SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2017

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2017

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

EARTH WIND AND FIRE

(May 20-May 26)

JACK DEJOHNETTE

(May 27-June 2)

ALBERT AYLER

(June 3-June 9)

VI REDD

(June 10-June 16)

LIGHTNIN’ HOPKINS

(June 17-June 23)

JULIAN “CANNONBALL” ADDERLEY

(June 24-June 30)

JAMES NEWTON

(July 1-July 7)

ART TATUM

(July 8-July 14)

SONNY CLARK

(July 15-July 21)

JASON MORAN

(July 22-July 28)

SONNY STITT

(July 29-August 4)

BUD POWELL

(August 5-August 11)

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/sonny-clark-mn0000036934/biography

Sonny Clark

(1931-1963)

Artist Biography by Thom Jurek

EARTH WIND AND FIRE

(May 20-May 26)

JACK DEJOHNETTE

(May 27-June 2)

ALBERT AYLER

(June 3-June 9)

VI REDD

(June 10-June 16)

LIGHTNIN’ HOPKINS

(June 17-June 23)

JULIAN “CANNONBALL” ADDERLEY

(June 24-June 30)

JAMES NEWTON

(July 1-July 7)

ART TATUM

(July 8-July 14)

SONNY CLARK

(July 15-July 21)

JASON MORAN

(July 22-July 28)

SONNY STITT

(July 29-August 4)

BUD POWELL

(August 5-August 11)

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/sonny-clark-mn0000036934/biography

Sonny Clark

(1931-1963)

Artist Biography by Thom Jurek

Like Fats Navarro and Charlie Parker before him, Sonny Clark's life was short but it burned with musical intensity. Influenced deeply by Bud Powell, Clark

nonetheless developed an intricate and hard-swinging harmonic

sensibility that was full of nuance and detail. Regarded as the

quintessential hard bop pianist, Clark

never got his due before he passed away in 1963 at the age of 31,

despite the fact that it can be argued that he never played a bad

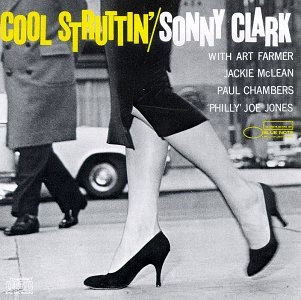

recording date either as a sideman or as a leader. Known mainly for

seven records on the Blue Note label with a host of players including

such luminaries as John Coltrane, Art Farmer, Donald Byrd, Jackie McLean, Hank Mobley, Art Taylor, Paul Chambers, Wilbur Ware, Philly Joe Jones, and others, Clark actually made his recording debut with Teddy Charles and Wardell Gray, but left soon after to join Buddy DeFranco. His work with the great clarinetist has been documented in full in a Mosaic set that is now sadly out of print. Clark also backed Dinah Washington, Serge Chaloff, and Sonny Criss before assuming his role as a leader in 1957. Clark's classic is regarded as Cool Struttin' but each date he led on Blue Note qualifies as a classic, including his final date, Sonny's Crib with John Coltrane. And though commercial success always eluded him, he was in demand as a sideman and played dozens of Alfred Lion-produced dates, including Tina Brooks' Minor Move. Luckily, Clark's contribution is well documented by Alfred Lion; he has achieved far more critical, musical, and popular acclaim than he ever did in life.

https://sites.google.com/site/pittsburghmusichistory/pittsburgh-music-story/jazz/modern-era/sonny-clark

Sonny Clark was an extraordinary modern jazz pianist and

composer noted for his nine classic Blue Note albums. His most

acclaimed albums "Cool Struttin" and "Leapin and Lopin"

is rated by some critics among among the best jazz recordings of all

time. Appearing on Clark’s recordings were jazz legends John Coltrane,

Art Farmer, Donald Byrd, Jackie McLean, Hank Mobley, Art Taylor, and

Pittsburgh’s Paul Chambers. Clark is called the “quintessential hard

bop pianist”. From 1957 through 1962 he was the resident pianist for

Blue Note recording sessions. He appeared on the recordings of hard pop

players Kenny Burrell, Donald Byrd, Paul Chambers, John Coltrane, Dexter

Gordon, Art Farmer, Curtis Fuller, Grant Green, Philly Joe Jones, Clifford

Jordan, Jackie McLean, Hank Mobley, Art Taylor, and Wilbur Ware along with

recording with Charles Mingus, Sonny Rollins, Billie Holiday, Stanley

Turrentine, and Lee Morgan. He began his career touring with with

saxophonist Wardell Gray, clarinetist Buddy DeFranco, and Dinah

Washington before he settled in New York to become a Blue Note artist.

“He has all of the chops, inventiveness, and speed to burn

that made him one of the most impressive pianists of the hard bop era.” -

Michael G. Nastos Allmusic.com

Sonny Clark’s playing style and original compositions were

influenced by Art Tatum, Bud Powell, and Horace Sliver. He had is own

distinct touch and tone that colored his long flowing relaxed melodic lines

and lively driving rhythmic solos. His music combined minor blues and

hard swing. Pianist Bill Evans cites Sonny Clark as a major influence.

Clark's music has been immensely popular in Japan. Since

1991 his “Cool Struttin” CD has sold 179,000 copies out selling John

Contrane’s “Blue Train” album.

