still on Q-Tip’s mind. He described the surge of protesters thronging Fifth Avenue, stomping uptown toward Trump Tower during the group’s “S.N.L.” performance. “I think people voted for him out of anger—from a lack, from not-having,” Q-Tip said. “For people to look at this record, the timing—even if it’s not doing anything other than making them feel better—that’s beyond all of us.” There was also a sense that the album had been palliative for the group itself, in more personal ways. The members were able to offer a posthumous gift to their friend. It was Phife’s birthday that week. “Phife is looking down and laughing his ass off at all this shit,” Q-Tip said.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Amanda Petrusich is a staff writer at The New Yorker, and the author of “Do Not Sell at Any Price: The Wild, Obsessive Hunt for the World’s Rarest 78rpm Records

https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/a-tribe-called-quests-the-low-end-theory-10-things-you-didnt-know-106475/

A Tribe Called Quest’s ‘The Low End Theory’: 10 Things You Didn’t Know

From the N.W.A influence to the “Butter” fight, read little-known facts about the 1991 hip-hop landmark

Mosi Reeves

Rolling Stone

In honor of the 25th anniversary of A Tribe Called Quest's 1991

landmark 'The Low End Theory,' read 10 facts you likely didn't know

about the album. Al Pereira/Michael Ochs Archives

Released on September 24, 1991, A Tribe Called Quest’s The Low End Theory is

the quintessential moment where hip-hop let its jazz muse fly. Others –

most notably Gang Starr – had explored fusions between jazz and

hip-hop, but Q-Tip,

Phife Dawg and Ali Shaheed Muhammad evoked a cool bebop ethos that none

had achieved before. They metaphorically drew comparisons between their

lyrical gems and jazz players like Lonnie Smith, Grover Washington, Jr.

and Ron Carter, the latter joining the Theory sessions to add his

supple bass notes to tracks like “Excursions” and “Buggin’ Out.”

Numerous moments linger in hip-hop’s firmament, whether it’s Q-Tip’s

“4,080” rule for record labels; oft-sampled lines like Q-Tip’s “wait

back it up, wait, easy back it up”; or boom-tastic cipher session

“Scenario,” which turned Busta Rhymes into a star and inspired years of

rah-rah chants from Onyx, Black Moon and more. To celebrate the 25th anniversary of one of the greatest hip-hop albums, here are 10 things you might not know about The Low End Theory.

1. In order to make The Low End Theory, Q-Tip had to pull Phife off the street.

Many of us are still mourning the March 23rd death of Phife Dawg, whose vocal interplay with Q-Tip resulted in some of the most treasured music in hip-hop history. But back in 1990, he was still a Jamaica, Queens teenager more interested in having fun and chasing girls than pursuing a rap career. That’s why he only made brief appearances on the group’s debut, People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm.

In a 2015 interview with Rolling Stone, Phife remembered, “A couple of months before we started working on Low End, I just happened to run into Q-Tip on the train leaving from Queens going into Manhattan. He was like, ‘Yo, I’m about to start recording this next album. I want you on a couple of songs, but you have to take it serious.’ … I took that into consideration along with the last couple of shows we did for that first album. I saw how fruitful things could get.”

2. N.W.A’s Straight Outta Compton helped inspire Tribe.

The Compton squad’s studio debut is widely known as the greatest gangsta rap album of all time. Less remembered but equally important is how Dr. Dre flipped Public Enemy and the Bomb Squad’s barrage of funky noise to fit a West Coast aesthetic; making key interludes out of samples of black comedy pioneers like Rudy Rae Moore. It was Dre’s next-level production techniques that inspired Tip and Muhammad. “I remember driving with Ali, I was like, ‘Yo, we gotta make some shit like this,'” Tip told RBMA in 2013. “Dre is such a master the way it was laid out.”

3. Phife had to fight for his “Butter” spotlight.

Q-Tip originally planned for “Butter” to be another mic-trading session, but Phife wanted the track for himself. “We had a quasi little tiff over it,” the former told VH1 in 2011. Eventually, Phife wrested control, and turned “Butter” into a lyrical showcase where he ironically contrasted his “smoothness” with his frequent girl problems. Meanwhile, Tip rocked on the hook. “How I was on the chorus and how [Phife] was doing the rhyme … it just felt like if it was the Beatles, and John would sing lead on one and then Paul would sing lead on another and John would be backing him up,” said Tip.

4. Competition between De La Soul and Tribe led to Vinia Mojica’s hook on “Verses from the Abstract.”

Vinia Mojica is one of the great, unsung session vocalists of the Nineties, landing on tracks by Heavy D, Mos Def and many more. Although she appeared on People’s Instinctive Travels skits as part of the crowd noise, her breakout moment came when she sang the incandescently sunny hook for De La Soul’s 1991 summer hit, “A Roller Skating Jam Called Saturdays.” “The boys had a lot of love-hate rivalries. … They always wanted to one up each other,” Mojica said in a 2012 interview with Revive. “I think that’s why Q-Tip asked me to do something for their album, even though I was on their first album in the snippets in between.” More poignantly, Q-Tip also gave a dedication to Mojica’s mother near the end of “Vibes and Stuff.” “My mother had died during the time of the making of their second album,” she explained.

