SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING, 2017

VOLUME FOUR NUMBER ONE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

DAVID MURRAY

(February 25--March 3)

OLIVER LAKE

(March 4–10)

GERALD WILSON

(March 11-17)

DON BYRON

(March 18-24)

KENNY GARRETT

(March 25-31)

COLEMAN HAWKINS

(April 1-7)

ELMORE JAMES

(April 8-14)

WES MONTGOMERY

(April 15-21)

FELA KUTI

(April 22-28)

OLIVER NELSON

(April 29-May 5)

SON HOUSE

(May 6-12)

JOHN LEE HOOKER

(May 13-19)

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/kenny-garrett-mn0000767404/biography

Kenny Garrett

(b. October 9, 1960)

Artist Biography by Richard Skelly

Saxophonist, bandleader, and composer Kenny Garrett is a most versatile player, equally at home playing classic blues and rhythm & blues as he is interpreting classic jazz compositions and even fusion. Although Garrett never had the benefit of a college education, that hasn't hurt his career as a jazz musician one bit. He has released a number of critically acclaimed albums and, prior to the birth of his recording career, paid his dues in the jazz clubs in and around his native Detroit.

Garrett's father was a carpenter who played tenor saxophone as an avocation. He got his first saxophone as an eight-year-old and quickly learned the G scale, thanks to his father. He studied with trumpeter Marcus Belgrave and began performing with Mercer Ellington's band before he had finished high school. His first few professional shows were with Detroit-area musicians Belgrave and pianist Geri Allen. He felt he had arrived as a saxophonist when he was asked to join the Duke Ellington Orchestra under the direction of Mercer Ellington. He skipped college and went on the road with the band for the summer and ended up staying with them for three-and-a-half years.

Garrett was raised in the Detroit jazz scene of the '70s, which wasn't nearly as vibrant as it had been a decade earlier. In high school, he had the good fortune to play with organist Lyman Woodard locally in Detroit, but recalls having to travel an hour or two from home to maintain his status as a working musician. He was encouraged to begin writing his own compositions by various members of Ellington's band, and began doing so a short time later. Aside from alto and soprano saxes, Garrett also uses the piano to compose. Prior to his rise under his own name as a bandleader and composer, Garrett had the opportunity to perform and record with Miles Davis, Art Blakey, Freddie Hubbard, Woody Shaw, and the aforementioned Ellington orchestra.

In 1982, he relocated to New York City, the jazz capital of the world. Garrett made his solo recording debut with Introducing Kenny Garrett on the Criss Cross label in 1984 and then jumped to Atlantic Records, a major label which, at that time, was interested in rebuilding its once glorious jazz legacy. He recorded two notable albums for Atlantic, Prisoner of Love and African Exchange Student.

He began recording for Warner Bros. in 1992, when he released his stunning, critically praised Black Hope. He followed up in 1995 with Triology, and recorded Pursuance: The Music of John Coltrane in 1996. He released Songbook, his first album made up entirely of his own compositions, in 1997. More albums for Warner Bros. followed including Simply Said, Happy People, and Standard of Language.

In 2006, Garrett moved to Nonesuch where he earned a Grammy-nomination for Beyond the Wall. Two years later, he delivered Sketches of MD (recorded at N.Y.C.'s Iridium club) on Detroit's Mack Avenue. Also during this period, he joined the all-star lineup of the Five Peace Band featuring keyboardist Chick Corea, guitarist John McLaughlin, bassist Christian McBride, and drummer Vinnie Colaiuta. The group's Five Peace Band: Live CD (Concord, 2009) won the Grammy for Best Jazz Instrumental Album in January 2010.

DAVID MURRAY

(February 25--March 3)

OLIVER LAKE

(March 4–10)

GERALD WILSON

(March 11-17)

DON BYRON

(March 18-24)

KENNY GARRETT

(March 25-31)

COLEMAN HAWKINS

(April 1-7)

ELMORE JAMES

(April 8-14)

WES MONTGOMERY

(April 15-21)

FELA KUTI

(April 22-28)

OLIVER NELSON

(April 29-May 5)

SON HOUSE

(May 6-12)

JOHN LEE HOOKER

(May 13-19)

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/kenny-garrett-mn0000767404/biography

Kenny Garrett

(b. October 9, 1960)

Artist Biography by Richard Skelly

Saxophonist, bandleader, and composer Kenny Garrett is a most versatile player, equally at home playing classic blues and rhythm & blues as he is interpreting classic jazz compositions and even fusion. Although Garrett never had the benefit of a college education, that hasn't hurt his career as a jazz musician one bit. He has released a number of critically acclaimed albums and, prior to the birth of his recording career, paid his dues in the jazz clubs in and around his native Detroit.

Garrett's father was a carpenter who played tenor saxophone as an avocation. He got his first saxophone as an eight-year-old and quickly learned the G scale, thanks to his father. He studied with trumpeter Marcus Belgrave and began performing with Mercer Ellington's band before he had finished high school. His first few professional shows were with Detroit-area musicians Belgrave and pianist Geri Allen. He felt he had arrived as a saxophonist when he was asked to join the Duke Ellington Orchestra under the direction of Mercer Ellington. He skipped college and went on the road with the band for the summer and ended up staying with them for three-and-a-half years.

Garrett was raised in the Detroit jazz scene of the '70s, which wasn't nearly as vibrant as it had been a decade earlier. In high school, he had the good fortune to play with organist Lyman Woodard locally in Detroit, but recalls having to travel an hour or two from home to maintain his status as a working musician. He was encouraged to begin writing his own compositions by various members of Ellington's band, and began doing so a short time later. Aside from alto and soprano saxes, Garrett also uses the piano to compose. Prior to his rise under his own name as a bandleader and composer, Garrett had the opportunity to perform and record with Miles Davis, Art Blakey, Freddie Hubbard, Woody Shaw, and the aforementioned Ellington orchestra.

In 1982, he relocated to New York City, the jazz capital of the world. Garrett made his solo recording debut with Introducing Kenny Garrett on the Criss Cross label in 1984 and then jumped to Atlantic Records, a major label which, at that time, was interested in rebuilding its once glorious jazz legacy. He recorded two notable albums for Atlantic, Prisoner of Love and African Exchange Student.

He began recording for Warner Bros. in 1992, when he released his stunning, critically praised Black Hope. He followed up in 1995 with Triology, and recorded Pursuance: The Music of John Coltrane in 1996. He released Songbook, his first album made up entirely of his own compositions, in 1997. More albums for Warner Bros. followed including Simply Said, Happy People, and Standard of Language.

In 2006, Garrett moved to Nonesuch where he earned a Grammy-nomination for Beyond the Wall. Two years later, he delivered Sketches of MD (recorded at N.Y.C.'s Iridium club) on Detroit's Mack Avenue. Also during this period, he joined the all-star lineup of the Five Peace Band featuring keyboardist Chick Corea, guitarist John McLaughlin, bassist Christian McBride, and drummer Vinnie Colaiuta. The group's Five Peace Band: Live CD (Concord, 2009) won the Grammy for Best Jazz Instrumental Album in January 2010.

In 2012, Garrett released his second album for Mack Avenue, Seeds from the Underground, featuring his own group with bassist Nat Reeves, Venezuelan pianist Benito Gonzalez, and Detroit drummer Ronald Bruner. Pushing the World Away followed a year later and featured primarily original compositions along with a cover of Burt Bacharach and Hal David's "I Say a Little Prayer." In 2016, Garrett delivered his fourth Mack Avenue recording, Do Your Dance!, which found him exploring all varieties of dance-oriented rhythms from hip-hop and to funk to Latin and beyond.

http://www.kennygarrett.com/

About

Kenny Garrett - Saxophonist

Over the course of a stellar career that has spanned more than 30 years, saxophonist Kenny Garrett has become the preeminent alto saxophonist of his generation. From his first gig with the Duke Ellington Orchestra (led by Mercer Ellington) through his time spent with musicians such as Freddie Hubbard, Woody Shaw, Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers and Miles Davis, Garrett has always brought a vigorous yet melodic, and truly distinctive, alto saxophone sound to each musical situation. As a bandleader for the last two decades, he has also continually grown as a composer. With his latest recording (and second for Mack Avenue Records), Seeds From The Underground, Garrett has given notice that these qualities have not only become more impressive, but have provided him with the platform to expand his horizons and communicate his musical vision clearly. Seeds From The Underground is a powerful return to the straight-ahead, acoustic and propulsive quartet format that showcases Garrett’s extraordinary abilities.

For Garrett, Seeds From The Underground is a special recording. It once again consists of all original compositions, and is truly an homage to those who have inspired and influenced him, both personally and musically. “All of these songs are dedicated to someone,” says Garrett. “And the ‘seeds’ have been planted, directly or indirectly, by people who have been instrumental in my development.”

