SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2015

VOLUME TWO NUMBER ONE

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2015

VOLUME TWO NUMBER ONE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

LAURA MVULA

October 10-16

DIZZY GILLESPIE

October 17-23

LESTER YOUNG

October 24-30

TIA FULLER

October 31-November 6

ROSCOE MITCHELL

November 7-13

MAX ROACH

November 14-20

DINAH WASHINGTON

November 21-27

BUDDY GUY

November 28-December 4

JOE HENDERSON

December 5-11

HENRY THREADGILL

December 12-18

MUDDY WATERS

December 19-25

B.B. KING

December 26-January 1

IN CELEBRATION OF LESTER 'PREZ' YOUNG ON THE 105th ANNIVERSARY OF HIS BIRTH!--AUGUST 27. 2014

FROM THE PANOPTICON REVIEW ARCHIVES

(Originally posted on August 27. 2013):

http://panopticonreview.blogspot.com/2013/08/the-magnificent-legacy-of-lester-prez.html

Tuesday, August 27, 2013

The Magnificent Legacy of Lester 'Prez' Young (1909-1959) On the 104th anniversary of his Birth

LESTER YOUNG

(b. August 27, 1909)

LESTER YOUNG IN 1958

(1909-1959)

by Kofi Natambu

Tears are iodine

seeping thru tenor

perforations

A cloud of song

floats past an open ear

blowing kisses along the

frontiers of memory

A beat that shines

blinds us

a writhing melodic curve dives &

swoops

In that capacious bell

lonely dreams hide

Our bodies become the dance his

voice provides

LESTER YOUNG IN 1956

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=112255870

Lester Young: ‘The Prez’ Still Rules At 100

August 27, 2009

by Tom Vitale

National Public Radio (NPR)

AUDIO: <iframe src="http://www.npr.org/player/embed/112255870/112281219" width="100%" height="290" frameborder="0" scrolling="no" title="NPR embedded audio player"></iframe>

In the 1930s, Lester Young — known as the "President of Jazz" or simply "The Prez" — led a revolution on the tenor saxophone that influenced generations to follow. He was Billie Holiday's favorite accompanist, and his robust tenor playing influenced everybody from Charlie Parker to Sonny Rollins. Young was famous for his porkpie hat and his hipster language, but he'll always be remembered for his remarkable solos. Lester Young was born 100 years ago Thursday.

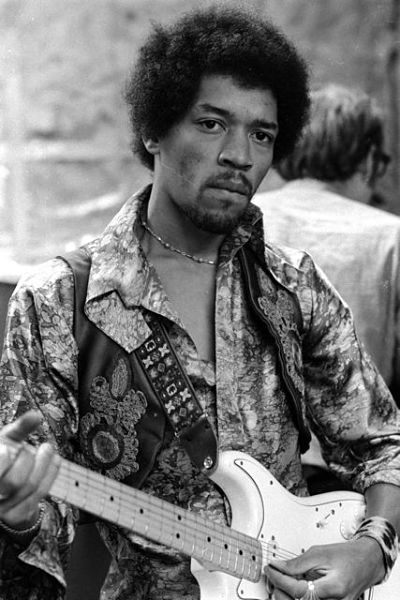

Rather than holding his saxophone vertically, Lester Young held it high and to the right at a 45-degree angle.

Herman Leonard/Getty Images

In it, Young said that even though he became famous with the Count Basie Orchestra, he didn't like big bands.

"I don't like a whole lot of noise — trumpets and trombones," Young says in the recording. "I'm looking for something soft. It's got to be sweetness, man, you dig?"

Young's Signature Style

Sweetness is what Young was all about. When he started to gain attention, the dominant style of the day was the aggressive, hard-driving saxophone of Coleman Hawkins. But Young played in the upper range of his tenor in a lyrical, relaxed style.

"He had marvelous sensitivity and taste," says Dan Morgenstern, who wrote the book Living in Jazz. "Never played a tasteless note in his life."

Morgenstern, who met Young in 1958, says the saxophonist always told a story in his solos, in an original way.

"He had this 'floating' style, where he would kind of float above the rhythm. He was like an acrobat," Morgenstern says. "And, you know, at the same time, his melodic imagination was so marvelous. The combination of rhythm and melody — nobody else quite ever had that."

Young was an original in other ways. Rather than holding his saxophone vertically, he held it high and to the right at a 45-degree angle. He famously wore a porkpie hat and moccasins. Young also had a flair for language: He said he had "big eyes" for the things he liked, he nicknamed Billie Holiday "Lady Day," and he called women's feet in open-toed shoes "nice biscuits." He also made up new words that found their way into songs.

Young's cachet among hipsters led to his popularizing now-common words. Everyone started using the word "cool" after they heard him say it, according to jazz historian Phil Schaap.

"But the one that really makes the most sense," Schaap says, "you call up Lester Young for a gig, he'd say, 'Okay, how does the bread smell?' So he used 'bread' for money for the first time."

Serving In The Army

Lester Willis Young was born in Woodville, Miss., on Aug. 27, 1909. His father Willis played several instruments and taught all of his children to play. When he was 18, Lester left the family vaudeville band and moved west, ending up in Kansas City with Count Basie.

By the time World War II started, Young was a jazz star. So he expected his military service to be spent entertaining the troops, like the white musicians in the bands of Glenn Miller and Artie Shaw. But the government drafted Young into the "regular Army."

"He was just another soldier, and he was going to do what they told him to do, and he refused," drummer Jerry Potter said.

Potter was stationed at Fort McClellan, Ala., in the fall of 1944 when Young arrived for basic training. Thirty-five years later, Potter recalled that Young didn't want to cut his hair, didn't want to sleep in a barracks and refused to wear Army boots.

"He didn't need basic training, because he was never going to fire a gun," Potter says. "You see, that's another thing. He never wanted to fire a rifle. 'I don't want to kill anyone. I want to play and make them happy.' "

Young was court-martialed for using marijuana. His Army experience was traumatic, and it inspired his composition "D.B. Blues," for "detention barracks."

Late Career Struggles

Young drank heavily for the rest of his life. Nevertheless, he continued to tour and record a lot. Some critics say his playing was never as strong after the war, but others argue that his ballads possessed more emotional power.

Throughout his life, Young struggled with racism, from the Jim Crow laws his family faced in the 1920s to the way he felt the Army treated him during WW2 in the 1940s.

"They want everyone who's a Negro to be an Uncle Tom, an Uncle Remus and Uncle Sam, and I can't make it," Young said. "But it's the same way all over. You just fight for your life, you dig? Until death do you part. Then you got it made."

American jazz saxophone player and songwriter Young revolutionized modern jazz tenor-saxophone playing, and his light, lyrical sound was featured in orchestras such as Count Basie's, in his partnering of such singers as Billie Holiday, and in his combo work with both traditional and modern jazz musicians.

Born: August 27, 1909; Woodville, Mississippi

Died: March 15, 1959; New York, New York

Also known as: Lester Willis Young (full name) and PREZ (a legendary nickname that Billie Holiday gave him meaning "President of the saxophone players")

The Pres Principal recording albums: Kansas City Style, 1944; Lester Warms Up, 1944; Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young, 1946 (with Coleman Hawkins); Lester Young: Buddy Rich Trio, 1946 (with Buddy Rich); Lester Young: Nat King Cole Trio, 1946 (with Nat King Cole); Lester Young Quartet and Count Basie Seven, 1950 (with Count Basie); Lester Young Swings Again, 1950; The Pres, 1950; Pres Is Blue, 1950;

Lester Young Collates, 1951; Lester Young Trio, 1951 (with Lester Young Trio); Pres, 1951; It Don't Mean a Thing, 1952; Pres and His Cabinet, 1952 (with others); Pres and Teddy and Oscar, 1952 (with Oscar Peterson and Teddy Wilson); Lester Young with the Oscar Peterson Trio, 1952 (with Peterson); Battle of the Saxes, 1953 (with others); Just You, Just Me, 1953; Lester Young Collates No. 2, 1953;

Lester Young: His Tenor Sax, 1954; Lester Young with the Oscar Peterson Trio, Vol. 1, 1954 (with Peterson); Lester Young with the Oscar Peterson Trio, Vol. 2, 1954 (with Peterson); Mean to Me, 1954; The President, 1954; Pres and Sweets,

1955 (with Harry Sweets Edison); Pres Meets Vice Pres, 1955 (with Paul Quinichette); The Jazz Giants '56, 1956 (with Roy Eldridge); Lester Swings Again,

1956; Lester's Here, 1956; Nat King Cole: Buddy Rich Trio, 1956 (with Cole and Buddy Rich); Pres and Teddy, 1956 (with Wilson); Tops on Tenor, 1956; Going for Myself, 1957;

If It Ain't Got That Swing, 1957; Laughin' to Keep from Cryin', 1958; The Lester Young/Teddy Wilson Quartet, 1959 (with Wilson). The Life

The oldest of three children, Lester Willis Young grew up near New Orleans, where his father, a minstrel-show musician, instructed him on playing the trumpet, saxophone, and drums. Young toured several midwestern states with the family band, and, at age thirteen, he decided to concentrate on mastering the saxophone. Later, he often said that his distinctive sound was the result of his attempt to imitate on his tenor saxophone the C-melody saxophone timbre of his idol Frankie Trumbauer. During the late 1920's and early 1930's, Young played for various bands in Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Minnesota, including the orchestras of King Oliver, Andy Kirk, and Walter Page. His most extensive and important association was with Count Basie's big band and small groups, which led to his first recordings. After leaving Basie in 1940, Young played in several combos led by himself and by other musicians. In 1944, when he won first place in the Down Beat poll for the best tenor saxophonist, he was drafted into the Army, which proved disastrous for his personal and professional life. He was court-martialed for using marijuana, and he spent several months in a Georgia military prison. When he was released at the end of 1945, he resumed playing, recording, and touring. However, the racism that he had experienced before and during the war created deep emotional distress, which was exacerbated by the breakup of his first two marriages to white women.