5. “Industry Rule #4,080” may refer to Jive Records.

Throughout the years, Q-Tip has been somewhat coy about the inspiration for his memorable “Check the Rhime” line: “Industry rule number 4,080, record company people are shadyyyyyyy.” In the excellent The Big Payback: The History of the Business of Hip-Hop, Dan Charnas speculates that the widely quoted “rule” resulted from Tribe’s increasingly fractious dealings with Jive Records, as well as changes in their management. “The members of A Tribe Called Quest were teenagers when they signed,” he writes. “It was only after their first album was released and they began reviewing the budget for their second that they became aware of the tangle of deals to which they were bound.” When the group switched from Red Alert Productions to Rush Artist Management, Tribe demanded more advances in order to deal with the resulting costs of separation, so Jive extended their contract to one more album. The red tape took over a year to untangle, and left an air of mistrust between Tribe and Jive, resulting in bitter Theory cuts like “Show Business.” Meanwhile, “4,080” has entered rap lexicon as shorthand for record label chicanery.

6. Phife Dawg’s stray shots almost led to bloodshed.

It’s a legendary tale of beef from hip-hop’s pre-Bad Boy vs. Death Row days: When Phife Dawg rapped “Strictly hardcore tracks, not a New Jack Swing,” Teddy Riley’s protégés Wreckx-N-Effect, who landed a major pop-rap hit in 1990 with “New Jack Swing,” took offense. On March 16, 1993, their crew retaliated by punching Q-Tip in the eye outside a Run-DMC concert at Radio City Music Hall. To avoid further violence, the Zulu Nation brought the two factions to the Nation of Islam’s Muhammad Mosque #7 in Harlem, where Minister Conrad Muhammad brokered a truce. However, no one seemed to mind Phife Dawg’s Vanilla Ice dis on “The Scenario (Remix)”: “Vanilla Ice platinum? That shit’s ridiculous!”

7. Pete Rock made the original “Jazz (We Got).”

The song heard on The Low End Theory is a rearrangement of a beat Q-Tip heard while visiting Pete Rock. “One time the ‘Jazz’ beat was already playing in the drum machine. I went to answer the door and left the beat playing. He came downstairs like, ‘What the fuck is that?'” Pete Rock told Wax Poetics in 2004. “He knew what I used and took the same elements, and made it the exact same way.” Tip, for his part, claims that he got permission to remake it. His shout-out on “Jazz (We Got)” – “Pete Rock for the beat, ya don’t stop” – was a tacit acknowledgement of the beat’s origins.

8. “Scenario” originally included more members of the Native Tongues.

As Tribe and Leaders of the New School worked on “Scenario,” word spread amongst the Native Tongues fraternity. Eventually, Posdnous from De La Soul, Dres and Mista Lawnge from Black Sheep, group manager “Baby” Chris Lighty (who passed away in 2011), and even enigmatic fourth Tribe member Jarobi snapped on it. In Brian Coleman’s book Check the Technique, Tip remembered, “We didn’t know which one to use. We wanted to get everybody on there, but it was still obvious which one was the best, and we went with that one for the final album version.” A subsequent remix featured Kid Hood, a previously unknown rapper who was murdered two days after recording his verse. The rest of the Native Tongues’ raps remain unreleased.

9. Q-Tip wrote part of Busta Rhymes’ iconic rap on “Scenario.”

Busta Rhymes’ legendary “rawr rawr, like a dungeon dragon” fireworks at the end of “Scenario” is all his. However, Q-Tip wrote the handful of bars – “I heard you rushed, rushed and attacked” – in the middle of Tip’s verse. “He had his rhyme written and he told me to say his part. He did it in a Busta Rhymes style so when I did it, it sounded like it,” Busta told XXL in 2012. “He wanted me to come in on his part, set me up.” In turn Busta concluded “Scenario” with one of the greatest rap verses of all time.

10. The Low End Theory marked the beginning of the end of Native Tongues.

During the recording sessions for The Low End Theory, Q-Tip decided to switch from pioneering New York DJ and Native Tongues mentor Red Alert to Russell Simmons’ Rush Management, with Chris Lighty as their point man. The split opened wounds that never truly healed between Tribe and De La, and on the other side, the innovative, perpetually underrated Jungle Brothers. “Jungle didn’t fuck with us [after the switch]. Everybody was hurt,” Tip told Vibe in a 2007 story on the rise and fall of the influential crew. In the same article, Afrika Baby Bam added, “[People] have been trying to erase the Jungle Brothers out of the books, when I was the one that started the whole thing.”

https://cultmtl.com/2017/01/a-tribe-called-quest-interview-2016/

Music | News

An interview with A Tribe Called Quest

Jarobi and Q-Tip

Finished or done, puttin’ some respek on 2016 seems to be a tough prospect for many.

But if you lean that way, hip hop carried you through. If anyone put out a bad rap record this year, I don’t really know. There was too much good shit to choose from, new music that for whatever reason feels timely and timeless at once, making 2016 a pleasure not only to keep up with, but a year to remember forever. If the album format is truly dying, 2016 must have been too busy racking up genius musician souls to have noticed. And no one could attest to either of those points more this year than A Tribe Called Quest.

