SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER/FALL, 2015

VOLUME ONE NUMBER FOUR

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER/FALL, 2015

VOLUME ONE NUMBER FOUR

BILLIE HOLIDAY

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

ERIC DOLPHY

July 18-24

MARVIN GAYE

July 25-31

ABBEY LINCOLN

August 1-7

RAY CHARLES

August 8-14

SADE

August 15-21

BETTY CARTER

August 22-28

CHARLIE PARKER

August 29-September 4

MICHAEL JACKSON

September 5-11

CHAKA KHAN

September 12-18

JOHN COLTRANE

September 19-25

SARAH VAUGHAN

September 26-October 2

THELONIOUS MONK

October 3-9

ERIC DOLPHY

July 18-24

MARVIN GAYE

July 25-31

ABBEY LINCOLN

August 1-7

RAY CHARLES

August 8-14

SADE

August 15-21

BETTY CARTER

August 22-28

CHARLIE PARKER

August 29-September 4

MICHAEL JACKSON

September 5-11

CHAKA KHAN

September 12-18

JOHN COLTRANE

September 19-25

SARAH VAUGHAN

September 26-October 2

THELONIOUS MONK

October 3-9

TWO GREAT BLACK GIANTS PASS ON:

RAY CHARLES & RALPH WILEY

by Kofi Natambu

June 15, 2004

The Fabulous Williams Sisters Website

@ http://williamssisters.yuku.com/

The untimely deaths of Ray Charles (1930-2004) and Ralph Wiley

(1952-2004) this past week reminds us all once again that we should

never take lightly or for granted the important roles that such

extraordinary individuals play in our lives. These truly great African

American artists of music and literature/journalism are not only going

to be deeply missed but are frankly irreplaceable in the pantheon of

legendary icons and gifted artists and individuals that our tremendous

culture have produced. I am very saddened and angry that this insidious,

reactionary nation could see fit to publically honor such a despicable,

ignorant, bigoted, and immoral gangster as Ronald Wilson Reagan/RayGun

and barely even mention the passing of such a genuine GIANT as the

immortal Ray Charles, a man of tremendous talent, vision, and creative

genius who brought so much joy, knowledge, and inspiration to millions

of people around the globe for over 50 years. There are no words that

could possibly describe what this great artist and human being was able

to accomplish in spite of pervasive racism, crippling childhood poverty,

and physical blindness. What a tower of strength, dedication, spiritual

force, and sheer creative power this man and his amazing music was and

is! Whenever I hear or see Ray Charles I think of all the many things

and people in my life who make African American culture one of the

greatest and most timeless treasures on Planet Earth. I think

particularly of the warmth, beauty, passion, and intellectual/spiritual

power of my parents who were born and raised in Georgia and Mississippi

and migrated to the North after WWII along with millions of other black

folks. That is the extraordinary generation that Ray and his music so

clearly embodied, epitomized, and represented so beautifully and that

has left us all such a wonderful legacy of what REAL ART IS. I can't

begin to tell you how captivating, enriching, and just plain SOULFUL the

experience of growing up with that music has been in my life and the

profound impact that it has had on me, my siblings, aunts, uncles,

cousins, friends, and neighbors all these years. What a great loss his

passing is. WE LOVE YOU RAY! Please don't forget his music folks and

pass it and everything it connotes and represents on to your children,

friends, and family. Like all great artists Ray Charles actually CHANGED

THE WORLD with his sound and his songs. How many people can say that?

Ray Charles, 1930 - 2004

by TIM KIRKER

September 30, 2005

All About Jazz

Often cited as "the genius of soul music, Ray Charles used his prodigious talents as singer, pianist, and bandleader to marry elements of blues and gospel into an exciting new genre. Initially ruling the R&B charts, Charles' gritty, passionate croon became the essence of soul and with his unique genre-crossing sensibility hit songs flourished throughout the 1950s and 1960s. He tackled styles as diverse as jazz, R&B, blues, pop, and country music, possessing each one fluently.

Ray Charles Robinson was born on September 23, 1930 in Albany, Georgia. Poverty and traumatic hardships shaped Ray's childhood. At five years old he witnessed the drowning of his younger brother in a laundry tub, an event that would haunt him for many years. At six Ray began losing his eye sight, presumably from untreated glaucoma, though it was never diagnosed. A year later he was completely blind.

A local general store owner became Ray's unlikely musical mentor. Wylie Pitman's Red Wing Café was home to a piano and a jukebox, two sources of alluring inspiration for a three year old boy. "Mr. Pit would often play boogie woogie piano and urged Ray to hop up and play regularly. In 1937, he was accepted on a charity grant to a school for the deaf and blind to study music. He received a formal education in composition and learned a variety of instruments including piano, organ, saxophone, clarinet, and trumpet. From the beginning his love of music was expansive, enjoying the popular big bands of the day like Artie Shaw and Count Basie or appreciating classical composers such as Chopin and Sibelius. He found pleasure in the hillbilly sounds of the Grand Ole Opry and was drawn to the soulfulness of gospel and the raw emotion of the blues. This openness to so many genres of music would become intrinsic to his own body of work.

Ray performed with various bands, including a country band, in Florida before getting the urge to move to Seattle in 1947. His reputation as a musician and arranger beginning to prosper, he and friend Gosady McKee formed a R&B/pop outfit called the McSon Trio (also misspelled Maxim Trio), in the vein of Charles Brown and his idol Nat King Cole. They recorded one major hit called "Confession Blues in 1949. Seattle was also where Ray first met a fourteen year old trumpet player named Quincy Jones. It would be a life-long friendship with occasional musical collaborations.

In the early 50s Ray rose steadily to prominence, launching hit singles with small bands and playing or arranging for others. He toured with blues artist Lowell Fulson and worked with both Guitar Slim and Ruth Brown, all of whom helped mold his own singing style. His sound now straying from the Nat King Cole inflections, it extended to blues ballads and jazz instrumentals sprinkled with gospel influences.

Atlantic Records offered him a contract late in 1952 and a hit soon followed with "It Should Have Been Me. Not until late 1954 did Ray form his own band and capitalize on the trademark blues/gospel blend that people came to know him for. Once that happened his muse broke free. Ray's warm vocal timbre relaying the spiritual screams, wails, and moans that would give birth to soul music. In a recording session that included an upbeat bop and R&B horn section he recorded his own composition "I Got a Woman. The song was buoyant with the blues, yet sung in a husky, passionate vocal straight from the gospel idiom that stemmed from Ray's Baptist church days. It was a crossover hit on both pop and R&B charts and made Ray Charles famous.

Atlantic allowed Ray an unusual amount of artistic freedom to bring what he wanted to the studio. He was still recording jazz and blues sides as well as R&B singles in the mode of "I Got a Woman. In 1957, searching for a fuller, more choir-like sound, Ray added female back-up singers to his records and touring, naming them The Raelettes. He continued to conquer the charts with songs like "A Fool for You," "Drown In My Own Tears," "Hallelujah I Love Her So," "The Right Time, and "Lonely Avenue." His foray into the pop charts occurred with "What'd I Say, an infectious number that opened with a sprightly electric piano line and caught fire like a Jerry Lee Lewis rock n' roll number, complete with pleading back-up vocals from the Raelettes.

Feeling the need to expand his sound again Ray went into the studio in 1959 and recorded with the accompaniment of strings and a big band. Six of the tracks were arranged by his old friend Quincy Jones and included veteran Count Basie and Duke Ellington sidemen. Another six tracks were orchestrated ballads. The resulting album would aptly be named The Genius of Ray Charles and enhanced Ray's reputation even wider.

Sensing a need for a new musical strategy Ray left Atlantic Records for ABC-Paramount shortly thereafter. He continued his amazing parade of hits well into the 60s and also mastered other genres like pop, country music and soundtracks, always soulfully making them his own. Ray Charles' genius came in many forms.

http://www.britannica.com/biography/Ray-Charles

Ray Charles

American Musician

Also known as

Ray Charles Robinson

the Genius

Ray Charles

American Musician

Also known as

Ray Charles Robinson

the Genius

born: September 23, 1930

Albany, Georgia

died: June 10, 2004

Beverly Hills, California

Albany, Georgia

died: June 10, 2004

Beverly Hills, California

Ray Charles, original name Ray Charles Robinson (born Sept. 23, 1930, Albany, Ga., U.S.—died June 10, 2004, Beverly Hills, Calif.), American pianist, singer, composer, and bandleader, a leading black entertainer billed as “the Genius.” Charles was credited with the early development of soul music, a style based on a melding of gospel, rhythm and blues, and jazz music.

