SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER/FALL, 2017

VOLUME FOUR NUMBER THREE

ESPERANZA SPALDING

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

JAZZMEIA HORN

(August 12-18)

ROY HAYNES

(August 19-25)

MCCOY TYNER

(August 26-September 1)

AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE

(September 2-8)

AARON DIEHL

(September 9-15)

CECILE MCLORIN SALVANT

(September 16-22)

REGGIE WORKMAN

(September 23-29)

ANDREW CYRILLE

(September 30-October 6)

BARRY HARRIS

BARRY HARRIS

(October 7-13)

MARQUIS HILL

(October 14-20)

HERBIE NICHOLS

(October 21-27)

GREG OSBY

(October 28-November 3)

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/reggie-workman-mn0000884932/biography

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/reggie-workman-mn0000884932/biography

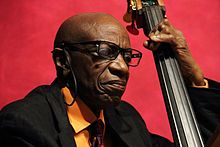

Reggie Workman

(b. June 26, 1937)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

Reggie Workman

has long been one of the most technically gifted of all bassists, a

brilliant player whose versatile style fits into both hard bop and very

avant-garde settings. He played piano, tuba, and euphonium early on but

settled on bass in the mid-'50s. After working regularly with Gigi Gryce (1958), Red Garland, and Roy Haynes, he was a member of the John Coltrane Quartet for much of 1961, participating in several important recordings and even appearing with Coltrane and Eric Dolphy on a half-hour West German television show that is currently available on video (The Coltrane Legacy). After Jimmy Garrison took his place with Coltrane, Workman became a member of Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers (1962-1964) and was in the groups of Yusef Lateef (1964-65), Herbie Mann, and Thelonious Monk (1967). He recorded frequently in the 1960s (including many Blue Note dates and Archie Shepp's classic Four for Trane).

Since that time, Workman has been both an educator (serving on the faculty of music schools including the University of Michigan) and a working musician, and has played with numerous legendary jazz musicians including Max Roach, Art Farmer, Mal Waldron, David Murray, Sam Rivers, and Andrew Hill (Rivers and Hill joined Workman for the 1993 session, Summit Conference). In the 1980s, Workman began leading his own group, the Reggie Workman Ensemble. He also began a collaboration with pianist Marilyn Crispell that lasted into the next decade (the two acclaimed musicians reunited for a festival performance in 2000). During the '90s, Workman was not only active with his own ensemble, but also in Trio Three, with Andrew Cyrille and Oliver Lake, and Reggie Workman's Grooveship and Extravaganza. In recognition of Reggie Workman's international performances and recordings spanning over 40 years, he was named a Living Legend by the African-American Historical and Cultural Museum in his hometown of Philadelphia; he is also a recipient of the Eubie Blake Award.

http://www.furious.com/perfect/reggieworkman.html

Reggie wouldn't remember me, but we met when I was in an Afro-American music appreciation course when I was at the University of Massachusetts Amherst campus in the spring of 1974. It was a tremendous time to be on that campus for any fan of creative music. I had just "discovered" avant garde jazz or "the new thing" as it was called in the summer of 1971, when I saw the Ornette Coleman Quartet with Dewey Redman, Charlie Haden, and Ed Blackwell close out a Saturday afternoon show at the Newport Jazz Festival. Entranced and energized, my friends and I watched in amazement as Ornette took bold stabs at the violin and trumpet, Charlie Haden used a bow and wah wah pedal on an acoustic bass, Dewey Redman pulled massive sound out of his tenor and Ed Blackwell danced with his sticks on the drums. My friends and I, as fledgling musicians, had started checking out jazz earlier after reading about some of the influences of Frank Zappa (check out the inside cover of Freak Out for an outstanding reference list), the Nice, Spirit, Soft Machine and other jazz-inspired bands and my drummer friend had picked up some Elvin Jones and while I had picked up some Coltrane (more on this later), Wayne Shorter and John Handy--but Ornette provided a new world of reference. As I enter my sophomore year at UMass, I am pumped up to see more daring musicians. Gary Burton and Dizzy Gillespie had shown up my freshman year, but as much as I loved Diz, I fell asleep during the concert (I was studying pretty hard my freshman year--don't laugh, it was true and I had the cumulative point average to prove it), but by the time I made it to sophomore year, I wanted more. So, at the start of my sophomore year, I start a band with two guys I met at Newport (the Coleman concert was the day before the fences were broken down when Dionne Warwick was singing and they cancelled the rest of the festival, ruining my chances to see the classic Soft Machine quartet live, and essentially kicking adventurous jazz out of Newport forever), one of whom was the esteemed Enrique Jardines, bassist for Absolute Zero, of whom I have written much. I had also run for Student Senate and get elected on the promise to bring live rock music to UMass again (it had been banned the previous year because of a bizarre concert incidents, the details of which I shan't reveal here). So most of my sophomore year was engaged in the band, the concert committee, a girl friend, and other distractions that got me in a heap of trouble with the administration, because I was pumped up, truth be told. However, a group of us did get live concerts back at UMass (Fleetwood Mac-three guitarists edition- headlining).

Workman had started his musical studies by playing piano, then progressed toward the double bass later. His early friendships included trumpeter Lee Morgan, who he reported in an All About Jazz interview, had a huge record collection, and he went on to record as a member of groups led by Gigi Gryce, super drummer Roy Haynes, Wayne Shorter and Red Garland, finally hitting the point for which he has the most fame, replacing Steve Davis in John Coltrane's Quartet. Despite taking part in some landmark recordings (Coltrane's composition "India", reportedly influenced quite a few ‘60's rockers-Roger McGuinn of the Byrds reports that the group played that recording repeatedly in the months prior to recording "Eight Miles High," for one example), family obligations, mainly his father's illness and subsequent death, caused him to leave the quartet. There, he was replaced by Jimmy Garrison, in what was the best known incarnation of Coltrane's quartet, with McCoy Tyner on piano and Elvin Jones on drums.

Mr. Workman also devoted a significant part of his life to teaching at the university level--many, many years at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, time served at Bennington College, the University of Michigan, and full associate professor at New York's New School for music. He has also been involved in music education in a community setting, helping to found the Collective Black Artists. He is also currently the co-director of the Montclair Academy and serves as founder of the Sculptured Sounds Music Festival, an artist-driven festival of futuristic music and concepts held every Sunday in February in New York.

Since that time, Workman has been both an educator (serving on the faculty of music schools including the University of Michigan) and a working musician, and has played with numerous legendary jazz musicians including Max Roach, Art Farmer, Mal Waldron, David Murray, Sam Rivers, and Andrew Hill (Rivers and Hill joined Workman for the 1993 session, Summit Conference). In the 1980s, Workman began leading his own group, the Reggie Workman Ensemble. He also began a collaboration with pianist Marilyn Crispell that lasted into the next decade (the two acclaimed musicians reunited for a festival performance in 2000). During the '90s, Workman was not only active with his own ensemble, but also in Trio Three, with Andrew Cyrille and Oliver Lake, and Reggie Workman's Grooveship and Extravaganza. In recognition of Reggie Workman's international performances and recordings spanning over 40 years, he was named a Living Legend by the African-American Historical and Cultural Museum in his hometown of Philadelphia; he is also a recipient of the Eubie Blake Award.

http://www.furious.com/perfect/reggieworkman.html

REGGIE WORKMAN

Supreme Skill and Humility

by Gary Gomes

(FEBRUARY 2013)

