SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2016

VOLUME THREE NUMBER TWO

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

BOBBY HUTCHERSON

September 10-16

GEORGE E. LEWIS

September 17-23

JAMES BLOOD ULMER

September 24-30

RACHELLE FERRELL

October 1-7

ANDREW HILL

October 8-14

CARMEN McRAE

(October 15-21)

PRINCE

(October 22-28)

LIANNE LA HAVAS

(October 29-November 4)

ANDRA DAY

(November 5-November 11)

ARCHIE SHEPP

(November 12-18)

WORLD SAXOPHONE QUARTET

(November 19-25)

ART BLAKEY

(November 26-December 2)

https://www.sfjazz.org/onthecorner/bobby-hutcherson

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/bobby-hutcherson-mn0000081231/biography

September 10-16

GEORGE E. LEWIS

September 17-23

JAMES BLOOD ULMER

September 24-30

RACHELLE FERRELL

October 1-7

ANDREW HILL

October 8-14

CARMEN McRAE

(October 15-21)

PRINCE

(October 22-28)

LIANNE LA HAVAS

(October 29-November 4)

ANDRA DAY

(November 5-November 11)

ARCHIE SHEPP

(November 12-18)

WORLD SAXOPHONE QUARTET

(November 19-25)

ART BLAKEY

(November 26-December 2)

https://www.sfjazz.org/onthecorner/bobby-hutcherson

August 15, 2016

by Rusty Aceves

by Rusty Aceves

San Francisco Jazz

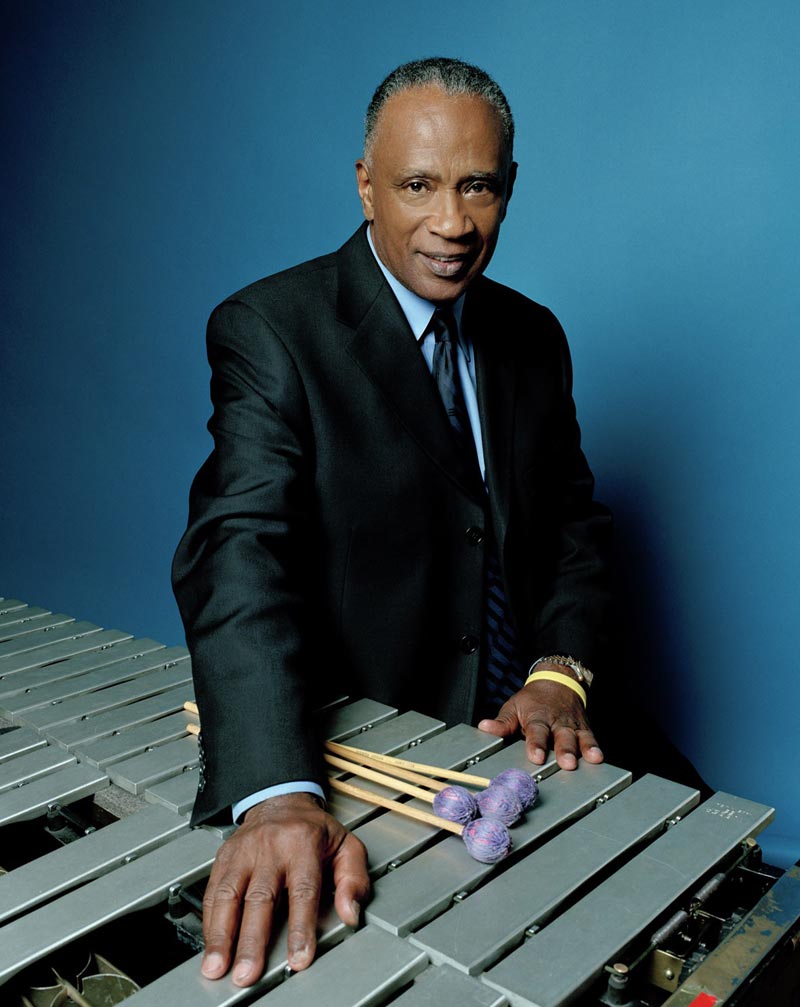

Bobby Hutcherson: January 27, 1941 - August 15, 2016

We are heartbroken to announce the loss of our dear friend, jazz legend Bobby Hutcherson, who passed peacefully on Monday, August 15 at age 75, surrounded by his family and loved ones.

