SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING/SUMMER, 2015

VOLUME ONE NUMBER THREE

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING/SUMMER, 2015

VOLUME ONE NUMBER THREE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

DUKE ELLINGTON

April 25-May 1

ART ENSEMBLE OF CHICAGO

May 2-May 8

ELLA FITZGERALD

May 9-15

DEE DEE BRIDGEWATER

May 16-May 22

MILES DAVIS

May 23-29

JILL SCOTT

May 30-June 5

REGINA CARTER

June 6-June 12

BETTY DAVIS

June 13-19

ERYKAH BADU

June 20-June 26

AL GREEN

June 27-July 3

CHUCK BERRY

July 4-July 10

SLY STONE

July 11-July 17

"If you tried to give rock and roll another name, you might call it 'Chuck Berry'."

--John Lennon

Chuck Berry Wins Prestigious Polar Music Prize

Rock pioneer joins past winners Paul McCartney, Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen

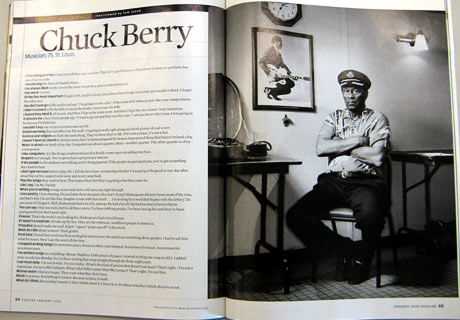

Chuck Berry

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Chuck Berry

will be honored with the Polar Music Prize this year at a ceremony in

Stockholm in late August. The rock pioneer, whose hits "Johnny B.

Goode," "Maybelline" and "Roll Over Beethoven," among others, defined

guitar playing for a generation, will receive £100,000 (a little more

than $169,600) at the ceremony, which Sweden's King Carl XVI Gustaf will

attend, the U.K.'s Telegraph reports.

The award was founded by late Abba manager, lyricist and publisher Stig

Anderson, who wanted it to "break down musical boundaries by bringing

together people from all the different worlds of music." As such, 2014's

other Polar recipient is opera and theater director Peter Sellars.

Past recipients have included Joni Mitchell, Paul Simon,

BB King, Bob Dylan, Ray Charles, Bruce Springsteen and Quincy Jones,

among others. Paul McCartney was the first Polar Music Prize recipient

in 1992; the other recipient in its inaugural year was the Baltic

States, in honor of the region's national music culture. "The difference

with this one for me is that I've presumably been chosen from everyone

in the world," McCartney said at the ceremony. "You can't knock that,

that's a high honor. They could have chosen all sorts of other people, I

can think of a few people who you could choose for a music honor like

this."

Part of Berry's Polar Music Award citation reads, "Every

riff and solo played by rock guitarists over the last 60 years contains

DNA that can be traced right back to Chuck Berry. The Rolling Stones,

the Beatles and a million other groups began to learn their craft by

playing Chuck Berry songs."

CHUCK BERRY

Biography

Chuck Berry melded the blues, country, and a witty,

defiant teen outlook into songs that have influenced virtually every

rock musician in his wake. In his best work — about 40 songs (including

"Round and Round," "Carol," "Brown Eyed Handsome Man," "Roll Over

Beethoven," "Back in the U.S.A.," "Little Queenie"), recorded mostly in

the mid- to late 1950s — Berry matched some of the most resonant and

witty lyrics in pop to music with a blues bottom and a country top,

trademarking the results with his signature double-string guitar lick.

Presenting Berry the prestigious Kennedy Center Honors Award in 2000,

President Bill Clinton hailed him as "one of the 20th Century's most

influential musicians."

- Born Charles Edward Anderson Berry on October 18, 1926, in a

middle-class black neighborhood of St. Louis, Missouri, he learned to

play guitar as a teenager and performed publicly for the first time at

Summer High School covering Jay McShann's "Confessin' the Blues." From

1944 to 1947 Berry was in reform school for attempted robbery; upon

release he worked on the assembly line at a General Motors Fisher body

plant and studied hairdressing and cosmetology at night school. In 1952

he formed a trio with drummer Ebby Harding and pianist Johnnie Johnson,

his keyboardist on and off for the next three decades. By 1955 the trio

had become a top St. Louis-area club band, and Berry was supplementing

his salary as a beautician with regular gigs. He met Muddy Waters in

Chicago in May 1955, and Waters introduced him to Leonard Chess. Berry

played Chess a demo tape that included "Ida Red"; Chess renamed it

"Maybellene," and sent it to disc jockey Alan Freed (who got a cowriting

credit in the deal), and Berry had his first Top 10 hit.

Through 1958 Berry had a string of hits. "School Day" (Number Three pop, Number One R&B, 1957), "Rock & Roll Music" (Number Eight pop, Number Six R&B, 1957), "Sweet Little Sixteen" (Number Two pop, Number One R&B, 1958), and "Johnny B. Goode" (Number Eight pop, Number Five R&B, 1958) were the biggest. With his famous duck walk, Berry was a mainstay on the mid-Fifties concert circuit. He also appeared in such films as Rock, Rock, Rock (1956), Mister Rock and Roll (1957), and Go, Johnny, Go (1959).