During the 1950's, his alcoholism and his inadequate diet contributed to a precipitous decline in his health. In 1959, after returning from an engagement in Paris, he died at the Hotel Alvin, located on "the musician's crossroad" at Fifty-second Street and Broadway in New York City. The Music Young had a deep and lasting influence on the development of modern jazz by creating a unique improvisatory style and a new type of jazz, sometimes called cool, because of its avoidance of emotional excess. By his nonconformity in music, dress, and behavior, and through the jazz argot he helped to popularize, Young influenced not only jazz musicians but also such Beat writers as Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. In fact, his jazz solos have often been characterized in terms of poetry, since his improvisations flowed like a good conversation.

He reveled in surprising combinations of sounds, the way a poet delights in a revelatory ordering of words. Sax Style. During his early career, Young's songlike style was sometimes compared unfavorably to the robust approach of Coleman Hawkins on the tenor saxophone. Young had a light tone, whereas Hawkins had a rich, rounded tone. Young had a slow vibrato, while Hawkins's was fast. Young's phrasing was smooth, melodic, and economical, where unplayed notes often had as important a role as played ones. Hawkins, on the other hand, constructed his expressive solos with a Baroque profusion of notes. One critic called Hawkins the "Rubens of jazz", while Young was its C?zanne. Young took Hawkins's place in Fletcher Henderson's orchestra, but he was quickly let go because he refused to duplicate Hawkins's sound and style. Young's graceful, melodic approach to tenor saxophone playing achieved success largely through his recordings with the Count Basie Orchestra and with small groups of Basie sidemen. His solos on such big band favorites as "One o'Clock Jump" and "Jive at Five" were so admired that Young imitators memorized them note for note.

Even more influential were Young's solos in Basie sextets and septets. For example, some jazz musicians view his improvisations on the 1936 version of "Lady Be Good" as the best solo he ever recorded. In 1939 his recording of "Lester Leaps In", with the Kansas City Seven, was so successful that it became his signature tune (it was supposedly named because Lester arrived late for a take on his composition). Working with Billie Holiday. Young's recordings with the vocalist Holiday are legendary. She gave him the nickname "Pres" because he was the "President" of all saxophone players, and he affectionately nicknamed her "Lady Day". Holiday was attracted to Young's shy, sensitive personality, and she found his melodic and conversational improvisations compatible with the way she interpreted songs.

Young believed that a song's lyrics were important in his improvisations, both when he soloed and when he accompanied singers. In his improvisations he edited, reworked, and transformed the song's melody, while managing to create a unified solo or accompaniment that deepened and expanded the song's message and mood. So intimate was the rapport he achieved with Holiday on songs such as "The Man I Love" and "All of Me" that they seem to be thinking each other's thoughts. Something similar happened when Young collaborated with such talented instrumentalists as the guitarist CharlieChristian and the clarinetist Benny Goodman. After Prison. Acontroversy exists among aficionados and jazz critics over the quality of Young's music after his release from prison in 1945. Some believe that emotional and physical suffering sapped his will to create, and his work in small groups and large orchestras rarely equaled, and never surpassed, the high quality of his work in the late 1930's and the early 1940's.

Other critics and such jazz musicians as Sonny Rollins dispute this evaluation. They observe Young conquering the depths of his despair to achieve his greatest musical creativity. For example, these commentators view his recording of "These Foolish Things", in his first session as a free man, as a masterpiece. Furthermore, his solos on "Lester Leaps In" during the Jazz at the Philharmonic tours exhibit consistently inspiring musicianship. Even as late as 1957, when he appeared for the last time with Holiday on the CBS television show Sound of Jazz, the sensitivity and creativity of their collaboration on Holiday's tune "Fine and Mellow" left musicians and viewers deeply moved. Musical Legacy Some scholars consider Young to be the greatest tenor player of all time, whereas others pair him with Hawkins as the two most vital creators of how the tenor is used in modern jazz. Young introduced a new sensibility into improvisations by creating a rhythmic flexibility and melodic richness that was malleable enough to transform both ballads and up-tempo tunes into a new jazz style that some called cool, a term that Young may have coined.

He had a major influence on many young tenor players, including Stan Getz, Zoot Sims, Al Cohn, Illinois Jacquet, and Dexter Gordon. Paul Quinichette based his style so closely on Young's that he was given the nickname "Vice Pres". Young also had an influence on other instrumentalists, including trumpeters, trombonists, and pianists. Some have claimed that Charlie Parker's alto sound was reminiscent of Young's tenor sound, but Parker responded that, though he deeply admired Young, his (Young's) style was in an entirely different musical world.

Some have described Miles Davis's Birth of the Cool album as an orchestration of Young's tenor sound. Young's influence extended even into motion pictures. In the film 'Round Midnight (1986), which some have called the best jazz film ever made, the principal character is largely based on Young. Bertrand Tavernier, the director, dedicated the film to Young and Bud Powell, and DexterGordon,who played the central figure, received an Academy Award nomination for his performance. In this way, through recordings and films, Lester Young's legacy lives on.

Last recording session with longtime close friend and colleague Billie Holiday (Lester is to Billie's left in photo above). This session was filmed in 1958 for American television. Prez and LadyDay (Lester's nickname for Billie) both died within a month of each other in 1959). Young was 49 and Holiday was 44 when they died.

http://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/lesteryoung

Primary Instrument: Saxophone

LESTER YOUNG

Born: August 27, 1909 | Died: March 15, 1959

Lester “Prez” Young was one of the giants of the tenor saxophone. He was the greatest improviser between Coleman Hawkins and Louis Armstrong of the 1920s and Charlie Parker in the 1940s. From the beginning, he set out to be different: He had his own lingo; In the Forties, he grew his hair out. The other tenor players held their saxophones upright in front of them, so Young held his out to the side, kind of like a flute (see picture above). Then, there was the way he played: Hawkins played around harmonic runs. He played flurries of notes and had a HUGE tone that the other tenor players of the day emulated. Young used a softer tone that resulted In a soft, light sound (if you didn't know better, you would think the two were playing different instruments). Young used less notes and slurred notes together, creating more melodic solos. He played the ordinary in an extraordinary way, using a lot of subtleties to produce music that Billie Holiday said flips you out of your seat with surprise.

Young moved to Kansas City in the 1930s, the hotbed of jazz during that time, and played in various groups, including King Oliver, Benny Moten, and the traveling Fletcher Henderson orchestra. One of the great jazz myths says that Hawkins, who was the star player of Henderson's orchestra missed a show. Young filled in for him and played so wonderfully, that Hawkins went looking for Young, with sax in hand, to teach the young whippersnapper a lesson. They dueled all night and into the next morning. Hawkins left for Europe and Young took over in Henderson's orchestra. However, the ending wasn't happy — Young was hired to play like Hawkins, and that wasn't Young's thing—he could replace Hawkins, but he wasn't going to impersonate him—so he moved back to Kansas City and in 1936, he joined the Count Basie Orchestra and stayed there until 1949. While he recorded some his finest material with Basie, he didn't record all of his finest recordings with Count. He recorded a fine series of records with Billie Holiday. Within 4 years, he had played in top-rated big band AND small group settings! Some sources say that he gave her the nickname “Lady Day” and she gave him the nickname “Prez” (others say he became the new Prez-ident when he defeated Hawkins).

In 1944, Young was drafted in the Army. Going from bohemian to rigid institutional life didn't set well with Young and when he was caught smoking marijuana, he was court- martialed and spent months in detention. He came back a fine player, but his light, airy, happy tone had left and his music had a darker side to it. He joined Norman Granz' Jazz at the Philharmonic tour, but he let his health decline, and drank far more often and was hospitalized. He had an unsuccessful engagement in Paris in 1959, and returned to the States a sick man and died a year later, at the age of 49. His life (and Bud Powell's) was the basis for Bernard Tavernier's film Round Midnight, and the character based on him was played by Dexter Gordon.