When Charles was an infant his family moved to Greenville, Fla., and he began his musical career at age five on a piano in a neighbourhood café. He began to go blind at six, possibly from glaucoma, and had completely lost his sight by age seven. He attended the St. Augustine School for the Deaf and Blind, where he concentrated on musical studies, but left school at age 15 to play the piano professionally after his mother died from cancer (his father had died when the boy was 10).

Charles built a remarkable career based on the immediacy of emotion in his performances. After emerging as a blues and jazz pianist indebted to Nat King Cole’s style in the late 1940s, Charles recorded the boogie-woogie classic “Mess Around” and the novelty song “It Should’ve Been Me” in 1952–53. His arrangement for Guitar Slim’s “The Things That I Used to Do” became a blues million-seller in 1953. By 1954 Charles had created a successful combination of blues and gospel influences and signed on with Atlantic Records. Propelled by Charles’s distinctive raspy voice, “I’ve Got a Woman” and “Hallelujah I Love You So” became hit records. “What’d I Say” led the rhythm and blues sales charts in 1959 and was Charles’s own first million-seller.

Charles’s rhythmic piano playing and band arranging revived the “funky” quality of jazz, but he also recorded in many other musical genres. He entered the pop market with the best-sellers “Georgia on My Mind” (1960) and “Hit the Road, Jack” (1961). His album Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music (1962) sold more than a million copies, as did its single “I Can’t Stop Loving You.” Thereafter his music emphasized jazz standards and renditions of pop and show tunes.

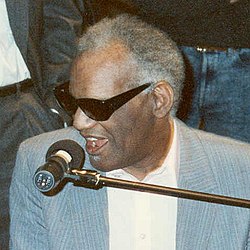

Ray Charles [Credit: AP]

From 1955 Charles toured extensively in the United States and elsewhere with his own big band and a gospel-style female backup quartet called the Raeletts. He also appeared on television and worked in films such as Ballad in Blue (1964) and The Blues Brothers (1980) as a featured act and sound track composer. He formed his own custom recording labels, Tangerine in 1962 and Crossover Records in 1973. The recipient of many national and international awards, he received 13 Grammy Awards, including a lifetime achievement award in 1987. In 1986 Charles was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and received a Kennedy Center Honor. He published an autobiography, Brother Ray, Ray Charles’ Own Story (1978), written with David Ritz.

http://rockhall.com/inductees/ray-charles/bio/

Ray Charles Biography

Ray Charles (vocals, piano; born September 23, 1930, died June 10, 2004)Many musicians possess elements of genius, but only one — the great Ray Charles — so completely embodied the term that it was bestowed upon him as a nickname. Charles displayed his genius by combining elements of gospel and blues into a fervid, exuberant style that would come to be known as soul music. While recording for Atlantic Records during the Fifties, the innovative singer, pianist and bandleader broke down the barriers between sacred and secular music. The gospel sound he’d heard growing up in the church found its way into the music he made as an adult. In his own words, he fostered “a crossover between gospel music and the rhythm patterns of the blues.” But he didn’t stop there: over the decades, elements of country & western and big-band jazz infused his music as well. He is as complete and well-rounded a musical talent as this century has produced.

Born in Albany, Georgia, on September 23, 1930, Charles was raised in Greenville, Florida, where he made the acquaintance of a piano-playing neighbor. As a youngster, Charles apprenticed with him at his small store-cum-juke joint while digesting the blues, boogie-woogie and big-band swing records on his jukebox. At age six, he contracted glaucoma, which eventually left him blind. Charles studied composition and mastered a variety of instruments, piano and saxophone principal among them, during nine years spent at the St. Augustine School for the Deaf and the Blind. Thereafter, he played around Florida in a variety of bands and then headed for the West Coast, where he led a jazz-blues trio that performed in the polished style of Nat “King” Cole and Charles Brown. After cutting singles for labels such as Downbeat and Swingtime, Charles wound up on Atlantic Records in 1952. It turned out to be an ideal match between artist and label, as both were just beginning to find their feet.

Given artistic control at Atlantic after demonstrating his knack as an arranger with Guitar Slim’s “Things That I Used to Do” — the biggest R&B hit of 1954 — Charles responded with a string of recordings in which he truly found his voice. This extended hit streak, which carried him through the end of the decade, included such unbridled R&B milestones as “I Got a Woman,” “Hallelujah I Love Her So,” “Drown in My Own Tears” and the feverish call-and-response classic “What’d I Say.” All were sung in Charles’ gruff, soulful voice and accompanied by the percussive punctuations of his piano and a horn section. After his groundbreaking Atlantic years, Charles moved to ABC/Paramount, where he claimed the unlikeliest of genres as his own with Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music, an album that topped the Billboard chart for 14 weeks in 1962.

Throughout his career, Charles never stopped pursuing that uncategorizable blend of idioms that is best described with a single word: soul. And just what is soul, according to Ray Charles? As he told Time magazine in 1968: “It’s a force that can light a room. The force radiates from a sense of selfhood, a sense of knowing where you’ve been and what it means. Soul is a way of life – but it’s always the hard way." Charles remained active as a performer and recording artist right up to his death from liver disease on June 10, 2004 at age 73.

November 19, 1990

Vol. 34 No. 20

Ray Charles

by David Grogan

PEOPLE

Vol. 34 No. 20

Ray Charles

by David Grogan

PEOPLE

At 60, the Granddaddy of Soul Just Keeps Rolling Out the Good Times for New Generations of Toe-Tapping, Table-Slapping Fans

The Genius of Soul is a bit cranky tonight. With showtime approaching for his 11:30 P.M. set at New York City's Blue Note, brother Ray Charles is slumped in a dressing room chair, moody and wrapped in silence. Minutes pass. Then Charles, blind since childhood, turns slowly toward a darkened window. In a whisper-soft voice he begins to sing, not a blues or a country ballad, but an old, sentimental World War II song: "When the lights go on again, all over the world..."

The moment ends. It is showtime now, and soon Charles is standing onstage in the warmth of bright lights and a packed house. While his 15-piece brass band roars behind him, he starts to rabbit-hop in time with the music, then wraps his arms around his shoulders in a symbolic embrace of the audience. For the next hour he stays in perpetual motion, swaying to fast tunes behind his electric piano like a funk-beat metronome. The tempo slows as he gently caresses the melody of his signature ballad, "Georgia on My Mind." And when the Raeletts, his five-woman chorus, join the band for a bone-rattling "What I Say," Charles's infectious glee spreads through the $50-a-ticket crowd.

"My mama taught me to give my all to a job, no matter what," he says later, still pumped with excitement backstage. "You've just got to do it and not complain. You never know how much time you have left in the world."

Ray Charles turned 60 recently, and the man who invented soul nearly four decades ago is still making every moment count. Earlier this year, his duet with Chaka Khan titled "I'll Be Good to You," from Quincy Jones's Back on the Block album, topped the Billboard Hot Black Singles chart. His latest album, Would You Believe?, released just last month, was finished in time to free Charles for a six-week tour of the Far East and Europe with guitarist B.B. King, pianist Gene Harris and the 17-piece Philip Morris Super-band. Meanwhile, he is a ubiquitous presence on television as the star of a Diet Pepsi ad campaign.

Years ago Frank Sinatra called Charles "the only genius in the business." Ray doesn't put much stock in such praise. "I'll get all the accolades," he shrugs, "but at my best I will never make half the money that Sinatra has made. It's not going to happen. But when you break it down, what does it matter? I can only sleep in one bed at a time. I can only make love to one woman at a time."

A notorious ladies' man, Charles has sired nine children, ages 14 to 40, with seven different women, and has seven grandchildren. "All my kids know me," he says proudly. Vowing to remain single after two failed attempts at marriage, Charles is a restless spirit, often subject to mercurial moods. When he is down, there is no approaching him. When he is happy, there is no resisting him.