With Seeds From The Underground Garrett has crafted a project that offers his appreciation while always making the listener aware of his band’s skillful approach to melody, harmony and rhythm. From personal nods such as the opening track “Boogety Boogety,” dedicated to his memory of watching western films with his father (the title refers to the sound of a galloping horse); “Wiggins,” which references his high school band director Bill Wiggins; and “Detroit,” an evocative, reflective composition about his hometown, and a celebration of mentor Marcus Belgrave; to his appreciation of some of his musical heroes on “J Mac” (Jackie McLean); “Haynes Here” (Roy Haynes); and “Do Wo Mo” (Duke Ellington, Woody Shaw and Thelonious Monk).

Melody, as a matter of fact, was a key element for the saxophonist when writing for the recording. “I wanted to focus on the melody,” Garrett reflects. “I want people to remember what the melody is before we start improvising…and on some songs I heard voices, the singing of the melody.” This latter point is in evidence on the selections “Haynes Here,” “Detroit” and “Welcome Earth Song.”

Another notable component compositionally for Garrett on Seeds From The Underground is his approach to rhythm and meter. Over the past few years, one of the most popular and acclaimed groups that he has been a part of is the GRAMMY® award winning Five Peace Band, joining guitarist John McLaughlin, pianist Chick Corea, bassist Christian McBride, and drummers Vinnie Colaiuta and Brian Blade. His participation in that band led him to experiment with writing in different meters. “Some of these songs are in odd meters; in my experience with John, we played some songs in odd meters, so I thought, this is a different way of writing songs,” Garrett states. “So there is some of that approach here.”

The Band

Garrett’s current working band is very much up to the task on Seeds From The Underground. And like all successful bandleaders, Garrett knows what he wants musically and has formed a band that will best communicate his message (with implicit trust among one another). Bassist Nat Reeves is a rhythmic anchor and a long-standing member of Garrett’s past aggregations. However, for this recording, Garrett thought a lot about the talents of fellow Detroiter, drummer Ronald Bruner, as well as Venezuelan pianist Benito Gonzalez. “When I decided I wanted to do the album, I had Ronald in mind; I thought that he would work well on these songs. And Benito has been in my band for a while, and we talked conceptually about how I hear the piano in the band. McCoy Tyner is my man, so I wanted to have more of that sound, and there aren’t a lot of young guys around who are dealing with that like Benito is.” Percussionist Rudy Bird also provides a driving, rhythmic pulse to the recording.

Contributions

A very important contributor to Seeds From The Underground is the project’s co-producer: pianist, composer and educator, Donald Brown. His friendship with Garrett goes back to their days with Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers. He has been an integral part of past Garrett recordings, and has been a musical inspiration for him. “I feel comfortable in the studio with him and I know he’s going to hear what I hear, because we think alike in how we hear music,” states Garrett. “I’ve also always admired his compositions and he was really inspired by these compositions, so he was glad that we were able to hook back up on this project.”

Garrett has always expressed interest in music from other parts of the world. Whether it’s Africa, Greece, Indonesia, China or Guadeloupe, he immerses himself in the culture and gleans from his experience something that becomes a part of his artistic message. On Seeds From The Underground, the African-influenced “Welcome Earth Song” and “Laviso, I Bon?” (the latter was inspired by a musician friend in Guadeloupe) are prime examples.

The album highlights Garrett’s overall  approach

to music: wide-ranging, receiving ideas from all musical sources and

genres. Garrett states, “I love the challenge of trying to stay

open…about music and about life. If it’s music, I just try to check it

out. Right now I’m listening to some music from Martinique and I’m

lovin’ it. If I like it, maybe I can incorporate some of it into what I

do.” As for composing: “I don’t try to control what I write,” he says.

“Music comes from ‘The Creator.’ It’s a gift that’s coming in, and I

receive it. I write in all genres, and I’m writing all the time. It’s

never about what it is…I just say thank you.”

approach

to music: wide-ranging, receiving ideas from all musical sources and

genres. Garrett states, “I love the challenge of trying to stay

open…about music and about life. If it’s music, I just try to check it

out. Right now I’m listening to some music from Martinique and I’m

lovin’ it. If I like it, maybe I can incorporate some of it into what I

do.” As for composing: “I don’t try to control what I write,” he says.

“Music comes from ‘The Creator.’ It’s a gift that’s coming in, and I

receive it. I write in all genres, and I’m writing all the time. It’s

never about what it is…I just say thank you.”

approach

to music: wide-ranging, receiving ideas from all musical sources and

genres. Garrett states, “I love the challenge of trying to stay

open…about music and about life. If it’s music, I just try to check it

out. Right now I’m listening to some music from Martinique and I’m

lovin’ it. If I like it, maybe I can incorporate some of it into what I

do.” As for composing: “I don’t try to control what I write,” he says.

“Music comes from ‘The Creator.’ It’s a gift that’s coming in, and I

receive it. I write in all genres, and I’m writing all the time. It’s

never about what it is…I just say thank you.”

approach

to music: wide-ranging, receiving ideas from all musical sources and

genres. Garrett states, “I love the challenge of trying to stay

open…about music and about life. If it’s music, I just try to check it

out. Right now I’m listening to some music from Martinique and I’m

lovin’ it. If I like it, maybe I can incorporate some of it into what I

do.” As for composing: “I don’t try to control what I write,” he says.

“Music comes from ‘The Creator.’ It’s a gift that’s coming in, and I

receive it. I write in all genres, and I’m writing all the time. It’s

never about what it is…I just say thank you.”Seeds From The Underground is the latest stop on what continues to be a fascinating musical journey for Kenny Garrett and his listeners. It’s a recording that is not only a significant personal statement from the saxophonist, but a musical declaration of his continued growth as a musician, and in particular, as a composer.

“Since my last recording, [his Mack Avenue debut, Sketches Of MD/Live At The Iridium], I’ve had a lot of different experiences [including the aforementioned Five Peace Band, as well as The Freedom Band featuring Corea, McBride and Haynes],” Garrett reflects. “What I liked about putting this album together was the idea that my writing had grown and had become a little different, partially the result of Seeds From The Underground.”

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/kennygarrett

Kenny Garrett

Kenny Garrett is a jazz saxophonist. He was born in Detroit, MI in 1960. His father was a tenor saxophonist. Kenny's career took off when he joined the Duke Ellington Orchestra in 1978, then led by Duke's son, Mercer Ellington. Three years later he played in the Mel Lewis Orchestra (playing the music of Thad Jones) and also the Dannie Richmond Quartet (focusing on Charles Mingus's music). In 1984, he recorded his first album as a bandleader, Introducing Kenny Garrett. From there, his career has included 11 albums as a leader and numerous Grammy nominations. During his career, Kenny has played with many jazz greats such as Miles Davis, Freddie Hubbard, Woody Shaw, McCoy Tyner, Pharoah Sanders, Brian Blade, Bobby Hutcherson, Ron Carter, Elvin Jones, and Mulgrew Miller. Garrett's music sometimes exhibits Asian influence, an aspect which is especially prevalent in his 2006 recording, Beyond the Wall.

http://www.jazzadvice.com/killer-triadic-pentatonic-concepts-made-easy-a-lesson-with-kenny-garrett/

June 24th, 2016

Killer Triadic & Pentatonic Concepts Made Easy: A Lesson With Kenny Garrett

Kenny Garrett is an incredible musician. He’s arguably had one of the largest impacts on alto saxophone since Charlie Parker…

All of a sudden, copying Charlie Parker didn’t seem that cool anymore.

But the thing is, Kenny Garrett built his unique style using the jazz language of his heroes. Besides his huge beautiful dark one-of-a-kind tone, that’s why it sounds so awesome.

Because he mixed his own unique style with the bebop language, it sounds like a natural and progressive evolution of the music.

Today we’ll have a listen and a look into what makes some his lines tick…

Getting into Kenny’s head

It’s always difficult trying to understand a modern player by listening to them play on their own esoteric compositions.What’s easier?

Studying their playing on a standard or a tune you’re ultra familiar with.

In this lesson, we’ll check out what Kenny plays on the Charlie Parker tune Ornithology, which is based on the tune How High the Moon.

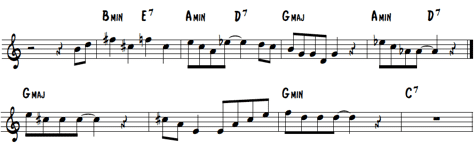

Here are the chord changes to Ornithology so you have an idea about what’s going on with the harmony if you’re not familiar with the tune.

Listen to Kenny Garrett play Ornithology and how effortlessly he weaves through the chord changes and commands the direction of the entire band.