Sonny Clark was born Conrad Yeatis Clark on July 21, 1931 in the

small coal mining town Herminie No. 2 about twenty five miles southeast of

Pittsburgh. His parents grew up and met in the rural countryside of

Stone Mountain Georgia before migrating to Western Pennsylvania. They

moved first to Aliquippa where his father worked in the coke yards of Jones

& Laughlin Steel. Driven from Aliquippa by KKK activity the Clarks moved

to more rural Herminie mining town to raise their family. Sonny’s coal

miner father, Emory Clark, died of black lung disease on August 2 of

1931. The youngest of eight children Sonny was raised by his mother

Ruth Shepherd Clark and his older siblings. Upon Emory’s death the Clark

family moved from their mining company owned house to the Redwood Inn hotel

in Herminie. Owned by African American John Redwood the hotel held

popular weekend jazz dances attended by African Americans who came from a 50

mile radius to attend Sony began playing piano at age four while

living at the Redwood Inn. He studied piano with a private teacher and

was also taught by his older brother George. During elementary school

at age 6 Sonny began playing piano professionally at the hotel. Sonny

also appeared on a radio amateur hour show at age 6 performing a

boogie-woogie. Hearing that audiences marveled at Sonny’s performances

the Pittsburgh Courier published an article about the young

pianist.

Hearing the music of Art Tatum, Fats Waller, Cout Basie, and

Duke Ellington on the radio, he fell in love with jazz. Attending high

school in Jeanette he played bass and vibes with his high school band and

also performed as a piano soloist. He performed professionally around

Pittsburgh while still in school. At age 15 Sonny appeared on the bill

of the historic “Night of the Stars” Concert held at the Syria Mosque to

celebrate the music of Pittsburgh’s jazz superstars. Presented by the

Frog Club and the Pittsburgh Courier on August 7, 1946 the show featured an

all star cast of legendary Pittsburgh pianists Earl Hines, Mary Lou Williams,

Billy Strayhorn, and Erroll Garner and jazz greats Billy Eckstein, Roy

Eldridge, Maxine Sullivan, Ray Brown, Louis Deppe and more.

In 1951, when Sonny was 19, his older brother, also a pianist,

took him on a trip to visit their aunt in Los Angeles. Sonny decided to

stay in California and found work performing with Wardell Grey and Vido

Musso. Working in California Sonny played with the key figures in the

West Coast jazz movement including Stan Getz, Art Farmer. Wardell Grey, Anita

O’Day, and Shelly Manne. His was one of the few African Americans

performing West Coast jazz. Sonny made with recording debut in

1953 with saxophonist Wardell Grey on the Verve label. He joined

Oscar Pettiford’s band and moved to San Francisco. In San Fransisco he

joined Buddy DeFranco’s band. Sonny performed with Buddy DeFranco for

two and a half years beginning with a tour of Europe and the U.S in

1954. Sonny recorded his first album as a trio leader in 1955.

Titled “Oakland” it featured bassist Jerry Good and drummer

Al Randall and was recorded at the Mocambo Club in Oakland in January of

1955, Sonny joined the Lighthouse All Stars in Hermosa Beach playing

with them throughout 1956. Wanting to travel back East and to

visit his family in Pittsburgh on the way, Sonny took a job touring with

Dinah Washington in February of 1957.

Settling in New York in 1957 he worked dates with West Coast

jazz artists including two weeks at Birdland with Stan Getz and a weekend

with Anita O'Day. Switching from West Coast Jazz to Hard Bop Sonny

quickly became a requested sideman playing with hardpop players John

Coltrane, Dextor Gorden, Kenny Burrell, and more. He began recording on the

prestigious Blue Note label at age 26. Sonny recorded 29 Blue Note sessions

as a band leader and a sideman. He made 17 recordings in 1957 including

five album recordings for Blue Note. His first recording as a band

leader was “Dial S for Sonny” released in 1957. His second release in 1957

was “Sonny‘s Crib” that featured a band comprised of John Coltrane and Paul

Chambers. The album Sonny Clark Trio with Paul Chambers Philly Joe Jones was

also released in 1957. The classic “Cool Struttin’ album and the

“Standards” albums were released in 1958. Critic Thom Jurek of Allmusic.com calls

the title tract “Cool Struttin: “one of the preeminent swinging medium blues

pieces in jazz history.” The album “My Conception” featuring tenor

saxophonist Hank Mobley was released in 1959. The “Sonny Clark Trio”

album with George Duvivier and Max Roach was released in 1960. His last

album “Leapin' and Lopin” released in 1961 featuring four song composed by

Clark includes the classics tracts “Vodoo” and “Something Special”.

Writer Michael G. Nastos of Allmusic.com calls “Leapin and Lopin” one

of the definitive recording for all time in the mainstream jazz idiom.

In 1962 Sonny performed with Dexter Gordon on two of his classic

Blue Note albums “Go” and “A Swinging Affair”. He was Gorden’s

favorite piano accompanist. Sonny also recorded in 1962 the albums Blue

and Sentimental and Easy Living with Ike Quebec, Born to be Blue and Nigeria

with Grant Green, the Jackie McLean Quintet and Tippin' the Scales with

Jackie McLean, and Jubliee Shout with Stanley Turrentine.

Sonny died of a heart attack on Sunday, January 13, 1963 at the

age of 31. He had been in poor health due to his heroin and alcohol

addictions. Sonny played his last gigs two nights before his death on

January 11 and 12 at Junior’s Bar on at the Alvin Hotel on Fifty-second and

Broadway. Sonny’s friend, jazz patron Baroness Pannonica de

Koenigswarter, called Clark’s older sister in Pittsburgh to tell her of her

brother’ passing. The baroness paid to transport Sonny’s body back to

Pittsburgh and paid for his funeral. Sonny’s grave lies in the

Greenwood Cemetery in Sharpsburg, PA.

|

References:

Cookin': hard bop and soul jazz, 1954-65 Kenny Mathieson

The Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz

By Leonard Feather, Ira Gitler

Sonny Clark Trio liner notes by Lenard Feather

Sonny Clark -Lee Bloom & Mike Waters

http://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/sonny-clark-at-eighty

SONNY CLARK

Conrad Yeatis “Sonny”

Clark was an American jazz pianist who mainly worked in the hard bop idiom.