As he starts his seventh decade, Charles still spends most of his days on the road, traveling nine months each year. Chess, a game he discovered while kicking a heroin habit in 1965, is his primary passion between shows. For Charles, it is a game of touch as well as tactics, and he uses a specially designed board with raised black squares and pegged pieces, his fingers a blur as he surveys the field. His play is defensive. "He sets little traps and sits and waits for you to fall for them," says Vernon Troupe, 50, his valet and constant companion. "Then he pounces."

Charles is just as exacting in real life. "I truly love Mr. C., but working for him is not easy," says Troupe. "If his tuxedos are not pressed a certain way or his food is not just so, somebody has to know the reason why. And if he says he'll be ready at 10 o'clock, he means 10, not one minute before or after."

Off the road, Charles returns to a sparsely furnished apartment in Beverly Hills and doesn't socialize much. "If you get more than three or four people around me, you've got a crowd," he says. A windowless office complex near downtown L.A. is headquarters for his personal manager, Joe Adams, and houses a private recording studio, which Charles considers his real home.

Inviting a guest into this sanctum recently, Charles had to be reminded to turn on the light. He was cautious and reserved at first when asked to talk about himself. Soon, however, he pranced and preached as he recalled his country upbringing in Greenville, Fla.

Christened Ray Charles Robinson (he later dropped the surname to avoid confusion with boxer Sugar Ray Robinson), he was the son of Bailey Robinson, a railroad repairman who was seldom around and never married Ray's mother, 'Retha. She took in washing and ironing to support her two children and shared child raising with Bailey's legal wife, Mary Jane. "Mary Jane had a child of her own but he died, so she took a liking to me," Charles says. "With Mary Jane I couldn't do wrong. I was her pet. But my mother made sure I did right."

Despite the decades that have passed, Charles still talks of his joy on those nights when he would awake to a full moon in the sky before his world went black. "Other nights I'd wake up and it would be pitch dark," he says. "So I'd go out with a big flashlight and light up the world."

On Sundays he sang at the Shiloh Baptist Church, but there was other music as well—at the Red Wing Café where the proprietor, Wylie Pitman, kept the jukebox stocked with records by Muddy Waters, Blind Boy Phillips and Tampa Red. "Mr. Pit also had a piano," says Charles. "As a little kid I'd go in and start banging on it, and the man could have easily shooed me away. Instead he'd take my fingers, one by one, and show me a little melody."

When he was 5, the bright and simple days began to end. Ray was playing in the backyard one afternoon when he saw his 3½-year-old brother, George, topple into a washtub. "He must have dropped something in the water and keeled over trying to get it," he says. "I tried to pull him out, but he was too heavy. I went into the house to get my mom, but it was too late."

A few months later, Charles's eyes started tearing and his sight gradually slipped away, stolen by a disease his country doctor could not name, let alone cure. Within two years he was totally blind. "People couldn't understand why my mama would have this blind kid out doing things like cutting wood for the fire," he says now. "But she had the foresight to go against the grain in this little town. Her thing was: 'He may be blind, but he ain't stupid.' That's why I brag on my mama today."

For the next eight years he boarded at a state school for the blind in St. Augustine, Fla., where he studied classical music and played blues and boogie in his spare time. Then his mother died suddenly, apparently a victim of food poisoning. Lost and alone, Ray lay motionless for a week following her funeral before finally breaking into tears.

He was just 15, but he decided to set out on his own and to try to earn his way as a pianist. "I had to leave Greenville because there was nothing I could do," he says simply. "And I wasn't about to be begging nobody because I wasn't raised that way. My mom would have died 15 deaths if I did that."

Instead he traveled through Florida playing in pickup bands and living on sardines and beans. "I didn't have somebody looking out for me 24 hours," he says. "You understand what I'm saying? I had to walk around by my goddamn self if I wanted to go." Finally, he asked a friend to take a map of the United States and locate a big city as far away as possible from Tampa. Within days he was rumbling toward Seattle by bus. "I didn't know anything about the town," he says. "But I figured it had to be a place where at least I'd have a better chance."

A few months short of 18 when he arrived, he entered a talent contest his first night in town and was immediately offered a job playing at a local Elks club. After several months, he caught the ear of a record producer and cut his first single, "Confession Blues." As his reputation grew, Charles became the idol of a teenage trumpet player with considerable gifts of his own. "Ray's apartment was the place to be because he had his own record player," says Quincy Jones, Ray's best friend still. "He used to take it apart and get shocked and stuff. He was just curious about everything."

During the next few years Charles lived on the road, making the rounds of black honky-tonks and beer halls around the country. Musicians called it the chitlin' circuit. "People didn't sit on their asses," Charles says. "They came to dance. If somebody got too close to somebody else's woman, it was nothing to have a fight break out and bottles start flying." For a long time he was content to copy the style of such established stars as Nat King Cole. People praised his mimicry, "and I thought it was great," he says. "But as I was shaving one morning, I thought, 'Who knows your name?' "

Soon he began combining gospel styling with down-and-dirty lyrics and horn riffs, and folks everywhere came to know who he was. "The black church is the ultimate source of American music," says Quincy Jones. "Ray got the mothership together with its grandbabies, blues and jazz, and touched the world." In the process he created a new genre of music; it came to be called soul, and at first "some people said it was sacrilegious," Charles says. "But it was me. And most people loved it."

In the '60s he went further, turning tired country standards like "I Can't Stop Loving You" into pop hits by embellishing them with lush orchestral arrangements and his own plaintive vocals. Critics were confounded by his landmark LP, Modern Sounds in Country & Western Music. But Charles had listened to Grand Ole Opry every Saturday as a kid and was only doing what felt natural.

Unfortunately that wasn't all that he did; in the late '40s he had begun a heroin habit that he didn't break for 17 years. Despite the damage it eventually did to his reputation, he still refuses to be cast in the role of repentant sinner. "There wasn't nobody around saying, 'Hey, man, you want to get high, Ray?' I did drugs because it was my pleasure," he says. "Still, I never wanted to be so ossified I wasn't aware of what was going on around me. Being blind stopped me from that."

In 1964 Charles was busted for heroin possession at Boston's Logan Airport. While awaiting trial, he headed to California where, after attending a Little League banquet with his second wife, Della, and their 9-year-old son, Ray Jr., he began sizing up his future. "Before he got his little award, I had to leave for a recording session," Charles says. "So he started to cry. And I'm thinking, 'Now what's going to happen if somebody comes out and calls his daddy a jailbird or a drug addict?' That's when I decided I was through with drugs." He checked himself into a hospital and went cold turkey. After random testing for a year proved he was clean, the drug rap against him in Boston was dropped.

"Ray was always a good provider and loving father," says Della, now 61. Despite their 1977 divorce, Della still treats Charles to pound cake and homemade ice cream every year on his birthday and bears him no ill will. "People see his guarded side." says Della. "But you have to remember the people he loved the most as a child—his brother and his mother—were taken away from him. That's why he's cautious about letting people get too close." Ray Jr., now 35, has become more intimate with his dad recently since Charles hired him to oversee plans for a feature movie about his life. "I used to be intimidated by my father," says Ray Jr. "He is not a patient man. But he is teaching me a lot about discipline."

Patience is in short supply for Charles as he rehearses with the Philip Morris Super-band in New York two days before going on tour. Song after song, he has been scolding the musicians like a schoolmaster, sometimes cursing under his breath. "It don't matter how it's written, honey," he says when one band member complains about his illegible sheet music, "because I'm here to tell you for myself."

The next day his fellow headliner, blues guitarist B.B. King, jokes about a time he provoked Ray's ire in the studio a couple of years ago. "Ray said, 'Now B.B., you a musician and a singer. Can't you hear?' " King recalls. "But you know, Ray is right every time he tells you something."

Charles's own sharp hearing is legendary among his fellow musicians, but the gift was temporarily affected four years ago by an inner-ear infection that gave him the fright of his life. "It would be a real bitch if I ever lost my hearing," he says. "I know I couldn't be no Helen Keller. I think that would be worse than death."