Late in 1959 Berry was charged with violating the Mann Act: He had brought a 14-year-old Spanish-speaking Apache waitress and prostitute from Texas to check hats in his St. Louis nightclub, and after he fired her she complained to the police. Following a blatantly racist first trial, he was found guilty at a second. Berry spent two years in federal prison in Indiana, leaving him embittered.

By the time he was released in 1964, the British Invasion was underway, replete with Berry's songs on early albums by the Beatles and Rolling Stones. He recorded a few more classics — including "Nadine" and "No Particular Place to Go" — although it has been speculated that they were written before his jail term. Since then he has written and recorded only sporadically, although he had a million-seller with the novelty song "My Ding-a-Ling" (Number One, 1972), and his last album of new material, 1979's Rockit was a creditable effort. He also appeared in a 1979 film, American Hot Wax. Through it all, Berry continued to perform concerts internationally, often with pickup bands. In the first decade of the 2000s, Hip-O Select released Berry's entire Chess studio output from his prime Fifties and Sixties years as Johnny B. Goode: His Complete '50s Chess Recordings (2007) and You Never Can Tell: The Complete Chess Recordings 1960-1966 (2009). The latter set includes one of his best recorded live shows, a previously unreleased performance captured at a Detroit casino in 1963.

In January 1986 Berry was among the first round of inductees into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The following year he published the at-times sexually and scatalogically explicit Chuck Berry: The Autobiography and was the subject of a documentary/tribute film, Hail! Hail! Rock 'n' Roll, for which his best-known disciple, Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones, organized a backing band.

Berry has continued to tour the world, sometimes with fellow classic rockers such as Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard, and moved to Ladue, Missouri, near St. Louis, where he performs regularly at the Blueberry Hill bar and restaurant.

Portions of this biography appeared in The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll (Simon & Schuster, 2001). Mark Kemp contributed to this article.

Chuck Berry

American musician

by George Lipsitz

Chuck Berry

Also known as

Charles Edward Anderson Berry

born October 18, 1926

Saint Louis, Missouri

Chuck Berry, aka Charles Edward Anderson Berry (born Oct. 18, 1926, St. Louis, Mo., U.S.), is a singer, songwriter, and guitarist who was one of the most popular and influential performers in rhythm-and-blues and rock-and-roll music in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s.

Raised in a working-class African-American neighbourhood on the north side of the highly segregated city of St. Louis, Berry grew up in a family proud of its African-American and Native-American ancestry. He gained early exposure to music through his family’s participation in the choir of the Antioch Baptist Church, through the blues and country-western music he heard on the radio, and through music classes, especially at Sumner High School. Berry was still attending high school when he was sent to serve three years for armed robbery at a Missouri prison for young offenders. After his release and return to St. Louis, he worked at an auto plant, studied hairdressing, and played music in small nightclubs. Berry traveled to Chicago in search of a recording contract; Muddy Waters directed him to the Chess brothers. Leonard and Phil Chess signed him for their Chess label, and in 1955 his first recording session produced “Maybellene” (a country-and-western-influenced song that Berry had originally titled “Ida Red”), which stayed on the pop charts for 11 weeks, cresting at number five. Berry followed this success with extensive tours and hit after hit, including “Roll Over Beethoven” (1956), “School Day” (1957), “Rock and Roll Music” (1957), “Sweet Little Sixteen” (1958), “Johnny B. Goode” (1958), and “Reelin’ and Rockin’” (1958). His vivid descriptions of consumer culture and teenage life, the distinctive sounds he coaxed from his guitar, and the rhythmic and melodic virtuosity of his piano player (Johnny Johnson) made Berry’s songs staples in the repertoire of almost every rock-and-roll band.

At the peak of his popularity, federal authorities prosecuted Berry for violating the Mann Act, alleging that he transported an underage female across state lines “for immoral purposes.” After two trials tainted by racist overtones, Berry was convicted and remanded to prison. Upon his release he placed new hits on the pop charts, including “No Particular Place to Go” in 1964, at the height of the British Invasion, whose prime movers, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, were hugely influenced by Berry (as were the Beach Boys). In 1972 Berry achieved his first number one hit, “My Ding-A-Ling.” Although he recorded more sporadically in the 1970s and ’80s, he continued to appear in concert, most often performing with backing bands comprising local musicians. Berry’s public visibility increased in 1987 with the publication of his book Chuck Berry: The Autobiography and the release of the documentary film Hail! Hail! Rock ‘n’ Roll, featuring footage from his 60th birthday concert and guest appearances by Keith Richards and Bruce Springsteen.

