SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER/FALL, 2017

VOLUME FOUR NUMBER THREE

ESPERANZA SPALDING

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

JAZZMEIA HORN

(August 12-18)

ROY HAYNES

(August 19-25)

MCCOY TYNER

(August 26-September 1)

AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE

(September 2-8)

AARON DIEHL

(September 9-15)

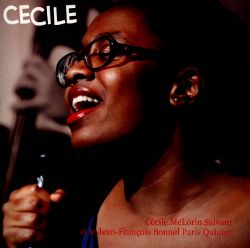

CECILE MCLORIN SALVANT

(September 16-22)

REGGIE WORKMAN

(September 23-29)

ANDREW CYRILLE

(September 30-October 6)

BARRY HARRIS

(October 7-13)

MARQUIS HILL

(October 14-20)

HERBIE NICHOLS

(October 21-27)

GREG OSBY

(October 28-November 3)

Biography

AUDIO: <iframe src="https://www.npr.org/player/embed/454561106/454673622" width="100%" height="290" frameborder="0" scrolling="no" title="NPR embedded audio player"></iframe>

"I never wanted to sound clean and pretty," she says. "In jazz, I felt I could sing these deep, husky lows if I want, and then these really tiny, laser highs if I want, as well."

In 2010, when she was just 21, McLorin Salvant showcased her highs and lows at the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Vocals Competition, where she was awarded first place. Her 2013 album, WomanChild, was named one of the year's 10 best in the 2013 NPR Jazz Critics Poll, and won the award for jazz album of the year in the 2014 DownBeat Critics Poll. Her new record is For One to Love.

Onward and Upward with the Arts

Cécile McLorin Salvant’s Timeless Jazz

Only a few years into her career, the singer has absorbed the music’s history and made it her own.

by Fred Kaplan

The New Yorker

Wynton Marsalis said, “You get a singer like this once in a generation or two.”Photograph by Richard Burbridge for The New Yorker

On a Thursday evening a few months ago, a long line snaked along Seventh Avenue, outside the Village Vanguard, a cramped basement night club in Greenwich Village that jazz fans regard as a temple. The eight-thirty set was sold out, as were the ten-thirty set and nearly all the other shows that week. The people descending the club’s narrow steps had come to hear a twenty-seven-year-old singer named Cécile McLorin Salvant. In its sixty years as a jazz club, the Vanguard has headlined few women and fewer singers of either gender. But Salvant, virtually unknown two years earlier, had built an avid following, winning a Grammy and several awards from critics, who praised her singing as “singularly arresting” and “artistry of the highest class.”

She and her trio—a pianist, a bassist, and a drummer, all men in their early thirties—emerged from the dressing lounge and took their places on a lit-up stage: the men in sharp suits, Salvant wearing a gold-colored Issey Miyake dress, enormous pink-framed glasses, and a wide, easy smile. She nodded to the crowd and took a few glances at the walls, which were crammed with photographs of jazz icons who had played there: Sonny Rollins cradling a tenor saxophone, Dexter Gordon gazing through a cloud of cigarette smoke, Charlie Haden plucking a bass with back-bent intensity. This was the first time Salvant had been booked at the club—for jazz musicians, a sign that they’d made it and a test of whether they’d go much farther. She seemed very happy to be there.

The set opened with Irving Berlin’s “Let’s Face the Music and Dance,” and it was clear right away that the hype was justified. She sang with perfect intonation, elastic rhythm, an operatic range from thick lows to silky highs. She had emotional range, too, inhabiting different personas in the course of a song, sometimes even a phrase—delivering the lyrics in a faithful spirit while also commenting on them, mining them for unexpected drama and wit. Throughout the set, she ventured from the standard repertoire into off-the-beaten-path stuff like Bessie Smith’s “Sam Jones Blues,” a funny, rowdy rebuke to a misbehaving husband, and “Somehow I Never Could Believe,” a song from “Street Scene,” an obscure opera by Kurt Weill and Langston Hughes. She unfolded Weill’s tune, over ten minutes, as the saga of an entire life: a child’s promise of bright days ahead, a love that blossoms and fades, babies who wrap “a ring around a rosy” and then move away. When she sang, “It looks like something awful happens / in the kitchens / where women wash their dishes,” her plaintive phrasing transformed a description of domestic obligation into genuine tragedy. A hush washed over the room.

Wynton Marsalis, who has twice hired Salvant to tour with his Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, told me, “You get a singer like this once in a generation or two.” Salvant might not have reached this peak just yet, he said. But, he added, “could Michael Jordan do all he would do in his third year? No, but you could tell what he was going to do. Cécile’s the same way.”

It was only because of a series of flukes that she became a jazz singer at all. Cécile Sophie McLorin Salvant was born in Miami on August 28, 1989. She began piano lessons at four and joined a local choir at eight, all the while taking in the music that her mother played on the stereo—classical, jazz, pop, folk, Latin, Senegalese. At ten, she saw Charlotte Church, a pop-culture phenomenon just a few years older, singing opera on a TV show. “This girl was making people cry with her singing,” Salvant recalled, sitting in her apartment, a walkup on a block of brownstones in Harlem. “I was attracted by how she could tap into emotions like that. I said, ‘I want to do that, too.’ ”

She grew up in a French-speaking household: her father, a doctor, is Haitian, and her mother, who heads an elementary school, is French. At eighteen, Cécile decided that she wanted to live in France, so she enrolled at the Darius Milhaud Conservatory, in Aix-en-Provence, and at a nearby prep school that offered courses in political science and law. Her mother, who came along to help her get settled, saw a listing for a class in jazz singing and suggested that Cécile sign up.

“I said, ‘O.K., whatever,’ ” Cécile told me. “I was passive—super passive.” At an audition for the class, she sang “Misty,” which she knew from a Sarah Vaughan album that her mother often played. After she finished, the teacher, who’d been accompanying on piano, asked her to improvise. She didn’t know what that meant, nor did she care. “I didn’t want to get into his class anyway,” she recalled. “I had poli-sci, law, classical voice—I didn’t have time.”

But the teacher, a jazz musician named Jean-François Bonnel, was astonished by her singing. “Cécile was something else,” he wrote to me in an e-mail. “She already had everything—the right time, the sense of rhythm, the right intonation, an incredible Sarah Vaughan type of voice”—a pure bel canto, with exceptional range and precision. Two days later, Bonnel ran into her on the street and told her that he’d come ring her doorbell until she signed up for his class. “I always obeyed my parents and my teachers,” Salvant recalled, with a laugh. She enrolled, and found that she liked it. “There were all these cool people with dreads and cigarettes,” she said. “It was very different from the classical-music program, with these precious girls, or the poli-sci school, which was full of rich kids from Saint-Tropez, very arrogant, politically on the right. I had nothing to say to those people. So I figured the jazz department would be like a good hobby—a place to make friends, like going to a community-theatre class.”

Soon, Bonnel formed a band for Salvant—he played piano, other students played bass and guitar—and, within three months, booked their first gig, at a local music hall. He also began putting Salvant through a crash course in jazz history. “He gave me recordings, twenty CDs at a time, which I played again and again,” she said. He started her with Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, and Billie Holiday—all of their albums, not just the ones her mother had played. Then came the early blues singers. “I listened to Bessie Smith’s complete recordings non-stop, all day,” she said. “I hated them at first, but eventually fell in love with her world. These songs were amazing. She sang about sex and food and savages and the Devil and Hell and really exciting things you don’t hear on ‘Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Cole Porter Songbook.’ I thought, This is great! All these great stories! I’d heard torch songs by Dinah Washington about ‘I’ll wait for you forever.’ But here’s Bessie Smith singing, ‘You come around after you been gone a year? Goodbye! ’ It was empowering.” She went on to albums by later singers who fused jazz standards with earthy blues, especially Abbey Lincoln, who brought political consciousness and dissonant note-bending to the saloon-song tradition. “After coming from Sarah Vaughan, Abbey Lincoln felt harsh and a little depressing, too edgy and cold,” Salvant said. “I slowly began to love that edge, and went through a period when I didn’t like Sarah Vaughan because she didn’t have that edge.”

Toward the end of that year, Bonnel and Salvant were driving back from a jazz festival in Ascona, Switzerland. On the road, “just for fun,” he remembers, she did impressions of the great jazz singers—Vaughan, Fitzgerald, Holiday, Carmen McRae. “It was incredible,” he told me. She mimicked not only the sound of their voices but also their phrasings, rhythms, breaths. Bonnel’s next task was to prod her into finding her own way with this material. In class, he told her to focus on the piano, molding the songs’ harmonies into her fingers and improvising new melodies on top of them.