Only slightly less terrifying, it seems, is the thought of retirement. "I don't want to retire to nothing," he says firmly, leaving no question. And so he works and plays and continues on, lending his voice and soul to yet one more generation. He will tour South America and Japan with his own band before the end of the year and has long-range plans to do an all-star recording session that will include jazz greats Dizzy Gillespie and Milt Jackson. "I figure you do what you can, while you can, on this earth, because you can bet your ass you're gonna leave here," he says. "Ain't no doubt about that."

Ray Charles Issue 1995

If you're looking for Ray Charles on an evening where he plays two 55 minute shows, you can probably find him in one of two places: seated in front of a piano or chessboard, In fact, the trim, 5'9" legendary "Genius of Soul" feels at home in front of either board, regardless of how many people are watching. Most people can picture Ray with his black sunglasses and captivating smile sitting in front of a piano, yet the image of this blind musician looking with his hands at a chess board may raise a few questions. Like, how?

If you're looking for Ray Charles on an evening where he plays two 55 minute shows, you can probably find him in one of two places: seated in front of a piano or chessboard, In fact, the trim, 5'9" legendary "Genius of Soul" feels at home in front of either board, regardless of how many people are watching. Most people can picture Ray with his black sunglasses and captivating smile sitting in front of a piano, yet the image of this blind musician looking with his hands at a chess board may raise a few questions. Like, how?

In a game where skill and determination weed out the more proficient players, chess can be easily adapted to the needs of the visually impaired. For instance, Ray plays on a board where each square is the same color but the depth of the squares are altered-- the "black" squares are raised while the "white" squares are lowered. In addition, the black pieces may have sharper tops, whereas the white ones are flat, and all pieces include a peg on the bottom that fit into any hole drilled into the squares on the board. In order to make the game a bit more user-friendly, you will probably hear Ray Charles and his partner calling out moves as the game progresses, making this type of chess a louder, more interactive experience.

Ray has managed to recruit a few of his band members, friends, and even interviewers to play a chess game in between gigs on tour. As he sips warm coffee with Bols gin, he is comfortably removed from long months on the road promoting his latest album.

Brother Ray, as he is affectionately called, has certainly put his time in on the road. In his musical career of over 47 years, Ray has successfully mastered the blues, jazz, gospel, rock, pop, and country music continually airing his soulful heart. He has teamed up with the best of the best in each stylistic genre, including BB King, Aretha Franklin, Lou Rawls, Hank Williams, Willie Nelson, Stevie Wonder, and, most recently, Eric Clapton. Ray prefers not to describe himself as a specific kind of singer, just a musician. "I'm not a country singer. I'm a singer who sings country songs. I'm not a blues singer, but I can sing the blues. I'm not really a crooner, but I can sing love songs. I'm not a specialist, but I'm a pretty good utility man. I can play first base, second base, shortstop. I can catch and maybe even pitch a little."

Whether it be the blues king or the granddaddy of soul, you get the distinct feeling that Ray is singing what he knows. "His style of singing is born out of his style of talking," explains David Ritz, coauthor of Ray's autobiography, Brother Ray. "There are two moods which he exibits: extreme highs and extreme lows...When he is excited, he is an obsessive and poetic talker; he will chew your ear off until you are exhausted and beat. When he is down, he becomes non-verbal-- his responses are monosyllabic...Both moods are strong, and his sullen look will grip him as suddenly as his smile." But his wry sense of humor is enduring-- and endearing. Once, when booked into a glamorous Las Vegas hotel suite with a bed two steps up, he said: "You know, I think these people are trying to kill me." On the ceiling, above the bed, was a mirror. "Oh great!" he shot back when informed of the extra.

Ray Charles Robinsons' autobiography, Brother Ray, details Ray's life, which began on September 23, 1930, in Albany, Georgia. He recounts his days as a country boy in Greenville, Florida (about 30 miles from the Georgia boarder) as the older of two boys cared for by his biological mother, OERetha, whom he called "Mama." OERetha and the boys treated one of his father's first wives, Mary Jane, like family, and Ray was known to refer to her as "Mother." Mary Jane lived nearby and occasionally cared for the boys as if they were her own. His father, Bailey Robinson, was rarely seen by Ray or his brother George. Bailey worked driving spikes on the railroad crossities in Florida and Georgia, hardly ever coming around to see the family. It was OERetha who brought home whatever pennies she could, doing chores for the local people in the neighborhood.

Ray speaks highly of his mama. To this day, he can clearly describe her looks and continues to praise her wisdom, love, and discipline. His experiences as a child were of complete love and acceptance, mixed with periods of loss and suffering. Early childhood memories include adventures in the colorful country with his brother George, and Sundays at the local Baptist Church-- Ray's first introduction to religion and music. And then he'll recall watching his four-year-old brother George accidentally drown in a washtub as he desperately tried to pull him out. Ray was only five then, and the most he could manage to do was scream for his mama to help.

Up until he was about six, Ray's vision was normal. Over a period of time, images began to blur and he would spend five or ten minutes each morning wiping the mucas from his eyes as they adjusted to the light. During that year, OERetha has taken him to numerous doctors in the area, all of which concluded that Ray would be blind and there was nothing to be done about it. By the age of seven, with his mama's insistence, he reluctantly left home for a state-supported boarding school-- the nearest one being St. Augustine's for the blind and deaf, 160 miles away from home.

"Mama was a country woman with a whole lot of common sense. She understood what most of our neighbor's didn't-- that I shouldn't grow dependent on anyone except myself," Ray explains. "OEOne of these days, I ain't gonna be here,' she kept hammering inside my head. Meanwhile, she had me scrub floors, chop wood, wash clothes, and play outside like all the other kids...And her discipline didn't stop just OEcause I was blind. She wasn't about to let me get away with any foolishness."

Ray's new school separated the deaf from the blind, the black from the white, and the boys from the girls from ages six through eighteen. "It's awfully strange thinking about separating small children-- black from white-- when most of OEem can't even make out the difference between the two colors," Ray said.

It was a tough move for him to be so far from home at the time and he openly admits his crying. "I suppose I've always done my share of crying, especially when there's no other way to contain my feelings. I know that men ain't supposed to cry, but I think that's wrong. Crying's always been a way for me to get things out which are buried deep, deep down. When I sing, I often cry. Crying is feeling and feeling is being human. Oh yes, I cry."

He learned Braille and eventually sign language so the deaf kids could "speak" to him in the palms of his hands as he read their lips. It wasn't long before he was able to read books and work with his hands weaving and carving. The second part of the school year, Ray was taken to the hospital to have his right eye removed. It had been aching him badly, throbbing from morning to night. To this day, doctors can only speculate as to what the problem was, some saying perhaps glaucoma.

Brother Ray was always into music, whether it was pounding on Mr. Wylie Pittman's piano in the neighborhood store or simply listening to the jukebox. It was no surprise that his favorite subject in school was music instruction, which he started at the age of eight. The formal instruction began with exercises and classical pieces on the piano and, two years later, on the clarinet.

Being constantly attracted, and distracted, by music of all sorts, Ray discovered a variety of role models and musical styles. His keen sense of hearing and rhythm enabled him to pick up not only the instruments and melodies, but the arrangements how the horns, the reeds, and the rhythm were arranged in different sections. During the early forties, Ray was listening to the big bands with the rest of America, along with the middy Mississippi blues that were only avaiable on "race records." Determined and strong-willed, Ray would always find some way to sneak into the practice rooms at school after hours to practce.

Ray Charles' mama warned him over and over again that one day, she wouldn't be around, but nothing prepared Ray for the time when she passed away. He was only fifteen when he had to return home from school for his mother's funeral.

"When a boy has just one parent a mama he'll cling to her like she's life itself," expresses Charles in Brother Ray. "And he'll never even start thinking about what life would be like without her. The thought's too terrible...I was unable to deal with the facts of death; I was unable to accept the reality of death."

After his brother George had died, there was just mama. Now he was alone. "I had to make up my own mind, my own way, in my own time," explained Ray. "Never really had to do that before, and in many ways, I found the situation frightening. But that week of silence and suffering also made me harder, and that hardness has stayed with me the rest of my life."

Shortly thereafter, Ray dropped out of high school and moved to Jacksonville, Florida. His intention in scuffling through Jacksonville was to get some live musical experience in the big city. Ray responded to his new surroundings by seeking out any piano he could find. "it was music which drove me; it was my greatest pleasure and my greatest release. It was how I expressed myself."

