SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2018

VOLUME FIVE NUMBER TWO

GERI ALLEN

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

TOMEKA REID

(January 27--February 2)

FARUQ Z. BEY

(February 3--9)

HANK JONES

(February 10--16)

STANLEY COWELL

(February 17–23)

GEORGE RUSSELL

(February 24—March 2)

ALICE COLTRANE

(March 3–9)

DON CHERRY

(March 10–16)

MAL WALDRON

(March 17–23)

JON HENDRICKS

(March 24–30)

MATTHEW SHIPP

(April 1–7)

PHAROAH SANDERS

(April 8–14)

WALT DICKERSON

(April 15–21)

Don Cherry

(1936-1995)

Artist Biography by Chris Kelsey

Imagination and a passion for exploration made Don Cherry one of the most influential jazz musicians of the late 20th century. A founding member of Ornette Coleman's groundbreaking quartet of the late '50s, Cherry

continued to expand his musical vocabulary until his death in 1995. In

addition to performing and recording with his own bands, Cherry worked with such top-ranked jazz musicians as Steve Lacy, Sonny Rollins, Archie Shepp, Albert Ayler, John Coltrane, and Gato Barbieri. Cherry's most prolific period came in the late '70s and early '80s when he joined Nana Vasconcelos and Collin Walcott in the worldbeat group Codona, and with former bandmates Charlie Haden and Ed Blackwell, and saxophonist Dewey Redman in the Coleman-inspired group Old and New Dreams. Cherry later worked with Vasconcelos and saxophonist Carlos Ward in the short-lived group Nu.

Born in Oklahoma City in 1936, he first attained prominence with Coleman, with whom he began playing around 1957. At that time Cherry's

instrument of choice was a pocket trumpet (or cornet) -- a miniature

version of the full-sized model. The smaller instrument -- in Cherry's

hands, at least -- got a smaller, slightly more nasal sound than is

typical of the larger horn. Though he would play a regular cornet off

and on throughout his career, Cherry remained most closely identified with the pocket instrument. Cherry stayed with Coleman through the early '60s, playing on the first seven (and most influential) of the saxophonist's albums. In 1960, he recorded The Avant-Garde with John Coltrane. After leaving Coleman's band, Cherry played with Steve Lacy, Sonny Rollins, Archie Shepp, and Albert Ayler. In 1963-1964, Cherry co-led the New York Contemporary Five with Shepp and John Tchicai. With Gato Barbieri, Cherry led a band in Europe from 1964-1966, recording two of his most highly regarded albums, Complete Communion and Symphony for Improvisers.

Cherry began the '70s by teaching at Dartmouth College in 1970, and recorded with the Jazz Composer's Orchestra in 1973. He lived in Sweden for four years, and used the country as a base for his travels around Europe and the Middle East. Cherry became increasingly interested in other, mostly non-Western styles of music. In the late '70s and early '80s, he performed and recorded with Codona, a cooperative group with percussionist Nana Vasconcelos and multi-instrumentalist Collin Walcott. Codona's sound was a pastiche of African, Asian, and other indigenous musics.

Concurrently, Cherry joined with ex-Coleman associates Charlie Haden, Ed Blackwell, and Dewey Redman to form Old and New Dreams, a band dedicated to playing the compositions of their former employer. After the dissolution of Codona, Cherry formed Nu with Vasconcelos and saxophonist Carlos Ward. In 1988, he made Art Deco, a more traditional album of acoustic jazz, with Haden, Billy Higgins, and saxophonist James Clay.

Until his death in 1995, Cherry continued to combine disparate musical genres; his interest in world music never abated. Cherry

learned to play and compose for wood flutes, tambura, gamelan, and

various other non-Western instruments. Elements of these musics

inevitably found their way into his later compositions and performances,

as on 1990's Multi Kulti, a characteristic celebration of musical diversity. As a live performer, Cherry

was notoriously uneven. It was not unheard of for him to arrive very

late for gigs, and his technique -- never great to begin with -- showed

on occasion a considerable, perhaps inexcusable, decline. In his last

years, especially, Cherry

seemed less self-possessed as a musician. Yet his musical legacy is one

of such influence that his personal failings fade in relative

significance.

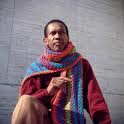

Don Cherry

Don Cherry

Don Cherry was born in Oklahoma City, OK in 1936 and raised in Los Angeles, where he first began to play the trumpet and later piano. According to Cherry, his upbringing had everything to do with his interest in music:

“Yeah, well I was fortunate to have such great parents…because they've always been around music. My Father was a bartender, and he was very much into the music of the swing period. That whole groove of music and ballrooms and dance and what it meant in the late 30's and up into the 40s. So I was raised around all that type of music. But what was happening after especially moving to Watts, what was happening in our neighborhood, there was musicians…Dexter Gordon, Wardell Grey, Sonny Criss, all these people that were from the neighborhood…and what was happening in rhythm and blues…”

Don cut his teeth on bebop, like most young musicians of his generation. In one of those historic moments that defy reason, Don met young saxophonist Ornette Coleman in a record store on 103rd Street, and was soon playing with Coleman's seminal quartet which also included bassist Charlie Haden and drummer Billy Higgins. The group cut the landmark album Something Else!!! , ushering in the new Free Jazz movement. The group recorded several other albums and free jazz became an established jazz innovation during the 1960s. Cherry worked with other artists, including John Coltrane, Archie Shepp, and Albert Ayler, who were all becoming instrumental in the greatest developments in jazz music since the birth of bebop.

By the dawn of the 70s, Cherry was touring Europe, Asia, and Africa regularly and becoming versed in the musical heritage of a variety of countries. He began learning to play many different instruments, including wooden flutes and the doussn'gouni, a kind of cross between a guitar and a sitar. It was at this time that Cherry began to play the Pakistani pocket trumpet, a miniature trumpet of approximately 8” in length. He began to play the instrument extensively, and it became his favorite. The tone was quite unusual, as was Cherry's facility to play a flurry of notes without appearing to break a sweat, a la Miles Davis. But his sound was a bit more refined, sweeter, and even more laid back than Davis' (!) partly because of his unusual choice of instrument.

Cherry began to incorporate influences from various ethnic musics into his own jazz work and created performances with his Swedish wife, Moki, that were not only musical but also visual. Much of what Cherry did in the 70s laid the groundwork for what has come to be known as “world music”. During the 1980s and 90s his stature as a figure in the world music movement grew, and he played and recorded prolifically. He formed a new quartet with Charlie Haden, Ed Blackwell (who had played with Ornette Coleman as well) and Dewey Redman. They revisited the work done by the original Coleman quartet and extended the concepts begun there. He also formed a trio, Codona, with Collin Walcott and Nana Vasconcelos.

Cherry is sometimes relegated to the “back burner” because his music moved so far from its bop origins and sometimes away from jazz itself. But only a handful of musicians have had the chance to impact jazz music as he did with the Ornette Coleman groups. In addition, he continued to influence music the world over and stretch boundaries in ways that have continued to influence newer jazz musicians who may be only vaguely aware of Cherry's work. Don Cherry died in 1995, and his son Eagle Eye and stepdaughter Neenah have become popular recording artists, no doubt nurtured and encouraged by the atmosphere of music that Cherry's own parents had passed on to him in the 1930s.

Photo Credit: Brian McMillen

https://reflectionsinrhythm.wordpress.com/2009/11/22/reflections-of-don-cherry-an-adventure-in-sound/

In memory of music innovator Don Cherry:

Born November 18, 1936

Transitioned: October 19, 1995

The following is from an interview / conversation that I was honored to share with one of music’s truly creative sources in 1994. The interview was originally published in the August 1994 issue of Jazz Now Magazine.

Don’s soulful creativity can be heard on countless recordings as a leader and contributing guest. Check him out as you check this out...

THE MUSICAL EXPLORATIONS AND REALIZATIONS OF DON CHERRY

Over the past three and a half decades Don Cherry has created one of the most unique voices in modern music. From his major introduction to the public as a member of the ground-breaking Ornette Coleman Quartet of the late 50s and early 60s to his numerous collaborations with some of the most adventurous and creative minds in music, the sound of his pocket trumpet has become an instantly recognizable notice that a musical journey is about to take place.