Clark was born and

raised in Herminie, Pennsylvania, a coal mining town southeast of Pittsburgh.

At age 12, he moved to Pittsburgh. When visiting an aunt in California at age

20, Clark decided to stay and began working with saxophonist Wardell Gray.

Clark went to San Francisco with Oscar Pettiford and after a couple months, was

working with clarinetist Buddy DeFranco in 1953. Clark toured the U.S. and

Europe with DeFranco until January 1956, when he joined The Lighthouse

All-Stars, led by bassist Howard Rumsey.

Wishing to return to

the east coast, Clark served as accompanist for singer Dinah Washington in

February 1957 in order to relocate to New York City. In New York, Clark was

often requested as a sideman by many musicians, partly because of his rhythmic

comping. He frequently recorded for Blue Note Records, playing as a sideman

with many hard bop players, including Kenny Burrell, Donald Byrd, Paul

Chambers, John Coltrane, Dexter Gordon, Art Farmer, Curtis Fuller, Grant Green,

Philly Joe Jones, Clifford Jordan, Jackie McLean, Hank Mobley, Art Taylor, and

Wilbur Ware. He also recorded sessions with Charles Mingus, Sonny Rollins,

Billie Holiday, Stanley Turrentine, and Lee Morgan.

As a band leader, Clark recorded albums “Dial “S” for Sonny” (1957), “Sonny's Crib” (1957), Sonny Clark Trio (1957), with Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones, and Cool Struttin' (1958). Sonny Clark Trio, with George Duvivier and Max Roach was released in 1960.

Clark died of a heart

attack in New York City, although commentators attribute the early death to

Clark's drug and alcohol abuse.

Close friend and

fellow jazz pianist Bill Evans dedicated the composition “NYC's No Lark” (an

anagram of “Sonny Clark”) to him after his death, included on Evans'

Conversations with Myself (1963). John Zorn, Wayne Horvitz, Ray Drummond, and

Bobby Previte recorded an album of Clark's compositions, Voodoo (1985), as The

Sonny Clark Memorial Quartet. Zorn also recorded several of Clark's

compositions with Bill Frisell and George Lewis on News for Lulu (1988) and

More News for Lulu (1992).

Sonny Clark

Piano

July 21, 1931 -- January 13, 1963

"Sonny Clark died in 1963 at the age of thirty-one, a figure who had yet to gain his due as a musician. Recently his work, long neglected, has experienced a much deserved revival."

--Ted Gioia

Introduced to Blue Note aficianados with his first band date on Dial

"S" For Sonny, Sonny Clark featured a front line composed

of Art Farmer, Curtis Fuller and Hank Mobley. On his impressive

follow-up session (Sonny's Crib) the horns consisted of Donald Byrd, Curtis Fuller and John Coltrane. Before we

listened together to the rewarding results of his initial trio date, Sonny took

a few moments to clarify and amplify his biography.

"Actually, I wasn't born in Pittsburgh," he said. "I was born

in a little coal mining town, about sixteen miles southeast of Pittsburgh,

called herminie, Pa.--population about 800. I was raised there till I was

twelve, then lived in Pittsburgh until I was nineteen, just turning twenty;

then an older brother, who plays piano, took me out to the coast to visit an

aunt.

"Originally I only intended to stay a couple of months. I worked with Wardell Gray and all the

fellows around the coast. Then Oscar Pettiford came to town and we got a band

and went to San Francisco.

"I worked in San Francisco a couple of months. Buddy DeFranco was in

town, with Art Blakey, and Kenny Drew on piano and Gene

Wright on bass. Then Blakey and Kenny Drew left him and I joined, along with

Wesley Landers, a drummer from Chicago. He only stayed a couple of weeks, then

Bobby White came in--this was late in 1953, and as you know, soon after that,

in January and February of '54, we toured Europe in your show, Jazz Club,

U.S.A."

"That's where the gaps begin in my notes," I said. "It's been

four years since we all came back from europe and I can't account for

everything that happened to you in that time. Perhaps you can fill me in."

"Well," said Sonny, "I stayed with Buddy quite a long while

after we went back to the coast. We made another tour, in the middle west, and

we went to Honolulu. Altogether I was with Buddy about two-and-a-half years.

Then in January, 1956, I joined Howard

Rumsey's Lighthouse All-Stars in Hermosa Beach, California and spent the

whole year of 1956 there."

"How did you enjoy that?"

"The climate is crazy. I'm going to be truthful, though: I did have

sort of a hard time trying to be comfortable in my playing. The fellows out on

the west coast have a different sort of feeling, a different approach to jazz.

They swing in their own way. But Stan Levey, Frank Rosolino and Conte

Candoli were a very big help; of course they all worked back in the east for a

long time during the early part of their careers, and I think they have more of

the feeling of the eastern vein than you usually find in the musicians out

west. The eastern musicians play with so much fire and passion.

"We did concerts and a lot of record dates, and I could have stayed as

long as I liked, but I wanted to see the east again, and also wanted to see my

people who still live in Pittsburgh--a brother and two sisters--and a sister in

Dayton. I got to see all of them by joining Dinah Washington in February, 1957

and going along with her as accompanist more or less for the ride.

"Since settling down in New York, I've been doing mostly recording. I

played a couple of weeks at Birdland with Stan Getz, and a weekend with Anita

O'Day. What I want to do eventually, of course, is have my own trio or quartet

and play in the kind of setting I like best--the kind of music you hear in this

album."

--LEONARD FEATHER, from the liner

notes,

Sonny Clark Trio, Blue Note.