The most accomplished vibraphonist and composer to emerge in the

latter half of the 20th Century, Bobby redefined the role of the

instrument in modern jazz, bringing new levels of technical mastery and

harmonic sophistication that had never been heard before. Inspired by

Modern Jazz Quartet vibraphonist Milt Jackson, he made his recording

debut with pianist Les McCann in 1961 and began an unprecedented 24-year

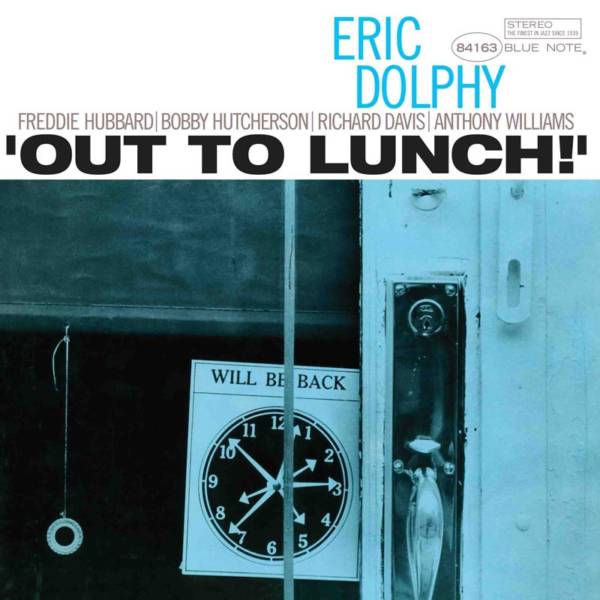

association with the Blue Note Records label on saxophonist Jackie McLean’s 1964 landmark One Step Beyond. From the crucial harmonic structures and pointillistic stabs of color on Eric Dolphy’s avant-garde masterpiece Out To Lunch and his soloistic fire on Joe Henderson’s epochal Mode For Joe to the soul jazz grease of Donald Byrd’s Ethiopian Knights,

Bobby made indelible contributions to over 250 albums during his Blue

Note tenure, and led 23 recordings that introduced the world to the

standards “Little B’s Poem,” “Bouquet,” “Components,” “Montara,” and

others.

Since moving to the Bay Area in the late 1960s, he developed fruitful

musical partnerships with both saxophonist Harold Land and pianist

McCoy Tyner, and released a string of sessions on the Blue Note,

Columbia, Landmark, and Kind of Blue labels. In 2010, the National

Endowment for the Arts named Bobby an NEA Jazz Master

for his lifetime of contributions to the art form – the highest honor

the U.S. bestows on jazz musicians. A great friend and artist with a

long history performing on SFJAZZ stages, beginning with a performance

at the very first Jazz in the City Festival in 1983, Bobby was a

founding member of the SFJAZZ Collective composing, arranging, and performing with the band from its inception in 2004 through 2007 (video). He was the honoree at the 2010 SFJAZZ Gala, spoke at the groundbreaking event for the SFJAZZ Center in 2012, and performed during the historic Opening Night concert in January, 2013.

Bobby will be greatly missed. We are honored to have known him. He's

survived by wife Rosemary, sons Teddy and Barry, and grandchildren Ruby

Rose and Bobby James.

A Memorial for Bobby Hutcherson to benefit Hutcherson family medical expenses will take place Sunday, October 23, 7:30pm at SFJAZZ Center. More information here.

Bobby Hutcherson (w/ McCoy Tyner Trio), SFJAZZ Spring Season 2009 (Photo by Mark Brady)

Updated Thursday, August 25, 2016 at 5pm.

