SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2017

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2017

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

DAVID MURRAY

(February 25--March 3)

OLIVER LAKE

(March 4–10)

GERALD WILSON

(March 11-17)

DON BYRON

(March 18-24)

KENNY GARRETT

(March 25-31)

COLEMAN HAWKINS

(April 1-7)

ELMORE JAMES

(April 8-14)

WES MONTGOMERY

(April 15-21)

FELA KUTI

(April 22-28)

OLIVER NELSON

(April 29-May 5)

SON HOUSE

(May 6-12)

JOHN LEE HOOKER

(May 13-19)

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/coleman-hawkins-mn0000776363/biography

Coleman Hawkins

(1904-1969)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

Coleman Hawkins

was the first important tenor saxophonist and he remains one of the

greatest of all time. A consistently modern improviser whose knowledge

of chords and harmonies was encyclopedic, Hawkins had a 40-year prime (1925-1965) during which he could hold his own with any competitor.

Coleman Hawkins started piano lessons when he was five, switched to cello at age seven, and two years later began on tenor. At a time when the saxophone was considered a novelty instrument, used in vaudeville and as a poor substitute for the trombone in marching bands, Hawkins sought to develop his own sound. A professional when he was 12, Hawkins was playing in a Kansas City theater pit band in 1921, when Mamie Smith hired him to play with her Jazz Hounds. Hawkins was with the blues singer until June 1923, making many records in a background role and he was occasionally heard on instrumentals. After leaving Smith, he freelanced around New York, played briefly with Wilbur Sweatman, and in August 1923 made his first recordings with Fletcher Henderson. When Henderson formed a permanent orchestra in January 1924, Hawkins was his star tenor.

Although (due largely to lack of competition) Coleman Hawkins was the top tenor in jazz in 1924, his staccato runs and use of slap-tonguing sound quite dated today. However, after Louis Armstrong joined Henderson later in the year, Hawkins learned from the cornetist's relaxed legato style and advanced quickly. By 1925, Hawkins was truly a major soloist, and the following year his solo on "Stampede" became influential. Hawk (who doubled in early years on clarinet and bass sax) would be with Fletcher Henderson's Orchestra up to 1934, and during this time he was the obvious pacesetter among tenors; Bud Freeman was about the only tenor who did not sound like a close relative of the hard-toned Hawkins. In addition to his solos with Henderson, Hawkins backed some blues singers, recorded with McKinney's Cotton Pickers, and, with Red McKenzie in 1929, he cut his first classic ballad statement on "One Hour."

By 1934, Coleman Hawkins had tired of the struggling Fletcher Henderson Orchestra and he moved to Europe, spending five years (1934-1939) overseas. He played at first with Jack Hylton's Orchestra in England, and then freelanced throughout the continent. His most famous recording from this period was a 1937 date with Benny Carter, Alix Combille, Andre Ekyan, Django Reinhardt, and Stephane Grappelli that resulted in classic renditions of "Crazy Rhythm" and "Honeysuckle Rose." With World War II coming close, Hawkins returned to the U.S. in 1939. Although Lester Young had emerged with a totally new style on tenor, Hawkins showed that he was still a dominant force by winning a few heated jam sessions. His recording of "Body and Soul" that year became his most famous record. In 1940, he led a big band that failed to catch on, so Hawkins broke it up and became a fixture on 52nd Street. Some of his finest recordings were cut during the first half of the 1940s, including a stunning quartet version of "The Man I Love." Although he was already a 20-year veteran, Hawkins encouraged the younger bop-oriented musicians and did not need to adjust his harmonically advanced style in order to play with them. He used Thelonious Monk in his 1944 quartet; led the first official bop record session (which included Dizzy Gillespie and Don Byas); had Oscar Pettiford, Miles Davis, and Max Roach as sidemen early in their careers; toured in California with a sextet featuring Howard McGhee; and in 1946, utilized J.J. Johnson and Fats Navarro on record dates. Hawkins toured with Jazz at the Philharmonic several times during 1946-1950, visited Europe on a few occasions, and in 1948 recorded the first unaccompanied saxophone solo, "Picasso."

By the early '50s, the Lester Young-influenced Four Brothers sound had become a much greater influence on young tenors than Hawkins' style, and he was considered by some to be out of fashion. However, Hawkins kept on working and occasionally recording, and by the mid-'50s was experiencing a renaissance. The up-and-coming Sonny Rollins considered Hawkins his main influence, Hawk started teaming up regularly with Roy Eldridge in an exciting quintet (their appearance at the 1957 Newport Jazz Festival was notable), and he proved to still be in his prime. Coleman Hawkins appeared in a wide variety of settings, from Red Allen's heated Dixieland band at the Metropole and leading a bop date featuring Idrees Sulieman and J.J. Johnson, to guest appearances on records that included Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, and (in the early '60s) Max Roach and Eric Dolphy. During the first half of the 1960s, Coleman Hawkins had an opportunity to record with Duke Ellington, collaborated on one somewhat eccentric session with Sonny Rollins, and even did a bossa nova album. By 1965, Hawkins was even showing the influence of John Coltrane in his explorative flights and seemed ageless.

Unfortunately, 1965 was Coleman Hawkins' last good year. Whether it was senility or frustration, Hawkins began to lose interest in life. He practically quit eating, increased his drinking, and quickly wasted away. Other than a surprisingly effective appearance with Jazz at the Philharmonic in early 1969, very little of Hawkins' work during his final three and a half years (a period during which he largely stopped recording) is up to the level one would expect from the great master. However, there are dozens of superb Coleman Hawkins recordings currently available and, as Eddie Jefferson said in his vocalese version of "Body and Soul," "he was the king of the saxophone."

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/colemanhawkins

Coleman Hawkins started piano lessons when he was five, switched to cello at age seven, and two years later began on tenor. At a time when the saxophone was considered a novelty instrument, used in vaudeville and as a poor substitute for the trombone in marching bands, Hawkins sought to develop his own sound. A professional when he was 12, Hawkins was playing in a Kansas City theater pit band in 1921, when Mamie Smith hired him to play with her Jazz Hounds. Hawkins was with the blues singer until June 1923, making many records in a background role and he was occasionally heard on instrumentals. After leaving Smith, he freelanced around New York, played briefly with Wilbur Sweatman, and in August 1923 made his first recordings with Fletcher Henderson. When Henderson formed a permanent orchestra in January 1924, Hawkins was his star tenor.

Although (due largely to lack of competition) Coleman Hawkins was the top tenor in jazz in 1924, his staccato runs and use of slap-tonguing sound quite dated today. However, after Louis Armstrong joined Henderson later in the year, Hawkins learned from the cornetist's relaxed legato style and advanced quickly. By 1925, Hawkins was truly a major soloist, and the following year his solo on "Stampede" became influential. Hawk (who doubled in early years on clarinet and bass sax) would be with Fletcher Henderson's Orchestra up to 1934, and during this time he was the obvious pacesetter among tenors; Bud Freeman was about the only tenor who did not sound like a close relative of the hard-toned Hawkins. In addition to his solos with Henderson, Hawkins backed some blues singers, recorded with McKinney's Cotton Pickers, and, with Red McKenzie in 1929, he cut his first classic ballad statement on "One Hour."

By 1934, Coleman Hawkins had tired of the struggling Fletcher Henderson Orchestra and he moved to Europe, spending five years (1934-1939) overseas. He played at first with Jack Hylton's Orchestra in England, and then freelanced throughout the continent. His most famous recording from this period was a 1937 date with Benny Carter, Alix Combille, Andre Ekyan, Django Reinhardt, and Stephane Grappelli that resulted in classic renditions of "Crazy Rhythm" and "Honeysuckle Rose." With World War II coming close, Hawkins returned to the U.S. in 1939. Although Lester Young had emerged with a totally new style on tenor, Hawkins showed that he was still a dominant force by winning a few heated jam sessions. His recording of "Body and Soul" that year became his most famous record. In 1940, he led a big band that failed to catch on, so Hawkins broke it up and became a fixture on 52nd Street. Some of his finest recordings were cut during the first half of the 1940s, including a stunning quartet version of "The Man I Love." Although he was already a 20-year veteran, Hawkins encouraged the younger bop-oriented musicians and did not need to adjust his harmonically advanced style in order to play with them. He used Thelonious Monk in his 1944 quartet; led the first official bop record session (which included Dizzy Gillespie and Don Byas); had Oscar Pettiford, Miles Davis, and Max Roach as sidemen early in their careers; toured in California with a sextet featuring Howard McGhee; and in 1946, utilized J.J. Johnson and Fats Navarro on record dates. Hawkins toured with Jazz at the Philharmonic several times during 1946-1950, visited Europe on a few occasions, and in 1948 recorded the first unaccompanied saxophone solo, "Picasso."