It was about this time Ray Charles Robinson ended up shortening his name, so he wouldn't be confused with "Sugar Ray" Robinson, the popular boxer of the time. Staying downtown with some friends of Mary Jane, Ray would jam at any gig he could get. He would manage to memorize his way around town, paying little attention to things like drainage pipes, sewers, or cracks in the sidewalk.

Ray was always pretty courageous. When he was ten or eleven, he rode a bicycle on practucally every dirt road and path in Greenville. During a summer in Tallahassee, the fifteeen-year-old daredevil learned how to ride a motorcycle. He loved the feeling of motion and just like getting around Jacksonvile or any other town, "being blind wasn't gonna stop me...somewhere in the back of my mind, I knew I wasn't going to hurt myselfI always had a lot of faith in my ability not to break my neck." Ray's hearing is exceptional, and his instincts are sharp. "I suppose that one proof of the rightness of my attitude is that as a kid, I was never seriously hurt and there were only a few close calls," he comments.

Ray's acute hearing proved to be quite an asset to his career as well. Though the ability to sing, play, write music and network his way around the clubs barely put food on the table at first, nothing could contain Ray's passion for music. After Jacksonville, it was Orlando, then Seattle, and by 1948, his first album was released. At the time, Ray Charles was most influenced by his idols, Nat Cole and Charles Brown. Ray recalls, "But as I was shaving one morning, I thought, OEWho knows your name?'" Gradually, his own style developed.

It wasn't long before Ray Charles was forging the gospel with the blues. His earliest tangible result of that was "I Got a Woman" for Ahmet Ertegun and Atlantic Records in 1954. Record producer Jerry Wexler described Brother Ray's voice then: "The emerging sound was unmistakable, brand-new, yet ancient as the woods, the country church of Ray's childhood. The breakthrough was close at hand."

And so began the "Genius of Soul," a hybrid sound that introduces God's voice to man's feelings, which certainly raised a few eyebrows for a while. Ray continued to experiment with his new style. Big bands, small bands, solo, and a variety of backup choruses have spotted his long career. He has also been fortunate enough to work without interference from record companies through the years and be able to choose his own songs.

"I am very into lyrics," Ray explains. "I start with what the words are saying, what the storyline is saying, like a good script. It should really capture me, do something for me. If I don't get it, it's not going to move people, and if it's not going to move people, it's not going to happen. I don't think I'm good because I'm blind, I think I'm good because I'm good."

At one point, stage manager Carl Hunter explained that "he'd [Charles] know it if the band missed a note, a single note. He'd know it if the drummer's left shoelace was flapping. You be with us long enough, you'll swear the man can see." In a performance, Ray's body moves to a different part of the music, but his feet provide the most deft, airbone accompaniment. It's his feet that give the backbeat, the downbeat, the accents, and the tempo; it's the way Ray conducts. In fact, this way of conducting is so powerful that "in rehearsal, if you walk between the band and his feet, they all start cursing you," said Carl.

Ray's publicist, Bob Abrams, says, "You know you're getting a good show when Ray's socks fall down...his feet are going up over the piano. One sock falls half-mast. It's because of all the energy he expands. That's his exercise."

Brother Ray's latest album/CD, "My World," is yet another example of his timeless musical talent. His mix of socially conscious songs with pop standards display a very contemporary side of Ray. There are songs about concern for families and children, as well as peace and unity on the planet.

"Music is powerful," Ray says. "As people listen to it, they can be affected. They respond. But when I was doing this album, I wasn't trying to create an overall message. It just turned out that we got some songs that had something to say." And Ray, along with his all-star cast for some of his songs (like Billy Preston, Mavis Staples, and Eric Clapton), continues his musical experiments this time using synthesizers, sound samplers, and drum machines.

This open attitude keeps Ray current with his fans. During the 1980's and 90's, he caught the attention of a whole new generation with his popular "California Raisin" and Pepsi ("Uh huh") commercials. In fact, the first Diet Pepsi commercial in the fall of 1990 proved to be so unexpectedly popular that Ray Charles is taking home an estimated $3 million from Pepsi after renegotiating his original one-year contract. And for those that missed it, photo "opportunities" were available with life-size cutout figures of Ray Charles and the Raeletts at selected supermarkets last year.

"I must say, I'm proud of that commercial," explains Ray, in his fifth year as spokesperson for Pepsi.

And what about those three sexy background singers dubbed the Reaeletts? Well, Ray has never been one to hold back with women. Next to music, women have always been the major objects of his attention. In Brother Ray, he tells us that no day is worth starting without a love, and many of his songs have been regarded as a sort of report of his fortunes and misfortunes with women.

Battling substance abuse for a number of years, Ray finally enrolled in the rehabiltation program at St. Francis hospital near Los Angeles in 1965. His decision to go cold turkey is an example of his committment to himself, and after overcoming his physical and psychological addiction in his own way, he left the hospital. It was at St. Francis that Ray learned how to play chess and continued to play cards in Braille.

Ray's most recent bout with pain was a serious maddening of inner-ear problems. "I was hearing sound within sounds," he says. For a man that relies so heavily on his hearing, this proved to be quite a scare. Although his problems have since been resolved, Ray felt motivated enough to become involved with groups like Ear International, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit organization for the hearing disabled. His personal donations and fund raising have provided money for research in developing electronic implants, among other devices.

In futhering his dedication to the hearing impaired, Ray urged Congress to increase funding for research into hearing loss in 1987. His visit to Washington, D.C. included speaking before the subcommittees for Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, saying: "Most people take their hearing for granted. I can't. My eyes are my handicap, but my ears are my opportunity. My ears show me what my eyes can't. My ears tell me 99 percent of what I need to know about my world."

In addition to working with Ear International, Ray Charles has shown a long and active concern and involvement with sickle cell disease programs. In 1975, the National Association for Sickle Cell Disease (NASCD) presented their first "Man of Distinction" Award to Ray, and he continues as the L.A. chapter's Honorary Chairman since 1962.

What's next for this multi-talented entertainer? Well, as Ray himself articulates, "music is nothing separate from me. It is me. I can't retire from music any more than I can retire from my liver...I believe the Lord will retire me when He's ready. And then I'll have plenty of time for a long vacation."

Ray has managed to recruit a few of his band members, friends, and even interviewers to play a chess game in between gigs on tour. As he sips warm coffee with Bols gin, he is comfortably removed from long months on the road promoting his latest album.

Brother Ray, as he is affectionately called, has certainly put his time in on the road. In his musical career of over 47 years, Ray has successfully mastered the blues, jazz, gospel, rock, pop, and country music continually airing his soulful heart. He has teamed up with the best of the best in each stylistic genre, including BB King, Aretha Franklin, Lou Rawls, Hank Williams, Willie Nelson, Stevie Wonder, and, most recently, Eric Clapton. Ray prefers not to describe himself as a specific kind of singer, just a musician. "I'm not a country singer. I'm a singer who sings country songs. I'm not a blues singer, but I can sing the blues. I'm not really a crooner, but I can sing love songs. I'm not a specialist, but I'm a pretty good utility man. I can play first base, second base, shortstop. I can catch and maybe even pitch a little."

Whether it be the blues king or the granddaddy of soul, you get the distinct feeling that Ray is singing what he knows. "His style of singing is born out of his style of talking," explains David Ritz, coauthor of Ray's autobiography, Brother Ray. "There are two moods which he exibits: extreme highs and extreme lows...When he is excited, he is an obsessive and poetic talker; he will chew your ear off until you are exhausted and beat. When he is down, he becomes non-verbal-- his responses are monosyllabic...Both moods are strong, and his sullen look will grip him as suddenly as his smile." But his wry sense of humor is enduring-- and endearing. Once, when booked into a glamorous Las Vegas hotel suite with a bed two steps up, he said: "You know, I think these people are trying to kill me." On the ceiling, above the bed, was a mirror. "Oh great!" he shot back when informed of the extra.