You can’t blame the calendar. But when March 22 of this year took Queens, NY native Five Foot Assassin, Malik Izaak “Phife Dawg” Taylor — aka Phife, the Phifer, Mutty Ranks and Donald Juice, to mention a few — hip hop found its place at the ongoing rock star wake that was 2016.

At 45, the smooth-flowing, hyper-quotable bar spitter succumbed suddenly to a lifelong diabetes battle, leaving his bandmates, contemporaries and fans worldwide in grief.

A little over year ago, A Tribe Called Quest had just reissued their debut LP, People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm, commemorating its 25th anniversary with fresh packaging and newly mastered versions of the classic material therein. Reuniting for a rare televised performance on Late Night With Jimmy Fallon, the Tribe, backed by brothers-in-arms the Roots, treated fans to a powerful rendition of a signature track, “Can I Kick It?”

It felt too good to be true, but for five minutes or so, A Tribe Called Quest were back. Phife Dawg, his lifelong homie Q-Tip, their DJ Ali Shaheed Muhammad and their “spiritual essence,” less seen and heard over time but still very much a constant force in the group’s energy, Jarobi White (“sometimes ‘Y’” to Midnight Marauders appreciators) gave it all for a segment that felt historic and, to fans longing for even a hint that the foursome would return, just right.

And that was supposed to be it, really. The Tribe had, since disbanding in 1998, done a handful of reunion shows, at Rock the Bells and on tour for a few dates with Kanye West, most notably. Michael Rappaport’s somewhat controversial 2011 documentary on the band highlighted the personal divisions between Tribe members — especially Phife and Tip — making the idea of a comeback more remote than ever in the minds of many fans. And Phife’s death four months after the Fallon appearance seemed to make it a moot point.

At this time last year, myself and fellow Montreal-based music journo Erik Leijon were getting ready for a year-end radio special, and we thought it would be cool to invite someone from the band to discuss their celebrated TV one-off, the album reissue and Christmas rap tunes, for good measure. I’d had the privilege of speaking to both Phife and Shaheed in the past, and getting Q-Tip seemed like a stretch on short notice.

I’d followed Jarobi (a professional chef with cool pop-up concepts in NYC and around the U.S. on the go constantly) on social media for a while and figured I’d ask this more reclusive personality for a few moments, which he gladly obliged.

All in good fun, we talked about the past and present, his culinary passions (White left full-time Tribe duties early on to pursue a career as a chef) and of course, the future. Any chance of A Tribe Called Quest burying their respective hatchets and getting on the road or in the studio?

Jarobi deflected the question with a subtle, “You never know”-type reply, pretty much as expected. What he obviously couldn’t tell us was that the band were already deep in the cut at Q-Tip’s home studio, laying down the foundation for what would become their final album, We Got It From Here…Thank U For Your Service.

Announced just three weeks prior to its Nov. 11 release date, news of a new Tribe album caught swift mega-buzz. Who produced it? How would the loss of the Phife Dawg affect the outcome? Would it be good? Who would guest? Could it possibly meet the standards that ATCQ’s legacy still thrives on, nearly two decades after their last studio excursion?

The near-immediate consensus among heads when the record dropped a day early was formed by the end of the first track: A Tribe Called Quest, representing, once again. We Got It From Here… lives up to its title’s promise in every conceivable fashion, not only satisfying longtime listeners but actually hitting #1 in over 30 countries in its first week.

Lest we forget, the album appeared just days after the U.S. election. Its most official launch party yet remains a “divinely” timed Saturday Night Live musical guest slot for Tribe, while Dave Chappelle made his own television comeback as host. If there’s such a thing as a good time to make some more history, ATCQ couldn’t have set the clock any more precisely.

And the moment, lovely as it was, came with more than a touch of the bittersweet. The SNL performances honoured Phife Dawg’s living legacy in a fashion only a group as visionary as A Tribe Called Quest could ever grasp well enough to manifest in sight and sound. Tip, Shaheed and Jarobi — and later longtime collaborators Busta Rhymes and Consequence — showed they were out to be on top with their friend, and for their friend, but never without him.

Jarobi and Phife met in their early double-digits, their shared love of hip hop being a significant focal point of their forged friendship. Tip and Phife, as has been well documented, were inseparable from toddler-hood on, growing up together side by side with hip hop. Jarobi meshed with the pair as they all began to jam in their early teens, setting the stage for the Tribe.

“That’s my brother,” Jarobi says, still audibly shaken and affected by the loss of Phife Dawg.

I spoke to Jarobi again this December, with a decidedly different tone to the proceedings in light of the year that was. Again, the MC, who shines on this new album in a whole new light, lent his time gladly and candidly, despite the pain so clear in his voice at times.

What follows is the entire transcript of that conversation. We talked about the new album, the circumstances of its manifestation, the loss of Phife, the year in music, Anderson .Paak, Kanye West, De La Soul and more.

Jarobi has long made clear he will speak only when he feels necessary, so it is with great respect that we bring you this conversation with one of 2016’s biggest newsmakers in music.

Darcy MacDonald: So we spoke exactly a year ago today, I realized earlier. Tribe had just reissued People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm for the 25th anniversary, and you had all been on Fallon, and our conversation was in the spirit of that fun, that day.