Reggie wouldn't remember me, but we met when I was in an Afro-American music appreciation course when I was at the University of Massachusetts Amherst campus in the spring of 1974. It was a tremendous time to be on that campus for any fan of creative music. I had just "discovered" avant garde jazz or "the new thing" as it was called in the summer of 1971, when I saw the Ornette Coleman Quartet with Dewey Redman, Charlie Haden, and Ed Blackwell close out a Saturday afternoon show at the Newport Jazz Festival. Entranced and energized, my friends and I watched in amazement as Ornette took bold stabs at the violin and trumpet, Charlie Haden used a bow and wah wah pedal on an acoustic bass, Dewey Redman pulled massive sound out of his tenor and Ed Blackwell danced with his sticks on the drums. My friends and I, as fledgling musicians, had started checking out jazz earlier after reading about some of the influences of Frank Zappa (check out the inside cover of Freak Out for an outstanding reference list), the Nice, Spirit, Soft Machine and other jazz-inspired bands and my drummer friend had picked up some Elvin Jones and while I had picked up some Coltrane (more on this later), Wayne Shorter and John Handy--but Ornette provided a new world of reference. As I enter my sophomore year at UMass, I am pumped up to see more daring musicians. Gary Burton and Dizzy Gillespie had shown up my freshman year, but as much as I loved Diz, I fell asleep during the concert (I was studying pretty hard my freshman year--don't laugh, it was true and I had the cumulative point average to prove it), but by the time I made it to sophomore year, I wanted more. So, at the start of my sophomore year, I start a band with two guys I met at Newport (the Coleman concert was the day before the fences were broken down when Dionne Warwick was singing and they cancelled the rest of the festival, ruining my chances to see the classic Soft Machine quartet live, and essentially kicking adventurous jazz out of Newport forever), one of whom was the esteemed Enrique Jardines, bassist for Absolute Zero, of whom I have written much. I had also run for Student Senate and get elected on the promise to bring live rock music to UMass again (it had been banned the previous year because of a bizarre concert incidents, the details of which I shan't reveal here). So most of my sophomore year was engaged in the band, the concert committee, a girl friend, and other distractions that got me in a heap of trouble with the administration, because I was pumped up, truth be told. However, a group of us did get live concerts back at UMass (Fleetwood Mac-three guitarists edition- headlining).

But while all this was going on, I was astonished to find that Archie Shepp was visiting my campus. I saw him speak, saw him play, and the following year, in 1972, he came on board as faculty, with Max Roach, the legendary drummer, and Reggie Workman. In another legendary moment, both Sun Ra and Sam Rivers came to UMass to play in 1973 and almost the entire AACM of Chicago--minus the Art Ensemble of Chicago and the Revolutionary Ensemble--played there in 1974.

After Reggie Workman was placed on the University of Massachusetts faculty in 1973, a marvelous appreciation of his craft developed on my part (I know it was a big lead-in, but you're here now, and aren't you happy to have finally arrived?).

Reggie was perhaps most widely known for his time with John Coltrane. He was a member of Coltrane's group and can be heard most frequently on Coltrane's recording of the Coltrane classic "India" in which he sets up a tambura-like drone with fellow bassist Jimmy Garrison. There are rumors that Workman could have become the permanent bassist for Coltrane were it not for the unfortunate prospect of the military draft looming in his face during the Vietnam conflict. Shortly before Garrison played with Coltrane, he played for Coleman and, according to Coleman in A.B. Spellman's Black Music: Four Lives, he grew frustrated playing with Coleman, subsequently leaving for Coltrane. One can understand why; at least with Coltrane. At that time, Coltrane was involved with modal improvisation which rendered a key center. Coleman often took keys as suggestions, so the sound was not as grounded in familiar territory as Coltrane's was. Eventually, Coltrane moved to more extreme territory than Coleman (check out Meditations, which was cathartic). But Coleman had established his playing style. Compare Coltrane perhaps to Schoenberg who started using Brahms and Wagner as springboards, but who evolved into atonal, then serial music. Now imagine Coleman or Cecil Taylor as being metaphors for Varese or Ruggles--two composers who chose a sound from the beginning, but would not change their approach significantly. They started at an extreme level and added references that deepened, but did not radically change their language. Now imagine an individual who can work with all of these idioms, and also function well in a traditional environment, and you have individuals like the late Eric Dolphy and... Reggie Workman (I know comparisons of this type are dicey at best, and are not meant to compare classical and jazz players in any way, except in terms of broad stylistic approaches).

Workman is an interesting figure in the history of the acoustic bass. He is, first of all, a consummate technician. I can recall visiting him in the Old Chapel at the University of Massachusetts, which was a charming old building which served as a music library and rehearsal space. He was practicing Bach pieces on the acoustic bass. So, he was grounded in many different musical forms and is always curious about new ones. His knowledge of the African-American music tradition is awe-inspiring. I can attest to that as a student in his class when, 30 years before Ken Burns' Jazz, he broke down the legacy of jazz for serious students in a college classroom, not only as a student in jazz history, but as a participant, having recorded with Art Blakey, Gigi Gryce, John Coltrane and Archie Shepp, among others. He not only had respect for Ellington and Armstrong, but also Coleman, Taylor and Sun Ra. Not to discount Wynton Marsalis' knowledge, but Workman should have been the creative consultant for Ken Burns' Jazz--at least the last fifty years of jazz history would have been treated with some respect, rather than the dismissive summary Burns documentary presented.

Workman, in 1974, already had a legacy under which he could have retired. A muscular bassist with a full, but gruff tone--more virtuosic than Jimmy Garrison, less extroverted than Cecil McBee, not as resonating as Charlie Haden, but very forceful and pushing--Workman ranges from funk to freedom with ease, a chameleon with a recognizable face.

Workman had started his musical studies by playing piano, then progressed toward the double bass later. His early friendships included trumpeter Lee Morgan, who he reported in an All About Jazz interview, had a huge record collection, and he went on to record as a member of groups led by Gigi Gryce, super drummer Roy Haynes, Wayne Shorter and Red Garland, finally hitting the point for which he has the most fame, replacing Steve Davis in John Coltrane's Quartet. Despite taking part in some landmark recordings (Coltrane's composition "India", reportedly influenced quite a few ‘60's rockers-Roger McGuinn of the Byrds reports that the group played that recording repeatedly in the months prior to recording "Eight Miles High," for one example), family obligations, mainly his father's illness and subsequent death, caused him to leave the quartet. There, he was replaced by Jimmy Garrison, in what was the best known incarnation of Coltrane's quartet, with McCoy Tyner on piano and Elvin Jones on drums.

After fulfilling his family responsibilities, Mr. Workman returned to the jazz world, and enjoyed a career that spanned working with such legends as Art Blakey (an incredibly underrated drummer and composer); Yusef Lateef, Pharoah Sanders, James Moody, Archie Shepp (he was on Shepp's classic Impulse recording, Four for Trane), David Murray, Thelonious Monk and many other players across the spectrum of creative black music. He has also played with legendary iconoclast and genius Cecil Taylor.

Mr. Workman also devoted a significant part of his life to teaching at the university level--many, many years at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, time served at Bennington College, the University of Michigan, and full associate professor at New York's New School for music. He has also been involved in music education in a community setting, helping to found the Collective Black Artists. He is also currently the co-director of the Montclair Academy and serves as founder of the Sculptured Sounds Music Festival, an artist-driven festival of futuristic music and concepts held every Sunday in February in New York.

While involved in academia, Professor Workman in the 1970's, 1980's and 1990's was performing with a wide variety of challenging performers, including Max Roach, Art Farmer, Mal Waldron, David Murray, Sam Rivers, and Andrew Hill, and also began leading his own group, the Reggie Workman Ensemble. He also started collaborating with pianist Marilyn Crispell that lasted into the 1990's and resulted in a reunion in 2000. Workman also worked (and is working) with Trio Three with Oliver Lake and Andrew Cyrille as well as Reggie Workman's Grooveship and Extravaganza.

The single most fascinating aspect of Workman's career is his ability to work with mainstream and avant artists. Even the more conservative performers with whom Workman has worked with (Waldron, king of the minimalist tension-building piano improvisation and Andrew Hill, one of the most innovative post-Monk composers and pianists, but whose compositions still show a recognizable swing and structure) show a fierce individuality and personal vision that elude many contemporary classicists. Workman has shown a willingness to play only with artists of uncompromising integrity--a rare quality, but one which a musician of Workman's range and technical skills can command.

Trio 3 (Oliver Lake- alto sax / Reggie Workman - bass / Andrew Cyrille -drums)

Mal Waldron quintet with Reggie Workman- Ed Blackwell

Professor Workman once made the comment that, as one travels along his or her path, in accord with Hindu philosophy, that as one moves further and further along the path, one has fewer and fewer associates. It seems that, contrary to the dictum, with time, the bassist's associations have expanded, not contracted, and he is reaching more people than ever. He was named a Living Legend by African-Amercian Historical and Cultural Museum in Philadelphia and is also a recipient of the Eubie Blake award and has been suggested as a 2014 recipient of the National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters award. Seems like the vitality, care and compassion, as well as his attention to his craft, are still in full focus, well after the nearly forty years after I first encountered this legend of music. His contributions to the music we sometimes call jazz have been legion, and his influence, as a performer, composer, leader, and educator, shall endure.