A selected discography of Sonny Clark albums.

- Dial "S" For Sonny, 1957, Blue Note.

- Sonny's Crib, 1957, Blue Note.

- Sonny Clark Trio, 1957, Blue Note.

- My Conception, 1957-59, Blue Note.

- Cool Struttin', 1958, Blue Note.

- High Fidelity, 1960, Bainbridge.

- Leapin' and Lopin', 1961, Blue Note.

http://sonnyclark.jazzgiants.net/biography/

Conrad Yeatis “Sonny” Clark was born on July 21, 1931 in Herminie, Pennsylvannia and passed away on January 13, 1963 in New York City January 13, 1963 in New York City.

Clark was born and raised in Herminie, Pennsylvania, a coal mining town southeast of Pittsburgh. At age 12, he moved to Pittsburgh. When visiting an aunt in California at age 20, Clark decided to stay and began working with saxophonist Wardell Gray. Clark went to San Francisco with Oscar Pettiford and after a couple months, was working with clarinetist Buddy DeFranco in 1953. Clark toured the U.S. and Europe with DeFranco until January 1956, when he joined The Lighthouse All-Stars, led by bassist Howard Rumsey.

Wishing to return to the east coast, Clark served as accompanist for singer Dinah Washington in February 1957 in order to relocate to New York City. In New York, Clark was often requested as a sideman by many musicians, partly because of his rhythmic comping. He frequently recorded for Blue Note Records, playing as a sideman with many hard bop players, including Kenny Burrell, Donald Byrd, Paul Chambers, John Coltrane, Dexter Gordon, Art Farmer, Curtis Fuller, Grant Green, Philly Joe Jones, Clifford Jordan, Jackie McLean, Hank Mobley, Art Taylor, and Wilbur Ware. He also recorded sessions with Charles Mingus, Sonny Rollins, Billie Holiday, Stanley Turrentine, and Lee Morgan.

As a band leader, Clark recorded albums “Dial “S” for Sonny” (1957), “Sonny’s Crib” (1957), Sonny Clark Trio (1957), with Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones, and Cool Struttin’ (1958). Sonny Clark Trio, with George Duvivier and Max Roach was released in 1960. Clark died of a heart attack in New York City in 1963.

Clark’s albums are generally upbeat affairs. His solos crackle with electricity, while he lends solid support to the horns (Clark stated in interviews that he enjoyed comping almost as much as he enjoyed soloing). On only a few occasions did Clark record in a trio setting, the most notable of which was the Sonny Clark Trio album.

Biography

Conrad Yeatis “Sonny” Clark was born on July 21, 1931 in Herminie, Pennsylvannia and passed away on January 13, 1963 in New York City January 13, 1963 in New York City.

Clark was born and raised in Herminie, Pennsylvania, a coal mining town southeast of Pittsburgh. At age 12, he moved to Pittsburgh. When visiting an aunt in California at age 20, Clark decided to stay and began working with saxophonist Wardell Gray. Clark went to San Francisco with Oscar Pettiford and after a couple months, was working with clarinetist Buddy DeFranco in 1953. Clark toured the U.S. and Europe with DeFranco until January 1956, when he joined The Lighthouse All-Stars, led by bassist Howard Rumsey.

Wishing to return to the east coast, Clark served as accompanist for singer Dinah Washington in February 1957 in order to relocate to New York City. In New York, Clark was often requested as a sideman by many musicians, partly because of his rhythmic comping. He frequently recorded for Blue Note Records, playing as a sideman with many hard bop players, including Kenny Burrell, Donald Byrd, Paul Chambers, John Coltrane, Dexter Gordon, Art Farmer, Curtis Fuller, Grant Green, Philly Joe Jones, Clifford Jordan, Jackie McLean, Hank Mobley, Art Taylor, and Wilbur Ware. He also recorded sessions with Charles Mingus, Sonny Rollins, Billie Holiday, Stanley Turrentine, and Lee Morgan.

As a band leader, Clark recorded albums “Dial “S” for Sonny” (1957), “Sonny’s Crib” (1957), Sonny Clark Trio (1957), with Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones, and Cool Struttin’ (1958). Sonny Clark Trio, with George Duvivier and Max Roach was released in 1960. Clark died of a heart attack in New York City in 1963.

Clark’s albums are generally upbeat affairs. His solos crackle with electricity, while he lends solid support to the horns (Clark stated in interviews that he enjoyed comping almost as much as he enjoyed soloing). On only a few occasions did Clark record in a trio setting, the most notable of which was the Sonny Clark Trio album.

Close friend and fellow jazz pianist Bill Evans dedicated the composition

“NYC’s No Lark” (an anagram of “Sonny Clark”) to him after his death, included

on Evans’ Conversations with Myself

(1963).

https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2011/01/13/sonny-clark/

Forty-eight years ago today, the pianist Conrad Yeatis “Sonny” Clark died of

a heroin overdose in a shooting gallery somewhere in New York City. He was

thirty-one. The previous two nights—January 11 and 12, 1963—he had played piano

at Junior’s Bar on the ground floor of the Alvin Hotel on the northwest corner

of Fifty-second and Broadway. On Sunday, January 13, the temperature reached

thirty-eight degrees in Central Park.

The next thing we know with certainty is that Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, a noted jazz patron, called Clark’s older sister in Pittsburgh to inform her of her brother’s death. Nica, as the baroness was known, said she would pay to have the body transported to his hometown and that she’d pay for a proper funeral.