Lester Young at the Famous Door, New York, N.Y., ca. September 1946. Photo by William P. Gottlieb.

Lester's Porkpie Hat

http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/04/12/how-lester-young-invented-cool.html

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

April 12, 2015

How Lester Young Invented Cool

by Ted Gioa

The Daily Beast

Not

content to invent a much-copied yet incomparable musical style, jazz

saxophonist Lester Young indelibly shaped American speech, too, from

cool to crib to homeboy.

Who is the most influential musician in the history of jazz? Is it Louis Armstrong or Miles Davis? Billie Holiday or Duke Ellington? Benny Goodman or Thelonious Monk? John Coltrane or Charlie Parker?

Faced with such an extraordinary range of choices, I simply can’t make up my mind. So, forgive me, but I refuse to answer that question.

But let me ask a slightly different one: Which jazz artist had the greatest influence outside the world of jazz? Who exerted the biggest impact on the broader culture—not on other jazz musicians, but on everybody else?

Ah, that is a question I can answer. And my answer will probably surprise you, because the name is far less well known than any of those others listed above. In fact, the jazz artist who had the greatest influence on the broader society is virtually unknown among the general public.

If you go to the web to learn about saxophonist Lester Young, you will find that he is associated with the Kansas City style of jazz that flourished in the ’30s. He only achieved the tiniest dose of fame during his lifetime—in fact, Young wasn’t even the bandleader on many of his most important recordings. Music fans were more likely to recognize the name of his boss Count Basie or his frequent collaborator Billie Holiday. During his peak earning years in the ’50s, Young earned $500 or $750 during a good week. That was a sweet paycheck for a working stiff in the Eisenhower years, but hardly the income of a world-changing entertainer.

But Lester Young changed the world, and has never gotten the credit for it.

Let me start with the music. Here you need to look outside the jazz world to gauge Young’s importance. I almost never hear young jazz saxophonists drawing on his cool jazz style. But when I encounter a saxophone in almost any other setting, I can hear Young’s influence. I hear echoes of his smooth, beguiling sound on movie soundtracks, on pop recordings behind the singer’s vocal, on bossa nova albums, even in elevator music.

When Pulitzer Prize-winning composer John Adams released a recording of his classical saxophone concerto last year, I was hardly surprised to hear hints of Young’s tenor sax sound in the music. Saxophone is not a standard instrument in a symphony orchestra, but when it does show up at the classical concert hall, the tone usually comes straight out of the Lester Young playbook. But you will never see his name mentioned in the program notes.

The term “crossover” didn’t exist in the jazz world back in Lester Young’s day, but in many ways he pioneered the concept. He created a style and aesthetic vision perfectly adapted for assimilation by other music genres. His relaxed phrasing, melodic gift, and lucent tone just seem to fit perfectly into every setting, whether it be the musical background to a TV commercial or the first dance at the wedding reception.

Yet Lester Young may have had even more influence on non-musical matters. No one back in the ’30s would have applied the terms “androgyny” or “metrosexual” to this big band saxophonist, but with the benefit of hindsight, we can see that Young was subverting sex roles at every turn. By referring to his male friends—or even casual acquaintances—as “lady,” he was undercutting the macho culture of jazz at the roots. Some people thought Lester Young was homosexual; others merely that he was an odd duck. (During his military stint, a psychiatrist diagnosed Young as “a constitutional psychopath.”) But everyone could see his stubborn refusal to take on the typical masculine stances of the day. Critic Nat Hentoff, who doubted that Young was gay, noted his “effeminate gain and hand gestures” and recalls that the saxophonist had “longer hair than that of any male jazz musician I had ever seen before.” Young’s fellow musicians in the Basie band sometimes referred to Young as “Miss Thing.”

I will leave it to others to debate Lester Young’s sexual orientation. Frankly, I don’t have much interest in his bedroom proclivities. But I can’t help but admire the courage he showed in blurring traditional boundaries of masculinity and femininity on the bandstand or out among the public. I don’t hesitate for a second in giving him credit as a key forerunner of David Bowie, Prince, and all the other late 20th century performers who took that same gender-bending formula and rode it to superstardom.

Last, but hardly least, we arrive at Lester Young’s influence on the English language. When I wrote a book on the history of “cool” a few years back, I tried to unlock the mystery of that word’s changing meaning. “Cool” had long been a negative term, signifying aloofness, emotional deadness, and sometimes even antisocial violence. Hemingway once wrote: “I’d like to cool you, you rummy fake.” I can assure you it wasn’t intended as a compliment. But somehow the term flip-flopped during the ’40s and ’50s. “Cool” emerged as the preferred adjective to describe a hip stylishness.

Who spurred this linguistic shift? According to my research, Lester Young was the catalyst. More than a dozen fellow musicians later attested that Young invented this usage. Even today, more than a half-century after Young’s death, this meaning of the word is embedded in everyday speech. Everywhere you go, you encounter “cool” as a positive affirmation, whether in casual conversation, text messages or marketing pitches.‘Lester Young was calling Count Basie “homeboy” 90 years ago,’ Quincy Jones said. ‘There were the jazz guys, and the hip-hop guys took it from them.’

Lester Young also invented a host of other unusual phrases. Some entered the common vernacular, for example his use of the term “bread” to refer to money or “crib” as a way of signifying one’s home base. He may have been the first to use the verb “dig” to describe a deeper degree of perception. Do you dig? But most of his colorful language never extended beyond his own personal orbit. No one today would refer to someone with an illness as “Johnny Deathbed,” but if you were talking to Lester in the ’50s, you might hear just that.

And what about hip-hop? Could Mr. Young have left his fingerprints on the modern day rapper? “Lester Young was calling Count Basie ‘homeboy’ 90 years ago,” Quincy Jones recently told an interviewer. “There were the jazz guys, and the hip-hop guys took it from them.” Kanye and Eminem probably couldn’t tell Lester Young from La Monte Young, but does it really matter? Any modern-day musician trying to impose a sassy personal vernacular on the King’s English is following in the footsteps of this stalwart of Kansas City jazz.

So let’s give Lester Young his due. He never made much bread—certainly not as much as his homeboys—or lived in a cool crib. But he had more impact on American society any other jazz musician. Almost no one knows his name, but we are still dancing to his tune. You dig?

http://jazztimes.com/articles/17047-lester-young-presidential-record

July/August 2006

Lester Young: Presidential Record

by Michael Kabran

JazzTimes

The records themselves look unimpressive: A set of old black

16-inch lacquered discs with yellowed labels and dusty faces aged from

years in storage. The sound on the discs, on the other hand, is

unmistakable: A rich tenor saxophone lightly fluttering above a blitz of

horns, piano and drums. There’s no doubt about it: It’s gotta be Pres.

Photo: Michaela McNichol

Eugene DeAnna, head of the Recorded Sound

Section at the Library of Congress, displays the 16-inch lacquer disc

labeled "Jam Session, December 29, 1940," which is a never-released

original recording of saxophonist Lester Young and a band improvising in

a jazz club

The Library of Congress recently announced that it has unearthed an

extremely rare live recording of legendary saxophonist Lester Young from

1940. The recording provides a glimpse into Young’s playing at a

pivotal (and little documented) point in his musical development,

between his late 1930s work with Count Basie and his years in the army.

However, nearly as impressive as the playing is the story behind the recording’s discovery, which seems like something out of a Hollywood screenplay.

In 2001, a Library of Congress team was digitizing a 1940 Zora Neale Hurston silent film that documented rural African-American life in South Carolina. While working on the project, the team received a letter from a California man who claimed to possess audio recordings to match the film. He said Hurston’s team hired him to record the film’s sound. In 2002, the man, Norman Chalfin, donated his entire collection of 150 recordings to the Library of Congress and catalogers began the immense task of sifting through the discs to find the Hurston sound recordings.

Then the team made the discovery of a lifetime.

Among Chalfin’s recordings was a sloppily labeled disc set. “It had some Beethoven sonata crossed out,” says Eugene DeAnna, head of the recorded sound section at the Library of Congress. “Written over top of that, it said ‘Jam Session, Dec. 29, 1940’ with the first initial and last name of five different people.”

One of those people was “L. Young.”

“We all looked at the label and thought, ‘Could it be Lester?’” DeAnna recalls.

It was definitely serendipity and most definitely Lester.

“I was stunned to hear what sounded like Lester Young [on the recording],” said Library of Congress recording lab supervisor and jazz specialist Larry Appelbaum.

Appelbaum called in jazz scholar Loren Schoenberg, who verified that it was indeed Young on the recording, playing “Royal Garden Blues” and a number of unidentified blues.

After some research, DeAnna learned that Chalfin was an aspiring audio engineer during the 1940s while he attended college in New York City. He was in fact hired by Hurston’s team to make the South Carolina recordings and, in his spare time, he documented live music at clubs in the city.

It’s not entirely clear where the 35-minute Young recording took place, though some have said it’s most likely the Village Vanguard.