References:

http://www.artsjournal.com/jazzbeyondjazz/2012/12/my-suggestion-for-2014-nea-jazz-master-reggie-workman.html

https://jazztimes.com/departments/at-home/reggie-workman/

Car?

Reading?

FJ: Evidence just reissued Great Friends with Sunny Fortune and Billy Harper.

The opening set, consisting of mostly original pieces, included twin homages to Martin Luther King Jr. and John Coltrane. The first, described by Workman as "a martyr's hymn," movingly combined Joseph Jarman's somber yet lyrical flute, the poignancy of Workman's bowed bass and the bluesy-cum-spiritual punctuations of pianist Marilyn Crispell. The Coltrane tribute took the form of an emotionally varied suite featuring each of the musicians at length. Andrew Cyrille, surely one of the most passive-looking drummers around, stood out by translating Coltrane's energy and spirit into an extended and ceaselessly inventive solo.

Given the tenuous nature of jazz clubs in town, a word about the tavern seems in order. It's surprisingly roomy, well-lit and friendly. It offers good sound quality and a venturesome booking policy and deserves all the support it can muster.

It is indeed my pleasure to realize that this artist-driven initiative can happen because of the belief and support from our community of arts patrons and all of the wonderful artists and other participants who joined this effort with the spiritWe've chosen to dedicate this effort to the memory of the late Jimmy Vass (1937-2006) who devoted his life to the growth of aspiring musicians.

Reggie Workman, with an ensemble, performed all the music from a John Coltrane album. Credit Ruby Washington/The New York Times

Cerebral Sounds: Bass player Reggie Workman explores "Cerebral Caverns" on his new album. (Photo by Jopanne Dugan)

Cerebral Sounds: Bass player Reggie Workman explores "Cerebral Caverns" on his new album. (Photo by Jopanne Dugan)

https://jazztimes.com/departments/at-home/reggie-workman/

04/01/2005

by David R. Adler

Reggie Workman

Reggie Workman. Photo by Jimmy Katz

Reggie Workman smiles warmly when our JazzTimes contingent rolls up to his door on a quiet, residential block in Montclair, N.J. But Julia, his black-and-white Shih Tzu, simply can not contain her glee. Her ecstatic welcome dance lasts a good five minutes. Workman ventures a guess as to what’s going through the dog’s mind: “Real people! I don’t have to hang out with this boring guy all day!”

Boring? This hardly describes Workman. An unassuming master of the music, Workman, 67, a Philadelphia native, migrated to the New York area in 1958, and his achievements as a bassist, bandleader and educator have yet to stop piling up. He recorded and toured with John Coltrane’s classic quartet, shared the bandstand with Freddie Hubbard and Wayne Shorter as a member of Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, subbed for Ron Carter in the mid-’60s Miles Davis quintet and has appeared on some of the greatest jazz albums ever made.

Workman and his wife, the Slovenian choreographer Maya Milenovic, have made their home in Montclair since 1993, a year after the birth of their daughter, Ayana. (Workman’s grown daughter, Nioka, is an accomplished cellist.) Together, Workman and Milenovic are a pedagogical force-they codirect a local prekindergarten program, a jazz-and-dance summer institute in Slovenia and the Montclair Academy of Dance and Laboratory of Music, along with its performance arm, the North Star Navigators Youth Theater. In their living room there is a rail affixed to the far wall, a leftover from the days when the dance academy was home-based.

It’s no exaggeration to say that Workman’s life revolves around education. He is a full-time professor and curriculum coordinator at the New School University’s jazz and contemporary music program. “I’m concerned about working with the young students, to get them interested in passing the ball to the next generation,” he says, although collegiate jazz is only one facet of his teaching. He mentions Howard Gardner’s theory of “multiple intelligences,” and believes students of all ages are best served by a thorough intermingling of arts and academics. “We plant the seed with the little ones at the pre-K,” he says, and ideally, the process continues, through young adulthood and beyond. “It’s one community,” he adds, noting that the children of Billy Hart, Wallace Roney and Geri Allen and others have come under his tutelage.

Milenovic also helps out with Workman’s performance career. There are several ongoing projects: Ashanti’s Message, featuring the remarkable pianist Yayoi Ikawa; Statements, a group involving some of Workman’s Slovenian students; W.A.R.M., a fledgling supergroup with Pheeroan akLaff, Sam Rivers and Roscoe Mitchell; and a Coltrane Legacy band employing Charles Tolliver’s transcriptions for big band and choir. There is also Trio 3, Workman’s spellbinding collaboration with Oliver Lake and Andrew Cyrille. Juggling these groups and teaching full-time leaves room for little else, but this accords with Workman’s philosophy of life: “Find out what things you can handle, the things that are important to you, and concentrate on that, do that well.”

Workman is a health-conscious person who prefers not to dine out: “You don’t know what you’re getting.” Before moving to Montclair, he and the family lived in a Jersey City condo, in “an area where the military used to have all their factories, and they dumped radon into the ground, and people were dying from cancer. You couldn’t drink the water.” Montclair also offered better schools.

The move was just one instance of Workman going the extra mile for his family. He shaved his head some years ago, at Ayana’s urging. “She loves Michael Jordan,” Workman explains. “I made a deal with her: I will shave my head if you will stop being careless, and do the things you’re supposed to do. She did her part, so I did my part. Now she’s after me to get an earring, but I don’t think so.”

The Personal File

Computer?

“I am learning. I’m in touch with young musicians, and that’s their world. This has to be part of my world too, to stay in tune with the new energies. I just got Sibelius; I’m learning that program. I’ve got to get a bicycle and catch up!”

Car?

“A Ford Taurus wagon, which fits the bass travel case. I had to choose a car according to the size of that case. But I usually commute by bus to New York, because I can’t afford to park.”

Travel?

“I like the [Caribbean] islands, I like Brazil, I like Japan, I like Florence. I love the world. It just depends on what’s around you. The buck stops here-your favorite place has to be where you are, under any circumstances.”

Reading?

The shelves are overflowing with books, but Workman singles out Michael Levine’s Deep Cover (a critique of the drug war), Charles Mingus’ Beneath the Underdog, Valerie Wilmer’s As Serious As Your Life and Lucien Malson’s Histoire du Jazz et de la Musique Afro-Americaine.

Food?

“I haven’t eaten red meat since 1958, but I eat fish and fowl. My father was a chef, and I used to cook a lot when I was younger. I don’t do it as much anymore-as a matter of fact, I’m in the doghouse because I don’t cook as often as I could for the family. Where I need to find the time to cook is in front of the keyboard or on the bandstand.”

A Fireside Chat with Reggie Workman

by AAJ STAFF

April 16, 2003

AllAboutJazz

"I used to study the Hindu philosophy... one thing that it taught me was that when you reach beyond a certain point, you leave a lot of people by the wayside. You move away from a lot of people and your society becomes a lot smaller..”

—Reggie Workman

Why would someone leave the John Coltrane Quartet? That question still stigmatizes Workman forty years after his departure, overshadowing his impressive collaborations as a member of Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers (with Wayne Shorter and Lee Morgan), and with Yusef Lateef, Sam Rivers, Andrew Hill, Archie Shepp, and Freddie Hubbard. So I asked. The following is my conversation with Reggie Workman, a groundbreaking bassist unfairly labeled 'avant-garde' and the before mentioned Trane water he has carried for far too long, unedited and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

REGGIE WORKMAN: Because of environment. The environment probably prompted me to want to be a part what it was because music is a part of the environment that most of us grew up in. It was quite unlike it is today. There was a lot of live music, a lot of live venues for new music, a lot of great musicians who lived in the communities around Philadelphia, a lot of theaters, a lot of activity that would encourage a younger person to be a pert of the scene. I started as a very young person, eight or nine years old, studying piano and I think my parents recognized that. So that is the way I started as a young person. My parents probably recognized how music was a part of our community and put me in touch with some lessons and from there it grew. Now, that I look back on the situation, I realize how much the culture has to do with the evolution of a people. A lot of our institutions as a young person in the school systems and so forth didn't encourage too much cultural evolution, but that was a natural thing in our community. I think my parents recognized that and in developed from there. I stopped dealing with piano when I was about twelve years old, thirteen. The sports in the streets called me and so I got involved with that and left piano to grow into another area of life. I had a cousin, who recently passed, encouraged me. He used to stand me up by his bass and showed me how to play it and I liked that sound. Eventually, I went looking for it and so I started to play the bass in my final year of junior high school. They didn't have a bass, so I ended up playing wind instruments until a bass came, just before I graduated. Then from there, I moved over to high school, where I got an instrument and eventually got my own instrument and have been studying it ever since.

