Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

BOBBY HUTCHERSON

September 10-16

GEORGE E. LEWIS

September 17-23

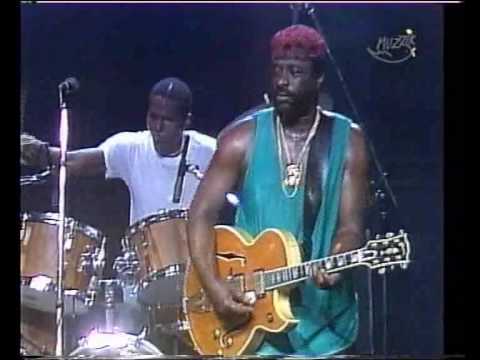

JAMES BLOOD ULMER

September 24-30

RACHELLE FERRELL

October 1-7

ANDREW HILL

October 8-14

CARMEN McRAE

(October 15-21)

PRINCE

(October 22-28)

LIANNE LA HAVAS

(October 29-November 4)

ANDRA DAY

(November 5-November 11)

ARCHIE SHEPP

(November 12-18)

WORLD SAXOPHONE QUARTET

(November 19-25)

ART BLAKEY

(November 26-December 2)

James Blood Ulmer

(b. February 2, 1940)

Artist Biography by Chris Kelsey

Free jazz has not produced many notable guitarists.

Experimental musicians drawn to the guitar have had few jazz role

models; consequently, they've typically looked to rock-based players for

inspiration. James "Blood" Ulmer

is one of the few exceptions -- an outside guitarist who has forged a

style based largely on the traditions of African-American vernacular

music. Ulmer is an adherent of saxophonist/composer Ornette Coleman's

vaguely defined Harmolodic theory, which essentially subverts jazz's

harmonic component in favor of freely improvised, non-tonal, or

quasi-modal counterpoint. Ulmer

plays with a stuttering, vocalic attack; his lines are frequently

texturally and chordally based, inflected with the accent of a soul-jazz

tenor saxophonist. That's not to say his sound is untouched by the rock

tradition -- the influence of Jimi Hendrix on Ulmer

is strong -- but it's mixed with blues, funk, and free jazz elements.

The resultant music is an expressive, hard-edged, loudly amplified

hybrid that is, at its best, on a level with the finest of the

Harmolodic school.

Ulmer began his career playing in funk bands, first in Pittsburgh (1959-1964) and later around Columbus, OH (1964-1967). Ulmer

spent four years in Detroit before moving to New York in 1971. He

landed a nine-month gig at the famed birthplace of bop, Minton's

Playhouse, and played very briefly with Art Blakey. In 1973, he recorded Rashied Ali Quintet with the ex-John Coltrane drummer on the Survival label. That same year, he hooked up with Ornette Coleman, whose concept affected Ulmer's

music thereafter. The guitarist's recordings from the late '70s and

early '80s exhibit a unique take on his mentor's aesthetic. His blues

and rock-tinged art was, if anything, more raw and aggressive than Coleman's free jazz and funk-derived music (a reflection, no doubt, of Ulmer's chosen instrument), but no less compelling from either an intellectual or an emotional standpoint. In 1981, Ulmer led the first of three record dates for Columbia, which helped to expose his music to a wider public. Around this time Ulmer began an association with tenor saxophonist David Murray, Bassist Amin Ali, and drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson. As the Music Revelation Ensemble,

this intermittent assemblage (with various other members added and

subtracted) would produce a number of intense, free-blowing albums over a

span of almost two decades.

Ulmer's work has varied in quality over the years. In 1987, with the cooperative group Phalanx (George Adams, tenor sax; Sirone, bass; and Rashied Ali, drums), Ulmer drew successfully on the free jazz expressionism that made his name. Generally, however, Ulmer's

interest in out jazz waned in the '80s and '90s, to the extent that his

music became progressively more structured, rhythmically regular, and

(arguably) less inventive. Much of his later work bears scant

resemblance to the edgy free jazz he played earlier. Nevertheless, '90s

recordings with the Music Revelation Ensemble showed him still capable of playing convincingly in that vein.

Blood dug deeply into an investigation of the blues

as the century turned. First he recorded Memphis Blood: The Sun Sessions

with guitarist Veron Reid both performing and producing. The album also

starred veteran Ulmer sideman Charles Burnham on violin. In 2003 he issued No Escape From the

Blues, recorded at Electric Lady studio. A thorouhgly psychedlic funky

take on the genre, Reid and Burnham were present in the same roles once

more, and old friend Olu Dara stopped into to contribute as well. In

2005 Blood released Birthright, on Joel Dorn's Hyena label. It is easily

his most intimatre recording. Completely solo in the studio (Reid once

again produced) it contains 10 orignals and two covers of classic

reportoire and takes Blood's blues journey to an entirely new level.

http://www.themorningnews.org/article/jazz-lessons-with-james-blood-ulmer

http://www.sevendaysvt.com/LiveCulture/archives/2013/11/05/an-interview-with-bluesman-james-blood-ulmer

James Blood Ulmer's music is equal parts blues, free jazz, funk and a lot of other things. He's a ferocious guitarist whose playing is tinted with shades of JimiHendrix, Sonny Sharrock, Gary Lucas and Son House, but his work is very strongly his own.

Ulmer has collaborated with Ornette Coleman, Vernon Reid, Bill Laswell, Art Blakey, Rashied Ali and countless others in his long and varied career. There's no other guitarist quite like him.

Ulmer recently spoke with Seven Days by phone from his home in NewYork City, in advance of his concert at the Flynn. The conversation began with a consideration of the best route to take when driving from New York Cityto Burlington.

Seven Days: There are so many different traditions winding through your music: blues, jazz, funk,soul, gospel. How do you define yourself, musically speaking? Does it even matter?

James Blood Ulmer: What I’m trying to be, what I’ll hopefully be, is … a change in music. I came up with a guitar style that was a totally different change, that sounds different from theregular sound of the guitar. … I’m always trying to make a difference, tryingto upgrade. Well, not upgrade, but change. I’m a guy who always wanted to take my guitar at high noon and play it at a Baptist church on Sunday … I’d like to play my guitar for the Baptist folks and have them not throw me out the door.

What is it about the blues that keeps bringing you back to it? Why is it so powerful and enduring?

Blues, I think, is very basic — the mother of jazz. That is the mother music.

My daddy didn’t allow us to listen to blues or hillbillymusic in the house. My daddy was a Christian man, and he was strict. I wasn’t allowed to play no blues as a child. I had to sneak out to hear the two guys in my town who played guitar. One was a blues player who used to drink White Lightning. Lived right in front of the church. The other man played gospel, but he drank alcohol, too! I had to sneak around and listento them.

I started in music backwards. I started in the gospel. At14, I stopped. I didn’t play no music until I graduated from high school andwent to Pittsburgh … At the end of the summer, when it was getting ready toget cold again, my cousin said, “Y’all got to get a job.”

I said, “Well, howmuch is the rent?” He said, “Six dollars a week.”

“Oh, wow, six dollars a week,”I said. “If I can get the six dollars a week without getting a job, would thatbe OK?”

“As long as you don’t steal it,” he said. Something had to happen, andthen I remembered: I knew how to play guitar.

Old bluesmen never played long solos on the guitar. It never

was about that. You never thought of Muddy Waters as a great guitar player. He was a bluesman. A bluesman has a story, and a way he tells the story. … Music and song begin to sound like scriptures. Not the Bible or anything, but a scripture in that it gives you the same feeling. It’s not about how good the guy is who’s playing the music. That’s what I try to keep away from.

http://www.furious.com/perfect/bloodulmer.html

Time For A Blood Transfusion

BLACK ROCK

James Blood Ulmer

Columbia, 1982

Music review by Kofi Natambu

Solid Ground: A New World Journal

Spring, 1982

Timing has always been a major factor in the emergence of seminal artistic figures in black creative music. In fact, one of the most consistent features in the history of the music has been the appearance of innovative individual artists (or ensembles) at a crucial period in the art’s development. Examples include Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane, the Art Ensemble of Chicago and Anthony Braxton, Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk, etc. While everyone has their favorite list the point is that as rich, fertile, and diverse as the tradition has been, there has always remained those singular forces that have played a pivotal role in the ascension of the music as a major international art-form. These individuals quickly become known as archetypes in Afro-American culture and serve as guides to the artistic future of American society. Rank hyperbole? Don’t look now: HERE COMES BLOOD!