Every phrase he plays has intent behind it and leads perfectly into the next one.

And, somehow he naturally takes his lines to some foreign sounding places that sound incredible.

But as you’ll see, they’re not so foreign. In fact, after this lesson you’ll be able to use the same strategies that Kenny Garrett is using to achieve some of these really cool sounds!

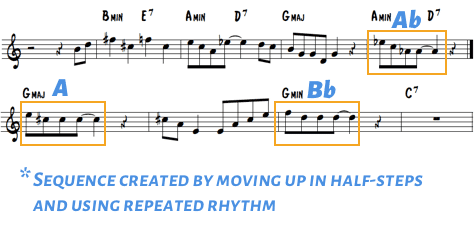

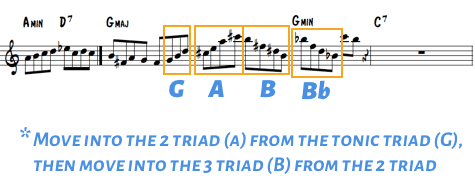

Using the 2 triad, the tritone triad, and creating strong sequences

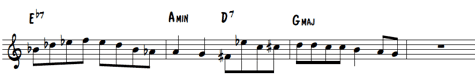

Listen to Kenny at 1:11 play the following line:

First at full speed…

Audio Player

00:00

00:00

And now at half speed…

Audio Player

00:00

00:00

In the 4th measure, he begins to take the listener on a journey. It’s completely unexpected, yet it doesn’t sound out of place.

How does he do it?

First off, let’s dissect what he’s doing here…

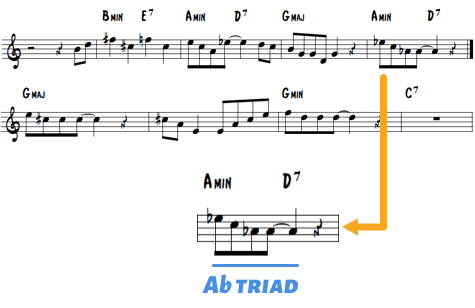

Over the ii V in the 4th measure, we’re headed back to the top of the form, and he uses an Ab triad over the entire measure.

This is the tritone sub (Ab) of D7 and it’s a great concept for you to use.

All you have to do is use the triad of the tritone sub. That’s it. That’s all he’s doing here and it sounds amazing!

But where does he take it?

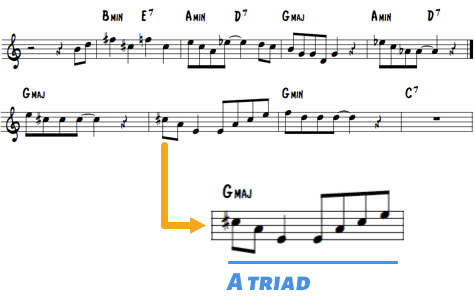

Rather than resolving to the G major at the top of the form, he moves up from the Ab triad to an A triad:

This is what I call the 2 triad because it’s the triad built on the second of the key, so in G major, the second is A, hence it’s an A major triad.

The 2 triad gives us all sorts of colorful notes: the 9th, #11th, and 13th.

That’s a pretty sweet deal just for thinking of a simple triad!

And he’s really thinking of the A triad in the measure before as well, just the top part of it, the 5th and 3rd without including the root.

Any time you want to spice up a major chord, the 2 triad is there to save the day.

But is that all?

Is there anything else holding this line together?

Well, I’m glad you asked. Yes, there certainly is.

One of the strongest things holding this line together is the use of a repeated rhythm.

Call it a sequence, motivic development, or whatever you want.

The point is that when you repeat a clear definitive rhythm while applying other melodic or harmonic devices, the repeated rhythm acts as the glue holding it all together.

So don’t just use these concepts…use them in a strong way.

Practice ideas

- Play over a blues and before every resolution, use the tritone triad as the basis for your melodic line

- Play over a blues and over each instance of the I and IV chords, use the 2 triad in a melodic way

- Play over a tune you’re working on and try to “setup” the 2 triad with the tritone triad

How to use pentatonics like a bad@$$

Pentatonic scales are one of the first scales improvisors learn and most people think of them as a fairly basic concept.Or, they might be something you started studying later on in your musical development and you have an array of intricate patterns and shapes you think you need to practice…

I can relate to both of these experiences. I first learned some pentatonic licks early on and soon realized they didn’t quite sound as good as I might have hoped.

And then later, I studied books that had endless pattern of pentatonics, but no matter how much I practiced them, they never really sounded musical or lyrical. They just sounded technical, like a machine.

Kenny Garret uses pentatonics perfectly and in a more simple way than you could ever imagine.

Have a listen to the line below and make sure to listen to it before looking at the line (1:24 in the recording).

First listen to it at full speed…

Audio Player

00:00

00:00

And now at half speed…

Audio Player

00:00

00:00

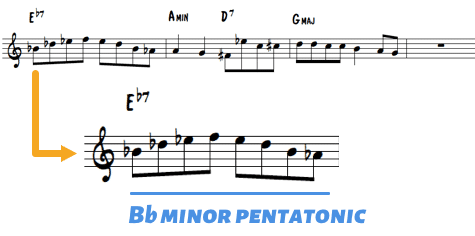

I’ve listened to this solo for years and I can honestly say that before I transcribed this line, I thought it was something much more complex.

It sounded so awesome and authoritative, I thought it had to at least be some sort of substitution…

But no…

All he’s doing is thinking of the minor pentatonic and playing a clear phrase moving up and down it:

So what’s the takeaway?

Don’t overthink it.

Use the minor pentatonic built from the V7 chord’s ii chord pair (In other words, if you saw the dominant chord in a ii V, what would the ii chord be? Bb minor for Eb7)

And sometimes, using pentatonics in a simple way is super effective.

Practice ideas

- Play through a tune you’re working on and over each dominant chord play the minor pentatonic of the ii chord pair

- Experiment with simple pentatonic shapes and aim to find a shape that is melodically strong and sounds good to your ear.

Using the 3 triad and triad pairs in a lyrical way

If you’ve been improvising for a while, then you’ve certainly heard about triad pairs. They’re constantly talked about as if they’ll solve all your musical woes and that they’re the key to creating beautiful lines.Sorry to be the one to tell you, but it’s not that easy.

No single device is going to be the end-all-be-all and if there were such a device, it most certainly wouldn’t be triad pairs.

Nevertheless, as we’ll hear in a moment, they can be used beautifully.

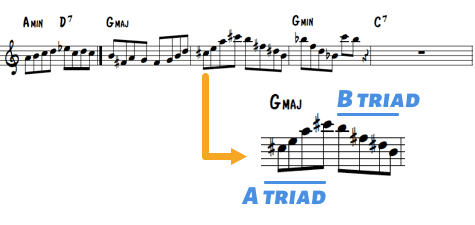

Listen to Kenny Garrett play the line below (1:34 in the recording)

First at the full tempo…

Audio Player

00:00

00:00

And now at half speed…

Audio Player

00:00

00:00

At this point, Kenny takes his triad concept to the next-level. Now he’s not only using the 2 triad, but he’s mixing in the 3 triad to form a “triad pair”:

Using the 3 triad (B in G major) is not easy because it uses the #5.

It can sound totally out of place if you can’t hear the sound in your mind.

To use both the 2 triad and 3 triad like Kenny Garrett is doing you have to train your ears to hear the sound. It’s that simple. It’s no coincidence we go over these in great detail within The Ear Training Method. If you can’t hear it, you can’t play it.

Or, you can, but it’ won’t sound right…

But besides actually hearing the sounds of the chord-tones as they relate to the tonic, in this case G major, you have to learn how to use the triads in a way that smoothly flow from one to the next.

Kenny Garrett teaches us how to do this if we look closely…

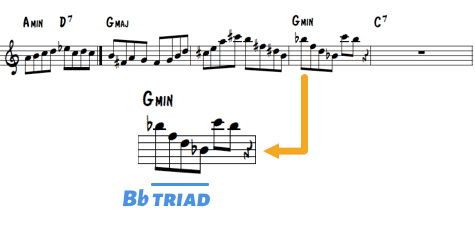

But before we get there, note that over the G minor chord, Kenny is using a Bb triad.

So we have even one more triadic tool to add to the list: the 3 triad on a minor chord – Bb major triad on G minor.

Back to how Kenny flows from one triad to the next…

He doesn’t just come right out and play the triad pair, he sets it up. Each triad smoothly leads into the next.

First, the tonic triad, G. It moves effortlessly into the 2 triad from the 5th of the tonic triad, down by half-step to the 3rd of the 2 triad.

Then he moves by whole-step down from the 3rd of the 2 triad to the root of the 3 triad.

