"I like Geri Allen. I listen to a lot of Geri Allen."

--Mal Waldron 1925-2002

SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2018

VOLUME FIVE NUMBER TWO

GERI ALLEN

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

TOMEKA REID

(January 27--February 2)

FARUQ Z. BEY

(February 3--9)

HANK JONES

(February 10--16)

STANLEY COWELL

(February 17–23)

GEORGE RUSSELL

(February 24—March 2)

ALICE COLTRANE

(March 3–9)

DON CHERRY

(March 10–16)

MAL WALDRON

(March 17–23)

JON HENDRICKS

(March 24–30)

MATTHEW SHIPP

(April 1–7)

PHAROAH SANDERS

(April 8–14)

WALT DICKERSON

(April 15–21)

Mal Waldron

(1925-2002)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

A pianist with a brooding, rhythmic, introverted style, Mal Waldron's playing has long been flexible enough to fit into both hard bop and freer settings. Influenced by Thelonious Monk's use of space, Waldron has had his own distinctive chord voicings nearly from the start. Early on, Waldron

played jazz on alto and classical music on piano, but he switched

permanently to jazz piano while at Queens College. He freelanced around

New York in the early '50s with Ike Quebec (for whom he made his recording debut), Big Nick Nicholas, and a variety of R&B-ish groups. Waldron frequently worked with Charles Mingus from 1954-1956 and was Billie Holiday's regular accompanist during her last two years (1957-1959). Often hired by Prestige to supervise recording sessions, Waldron contributed many originals (including "Soul Eyes," which became a

standard) and basic arrangements that prevented spontaneous dates from

becoming overly loose jam sessions

After Holiday's death, he mostly led his own groups, although he was part of the Eric Dolphy-Booker Little Quintet that was recorded extensively at the Five Spot in 1961, and also worked with Abbey Lincoln

for a time during the era. He wrote three film scores (The Cool World,

Three Bedrooms in Manhattan, and Sweet Love Bitter) before moving

permanently to Europe in 1965, settling in Munich in 1967. Waldron, who has occasionally returned to the U.S. for visits, has long been a major force in the European jazz world. His album Free at Last was the first released by ECM, and his Black Glory was the fourth Enja album. Waldron, who frequently teamed up with Steve Lacy

(often as a duet), kept quite busy up through the '90s, featuring a

style that evolved but was certainly traceable to his earliest record

dates. Among the many labels that have documented his music have been

Prestige, New Jazz, Bethlehem, Impulse, Musica, Affinity, ECM, Futura,

Nippon Phonogram, Enja, Freedom, Black Lion, Horo, Teichiku, Hat Art,

Palo Alto, Eastwind, Baybridge, Paddle Wheel, Muse, Free Lance, Soul

Note, Plainisphere, and Timeless. In September of 2002, Waldron

was diagnosed with cancer. Remaining optimistic, he continued to tour

until he passed away on December 2 in Brussels, Belgium at the age of

76.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/malwaldron

Born in New York City, Waldron's jazz work was chiefly in the hard bop, post-bop and free jazz genres. He is known for his distinctive chord voicings and adaptable style, which was originally inspired by the playing of Thelonious Monk.

After obtaining a B.A. in music from Queen's College, New York, he worked in New York City in the early 1950s with Ike Quebec, “Big” Nick Nicholas, and rhythm and blues groups. He worked frequently with Charles Mingus from 1954 to 1956 and was Billie Holiday's regular accompanist from 1957 until her death in 1959. He also supervised recording sessions for Prestige Records, for which he provided arrangements and compositions (including the jazz standard “Soul Eyes”). After Holiday's death he chiefly led his own groups.

Waldron had a unique playing style. He played chords in a lower bass part of the keyboard, and is comparable to Bud Powell in his dissonant voices. His solo style is in noted contrast to players like Red Garland.

He was frequently recorded, both as a leader and sideman, with, among others, John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, Clifford Jordan, Booker Little, Steve Lacy, Jackie McLean and Archie Shepp.

Besides performing he composed for films (The Cool World, Three Bedrooms In Manhattan and Sweet Love Bitter), theatre, and ballet. In 1963 he had a major nervous breakdown, and had to re-learn his skills, apparently by listening to his own records. Waldron's playing style re- emerged more brooding, starker and percussive, combining bebop and avant-garde melodies, and at times weaving repetitive melodic motifs using just a few notes over a drone like accompaniment figure. After working on a film score in Europe he moved there permanently in 1965 initially living in Munich, Germany and in his last years he was based in Brussels, Belgium. On the principle that working at local venues reduced his fee, he avoided playing in the city in which he lived. He regularly returned to the United States for bookings.

Through the 1980s and 1990s he worked in various settings with Steve Lacy, notably in soprano-piano duets playing their own compositions as well as Monk's.

After some years of indifferent health, though continuing to perform, Waldron died in December 2002 in Brussels, Belgium.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/malwaldron

Mal Waldron

Mal Waldron

Born in New York City, Waldron's jazz work was chiefly in the hard bop, post-bop and free jazz genres. He is known for his distinctive chord voicings and adaptable style, which was originally inspired by the playing of Thelonious Monk.

After obtaining a B.A. in music from Queen's College, New York, he worked in New York City in the early 1950s with Ike Quebec, “Big” Nick Nicholas, and rhythm and blues groups. He worked frequently with Charles Mingus from 1954 to 1956 and was Billie Holiday's regular accompanist from 1957 until her death in 1959. He also supervised recording sessions for Prestige Records, for which he provided arrangements and compositions (including the jazz standard “Soul Eyes”). After Holiday's death he chiefly led his own groups.

Waldron had a unique playing style. He played chords in a lower bass part of the keyboard, and is comparable to Bud Powell in his dissonant voices. His solo style is in noted contrast to players like Red Garland.

He was frequently recorded, both as a leader and sideman, with, among others, John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, Clifford Jordan, Booker Little, Steve Lacy, Jackie McLean and Archie Shepp.

Besides performing he composed for films (The Cool World, Three Bedrooms In Manhattan and Sweet Love Bitter), theatre, and ballet. In 1963 he had a major nervous breakdown, and had to re-learn his skills, apparently by listening to his own records. Waldron's playing style re- emerged more brooding, starker and percussive, combining bebop and avant-garde melodies, and at times weaving repetitive melodic motifs using just a few notes over a drone like accompaniment figure. After working on a film score in Europe he moved there permanently in 1965 initially living in Munich, Germany and in his last years he was based in Brussels, Belgium. On the principle that working at local venues reduced his fee, he avoided playing in the city in which he lived. He regularly returned to the United States for bookings.

Through the 1980s and 1990s he worked in various settings with Steve Lacy, notably in soprano-piano duets playing their own compositions as well as Monk's.

After some years of indifferent health, though continuing to perform, Waldron died in December 2002 in Brussels, Belgium.

Free At Last

Mal Waldron’s ecstatic minimalism.

by Adam Shatz

July 26, 2017

The Nation

Adam Shatz dedicates this essay to the memory of Geri Allen.

Mal Waldron performing in Amsterdam in 1995.

(FransSchellekens / Redferns)On July 17, 1959, Frank O’Hara, shaken by the news of Billie Holiday’s death, wrote a poem, “The Day Lady Died.” In the last two lines, he remembers leaning against the bathroom door at the Five Spot, a jazz club in the East Village, “while she whispered a song along the keyboard / to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing.” Seldom has the power of jazz performance been conveyed with such speed and grace. Holiday and Waldron, her pianist, are having a conversation so quiet and so intimate that listening to it feels like eavesdropping. I have always loved this poem for what it reveals not only about Holiday’s stagecraft, but also about her affection for Waldron, who accompanied her from 1957 until her death. Holiday and Waldron were close friends as well as collaborators. Waldron helped her write the autobiographical ballad “Left Alone,” an account of romantic desolation that she never had the chance to record. He had known of Holiday’s addiction, but, as he put it, “Lady Day had an awful lot to forget,” and his debt to her was incalculable. She taught him the importance of a song’s lyrics: Words, as much as notes, could lend themselves to musical improvisation. The magic she worked with them rubbed off. To listen to Waldron is to feel as if he is speaking to you, and only you, because he never forgets the lyrical content of a song.