“When the recording starts, you can hear someone ask people to quiet down so you could hear the music,” DeAnna explains, adding that the voice probably belongs to Chalfin. “At another point, you can hear someone say the chili con carne is ready.”

Young is joined on the recording by trumpeter Shad Collins, drummer Harold “Doc” West, trombonist J.C. Higginbotham and Sammy Price on piano, all musicians who regularly accompanied him in the early 1940s.

“On the commercial recordings Lester made in the ’30s with Basie and others, his solos are generally short—because those 78 rpm discs only ran two-and-a-half to three minutes,” Appelbaum says. “On these discs, he stretches out more and it’s very much about feeling rather than virtuosity.”

This discovery is important not only in the jazz community but within the canon of recorded music.

“Imagine a new Shakespearean sonnet, Chopin nocturne or Hemingway short story—that’s what we have here—an American master, a true iconoclast at his very best,” Schoenberg writes in a press release.

Digital versions of the discs are available for listening at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

DeAnna hopes one day the recording will be available in stores, similar to the recently released Thelonious Monk Quartet With John Coltrane at Carnegie Hall (Blue Note), which was also discovered at the Library of Congress.

It is not known if Chalfin’s collection contains any other recordings of Young, who died in 1959.

As for Chalfin himself, he has since passed away, though he quit being a recording engineer in the 1940s to pursue law. For jazz fans, that’s looking like an unfortunate career move indeed.

https://lesterlives.wordpress.com/

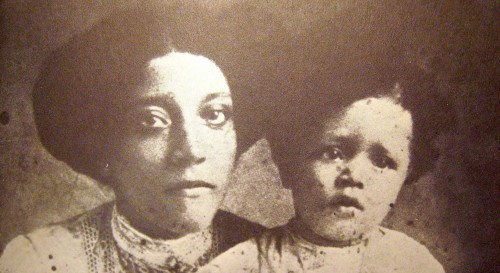

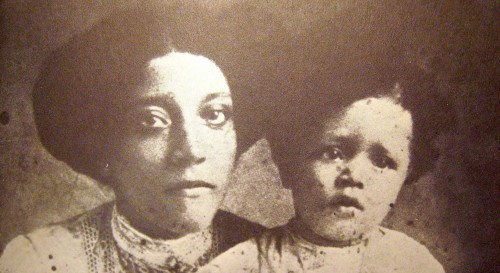

Lester and his mother Mrs. Lizetta Young

Lester Young was born August 27, 1909. His mother Lizetta left New Orleans and traveled up river to the family home in Woodville to have her first child. This small Mississippi town is known for two wildly different Presidents: Lester Willis Young and Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Lester never spoke much about being from Mississippi. His actions spoke louder when he left his father’s band in the 1920’s because he didn’t want to submit to traveling the toxic landscapes of the south. When I look into the eyes of Lester and his mother I wonder if Lizetta’s people were enslaved at the Rosemont Plantation that was owned by the Davis family. I wonder about all the American horrors that effected Lester’s kin before he was born. The deeper I look the more questions I have.

War too had its effect on both men. The confederate president’s citizenship was revoked while Lester was court-martialed, imprisoned and dismissed with a dishonorable discharge. When Pres finally left the detention barracks he transformed the poison of his incarceration into beautiful swing – writing 'D.B. Blues'. Pres didn’t talk much about the Army but laid down the sweet and the bitter in his music. Gene Ramey says. “Every night those guards would get drunk and come out there and have target practice on his head.” Lester said it was “a nightmare, man, one mad nightmare.”

In 1979 Jefferson Davis’s citizenship was fully restored by the United States Senate. In 2015 Lester’s dishonorable discharge still holds valid. I propose that Lester’s Dishonorable Discharge be upgraded to an honorable. What do you think? I want to find a lawyer who will take on the cause to get the dis off the record of a very honorable man. You want to help? Let me know. www.lesterlives.wordpress.com

Here’s a great 1946 version of "DB Blues" on Jack Dupps channel. The tune opens with little patter by Pres:

However, nearly as impressive as the playing is the story behind the recording’s discovery, which seems like something out of a Hollywood screenplay.

In 2001, a Library of Congress team was digitizing a 1940 Zora Neale Hurston silent film that documented rural African-American life in South Carolina. While working on the project, the team received a letter from a California man who claimed to possess audio recordings to match the film. He said Hurston’s team hired him to record the film’s sound. In 2002, the man, Norman Chalfin, donated his entire collection of 150 recordings to the Library of Congress and catalogers began the immense task of sifting through the discs to find the Hurston sound recordings.

Then the team made the discovery of a lifetime.

Among Chalfin’s recordings was a sloppily labeled disc set. “It had some Beethoven sonata crossed out,” says Eugene DeAnna, head of the recorded sound section at the Library of Congress. “Written over top of that, it said ‘Jam Session, Dec. 29, 1940’ with the first initial and last name of five different people.”

One of those people was “L. Young.”

“We all looked at the label and thought, ‘Could it be Lester?’” DeAnna recalls.

It was definitely serendipity and most definitely Lester.

“I was stunned to hear what sounded like Lester Young [on the recording],” said Library of Congress recording lab supervisor and jazz specialist Larry Appelbaum.

Appelbaum called in jazz scholar Loren Schoenberg, who verified that it was indeed Young on the recording, playing “Royal Garden Blues” and a number of unidentified blues.

After some research, DeAnna learned that Chalfin was an aspiring audio engineer during the 1940s while he attended college in New York City. He was in fact hired by Hurston’s team to make the South Carolina recordings and, in his spare time, he documented live music at clubs in the city.

It’s not entirely clear where the 35-minute Young recording took place, though some have said it’s most likely the Village Vanguard.

“When the recording starts, you can hear someone ask people to quiet down so you could hear the music,” DeAnna explains, adding that the voice probably belongs to Chalfin. “At another point, you can hear someone say the chili con carne is ready.”

Young is joined on the recording by trumpeter Shad Collins, drummer Harold “Doc” West, trombonist J.C. Higginbotham and Sammy Price on piano, all musicians who regularly accompanied him in the early 1940s.

“On the commercial recordings Lester made in the ’30s with Basie and others, his solos are generally short—because those 78 rpm discs only ran two-and-a-half to three minutes,” Appelbaum says. “On these discs, he stretches out more and it’s very much about feeling rather than virtuosity.”

This discovery is important not only in the jazz community but within the canon of recorded music.

“Imagine a new Shakespearean sonnet, Chopin nocturne or Hemingway short story—that’s what we have here—an American master, a true iconoclast at his very best,” Schoenberg writes in a press release.

Digital versions of the discs are available for listening at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

DeAnna hopes one day the recording will be available in stores, similar to the recently released Thelonious Monk Quartet With John Coltrane at Carnegie Hall (Blue Note), which was also discovered at the Library of Congress.

It is not known if Chalfin’s collection contains any other recordings of Young, who died in 1959.

As for Chalfin himself, he has since passed away, though he quit being a recording engineer in the 1940s to pursue law. For jazz fans, that’s looking like an unfortunate career move indeed.

https://lesterlives.wordpress.com/

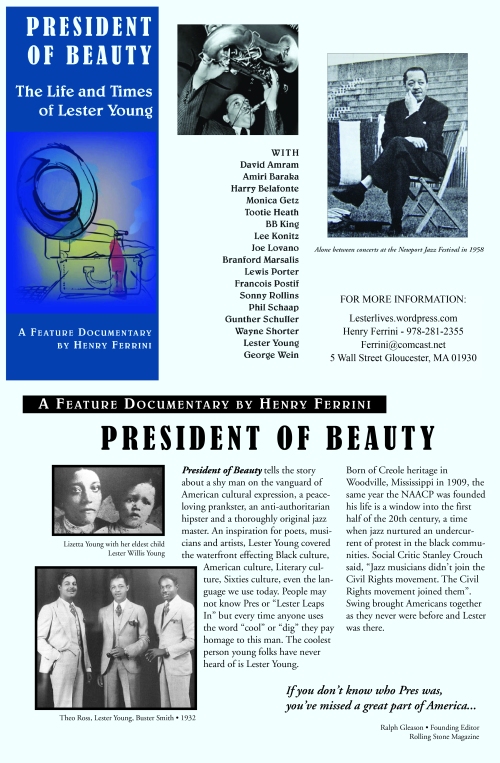

President of Beauty: The Life and Times of Lester Young

Trailer Click Below:

https://vimeo.com/119644870

Lester and his mother Mrs. Lizetta Young

Lester Young was born August 27, 1909. His mother Lizetta left New Orleans and traveled up river to the family home in Woodville to have her first child. This small Mississippi town is known for two wildly different Presidents: Lester Willis Young and Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Lester never spoke much about being from Mississippi. His actions spoke louder when he left his father’s band in the 1920’s because he didn’t want to submit to traveling the toxic landscapes of the south. When I look into the eyes of Lester and his mother I wonder if Lizetta’s people were enslaved at the Rosemont Plantation that was owned by the Davis family. I wonder about all the American horrors that effected Lester’s kin before he was born. The deeper I look the more questions I have.