Travels through sound and music with Don Cherry have included Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane, Steve Lacy, Gato Barbieri, Archie Shepp, Albert Ayler, Hilton Ruiz, Dewey Redman, Carla Bley, Peter Apfelbaum and most of the true innovators of the past thirty years. Regardless of where the journey may end for the musicians and the listener, the take off point for Don was “Harmolodics”, the musical concept that Ornette Coleman introduce to a dis-believing group of musicians and audiences in the mid 60s.

Although Ornette’s theories weren’t easily accepted by most at the time, Cherry expressed a great interest in the things Ornette was trying to express musically, as he remembers, “When I first heard Ornette I was playing with another group with Billy Higgins in Los Angeles. We heard Ornette and Blackwell (Ed), they were on the scene, that was back in the 50s.” Soon after meeting with Ornette, Don was a regular member of practice sessions led by Coleman. “I started practicing with him with saxophone player James Clay. We would go to Ornette’s house to study. It wasn’t just practicing it was studying, which it still is.”

The theory of “Harmelodics” may have been considered a musical breakthrough for some, but there were countless others who considered it a bad joke at best or an insult to music and musicians at worst. As Don looks back on these early years he reflects, “I think the improvising, the solos were more disturbing or advance for people to hear, but the compostions were so melodic I think that’s what brought the people in close to the music. There was an audience of people that loved it or they didn’t like it and felt intimidated by the music. With musicians that was one kind of reaction, because the musicians would judge this kind of music by what they were doing”.

As many people would discover with time, “Harmolodics” proved to be a legitimate musical form with a life of it’s own. “Ornette has his own clef”, Cherry explains, “When he writes his music he has the Treble clef, Harmolodic cleff, which is like the figure eight, and the Bass clef.” “He would write things where I would play the melody and he would write a harmony to that melody and the harmony that he would write would end up being the melody and the first melody ends up being the harmony.” A prime example of this technique is the Ornette Coleman recording, “Skies of America” which also includes Dewey Redman.

Through out his career, Don Cherry has been heard in a varied array of musical settings, from straight Be Bop to music of India, Africa and other corners of the world. Cherry’s eclectic taste in music can be traced back to his childhood; “I was born in Oklahoma and I have American Indian, Chaktaw, parents so I’ve always heard gospel music and American Indian music and the blues. My father was a bartender and through him I heard a lot of dance music, Fletcher Henderson and Artie Shaw, Count Basie, Duke. I was always around the music at dances and gay events.” “My mother was in a club where there were twelve women and they each had a month that they would give a party.”

During his junior high school years Don picked up the trumpet and hasn’t put it down since. “I played a lot of Latin music when I started playing trumpet, which I started on in junior high school. I’d play at weddings and places like that. My cousin knew all the Latin cats. He was a merchant marine and on his ship he’d bring records back and turn me on to Latin music.” The Los Angeles jazz scene also became a learning source. “When I started playing we used to go hear Wardell Grey and Dexter Gordon, and check out that whole scene…Sonny Criss, and Hampton Hawes. That was the scene around the neighborhood.” “Eric Dolphy was always helpful, and Frank Morgan was very helpful to us young kids trying to learn.”

When it came to trumpet players, Cherry listened to and learned from the top names of the day. “My favorite trumpet player was Fats Navarro even though I always listened to Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie. The trumpet player who was on the scene in California that I always loved was Harry “Sweets” Edison.

As time moved on Don became one of the musical explorers of time. Though known mainly as a trumpet player, he’s also studied and recorded with instruments of different cultures and from different countries. He give this insight, “It’s one thing to try to play exotic, but to study a music, like Indian music, to study it and realize the scales and different things you gain a respect for the culture and the music. Playing with George Russell really opened that up for me.” “I learned that with Japanese music they have morning scales and afternoon scales. The first scale played has a half tone in it. They have 36 notes in an octave while we (Americans) have only 12. They have 36 because of those minor tones. That half tone is how meditation and the sensitiveness of your feelings moves and slides. A good example of that type of playing in jazz, a master of that was Johnny Hodges, That half tone is a very important tone because it’s the first tone of the day. The whole tone is more for dancing.”

The Doussin gouni has been a frequent instrument of choice for Don Cherry as well as a Chinese ceramic flute called the Hsuan, also known as the plum flute or earth flute. He explains his introduction to and fascination with the Hsuan, “When I was teaching in 1970 I was thankful and happy to be around some of the best western ceramic craftsmen up there. There was a family who had learned the Japanese style of ceramic making. One son, Eric O’Leary introduced me to this Chinese instrument, the Hsuan. Eric would make the flute and before he would put it in to bake it I would add the holes.”

The continued search for musical expression led to the formation of the group CODONA which featured Colin Walcott, Nana Vascancelos, and Don. Of this group Don says, “We stayed together until Colin died, he was the synthesis that brought the group together. Nana and I met playing with Abdullah Ibrahim. After recording on a project of Colin’s called “Grazing Dreams” for ECM records we all got together as a group, because of the instrumentation. I mean Nana was playing percussion and different instruments like the tabla. Colin would play the finger piano, and we would include the sitar and we would have all of these different sounds for compositions that we would write together. We would also have traditional compositions for the different instruments we played.”

Now matter what type of music he’s playing, for Don Cherry there’s a strong connection between society, politics and music and the best example of this connection in America is Rap. Comparing today’s rap messages to forms of expression used in the past he observes, “Zulu poetry has always been passed on for many years, but has not been written down and what’s happening in rap is poetry bringing out the problems and looking for solutions for what’s happening now.”

Over the past few years Don has recorded a couple of projects for A & M records, one featuring his old friend James Clay (Art Deco), and another where he’s joined by Peter Apfelbaum and the Heiroglyphics Ensemble (Mulit Kulti). Of the Heiroglyphics Ensemble Cherry states, “I’ve listened to Peter and the way the band has developed over the past few years and it’s been exciting. For me playing with this group is true bliss and heavenly to play with this group.” He also considers the Heiroglyphics Ensemble one of his main reasons for moving to the Bay Area in 1988.

As busy as he may get with other musical commitments there’s always time for Ornette. Commenting on a recent performance with his musical soulmate that also included Ornette’s son Denardo on drums and bassist Charnette Moffit, son of former Coleman bandmate Charles Moffit, Cherry says, “Charnette was great, he’s growing everyday with the music and Denardo has been playing ever since he was 13. Ornette is still the same way he was when I met him. Practicing, writing, composing, always around music. His whole life is music. It was really beautiful watching him and Denardo together.”

It seems that time hasn’t changed Don much either. From his first musical introduction in 1959 to the present he remains as creative, curious and adventurous, and always looking for more passengers for the next musical journey…..Listen

Reflections of Don Cherry: An Adventure in Sound

In memory of music innovator Don Cherry:

Born November 18, 1936

Transitioned: October 19, 1995

The following is from an interview / conversation that I was honored to share with one of music’s truly creative sources in 1994. The interview was originally published in the August 1994 issue of Jazz Now Magazine.

Don’s soulful creativity can be heard on countless recordings as a leader and contributing guest. Check him out as you check this out...

THE MUSICAL EXPLORATIONS AND REALIZATIONS OF DON CHERRY

Over the past three and a half decades Don Cherry has created one of the most unique voices in modern music. From his major introduction to the public as a member of the ground-breaking Ornette Coleman Quartet of the late 50s and early 60s to his numerous collaborations with some of the most adventurous and creative minds in music, the sound of his pocket trumpet has become an instantly recognizable notice that a musical journey is about to take place.

Travels through sound and music with Don Cherry have included Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane, Steve Lacy, Gato Barbieri, Archie Shepp, Albert Ayler, Hilton Ruiz, Dewey Redman, Carla Bley, Peter Apfelbaum and most of the true innovators of the past thirty years. Regardless of where the journey may end for the musicians and the listener, the take off point for Don was “Harmolodics”, the musical concept that Ornette Coleman introduce to a dis-believing group of musicians and audiences in the mid 60s.

Although Ornette’s theories weren’t easily accepted by most at the time, Cherry expressed a great interest in the things Ornette was trying to express musically, as he remembers, “When I first heard Ornette I was playing with another group with Billy Higgins in Los Angeles. We heard Ornette and Blackwell (Ed), they were on the scene, that was back in the 50s.” Soon after meeting with Ornette, Don was a regular member of practice sessions led by Coleman. “I started practicing with him with saxophone player James Clay. We would go to Ornette’s house to study. It wasn’t just practicing it was studying, which it still is.”