Waldron was 33 when Lady died. He would live another 44 years, but for many jazz fans he would always remain Holiday’s accompanist. He frequently recorded her songs, spoke of their friendship in interviews, and insisted that if she had moved to Europe, as he did, she would have lived a much longer life. Waldron’s devotion to her memory reflected not only his love for her, but also the knowledge that he had been given a second chance: Four years after her death, he survived a near-fatal nervous breakdown after a heroin overdose. He experienced his survival as a rebirth, but was left with a piercing sense of life’s fragility. “When you take our life span and measure it against eternity it is only a small dot,” he wrote. “In this time we must realize, if possible, our fullest self potential.”

Waldron used his time well, creating one of the most distinctive bodies of work in postwar music. He wrote hundreds of songs, most famously “Soul Eyes,” a lush 32-bar ballad dedicated to John Coltrane (who liked it so much that he recorded it no fewer than three times). Waldron had a big sound and loved the resonances of his instrument, but he worked almost exclusively in small-group settings, preferring their chamber-like intimacy to larger, brassier ensembles. The best way to hear him is either in a duet with one of his favorite partners (his recordings with the saxophonists Steve Lacy and Marion Brown are especially memorable) or by himself.

BOOKS IN REVIEW

The Opening

By Mal Waldron

Meditations: Live at Dug

By Mal Waldron

Waldron was a lifelong student of classical piano—he often played sonatas for pleasure, and recorded pieces by Chopin, Brahms, Satie, and Bartók—and he brought a classical sense of form and introspection to his solo work. Two long-out-of-print solo-concert albums—The Opening and Meditations—were recently reissued, and they bear witness, in different ways, to the dark, wintry beauty of Waldron’s art. The Opening, a fiery 1970 concert at the American Cultural Center in Paris, features six original compositions, mostly based on ostinatos—vamps that Waldron plays over and again—with small but engrossing variations in tempo, dynamics, timbre, and rhythmic articulation. (One is called “Of Pigs and Panthers,” an allusion to the war back home between the police and the Black Panther Party.) Meditations, recorded two years later at a jazz club in Tokyo, is a more contemplative affair, bookended by two of Waldron’s best-known pieces on solitude, “All Alone” and “Left Alone.”

Waldron’s style is invariably described as “brooding”—almost all of his pieces are in a minor key—but it could also be described as analytical. Most jazz pianists work to create an effect of outward motion when they improvise. Swing, after all, is a musical analogue of dance, and its aim is to make the body more expansive and supple. Waldron’s music appears to work in nearly the opposite direction, burrowing ever more deeply into its materials: He seems to be on an inward journey. In “The Blues Suite,” for example, the slow, winding song that takes up more than a third of Meditations, there’s an extraordinary moment where Waldron plays a descending figure in the lower registers of the piano; as it recedes, a sample from the Negro spiritual “Wade in the Water” rises in its wake, suggesting a shadowy recollection, or the previously erased layer of a palimpsest.

Waldron “played every piece as if he were X-raying it,” as Edward Said once observed of Glenn Gould. He turned to music as a kind of mental exercise, a way of figuring out what he thought; his pieces were almost all “meditations.” “I want to be able to see what I am doing,” he explained, “and in order to be very clear in my mind where I am going I have to repeat it.” His search for what he called the “one note that goes for the entire piece” gives his music an almost uniquely obsessive sense of propulsion—the feeling of being in a trance.

The son of West Indian immigrants, Malcolm Waldron was born in 1925 in Harlem and moved shortly after with his family to Jamaica, Queens. His father worked for the Long Island Rail Road and his mother was a nurse; both were middle-class strivers. They wanted, as Waldron later recalled, to “keep me off the streets” and forced him to take piano lessons from the age of 6. He was a quick study: “Fear is a great motivator,” he said.

Waldron was drafted into the Army in 1943 and was stationed at West Point, where he worked in the equestrian services. Whenever he was on leave, he made the scene, going to the clubs on 52nd Street and in Harlem, where he heard the pianists Art Tatum and Bud Powell, both of whom would be important influences. After the war, Waldron enrolled at Queens College on the GI Bill. There, he studied composition with Karol Rathaus, an exiled Jewish Austrian composer who recoiled from the orthodoxies of both tonal music and Schoenbergian serialism. Rathaus was also an admirer of jazz and the author of an essay, “Jazzdämmerung?” (“The Twilight of Jazz?”), that accused George Gershwin and the swing-band leader Paul Whiteman of “cultural larceny” for Europeanizing black music.

Under Rathaus’s tutelage, Waldron listened to Bach, Stravinsky, and Ravel; he also began to write his first scores. In the evenings, he received a different sort of education at the Paradiso, a Harlem club not far from Minton’s Playhouse, headquarters of the bebop movement. At the time, Waldron was playing alto saxophone, not piano: He had picked up the horn after hearing Charlie Parker, whom, like other young bop musicians, he worshipped. By his mid-20s, however, he’d returned to the piano. The saxophone, he realized, was “a very exhibitionist instrument, and you had to be extroverted, and I was very introverted.” In A Portrait of Mal Waldron, a 1997 documentary by the Belgian filmmaker Tom Van Overberghe, Waldron describes how the piano allowed him to hide, to “play very quietly and work out your changes. It’s a very beautiful instrument for a person like me.”

In the early 1950s, Waldron paid his dues in a style of music that could hardly have been less introverted, accompanying soul-jazz bands led by the down-home saxophonists Ike Quebec and George Walker “Big Nick” Nicholas. But he was also studying the work of bebop’s most original pianist and composer, Thelonious Monk. At first, Monk’s style sounded, to Waldron, “so strange, the way he hit the piano,” but “it just grew on me,” and he became one of the few pianists to absorb Monk’s innovations—his flat-fingered attack; his way of “bending” notes by striking two adjacent keys but only releasing one; his radical use of space—without sounding like a Monk imitator.

Waldron’s ability to combine Bud Powell’s fleet, lyrical approach to “comping”—the art of playing behind a soloist—with Monk’s more angular and idiosyncratic style made him a favorite pianist of the most sophisticated hard-bop musicians. Charles Mingus recruited him in 1954 to his Jazz Workshop and featured him on his landmark 1956 album, Pithecanthropus Erectus. The same year, Waldron was hired as the house pianist at Prestige Records, where he played on albums by Jackie McLean, John Coltrane, and other stars of the era. A young father, Waldron also had to find other work, and he supported his family by laying down tracks for Music Minus One, a maker of sing-along and play-along records. Each morning, he reported for work at Music Minus One in a suit and tie, looking more like an accountant than a musician. At night he was out gigging, sometimes with Billie Holiday; sometimes with the many reedmen who appreciated his discreet yet forceful comping; and sometimes with beatniks like Allen Ginsberg and Lenny Bruce.

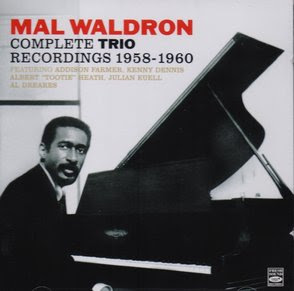

But Waldron hungered for something more than work as a sideman. A talented sheet composer, he wanted to write his own music. While he was careful to avoid the often arid contrivances of third-stream jazz, he shared its ambition to incorporate classical compositional ideas into jazz, and to move beyond the formulaic theme-solos-theme structure of hard bop. His 1959 album Impressions, a trio recording with Addison Farmer on bass and Albert “Tootie” Heath on drums, was his first great statement as a leader, revealing a probing young modernist composer and a daring improviser. Holiday’s influence can be keenly felt in his reading of Jimmy van Heusen’s “All the Way,” a song she loved, and in Waldron’s own composition, “Overseas Suite,” which was inspired by his recent European tour with her.

But in Impressions we also hear the accompanist emerging from Lady’s shadow. In it, Waldron depends less on chord changes—the foundation of bebop improvisation—than on clusters of notes and “whatever enriches the sound.” He was somewhat more tentative than Miles Davis and Ornette Coleman, both of whom released revolutionary albums in 1959, Kind of Blue and The Shape of Jazz to Come. But Waldron was just as eager to embrace the new freedoms. As he saw it, they went hand in hand with being a black musician in the era of civil rights. The bar lines in a song were, he recalled, like “going to jail for us.” “We were talking about freedom, and getting out of jails…. So everyone wanted to escape from that.”