By the early '50s, the Lester Young-influenced Four Brothers sound had become a much greater influence on young tenors than Hawkins' style, and he was considered by some to be out of fashion. However, Hawkins kept on working and occasionally recording, and by the mid-'50s was experiencing a renaissance. The up-and-coming Sonny Rollins considered Hawkins his main influence, Hawk started teaming up regularly with Roy Eldridge in an exciting quintet (their appearance at the 1957 Newport Jazz Festival was notable), and he proved to still be in his prime. Coleman Hawkins appeared in a wide variety of settings, from Red Allen's heated Dixieland band at the Metropole and leading a bop date featuring Idrees Sulieman and J.J. Johnson, to guest appearances on records that included Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, and (in the early '60s) Max Roach and Eric Dolphy. During the first half of the 1960s, Coleman Hawkins had an opportunity to record with Duke Ellington, collaborated on one somewhat eccentric session with Sonny Rollins, and even did a bossa nova album. By 1965, Hawkins was even showing the influence of John Coltrane in his explorative flights and seemed ageless.

Unfortunately, 1965 was Coleman Hawkins' last good year. Whether it was senility or frustration, Hawkins began to lose interest in life. He practically quit eating, increased his drinking, and quickly wasted away. Other than a surprisingly effective appearance with Jazz at the Philharmonic in early 1969, very little of Hawkins' work during his final three and a half years (a period during which he largely stopped recording) is up to the level one would expect from the great master. However, there are dozens of superb Coleman Hawkins recordings currently available and, as Eddie Jefferson said in his vocalese version of "Body and Soul," "he was the king of the saxophone."

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/colemanhawkins

Coleman Hawkins

Coleman Hawkins single-handedly brought the saxophone to the prominence in jazz that the instrument enjoys. Before he hit the scene, jazz groups had little use for the instrument. One player (forgot who) said, “with all due respect to Adolph Sax, Coleman Hawkins invented the saxophone.” Hawkins, or “Bean”, as he was known as, started playing cello at a young age before switching to the saxophone. He was a lifelong listener of classical music, and as a result, his knowledge of music theory was far ahead of his peers. Whereas Louis Armstrong improvised his solos based on the melody, Hawkins based his on the harmony and had a strong sense of rhythm.

Hawkins hit New York at the age of 20 and quickly established himself, as he became the star of the Fletcher Henderson band. His mature style (both fast and slow) emerged in 1929, and Hawkins has been credited by some to have invented the Jazz ballad. He left Henderson's band in 1934 and headed for Europe. He returned in 1939 and recorded his commercial and artistic masterpiece Body and Soul, and established himself, once again, as one of the pre-eminent soloist. The song features one of the greatest saxophone solos ever and is the standard by which all other jazz ballads are measured.

He fronted his own big band until 1941, and then went back to the New York clubs and the small group surroundings. When bebop hit the scene in the early 40s, Hawkins was one of its early supporters and in 1944, he led the first bebop recording, featuring Dizzy Gillespie and Max Roach. Bebop upset many older musicians, but Hawkins was sympathetic because he understood it. He hired young sidemen, such as Fats Navarro, Thelonious Monk, and Howard McGhee, which further identified him with the movement. In the 1940s, he toured with Norman Granz's “Jazz at the Philharmonic” concerts, all the way into 1967. His music remained strong, as did his tone, which was also very strong and large. A young tenor sax player complained once to another tenor player (in the 1950s, when Hawkins was around 50 years old) that playing next to Coleman Hawkins frightened him. The other player responded with, “Coleman Hawkins is supposed to frighten you.”

Toward the end of his life, he neglected his health and drank much more. This robbed him of his “wind”, and he couldn't play the long, flowing solos that he had established earlier in his life, but he could still summon up the magic. He died in 1969.

Coleman Hawkins

Biography

Synopsis

Born in St. Joseph, Missouri, on November 21, 1904, Coleman Hawkins learned how to play the piano at age 5, the cello at 7, and the tenor sax at age 9. Chiefly known for his association with swing music and the big band era, Hawkins toured the world with various bands and had a role in the development of bebop, recording what is considered the first record of the genre in 1944.

Early Life

Coleman Hawkins was born in St. Joseph, Missouri, in 1904, and his mother began teaching him how to play piano when he was just 5 years old. He started playing the cello around age 7 and tenor saxophone at age 9. He attended high school in Chicago and then went to Washburn College in Topeka, Kansas, studying harmony and composition.

Career

The spring of 1921 marked Hawkins’ first professional gig—playing in the orchestra of the 12th Street Theater in Kansas City. By March 1922, Hawkins was working with Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds in New York, making his first recordings with her shortly thereafter. The year 1923 was a busy one for Hawkins, as he toured with the Jazz Hounds across the country, recorded his first substantial solo (on “Dicty Blues”) and teamed up with musicians such as Fletcher Henderson (with whom Hawkins formed a band that stuck together until 1934), Ginger Jones and Charlie Gaines on studio recordings and live shows.

The remainder of the 1920s and early 1930s found Hawkins and Henderson playing in and around New York City together, at venues such as the Roseland Ballroom and the Savoy. They also toured throughout New England, the East Coast, the Midwest and later the South. By 1934, Hawkins was the featured member of the group, and he set out on his own, touring the country with various local backup bands. He also toured Europe in Jack Hylton’s band in 1934 and, finding success there, toured with the Ramblers the next year. Hawkins’ travels took him from The Hague to Paris to Zurich and beyond as he toured Europe as a solo performer until 1939.

Hawkins returned to the United States in the summer of 1939 and by the fall had recorded “Body and Soul,” which introduced him to a wide American audience and was a huge success for Hawkins (so much so, in fact, that readers of DownBeat magazine voted Hawkins best tenor saxophonist of the year). For the next several years, Hawkins toured the United States with various bands, either his or those formed by other musicians, made studio recordings and returned to Europe for tours in 1948, 1949, 1950 and 1954.

Later Life and Legacy

During the late 1950s, he continued to appear at major jazz festivals and recorded prolifically, and when the 1960s rolled around, Hawkins could be found making film and television appearances and performing at New York’s Village Gate and Village Vanguard with his quartet. By the mid-1960s, however, Coleman Hawkins was seriously affected by alcoholism and general ill health, collapsing a few times onstage

His last concert was on April 20, 1969, at the North Park Hotel in Chicago, and he died just a month later from pneumonia. He is remembered as one of the originators of the bebop style (with Dizzy Gillespie and Max Roach) and as a huge influence to jazz giants such as Lester Young and Miles Davis.

Early Life

Coleman Hawkins was born in St. Joseph, Missouri, in 1904, and his mother began teaching him how to play piano when he was just 5 years old. He started playing the cello around age 7 and tenor saxophone at age 9. He attended high school in Chicago and then went to Washburn College in Topeka, Kansas, studying harmony and composition.

Career

The spring of 1921 marked Hawkins’ first professional gig—playing in the orchestra of the 12th Street Theater in Kansas City. By March 1922, Hawkins was working with Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds in New York, making his first recordings with her shortly thereafter. The year 1923 was a busy one for Hawkins, as he toured with the Jazz Hounds across the country, recorded his first substantial solo (on “Dicty Blues”) and teamed up with musicians such as Fletcher Henderson (with whom Hawkins formed a band that stuck together until 1934), Ginger Jones and Charlie Gaines on studio recordings and live shows.

The remainder of the 1920s and early 1930s found Hawkins and Henderson playing in and around New York City together, at venues such as the Roseland Ballroom and the Savoy. They also toured throughout New England, the East Coast, the Midwest and later the South. By 1934, Hawkins was the featured member of the group, and he set out on his own, touring the country with various local backup bands. He also toured Europe in Jack Hylton’s band in 1934 and, finding success there, toured with the Ramblers the next year. Hawkins’ travels took him from The Hague to Paris to Zurich and beyond as he toured Europe as a solo performer until 1939.

Hawkins returned to the United States in the summer of 1939 and by the fall had recorded “Body and Soul,” which introduced him to a wide American audience and was a huge success for Hawkins (so much so, in fact, that readers of DownBeat magazine voted Hawkins best tenor saxophonist of the year). For the next several years, Hawkins toured the United States with various bands, either his or those formed by other musicians, made studio recordings and returned to Europe for tours in 1948, 1949, 1950 and 1954.

