SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2017

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2017

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

EARTH WIND AND FIRE

(May 20-May 26)

JACK DEJOHNETTE

(May 27-June 2)

ALBERT AYLER

(June 3-June 9)

VI REDD

(June 10-June 16)

LIGHTNIN’ HOPKINS

(June 17-June 23)

JULIAN “CANNONBALL” ADDERLEY

(June 24-June 30)

JAMES NEWTON

(July 1-July 7)

ART TATUM

(July 8-July 14)

SONNY CLARK

(July 15-July 21)

JASON MORAN

(July 22-July 28)

SONNY STITT

(July 29-August 4)

BUD POWELL

(August 5-August 11)

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/james-newton-mn0000141805/biography

JAMES NEWTON

(b. May 1, 1953)

http://www.jamesnewtonmusic.com/biography/

http://www.jamesnewtonmusic.com/

(translated by Pete Kercher, from the liner notes of the CD “As the Sound of Many Waters”, 2000 New World Records)

EARTH WIND AND FIRE

(May 20-May 26)

JACK DEJOHNETTE

(May 27-June 2)

ALBERT AYLER

(June 3-June 9)

VI REDD

(June 10-June 16)

LIGHTNIN’ HOPKINS

(June 17-June 23)

JULIAN “CANNONBALL” ADDERLEY

(June 24-June 30)

JAMES NEWTON

(July 1-July 7)

ART TATUM

(July 8-July 14)

SONNY CLARK

(July 15-July 21)

JASON MORAN

(July 22-July 28)

SONNY STITT

(July 29-August 4)

BUD POWELL

(August 5-August 11)

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/james-newton-mn0000141805/biography

JAMES NEWTON

(b. May 1, 1953)

Artist Biography by Richard S. Ginell

James Newton

is a thoroughly contemporary artist, making elegant, sometimes

eccentric, always high-minded albums that reflect a wide variety of jazz

and classical influences without giving a fig about what happens to be

popular at a given time. Besides producing a lovely tone quality, his

flute work is highly resourceful, making use of flutter-tonguing,

birdlike effects, and simultaneous vocal/flute lines, trying to push the

envelope of his instrument. As a composer, Newton finds wellsprings of inspiration in John Coltrane, Charles Mingus, and Duke Ellington -- the latter whose music he transformed completely on the adventurous The African Flower album -- and he writes charts for all kinds of combinations of instruments.

Newton's first musical experiences were on the electric bass as part of a Motown cover band in San Pedro, which he quit to form a Jimi Hendrix-style

trio. However, he also picked up alto and tenor saxophones while in

high school, not discovering the flute until he was 16. Heavily

influenced by Eric Dolphy -- to whom he has been compared -- and Roland Kirk, Newton

began to lean toward the avant-garde in jazz while studying classical

music at Cal State Los Angeles. Soon after moving to Pomona, he joined a

local band, Black Music Infinity, that was led by then free jazz

drummer Stanley Crouch, with Arthur Blythe and David Murray as co-conspirators. Feeling the competitive heat on saxes, Newton decided to concentrate totally on the flute at age 22. A year after graduation (1978), he made a move to New York with Murray, where he hooked up with Anthony Davis on three LPs, played in Cecil Taylor's

big band, and started recording as a leader on several small and large

labels. He moved back to San Pedro in 1982 and started teaching jazz

history, composition, and jazz ensemble at the California Institute of

the Arts in Valencia. Over the years, Newton

has also written several classical commissions for various-sized

ensembles, and in 1990, he published a book, Improvising Flute. Alas,

not enough of his recordings are currently available to give one a

decent idea of his wide-ranging tastes.

http://www.jamesnewtonmusic.com/biography/

BIOGRAPHY

James Newton (composer/flutist/conductor)

JAMES NEWTON

Mr. Newton’s work encompasses chamber, symphonic, and electronic

music genres, compositions for ballet and modern dance, and numerous

jazz and world music contexts.

Mr. Newton has been the recipient of many awards, fellowships and

grants, including the Ford Foundation, Guggenheim, National Endowment of

the Arts and Rockefeller Fellowships, Montreux Grande Prix Du Disque

and Downbeat International Critics Jazz Album of the Year, as well as

being voted the top flutist for a record-breaking 23 consecutive years

in Downbeat Magazine’s International Critics Poll.

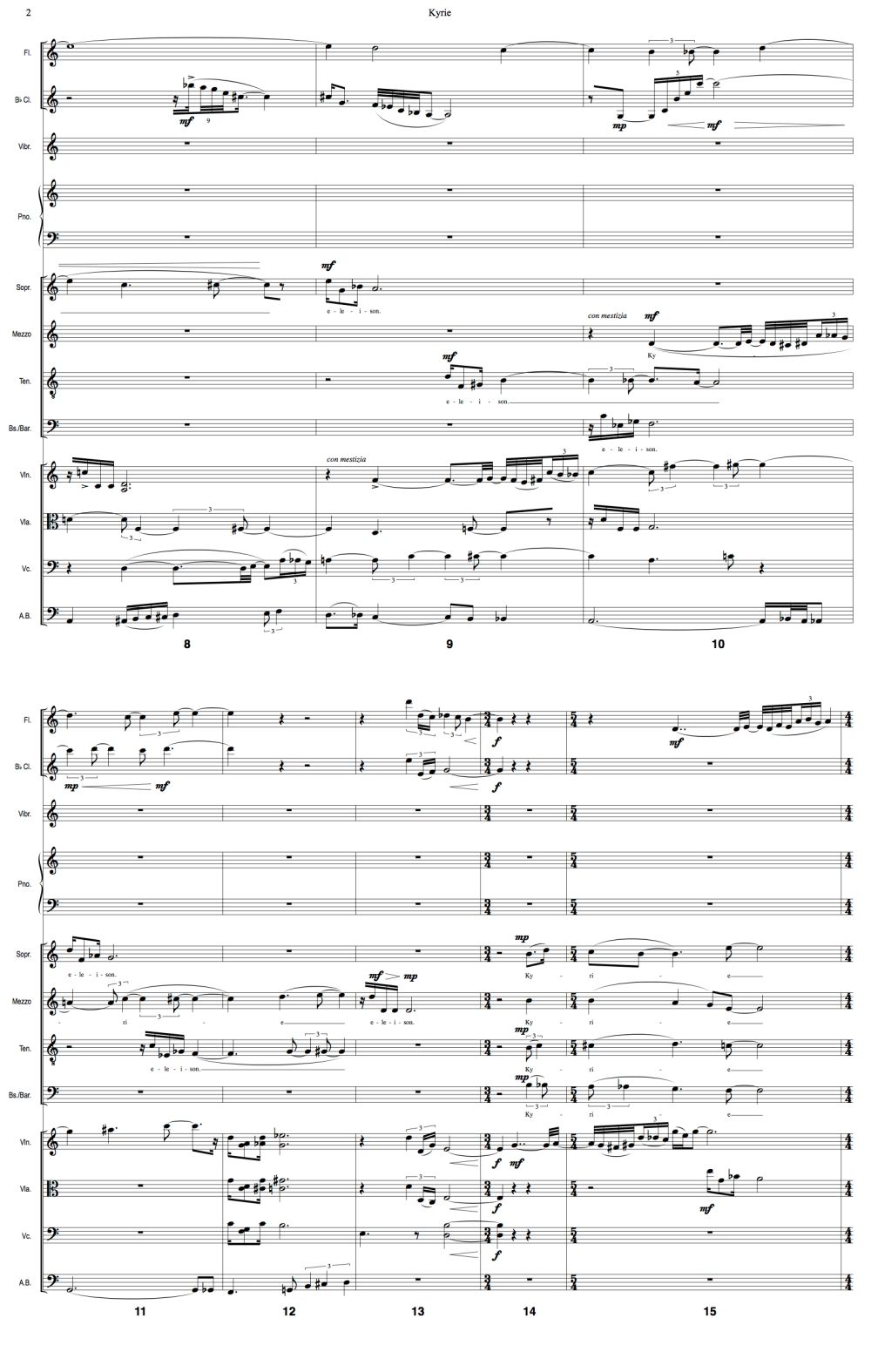

In 2005 Newton decided to commence the greatest challenge of his

compositional career – a trilogy of large-scale sacred works: a Mass, a St. Matthew Passion and a setting of Psalm 119. The Mass, completed

in early 2007, received its premiere at the 2007 Metastasio Festival in

Prato, Italy. Its U.S. premiere (an expanded choral version) occurred

in 2011 with Grant Gershon conducting the Los Angeles Master Chorale at

Walt Disney Concert Hall. Newton completed his St. Matthew Passion in

2014 and it received its World premiere, again with Grant Gershon

conducting Coro e Orchestra del Teatro Regio di Torino, at the Torino

Jazz and La Sidone Festivals in 2015. Mr. Newton is the first African

American and the first composer rooted in the Jazz tradition to compose a

St. Matthew Passion. His research on the final part of the trilogy, Psalm 119, will begin in the summer of 2015.