Waldron cut an alluring figure for the new jazz modernism emerging in the 1950s: He was slender, with regal features, an elegant bearing, and haunting eyes. Along with Sidney Poitier and Miles Davis, he was one of the original black male sex symbols of the 1950s, a precursor of the “Black is beautiful” era. On the cover of Impressions, Waldron, wearing a suit, tie, and rain jacket, stands behind a ladder against a dark, purple-tinted backdrop. He looks backward, with a somewhat nervous expression: an image of the dissident energies gathering force at the end of the Eisenhower era.

Billie Holiday died a few months after Impressions was released. Waldron was devastated. She was his young daughter’s godmother, and “such a warm person I began to feel she was like my sister.” A year later, Waldron released Left Alone, a tribute to Holiday’s work, whose title track featured a gorgeous performance by Jackie McLean. Released from his duties as an accompanist, Waldron began over the next few years to come into his own. He played a historic two-week date at the Five Spot with one of the most exciting bands of the 1960s, a quintet led by the multi-reedman Eric Dolphy and the trumpeter Booker Little, which also featured the drummer Ed Blackwell (of the Ornette Coleman Quartet) and the bassist Richard Davis. He also contributed to some of the great civil-rights jazz albums made by the drummer Max Roach and his partner, the singer Abbey Lincoln. (Waldron wrote the music to Lincoln’s protest song “Straight Ahead,” in which she sang, with bitter eloquence: “If you got to use the back roads / Straight ahead can lead nowhere.”) He demonstrated his gifts as a composer of small-ensemble jazz on the ambitious 1961 album The Quest, which explored waltzes, ballads, bop syncopation, even 12-tone serialism. The modal composition “Warm Canto,” a miniature jewel that showcased Dolphy’s clarinet and Ron Carter’s pizzicato work on cello, looked forward to the epic tone poems Waldron would write in the 1970s. On The Quest, he also developed what the singer Jeanne Lee later described as his “orchestral way of hearing.”

But Holiday’s death caught up with him—or rather, her habits did. Waldron had been horrified to see the Lady “treated like a criminal” rather than the victim of a disease, an experience that “broke her down.” It broke him down, too. Many Americans assumed that he must be a drug addict, simply because he was a jazz musician, and “it got to the point where if you had the name you just had to have the game, too.” In 1963, while on tour with Roach and Lincoln, he went onstage loaded on heroin, and froze. For the next six months, he was hospitalized at East Elmhurst Hospital and subjected to shock therapy and spinal taps. He could scarcely remember who he was, much less how to play piano. Yet he was grateful: The alternative was worse. And in the wake of his overdose and nervous breakdown, Waldron bit by bit began to come back to life.

Related Article:

An Argument With Instruments: On Charles Mingus

His hands trembled, and he had lost his sense of time. But he applied himself with diligence, listening to his recordings and writing out his earlier improvisations on paper. His work as a composer of sheet music would sustain him for the next two years, until he was ready to perform again. He wrote scores for Shirley Clarke’s The Cool World and Herbert Danska’s Sweet Love, Bitter (loosely inspired by Charlie Parker’s last years, and starring Dick Gregory). But there were rumors that he was dead, and Waldron wasn’t sure they were false. He was surrounded by casualties of the jazz life: Booker Little had died of kidney failure, at 23, in 1961; three years later, Eric Dolphy died, at 36, of an undiagnosed diabetic coma in a Berlin hospital, where doctors mistook him for a drug addict and left him in bed so the drugs could run their course.

During these years, work in the New York clubs became increasingly hard to come by because, as he recalled, “the white musicians got the jobs, and the black musicians didn’t get the jobs even if they had more talent.” When Marcel Carné, the director of Le Jour Se Lève, asked him to come to Paris to write the soundtrack for his Three Bedrooms in Manhattan, an adaptation of a moody 1946 novel by Georges Simenon, he had no trouble making up his mind. “In America if you were black and a musician at the time, it was two strikes against you,” Waldron said. “In Europe…it was two strikes for you.” He found “so much respect and love” there that he “didn’t need any drugs.”

Waldron flew to Paris in 1965 and never looked back. He didn’t return to the States, even to perform, until 1975. After scoring Carné’s film, in which he also made a cameo as a barroom pianist, he bounced around France and Italy before settling, in 1967, in Munich. Two years later, he released one of his most important albums, the trio recording Free at Last, which also launched a new, Munich—based label, Editions of Contemporary Music (ECM), founded by a young German bassist, Manfred Eicher, who would become one of the great champions of the American jazz avant-garde.

On Free at Last, we hear a musician who has emancipated himself not only from America but from the overbearing influence of his mentors, particularly Bud Powell. Waldron’s writing is simpler, stripped down to vamps of a few notes, “calls” designed to provoke improvisatory responses. Before the breakdown, he explained, he had “started out with a big tree and I tried shaving and shaving and shaving…to find the perfect toothpick, but…I was nowhere near the toothpick at that moment.” His rhythms, meanwhile, became denser and more complex, his touch harder and more percussive, more “African.” The mood of Free at Last was dark and fierce, radiating identity and purpose. Its idiosyncratic flow came from the drone-like effects that Waldron created by pounding chords with his left hand. They gave the music an expansive sense of space, as if it, too, could breathe more freely in exile.

The jazz historian John Litweiler has characterized Waldron’s post breakdown style as “repetition transformation,” a phrase that may remind some of Steve Reich and Philip Glass, who were experimenting at the same time with repetitive structures in the early works of Minimalism. But Waldron arrived at his version of Minimalism on his own, through sounds and techniques specific to African-American music—above all, the plaintive, ringing sound known as a “blues cry.” An attempt to approximate the sound of a human voice with an instrument, the blues cry is a common expressive flourish in jazz, but Waldron transformed it into a structural device: He repeated it with different shadings, inflections, and intonations throughout his improvisations.

In Free at Last and Black Glory, a thrilling 1971 trio album, there are echoes of the free-jazz pianist Cecil Taylor—for whom Waldron would later write two tributes, “Free for C.T.” and “Variations on a Theme by Cecil Taylor”—but the resemblance reflects kinship rather than influence: Waldron had not left behind hard bop to become anyone’s disciple. Waldron meant “free at last” not only from American racism, or from chord structures, but from any restrictive influences—-including the pianist he had been before his breakdown. One of the reasons that “I feel it necessary to play freer is that I believe no one is ever exactly the same as he was a moment ago,” he explained at the time. “The change from moment to moment can be and usually is very small, almost unmeasurable, but nevertheless it is there. And since I’m definitely not the same person I was five years ago, I cannot pretend that nothing has changed by playing the same old way.”

It’s almost impossible to listen to Free at Last or any of the music that followed without thinking of the trial he had to survive to make it, just as one can hardly listen to The Quartet for the End of Time without reflecting on Olivier Messiaen’s time in a prisoner-of-war camp, or The Basement Tapes without being reminded of Dylan’s motorcycle accident. Survival is essential to its pathos, and to its consolatory power. Here is the sound of a man who has no intention of returning home, who has found not only a sanctuary, but renewal: a “second life,” he called it.

Waldron would continue to explore his newfound freedoms in such rip-roaring anthems as “Sieg Haile” (dedicated to Haile Selassie), “La Gloire du Noir,” and “Snake Out”; but he would also do so in ballads of disarming vulnerability and, not least, in his tributes to his late employer, notably Blues for Lady Day, recorded in 1972 in Holland. His melodic phrasing on the album, particularly in the stark, chilling interpretation of “Strange Fruit,” is slow, stately, and unadorned, as if he were waiting for Holiday to join him. Few purely instrumental albums have been so effective at conjuring the absent lyrics of its songs.

That Waldron not only reinvented himself but produced his greatest music outside of the States, in conditions of comparative dignity and respect, challenges a widespread assumption of jazz history: that the music diminishes in power the further it is removed from its vernacular sources. In 1949, Miles Davis bid farewell to the freedoms of post-liberation Paris to return to a segregated country, because “musicians who moved over there seemed to me to lose something, an energy, an edge, that living in the States gave them.” The unspoken, nostalgie de la boue corollary of this belief is that adversity is the yeast of jazz creativity, that the comforts of expatriate life make musicians go soft. But for many jazz musicians, life abroad has meant exposure to new experiences and ideas. And more than any of his peers, Waldron embraced the perspective of exile within his music. A number of his compositions were postcards from places he had visited; his masterpiece was an ode to flight, inspired by a visit in the early 1970s to the Norwegian island city of Kristiansund, where each morning he had awakened to “watch the seagulls perform a ballet.” He captured their dance in a languid reverie, “Seagulls of Kristiansund,” built around two tone centers, E minor and A minor, recalling the French Impressionist composers he admired.