The theory of “Harmelodics” may have been considered a musical breakthrough for some, but there were countless others who considered it a bad joke at best or an insult to music and musicians at worst. As Don looks back on these early years he reflects, “I think the improvising, the solos were more disturbing or advance for people to hear, but the compostions were so melodic I think that’s what brought the people in close to the music. There was an audience of people that loved it or they didn’t like it and felt intimidated by the music. With musicians that was one kind of reaction, because the musicians would judge this kind of music by what they were doing”.

As many people would discover with time, “Harmolodics” proved to be a legitimate musical form with a life of it’s own. “Ornette has his own clef”, Cherry explains, “When he writes his music he has the Treble clef, Harmolodic cleff, which is like the figure eight, and the Bass clef.” “He would write things where I would play the melody and he would write a harmony to that melody and the harmony that he would write would end up being the melody and the first melody ends up being the harmony.” A prime example of this technique is the Ornette Coleman recording, “Skies of America” which also includes Dewey Redman.

Through out his career, Don Cherry has been heard in a varied array of musical settings, from straight Be Bop to music of India, Africa and other corners of the world. Cherry’s eclectic taste in music can be traced back to his childhood; “I was born in Oklahoma and I have American Indian, Chaktaw, parents so I’ve always heard gospel music and American Indian music and the blues. My father was a bartender and through him I heard a lot of dance music, Fletcher Henderson and Artie Shaw, Count Basie, Duke. I was always around the music at dances and gay events.” “My mother was in a club where there were twelve women and they each had a month that they would give a party.”

During his junior high school years Don picked up the trumpet and hasn’t put it down since. “I played a lot of Latin music when I started playing trumpet, which I started on in junior high school. I’d play at weddings and places like that. My cousin knew all the Latin cats. He was a merchant marine and on his ship he’d bring records back and turn me on to Latin music.” The Los Angeles jazz scene also became a learning source. “When I started playing we used to go hear Wardell Grey and Dexter Gordon, and check out that whole scene…Sonny Criss, and Hampton Hawes. That was the scene around the neighborhood.” “Eric Dolphy was always helpful, and Frank Morgan was very helpful to us young kids trying to learn.”

When it came to trumpet players, Cherry listened to and learned from the top names of the day. “My favorite trumpet player was Fats Navarro even though I always listened to Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie. The trumpet player who was on the scene in California that I always loved was Harry “Sweets” Edison.

As time moved on Don became one of the musical explorers of time. Though known mainly as a trumpet player, he’s also studied and recorded with instruments of different cultures and from different countries. He give this insight, “It’s one thing to try to play exotic, but to study a music, like Indian music, to study it and realize the scales and different things you gain a respect for the culture and the music. Playing with George Russell really opened that up for me.” “I learned that with Japanese music they have morning scales and afternoon scales. The first scale played has a half tone in it. They have 36 notes in an octave while we (Americans) have only 12. They have 36 because of those minor tones. That half tone is how meditation and the sensitiveness of your feelings moves and slides. A good example of that type of playing in jazz, a master of that was Johnny Hodges, That half tone is a very important tone because it’s the first tone of the day. The whole tone is more for dancing.”

The Doussin gouni has been a frequent instrument of choice for Don Cherry as well as a Chinese ceramic flute called the Hsuan, also known as the plum flute or earth flute. He explains his introduction to and fascination with the Hsuan, “When I was teaching in 1970 I was thankful and happy to be around some of the best western ceramic craftsmen up there. There was a family who had learned the Japanese style of ceramic making. One son, Eric O’Leary introduced me to this Chinese instrument, the Hsuan. Eric would make the flute and before he would put it in to bake it I would add the holes.”

The continued search for musical expression led to the formation of the group CODONA which featured Colin Walcott, Nana Vascancelos, and Don. Of this group Don says, “We stayed together until Colin died, he was the synthesis that brought the group together. Nana and I met playing with Abdullah Ibrahim. After recording on a project of Colin’s called “Grazing Dreams” for ECM records we all got together as a group, because of the instrumentation. I mean Nana was playing percussion and different instruments like the tabla. Colin would play the finger piano, and we would include the sitar and we would have all of these different sounds for compositions that we would write together. We would also have traditional compositions for the different instruments we played.”

Now matter what type of music he’s playing, for Don Cherry there’s a strong connection between society, politics and music and the best example of this connection in America is Rap. Comparing today’s rap messages to forms of expression used in the past he observes, “Zulu poetry has always been passed on for many years, but has not been written down and what’s happening in rap is poetry bringing out the problems and looking for solutions for what’s happening now.”

Over the past few years Don has recorded a couple of projects for A & M records, one featuring his old friend James Clay (Art Deco), and another where he’s joined by Peter Apfelbaum and the Heiroglyphics Ensemble (Mulit Kulti). Of the Heiroglyphics Ensemble Cherry states, “I’ve listened to Peter and the way the band has developed over the past few years and it’s been exciting. For me playing with this group is true bliss and heavenly to play with this group.” He also considers the Heiroglyphics Ensemble one of his main reasons for moving to the Bay Area in 1988.

As busy as he may get with other musical commitments there’s always time for Ornette. Commenting on a recent performance with his musical soulmate that also included Ornette’s son Denardo on drums and bassist Charnette Moffit, son of former Coleman bandmate Charles Moffit, Cherry says, “Charnette was great, he’s growing everyday with the music and Denardo has been playing ever since he was 13. Ornette is still the same way he was when I met him. Practicing, writing, composing, always around music. His whole life is music. It was really beautiful watching him and Denardo together.”

It seems that time hasn’t changed Don much either. From his first musical introduction in 1959 to the present he remains as creative, curious and adventurous, and always looking for more passengers for the next musical journey…..Listen

http://www.nytimes.com/1995/10/21/arts/don-cherry-is-dead-at-58-trumpeter-of-a-lyrical-jazz.html

Don Cherry Is Dead at 58; Trumpeter of a Lyrical Jazz

by PETER WATROUS

October 21, 1995

New York Times

Don Cherry, one of the most lyrical and important jazz trumpeters, died on Thursday at the home of his stepdaughter, Neneh Cherry, near Malaga, Spain. He was 58.

The cause was liver failure caused by hepatitis, said his wife, Moki.

Mr. Cherry used a pocket cornet -- a shrunken cornet

-- to get an open, quiet sound. He managed emotionally charged

statements without force, and his playing radiated fragility, as if he

had come to his style without study.

He began his career studying the works of the

trumpeter Fats Navarro, and his playing was often a lyrical paraphrase

of be-bop ideas without a wasted note. By the end of his life, his music

incorporated funk and ethnic musics from around the world, fusing his

avant-garde vocabulary with folk and pop music. In describing his

studies to the drummer Art Taylor for the book "Notes and Tones" (Da

Capo Press, 1993), Mr. Cherry said, "First it was form, then phrasing

and then sound, always sound."

Mr. Cherry was a product of the fertile postwar

be-bop scene in Los Angeles in the 1940's. He came from a musical

environment, with a grandmother who played piano accompaniment for

silent movies, a mother who played piano at home and a father who owned a

music club in Tulsa. His father also worked as a bartender at the

Plantation Club, a leading jazz club, in the Watts section of Los

Angeles.

At Jefferson High School, Mr. Cherry studied with

Samuel Brown, a respected teacher who had taught the jazz musicians

Wardell Gray, Frank Morgan, Hampton Hawes and Art Farmer. The Los

Angeles of his youth produced or was home to many jazz musicians who

helped to set the standard for experimentation in the next few decades,

including Charles Mingus, Scott LaFaro, Gary Peacock, Eric Dolphy,

Charlie Haden and Paul Bley.

By 1954, Mr. Cherry, still a teen-ager, was playing

professionally, a career course his father tried to stop. Two years

later, Mr. Cherry met Ornette Coleman, a meeting that changed the course

of jazz history.

Mr. Cherry, along with the drummer Billy Higgins

(whom Mr. Cherry met when both were high school students in a

truant-detention school) and a tenor saxophonist, James Clay, were drawn

to Mr. Coleman's ideas and began rehearsing regularly with him. At the

same time, Mr. Cherry was performing in the area, working with the

intermission band at the Lighthouse, which was then the most famous jazz

club in Los Angeles.