But I asked you about future plans for A Tribe Called Quest. I guess you were keeping a lot under your hat. And there’s a certain symmetry at play here.

Jarobi: Absolutely. We had already started working on the album by then.

DM: How much can you reasonably say you ever saw coming in the year that was 2016, and what stands out the most?

Jarobi: (kinda half-laughing) Shit, 2016 was a fuckin’ horrible year, like a fuckin’ terrible year. One of the worst of my life. What stands out the most? I mean, the passing of…losing my brother. You know what I mean?

DM: Yeah.

Jarobi: That’s definitely like, there’s nothing that has shaped or impacted my life, nothing even comes close. Like, the record, like — nothing comes close to that.

DM: In working through that grief, what did that do to you personally in terms of getting the new project to see the light of day? Where do you stand now?

Jarobi: You know, I don’t really know. People ask me that, like ‘How does it feel?’ and all that and I can’t really explain it. Like, I’m happy that the fans and people feel like they got what they wanted from us, you know what I’m sayin’? I’m super happy they’re enjoying it and feel good about the project. But uh, you know, I wish that Phife was here to see how much all of these people love us.

It’s truly, truly, truly, truly humbling. For us not to have put out a record in so long and people still pay attention, in itself, is crazy. (laughs)

DM: Did you have a chance to really go in with Phife in the studio, and get creative together?

Jarobi: Me and Phife…I sat with him as he wrote every word on this album. Every syllable. I sat with him. Every syllable. If that’s any indication.

DM: What do you think, whether on this record or over time, that the particular chemistry you two shared brought to Tribe as a whole?

Jarobi: Number one, that’s my brother, and creatively (we were) totally symbiotic and shit, man, because we logged in all the hours together. If he was writing something and was like “What’s the next word?” it’s like, “Blam!” And vice-versa of course.

DM: In retrospect, now that you hear the album as a complete work, in terms of both before and after Phife’s “move to the stars,” as it were, how do you feel about the end result and how does it help you frame your friend’s legacy, as well as that of your band?

Jarobi: I can only speak for myself. This album is definitely a living tribute to Phife. And it’s very gratifying for this shit to be #1 in like, 30 countries or whatever it is? (laughs) Know what I’m sayin’? Wherever Phife’s sitting, he’s like, “That’s aight!” Definitely.

DM: So the timing of the release and the SNL appearance alongside the election of Trump was sorta perfect in terms of Tribe’s contributions to relevant message music through the band’s early history. The album was released on Veteran’s Day, and “thank you for your service” is a phrase associated to battle vets.

How much of that was planned — be that the album or SNL appearance — to line up with the election, and how much of the timing was coincidence?

Jarobi: There’s no such thing as coincidence, firstly. Coincidence is just a symptom of being prepared.

Everything about this album is divinely inspired. That’s why I have a hard time, when they’re like “Yo, Jarobi! You destroyed this shit, you killed this shit!” I have a hard time being like, “Oh yeah, I was dope up in it!” Because shit, this whole process was like, I put my hand on a writing instrument and put that on a paper and that shit just starts fuckin’ breathing. So even things I’m talking about, I had a different idea going in of how I would present myself and shit.

DM: In what way?

Jarobi: Think like, a song like “Enough!!” You know? Like, cool, playful, nerdy. But serious times required serious words and I had to speak to all the shit that was going on while we was in the studio. That’s just… that’s just fuckin’ crazy. ‘Cause we locked ourselves in, me and Tip, and grinded it out. We watched a lot of Black exploitation movies, a lot of rock documentaries, and just keeping up with current events. And that led to the subject matter that’s on this album, man.

And the timing of the SNL appearance and being on that, with the timing of the album release and the election and all that… it’s like I said man. Some of these things are just divinely inspired.

DM: I read the Wax Poetics interview with you guys this year — your final interview as a group with Phife — where the author asked about the subject matter of People’s and you were quoted as saying, “At that time, in the late 1980s, police brutality, Afrocentrism and STDs were all hot button issues that we were dealing with in society. The most important thing in our music was the truth and reality of it.”

So now in light of that, and these times and history’s propensity to repeat itself, what do you think the return of Tribe potentially represents at this juncture in U.S. social history?

Jarobi: This (reality now) feels like the same desperations that we were in at that time, on this album. Shit, even Chuck said this shit back in those days, like, “Cycles, cycles, life runs in cycles.” That’s how it’s been. I guess that’s why we were awoken, you know? Because the times repeat themselves. And I dunno, maybe because of our work ethic and our aesthetic, we’re maybe people who can better articulate this shit for for people right now. I dunno! (laughs) You know what I’m sayin’?

It’s hard to analyze this shit, it’s beyond analyzing.

DM: So I appreciate what you said about not feeling one way or the other about the personal accolades you’ve gotten with this album, but you do kill it man. And in particular, you have a big tune on here with Consequence and Anderson .Paak, who is gonna go out on top of 2016 as a breakthrough artist of the year. What are some of your thoughts on .Paak, and on that collaboration?

Jarobi: Yo man. I just got back from L.A. And I just saw Anderson .Paak perform at the motherfuckin’ Palladium. Jeeee-sus Christ, man! Jesus Christ. This dude is the truth. The truth. I mean you listen to the album be like, “Goddamn, this is phenomenal!” But shit man, watching that shit live? His performance? His command of the crowd, the showmanship…

DM: Just wild.