Ray Charles Robinsons' autobiography, Brother Ray, details Ray's life, which began on September 23, 1930, in Albany, Georgia. He recounts his days as a country boy in Greenville, Florida (about 30 miles from the Georgia boarder) as the older of two boys cared for by his biological mother, OERetha, whom he called "Mama." OERetha and the boys treated one of his father's first wives, Mary Jane, like family, and Ray was known to refer to her as "Mother." Mary Jane lived nearby and occasionally cared for the boys as if they were her own. His father, Bailey Robinson, was rarely seen by Ray or his brother George. Bailey worked driving spikes on the railroad crossities in Florida and Georgia, hardly ever coming around to see the family. It was OERetha who brought home whatever pennies she could, doing chores for the local people in the neighborhood.

Ray speaks highly of his mama. To this day, he can clearly describe her looks and continues to praise her wisdom, love, and discipline. His experiences as a child were of complete love and acceptance, mixed with periods of loss and suffering. Early childhood memories include adventures in the colorful country with his brother George, and Sundays at the local Baptist Church-- Ray's first introduction to religion and music. And then he'll recall watching his four-year-old brother George accidentally drown in a washtub as he desperately tried to pull him out. Ray was only five then, and the most he could manage to do was scream for his mama to help.

Up until he was about six, Ray's vision was normal. Over a period of time, images began to blur and he would spend five or ten minutes each morning wiping the mucas from his eyes as they adjusted to the light. During that year, OERetha has taken him to numerous doctors in the area, all of which concluded that Ray would be blind and there was nothing to be done about it. By the age of seven, with his mama's insistence, he reluctantly left home for a state-supported boarding school-- the nearest one being St. Augustine's for the blind and deaf, 160 miles away from home.

"Mama was a country woman with a whole lot of common sense. She understood what most of our neighbor's didn't-- that I shouldn't grow dependent on anyone except myself," Ray explains. "OEOne of these days, I ain't gonna be here,' she kept hammering inside my head. Meanwhile, she had me scrub floors, chop wood, wash clothes, and play outside like all the other kids...And her discipline didn't stop just OEcause I was blind. She wasn't about to let me get away with any foolishness."

Ray's new school separated the deaf from the blind, the black from the white, and the boys from the girls from ages six through eighteen. "It's awfully strange thinking about separating small children-- black from white-- when most of OEem can't even make out the difference between the two colors," Ray said.

It was a tough move for him to be so far from home at the time and he openly admits his crying. "I suppose I've always done my share of crying, especially when there's no other way to contain my feelings. I know that men ain't supposed to cry, but I think that's wrong. Crying's always been a way for me to get things out which are buried deep, deep down. When I sing, I often cry. Crying is feeling and feeling is being human. Oh yes, I cry."

He learned Braille and eventually sign language so the deaf kids could "speak" to him in the palms of his hands as he read their lips. It wasn't long before he was able to read books and work with his hands weaving and carving. The second part of the school year, Ray was taken to the hospital to have his right eye removed. It had been aching him badly, throbbing from morning to night. To this day, doctors can only speculate as to what the problem was, some saying perhaps glaucoma.

Brother Ray was always into music, whether it was pounding on Mr. Wylie Pittman's piano in the neighborhood store or simply listening to the jukebox. It was no surprise that his favorite subject in school was music instruction, which he started at the age of eight. The formal instruction began with exercises and classical pieces on the piano and, two years later, on the clarinet.

Being constantly attracted, and distracted, by music of all sorts, Ray discovered a variety of role models and musical styles. His keen sense of hearing and rhythm enabled him to pick up not only the instruments and melodies, but the arrangements how the horns, the reeds, and the rhythm were arranged in different sections. During the early forties, Ray was listening to the big bands with the rest of America, along with the middy Mississippi blues that were only avaiable on "race records." Determined and strong-willed, Ray would always find some way to sneak into the practice rooms at school after hours to practce.

Ray Charles' mama warned him over and over again that one day, she wouldn't be around, but nothing prepared Ray for the time when she passed away. He was only fifteen when he had to return home from school for his mother's funeral.

"When a boy has just one parent a mama he'll cling to her like she's life itself," expresses Charles in Brother Ray. "And he'll never even start thinking about what life would be like without her. The thought's too terrible...I was unable to deal with the facts of death; I was unable to accept the reality of death."

After his brother George had died, there was just mama. Now he was alone. "I had to make up my own mind, my own way, in my own time," explained Ray. "Never really had to do that before, and in many ways, I found the situation frightening. But that week of silence and suffering also made me harder, and that hardness has stayed with me the rest of my life."

Shortly thereafter, Ray dropped out of high school and moved to Jacksonville, Florida. His intention in scuffling through Jacksonville was to get some live musical experience in the big city. Ray responded to his new surroundings by seeking out any piano he could find. "it was music which drove me; it was my greatest pleasure and my greatest release. It was how I expressed myself."

It was about this time Ray Charles Robinson ended up shortening his name, so he wouldn't be confused with "Sugar Ray" Robinson, the popular boxer of the time. Staying downtown with some friends of Mary Jane, Ray would jam at any gig he could get. He would manage to memorize his way around town, paying little attention to things like drainage pipes, sewers, or cracks in the sidewalk.

Ray was always pretty courageous. When he was ten or eleven, he rode a bicycle on practucally every dirt road and path in Greenville. During a summer in Tallahassee, the fifteeen-year-old daredevil learned how to ride a motorcycle. He loved the feeling of motion and just like getting around Jacksonvile or any other town, "being blind wasn't gonna stop me...somewhere in the back of my mind, I knew I wasn't going to hurt myselfI always had a lot of faith in my ability not to break my neck." Ray's hearing is exceptional, and his instincts are sharp. "I suppose that one proof of the rightness of my attitude is that as a kid, I was never seriously hurt and there were only a few close calls," he comments.

Ray's acute hearing proved to be quite an asset to his career as well. Though the ability to sing, play, write music and network his way around the clubs barely put food on the table at first, nothing could contain Ray's passion for music. After Jacksonville, it was Orlando, then Seattle, and by 1948, his first album was released. At the time, Ray Charles was most influenced by his idols, Nat Cole and Charles Brown. Ray recalls, "But as I was shaving one morning, I thought, OEWho knows your name?'" Gradually, his own style developed.

It wasn't long before Ray Charles was forging the gospel with the blues. His earliest tangible result of that was "I Got a Woman" for Ahmet Ertegun and Atlantic Records in 1954. Record producer Jerry Wexler described Brother Ray's voice then: "The emerging sound was unmistakable, brand-new, yet ancient as the woods, the country church of Ray's childhood. The breakthrough was close at hand."

And so began the "Genius of Soul," a hybrid sound that introduces God's voice to man's feelings, which certainly raised a few eyebrows for a while. Ray continued to experiment with his new style. Big bands, small bands, solo, and a variety of backup choruses have spotted his long career. He has also been fortunate enough to work without interference from record companies through the years and be able to choose his own songs.

"I am very into lyrics," Ray explains. "I start with what the words are saying, what the storyline is saying, like a good script. It should really capture me, do something for me. If I don't get it, it's not going to move people, and if it's not going to move people, it's not going to happen. I don't think I'm good because I'm blind, I think I'm good because I'm good."

At one point, stage manager Carl Hunter explained that "he'd [Charles] know it if the band missed a note, a single note. He'd know it if the drummer's left shoelace was flapping. You be with us long enough, you'll swear the man can see." In a performance, Ray's body moves to a different part of the music, but his feet provide the most deft, airbone accompaniment. It's his feet that give the backbeat, the downbeat, the accents, and the tempo; it's the way Ray conducts. In fact, this way of conducting is so powerful that "in rehearsal, if you walk between the band and his feet, they all start cursing you," said Carl.

Ray's publicist, Bob Abrams, says, "You know you're getting a good show when Ray's socks fall down...his feet are going up over the piano. One sock falls half-mast. It's because of all the energy he expands. That's his exercise."

Brother Ray's latest album/CD, "My World," is yet another example of his timeless musical talent. His mix of socially conscious songs with pop standards display a very contemporary side of Ray. There are songs about concern for families and children, as well as peace and unity on the planet.

"Music is powerful," Ray says. "As people listen to it, they can be affected. They respond. But when I was doing this album, I wasn't trying to create an overall message. It just turned out that we got some songs that had something to say." And Ray, along with his all-star cast for some of his songs (like Billy Preston, Mavis Staples, and Eric Clapton), continues his musical experiments this time using synthesizers, sound samplers, and drum machines.