Talk about timing. Just when it seemed that Jimi Hendrix would be the last truly creative guitar player that American would ever produce (with all due respect to your favorite fret’n mash strummer out there) James Blood comes roaring out of the loft underground in New York City in 1979, playing a riveting ‘pump and drive’ foil to the fiery byzantine lyricism of Ornette Coleman. Harmolodics meets whiplash guitar. The recording from this mighty union was entitled “The Tales of Captain Black” (on the small Artists House label), which introduced most listeners to the jagged quicksilver melodies that are now a Blood trademark. There was also a tortuous, aching (post?) romanticism that managed to sound ominously tough and unsentimental, yet intimate, warm, and compassionate all at once. This aspect of Blood’s multifaceted persona sounded like a brand new approach to the “ballad form.” However, the music is much more captivating than that academic phrase would suggest. Anyway, it was at this point that I became a flat-out Blood fanatic, endlessly playing the record for my musician-friends and setting some sort of record for playing it on my radio program. The release of Blood’s 1981 recording entitled Freelancing (this time for the huge conglomerate called CBS, INC.) confirmed his greatness for me. What 1 mean is, I played the music even more than before.

Now you might legitimately ask what does all of this have to do with Blood’s new record? Well, it is now a year later and Blood still has the same hypnotic effect that he always had. He does this simply by playing the hell out of the guitar and composing some of the most subtly rich and witty music I have ever had the privilege to hear.

What Blood does is not easily translatable in words. The music does not lend itself to flippant categorizing or easy analysis. To say that he uses the harmolodic method of instant modulation and orchestration that allows all members of an ensemble to play melodic lines at the same time does not really indicate the startling originality of the sound that is created. This distinctive sound resists standard definitions of genre, style, and idiom. It does not pander to fashionable trends nor does it play the listener cheap. It is a music of strength, grace, and eloquence that refuses to sacrifice humor, bravura, or even good time histrionics. No matter how “technical” and complex the music gets (and the forest gets plenty thick, indeed) it remains emotionally direct and powerful. In the ole days we would have said that the music “has a whole lotta heart and soul.” It is this sublime unity of virtuosity and feeling that gives Blood’s music its transformative powers.

Now for the evidence: consider the slashing and searing syncopations of the tune “Open House” or the faster-than-the-speed-of-sound precision of bass, drums, and guitar on “Overnight. “Juxtapose the manic out of of tempo careening of the harmolodic trio of Blood, Amin Ali (electric bass), and Grant Calvin Weston (drums) on “More Blood” to the almost pastoral funk sensualness on “Love Have Two Faces.” Listen to the throaty, hard-edged singing of Blood as he shouts, growls, moans, and croons on “Family Affair.” In fact, whenever the rich melisma of Blood’s bluesvoice mingles with the liquid gospelisms of vocalist Irene Datcher on this tune and “Love Have...” the impact is mesmerizing. The sound is so majestic, noble, and passionate that it makes a beautiful, heartfelt mockery of what passes for the “lovesong” genre today. Datcher and Blood brilliantly redefine the form and make you believe that REAL LOVE between Man and Woman is not only possible, but evident. A definite coup in ’82.

On top of all this, the “supporting cast” is astonishing. For starters one writer once described Amin Ali as “bionic.” That’s close. Frankly, to hear a man play electric bottom with this much power and ease at the demonic tempos that this band routinely sets, is scary. Need convincing? Listen to “Moon Beam,” “Fun House” and “Black Rock.” Or for blistering post-bop hysterics check out “We Bop.” Who says science, art, and the bootyshake don’t mix? Another taboo bites de dust. As for the rhythmic hummingbird that is Grant Calvin Weston: Where does a 22-year-old get off playing drums with the energy, drive, and dexterity of Elvin Jones, and the tonal sensitivity and finesse of the young Tony Williams? Not that I’m complaining, ya understand...

As for other major contributions to this Hoodoo stew, let’s not forget Sam Sanders. Thass right, Detroit’s own, of S.S. and Visions. I’m happy to note that the long-time “local” saxophone wizard plays like a man possessed on tenor and alto. Dig “Moon Beam,” “We Bop,” and “Overnight.” Burning and thrashing. And as for the Bloodbrother/vessel himself? He cuts, flails, strokes, rips, and rumbles his way through the liberated harmolodic jungle with an awe-inspiring HEROISM and CLARITY that gives one a lot more than mere hope. It gives you the tools and weapons to forge a New World with. If you listen you will hear that the truth is delight. As Blood says: “Love don’t mean a thing/if you don’t love somebody...”

http://www.scaruffi.com/jazz/ulmer.html

James Blood Ulmer

(Copyright © 2006

by Piero Scaruffi

South Carolina-born electric guitarist James "Blood" Ulmer (1942) relocated to New York in 1971. After playing with Ornette Coleman (1972-74), he developed an aggressive, edgy, jangled, dissonant style at the instrument that transposed Coleman's "harmolodic" free jazz coupled with Jimi Hendrix's psychedelic funk-blues-rock fusion (and loud amplification).

Revealing (1977), in a quartet with tenor saxophonist George Adams, bassist Cecil McBee and drummer Doug Hammond, contained four lengthy jams (particularly Revealing and Overtime). Ulmer used the same kind of quartet, but with Ornette Coleman on alto saxophone and Jamaladeen Tacuma on bass, on the more famous but less adventurous Tales From Captain Black (december 1978), containing eight short pieces. The difference was not so much Coleman, but Tacuma, thanks to whom the sound became visceral and funky. Are You Glad To Be In America (january 1980), with the formidable rhythm section of drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson and bassist Amin Ali, was structured again as a series of (ten) demonstrations (notably Lay Out and Time Out) of Ulmer's potential, somewhere between the Pop Group and Bill Laswell's Material.

Ulmer returned to the extended free-jam format of Revealing with the Music Revelation Ensemble, a quartet with tenor saxophonist David Murray, bassist Amin Ali and drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson. No Wave (june 1980) contained four energetic pieces, particularly Time Table, Big Tree and Baby Talk.

But the albums under his own name valued instead structure and brevity. Increasing the ferocity of his attack via Free Lancing (1981), whose Timeless was almost punk-rock, Ulmer achieved the brutal peak of Black Rock (1982), debuting flutist Sam Sanders and coupling Ali's bass with drummer Grant Calvin Weston, a collection that ran the gamut from hardcore (Open House) to free-jazz (We Bop) and focused on the middleground, a radio-friendly fusion of hard-rock and funk music (Black Rock). The idea was ready for mass consumption, and Ulmer, accompanied only by violin and drums, and relying ever more on his vocals, found a huge audience with Odyssey (may 1983),

Ulmer teamed up with tenor saxophonist George Adams and created the quartet Phalanx. Their Got Something Good For You (september 1985) featured Ali and Weston, whereas Original (february 1987) and In Touch (february 1988) boasted bassist Norris "Sirone" Jones and drummer Rashied Ali.

America Do You Remember the Love? (september 1986) was a jazz-rock quartet session with guitarist Nicky Skopelitis, bassist Bill Laswell and Ronald Shannon Jackson, heavily influenced by Laswell's ambient/world philosophy.

Blues Allnight (may 1989) was a detour into blues-rock.

Ulmer finally resurrected the Music Revelation Ensemble (with Jamaaladeen Tacuma replacing Ali) for Music Revelation Ensemble (february 1988), indulging in six free-form jams (notably Body Talk, Playtime, Nisa). The rhythm section changed (Amin Ali and drummer Cornell Rochester) for Elec Jazz (march 1990), that had the free-jazz workout Big Top (in two parts), Exit (also in two parts), the eight-minute ballad No More and the ten-minute Taps Dance. After Dark (october 1991) contained Maya, the 12-minute avant-ballad Never Mind, and After Dark, his first experiment with a string quartet. Basically, as Ulmer moved away from free jazz in his albums, he moved back into free jazz with the Ensemble.

Ulmer's most ambitious album, Harmolodic Guitar with Strings (july 1993) contained three multi-movement suites for guitar and string quartet (Arena, Page One, Black Sheep), each movement being very short.

With Murray replaced by guest saxophonists (Arthur Blythe on alto in Non-Believer, Hamiet Bluiett on baritone in The Dawn, or Sam Rivers on soprano in In Time, on tenor in Help and on flute in Mankind), the Music Revelation Ensemble rode the cacophonic maelstrom of In The Name Of (december 1993). The funkier Knights of Power (april 1995) was less terrifying, but still contained powerful pieces such as Convulsion (with Bluiett) and The Elephant (with Blythe). Cross Fire (december 1996), with bassist Calvin Jones replacing Ali, used Pharoah Sanders' tenor saxophone (notably in My Prayer) and John Zorn's alto saxophone. These Ensemble albums were also vehicles for Ulmer to showcase his supernatural technique at the guitar, freed from the song-oriented constraints of his solo albums.