Tags: Tribute

Bobby Hutcherson

(1941-2016)

Artist Biography by Steve Huey

Easily one of jazz's greatest vibraphonists, Bobby Hutcherson epitomized his instrument in relation to the era in which he came of age the way Lionel Hampton did with swing or Milt Jackson

with bop. He wasn't as well-known as those two forebears, perhaps

because he started out in less accessible territory when he emerged in

the '60s playing cerebral, challenging modern jazz that often bordered

on avant-garde. Along with Gary Burton, the other seminal vibraphone talent of the '60s, Hutcherson

helped modernize his instrument by redefining what could be done with

it -- sonically, technically, melodically, and emotionally. In the

process, he became one of the defining (if underappreciated) voices in

the so-called "new thing" portion of Blue Note's glorious '60s roster. Hutcherson gradually moved into a more mainstream, modal post-bop style that, if

not as adventurous as his early work, still maintained his reputation as

one of the most advanced masters of his instrument.

Bobby Hutcherson

was born January 27, 1941, in Los Angeles. He studied piano with his

aunt as a child, but didn't enjoy the formality of the training; still,

he tinkered with it on his own, especially since his family was already

connected to jazz: his brother was a high-school friend of Dexter Gordon and his sister was a singer who later dated Eric Dolphy. Everything clicked for Hutcherson during his teen years when he heard a Milt Jackson record; he worked until he saved up enough money to buy his own set of vibes. He began studying with Dave Pike and playing local dances in a group led by his friend, bassist Herbie Lewis. After high school, Hutcherson parlayed his growing local reputation into gigs with Curtis Amy and Charles Lloyd, and in 1960 he joined an ensemble co-led by Al Grey and Billy Mitchell. In 1961, the group was booked at New York's legendary Birdland club and Hutcherson wound up staying on the East Coast after word about his inventive four-mallet playing started to spread. Hutcherson was invited to jam with some of the best up-and-coming musicians in New York: hard boppers like Grant Green, Hank Mobley, and Herbie Hancock, but most importantly, forward-thinking experimentalists like Jackie McLean, Grachan Moncur III, Archie Shepp, Andrew Hill, and Eric Dolphy. Through those contacts, Hutcherson became an in-demand sideman at recording sessions, chiefly for Blue Note.

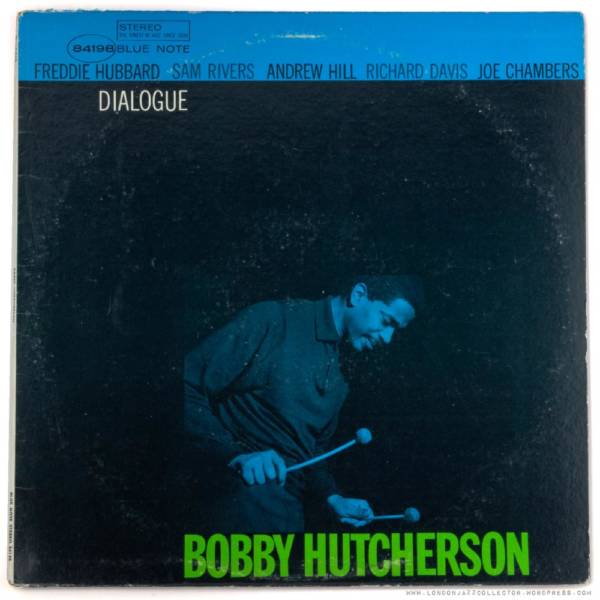

Hutcherson had a coming-out party of sorts on McLean's seminal "new thing" classic One Step Beyond (1963), providing an unorthodox harmonic foundation in the piano-less quintet. His subsequent work with Dolphy was even more groundbreaking and his free-ringing, open chords and harmonically advanced solos were an important part of Dolphy's 1964 masterwork, Out to Lunch. That year, he won the Down Beat readers' poll as Most Deserving of Wider Recognition on his instrument.

Hutcherson's first shot as a leader came with 1965's Dialogue, a classic of modernist post-bop with a sextet featuring some of the hottest young talent on the scene -- most notably Freddie Hubbard, Sam Rivers, and Andrew Hill, although drummer Joe Chambers would go on to become a fixture on Hutcherson's

'60s records (and often contributed some of the freest pieces he

recorded). A series of generally excellent sessions followed over the

next few years, highlighted by 1965's classic Components (which showcased both the free and straight-ahead sides of Hutcherson's playing) and 1966's Stick-Up! In 1967, he returned to Los Angeles and started a quintet co-led by tenor saxophonist Harold Land, which made its recording debut the following year on Total Eclipse. Several more sessions followed (Spiral, Medina, Now)

that positioned the quintet about halfway in between free bop and

mainstream hard bop -- advanced territory, but not entirely fashionable

at the time. Thus, the group didn't really receive its due and dissolved

in 1971.