At this point, she wasn’t intent on becoming a jazz singer. She had kept studying classical voice, and performed a few Baroque recitals in small churches. “The reason I turned to jazz was the gigs were coming in,” she said matter-of-factly. “If more gigs had come in with Baroque, I’d have tried to do both.” She recorded an album, called “Cécile,” with Bonnel’s band, and by 2010 she was singing throughout Europe. She figured that she’d give her jazz career three years to take off. She was twenty, young enough that, if things didn’t work out, she could go back to school and try something else—maybe history or literature or law.

One afternoon, Salvant and I went out for lunch around the corner from her apartment, at a small, brick-walled place called Il Caffe Latte, on Malcolm X Boulevard. Salvant, stirring an iced coffee, seemed unaccustomed to being out in the middle of the day. When she’s not on the road, she maintains a scholarly routine. “I’ll listen for an hour to a record of someone soloing, and I’ll sing along, improvising,” she said. “I’ve been listening to Benny Golson, Coleman Hawkins, Oscar Peterson, Sonny Rollins. When you listen to a solo a lot, it’s like you’re trying to get in a person’s brain. ‘Why did Coltrane do this instead of that?’ ”

Onstage, Salvant projects confidence and subtle theatricality; offstage, she’s warm, smart, and funny, but also reserved and nervous, her voice more nasal than smoky. As she tells it, she is not a natural performer. “The first year I sang before audiences, I closed my eyes the whole time,” she said. “After a while, I gave myself a challenge: try to look at people for a nanosecond, catch their eyes—see if I melt.” As Salvant’s mother watched her career develop, she was eager to see her succeed but didn’t want to push her toward a life as a professional musician. “I never thought she would go where she is now,” Léna McLorin Salvant, a tall, assertive woman who speaks with a pronounced French accent, says. “She’s an intellectual. I thought she would go into academics.”

Still, while Salvant was in school, her mother became interested in the Thelonious Monk competition, which is held annually—the closest thing that the commercially modest jazz industry has to “American Idol.” Each year highlights a different instrument, and in 2010 it would be a singing competition. Léna insisted that Cécile record an audition disk. “Cécile is very malleable, she’s very open, and I take advantage of that,” Léna told me. “I told her the contest would be a good experience.”

Cécile sent in a disk just before the deadline, and she was chosen as one of twelve semifinalists, out of two hundred and thirty-seven applicants. In October, she was flown to Washington, D.C., for the first phase of the contest, before a live audience, at the National Museum of the American Indian. She was twenty-one and completely unknown in her own country.

As she faced the crowd, she seemed tentative. Ben Ratliff wrote in the Times that she “looked like an English teacher wearing a sensible black dress with magenta ballet flats” and “stared inquisitively at the house: really stared, as in ‘it’s not polite to stare.’ ” Her mother, who was in the audience, heard people laughing. “They were saying, ‘Who’s she?’ and ‘She’s not glamorous,’ ” she recalled. “I thought, Oh, no, why did I put her through this?”

Salvant launched into “Bernie’s Tune,” a cool-bop anthem by Gerry Mulligan, followed by “Monk’s Mood,” a knotty melody by Thelonious Monk, and “Take It Right Back,” a raucous Bessie Smith blues. “She had people eating out of her hand—it was ridiculous,” Al Pryor, the A. & R. chief at Mack Avenue Records, who was also in the house, recalled. “I knew that I had to sign her up.” Rodney Whitaker, the bassist hired for the rhythm section that accompanied the contestants, knew she was going to win even during the pre-show rehearsal. “I’d never met anyone that young who’d figured out how to channel the whole history of jazz singing and who had her own thing, too,” he later told me. She and two other women made it into the finals. The next day, after a second round of competition, at the Kennedy Center, Salvant was declared the winner.

Afterward, she flew back to France to finish her law courses, but she quickly realized that New York was where a jazz singer needed to be. Pryor offered her a contract. So did Ed Arrendell, a prominent talent manager. In early 2012, she moved to Manhattan, on her own for the first time. “My concern was: How can I deal with the solitude of a creative life style?” she told me. “I’d been used to being a good student—get good grades, follow whatever structure I’m in. Now it was the idea of letting all that go, working from home—what a nightmare!”

Unnerved, she did what she was accustomed to doing: she enrolled in classes on composition and music theory at the New School, in Greenwich Village. But Arrendell was eager to jump-start her career. He sent her some names of pianists she might enjoy singing with. She particularly liked a YouTube video of a pianist named Aaron Diehl playing Fats Waller’s “Viper’s Drag”—precise, soulful, and joyous all at once. “It was exciting to see somebody play Fats Waller with a fresh take yet very much in the spirit of the music,” she said. “I’d been trying to do this for years—take something old and make it yours but still authentic—and here was someone who’d figured it out.” She called him, and they met. “He was very versatile, very serious, and didn’t seem to be an asshole,” she recalled. “Those were the boxes I checked off.”

Their first gig was at the Kennedy Center. More gigs followed, with Salvant fronting Diehl’s trio (including Paul Sikivie on bass and Lawrence Leathers on drums), and the musicians coalesced into a working band, on the road three weeks out of every month. She also recorded an album, called “WomanChild,” for Mack Avenue, which received a Grammy nomination for Best Jazz Vocal Album. (Her next album, “For One to Love,” won the award.) Meanwhile, she flunked her composition course at the New School because she had an out-of-town gig on exam day. She dropped out, no longer needing the academic structure.

Before a recent tour in France, Salvant stopped by Aaron Diehl’s apartment one afternoon to rehearse some songs. The two live in the same building, Salvant on the top floor and Diehl on the parlor and ground floors. “It’s like the pros of having a roommate without the cons,” she said.

Video: Cécile McLorin Salvant sings “Wives and Lovers”

Salvant wanted to try out a new discovery, a song from the nineteen-twenties called “Dites-Moi Que Je Suis Belle” (“Tell Me I’m Pretty”), by a cabaret singer named Yvette Guilbert. She played a YouTube clip of it on her phone, and sang along in a quiet, crystalline voice. They spent half an hour exploring ways to make it sound like jazz. Diehl picked out the chords, then tinkered with them, thickening the harmony; he added a pop-tune bass line, then discarded it in favor of a vamp that opened some space between choruses. Diehl is Juilliard-trained, academic in demeanor, attuned to the logical structure of a song. But he deferred to Salvant, partly because she’s the band’s leader and partly because, he told me, “she has much better ears than I do.”

Once they’d worked out a plausible arrangement, he asked her, “Will you be changing the phrasing of the melody?”

“I’ll do that however this ends up,” she replied. “But I want this to progress from shy and coy to desperate and a little intense and angry.” She’d read that the song was one of Sigmund Freud’s favorites, and her idea was to reclaim a frothy ditty as an enraged critique. They agreed to work on it more at their next rehearsal.

The singer Dee Dee Bridgewater, who was a judge at the 2010 Monk competition, told me, “I had never seen someone as young as Cécile invest in a lyric and tell a story in the manner that she did.” This impulse to dramatize a song, treating it less as a monologue than as a play, sets Salvant apart from other jazz singers, even from many of the great ones. “To me, performance is acting as a character on the stage,” Salvant said. “Trying to get inside a world for other people and getting them to join in—that’s thrilling.” As her early stagefright waned, she began to conceive of a song as a conversation between her and the audience. “I’m not just singing words that are strung together,” she said. “They’re a story. So who am I telling the story to? Not to the band. They’re into making it sound good. I needed to acknowledge there are people in front of me. They’re not my enemy. I’m sharing something with them.”

Salvant looks back on the week at the Village Vanguard—some of which was recorded for an album that will be released later this year—as a breakthrough. She dislikes listening to herself, and cringes at excess acrobatics: “It’s like I’m saying, ‘Listen! Please! Like this! I really worked hard on this!’ I don’t want that desperation in my voice. I want to be natural and free and adventurous.” In the weeks leading up to the Vanguard dates, she talked with the band about this habit and came up with a way to break it. “I said we should play like we’re old—people who have lived and now we’re natural,” she recalled. “I want to act sixty years old. Desperation is a young person’s thing. If I’m old, I’m not thinking, What can I be? I’m getting too old for that shit.”