The albums recorded under his own name since the mid 1990s were mostly uninspired ventures into blues music (and his vocals did not help). The best ones, the oddly psychedelic Memphis Blood (april 2001), No Escape From the Blues (april 2003) and Bad Blood In The City - The Piety Street Sessions (december 2006), were collaborations with rock guitarist Vernon Reid.

Birthright (2005) was a solo album. In And Out (august 2008) featured a quartet with flute. Live at the Bayerischer Hof documents a collaboration with bassist Amin Ali and drummer Aubrey Dayle

http://www.nytimes.com/2002/07/30/arts/jazz-review-singing-spooky-and-brash-blues.html

ARTS | JAZZ REVIEW

JAZZ REVIEW: Singing Spooky And Brash Blues

By BEN RATLIFF

JULY 30, 2002

New York Times

In common practice, the shortest route to electric blues music is to the good-time kind: wry, midtempo, rocking and made for sports bars. But James Blood Ulmer, a guitarist best known over the last 25 years as a vanguard-dwelling semi-jazz musician, has the power to overthrow that amiability for a spooky netherworld. And he did it at several crucial moments during a performance last Tuesday at Rockefeller Park in Battery Park City.

Mr. Ulmer is associated with a subset and generation of jazz musicians in New York in the 1970's and 80's who were brash and prickly and outward bound; they weren't interested in reupholstering the past. So even though blues and gospel were in his own professional history -- as a musician in South Carolina, Pittsburgh and Columbus before he moved to New York in 1971 -- you wouldn't hear him playing blues standards. That was the case until last year, when another guitarist, Vernon Reid, took him into the Sun Studios in Memphis, and together they made ''Memphis Blood'' (Label M).

On that album, and in last Tuesday's concert, the formula was pretty well laid out: Mr. Ulmer, playing gently with his fingers, laid out the harmonically watery backgrounds, Mr. Reid played the flashy solos and tight obbligatos, and the rhythm section bumped along loudly or softly, as the situation demanded. In John Lee Hooker's ''Dimples,'' the band played through a long, lean one-chord vamp, creating marvelous tension; Mr. Reid punctuated the mystery with barbed, pulled-string chords. And ''Little Red Rooster,'' as slow as water freezing, was another high point; the violinist Charlie Burnham played sweet double-stopped blues figures behind the guitarists.

These songs tilted toward the natural strengths of Mr. Ulmer, with his irresolute, semi-droning and semi-dissonant guitar style and his froggy voice; he roughed them up, made them obscure. Some others, like ''Money (That's What I Want)'' and ''Fattening Frogs for Snakes,'' were experiments in entropy: the band was looking around, hoping for something chilling to happen, and not much did. (At one other memorable point, Mr. Reid snapped everyone to attention amid Otis Rush's minor blues ''Double Trouble'' with a soaring, superstar rock 'n' roll solo.)

The concert's setting outdoors on a pleasant summer day, with the sun setting on the Hudson behind the crowd, may have worked against the dark-souled songs. But at its best, the concert communicated perfectly well how deep the blues runs in Mr. Ulmer's music.

http://www.nytimes.com/1981/10/04/arts/a-very-special-guitarist.html

A VERY SPECIAL GUITARIST

by ROBERT PALMER

October 4, 1981

New York Times

James Blood Ulmer plays the electric guitar. So do countless professional, semiprofessional and amateur musicians the world over, but none of them sounds like Mr. Ulmer. He has shared concert stages with Ornette Coleman and other jazz artists and with forward-looking rock performers like Public Image Ltd. and Captain Beefheart, and he has been enthusiastically reviewed by jazz and rock critics. But his few recordings have been for independent labels, and he has been little heard outside New York City, where he lives, and a few European cities. That situation will change later this month when Columbia Records releases Mr. Ulmer's new album ''Free Lancing.'' Although it is actually his fourth LP, it will probably be the first of his recordings to penetrate beyond the small circle of new-music devotees that has been aware of his work all along. And it confirms what these devotees have been saying for several years now - that Mr. Ulmer is the most original electric guitarist to emerge since the late Jimi Hendrix, who made his most influential recordings between 1967 and 1970.

The comparison to Jimi Hendrix isn't entirely inappropriate; Mr. Ulmer's singing voice is very reminiscent of Mr. Hendrix's. But Mr. Ulmer sings only occasionally. Three of the 10 selections on ''Free Lancing'' are vocals, and of his earlier albums, only one, ''Are You Glad to Be in America?,'' includes any singing whatsoever. Nor is Mr. Ulmer a flamboyant performer in the Hendrix mode. His vocals can be winning, as they are on the Columbia album, but they are not the main attraction. On the stage and on records, he is first and foremost a guitarist.

Mr. Ulmer, who was born and grew up in South Carolina, played rhythm-and-blues before becoming involved in avant-garde jazz in the early 1970's. He made his first jazz recordings with a group led by the drummer Rashied Ali, but it was only after he became involved with the saxophonist Ornette Coleman in the mid-70's that his style really crystalized. Mr. Coleman is the originator of a theory he calls ''harmolodics'' - the term is a contraction of the words harmony, motion and melodic. In a nutshell, the harmolodic theory overturns more traditional methods of improvisation by allowing spontaneous melodies to generate appropriate chord sequences; in traditional improvising, the player builds melodies on top of predetermined chord sequences, usually sequences derived from popular songs or the blues. Mr. Ulmer's approach to harmolodic playing emphasizes melodies that are often quite lyrical, but as he develops these melodies in his improvisations he throws in bursts of dissonant chording and jagged phrases that eventually lead him far afield. His habit of returning to his original melodies in a surprising but perfectly logical manner is one of the most engaging aspects of his playing.

Much has been made of Mr. Ulmer's debt to Ornette Coleman, but he was playing in a style roughly similar to his present one before he began working with Mr. Coleman. His study of harmolodics did bring focus and depth to his playing, and his use of dance rhythms closely parallels Mr. Coleman's work with the electric band Prime Time. But Mr. Coleman and Prime Time strive for a kind of melodic counterpoint in which each instrument plays an equally important part, and Mr. Ulmer is very definitely a guitar soloist, supported by a rhythm section and, occasionally, by a horn section and background vocalists.

Mr. Ulmer's rhythm section (Amin Ali on electric bass and G. Calvin Weston on drums) has developed a style that is as original as his guitar playing. They pump out kinetic dance rhythms without constricting Mr. Ulmer's freedom of movement; in fact, Mr. Ali often seems to be feeding the guitarist ideas, and Mr. Weston has come up with some fascinating, multidirectional drum patterns that are wholly his own. On four of the 10 selections on ''Free Lancing'' Mr. Ulmer, Mr. Ali a nd Mr. Weston work as a trio, and their redefinition of rock's familiar ''power trio'' instrumenta tion is both radical andutterly assured. Three more selections add a horn section drawn from the best of New York's jazz avant-garde; each of the players (Olu Dara on trumpet, Oliver Lake on alto saxophon e and David Murray on tenor saxophone) gets a brief solo. The three remaining selections find Mr. Ulmer singing, with second guitar by Ronnie Drayton and three backup vocalists. His songs are as melo dically fresh as his instrumental compositions; ''Where Did All th e Girls Come From'' is catchy enough to get some airplay, though it doesn't compromise Mr. Ulmer's originality one bit.

Recording for independent labels before graduating to Columbia did not do Mr. Ulmer any harm. In fact, his earlier albums now sound like rehearsals for ''Free Lancing,'' which is the most intelligently balanced and cleanly recorded of all his disks. He record ed his first album, ''Tales of Captain Black'' (Artists House Records), in 1978, with Or nette Coleman playing alto saxophone and co-producing. The bassist, Jamaaladeen Tacuma, plays spectacularly, and Ornette Coleman's son Denardo is a capable drummer, but this is not a rhythm section that shows off Mr. Ulmer to best advantage. The album is notable for h is exciting guitar playing and for Mr. Coleman's solos, and for the i ndividual contributions of the members of the rhythm section, but it does not offer a coherent ensemble style.

By January 1980, when Mr. Ulmer recorded ''Are You Glad to Be in America?'' for Britain's Rough Trade label, he had made considerable progress in this direction. The rhythm section and horn section were the same players who appear on ''Free Lancing,'' but with a second drummer, Ronald Shannon Jackson, added. The problem with the second album is a somewhat murky sound; the performances are first-rate. Now that Mr. Ulmer is recording for Columbia, another major label has been negotiating for the right to release ''Are You Glad to Be in America?'' in this country.