Like Debussy and Satie, Waldron was drawn to the pentatonic scale and to East Asian aesthetics, whose minimalism and refinement of gesture struck a chord. When he came to Tokyo for the first time in 1970 to record an album, he was already big in Japan, thanks to his 1959 tribute to Billie Holiday, Left Alone, which had been enormously popular there, and he returned many times, recording dozens of albums on Japanese labels. That many of the tunes Waldron wrote in Japan have Japanese titles indicates the strength of his attachment. A “natural mystic,” as the singer Jeanne Lee described him, Waldron felt as if he had been there before, perhaps in a previous life. As it turned out, Japan’s interest in his work meant less to him than his own interest in Japan. “They think I’m here for the gigs, but I’m really here for the temples,” he once told a friend.

Waldron was particularly impressed by Ryoanji (“Temple of the Peaceful Dragon”), a 15th-century Zen Buddhist temple in north Kyoto. Ryoanji is famous for its rock garden, a classical example of karesansui, or dry landscape. Fifteen stones of varying sizes, composed into five groups, lie on a bed of white sand, which is raked each day by monks. The stones are arranged in such a way that only 14 can be seen at once; according to a proverb, only through attaining wisdom can one see the elusive 15th stone. For some, the garden depicts a group of islands floating on an ocean; for others, a mother tiger transporting her cubs over the sea. In its understated play of sameness and difference, movement and serenity, symmetry and asymmetry, Waldron found an analogue to his own music. The garden embodied what in Japanese is called wabi-sabi, an aesthetic of refined austerity, based on the beauty of imperfection and the acceptance of transience. John Cage, who first visited Ryoanji in 1962 with Yoko Ono and the pianist David Tudor, produced a series of compositions inspired by it, as well as dozens of drawings.

Waldron’s tribute, “The Stone Garden of Ryoanji,” on the recently reissued Meditations, was recorded in July 1972 at the Dug, a club in Tokyo. Located in the basement of an old building between two high-rises, the Dug was a sanctuary for music lovers, writers, and bohemians; it was the kind of place where, as a young woman in Haruki Murakami’s novel Norwegian Wood remarks, “They don’t make you feel embarrassed to be drinking in the afternoon.” The song begins with a simple, almost childlike theme, suggestive of Japanese folk music as filtered through Satie, but it moves into a richly involving set of blues variations, examined and observed from every conceivable angle, as if Waldron were in search of the invisible 15th stone. Its beauty comes from the rapt, almost relentless attention to melodic line that was Waldron’s signature, and because the song won’t let him go, it won’t let us go, either. Much of the music that Waldron made in Japan in the early 1970s can be heard as the expression of an impossible farewell, “forecasting my feelings about leaving this island paradise,” as he wrote of his ballad “Sayonara,” which appeared on his 1970 album Tokyo Reverie.

A self-described “born gypsy,” Waldron was used to farewells. He spent most of his time on the road, returning now and then to Munich and Brussels, where he moved in the late 1980s. But Japan would always have a special claim on his imagination, and he went there as often as he could. He met his second wife, Hiromi, with whom he had three children, on a visit to Tokyo in the early 1980s. And in 1995, he went to Japan on an official invitation for the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He was joined by the entire Waldron clan, including Hiromi’s two children from her first marriage; his first wife, Elaine; and their two adult daughters. Waldron performed in a trio with Jeanne Lee and the flutist Toru Tenda at temples, concert halls, and community centers from Tokyo to Okinawa. Lee, in her liner notes to Travellin’ in Soul-Time, the album that came out of this tour, remembers that “at one point, there were more Waldrons on the train than other passengers.”

Like John Coltrane, who visited Japan in 1966, Waldron was overwhelmed by the Hiroshima Peace Memorial. It was not just the evidence of destruction but the story it told of resilience, atonement, and rebuilding—one for which, as another kind of survivor, he felt a great affinity. For the 50th anniversary, he composed a suite based on “The White Road,” a poem by Syo Ito, a 14-year-old survivor of Hiroshima, and on Black Rain, a novel by Masuji Ibuse about the radioactive rain that fell after the bombings. The harrowing, almost unspeakable words of the White Road/Black Rain Suite for Improvisers were sung by Lee, with whom Waldron had already made a remarkable duo album of standards, After Hours. It was one of their last performances together: She died in 2000, at 61; he died two years later, at 77.

Not since his work with Holiday had Waldron formed such a close partnership with a singer. An heir of both Holiday and Abbey Lincoln, Lee was the finest singer to emerge from the ranks of the free-jazz movement; she had performed with everyone from Archie Shepp to John Cage, and spent much of her career as an expatriate. Like Waldron, she was a blues modernist, steeped both in African-American tradition and in contemporary new music. She understood, too, that concert music is always theater, and she and Waldron brilliantly evoked the terror of the bombings, much as he and Holiday had once evoked the terror of lynching in “Strange Fruit.”

Perhaps the most striking words that Lee sings on Travellin’ in Soul-Time, however, belong to Waldron himself, in a vocal setting of his song “Seagulls of Kristiansund.” He imagines the birds diving into the sea from the sky,

“so near, yet so high”:

They’re wond’rously free

They live happily.

They know from the past,

a life cannot last,

So they live for today

for tomorrow they may not

Be able to dive from the sky.

The birds know what Waldron had to learn from his near-death experience. Lee bends and stretches his words with warm, melismatic accents, at one point mimicking the sounds of seagulls. And as she sings to Waldron, one feels as if the lyrics had always been there; the story they tell is as much a self-portrait as a tone poem about a flock of seagulls. Freedom and flight were the themes that gave shape to Waldron’s style after his breakdown. An ecstatic minimalism, it spoke of survival, rebirth, and the longing for transcendence. Its means were simple, but the stakes were not. Through his hypnotic repetitions, Waldron chased down that single, elusive note, as if his life depended on it.

Adam Shatz dedicates this essay to the memory of Geri Allen.

Adam Shatz is a contributing editor at the London Review of Books.

Two Interviews with Mal Waldron on The 86th Anniversary of His Birth

MAL WALDRON, 1925-2002

Mal Waldron (WKCR, Aug. 23, 2001):

[MW/BL/ED, “Fire Waltz”]

You’ve been recording with Reggie Workman for a good 25 years now. What kind of bassist and drummer are ideal for the way you play and write music? Well, Reggie Workman and Andrew Cyrille are ideal for the way a lot of people write music.

They listen and they try to adapt to what you’re doing. That’s all you need, is somebody to listen and to adapt to what you’re doing. Be like shadows. [LAUGHS]

Let’s step back to the Five Spot and that particular week, which resonates in many ways. It’s one of the last recordings by Booker Little, who was in amazing form, although by all accounts he was already quite ill. Eric Dolphy is in fine form, and it’s one of the first occasions Blackwell recorded outside of Ornette Coleman’s axis. How did the band come together?

I think Booker Little and Eric Dolphy had the idea together, to form a quintet and play both of their musics, and they hired me and Richard Davis and Ed Blackwell to support the group.

You had a musical relationship with Eric Dolphy from early 1960, and appear on some recordings with him on New Jazz.

I was the house pianist at Prestige. That’s how we hooked up.

So he signed his contract and you were hired to come in and play the music fresh. But he also recorded a fair amount of your music on The Quest.

The Quest was my date.

You were a beautiful match.

We got along beautifully. I learned from him, basically, because I was going through my student phase. I was learning from everybody.

One would think with someone of your curiosity, it might be a perpetual student phase.

It is..

But your music certainly had its own sound by 1960. You’re recognizably Mal Waldron by 1960. No one could mistake you for anybody else.

Well, I’m not quite sure about that, because I was still learning and putting it together. I was halfway through the tree. In other words, I started out with a big tree and I tried shaving and shaving and shaving try to find the perfect toothpick, but I wasn’t there in 1960 — definitely. I was nowhere near the toothpick at that moment.

But by 1960 you had played for a number of years with the Charles Mingus Jazz Workshop, you’d worked with Billie Holiday and attained broader recognition just by dint of being her accompanist, you’d played with Ike Quebec, you’d played with Lucky Thompson, you’d played with Lucky Millinder — a whole range of vernacular and functional gigs. You had a degree in music from Queens College. So you were by no means a neophyte.

Well, I might not have been a neophyte, but I really was in my mind a neophyte, because I was always like a little child around these people. Because they were all giants to me.