In 1958, Mr. Cherry and Mr. Coleman, along with the

pianist Paul Bley (who was the leader of the group), the bassist Charlie

Haden and the drummer Mr. Higgins began an engagement at the Hillcrest

Club; live recordings of some of those sessions show the band playing

Mr. Coleman's tunes with authority and a sense of experimentation.

In February 1958, Mr. Coleman began his recording

career with "Something Else," an album that included Mr. Cherry and Mr.

Higgins. The pianist John Lewis arranged for the group to join Atlantic

Records, where it recorded the album "The Shape of Jazz to Come" a year

later. That same year, the group spent two and a half months at the Five

Spot in New York, a stay that was meant to last only two weeks. Mr.

Coleman's music split the jazz world between those who believed in his

rewriting of jazz orthodoxy and those who didn't.

The importance of Mr. Coleman's recordings with Mr.

Cherry cannot be overestimated. The rhythmic relationship between the

two musicians, loose and flexible yet completely empathetic, took jazz

modernists away from an emphasis on overt discipline and precise

detailing. And both Mr. Cherry and Mr. Coleman drew on a huge variety of

sources for their melodies. They knew be-bop, but even Mexican melodies

showed up in their improvisations, along with country blues lines. This

added a rural, folk element to jazz.

Mr. Cherry first recorded under his own name in

1960, on an album called "The Avant Guarde"; John Coltrane was a

sideman. He recorded infrequently in the next few years, but began a

series of associations that had him collaborating with nearly every

important player in the mushrooming avant-garde of the time.

In 1962, he began an association with the

saxophonist Sonny Rollins that included concert appearances around the

world and recordings; he also recorded with the saxophonist Steve Lacy.

That year Mr. Cherry also helped form the New York Contemporary Five

with the saxophonists Archie Shepp and John Tchicai. By 1964, Mr. Cherry

had begun work with the saxophonist Albert Ayler.

In 1964, after touring Europe, Mr. Cherry went to

Paris. He formed a band of international musicians there that included

the tenor saxophonist Gato Barbieri. A year later, the band came back to

New York City, where it recorded what is often considered Mr. Cherry's

masterpiece, "Complete Communion," for Blue Note records, beginning a

short association with the label.

In the mid-60's, Mr. Cherry began experimenting with

all sorts of music, and for the rest of his career he wandered

internationally. He began playing duets with the drummer Ed Blackwell,

which he continued until the 1980's.

In the 70's, he taught at Dartmouth College, and

lived not only in Europe but also in the Middle East, all the while

absorbing local music. In 1973, he recorded the "Relativity Suite," with

the Jazz Composers' Orchestra, which included a string section. He

recorded with Lou Reed, the singer and guitarist, and took part in the

group Codona, with Nana Vasconcelos and Collin Walcott.

Mr. Cherry recorded a funk-and-ethnic album in Paris

and also performed with the band Old and New Dreams, a revival of

Ornette Coleman's acoustic quartet with the saxophonist Dewey Redman in

Mr. Coleman's place. In 1984, he founded the group Nu, which included

the saxophonist Carlos Ward and Mr. Vasconcelos. He continued to make

recordings into the 90's.

In addition to his wife, of New York City, and his

stepdaughter, he is survived by his sons Jan and David, of Los Angeles;

Eagle Eye, of New York; Christian, of Copenhagen, and his mother, Daisy

McKee of Los Angeles.

Photo: Don Cherry (Jack Vartoogian, 1990)

Don Cherry: Trumpet Innovator

Fabio Rojas (December 1997)

Don Cherry died over a year ago and jazz lost one of its greatest voices. On a more positive note, in honor of Don Cherry, let me take a few moments to say something about his trumpet playing. The more I think about it, the more he'll be remembered as being one of the defining voices of the jazz trumpet. I think he is one of those figures that is part of the great lineage from King Oliver, Louis Armstrong right up through Freddie Hubbard, Lee Morgan and the moderns like Wynton Marsalis (the neotraditional) and Leo Smith (the avant garde).

For starters, he was the first great free trumpeter. On Shape of Jazz to Come and the other great Atlantic recordings, he produced the first competent examples of the bebop style played independent of traditional harmony. He also had a truly distinctive voice on the horn - kind of tight and astigmatic but at the same time large and open. Very much like Ornette Coleman's sound, but in its own way much more warm. It was this combination of Coleman's bluesy sound and Cherry's bop that gave the first great Coleman quartet its truly distinctive sound. It is so remarkable that in one interview, Wynton Marsalis said that if a person were to listen to just one jazz album, it ought to be The Shape of Jazz to Come.

Then in the mid 60's he pushed the frontiers of free jazz with John Tchicai, John Coltrane, Albert Ayler and his own recordings as leader. Recordings such as Complete Communion and Symphony for Improvisers demonstrate that beauty is an integral part of free music - not just honking and screeching. These records are remarkbale for their ensemble playing and some of the first examples of the playing of soon to be famous sidemen (and women) such as Gato Barbieri.

In the late 60's and 70's, he began to experiement with Indian and African musics. As always, his music aimed at a combination of beauty and playfulness. One of my favorites from this era is Mu in which he plays alls sorts of traditional instruments as well as cornet. Fans of drumming will enjoy this because of Ed Blackwell who, for an entire hour was constantly producing new and edgy accompaniment for Cherry's music. In the 80's, Cherry began to experiment with electronic instrumentation as well as continuing to be a virtuoso acoustic musician.

He also helped introduce the pocket trumpet to jazz and was constantly experiementing - succesfully - with traditional instruments as well as electronics.

In this light, it is easily seen that Cherry was a figure that connected the bebop of the late fifties to the experiementation of the 60's and 70's. He was not just a dilletant, he had a beautiful sound and his music was a pleasure to hear. In short, he created a new approach for trumpet and extended the range of the jazz aesthetic. He truly deserves a place in the pantheon of the great jazz trumpet players.

If you have never heard Don Cherry, then I recommend hearing:

The Shape of Jazz to Come by Ornette Coleman

Complete Communion by Don Cherry

Symphony for Improvisors by Don Cherry

Mu, the Complete Session by Don Cheery and Ed Blackwell

Also see our 2013 article about Cherry's late work

| MAIN PAGE | ARTICLES | STAFF/FAVORITE MUSIC | LINKS | WRITE US |

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/the-humus-of-don-cherry-don-cherry-by-clifford-allen.php?page=1

The Humus of Don Cherry

by

"If we're going to speak about words, we could talk about a word like

'aum.' Because you don't say the word 'aum,' you sing it. And you have

to sing it where you use the 'a' as 'ah,' which is the throat. Then

you're singing, sustaining the tone 'ah.' Then you go to the 'u,' and

then you reach the 'm' and you've liberated the body. That's a word. In

the Bible they speak of the Word. First there was the Word. And then

they speak of the word that was lost." Don Cherry in an interview with

Art Taylor, in response to Taylor's question of what Cherry thought of

the word 'jazz.' Notes and Tones (Da Capo, 1977)

When I first read Taylor's interview with Don Cherry, the above statement (and indeed the entire exchange) caught me as rather funny in a far-out sort of way, and it only took a little while to realize that, despite Taylor's rather forward-thinking approach to music, he did not have a handle on the umbrella-like breadth that improvisation holds over world music, and the spiritually communicative use that most music has had throughout civilization. 'Jazz,' after all, could be a limiting term referring primarily to a regional blues-based music played in the Red-Light District of New Orleans during the early 20th Century. It is a classifying term placed on a fragment of the essence, what trumpeter Dizzy Reece has called the "cry," something that makes up the music of all cultures. As this umbrella-like form is a central aspect of Don Cherry's musical philosophy, it makes just as much sense to refer to Cherry as a 'jazz' musician as it does to discuss him as strictly a trumpeter.