Described as a musician’s renaissance man, Newton has performed with

and composed for many notable artists in the jazz and classical fields.

San Francisco Ballet, Coro e Orchestra del Teatro Regio di Torino,

Vladimir Spivakov and the Moscow Virtuosi, Anthony Davis, Jose Limon

Dance Company, Dino Saluzzi, Zakir Hussain, Avanti Chamber Orchestra,

Grant Gershon and the Los Angeles Master Chorale, Billy Hart, Gloria

Cheng, San Francisco Contemporary Music Players, Henry Threadgill, the

Los Angeles Philharmonic New Music Group, Ensemble für neue Musik

(Zurich), New York New Music Ensemble, Southwest Chamber Music, Jon Jang

and Frank Wess among others.

Mr. Newton’s works have been performed at notable venues including

Carnegie Hall, the San Francisco Opera House, The Kennedy Center for

Performing Arts, Cité de la Musique Paris, France, Berlin National

Gallery, Teatro Romano, Verona, Italy, The Walt Disney Concert Hall,

Hollywood Bowl, RAI Auditorium, Torino, Italy, Blas Galindo Auditorium,

Mexico City, Teatro Strehler, Milano, Italy, Theatre de la Ville, Paris,

France, Parco Concert Hall, Tokyo, Japan, DIRECTV Music Hall, Rio De

Janeiro, Severance Hall, Cleveland, Amsterdam Museum of Modern Art and

The Whitney Museum, New York, New York.

Newton currently holds a distinguished professorship at the

University of California at Los Angeles in the Department of

Ethnomusicology. He has also held professorships at University of

California at Irvine, California Institute of the Arts, and Cal State

University Los Angeles. In May of 2005 Newton was awarded a Doctor of

Arts Degree, Honoris Causa, from California Institute of the Arts.

http://www.jamesnewtonmusic.com/

“As in the seventeenth century, perhaps the

composer and the improviser of the twenty-first century will coincide in

the same person, now with a more complete awareness of his or her role

in a global culture. If all our diverse history and memory are welcomed

to live in such a present, the horizon of peaceful co-existence between

people becomes possible. This generosity of vision on the path to a

world music is Newton’s way.”

--STEFANO ZENNI

Recently released >>

SACRED WORKS

“James Newton has forged an eclectic career as a

jazz flautist, conductor and composer. Here, he demonstrates his skills

as a creator of sacred music with hints of jazz and roots in the

modernist aesthetics.”

--GRAMOPHONE MAGAZINE

Jazz History Online

Retro Reviews

Retro Reviews

James Newton: "The African Flower" (Blue Note 46292)

by Thomas Cunniffe

In

1988, as my Senior Honors project at the University of Northern

Colorado, I developed and taught a semester-long jazz history course.

The musical examples for the course were included in a 23-cassette

collection which chronicled the history of jazz from 1902 to the

present. For the most part, selecting the 500 tracks for the tapes was

fairly easy: between the unquestioned classic recordings and the ones I

wanted to include, I usually had more music than would fit on the tapes,

so the toughest part was figuring out what to omit. However, the final

tape, which brought the music to the present day, was a little more

challenging. I wanted to include musicians who were already established

by 1988, and who I hoped would still be creative forces in the decades

to come. Looking back at the playlist 28 years later, I picked well: Wynton and Branford Marsalis were well-represented, as were Terence Blanchard, Donald Harrison, Bobby McFerrin, and—performing as sidemen—Fred Hersch and Tom Harrell. The glaring exception was the track by flutist James Newton, taken from his Duke Ellington/Billy Strayhorn tribute album, “The African Flower”.

Not only did I feel that Newton was an outstanding musician and

arranger, I believed that many of his sidemen (including violinist John Blake, alto saxophonist Arthur Blythe, cornetist Olu Dara, vibraphonist Jay Hoggard, and drummer Pheeroan akLaff)

would also become major innovators. At the time, it seemed a safe bet:

“The African Flower” had already selected as one of the top albums of

1985, and all of the musicians were still very active on the jazz scene.

The album also appeared on several best-of-the-80s jazz lists. However,

few of the musicians on the album maintained their places in the jazz

firmament.

Despite

the varied fortunes of the musicians, “The African Flower” still holds

up very well. Newton’s playlist includes selections from Ellington’s

early days at the Cotton Club through his lesser-known works of the

mid-sixties. Juxtaposing the familiar with the obscure, Newton’s

arrangements retain the feel of the original scores. The opening track,

“Black and Tan Fantasy” features Dara’s growling muted cornet and

Newton’s flute in tight thirds over the jungle background of Roland Hanna (piano), Rick Rozie (bass) and Billy Hart

(drums). Newton orchestrates searing backgrounds for Blythe and Blake,

and there is a great explosion of sound before Dara’s personal (but

still tradition-bound) solo. The band drops out when Hanna starts a

funky stride solo. Newton takes over with a striking improvisation which

he sings and plays simultaneously. The rhythm digs in as Newton builds

his solo and segues into the stop-time final chorus of the composition.

After the closing quote from Chopin’s Funeral March, Newton and Dara add

a final wail to finish the arrangement. “Virgin Jungle” was my

selection from the album for the jazz history tapes, and I still

consider it the highlight of the disc. Originally a Jimmy Hamilton feature from Ellington’s “Concert in the Virgin Islands”,

the work is a rarity in the Ellington/Strayhorn catalog, as it is built

on a single chord. The Ellington version seems to run out of steam

after 3 minutes or so, but the Newton arrangement harbors an abundance

of energy throughout its 11-minute duration. Hart remains on the drum

set with akLaff playing talking drums. After the opening drum duet,

Newton’s setting creates an exotic atmosphere with plaintive calls on

flute, bass and violin, followed by rich chords on vibes. The opening

melody is delivered with brio by the front line, followed by a moody

episode of collective improvisation. Hoggard plays a fluid opening solo

in close consort with Rozie’s bass. Blake’s violin solo is intense and

agitated with highly effective double stops. Newton keeps the intensity

high, while only using the multiphonics on a few occasions. While the

previous solos had featured a background figure based on the last phrase

of the original melody, the group also reprises a little of the

collective improvisation behind Newton. Blythe follows with a

full-throated sound and melodic ideas that move between inside and

outside playing, and then Dara closes the horn solos with an adventurous

and mournful statement on muted cornet.

Newton connects the worlds of Strayhorn and Mingus for the last track on the first side, “Strange Feeling”, originally a movement from “The Perfume Suite”. Milt Grayson

(the only musician on the album who actually performed with Ellington)

provides a darkly-colored vocal over Newton’s highly vocalized

arrangement. Ellington’s haunting “Le Fleuette Africaine” opens the

second side. The rich colors come from the combination of Rozie’s

fluttery bass line, and the delicate interplay between Newton’s pure

flute, Blake’s lightly played violin and Hoggard’s understated

vibraphone chords. Within a track of only four minutes, Newton, Blake

and Hoggard each contribute remarkably complete and fulfilling

statements. akLaff (now on drum set) fuels a brightly swinging jam on

“Cottontail” which features an opening solo by Blythe which bursts with

raw emotion, followed by a spritely duet between Hanna and Hoggard, and a

final spot by Newton, where the flutist rides right on top of the beat

as he propels the ensemble swing to ecstatic heights. “Sophisticated

Lady” is an unaccompanied solo by Newton, and his performance—which

excels on both a technical and emotional level—shows that he was a

rightful successor to the legacy of Eric Dolphy.

The album’s final track, Strayhorn’s “Passion Flower”, opens with a

lush introduction by Hanna. After another deeply-hued passage by Newton,

Blythe takes center stage, playing the melody originally intoned by Johnny Hodges,

but with a harder-edged tone and none of Hodges’ trademark glissandos.

Hanna contributes an impeccably-constructed solo in the center chorus,

followed by another strongly vocalized ensemble passage. Newton plays a

hyperactive half-chorus before Blythe returns to close the album.