Al Pryor, of Mack Avenue, told me that when he heard Salvant at the Monk competition he wondered how she had acquired such broad knowledge of the music. He said, “She seemed to be an old soul in a young woman.” Pryor was onto something. Salvant told me that, when she was a kid in Miami, her friends nicknamed her Grandma. “I walked slow,” she said. “I was interested in old things—old books, old music.” When she went through a death-obsessed phase, as many teen-agers do, she consoled herself by reading Guy de Maupassant. Aaron Diehl, who is four years Salvant’s senior, told me, “I look at her as an older sister.”

I asked Salvant if, like many musicians, she’d thought of covering contemporary pop songs. She winced. “It’s fine,” she allowed. “There are some new songs that I really like, but I never think, Maybe I’ll sing this song. I don’t care whether what I do is modern or of our time. I want to sing songs that have this timeless quality. I’m interested in history—how things differ, how they’re still the same. I love it when a song is a hundred years old but still connects.”

But, she said, “I’m finding it hard to find these songs. Maybe I need to figure out something new. Sometimes I’d like to be more outrageous—like write a musical play, or do a one-woman show, or design outlandish costumes and wear them, or somehow combine my visual art with my music.” (She sketches and paints on the road, and illustrated the cover of “For One to Love.”) “I have a notebook full of drawings and ideas. I call it ‘My Book of Imaginary Projects.’ If I tried them, I feel they’d be a catastrophe. But maybe I should try one.”

In a phone conversation after the Presidential election, Salvant said, “The current political landscape is making me feel I want to be messier, sing more political songs, write more political songs.” She’d recently given a lecture at the Chautauqua Institute, in upstate New York, on the history of race and women in popular culture. In it, she dwelled on the nineteenth-century phenomenon of black entertainers performing in blackface, which many have found demeaning but which she sees as a form of rebellion—African-Americans reclaiming their own stories. She talked about parallels to songs of the nineteen-thirties, like Josephine Baker’s “Si J’Étais Blanche” (“If I Were White”), and songs from the sixties, like Burt Bacharach’s “Wives and Lovers,” which warns women to be sexy for their men so that they don’t run off with someone else.

“A friend once asked me why I didn’t sing more feminist songs,” Salvant recalled. “I said it’s hard to find feminist jazz songs. But I thought about it, and I wondered if there were sexist songs that I could make fun of. I went online, looked up the ten most sexist songs in American pop history. ‘Wives and Lovers’ was the best. And Aaron happened to love that song. Rhythmically it’s great, and the words sound wonderful.”

She sang both songs at the Vanguard the night I saw her. She treated the Baker as a haunting dirge, lingering on the words “I’d like to be white / How happy I would be.” She turned the Bacharach into a subversive anthem of assertiveness, purring its opening lines with a mix of come-hither bounce and menace: “Hey, little girl / comb your hair / fix your makeup / Soon he will open the door.” In the silence after the song ended, I could hear sighs all around me, the collective release of an uncomfortable tension.

The lyrics of “Wives and Lovers” are “ridiculous,” Salvant told me later. “But they’re also things I really do. I’m not completely over the idea of needing to be presentable and looking my best. It’s advice that I’ll almost take, then say no. The songs that I sing and kind of make fun of—they have some kind of power over me. By making fun of them, I weaken that power.”

Later, while Salvant and Diehl were on tour in France, she wrote to me in an e-mail that they had been performing “Dites-Moi Que Je Suis Belle,” the Freud favorite turned feminist howl. The audiences seemed to get the irony, reacting with a “curious, nervous mood,” like the one that “Wives and Lovers” inspires in American audiences. But Salvant and Diehl wanted to work on it more. “I just want it to be leaner and more incisive,” she wrote. “Not sure if it has to even be funny. Also, wanting to do some digging for other songs like that, asking, ‘Am I pretty?’ I wonder if they are as rare as I think.” ♦

This article appears in other versions of the May 22, 2017, issue, with the headline “Kind of New.”

More:

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/cecilemclor

Cecile McLorin Salvant

Biography

Articles

News

Cécile

McLorin Salvant was born and raised in Miami, Florida of a French

mother and a Haitian father. She started classical piano studies at 5,

and began singing in the Miami Choral Society at 8. Early on, she

developed an interest in classical voice, began studying with private

instructors, and later with Edward Walker, vocal teacher at the

University of Miami.

In

2007, Cécile moved to Aix-en-Provence, France, to study law as well as

classical and baroque voice at the Darius Milhaud Conservatory. It was

in Aix-en-Provence, with reedist and teacher Jean-François Bonnel, that

she started learning about improvisation, instrumental and vocal

repertoire ranging from the 1910s on, and sang with her first band. In

2009, after a series of concerts in Paris, she recorded her first album

“Cécile”, with Jean-François Bonnel's Paris Quintet. A year later, she

won the Thelonious Monk competition in Washington D.C.

Cécile

performs unique interpretations of unknown and scarcely recorded jazz

and blues compositions. She focuses on a theatrical portrayal of the

jazz standard and composes music and lyrics which she also sings in

French, her native language as well as in Spanish. She enjoys popularity

in Europe and in the United States, performing in clubs, concert halls,

and festivals accompanied by renowned musicians like Jean-Francois

Bonnel, Rodney Whitaker, Aaron Diehl, Dan Nimmer, Sadao Watanabe, Jacky

Terrasson (she was the guest singer on his latest album, Gouache),

Archie Shepp, and Jonathan Batiste. She is the voice of Chanel's

“Chance” ad campaign for the third consecutive year. In August 2012,

Cécile recorded WomanChild for the Mack Avenue Label with Aaron Diehl,

Rodney Whitaker, Herlin Riley and James Chirillo.

Cécile

has performed at numerous festivals such as Jazz à Vienne, Ascona,

Whitley Bay, Montauban, Foix, with Wynton Marsalis and the Jazz at

Lincoln Center Orchestra in New York’s Lincoln Center and Chicago’s

Symphony Center and with her own band at the Kennedy Center, the Spoleto

Jazz Festival, Detroit Jazz Festival and other venues.

Cécile's “WomanChild” was nominated for the 2014 Grammy Award for Best Jazz Vocal Album.

Music Interviews

Jazz Singer Cécile McLorin Salvant Doesn't Want To Sound 'Clean And Pretty'

39:06

AUDIO: <iframe src="https://www.npr.org/player/embed/454561106/454673622" width="100%" height="290" frameborder="0" scrolling="no" title="NPR embedded audio player"></iframe>

November 4, 2015

Heard on Fresh Air

Cécile McLorin Salvant's repertoire includes jazz standards, forgotten old songs, show tunes and originals. Mark Fitton/Courtesy of the artist

Growing up in Miami as the child of a Haitian father and a French mother, singer Cécile McLorin Salvant heard a wide range of music, including that of jazz singer Sarah Vaughan.

"I think I started really falling in love with [Vaughan's] voice when I was about 14," McLorin Salvant tells Fresh Air's Terry Gross.

By that time, McLorin Salvant had already begun training in classical voice. But as she listened to Vaughan, she says, she was drawn to a singing style that felt less constrained than the classical style she'd been studying. Eventually, she shifted her attention to jazz.

"I never wanted to sound clean and pretty," she says. "In jazz, I felt I could sing these deep, husky lows if I want, and then these really tiny, laser highs if I want, as well."

In 2010, when she was just 21, McLorin Salvant showcased her highs and lows at the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Vocals Competition, where she was awarded first place. Her 2013 album, WomanChild, was named one of the year's 10 best in the 2013 NPR Jazz Critics Poll, and won the award for jazz album of the year in the 2014 DownBeat Critics Poll. Her new record is For One to Love.

Interview Highlights

On the influence of Sarah Vaughan

I was really mostly interested in classical singing, but she had something in there that drew me in, coming from being interested in classical singing. She was an absolute virtuoso, and she could have so many colors and textures with her voice. When I moved to France and started singing jazz and studying it, she was maybe the first person that I would copy. And it became less about sounding unique — I didn't even care about that. I just wanted to sound as much like her as I possibly could. So I'd spend a lot of time listening to her and seeing how I could make my voice sound like that.