Born November 18, 1936 near Oklahoma City, Cherry began playing the trumpet at age fourteen while living in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, and listened intently to Fats Navarro's work. In fact, Cherry is quoted in the liner notes to Ornette Coleman's Tomorrow is the Question (Contemporary, 1959) as saying Navarro was "the only trumpet player I cared to copy my phrases from" (considering Navarro's penchant for fast smeared soundmasses, that is a logical comparison). Cherry worked regularly with revered Los Angeles tenor man George Newman during the middle 1950s, and also played piano in a group with bassist Charlie Haden and drummer Lennie McBrowne (unfortunately, this group is not known to have recorded). Cherry and drummer Billy Higgins were rehearsing with altoist Ornette Coleman (as were Haden and drummer Ed Blackwell) who had been trying unsuccessfully to get gigs in the area. In Ornette's experience, "Don was the only trumpeter at the time able to play [this] music" (a sentiment echoed in interviews with reedmen John Tchicai and Prince Lasha) - certainly, Cherry, along with Bill Dixon and Donald Ayler, was a rare brass torchbearer in the reed-dominated nascent 'new music.' Ornette, Cherry, Haden and Higgins worked in Los Angeles at the Hillcrest Club with Paul Bley, the tapes of which became The Fabulous Paul Bley Quintet (America, 1972) and Coleman Classics (IAI, 1974). Shortly thereafter, the quartet attended the Lenox School of Jazz in Massachusetts under the direction of Gunther Schuller, where they came to the attention of Atlantic Records producers Nesuhi and Ahmet Ertegun, a relationship which lasted through enough material for nine and a half records. Recording The Shape of Jazz to Come in 1959 in fact paid for the quartet's trip east, and a subsequent three-month engagement at the Five Spot somewhat fulfilled that promise.

By 1961, however, the quartet had disbanded, with Cherry and Higgins going to work briefly in Sonny Rollins' quartet, and Jimmy Garrison (Haden's replacement) joining Coltrane's band. In the few years that followed the dissolution of the Coleman group, Cherry underwent the difficulties that can face a sideman in a noted, working ensemble striking out on his own as a leader — namely, keeping a group together as well as trying to find one's creative way. Cherry made an abortive date as leader for Savoy in 1963, featuring the loose medley that would later become "Togetherness," as played by tenor man Pharoah Sanders (in his first known session), pianist Joe Scianni, bassist David Izenzon and drummer J.C. Moses. Reedman Prince Lasha, a schoolmate of Ornette's who met Don Cherry in Los Angeles as the Coleman quartet was coming together, recorded with "Sweet Cherry" in May of 1963 at a loft session also featuring Cliff Jordan, Charles Moffett and Sonny Simmons (It Is Revealed, issued on Zounds). Following a few short-lived bands, Cherry joined the New York Contemporary Five in October 1963, replacing trumpeter Bill Dixon (suffering from embouchure difficulties, he remained the group's chief arranger). This group, with reedmen Tchicai and Archie Shepp, bassist Don Moore and the aforementioned Moses, had a successful run in Copenhagen, recording two sessions for Sonet and two for Fontana (one sans Cherry), and featuring a number of compositions from Ornette's book as well as Cherry's own "Cisum" and "Consequences." "Cisum" (from volume one of the Sonet recordings) is particularly interesting, as it shows Cherry's unique compositional style at an early stage, the theme quite obviously an outgrowth of his solo style, a jagged construction that in parts recalls Ornette's music with its bar lengths mashed together, yet utilizing North African scales and a deep minor key for its structure (not to mention a militaristic 'call' signaling its entrée).

The Five disbanded in early 1964, with Shepp and Moses staying on in Scandinavia for a few months while Cherry and Tchicai returned to New York, where the trumpeter began to work off and on with tenor man Albert Ayler and drummer Sunny Murray in their respective (and combined) groups. In a way this was perhaps more fruitful than the New York Contemporary Five had been, for not only was Ayler's music as rooted in the folk tradition as Ornette's had been, Ayler was drawing his thematic references from traditional songs he heard while living in Scandinavia, bringing them into a free improvisational context and as he has said, "we play folk from all over the world" (interview with Frank Kofsky, quoted in the liner notes to Love Cry, Impulse, 1967). This sounds a lot like what Don Cherry's approach was soon to become, and in addition to both having spent time in Scandinavia, these perfect bedfellows probably influenced one another a great deal more than their few recordings together attest to. At the very least, Ayler's recordings of "Bells" and other loosely-stitched suites of military-marches, European folk songs and Afro-American blues became de rigeur after Cherry had moved along.

"Togetherness" was the loosely frameworked suite on which Cherry built most of his concert and recording repertoire over the next three years—fragments of it show up in all three of his Blue Note LPs, despite differing titles. When Cherry left the US for Paris in 1965, it did not take long for him to assemble a new working group, one that joined five itinerant musicians together for over a year (though the group's only recordings as a unit have appeared as bootlegs since its disbanding). In Paris, he met Heidelberg-born vibraphonist and pianist Karl Berger and the young French bassist Jean-Francois Jenny-Clarke; Cherry had brought drummer Aldo Romano and Argentina-born tenor man Leandro "Gato" Barbieri with him from Rome.

Berger paints a picture of Cherry as one who functioned on a level completely beyond most other musicians; he carried a pocket-sized transistor radio with him wherever he went, listening to music from the world over, practicing tunes from Turkish folk music to the Beatles constantly and incorporating them into his suites. Often, Cherry would show up to concerts and rehearsals playing his wood flutes and with a slew of newly-found songs committed to memory, leading the affably game ensemble through an hour-long suite, the themes of which may or may not have been known beforehand. Indeed, altoist Carlos Ward, a later associate of Cherry's who worked with the trumpeter and composer in various aggregations throughout the '70s, had one of his most telling moments as a soloist on Relativity Suite (JCOA, 1973) in a subsection called "Desireles," one that Ward felt seemed written exactly for him. "It could have been already named, because I didn't know. A lot of songs Don would bring in, maybe he has titles to them but he didn't say. There was one piece that he would bring to every gig [I played with him], and he'd bring a little bit more each time, but he never played the whole piece... it was a composition in progress." The Durium recording, which focuses on the actual "Togetherness" suite, displays a somewhat ragtag quality of 'practicing on the stand,' but indeed this was probably the most-rehearsed material in the group's repertoire, its multiple themes introduced at will by references in solos and calling upon familiarity and flexibility as much as instrumental prowess. It is entirely possible that the other four members of the group did not know what they were going to be playing for the recording date—Monk, highlife, or one of Cherry's tunes, it was all part of "Togetherness."

While Berger and Barbieri eventually became ensconced in the New York

scene, the former going on to form the Creative Music Studio at

Woodstock in 1968, Cherry split his time between Scandinavia (he kept a

home in Sweden with his wife Mocqui and son Lanoo Eagle Eye) and the

United States, convening orchestras and small groups for regular

expansions and reworkings of "Togetherness," including those at the

Baden-Baden New Jazz Meeting of 1968 (Eternal Rhythm, MPS) and

in 1971 at the Berlin Jazz Days ("Humus," with the New Eternal Rhythm

Orchestra, on Actions, Philips), and a trio he led with bassist Johnny

Dyani and Turkish drummer Okay Temiz. Cherry's music, while it had

incorporated non-Western scales, began now to incorporate drones more

regularlyh and making explicit use of instruments like the tamboura

(going perhaps farther than a two-bass concept). Cherry, a collector of

various wooden and metal flutes from Asia, also began using the

doussn'gouni, a Malian stringed instrument he was exposed to while in

Scandinavia. Ironically, some of the most interesting and effective uses

of non-Western instruments were purely by kismet. For example, Joachim

Berendt had a gamelan brought to Baden-Baden without telling Cherry, and

insisted that it be used in the recording. Berger, Cherry and Swiss

drummer Jaques Thollot were thus given the task of figuring out a way to

incorporate them musically without proper understanding of how they are

played, or even without proper mallets with which to play them. The

high-pitched metallic tone that characterizes their sound on Eternal Rhythm

is more greatly a result of 'making do' than sonic intent. In the hands

of another ensemble, one has to wonder whether it would have come off

at all.

In a way, all of "Togetherness" — the incorporation of a myriad of themes and instruments to a work in progress — would mean nothing if it were not done with human growth in mind. To be sure, incorporating such a wide-ranging lexicon into the 'jazz' or 'free jazz' framework is a start, but Cherry could not stop there. The live recordings of both his trio and "Humus" include a great amount of group-audience interaction, with Cherry teaching concertgoers the proper way to say the phrase 'Si Ta Ra Ma' (later revisited in full song form with Dutch percussionist Han Bennink on Don Cherry, BYG, 1971) as a way into the heart of the music itself. In another context, the sing-along might seem hokey, but here it is done with utmost sincerity at giving concertgoers the opportunity not to merely listen, but to learn and understand, whether or not they are formal musicians. At the Workshop Freie Musik in 1971, Cherry and the Peter Brötzmann Trio held a workshop entitled "Free Jazz and Children," in which approximately 200 children with no musical experience were brought into a semi-classroom situation with instruments and four improvisers. Granted, according to Brötzmann it was not a complete success (mainly due to so many people showing up), but did lead to further experiments with children and improvisers as part of the "Kinder und Künst" program under the direction of Germany's Council on the Arts.