By that point, Hutcherson was beginning a brief flirtation with mainstream fusion, which produced 1970's funky but still sophisticated San Francisco

(named after his new base of operations). By 1973, however, he'd

abandoned that direction, returning to modal bop and forming a new

quintet with trumpeter Woody Shaw that played at that summer's Montreux Jazz Festival (documented on Live at Montreux). In 1974, he re-teamed with Land,

and over the next few years he continued to record cerebral bop dates

for Blue Note despite being out of step with the label's more commercial

direction. He finally departed in 1977 and signed with Columbia, where

he recorded three albums from 1978-1979 (highlighted by Un Poco Loco). Adding the marimba to his repertoire, Hutcherson

remained active throughout the '80s as both a sideman and leader,

recording most often for Landmark in a modern-mainstream bop mode. He

spent much of the '90s touring rather than leading sessions; in 1993, he

teamed with McCoy Tyner for the duet album Manhattan Moods. Toward the end of the decade, Hutcherson signed on with Verve, for whom he debuted in 1999 with the well-received Skyline.

In 2004, Hutcherson joined the SFJAZZ Collective, touring with the ensemble for several years. In 2007, he released the album For Sentimental Reasons, which featured pianist Renee Rosnes. Two years later, Hutcherson returned with the John Coltrane-inspired Wise One. The concert album Somewhere in the Night, recorded at Dizzy's Club Coca-Cola at Lincoln Center, appeared in 2012. In 2014, Hutcherson joined organist Joey DeFrancesco and saxophonist David Sanborn for the Blue Note session Enjoy the View. Suffering from emphysema, Hutcherson died at his home in Montara, California in August 2016 at the age of 75.

Music

Bobby Hutcherson, Vibraphonist With Coloristic Range of Sound, Dies at 75

Bobby

Hutcherson, one of the most admired and accomplished vibraphonists in

jazz, died on Monday at his home in Montara, Calif. He was 75.

Marshall

Lamm, a spokesman for Mr. Hutcherson’s family, confirmed the death,

saying Mr. Hutcherson had long been treated for emphysema.

Mr. Hutcherson’s career took flight in the early 1960s, as jazz was slipping free of the complex harmonic and rhythmic designs of bebop. He was fluent in that language, but he was also one of the first to adapt his instrument to a freer postbop language, often playing chords with a pair of mallets in each hand.

He released more than 40 albums and appeared on many more, including some regarded as classics, like “Out to Lunch,” by the alto saxophonist, flutist and bass clarinetist Eric Dolphy, and “Mode for Joe,” by the tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson.

Both of those albums were a byproduct of Mr. Hutcherson’s close affiliation with Blue Note Records, from 1963 to 1977. He was part of a wave of young artists who defined the label’s forays into experimentalism, including the pianist Andrew Hill and the alto saxophonist Jackie McLean. But he also worked with hard-bop stalwarts like the tenor saxophonist Dexter Gordon, and he later delved into jazz-funk and Afro-Latin grooves.

Mr. Hutcherson had a clear, ringing sound, but his style was luminescent and coolly fluid. More than Milt Jackson or Lionel Hampton, his major predecessors on the vibraphone, he made an art out of resonating overtones and chiming decay.

This

coloristic range of sound, which he often used in the service of

emotional expression, was one reason for the deep influence he left on

stylistic inheritors like Joe Locke, Warren Wolf, Chris Dingman and

Stefon Harris, who recently assessed him as “by far the most

harmonically advanced person to ever play the vibraphone.”

Robert

Hutcherson was born in Los Angeles on Jan. 17, 1941. His father, Eli,

was a brick mason, and his mother, Esther, was a hairdresser.