Related NPR Stories:

First Listen

Review: Cécile McLorin Salvant, 'For One To Love'

Music Articles

Authentic Early Jazz, From A 23-Year-Old 'WomanChild'

A Blog Supreme

Cecile McLorin Salvant, Vocalist, Wins Thelonious Monk Jazz Competition

Eventually, I moved on to other singers. Billie Holiday was a big one where I would pay attention to the way she would pronounce words, the way even just her accent — all of that became really interesting to me, and vibrato and all of that. Eventually, the more I listened and became obsessed with singers, I feel like the more I realized that I had my own little thing that I could do. So this is why I just became obsessed with looking for new singers, unknown singers, people that maybe have been forgotten, and really checking them out and analyzing what they do. ... I think the core of my work on music has been just listening to things, listening to singers.

On performing a song by Bert Williams, a black man who performed in blackface in the early 1900s

Just reading that a person can be black and still perform in blackface, making fun of black people for a living, and at the same time be a genius and be an incredible entertainer, and at the same time be extremely conflicted and feel terrible for doing that, essentially which is what Bert Williams felt, from what I gather, from what I read, all of that was so incredible to me. Just reading that, I just thought was so fascinating. ... I just looked up the song "Nobody," which is the hit song that he wrote, and it was so amazing. He's talking over music, and then he starts singing the chorus, and it was very funny, of course, because he's just the pathetic guy that gets no respect. But it was also heartbreaking, and that's something about a song that I love — is when you can find those two elements. You don't know if you want to laugh or cry. It took me some time to have the courage to actually sing it.

On becoming a jazz singer after years of training to sing classical music

I did everything I could to not bring in any of the technical things I got from classical into jazz, and I did everything to really base it on my speaking voice and to just not try to make it sound pretty. I always wanted to have kind of a certain natural quality to my voice, and I wish it were more rough than it is, but I would listen to a lot of blues singers and sort of try to go more towards that.

I had a hole in my voice. I still do. We call it a hole, but it's an area in the voice where it's air. And my classical teachers were just so frustrated with me because I would have these deep, low notes that were really strong, and the higher register was strong, but right in the middle area, it was really hard. There was like a passage. But I realized that in jazz, I could take advantage of that.

THE BLOG

September 1, 2017

Young Vocalist/Composer Cécile McLorin Salvant Plays Jazz on Her Own Terms—From Eclectic Styles to Feminist Backlash

by Dan Ouellette

ZEALnyc Senior Editor

August 31, 2016

For the dynamic and creative jazz vocalist Cécile McLorin Salvant to be largely unaware that the idiom was still vitally alive as she grew up is part of the good news of her ascent as the top singer in the music these days, remarkably at the age of 26. In a sense she was protected from the waves of fleeting popularity and did not participate in the proliferation of mid-tier singers who sought to emulate the legends of the music, from Billie Holiday to Ella Fitzgerald to Sarah Vaughan—most with sorry results.

In fact, when Cécile saw the jazz light while an 18-year-old college student studying classical music and law in Aix-en-Provence, France, she was not weighed down with legacy and expectations. Instead she was freed to approach jazz on her own terms, contributing a fresh voice of eclectic tastes and quickly rising to the top—becoming the international jazz darling, winning critics poll awards left and right with her embrace of tradition as well as her burgeoning compositional prowess. She won the top vocalist honors in 2010 at the distinguished Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition (placing high on the phrasing and rhythmic flexibility measures) and scored the top jazz vocalist Grammy Award earlier this year for her impressive For One to Love recording.

Born and raised in Miami by a Haitian father and French mother, Cécile grew up with music—lots, she said, while being interviewed at the North Sea Jazz Festival in Rotterdam this summer on the occasion of her winning the prestigious 2016 Paul Acket Award voted upon by 140 international critics weighing in on the year’s most important emerging talent that is deserving wider recognition.

“My mother loves music which made me have a wide listening ear,” Cécile told me onstage at the festival’s Jazz Café Talking Jazz series on the eve of her Saturday, July 9 performance there. “What I’m doing now all goes back to my childhood. She always listened to a broad range of music—not just jazz or classical. She listened to pop music and folk music from all over the world. I remember learning Paraguayan folk songs as a young girl and listening to music from Senegal and Cape Verde. It was part of my everyday life, with a new album being played from a completely remote country I had never imagined existed.”

So Cécile experienced music without considering style or era or where it came from. “Since I grew up hearing all the different sounds, including on my own, grunge, I’ve kept that with me,” she said, noting that her mother forced her to play the piano when she was 4 which she sometimes reluctantly continued studying at home till she was 18. “So even today I know that I want to listen to a broad variety.”

As for jazz, Cécile said that it was only when she got to France that she got exposed to the wealth of the music that she wasn’t aware of. “I didn’t think people were still playing jazz,” she said. “We were in Miami, so the most exposure I got was from my mother’s records, singers like Sarah Vaughan and Shirley Horn, who had all passed away. So I had no knowledge of current jazz musicians until I came to France.”

At the Conservatory Darius Milhaud, she took a class with clarinetist Jean-François Bonnel. Even though she wanted to major in classical voice, Bonnel not only taught the basics for singers—self-discipline and how to teach—he also exposed Cécile to jazz. “In his class, each week he’d bring in a stack of CDs of singers, many of whom had been overlooked or forgotten,” she said. “Then we’d discuss them the next week and he’d ask us to think about the songs we’d like to sing. In the beginning, it was frustrating and I felt lost. But I did develop a sense of autonomy in choosing and learning songs.” In other words, unlike other music schools, a canon was not pushed out as sacrosanct.

This came in handy years later after she had won the Monk Competition, when traditionally, record labels zoom in on the winner, sign and then dictate the repertoire for the subsequent recording. Was there pressure to do something like an Ella Fitzgerald tribute album? Cécile laughed and said, “I shopped around at different labels. I’m sure at most there would have been pressure, and I would have said, OK, whatever you guys want. But I went to Mack Avenue and they were totally trusting in my repertoire and my musical choices. I’m not an extremely firm person or confrontational, but I knew that starting out I needed to be in a situation where the label could tell me it trusted me.” (The resulting album, ChildWoman, released in 2013, garnered her a Grammy nomination and the top album and top vocalist awards in the DownBeat Critics Poll.)

ChildWoman was officially her second recording, the first self-titled album was recorded in Paris when she was 18 and just starting to sing jazz. So impressed by her growing prowess as a jazz singer, Bonnel instigated the project. He put together a band he dubbed the Paris Quintet. “I was freaking out,” Cécile said. “This was a huge deal. I was 18 and had only begun singing jazz six months earlier.” Being bit by the jazz bug, there was no turning back for Cécile. “Aix-en-Provence is a small town, so I used to go to Paris like four times a year to check out the jazz clubs. But I was shy, so at the jam sessions I just sat in back. Some people would be elbowing their way onto the stage, but not me. I was a spectator.”

Soon that would change. While still described as shy, the Harlem-based Cécile is no wallflower. At North Sea, I played a few of her songs from For One to Love (the artwork she designed for the cover includes a figure that’s “winking and smiling and crying, the perfect embodiment of what the album is about”). The album features songs by the likes of Bessie Smith and the less well-known Blanche Calloway (sister of Cab) as well as an obscure pop song by the Hal David/Burt Bacharach songwriting team. Plus there are five originals, including “Fog,” which was spun first. It’s a composition of doubt and heartache that begins slowly then swings into an upbeat groove halfway through.

“I wrote this after going to San Francisco and walking around with a friend who was showing me the Golden Gate Bridge,” she explained. “There was so much fog, and I thought it would be nice to write a song about the fog. But I got home and forgot about it. A few months went by. The way I write a song is that I sit at the piano for hours and I try to work things out. Eventually something might come of it. So I thought about the fog again, and it started out as a short ballad, but then I said, wait, there’s more to this story. So that’s how the song happened.” She then passed on specific motifs and accompaniment and orchestration to her band to support her voice and the essence of the song.

I also played Cécile’s whimsical rendition of the David/Bacharach song “Wives & Lovers,” which was a small hit for singer Jack Jones in 1963. The lyrics are a straight-‘50s style story of the relationship of a dominant and cheating husband and his submissive wife—hardly politically correct in these days. Cécile laughed when talking about it.

“I originally started looking for a tradition of feminist jazz songs,” she said. “Anything. Standards or even blues. It was very hard. Those songs are extremely hard to find. So I changed my course and started checking out really sexist material to see what’s there. ‘Wives & Lovers’ is on a list of the top 10 most sexist American songs. It’s not the worst ones like domestic abuse. It’s a very light sexism. You’ve got to stay pretty. But I liked the song a lot, its feel, beyond the words, so I recorded it.”