So

what happened to the members of this remarkable ensemble? For a few

years, many of them continued their careers as expected, recording

albums on their own and appearing as sidemen on others. In the early

2000s, things started to unravel for some of the musicians. Death took

Hanna and Grayson in the first half of the decade, and Blake passed away

in 2014. Blythe developed Parkinson’s disease (and a website devoted to

paying his medical expenses can be found here).

Dara collaborated with his son, the hip-hop artist Nas, but has not

recorded a jazz album in several years. Hoggard’s website states that he

has a new album out, but I have been unable to find a place to purchase

it. Hart is still going strong, recording albums for ECM, and akLaff

sells his current albums on his website. Newton recorded a superb

follow-up album for Blue Note, "Romance and Revolution"

(with a great version of Mingus’ “Meditations on Integration”) and had a

highly publicized court battle with the Beastie Boys over a

recording/sampling dispute. A long-time educator, Newton has recently

turned his energy to composing sacred choral works, including a setting

of the St. Matthew Passion. The most impressive connection to the

Ellington/Strayhorn legacy has come from Anthony Brown,

who plays maracas and finger cymbals on “The African Flower”. Brown’s

Asian-American Orchestra recorded a dramatically re-written version of “The Far East Suite”

incorporating several instruments from Japan and the Middle East.

Brown’s settings represent the most significant expansion of an

Ellington/Strayhorn work ever attempted. It is not for all tastes, but

it is probably the greatest tangible legacy from “The African Flower”.

Content copyright 2017. Jazz History Online.com. All rights reserved.

http://www.harmonies.com/biographies/newton.htm

Celestial Harmonies

James Newton

Poll-winning flutist James Newton stands in the forefront of a contemporary musical movement which continues to gather momentum on an international scale. Along with several others around the world, he leads the way in breaking down divisive categorical barriers while simultaneously creating a new and inclusive universal music.

Echo Canyon (13012-2), was entirely improvised on solo flute, recorded live, at night, outdoors, beneath a full moon, in the mountains northeast of Santa Fe, New Mexico. Over the years, Newton has completely assimilated music from America, Europe, Japan, India, Africa, South America, and elsewhere. On Echo Canyon, he spontaneously processed them through his personal psyche and transformed them. The whole of Echo Canyon constitutes an original world music, rhythmically free and lovingly connected with healing nature, that contains a near–perfect balance between intellect, spirit, passion, and form. Says Newton from his home in San Pedro, California:

"I've composed and improvised many different kinds of music, disregarding the limitations of established stylistic categories. That's the way my art evolves, and that's the way I am a person.. I've always believed that the whole of the earth is a huge palette, and the cultures of the world are like colors. Most musicians use only a few colors. I like to use many different colors in many different ways."

Newton's musical/cultural odyssey began at an early age. He was born in Los Angeles on May 1, 1953. His father was a career army man, and James traveled with his family throughout the world. He listened to the urban blues, R & B, and gospel recordings his parents played. At the age of ten, he began listening to the Beatles and Marvin Gaye. In 1965, Newton sang and played bass in a seven-piece R & B group, and by 1968, he and his guitarist had formed a trio, playing Jimi Hendrix and other rock music.

During his junior year at San Pedro High, Newton became interested in the flute. At eighteen, he entered nearby Mount San Antonio Junior College, and within two years he was playing European classical music eight hours a day.

From 1973 to 1976, he played in a group that included jazz greats Arthur Blythe, David Murray, Bobby Bradford, and Stanley Crouch. Crouch introduced young Newton to the entire history of jazz, from early Jelly Roll Morton to contemporary Miles Davis. Crouch also introduced him to folk and classical music from around the world, including African Pygmy, Japanese shakuhachi, and Balinese gamelan music.

At Cal State (1975-1977), Newton continued his studies of European classical music while playing jazz at night. In 1978, he moved to New York, where he lived intermittently until 1981, playing jazz with giants such as Cecil Taylor, Lester Bowie, and Anthony Davis. In 1982, he won his first Down Beat critics poll. In 1983 and 1984, he won both the critics and the readers polls. Newton has composed chamber music for piano, cello, and flute, performed by flute and string quartets and woodwind quintets; he has also composed for a variety of solo, duo, trio, sextet, octet and orchestral combinations.

James Newton continues to merge jazz improvisations and Eastern and Western classical music with a wide variety of world folk music. As demonstrated so well on Echo Canyon, the result is a fresh, new, higher consciousness music that taps into world cultures and historical time, addresses itself to the living present, and helps all receptive listeners grow towards a personally integrated, socially harmonious future.

James Newton continues to merge jazz improvisations and Eastern and Western classical music with a wide variety of world folk music. As demonstrated so well on Echo Canyon, the result is a fresh, new, higher consciousness music that taps into world cultures and historical time, addresses itself to the living present, and helps all receptive listeners grow towards a personally integrated, socially harmonious future.

discography

A Musician Writes It, A Rapper Borrows It: A Swap or a Theft?

Music Notes written by a jazz musician and then used repeatedly by the Beastie Boys on an album are at the center of a debate on artistic freedom.

|GEOFF BOUCHER | TIMES STAFF WRITER

If You Can Feel What I'm FeelingThen It's a Musical MasterpieceBut If You Can Hear What I'm Dealing WithThen That's Cool at Least

--"Pass the Mic" by the Beastie Boys

The

embittered jazz musician calls it rhymin' and stealing. The shocked rappers

argue that it's about a minor player manufacturing a musical controversy.

Either

way, James W. Newton Jr. vs. the Beastie Boys is the latest example of hip-hop

artists getting grief from musicians

who view rap song collages as artistic shoplifting.

The heart

of the matter is the Beastie Boys' song "Pass the Mic," which has a willowy,

elongated flute sound rising above its cluster of rock instruments, breakbeats

and turntable scratches. The exotic sounding tidbit, looped more than 40 times

during the Beastie's track, is a six-second, three-note performance that the

Beastie Boys clipped out of a 1982 recording called "Choir," a song

written and performed by Newton, a professor at Cal State L.A. and former

Guggenheim fellow.

Ten years

after Newton released "Choir," the Beastie Boys released "Pass

the Mic" on their acclaimed hit album "Check Your Head." Another

eight years would pass, however, until Newton became aware that his impressive

jazz resume now included a collaboration with the clownish but creative New

York trio.

"I

felt violated," Newton recalled this week. Newton found out when one of

his jazz ensemble students casually mentioned that he had noticed Newton's name

on the Beastie Boys album. Newton was skeptical until the student brought the

CD to class. Then he was livid.

Samples

of music, of course, are a hip-hop staple, and the Beastie Boys have always

sprinkled their compositions with prerecorded music both famous (Rolling

Stones, Led Zeppelin, etc.) and ridiculously obscure. Like other major hip-hop

artists, though, the Beasties spend a considerable amount of time and money

securing clearances for the music they sample.

So why

was Newton upset, unaware and eager to sue? The answer involves the nuances of

U.S. copyrights on composition and recorded performance as well as the

fundamental importance of leaving a forwarding mailing address.

Newton's

record label, ECM Records, tried to reach Newton in 1992 when the Beasties

called to seek clearance on "Choir," but the musician had moved.

Newton's contract with the label gave the company the authority to license out

the recording and, a short time later, a check for $500 was mailed by ECM to

Newton but came back as undeliverable.

Newton

remained oblivious while the Beasties assumed they had taken care of the

matter.

Newton

and his attorney, however, argue that the Beastie Boys only did half the job.

The group secured the sample as a recorded performance but they did not secure

clearance for it as a composition. In basic terms, the performance clearance is

for a musician's work, while the composition clearance is for the handiwork of

the songwriter.

In the

case of "Choir," the performer and composer is Newton, and via the

copyright infringement lawsuit he filed in 2000 he claimed the Beastie's did

not give him his due.

Proper

Clearance

The

Beastie Boys disagreed--they said the snippet was far too short and too simple

to be regarded as a protectable piece of musical work. "We cleared the

recording but did not clear the composition because what we used is three notes

and three notes do not constitute a composition," Adam Yauch of the

Beastie Boys said this week. "If one could copyright the basic building

blocks of music or grammar then there would be no room for making new

compositions or books."

In May,

U.S. District Court Judge Nora M. Manella agreed with the hip-hop stars and

said the performance clearance secured by the Beastie Boys was appropriate for

a shard of music that was "unoriginal as a matter of law."

Newton's

attorney, Alan Korn, is readying an appeal now. He says Manella's decision is a

chilling one for avant garde jazz, electronica and other genres where

traditional notation and song structure do not lend themselves to easy analysis

and charting in a courtroom.