''No Wave,'' Mr. Ulmer's third album, was recorded for the German Moers Music label in June 1980. It is more a free-form jam session than a program of tightly arranged compositions and is the least successful of the guitarist's recordings. Mr. Ulmer is most effective when he delivers terse, condensed performances of his distinctive compositions. But not even the performances on ''Are You Glad to be in America?,'' the best of the earlier records, matches the lucid organization and inspired improvising captured on ''Free Lancing.'' Moving to a major label can sometimes stifle an artist's creativity, but Mr. Ulmer was ready for the move and has made an album that should delight the fans he now has and win him many new ones.

http://www.sfgate.com/entertainment/article/He-s-Been-Working-On-the-Third-Rail-Jazz-2832096.php

It's been several years since intrepid guitarist James "Blood" Ulmer

brought his funk-ignited jazz to town. Why so long? According to the

New York-based avant-funkster, it's been a case of waiting "for the

right moment and the right conditions." Hot on the heels of a cooking

new album, "South Delta Space Age," by his star-studded band Third Rail

-- appropriately named for a subway's power source that can de liver the

jolt of your life -- he figured the time was finally right to take a

cruise to the West Coast.

"I've been working on lots of different projects over the last couple of years," the raspy-voiced Ulmer said shortly before embarking with the group to perform at the North Sea Jazz Festival in the Netherlands. "But I had to get on that third rail to find my way back to San Francisco."

Originally conceived as a power trio with bassist Bill Laswell and drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson, Third Rail played one concert in Zurich, Switzerland, in 1990 and slayed the crowd. But then the band got off track. "We went into the studio and cut a bunch of tunes, but nothing ever happened," said Ulmer, who admits to still being perplexed by the lack of forward motion.

"You know, I don't even know what happened. Something just didn't work out. But I couldn't stop thinking about it. One day I called Bill and said this thing had been lingering too long. He agreed, and we got the project rolling again."

With the recent resurgence of interest in jazz-funk crossover, especially among younger audiences hungering for edgy grooves, the timing couldn't have been better.

After Laswell scored a deal with a Japanese label, he and Ulmer enlisted a group of simpatico musicians to put the spark and sizzle into the guitarist's compositions: former Parliament-Funkadelic keyboardist Bernie Worrell, jazz-gospel organist Amina Claudine Myers and ex-Meters drumming ace Joseph "Zigaboo" Modeliste (spelled by Jerome Brailey for Third Rail's appearance at Bimbo's 365 Club this Saturday).

"In the past, I worked a lot with younger musicians, being a schoolteacher to them," Ulmer said. "With -- Third Rail, I was playing with people I didn't have to worry about. Everybody has their own musical concept. I didn't have to tell them anything. Can you imagine me telling Zigaboo what beats to play? I presented my music, and he let me know the beat. And Bernie, all he needs to know is the name of the song and he's gone. That's why we're the Third Rail. It's the power. I never went head-on like this before."

"South Delta Space Age," which Antilles licensed to release in the United States, is both tethered to earth with Delta blues grit and spun into orbit with soaring improvisation. The band offers a mesmerizing take on hip-hopper Schooly D's "Dusted" and builds the funk fire with "Funk All Night," "Itchin' " and "First Blood," free-spirited and intoxicating Ulmer originals fueled with jazz and soaked in blues, rap, soul and rock.

Laswell's and Modeliste's phat beats are charged, and there's plenty of open space for Worrell's sonic booms on organ and clavinet. But Ulmer firmly commands center stage with his grainy party-time vo cals and distinctive blues-toned guitar voicings -- searing riffs, blistering single-note runs, quaking chords and a ton of tonal distortion. Ulmer came up through the jazz ranks in the early '70s as a disciple of Ornette Coleman and his school of harmolodics. After exercising his groove licks in R&B organ ensembles, the guitarist took his music to a new level while gigging with Coleman's group Prime Time.

During this period, Ulmer developed his own style, which he called harmolodic diatonic funk, and set out to explore a new musical language informed by the organic rhythms of country blues and the dissonant outbursts of avant-jazz. In the wake of his debut solo album, "Tales of Captain Black," produced by Coleman, Ulmer was heralded as the missing guitar link between Wes Montgomery and Jimi Hendrix.

Ulmer continues to acknowledge the impact of Coleman with his latest solo album, "Music Speaks Louder Than Words" (DIW/Koch Jazz), a rousing collection dominated by compositions written by the free-jazz maestro. "I set out to do something special for Ornette," Ulmer said. "I wanted to express his music from the perspective of a guitarist." Interspersed in the collection are three of Ulmer's funk tunes, pop- ish excursions that instead of disrupting the harmolodic flow actually serve as palate-cleansing pauses. A highlight is "Rap Man," Ulmer's perky tune that in the funky chorus sounds like a cross between the "Batman" and "Ghostbusters" themes.

Ulmer promises to mix a couple of those tunes into the show at Bimbo's. "That's what Third Rail is all about: expressing my verbal music. I've been recording instrumental music for Ry Cooder's soundtrack of Wim Wender's new film 'The End of Violence' and touring with John Zorn and Pharoah Sanders in another one of my projects, Music Revelation Ensemble. But with Third Rail I get to sing. That's when I get to have a lot of fun."

http://www.metrotimes.com/detroit/james-blood-ulmer-returns-for-the-detroit-jazz-festival/Content?oid=2364506

One:

AN A.R.M. PRODUCTION

James Blood Ulmer - Free Lancing-- [Columbia, 1981]

Yehezkel z Wykopu

1/10 videos:

James Blood Ulmer - "Black Rock”—Columbia, 1982:

James Blood Ulmer--"Church"--From the 'Odessey' LP on Columbia Records, 1984:

'Odyssey' is an album by American guitarist James Blood Ulmer, recorded in 1983 and released on the Columbia label.[1] It was Ulmer's final of three albums recorded for a major label. The musicians on this album later re-united as The Odyssey Band and Odyssey The Band:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Blood_Ulmer

James "Blood" Ulmer (born February 2,1940) is an American jazz, free funk and blues guitarist and singer. Ulmer plays a semi-acoustic guitar. His distinctive guitar sound has been described as "jagged" and "stinging". Ulmer's singing has been called "raggedly soulful".[1]

Ulmer was born in St. Matthews, South Carolina. He began his career playing with various soul jazz ensembles, first in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, from 1959–1964, and then in the Columbus, Ohio region, from 1964–1967. He first recorded with organist Hank Marr in 1964 (released 1967). After moving to New York in 1971, Ulmer played with Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, Joe Henderson, Paul Bley, Rashied Ali and Larry Young.

In the early 1970s, Ulmer joined Ornette Coleman; he was the first electric guitarist to record and tour extensively with Coleman. He has credited Coleman as a major influence, and Coleman's strong reliance on electric guitar in his fusion-oriented recordings owes a distinct debt to Ulmer.

His appearance on Arthur Blythe's two consecutive Columbia albums, Lenox Avenue Breakdown and Illusions, was followed by Ulmer's signing to that label. That resulted in three albums: Free Lancing, Black Rock, and 1983's Odyssey, which was the inaugural release of his Odyssey The Band with drummer Warren Benbow and violinist Charles Burnham, a trio that has continued to perform and record to this day. It was described at the time as "avant-gutbucket", leading writer Bill Milkowski to describe the music as "conjuring images of Skip James and Albert Ayler jamming on the Mississippi Delta."

He formed a group called the Music Revelation Ensemble circa 1980, initially co-led with David Murray for the first decade, that lasted into the mid-90s. Later recorded incarnations of the group featured either Arthur Blythe, Sam Rivers, Pharoah Sanders or John Zorn on saxophones. In the 1980s he co-led, with saxophonist George Adams, the Phalanx quartet.

Ulmer has recorded many albums as a leader, including a recent quartet of acclaimed blues-oriented records produced by Vernon Reid: Memphis Blood, No Escape from the Blues, Bad Blood in the City, and the solo guitar & vocals album Birthright.

Ulmer was a judge for the 8th annual Independent Music Awards to support independent artists.[2][3]

In a 2005 Down Beat interview, Ulmer opined that guitar technique had not advanced since the death of Jimi Hendrix.[4] He stated that technique could advance "if the guitar would stop following the piano," and indicated that he tunes all of his guitar strings to A.[4]

In 2009, Ulmer started his own label, American Revelation, which has released four CDs to date; all are available only from his website, or at his shows.

In spring 2011, Ulmer joined saxophone luminary James Carter's organ trio as a special guest along with Nicholas Payton on trumpet for a six-night stand of performances at Blue Note New York.