FJ: Give me your impression of Lee Morgan.

RW: Lee Morgan and I grew up together. We both grew up around Philadelphia and so we played a lot together around the scene. We knew one another. We knew the same people. He had a giant record collection, so we used to hang out a lot. He went to a music school in New York. We often crossed paths. He was a delightful person and tremendous talent.

FJ: Wayne Shorter.

RW: That happened during the time when Wayne was just growing into himself and I was in New York. A lot of musicians convened on the scene in New York from all over the world, Wayne coming from the New Jersey area. We often ended up on the bandstand together even before the Art Blakey days. Then as we grew, we all ended up in the band together. All the people who you heard in the classic Art Blakey ensembles often would see one another in New York over the years and during the years prior because of just what the scene was. There were places to work. There were jobs. There were jam sessions. There were reasons to be crossing one another's path.

FJ: And Lee Morgan and Wayne Shorter in the frontline along with you and Blakey in the rhythm section is why that band is so highly thought of.

RW: Of course, everyone was significant as they always have been. As you grow, you get an idea of who's who. They are not just significant because they have been embraced by the system. They were significant because they had something to offer when they were very young musicians and they always have had that gift throughout their career.

FJ: And the same holds true of your association with John Coltrane?

RW: Our association wasn't brief. John Coltrane spent a lot of time in Philadelphia, where I am from and therefore, we saw one another long before I joined the group. Even through the late Sixties, we spent a lot of time traveling and making music together. He was developing and I was developing and our paths crossed for a while.

FJ: You must have been asked this numerously through the years, but with such a kinship, why did you leave the band?

RW: I'm a bit tired of those questions. I left the band because my father was dying and I had to leave New York and go back home and take care of my family, number one. Number two, John and the rest of the band was growing very fast and John had decided that he wanted to try another voice in his bass chair. He had been listening to Ornette Coleman, who had Jimmy Garrison in the group and Coleman suggested he try Jimmy and he did. That was a great union. Of course, Jimmy was very compatible with everybody in the band.

FJ: So no regrets?

RW: I think we have an idea of what is in store for us in life and what you can achieve and what you want to do. So be it. It is like any other profession.

FJ: With convincing albums Summit Conference, Cerebral Caverns, and Altered Spaces, why haven't you recorded more?

RW: Looking back on that situation, I realized that while a lot of people were spending time developing and honing their skills for composing and developing a band, I was busy helping somebody else with their program as being a supporting artist. You can start down that path and before you know it, and this is a good thing to say to the younger musicians, you will find yourself moving down that path and there is nobody that pulls your coat, you haven't developed what you need developed as a bandleader, as a composer, as a person who is shaping the way the music is going as far as what the industry considers significant. That is what I see happened in my life. Later on in life when I realized that, I decided that it was time for me to change, but of course, when I was prepared to make that change, I had already been through quite a few groups, quite a number of groups, so my ideas were a little different from the average person who was stepping into that arena and that was not always sellable in regards to the industry's whims. I realized that as you grow your society becomes smaller so you don't expect to be among the stars in the industry when you want to do something different. That is what happens to the person who decides to stick to their guns and do that. During those days, it was a little bit different than it is now. The message was different. If you are a follower of the music, you will hear those people who made different moves and who evolved. If you are an intelligent person, when you listen to the growth of each one of those musicians, you will understand where their mind is because everything is apparent.

FJ: Evidence just reissued Great Friends with Sunny Fortune and Billy Harper.

RW: Most of the music that you listen to in this world of music never grows old. The more you listen to it, the more you hear in it because of just what is real in the world. When we did that product, we were taking a group to Europe to tour. I have a sister who is married to a Frenchman and she was working for a company there, Black & Blue, the original label that we produced the record on because of her wanted our group to record for her and we did. It came out, but it was only for Europe. Evidence became interested in it and put it out here. It is not something that will grow old because all the musicians are fresh and everybody is really playing good on it. It is just too bad that it was twenty-something years later before people get a chance to hear what was on your mind and they expect you to still be there. Not so. Everybody has moved onto their own ideas and their own thoughts and their own desires. Consequently, because of the amount of time that it takes for something to come out, that is what happens. Bands fall apart in the interim. That was a lot like when we were working with John. Bob Theile let John put in the contract that if he records for him, the record must come out within 'X' amount of months so that people will not come to you and ask you to play something that is old hat to you. Your mind has moved onto other things in five minutes, let alone five months. When I first joined John's group, people would ask him to play 'Favorite Things' and he didn't want to think about that. He did it because he was that kind of person who could do anything that he wanted to do and make it fresh, but he realized very quickly that his mind and his soul was moving so fast and the message was so futuristic that he didn't want to paint himself into a corner, so he had that put into the contract.

FJ: And the future?

RW: I have a group. I lost the saxophonist who was prime in the group. He had some problems and he fell off the scene. The groups that I have now, they vary because people have different things and I am not consistent enough in the business to keep it together. I am trying to pass my knowledge onto younger musicians and that takes a lot of time and energy along with living life and things that you have to do to keep up with this world. I am hearing certain things. I have certain ideas that I would like to do as far as the music is concerned, but I don't want to just get out there and do it. I want to spend some time with it before we present it. Spending time with it means finding people who have the time to spend with you and that is not easy to do. When you are away from the music, you are not at your best physical state like Tyson couldn't win after being in the joint for a few years. So you are not in the best physical state as far as your performance is concerned, so you become a little reluctant to just jump out there without some preparation. That is where I am right now. Between having had the time when I was very active in the music world and living through a time now, when I am not as active, I would like to be, in my mind, I would like to do several large projects which I have not done many of through my career. I am working on a opera right now. That is the direction that I want to go in. I would like not to spend a lot of energy and time with being a supporting artists for other person's projects because I have learned over the years that that doesn't work. I used to study the Hindu philosophy a lot and one thing that it taught me was that when you reach beyond a certain point, you leave a lot of people by the wayside. You move away from a lot of people and your society becomes a lot smaller according to which direction you are moving in. If you understand that reality, then you understand how to accept the fact that your society is smaller and therefore, the reward is smaller. I have seen some really great rewards. First of all, Fred, I am still on the planet. A lot of my associates are not. I have a beautiful family. I think that is a great reward. It comes back in different ways depending on where you values are, you will realize whether it is a reward or whether it is a detriment.

FJ: So the record opportunities have been there.

RW: Yes, I have, but I have just been really too busy with other things to really concentrate on it. It is about time for me to do that again. I just have not been able to do that. You can see my track record on the net, so you know what I have done. Those two pieces had a significance in that there was a musician who gave me the latitude to move the way that I moved and he liked the people that I chose. I say he, and that was Ralph Simon, who was the A&R man at Postcard at the time. I am busy with so many other things that I am not able to just jump out and make a document. As a matter of fact, Fred, I don't want to make a document under the circumstances as they are now. I would rather not document what is happening at this particular time. I would rather prepare something that is more in tune with where my head is. For example, we did the Summit Conference album. That was an idea that I had as far as presenting myself and get together with the people that are responsible for the cornerstones of this music. The other product was a sequel to that and the next thing would be a sequel to the second. It won't be a record just because someone says, 'Let's do a record.' I'm not interested in that. I am interested in doing something significant as far as my desire and my ideals are concerned. Otherwise, I would rather do nothing at all.

FJ: Compromise isn't in your nature.