A legal

defense fund has been set up for Newton, who is also the conductor of the

Luckman Jazz Orchestra, and a number of musicians and their organizations have

spoken out on his behalf. The media coverage of the case to date has rankled

the Beastie Boys who believe they have been portrayed as overbearing thieves

looking to exploit a jazz academic. For a group accustomed to political and

social advocacy and a well-known dedication to charity, it has been especially

frustrating.

"Before

spending a lot of money on the case we contacted Mr. Newton and offered him a

generous out-of-court settlement in hopes of avoiding further legal fees,"

Yauch said. "He responded by telling us that the offer was 'insulting' and

said that he wanted 'millions' of dollars. In addition he told us that he

wanted 50% ownership and control of our song.... Mr. Newton's flute sound is just

one of hundreds of sounds in our song. Giving him 50% ownership of our song

seemed unfair."

The

calculus of music creation is a common but tricky practice. There have been

landmark cases involving rap sampling--most notably, Biz Markie's loss after using

"Alone Again" as the core of a song--and its not unusual for

sample-minded artists, such as Sean "P. Diddy" Combs, to split the

profits of a song that hangs its hat on a previous work.

To

Newton, "Choir" is a "defining presence" in the Beastie

Boys song that borrows it. To Yauch it is "a drone in the background"

that has "nothing to do with the central theme of our song." Either

way, "Pass the Mic," remains a Beastie Boys favorite, popping up in

their remixes, their live performances and a recent DVD release. All of it

infuriates Newton who also has to swallow the fact that his

"Choir"--which he composed as an ode to the spiritual music that

inspired him as a youngster--has also made a cameo in the puerile "Beavis

& Butthead" television series thanks to the show's use of "Pass

the Mic."

"This

is a work that celebrates God's place in the African American struggle for

freedom in this country," Newton said. "And, for me, this has become

a nightmare."

JAZZ REVIEW : Flutist Takes Audience on Thrill Ride : James Newton sometimes adds to his palette of sound by vocalizing while holding steady on his instrument.

IRVINE — James Newton has never received the attention he deserves on his home turf. Though the San Pedro resident consistently tops polls as best jazz flutist and is acclaimed in Europe and on the East Coast for his compositional abilities, he performs infrequently here, usually in connection with his job as professor of composition and jazz history at the California Institute of the Arts. His well-received Blue Note recordings that honored the work of Duke Ellington and Charles Mingus were done in New York. His latest release, "If Love" on the JazzLine label, was recorded in Cologne, Germany.

Saturday, Newton was at the Fine Arts Center on the UC Irvine campus fronting a quartet as part of his current residency as the Chancellor's Distinguished Lecturer in Fine Arts. With the sympathetic rhythm section of pianist Kevin Toney, bassist Darek Oles and drummer Son Ship Theus, the flutist took the audience of 150 on a thrill ride of moods and emotions, proving that those accolades from a distance are well deserved.

Newton's "Nelson Mandela" is a good example of his compositional style, a blend of frontier-challenging adventure and traditional sensibilities. The flutist stood savoring the tune's soothing rhythmic pace before tearing off on a spirited theme that was broken by abrupt periods of stillness. The combo then wound its way through a mysterious-sounding passage, led by Newton's inquisitive flute, before the steam and sizzle of his solo.

Blessed with a clean, crisp tone, Newton sometimes adds to his palette of sounds by vocalizing over the flute, most often during blues-based passages. This isn't to cover for a lack of technical skill, which Newton has plenty of, but to color his sound and provide emotional depth. The flutist hummed, shrieked and buzzed over a wide range while he played, sometimes moving the pitch of his voice while holding steady on his instrument. The effect worked best when he added mid-range compliment to a similar flute pitch. At higher ranges, his falsetto occasionally broke into a tea-kettle-like irritating whistle or a shrill nag.

Cunning arrangements of Ellington's "Black and Tan Fantasy" and Mingus' "Sue's Changes" utilized a variety of moods and rhythmic frames for solos. Keyboardist Toney played with a hip modernism, matching intense runs with dissonant block-chord statements and surprisingly placed moments of quiet. Oles proved accurate and inventive, inserting double stops and chords strummed with his thumb on Newton's "Outlaw," a tune that recalls the quirky rhythms of Thelonious Monk's "Well You Needn't."

But Theus, a drummer who has worked with Pharoah Sanders and Horace Tapscott, proved to be the crowd-pleaser, turning cymbal-crazed solos into roiling tom-tom statements or overwhelming onslaughts against his snare. The drummer also shone in support, with percussive punctuation and seductive brushwork.

"Mr. Dolphy," Newton's tribute to the man (Eric Dolphy) he cites as his greatest influence and presented here as a duo with Theus, was the kind of energetic statement the late saxophonist-flutist was known for, and a chance for Newton to work at searing speeds. It's ironic that Dolphy, himself a Los Angeles native, had to move to New York before his pioneering ways were accepted. Let's hope Newton doesn't have to do the same.

Cunning arrangements of Ellington's "Black and Tan Fantasy" and Mingus' "Sue's Changes" utilized a variety of moods and rhythmic frames for solos. Keyboardist Toney played with a hip modernism, matching intense runs with dissonant block-chord statements and surprisingly placed moments of quiet. Oles proved accurate and inventive, inserting double stops and chords strummed with his thumb on Newton's "Outlaw," a tune that recalls the quirky rhythms of Thelonious Monk's "Well You Needn't."

But Theus, a drummer who has worked with Pharoah Sanders and Horace Tapscott, proved to be the crowd-pleaser, turning cymbal-crazed solos into roiling tom-tom statements or overwhelming onslaughts against his snare. The drummer also shone in support, with percussive punctuation and seductive brushwork.

"Mr. Dolphy," Newton's tribute to the man (Eric Dolphy) he cites as his greatest influence and presented here as a duo with Theus, was the kind of energetic statement the late saxophonist-flutist was known for, and a chance for Newton to work at searing speeds. It's ironic that Dolphy, himself a Los Angeles native, had to move to New York before his pioneering ways were accepted. Let's hope Newton doesn't have to do the same.

Interview with James Newton

The following was done over the phone in late March and transcribed by Kevin Sun.

(Temporary notice: This Friday, the wonderful pianist

Yegor Shevtsov is playing Newton “in the context of Olivier Messiaen,

Pierre Boulez and Harrison Birtwistle.”

An excerpt of Shevtsov playing Newton is included at the bottom of this page.)

Ethan Iverson: We’re speaking the day after Arthur Blythe left us.

James Newton: Yes, we are. I’m flooded with

emotion. I’m also overwhelmed with gratitude, and I say that because

Arthur Blythe was one of the most giving people that I knew. I remember;

specifically, I was playing in a jazz-rock group in Pomona. I was

playing electric bass and I’d also been playing flute for a few years.

Stanley Crouch lived across the street, and he said, “Your band sounds

horrible, you should come hear my band, so next weekend, come hear my

band and bring your flute!”

I walked into Stanley’s house, and it was Arthur Blythe, Bobby

Bradford, Mark Dresser, and Stanley. (David Murray would join the band a

few months later.) I sat down to listen, and I was astounded. I could

hear the influence of Ornette a little bit in the shape of the music.

But the other thing that struck me the most of all was just the genius

of Bradford and Arthur Blythe together. It was astounding because their

sounds were so significant, and they had such authority. This was about

1973, just before I think Bradford recorded Science Fiction or

he had just recently done it with Ornette. Arthur was really into late

Coltrane at that time. I’d never heard an alto that had that kind of

weight on the bottom of the horn. It was like being in church. Trane had

that thing coming out of a line of preachers, and Arthur had a similar

sound in his music. The playing scooped you up emotionally, you found

yourself in these spaces that were very rare and very precious and very

powerful, emotionally. Hearing Arthur and then hearing this phenomenal

logic of the construction of solos that Bobby Bradford would put

together, where you could just see one idea and then another and then

another and then the dialogue among the ideas! At this time they were

playing solos for 15 to 20 minutes. When I heard them, I felt this is

where I needed to be.

At that time I could barely play. I remember I asked Frank Wess about

something once and I said, “Well, what did you think of that person’s

playing?” And Frank Wess said, “They sound like a fart in a windstorm,”

and I don’t think I was much better than that.

Everybody displayed incredible patience and gave me the opportunity

to learn a lot. Performing with that level of musicians was something

that had such a major impact on me. We stretched out a lot because

everyone was so into Duke and the way the Ellington orchestra would hit

your body was so important.