"James Blood Ulmer". TrouserPress.com. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

"Boston's Own Debbie And Friends Among The 8th Annual Independent Music Awards Vox Populi Winners". PRLog. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

[1] Archived April 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

http://www.themorningnews.org/article/jazz-lessons-with-james-blood-ulmer

Profiles

Jazz Lessons With James “Blood” Ulmer

Growing up in a family that requires Saturday night recitals

is a crash course in how to please a crowd. A conversation about a

lifetime of commanding performances.

“Have I seen you before?” guitarist James “Blood” Ulmer asks as he

ushers me into his home. His question catches me off guard. Over the

years, I had seen Ulmer plenty of times. I had marveled at his

captivating fusion of jazz and funk, his ineffable scampering note

sequences and the raw granularity of his voice. But we had never met.

He offers me a seat at his breakfast table. Afternoon sunlight fills his spacious SoHo apartment, bathing an assortment of plants asymmetrically arranged along a row of expansive windows that open onto the street below. He picks up my flat microphone and examines it, turning the wafer-thin accessory over in his powerful hands. There’s a gracefulness in the way he handles the gadget, and I see an immediate correlation with the fluidity in which his fingers dance across the fretboard. Ulmer started out as a guitarist at age four in rural St. Matthews, S.C., shortly after the Second World War.

“When I was a kid, everyone in the family had to perform something on Saturday night,” he says. “All the big families in the South did that. You had to dance, speak, sing, whatever you did. I played guitar, and when I was nine years old, I did some quartet singing in a group called the Southern Sons. We made a little money, too.”

Ulmer traveled to New York City as a teenager in the late ‘50s while he was touring with a rhythm-and-blues band. But his artistic identity crystallized in Detroit, where he settled in 1965 and became immersed in the city’s notorious music scene, subjecting himself to ruthless self-analysis in an attempt to fashion his own guitar style. By 1969, he had become part of the lineup alongside organist “Big” John Patton and appeared on the album Accent on the Blues, which got some airplay and exposed Ulmer to a wider audience.

“Detroit was a very musical town,” he explains. “Every musician was searching for something, stretching beyond what Miles and them were doing, even though they were studying Miles at the same time. And in them days, Wes Montgomery was the indisputable champion of the guitar. But when I was in Detroit, I got away from the Wes Montgomery concept and started playing free. I came out of Detroit playing free music.”

Free music, also called free jazz, was developed in the late ‘60s by saxophonist Ornette Coleman and pianist Cecil Taylor. Coleman and Taylor never collaborated and took distinctly different approaches to composition, but both artists broke away from the predetermined melodic phrases that normally define jazz. Coleman called his method “harmolodics.” For him, melodies evolved from the musician’s intuitive responses to one another outside the framework of traditional rhythmic structures and harmonic chord progressions.

“When I moved to New York in ‘71, I had a little storefront studio in Brooklyn,” Ulmer says. “One night, Billy Higgins [Coleman’s drummer] stopped by to play my drums and told me, ‘Coleman wants to hear you.’ So he took me to Coleman’s house, where I lived for almost a year. And when I started playing with Coleman, he said that I was a natural harmolodic player. He was a mentor to me. He validated what I was doing.”

In 1978, Ulmer released Tales of Captain Black with Coleman on alto saxophone and as producer. Like most free-jazz compositions, the songs on the album have no rhythmic center, and although bassist Jamaaladeen Tacuma incorporates traces of funk, he frequently changes tempo, purposely shifting the bassline out of sync with the erratic pulse of drummer Denardo Coleman, Ornette’s son. On each of the numbers, Ulmer and Ornette Coleman bounce spasmodic phrases off one another, skirting in and out of kaleidoscopic rhythms. Tales of Captain Black could serve as a textbook example of what free jazz is all about.

And yet, such categorization is what Ulmer has sought to defy over the course of his career. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, his music exhibited a bluesier edge, and Odyssey, a 1983 release with Charlie Burnham on violin and Warren Benbow on drums, even contains bluegrass elements. The lineup is conspicuously missing a bassist, and when I mention this to Ulmer, he notes that in a jazz ensemble, an electric bass has a tendency to “lock down” other instruments, especially the guitar. By default, the electric bassist and guitarist wind up in a shared leadership role that imposes limitations on both artists and compromises their ability to improvise freely.

Projects with bassist Bill Laswell seem to be Ulmer’s lone exception to this rule. Laswell is arguably one of the greatest electric bassists of all time and played with Ulmer in the mid-’90s on South Delta Space Age, a fusion of jazz, blues, and funk that also included Parliament/Funkadelic keyboardist Bernie Worrell. Pianist Amina Claudine Myers and drummer Joseph Modeliste fleshed out this second incarnation of Third Rail, an Ulmer combo.

“Now that was a heck of a lineup,” Ulmer recalls. “The original Third Rail was me, Bill, and [Ronald] Shannon Jackson. And Bill and I had worked together on an earlier record of mine called America: Do You Remember the Love? But we didn’t want the [Third Rail] project to be under any one person’s name, so Bill brainstormed and came up with a name for the group and an album title. Bill is great with words—coming up with names, titles, and stuff like that.”

In 2001, Laswell and Worrell returned to support Ulmer on his album Blue Blood, a superb blend of jazz and blues. And although there’s a guitarist and bassist on the record, neither Ulmer nor Laswell seems constrained by the other’s playing. If anything, they’re liberators, forging ahead with their distinct musical voices, expanding the aural dimensions of each song and providing additional creative space for one another to work. Ulmer’s leads and Laswell’s basslines are so intricate and sophisticated that there’s no way that they could be interwoven; instead, they’re overlaid, giving both instruments equal prominence in every song. [Listen to “Momentarily”]

“Music is something you do to bring people a message—to give them something to hold on to and help them remember. And that hurricane can never, never, never, ever be forgotten.” Also in 2001, Vernon Reid (Living Colour, Yohimbe Brothers), one of rock’s finest guitarists, began working with Ulmer on Memphis Blood, which would later receive a Grammy nomination for best traditional blues album. At first, Ulmer was reluctant to do the project. He had been raised on spiritual music, and with his father a minister, the risqué lyrics of many traditional blues classics had not been welcome in the household. In fact, Ulmer outright refused to record some of the songs that Reid, the producer, had suggested for the album.

“Vernon chose all the material,” Ulmer explains. “But I had to reject some of the songs. Now, ‘Back Door Man’—I didn’t want to sing that song because I ain’t no back-door man. I couldn’t tell nobody, ‘I’m a back-door man.’ I’m a front-door man. That one got on the album, though, but I’ve never performed it at a gig. You got to be careful about those songs. [Before Memphis Blood] I had never thought of doing a traditional blues record. So when Vernon made the suggestion, it was like a challenge to see if I could actually sing those songs. And it was almost like singing in church. When you’re singing in church, you’re not singing about nothing except God. So when you’re singing blues you can get a similar feeling—that you’re singing about something that’s not about you. Like ‘Spoonful’—that song is about coffee!” Ulmer exclaims, laughing. “Coffee and tea and diamonds and gold—and I don’t have none of it, so that song definitely wasn’t about me!” [Listen to “Spoonful”]

Since 2003, Reid has produced three more Ulmer albums that exhibit radically different takes on the blues idiom. No Escape From the Blues builds on the soulful, electric sound of ‘50s Chicago, while Birthright hails back to the solo-acoustic sessions of blues legend Robert Johnson’s recordings. Ulmer penned most of the material on Birthright, a collection of solemn, intensely personal songs.

“The song ‘Geechee Joe’ is about my grandfather,” he says. “I loved Geechee Joe and I had to write that song so my brothers and sisters could remember their granddad. And [Geechee Joe] did not want to work for the white man. He wasn’t working for no 50 cent’ a day. That was the message I was trying to get across. And he left everybody in South Carolina and went to Pittsburgh, where he became a freelance construction worker and numbers runner. He never took a job where he wasn’t the boss. It’s a true song.” [Listen to “Geechee Joe”]

In December 2006, Ulmer, Reid, and the Memphis Blood Blues Band headed down to New Orleans to record Bad Blood in the City,

an artistic reaction to the devastation wrought on the urban poor by

Hurricane Katrina. Ulmer’s passionate lyrics denounce the U.S.

government’s response to the disaster, and Reid exhibits some of his

best soloing since his heydays with Living Colour.

In December 2006, Ulmer, Reid, and the Memphis Blood Blues Band headed down to New Orleans to record Bad Blood in the City,

an artistic reaction to the devastation wrought on the urban poor by

Hurricane Katrina. Ulmer’s passionate lyrics denounce the U.S.

government’s response to the disaster, and Reid exhibits some of his

best soloing since his heydays with Living Colour.