What is not known, however, is if the body in the New York City morgue with Clark’s name on it was his. Witnesses in both New York and Pittsburgh (after the body arrived there) believed it wasn’t; they thought it didn’t look like Sonny. Some suspected a conspiracy with the drug underground with which Clark was entangled, but, as African Americans in a white system, they were reticent to discuss the matter. It was probably a simple case of carelessness at the morgue, something not uncommon with “street” deaths at the time, particularly when the corpses were African American. Today, there’s a gravestone with Clark’s name on it in the rural hills outside Pittsburgh, where a body shipped from New York was buried in mid-January of that year. How painful it must have been to stay silent and let a funeral proceed, not knowing for sure where Sonny’s body was. His may be one of the thousands of unidentified ones buried in potter’s field on New York’s Hart Island, where Sonny himself dug graves years earlier, while incarcerated at Riker’s Island on drug charges.

Clark’s right fingers on piano keys created some of my favorite sounds in all of recorded jazz. I noticed these sounds for the first time one afternoon in a coffee shop in Raleigh, North Carolina, in the winter of 1999. I walked in, a freelance writer seeking refuge from cabin fever at home. I was working on a magazine article about a Sixth Avenue New York City loft building that was a late night haunt of jazz musicians forty years earlier. Over the next hour, I became transfixed by the relaxed, swinging blues floating out of the house stereo system. The multipierced barista showed me the two-CD case, Grant Green: The Complete Quartets with Sonny Clark. Green was a guitarist from St. Louis with a singing, single-note style that blended beautifully with Clark’s effortless, hypnotic right-hand piano runs. “This is the epitome of cool,” she said. True. It was also smokin’ hot, and I heard a country twang in it. The nineteen tracks were recorded in December 1961 and January 1962 by the Blue Note label, but they weren’t released until many years later, after both Green and Clark were dead.

Clark was born on July 21, 1931, in Herminie No. 2, Pennsylvania, a coal patch a few miles from the bigger company town of Herminie (No. 2 refers to the second mine shaft of the Ocean Coal Company) and about twenty-five miles east of Pittsburgh. On August 2 of that year, his father, Emory Clark, a miner, died of “a lingering illness of tuberculosis,” as indicated in a brief obituary in a local paper. The family called it “black lung,” a casualty of the mine work. Sonny was the youngest of eight kids and was raised by his mother and his older siblings. The 1930 census shows their home surrounded by families from Italy, Poland, Austria, and Russia as well as African Americans from Georgia and Tennessee. This extraordinary mix of people existed in a company village of only a few hundred people. The town had a school, a few places of worship (including a black church), a beer garden, and a company store. There was also a black-owned hotel that hosted some of the most popular weekend dances in the region for African Americans. A small boy (and a small man, too: five-foot-five, one hundred thirty pounds full grown), Sonny began playing piano in the hotel while in elementary school. People marveled at his playing, and he was written up in the famous black paper, the Pittsburgh Courier. His oldest brother, Emory, carried Sonny home on his shoulders after he won a talent show. They skipped rocks across ponds and learned how to make slingshots from roadside weeds and brush. The family’s home was the countryside; Sonny’s parents had met as kids in the country, living across a dirt road from each other in Stone Mountain, Georgia.

https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2011/01/13/sonny-clark/

Sonny Clark

by Sam Stephenson

January 13, 2011

The Paris Review

Notes from a Biographer

Clark

seated at piano backstage at Syria Mosque for Night of Stars event, 1946.

Courtesy Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; Heinz Family Fund; © 2004 Carnegie

Museum of Art, Charles “Teenie” Harris Archive.

The next thing we know with certainty is that Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, a noted jazz patron, called Clark’s older sister in Pittsburgh to inform her of her brother’s death. Nica, as the baroness was known, said she would pay to have the body transported to his hometown and that she’d pay for a proper funeral.

What is not known, however, is if the body in the New York City morgue with Clark’s name on it was his. Witnesses in both New York and Pittsburgh (after the body arrived there) believed it wasn’t; they thought it didn’t look like Sonny. Some suspected a conspiracy with the drug underground with which Clark was entangled, but, as African Americans in a white system, they were reticent to discuss the matter. It was probably a simple case of carelessness at the morgue, something not uncommon with “street” deaths at the time, particularly when the corpses were African American. Today, there’s a gravestone with Clark’s name on it in the rural hills outside Pittsburgh, where a body shipped from New York was buried in mid-January of that year. How painful it must have been to stay silent and let a funeral proceed, not knowing for sure where Sonny’s body was. His may be one of the thousands of unidentified ones buried in potter’s field on New York’s Hart Island, where Sonny himself dug graves years earlier, while incarcerated at Riker’s Island on drug charges.

Clark’s right fingers on piano keys created some of my favorite sounds in all of recorded jazz. I noticed these sounds for the first time one afternoon in a coffee shop in Raleigh, North Carolina, in the winter of 1999. I walked in, a freelance writer seeking refuge from cabin fever at home. I was working on a magazine article about a Sixth Avenue New York City loft building that was a late night haunt of jazz musicians forty years earlier. Over the next hour, I became transfixed by the relaxed, swinging blues floating out of the house stereo system. The multipierced barista showed me the two-CD case, Grant Green: The Complete Quartets with Sonny Clark. Green was a guitarist from St. Louis with a singing, single-note style that blended beautifully with Clark’s effortless, hypnotic right-hand piano runs. “This is the epitome of cool,” she said. True. It was also smokin’ hot, and I heard a country twang in it. The nineteen tracks were recorded in December 1961 and January 1962 by the Blue Note label, but they weren’t released until many years later, after both Green and Clark were dead.