Later Life and Legacy

During the late 1950s, he continued to appear at major jazz festivals and recorded prolifically, and when the 1960s rolled around, Hawkins could be found making film and television appearances and performing at New York’s Village Gate and Village Vanguard with his quartet. By the mid-1960s, however, Coleman Hawkins was seriously affected by alcoholism and general ill health, collapsing a few times onstage

His last concert was on April 20, 1969, at the North Park Hotel in Chicago, and he died just a month later from pneumonia. He is remembered as one of the originators of the bebop style (with Dizzy Gillespie and Max Roach) and as a huge influence to jazz giants such as Lester Young and Miles Davis.

by Len Weinstock

As Jazz evolves, tastes in instruments also change. For example, while there were dozens of brilliant clarinet players in the Classic Jazz and Swing periods, the instrument has all but faded from the scene in the Bop Era. The tenor sax, on the other hand, rose from mere comic novelty status in the 1920's to a principal spot in the front lines of most modern Jazz combos. Jazz, as Joachime Berendt stated, has been tenorized.

From the Classic Jazz period to the Swing Era one player had a virual monopoly on the tenor sax, that man being Coleman Hawkins, a.k.a., the Hawk or the Bean. Hawkins (born 1904, St. Joseph, Mo.) was not the first Jazzman to play the tenor but he was the leader in transforming it into a fully expressive, hard driving Jazz instrument. Following a ten year period of getting the hang of that confounded contraption, the Hawk went on to a fifty year career filled with near flawless playing as leader of his own groups as well as with an amazing variety of other combos. He was an inspiration to dozens of top notch Jazz tenor men.

Mamie Smith and her Jazz Hounds 1922.

Left to right: unknown, Bubber Miley,unknown, unknown, Mamie Smith, Coleman Hawkins, unknown, unknown Hawkins career started as a sideman with Mamie Smith's Jazz Hounds (C.1920-1923) and continued to develop as a featured soloist with Fletcher Henderson's Orchestra (1923-1934). Recordings of his early work with Henderson shows little promise of greatness that was to follow in later years. Although he was considered avant-garde at the time, he employed a slap-tongue style that was closer to vaudeville than Jazz. After Louis Armstrong's tenure with the band ( 1924- 1925) things started to improve rapidly, however. With Louis as an example, Hawkins learned to swing and to phrase like a Jazzman in a matter of two years. Indeed, Louis even transformed the entire Henderson Orchestra from a tight, ricky-ticky novelty band into a hard-swinging Jazz unit.

Hawkin's technique and style continued to develop and by 1933 he had already mastered two important Jazz tenor styles: the hard-driving explosive riff and the smooth flowing ballad form. It was also in 1933 that Hawkins encountered the first real threat to his monopoly of the tenor sax. Late in that year he played with Chu Berry and, during a December stand of the Henderson band in Kansas City, Hawkins got the shock of his life on meeting local players Lester Young, Ben Webster and Hershel Evans. Hawkins had a "cut session" with these early masters of the sax at dawn at a place called the Cherry Blossom Club. The entire musical community of KC showed up for this session! According to earwittness accounts by Mary Lou Williams and Jo Jones, Lester Young got the best of it. The Hawk had finally met a formidable rival !

It may not have been entirely a coincidence that soon after returning to New York from this trip to the Middle West, the Hawk decided to move to England. The official reason usually given is that Hawk was growing restless after ten years with Henderson. Early in March of 1934 he telegraphed popular bandleader Jack Hylton simply stating "I want to come to England". The next day Hylton wired an offer to Hawkins and on March 23 he sailed for England on the Ile de France. Hawkins had once again become the center of attention and the only tenor in town. He was idolized and treated like visiting royalty by the British and Continental Jazz Intelligentsia.

During his five year stay in Europe Hawkins had the opportunity to play and record with all of the prominent European Jazzmen like members of the Hot Club of France , Django Reinhart and Stéphane Grappelli, the Ramblers of Holland as well as other American visitors and expatriots, Benny Carter, Joe Coleman and Arthur Briggs. The circumstances surrounding these encounters were not always entirely pleasant. On some occasions, Hylton would take his band on tours of Hitler's Germany. Much to Hylton's discredit and much to the disappointment of the German Jazz fans, he would strand Hawkins at the border when Hawk was refused entry on racial grounds. It was during some of these periods when Hawk, on his own, played and recorded with the prominent European Jazzmen in France and Holland. Germany's loss was our gain.

Just before Hitler attacked Poland, Hawk returned to the United States in July 1939 to find that there were plenty of contenders to his tenor crown. There was not only Chu Berry, Don Byas, and Ben Webster, all of whom were plainly Hawkins followers but also one of his former musical adversaries from Kansas City, Lester Young, who had by now refined a whole new tenor style. Hawkins and Young were musical opposites. The Hawk was mainly a vertical improvisor who liked to run the chord changes. He used a full tone and rich vibrato as he played with strong on -the -beat intensity. Young employed a horizontal style and worked mainly with the melodic line using an airy alto-like, vibrato-free tone as he floated above the beat. The battle lines for tenor dominance were well defined.

The story goes that Hawk recorded his magnum opus Body and Soul in October, 1939 as an intentional move to reclaim his tenor crown. Such was not the case, however. The recording was made simply to use up some available studio time following a rather humdrum session. Hawkins himself didn't think there was anything outstanding about his Body and Soul saying "it was nothing special, just an encore I use in the clubs to get off the stand. I thought nothing of it and didn't even bother to listen to it afterwards". But the solo, two choruses of beautifully conceived and perfecly balanced improvisation, caused an immediate sensation with musicians and the public. It is still the standard to which tenorists aspire. A parallel can be drawn between Hawkins' Body and Soul and Lincoln's Gettysburg Address . Both were brief, lucid, eloquent and timeless masterpieces, yet tossed off by their authors as as mere ephemera.

As the modern Jazz era unfolded, Hawkin's style remained firmly entrenched with players like Ben Webster and Don Byas. Lester Young's style, however, had a greater influence than Hawk's on progressive players like Charlie Parker and Dexter Gordon and on the group of Cool players that followed, Stan Getz, Zoot Sims, Al Cohn and many others. Hawkins had no problem with the idea of Bop, however, even though he never actually played it. He had long been in the habit of absorbing everything musical that came his way. Hawk not only encouraged many young modernists but as early as 1944 hired many of the young revolutionaries like Thelonious Monk, Max Roach and Dizzy Gillespie. Hawkins was the leader on record dates of some of the earliest Bop experiments. This was in sharp contrast to the attitudes toward Bop of most other older musicians like Louis Armstrong and Benny Goodman. They shunned the new music and were even belligerent toward it. Armstrong, for example called Bop "Chinese music", revealing a marked lack of understanding.

From the mid 1940's through the 1950's Hawk's influence as a major Jazz soloist diminished, though his playing remained at a high level and he comfortably co-existed with the changing musical scene. He even lived to see his original style regain prominence in the late 1950's in the work of Sonny Rollins and Rollins' disciple, John Coltrane. Even as Hawkins aged, he continued to be an awe inspiring figure to young tenor players right to his last days in 1969. He could be musically intimidating as well. During a session, a young modernist once said of Hawk aside to one of his older colleagues " He scares me, man ! ". The answer: "He's supposed to scare you. That's what he's there for".

Hawkins was not only a pioneer on his instrument who set the stage for all he others. He belongs in the Pantheon of Jazz soloists together with Armstrong, Beiderbecke, Parker, Bechet and Young.

May 20, 1969

OBITUARY

Coleman Hawkins, Tenor Saxophonist, Is Dead

by JOHN S. WILSON

New York Times

New York Times

Coleman Hawkins, the tenor saxophonist who, with such musicians as Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Jelly Roll Morton, was one of the pioneer shapers of Jazz, died yesterday at Wickersham Hospital. Mr. Hawkins, who suffered from a liver ailment, was 64 years old. He lived at 445 West 153d Street.

During Mr. Hawkins's career, which spanned almost half a century, he created the first valid jazz style on the tenor saxophone, influenced countless saxophonists and was in the vanguard of jazz development.

There were saxophonists in jazz bands before Mr. Hawkins began to develop his manner of playing in the mid-1920's. But they were using a slap-tongue effect, which resulted in a chickenlike sound, reflecting the prevalent feeling that the saxophone was essentially a comic instrument. Mr. Hawkins, who had been using this technique himself, found and developed resources in the saxophone while he was in Fletcher Henderson's Orchestra at Roseland Ballroom between 1924 and 1927.

He used a big tone and a heavy vibrato. His swaggering attack drove along relentlessly through intensely rhythmic, choppy phrases.