“Most of the songs on the album are based on stories I got from watching CNN,” Ulmer says. “Music for me is something you do to bring people a message—to give them something to keep, to hold on to and help them remember. And that hurricane can never, never, never, ever be forgotten. Somebody said to me, ‘Blood, it’s been a year now. Don’t you think it’s a little too late to write about [Katrina]?’ Too late? I never thought about it that way. I’m shocked that people are waiting for the whole thing to pass over.” [Listen to “Survivors of the Hurricane”]

In May, Ulmer and the Memphis Blood Blues Band kicked off their tour to promote Bad Blood in the City with a phenomenal performance at the Rich Forum in Stamford, Conn. Reid, whose astonishing guitar work is featured on the new album, remained low-key during the show and all but silenced himself four songs into the set after a fan shouted, “More Blood Ulmer in the mix!”

For nearly two hours Ulmer dexterously wove earthy, expressive leads through the other musicians’ robust rhythmic and harmonic textures, accentuating the inimitable tension and resolution that defines his solos. When someone shouted “Blood Ulmer for President!” the band answered with a rollicking rendition of Willie Dixon’s “Dead Presidents,” a song that, along with three other Dixon covers, showcased Ulmer’s searing vocals. Throughout the performance, Reid diligently provided steady rhythmic support on every number and backing vocals on Dixon’s “I Love the Life I Live (I Live the Life I Love).” That night, Rich Forum epitomized what live music is all about—a mutual elation and joy shared by both the artists and the spectators.

Ulmer roars with laughter when he recalls the days when audiences weren’t so enthusiastic. “When I was with Coleman, people would get up and leave while we were playing because they hadn’t heard anything like it before,” he says. “And when we didn’t want to get bogged down with people moving around during the performance, we’d just tell them flat out, ‘Anybody who doesn’t want to hear this shit, just get up and leave now so we can have some fun!’“

“Many musicians have lost touch with what art is,” he adds. “It has become watered down so badly. Music has to represent something, but it has become too integrated. Martin Luther King integrated people. But now, you’ve got integrated music—people combining some shit to the point where it don’t mean nothing to nobody,” he says, laughing. “As a musician, you have a job to do. You’re a representative of someone’s culture and your music has to represent something, too.”

He offers me a seat at his breakfast table. Afternoon sunlight fills his spacious SoHo apartment, bathing an assortment of plants asymmetrically arranged along a row of expansive windows that open onto the street below. He picks up my flat microphone and examines it, turning the wafer-thin accessory over in his powerful hands. There’s a gracefulness in the way he handles the gadget, and I see an immediate correlation with the fluidity in which his fingers dance across the fretboard. Ulmer started out as a guitarist at age four in rural St. Matthews, S.C., shortly after the Second World War.

“When I was a kid, everyone in the family had to perform something on Saturday night,” he says. “All the big families in the South did that. You had to dance, speak, sing, whatever you did. I played guitar, and when I was nine years old, I did some quartet singing in a group called the Southern Sons. We made a little money, too.”

Ulmer traveled to New York City as a teenager in the late ‘50s while he was touring with a rhythm-and-blues band. But his artistic identity crystallized in Detroit, where he settled in 1965 and became immersed in the city’s notorious music scene, subjecting himself to ruthless self-analysis in an attempt to fashion his own guitar style. By 1969, he had become part of the lineup alongside organist “Big” John Patton and appeared on the album Accent on the Blues, which got some airplay and exposed Ulmer to a wider audience.

“Detroit was a very musical town,” he explains. “Every musician was searching for something, stretching beyond what Miles and them were doing, even though they were studying Miles at the same time. And in them days, Wes Montgomery was the indisputable champion of the guitar. But when I was in Detroit, I got away from the Wes Montgomery concept and started playing free. I came out of Detroit playing free music.”

Free music, also called free jazz, was developed in the late ‘60s by saxophonist Ornette Coleman and pianist Cecil Taylor. Coleman and Taylor never collaborated and took distinctly different approaches to composition, but both artists broke away from the predetermined melodic phrases that normally define jazz. Coleman called his method “harmolodics.” For him, melodies evolved from the musician’s intuitive responses to one another outside the framework of traditional rhythmic structures and harmonic chord progressions.

“When I moved to New York in ‘71, I had a little storefront studio in Brooklyn,” Ulmer says. “One night, Billy Higgins [Coleman’s drummer] stopped by to play my drums and told me, ‘Coleman wants to hear you.’ So he took me to Coleman’s house, where I lived for almost a year. And when I started playing with Coleman, he said that I was a natural harmolodic player. He was a mentor to me. He validated what I was doing.”

In 1978, Ulmer released Tales of Captain Black with Coleman on alto saxophone and as producer. Like most free-jazz compositions, the songs on the album have no rhythmic center, and although bassist Jamaaladeen Tacuma incorporates traces of funk, he frequently changes tempo, purposely shifting the bassline out of sync with the erratic pulse of drummer Denardo Coleman, Ornette’s son. On each of the numbers, Ulmer and Ornette Coleman bounce spasmodic phrases off one another, skirting in and out of kaleidoscopic rhythms. Tales of Captain Black could serve as a textbook example of what free jazz is all about.

And yet, such categorization is what Ulmer has sought to defy over the course of his career. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, his music exhibited a bluesier edge, and Odyssey, a 1983 release with Charlie Burnham on violin and Warren Benbow on drums, even contains bluegrass elements. The lineup is conspicuously missing a bassist, and when I mention this to Ulmer, he notes that in a jazz ensemble, an electric bass has a tendency to “lock down” other instruments, especially the guitar. By default, the electric bassist and guitarist wind up in a shared leadership role that imposes limitations on both artists and compromises their ability to improvise freely.

Projects with bassist Bill Laswell seem to be Ulmer’s lone exception to this rule. Laswell is arguably one of the greatest electric bassists of all time and played with Ulmer in the mid-’90s on South Delta Space Age, a fusion of jazz, blues, and funk that also included Parliament/Funkadelic keyboardist Bernie Worrell. Pianist Amina Claudine Myers and drummer Joseph Modeliste fleshed out this second incarnation of Third Rail, an Ulmer combo.

“Now that was a heck of a lineup,” Ulmer recalls. “The original Third Rail was me, Bill, and [Ronald] Shannon Jackson. And Bill and I had worked together on an earlier record of mine called America: Do You Remember the Love? But we didn’t want the [Third Rail] project to be under any one person’s name, so Bill brainstormed and came up with a name for the group and an album title. Bill is great with words—coming up with names, titles, and stuff like that.”

In 2001, Laswell and Worrell returned to support Ulmer on his album Blue Blood, a superb blend of jazz and blues. And although there’s a guitarist and bassist on the record, neither Ulmer nor Laswell seems constrained by the other’s playing. If anything, they’re liberators, forging ahead with their distinct musical voices, expanding the aural dimensions of each song and providing additional creative space for one another to work. Ulmer’s leads and Laswell’s basslines are so intricate and sophisticated that there’s no way that they could be interwoven; instead, they’re overlaid, giving both instruments equal prominence in every song. [Listen to “Momentarily”]

“Music is something you do to bring people a message—to give them something to hold on to and help them remember. And that hurricane can never, never, never, ever be forgotten.” Also in 2001, Vernon Reid (Living Colour, Yohimbe Brothers), one of rock’s finest guitarists, began working with Ulmer on Memphis Blood, which would later receive a Grammy nomination for best traditional blues album. At first, Ulmer was reluctant to do the project. He had been raised on spiritual music, and with his father a minister, the risqué lyrics of many traditional blues classics had not been welcome in the household. In fact, Ulmer outright refused to record some of the songs that Reid, the producer, had suggested for the album.

“Vernon chose all the material,” Ulmer explains. “But I had to reject some of the songs. Now, ‘Back Door Man’—I didn’t want to sing that song because I ain’t no back-door man. I couldn’t tell nobody, ‘I’m a back-door man.’ I’m a front-door man. That one got on the album, though, but I’ve never performed it at a gig. You got to be careful about those songs. [Before Memphis Blood] I had never thought of doing a traditional blues record. So when Vernon made the suggestion, it was like a challenge to see if I could actually sing those songs. And it was almost like singing in church. When you’re singing in church, you’re not singing about nothing except God. So when you’re singing blues you can get a similar feeling—that you’re singing about something that’s not about you. Like ‘Spoonful’—that song is about coffee!” Ulmer exclaims, laughing. “Coffee and tea and diamonds and gold—and I don’t have none of it, so that song definitely wasn’t about me!” [Listen to “Spoonful”]

Since 2003, Reid has produced three more Ulmer albums that exhibit radically different takes on the blues idiom. No Escape From the Blues builds on the soulful, electric sound of ‘50s Chicago, while Birthright hails back to the solo-acoustic sessions of blues legend Robert Johnson’s recordings. Ulmer penned most of the material on Birthright, a collection of solemn, intensely personal songs.