War too had its effect on both men. The confederate president’s citizenship was revoked while Lester was court-martialed, imprisoned and dismissed with a dishonorable discharge. When Pres finally left the detention barracks he transformed the poison of his incarceration into beautiful swing – writing 'D.B. Blues'. Pres didn’t talk much about the Army but laid down the sweet and the bitter in his music. Gene Ramey says. “Every night those guards would get drunk and come out there and have target practice on his head.” Lester said it was “a nightmare, man, one mad nightmare.”

In 1979 Jefferson Davis’s citizenship was fully restored by the United States Senate. In 2015 Lester’s dishonorable discharge still holds valid. I propose that Lester’s Dishonorable Discharge be upgraded to an honorable. What do you think? I want to find a lawyer who will take on the cause to get the dis off the record of a very honorable man. You want to help? Let me know. www.lesterlives.wordpress.com

Here’s a great 1946 version of "DB Blues" on Jack Dupps channel. The tune opens with little patter by Pres:

Here is a beautiful poem from Jamie Reid’s book on Lester Young:

Seventy years back, Lester Young was in the Army. He was entrapped by a zoot suited officer and forced to enlist else go to prison. He was later arrested for having drugs. These were the same drugs he told the draft board about months earlier, that he needed, to get through the late nights and constant travel. This was the life of an itinerant jazz musician. Lester was court-martialed, given a dishonorable discharge, and made to forfeit all pay and allowances due or to become due. He was confined to hard labor and sent to the detention barracks at Fort Gordon, Georgia. This is how the government chose to use the genius of Lester Young. I submit his Dishonorable discharge should be revoked. Seven months after the war was over the Army realized there was no point in keeping Private 39729502 Young. Norman Granz then sent Pres a plane ticket back to LA. The long nightmare was over.

On June 25th, 2015, Jaime Reid suddenly passed away. He was 74 years old. The above film poem was finished just a few month previous to his passing. For all those interested in the life of Lester Young, check out Jamie’s book Prez: Homage to Lester Young. It is one of the most evocative volumes I’ve read about Lester.

In 2014 Lester Young will have been gone 55 years, yet this swinging star shines brightly in the film-in-progress. In the film, Sonny Rollins calls Lester “god”, and a god he was for many players who paid their dues at mid-Century. The four-minute trailer includes interviews with Sonny Rollins, Harry Belafonte, Wayne Shorter, B.B. King, Lee Konitz, Joe Lovano, George Wein, David Amram, Amiri Baraka, Junior Mance, and Gunther Schuller. Collecting these interviews has been an ongoing process for about two years. Here are some pictures from the two-year journey that resulted in this trailer.

As a longtime documentary veteran, my approach uses contemporary places combined with archival film, interviews and music to evoke our shared history. In President of Beauty: The Life and Times of Lester Young, the music and America’s troubled social history combine to evoke a sense of this much-misunderstood American genius.

Years ago I began this process when I heard Phil Schaap play François Postif’s interview with Pres on the radio. I immediately knew this would be my next film. I wrote Postif inquiring about the rights. He in turn put me in touch with Michel DeLorme and I secured the rights. This historic forty-five minute audio interview recorded five weeks before Lester passed creates the narrative arc of the President of Beauty.

The film is now at a point where I need to work in the cities where Lester was domiciled. Shooting will take place in Los Angeles, New Orleans, Mississippi, Minneapolis, Paris and Kansas City with many more interviews to come. Ornette Coleman, René Urteger, Dan Morgenstern, Lewis Porter, and Don Byron. Interviews with artists, animation that visualizes Lester in his Paris Hotel, archival performances, and contemporary footage of Lester, comprise the visuals.

Today much has been accomplished on little funding. Having only shot interviews, my signature, as well as Lester’s, is not yet on this film. I need to catch the dawn over the Mississippi River, dusk at 12th Street and Vine, the rain on the streets of Paris and the intimate atmosphere of listening to jazz. Lester lives in these shadows of our cultural memory. I need your help to preserve what is here now by bringing Lester Young into focus. I need to connect with the world’s Presophiles to help raise the funding to tell Lester’s story with film. Thank you for your time and consideration. If you have any question please email.

________________________________________________________________

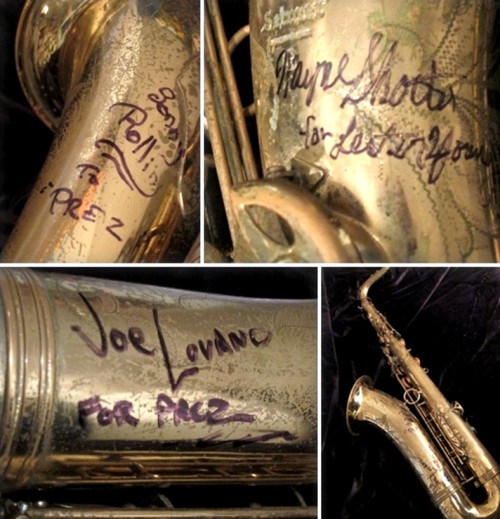

In order to raise funds for the film, we are having a silent auction on a Selmer Mark VI tenor sax. #209100 This is no ordinary saxophone. The horn is signed by Sonny Rollins, Wayne Shorter, Branford Marsalis, (picture not shown) and Joe Lovano who all have participated in the film. I will be interviewing Branford Marsalis in the coming months and will see if he wants to add his name. The perfectly playable horn was donated by a supporter and is valued from $3000-4000. I hope to raise significantly more. Anything above the value of the horn is tax-deductible.

________________________________________________________________

Billie Holiday’s birthday was on April 7th 1915. She was 44 years old. This year marks a hundred years since she has passed. Just like one of her closest friends, Lester Young, she too died too young. To commemorate the relationship between these two iconic musicians and how they revolutionized jazz, we post three videos between march 15th (Lester Young’s death day) and April 7. (Billie Holiday’s birthday) If you like what you saw and want to help the film, check out our donation film page. This film is being made by the generosity of Lester Lovers. We need your help!

From Fort Gordon to Ferguson

From this picture you would think life in the U.S. Army was a cakewalk for Lester Young. Playing his horn, Joe Jones smiling in the back, as Italians say, dolce far niente. That is exactly what the Army would have wanted you to believe. The truth is quite the opposite.

Sixty-nine years ago today Lester Young was dishonorably discharged from the military. Early in 1945 he was court-martialed and sentenced to a year’s time at Fort Gordon, Georgia for possession of barbiturates and marijuana. A habit Lester was truthful about prior to his induction. Why did the military want a man with an acute drug and alcohol dependency?

We don’t know what degradations Lester suffered throughout his 10 months imprisonment. His own words state it bluntly, “A nightmare, man, one mad nightmare.” Bystanders report white guards who saw a picture of Lester’s wife, a white woman, tormented the prisoner. Writer Michael Steinman says, “he was a tall handsome light-skinned black man with an effeminate manner, high voice, funny way of speaking…I imagine those other inmates held him down, beat him, and raped him…” There is no documentary proof of this happening but many agree that Lester was a changed man when he got out of the Army.

Sixty-nine years after his release from the detention barracks, I wonder if this dishonorable discharge could be expunged from the record? Why did the Army not remand Lester until drug and alcohol issues where dealt with? Did Lester know his rights as a Conscientious objector? Any military lawyers out there think there is a case? One-thing writers agree on, Lester Young was an honorable man. Stan Getz’s wife Monica calls him, “the most sensitive and ethical man I ever met.” His music remains as a testament to truth, Beauty & Truth. Looking at America’s struggle against institutional racism today, it doesn’t seem like a very long ride from Fort Gordon, Alabama to Ferguson, Missouri. Lester’s mad nightmare like the death of Michael Brown stems from the same question Mychal Denzel Smith asks in his Nation article. “What is justice in a nation built on white supremacy and the destruction of black bodies? That’s the question we have yet to answer. It’s the question that shakes us up and makes our insides uncomfortable. It’s the question that causes great unrest.”

From Paris, during his last recorded interview in 1959, Lester wraps up his feelings on America by saying to Le Hot Jazz journalist François Postif. “They want everyone who’s a Negro to be an Uncle Tom, an Uncle Remus or an Uncle Sam, and I can’t make it. But it’s the same way all over. You just fight for your life. You dig? Until death do we part. You got it made.” A few months later Pres was gone. He was 49 years old.

“I have been watching clips of “President of Beauty” with a mounting sense of anticipation and excitement. Ferrini has thought long and hard about his subject, Lester Young, and for many, many years.” – Ammiel Alcalay

For the full Letter https://lesterlives.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/alcalay-president-of-beauty-letter1.