"Don Cherry had an effect on people everywhere he went, because whenever he was in town, everybody would show up... things started happening around him because he was such a fun person to be around," so the words of Swedish percussionist Bengt Berger, who met Cherry in the early 1960s during the trumpeter's initial stay in Scandinavia. Indeed, Cherry's music is often associated very closely with the Scandinavian new music community, including such luminaries as Swedish reedmen Bernt Rosengren and Bengt 'Frippe' Nordstrom (whose album of duets with Cherry is the scarcest European jazz album), multi-instrumentalist Christer Bothen (noted for his playing of the dousson'gouni) and Norwegian bassist Arild Andersen. As a leader, Cherry recorded two sessions for Swedish labels Sonet and Caprice (including the eponymous Organic Music Society, 1971) in addition to having a huge structural influence on groups like Gunnar Lindquist's G.L. Unit (Orangutang!, EMI, 1970) and the work of Danish trumpeter-composer Hugh Steinmetz, who met Cherry in 1963 when the New York Contemporary Five visited Copenhagen. Cherry and his then-wife Mocqui bought a one-room schoolhouse in Togarten, Sweden, which became one of his principal home bases (this, in fact, was where Carlos Ward began working with him). Bengt Berger also began working with Cherry around this time: "I had been to India and had studied tabla, which he got very interested in, so we got to playing a lot, and I stayed for a long time at his house in Sweden and going on European tours [with him] as well." One of the focal points for the new music in Sweden was Stockholm's Moderna Museet, which had a geodesic dome at the time that the musicians played in — Cherry, Rosengren, Berger — allowing many of the young musicians to meet one another, as well as play with visiting musicians from other countries. Certainly, Cherry was galvanizing musicians in New York and Paris, but the European country which might qualify most as a spiritual home seemed to be Sweden. Perhaps this was because of several highly-skilled players of non-Western instruments in Stockholm, perhaps because of the rich folk heritage of the region, but whatever the reason, it bears mentioning that Don Cherry had a strong presence among this community in particular.

For sure, Cherry's integration of Indian, Arabic, Chinese, European and African musics into a whole of which jazz was only a small fraction could have come at no more proper a time — the interest among American and European audiences in non-Western music was at the time fairly high, and consequently Cherry's music gained greater recognition than it might have otherwise. In the 1970s, he recorded for Atlantic and A&M and had a minor hit with "Brown Rice" (as might be expected, one of the stylistically least-indicative pieces that could have been chosen), as well as working in small and large groups with South African pianist-composer Abdullah Ibrahim, often featuring Ward. Nu, though not recorded to advantage, was one of Cherry's most fully integrated projects of the 1980s, one that featured Ward, bassist Mark Helias and percussionist Nana Vasconcelos as an extension of both jazz and non-Western improvisational principles along folk lines, swinging decidedly to the left of either Old and New Dreams (the cooperative band with tenor man Dewey Redman, Haden and Blackwell that revisited the Ornette songbook) or his various traditional music projects often heralded under the 'multi-kulti' banner (indeed, Cherry did cut a record with that very title, for ECM), rather than as investigation of improvisational art along worldwide folk principles, often set simultaneously. Ward, indeed, found 'Nu' to be one of his most important associations, for the very reason that one foot was decidedly within the jazz spectrum — that no matter how divergent his creative search became, the 'cry' was a necessary part of Cherry's music.

Cherry often spoke of the idea of "selflessness" and of being "aboriginal," a concept which percussionist Adam Rudolph, curator of this month's Don Cherry Celebration at the Stone Gallery and a longtime collaborator of Cherry from 1978 until his death in 1995, has taken to heart and mind. Cherry, of course, never stayed in one place completely, spending time principally in Sweden, New York, and California during the last two decades of his life, but musically his practice took him everywhere. Percussionist Bengt Berger, who played with Cherry frequently in Sweden, noted how Cherry's curiosity led him to teach Turkish drummer Okay Temiz and trumpeter Maffay Falay the fundamental principles of Turkish folk music by asking them to teach him their musical culture—Berger: "he kind of put them onto their own folk music by being very interested in that. Then they started a Turkish group [of their own]." Rather than simply learning to play the music of another region or culture by rote was certainly far from Cherry's mind; part of this 'aboriginalness' was an effort to gain a clearer window into oneself and one's own creative possibilities, that one can become more fully attuned to one's artistic personality by incorporating aspects of other musics into the palette. In some ways, it reflects the age-old adage that one has to get as far away from oneself as possible in order to fully understand where one lies creatively and humanistically—an aesthetic walkabout, in other words. Don Cherry's walkabout took him to Brooklyn, Scandinavia, Turkey, Los Angeles, Paris, India and places in-between, but as an artist, it brought him home.

Thanks to Adam Rudolph, Karl Berger, Carlos Ward, Prince Lasha, Ornette Coleman, Bengt Berger, and all the artists interviewed for this project.

Photo Credit: Jack Vartoogian/Front Row Photos

http://soundamerican.org/sa_archive/sa14/index.html

It’s an axiom, and one that is ultimately relatable to this issue’s central figure, Don Cherry. But, before we go any further, I want to present a separate axiomatic phrase that envelops the broader working philosophy of Sound American, this time from Benjamin Disraeli:

“Change is inevitable. Change is constant.”

In order to quickly veer away from the territory of the precocious teen using his sister’s copy of Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations to pad out a five-page paper on the Marshall Plan, let’s explore how these two postulates relate to the pages within Sound American Issue 14.

Trumpet player, improviser, and world-music iconoclast Don Cherry was easily my least favorite artist on the instrument when I was growing up. Preferring the more conservative and controlled frenetic style of the late Miles Davis or Booker Little, I couldn’t hear past the lack of definition in Cherry’s phrasing to get to the heart of what he was doing. Over time, however, the way I understood his playing changed from indistinct, splattered lazy missed pitches to profoundly personal arcs of sonic color. My perception of his music developed, and I began to marvel at his ability to create and maintain such a powerful personal musical persona.

With this new appreciation, I became fascinated by a specific period in the early 1960s during which Cherry, aside from his consistent work with Ornette Coleman, played on some of the most definitive recordings of the free jazz era. The thing that I found intriguing was that he, for all intents and purposes, wasn’t a leader on any of them. From The Avant-Garde with John Coltrane to Evidence with Steve Lacy and a small catalog of recordings with Albert Ayler, Archie Shepp, Sonny Rollins, and Pharoah Sanders in between, Don Cherry was a somewhat ubiquitous presence on the great free jazz records of the 1960s.

Given the unique nature of Cherry’s improvising, his presence on all these records is not so unusual, but what Don Cherry does on those recordings has fueled a lot of questions in my mind, ultimately culminating here in an entire issue devoted to that period. At least that was the plan before Disraeli’s axiom of change, ever looming in the Sound American office, was asserted.

What is it about Don Cherry that made him able to sound so utterly unique while framing saxophonists as iconic as John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins in a sort of light they would never quite experience again? That was the question I wanted to tackle, but as the first interviews—meant to simply provide a back story for the grand thrust of this issue—began to take shape, it became clear that the influence of the man was not going to be contained in such a simple and limited question. Not to put too fine a point on it, change was inevitable.

It immediately became clear that the experience of Don Cherry could not be limited to a handful of classic records. At the very least, it is essential to look at his career as an arc in the same way we may view Miles Davis and his many stylistic periods. Cherry was as radical in his changes as Davis, if perhaps more quiet about it. His own music could hardly be called a foray into the music of other cultures and traditions, because it doesn’t exist only as a passing interest or surface level exercise. Instead, he absorbed the music of Africa and the Middle East, and what came out was something that had inflection and influence but no sense of artificial fusion. His music has this quality because, as all of the interview subjects who had met Cherry have stated in their own way, to him all music is music.