“The song ‘Geechee Joe’ is about my grandfather,” he says. “I loved Geechee Joe and I had to write that song so my brothers and sisters could remember their granddad. And [Geechee Joe] did not want to work for the white man. He wasn’t working for no 50 cent’ a day. That was the message I was trying to get across. And he left everybody in South Carolina and went to Pittsburgh, where he became a freelance construction worker and numbers runner. He never took a job where he wasn’t the boss. It’s a true song.” [Listen to “Geechee Joe”]

In December 2006, Ulmer, Reid, and the Memphis Blood Blues Band headed down to New Orleans to record Bad Blood in the City,

an artistic reaction to the devastation wrought on the urban poor by

Hurricane Katrina. Ulmer’s passionate lyrics denounce the U.S.

government’s response to the disaster, and Reid exhibits some of his

best soloing since his heydays with Living Colour.

In December 2006, Ulmer, Reid, and the Memphis Blood Blues Band headed down to New Orleans to record Bad Blood in the City,

an artistic reaction to the devastation wrought on the urban poor by

Hurricane Katrina. Ulmer’s passionate lyrics denounce the U.S.

government’s response to the disaster, and Reid exhibits some of his

best soloing since his heydays with Living Colour.

“Most of the songs on the album are based on stories I got from watching CNN,” Ulmer says. “Music for me is something you do to bring people a message—to give them something to keep, to hold on to and help them remember. And that hurricane can never, never, never, ever be forgotten. Somebody said to me, ‘Blood, it’s been a year now. Don’t you think it’s a little too late to write about [Katrina]?’ Too late? I never thought about it that way. I’m shocked that people are waiting for the whole thing to pass over.” [Listen to “Survivors of the Hurricane”]

In May, Ulmer and the Memphis Blood Blues Band kicked off their tour to promote Bad Blood in the City with a phenomenal performance at the Rich Forum in Stamford, Conn. Reid, whose astonishing guitar work is featured on the new album, remained low-key during the show and all but silenced himself four songs into the set after a fan shouted, “More Blood Ulmer in the mix!”

For nearly two hours Ulmer dexterously wove earthy, expressive leads through the other musicians’ robust rhythmic and harmonic textures, accentuating the inimitable tension and resolution that defines his solos. When someone shouted “Blood Ulmer for President!” the band answered with a rollicking rendition of Willie Dixon’s “Dead Presidents,” a song that, along with three other Dixon covers, showcased Ulmer’s searing vocals. Throughout the performance, Reid diligently provided steady rhythmic support on every number and backing vocals on Dixon’s “I Love the Life I Live (I Live the Life I Love).” That night, Rich Forum epitomized what live music is all about—a mutual elation and joy shared by both the artists and the spectators.

Ulmer roars with laughter when he recalls the days when audiences weren’t so enthusiastic. “When I was with Coleman, people would get up and leave while we were playing because they hadn’t heard anything like it before,” he says. “And when we didn’t want to get bogged down with people moving around during the performance, we’d just tell them flat out, ‘Anybody who doesn’t want to hear this shit, just get up and leave now so we can have some fun!’“

“Many musicians have lost touch with what art is,” he adds. “It has become watered down so badly. Music has to represent something, but it has become too integrated. Martin Luther King integrated people. But now, you’ve got integrated music—people combining some shit to the point where it don’t mean nothing to nobody,” he says, laughing. “As a musician, you have a job to do. You’re a representative of someone’s culture and your music has to represent something, too.”

http://www.sevendaysvt.com/LiveCulture/archives/2013/11/05/an-interview-with-bluesman-james-blood-ulmer

2013

Burlington / Music An Interview With Bluesman James Blood Ulmer

by Ethan de Seife

November 5, 2013

Seven Days

James Blood Ulmer's music is equal parts blues, free jazz, funk and a lot of other things. He's a ferocious guitarist whose playing is tinted with shades of JimiHendrix, Sonny Sharrock, Gary Lucas and Son House, but his work is very strongly his own.

Ulmer has collaborated with Ornette Coleman, Vernon Reid, Bill Laswell, Art Blakey, Rashied Ali and countless others in his long and varied career. There's no other guitarist quite like him.

Ulmer recently spoke with Seven Days by phone from his home in NewYork City, in advance of his concert at the Flynn. The conversation began with a consideration of the best route to take when driving from New York Cityto Burlington.

Seven Days: There are so many different traditions winding through your music: blues, jazz, funk,soul, gospel. How do you define yourself, musically speaking? Does it even matter?

James Blood Ulmer: What I’m trying to be, what I’ll hopefully be, is … a change in music. I came up with a guitar style that was a totally different change, that sounds different from theregular sound of the guitar. … I’m always trying to make a difference, tryingto upgrade. Well, not upgrade, but change. I’m a guy who always wanted to take my guitar at high noon and play it at a Baptist church on Sunday … I’d like to play my guitar for the Baptist folks and have them not throw me out the door.

What is it about the blues that keeps bringing you back to it? Why is it so powerful and enduring?

Blues, I think, is very basic — the mother of jazz. That is the mother music.

My daddy didn’t allow us to listen to blues or hillbillymusic in the house. My daddy was a Christian man, and he was strict. I wasn’t allowed to play no blues as a child. I had to sneak out to hear the two guys in my town who played guitar. One was a blues player who used to drink White Lightning. Lived right in front of the church. The other man played gospel, but he drank alcohol, too! I had to sneak around and listento them.

I started in music backwards. I started in the gospel. At14, I stopped. I didn’t play no music until I graduated from high school andwent to Pittsburgh … At the end of the summer, when it was getting ready toget cold again, my cousin said, “Y’all got to get a job.”

I said, “Well, howmuch is the rent?” He said, “Six dollars a week.”

“Oh, wow, six dollars a week,”I said. “If I can get the six dollars a week without getting a job, would thatbe OK?”

“As long as you don’t steal it,” he said. Something had to happen, andthen I remembered: I knew how to play guitar.

Old bluesmen never played long solos on the guitar. It never

was about that. You never thought of Muddy Waters as a great guitar player. He was a bluesman. A bluesman has a story, and a way he tells the story. … Music and song begin to sound like scriptures. Not the Bible or anything, but a scripture in that it gives you the same feeling. It’s not about how good the guy is who’s playing the music. That’s what I try to keep away from.

You studied with Ornette Coleman and

have adapted his system of “harmolodics” to your own music. How do you

describe and discuss harmolodics?

I don’t look at

Coleman as a jazz player. Harmolodics is an unwritten music theory … But

harmolodics has what you call laws. You follow these laws and then you’re

harmolodics all the way.

Coleman has these laws he follows. He don’t play no chords, don’t follow no changes, like in jazz. Don’t have linear time signatures … The rhythm is superimposed, not linear. There are changes, there are modulations.These laws are used in harmolodics, and that’s what Coleman used. He doesn’t have to write it down.

I found out those laws are very valuable no matter what you do in music. Once you start applying those laws to blues, you start playing perfect blues. Blues have no laws. There’s no time, no changes, no particular meter you’re in. You can do blues music in any meter. That’s why blues is first. The laws in harmolodics are the same laws they have in the blues.

The ultimate thing that harmolodic music does is become like a language … The music. That’s all that matters. You’re not really creating anything. Everything was here already. We’re just discoverers of what was here already.

Are there any musicians you’d really like to collaborate with?

Yeah, some new ones. But I don’t know who they are, though! …My problem is I got to play with people who know my music, and it ain’t gonna be like they play. A booking agent brought a whole band here once. He wanted to get me gigs playing with these people, but they couldn’t play my music. Great people, but the music I’m playing … I had to say to the drummer, “Could you lose the backbeat?” He just said, “What?”

They wanna play the way they play. Yeah, I’m really looking for somebody to play with … I would love to play with some new musicians. Brand new. The unprogrammed ones.

Coleman has these laws he follows. He don’t play no chords, don’t follow no changes, like in jazz. Don’t have linear time signatures … The rhythm is superimposed, not linear. There are changes, there are modulations.These laws are used in harmolodics, and that’s what Coleman used. He doesn’t have to write it down.

I found out those laws are very valuable no matter what you do in music. Once you start applying those laws to blues, you start playing perfect blues. Blues have no laws. There’s no time, no changes, no particular meter you’re in. You can do blues music in any meter. That’s why blues is first. The laws in harmolodics are the same laws they have in the blues.