Clark was born on July 21, 1931, in Herminie No. 2, Pennsylvania, a coal patch a few miles from the bigger company town of Herminie (No. 2 refers to the second mine shaft of the Ocean Coal Company) and about twenty-five miles east of Pittsburgh. On August 2 of that year, his father, Emory Clark, a miner, died of “a lingering illness of tuberculosis,” as indicated in a brief obituary in a local paper. The family called it “black lung,” a casualty of the mine work. Sonny was the youngest of eight kids and was raised by his mother and his older siblings. The 1930 census shows their home surrounded by families from Italy, Poland, Austria, and Russia as well as African Americans from Georgia and Tennessee. This extraordinary mix of people existed in a company village of only a few hundred people. The town had a school, a few places of worship (including a black church), a beer garden, and a company store. There was also a black-owned hotel that hosted some of the most popular weekend dances in the region for African Americans. A small boy (and a small man, too: five-foot-five, one hundred thirty pounds full grown), Sonny began playing piano in the hotel while in elementary school. People marveled at his playing, and he was written up in the famous black paper, the Pittsburgh Courier. His oldest brother, Emory, carried Sonny home on his shoulders after he won a talent show. They skipped rocks across ponds and learned how to make slingshots from roadside weeds and brush. The family’s home was the countryside; Sonny’s parents had met as kids in the country, living across a dirt road from each other in Stone Mountain, Georgia.

My wife, Laurie Cochenour, grew up in Elizabeth Township, about seven miles

from Herminie No. 2. For the past decade, I’ve done a bit of research on Sonny

Clark each time we visit her family, and Sonny’s two surviving sisters have

been helping me. I’ve driven through Herminie No. 2 and found old-timers, black

and white, who grew up with him. One of them gave me their second-grade class

picture from 1937–38. Sonny is the only black kid in the class. I now have an

accordion file full of material. After my biography of W. Eugene Smith, a book

on Sonny may follow.

My interest in Clark grew when I heard him on Smith’s tapes from the Sixth

Avenue loft scene. In the wee morning hours of September 25, 1961, while

packing to leave for Japan from Idlewild Airport later that day, Smith turned

on his tape recorder and let it roll until dawn. He had live microphones in the

hallway and stairwell. He captured Sonny and his friend, the saxophonist Lin

Halliday, arriving at the building and walking up the bare wood stairs with

Lin’s seventeen-year-old girlfriend, Virginia “Gin” McEwan. Sonny and Lin had

been playing at the White Whale in the East Village earlier in the evening with

bassist Butch Warren and drummer Billy Higgins. Sonny sticks his head in

Smith’s door and says to the notorious pack rat, “You’ve got a lot of shit in

here.” Smith responds, “I’ve been shitting for a long time.” They laugh. Sonny

and Lin then go into the hallway bathroom on the fourth floor and shoot heroin.

Smith’s tapes catch Sonny moaning to near unconsciousness. Lin grows anxious

and then frightened. He sings to Sonny to try to keep him awake. Earlier that

summer, Gin had saved Sonny’s life with amateur CPR after an overdose. But now,

when Lin calls out for her—“Gin? Gin? Gin?”—she does not respond; she had

already moved somewhere else in the building. The tension in the harrowing scene

mounts. How miraculous (and perhaps questionable) that such a moment is caught

on plastic reel-to-reel tape, to be heard in real time a half-century later in

a digitally transferred file.

Meanwhile, in his room packing for Japan, Smith plays vinyl records of Edna St. Vincent Millay reading her poetry and actress Julie Harris reading Emily Dickinson. (Smith owned the entire Caedmon Records inventory). Over time, Sonny’s dose wears off, and he and Lin shuffle down to the automat for cheeseburgers and milkshakes. For money, they tote several dozen bottles that Smith gave them to redeem for deposits at the grocery store. It’s not clear if Smith ever saw Sonny Clark again. He spent a year in Japan, and Sonny went on to record the great tracks with Grant Green, as well as several other classic Blue Note albums, before dying sixteen months later.

Read the second part of Stephenson’s look back at Sonny Clark here.

See also: “Dorrie Glenn Woodson” and “W. Eugene Smith.”

Sam Stephenson is the author of The Jazz Loft Project. He is currently at work on a biography of W. Eugene Smith for Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Check back soon for more of Stephenson’s dispatches.

Miss

Allebrand's first-grade class, Washington School, 1937–38, Herminie No. 2, PA.

Photograph courtesy of Betty Smith Dopkowski, who is standing to Sonny Clark's

right.

Meanwhile, in his room packing for Japan, Smith plays vinyl records of Edna St. Vincent Millay reading her poetry and actress Julie Harris reading Emily Dickinson. (Smith owned the entire Caedmon Records inventory). Over time, Sonny’s dose wears off, and he and Lin shuffle down to the automat for cheeseburgers and milkshakes. For money, they tote several dozen bottles that Smith gave them to redeem for deposits at the grocery store. It’s not clear if Smith ever saw Sonny Clark again. He spent a year in Japan, and Sonny went on to record the great tracks with Grant Green, as well as several other classic Blue Note albums, before dying sixteen months later.

Read the second part of Stephenson’s look back at Sonny Clark here.

See also: “Dorrie Glenn Woodson” and “W. Eugene Smith.”

Sam Stephenson is the author of The Jazz Loft Project. He is currently at work on a biography of W. Eugene Smith for Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Check back soon for more of Stephenson’s dispatches.

Sonny Clark, Part 2

by Sam Stephenson

Notes from a Biographer

Sonny Clark, ca. 1961. Photograph by Francis Wolff. (c)

Mosaic Images (www.mosaicrecords.com)

On October 26, 1961, Sonny Clark reported to Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, for a recording session led by alto saxophonist Jackie McLean. Clark brought with him a new composition he called “Five Will Get You Ten.” He was an effective composer, and his tunes were welcome at most sessions. However, this one he’d stolen from Thelonious Monk. He had probably seen the sheet music or heard Monk working out the tune on the piano at the Weehawken, New Jersey, home of the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, who routinely made her home a rest stop and clubhouse for jazz musicians.