Is piano something you’ve done from the earliest days? Was there a piano in your house as a kid? You’re from St. Albans.

I was born in Harlem, but my parents moved out to Jamaica, Long Island, when I was 4. There we had a piano, and I was forced to take piano lessons. Really forced. If I didn’t do it, my father would pound me in the face or something like that! But I really didn’t want to play piano. I wanted to be outside in the street playing football with the other kids, but they said, “No-no, you’ve got to play piano.”

When did it start to take?

I don’t really know. I can’t really remember. I think when I heard Coleman Hawkins playing “Body and Soul.”

So you were 14 years old or so.

I think so. At that point, my mind moved toward jazz and I started fooling around on the piano at that moment with jazz (?).

So in the ’30s as a student pianist, it wasn’t jazz you were thinking about. You were studying the European Classical repertoire.

Yes, I was playing classics, and I didn’t like it because I had to do it the same way every time, otherwise I got my knuckles rapped.

Did you play in public at all, like in church or…

Yes, I did some concerts around… I’m trying to think where I played. But there were a few halls I played in. I can’t remember the names of them now.

But you developed your facility for the piano. Even though you were being forced to do it, it translated into some proficiency with the instrument.

Fear is a great motivator, you know!

Did hearing “Body and Soul” then start you off buying jazz records and listening to people…

Right. Then I started listening to Symphony Sid’s After-Hours Jam Session, which by the time I got home from school was on, and I listened to them every day.

Who were the people who first caught your ear, especially among pianists? 1939-40-41-42, Teddy Wilson is out there, Art Tatum…

Art Tatum caught my ear. Duke Ellington caught my ear first, and then Art Tatum, and then Bud Powell, and last, Thelonious Monk.

Did you go out and hear music when you were young?

Yes, I did. I was at the Cafe Society when Tatum played there, and I caught Bud on 52nd Street. I was in the Army at that time. I used to go down and hang out on 52nd Street, and then go back to West Point. I was stationed at West Point.

Was the Army after high school?

The Army was after high school, yes. It was my first year of college; I was drafted into the Army in ’43.

That’s just when the people from Minton’s were coming downtown to 52nd Street, and ferocious energies being unleashed.

Right. They were still up there at Minton’s, though. Because I used to go down to Minton’s, too, when I came down from West Point.

Describe your impressions of the scene. There aren’t so many people we can talk to who witnessed Minton’s or, for that matter, the Onyx and the clubs on 52nd Street.

It was a very energizing experience, because you were able to sit for half-an-hour in every bar along the way for 50 cents — you could buy a beer and sit there and nurse it and hear all the good music, and then you’d move on to the next bar. They were all very close to each other, and you could catch Billie Holiday in one, and Lester Young in another, and Bud Powell and Charlie Parker — all the people there, just lined up. It was fantastic.

At Minton’s it was a jam session type thing. They would play one tune, and the rhythm section would be up there pumping away and the horns would be soloing chorus after chorus and getting more furious, then the pianist would get tired and another pianist would take over, and it kept going like that all night long.

When did you start to put your toes in the water?

I didn’t put my toes in the water at Minton’s. I put my toe in the water at the Paradiso, which was a place around 110th and 7th Avenue that was run by Nick Nicholas. It was very close to Minton’s. The attitude was the same as Minton’s, and there were musicians passing through and sitting in. That’s when I first dipped my toes in the water!

This was after the Army, and after you came back to Queens College on the G.I. Bill and studying music?

Right.

Did you continue to play piano all this time?

No, I was a saxophonist at this time. My jazz experiences started with saxophone. When I first heard Coleman Hawkins I was so impressed with the saxophone that I went out and bought an alto. I couldn’t afford a tenor. I got a big, hard reed and an open lay on the mouthpiece so it would sound like a tenor, and I got the music for “Body and Soul” from “Downbeat” and I read it, and for 5 minutes I was Coleman Hawkins!

So you’re born in the same 24 month period as John Coltrane, Randy Weston, Jimmy Heath, Bud Powell is maybe a year older than you, Max Roach a year older than you… Were you smitten with Bebop? Is Bebop what captured you?

Yes, Bebop captured me. I was into the Bebop scene..

So as a young saxophonist, who were you trying to emulate?

I was trying to emulate Charlie Parker! But I couldn’t arrive, so I hocked the horn and went back to the piano. Because I found my basis on piano was strong enough at least to enable me to play the changes right.

Then you started developing your technique.

Yes, solos.

When was that? 1949-50 or so?

This was a little before 1950. Maybe 1947 to 1950.

During those years you made the transition from being an alto saxophonist to being a pianist, and gave up the horn around 1950.

That’s right.

Fifty years ago. And by this point, you were a professional musician?

No, I wasn’t earning any money at it. I was still going to college under the G.I. Bill, and I got my subsistence money from the Army to keep me going, and I lived at home with my mother and father, so I handled my expenses that way. Finally, I got into Charlie Mingus’ group around 1954 — the Jazz Workshop.

But during those years you were on the scene and hanging out, and presumably formed a circle of acquaintances and like-minded people with shared interests. Who were some of those people?

Randy Weston, and also Walter Bishop, Cecil Taylor, and Herbie Nichols, too, and Jackie McLean. I played with Allen Eager’s group for a minute, and also Lucky Thompson.

If I could ask you for some impressions. You’ve written a tune for Herbie Nichols, “Hooray For Herbie.”

Yes. He was a fantastic musician in that he had his own sound, which I didn’t have at that moment. I was interested in seeing how his sound fitted his personality, and that helped me to decide that your sound had to be your personality, so if you just played the way you spoke or automatically moved in the streets, you would be closer to your own sound.

He was a master on several levels, not just pianistically, but as a composer of fully worked-out pieces. Did you go through his scores or compositions?

Not at that time. I did that much later.

Were you aware of it at that time? Did people who knew him know that he had an identity outside of playing gigs at Your Father’s Moustache?

No, I don’t think they were too aware of it. But I know when he played opposite us on Barrow Street at the Bohemia, he played his own music at that moment and people became aware of it then.

How about Cecil Taylor in the early 1950s, and his sound and persona and manner?

Well, he was really out at that moment! He was working on it. I could see some form in there. I could see the way it was going. I could see a little bit of light at the end of the tunnel. A lot of people didn’t accept Cecil, but I did. I thought he was a fantastic musician and I still think he is a fantastic musician.

Randy Weston.

Randy was more like me. He was more into the formal music. He didn’t step outside, he didn’t play free, he played more In. We were both interested in waltzes, so we had a contest between us to see who could play the best waltzes! [LAUGHS] We had a little waltz competition going on…off the record, of course.

[MUSIC: MW/RW/Blackwell, “Thy Freedom Come”; Mal/Jeanne Lee, “Soul Eyes”; Abbey Lincoln/Mal, “Straight Ahead”]

Mal Waldron has long experience in accompanying and gently prodding singers to their strongest performances, an ability I’m sure he honed during his several years with Billie Holiday. [ETC.] Have you always played for singers?

Pretty much, yes, because they had more of an in with the areas to make money than the musicians really did.

Discuss your thoughts on the art of accompaniment.

Well, it’s really support. I just lay down a blanket for them to walk on, the blanket is me, and they walk on me!

Whatever the key might be!

[LAUGHS] Right.

Doing that, for one thing, you accumulate a lot of repertoire. And in doing so, I’d imagine that you internalize the lyrics for many of the songs that you subsequently have to play instrumentally, which would inflect your interpretation of those songs.

Right. It really helps me to improvise, because the words give it a completely different atmosphere to improvise on. You can improvise the words alone, instead of just improvising on the changes and the harmony and the melody.

Subsequently you wrote lyrics to “Soul Eyes,” after composing it… It’s hard to say which of Mal Waldron’s is the most classic, but “Soul Eyes” has particularly been a romantic tenor sax vehicle ballad showpiece — John Coltrane, George Coleman.

That tune was written for John Coltrane. I knew he was on the date the next day. The way the setup was in those days, they’d tell me who was on the set and then they’d tell me to write six or seven compositions for the date. So I had to stay up all night long and write the changes, and next morning I’d come in to Hackensack, N.J., and make the records, then I’d go home and write some more music for the next date.

Not a bad way to get your craft together.

No. Not a bad way to make money, too!

And you have royalties on a lot… Do you own this music?

Yes.