Jarobi: The showmanship is of the old aesthetic, like us, and people of our generation. And people like Kanye, who give a fuck about their stage showmanship. (.Paak) is brilliant man, dude is fuckin’ ill. And our song (with him) “Movin’ Backwards” came out absolutely phenomenal. And I dunno, I wasn’t like “That verse is ill” when I wrote it. It didn’t impress me that much, I’m being honest with you! (laughing)

But after I got away from it and heard it again, I was like, “Oh wow, I like that shit.” That became one of my favourite joints on the album now.

DM: I chose Anderson .Paak as my show of the year and I saw a lot of incredible stuff in 2016.

Jarobi: Kanye has to be #2, then.

DM: Kanye’s another thing though. Kanye is a spectacle. I’ve been lucky enough to see all his tours…

Jarobi: But the Pablo tour, were you there?

DM: Yeah for sure.

Jarobi: Fuck, you kidding me? That’s gotta be #2 if .Paak is #1!

DM: I hold Kanye to a different measure. That’s like arena spectacle art as opposed to club-bangin’ show.

Jarobi: I hear you.

DM: What did you think of the Pablo record?

Jarobi: There’s some really strong stuff on there. I like it.

DM: And Anderson .Paak, by way, is like all four of you from Tribe at once up there! (laughter) And what about your record, is there a favourite track of yours on there?

Jarobi: It changes all the time. I love “Mobius.” The Busta Rhymes verse — ha! And I love “Conrad Tokyo.” And “Dis Generation.”

DM: For sure “Dis Generation” is a gem. And “Whatever Will Be.” The whole album is beautiful, man. “Black Spasmodic” is my favourite jam that right away jumped out. Before I even caught what it was about. (Author’s note: Q-Tip essentially channels the spirit of Phife Dawg on his verse. No lie.) Granted, you aren’t on it.

Jarobi: Lemme tell you something: Tip destroyed that song. Just destroyed it. Good lord.

DM: So Tip keeps alluding to future plans here and there in the press but it’s all a bit ambiguous for now. Where do you stand on the idea of a tour?

Jarobi: Um, I mean, it’s possible.

DM: Last time we spoke and you remained ambiguous and next thing you know albums were happening. I’ll take a “we’ll see” from you to the bank, personally.

Jarobi: I mean we gotta do one show, or something.

DM: One would hope…one hopes Osheaga 2017, ahem.

(laughter)

DM: I mean we talked about 2016 some and one good thing was, it was a banner year for hip hop. Your close contemporaries and friends De La Soul dropped this summer for the first time in 12 years with The Anonymous Nobody. What did you think?

Jarobi: It’s dope! My favourite joint on there, believe it or not, is the one with 2 Chainz.

DM: Yeah man. That joint “Pain” with Snoop, too — that’s one of my jams of the year.

Jarobi: I love the record man. It’s like, I dunno what people expect from groups like Tribe and De La. We just always gotta be true to ourselves and who we are as people. That said, you can’t expect us to make a record at 45 that we would make at 25. That would be idiotic. Or just try to sound like something new. It doesn’t make sense. But it’s not the ’90s no more. ■

A Tribe Called Quest’s We Got It From Here…Thank U For Your Service is available everywhere. See our b2b feature review of the record here.

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/michael-nirenberg/conversation-with-phife-d_b_8904144.html

Conversation With Phife Dawg of a Tribe Called Quest

Enjoy.

MN: Hey Phife. How are you?

PD: What up, man?

MN: So uh, I like the Dear Dilla video

PD: Thank you.

MN: I was wondering, what was your relationship with him like?

PD: Mmm-wow. He was just a good friend, producer- know what I mean? The whole get together with him was meeting him on tour in I believe was 96. Was it 96? Actually a little earlier than that. 1994- Lollapalooza. We had a show out in Detroit. That’s when I first met him and Q-Tip loved his beats. We all loved his beats. He became part of Q-Tip and Ali’s production team. So he was just amazing with the beats, and he was an even better person, know what I mean? Me and him got real close through the years. That was basically the relationship. It didn’t always have to be about work and music, just hanging out and vibing.

MN: That’s really cool. So why do the video now? I feel as if this song is something of an open letter to him.

PD: Right, that’s exactly it. I took my time with it because so many people were doing different dedications to him and stuff like that, so I just took my time with it. There was also a time when I wasn’t thinking about doing music anymore. I was looking at maybe produce for people more or whatever. So that’s why it took so long.

MN: Was this after Tribe broke up the first time? When you decided you didn’t want to do music anymore?

PD: Right. That was probably like 2002. I figured I wasn’t going to mess with it too much.

MN: I wanted to talk to you about that time because I really liked the solo record. To go back to the video, real quick was that Ali playing the doctor?

PD: (laughs) Yeah it was.

MN: (laughs) Yeah, I caught that on the second time I watched it. I also noticed in the video you make some lighthearted jokes about your diabetes. I like that you’re making fun of it and being playful about it. How does it affect your work these days?