David Murray and I were just talking yesterday about how beautiful

Arthur was as a human being, and you know, just a major artist on every

level. And I love the things he did with Abdul Wadud and Bob Stewart,

and Arthur’s work with Horace Tapscott in LA was really important.

Arthur was one of the major musicians in the city before he moved to New

York, and Arthur never forgot people. He was always doing things for

other people.

When I came to New York, Arthur Blythe and David Murray set me up.

Two weeks after I had moved in, I was at Columbia studios, doing the Lenox Avenue Breakdown

recording and there’s Jack DeJohnette, Cecil McBee, Blood Ulmer,

Guillermo Franco, and Bob Stewart, and wow! David Murray gave me a place

to live. “Stay here as long as you need so you can save up enough money

to move your family to New York.” That’s something I’ll never forget.

So all of us were close, we looked out for one another, it’s something

precious in my memory. David also arranged for him and me to do a

month-long duo tour of Holland, which was my first European tour. The

music soared.

Arthur Blythe: that’s the most compelling alto sound that I’ve ever

heard in my life. I can say that without actually thinking twice about

it, you know. The ability to seamlessly put together late Coltrane and

Charles Christopher Parker, to make that work within a language is no

small leap. He figured out a way to bring those two elements together

and create something that was his own.

EI: When you mentioned combining Bird and Trane, the first thing that comes to my mind is how they really were both bluesmen.

JN: I’m trying to tell you! They used to call him “B. B. B.,” “Blues Boy Blythe,” you know?

I think that’s one of the things that was really stressed by both

Bradford and Arthur. You had to have a close relationship to the blues

and the feeling of the blues in the context of music that does not use

blues form. Of course, Ellington is someone who laid it out for all of

us who came after him. Also, we looked to Billie Holiday and so many

others who took that approach and created art that will last for

millennia and further.

So the blues was always, always in the equation. Also, a lot of us

came out of the black church, and we could all hear it and feel it in

Trane’s playing. I’ve thought so much about why Trane took his direction

late in life. In one of the very last recordings, Expression,

it’s like he’s partially coming back to changes again and including it

in his previous explorations, and all of a sudden his search is coming

full circle.

But what I love about Arthur is that I think he took that influence

and figured out a way to do something that no one else that was touched

by Trane’s music did. During that period in the 70s, Trane’s influence

was probably as large as Bird’s was right after his passing, and so,

yeah, Arthur Blythe, wow.

EI: It seems to me that you’re saying a lot of

music post-Coltrane influenced by Coltrane wasn’t so bluesy or connected

to the church.

JN: Yeah, in part. There were people who had those

connections, and there were others who didn’t. On the other hand, I

strongly feel that people should have the freedom to create in the way

that they are motivated. I guess part of that mentality comes from the

fact that I did not start reading music until I was 18 years old, and I

did not pick up the flute until I was 16. I played by ear for a few

years before I read a note of music, so I had to develop my ears. Mainly

I was playing rhythm and blues, and I was also playing electric bass in

a Hendrix cover band.

EI: Ok, James so this is our cue to go back, why

don’t you lay it out for us where you’re from, where you grew up, and

how you got into music.

JN: Sure. I was born in LA, May 1, 1953. We did not

stay in Los Angeles for very long because my father was in the army as a

career man for 20 years. We were moving all the time. I always said

that I got used to the life that I lived as an adult because I had

already lived that way as a child. We spent a lot of time in Germany; I

remember living in Augsburg, Munich, Ulm, and Dachau. We lived in Dachau

for about a year and a half; this was about 1962 and 1963. Death was

still hanging like a cloud in the air. Death was pervasive. I was trying

to deal with that and also trying to deal with images of American

lynchings that I had seen in books and magazines. It struck me at a very

young age that the lowest common denominator in humanity can drop

insanely low.

Two things were gigantic in my childhood. The first is this: we would

go home to the States to visit family. My mother was from Aubrey,

Arkansas. (Oliver Lake is my cousin, and he’s from Aubrey!) We would go

back home during the summers, and I’d have a chance to be on my

grandparents’ farm, so that gave me a world of experience. I remember my

father had bought a Gründig reel-to-reel tape recorder in Germany, and

the word got out, and people would come to my grandparents’ farm to

record. It was like my father was doing fieldwork! There’d be gospel

quartets and blues singers coming to the house, and they were just

thrilled to hear themselves played back on tape.

The first time that music touched me in a way I could not comprehend

was in Aubrey when I was about four or five. Four women were singing a

cappella in a church. They were singing spirituals, and I couldn’t

recall the spirituals they were singing, but I remember my spine

tingling, and I remember being transported to a space that I have been

chasing for the rest of my life. I’ve always wanted to get there because

it was maybe the warmest space I could imagine as a child. Nothing else

felt like that, so I’ve been chasing that ever since both as a

performer and composer.

And I remember another occurrence in Munich, Germany when our school

went on a field trip (I can still smell the diesel fumes from the school

bus) and I was 9. We went to a museum, and there was an El Greco

exhibition. Seeing that art planted the seed for having a deep passion

for visual art, which has continued to grow throughout my life.

The church thing and the blues thing from those experiences from down

South, together with my passion for visual art, have forever changed

me. They led me on a pathway. It took me a long time to understand the

pathway. Sometimes you walk through life, and the revelation does not

hit you immediately, it might hit you over decades. Then suddenly you

arrive in this space where you have an understanding of what you’re

supposed to produce as an artist. Your unique path becomes clear with a

goal in mind to lay down something that is going to stand the test of

time. It is a reflection of the things that are important to you: the

passions that you have about artists that have influenced you and the

way that you feel about your surroundings, about your family, about the

political climate, how you feel about walking in nature and

understanding why women and men are obsessed with trying to capture

nature within the context of art for thousands of years.

EI: What was your first instrument?

JN: It was the electric bass. We came back to

California before the riots; I remember being in South Central LA during

the Watts Riots. Anyway, I started with the electric bass at 12 after

my parents moved to San Pedro, Ca. I joined a rhythm and blues groups

and was singing the high falsetto parts in three-part harmonies. Anthony

Brown, the composer, multiple percussionist, drummer, bandleader in the

Bay Area and an incredible scholar and a member of Asian Improv, was my

childhood friend. We started working like crazy in a Hendrix cover band

called Axis (how original!) after I left the R&B group. The Hendrix

cover band’s repertoire consisted of compositions from Are You Experienced?, Axis: Bold as Love and some pieces from Electric Ladyland,

along with some standard blues pieces. Hendrix has been a significant

influence on what I’ve done. I still listen to him all the time. I think

he’s one of the greatest orchestrators, the way he would layer the

guitars and he’d have different effects on the different guitars

impacted the way I approach orchestration. Hendrix also had a special

relationship with the blues: This is somebody that studied both country

blues and urban blues, and to this day, I can’t wrap my head around the

conclusions that he drew from his studies at a young age. The way he

used the blues to have a beautiful dialogue with all this

experimentation that was occurring was another thing that I’ve tried to

keep with me as I moved through the evolution of my musical language.

.

.

There was a friend who played incidental music on the flute behind Death of a Salesman.

That moment really hit me, and I said, hey, I want to play the flute. I

was 16 and went to a pawnshop (on November 22, 1968) and got a flute

that leaked like I don’t know what, but I just fell in love with the

instrument right away and started practicing a lot. Eventually, I

entered Mount San Antonio Junior College. My reading wasn’t that good,

but by the end of the first year, I’d caught up with the people there,

and maybe I moved forward a little bit more because I was practicing six

to eight hours a day. I quickly learned to read because when you take

so much music from recordings, you’ll hear a rhythm and you’ll say, I

know that rhythm, and then you’ll look at the score, and you’ll say,

“Ah, that’s what that rhythm looks like notated.”

I fell in love with Eric Dolphy’s playing and composing, and I sought

out Buddy Collette to study. I studied with Buddy for at least 15

years. Even in the ‘80s when I was coming back to California from New

York, I continued studying with him. I’d always come back to him to get

tuned up. He was such a master teacher. Buddy Collette was still in my

ear long after the early days. I’d see Buddy Collette being called to do

classical saxophone gigs of contemporary music. He’d just put another

mouthpiece on his instrument and make that mental shift. I remember

hearing him playing a work of T.J. Anderson’s that I love, “Variations

on a Theme by M. B. Tolson,” but man, what a piece and Buddy just killed

it.

EI: Collette taught Eric Dolphy, right?

JN: Oh yes, he did.