And finally, he repeats the shape he plays using the 3 triad (1531 of B) with the 3 triad over minor (1531 of Bb).

There’s certainly a lot going on here! But we can take advantage of some of the underlying concepts he’s using. Here are a few things to focus on:

Practice ideas:

Pick a tune you’re working on and…

- Setup the 2 triad over a major chord (more dissonant) by starting your line with the tonic triad (less dissonant)

- Setup the 3 triad over a major chord (more dissonant) with the 2 triad (less dissonant). Notice the pattern

- Play the 3 triad over every minor chord

- Practice weaving between triads as Kenny does in the previous example

Acquiring killer triadic concepts, pentatonics, and bebop language

Clearly Kenny Garrett has done his homework. If you listen closely to all the examples presented and the entire solo, you’ll notice that he’s basically doing one of three things most of the time:- Using triadic concepts in an extremely effective way

- Using pentatonics in an extremely effective way

- Using standard bebop language heavily shaped and influenced by his particular style of articulation and unique tone

THE DIRTY DOG JAZZ CAFE BLOG

The Dirty Dog brings together the musicians and guests in a way that creates a lasting impression and desire to come back.

October 6, 2016

Award-winnng, world class saxophonist, Kenny Garrett, was born in Detroit on October 9, 1960. He shares his birthday with another great musician from Detroit, the world renowned multi-instrumentalist and composer, Yusef Lateef, (October9,1920 –December 23, 2013). Kenny Garrett is a 1978 graduate of Mackenzie High School. His father was a carpenter who also played tenor saxophone.

During his 30+year career, he has worked and recorded with some of the most significant style makers in Jazz. This includes having the opportunity work with the Duke Ellington Orchestra (led by Mercer Ellington) early in his career. He has also played with such Jazz luminiaries as Freddie Hubbard, John McLaughlin, Pharoah Sanders, Woody Shaw, Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers and spent more than five years as a member of Miles Davis’s band.

Kenny Garrett while with the Miles Davis band in the 1990’s. Photo: m.blog.daum.net

Garrett says, “I was in Miles’ band for about five years. I think that tag will always be there. That is five years of my life. That’s the only musical situation that I was there longer than a year. It was a good five years. I have gotten used to that.”

“Some people became aware of me through Miles and then they would come to my concerts. I think that is part of my history and I am proud of that. I am still trying to carve out my own name and my own music. I just look at it as a part of history and it is going to be there. Every time they mention Kenny Garrett, there will probably be some association with Miles Davis, but at the same time, when they mention Herbie Hancock, they always mention Miles Davis, or Wayne Shorter. You get used to it after a while.” (allaboutjazz.com)

Garrett has continued to bring his truly distinctive “voice” to each musical situation. He is also a gifted composer and writes and arranges most of the music on his recordings. Here’s our “Jazz Notes” review of his newest CD which has been at the top of the Jazz charts since its release in July 2016.

Kenny Garrett / Do Your Dance / Mack Avenue

Kenny Garrett compels listeners to listen to the music on his new album, which is his fourth on the Mack Avenue label. The music is so compelling, it pulls you right in. All compositions were written and arranged by Garrett. His band consists of artists who display the highest level of musicianship and improvisational ability creating a cohesive sound that brings energy and emotion to the music.

All compositions were written and arranged by Garrett. The high-energy opening track, “Philly”, sets the stage for the entire release. Piano virtuoso Vernell Brown Jr. is featured very prominently on this track as well as on the entire album.

Grammy award winner, Kenny Garrett is also a 9-time winner of Downbeat’s Reader’s poll for alto saxophone. He was a protégé of he late Marcus Belgrave who he refers to as his musical father.

“Do Your Dance” was inspired by the spontaneous art of dancing. The music here makes you want to jump up from you seat and express yourself with the dance of your choice. Kenny Garrett is encouraging us to put aside any shyness or physical embarrassment and just feel the natural joy of dancing which along with music is one of humankind’s first arts of self-expression.

His years with Miles Davis and the late Marcus Belgrave helped him lay down a strong foundation and focus on his own musical gifts. As a proud protege of Marcus, he often refers to as his “musical father”. His composition “Detroit” on his 2012 album, Seeds from the Underground is dedicated to Marcus Belgrave. It’s one of the most beautiful, and poignant musical tributes I have heard.

arranged by Garrett. The high-energy opening track, “Philly”, sets the stage for the entire release. Piano virtuoso Vernell Brown Jr. is featured very prominently on this track as well as on the entire album. Grammy award winner, Kenny Garrett is also a 9-time winner of Downbeat’s Reader’s poll for alto saxophone. He was a protégé of he late Marcus Belgrave who he refers to as his musical father.

“Do Your Dance” was inspired by the spontaneous art of dancing. The music here makes you want to jump up from you seat and express yourself with the dance of your choice. Kenny Garrett is encouraging us to put aside any shyness or physical embarrassment and just feel the natural joy of dancing which along with music is one of humankind’s first arts of self-expression.

His years with Miles Davis and the late Marcus Belgrave helped him lay down a strong foundation and focus on his own musical gifts. As a proud protege of Marcus, he often refers to as his “musical father”. His composition “Detroit” on his 2012 album, Seeds from the Underground is dedicated to Marcus Belgrave. It’s one of the most beautiful, and poignant musical tributes I have heard.

Detroit Public Radio mainstay, Judy Adams, is a trained pianist, composer and musicologist who hosts a Jazz and contemporary music show on CJAM 99.1FM and guest hosts on WRCJ 90.9FM.

https://jazztimes.com/features/kenny-garrett-seeds-of-history/

JazzTimes

Kenny Garrett: Seeds of History

The alto saxophonist explores his musical and personal past

Kenny Garrett hasn’t released an album as a leader since 2008,

but that doesn’t mean he hasn’t been busy. In recent years, Garrett lent

his revered alto sound to two very high-profile touring acts: Chick

Corea’s Freedom Band and the Five Peace Band led by Corea and guitarist

John McLaughlin. Corea chose Garrett as the only other common member of

the two groups, not only for his technical virtuosity but also because

of his emotional intensity. “Kenny has always been just pure inspiration

to me every time I hear him play,” Corea says. The two met more than 20

years ago, when Corea subbed for Garrett’s employer, Miles Davis, on a

keytar. “Kenny is a searcher-always looking for new approaches, always

finding new ways to extend an idea. He can take the whole band with him

to other realms.”

On his new collection of original acoustic music, Seeds From the Underground (Mack Avenue), Garrett is bolstered by his working band and does plenty of searching, much of it through his own personal and musical history. Better than his previous effort, the live, Miles-themed Sketches of MD, Garrett digs deep on this bracing tribute to the people and places that forged his identity as a player. For the saxophonist, 51, old and new can easily coexist. “I think what was happening yesterday is pretty much what’s happening today,” says Garrett. “I don’t think it’s like a past and present thing.”

Garrett opens the album with his characteristically melodic “Boogety Boogety,” dedicated to his father, a Detroit carpenter who first instilled in him the importance of developing an individual voice. Inspired by the Western films they watched together in his youth, the track finds Garrett dancing over drummer Ronald Bruner and percussionist Rudy Bird’s exuberant take on a galloping horse. (Pianist Benito Gonzalez, clearly indebted to McCoy Tyner, simply kills here.) “The first thing I remember about getting a sound is being with my father at the Dairy Queen, and he would ask me, ‘Who’s playing on the radio?’ And he said that everybody has a sound,” Garrett says. “I took my influences, like Johnny Hodges and Hank Crawford, and I just realized one day that I had my sound.”

Among his other influences, Garrett lists Grover Washington Jr., Cannonball Adderley and Larry Teal, the University of Michigan saxophone professor who taught Joe Henderson and Yusef Lateef. Teal played with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, and encouraged Garrett to develop a sound that captured “the warmth of the classical, but bigger,” he says.

In the early ’80s, Garrett further mined his idols in New York City, where he met bassist Nat Reeves, who has appeared on several of the saxophonist’s recordings, including Seeds. “You know who he is from the first note,” says Reeves. “You know who Coltrane is, you know who Jackie McLean is, Miles: Kenny is one of those musicians that has his own sound.”

Of course, Garrett’s hometown of Detroit has a lot to do with that singularity as well. “Detroit” is one of the new album’s high points, both a celebration of his mentor, Detroit trumpeter Marcus Belgrave, and an elegiac ballad reflecting on a city facing hard times. “Marcus is a pillar to the community. Geri Allen, Bob Hurst, James Carter-everyone coming through there at some point had some experience with Marcus,” Garrett says. Garrett played in Belgrave’s big and small bands, and through his mentor met Freddie Hubbard, with whom Garrett performed and recorded. The song also embodies the gospel pulse of the Motor City, in particular an old deejay Garrett listened to, Martha Jean McQueen.