PD: Umm, it doesn’t really affect it. I have been diabetic since I was 19, so I can’t say it affects my work, but when I decided I didn’t really wanna do music anymore I guess it affected it then. You know, I wasn’t really into it. You know what I mean?

MN: Every interview I’ve read with you, people just ask you a million questions about Tribe Called Quest. I wanted to talk about other things like the solo record you did in 2000. Did you like the process of doing this? Did you prefer being in a group? As far as I know, you only did the one.

PD: I like both. But at the time I wasn’t in the greatest place. You know in this industry timing is everything. Know what I’m saying?

MN: Yeah.

PD: So I do wish I could do it over, but I thought it was a cool album. I just wish the timing was different. Like I said, I like both. I like being in the group because we weren’t just a group, we were friends before that know what I’m saying?

MN: Right.

PD: It wasn’t like it was a group that was put together on a whim, know what I mean?

MN: You can tell that the vibe between you guys even on the tracks. You can tell when something is the real thing. You feel it. It’s more visceral you know?

PD: Right. Doing a group album is a lot of fun because I know them like the back of my hand.

MN: That’s cool. And brothers fight. When people are that close they get into fights. You guys are gonna be together forever even if you’re not in a group.

PD: Right.

MN: I know you are putting out an EP. Why so long between solo joints?

PD: Like I said, I didn’t think I wanted to do music anymore.

MN: For that long?

PD: So I left it alone for the longest. Plus I had my health issues as well.

MN: What brought you back around?

PD: Just a love for beats, a love for lyrics. I just felt it was that time.

MN: Yeah- I guess it has to be something you totally feel. You can’t fake it.

PD: Exactly, yup.

MN: A little about Tribe- where do you stand today? I know it’s always a changing thing. I saw that Ali is in the video so you must be tight with him. You guys getting along?

PD: Yeah, we all good. We’re not working together right now, but we friends.

MN: That’s good to hear. Tell me a little bit about the EP that’s coming out.

PD: It’s basically just really simple man. Hip-hop 101. The way it was, the way it should always be. Its got a lot of bounce to it. It’s just hip-hop. Period. No more, no less.

MN: That’s what I like; I tend to gravitate towards rap that has a lot of rapping in it. I made this joke recently where I said a lot of contemporary rap doesn’t have a lot of rapping in it and I miss it.

PD: Mm-hmm

MN: So that’s cool man. Who is doing the beats with you?

PD: I did some, my DJ did some: Rasta Roots. I got a beat from Crisis. I got a beat from 9th Wonder. Got a beat from Dilla. Who am I missing? I can’t even think right now, know what I mean? So there are some things on there most definitely. Oh! And Knots the Ruler.

MN: Are there plans for a full-length record?

PD: The EP is called “Give Thanks” and the LP is gonna be called “Mutty-morphoses”.

MN: Let’s talk a little bit about hip-hop. Being around as long as you have, where do you think hip-hop is at in this moment? I know there are lots of artists doing a lot of different stuff.

PD: You know, life is a cycle I believe. It’s going to come back around to what it was. But as far as hip-hop is right now, it’s ok- not the greatest. It’s just ok. I don’t think people honor they craft like Big Daddy Kane, Jay-Z, Eminem, or Ultramagnetics, you know what I’m saying?

MN: Yeah.

PD: Who else? Like Public Enemy, stuff like that KRS, BDP. They don’t really honor they craft like we used to. Everyone made a lane for themselves. No copycat, biting, none of that. Now it’s like the in thing to do because there’s a bunch of laziness going on I think.

MN: I have my own theories about that. I think this sort of started in the late 90’s where the quality started to decline. MC’s started to get lazier- more mush mouthed and I think it had something to do with the rise of southern rap, even though there are excellent MC’s from the south. Generally that’s where I started to lose interest in it and listened to more punk at that time.

PD: Right, right.

MN: What I am noticing now is like a lot of the young kids seem to be bringing the craftsmanship back.

PD: Right. Def.

MN: With the emergence of the Internet there is room for everybody. More different styles.

PD: Absolutely. True.

MN: So I think there’s hope for the kids you know? I’m going to wait on the sidelines and watch. I know you worked with a lot of different people and many quite legendary. I was wondering if there was anyone you would like to work with?

PD: Right, umm. Ghostface. He’s one of my favorites.

MN: He’s fantastic.

PD: He’s one of my favorite MC’s most definitely.

MN: I like the stuff he did with DOOM, who is another fantastic MC. That’s a good answer. Here’s another good one I wrote. In all these years of observing hip-hop, who do you think is the most underrated MC of all time?

PD: (laughs) That’s a good question. I know I’m one of them most definitely.

MN: You are part of a group that is highly lauded.

PD: Yeah I know, I’m still underrated. I’m the “other guy” in the group. Know what I’m saying?

MN: Yeah, I can see that position.

PD: It’s all good. I think Ghostface is underrated. I think GZA is underrated. I’m not really sure why, because those dudes are phenomenal to me.

MN: They kept growing. Many of the MC’s who are like, in their 40’s kept growing and there seems to be this bullshit idea that it’s a young man’s game. It’s kinda stupid. In any other art form you grow. If you’re a painter, writer...

PD: Well, the young men aren’t taking care of it!

MN: (laughs)

PD: Right? They can say it’s a young man’s game all they want. They not taking care of the culture B.