This issue’s initial interviews and articles all tangentially answer the original question of how Cherry affected those early 1960s recordings, but always through the lens of this broader philosophy. Percussionist Hamid Drake, who played in the trumpeter’s last bands, talks about Cherry’s freedom with his musicians and his ability to “orchestrate his individual voice into any situation.” Cornetist Graham Haynes tells stories about Cherry’s giving spirit and citizenship of the world. William Parker, in conversation with special guest contributor Jeremiah Cymerman, paints a picture of the Lower East Side of the 1970s in which Don Cherry was a constant, open, and friendly presence.

In all of these cases, Cherry’s confidence in his own sound and his magnanimity of spirit are given as approximate answers to what may have been the reason he was able to convincingly play Thelonious Monk tunes with Steve Lacy and Ghosts with Albert Ayler. To stop there, though, would be to miss his greater purpose. Far from being an island, as in Donne’s axiom, Don Cherry was a wide-reaching, permanent, and high-speed mass transit system. For every analysis of his work with Ornette Coleman, [world-music trio] Codona, or [bassist] Charlie Haden, there are three apocryphal stories of his generosity and support for the musicians he played with regularly or met once in passing.

As the articles for this issue accrue, it will become obvious that this sense of giving and openness is the true power of Don Cherry the musician and the human being. Not only that, but it continues to be so, long after his physical body has left us. As improvisers such as Chad Taylor, Ralph Alessi, Tomas Fujiwara, Jon Irabagon, and Taylor Ho Bynum each try to explain Cherry’s special quality in relation to a specific recording from that magical early-60s period, it instantly becomes clear that he has and will continue to live on in subsequent generations.

For those who have no experience of Don Cherry’s music, and for those who just want an excuse to spend an afternoon revisiting his history, this issue includes a narrative biography and a page of performance footage. It is my suggestion that the reader and listener start here to get a sense of the feeling of Don Cherry so they can make the most out of the interviews and appreciations to come. Although it is a very small, and by no means complete, cross-section of those who have been influenced directly or indirectly by Don Cherry, each has been chosen because of his ability to articulate the specific magic of the man.

-–Nate Wooley, Editor-in-Chief

Cherry was born on November 18, 1936, in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, and was surrounded by music from an early age. Both his mother and grandmother played piano, and his father owned The Cherry Blossom Club, a venue that hosted some of the great swing bands of the time as they traveled through the Great Plains. In 1940, the family moved westward to Los Angeles, where Cherry’s father worked at the Plantation Club, an essential jazz spot in the Watts neighborhood of South L.A.

Although he was initially enrolled in Fremont High School in the South Central neighborhood of the city, Cherry often ditched classes to sit in with the big band of nearby Jefferson High instead. Jefferson was well known at the time for producing some of bebop and cool jazz’s biggest stars, such as saxophonists Dexter Gordon and Wardell Gray and flugelhorn player Art Farmer. Samuel Brown, the instructor of Jefferson High’s dance band, allowed Don to play, although it is unclear if he knew that Cherry was not officially enrolled.* His truancy ultimately led to Cherry being transferred to an area reform school, where he met and forged a long-lasting friendship with drummer Billy Higgins.

When I first read Taylor's interview with Don Cherry, the above statement (and indeed the entire exchange) caught me as rather funny in a far-out sort of way, and it only took a little while to realize that, despite Taylor's rather forward-thinking approach to music, he did not have a handle on the umbrella-like breadth that improvisation holds over world music, and the spiritually communicative use that most music has had throughout civilization. 'Jazz,' after all, could be a limiting term referring primarily to a regional blues-based music played in the Red-Light District of New Orleans during the early 20th Century. It is a classifying term placed on a fragment of the essence, what trumpeter Dizzy Reece has called the "cry," something that makes up the music of all cultures. As this umbrella-like form is a central aspect of Don Cherry's musical philosophy, it makes just as much sense to refer to Cherry as a 'jazz' musician as it does to discuss him as strictly a trumpeter.

Born November 18, 1936 near Oklahoma City, Cherry began playing the trumpet at age fourteen while living in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, and listened intently to Fats Navarro's work. In fact, Cherry is quoted in the liner notes to Ornette Coleman's Tomorrow is the Question (Contemporary, 1959) as saying Navarro was "the only trumpet player I cared to copy my phrases from" (considering Navarro's penchant for fast smeared soundmasses, that is a logical comparison). Cherry worked regularly with revered Los Angeles tenor man George Newman during the middle 1950s, and also played piano in a group with bassist Charlie Haden and drummer Lennie McBrowne (unfortunately, this group is not known to have recorded). Cherry and drummer Billy Higgins were rehearsing with altoist Ornette Coleman (as were Haden and drummer Ed Blackwell) who had been trying unsuccessfully to get gigs in the area. In Ornette's experience, "Don was the only trumpeter at the time able to play [this] music" (a sentiment echoed in interviews with reedmen John Tchicai and Prince Lasha) - certainly, Cherry, along with Bill Dixon and Donald Ayler, was a rare brass torchbearer in the reed-dominated nascent 'new music.' Ornette, Cherry, Haden and Higgins worked in Los Angeles at the Hillcrest Club with Paul Bley, the tapes of which became The Fabulous Paul Bley Quintet (America, 1972) and Coleman Classics (IAI, 1974). Shortly thereafter, the quartet attended the Lenox School of Jazz in Massachusetts under the direction of Gunther Schuller, where they came to the attention of Atlantic Records producers Nesuhi and Ahmet Ertegun, a relationship which lasted through enough material for nine and a half records. Recording The Shape of Jazz to Come in 1959 in fact paid for the quartet's trip east, and a subsequent three-month engagement at the Five Spot somewhat fulfilled that promise.

By 1961, however, the quartet had disbanded, with Cherry and Higgins going to work briefly in Sonny Rollins' quartet, and Jimmy Garrison (Haden's replacement) joining Coltrane's band. In the few years that followed the dissolution of the Coleman group, Cherry underwent the difficulties that can face a sideman in a noted, working ensemble striking out on his own as a leader — namely, keeping a group together as well as trying to find one's creative way. Cherry made an abortive date as leader for Savoy in 1963, featuring the loose medley that would later become "Togetherness," as played by tenor man Pharoah Sanders (in his first known session), pianist Joe Scianni, bassist David Izenzon and drummer J.C. Moses. Reedman Prince Lasha, a schoolmate of Ornette's who met Don Cherry in Los Angeles as the Coleman quartet was coming together, recorded with "Sweet Cherry" in May of 1963 at a loft session also featuring Cliff Jordan, Charles Moffett and Sonny Simmons (It Is Revealed, issued on Zounds). Following a few short-lived bands, Cherry joined the New York Contemporary Five in October 1963, replacing trumpeter Bill Dixon (suffering from embouchure difficulties, he remained the group's chief arranger). This group, with reedmen Tchicai and Archie Shepp, bassist Don Moore and the aforementioned Moses, had a successful run in Copenhagen, recording two sessions for Sonet and two for Fontana (one sans Cherry), and featuring a number of compositions from Ornette's book as well as Cherry's own "Cisum" and "Consequences." "Cisum" (from volume one of the Sonet recordings) is particularly interesting, as it shows Cherry's unique compositional style at an early stage, the theme quite obviously an outgrowth of his solo style, a jagged construction that in parts recalls Ornette's music with its bar lengths mashed together, yet utilizing North African scales and a deep minor key for its structure (not to mention a militaristic 'call' signaling its entrée).

The Five disbanded in early 1964, with Shepp and Moses staying on in Scandinavia for a few months while Cherry and Tchicai returned to New York, where the trumpeter began to work off and on with tenor man Albert Ayler and drummer Sunny Murray in their respective (and combined) groups. In a way this was perhaps more fruitful than the New York Contemporary Five had been, for not only was Ayler's music as rooted in the folk tradition as Ornette's had been, Ayler was drawing his thematic references from traditional songs he heard while living in Scandinavia, bringing them into a free improvisational context and as he has said, "we play folk from all over the world" (interview with Frank Kofsky, quoted in the liner notes to Love Cry, Impulse, 1967). This sounds a lot like what Don Cherry's approach was soon to become, and in addition to both having spent time in Scandinavia, these perfect bedfellows probably influenced one another a great deal more than their few recordings together attest to. At the very least, Ayler's recordings of "Bells" and other loosely-stitched suites of military-marches, European folk songs and Afro-American blues became de rigeur after Cherry had moved along.