EI: Who else did he teach?

JN: Charles Lloyd and so many others. Charles and I

talk about Buddy Collette all of the time. Charles and I both are

incredibly grateful for Buddy Collette because he was a musician’s

musician. I love Charles, and I learned a great deal from him.

There’s a school, and I consider myself to be a part of it, and I’m

very honored to be a part of it. Not just Buddy Collette but also Lloyd

Reese, one of those seminal figures in Los Angeles music who taught Eric

and taught Mingus. The way that I look at it, there’s a whole school

premised on the fact that Art Tatum was in LA a lot during that time,

and his harmonic thinking impacted a lot of the musicians here. Mingus

and Dolphy were learning things about Tatum’s harmonies from Lloyd

Reese. If you look at the essay Mingus wrote in Let My Children Hear Music; he discusses the fact that Lloyd Reese is breaking down a part of Stravinsky’s Firebird

to him and he’s trying to figure out what the heck is going on. And, if

we step back and look, if you have a circle with a 25-30-mile radius at

that time, who would be within that circle? Tatum, Mingus, Schoenberg,

Stravinsky, Dolphy. All within that space!

Now let’s step back and go a little further. Jazz did not touch

Schoenberg so much other than what he might have picked up from

Gershwin, but Stravinsky had a relationship with ragtime and jazz for

the majority of his career, and one of Schoenberg’s students was

teaching 12 tone techniques to Buddy Collette and some other people. Mel

Powell was similarly bridging the different communities for a different

set of evolved reasons a few decades later. Reese’s tenure was so

exciting. You have this beautiful wedding of traditionalism and

experimentation occurring at the same time, and I’ve always tried to be

between both the worlds, you know, and that model comes out of Lloyd

Reese’s school. It also comes from Buddy, Eric, and Mingus and so many

other people in LA in the late 40s and 50s.

A lot of people don’t know that there was a dialogue between Eric

Dolphy and Bird when Bird was in Camarillo. One of the things that Bird

had discussed with Eric that he wanted to get done was to have the

ability to study with Varèse, and Eric kept that in himself. That’s just

my humble opinion that he just kept it in his mind. He learned Varèse’s

seminal flute solo, Density 21.5. Hale Smith took Eric to

Varèse’s house in New York because he knew him, and after an extended

session going through the work, Varèse signed a copy of Density 21.5 score, dedicated to Eric. It is in the Library of Congress.

EI: James, this may be a tangent, but when I think

about LA in the 40s and 50s, I also think of Hollywood and all that

incredible music, where the musicians involved in many of the greatest

film scores had to know something about jazz and know something about

classical music.

JN: It’s true. It’s entirely true. You had many

film composers that were delving into contemporary classical music and

jazz: I would say, you know, from early jazz up to postbop.

I’ll tell you a few things. There were segregated unions in LA. Buddy

Collette and Red Callender — another significant influence for me who

shaped so much of what I’m doing — helped to merge the segregated

unions. Marl Young, Jerry Fielding, and Groucho Marx were important in

supporting these efforts. There are always these absurd stereotypes:

jazz musicians can’t read. Before Red came to Los Angeles, he was the

principal bassist in the Honolulu Symphony. They were fluent in many

different styles of music. One of the things that was always important

about let’s say a particular LA school would be the ability to sit in

some environments, including film, and be able to have all that music

laid out in front of you and you sight read it with authority and

stylistic flexibility. The ability to blend your sound with others was

also stressed to a high degree.

Because I was a late bloomer and started the flute late, one of the

things that Collette stressed over and over and over to me, and I have

put a lot of time into, was sight reading. Another reason why I had to

put a lot of time into it was that my father initially hated the fact

that I decided to become a musician. One of the first things that he

said to me was, “I didn’t’ work my way out of poverty for you to turn

around and slide right back into it.” And he was very serious! When he

found out that I was determined to become a musician, in his typical

fashion, he did a lot of research and he said, “I heard you have to

learn how to sight-read well.” He was right, it became very important,

and it helped me a great deal in my career.

I’ll tell you another story that’s not well known that I learned from

Mel Powell. When Stravinsky was writing Agon, he asked Conte Candoli to

come to his house in Hollywood, because there were certain alternate

fingerings for the trumpet that jazz musicians were using that he wanted

to familiarize himself with to get certain effects that he incorporated

in Agon. And Agon does not have an in-your-face jazz influence, as opposed to say the first movement of Symphony in Three Movements, which is just so full of jazz iconography.

But, yeah, so, I mean, there was this kind of hybrid musician that

came out of the demands of Hollywood as well as the creative endeavors

that were occurring in the African-American community during that time.

There was also the impact of Los Angeles gospel, cool jazz, and R&B.

It was a stylistically diverse period in the music.

Also, in LA, there’s an abundance of trees and nature everywhere.

Birdsong orchestrated Eric’s neighborhood. Much later, Freddie Hubbard

roomed with Eric Dolphy in Brooklyn, and Freddie told me how Eric would

go up on the roof to practice and dialogue with the birds. I think the

environment makes a difference, you know? So if you add that element to

the equation, then you can understand that the music had to go a

different way in L.A. It’s not like a hyper-urban environment in the

Midwest or New York City or Baltimore. Different, like the musicians who

came up out of the South who had a thing that was very specific having

to do with the fact that there’s an in your face blues aesthetic

occurring and spirituals and gospel music embedded in so much of that

language. And just like, Dallas and New Orleans are going to give you

two things that are different, but have significant commonalities having

to do with how the roots of the music flourished within those

particular environments.

L.A. has that thing, too, but it’s just in a different way. I loved

it when Andrew Cyrille called Los Angeles, “Lower Alabama.” Yep. In

other words, there are a lot of country people that were a part of the

Southern migration to L.A.

EI: After college, did you keep playing recitals of European classical music?

JN: Oh yeah. I did that up until deep in the 1990s. I used to occasionally get with different people to play a lot of repertoire.

EI: You must have had a graduation program or something, do you remember what that was?

JN: For my senior recital, I played J.S. Bach’s E Minor Sonata for Flute and Harpsichord, Debussy’s Trio Sonata for Flute, Viola, and Harp, the Paul Hindemith’s Sonata for flute and piano, and the Ibert Flute Concerto.

I still love listening to the Ibert. I love the Ibert even more because

I heard from some of my elders that he came to America and upset a lot

of folks because they asked Ibert who was the most important American

composer and his response was Duke Ellington.

EI: Nice!

JN: A couple of years before he died, the Hollywood

Music Society of Film Composers honored Toru Takemitsu. They asked him,

who is your favorite composer, who has inspired you the most? And

Takemitsu stood up, and he said, “Duke Ellington.” And I said to myself,

“Aw man! That’s what time it is!”

I went through a period where I did a lot of solo flute concerts in

the 70s and 80s, and in those concerts, I played works of my own. I

might play pieces by Ellington, Monk or Mingus, and different colleagues

of mine. But I would also play Density 21.5 by Varese, Mei or Requiem by Fukushima, Debussy’s Syrinx, and other classical solo repertoire mixed in.

EI: Jolivet wrote some good flute music, right?

JN: Yeah! I would practice his Concerto pour flûte et orchestre a cordes, and he also wrote a lot of amazing solo flute repertoire like Chant de Linos.

I loved the polymodality in Jolivet’s music, and it’s also rhythmically

compelling. He’s grown a little bit out of fashion, and that’s sad.

Hopefully, he’ll have resurgence.

EI: And then there’s Messiaen.

JN: When I went through the music Dolphy had left

with Hale and Juanita Smith. I learned a lot. I loved seeing Jaki

Byard’s and Randy Weston’s music in the Dolphy collection. There were a

lot of Latin composers’ scores. Dolphy was a Panamanian-American. He

also had Messiaen’s Le Merle Noir. So Dolphy was into Messiaen a

before he died in ’64. It is possible that Messiaen’s music could very

well have inspired some of Dolphy’s own birdsong explorations.

It’s just incredible, looking at the journey of rapid development

that Messiaen had, how he got a lot more specific about how birdsong

worked and how he would translate it into his compositions. Then you can

look the rapid development of Eric Dolphy, from the Chico Hamilton

recordings when Buddy Collette got Eric that gig, to 1960. It is like

the language is an exploding sonic boom. Getting back to the flute

repertoire, Andrew White left us with accurate transcriptions of some of

Eric’s solos, and they were harder than Berio’s Sequenza, the

most challenging music in the classical repertoire of that timeframe.

The transcriptions of Eric’s solo demanded so much more technically than

the Berio.