The ultimate thing that harmolodic music does is become like a language … The music. That’s all that matters. You’re not really creating anything. Everything was here already. We’re just discoverers of what was here already.

Are there any musicians you’d really like to collaborate with?

Yeah, some new ones. But I don’t know who they are, though! …My problem is I got to play with people who know my music, and it ain’t gonna be like they play. A booking agent brought a whole band here once. He wanted to get me gigs playing with these people, but they couldn’t play my music. Great people, but the music I’m playing … I had to say to the drummer, “Could you lose the backbeat?” He just said, “What?”

They wanna play the way they play. Yeah, I’m really looking for somebody to play with … I would love to play with some new musicians. Brand new. The unprogrammed ones.

http://www.furious.com/perfect/bloodulmer.html

JAMES BLOOD ULMER

Interview by Jason Gross (April 1998)

Thought there's been hundreds and thousands of hotshots who vowed to take the guitar to the next level after Jimi Hendrix broke the doors open, James 'Blood' Ulmer is one of the very few people to actually do this. His legend would be secure just from his work with Ornette Coleman as harmolodic music (combining harmony and melody) began to take shape. Ulmer really came to his own and then some as he began his solo careeer at the end of the '70's, putting together this distinct new wave of free jazz with bottom-bumping funk and gut-bucket blues as he began to make his own revolution in music, culminating with 1983's Odyssey. For years now, he's faithfully explored the possibilties that he's opened up with his own records as well as the Music Revlation Ensemble and now the James Blood Ulmer Blues Experience and a return to his Odyssey band (with violinst Charles Burnham and drummer Warren Benbow). Any thoughts that this concept may not sound as fresh today were laid to rest pretty quickly with an Odyssey show at the Knitting Factory where Blood, Burnham and Benbow burned up the stage- recorded evidence of this can be found on the recent Odyssey Reunion CD.

PSF: What led you to work with the Odyssey band again?

Well, it was really Charlie Burnham's idea. I was working in Third Rail, Music Revelation Ensemble and the Blues Experience. It was Charlie who insisted that we should go after this sound again. We're playing what I would call diotonic harmoladic music, meaning that the guitar, violin and the drums are totally playing in unison with equal voice. The guitar I have tuned to a unison tuning, away from the regular tuning of the guitar. No one plays the guitar tuned with all strings tuned to one note. The concept is about that, being that we are trying to play a special music that shows the difference in the structure of the instrument of getting the sound and having a base for what we're doing. Meaning that the guitar has to take care of a certain area and the violin is basically on top, the guitar is in the middle and the drums are on the bottom, playing in unison at the same time, harmolodically. That's what we were trying to do and that's what we were working on before. To start back working on that in that manner and with those instruments and making a good effort of continuing what we call harmolodic music where the instruments are in key, playing all 12 notes at the same time.

PSF: What's interesting about the band is that you have no bass player but you don't notice that when you hear the music. It's like there's no hole left there, no gaps.

We have a middle, a bottom and a top. It's what it's supposed to do. Once you make that connection, that's what's supposed to happen.

PSF: Going way back, you were in gospel group with father when you were young. What kind of bearing do you think that had on your later music?

That's WAY far back! (laughs) That's when I was a kid. I don't have too much recollection about that. We had a spiritual group. He (my father) was the leader and manager of that. I was in that group. I was waiting to get out of that group! Everything you do has a bearing on your music until you take a while and decide what you want to do with your music. What are you going to do with it? Once you decide that, everything that you've experienced is going to become what you're playing, what's coming out of you.

PSF: After that, you were in a band called Focus Novii. You did some gigs with Funkadelic back then?

I was playing in the 20 Grand Club and the Parliaments were the house band upstairs and I was playing in the jazz band downstairs. At the time, I thought I was much more advance than Parliament-Funkadelic. I was playing jazz and they were playing blues. (laughs) I should have thought about it because it turned out the other way.

When you learned how to play jazz, money didn't set the trend with how advanced you were with what you were doing. You went to school and you started out with church music then you play the blues and then you play avant-garde and then you play classical, first and last, and then you play what you want to play after that. That's how the school went. You'd pass a certain grade and then you'd go. That don't mean anything about how much money you make.

PSF: A lot of musicians took the same route. You think this is a necessary learning experience?

I don't think people are still keeping that same system going. I was think it was used for a while but I don't know about it. I think it's more or less a finance (decision). Everybody who plays music isn't really supposed to play music. You really could do something else much better. You ever hear anybody play music like that?

PSF: A lot of times!

Right, you hear them play but you really think they could do something else much better. (laughs)

PSF: I've heard you say that you've tried to get rid of scales and chords in music. Is this something ongoing for you?

I want the scales and chords to exist because without them, there would be no way to distinguish what you're playing. You playing a scale, you know what you're playing. If you wasn't playing a scale, you would have to find out what you're playing. A scale is a way that something is set up to do. There's another side to that, which is harmolodic again. That's where it's very valuable to know harmolodic music where you don't have to depend on the chords and the scales. That's what it means. But you have to know about it first. You can't NOT know about it.

PSF: Since we're talking about harmolodics, could you talk about your work with Ornette and how you each may have influenced each others' music?

Well, when you're working with someone close, like the way me and Coleman was, the thought is never what you're doing for each other. The thought is what what you're doing for what you're trying to do. Coleman always worked on something specifically and tried to take it to the highest level there is. So when you get through doing that, you ain't got time to be thinking about influencing somebody. You're trying to finish that piece of work.

One time I was writing the music to this play and he was into just directing it. He wanted to know every beat on the whole score. He puts everything to music and it was just incredible because (it was like) going through a needle and thread without leaving the hole. Just knitting it. It was amazing! Working with a person like that is just so amazing so you really don't think about who's influencing who. You're just thinking 'let's find out a way to get this.' He's definitely made me aware of harmolodic by making me aware of certain things. The coolest thing he told me (was) that I was a natural harmolodic player. He was one of the persons who could make you feel like what you were doing was so important. That's another thing that I got from Coleman- it's like someone who makes you feel that what you do is good. That's what he done.

PSF: You started as an instrumentalist but soon added vocals to songs- what led to the change?

After the first record I made, Tales of Captain Black, I started putting one song or two songs on every record I made. I figured that I do that one day because before I started playing and got to New York with it, I used to always be involved in singing music. I wasn't necessarily the singer but I was playing in bands where there was a singer. I always admired that kind of singing so I didn't want to cute it really loose. I always wanted to have a little singing because that's where I came from before I met these powerful guys. I always put one or two on a record until I had enough songs to play a gig singing songs.

PSF: With those early bands that you had when you started, did anything going on in other types of music like new wave or punk have any bearing on your own music?

Tales of Captain Black was produced by Coleman. With Freelancing, I don't know no band that sounds like that. I had Shannon Jackson playing drums, Calvin Weston, Olu Dara, David Murray, Amin Ali. That band was, I hate to say this, the first black band that entered into the clubs in New York City and did punk/funk/new wave. James Blood Band was the first black band to be playing that music in those clubs like Hurrah and Danceteria. No white band was playing shit like we were playing. I didn't hear no motherfuckers playing shit like we were playing. They let us in and we played with (Captain) Beefheart and Public Image and played in all those big clubs in New York. The shit was happening- nobody was playing that shit. I haven't heard anybody playing that shit yet- that's why I got to go back and play with Odyssey! (laughs) I had to go back 15 years to that!

PSF: Are You Glad to Be In America came out on different labels (Rough Trade and Artists House) with different mixes. Are you satisfied with either of the released versions?

To me, it's all the same music. I can hear through all of it. I don't hear the mix, I hear the music. The mix is very personal, like you see a woman and somebody might like her shoes or her dresses but you still see the woman. (laughs) I don't hear the different versions. I don't hear that. I mixed both of those records so it sounds like the same shit to me. I know they must have something there because we were trying to definitely get a different mix. I heard Ry Cooder say 'that first mix was the baddest thing. Nothing'll ever touch that.' He's slick, man! There might be something there but I can't hear that yet. I know it's something different. When I'm going in to make a record, I'm always trying to figure out how to make a certain mix. Once it gets to a certain point, I'm just agreeing with everybody. I'll be waiting for the co-producer to jump in there! I'd be trying to get the music straight and getting everything to line up and make sure anyone isn't playing what they're not supposed to be playing and get that out of the way. Then I'm ready for someone else to step in.

PSF: There was four year gap between Odyssey and next solo studio album though you did collaborations with David Murray and George Adams. Was there any reason for that?