Developing the Sound

During Mr. Hawkins's career, which spanned almost half a century, he created the first valid jazz style on the tenor saxophone, influenced countless saxophonists and was in the vanguard of jazz development.

There were saxophonists in jazz bands before Mr. Hawkins began to develop his manner of playing in the mid-1920's. But they were using a slap-tongue effect, which resulted in a chickenlike sound, reflecting the prevalent feeling that the saxophone was essentially a comic instrument. Mr. Hawkins, who had been using this technique himself, found and developed resources in the saxophone while he was in Fletcher Henderson's Orchestra at Roseland Ballroom between 1924 and 1927.

He used a big tone and a heavy vibrato. His swaggering attack drove along relentlessly through intensely rhythmic, choppy phrases.

Developing the Sound

"I always did play with a kind of stiff reed," he said in explaining the basis of his early style. "When I started, I also used to play very loud because I was trying to play over seven or eight other horns all the time. I used to work on those reeds all night to make them sound. Having to play loud developed the fullness of my sound."

The power with which Mr. Hawkins played his saxophone was vividly recalled by Rex Stewart, the cornetist, who once received an emergency call to fill in with the Henderson band after two trumpet players were injured in an accident. One of those injured was the first trumpet. En route to the job, Mr. Stewart wondered who had been called in to play the first trumpet part.

"On arrival," Mr. Stewart said, "we set up and, much to my surprise, Coleman--on tenor-- took over the first-trumpet book and not only played the parts so well that we scarcely missed the first trumpet but also carried the orchestra with volume such as I had never heard coming out of a tenor sax."

Many of the saxophonists who were initially influenced by Mr. Hawkins during this period never went beyond that influence. Mr. Hawkins, however, continued to develop.

In 1939 he made a recording of "Body and Soul" that still stands as a classic model of welding grace and strength in a jazz ballad. And in the 1950's, he removed some of the earlier heaviness from his tone and used silence as an element in his solos along with rough ascending and descending runs.

Emergence of Emotion

"He got wilder and wilder," wrote Whitney Balliett in The New Yorker, "like an aging conservative who dons sneakers and a sports jacket for lunch at the Plaza. For the first time, the emotion beneath the surface of his solos became steadily visible and once in a while it backed up and burst through."

In recent years, Mr. Hawkins grew a long, gray patriarchal beard. Shuffling out on the stage in a grandfatherly manner, he gave the impression that he could scarcely hold up his saxophone. The first few tentative sounds he blew seemed to confirm that. Then, as his solo began to develop, he appeared to grow in stature as the notes he produced gained in authority and his performance took on the power and individuality that had always characterized his work.

"The older he gets, the better he gets," said Johnny Hodges, the alto saxophonist in Duke Ellington's Orchestra. "If you ever think he's through, you find he's just gone right on ahead again."

Mr. Hawkins was born in St. Joseph, Mo., on Nov. 21, 1904. His mother, an organist, started teaching him piano when he was 5. At 7, he was studying cello and when he was 9 he got a saxophone. He studied harmony, counterpoint and composition at Washburn College in Topeka, Kan., and at 17, he joined Mamie Smith's Jazz Hounds, a group that accompanied Miss Smith, a vaudeville singer, at the 12th Street Theater in Kansas City.

Garvin Bushell, a clarinetist in that band, had a vivid initial impression of Mr. Hawkins. "He was ahead of everything I'd ever heard on the instrument," said Mr. Bushell, adding:

"He read everything. And he didn't--as was the custom then--play the saxophone like a trumpet or a clarinet. He was running changes because he'd studied the piano as a youngster."

Mr. Hawkins reached New York with the Jazz Hounds in 1922 and made his first recording then with Miss Smith. Fletcher Henderson heard him playing at jam sessions, used him on several recordings accompanying blues singers and added him to the band that he took into the Club Alabam in 1923. Mr. Hawkins remained with the Henderson band for 11 years, playing most of the time at the Roseland Ballroom. He worked constantly on his style and technique.

Copied Honky Tonks' Style

"Maybe the rest of the fellows would be out looking for kicks or something," he said, "and I'd be in the honky-tonk joints, listening to the musicians, and I'd hear things I'd like and they'd penetrate and I'd keep them. If I hear something I like, I don't go home and get out my horn and try to play it. I just incorporate it within the things I play already, in my own style."

In 1934, learning that his fame had spread to Europe, Mr. Hawkins impulsively sent a cablegram to Jack Hylton, a bandleader who was the English equivalent of Paul Whiteman. The full message was "I am interested in coming to London."

Mr. Hylton responded the next day and within a week Mr. Hawkins was on the Ile de France. The saxophonist toured in England, France and the Netherlands, and when the threat of World War II developed in 1939, he with several other American jazz musicians, returned to the United States.

While he had been overseas, Lester Young's style of playing tenor saxophone--lighter in tone than Mr. Hawkins's and more concerned with linear improvisations--had caught the fancy of young jazz musicians who now considered Mr. Hawkins's style as dated. However, Mr. Hawkins quickly reasserted his dominance with his recording of "Body and Soul."

"I never thought of 'Body and Soul' seriously as being anything big for me," Mr. Hawkins said years after making the recording.

"I'd used it occasionally as an encore, something to get off the stage with. And at Kelly's Stable"--a jazz club on 51st Street where Mr. Hawkins was leading a combo after his return from Europe--"sometimes at night, after a couple of quarts of scotch, very late, I'd sit down and kill time and play about 10 choruses on it, and then the boys would come in and play harmony notes in the background while I finished it up. That's all there was to it."

Mr. Hawkins recorded the tune only as a favor to Leonard Joy, who produced his recording sessions. It became such a hit that he had to play it at almost every appearance for the next 15 years.

Although most jazz musicians of Mr. Hawkins's generation resisted the harmonic and rhythmic approaches that developed in jazz in the 1940's and that became known as bebop, Mr. Hawkins welcomed them. In 1944 he made what is considered to be first bop record "Woody 'n' You," with a group that included Dizzy Gillespie, Max Roach and Oscar Pettiford.

For the last 25 years, Mr. Hawkins performed most of the time as a single, playing with whatever rhythm section was available for accompaniment.

Writing in Downbeat magazine in 1950, Michael Levin summed up Mr. Hawkins's past as of that date and accurately projected his future.

Keeping Up With the Times

"Despite all of the amazing elements of his personal style," Mr. Levin wrote, "the most fascinating thing about Hawkins as a musician is the way he has changed with the times, moved with music, and never allowed himself to become dated.

"In the final analysis, this can only be charged off to his completely cold and observant mind when it comes to music, his ability to remain disentangled from emotional arguments about styles and modes of playing, and his genuine interest in constantly making himself a better musician."

Mr. Hawkins is survived by his widow, Dolores; a son, Rene, and two daughters, Colette and Mrs. Melvin Wright.

A funeral service will be held on Friday at 2 P.M. at St. Peter's Lutheran Church, Lexington Avenue and 54th Street.

Coleman Hawkins

Coleman Hawkins, in full Coleman Randolph Hawkins (born November 21, 1904, St. Joseph, Mo., U.S.—died May 19, 1969, New York, N.Y.), American jazz musician whose improvisational mastery of the tenor saxophone,

which had previously been viewed as little more than a novelty, helped

establish it as one of the most popular instruments in jazz. He was the

first major saxophonist in the history of jazz.

At age four Hawkins began to study the piano, at seven the cello, and at nine the saxophone. He became a professional musician in his teens, and, while playing with Fletcher Henderson’s

big band between 1923 and 1934, he reached his artistic maturity and

became acknowledged as one of the great jazz artists. He left the band

to tour Europe for five years and then crowned his return to the United States in 1939 by recording the hit “Body and Soul,” an outpouring of irregular, double-timed melodies that became one of the most imitated of all jazz solos.

Hawkins

was one of the first jazz horn players with a full understanding of

intricate chord progressions, and he influenced many of the great

saxophonists of the swing era (notably Ben Webster and Chu Berry) as well as such leading figures of modern jazz as Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane. Hawkins’s deep, full-bodied tone and quick vibrato were the expected style on jazz tenor until the advent of Lester Young,

and even after Young’s appearance many players continued to absorb

Hawkins’s approach. One of the strongest improvisers in jazz history,

Hawkins delivered harmonically complex lines with an urgency and

authority that demanded the listener’s attention. He was also a noted

ballad player who could create arpeggiated, rhapsodic lines with an intimate tenderness that contrasted with his gruff attack and aggressive energy at faster tempos.