So I connect Messiaen and Eric beyond the love of birdsong, there’s

also this almost insatiable desire for expansion and development of

techniques along with the celebration of faith and beauty.

When I was 19, and I heard the “Liturgie of Cristal” from the Quatuor Pour la Fin du Temps,

that was one of those moments when I realized that I was in a space

where art is playing with technique in profoundly new ways. The language

is very different. It’s like you’re breathing rare air, and it took me a

while to understand, “OK, I can hear the birdsong,” you know. I

purchased the score quickly after hearing that first performance, and it

stated, “Comme un oiseau,” “like a bird.”

There’s astonishing ability to be able to have these different planes

of musical composition co-existing with independence among one another

but still at the same time connecting. The harmonic cycle is different

from the cycle of rhythms. I remember the rhythmic pedal has seventeen

values and the harmonic loop consists of twenty-nine chords, and you

have this incredible fluid birdsong that’s occurring in both the

clarinet and the violin, and I believe you have a rhythmic pedal of five

notes in the cello. I have to go back and look at that specifically,

but one of the things is the color specificity of the musical language.

The first chord starts with the double appoggiatura, resolving to an

F13; and after the double appoggiatura occurs, the resolution is an F13

and check out this voicing: F G Bb C (left hand) each dyad a whole step

apart, and in the right hand you’ve got Eb A D, combinations of fourths,

one perfect and the other augmented. I’m going, “Whoa, wait a minute.

What?” Those first two chords…it’s almost as if you do not need to hear

anything else after that, they’re so profound! But it’s also those

specific voicings; it’s the dynamics, it’s again the color specificity

that just grabbed me to no end.

Then, in the next decade, the real birdsong revelation is dropped, and that is Catalogue d’Oiseaux,

because Messiaen has observed the flight of birds in their environment

and transformed that flight into musical lines. He’s dealt with a

particular bird that was flying just above a lake near a cliff, and he

also considered the time of the day that the music was written and other

aspects of the environment. Just like other non-Western music

performance must occur at different specific times of the day or

evening. Messiaen pushed himself to a place where no one else could be,

and very few people understood, you know? Yvonne Loriod understood where

he was, but very few other people did.

Now let’s look at Eric. Everyone knows Eric loved Charles Christopher

Parker to no end. You hear it in Eric’s language to the nth degree, but

what he did was construct scales and modes that were his own, that he

incorporated not only into the compositions but even more so in the way

that he approached playing the changes, which sometimes means he’d play

notes that some musicians thought were incorrect. But that’s what he was

hearing. There was this beautiful and rigorous dialogue going on

between Yusef Lateef, John Coltrane, George Russell and Eric Dolphy,

where they were theoreticians of the highest order that were sharing

their found information with one another and impacting one another’s art

in profound ways, you know?

But with Dolphy, it’s not just the way that he approached harmony

that was so unique, the choice of instruments was also unique. Look what

he did with the bass clarinet! And he’s still my favorite flute player

by far. His alto playing developed out of his love of Bird, Rabbit,

Benny Carter and others.

He spoke Spanish also, which might have had an impact on part of the

uniqueness and specificity of his articulation. If you go to the Library

of Congress and you look at his scores, you’re going to see all these

different modes and synthetic scales written underneath his

compositions. Some people are thinking, “Oh, he’s just playing free.”

Oh, no, not quite.

Both Eric and Messiaen…there’s like a shadow chasing them and they

have to keep moving; they have to keep pushing the bar. If Eric would

have lived to be 60 or 70, I can’t imagine what he would have been

doing.

How many people in the music that you and I love, start off with an

interval of three octaves and a half step? I’m talking about

“Gazzelloni.” There’s so much Monk in his music. Monk’s harmonic

voicings have a crystal clear clarity because of the way that he colors

rhythm by accents, syncopations and a wide range of touches to the

piano.

EI: When you mentioned that Messiaen voicing, I thought of Ellington and Monk.

It’s that same kind of specificity, that same kind of resonance.

It’s that same kind of specificity, that same kind of resonance.

JN: Oh let me tell you, you’re talking right on it.

Those are my cats because of that specificity, you know? And also, the

space of mind and heart to hear that specificity and run with it to

define the human condition in the way that only they could do!

I stopped doing this, but I used to ask composition students to stand

up and just say “I love you.” I’d have them yell it! Then I’d have them

say it a little lower than yelling…then I’d have them whisper it. I did

this to help them understand the change drastically in dynamics

dramatically impacts meaning. The Basie band could play at such a

whisper. The Ellington band could also perform at a whisper. That’s one

of the things that just floored me about the MJQ: I loved it when that

band played quietly with Milt hitting blues out of the park home runs.

The harmonic colors become so gigantic, and the groove was swingissimmo!

I wish we could have seen Eric pushing to the limit as an elder

statesman of the music. We did see Messiaen push himself to the limit

when he created his opera, Saint François d’Assise. I think it

took him six years to compose the music and two years for him and Yvonne

Loriod to write out the parts from the score. Now that is commitment.

Composing is not an art form that you can approach without realizing

that if you’re going to do great things, you’re going to have to bleed —

and you’re going to have to bleed a lot.

EI: I know you’ve paid some heavy dues, James. Tell me more about becoming a jazz flute player.

JN: My father loved Duke Ellington, and he loved

the blues; my mother loved spirituals and gospel music, so that’s what I

heard growing up. But I was also attracted to In a Silent Way, Bitches Brew, Live at the Fillmore,

that was the music that I listened to when I was in high school,

probably the music with which I was most obsessed. (I didn’t know at the

time how much Hendrix had impacted Miles, and so that’s another draw in

hearing the wah wah pedals and everything.) I bought Filles de Kilimanjaro,

and I wasn’t quite ready for it at first, but it didn’t take long

before I fell in love with it, so that was where I was coming from. I

was coming out of Weather Report’s first and second albums. I was coming

out of Mwandishi big time, when I heard them play at Donte’s in L.A.,

it was a life-changing experience. (There are two people in that band

I’m now really close to, Billy Hart and Bennie Maupin.) I had heard

Ornette a little bit, and I knew some of late Coltrane.

So the first day I’m spending time with Stanley Crouch and Arthur

Blythe I’m just in awe. Stanley had an incredible record collection: I’m

hearing King Oliver for the first time, I’m hearing Sun Ra in depth for

the first time.

The first time I heard Debussy’s La Mer was when Stanley played it for me…

EI: [laughs]

JN: Yeah, that’s a kind of funny story because people do not associate Stanley with Debussy, they always laugh at that.

This was also the first time I heard the music of the forest people

of central Africa. I became obsessive about that music because of its

inherent spirituality and deep beauty. I also found out Eric was into

it, and long before learning that this is music that drew Ligeti’s

attention and others. Eric and Trane were learning the beauty, mystery,

and deep intellectualism in the music and culture. I always thought that

this music was one of the reasons why Eric’s musical language utilizes

so much octave displacement. Of course, his music was also inspired by

Monk’s use of octave displacement.

The other crucial gift of that period was hearing Bobby Bradford talk

about the history of our music. Bradford is one of the most brilliant

scholars that I know. I put Bobby and Billy Hart in the category of

being teachers whose level of discourse is in the stars, with an ability

to break down so many different elements of music and culture in a

provocative and profound manner.

Bradford would talk about different articulations. He’d say,

“Man,

isn’t that funny, that opening phrase of ‘Half Nelson,’” and he’d give

you the articulation for it. All of these experiences impacted my flute

playing immensely.

Different people would come through Stanley’s house: John Carter, who

became a close friend, mentor, and collaborator. David Baker came

through playing rich, imminently melodic cello, which was a beautiful

experience. Mark Dresser’s teacher Bertram Turetzky came through, and we

played with him. His bow work was astounding, as was the rapport

between Burt and Mark! Butch Morris also came through playing cornet

(heavily influenced by Don Cherry) and bringing some beautiful

compositions.

I also just learned so much from Stanley during that period. He would

talk about literature a lot, and I was a sponge. I remember a time when

four of us were living in a house together in Pomona, David Murray,

Stanley, a lady by the name of Monica Pecot and myself. Outside of

working and going to school, it was, you know, nonstop creation.

Stanley was incredibly patient with me and gave me a lot of love. He

was a very important mentor for David, Mark, and me. When he said, “OK,

you can come back next week,” it was the most joyous thing to hear those

words.