Complaints? “Definitely,” she said, “including comments about my appearance like I should work on growing out my hair and taking off my [white] glasses. Women complain that it’s a sexist song and I shouldn’t be singing it, that it may give their daughters the wrong idea. I didn’t expect that because I was just singing. But it’s exciting in a way to get that kind of reaction. You always wish that you’d get any kind of reaction. So this is nice. It shows that people are listening to the music.”

Shy? Maybe more like spunky.

Today Cécile frequently plays to sold-out houses with good friend rising-star pianist Aaron Diehl and his trio (she also usually plays a song with her own fingers on the keys). He told me, “She has so many facets as an artist, a singer, composer. She’s well-read and able to assimilate all the different elements that seem to be disparate. She’s at the highest level of art—certainly of the time, certainly timeless at the same time.” Cécile accentuated that by telling one scribe, “I like high art and I like enjoying art for art’s sake,” and also noting, “The times change, but emotions don’t. That’s a lot of what jazz singing is about.”

Cécile spends a week at the Village Vanguard (September 6-11) and continues touring nationally, including a September 16 date at the renowned Monterey Jazz Festival, both on the arena-sized Jimmy Lyons Stage and later that evening in the more intimate Dizzy’s Den club.

Cover photo:courtesy of sandiegoreader.com

______________________________________

Dan Ouellette, Senior Editor at ZEALnyc, writes frequently for noted Jazz publications, including DownBeat and Rolling Stone, and is the author of Ron Carter: Finding the Right Notes and Bruce Lundvall: Playing by Ear.

Read more of Dan Ouellette in the following ZEALnyc features:

For all the news on New York City arts and culture, visit ZEALnyc Front Page.

Follow ZEALnyc on Twitter: www.twitter.com/ZEALnyc

ZEALnyc arts - culture - entertainment

Vocalist Cécile McLorin Salvant is an adept jazz singer who came to the public's attention after winning the 2010 Thelonious Monk Jazz Vocal Competition. Born in Miami, Florida to a French mother and Haitian father, Salvant was interested in music from a young age. She began piano lessons at age five and by age eight was singing with the Miami Choral Society. She studied classical voice privately before enrolling at the Darius Milhaud Conservatory in Aix-en-Provence, France, where she studied law as well as classical voice. It was during this time, studying and performing with reed player Jean-François Bonnel, that she became increasingly interested in jazz performance. She released her European debut album, Cécile, in 2009. A year later, she took home the top honor at the Thelonious Monk Vocal Jazz Competition in Washington, D.C. Subsequently, Salvant performed with a variety of artists and even appeared on pianist Jacky Terrasson's 2012 album, Gouache. In 2013 Salvant released her U.S. debut album, WomanChild, on Mack Avenue Records. The album was highly acclaimed and garnered Salvant a Grammy nomination for Best Jazz Vocal Album. In 2015 Salvant returned with her second album for Mack Avenue, For One to Love.

From Monk Competition winner to Grammy nominee

Wynton Marsalis Quintet featuring Cécile McLorin Salvant at Jazz in Marciac 2017:

Cécile McLorin Salvant au Detroit Jazz Festival--May, 2014:

@cecilemclorinsalvant.com facebook.com/cecilemclorinsalvantmusic

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C%C3%A9cile_McLorin_Salvant

A star is born: Cecile McLorin Salvant woos a capacity crowd at 54 Below CD release party

Show and Tell

June 26, 2013

Five years ago, she was a bright girl from a bright Miami high school who finished up completely confused about who she wanted to be. Loved music. Maybe should major in poly sci, though. Really just wanted to take a year off in France to figure it all out.

Today, she has a Thelonious Monk vocal competition win, her first album is in the can and she still feels like her head’s spinning around for an opposite reason – from all the attention to her talent.

Well, Cecile McLorin Salvant, it’s definitely too late for poly sci now. You’re a bona-fide jazz star on the rise.

The 23-year-old chanteuse made her first big mark on the city jazz scene Tuesday night, with a CD release party and two capacity-crowd sets with the Aaron Diehl Trio at 54 Below. By the end of it, she was full of smiles and playfulness with the band, shooting a “Yeah, I like that!” to Diehl during a Billie Holiday standard, bantering with the crowd and losing her place as it laughed with her at her stretched out delivery of the word “Nobody” in her last tune of the night.

McLorin Salvant embodies Keats’ concept of negative capability, easily encompassing two disparate ideas. Close your eyes, and her vocal command puts a much older, soulful singer, maybe even from another era, in your mind’s eye. Open them, and there’s a young woman still trying finding her way. It’s not a coincidence that her CD is called “WomanChild,” with lyrics such as “WomanChild falters/Clumsy on her feet/Wonderin’ where she’ll go.”

“I wrote that song two years ago, and when I wrote it, it was very much a kind of a thing where I was thinking about myself, but also all these people I knew, and this generation of really adolescent people staying adolescent until late in their lives,” she said. “I do think it’s autobiographical, though. It still rings true.”

McLorin Salvant started playing piano at 4, and sang with the Miami Choral Society, but didn’t have much of a jazz upbringing, except for records, in a relatively jazz-starved Miami.

“To be fair, in France was the first time I had actually met jazz musicians, the first time I’d played with a bass player or a sax player,” she said. “You have to really want to get at it, living in Miami. I’d been listening to jazz at home as I was growing up. I would hear it in a passive way. I listened to a lot of different music at home. Senegalese music, classical music. Jazz was just a part of that experience.”

McLorin Salvant was indeed majoring in political science at Aix-en-Provence, and was attending the conservatory on the side. She quickly came to the attention of sax player Jean-Francois Bonnel, who took her in, recorded with her and encouraged her to consider making her side work something much more.

“I just went into (music) class thinking it could be a fun hobby, like doing yoga or theater to empty out stress,” she said. “He heard me and encouraged me from the get-go into thinking I could possibly pursue it as a career.”

Enter the Thelonious Monk competition in 2010. She came in the most underdog of underdogs, utterly unknown, and completely blew away the judges. Not to mention herself.

“It was kind of a huge shock,” she said. “Everyone had gone to a college. An American music school, with a bachelors or masters, or whatever it was. I was coming there only having had one jazz teacher who wasn’t a singer, and his main focus was having me listen to records and play the piano. I was really not expecting to get as far as the semifinals. So it was shock after shock.”

Mack Avenue records signed her and put her together with strong labelmate pianist Aaron Diehl to craft a loving first effort that covers much ground, from standards to roots music to three of her own compositions. Diehl said he was shocked in his own way by her prowess.

“I’ve never heard a singer of her generation who has such a command of styles,” Diehl said. “She radiates authority.”

Meanwhile, McLorin Salvant, in the midst of a maelstrom of attention and accolades that sometimes have a way of bluntly telling you who you are, is OK with the idea that she’s still figuring out a lot of it for herself.

“I think it’s gonna take time,” she said. “Take a while. And not only as a musician, also as a person. I think 23, 24 is a time when you’re still thinking of all the things you could be. And all those possibilities when a child, slowly dwindling away. Just learning to accept that this is how you are and not to expect to be a million different things.”

Cecile McLorin Salvant

(b. August 28, 1989)

Artist Biography by Matt Collar

Vocalist Cécile McLorin Salvant is an adept jazz singer who came to the public's attention after winning the 2010 Thelonious Monk Jazz Vocal Competition. Born in Miami, Florida to a French mother and Haitian father, Salvant was interested in music from a young age. She began piano lessons at age five and by age eight was singing with the Miami Choral Society. She studied classical voice privately before enrolling at the Darius Milhaud Conservatory in Aix-en-Provence, France, where she studied law as well as classical voice. It was during this time, studying and performing with reed player Jean-François Bonnel, that she became increasingly interested in jazz performance. She released her European debut album, Cécile, in 2009. A year later, she took home the top honor at the Thelonious Monk Vocal Jazz Competition in Washington, D.C. Subsequently, Salvant performed with a variety of artists and even appeared on pianist Jacky Terrasson's 2012 album, Gouache. In 2013 Salvant released her U.S. debut album, WomanChild, on Mack Avenue Records. The album was highly acclaimed and garnered Salvant a Grammy nomination for Best Jazz Vocal Album. In 2015 Salvant returned with her second album for Mack Avenue, For One to Love.