Hawkins

gave inspired performances for decades, managing to convey fire in his

work long after his youth. From the 1940s on he led small groups,

recording frequently and playing widely in the United States and Europe

with Jazz at the Philharmonic and other tours. He willingly embraced the

changes that occurred in jazz over the years, playing with Dizzy Gillespie and Max Roach in what were apparently the earliest bebop

recordings (1944). In time he also became an outstanding blues

improviser, with harsh low notes that revealed a new ferocity in his

art. Despite alcoholism and ill health, he continued playing until

shortly before his death in 1969.

William Gottlieb/The Library Of Congress

When tenor saxophonist John Coltrane recorded his composition

"Giant Steps" in 1959, he created something that changed the way

musicians thought about improvisation and harmony. Decades earlier, the

man who took the first leaps and bounds with the tenor sax in jazz was Coleman Hawkins.

Before Hawkins arrived on the jazz scene with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra in the 1920s, the tenor sax was basically an ensemble instrument — as opposed to a improvisational instrument — mainly providing a link between the clarinets and brass instruments in military bands and big bands. Hawkins had different ideas, and through his virtuosic playing, he put the instrument front and center in the development of jazz. Hawkins' approach to music would later serve as a bridge from the era of big band swing to later developments like bebop.

Put simply, Hawkins was a musical pioneer, one of the most versatile and accomplished soloists in jazz history. Here are five samples of his genius.

As Hawkins gained fame with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra, he began to get invitations to record with other musicians. Here's a 1929 session featuring Hawkins with the Mound City Blue Blowers, which was essentially a project of Red McKenzie, whose specialty was playing a comb covered in tissue paper. Perhaps to help legitimize his rather remarkable comb playing, he invited great jazz players to accompany him. On this recording, in addition to Hawkins, we hear Pee Wee Russell (clarinet), Gene Krupa (drums), Eddie Condon (banjo) and Glenn Miller (trombone). Before Hawkins, a tenor sax solo was a novelty; on this song we hear him taking his instrument out of vaudeville and into the future.

Picasso

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/coleman-hawkins-by-henk-de-boer.php

Although Adolphe Sax actually invented the saxophone, in the jazz world the title "Father of the Tenor Saxophone" became justly associated with Coleman Hawkins (1904-1969), not only an inventive jazz giant but also the founder of a whole dynasty of saxophone players. Before Hawkins, the saxophone (itself "born" in 1846) was mainly a favorite in marching bands and something of a novelty instrument in circus acts and vaudeville shows. Indeed, at age 16, Coleman started out with such a vaudeville group, Mamie Smith and her Jazz Hounds.

Even at 16 he garnered admiration for his ability to sight read and impressive musicianship. He started with the C-melody sax, which he soon traded for the more robust tenor, while also doubling on clarinet, baritone and even bass saxophone. Much more important was his 1923 engagement with the then famous Fletcher Henderson Band, of which also Louis Armstrong became a member (there is little doubt that Hawkins became influenced by his playing style). Here his talent ripened and ultimately grew too big for the somewhat stagnating opportunities the band offered him.

In 1933, Hawkins left Henderson to sail to England where he had a stint with the celebrated Jack Hylton Orchestra. For five years he toured the continent and more or less settled in Holland. Everywhere he played he was met with great enthusiasm, but for himself this was foremost a period of consolidation and further ripening. In 1939, he returned to the US and in that same year made an everlasting impression with his tender masterpiece "Body and Soul." "The Hawk" was fully back on the scene and maintained his grip until shortly before his untimely death in 1969.

Hawkins' personality and attitude were competitive and at times aggressive. He welcomed any opportunity to duel with other horn players, like his famous 1939 contest with his main opponent, Lester Young. Always aspiring to win, his playing was full of drive and rarely relaxed. Still, he made harmonious records with Benny Carter, Ben Webster and especially trumpeter Roy Eldridge. Due to his unique ability to adapt his playing style to new musical concepts, he made smooth transitions into bebop and cool jazz in the 40's, resulting in a comfortable collaboration with younger jazz pioneers.

Ken Burns Jazz

Coleman Hawkins

(Verve, 2000)

This compilation is a spin-off of the PBS production Ken Burns Jazz. It highlights nineteen significant recordings from "The Stampede" with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra in 1926 to his 1962 date with Ellington and as such represents an excellent overview for first timers.

Coleman Hawkins

A Retrospective 1929-1963

(RCA 1995)

Extensive 2 CD overview: 34 years of Hawkins' recordings for the Victor associated labels. This includes the early classics "One Hour" and "Hello Lola" with Red McKenzie on comb as well as the whole original 1939 session that originated "Body and Soul" up to the sixties.

Coleman Hawkins

The Body and Soul of the Saxophone

(ASV 2000)

A sound overview from 1929 to 1948 in 23 characteristic pieces on one CD, ranging from the early McKenzie recordings and "Body and Soul" to the renowned solo piece "Picasso."

Coleman Hawkins

The Bebop Years

(Proper 2001)

This affordable 4 CD-box covers the relevant 10-year period starting with "Body and Soul" in 1939. with 88 wonderful treasures in all. Four outstanding Commodore recordings with the Chocolate Dandies, with Benny Carter and Roy Eldridge, are remarkable. It also includes the roller coaster quartet pieces "The Man I Love," "Sweet Lorraine" and "Crazy Rhythm," and several swingers from the collection.

Coleman Hawkins and Benny Carter

In Paris

(1935-1946, reissue DRG 1985)

The Hawk made some classic recordings in the mid-1930s with French sidemen like Django Reinhardt and Stephane Grappelli and some also with alto player/arranger Benny Carter. "Honeysuckle Rose" and "Crazy Rhythm" became famous. The additional takes of Carter's orchestra are a nice bonus.

Coleman Hawkins

Body and Soul

(RCA/Bluebird 1939-1956, reissue 1996)

This CD not only includes the four historic 1939 recordings at Kelly's Stables, a 1940 octet date with associates from his Henderson days and completely different settings in 1947 with bebop sidemen Fats Navarro, J.J. Johnson, Hank Jones and Max Roach.

Coleman Hawkins and Chu Berry

Tenor Giants

(Commodore 1938 -1943, reissue GRP 2000)

Interesting to compare the master and his most devoted follower on this Feather/Gabler mix. Includes six fine pieces of Hawk and Eldridge with The Chocolate Dandies. Chu Berry's performance of "Body and Soul" may well have influenced Hawkins' famous recording the following year.

Coleman Hawkins

Rainbow Mist

(Delmark 1993)

Marvelous and very swinging collection with Dizzie Gillespie, Oscar Pettiford and Max Roach, with a beautiful new treatment of" "Body and Soul," here renamed into "Rainbow Mist," plus some fine sessions with fellow tenorists Ben Webster and Georgie Auld.

Hawkins and Eldridge

Bean and Little Jazz

(Jazz Hour 1996)

Coleman Hawkins and renowed trumpet player Roy Eldridge ("Little Jazz") enjoyed working together, like they do here while touring with Norman Granz' Jazz at the Philharmonic in the 50's and at festivals like the famous one in Newport '59. Great listening.

Benny Carter

Further Definitions

(Impulse 1961, reissue GRP 1979)

Beautiful four-sax arrangements of Benny Carter for Hawkins and Charlie Rouse on tenor and Carter and Phil Woods on alto, including remakes of the classics "Honeysuckle Rose" and "Crazy Rhythm" from their 1937 Paris sessions. Hawkins is his own exuberant self and plays a strong and moving version of "Body and Soul."

Coleman Hawkins

Desafinado

(Impulse 1963, reissue GRP 1997)

During the bossa nova craze Hawkins, forever defiant and then some, tackled the usual samba material as well as corny tunes like "I'm Looking Over a Four Leaf Clover" and succeeded in turning them into real swingers.

Ellington and Hawkins

Duke Ellington meets Coleman Hawkins

(Impulse 1962, reissue 1995)

When two masters like this meet at long last then it is bound to be magical. They're all great Ellington compositions, but listen especially to a majestic "Mood Indigo" and "Self Portrait (of the Bean)." There is also a lot of synergy between Hawkins and Johnny Hodges.

https://www.robertchristgau.com/get_artist.php?name=Coleman+Hawkins

Coleman Hawkins

Ken Burns Jazz

[Verve, 2000]

A Consumer Guide Reviews:

Ken Burns Jazz [Verve, 2000]

Hawkins's sensual largesse and easy legato delivered the saxophone from vaudeville novelty. He was so deft with chords that he progressed unimpeded from swing to bebop and beyond, and along the way he launched the first solo saxophone track, which took off from the most famous solo in jazz history, his original improvisation on "Body and Soul." For all these reasons, this five-decade selection declines stylistic consistency. No problem. The big, breathy, paradigmatically Southwestern sound of his tenor doesn't dominate its harmonic trappings, or cut through them. It pervades them, from preswinging Fletcher Henderson to protégé-turned-auteur Thelonious Monk. And to finish off there's an unforced, unnostalgic Ellington-Hodges-Carney session that returns Hawkins to his youth in a graceful parabola. A

Related Content:

The first icon of the genre's most iconic instrument gets his due in a new collection.