Growing up in a black community in Pasadena, Calif., Mr. Hutcherson was drawn to jazz partly by way of his older siblings: His brother, Teddy, had gone to high school with Mr. Gordon, and his sister, Peggy, was a singer who worked with the Gerald Wilson Orchestra. (She later toured and recorded with Ray Charles as a Raelette.)

Mr. Hutcherson, who took piano lessons as a child, often described his transition to vibraphone as the result of an epiphany: Walking past a record store one day, he heard a recording of Milt Jackson and was hooked. A friend at school, the bassist Herbie Lewis, further encouraged his interest in the vibraphone, so Mr. Hutcherson saved up and bought one. He was promptly booked for a concert with Mr. Lewis’s band.

“Well, I hit the first note,” he recalled of that performance in a 2014 interview with JazzTimes. But, he added, “from the second note on it was complete chaos. You never heard people boo and laugh like that. I was completely humiliated. But my mom was just smiling, and my father was saying, ‘See, I told you he should have been a bricklayer.’”

Mr. Hutcherson persevered, eventually working with musicians like Mr. Dolphy, whom he had first met when Mr. Dolphy was his sister’s boyfriend, and the tenor saxophonist and flutist Charles Lloyd. In 1962, he joined a band led by a pair of Count Basie sidemen, the tenor saxophonist Billy Mitchell and the trombonist Al Grey, and it brought him to New York City for a debut engagement at Birdland

The

group broke up not long afterward, but Mr. Hutcherson stayed in New

York, driving a taxicab for a living, his vibraphone stashed in the

trunk. He was living in the Bronx and married to his high school

sweetheart, the former Beth Buford, with whom he had a son, Barry — the

inspiration for his best-known tune, the lilting modernist waltz “Little B’s Poem.”

Mr. Hutcherson caught a break when Mr. Lewis, his childhood friend, came to town and introduced him to the trombonist Grachan Moncur III, who in turn introduced him to Mr. McLean. “One Step Beyond,” an album by Mr. McLean released on Blue Note in 1963, featured Mr. Hutcherson’s vibraphone as the only chordal instrument. From that point on, he was busy.

The first album he released as a leader was “Dialogue” (1965), featuring Mr. Hill, the trumpeter Freddie Hubbard and the saxophonist and flutist Sam Rivers. Among his notable subsequent albums was “Stick-Up!” (1966), with Mr. Henderson and the pianist McCoy Tyner among his partners. He and Mr. Tyner would forge a close alliance.

After

being arrested for marijuana possession in Central Park in 1967, Mr.

Hutcherson lost his cabaret card, required of any musician working in

New York clubs. He returned to California and struck a rapport with the

tenor saxophonist Harold Land. Among the recordings they made together

was “Ummh,” a funk shuffle that became a crossover hit in 1970. (It was later sampled by the rapper Ice Cube.)

In the early ’70s Mr. Hutcherson bought an acre of land along the coast in Montara, where he built a house. He lived there with his wife, the former Rosemary Zuniga, whom he married in 1972. She survives him, along with their son, Teddy, a marketing production manager for the organization SFJazz; his son Barry, a jazz drummer; and two grandchildren.

After his tenure on Blue Note, Mr. Hutcherson released albums on Columbia, Landmark and other labels, working with Mr. Tyner, the tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins and — onscreen, in the 1986 Bertrand Tavernier film “Round Midnight” — with Mr. Gordon and the pianist Herbie Hancock. From 2004 to 2007, Mr. Hutcherson toured with the first edition of the SFJazz Collective, an ensemble devoted equally to jazz repertory and the creation of new music. He was named a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master in 2010.

After releasing a series of albums on the European label Kind of Blue, he returned to Blue Note in 2014 to release a soul-jazz effort, “Enjoy the View,” with the alto saxophonist David Sanborn and other collaborators.

Speaking

in recent years, Mr. Hutcherson was fond of citing a bit of insight

from an old friend. “Eric Dolphy said music is like the wind,” he told

The San Francisco Chronicle in 2012. “You don’t know where it came from,

and you don’t know where it went. You can’t control it. All you can do

is get inside the sphere of it and be swept away.”