On the polyrhythmic closer, “Laviso, I Bon?,” Garrett travels far from his hometown to Guadeloupe, a nation he first visited on tour with Miles. As heard on this rhythmically challenging cut, he has since returned to soak up the rhythms of gwoka. The notion of experimenting with odd meters was initially planted by John McLaughlin. “I used to hang with John in the back of the bus, and we would talk about Indian music, about ragas, life, languages, things like that. I learned a lot from him,” Garrett says.

On “Haynes Here,” Garrett pays homage to another collaborator he’s learned from, drum legend Roy Haynes. “When I played with him doing [2001’s] Birds of a Feather, it was never about me trying to play like Charlie Parker, because he’d already heard that,” Garrett says. “The history was there, but it’s about being in that moment, that time, and trying to keep it fresh.”

On his new collection of original acoustic music, Seeds From the Underground (Mack Avenue), Garrett is bolstered by his working band and does plenty of searching, much of it through his own personal and musical history. Better than his previous effort, the live, Miles-themed Sketches of MD, Garrett digs deep on this bracing tribute to the people and places that forged his identity as a player. For the saxophonist, 51, old and new can easily coexist. “I think what was happening yesterday is pretty much what’s happening today,” says Garrett. “I don’t think it’s like a past and present thing.”

Garrett opens the album with his characteristically melodic “Boogety Boogety,” dedicated to his father, a Detroit carpenter who first instilled in him the importance of developing an individual voice. Inspired by the Western films they watched together in his youth, the track finds Garrett dancing over drummer Ronald Bruner and percussionist Rudy Bird’s exuberant take on a galloping horse. (Pianist Benito Gonzalez, clearly indebted to McCoy Tyner, simply kills here.) “The first thing I remember about getting a sound is being with my father at the Dairy Queen, and he would ask me, ‘Who’s playing on the radio?’ And he said that everybody has a sound,” Garrett says. “I took my influences, like Johnny Hodges and Hank Crawford, and I just realized one day that I had my sound.”

Among his other influences, Garrett lists Grover Washington Jr., Cannonball Adderley and Larry Teal, the University of Michigan saxophone professor who taught Joe Henderson and Yusef Lateef. Teal played with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, and encouraged Garrett to develop a sound that captured “the warmth of the classical, but bigger,” he says.

In the early ’80s, Garrett further mined his idols in New York City, where he met bassist Nat Reeves, who has appeared on several of the saxophonist’s recordings, including Seeds. “You know who he is from the first note,” says Reeves. “You know who Coltrane is, you know who Jackie McLean is, Miles: Kenny is one of those musicians that has his own sound.”

Of course, Garrett’s hometown of Detroit has a lot to do with that singularity as well. “Detroit” is one of the new album’s high points, both a celebration of his mentor, Detroit trumpeter Marcus Belgrave, and an elegiac ballad reflecting on a city facing hard times. “Marcus is a pillar to the community. Geri Allen, Bob Hurst, James Carter-everyone coming through there at some point had some experience with Marcus,” Garrett says. Garrett played in Belgrave’s big and small bands, and through his mentor met Freddie Hubbard, with whom Garrett performed and recorded. The song also embodies the gospel pulse of the Motor City, in particular an old deejay Garrett listened to, Martha Jean McQueen.

On the polyrhythmic closer, “Laviso, I Bon?,” Garrett travels far from his hometown to Guadeloupe, a nation he first visited on tour with Miles. As heard on this rhythmically challenging cut, he has since returned to soak up the rhythms of gwoka. The notion of experimenting with odd meters was initially planted by John McLaughlin. “I used to hang with John in the back of the bus, and we would talk about Indian music, about ragas, life, languages, things like that. I learned a lot from him,” Garrett says.

On “Haynes Here,” Garrett pays homage to another collaborator he’s learned from, drum legend Roy Haynes. “When I played with him doing [2001’s] Birds of a Feather, it was never about me trying to play like Charlie Parker, because he’d already heard that,” Garrett says. “The history was there, but it’s about being in that moment, that time, and trying to keep it fresh.”

http://www.popmatters.com/feature/beyond-walls-an-interview-with-kenny-garrett/

Saxophonist Kenny Garrett rapidly ascended to great heights upon graduating from high school. Since then, he has performed and recorded with numerous jazz legends that most musicians can only dream of, including Miles Davis, Freddie Hubbard, Woody Shaw, McCoy Tyner, and Herbie Hancock. His idiosyncratic sound is a shifting fusion of many styles. Consider his work on the Beyond the Wall album, which was inspired by Chinese music and philosophy. He has released eleven albums as a bandleader and has garnered numerous Grammy nominations for his inspired work. With his new release Sketches of MD: Live at the Iridium featuring Pharoah Sanders, Garrett calls in Sanders to help him further expand his sound and finally captures and event he’d been working towards.

Garrett grew up listening to various types of music that his father would play in the house. His father’s influence has had an obvious affect on his vision as an artist and his love for different styles of music. Garrett shares, “My father played the tenor saxophone and I used to sit around and listen to him practice. I was drawn to the saxophone’s case; I was mesmerized by the smell. Eventually I started playing the saxophone.” He became inspired by some of the jazz greats of that time but says, “In the beginning it was my father that inspired me. Then I started to get into people like Hank Crawford, Grover Washington Jr., and Charlie Parker.”

It was a remarkable accomplishment for Garrett at the age of eighteen to perform with seasoned and consummate performers. “I think that my first big break was playing with the Duke Ellington Orchestra then directed by his son, Mercer Ellington. Right out of high school, I had a great opportunity to play with people like Cootie Williams.”

Garrett had wanted to record a show where he played with Pharoah Sanders. “[Sketches of MD] was really done so that my performance with Pharoah Sanders could be documented,” he explains. “We had done Beyond the Wall, which was nominated for a Grammy—I wanted to have us playing together documented since we missed that opportunity. I decided to write a few new songs and see what happened, that was really the premise.”

This time around, the timing was right. “The first time we played together was at the Blue Note in New York. Every time we played it was special, but we never documented it. It really wasn’t about anything other than that. I just really wanted to capture that moment.” Garrett could have easily recorded a second installment of Beyond the Wall, but, true to form, he wanted to go in another direction, to explore different musical avenues. As with Miles Davis, Garett’s music constantly changes and evolves.

Sketches of MD, as the title suggests, is a definite nod to Davis’s album Sketches of Spain. Featuring musicians Benito Gonzales, Nat Reeves, and Jamire Williams, Sketches of MD balances improvisation and the exploration of melody. It is relaxed, yet it still has the feel of a live album, complete with an enraptured audience. Like Davis, whom he is so often associated with, Garrett is a master of melody and musical exploration. As he says, “When you are improvising you don’t really set out to do any one thing, it just kind of happens.”

His use of effects on the saxophone certainly achieved the overall objective he was aiming for, and he says of the title track, “I’m playing a lot of ‘colors’ on this one. It’s not about improvisation as much as the melodies. At the end when we break it down and do the free-for-all thing where I re-harmonize the chords over the bass line that is my take on my experiences with Miles. It wasn’t planned. It just flowed that way.”

Playing with Miles Davis came about as though it was predestined. “I was auditioning for this French movie. A tenor player by the name of Gary Thomas came in and told me that Miles was looking for an alto player, and he asked if I was interested and of course, I was interested. Miles had basically said that he was looking for me because he had seen me perform at Birdland in Germany—I was playing with Woody Shaw, Dizzy Gillespie, and Freddie Hubbard. It was meant to happen. I guess he was looking for me and I was looking for him!”

Although he was influenced by the way that Miles Davis approached his music, Garrett’s time performing with Davis allowed him to find and explore his way musically while gaining invaluable insight. “I think the main thing is to be myself; to play music that I hear and feel, as opposed to what other people might think of it. By the time you figure out what you are doing you will be doing something else—which is true. I think as an artist you always have a lot of ideas and are looking for ways to express them.”

Garrett was formerly recording for Warner Bros. Records, and has now decided to release his newest project on Mack Avenue Records. He explains, “A lot of the bigger companies have an idea of what you should do and how it should be done. Mack Avenue is allowing me to do what I want to do and they are open to different ideas. They are an independent label with big ideas.” The ability to express his creativity is of utmost importance, and the move to another label was inevitable.

Amidst Garrett’s tour to promote his new album, he will also be involved in a tour with some of the most talented musicians in the business today. “I am definitely going to tour as much as I can to promote Sketches of MD. I am also going to be touring with Chick Corea, Jon McLaughlin, Christian McBride, and Vinnie Colaiuta, and then I will be doing another record.” That tour is certain to be a celebration of not only expertise, but of discovery; each of these musicians is a pioneer within the jazz community. They are not afraid of taking chances with their music, and Garrett will be right in his element with these artists.