Prestige doesn’t own it.

Well, I get half and they get half.

So “Soul Eyes” was written for one of the Prestige Coltrane dates and not Impulse 21.

That’s right. It was originally for Prestige with the Two Tenors, Two Trumpets.

You did a lot of those dates. Gene Ammons, Jackie McLean, Paul Quinichette. What a great apprenticeship. How did it begin?

Jackie McLean is the one who first got me in there on a date he did, then Bob Weinstock liked me and Esmond Edwards liked me, and another guy named Ozzie Cadena was working for them, and he also liked me. So they kept giving me more and more dates to write for. That’s how come I’ve racked up so many compositions over the years. I have about 400 compositions out there, at least.

I’m sure you have favorites. I’ve listened to those Prestige dates, and the impression one gets of them is that they’re a little more substantial than the run-of-the-mill blowing session that Prestige dates could sometimes turn into, that your presence seemed to impart an organizing, cohesive quality.

I was very lucky in those days, though. The way I’d write the tunes, the first important thing was to be able to solo on it. So I’d make my changes first, nice blowable changes that you could solo on beautifully, and then I’d write a tune over the changes.

Write your melody…

Over the changes, yes.

I guess the Prestige relationship starts in ’56, when the first Jackie McLean record happens. At this point you’d been playing with Mingus for a couple of years. There’s a Teddy Charles Tentet date where you’d done “Vibrations,” a rather ambitious orchestrative piece. A lot of work around New York. So even though Mal Waldron says he felt like a child next to these musicians, he was certainly making his mark. Was composing for you a functional thing, something you plunged into because of economics? Or was there some inner imperative?

It went along with the improvising, which is instant composition for me. So I just decided to write them down and work with them a bit more on paper than just running them off as solos.

What’s the first composition or a few of yours that you remember finding yourself satisfied with and that continues to be in your repertoire? What’s with you now? “Dee’s Dilemma” is on this ’97 date, so I guess that’s one.

That’s tough.

Well, we can skip that. But obviously, your attitude toward old repertoire is accretive. You keep things, you discard things, you come up with new things, and it builds. Talk about the scene in New York in the ’50s. By now your toe isn’t dipped in the water; you’re at least up to your waist if not headlong. Talk about your daily life in ’54-’55-’56-’57.

Well, my life was consisting of thinking about the melodies in the daytime, writing them at night, and then recording them the next day.

But you were also working gigs.

Yes, I did some gigs, too, at that time.

I mean, all over New York, because there were so many clubs and so much music.

I was freelancing. I didn’t work with one group all the time. I worked with whoever called me. That was the way you did it in those days.

So Jackie McLean would get a gig at some place on 145th Street and would call you and you’d go in. Or then he’d go down to the Bohemia. It would be a circuit type of thing.

Well, it was a snowball effect, because you played with one musician and there was another sideman on the band who was also a leader, and he heard you, too, and if he liked you he’d use you on his date. Then he had another sideman on his date who was a leader, too… It just kept snowballing and snowballing until finally you played with all the musicians.

Talk about your association with Charles Mingus, which I gather was consequential for you.

Yes. Well, Mingus was like my older brother really. We talked a lot, and he gave me a lot of advice and helped to develop myself and become a mature musician. The first thing he told me was “don’t imitate anybody.” I was into imitating the people around me, like Bud Powell. I’d make Bud Powell runs and so forth. He said, “Don’t. That’s not the way. An ordinary musician can play everybody, but a jazz musician can only play himself.” So that stuck with me, and I started working on my own style.

So you credit Mingus with helping you find the Mal Waldron tonal personality.

Yes, sure.

And before that you were trying to play in the manner of Bud Powell, a lot of single line runs…

Right.

What did creating the Mal Waldron style entail? A more orchestral approach to the piano? A more compositional approach?

Well, it entailed not thinking of changes as changes, but thinking of changes as sounds, so that a cluster would do for a change or something like that, just a group of notes — not thinking of a tonal concept, just a group of notes would be an impetus for soloing on.

Were you doing formal study after Queens College? When did you graduate?

I came back in 1946. I graduated in 1949.

I’m assuming that the curriculum dealt with classical music up to modern European…

Right. I learned a lot about development of themes, too, from Karol Rathaus, who was the compositional teacher.

Did those lessons stay with you in your composition?

Definitely.

Your classical background never left you, your sense of harmony and shading…

And form and development, how to develop themes, sure.

I think people aren’t aware of how deeply classical music studies permeated musicians of your generation, who then created a lot of home-grown resolutions and utilizations of it. Can you address that a bit. I guess the G.I. Bill helped a lot of people.

Sure. Well, it had to do with the concepts of Bach. Bach is very basic. The way he moves from V to I, that concept is very instrumental in how the musicians grew. They moved from V to I, and they made it with a flat fifth and putting in stuff like extra notes in the chords and changes like that.

In your circle of friends with Randy Weston and Herbie Nichols, etc., were you talking a lot about classical music and listening to…

Yes, we discussed things like “Rite of Spring” and the sounds and things like that.

Then at night you’d be playing the blues in various places. I’m trying elicit a sense of the milieu in which sensibilities are formed. It’s very different today, how people find information and develop themselves…

Well, there were times when I would play with Tiny Grimes’ group, which was the Swinging Highlanders…

With kilts, right?

Yes, kilts. I didn’t wear the kilts. I just wore the tam, though! But after a night of that we’d come home and we’d put on our records and listen to Sonny Rollins playing things like “A Song In My Heart” and things like that. We’d just get away from the sound of what we were doing all night long.

You played with Ike Quebec for a while.

Yes. He was a beautiful person. He was the straw boss of the Lucky Millinder group. That’s how come I got into Lucky Millender’s band, too.

He became the de facto A&R man for Blue Note, although you wound up with Prestige, where Jackie McLean introduced you, and voila!

Right. Well, there was a competition between Blue Note and Prestige, too. If you went in one camp, you couldn’t go in the other camp. At the moment I went in, it was one or the other.

Talk about the milieu of those Prestige sessions, which have a different character than the analogous Blue Note sessions.

I’m not too aware of what the Blue Note sessions were like.

But how would they go down? You’d get a phone call, you’d write some music, a bunch of charts or tunes…

Right, and bring them in. We’d run them through maybe for ten minutes, or just talk about them, and then we’d make the record. They were usually all first takes, too.

I guess with people like Gene Ammons and Coltrane and Paul Quinichette and Frank Wess and Thad Jones, you didn’t need more than one take. [ETC.] In the previous set, we heard Mal Waldron with two great divas of the generation that grew up listening to Billie Holiday. Mal Waldron played for several years with Billie Holiday. I wonder if you can talk about how that happened and address the experience.

It was really an accident. Because her pianist… She was working in Philadelphia, and her pianist just conked out, he couldn’t function any more. So she needed the pianist. So she asked Bill Duffy, who had written the book with her, to find a pianist, and Bill asked his wife, Millie Duffy, if she knew any musicians, and Millie asked Julian Euell, who was one of her friends, and Julian Euell asked me, and I said “The buck stops here.” I got on a train and went there. So it was an accident, but it was a beautiful accident for me.

Were you always a fan of her music?

Oh yes, I was a fan of her music, but I had never played it. But I got a crash course!

And “Left Alone” was written for her?

Yes. She wrote the words and I wrote the melody. We were on a plane going from New York to San Francisco. It took more time than it does now because they were propeller planes. She just wanted to write tune about her life, so she wrote those lyrics, and I wrote the melody. By the time we got off the plane, it was finished.

What was she like with the band?

She was very relaxed. In fact, she didn’t make rehearsals. She didn’t like to make rehearsals. She just came on and did it. So I had to rehearse the band! [LAUGHS]

I guess you always took on those responsibilities. Let’s go to a 1956 session led by the vibraphonist Teddy Charles for Atlantic under the title, The Teddy Charles Tentet, which has an early and very ambitious Mal Waldron composition entitled “Vibrations.” It’s a feature for Gigi Gryce, with whom you played a lot. Art Farmer plays trumpet; he was on many of those Prestige sessions… [ETC.]

[MW/TC, “Vibrations,” MW/Coltrane/Shihab, “From This Moment On”; w/Jaymac, “Left Alone”; Abbey/Hawk, “Left Alone”; w/Dolphy, “We Diddit”]

Before The Quest in 1960, a lot of your compositions had been recorded, but something about this seemed to bring you to a different level. It seems pivotal in some way.