I said I would bring my amplifier and my microphone. Stanley said,

“F– the microphone, F– the amplifier! You put some F–ing wind in that

flute!” And it started to make me think about having a big sound that

could project and stand up next to the alto, stand up next to the

trumpet (or Bobby was playing cornet) and have that kind of power. So

that was something I worked on extensively.

Like I said, to hear Bobby Bradford and Arthur go at it: OK, this is

what you have to begin to think about to construct a solo. Even though I

could not do it at the time, I began to understand that these were some

of the parameters about which I had to be thinking.

Eventually, they all moved to New York. I came a little later, and they all looked out for me.

EI: Of course, these New York years would prove

very fertile, there would be a lot of recording, a lot of projects, and a

couple of records that stuck out to me feature Abdul Wadud.

JN: Yeah, man!

EI: I think he’s kind of a special musician of

quite remarkable qualities. I thought maybe I could get you to talk

about Abdul Wadud a little bit.

JN: I LOVE ABDUL WADUD! Let me now tell you

something. Let’s go back to the blues. Wadud knew how to play the blues

and had a deep feeling for it. It’s like if you could imagine Robert

Johnson playing the cello, there it is, you know?

Then let’s go to another extreme: I remember when we did Anthony Davis’s piece, Still Waters, written for the trio, with the New York Philharmonic.

(We were all impacted by Toru Takemitsu’s music. Takemitsu wrote a

piece for Tashi and then created a second version with orchestra

entitled Quatrain. That was similar to what Anthony did: Still Waters could be for a trio or work with trio plus symphony orchestra.)

We were on the stage at Alice Tully Hall. We walked on the stage, and

the orchestra was like, “OK, who are these guys?” Almost always, when

you work with orchestras, you get to the point where you have to prove

something to them. There are very few times when you get the support you

need right away. You need to prove to them that you know what’s going

on, and you know how to navigate in that environment in a way that can

make the music can happen. OK, we started rehearsing a lot of written

passages with them, and after about 15 minutes into the rehearsal, the

principal cellist says, Mr. Wadud, could you please tell me the

fingering that you’re using for that particular phrase?” Then, it was

over. We had won! The orchestra could not believe the three of us. They

were like, “Who are these cats? How come we don’t know about them?”

If I had to pick five musicians that I have worked with in my life

where I cherished the experience of working with them, Wadud would

easily be on that list. He’d probably be in the top 3. He could work

with so many different composers; he is a composer himself, he is a

complete musician and so stylistically diverse and can articulate so

many different styles of music with full authority. And just a cat that

is so much fun to be around. I read something recently where he said,

“Anthony Davis and James, those are my boys!” Well, he’s our boy! I

could not imagine the cello doing what it was able to do in Abdul’s

hands and hear something else. In that trio we would push each other,

and some of the stuff that we demanded the other to play was close to

the edge of impossibility. The improvisation impacted the composition,

and there was a fluidity. There was almost exponential development with

that Trio. I still have in my mind a concert we did in Basel in the

early 80s. It was one of those nights where the music was almost

perfect. I can’t think of any other experience where I felt that was the

case. There was always this long list of things that I think each of us

felt we could have done a lot better, but these cats and what we had

together was special. And, I think the strongest component in that

equation was Abdul Wadud. I really do.

EI: I’ve Known Rivers is great, and if you

know this music, it’s known as a classic record. But another cut that

is special is the duo of you, “The Preacher and the Musician,” from Portraits, That’s

an extended composition that covers a lot of area and flute and cello,

it’s a vulnerable situation, but it’s a very compelling listen.

JN: Thank you, I appreciate that very much. I wrote

it for a preacher friend, Dwight Andrews, who did a lot of work with

some musicians like Wadada Leo Smith, Geri Allen, Jay Hoggard and many

others. He’s an amazing human being and a great inspiration

“The Preacher and the Musician” has a lot of different influences.

The swing sections reflect the influence of Monk, and at the end, I was

thinking about this incredible duo composition, The Jet Whistle

by Heitor Villa-Lobos, that was kind of mixing some of those Brazilian

elements with my compositional take on American blues and Brazilian

saudade. That’s the thing about Wadud; he was comfortable no matter what

diverse places you might go for inspiration.

He is a real master of the bow. The bow is connected to singing. Some

cellists can kind of be near Sarah Vaughan and her airstream, which

produces a dizzying array of subtle nuances and various speeds of

vibrati. I love that Tomeka Reid is moving the cello forward in the

younger generation with her enriching, distinctive style.

EI: There’s a lot of records from this era. We won’t be able to go through all of them right now, but I’ll keep listening of course.

Stanley was the voice for this scene; he wrote liner notes for you

and David Murray, and then perhaps there’s a change when the Marsalises

come in. I wasn’t there at the time, but it feels like that there was a

big shift of where the conversation was in terms of what was important

in the music.

JN: I always felt that there’s room for stylistic

multiplicity. People can develop in different directions. Not everybody

is going to be a Miles Davis. If we look historically, some great

artists have chosen a primary style and focus and stayed within the area

where they were once the innovators. I’ve always thought that that is

valid. Then there are people like Mary Lou Williams, Randy Weston,

Coleman Hawkins, who go through the different eras and embrace the

innovations that occur and are comfortable with them. We can think about

Max Roach, Eric Dolphy, and Coleman Hawkins playing together in the

60s, or Hawk and Sonny Rollins with Paul Bley, or Mary Lou Williams and

Cecil Taylor.

In the 80s, we have to look at what was occurring politically. There

have always been periods where things are really conservative or

unwelcoming to innovation. At one point there was a migration of

musicians, who were living in New York, moving to Copenhagen and other

cities to be able to survive and to develop their art. We know that

Tootie Heath, who we both love to the nth degree, also spent some time

there.

EI: Tootie told me directly that he felt like he couldn’t live in America anymore at that moment.

JN: Yeah. I know the feeling. There’s been a lot of

investment in trying to make this nation a better place, but this is a

very distorted period right now. I have my family here, and my roots are

here, but if it weren’t for those factors, I might have considered

making a change.

It is a shadow-filled period, but the Reagan era was a challenging

time also, and I think those challenges permeated an attack on the

innovative aspects of the art form.

In the first live Young Lions recording, there was a lot of

diversity. A lot of different musical styles coexisted, but I think what

happened is that fewer of the major press covered the avant-garde. I

can remember before the Young Lions concert, Newsweek magazine

printed a feature on David Murray, Anthony Davis, and me, with President

Kennedy on the cover. There were also things in Vanity Fair that would

crop up that would garner a lot of attention.

EI: Henry Threadgill did an ad for Dewar’s Scotch.

JN: Oh yeah, now we’re talking about one of the

great geniuses of the music. I heard Air when I first moved to New York

in 1978, I think it was February, Charlie’s Beefsteak House, I sat there

and listened to three sets, and I said, Well, maybe I need to go back

home to LA and practice another six months and then come back. I mean,

they scared me to death. The music was that great, and I felt like that

band was golden, and it should have flourished.

But people like Threadgill, Geri Allen, Anthony Davis, Jane Ira Bloom

and some other artists stated, “We are composers.” And that was part of

the difficulty. The focus in the early days with a lot of the more

conservative Young Lions was on playing standards. They did write their

own music, but …

EI: But not experimental music…

JN: …Not experimental music, and we were not ready

to let experimental music die on the vine because there’s a conservative

shift in what’s receiving attention. The good news during that period

was that you could work like crazy in Europe. There were 100s of

boutique jazz labels that afforded you the ability to document your

music. Over here, Bob Cummins of India Navigation and Jonathan M.P. Rose

of Gramavision displayed broad tastes, both paid royalties, and Rose

recorded the musicians at a very high technical level and did not sweat

on making sure that the music was documented in a very sophisticated

fashion…

…But what are you going to do? The shift occurred. I felt very

blessed, I felt very fortunate, and some other people were able to do

really well, but let’s talk about some of the pain because I think we do

have to address the pain. There were attacks on Anthony Braxton that I

would put in the category of being just downright cruel, and that

bothered me to no end. He is my friend, and his music has consistently

been a source of great inspiration. The environment became: either

you’re doing it like us, or it’s not happening. There was some

manipulation occurring. Being an artist of color is tough in this

society. Being an artist in society is difficult, to begin with, as is

the struggles that exist for women in the music. Women artists of color

have to face both the pervasive racism and the sexism that exists in our

society.

Marsalis’s critique of Braxton had an impact on Braxton’s livelihood

for a period. This is a man who had the responsibility of co-supporting

his family with his wife, Nickie. Braxton really broke new ground. We

need people that are on the front line taking chances; otherwise we