There are few greater enticements for a jazz fan than a spirited debate

over who, exactly, is the most important tenor player in the medium's

history. Trumpeters, drummers, singers, and pianists, naturally, are

rated and re-rated any time two or more fans—or one critic—gets

together, but there is something both ancient and progressive about the

tenor sax that makes it jazz's most emblematic instrument. If the genre

ever had need to market itself like a sports league with a snappy

avatar, it would surely feature a heavyset black man, in shadow, legs

bent, back arched ever so slightly, eyes closed, as he soloed on into

the night.

John Coltrane tends to dominate these discussions. It is better to be a titan of Modernism with a penchant for disregarding tonalities than it is to be old-timey and what younger ears might regard as fusty. Coleman Hawkins, a.k.a. The Hawk, alas, has been seen as fusty for far too long. Swing music—and Hawkins did swing, in ways no one had before—often gets that tag, conjuring images of jiving hepcats: white professors in tweed, snapping their fingers slightly out of time while uttering "Go, daddy, go." If your great grandmother ever wanted to cut a rug, politely, there was swing music to abet her.

But thankfully for Hawkins's legacy, there's Mosaic's recently released, eight-disc Classic Coleman Hawkins Sessions 1922-1947. Hawkins, you might say, has suffered some discographical blues. If you ever took a jazz class in college—or if you can name a dozen jazz cuts—you probably know Hawkins's "Body and Soul" from 1939. Like Coltrane's "Giant Steps," Louis Armstrong's "West End Blues," and Charlie Parker's "Ko-Ko," it's a jazzy Dead Sea Scroll—hugely influential. Beat? Melody? Who needs 'em. The Hawkins of "Body and Soul" was pure rhythm, tethered only to the limits of his own imagination—limits that, on some occasions, seemed not to exist at all.

More comps than I have ever been able

to keep track of sprung up around "Body and Soul." You'd almost think

Hawkins was a one-hit-wonder, with a few lesser gems—like the

unaccompanied "Picasso"—venerated more by fellow musicians than they

were enjoyed by garden-variety listeners. Hawkins took fresh flight in

the 1950s, playing on a spate of blowing sessions, the recordings of

which have long been easy to come by. You get the Hawk on those

recordings, sure enough, but he's less plucky of a bird than he was

before—grandfatherly, almost.

But a lot of the music on this set

hasn't been so easy to come by. You could have gone scouring and found

the bulk of it, though your friends surely would have questioned the

outlay of effort and money in your Hawk-based odyssey. What we're

treated to is twofold: a seat around the birthing table for

tenor-saxophone art's first moments in this world, and a strain of

modernism that could hold its own in a cutting session with James Joyce,

Picasso, and Stravinsky.

What the Hawk gets up to on sides like "Wherever There's a Will, Baby," from November 1929, and "I Can't Believe That You're in Love with Me," from summer 1931, will do your head in. The former seems to be a mere punchy, upbeat tune with tight ensemble work. But when Hawkins commences his solo, it's like we've wandered into one of futurism's back corridors, with one effervescent, emboldened line building on and incorporating all the others that have come before, until it is hard to believe that this solo ever had a start or that it could have an end. Rather, what we're fronted with is a shimmering totality of sound. The solo in "I Can't Believe That You're in Love With Me"—a sloping, gentle ballad, on the face of it—is practically proto-punk, a series of sonic striations underscoring the singer's heartache, and probably making him better aware of its true depth.

Jazzers love to talk about tone. Without an enviable one, there's only so far you can go, and the tone on display throughout this box is as deep-bottomed, rounded, and buttery—while still forceful—as tone gets. Calfskin, threaded with wires of steel. Coupled with Hawkins's technique, it's also a capable redeemer of would-be dross, like the lightweight composition, "I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate," which Hawkins tackled in March 1933, unleashing an assortment of prickly, dissonant remarks on the solo that wouldn't be out of place on Coltrane's landmark Ascension album from 1965.

But it's a cut like "Memories of You," from July 1944, that best encapsulates Hawkins's ability to simultaneously surprise, compel, and innovate. He's well into his solo before you even realize it, like he'd come from around the corner of another world, and started blowing his horn in yours. I don't know any moment on any other record like it. Nor do I know what the hell I would have done if I was a tenor player who had to come along and try and follow all of this. But that's what Coltrane and Sonny Rollins are for, and hardly anyone else. http://www.npr.org/artists/15394698/coleman-hawkins

http://www.jerryjazzmusician.com/2004/03/great-encounters-3-the-lester-young-and-coleman-hawkins-kansas-city-battle/

Features

Great Encounters #3: The Lester Young and Coleman Hawkins Kansas City battle

March 29, 2004

Great Encounters

Book excerpts that chronicle famous encounters among twentieth-century cultural icons

The Lester Young/Coleman Hawkins Kansas City battle…

Coleman Hawkins

photo Lee Tanner

Excerpted from Lester Leaps In:

The Life and Times of Lester “Pres” Young

by Douglas Henry Daniels

Beacon Press, 2003

Text published with the permission of Beacon Press.

(Lester) Young earned recognition for being not only a stylist but a saxophone “freak” – not a pejorative term at all but rather a comment on his unparalleled virtuosity. He “could make a note anywhere” on his instrument. Certain notes were usually produced by depressing specific keys or combinations of keys on the saxophone (or valves on the trumpet and cornet), but “freaks” found ways to defy convention and orthodoxy by means of “false fingerings” and adjustments of the mouth and lips, or embouchure. The trombonist-guitarist Eddie Durham explained that “Coleman Hawkins and Chu Berry and those guys, they fingered it correctly with what they were doing. Lester and those guys (e.g. Herschel Evans) didn’t.” Furthermore, Young and Evans “could do anything they wanted to do with a horn, anywhere.”

It is against this background, then, that we should reinterpret accounts of the most famous saxophone cutting contest in the history of jazz. Legend has it that Young proved his worth in competition with Coleman Hawkins, bandleader Fletcher Henderson’s biggest star, at the Cherry Blossom at 1822 Vine Street in Kansas City, Missouri. Mary Lou Williams, the pianist and arranger with Andy Kirk’s band, was one of the first to tell the story of the local tenor men – Dick Wilson, Herschel Evans, Herman Walder, Ben Webster, and Young – triumphing over Coleman Hawkins, who lingered so long trying to get the best of the Kansas City stalwarts that he blew the engine on his new Cadillac while racing to the next Henderson date in St. Louis. In Williams’s words, “Hawkins was king until he met those crazy Kansas City tenor men.” Gene Ramey, from Austin, Texas, maintained that Young “tore Hawkins so bad…Seemed like the longer Pres played, the longer they had that head-cuttin’ session…the better Pres go.” The drummer Jo Jones and other musicians also related the tale, but few claimed actually to have been there to witness the dethronement.

It is difficult to verify the date of the battle or, as we shall see, whether it even occurred the way Williams and Jones recalled it, because though it was often recited as fact, it was witnessed by only a few people who left records of their recollections. In 1934, only about four months after the alleged cutting contest, the Chicago Defender not only praised Young as “one of the most celebrated tenor sax players in the music world” but also noted that he was “rated by many to be the equal of the old master (Coleman Hawkins).” The article made no mention of the Kansas City battle.

Perhaps the much-discussed event occurred after a “Night Club Party” advertised in the Kansas City Call in December 1933, shortly before Prohibition officially ended. As a matter of course, newspapers would not have documented a jam session, but Hendersonia, the definitive survey of the band’s activities, did list a December 1933 date in Kansas City. Then, too, the St. Louis portion of the story is corroborated by ads in the St. Louis Argus announcing that Fletcher Henderson and His Roseland Orchestra would play a December 1933 date at the People’s Finance Ballroom.