Well, it’s hard for me to make that statement. Because I was just growing; each year, each day, I was growing bigger and bigger. There’s no real point I can point to and say this was my best. I just growing every day.

In writing for The Quest, did you know who the horn players would be? Did you write for musicians? If you had a date with Gene Ammons and composed “Ammon Joy,” was that based on his…

Yes, on his sound. They’re all connected.

Or writing for Thad Jones or Frank Wess or John Coltrane. In each case you had their sound in mind.

Their sound in mind, sure. That’s the way you write.

So maybe it had something to do with the tonal personality of Eric Dolphy that made The Quest what it was.

Yes. And Booker Ervin, too. The sound just came to me as a whole entity.

You were describing the ambiance in the studio when Abbey Lincoln did “Left Alone” with Coleman Hawkins. You said that Monk was there.

Monk was there, yes. It was a very exciting day for me because Coleman Hawkins was playing my tune! That was a big joy for me. Then Thelonious Monk was in the room, and I had arranged one of his tunes for the date, “Blue Monk,” and I was interested to see if he would beat me up after the rendition.

What statement did he make?

He said, “That sounds good.” So I passed.

You’d been paying attention to Monk since the ’40s, I guess. Were you hearing him live before you heard his records? You’d have had an opportunity to do so.

Yes, I heard him at Minton’s Playhouse before I heard the records. It’s so long ago… He was very different and kind of austere, kind of imposing. He was a big man. And he looked like he had his whole world around him, and you couldn’t penetrate that world.

Was his sound immediately attractive to you as a twenty-ish aspirant?

No, it wasn’t immediately attractive to me. It was so strange, the way he hit the piano. But later it just grew on me. It just grows on you. It’s an acquired taste.

Were you studying his tunes and taking them apart once the records came out? Andrew Hill, for instance, described to me that as the records came out, and he and his friend, who were teenagers, would learn them directly off the records. You were somewhat older, but was that the way you did it as well?

No, I didn’t do it quite that way. I heard them and was impressed by them. But I didn’t learn them off the record. I was aware of the changes, so I approached them that way, and I tried to play them with my sound really.

On “From This Moment On” we heard the way you distilled Bud Powell, the fleet right-hand lines. For instance, with Bud Powell, were you trying to play his solos note-for-note in your learning process before you emerged? Were there other pianists like that? Or was it always getting an impression and then going out and doing what you do?

No, it was really note-for-note. I would try to imitate him when he played “Bud’s Bubble” and things like that. I’d try to imitate the sound. But that was before I got to Mingus. Mingus put an end to all that, and said, “Stop that!” [LAUGHS] He was a very impulsive person, being a Taurus. As I said, fear is a great motivator!

You’re on the session where “Haitian Fight Song” makes its debut. Coming up is “The Git-Go,” from a session with Joe Henderson.

WALDRON: The git-go means taking it from the top, taking it from the beginning. It has that funk and stuff like that…

[MW/Joe-Hen, “The Git-Go”, “Herbal Syndrome”]

We’ve kept Mal Waldron in the past, several generations ago, when he formed his sensibility and laid down an astonishingly strong corpus of work, which, had he never recorded another note after 1963, he’d still be remembered as one of the most consequential musicians of his time. But that edifice has turned into a pyramid or the Great Wall of China or something…but he’s created a huge body of work during his 36 years in Europe — lots of composing, associations with the creme de la creme of European improvisers, record dates for Japanese and European labels with people like Joe Henderson and Jackie McLean…much too much to address in the time we have. But I’d like to address the circumstances under which you settled in Europe. You had an illness, and moved to Europe in the aftermath of that. Let’s talk about getting established in Europe and your state of mind in the mid-’60s.

When I got to Europe, it was like the other side of the coin. In America if you were black and a musician at that time, it was two strikes against you. And in Europe, if you were black and a musician it was two strikes for you, so I decided to go for that.

Where did you initially move to?

Paris.

There were a number of Americans in Paris at that time. Arthur Taylor and Kenny Clarke had both moved there, Dexter Gordon…

Ben Webster was there.

Don Byas and Johnny Griffin. Are those the people you began to work with?

I worked with Ben Webster over there, at…what’s the name of this place…

Le Chat Qui Peche…

No, not Le Chat Qui Peche. Another one on the Right Bank.

But I’ll assume you landed in Europe playing…

Well, no. I went to Europe to write the music for a film. That’s how I got my plane fare over there. Marcel Carne, who directed the film Three Rooms in Manhattan, from a book that was written by Georges Simenon, and the film had Annie Girardot… He asked me if I wanted to write the music in New York or Paris. [LAUGHS] Of course… What a choice! I said, “Paris, of course,” and he paid my ticket over there and I landed in Paris.

And here we are in 2001…

Right! [LAUGHS] The musical scene was very varied in Paris at that moment. I remember working at Buttercup’s club, The Chicken Shack, which was in Montmartre; Buttercup was Bud Powell’s second wife, and they had their child Johnny with them, and I gave Johnny piano lessons. That was a gig for me, too.

Had you known Bud Powell before?

No, I never knew Bud, but I was aware of him. I never got to know him. When he came back to Paris, he was not very coherent.

Next we’ll hear Mal Waldron interpreting one of Bud Powell’s great ballads, which folks like Walter Davis and Barry Harris have played magical versions of. It’s a duo with Steve Lacy, with whom you’ve performed probably several thousand times in the last 30-plus years, always doing it differently. It’s perhaps the defining association of your many associations there… Well, for both of you in some ways.

Yes. The first time I met Steve, we did Jazz and Poetry at the Five Spot. That was our first meeting.

Who was the poet?

Kenneth Rexroth was the poet there, and also I think Ginsberg, and this artist Larry Rivers…

All of whom were drawing inspiration from jazz musicians, something the poets (not Larry Rivers) later renounced. Talk about that scene. Here I go again bringing you back to America. But this would be of interest to people only the most general interest in jazz, is the relationship between the avant-gardes, as it were, of literature and poetry and art and jazz music in the ’50s.

Well, they were together because we were both on the outer edges of the status quo. We were not included in the status quo. We were the outlaws really. [LAUGHS] So we ganged together. There was sawdust on the floor at the Five Spot! But we did some beautiful things together there.

On the East Village Frontier. Did you have that view yourself in the ’50s?

No. At that time, no.

This is in retrospect.

This is in retrospect. At that time I was just a normal person, playing a gig and getting money for it, and going home and feeding the family and stuff like that.

So in 1958, playing a gig with Kenneth Rexroth and Allen Ginsberg and Steve Lacy was just part of your quotidian, part of the big mosaic…

Right. They were not stars to me. They became stars when you look back, but they were not stars to me at that moment. They were just people that I worked with.

So you’d do that, then go out to Hackensack and do a session, then play a set in Harlem with somebody, day-after-day, one day at a time.

That’s right.

But let’s get back to Europe.

We both got to Paris. I hadn’t seen Steve in a little while, and then we met… They set us up for a gig in Italy, a duo, and we just came together and we didn’t have anything prepared, so we just improvised, and it worked. [LAUGHS] So that’s the way the duo started.

You both had an extremely broad range of reference, with Monk and Ellington as common points.

Well, music is a language, and as long as you have a large enough vocabulary, you can communicate with anybody else. And if the vocabulary is the same, then you can communicate even better. Steve and I had pretty much the same vocabulary.

You came up in a similar milieu, though you approached it from different angles. You had a quintet with him and Manfred Schoof. One of his quintets had you, though there was another one that didn’t have you. It’s been a symbiotic relationship. The last time you played together in the States was last summer at Carremour.

Yes. And we the Iridium, too. The Get Rid Of Them, I called it.

[Waldron/Lacy, “I’ll Keep Loving You”; “Johnny Come Lately”]

That scratches the surface of the oeuvre of Mal Waldron and Steve Lacy, which is massive and of the highest aesthetic level. [ETC.] You’ve been a resident of Belgium for some years now.

About 15 years in Belgium.

Do you work primarily in Europe or all over the world?

All over the world. I go to Japan and I go to South Africa and all over the world. I work with several different groups. For example, I do duets with David Murray, I do duets with Steve Lacy, and I used to do duets with Jeanne Lee, but she’s dead now. Then I have a quartet with John Betsch on drums, Arjen Gortner on bass, and Sean Bergin on tenor saxophone. I have the trio with Andrew Cyrille and Reggie Workman, who sometimes I bring to Europe. And then I have a duo with Jackie McLean that we’ve been doing lately, too.