Preview: Saxophonist Kenny Garrett brings experiences

December 11, 2014Photo by Keith Major. Kenny Garret

Saxophonist Kenny Garrett originally wasn't enamored with the saxophone itself -- as a child, he was merely entranced by the smell of the case.

But his father, also a sax player, eventually got his son a plastic horn for Christmas one year, and "taught me the G-scale and that was it."

Now a successful musician in his own right, Mr. Garrett comes to the New Hazlett Theater Saturday as part of the Kente Arts Alliance's "Alto Madness" series.

The Detroit native looks back to his growing years as more fertile musically than he was aware.

"When I was there I didn't realize the importance of the music I was around," he says, noting his exposure to jazz and the classic Motown sound. But, "Growing up in Detroit," he says, "I never tried to separate music."

As for his influences, "In the beginning there was Grover [Washington Jr.], Hank Crawford, Sonny Criss," but he later got into Charlie Parker and John Coltrane. "A lot of [my father's] heroes became my heroes," he says.

Deciding in high school to focus on music, Mr. Garrett was mentored by trumpeter Marcus Belgrave -- who appeared at last year's University of Pittsburgh Jazz Seminar -- and saxophonist Bill Wiggins, Mr. Garrett's high school band director and a composer and arranger in his own right. "He would do arrangements on the stop," Mr. Garrett says, and that inspired him to write for Mr. Belgrave's big band.

Upon leaving high school Mr. Garrett went with the Duke Ellington Orchestra, then led by Ellington's son, Mercer, and has since performed with such name musicians as Marcus Miller, Herbie Hancock, Elvin Jones and Ron Carter.

Because they share a first name and last initial, occasionally Mr. Garrett is mistaken for fellow saxman Kenny Gorelick, often trashed by critics and other musicians.

"They called me 'the real Kenny G,' " Mr. Garrett says. "Sometimes it gets a little confusing."

In the late 1980s he heard from a French musician that Miles Davis was looking for an alto player. He sent the trumpet legend a tape.

Apparently Mr. Davis was impressed because "he said that I was wearing Sonny Stitt's dirty drawers." Mr. Garrett remained with him until Mr. Davis' 1991 death -- "a great growing period." He says he learned from Mr. Davis "just to be myself, with my sound, writing my own music, trying to find my voice." After all, that's who Mr. Davis always hired as musicians anyway.

Mr. Garrett -- who will be backed by pianist Vernell Brown, bassist Corcoran Holt, former Yellowjackets drummer Marcus Baylor and percussionist Rudy Bird -- says he loves playing Pittsburgh and looks forward to playing here.

"We come on every once in a while. Not as often as we like, but we try to get there," he says. "People love the music -- we're fired up."

http://notesonjazz.blogspot.com/2015/05/an-interview-with-saxophonist-kenny.html

NOTES ON JAZZ

A forum for jazz reviews, discussion of new jazz & blues music, the musicians, reviews of recent and historical releases, reviews of live performances, concerts, interviews and almost anything I find of interest. by Ralph A. Miriello

Thursday, May 14, 2015

An Interview with the Saxophonist Kenny Garrett

April 16, 2015

Kenny Garrett photo by Ralph A. Miriello

The saxophonist Kenny Garrett has been a prominent voice on the alto saxophone for several years. At age fifty-four, Garrett, is in the sweet spot of his musical career. He has honed his skills the old fashioned way, he’s earned it with a career spanning close to four decades and associations with some of jazz’s most celebrated creators. Garrett started in the Duke Ellington Band with Cootie Williams, was a member of The Mel Lewis Orchestra, and played in Charles Mingus alum Dannie Richmond’s band. He was a member of the Art Blakey School of music and gigged with iconic all stars Woody Shaw, Freddie Hubbard and Joe Henderson. Perhaps his most dogged association is with Miles Davis. Garrett played for the legendary band leader for the last five years of Davis’ life.

Today Garrett is the consummate professional and certainly his own man. His most recent two albums, Seeds from the Underground and Pushing the World Away are proof in point. Both albums were nominated for Grammy awards under the category of “Best Instrumental Jazz Album”. Both feature Garrett compositions that pay homage to some of his influences. “J Mac” from Seeds from the Underground is dedicated to alto great Jackie McLean. The song was nominated for a Grammy in the “Best Instrumental Solo “ category. “Wiggins,” also from Seeds, is a bow to Garrett’s former high school band and private teacher Bill Wiggins. “Do Wo Mo” is a three way tribute to Duke Ellington, Woody Shaw and Thelonious Monk, all important influences. On his most recent album Pushing the World Away, Garrett continues in the same vein with compositions dedicated to longtime friend Chick Corea, “Hey Chick;” mentor the late Mulgrew Miller, “ A Side of Hijiki;” Sonny Rollins, “J’ouvert;” and his producer Donald Brown on “Brother Brown.”

Garrett, no stranger to recognition, has garnered no less than eight wins in the ”Best Alto Saxophonist”category of the annual Downbeat polls. Despite an innate desire to be creative with his music he is always aware of his audience. We talked to the saxophonist by telephone on April 16, 2015.

NOJ: I am a big fan of your music. Your last two albums were pretty moving and I think you sort of bridged the gap, for people who are not quite willing to go far mainstream as people like Robert Glasper, but yet still produce solid improvisational music that has a wider appeal. I am not sure if you have been trying to consciously do that, but I think it is working.

KG: Well no actually I just play the music as I hear it. Some of my heroes in the music that I have heard, people like McCoy, and Trane and Sonny Rollins and people like that, that is the music that I hear, so I try to write what I am hearing and that ( my music) is really a reflection of that.

NOJ: In interviews you have said that your musical path emerged by working with the elders and that now musicians are taking a more academic approach to learning jazz. Is this more academic approach affecting, what I would call the social connectivity that jazz used to have with its audience and is the music becoming too esoteric for its own good?

KG: See, I think every generation has to define the music. … I always like to tell the story, I was recording this CD and the tune was called “Ain't Nothing But the Blues” and when I wrote the song I was thinking about Miles Davis, BB King and Bone Thugs- N- Harmony, it’s a hip hop group. So Bobby Hutcherson was recording with me and he says to me, “ You’re kidding me, is that the blues?” I said to myself it’s the blues all day long, but with that being said, I guess because( he was from a different generation) he heard it totally different. To me it had trickled down a little bit differently he said “Wow is that the blues?” Sometime when I hear music I say “Is that jazz?” So every generation kind of has to come to terms or get a grip on to how the music is moving differently than you might want it to move and I am the same way.

(The music) Its moving, it’s a different way of learning it. I come through the university so I don’t really look at it that way. Actually the blessing is that I got to play with the greats. I played with people like Miles Davis, Freddie Hubbard, Woody Shaw, Cootie Williams, Donald Byrd, Art Blakey, and Dizzy Gillespie when you think of that, you kind of hold onto that as something dear. I think it is a little different approach to the music. That’s neither good nor bad, it is what it is. Others are trying to find it their way. The way I learned it, I learned from more of an almost an African tradition, it was passed down. It is not really passed on now as I did it. There are people, musicians who are teaching it ( in universities), they have actually been in the forefront, but it is just another approach.

NOJ: I want to get back to a point. To paraphrase a famous line attributed to Duke Ellington that there are only two kinds of music , good music and everything else. Do jazz musicians today get stuck on playing music for themselves and not making it entertaining enough for a broader audience?

KG: I think that depends on the generation. I think if you are in a laboratory and you come from a university and you are in a laboratory and that’s the way you’re assimilating it then that’s the way it might be. I think everybody is different. Our jazz has always been the same. People have always been saying, jazz musicians are playing for themselves. Some of that is true, I think even for myself, some of it is true I am playing for myself, but also I am cognizant that the audience is there. What I would like for the audience to experience is this journey that I would like to take them on. It is not that I don’t acknowledge them, I definitely acknowledge them, I am hoping that this music will touch them in some way, even if they have never heard me before, I am hoping it will touch them. …I hear a lot of young people come up to me and say I never heard music like this before. I say to them it’s a little different because these are my experiences that I am presenting to you. You can’t expect a younger musician who hasn’t had that many experiences to really come up with something like that at this point. You’re going to have to wait, and I m sure that is what some people say about me. Ha ha.

NOJ: I read several interviews where you said that Pharaoh Sanders, who is a well know contemporary of John Coltrane, said he sees a lot of John in your playing. Do feel that connection and do you consciously try to achieve that connection or is it something that comes out of you because of his influence?

KG: I think for me it simply comes out of me. I look at a lot of times, when Pharaoh and I play together it’s so uncanny. A lot of times, because he played alto before he played tenor, we’ll go and play the same notes. Sometimes I am in his register or he is in mine and one of us will have to go higher.