RW: There may be only a few people who appreciate it, but I would rather be in the company of those few than the many who don't know what they are listening to or what you are trying to say.

Website: www.reggieworkman.co

There was little time to rehearse the ensemble, so no one -- not even Coltrane -- knew what to expect. But what was clear was that Coltrane was taking his music into uncharted territory. Joining him were pianist McCoy Tyner, bassists Reggie Workman and Paul Chambers, drummer Elvin Jones and, most conspicuously, a brass menagerie consisting of French horns, trumpets, trombones, euphoniums and a tuba.

Listening to the Drum Choir, Workman heard some of the rhythmic concepts Coltrane would later use when he paired two bassists on his composition "Africa," the album's centerpiece. "We were creating the same conversations as the Drum Choir, except bassists can deal with intonation and rhythm," Workman says. "I wish we had more time to do it, because we were just beginning to explore it when things kind of fell apart and I had to leave."

Although he has no plans to record his choral adaptation of "Africa/Brass," Workman would like to present the concert around the country, beyond the scheduled stops in Richmond, Washington and Philadelphia. The prospects, though, aren't good. "These projects develop over a period of time, and they've got to be funded just like orchestras," he says. "People have to keep working on these things, and that takes money."

REGGIE WORKMAN'S RHYTHMS OF HISTORY

by Mike Joyce

June 7, 1998

The Washington Post

In the spring of 1961, saxophonist John Coltrane, a former Miles Davis sideman turned bandleader, recorded his first album for the Impulse label. The studio that day was crowded with 18 musicians and a peculiar assortment of instruments. It was obvious to everyone present that this was not going to be your average jazz recording session.

There was little time to rehearse the ensemble, so no one -- not even Coltrane -- knew what to expect. But what was clear was that Coltrane was taking his music into uncharted territory. Joining him were pianist McCoy Tyner, bassists Reggie Workman and Paul Chambers, drummer Elvin Jones and, most conspicuously, a brass menagerie consisting of French horns, trumpets, trombones, euphoniums and a tuba.

Ultimately it would take two sessions to record "Africa/Brass" -- an album that would soon help propel the rapid and radical changes in jazz during the next decade. Driven by African polyrhythms, informed by a heightened cultural and spiritual awareness, and burnished by dark-hued brass, the music marked a pivotal point in Coltrane's now fabled career. Tonight at All Souls Church in Northwest Washington, Workman, now a bandleader himself, will pay homage to his former colleague with newly arranged music from "Africa/Brass."This time, however, the ensemble will be even larger. For this performance, presented by District Curators, a 17-piece orchestra will be augmented by a full gospel choir. "As I listen to Africa/Brass' I hear the human voice," Workman says. "I always wanted to do something with a choir, and I think it'll help convey the feeling and importance of the music John created."

Now 61, Workman can look back on a career packed with memorable collaborations. At one time or another, Miles Davis, Art Blakey, Thelonious Monk, Max Roach, Freddie Hubbard, Mal Waldron, Wayne Shorter, David Murray, Pharoah Sanders and Stanley Cowell have all benefited from what Coltrane himself once described as Workman's "rich imagination." Yet even now, despite such illustrious associations and the international acclaim his own ensembles have received, many jazz fans best remember Workman for his year-plus stint with Coltrane -- an association that ended abruptly when the bassist's father took ill and the draft board came calling.

Workman recalls that "Africa/Brass" came together quickly, "in a matter of a few weeks, maybe days." Saxophonist Eric Dolphy transcribed McCoy Tyner's piano voicings for most of the orchestrations, Romulus Franceschini arranged composer Calvin Massey's piece "The Damned Don't Cry," and "before we knew it, we were asked to come to the studio and John called in all of the brass."

Workman shared Coltrane's interest in African rhythmic concepts and was certain they'd play a prominent role on the saxophonist's recordings sooner or later. Both musicians befriended Nigerian percussion master Babatunde Olatunji and had heard his African Drum Choir perform.

"During that time John was doing a lot of concerts with Olatunji at the Olatunji Cultural Center in Harlem," Workman says. "He read a lot, he was listening a lot, he was very interested. I was very interested too. During the early '60s, people were getting concerned with the ethnic relationships in music. We all were."

Listening to the Drum Choir, Workman heard some of the rhythmic concepts Coltrane would later use when he paired two bassists on his composition "Africa," the album's centerpiece. "We were creating the same conversations as the Drum Choir, except bassists can deal with intonation and rhythm," Workman says. "I wish we had more time to do it, because we were just beginning to explore it when things kind of fell apart and I had to leave."

Coltrane, however, continued to draw on African influences when bassist Jimmy Garrison succeeded Workman in the quartet. In his authoritative new biography, "John Coltrane: His Life and Music," jazz scholar Lewis Porter sums up the effect: "The growing rhythmic complexity of his music, the adaptation of African rhythms, and {Coltrane's} encouragement of Elvin Jones's polyrhythms, led by 1965 to the elimination of strict time-keeping in his groups. In doing so, Coltrane helped create a new rhythmic basis in jazz. . . . And when {he} joined the movement among black Americans to look to the music of mother Africa for inspiration, he gave it a tremendous lift."

Thirty-seven years after "Africa/Brass" was recorded and 31 years after Coltrane's death, the music still holds revelations for Workman. "Song of the Underground Railroad," he notes, "is more of a vehicle for improvisation, but it's making a particular statement about the liberation of a people. It's still an important statement to make, speaking about Harriet Tubman and the spirit of a people who wanted a better way of life."

Reviving "Africa/Brass" presented Workman with numerous challenges. "There are five French horns on the recording, which we didn't know until we started listening closely to some of the tapes," he says. "I mean, I knew there were French horns -- there were so many brass people in the studio I didn't know them all -- but that was a long time ago. So when we were putting this new project together, we thought, how the hell can we afford five French horns? -- we can't."

A master of improvisation both onstage and off, Workman began to tinker with the "Africa/Brass" instrumentation, eventually recruiting a broad variety of musicians who he believes are versatile enough to do the music justice. The lineup for this evening's concert includes French horn players Vincent Chancey and Tom Varner, trumpeter Jimmy Owens, trombonist Julian Priester, saxophonist John Purcell, tuba player Aaron Johnson, pianist John Hicks, harpist Elizabeth Panzer, drummer Ronnie Burrage and vocal narrator Dean Bowman.

Coltrane's son, saxophonist Ravi Coltrane, was also scheduled to perform but had to bow out due to other commitments. He's been replaced by 19-year-old reedman Marcus Strickland, one of Workman's most promising students at the New School for Social Research in Manhattan. Yet the offspring of three prominent jazz musicians will perform: saxophonist Zane Massey, bassist Matthew Garrison, and Workman's own daughter, cellist Nioka Workman.

"I wanted to be a part of putting these kids on the map," Workman says. I want this project to help the young generation of people who have been touched by the legacy of John Coltrane."

The first half of the concert will be devoted to new music performed by Workman's current band. "John was the kind of artist who would be very disappointed if we were just going to revisit his music and not deal with where we are now," he says.

Although he has no plans to record his choral adaptation of "Africa/Brass," Workman would like to present the concert around the country, beyond the scheduled stops in Richmond, Washington and Philadelphia. The prospects, though, aren't good. "These projects develop over a period of time, and they've got to be funded just like orchestras," he says. "People have to keep working on these things, and that takes money."

In the meantime, Workman will not be idle. He'll continue to compose and record music with his own band, tend to future crops of jazz musicians, and keep one of the most important lessons he learned from Coltrane in mind: "Evolve, not revolve." CAPTION: Bassist Reggie Workman rehearses with jazz musicians at New York's New School for Social Research. CAPTION: John Coltrane filled the studio with musicians for "Africa/Brass."

REGGIE WORKMAN ENSEMBLE, COHESIVE AND DISTINCTIVE JAZZ

by Mike Joyce

January 19, 1987

The Washington Post

The Reggie Workman Ensemble, an all-star jazz quartet, is the sort of band that's easily appreciated, both as a cohesive unit and as four distinctive artists who happen to be sharing the stage. At Takoma Station Tavern last night, there were times when the band jelled as one, and times when each of the musicians clearly inspired the others.