Cécile McLorin Salvant looks for the contradictions in jazz

Jazz singer Cécile McLorin Salvant performs in Los Angeles in 2014. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

by Scott Timberg

August 23, 2017

Los Angeles Times

It might seem strange for a very young woman, growing up thousands of miles away from jazz capitals like New York, Chicago and Los Angeles, to be singing standards from the years before World War II. But Cécile McLorin Salvant, perhaps the brightest star among jazz singers under 40, and whose retro glasses make her look like a clerk at a hipster vinyl shop, has always had old-school tastes.

“I like things that are handmade,” Salvant, a 27-year-old Miami native who opens for Brian Ferry at the Hollywood Bowl on Saturday, says by phone. “I’m really into analog photography. Anything that’s handmade has always been a passion of mine. The handmade, homemade quality makes it seem human. And I’m really into history, including the history of American popular music, in all its contradictions.”

In some cases, she’s crooning numbers that have long been part of the jazz canon, for singers and instrumentalists: “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was,” Cole Porter favorites like “Easy to Love,” Fat’s Waller’s immortal “Jitterbug Waltz.”

In other cases, these contradictions include songs that are mid-century-sexist — David-Bacharach’s “Mad Men”-era “Wives and Lovers” — or weirdly racist, like “(You Bring Out) The Savage in Me.” In her originals, she upends the travails of modern romance by giving the tales vintage trappings, utilizing the layers of the past to bring out the deeply layered meanings in the songs — the ways, for instance, in which gender roles have or have not changed.Two years back the Guardian in the UK described “a mischievous intelligence” and called her style “more heightened music theatre than jazz”; in some ways Salvant is as much actor as director: She says she finds these numbers “funny and fascinating,” offering serious tonal challenges to the singer. “I like to see how things play out in history.”

Salvant, whose father is a Haitian doctor and mother a French-Guadeloupean educator, began singing in several other styles before she even came to jazz. In fact, the first time she heard Billie Holiday, as a kid, she was frightened: “Late in life, her voice was that of a scary witch.”

Salvant later came around and found Holiday, Sarah Vaughan, Bessie Smith and others to be major inspirations.

But the teenage Salvant was drawn more immediately by classical and Baroque singing.

“Baroque music is about the jagged edges of music,” she says. “Those songs are 400 years old, but they still work.”

After high school she moved to the south of France, taking voice lessons at the Conservatoire Darius Milhaud. A visit to a class taught by a jazz saxophonist, and her interest in improvisation — once a major part of classical music but harder to find more recently — put her on a new path.

Still, her interests remain wide, from the novels of Virginia Woolf to the poetry of Langston Hughes to the choreography of Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker. “I get excited by jazz singers, but that’s such a small percentage of what I’m influenced by. I’ve always been really influenced by people who have contradictory influences in their work, and somehow it comes together in a cool way. I love clashing things.”

Salvant broke out hard in 2013 with the “WomanChild” LP, three years after winning the Thelonious Monk Vocal Jazz Competition. She's toured consistently, including gigs at Catalina’s and the Playboy Jazz Festival, but has released only one album since — “For One to Love,” which won a Grammy last year.

In reviewing the work, The Times’ Mikael Wood wrote, “her feel for subtext makes her one of the smartest (and funniest) interpreters going. In ‘Stepsisters’ Lament,’ from ‘Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Cinderella,’ the wide-open quality of her voice makes you believe she’s identifying with the song’s narrator, who can’t understand why men routinely opt for ‘a frail and fluffy beauty’ over ‘a solid girl like me.’”

At the end of September she’ll release an unusual double album: Some of “Dreams and Daggers” (released, like the others, on Mack Avenue) is live, some is in studio with a string quartet, and much of it involves original numbers. Salvant aimed to write new songs that bridged the recording’s standards like “You’re My Thrill” and “My Man’s Gone Now.”

Here, again, this 20-something Bessie Smith fan is being old-school: She admires the way artists like Solange and Frank Ocean make albums designed to be listened to all the way through. Salvant calls it “a renewal of the idea of a whole work of art.”

Overall, with a style that is intimate and reasonably understated for a jazz artist — she seems a natural for a place like the Village Vanguard or Largo at the Coronet — the Bowl poses a challenge. She’s sung there and in huge outdoor venues before, but admits that these places can be tricky. “We like our sound to be as acoustic as possible, and it can be hard to get the balance right. It’s so enormous — you have to remind yourself there are people out there.”

The Bowl booking of Salvant behind Ferry is, as she calls it, “kind of a crazy mix”: A 71-year-old English art-rock singer who loves Charlie Parker, following a black jazz singer, a third his age, with a European education and affinities. On second thought, says Salvant: “Whoever came up with this … is kind of brilliant.”

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Bryan Ferry with Cécile McLorin Salvant

Where: Hollywood Bowl, 2301 N. Highland Ave.

When: 8 p.m. Saturday

Tickets: $17 — $196

Information: www.hollywoodbowl.comWitnessing the brilliance of Cecile McLorin Salvant

September 5, 2017

JerryJazzMusician

Cecile McLorin Salvant at the Old Church

Portland Oregon, Aug 30, 2017

Last week I had the privilege of attending a show in Portland by vocalist Cecile McLorin Salvant, the fast emerging superstar of jazz, of whom Wynton Marsalis has said “you get a singer like this once in a generation or two.”

The show – performed at the city’s 300 seat Old Church on August 30 – was one of the more astounding jazz performances I have ever seen. Having been to hundreds (hell, probably thousands by now) of shows over the years in venues all over the globe, that is saying something! I came away feeling as if I witnessed contemporary “greatness” of historic proportions.

Ms. Salvant, a 28-year-old native of Miami, was elegant, breathtaking, sensitive, angry, political, intellectual, adventurous, and everything in between (and always brilliant). So many highlights — including Aaron Diehl’s performance on the Old Church organ, accompanying her on “The Peacocks,” and a spine-tingling a cappella encore that channeled many of her musical ancestors.

If you get a chance to see her perform, do so without hesitation…To read an entertaining and informative biography, Fred Kaplan’s May 22nd piece in the New Yorker is the ticket.

01/20/2016

by Roseanna Vitro

An Interview With Cécile McLorin Salvant

From Monk Competition winner to Grammy nominee

Since the passing of vocal icons Carmen McRae, Nina Simone, Sarah Vaughan and Ella Fitzgerald, fans have wondered, will we ever see this level of talent again? A rightful question. Yet, as a vocal instructor and judge for the Thelonious Monk and Sarah Vaughan competitions, I’ve learned to have complete faith in the future of jazz singing. In a short time, Cécile McLorin Salvant has affirmed that promise.

I recall standing backstage at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., in 2010, watching Monk finalists Salvant, Cyrille Aimée and Charenee Wade. Cécile walked out onstage, dressed simply, demure and understated. She was focused and calm, methodical and hypnotic-she was in charge!

As she sang, her vocal skills became clear; she evinced phenomenal range, phrasing and tonal shading reminiscent of Vaughan, Betty Carter and Bessie Smith. While scatting, she hit her marks with conviction and authority. In short, Salvant stepped out, ultimately showcasing a level of talent rare among modern-day singers.

Since that auspicious beginning, she has toured the world and released two critically acclaimed albums. Her debut release in 2014, WomanChild, was nominated for a Grammy in the category Best Jazz Vocal Album. Her current album, For One to Love, released last year, has proven that lightning can strike twice in the same place-she earned a second Grammy nomination in the Jazz Vocal category.

Salvant has a singular point of view, which underscores her standing in the jazz community. Her sudden arrival is reason enough to feel confident--the future of vocal jazz is in good hands.

Roseanna Vitro: What is your earliest memory of music?

Cécile McLorin Salvant: It’s hard to say; music was always playing in the house when I was growing up. My mother took me to my first piano class when I was about 4. I feel very lucky that from an early age I was exposed to many different genres of music (jazz, Haitian music, R&B, hip-hop, reggae, bluegrass, disco, Motown, classical music, fado, Senegalese and Cape Verdean music, French chanson, folk music from Argentina and Paraguay, among many others). This allowed me to develop a curiosity for music regardless of language, genre or the time in which it was recorded or composed.

RV: Did you know you wanted to be a singer when you were very young? Does anyone in your family sing?

CMS: My father has a beautiful voice, but he never pursued it. I loved to sing, but didn’t only want to be a singer, and certainly didn’t think of being a jazz singer. I remember having a long list of things I dreamt of doing. I wanted to be a history or literature professor, a writer, some kind of visual artist, an actress and an opera singer. But none of these things particularly stood out. I was very happy to be in school and that seemed to be my main focus, I wasn’t really thinking ahead.