Easily one of jazz’s greatest vibraphonists, Hutcherson helped

modernize his instrument by redefining what could be done with it sonically, technically, melodically, and emotionally. In the process, he

became one of the defining voices in the so-called “new thing” portion

of Blue Note’s glorious ’60s roster. Hutcherson gradually moved into a

more mainstream, modal post-bop style that, if not as adventurous as his

early work, still maintained his reputation as one of the most advanced

masters of his instrument.

Attracted foremost to more experimental free jazz and post-bop, Hutcherson, inspired by the style began recording on the Blue Note label with Jackie McLean, Eric Dolphy, Andrew Hill, Grachan Moncur III, Joe Chambers, and Freddie Hubbard, both as a leader and a sideman. In spite of the numerous avant-garde recordings made during this period however, Hutcherson’s first session for Blue Note, The Kicker (1963) (not released until 1999), demonstrates his background in hard bop and the blues, as well as the early session Idle Moments for Grant Green.

In addition to his own recordings and tours, Hutcherson also appears on other artists’ records, including Tyner’s Manhattan Moods (1993) and Hammond B-3 organist Joey DeFrancesco’s Organic Vibes (2006). Hutcherson continues to perform at a masterful level on his instrument, playing with both his contemporaries and the new generation of jazz musicians.

Hutcherson’s work remains entirely compelling. He brings something special every time he plays. In recent years, it’s especially noticeable on his recordings as a sideman. If he doesn’t play on a particular track, you miss him. When he does play, everyone sounds better.

Bobby had (and still has) a work ethic, a brilliant mind, a profound,

non-ritualistic spirituality, an innate wisdom and warmth that made for

the ingredients of an outstanding jazz artist as well as a hell of a

human being.

“Bobby Hutcherson can move easily across a vocabulary of such breadth that it would neutralize the identity of a less talented player.” —Stanley Crouch

https://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog/2016/aug/17/bobby-hutcherson-five-great-performances-jazz-vibraphone

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bobby_Hutcherson

Bobby Hutcherson

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Bobby Hutcherson | |

|---|---|

At JazzBaltica Festival with Joe Locke. 2007.

|

|

| Background information | |

| Born | January 27, 1941 Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Died | August 15, 2016 (aged 75) Montara, California, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instruments | |

| Years active | 1961–2016 |

| Associated acts | See discography |

Robert "Bobby" Hutcherson (January 27, 1941 – August 15, 2016) was an American jazz vibraphone and marimba player. "Little B's Poem", from the album Components, is one of his best-known compositions.[1][2][3][4] Hutcherson influenced younger vibraphonists including Steve Nelson, Joe Locke, and Stefon Harris.[3][5][6][7]

Contents

Biography

Early life and career

Bobby

Hutcherson was born to Eli, a master mason, and Esther, a hairdresser.

Hutcherson was exposed to jazz by his brother Teddy, who listened to Art Blakey records in the family home with his friend Dexter Gordon. His older sister Peggy was a singer in Gerald Wilson's

orchestra. Hutcherson went on to record on a number of Gerald Wilson's

Pacific Jazz recordings as well as play in his orchestra. Hutcherson's

sister personally introduced Hutcherson to Eric Dolphy (her boyfriend at the time) and Billy Mitchell. Hutcherson was inspired to take up the vibraphone when he heard Milt Jackson play "Bemsha Swing" on the Miles Davis and the Modern Jazz Giants

album at the age of 12. Still in his teens, Hutcherson began his

professional career in the late fifties working with tenor saxophonist Curtis Amy and trumpeter Carmell Jones, as well as with Dolphy and tenor saxophonist Charles Lloyd at Pandora's Box on the Sunset Strip.[3][8][9]

He made his recording debut on August 3, 1960, cutting two songs for a 7-inch single with the Les McCann trio for Pacific Jazz (released in 1961), followed by the LP Groovin' Blue with the Curtis Amy-Frank Butler sextet on December 10 (also released by Pacific Jazz in 1961). In January 1962, Hutcherson joined the Billy Mitchell–Al Grey group for dates at The Jazz Workshop in San Francisco and Birdland

in New York City (opposite Art Blakey). After touring with the

Mitchell–Grey group for a year, Hutcherson settled in New York City (on

165th street in The Bronx) where he worked part-time as a taxi driver, before fully entering the jazz scene via his childhood friend, bassist Herbie Lewis.[8][9][10]