Noteworthy among the problems of verifying the battle royal is the fact that no less a personage than Count Basie himself challenged the actual story, maintaining, “I really don’t remember that anybody thought it was such a big deal at the time.” Basie admitted to having been in the Cherry Blossom and having witnessed the jam session among the city’s tenor players, but he insisted, “I don’t remember it the way a lot of people seem to and in all honesty I must also say that some of the stories I have heard over the years about what happened that night and afterwards just don’t ring any bells for me.” He recalled that after repeatedly being asked to play, Hawkins “decided to get his horn” and went across the street to his hotel to get it. When he returned, several people commented on his unusual behavior, because as John Kirby stated, “I ain’t never seen that happen before” – that is, “Nobody had ever seen Hawk bring his horn somewhere to get in a jam session.”

In his autobiography, Basie related how Hawkins went on the bandstand “and he started calling for all of those hard keys, like E-flat and B-natural. That took care of quite a few local characters right away.” Basie did not recall Mary Lou Williams’s presence, but he conceded that he left early and she might have come later. (She did.) But the very fact that he went home to go to sleep, he emphasized, suggested that no real battle was taking place: “I don’t know anything about anybody challenging Hawkins in the Cherry Blossom that night,” he reiterated.

Basie acknowledged how subjective such undertakings could be when he mused, “Maybe that is what some of those guys up there had on their minds,” adding, “but the way I remember it, Hawk just went on up there and played around with them for a while, and then when he got warmed up, he started calling for them bad keys.” He concluded, “That’s the main thing I remember.” Williams’s version of the story is neater and more dramatic than Basie’s, and perhaps closer to what Kansas Citians wanted to believe. But as Basie pointed out, sometimes it was a matter of opinion as to who won a cutting contest.

There is another problem with the accepted version of the tale: Young also told it differently, without making any mention of a cutting contest. He explained that he and Herschel Evans and others were standing outside a Kansas City club one night, listening to the Henderson band: “I hadn’t any loot, so I stayed outside listening. Herschel was out there, too.” Coleman Hawkins had not shown up for the date, so Henderson approached the crowd of hangers-on and, according to Young’s account, challenged them, asking (in Young’s words, which were not necessarily Henderson’s own), “Don’t you have no tenor players here in Kansas City? Can’t none of you motherfuckers play?”

Since Evans could not read music, Young accepted the challenge at the urging of his friends. Young recalled how he had always heard “how great (Hawkins was)…grabbed his saxophone, and played the motherfucker, and read the music, and read his clarinet part and everything” Then he hurried off to play his own gig at the Paseo Club, where a mere thirteen people made up the audience. Young nonetheless savored the memory of his triumph, observing, “I don’t think he (Hawkins) showed at all.”

By Young’s account, his success that night was highly symbolic, given that Hawkins was not even present. After all, with no rehearsal, he sat in the great saxophonist’s chair and played his part, reading the music on sight “and everything.” The basic point of the Williams and Young versions is the same: the new stylist with a local following defeated or matched the champion tenor player from the premier New York City jazz orchestra. Williams’s retelling of Young’s triumph sought to legitimize a new tenor stylist; the detail about Hawkins’ ruining his new car was very likely an embellishment designed to enhance the taste of victory by stripping the loser of a prized possession.

Mary Lou Williams’s account served to validate not only Young himself but also what would become known as the Kansas City style or school. It made the tenor saxophonist’s subsequent attainment of the Hawkins chair in Henderson’s band more meaningful, since this particular jam session was said to have convinced the orchestra leader that he needed to hire Kansas City men such as Young. However, the reputation that Young had earned with King Oliver and his sidemen may have played just as great a role in Henderson’s recruitment of him as the famous story of Young’s defeating Hawkins. King Oliver, Snake Whyte, trumpet player Herman “Red” Elkins, and others spread word of Young’s impressive abilities among fellow musicians. Some time later, for example, Elkins ran into Red Allen and asked him, after he had heard Young play, “What did you think of Lester?” “Oh, he was all right, but he wasn’t no Hawk,” Allen said. Elkins responded to the lukewarm statement by exclaiming, “I know he’s no Hawk. Prez will set Hawk down in a jam session and blow him clear out the room!”

Another interesting aspect of the story is the fact that because Young refused to play like Hawkins, Henderson’s reedmen snubbed him. The tale of the victory of the Kansas City style goes some way toward explaining the poor treatment Young would receive from Henderson’s men after he joined the band a few months later: they were generally uncooperative and probably jealous of the upstart. Because of his unique, un-Hawkins-like tone, Young was ostracized and resented by the New York musicians during the few months he was with the band, from spring to summer 1934.

___________________________________________

In order to talk about bebop, we need some historical perspective. So we’ll start a few years before the beginnings of the bebop era, in 1939.

At this time, swing music was still the predominant form of jazz. Big bands criss-crossed the country playing in dance halls and mostly played the same style of music that had been popular since the 1920s. Improvisation was kept to a minimum in favor of rhythms and melodies that catered to the dancing crowd. When players did improvise, it was usually in short burst using fairly simple methods rooted in the blues.

Now, I want to state that there is nothing wrong with this. I love swing music and there’s much to learn from studying and playing it. However, as is always the case, some younger musicians decided that this type of music wasn’t really speaking to their reality. And so they started to tinker, finding other ways to play the same swing songs they’d been hearing for years.

Tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins is credited with making a recoding in 1939 that changed everything. At the end of a fairly-traditional recording session, he decided to play “Body and Soul,” a true standard of swing music and the most recorded jazz standard of all time.

A couple of things set this recording apart: First, he barely plays the melody, only eluding to it for a few seconds at the beginning before taking off on his improvisation. Second, he plays very complex harmonic stuff, using the “upper structures” of the chords, something that’s too complicated to get into here, but was completely new at the time. Third, he does what is called “double-timing,” where he plays twice as fast as the original tempo of the tune.

These things were unheard of at this time, and many critics and fellow musicians screamed that he was playing nonsense, killing the tune, playing “wrong” notes, etc. But there was a crop of younger musicians, including Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Kenny Clarke and others who heard this and were inspired to push the music to new places, and that’s how bebop was born.

I’ll give you two versions of the song to check out. First is a very standard version from 1930 from Paul Whiteman. This hit #1 on the charts that year:

Beautiful, but pretty tame, right? Now here’s Hawkins just nine years later. See if you can hear the melody at the beginning and then tell when he veers off from it:

This still may seem tame to you, but in 1939 it was quite revolutionary. Some liken it to the first appearance of rap music and how that shook up the whole musical landscape. That’s what a profound effect this single recording had on jazz. This is one of those solos that just about every jazz musician, especially saxophonists, can play note-for-note.

Tomorrow we’ll jump into the bebop era in ernest with some Charlie Parker.

—

Jason Parker is a Seattle-based jazz trumpet player, educator and writer. His band, The Jason Parker Quartet, was hailed by Earshot Jazz as “the next generation of Seattle jazz.” Find out more about Jason and his music at jasonparkermusic.com.

You almost could say that modern jazz began at that record date. Of course, this does not mean that Coleman Hawkins walked into the studio and a few hours later walked out after singlehandedly changing the course of jazz. That would be an insult to an entire generation of jazz musicians whose contributions - some great, others small, none insignificant -- helped deliver jazz into the modern era. Through their labors even the most mundane pop tunes were transformed into jazz, and the best ones were adopted permanently into the repertoire as "standards" - staples like "I Got Rhythm," "Stardust," "How High the Moon," and of course, "Body and Soul."

What did happen was that on October 11, 1939, an accomplished musical artist named Coleman Hawkins arrived at one of the gates of jazz history, at a time when old aesthetic problems were being solved and new ones were being tackled, as jazz improvisors were striving to reach a higher level of musical expression. His interpretation of "Body and Soul" helped create a path to the future, setting new standards and creating new rules, transcending the work of the previous generation, and pushing the music toward a new level and into a new era.

And so, on that day, the "jazz ballad" achieved its fullest flowering yet in Coleman Hawkins' immortal recording of "Body and Soul." For that reason it still stands, these many decades later, as one of jazz's greatest milestones.

© Bob Bernotas, 2010. All rights reserved. This article may not be reprinted without the author's permission.

Coleman Randolph Hawkins (November 21, 1904 – May 19, 1969), nicknamed Hawk and sometimes "Bean", was an American jazz tenor saxophonist.[1] One of the first prominent jazz musicians on his instrument, as Joachim E. Berendt explained: "there were some tenor players before him, but the instrument was not an acknowledged jazz horn".[2] While Hawkins is strongly associated with the swing music and big band era, he had a role in the development of bebop in the 1940s.[1]

Fellow saxophonist Lester Young, known as "Pres", commented in a 1959 interview with The Jazz Review: "As far as I'm concerned, I think Coleman Hawkins was the President first, right? As far as myself, I think I'm the second one."[2] Miles Davis once said: "When I heard Hawk, I learned to play ballads."[2]

He attended high school in Chicago, then in Topeka, Kansas at Topeka High School. He later stated that he studied harmony and composition for two years at Washburn College in Topeka while still attending high school. In his youth he played piano and cello, and started playing saxophone at the age of nine; by the age of fourteen he was playing around eastern Kansas.