RV: I recall reading you began playing classical piano when you were 5 years old. How do you feel classical piano helped to shape your concept as a singer?

CMS: I’m not quite sure. Playing the piano as a child had many benefits for me beyond music. Of course, it developed my ear and sense of musicality and allowed me to experience some important pieces of classical music on a deeper level than I would have as a listener. It was also an obligation! I didn’t particularly want to practice, or go to class, or work on anything extracurricular, but I had to. It taught me that the tedium and loneliness of practicing can lead to something beautiful. I was certainly not the most disciplined piano student, but when I did put in the time and effort, it always paid off. I think this is something that children experience in school with homework and studying, but piano was something beyond school, and ultimately with lower stakes. It was all up to me if I wanted to get better and nothing terrible would happen if I didn’t. I think having that choice to push oneself to try and share something beautiful with others is a really wonderful thing for a child to be confronted with. I also think it’s a wonderful opportunity for any musician to practice more than one instrument, and to really get into other genres of music, because it allows that musician to have another angle, a more global vision of music and its roles. I believe the same can be said for any profession, and any artistic endeavor. It’s good to look at things from another perspective. Today, when I practice and compose, it is almost exclusively at the piano.

RV: Were you a competitive or dramatic child or were you more shy and introverted as a young musician?

CMS: I was terrified when I had to play my annual piano recital! There is something about playing the piano for an audience that still deeply frightens me. However, I loved to perform. In French class, we would regularly have to recite poems, and I was always so melodramatic when I recited them!

RV: Who were the first singers or musicians you wanted to imitate? What spoke to you?

CMS: The first singer I wanted to imitate was Sarah Vaughan! She had such a glorious, warm, versatile, virtuosic voice. I fell in love with her singing long before I started actively listening to jazz.

RV: Were your parents supportive of your music studies? Who were your pivotal vocal teachers and did you perform in school?

CMS: My parents were extremely supportive. I had a classical voice teacher when I was around 13. Her name is Ana Maria Conte Silva. When I was in high school, I started studying classical voice with a teacher at the University of Miami named Ed Walker. I never did music in school.

RV: When I first saw you perform, I thought you must have studied drama in school. You have a way of interpreting your lyrics and painting the story with your voice that’s spellbinding. Did you study acting?

CMS: I was not in the drama department! I auditioned for a music high school when I was 13, to study voice. However, I decided instead to go to Coral Reef High, in the International Baccalaureate program, in part to keep studying French in a rigorous academic program, and in part to be in school with my friends.

RV: What inspired you to study in France after your studies at the University of Miami in 2007? When did you decide, singing and composing might be your career?

CMS: I wasn’t a University of Miami student. I only took private lessons from a teacher who worked there. After high school, I had no idea what I wanted to study, or where I wanted to go. The college application process in the U.S. was making me a bit uneasy. I decided to go to Aix-en-Provence, France, for a year, to experience something different. It was a kind of sabbatical, but rather than move to France with no structure, I enrolled in a political science prep school with an option to complete the first year of a bachelor’s in law. I also wanted to keep studying classical voice, after school, as I had been for a while. It was in this music school that I met Jean-François Bonnel, who became my jazz teacher, and encouraged me to pursue a career in jazz. I hesitated for a long time, but eventually decided I might try being a professional musician in the summer of 2010, two years after starting the jazz program in Aix-en-Provence.

RV: How long did you study in France and how has it changed or influenced you as a person, as an artist?

CMS: I was in France for about four-and-a-half years. I am not sure I would have really gotten into jazz if I had stayed in the U.S., because I wasn’t around any jazz musicians, and because, like many Americans in my generation, I had a preconception that it was clean, old, intellectual, classy and not exciting. When I moved to Aix, I was surrounded by people who loved jazz, who really cared about its history, and who saw it as an art form.

RV: I think when we’re younger, say before 21, we get lost in our favorite singers and musicians, as we absorb their sound and essence. I know Sarah Vaughan, Betty Carter and Bessie Smith are credited as your influences. Can you describe your feelings toward each one and what you feel you learned? For example, some students sing with a mentor’s tracks, exactly with their phrasing, plus learn their solos and personality inflections. What did you gain from each one of these singers?

CMS: Sarah Vaughan is the singer I listened to first. I wanted to sound exactly like her, and since I had no ambitions of being a professional jazz singer, I didn’t care about sounding original, or having my own creative vision. My mother also listened to Dinah Washington, Nancy Wilson and Billie Holiday. I was introduced to Bessie Smith by my jazz teacher when I was about 18. It took me a while to get over the sound of those old recordings and actually listen to the music. When I finally did, I spent months listening only to her, every time I had a minute to myself. She had such power and vulnerability in her singing. Her intonation and choices were extremely interesting. She had the raw quality of folk and blues music within a very “urban” style of the blues, with vaudevillian influences in the music. Her repertoire was equally fascinating: songs that did not solely focus on love, or longing, but also nostalgia, homesickness, food, sex, sin, addiction, prison, abuse, poverty, the supernatural, with oftentimes a touch of humor. Here is a non-exhaustive list of other singers that deeply influenced me: Louis Armstrong, Abbey Lincoln, Carmen McRae, Blossom Dearie, Valaida Snow, Lil Armstrong, Betty Carter (I started listening to her three years ago), Peggy Lee, Shirley Horn, Mildred Bailey, Big Bill Broonzy, Babs Gonzales, Ruth Etting, Blanche Calloway, Julie Wilson, Judy Garland, Maxine Sullivan, Ethel Waters.

RV: What a beautiful list of influences. I had quite a passion for Bessie Smith in my early years. I’ve seen a couple of your videos on YouTube of your scatting. You’re a lovely soloist. Were there specific books or programs you would recommend to young scat singers?

CMS: Thanks! I actually don’t scat very much. It’s mainly because I’m so attached to lyrics that I enjoy improvising while still singing the words. I actually almost felt it was becoming an obligation for jazz singers to scat, which is contrary to what I think scatting is about. I believe scatting has to come from a place of complete freedom. There’s almost an element of embracing the absurd in scatting. When it becomes an obligation, or a tool to prove something, it loses that element. I worked on scatting mainly by transcribing solos, both by instrumentalists and by singers I love.

RV: I’m a big fan of improvising with lyrics and I’m in total agreement with your feelings about improvising to “prove” something. That’s not musical. When I attended the 2010 Thelonious Monk Vocal Competition, it was thrilling to see you and the other finalists. Your soloing was so hip and very “Sassy.” Was that a Sarah Vaughan solo you sang? I remember the audience went crazy.

CMS: I actually don’t remember singing a Sarah Vaughan solo! It is, however, more than likely, that I was deeply influenced by her scatting at the time, and that it was noticeable.

RV: How did you prepare for the Monk Vocal Competition? What would you suggest to singers entering vocal competitions?

CMS: My mother suggested I send in an application. I had gotten rejected from another competition and lost one in the summer leading up to the Monk Competition so I entered it completely resigned and ready to have my application be rejected. Everything after that came as a surprise. I didn’t particularly prepare for the competition other than simply continuing to try and develop as a singer, as I normally would. My suggestion is to avoid approaching it like an exam one has to “cram” for. Developing as a musician should be an end in itself. It’s also important to know oneself, strengths and weaknesses, and above all, to try and remember that although it is a competition, it is mainly a performance, and musicality, emotion is key. The skills we develop as musicians are only in service of the music, of the stories we are trying to tell, of that common experience. In my opinion, singers should be in service of the song, and not the contrary. Even in the context of a competition, it is important to continually remind oneself of that.

RV: Thank you for the wisdom in your reply. Younger singers need to hear these words. We are in service of the music, absolutely. Would you recommend any singing or theory books, or computer or phone apps to singers who would like to pursue jazz singing?

CMS: My recommendation is to listen to music voraciously. I also think it is great to read books about the history of American popular music. I love Gary Giddins’ Visions of Jazz.

RV: Practice. How often do you practice technique? Do you still study voice? Do you have a specific practice method for learning new material and memorizing lyrics?

CMS: I don’t practice technique as much as I’d like to, but I try to develop my ear, by working at the piano and transcribing when I can. For me, learning new material and memorizing lyrics are done by repetition.

RV: You are a composer. If you had to list your favorite originals in a column, which would be first? I was very impressed and moved by your composition, “Look at Me.”

CMS: I would say “Left Over”

RV: I look forward to your growth as an artist and composer. Congratulations on the Grammy nomination for best vocal jazz album. What are your next goals and dreams?