In the last eighteen months of Clark’s life, he would climb to daylight for brief periods, breath clean air, play some beautiful music, and then sink to lower and lower depths. In the August 1962 issue of the invaluable, idiosyncratic Canadian jazz magazine, Coda, there was this report from New York by Fred Norsworthy:

One of the saddest sights these days is the terrible condition of one of the nation’s foremost, and certainly original pianists. Having been around for many years he came into his own in 1959 and no one deserved it more than he. I feel that something should be done about drug addiction before we lose many more artists. I saw him several times in the past three months and was shocked to see one of our jazz greats in such pitiful shape. Unfortunately, the album dates that he keeps getting only help his addiction get worse instead of better. Whether or not he licks this problem at this stage of the game remains to be seen. In some cases people refuse help and the loss of a close friend was no help either. If anything he took a turn for the worse and disappeared for 3 weeks. However right now should he die it will at least be better than living a slow death with no relief in sight.

The pianist is almost certainly Sonny Clark. That same month, he cut two classic Blue Note albums under the leadership of saxophonist Dexter Gordon, Go and A Swinging Affair. When Clark died five months later, Gordon remembered these sessions in a letter to Blue Note impresarios Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff: Clark had “almost totally given up” on his life, Gordon wrote. Yet judging from the surviving albums, he still cooked on piano. Several of Clark’s solos are top notch, but in this rhythm section with Butch Warren on bass and Billy Higgins on drums, he conducts a clinic on how to play sensitive, sparkling piano accompaniment behind a soloing saxophonist, in this case the atmospheric Gordon. Clark didn’t appear to give up on anything musically. Many years later Gordon remembered Go as among his career favorites.

As a potential biographer of Sonny Clark, I have to be careful of the notion of the damaged, tragic artist having an aesthetic advantage (I have to be careful of this for Eugene Smith, too). He grew up not far from where my wife did, near the Allegheny hills where her ancestors migrated for work, same as Sonny’s parents. I’m drawn to these hills like a second home; the place haunts me. How did a black man come from here and learn such an extraordinary facility on piano? Why did he become such a stereotypical jazz junkie? Why is the wrong body apparently buried underneath his gravestone in these hills?

Aesthetically, the two records are very much of the same time and place. Both feature front lines of saxophone, trumpet, and piano backed by Paul Chambers on bass and Philly Joe Jones on drums, and they were recorded by the same label in the same studio, only four months apart. The real distinction is that Blue Train is an entry-level recording by a saxophonist who went on to become one of the most feverish and supreme giants of American music, while Cool Struttin’ could be described by a cynic as a fine but routine, almost potluck jam session typical of the period.

I’m not yet sure how to explain the unusual prestige of Cool Struttin’ in Japan. In February, I embark on a five-week trip to research W. Eugene Smith’s work there in the 1960s and ’70s along with his World War II combat photography in Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and elsewhere in the Pacific. While there, I’ll spend some time trying to figure out the reasons for Clark’s popularity. Perhaps it’s just a fluke. I believe there’s more to it. My feeling is that the Japanese audience may have a special ear for the beauty of Clark’s minor blues. This occurred to me when I was listening to one of Smith’s loft tapes. On May 8, 1960, Smith made an audio recording of Edward R. Murrow’s CBS program, Small World, from Channel 2 in New York City. The episode featured Yukio Mishima and Tennessee Williams in a discussion of Japanese cinema.

MISHIMA

I think a characteristic of Japanese character is just this mixture of very brutal things and elegance. It’s a very strange mixture.

WILLIAMS

I think that you in Japan are close to us in the Southern states of the United States.

MISHIMA

I think so.

WILLIAMS

A kind of beauty and grace. So that although it is horror, it is not just sheer horror, it has also the mystery of life, which is an elegant thing.

This “very strange mixture” of the brutal and the elegant may describe what Japanese jazz fans hear coming out of Clark’s piano. His parents came from rural, Jim Crow Georgia and moved to Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh, so Sonny’s father could work in the coke yards of Jones & Laughlin Steel. They were chased away by KKK activity there and ended up in a company coal-mining village that reminded them of their rural Southern home near a rock quarry. Mr. Clark died of black-lung disease two weeks after Sonny was born. Mrs. Clark died of breast cancer when he was twenty-two. The family dispersed; Sonny followed a brother to Los Angeles, where it didn’t take him long to rise to the top of the jazz scene, a topsy-turvy milieu drizzled with narcotics.

No jazz pianist was more drenched in minor blues than Clark. Yet he blended his blues with a buoyant, ventilated swing. And to this day, nobody sounds like Sonny Clark.

Click here to read part 1 of Stephenson on Sonny Clark.

Sam Stephenson is the author of The Jazz Loft Project. He is currently at work on a biography of W. Eugene Smith for Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Check back soon for more of Stephenson’s dispatches.