The opening set, consisting of mostly original pieces, included twin homages to Martin Luther King Jr. and John Coltrane. The first, described by Workman as "a martyr's hymn," movingly combined Joseph Jarman's somber yet lyrical flute, the poignancy of Workman's bowed bass and the bluesy-cum-spiritual punctuations of pianist Marilyn Crispell. The Coltrane tribute took the form of an emotionally varied suite featuring each of the musicians at length. Andrew Cyrille, surely one of the most passive-looking drummers around, stood out by translating Coltrane's energy and spirit into an extended and ceaselessly inventive solo.

Given the tenuous nature of jazz clubs in town, a word about the tavern seems in order. It's surprisingly roomy, well-lit and friendly. It offers good sound quality and a venturesome booking policy and deserves all the support it can muster.

Reggie Workman

Legendary Bassist • Composer • Ardent Advocate of Arts Education • Founder/Producer

Biography

A legendary bassist, Reggie Workman is highly regarded as a bass player’s bass player. Workman’s playing styles cover the range of modern music from Bop to Post-Bop, to Futuristic, incorporating a contemporary approach to jazz improvisation and composition. His uncanny ability to equally understand and share musical ideas with such diverse musicians as Art Blakey on one side and Cecil Taylor on the other is stunning. As a result, Workman has invented his own language of sound and expression as a performer and composer.

An ardent advocate of arts education, Workman is a Professor and Coordinator of Curriculum at the New School for Jazz and Contemporary Studies, an institution recognized around the world as one of the greatest schools for jazz education:

"With a faculty of accomplished professionals, it is safe to say that no program is a better example of students (new to the Jazz experience) being able to learn from the source."

Reggie Workman has always been active in music outreach and education to the community. He co-founded the historic Collective Black Artists (CBA), and was Music Director of the famous New Muse Community Center (Brooklyn, NY). He is presently Co-Director of The Montclair Academy of Dance & Laboratory of Music Studio and Founder/Producer of the Sculptured Sounds Music Festival, an artist-driven festival of futuristic music and concepts.

Workman has performed and recorded with giants of jazz including John Coltrane, Art Blakely, Eric Dolphy, Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, Cecil Taylor, Mal Waldron, Archie Shepp, Sam Rivers, Trio 3 and Great Friends as well as emerging jazz legends such Jason Moran. He established himself as a bandleader and composer in the 70's when he first presented his stellar group, Top Shelf. Since then, Workman has continued developing new music arts curriculums and workshops and presenting various Reggie Workman ensembles under the umbrella of his production company, Sculptured Sounds, in the United States and internationally.

Other Reggie Workman "Happenings" in January, 2007

The music never stops for this legendary musician. Catch him this month at:

- Jan. 23rd — George Lewis (electronics & trombone) with Reggie Workman (contrabass)

- The Stone, Ave. C at 2nd St., NYC, 8pm, $10

- Jan. 25th — Harlem Speaks: Bassist Reggie Workman presented by the Jazz Museum in Harlem

- 104 E. 126th St. (between Park & Lex.), NYC, 6:30-8:30pm, free

- For reservations: (212) 348-8300

Comments from Festival Producer, Reggie Workman:

The Sculptured Sounds Music Festival is an exciting four-concert series of performances showcasing the many sides of Futuristic Music and concepts. Under the umbrella of Sculptured Sounds, I've "sculpted" an eclectic line-up of artists, some in unique configurations that, heretofore, I only imagined combining. The festivities started off with the well-received "Preview Concert," December 10th, 2006 with subsequent weekly concerts to be held every Sunday in February 2007 at Saint Peter's Church. As connoisseurs of great music and innovative art, you'll want to be present for each one of these memorable performances.

Each week consists of a demonstration/lecture, opening act and a headlining act(s). The opening and featured act(s) perform in the Sanctuary while just outside in "The Living Room," you'll find a multi-disciplinary experience of music-related demonstrations/lectures, artwork by musicians (The Preview Concert featured the artwork of Musician/Artists Oliver Lake & Dick Griffin and an Art/Sound Improvisationalist, Umberto Grati), listening stations and vending opportunities for participating artists. The host for the concerts is ABC's "Like It Is" host, Gill Noble.

This is a project whose time is NOW. I realized cognized the dearth of performing opportunities for such talented artists and, as of this writing, the full series of concerts will employ over 80 artists (see Schedule). In less than two weeks of contacting the selected artists, over 90% had confirmed. Besides Oliver Lake and Dick Griffin, confirmed artists include such noted artists as Stanley Cowell, Amiri Baraka, Jason Hwang, Billy Hart, Charles Gayle and Sonny Fortune.

It is indeed my pleasure to realize that this artist-driven initiative can happen because of the belief and support from our community of arts patrons and all of the wonderful artists and other participants who joined this effort with the spiritWe've chosen to dedicate this effort to the memory of the late Jimmy Vass (1937-2006) who devoted his life to the growth of aspiring musicians.

All this translates to the presentation of The Sculptured Sounds Music Festival, and, most importantly, that unique creative element which has been sorely missed from the roster of more mainstream productions.

Thank you in advance for your support. Looking forward to seeing you at the concerts.

All the best,

Reggie Workman

All Events Take Place at Saint Peter's Church, 619 Lexington Avenue at East 54th Street.

For more info and reservations, please call (212) 642-5277

Reggie Workman, Founder/Producer and Francina Connors, Co-Founder/Production Coordinator

Bassist Reggie Workman Reminiscences on the Philadelphia Jazz Scene, 1988.

interview conducted by Steve Rowland, April, 1998. unpublished. © 2000 Steve Rowland & CultureWorks, Ltd.

The first significant music I remember hearing was music on the jukebox at my father's restaurant at 54th and Haverford. Some of you here may know where that is, across the street from the Oasis. We had, the family had a restaurant there that had all of the current music. That meant all the rhythm and blues, and all of the Billy Eckstine, Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday, Dinah Washington, Bessie Smith and all of the, Wynonie Harris and you name it. Everything that today is considered significant and historic was on that jukebox as something that people that came in there and eat their lunch and dinner heard every day. So that was a very significant thing and then when we were midgets sitting around the floor together at home there were all kinds of radio things that happened on that big old classic radio that we listened to. All kinds of radio tracks and things that stuck in our minds. For example one thing that sticks out when I say that is like Nat King Cole came on every Saturday afternoon or morning with his trio. The reason it sticks out is because I just did a kind of thing with a trio, two students from the school, Nick Rolfe and Jazz Sawyer. We did like at the Persian type of trio hit and we began to talk about Ahmad Jamal and how significant that was and prior to Ahmad Jamal from Chicago [note, Jamal was actually from Pittsburgh, but had moved to Chicago] was Nat King Cole from Evanston and his family. There's that family thing again. And that music was every Saturday.

And I remember being very small, hardly walking and listening to that. Very, very, very, very important music. And Thelonious Monk's "Ask Me Now"... when I first heard Monk play that, immediately it came right to me because of the whole family scene, the whole situation that was happening then and the whole social, political situation that happened around the theme of that song and the commercials and the radio, the way the story was done every week and your families looked forward to hearing that. There was no television. We related to one another as people and as family and we listened and we thought and we heard vis-à-vis now you have this optical image that's kind of shaping your thoughts and all that relating to the first music that I heard. And that's just the tip of the iceberg.

SR: Tell me when you were born and how many brothers and sisters?

RW: I'm from a big family. There were 15 of us and I was born in Philadelphia in '37 and I think by the time I was born we had already moved to West Philadelphia and we lived around Philadelphia. My father was from North Carolina, Charlottesville, North Carolina and my mother was from somewhere in Maryland and she was raised in an orphanage which as I look back on the situation, I say "Mom, maybe that's why you had so many kids because you were an orphan, and you were an only child" and the significance of the family may, also the fact that she didn't believe in abortion as people do today and don't want to have a child, they just go and have an abortion. But my mother didn't believe in that...

So before I left Philadelphia, we were living in Brickyard, which is Germantown. Why they call it the Brickyard, because it was an industrial city and there were textile industries, factories and things that were in the neighborhood and they begin to tear those factories down to make room for houses and the bricks were from demolishing the factories were still there and they would have these gang fights and they would always be throwing bricks at one another. The place was like a pile of rubble, a heap of bricks that was around for a whole area where people actually had to live. So that's what was called. That was 1500 North, it could be called Germantown too. But for those of you who lived in Philadelphia in that area understand what that meant.