CMS: I would like to continue developing as a musician, and to keep writing. I have so much to learn about music, it seems endless. I also want to teach eventually. I want to work on my piano playing, baroque singing, and visual art as well. I want to find a way, if possible, to combine my interests and do something positive with that, to help people.

Assistant: Elizabeth Tomboulian

Special thanks to advisors and editors:

Paul Wickliffe

Jeffrey LevensonSinger Cecile McLorin Salvant Talks New Album, and Her Personal Journey to Jazz

Mark Fitton The bespectacled, always stylish Miami-bred jazz phenom is on a mission to make the genre more accessible to the youth.

October 20, 2015

Essence

The bespectacled, always stylish and sometimes theatrical Cécile Mclorin Salvant is a jazz phenom with a voice that we guarantee will subdue you. The Grammy-nominated singer has a clear intention to bring jazz back to the forefront of the minds of young Black people in the US. “Jazz really honors the history of Black geniuses in America in such a beautiful way,” she tells ESSENCE. As she celebrates the release of her sophomore album, For One to Love, the Miami-bred singer spoke with ESSENCE about making the genre more accessible to the youth, her personal journey to jazz and identity.

You've got this really beautiful multinational background. How did it influence you?

My dad was born in Haiti and my mom was born in Tunisia. She is the daughter of a white French woman and a black, half-Guadeloupian half-American man. My mom traveled the world a lot. She went through Africa, South America, and the Caribbean. She just got to experience a lot of different cultures and that came through my childhood. I was really lucky to have a secondhand account of all this traveling, and really have this curiosity and openness for all these cultures and the folk element of all these different cultures.

You discovered jazz once you moved to France.

I was lucky enough to grow up in a house where we listened to all kinds of music. We listened to Haitian, hip hop, soul, classical jazz, gospel and Cuban music, to name a few. When you have access to that as a child, it just opens up your world. I do remember listening to pop and hip-hop—the music of my generation, which I love it—but I think jazz was just a part of it. I didn’t realize that jazz was an option for a career until I moved to France [for school]. That, to me, is a travesty because jazz is America’s music; it’s America’s art form, it’s Black music. Jazz is part of the reason why we were elevated above the disgusting conditions that people were in. Jazz was a way of rising above and showing that not only were we smart intellectual beings, but artists and geniuses that needed respect. Jazz brought that in a palpable way for people. Most of the people that I learned and experienced Jazz with have been with foreign White people, mostly from France. Excluding my family.

For someone who needs a point of entry into jazz, what should they start with?

You can go the route of checking out Robert Glasper’s earlier work or you can go the route of listening to Erroll Garner. Or even listening to a vocalist could be the easiest thing because it eases you in. Jazz sometimes can be really complicated and inaccessible to people because they don’t know what to start with. You can start with something that you love but if you start with something that you hate then it’s like, ‘You know what I hate jazz.’ It took me a lot of time to catch on to Jazz too.

Tell us more about your recent release, For One to Love.

There are five original compositions of mine also songs from musicals. There’s a song on the album that was originally composed by Blanche Calloway, who is Cab Calloway’s big sister. She was a huge influence on him. It’s a mix of the different things that we’ve been playing over the last couple of years.

Describe your musical style?

It’s jazz, it’s blues, we do some folk elements in there, and we do musicals. I like to sort of question different things about the way we live and about the things we think are acceptable without being too blatant about it. It’s just music that you can sit and listen to and chill and cook to, but also dance and rock out to.

Cecile Mclorin Salvant’s latest album For One to Love is out now.

Cécile McLorin Salvant

by Margo Jefferson

New York Times Magazine

How can you tell the singer from the song? On a good day, you can’t — so let’s start with the singer.

She’s Cécile McLorin Salvant, a 27-year-old with an exhilarating command of the jazz vocal tradition, which has long been dominated by women, many of them black. Salvant’s parents are French-Guadeloupean and Haitian; she grew up in Miami studying classical music, then moved to Paris and added jazz to her studies. In 2010, she won the Thelonious Monk Institute International Jazz Vocals Competition; three albums later, “For One to Love” won the jazz vocal album of the year at the 2016 Grammy Awards.

I said she’s in “command of” the jazz tradition. Better to say she’s in communion with it. I like how she listens. I like how she tests herself and learns as she performs. Salvant has a supple, well-trained voice with spot-on pitch. (No vibrato-teases; no meandering warbles passing as melisma.) Her low notes go from husky to full-bodied; her high notes float purely and cleanly. When she scats, it’s not an ego trip but a musical game, where notes and syllables get to shape-shift.

Erik Madigan Heck for The New York Times

Like many young jazz singers, she does the Great American Songbook — the Gershwins, Rodgers and Hart or Hammerstein, Sondheim, Ellington. The risk? Sounding decorous and derivative. Like some other young jazz singers, she does the black vaudeville hits of Bert Williams and Bessie Smith, even some of the exotica that female musicians once tossed out to keep their fans tantalized. Here the risk is archness: the knowing postmodern wink.

I wouldn’t be writing about Salvant if she had fallen into either trap. But mainstream success has other traps. And while it has been a long time since jazz was at the center of pop commerce, the star- (or cult-) making machinery still labors to produce familiar types. Especially for women, and even more especially for black women.

For black women in pop music, the dominant and preferred model remains the Diva. Here’s my personal theory. The black diva’s obverse is the black matriarch, that forceful mammy, maid or housekeeper, whose mythic reign lasted through a century of film and television. And yes, it’s a long way from mammy to diva, but there’s one constant. Racially and socially, this figure is considered lower and lesser. Theatrically, then — it’s the law of fantasy compensation — she must appear greater. In the old days, that meant she was literally bigger, louder, bossier. Now she’s symbolically bigger: more expansive, more intense, more outrageous.

Call the roll of the last half-century, from Patti LaBelle to Fantasia, Jennifer Holliday to Jennifer Hudson. My favorites are Aretha Franklin and Tina Turner because of their contradictions. There’s a core reserve, even sadness in Franklin, while Turner channeled her lust-goddess intensity through the dance moves of a gritty pugilist. Beyoncé and Rihanna are the grandest of contemporary divas. Their social, financial and cultural riches are vast; they command global kingdoms. They aren’t prey to traditional diva narratives of abuse or self-destruction; they turn all vulnerabilities into victories. Beyoncé is the gracious sovereign, Rihanna the cocky bad girl turned It Girl. But they share a mandate: The Black Diva must flaunt, court and rule.

Jazz divas have tended to have alter egos. Billie Holiday was a laconic wit before she was the Lady with the Gardenia; Sarah Vaughan could counter her Divine One with up-tempo Sassy. Dinah (The Queen) Washington was also a salty good-time gal. I hear their traces in Salvant’s singing, and it gives me great pleasure to watch her revise the tropes of black divadom. Don’t misunderstand — she’s not an anti-diva. I’d call her a counter-diva: the heroine as ebullient comedian.

Cécile McLorin Salvant at the Chicago Jazz Festival in 2014. Paul Natkin/Getty Images

Listen to her version of “The Trolley Song” from the 1944 hit film “Meet Me In St. Louis.” This is a song that could give any singer acute Anxiety of Influence symptoms. It began as Judy Garland’s clarion love call, then entered the jazz repertory to be taken up by Sarah Vaughan and Betty Carter. Vaughan’s version is speedy and pristinely seductive; Carter’s is a daredevil blend of swing and abstract expressionism. Salvant pays homage to all three with touches of loving parody — Garland’s girlishness, Vaughan’s love for her own silky vibrato, Carter’s near-manic tempo changes — finding her own interpretation. The train rhythms stop, start and stutter; so does Salvant’s voice. Our heroine is thinking and feeling her way, note by note, word by word, into exuberant infatuation, fashioning a romantic-comedy monologue in which the woman surprises herself with each turn of phrase and tempo.

Salvant, like all counter-divas, constructs her look with care. Hers is gamine glam: Her face is round, her hair close-cropped. She wears big, blocky white glasses — a droll trademark, like Fats Waller’s derby; a red fascinator with feathers that look like insect feelers.

The black counter-diva is now making her way into the culture at large. I hear her when the mezzo-soprano Alicia Hall Moran builds a song around nothing but a repeated “Shhhh” or arranges to fuse John Dowland’s “Flow My Tears” and Smokey Robinson’s “Cruisin’.” She’s in the mischief that snakes through Corinne Bailey Rae’s rueful feathery songs too.