“Mr. Ferrini’s awareness of this very simple but profound fact reveals an impressive understanding of the subject on his part. His use of Young’s last interview, available on audiotape, as a narrative device provides the saxophonist’s own commentary on his life and givethe project a rare authenticity.”

For the full Letter https://lesterlives.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/douglas-henry-daniels.jpg

For the full Letter https://lesterlives.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/alcalay-president-of-beauty-letter1.

“Mr. Ferrini’s awareness of this very simple but profound fact reveals an impressive understanding of the subject on his part. His use of Young’s last interview, available on audiotape, as a narrative device provides the saxophonist’s own commentary on his life and givethe project a rare authenticity.”

– Douglas Henry Daniels

For the full Letter https://lesterlives.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/douglas-henry-daniels.jpg

“Ferrini is renowned for his “poetic style..brilliant filmwork in such documentaries as Polis is This: Charles Olson and the Persistence of Place (on the poet Charles Olson), a documentary on the writer Jack Kerouac, and others, provide ample proof of the superb artistic merit of Ferrini’s film making.”

For the full Letter https://lesterlives.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/ed-sanders.jpg

-Ed Sanders

“The poignant and imaginative telling of the life and times of Lester Young will create a space for a vigorous discussion about the impact of art on society…

Henry has the unique ability to take biographical and ethnographic information and weave a tapestry of images and multi-layered sound that transcend being merely an account of someone’s life. His films become a visceral experience of the human spirit.”

For the full Letter https://lesterlives.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/susanne-rostock.jpg

Henry has the unique ability to take biographical and ethnographic information and weave a tapestry of images and multi-layered sound that transcend being merely an account of someone’s life. His films become a visceral experience of the human spirit.”

– Susanne Rostock

Posted in Uncategorized

In this clip from http://www.artistshousemusic.org – On Sunday, December 12, 2004, Hank Jones gave a lecture/interview to a master class produced by John Snyder of Artists House Foundation and David Schroeder of the NYU jazz department. Many topics were brought up including the late great Lester Young.

Posted in Interviews

Thanks are in order to father and son animation team, Jim and

Ben Wickey, from Rockport Ma, for sitting down with us to sketch out

some ideas for animating President of Beauty.

Here are some sketches

Here are some sketches

Posted in Uncategorized

For 44 years Phil Schaap at WKCR radio has been paying tribute

to Lester Young. On August 27, 2012 we visited him in the studio during

the Lester Young/Charlie Parker Birthday celebration. We shot a lot of

great stuff and hope to use for the movie “President of Beauty:the Life

& Times of Lester Young. This is a snippet of the shoot.

http://dothemath.typepad.com/dtm/lester-young-centennial.html

http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/prez-lester-young

On this date in 1909, African American jazz saxophonist Lester Young was born.

His name at birth was Willis Lester Young and he was from a musical family in Woodville, Mississippi. He spent his childhood with his mother, sister, and brother in Algiers, Louisiana, a suburb of New Orleans, where he was introduced to jazz. At the age of 10, Young and his family traveled throughout the south with a carnival minstrel band. Starting out on drums, he then began to play C-melody and alto saxophone prior to choosing the tenor. The family band settled in Minneapolis in 1926, but traveled throughout the northern plain states playing primarily for dances.

After the group moved to Los Angeles in the late 1920s, Young joined the original Blue Devils (based in Oklahoma City) in 1932. He also played with King Oliver and Count Basie before gaining national attention as Coleman Hawkins' replacement with Fletcher Henderson in 1934. Many of his best-known recordings were made at this time, including "Oh Lady Be Good," "Jive at Five," "Lester Leaps In," "Shoe Shine Boy," and others. Young also recorded a number of sessions with small groups under the leadership of Teddy Wilson and Billie Holiday (who allegedly gave him his nickname “Pres” or “Prez”).

He played with the Basie band a number of times and in between led his own group in Louisiana and New York City. He did have a life-turning pause from playing when he was inducted in the U. S. Army in the fall of 1944. His military service led to a court martial and a year of detention for drug use. This enhanced his dependence on alcohol, which plagued him for the rest of his life. In 1946, he joined Norma Granz’s touring concert series, and in the 1950s, he developed a new darker, less buoyant style in tone.

Lester Young’s playing remained at an extraordinarily high level until his death in New York a day after returning from Paris on March 15, 1959.

Reference:

Jazz: A History of the New York Scene

Samuel Charters and Leonard Kunstadt

(Doubleday, Garden City, N.Y., 1962)

http://dothemath.typepad.com/dtm/lester-young-centennial.html

Lester Young Centennial

(Reprinted from old DTM, originally posted on August 27, 2009.)

Lester Young was born 100 years ago today. He died just over 50 years ago in March 1959.

Young is the most important link in the chain between early jazz and modern jazz. He sounded good playing with the New Orleans-style musicians grew up with; if he were around now he could sit in at Smalls tonight.

---

Pre-1950, few jazz musicians continuously invented new phrases, but serious Young fans chase down every obscure bootleg because he might have played something brand new. He had one of the most swinging beats in the history of the music. And though he could deliver a honking, stomping tenor, even his most frantic outbursts sound curiously relaxed. He never tried too hard. He just was: Cool.

In fact, he may have literally invented the word “cool” and given it to the English language, for his verbal jousting and pre-beatnik beatnik behavior gave him a iconic mystique almost inseparable from the sounds coming out of his horn.

The improvisation, the beat, and the mystique made Lester Young one of the most well-loved musicians of the 20th century. I'm trying to learn from him in the 21st.

1) 18 with Lee K.

2) Oh, Lady!

3) Calling the Masters

4) The Power of Vulnerability

5) Miles Davis and Lester Young

6) A Beginner’s Guide to the Master Takes

7) The End and the Future

8) Top and Bottom

9) Footnotes

10) Further Reading

http://www.welwyn11.freeserve.co.uk/LY_notes.htm

| Home

| Recording Chronology | CD

List |

Born

into a musical family, Lester grew up in New Orleans and was taught to play

a variety of instruments by his father. The family moved to Minneapolis in 1919

and he started playing drums in the family band, later switching to alto sax.

Around 1928 he left to tour with Art Bronson's Bostonians, adopting the tenor

saxophone. He stayed with Bronson until 1930, with interludes playing with the

family and various other bands. 1931 found him playing in various clubs around

Minneapolis but in 1932 he joined Walter Page's "Original Blue Devils"

and toured extensively. Towards the end of 1933 the Blue Devils were disbanded

and Young was one of several members of the band who joined Bennie Moten in

Kansas City. During the next few years Young played in the bands of Moten, King

Oliver, Count Basie, Fletcher Henderson, Andy Kirk and others. In 1936 he rejoined

Basie in Kansas City and made his first recordings

at the age

of 27,

when his radically new

style was already set. He

remained with Basie for the next four years, touring, broadcasting and recording.

He also recorded in small groups directed by Teddy Wilson and others and appeared

on several classic record dates backing Billie Holiday (she nicknamed him 'Pres'

, for president of the saxophone, while he called her 'Lady Day'). In the early

40s he freelanced, and sometimes led, small groups in the Los Angeles area alongside

his brother Lee Young, and musicians such as Red Callender, Nat 'King' Cole

and Al Sears. In 1943 he returned briefly to the Basie band, and also worked

with Dizzy Gillespie. He had just finished filming the classic jazz film 'Jammin'

the Blues' in September 1944 when the draft board caught up with him. After

periods in hospital and the stockade he emerged in December 1945 to the new

trend of bebop. At this time he also joined Granz's 'Jazz At The Philharmonic'

roadshow, remaining for a number of years. He also led small groups for club

and record dates, toured the USA and visited Europe. A withdrawn, moody figure

with a dry and slightly anarchic sense of humor, Young perpetuated his own mythology

during his lifetime, partly through developing a language of his own (he coined

the use of 'bread' to denote money). Despite a long period of poor health he

continued to record and make concert appearances up to the end. He died in 1959

shortly after returning from Paris.

Born

into a musical family, Lester grew up in New Orleans and was taught to play

a variety of instruments by his father. The family moved to Minneapolis in 1919

and he started playing drums in the family band, later switching to alto sax.

Around 1928 he left to tour with Art Bronson's Bostonians, adopting the tenor

saxophone. He stayed with Bronson until 1930, with interludes playing with the

family and various other bands. 1931 found him playing in various clubs around

Minneapolis but in 1932 he joined Walter Page's "Original Blue Devils"

and toured extensively. Towards the end of 1933 the Blue Devils were disbanded

and Young was one of several members of the band who joined Bennie Moten in

Kansas City. During the next few years Young played in the bands of Moten, King

Oliver, Count Basie, Fletcher Henderson, Andy Kirk and others. In 1936 he rejoined

Basie in Kansas City and made his first recordings

at the age

of 27,

when his radically new

style was already set. He

remained with Basie for the next four years, touring, broadcasting and recording.