MN: Yeah. Agreed

PD; You know what I’m saying? A lot of half assed shit going on. You know?

MN: Is there anyone you think is carrying the torch right now?

PD: I like Joey Bada$$, J Cole, know what I’m saying?

MN: Especially that first record.

PD: Kendrick, there are others but those three come to mind off top.

MN: That’s cool man, I think that’s all my questions I had. Is there anything else you want to bring up to the readers?

PD: Yeah, like I said Give Thanks is the name of the EP and the single is called Nutshell produced by Dilla. Look out for that in 2016.

My awkward grammar has been edited with love and care by Courtney Eddington.

https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-lists/a-tribe-called-quest-20-essential-songs-78373/excursions-1991-158658/

A Tribe Called Quest: 20 Essential Songs

R.I.P. Phife Dawg: Revisit pioneering New York rap crew’s best tracks

By Christopher R. Weingarten

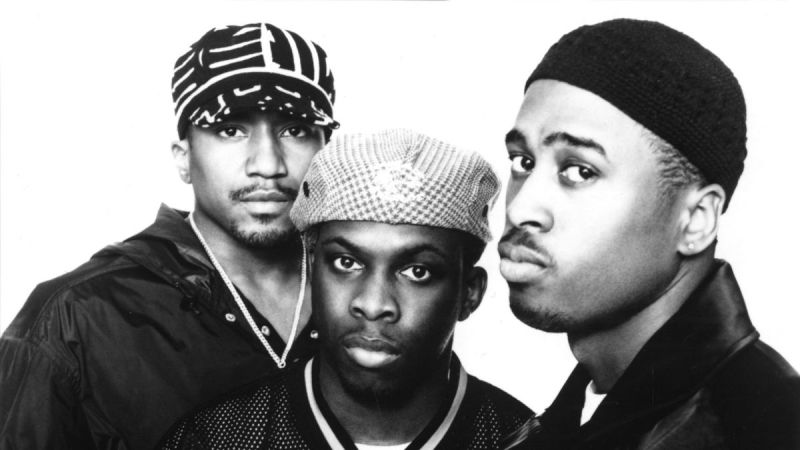

A Tribe Called Quest (L-R): Q-Tip, Phife Dawg, Ali Shaheed Muhammad and Jarobi White. Karl Grant/Photoshot

Through 10 years and a handful of critically adored albums, rappers A Tribe Called Quest went

from spitting fly routines on Linden Boulevard in Queens to mapping out

the electrically relaxed blueprint for wave after wave of abstract

alterna-rap bohemians — laying the footprints for Digable Planets, the

Fugees, Mos Def and Talib Kweli, the Black Eyed Peas, Lupe Fiasco and

even superfan Kanye West. Together, Q-Tip, Phife Dawg, Jarobi and Ali

Shaheed Muhammad cemented the link between jazz’s grooves and hip-hop’s

future funk, provided a show-stealing scenario to launch their friend

Busta Rhymes to fame and incubated a young producer named Jay Dee who

would influence a generation of beatmakers on his own. A freewheeling

trip of Lou Reed licks, tales of lost wallets, giddy scratching, Ron

Carter bass assists and salty punchlines, their body of work was like

nothing hip-hop had seen before, or has since. In remembrance of Phife

Dawg, who passed away Tuesday at age 45, here are the pioneering rap

group’s 20 essential tracks.

“Excursions” (1991)

The opening track of the jazz-flecked The Low End Theory

was one of hip-hop's great statements of purpose, with the crew

connecting musical dots between different eras of radical music. Q-Tip

took a 6/8 hard-bop lick from Jazz Messengers bassist Mickey Bass and

flipped it until it bounced along in hip-hop's funky 4/4. Tribe

sample O.G. hip-hop pioneers the Last Poets "("time is running and

passing, passing and running") the same way that avowed Tribe fan Kanye

West would use Gil-Scott Heron at the end of My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy.

In Q-Tip's lyrics, rap is like the bebop that Q-Tip's dad listened to,

Bobby Brown is amping like Michael, and the abstract poet is prominent

like Shakespeare or Langston Hughes.

"There were a couple of other groups that were sampling jazz at that time," Ali Shaheed Muhammad told Nextbop.com. "Gang Starr, Pete Rock and C.L. Smooth, Main Source … but I think the way that we delivered it was in such a way that had not really been done." As Q-Tip told Brian Coleman in Check the Technique: "At the time, there were some things happening in hip-hop, sonically, that I wanted to expand on, especially with the bottom. … I would always explain how dynamic I wanted things to be by telling Bob [Power, engineer], 'I want this to be more at the bottom, at the low end.' I guess it was a lack of articulation but it got the job done. And that's where the title came from."

"There were a couple of other groups that were sampling jazz at that time," Ali Shaheed Muhammad told Nextbop.com. "Gang Starr, Pete Rock and C.L. Smooth, Main Source … but I think the way that we delivered it was in such a way that had not really been done." As Q-Tip told Brian Coleman in Check the Technique: "At the time, there were some things happening in hip-hop, sonically, that I wanted to expand on, especially with the bottom. … I would always explain how dynamic I wanted things to be by telling Bob [Power, engineer], 'I want this to be more at the bottom, at the low end.' I guess it was a lack of articulation but it got the job done. And that's where the title came from."