Then there are solo piano things. I guess. You continue to write.

Yes, every day.

How do you decide when a melody works and when it doesn’t?

Well, when if it stays in my mind for two months then it works.

That’s the cutoff point?

That’s the cutoff point, right.

Say in the last two or three years, how many new pieces have come out?

Maybe 30, something like that.

You said you have about 400 copyrighted pieces. Are they all within jazz form? You do various commissions — ballets, film scores.

I didn’t count the ballets. The 400 tunes are jazz tunes done under the Prestige mantle while I was the house pianist there.

Oh, you’re just talking about 400 tunes in the ’50s and ’60s. Subsequent to what, what are we talking about? How many compositions have your copyright on them?

There are a couple of ballet scores. I did some things for Henry Street Playhouse, and I did some individual dance things with Florita Ropp(?) and other dancers around New York City in the early ’50s, I think. Then the film music, too.

So your compositions probably number a couple of thousand. How do you keep track of them and decide which stay in your repertoire?

Well, they don’t all stay with me. A lot of tunes I just remember the name, but I can’t remember the way it goes or anything like that. I can’t remember the changes. I have scores written so I can refer to it in case I want to play it again. But I go through stages where I’ll go backwards. For example, with Judi Silvano I went back and did some things I did for Prestige that I haven’t done for a long time.

“Cattin’,” “All Night Through.”

That’s a ballad. I haven’t played it for a long time, and Judi helped me rejuvenate it. Certain circumstances make me go back and other circumstances take me other places.

From Zephyr we’ll hear a new piece, entitled “You.”

[MW/Silvano, “You”; Mal solo, “You Don’t Know What Love Is” (1972)]

Mal Waldron brought a tape of a duo he did with the late South African bassist Johnny Dyani, who was a mainstay of European music for thirty years.

This is kind of a safari feeling. You’re out in the bush and you’re just moving. The feel is like that. It was done maybe 20 years ago in Paris. It was just released by Futura Records. It was done by the Jazz Unity at (?) which was functioning at that time, around 1975 or something like that.

[Mal/J. Dyani, “#1”]

When you hear Mal Waldron’s sound, you hear the New York sophistication, the stride piano thing, the Ellington-Monk continuum, the Bud Powell sound — and of course, Mal Waldron, as Charles Mingus admonished him always to retain… [ETC.] What do the next few months hold? Can you tell us when you’ll be back in the States?

I don’t plan to come back to the States for a while. I don’t feel relaxed here. I can’t relax. I like to smoke cigarettes, and I can’t smoke in the club, I can’t have one in the bandstand. And for me, having the smoke around me when I play the piano help me to feel the mood and feel relaxed and jazzy. You know?

You are old school!

That’s my “snoozedecker,” like they say; my blanket of security, like the little kid in Peanuts.

I guess in Belgium they have the good chocolate, the good beer, the good mussels. But we hope it won’t keep you away for too long, because we need our old masters here, and Mal Waldron is palpably one of them.

[MW/RW/AC, “Dee’s Dilemma”]

Mal Waldron (2-25-02):

What I’d like to do is ask you about current events, and ask some questions that spring to mind around those events. You just came back to Belgium from ten days at two of the Japanese Blue Notes with John Betsch and Jean-Jacques Avenel, your trio. Then you did some duos with Avenel and Lacy. You did a record at the end of January with Lacy for Sketch. You did a duo album for Enja with Archie Shepp of Billie Holiday material. And you’re about to go on a tour of master classes. You’re doing some festival appearances with a quartet, which is the rhythm section and Sean Bergin. And you’re doing a duo CD with David Murray as well.

Let me ask you about the personalities that are most suited to playing with you.

Actually, I don’t know, because I try to fit to them. I feel that the object is to make a beautiful sound, and if I can add to the sound, I play something to add to the sound, and if I can’t, then I don’t play anything, like Miles Davis once said. [LAUGHS]

You try to fit them and suit them. But that said, one can have a conversation with anybody, but there are some people with whom the sparks just fly and certain people with whom they don’t, and it seems there are certain types of musical personalities you intersect with where the sparks fly.

WALDRON: I think sparks fly with David Murray and I, because he’s adventurous, he likes to take risks, and I’m adventurous, I like to take risks — so we go up on that point together. Jean-Jacques Avenel is a fantastic bass player, I love him and also Steve Lacy is very adventurous.

Is it that risk-taking quality? That’s the main thing with you?

Yeah, that’s the main thing with me, because I hate monotony! I think that that’s what makes you get old — monotony. To stay young, you have to change all the time and be like a newborn baby, always adapting yourself to new situations.

Is that something that just happens, or are there processes you go through to get yourself there?

No, that’s something that just happens, really. It happens when the people opposite me are adventurous and take risks.

So that’s why you seek out those types of people. I guess they have to be also people like you, who have a very deep grounding in the fundamentals. Because your music is always very rooted and earthy…

Well, you have to have your vocabulary. That’s your vocabulary. You can’t talk to another person without a vocabulary! All of those things that went before in music is part of your vocabulary.

With Lacy, you’ve seemed to go through the whole legacy.

The gamut.

From Monk and Elmo Hope and Bud and Ellington to the songbook. Do you listen to your records analytically? Do you listen to them, or do you just do them and go on to the next thing?

I like to look forward. I don’t like to look back too much. Because I feel if you look back too much, you trip when you take a step forward.

But yet when you joined me on the radio, when you were selecting tunes you were pretty definite about which tracks you wanted to represent yourself with. So you’re obviously conscious of…

Yes, I’m conscious of everything I’ve done.

With Lacy, who you’ve played together in duo for over 20 years, and with whom your association goes back to 1955, how has that evolved from when you began your European association?

The European association started out very free. There was no material at all on the boards. We just related for an hour-and-a-half or something like that. Then later on, we started getting together and playing tunes. Steve brought out his tunes and I brought out my tunes, and we started involving working out on tunes and doing tunes by Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn and all the people we both liked.

So you just organically evolved a repertoire, beginning with original music and then moving to common vocabulary. You’ve played with so many dynamic drummers. We’re talking about Max Roach, not to mention the Prestige sessions with Arthur Taylor, or with Blackwell later on, and Cyrille right now, or Billy Higgins… Is there a particular kind of drummer who sets off sparks with you?

Yes, the type of drummer who doesn’t feel that one has to be fixed. One should be fixed in their mind, and then they can play all over it, all around it, but they always know where the start of the bar is.

Is there any component to the way you think about playing music that’s like a drummer in terms of the percussive aspect of the piano? Is it something you’re very conscious?

Yes, I’m very conscious of it, because I learned long ago that the piano is a percussive instrument. It’s a percussive instrument because you beat on it, so it’s drum-like. It’s basically a percussive instrument, so you have to use it like that.

When did you learn that?

Oh, way back, when I was with Charlie Mingus or earlier than that.

Is that when Mingus told you to stop playing like Bud Powell and be yourself, or words to that effect?

[LAUGHS] Right. About that time.

Was that a difficult lesson to learn, that the piano is a drum?

No, it wasn’t too hard for me to learn, because I love to bang on things! Even as a child, I used to bang on things!

Well, you and your friend Randy Weston came to similar conclusions about the piano. Cecil Taylor, too. All around that time. Maybe I’m being a bit too free and easy with chronology here. But what was in the air then that gave you this sense of endless possibility?

Well, first of all, we realized that jazz was a music of protest, that it was the music of people who wanted to change the status quo, who were not satisfied with things going as it is now. So that meant you would strike back. So that gave us the punch to… You’d punch the piano like you were punching somebody who was in your way or something like that.

Is jazz still that?

Jazz is still a music of protest, right.

What were some of the stylistic antecedents you would have looked to in that? Was that something, let’s say, you heard in Monk and Ellington?

I heard it in Monk and Ellington. I heard it in Jimmie Lunceford’s band. I heard it in Billy Eckstine’s band. I heard it almost all over the place!

And you were an avid listener as well. I know you told me when you heard “Body and Soul,” you bought an alto saxophone, changed the mouthpiece to make it sound like a tenor, and learned Coleman Hawkins’ solo, and you were on your way.

[LAUGHS] Right.

The chronology you gave me was this. You said you were forced to take piano lessons, fear was the great motivator because your father would get physical with you if you didn’t do it.

He would kill me!