Sonny Clark-- 'Cool Struttin'--Full Album:

Artist: Sonny Clark Album: Cool Struttin'

Label: Blue Note

1958

Tracks:

01 Cool Struttin'

00:00 02 Blue Minor

09:22 03 Sippin'

Sonny Clark--'Leapin' and Lopin'--Full Album:

Sonny Clark Trio with Max Roach &

George Duvivier (Full Album):

Sonny's Crib--Full Album:

Sonny's Mood--Full Album:

Sonny Clark--'Bebop':

Sonny Clark--"Voodoo":

Sonny Clark--'Bebop'--Full Album:

Sonny Clark Jazzcloud:

Sonny Clark--'Dial 'S' for Sonny--Full album:

Sonny Clark

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Sonny Clark | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Conrad Yeatis Clark |

| Born | July 21, 1931 Herminie, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Died | January 13, 1963 (aged 31) New York City, New York, United States |

| Genres | Jazz, hard bop |

| Occupation(s) | Musician |

| Instruments | Piano |

| Years active | 1953–1962 |

| Labels | Blue Note |

| Associated acts | Curtis Fuller, Jackie McLean, Lee Morgan, Hank Mobley, Grant Green, Dexter Gordon, Paul Chambers, Philly Joe Jones, Serge Chaloff, Max Roach, George Duvivier, Dinah Washington, Billie Holiday, Wardell Gray, Bennie Green, Clifford Jordan, Buddy DeFranco, Oscar Pettiford |

Conrad Yeatis "Sonny" Clark (July 21, 1931 – January 13, 1963) was an American jazz pianist who mainly worked in the hard bop idiom.[1]

Contents

Early life

Clark was born and raised in Herminie, Pennsylvania, a coal mining town east of Pittsburgh.[2] His parents were originally from Stone Mountain, Georgia.[2] His miner father, Emory Clark, died of a lung disease two weeks after Sonny was born.[2] Sonny was the youngest of eight children.[2] At age 12, he moved to Pittsburgh.

Later life and career

When visiting an aunt in California at age 20, Clark decided to stay and began working with saxophonist Wardell Gray. Clark went to San Francisco with Oscar Pettiford and after a couple months, was working with clarinetist Buddy DeFranco in 1953. Clark toured the United States and Europe with DeFranco until January 1956, when he joined The Lighthouse All-Stars, led by bassist Howard Rumsey.

Wishing to return to the east coast, Clark served as accompanist for singer Dinah Washington in February 1957 in order to relocate to New York City. In New York, Clark was often requested as a sideman by many musicians, partly because of his rhythmic comping. He frequently recorded for Blue Note Records, playing as a sideman with many hard bop players, including Kenny Burrell, Donald Byrd, Paul Chambers, John Coltrane, Dexter Gordon, Art Farmer, Curtis Fuller, Grant Green, Philly Joe Jones, Clifford Jordan, Jackie McLean, Hank Mobley, Art Taylor, and Wilbur Ware. He also recorded sessions with Charles Mingus, Sonny Rollins, Billie Holiday, Stanley Turrentine, and Lee Morgan.

As a band leader, Clark recorded albums Dial "S" for Sonny (1957), Sonny's Crib (1957), Sonny Clark Trio (1957), with Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones, and Cool Struttin' (1958). Sonny Clark Trio, with George Duvivier and Max Roach was released in 1960.

Clark died in New York City; the official cause was listed as a heart attack, but the likely cause was a heroin overdose.[3][4][5][6]

Legacy

Close friend and fellow jazz pianist Bill Evans dedicated the composition "NYC's No Lark" (an anagram of "Sonny Clark") to him after his death, included on Evans' Conversations with Myself (1963). John Zorn, Wayne Horvitz, Ray Drummond, and Bobby Previte recorded an album of Clark's compositions, Voodoo (1985), as the Sonny Clark Memorial Quartet. Zorn also recorded several of Clark's compositions with Bill Frisell and George Lewis on News for Lulu (1988) and More News for Lulu (1992).

Discography

As leader

- Oakland, 1955 (1955), Uptown

- Dial "S" for Sonny (1957), Blue Note

- Sonny's Crib (1957), Blue Note

- Sonny Clark Trio (1957), Blue Note

- Sonny Clark Quintets (1957), Blue Note

- Cool Struttin' (1958), Blue Note

- The Art of The Trio (1958), Blue Note

- Blues in the Night (1958), Blue Note

- My Conception (1959), Blue Note

- Sonny Clark Trio (1960), Time/Bainbridge - with Max Roach, George Duvivier

- Leapin' and Lopin' (1961), Blue Note

- Standards (1998), Blue Note

As sideman

With Tina Brooks- Minor Move (1958)

- Blue Serge (1956)

- Go Man! (Imperial Records, 1956)

- Sonny Criss Plays Cole Porter (Imperial, 1956)

- In a Mellow Mood (1954)

- Cooking the Blues (1955)

- Autumn Leaves (1956)

- Sweet and Lovely (1956)

- Jazz Tones (1956)

- Lou Takes Off (1957)

- Bone & Bari (1957)

- Curtis Fuller Volume 3 (1957)

- Two Bones (1958)

- Go (1962)

- A Swingin' Affair (1962)

- Landslide (1962)

- Soul Stirrin' (1958)

- The 45 Session (1958)

- Bennie Green Swings the Blues (1959)

- Bennie Green (1960)

- Gooden's Corner (1961*)

- Nigeria (1962*)

- Oleo (1962*)

- Born to Be Blue (1962)

- The Congregation (1957)

With Philly Joe Jones

- Showcase (Riverside, 1959)

- Cliff Craft (1957)

- Jackie's Bag (1959)

- A Fickle Sonance (1961)

- Vertigo (1962)

- Tippin' the Scales (1962)

- Poppin' (1957)

- Hank Mobley (1957)

- Curtain Call (1957)

- Candy (1958)

- Easy Living (1962)

- The Sound of Sonny (1957)

- I Play Trombone (1956)

- Mexican Passport (1956)

- Music for Lighthousekeeping (1956)

- Oboe/Flute (1956)

- Smithville (1958)

- Stan "The Man" Turrentine (Time, 1960 [1963])

- Jubilee Shout!!! (1962)

- Preach Brother! (1962)

References

- Reid Thompson. "Grant Green Quarter Recordings with Sonny Clark, reviewed by All That Jazz". Retrieved 2009-06-23.