Of course, John Coltrane is one of my heroes, there is no denying that, but I think I can still kind of find a way to get to that feeling ( that John had) in my music. So I am always looking for that feeling, I guess (it’s) that spiritual quality, really just a feeling that brought me to the music. I remember when I was a kid, I used to basically take all my forty-fives, I would hide them, and then during Christmas time I would pull them out and I would play all of them. They would fill me up. It was a very emotional feeling that I got. When I listen to music I would love to hear that. So when I am playing music I am trying to get back to that emotional experience that I had when I was a kid.

NOJ: What kind of forty fives were you listening to?

KG: I would listen to anything, any of my favorite records, some R & B and some jazz. Coming from my home, my father was listening to jazz and my mother was listening to Motown so I had both. Any of my favorite records , it could have been Kool and the Gang, Maceo Parker , it could have been James Brown that feeling was what I was looking for every time. When I start thinking about music, I say to myself, I wonder if I can bring that feeling back, for people to experience what I was experiencing at the time.

NOJ: Which was joy, it was real joy, right?

KG: It’s really joy. That is what I am hoping for. Everybody gets something different from it. The core of what I am trying to get people to understand, I think it gets there. When you travel people always come up to me after a show and ask “What is it that I was experiencing? It’s something but we can’t really put our finger on it.” To me that’s good because at least it’s something that they feel. They don’t have to be able to explain it, as long as I know you can feel something from it, then I think mission is accomplished.

NOJ: Well you obviously are doing something right. You received Grammy nominations for your last two albums Seeds from the Underground and Pushing the World Away . These alums paid homage to some of the people who made an impression on your life and both had critical and general appeal. What’s next for you after having looked back from where you came?

KG: I think that a lot of people were saying I looked back, but if you check out my cds I’ll always look back. I always acknowledge. Seeds was acknowledging a lot of people. Most of the cds it might be just one person, maybe two people, maybe I might play some songs that remind me of someone. But I am always doing that , I always do that because I always feel blessed that I had the opportunity to play with Miles, Freddie and Woody . I mean these guys…if I had come up at a different time I think it would have been something different, but to acknowledge that and to acknowledge people. There was a tenor saxophonist from Detroit, his name was Bobby Barnes, and he gave me a couple of lessons and I tracked him down just to thank him. He said, I really did (something for you), and I said the lesson that you gave me was an important lesson, because I still use it today. Sometimes it’s not the person that you think it is it’s another person who gave you something new. So I am always grateful for that. I wouldn't be here if there wasn’t a little struggle, I was working hard, but definitely their input was very important, it’s always important.

NOJ: I love that song “Wiggins” from Seeds, that was such a hot number and I guess it was dedicated to one of your onetime school band leader?

KG: Bill Wiggins was my high school band director but I also took private lessons with Bill. Bill studied with Larry Teal, who is a classical saxophonist. Joe Henderson studied with Larry Teal, Vinnie Martin studied with Larry Teal. Brother Yusef ( Lateef) studied with Larry Teal. So the thing was I wanted to play with Larry Teal and Bill said you don’t have to study with Larry Teal I studied with Larry Teal. I wanted to go to Cass Tech which was the best school to be in, he said you don’t have to go to Cass Tech I went to Cass Tech and I will teach you. He was one of the cats along with Marcus Belgrave who really helped me. Wiggins was the one who actually sent me to Marcus to try to learn more.

NOJ: To go back to Coltrane for one second. What was the first recording of John Coltrane that you heard that really moved you?

KG: Actually it was a recording; I think it was called the Blowing Session with Johnny Griffin, Hank Mobley, Lee Morgan, Art Blakey, I’m not sure who was playing piano on there, but I remember playing on “All the Things You Are” and Johnny Griffin was killing, he was playing all this stuff, you know how Johnny plays, and Trane he was playing one note and ah man it’s all over. For me it was over he just played one note, you got to be kidding me.

NOJ: Yeah, economy can sometimes be a very powerful thing and lost on some people. You once related that Miles said to you “You sound like you are wearing Sonny Stitt’s dirty drawers.”

KG: (Laughing)

Sonny Stitt

NOJ: (Laughing) You know Kenny what you say on line can come back to haunt you.

KG: (Still Laughing) You know that’s the truth.

NOJ: Was that a fair comparison at the time and were you trying to emulate Stitt?

KG: Well no I don’t actually think I sounded anything like Stitt, but I think for him, I think that is what he heard. Of course I did listen to Sonny Stitt, but I don’t think… I was listening to Bird and Cannonball and Sonny Criss, but I think for Miles , you know he heard that.

NOJ: Stitt was famously lost in Charlie Parker’s sound which was hard for him to get away from. He was a great player but it was hard for him to be under that shadow.

KG: Well of course. I think a lot of musicians were able to discern Stitt rather than Bird, which is what I’ve heard. A lot of musicians were able to get that. But I think for me growing up in Detroit if you play alto you have know about Charlie Parker.

NOJ: As a musician who is now at the top of their game, it must be liberating to know you can proceed in any musical direction and be able to accomplish whatever you are trying to achieve. What musical challenges do you still want to conquer?

KG: So many things I would really like to attempt to do, it’s just really the timing, but what would I like to do? Something I would like to do is to record a cd with strings. Something I would like to do is record with some Japanese Kabuki musicians. I mean there are a lot of things, but it depends if I have a lot of time to really prepare for it. Everything is moving so quickly, If I had the time to really go in and research and do it like I kind of research I did with Beyond the Wall for example. So it depends on where I am at the time.

NOJ: You have played with the Five Peace Band and the live album actually won you a Grammy in 2010. With the exception of Christian ( McBride) and Vinnie ( Colauita,) you , John () and Chick () had all played with Miles. Did you guys feel like you took what Miles started and brought it to a new level?

Five Peace Band

KG: I m not sure what their goal was, but to me it was a learning experience. Playing with John, he has a lot of information. He has studied a lot of Raga, Indian music. Chick and I we have a relationship so that was great, but I can’t say what direction they were trying to go in. That would have to be something you would have to ask them. I took initially that we would all contribute to the music, but it ended up (being) more Chick and John doing most of the writing, which in the long run actually helped me. We had one song and it was fifteen ( time) and I really wasn’t playing a lot of odd meters at the time. It was a learning experience playing with John. Chick and I have been friends a long time, but musically I couldn't really say if they were trying to take it to the next level or not.

NOJ: You are primarily an alto player, but you are also a formidable soprano player. I read that you once played John Coltrane’s soprano. Did that experience lead you to embrace the instrument?

KG: No actually, when I played with Miles there were a lot of saxophone players asking me why I wasn’t playing soprano. I really just didn't hear it, at that time I was focusing on my alto playing and trying to find my voice, but then eventually … I don’t think with Miles I ever played any soprano, but then later I got a soprano and started to practice with it and that’s what happened. I’m surprised you heard about my playing Coltrane’s soprano.

NOJ: What do you like about the soprano’s voice as opposed to the alto?

Kenny Garrett on Soprano

KG: I think my treatment of ( the soprano) it’s a lighter sound. The alto is kind of like a tenor for me, so when I play the soprano it kind of lightens it up a little bit , I don't have to have the same voice. It kind of breaks it up a little bit.

NOJ: There have been many schools of alto playing over the years, the so called West Coast cool school of Lee Konitz, Art Pepper, Paul Desmond and then there is the East Coast school coming out of the Parker lineage, Sonny Stitt, Phil Woods, Jackie McLean and of course Dolphy, Cannonball and the Coltrane influence. Where do you think you fit in or is it relevant at all as to where you fit in?

KG: That’s a hard one,. I’m not sure, because there are so many different schools that I have been influenced by, so many of those people. When you’re studying music, you really don’t know where you’re coming from. (Laughing) They start to draw you in and you start to try to emulate them, but of course one of main influences is still Trane, but not only Trane there is Sonny Rollins, there is Joe Henderson, there is Maceo Parker so many people.

NOJ: But those are all tenor players right?

KG: Well yeah but so many , there is Bird , there is Hodges, there’s Sonny Criss there are so many people in the beginning. But in thinking about the voices that I really hear that influenced me the most it would probably be like Sonny and Trane and Joe and Wayne ( Shorter) those are the few guys that stick out. There was a point when I checked out Wayne, by playing with Miles it sent me back checking out those records to listen to Wayne’s voice and this view that he is coming from. But of course when you talk about Wayne he’s coming from Trane and Trane’ss coming from Bird so all those tongs lead back at some point.

NOJ: What do you think about the West Coast school and the cool sound?

KG: I don't really think about that. I have listened to Lee Konitz so I can’t really say… I don't really think about West Coast vs. East Coast, whoever I like I just take it all in.