“Check the Rhime” (1991)

On the first single from ATCQ's seminal The Low End Theory, Q-Tip and Phife Dawg reminisce about their pre-fame days as teenagers spitting in ciphers on Linden Boulevard in the Jamaica neighborhood of Queens. A slightly accelerated looped rhythm from Minnie Riperton's "Baby, This Love I Have" sets a casual, laid-back mood, with Phife spitting verses as if he were lounging in the afternoon sun, swatting away rivals like flies. "A special shout of peace goes out to all my pals, you see/And a middle finger goes to all you punk MCs," he raps. It's also an assertion of Phife's primacy as a rapper. Some doubted his talent after his halting verses on People's Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm, but here, he quickly proves himself Q-Tip's lyrical equal.

“Jazz (We’ve Got)” (1991)

The lovely cool-out vibes of "Jazz (We Got)" stem from a tantalizing collaboration between ATCQ and Pete Rock that never came to fruition. One of the potential backing tracks was a Pete Rock arrangement of Jimmy McGriff's "Green Dolphin Street." "Pete had come up with that beat, but the song we were going to do never materialized," Q-Tip told Brian Coleman for the latter's 2005 book Rakim Told Me. "I already had the record he used, but I wanted to get his permission. He was like: ‘Yeah, go ahead.'" Pete Rock isn't mentioned as a co-producer in the Low End Theory credits, but Q-Tip gives him a shout-out at the end of "Jazz." Meanwhile, a lyrical stray shot from Phife Dawg — "Strictly hardcore tracks, not a New Jack Swing" — raised the ire of Teddy Riley protégés Wreckx-n-Effect, best known at the time for the lame pop-rap hit "New Jack Swing" (and, later, the even worse "Rump Shaker"). Wreckx-n-Effect exacted revenge for Phife's diss by surrounding Q-Tip at a 1993 Naughty by Nature concert and punching him in the eye. The Zulu Nation and the Nation of Islam subsequently negotiated a truce between the two.

“Buggin’ Out” (1991)

Those familiar with the video for "Jazz (We Got)" — see above — will recall that the song abruptly ends at the 3:30 mark. Phife Dawg then says, "Yo, check this out," and the black-and-white A-side shifts into the primary colored B-side, "Buggin' Out." "Microphone check, one-two, what is this?" rhymes the five-foot assassin with the ruffneck business over a live-and-direct Ron Carter bass line. Phife's second "Buggin' Out" verse is even better as he reveals how being in overcrowded New York can get overwhelming "like a migraine pounding," despairs about riding on the train "with no dough" and admits that sometimes he just wants to be alone. "I had a twin brother that died at birth so I was a lonely child sometimes, but that loneliness helped me out a lot," Phife told The Source in 1993. "I'd be in the bathroom showering when I was mad young, and the rhymes would just be coming."

“Scenario” feat. Leaders of the New School (1992)

This was the song that kickstarted a brief yet glorious era of

rah-rah fast rap: Tribe and Leaders of the New School chanting "so

what's so what's so what's the scenario" at the top of their lungs, and

then blasting us with one killer verse after another. Phife Dawg was the

leadoff batter who sparked the session, and his line "bust a nut inside

your eye/To show you where I come from" was so visceral that cable

networks eventually censored it from broadcasts of the ensemble's

classic video. "My days of paying dues are over/Acknowledge me as in

there," he rhymes. Ya goddamn right he's in there.

“Scenario (7 M.C.’s Remix)” feat. Kid Hood, Leaders of the New School (1992)

For the B-side of their iconic single, A Tribe Called Quest refitted "Scenario" with a new beat, new lyrics and the same all-star cast. One addition was the debut recording of roughneck MC Kid Hood, whose "pump slugs in your face and dump that ass in the river" style stood in stark contrast to the electrically relaxed Tribe and the cheeky Leaders, but whose gift for rhymes was unquestionable. Days after recording the track, he was shot and killed in Harlem, leaving the "Scenario" remix the lone recorded appearance of this promising MC. "When I first met him, he was rhymin'" Q-Tip told The Source. "He didn't say hello or nothin', he just started rhymin'. … He really seemed like he was sold on coming out and working hard. The day we taped, he went in the studio, took his shirt off, and went in the booth. He did it in one take." Though Kid Hood wouldn't live to make another song, his voice would live on: His "I'm a bad, bad man" quip was sampled extensively on Notorious B.I.G.'s Ready to Die.

“Hot Sex” (1992)

As hard as Tribe comes. The first track after The Low End Theory (surfacing originally on the Boomerang soundtrack) ditched bassy semi-acoustic jazz-funk for slamming, stripped down electronics, with a beat that's as nasty as the title suggests, built off a looped sample of Lou Donaldson's "Who's Making Love." Phife and Tip step to suckers with all the nasty swagger they can summon: "I'm not Lawn Doctor so just step off with the ho," Phife spits, while Tip boasts that "the poems that I create are for hookers and the crooks," donning a creepy mask in the video to hide the shiner that Wreckx-n-Effect had just given him for seeming to diss New Jack Swing on "Jazz (We've Got)."

“Award Tour” (1993)