He also recorded in small groups directed by Teddy Wilson and others and appeared

on several classic record dates backing Billie Holiday (she nicknamed him 'Pres'

, for president of the saxophone, while he called her 'Lady Day'). In the early

40s he freelanced, and sometimes led, small groups in the Los Angeles area alongside

his brother Lee Young, and musicians such as Red Callender, Nat 'King' Cole

and Al Sears. In 1943 he returned briefly to the Basie band, and also worked

with Dizzy Gillespie. He had just finished filming the classic jazz film 'Jammin'

the Blues' in September 1944 when the draft board caught up with him. After

periods in hospital and the stockade he emerged in December 1945 to the new

trend of bebop. At this time he also joined Granz's 'Jazz At The Philharmonic'

roadshow, remaining for a number of years. He also led small groups for club

and record dates, toured the USA and visited Europe. A withdrawn, moody figure

with a dry and slightly anarchic sense of humor, Young perpetuated his own mythology

during his lifetime, partly through developing a language of his own (he coined

the use of 'bread' to denote money). Despite a long period of poor health he

continued to record and make concert appearances up to the end. He died in 1959

shortly after returning from Paris.

One of the seminal figures in jazz history and a major influence in creating the musical atmosphere in which bop could flourish, Young's playing was at the time the cause of controversy. Only his middle period appears to have earned unreserved critical acclaim. In recent years, however, thanks in part to a more enlightened body of critical opinion, allied to perceptive biographies (by Dave Gelly and Lewis Porter), few observers now have anything other than praise for his entire output. In the early years of jazz the saxophone family were not favored and only the clarinet among the reed instruments maintained a front-line position. Coleman Hawkins gave the saxophone a higher profile, changing perceptions of the instrument and spawning many imitators of his rich and resonant sound. When Young appeared on the wider jazz scene in the early 1930's, favoring a light, acerbic, dry tone, he was in striking contrast to the majestic Hawkins. He later conceded the early influence of recordings by Frankie Trambauer and Jimmy Dorsey . Whilst many disliked what they heard a few appreciated that Young's floating

melodic style represented a distinctive and revolutionary approach to jazz.

The solos he recorded with the Basie band included many which, for all their

brevity - some no more than eight bars long - display an astonishing talent

in full flight. On his first record date, on 9 October 1936, made by a small

group drawn from the Basie band ('Jones-Smith Inc.'), he plays with what appears

at first hearing to be startling simplicity. Despite this impression, the performances,

especially of 'Shoe Shine Swing' and 'Lady

Be Good', are masterpieces seldom equaled, perhaps not even by Young

himself. He recorded many outstanding solos with the full Basie band such as

'Honeysuckle Rose', 'Taxi

War Dance' (a favourite of Young's) and 'Every

Tub' and with the small group, the Kansas City Seven, on 'Dickie's

Dream' and 'Lester Leaps In'. On all of

these recordings, Young's solos clearly indicate that, for all their emotional

depths, a great talent is at work. His sessions with Billie Holiday from 1937

- 1941 are essential listening. The empathy displayed by these two is remarkable

and at times magical, with 'Me, Myself And I',

'Mean To Me', 'When You're

Smiling', 'Foolin' Myself' and 'This

Year's Kisses' being particular highlights. His first recordings after

leaving the army in 1945, which include 'DB Blues'

and 'These Foolish Things', retain all the elegance

and style of a consummate master, confounding those critics who suggested he

was left broken after his harsh treatment. His playing had changed but only

because he had moved on. A 1956 session with Teddy Wilson, on which Young is

joined by Roy Eldridge and Jo Jones ('The Jazz Giants'), is perhaps the highlight

of his last years. Long-overlooked recordings made at about the same time with

the Bill Potts Trio, during an engagement in a bar in Washington, DC, show him

to be as inventive as ever. It is impossible to overstate Young's importance

in the development of jazz. Many of the developments in bop and post-bop were

influenced by Young's fascination for melody and the smooth, flowing lines with

which he transposed his thoughts into beautiful, articulate sounds.

Whilst many disliked what they heard a few appreciated that Young's floating

melodic style represented a distinctive and revolutionary approach to jazz.

The solos he recorded with the Basie band included many which, for all their

brevity - some no more than eight bars long - display an astonishing talent

in full flight. On his first record date, on 9 October 1936, made by a small

group drawn from the Basie band ('Jones-Smith Inc.'), he plays with what appears

at first hearing to be startling simplicity. Despite this impression, the performances,

especially of 'Shoe Shine Swing' and 'Lady

Be Good', are masterpieces seldom equaled, perhaps not even by Young

himself. He recorded many outstanding solos with the full Basie band such as

'Honeysuckle Rose', 'Taxi

War Dance' (a favourite of Young's) and 'Every

Tub' and with the small group, the Kansas City Seven, on 'Dickie's

Dream' and 'Lester Leaps In'. On all of

these recordings, Young's solos clearly indicate that, for all their emotional

depths, a great talent is at work. His sessions with Billie Holiday from 1937

- 1941 are essential listening. The empathy displayed by these two is remarkable

and at times magical, with 'Me, Myself And I',

'Mean To Me', 'When You're

Smiling', 'Foolin' Myself' and 'This

Year's Kisses' being particular highlights. His first recordings after

leaving the army in 1945, which include 'DB Blues'

and 'These Foolish Things', retain all the elegance

and style of a consummate master, confounding those critics who suggested he

was left broken after his harsh treatment. His playing had changed but only

because he had moved on. A 1956 session with Teddy Wilson, on which Young is

joined by Roy Eldridge and Jo Jones ('The Jazz Giants'), is perhaps the highlight

of his last years. Long-overlooked recordings made at about the same time with

the Bill Potts Trio, during an engagement in a bar in Washington, DC, show him

to be as inventive as ever. It is impossible to overstate Young's importance

in the development of jazz. Many of the developments in bop and post-bop were

influenced by Young's fascination for melody and the smooth, flowing lines with

which he transposed his thoughts into beautiful, articulate sounds.

The accompanying pages simply list the recording sessions. Some of those which

have found critical acclaim or are my particular favourites are highlighted.

Complete discographical details have been published elsewhere (see below) but

I've included a list of CDs covering the majority of the sessions listed. Where

alternate takes are indicated these have been issued on LP but not necessarily

on CD. For live recordings which may not have been reissued on CD refer to Lewis

Porter's book for a listing of LPs.

Any comments on presentation or omissions would be appreciated.

Clive Yeates

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Lewis Porter, Lester Young. Twayne Publishers, 1985.

An in-depth academic appraisal with a comprehensive listing of LP re-issues.

2. Dave Gelly, Lester Young (Jazz Masters Series). Spellmount,1984.

Short Biography with a selective discography.

3. Jan Evensmo, The Tenor Saxophone And Clarinet Of Lester Young, 1936-1949.

4. Frank Buchmann-Moller, You Just Fight For Your Life: The Story of Lester Young. New York: Praeger Press, 1990.

The closest thing to a reliable biography

5. Frank Buchmann-Moller, You Got To Be Original Man! The Music of Lester Young.

Greenwood Press. Wesport, Conn. 1990 (out of print)

A companion to the biography above with a guide to all of Young's recorded solos - the most comprehensive 'solography'.

6. Lewis Porter , A Lester Young Reader. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991.

Articles, interviews, reviews and anecdotes.

7. Max Harrison, Paul Oliver, Alun Morgan and Albert McCarthy, Jazz On Record - A Critical Guide to the First 50 Years: 1917-1967. London, Hanover, 1968.

8. Max Harrison, Charles Fox and Eric Thacker, The Essential Jazz Records- Vol1: Ragtime to Swing. London, Mansell, 1984.

9. Max Harrison, Eric Thacker and Stuart Nicholson, The Essential Jazz Records - Vol2: Modernism to Postmodernism. London, Mansell, 2000.

Has an appraisal of the Alladin Sessions (1945-1948).

Last updated September 10, 2000

Lester Young was born 100 years ago today. He died just over 50 years ago in March 1959.

Young is the most important link in the chain between early jazz and modern jazz. He sounded good playing with the New Orleans-style musicians grew up with; if he were around now he could sit in at Smalls tonight.

---

Pre-1950, few jazz musicians continuously invented new phrases, but serious Young fans chase down every obscure bootleg because he might have played something brand new. He had one of the most swinging beats in the history of the music. And though he could deliver a honking, stomping tenor, even his most frantic outbursts sound curiously relaxed. He never tried too hard. He just was: Cool.

In fact, he may have literally invented the word “cool” and given it to the English language, for his verbal jousting and pre-beatnik beatnik behavior gave him a iconic mystique almost inseparable from the sounds coming out of his horn.

The improvisation, the beat, and the mystique made Lester Young one of the most well-loved musicians of the 20th century. I'm trying to learn from him in the 21st.

1) 18 with Lee K.

2) Oh, Lady!