"Togetherness" was the loosely frameworked suite on which Cherry built most of his concert and recording repertoire over the next three years—fragments of it show up in all three of his Blue Note LPs, despite differing titles. When Cherry left the US for Paris in 1965, it did not take long for him to assemble a new working group, one that joined five itinerant musicians together for over a year (though the group's only recordings as a unit have appeared as bootlegs since its disbanding). In Paris, he met Heidelberg-born vibraphonist and pianist Karl Berger and the young French bassist Jean-Francois Jenny-Clarke; Cherry had brought drummer Aldo Romano and Argentina-born tenor man Leandro "Gato" Barbieri with him from Rome.

Berger paints a picture of Cherry as one who functioned on a level completely beyond most other musicians; he carried a pocket-sized transistor radio with him wherever he went, listening to music from the world over, practicing tunes from Turkish folk music to the Beatles constantly and incorporating them into his suites. Often, Cherry would show up to concerts and rehearsals playing his wood flutes and with a slew of newly-found songs committed to memory, leading the affably game ensemble through an hour-long suite, the themes of which may or may not have been known beforehand. Indeed, altoist Carlos Ward, a later associate of Cherry's who worked with the trumpeter and composer in various aggregations throughout the '70s, had one of his most telling moments as a soloist on Relativity Suite (JCOA, 1973) in a subsection called "Desireles," one that Ward felt seemed written exactly for him. "It could have been already named, because I didn't know. A lot of songs Don would bring in, maybe he has titles to them but he didn't say. There was one piece that he would bring to every gig [I played with him], and he'd bring a little bit more each time, but he never played the whole piece... it was a composition in progress." The Durium recording, which focuses on the actual "Togetherness" suite, displays a somewhat ragtag quality of 'practicing on the stand,' but indeed this was probably the most-rehearsed material in the group's repertoire, its multiple themes introduced at will by references in solos and calling upon familiarity and flexibility as much as instrumental prowess. It is entirely possible that the other four members of the group did not know what they were going to be playing for the recording date—Monk, highlife, or one of Cherry's tunes, it was all part of "Togetherness."

In a way, all of "Togetherness" — the incorporation of a myriad of themes and instruments to a work in progress — would mean nothing if it were not done with human growth in mind. To be sure, incorporating such a wide-ranging lexicon into the 'jazz' or 'free jazz' framework is a start, but Cherry could not stop there. The live recordings of both his trio and "Humus" include a great amount of group-audience interaction, with Cherry teaching concertgoers the proper way to say the phrase 'Si Ta Ra Ma' (later revisited in full song form with Dutch percussionist Han Bennink on Don Cherry, BYG, 1971) as a way into the heart of the music itself. In another context, the sing-along might seem hokey, but here it is done with utmost sincerity at giving concertgoers the opportunity not to merely listen, but to learn and understand, whether or not they are formal musicians. At the Workshop Freie Musik in 1971, Cherry and the Peter Brötzmann Trio held a workshop entitled "Free Jazz and Children," in which approximately 200 children with no musical experience were brought into a semi-classroom situation with instruments and four improvisers. Granted, according to Brötzmann it was not a complete success (mainly due to so many people showing up), but did lead to further experiments with children and improvisers as part of the "Kinder und Künst" program under the direction of Germany's Council on the Arts.

"Don Cherry had an effect on people everywhere he went, because whenever he was in town, everybody would show up... things started happening around him because he was such a fun person to be around," so the words of Swedish percussionist Bengt Berger, who met Cherry in the early 1960s during the trumpeter's initial stay in Scandinavia. Indeed, Cherry's music is often associated very closely with the Scandinavian new music community, including such luminaries as Swedish reedmen Bernt Rosengren and Bengt 'Frippe' Nordstrom (whose album of duets with Cherry is the scarcest European jazz album), multi-instrumentalist Christer Bothen (noted for his playing of the dousson'gouni) and Norwegian bassist Arild Andersen. As a leader, Cherry recorded two sessions for Swedish labels Sonet and Caprice (including the eponymous Organic Music Society, 1971) in addition to having a huge structural influence on groups like Gunnar Lindquist's G.L. Unit (Orangutang!, EMI, 1970) and the work of Danish trumpeter-composer Hugh Steinmetz, who met Cherry in 1963 when the New York Contemporary Five visited Copenhagen. Cherry and his then-wife Mocqui bought a one-room schoolhouse in Togarten, Sweden, which became one of his principal home bases (this, in fact, was where Carlos Ward began working with him). Bengt Berger also began working with Cherry around this time: "I had been to India and had studied tabla, which he got very interested in, so we got to playing a lot, and I stayed for a long time at his house in Sweden and going on European tours [with him] as well." One of the focal points for the new music in Sweden was Stockholm's Moderna Museet, which had a geodesic dome at the time that the musicians played in — Cherry, Rosengren, Berger — allowing many of the young musicians to meet one another, as well as play with visiting musicians from other countries. Certainly, Cherry was galvanizing musicians in New York and Paris, but the European country which might qualify most as a spiritual home seemed to be Sweden. Perhaps this was because of several highly-skilled players of non-Western instruments in Stockholm, perhaps because of the rich folk heritage of the region, but whatever the reason, it bears mentioning that Don Cherry had a strong presence among this community in particular.

For sure, Cherry's integration of Indian, Arabic, Chinese, European and African musics into a whole of which jazz was only a small fraction could have come at no more proper a time — the interest among American and European audiences in non-Western music was at the time fairly high, and consequently Cherry's music gained greater recognition than it might have otherwise. In the 1970s, he recorded for Atlantic and A&M and had a minor hit with "Brown Rice" (as might be expected, one of the stylistically least-indicative pieces that could have been chosen), as well as working in small and large groups with South African pianist-composer Abdullah Ibrahim, often featuring Ward. Nu, though not recorded to advantage, was one of Cherry's most fully integrated projects of the 1980s, one that featured Ward, bassist Mark Helias and percussionist Nana Vasconcelos as an extension of both jazz and non-Western improvisational principles along folk lines, swinging decidedly to the left of either Old and New Dreams (the cooperative band with tenor man Dewey Redman, Haden and Blackwell that revisited the Ornette songbook) or his various traditional music projects often heralded under the 'multi-kulti' banner (indeed, Cherry did cut a record with that very title, for ECM), rather than as investigation of improvisational art along worldwide folk principles, often set simultaneously. Ward, indeed, found 'Nu' to be one of his most important associations, for the very reason that one foot was decidedly within the jazz spectrum — that no matter how divergent his creative search became, the 'cry' was a necessary part of Cherry's music.

Cherry often spoke of the idea of "selflessness" and of being "aboriginal," a concept which percussionist Adam Rudolph, curator of this month's Don Cherry Celebration at the Stone Gallery and a longtime collaborator of Cherry from 1978 until his death in 1995, has taken to heart and mind. Cherry, of course, never stayed in one place completely, spending time principally in Sweden, New York, and California during the last two decades of his life, but musically his practice took him everywhere. Percussionist Bengt Berger, who played with Cherry frequently in Sweden, noted how Cherry's curiosity led him to teach Turkish drummer Okay Temiz and trumpeter Maffay Falay the fundamental principles of Turkish folk music by asking them to teach him their musical culture—Berger: "he kind of put them onto their own folk music by being very interested in that. Then they started a Turkish group [of their own]." Rather than simply learning to play the music of another region or culture by rote was certainly far from Cherry's mind; part of this 'aboriginalness' was an effort to gain a clearer window into oneself and one's own creative possibilities, that one can become more fully attuned to one's artistic personality by incorporating aspects of other musics into the palette. In some ways, it reflects the age-old adage that one has to get as far away from oneself as possible in order to fully understand where one lies creatively and humanistically—an aesthetic walkabout, in other words. Don Cherry's walkabout took him to Brooklyn, Scandinavia, Turkey, Los Angeles, Paris, India and places in-between, but as an artist, it brought him home.

Thanks to Adam Rudolph, Karl Berger, Carlos Ward, Prince Lasha, Ornette Coleman, Bengt Berger, and all the artists interviewed for this project.

Photo Credit: Jack Vartoogian/Front Row Photos

http://soundamerican.org/sa_archive/sa14/index.html

SA14: The Don Cherry Issue

“No man is an island.” —John Donne

It’s an axiom, and one that is ultimately relatable to this issue’s central figure, Don Cherry. But, before we go any further, I want to present a separate axiomatic phrase that envelops the broader working philosophy of Sound American, this time from Benjamin Disraeli:

“Change is inevitable. Change is constant.”