I believe during '49 when my brother was coming out of school and going to the Army, I was moving through junior high school, Roosevelt Junior High School and Germantown High School along with a lot of people who you probably know like Archie Shepp who moved up from Miami and moved into the neighborhood. Donald Lundee who was a politician, who recently had some kind of a disappearance, strange disappearance here in Philadelphia, who was playing saxophone. Nearby Bill Cosby who lived down the street, across the Eastside, who was on the sports teams while Archie and I were on the musical teams. Who else? The Adderly Brothers who were on the sports teams. Jimmy McGriff and his younger brother and family. There were a lot of families, again, I want to underline these things that have been brought to herefore, a lot of families musical families and people in the community who went ahead and did things. And I believe that all that you see from the names that I mentioned, all the stories that Bill Cosby comes up with and all the animated cartoons, when I look at them I see the people who he's talking about, Fat Albert...

And when you listen to all this music and I hope that you do listen to this music, you can see what the community was like and what people are talking about when they come up with their art, which is again, a reflection, a direct reflection of what we went through as we grew here in Philadelphia, grew through these things. You can somehow have an idea of what was going on, what the city was like... That's a reflection of where I was during that time.

http://www.nytimes.com/1987/05/17/arts/top-bassists-are-the-bottom-line-in-jazz-ensembles.html?mcubz=3

Top Bassists Are the Bottom Line in Jazz Ensembles

by Robert Palmer

May 17, 1987

New York Times

Playing the bass in your own improvising ensemble can put you in the driver's seat, just as a certain rent-a-car agency claims to do. Of course, not every bassist wants to drive or is capable of handling a careering vehicle. Not every band wants to be driven, by the bassist or by anyone else. But the bass has special capabilities, and its role in the jazz ensemble has developed in a special manner. Bass provides the bottom, and the pulse. In freer musical situations, the bass probes and prods, working in tandem with the drummer's rhythmic embroidery while feeding harmonic and melodic material to the players of chordal and melody instruments. Only the bass fulfills this triple-threat, rhythmic-melodic-harmonic function. A bassist, especially one who is a composer and bandleader as well, can simultaneously ground and guide a performance of improvisational music as it unfolds.

This is a job that requires, in addition to virtuosity and inventiveness, an uncompromised commitment to the music, an immersion in its currents. Composing, improvising, playing and listening become aspects of the whole. Charles Mingus was the master of this approach. His most powerful recordings, which subordinated themes and individual players to the music's own intense imperatives, have given subsequent bassist-composer-bandleaders a lot to live up to. But while there may not be more than one way to drive a car, there's more than one way for a bass player to pilot a band.

Reggie Workman has been one of the music's strongest bassists since he played with John Coltrane in the early 60's. He has a dark, robust sound. When he is plucking low notes, his fingers sound strong enough to shear steel; when he is soloing, he executes each note with an intensity of focus that can be almost frightening. No matter how fast he is playing, each note has a rich, deep center, and his intonation is impeccable. He has never been one of those bassists who play all over the instrument, keeping up a running dialogue with every other player at all times. The grounding function of the bassist is an important part of the tradition for him; he plays not for himself, but for the band.

So it isn't surprising that ''Synthesis'' by the Reggie Workman Ensemble (Leo LP LR 131, available from New Music Distribution Service, 500 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10012) is very much a group effort. The group is an all-star unit in that the reedman Oliver Lake, the pianist Marilyn Crispell and the drummer Andrew Cyrille are all bandleaders themselves. But they don't play like all-stars here, they play like a unit.

The compositions are Mr. Workman's; the music is very free structurally, with a soaring spirit and incantatory qualities that link it to some of the better small-band sessions from the early days of the mid-60's ESP label. But while he leaves plenty of room for each player, Mr. Workman deploys his forces ingeniously. He uses his bow to create deep, droning textures, blending his harmonics with the overtones of Miss Crispell's piano. On ''Ogun's Ardor,'' he articulates cleanly at the opposite end of his instrument's range, voicing a bass melody above the range of Mr. Lake's flute. This is stunning music, with a deeply felt intensity and a purity of intent that haven't been finding their way onto jazz records as often as one would like.

Art Davis sometimes played alongside Mr. Workman when John Coltrane used two bassists. On ''Life'' (Soul Note LP SN 1143, distributed by Polygram Special Imports), he leads a quartet featuring another former Coltrane associate, the saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, plus two of Mr. Sanders's frequent associates, the pianist John Hicks and the drummer Idris Mohammed. This is more a democratic combo recording than an ensemble statement. Mr. Davis, who is one of the music's outstanding technicians and a fresh, adventurous soloist, has provided a modal tune, a blues, and a modest suite that serve primarily as springboards for improvising. He has effectively focused his players, especially Mr. Sanders, who improvises with more concentration here than on many of his own recent recordings. It would be interesting to hear Mr. Davis in a more developed group context. He certainly has the capability, and despite its generally high level of musicianship, ''Life'' isn't as distinctive as it might be.

Records on the West German Enja label have been taking their time getting to the United States. ''Split Image'' (Enja 4086, LP) the bassist Mark Helias's first album as a leader, appeared here relatively recently, and it's almost three years old. Nevertheless, it's an impressive debut. Mr. Helias put together a recording quintet featuring musicians he had worked with extensively. Despite the differences in age and background, the tenor saxophonist Dewey Redman blended effectively with the alto saxophonist Tim Berne and the trumpeter Herb Robertson, constituting a bright, brittle, mobile front line, prodded from underneath by Mr. Helias's tight, fastidious bass and Gerry Hemingway's drums. The bassist's compositions are a varied lot, and they use the horns resourcefully, for harmonized backgrounds, counterpoint and heterophony as well as solos. Mr. Redman's carefully inquisitive solo on ''Le Tango'' is particularly successful; Mr. Helias isn't an aggressive bassist, but he gets the most out of his players.

Bill Laswell's successes as a record producer (with Herbie Hancock, Mick Jagger and others) have tended to overshadow his accomplishments as a musician. But he is one of the most innovative improvisers on the electric bass, and on ''Low Life,'' his new album of duets with the bass saxophonist Peter Brotzmann (Celluloid LP CELL 5016), he combines his instrumental and studio expertise in a spectacular fashion, using the recording process to expand on the jazz bassist's grounding-and-guiding function.

Even the ''compositions'' on ''Low Life'' have been realized through the medium of the recording studio; they are basically improvisations that have been extended with the overdubbing of additional basses and saxophones, the overdubs emphasizing certain melodic and rhythmic ideas, effectively transforming them into themes. Mr. Laswell uses various tonal modifiers and unconventional playing techniques to make his electric bass sustain drones and slide around between the notes like an acoustic bass. He creates dense layers of texture, reverberating deeply and blending with Mr. Brotzmann's sinewy bass saxophone.

This isn't a perfect record by any means. Even with all the technological help, the sound becomes somewhat confining over two sides of music, and the use of the studio to structure improvisations into compositions, while fascinating, would not have been compromised by the inclusion of more structured material. Nevertheless, for what it says and for what it suggests, ''Low Life'' is a striking updating of the bassist-composer-bandleader tradition, and undoubtedly a harbinger of sounds to come.

http://www.nytimes.com/1996/08/02/arts/a-bassist-who-jostles-traditional-structures.html

Arts | Jazz Review

A Bassist Who Jostles Traditional Structures

by Ben Ratliff

August 2, 1996

New York Times

The bassist Reggie Workman turns what swing band leaders used to call ''vamping till ready'' into a process of intimate communion. His deep, resounding ostinatos energize his musicians at the beginning of a piece; when the band hits solo territory, he's well inside the music, staying tight within the pitch areas of the soloists, intoning notes with a purposeful calm as if rubbing oil into wood.

He likes his bands loose and adventurous, and as a composer he's a curious mixture of exacting and laissez-faire. Much of the music played during Tuesday's late set at Sweet Basil was fresh, and Mr. Workman's quintet sight-read its way through the complexities. On the other hand, the leader gave his clarinetist and saxophonist, Marty Ehrlich, enough free room to demonstrate, as Mr. Ehrlich often does, the logical links between Ellingtonian polish and hollering free jazz.