In late 1934, Hawkins accepted an invitation to play with Jack Hylton's orchestra in London, and toured Europe as a soloist until 1939, performing and recording with Django Reinhardt and Benny Carter in Paris in 1937.[5] Following his return to the United States, on October 11, 1939, he recorded a two-chorus performance of the pop standard "Body and Soul", which he had been performing at Bert Kelly's New York venue, Kelly's Stables. In a landmark recording of the swing era, captured as an afterthought at the session, Hawkins ignores almost all of the melody, with only the first four bars stated in a recognizable fashion. In its exploration of harmonic structure[5] it is considered by many to be the next evolutionary step in jazz recording after Louis Armstrong's "West End Blues" in 1928.[citation needed]

Hawkins' time touring Europe between 1934 and 1939 allowed many other tenor saxophonists to establish themselves back in the U.S., including Lester Young, Ben Webster, and Chu Berry.[6]

After an unsuccessful attempt to establish a big band, he led a combo at Kelly's Stables on Manhattan's 52nd Street with Thelonious Monk, Oscar Pettiford, Miles Davis, and Max Roach as sidemen. Hawkins always had a keen ear for new talent and styles, and he was the leader on what is generally considered to have been the first ever bebop recording session in 1944 with Dizzy Gillespie, Pettiford and Roach.[7][8][9] Later he toured with Howard McGhee and recorded with J. J. Johnson and Fats Navarro. He also toured with Jazz at the Philharmonic.

After 1948 Hawkins divided his time between New York and Europe, making numerous freelance recordings. In 1948 Hawkins recorded "Picasso", an early piece for unaccompanied saxophone.

Hawkins directly influenced many bebop performers, and later in his career, recorded or performed with such adventurous musicians as Sonny Rollins, who considered him as his main influence, and John Coltrane. He appears on the Thelonious Monk with John Coltrane (Jazzland/Riverside) record. In 1960 he recorded on Roach's We Insist! suite.[1]

Meanwhile, Hawkins had begun to drink heavily and his recording output began to wane. However, he did record for the Impulse! label for a time, a period which includes an album with Duke Ellington. His last recording was in 1967.

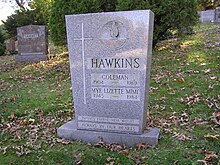

With failing health, Hawkins succumbed to liver disease in 1969 and is interred in the Yew Plot at the Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City.[1]

The Song of the Hawk, a 1990 biography written by British jazz historian John Chilton, chronicles Hawkins's career as one of the most significant jazz performers of the 20th century.

Yanow, Scott "Coleman Hawkins: Artist Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

Berendt, Joachim E (1976). The Jazz Book. Universal Edition.

Chilton, John (1993). The Song of the Hawk: The Life and Recordings of Coleman Hawkins. The University of Michigan Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-472-10212-5.

Gibbs, Craig Martin (2012) Black Recording Artists, 1877-1926: An Annotated Discography. McFarland, pp. 111-2. At Google Books. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

Lyttelton, Humphrey (1998). The Best of Jazz. Robson Books. pp. 256–287. ISBN 1-86105-187-5.

Chilton, John (1990). The Song of the Hawk:The Life and Recordings of Coleman Hawkins. University of Michigan: The University of Michigan Press.

Togashi, Nobuaki; Matsubayashi, Kohji; Hatta, Masayuki. "Max Roach Discography". jazzdisco.org. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

Brown, Don. "What Are Considered the First Bebop Recordings? – Jazz Bulletin Board". All About Jazz. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

Take Five: By Artist

Coleman Hawkins: Tenor Saxophone, Front And Center

Coleman Hawkins in 1946.

Before Hawkins arrived on the jazz scene with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra in the 1920s, the tenor sax was basically an ensemble instrument — as opposed to a improvisational instrument — mainly providing a link between the clarinets and brass instruments in military bands and big bands. Hawkins had different ideas, and through his virtuosic playing, he put the instrument front and center in the development of jazz. Hawkins' approach to music would later serve as a bridge from the era of big band swing to later developments like bebop.

Put simply, Hawkins was a musical pioneer, one of the most versatile and accomplished soloists in jazz history. Here are five samples of his genius.

Coleman Hawkins: Tenor Saxophone, Front And Center

Hello, Lola

- from Essential Sides Remastered 1929-1933

- by Coleman Hawkins

As Hawkins gained fame with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra, he began to get invitations to record with other musicians. Here's a 1929 session featuring Hawkins with the Mound City Blue Blowers, which was essentially a project of Red McKenzie, whose specialty was playing a comb covered in tissue paper. Perhaps to help legitimize his rather remarkable comb playing, he invited great jazz players to accompany him. On this recording, in addition to Hawkins, we hear Pee Wee Russell (clarinet), Gene Krupa (drums), Eddie Condon (banjo) and Glenn Miller (trombone). Before Hawkins, a tenor sax solo was a novelty; on this song we hear him taking his instrument out of vaudeville and into the future.

Body and Soul

- from Body and Soul [Bluebird]

- by Coleman Hawkins

Rifftide

- from Hollywood Stampede

- by Coleman Hawkins

Picasso

- from Jazz Scene [Verve]

- by Various Artists

Hawk Eyes

- from Hawk Eyes

- by Coleman Hawkins

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/coleman-hawkins-by-henk-de-boer.php

Coleman Hawkins

by

Although Adolphe Sax actually invented the saxophone, in the jazz world the title "Father of the Tenor Saxophone" became justly associated with Coleman Hawkins (1904-1969), not only an inventive jazz giant but also the founder of a whole dynasty of saxophone players. Before Hawkins, the saxophone (itself "born" in 1846) was mainly a favorite in marching bands and something of a novelty instrument in circus acts and vaudeville shows. Indeed, at age 16, Coleman started out with such a vaudeville group, Mamie Smith and her Jazz Hounds.

Even at 16 he garnered admiration for his ability to sight read and impressive musicianship. He started with the C-melody sax, which he soon traded for the more robust tenor, while also doubling on clarinet, baritone and even bass saxophone. Much more important was his 1923 engagement with the then famous Fletcher Henderson Band, of which also Louis Armstrong became a member (there is little doubt that Hawkins became influenced by his playing style). Here his talent ripened and ultimately grew too big for the somewhat stagnating opportunities the band offered him.

In 1933, Hawkins left Henderson to sail to England where he had a stint with the celebrated Jack Hylton Orchestra. For five years he toured the continent and more or less settled in Holland. Everywhere he played he was met with great enthusiasm, but for himself this was foremost a period of consolidation and further ripening. In 1939, he returned to the US and in that same year made an everlasting impression with his tender masterpiece "Body and Soul." "The Hawk" was fully back on the scene and maintained his grip until shortly before his untimely death in 1969.

Hawkins' personality and attitude were competitive and at times aggressive. He welcomed any opportunity to duel with other horn players, like his famous 1939 contest with his main opponent, Lester Young. Always aspiring to win, his playing was full of drive and rarely relaxed. Still, he made harmonious records with Benny Carter, Ben Webster and especially trumpeter Roy Eldridge. Due to his unique ability to adapt his playing style to new musical concepts, he made smooth transitions into bebop and cool jazz in the 40's, resulting in a comfortable collaboration with younger jazz pioneers.

Ken Burns Jazz

Coleman Hawkins

(Verve, 2000)

This compilation is a spin-off of the PBS production Ken Burns Jazz. It highlights nineteen significant recordings from "The Stampede" with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra in 1926 to his 1962 date with Ellington and as such represents an excellent overview for first timers.

Coleman Hawkins

A Retrospective 1929-1963

(RCA 1995)

Extensive 2 CD overview: 34 years of Hawkins' recordings for the Victor associated labels. This includes the early classics "One Hour" and "Hello Lola" with Red McKenzie on comb as well as the whole original 1939 session that originated "Body and Soul" up to the sixties.

Coleman Hawkins

The Body and Soul of the Saxophone

(ASV 2000)

A sound overview from 1929 to 1948 in 23 characteristic pieces on one CD, ranging from the early McKenzie recordings and "Body and Soul" to the renowned solo piece "Picasso."

Coleman Hawkins

The Bebop Years

(Proper 2001)