This open attitude keeps Ray current with his fans. During the 1980's and 90's, he caught the attention of a whole new generation with his popular "California Raisin" and Pepsi ("Uh huh") commercials. In fact, the first Diet Pepsi commercial in the fall of 1990 proved to be so unexpectedly popular that Ray Charles is taking home an estimated $3 million from Pepsi after renegotiating his original one-year contract. And for those that missed it, photo "opportunities" were available with life-size cutout figures of Ray Charles and the Raeletts at selected supermarkets last year.

"I must say, I'm proud of that commercial," explains Ray, in his fifth year as spokesperson for Pepsi.

And what about those three sexy background singers dubbed the Reaeletts? Well, Ray has never been one to hold back with women. Next to music, women have always been the major objects of his attention. In Brother Ray, he tells us that no day is worth starting without a love, and many of his songs have been regarded as a sort of report of his fortunes and misfortunes with women.

Battling substance abuse for a number of years, Ray finally enrolled in the rehabiltation program at St. Francis hospital near Los Angeles in 1965. His decision to go cold turkey is an example of his committment to himself, and after overcoming his physical and psychological addiction in his own way, he left the hospital. It was at St. Francis that Ray learned how to play chess and continued to play cards in Braille.

Ray's most recent bout with pain was a serious maddening of inner-ear problems. "I was hearing sound within sounds," he says. For a man that relies so heavily on his hearing, this proved to be quite a scare. Although his problems have since been resolved, Ray felt motivated enough to become involved with groups like Ear International, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit organization for the hearing disabled. His personal donations and fund raising have provided money for research in developing electronic implants, among other devices.

In futhering his dedication to the hearing impaired, Ray urged Congress to increase funding for research into hearing loss in 1987. His visit to Washington, D.C. included speaking before the subcommittees for Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, saying: "Most people take their hearing for granted. I can't. My eyes are my handicap, but my ears are my opportunity. My ears show me what my eyes can't. My ears tell me 99 percent of what I need to know about my world."

In addition to working with Ear International, Ray Charles has shown a long and active concern and involvement with sickle cell disease programs. In 1975, the National Association for Sickle Cell Disease (NASCD) presented their first "Man of Distinction" Award to Ray, and he continues as the L.A. chapter's Honorary Chairman since 1962.

What's next for this multi-talented entertainer? Well, as Ray himself articulates, "music is nothing separate from me. It is me. I can't retire from music any more than I can retire from my liver...I believe the Lord will retire me when He's ready. And then I'll have plenty of time for a long vacation."

What really happened

October 22, 2004

It's a Shame About Ray

Why must biopics sentimentalize their subjects?

by David Ritz

SLATE

Ray, the new biopic directed by Taylor Hackford, satisfies in some wonderful ways: Jamie Foxx miraculously embodies Ray's soul; Ray's own musical voice sounds bigger and better than ever; and several of the supporting performances—Sharon Warren as Ray's mom and Regina King as Margie Hendricks—are heartfelt and powerful. The problem, though, is that Ray is a saccharine movie while Ray himself was anything but a saccharine man. He was a raging bull. Sentimentalizing his story may make box office sense, but, to my mind, it trivializes the compelling complexity of his character.

For example, the film focuses on Ray's relationship with his mother, Aretha. Yet the truth is that Ray had two mothers. According to what Ray told me and insisted we include in Brother Ray, an autobiography that I co-authored in 1978, two women dominated his early years: his biological mother, Aretha, and a woman named Mary Jane, one of his father's former wives. "I called Aretha 'Mama' and Mary Jane 'Mother,' " wrote Ray. After her 6-year-old son went blind, Aretha fostered his independence, while Mary Jane indulged him. For the rest of his life Ray was as fiercely self-reliant as he was self-indulgent. Two dynamic women, two radically different approaches to his sightlessness—you can imagine the impact on his character. Ray ignores this phenomenon completely.

Ray tries to explain Ray's blues—the angst in his heart—in heavy-handed Freudian terms. At age 5, Ray helplessly watched his younger brother, George, drown. The film insists that the guilt Ray felt for failing to rescue George is responsible for the dark side of his soul. Once the guilt is lifted, the adult Ray is not only free from his heroin habit but is liberated—in a treacly flashback—from his emotional turmoil. George's death was certainly traumatic for the young Ray, yet the only time Ray suffered what he termed a nervous breakdown had neither to do with the drowning nor the loss of his sight a year later. "It's the death of my mother Aretha," he told me, "that had me reeling. For days I couldn't talk, think, sleep or eat. I was sure-enough going crazy." That the film fails to dramatize the scene—we learn of Aretha's death in a quick aside from Ray to his wife-to-be—misses the crucial heartbreak of his early life. It happened when Ray was 15, living at a school for the blind 160 miles from home. "I knew my world had ended," he said. The further fact that Ray fails to include a single scene from his extraordinary educational experience is another grievous oversight. It was at that state school where he was taught to read Braille, play Chopin, write arrangements, learn piano and clarinet, start to sing, and discover sex. Ray shows none of that. Such scenes would have been far more illuminating than the unexciting story, which the film does include, of Ray changing managers in midcareer.

The minor characters are another major problem. Take David "Fathead" Newman, the saxophonist who, for over a decade, was Ray's closest musical and personal peer. In Ray, David is portrayed as little more than a loudmouthed junkie. While drugs were part of the bond between David and Ray, the key to their relationship was an extraordinary musical rapport. In real life, David is a soft-spoken, gentle man of few words. As Ray was boisterous, David was shy. Both were brought up on bebop. Like Lester Young/Billie Holiday or Thelonious Monk/Charlie Rouse, they complemented each other in exquisitely sensitive fashion. We neither see nor hear any of this in Ray. And while Hackford features a great number of Ray's hits, he ignores the jazz side of Ray's musical makeup. There's virtually no jazz in Ray, while in real life jazz sat at the center of Ray's soul.

If Fathead is painfully misrepresented, Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler, owners of Atlantic Records, suffer a similar fate. Among the most colorful characters in the colorful history of the music business, they are reduced to stereotypes. We don't get a glimpse of their quirky sophistication, sharp intellect, or salty wit. Same goes for Mary Ann Fisher, the first female singer to join Ray's band. Mary Ann was an engaging character—sometimes endearing, sometimes infuriating. In Ray she's just a manipulative tart.

Finally, though, Ray is about Ray, and its attempt to define his character. In many ways, the definition is accurate. Foxx brilliantly captures Ray's energy and contradictions. Yet those contradictions are not allowed to stand. The contradictions must be resolved, Ray must live happily ever after. The finale implies that, for all his promiscuity, he is back with Della, the true love of his life, and that, with his heroin habit behind him, it's smooth sailing ahead. The paradoxical strands of his life are tied up into a neat package, honoring the hackneyed biopic formula with a leave-'em-smiling Hollywood ending.

The truth is far more complex and far more interesting. Ray's womanizing ways continued. His marriage to Della ended in a difficult divorce in 1976. And while he never again got high on heroin, he found, in his own terms, "a different buzz to keep me going." For the rest of his life he unapologetically drank large quantities of gin every day and smoked large quantities of pot every night. While working on his autobiography he told me, "Just like smack never got in the way of my working, same goes for booze and reefer. What I do with my own body is my own business." Ray maintained this attitude until his health deteriorated. In 2003 he told me that he had been diagnosed with alcoholic liver disease and hepatitis C. "If I knew I was going to live this long," he added with an ironic smile, "I would have taken better care of myself." Whatever Ray was—headstrong, joyful, courageous, cranky—he was hardly a spokesman for sobriety.

The producers of Ray make much of the fact that Ray himself endorsed the movie. That's certainly true. He wanted a successful crossover movie to mirror his successful crossover music. He participated and helped in any way he could. In one of our last discussions, Ray reminded me that the process of trying to sell Hollywood began 26 years ago when producer-director Larry Schiller optioned his story. Since then there have been dozens of false starts. It wasn't until his son, Ray Jr., producer Stuart Benjamin, and director Hackford stayed on the case that cameras rolled.