By contrast, Anthony Davis's piano improvisations had a neat, calligraphic aspect. On an untitled, medium-tempo ballad, Mr. Davis waited until late in John Purcell's solo on saxello (a variant of the soprano saxophone), then sprang in with a muscled, rolling bass chord followed by brisk right-hand patterns. At first it seemed an eccentric kind of accompaniment, but soon Mr. Purcell subsided and Mr. Davis spelled him with his own fully formed improvisation.

Such a piece, with its curiously overlapped components, was typical of Mr. Workman; like Charles Mingus, another bass player given to composing, he artfully jostles jazz's accepted structures with his writing and arrangements.

The band, which will perform through Sunday night at the club (88 Seventh Avenue South, above Bleecker Street, Greenwich Village), had some of the usual first-night problems with new material. But Mr. Workman was always mesmerizing, with his thick, unbroken bass sound and his language of forceful exhortations.

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/31/arts/music/reggie-workman-and-eric-reed-at-rose-theater-review.html?mcubz=3

Music | Music Review

Remembering Sounds That Coltrane Built

by Ben Ratliff

October 30, 2011

In remaking the music from John Coltrane’s 1961 record “Africa/Brass,” as Reggie Workman did on Friday at Rose Theater, the first step is filling its dimensions. It’s not just that you have to fill it with loudness, though you do: the album has a huge cumulative sound. You have to fill it with people, presence and purpose, and you have to justify its repetitiveness. You have to honor pieces of music that seem to want to go on forever.

At that point Coltrane was strengthening new music with old ideas. He was absorbing source material from West African rhythm and black American spirituals; he was beginning to explore drones and modal harmony, which could serve as the background for many instruments soloing pretty freely for long stretches. His drummer, Elvin Jones, played strong polyrhythms in medium tempos, and the record is full of low and mellow frequencies. Aside from Coltrane’s quartet itself there’s a brass section with tubas and euphoniums, and on the piece called “Africa” a second bassist joins the core band. Implicitly and powerfully it suggests nature and perseverance. It’s built to be here after you’re gone.

Reggie Workman, with an ensemble, performed all the music from a John Coltrane album. Credit Ruby Washington/The New York Times

Mr. Workman, now 74, was the principal bassist on the original recording of “Africa/Brass,” and he performed all the music from the album with his African-American Legacy Project, a bigger ensemble: a jazz rhythm section, a brass orchestra with saxophones and a 17-member choir.

It was part of a concert, repeated on Saturday, which commemorated the 50th anniversary of Impulse Records, whose history amounts to much more than Coltrane but will always be associated with him. (“Africa/Brass” was his first album for the label, and he recorded for Impulse until his death in 1967.) Mr. Workman was the evening’s only representative of the label’s glory years; the pianist Eric Reed, who opened the concert, represented its revival in the 1990s.

The Coltrane music had been transcribed from recordings by the trumpeter and composer Charles Tolliver; Cecil Bridgewater conducted the musicians. And the choir sang melodies that lay in some part of the dense original work, their words based on the titles and the ideas therein, their voices arranged into simple harmonies. (“Africa” was the summit of the performance, with the voices repeating the words where the flute and piccolo came into the original music.) The singers did just what they should have done: make a grand thing grander.

Eric Reed played covers of his own at a concert Friday at the Rose Theater. Credit: Ruby Washington/The New York Times

Two bassists — Mr. Workman alongside Lonnie Plaxico — played not only for “Africa” but also throughout, over Ulysses Owens and Neil Clarke’s churning percussion. That’s a great idea, and you’d think the interplay between the basses might be what you went home remembering, but not necessarily. They played what the music asked of them, to frame and steady it without flash.

Much more of the concert’s psychic space was given to a long duet between two musicians (Stafford Hunter and Aaron Johnson) playing conch shells, which are halfway to brass instruments anyway, and it felt appropriate for the scope and feel of the piece: they are ancient, oceanic, natural. The conch-shell duet and a dramatic recitation of Oscar Brown Jr.’s poem “Forty Acres and a Mule” by Ira Hawkins were the only two places in the concert that came close to an expression of ego. The overall sense of confident self-effacement, the group as one entity and the music speaking for itself, felt true to Coltrane.

Mr. Reed, the pianist, is a completely different presence: chatty, speedy, funny, casual, specific. With his group, Surge, he played covers of his own Impulse hit parade — a gorgeous, mellow, glowing version of Oliver Nelson’s “Stolen Moments”; Ahmad Jamal’s “The Awakening”; his own “Pursuit of Peace.” (He’d set up his band as Mr. Jamal does, the piano at stage left, Mr. Reed looking away from the band. The bass was near his left ear, and the drums were behind him.)

He also played a scarily beautiful set of Coltrane ballad duets with the singer Andy Bey, a bass-baritone, and somehow Mr. Reed responsibly condensed Coltrane’s suite “A Love Supreme,” shortening and speeding it up but still leaving improvising room to his saxophonists, Stacy Dillard and Seamus Blake, and his drummer, Willie Jones III. It was an ambitious proposal, all that music, and he brought it home before intermission. That’s good bandleading.

Keeping It New

Bassist Reggie Workman maintains the spirit of avant-garde jazz

by Nicky Baxter

February 11, 1995

Metroactive

When the New Black Music, as avant-garde jazz was dubbed by poet/critic Amiri Baraka, hit in the early '60s, few knew what to make of it. Established concepts such as time, meter, rhythm, melody and harmony were reconstructed or obliterated altogether in order to fashion a music that was more emotionally cathartic and intellectually challenging.

But outside of a tiny circle of critics who viewed the revolutionary sounds as a respite from bebop's increasingly moribund precepts on the one hand and West Coast jazz's ambitions toward "art" on the other, the music was reviled as beatless black noise--hate music, even. These jazz pundits, the vast majority of whom were white, appeared to take personal offense at artists whose musical ideas were shaped in part by the same social forces that inspired the civil rights and Black Nationalist movements.

Due in large part to the conservative forces in the recording industry and radio, the New Thing, as the music was also called, was at best a peripheral phenomenon; the passage of time has done little to ameliorate matters. Incredibly, a good many players, now grand old men of the tradition, continue to produce music that is startlingly fresh and decidedly off the beaten track. Bassist Reggie Workman is a prime example. Cerebral Caverns, his current release (Postcards Records), is more evidence that the New Thing remains just that.

Workman surrounds himself with stellar talent. In addition to the nucleus of his group on 1994's Summit Conference (Postcards)--multi-instrumentalist Sam Rivers on tenor and soprano saxophones and flute, and Julian Priester on trombone--Workman brings aboard pianist Geri Allen and ex-Miles Davis drummer Al Foster, who appears on two tracks (Gerry Hemingway supplies the pulse on the remaining cuts).

As on Summit Conference, the spirit of community and mutual admiration is fully evident on Cerebral Caverns. Even more than the former, this session reveals the bassist's attraction to the new. The sonic terrain, along with the personnel, shifts from tune to tune. Elements of free improvisation, European classical and eastern music entwine to form a wholly individual sound.

This is an egalitarian undertaking with no one performer dominating the music's direction. On the pensive "Half of My Soul (Tristan's Love Theme)," for instance, Allen states the theme and engages in a dialogue with Rivers' flute, only to settle back into a progressively swinging mix of brass, strings and percussion. Elizabeth Panzer's harp shimmers delicately, as if her instrument were designed specifically for the occasion.

"Seasonal Elements (Spring-Summer-Fall-Winter)" is presented sans brass or percussion. The harp, piano and Workman's bowed bass conspire in the creation of an idiosyncratic tapestry of sound and silence, light and dark.

When, after introducing the theme, Workman leaves aside his bow to pluck out a buoyant bass pattern, Panzer's harp weighs in with biting, guitarlike interjections. Allen, meanwhile, introduces herself by stroking the innards of her piano, producing an eerie, brittle sound.

The title track finds Garrison and company exploring similar terrain, only this time, the feeling is darkly atmospheric, almost claustrophobic. Again, flute and harp engage in sporadic hide-and-seek interplay, but the mood is more agitated.