3) Calling the Masters

4) The Power of Vulnerability

5) Miles Davis and Lester Young

6) A Beginner’s Guide to the Master Takes

7) The End and the Future

8) Top and Bottom

9) Footnotes

10) Further Reading

http://www.welwyn11.freeserve.co.uk/LY_notes.htm

Lester Young Biography

Biography

b. 27 August 1909, Woodville, Mississippi, USA, d. 15 March 1959, New York City.One of the seminal figures in jazz history and a major influence in creating the musical atmosphere in which bop could flourish, Young's playing was at the time the cause of controversy. Only his middle period appears to have earned unreserved critical acclaim. In recent years, however, thanks in part to a more enlightened body of critical opinion, allied to perceptive biographies (by Dave Gelly and Lewis Porter), few observers now have anything other than praise for his entire output. In the early years of jazz the saxophone family were not favored and only the clarinet among the reed instruments maintained a front-line position. Coleman Hawkins gave the saxophone a higher profile, changing perceptions of the instrument and spawning many imitators of his rich and resonant sound. When Young appeared on the wider jazz scene in the early 1930's, favoring a light, acerbic, dry tone, he was in striking contrast to the majestic Hawkins. He later conceded the early influence of recordings by Frankie Trambauer and Jimmy Dorsey .

Notes

The accompanying pages simply list the recording sessions. Some of those which

have found critical acclaim or are my particular favourites are highlighted.

Complete discographical details have been published elsewhere (see below) but

I've included a list of CDs covering the majority of the sessions listed. Where

alternate takes are indicated these have been issued on LP but not necessarily

on CD. For live recordings which may not have been reissued on CD refer to Lewis

Porter's book for a listing of LPs.Any comments on presentation or omissions would be appreciated.

Clive Yeates

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Lewis Porter, Lester Young. Twayne Publishers, 1985. An in-depth academic appraisal with a comprehensive listing of LP re-issues.

2. Dave Gelly, Lester Young (Jazz Masters Series). Spellmount,1984.

Short Biography with a selective discography.

3. Jan Evensmo, The Tenor Saxophone And Clarinet Of Lester Young, 1936-1949.

4. Frank Buchmann-Moller, You Just Fight For Your Life: The Story of Lester Young. New York: Praeger Press, 1990.

The closest thing to a reliable biography

5. Frank Buchmann-Moller, You Got To Be Original Man! The Music of Lester Young.

Greenwood Press. Wesport, Conn. 1990 (out of print)

A companion to the biography above with a guide to all of Young's recorded solos - the most comprehensive 'solography'.

6. Lewis Porter , A Lester Young Reader. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991.

Articles, interviews, reviews and anecdotes.

7. Max Harrison, Paul Oliver, Alun Morgan and Albert McCarthy, Jazz On Record - A Critical Guide to the First 50 Years: 1917-1967. London, Hanover, 1968.

8. Max Harrison, Charles Fox and Eric Thacker, The Essential Jazz Records- Vol1: Ragtime to Swing. London, Mansell, 1984.

9. Max Harrison, Eric Thacker and Stuart Nicholson, The Essential Jazz Records - Vol2: Modernism to Postmodernism. London, Mansell, 2000.

Has an appraisal of the Alladin Sessions (1945-1948).

Last updated September 10, 2000

http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/prez-lester-young

Date of Birth:

Fri, 1909-08-27His name at birth was Willis Lester Young and he was from a musical family in Woodville, Mississippi. He spent his childhood with his mother, sister, and brother in Algiers, Louisiana, a suburb of New Orleans, where he was introduced to jazz. At the age of 10, Young and his family traveled throughout the south with a carnival minstrel band. Starting out on drums, he then began to play C-melody and alto saxophone prior to choosing the tenor. The family band settled in Minneapolis in 1926, but traveled throughout the northern plain states playing primarily for dances.

After the group moved to Los Angeles in the late 1920s, Young joined the original Blue Devils (based in Oklahoma City) in 1932. He also played with King Oliver and Count Basie before gaining national attention as Coleman Hawkins' replacement with Fletcher Henderson in 1934. Many of his best-known recordings were made at this time, including "Oh Lady Be Good," "Jive at Five," "Lester Leaps In," "Shoe Shine Boy," and others. Young also recorded a number of sessions with small groups under the leadership of Teddy Wilson and Billie Holiday (who allegedly gave him his nickname “Pres” or “Prez”).

He played with the Basie band a number of times and in between led his own group in Louisiana and New York City. He did have a life-turning pause from playing when he was inducted in the U. S. Army in the fall of 1944. His military service led to a court martial and a year of detention for drug use. This enhanced his dependence on alcohol, which plagued him for the rest of his life. In 1946, he joined Norma Granz’s touring concert series, and in the 1950s, he developed a new darker, less buoyant style in tone.

Lester Young’s playing remained at an extraordinarily high level until his death in New York a day after returning from Paris on March 15, 1959.

Reference:

Jazz: A History of the New York Scene

Samuel Charters and Leonard Kunstadt

(Doubleday, Garden City, N.Y., 1962)

THE MUSIC OF LESTER YOUNG: AN EXTENSIVE VIDEO OVERVIEW, A CROSS SECTION OF RECORDINGS, MUSICAL ANALYSIS AND COMMENTARY, PLUS VARIOUS INTERVIEWS WITH MR. YOUNG:

Lester Young 1939 ~ Original Lester Leaps In (Take 1):

Lester Young 1939 ~ Original Lester Leaps In (Take 2):

JAMMIN' THE BLUES (1944):

Jammin' the Blues is a 1944 short film in which several prominent jazz musicians got together for a rare filmed jam session. It featured Lester Young, Red Callender, Harry Edison, Marlowe Morris, Sid Catlett, Barney Kessel, Jo Jones, John Simmons, Illinois Jacquet, Marie Bryant, Archie Savage and Garland Finney. Barney Kessel is the only white performer in the film. He was seated in the shadows to shade his skin, and for closeups, his hands were stained with berry juice. The movie was directed by Gjon Mili. Producer Gordon Hollingshead was nominated for an Academy Award for this footage in the category of Best Short Subject, One-reel. In 1995, Jammin' the Blues was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Lester Young- Lester Young Trio- FULL ALBUM 1951:

Personnel:

Tracks 1 - 10: Lester Young: ts // Nat King Cole: Piano // Buddy Rich: Drums//

Tracks

11-14: Harry Edison: tp // Dexter Gordon: Ts // Nat Cole: Piano // Red

Callender or Johnny Miller: b // Buddy Rich: Drums //

Tracklisting:

1- Back To The Land

2- I Cover The Waterfront (Take 1)

3- I Cover The Waterfront (Take 2)

4- Somebody Loves Me

5- I've Found a New Baby

6- The Man I Love

7- Peg o' My heart

8- I want To Be Happy

9- Mean to Me

10- Back to the Land

11- I've Found a New Baby

12- Rosetta

13- Sweet Lorraine

14- Blowed and Gone

One

of Lester Young's most memorable post-World War II dates came in 1946,

when he entered a Los Angeles studio and formed a trio that employed Nat

King Cole on piano and Buddy Rich on drums. In 1994, the results of

that classic encounter, which Norman Granz produced for his Clef label,

were reissued on the CD Lester Young Trio. Unfortunately, the sound is

pretty scratchy, and one wishes that Verve had used digital remastering

to reduce the noise. But the performances themselves are outstanding.

From the blues "Back to the Land" to the soulful ballad statements of

"The Man I Love" and "I Cover the Waterfront," Lester Young Trio

explodes the absurd myth that Young's postwar output is of little or no

value -- a myth that many jazz critics have been all too happy to

promote. The CD's four bonus tracks (which include "Sweet Lorraine,"

"Rosetta" and "I've Found a New Baby") come from a 1943 or 1944 session

that didn't employ Young at all, but rather, was led by tenor

saxophonist Dexter Gordon and features trumpeter Harry "Sweets" Edison

and Cole, among others. Listeners might ask what that session, which was

Gordon's first as a leader, has to do with Young, and the answer is

that it illustrates Young's tremendous influence on Gordon. At that

point, Gordon still sounded a lot like Young, was still playing swing

rather than bebop and had yet to develop a recognizable sound of his

own, although by 1945, Gordon would become quite distinctive and

influential himself. Highly recommended.

The Complete Aladdin Recordings Of Lester Young

- 1/40 videos:

Lester Young & Teddy Wilson. "Pres and Teddy":

Tracklist:

1. All of Me

2. Prisoner of Love

3. Louise

4. Love Me or Leave Me

5. Taking a Chance on Love

6. Love Is Here to Stay

7. Pres Returns

1. All of Me

2. Prisoner of Love

3. Louise

4. Love Me or Leave Me

5. Taking a Chance on Love

6. Love Is Here to Stay

7. Pres Returns

Billie Holiday and Lester Young: "Fine and Mellow" (1957)

From

'The Sound of Jazz', 8 December 1957, one of the first major programs

focusing on jazz to air on American network television (CBS).

Billie Holiday with Roy Eldridge, Ben Webster, Lester Young, Gerry Mulligan and Vic Dickenson.