Blue Note Records

Lewis was working with The Jazztet and hosted jam sessions at his apartment. After hearing Hutcherson play at one of Lewis' events, Jazztet and Jackie McLean band member Grachan Moncur III felt that Hutcherson would be a good fit for McLean's group, which led to Hutcherson's first recording for Blue Note Records on April 30, 1963, McLean's One Step Beyond.[8] This was quickly followed by sessions for Blue Note with Moncur, Dolphy, Gordon, Andrew Hill, Tony Williams and Grant Green in 1963 and 1964, later followed by sessions with Joe Henderson, John Patton, Duke Pearson and Lee Morgan.[9] In spite of the numerous post-bop, avant-garde, and free jazz recordings made during this period, Hutcherson's first session for Blue Note as leader, The Kicker (recorded in 1963 but not released until 1999), demonstrated his background in hard bop and the blues, as did Idle Moments with Grant Green.

Hutcherson won the "Talent Deserving of Wider Recognition" award in the 1964 Down Beat readers' poll, and Blue Note released Hutcherson's Dialogue in 1965.[11] The 1966 record Stick-Up!, featuring Joe Henderson, Herbie Lewis, and Billy Higgins, was the first of many recorded sessions Hutcherson made with McCoy Tyner throughout their careers. Stick-Up!

was also the only album out of ten Hutcherson recorded as leader for

Blue Note between 1965 and 1969 which did not feature drummer Joe Chambers or any of Chambers' compositions.[2][9] Spanning the years 1963 to 1977, Hutcherson had one of the longest recording careers with Blue Note, second only to Horace Silver's.[1]

Return to the West Coast

Hutcherson lost his cabaret card and taxi driver's license in 1967 after he and Joe Chambers were arrested for marijuana possession in Central Park,[12] so he moved back to California, but continued to record for Blue Note.[8] This return to the West Coast resulted in an important partnership with Harold Land, with whom Hutcherson recorded seven albums for Blue Note, featuring a rotating lineup of pianists such as Chick Corea, Stanley Cowell, and Joe Sample,

and usually Chambers on drums. The Hutcherson-Land group broke up in

1971, and that same year Hutcherson won the title of "World's Best

Vibist" in the International Jazz Critics Poll.[2][11] After the release of Knucklebean in 1977, Hutcherson recorded three albums for Columbia Records in the late 1970s.

Hutcherson performing at the Berkeley Jazz Festival in 1982. Photo: Brian McMillen

Land and Hutcherson reunited in the early 1980s for several recordings as the "Timeless All Stars," a sextet featuring Curtis Fuller, Cedar Walton, Buster Williams, and Billy Higgins which recorded four albums for the Dutch label Timeless Records.[1] After switching between several labels in the early 1980s for his solo material, Hutcherson recorded eight albums for Landmark Records

from the 1980s into the early 1990s, and continued to work steadily as a

sideman during this time. His recorded output slowed somewhat during

the past few decades, although he did release albums for Atlantic and Verve in the 1990s, three for the Swiss-based label Kind of Blue in the 21st century, and continued to tour.

Later years

In 2004, Hutcherson became an inaugural member of the SFJAZZ Collective, featuring Joshua Redman, Miguel Zenón, Nicholas Payton, Renee Rosnes, and Eric Harland, among others. He toured with them for four years, and made an appearance at the SFJAZZ Center's grand opening in 2013.[8] His 2007 quartet included Renee Rosnes on piano, Dwayne Burno on bass and Al Foster on drums. His 2008 quartet included Joe Gilman on piano, Glenn Richman on bass and Eddie Marshall on drums. In 2010 he received the lifetime Jazz Master Fellowship Award from the National Endowment for the Arts and performed at Birdland in a quintet featuring Gilman, Burno, Marshall, and Peter Bernstein. 2014 saw Hutcherson return to Blue Note Records with Enjoy the View, recorded at Ocean Way Studios in Hollywood with Joey DeFrancesco, David Sanborn, and Billy Hart. The quartet performed four sold-out shows at the SFJAZZ Center in February, prior to the album's release.[13][14]