"Hollywood is a cold-blooded motherfucker," said Ray. "It's easier to bone the President's wife than to get a movie made. So I say God bless these cats. God bless Benjamin and Hackford and Ray Jr. Weren't for them, this would never happen. And now that it's happening, maybe I'll have a better chance of being remembered. I can't ask for anything more."

David Ritz wrote Divided Soul: The Life of Marvin Gaye and co-composed "Sexual Healing" with Marvin Gaye and Odell Brown.

For example, the film focuses on Ray's relationship with his mother, Aretha. Yet the truth is that Ray had two mothers. According to what Ray told me and insisted we include in Brother Ray, an autobiography that I co-authored in 1978, two women dominated his early years: his biological mother, Aretha, and a woman named Mary Jane, one of his father's former wives. "I called Aretha 'Mama' and Mary Jane 'Mother,' " wrote Ray. After her 6-year-old son went blind, Aretha fostered his independence, while Mary Jane indulged him. For the rest of his life Ray was as fiercely self-reliant as he was self-indulgent. Two dynamic women, two radically different approaches to his sightlessness—you can imagine the impact on his character. Ray ignores this phenomenon completely.

Ray tries to explain Ray's blues—the angst in his heart—in heavy-handed Freudian terms. At age 5, Ray helplessly watched his younger brother, George, drown. The film insists that the guilt Ray felt for failing to rescue George is responsible for the dark side of his soul. Once the guilt is lifted, the adult Ray is not only free from his heroin habit but is liberated—in a treacly flashback—from his emotional turmoil. George's death was certainly traumatic for the young Ray, yet the only time Ray suffered what he termed a nervous breakdown had neither to do with the drowning nor the loss of his sight a year later. "It's the death of my mother Aretha," he told me, "that had me reeling. For days I couldn't talk, think, sleep or eat. I was sure-enough going crazy." That the film fails to dramatize the scene—we learn of Aretha's death in a quick aside from Ray to his wife-to-be—misses the crucial heartbreak of his early life. It happened when Ray was 15, living at a school for the blind 160 miles from home. "I knew my world had ended," he said. The further fact that Ray fails to include a single scene from his extraordinary educational experience is another grievous oversight. It was at that state school where he was taught to read Braille, play Chopin, write arrangements, learn piano and clarinet, start to sing, and discover sex. Ray shows none of that. Such scenes would have been far more illuminating than the unexciting story, which the film does include, of Ray changing managers in midcareer.

The minor characters are another major problem. Take David "Fathead" Newman, the saxophonist who, for over a decade, was Ray's closest musical and personal peer. In Ray, David is portrayed as little more than a loudmouthed junkie. While drugs were part of the bond between David and Ray, the key to their relationship was an extraordinary musical rapport. In real life, David is a soft-spoken, gentle man of few words. As Ray was boisterous, David was shy. Both were brought up on bebop. Like Lester Young/Billie Holiday or Thelonious Monk/Charlie Rouse, they complemented each other in exquisitely sensitive fashion. We neither see nor hear any of this in Ray. And while Hackford features a great number of Ray's hits, he ignores the jazz side of Ray's musical makeup. There's virtually no jazz in Ray, while in real life jazz sat at the center of Ray's soul.

If Fathead is painfully misrepresented, Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler, owners of Atlantic Records, suffer a similar fate. Among the most colorful characters in the colorful history of the music business, they are reduced to stereotypes. We don't get a glimpse of their quirky sophistication, sharp intellect, or salty wit. Same goes for Mary Ann Fisher, the first female singer to join Ray's band. Mary Ann was an engaging character—sometimes endearing, sometimes infuriating. In Ray she's just a manipulative tart.

Finally, though, Ray is about Ray, and its attempt to define his character. In many ways, the definition is accurate. Foxx brilliantly captures Ray's energy and contradictions. Yet those contradictions are not allowed to stand. The contradictions must be resolved, Ray must live happily ever after. The finale implies that, for all his promiscuity, he is back with Della, the true love of his life, and that, with his heroin habit behind him, it's smooth sailing ahead. The paradoxical strands of his life are tied up into a neat package, honoring the hackneyed biopic formula with a leave-'em-smiling Hollywood ending.

The truth is far more complex and far more interesting. Ray's womanizing ways continued. His marriage to Della ended in a difficult divorce in 1976. And while he never again got high on heroin, he found, in his own terms, "a different buzz to keep me going." For the rest of his life he unapologetically drank large quantities of gin every day and smoked large quantities of pot every night. While working on his autobiography he told me, "Just like smack never got in the way of my working, same goes for booze and reefer. What I do with my own body is my own business." Ray maintained this attitude until his health deteriorated. In 2003 he told me that he had been diagnosed with alcoholic liver disease and hepatitis C. "If I knew I was going to live this long," he added with an ironic smile, "I would have taken better care of myself." Whatever Ray was—headstrong, joyful, courageous, cranky—he was hardly a spokesman for sobriety.

The producers of Ray make much of the fact that Ray himself endorsed the movie. That's certainly true. He wanted a successful crossover movie to mirror his successful crossover music. He participated and helped in any way he could. In one of our last discussions, Ray reminded me that the process of trying to sell Hollywood began 26 years ago when producer-director Larry Schiller optioned his story. Since then there have been dozens of false starts. It wasn't until his son, Ray Jr., producer Stuart Benjamin, and director Hackford stayed on the case that cameras rolled.

"Hollywood is a cold-blooded motherfucker," said Ray. "It's easier to bone the President's wife than to get a movie made. So I say God bless these cats. God bless Benjamin and Hackford and Ray Jr. Weren't for them, this would never happen. And now that it's happening, maybe I'll have a better chance of being remembered. I can't ask for anything more."

David Ritz wrote Divided Soul: The Life of Marvin Gaye and co-composed "Sexual Healing" with Marvin Gaye and Odell Brown.

LEGENDS OF AMERICAN MUSIC HISTORY

SwingMusic.Net Biography

Ray Charles

SwingMusic.Net Biography

Ray Charles

Crossed countless perceived musical boundaries throughout his career

The legendary performer, known since the 1950s as "The Genius," died June 10th, 2004 of liver disease.

| Ray Charles + American Music = Genius. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ray Charles Robinson was born Sept. 23, 1930, in Albany, Ga. His father, Bailey Robinson, was a mechanic and a handyman, and his mother, Aretha, stacked boards in a sawmill. His family moved to Greenville, Fla., when Charles was an infant. Young Ray grew up during the Great Depression, a period when there was almost no such thing as financial gain for anyone and particularly a black family living in the totally segregated South.

Charles recalled how poor his family was in his 1978 autobiography, "Brother Ray": "Even compared to other blacks...we were on the bottom of the ladder looking up at everyone else. Nothing below us except the ground.''

Although it was a poor existence, and his father was "hardly ever around", he described himself as a "happy kid". The tragedy and painful memories of the next several years however would change him forever.

At just five years old Charles had to endure the trauma of witnessing the drowning death of his younger brother in his mother's large portable laundry tub. Soon after the death of his brother he gradually began to lose his sight and by 7 years of age Ray Charles was blind. Although it is presumed that untreated glaucoma was the cause, no official diagnosis was ever made. His mother refused to let him wallow in self-pity however and since the sight loss was gradual, she began to work with him on how to find things and do things for himself.

Ray had shown an interest in music since the age of 3, encouraged by a cafe owner who played the piano. At 7, he became a charity student at the state-supported school for the deaf and blind in St. Augustine, Fla. Although he was heartbroken to be leaving home, it was at school where he received a formal musical education and learned to read, write and arrange music in Braille; score for big bands; and play piano, organ, sax, clarinet, and trumpet. His influences were the popular stars of the day like big band clarinetist Artie Shaw, big band leaders and pianists Duke Ellington and Count Basie, jazz piano giant Art Tatum, alto sax man and witty vocalist and bandleader Louis Jordan, and the great classical composers like Chopin and Sibelius. But Ray Charles loved it all. At night he listened on the radio to the raw melodies and hillbilly twang of the Grand Ole Opry, to the sanctified soulfulness of gospel, and to the secular emotional venting of the blues. Then at 15 his mother died and Charles, who said he never used a cane or guide dog or begged for money, left school and began touring the South on the so-called chitlin' circuit with a number of dance bands that played in black dance halls.