NOJ: Are there any young players that you are particularly impressed with?

KG: Actually I like an alto player from Baltimore this guy’s name is Tim Green. I like his voice and I like what he is trying to do/ There are of course is many players Jaleel Shaw and Bruce Williams come to mind. Actually Antoine Roney, Wallace Roney’s brother, I like Antoine’s playing a lot. There are of course quite a few players that I haven’t yet heard.

NOJ: You've become more melodic in your more recent compositions. Is this conscious effort to try to connect with your audience and perhaps widen the music’s appeal?

KG: I have always been very melodic. I ve always loved melodies since day one so that is just really a natural thing for me.

NOJ: You played piano on your last two albums. I particularly point out “Brother Brown” from Pushing the World Away, where you are being uncharacteristically backed by strings (. I guess that is a window into what you want to do with strings in the future? ) ( Laughing) How does the piano expand your voice in ways that the saxophone does not?

KG: Playing the piano allows me to orchestrate a little bit more, harmonically to be able to play something for gigs. A lot of the ideas they come quicker on the piano, because it’s right there and of course I hear it because I play it all the time. I hear it on the saxophone, but it’s a little bit quicker, for me it’s a visual thing you can see it right there ( on the piano) and it just kind of happens. Sometimes if you play the notes on a saxophone, like a C Major and its fine, but the same notes might be something a little different when you play the piano. I play piano on a lot of my records, but I don’t always play a solo like on “Brother Brown”.

NOJ: I remember the last time I saw you perform at the Iridium and Mulgrew Miller was there before he passed and he sat in with you guys. It was so interesting to see Benito Gonzalez and some other piano players hover around him watching him carefully as he played. It was a great show and a great experience.

KG: There was so much respect from musicians because they realized that Mulgrew was trying to be the best he could be. I definitely remember that, with all the cats going wow. Mulgrew and I we have been friend for thirty five years so I knew what he was really striving to do. He was trying to accomplish and be one of the greats!

When we first came to New York we would go to see Tommy Flanagan, Barry Harris, Hank Jones and people like that, so I think for him that was what he aspired to be. I came up through the Duke Ellington Orchestra, but he also had a chance to play with Woody Shaw and Betty Carter and all these different experiences, big band and small groups. A group with Woody Shaw that harmonically was just crazy. So all these experiences led him to be the great player he was.

NOJ: You have favored pianists with a very percussive technique, distinctively a very McCoy Tyner influenced sound. Your pianist Benito Gonzalez is a good example of this style. McCoy’s style with Coltrane was once described to me by the pianist Steve Kuhn ( who briefly played with Trane just before Tyner) as laying down a carpet of sound that John could then explore from. Is this what you look for in a pianist, to give you this kind of platform to work off of?

KG: Well that’s definitely how I hear it. Of course by listening to those records of Coltrane playing with Mc Coy, at some point when I play the piano , when I am writing I hear that and that is what I am trying to get them to explore. I think for me Mulgrew , because I played with him the most, was able to…he was like a glove, when I would play, he knew how to open up those chords. It was almost like when Miles Davis with Herbie ( Hancock). Miles would play a note and Herbie and those guys would know what to do. What I try to do, it is the same thing with the pianist that play with me, try to get them to learn how to orchestrate and how to follow that and sometime not to (follow). They start to understand what is needed and what is not needed.

NOJ: You have incorporated more voice and chanting into your music. It was particularly effective in the haunting composition “Detroit” from Seeds. What is the sentiment that you are trying to portray in that moving song.

KG: At twelve o'clock every day in Detroit there was a radio announcer, her name was Martha Jean the Queen. Every day, every day she played the same song, I think it was a James Cleveland song. I think it was called “Without a Song” it wasn't the standard that we know, but I think that was the name of it. But everyday at twelve o'clock she would play this sad song. I would say “Wow , Really! “ But I remembered it , that’s the craziest thing, I remembered that haunting sense of that tune. So when I was writing I wanted to find a song to capture that feeling like “oh no not again”. I tried to capture the spirit of what that song meant to me.

NOJ: The song was beautiful but had a haunting, melancholy feel to it, I thought it was a statement about how far Detroit had fallen?

KG: Not so much that, of course that was part of me wanting to write a song for Detroit. They were going through some rough times but it will come back. Like every city it has to come back, hopefully sooner rather than later.

NOJ: The Iridium is presently your choice venue in New York. while it has a history of providing top talent jazz in recent years it has been more of a guitar-centric venue. What makes you feel right at home as a performer there?

KG: I first used to play a lot at Sweet Basil that was my home. And then they did something, they had a change or something so eventually I had to find another place and Ron ( Sturm, the Owner of Iridium) was able to allow me to come there when I wanted to play and so that became my new home. So when I come to New York that is where I go. I call him and say I am looking for some place to come and play and he has always been accommodating.

NOJ: So you will be playing at the iridium on May 22 through May 24th and who will be in the band?

KG: Vernell Brown playing piano, Rudy Bird, playing percussion, Mc Lenty Hunter playing drums and Corchran Holt playing bass. It is like the working band.

NOJ: Will you be introducing anything new?

KG: Every once in a while we try to throw in something new, I'am not sure if we will do that but mainly it will be a repertoire from the last two records.

NOJ: You have just been on tour in Europe recently?

KG: We just came back from Japan two days ago. We are in Europe a lot, traveling a great deal. It has been great, to go to Japan too. I was there last year doing the International Jazz with Herbie and the crew. We go to Europe a lot seems like we are there every other week (laughing).

http://www.popmatters.com/review/174718-kenny-garrett-pushing-the-world-away/

Kenny Garrett

Pushing the World Away

by Will Layman

16 September 2013

PopMatters

The gutsy, exuberant alto player emerges again with a heady mix of world sounds. Photo: Keith Major

Kenny Garrett is a workhorse jazz musician—a guy who has made plenty of recordings, who has a killer working band, and who gives his all in every show. Much of his work is brilliant. He has made long strings of records that have investigated different corners of the music with intelligence and searching discovery.

But in a long career, there have been stretches of relaxation also where he played too many easy blues licks or seemed to be recording songs that were designed simply to be “funky” pop songs that hardly tested his band or his talent. Those years with the aging Miles Davis taught him some bad habits as well as some brilliance.

Pushing the World Away is Good Garrett—and following up on a really wonderful 2012 record called Seeds from the Underground that was a flat-out cooker, this is a great sign.

I’d guess it’s not coincidence that the title of this disc contains “world” and “pushing”, as these songs cover lots of territory and move gracefully away from the pure swing feel that characterized so much of Garrett’s last disc. Garrett has long been playing pianist Benito Gonzalez, so the sweet Latin groove of “Chuco’s Mambo” is a natural, with percussionist Rudy Bird locking in with drummer Marcus Baylor to create a lovely feeling of dance and movement. And “J’ouvert” is a hopping and staccato calypso tune that is, naturally, an homage to Sonny Rollins in his “St. Thomas” mode but with a richer bed of percussion giving it float and ensemble interplay.

One of the most ambitious tunes here is the title track which builds on a rolling groove played by drummer Mark Whitfield, Jr. and piles a sinuous soprano saxophone melody atop a throaty chant that punctuates the arrangement. Garrett’s solo shifts into a sunny key over a vamp reminiscent of Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things”, but the pianist Vernell Brown muddies the harmonies so that things keep moving into stranger and more interesting territory. Garrett takes plenty of harmonic liberty, and the piece veers into the edge of the avant-garde. This tune is followed by “Homma San”, which uses a sprinkling of Latin percussion and a lovely wordless vocal as the etched shadow of Garrett’s melody on alto—a tune that is so lovely that nearly takes your breath away after the broiling intensity of “Pushing the World Away”.

This is a record that, indeed, pushes outward in many directions. It’s unusual, for example, to hear the leader performing on piano, but that’s him, fingers against keys, on his tribute to pianist and producer Donald Brown (who played with Garrett when both were in Art Blakey’s band), “Brother Brown”. And how lovely is it that Garrett has written out an accompaniment for violin, viola, and cello on this track? Very.

Much of the music here, however, has all the more typical Garrett virtues: swing, drive, and fire. “A Side Order of Hijiki” surges in a vintage post-bop vein, with Gonzalez playing like an up-to-date Tyner or Hancock around the edges of the melody and Baylor and his bass partner Corcoron Holt alternating between Latin syncopation and straight-ahead, four-on-the-floor uptempo walking. “Alpha Man” moves fast and slick as well, setting the melody as a tricky rhythmic counterpoint, but keeping the things moving on a very quick pulse played on the ride cymbal. “Rotation”, the closer, is a modern blues that would be a perfect tune on any jazz bandstand you can imagine, meat and potatoes and a heap of joy.