Acting career

Hutcherson's intermittent acting career included an appearance as the bandleader in They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969), and as Ace in Round Midnight (1986).[15]

Personal life

Hutcherson

has a son, Barry, from his first marriage to Beth Buford. Hutcherson

wrote the waltz "Little B's Poem" for Barry in 1962.[3] Due to the success of "Ummh" from the album San Francisco, one of Hutcherson's few entries in the jazz fusion style, he was able to buy an acre of land on which he built a house in Montara, California, in 1972.[2][8] That same year, he married Rosemary Zuniga, a ticket taker at the Both/And club in San Francisco.[7] The couple had a son, Teddy, who is a production manager for SFJAZZ. Hutcherson attended an African Methodist Episcopal Church as a youth and converted to Catholicism later in life.[3]

Suffering from emphysema since 2007,[16] Hutcherson died from the condition in Montara, California, on August 15, 2016.[17][18][19]

Style and critical reception

Bobby's thorough mastery of harmony and chords combined with his virtuosity and exploratory intuition enabled him to fulfill the function that is traditionally allocated to the piano and also remain a voice in the front line. He did this to perfection in the bands of Dolphy, McLean, and Archie Shepp. His approach to the vibes was all encompassing; it was pianistic in the sense of melody and harmony and percussive in rhythmic attack and placement. He brought a fire and a passion back into the instrument that had been lost since the prime of Lionel Hampton. He was firmly rooted in the be bop tradition, but constantly experimenting and expanding upon that tradition.

I love playing with Bobby. He's an exceptionally gifted jazz improviser... It's always a lot of fun to play with him, always enlightening, emotional as well as intellectually challenging. Bobby is a very honest person. He couldn't play the way he does without that honesty. He has an innocence that's childlike in a way. He's a great player and a great person, and that helps boost humanity a little bit.

AllMusic

contributor Steve Huey stated that Hutcherson's "free-ringing, open

chords and harmonically advanced solos were an important part of

Dolphy's 1964 masterwork Out to Lunch!", and called Dialogue

a "classic of modernist post-bop", declaring Hutcherson "one of jazz's

greatest vibraphonists". Huey went on to say: "along with Gary Burton,

the other seminal vibraphone talent of the '60s, Hutcherson helped

modernize his instrument by redefining what could be done with it –

sonically, technically, melodically, and emotionally. In the process, he

became one of the defining (if underappreciated) voices in the

so-called "new thing" portion of Blue Note's glorious '60s roster."[2]

In his liner notes to the 1980 release of Medina, record producer Richard Seidel (Verve, Sony Masterworks)

wrote that "of all the vibists to appear on the scene contemporaneous

with Hutcherson, none have been able to combine the rhythmic dexterity,

emotive attack and versatile musical interests that Bobby possesses."

Seidel concurred that Hutcherson was "part of the vanguard of the new

jazz developments in the Sixties. He contributed mightily to several of

the key sessions that document these developments."[20]

Interviewed by Jesse Hamlin for a piece on Hutcherson in the San Francisco Chronicle in 2012, collaborator Joshua Redman

said that "We talk a lot about how music expresses universal values,

experiences and feelings. But you don't often witness that so clearly

and so profoundly as you do with Bobby. His music expresses the joy of

living. He connects to the source of what music is about."[3]

In an April 2013 profile for Down Beat

magazine, Dan Ouellette wrote that "Hutcherson took the vibes to a new

level of jazz sophistication with his harmonic inventions and his

blurring-fast, four-mallet runs... Today, he's the standard bearer of

the instrument and has a plenitude of emulators to prove it." Ouellette

quoted Joey DeFrancesco as saying "Bobby is the greatest vibes player of all time... Milt Jackson was the guy, but Bobby took it to the next level. It's like Milt was Charlie Parker, and Bobby was John Coltrane."[8]

Discography

Main article: Bobby Hutcherson discography

References

- Seidel, Richard. Liner notes. Hutcherson, Bobby. Medina. Blue Note, 1980. LP.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bobby Hutcherson. |