Berry is undeniably one of the most influential figures in the history of rock music. In helping to create rock and roll from the crucible of rhythm and blues, he combined clever lyrics, distinctive guitar sounds, boogie-woogie rhythms, precise diction, an astounding stage show, and musical devices characteristic of country-western music and the blues in his many best-selling single records and albums. A distinctive if not technically dazzling guitarist, Berry used electronic effects to replicate the ringing sounds of bottleneck blues guitarists in his recordings. He drew upon a broad range of musical genres in his compositions, displaying an especially strong interest in Caribbean music on “Havana Moon” (1957) and “Man and the Donkey” (1963), among others. Influenced by a wide variety of artists—including guitar players Carl Hogan, Charlie Christian, and T-Bone Walker and vocalists Nat King Cole, Louis Jordan, and Charles Brown—Berry played a major role in broadening the appeal of rhythm-and-blues music during the 1950s. He fashioned his lyrics to appeal to the growing teenage market by presenting vivid and humorous descriptions of high-school life, teen dances, and consumer culture. His recordings serve as a rich repository of the core lyrical and musical building blocks of rock and roll. In addition to the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, Linda Ronstadt, and a multitude of significant popular-music performers have recorded Berry’s songs.

American musician

by George Lipsitz

Chuck Berry

Also known as

Charles Edward Anderson Berry

born October 18, 1926

Saint Louis, Missouri

Chuck Berry, aka Charles Edward Anderson Berry (born Oct. 18, 1926, St. Louis, Mo., U.S.), is a singer, songwriter, and guitarist who was one of the most popular and influential performers in rhythm-and-blues and rock-and-roll music in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s.

Raised in a working-class African-American neighbourhood on the north side of the highly segregated city of St. Louis, Berry grew up in a family proud of its African-American and Native-American ancestry. He gained early exposure to music through his family’s participation in the choir of the Antioch Baptist Church, through the blues and country-western music he heard on the radio, and through music classes, especially at Sumner High School. Berry was still attending high school when he was sent to serve three years for armed robbery at a Missouri prison for young offenders. After his release and return to St. Louis, he worked at an auto plant, studied hairdressing, and played music in small nightclubs. Berry traveled to Chicago in search of a recording contract; Muddy Waters directed him to the Chess brothers. Leonard and Phil Chess signed him for their Chess label, and in 1955 his first recording session produced “Maybellene” (a country-and-western-influenced song that Berry had originally titled “Ida Red”), which stayed on the pop charts for 11 weeks, cresting at number five. Berry followed this success with extensive tours and hit after hit, including “Roll Over Beethoven” (1956), “School Day” (1957), “Rock and Roll Music” (1957), “Sweet Little Sixteen” (1958), “Johnny B. Goode” (1958), and “Reelin’ and Rockin’” (1958). His vivid descriptions of consumer culture and teenage life, the distinctive sounds he coaxed from his guitar, and the rhythmic and melodic virtuosity of his piano player (Johnny Johnson) made Berry’s songs staples in the repertoire of almost every rock-and-roll band.

At the peak of his popularity, federal authorities prosecuted Berry for violating the Mann Act, alleging that he transported an underage female across state lines “for immoral purposes.” After two trials tainted by racist overtones, Berry was convicted and remanded to prison. Upon his release he placed new hits on the pop charts, including “No Particular Place to Go” in 1964, at the height of the British Invasion, whose prime movers, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, were hugely influenced by Berry (as were the Beach Boys). In 1972 Berry achieved his first number one hit, “My Ding-A-Ling.” Although he recorded more sporadically in the 1970s and ’80s, he continued to appear in concert, most often performing with backing bands comprising local musicians. Berry’s public visibility increased in 1987 with the publication of his book Chuck Berry: The Autobiography and the release of the documentary film Hail! Hail! Rock ‘n’ Roll, featuring footage from his 60th birthday concert and guest appearances by Keith Richards and Bruce Springsteen.

Berry is undeniably one of the most influential figures in the history of rock music. In helping to create rock and roll from the crucible of rhythm and blues, he combined clever lyrics, distinctive guitar sounds, boogie-woogie rhythms, precise diction, an astounding stage show, and musical devices characteristic of country-western music and the blues in his many best-selling single records and albums. A distinctive if not technically dazzling guitarist, Berry used electronic effects to replicate the ringing sounds of bottleneck blues guitarists in his recordings. He drew upon a broad range of musical genres in his compositions, displaying an especially strong interest in Caribbean music on “Havana Moon” (1957) and “Man and the Donkey” (1963), among others. Influenced by a wide variety of artists—including guitar players Carl Hogan, Charlie Christian, and T-Bone Walker and vocalists Nat King Cole, Louis Jordan, and Charles Brown—Berry played a major role in broadening the appeal of rhythm-and-blues music during the 1950s. He fashioned his lyrics to appeal to the growing teenage market by presenting vivid and humorous descriptions of high-school life, teen dances, and consumer culture. His recordings serve as a rich repository of the core lyrical and musical building blocks of rock and roll. In addition to the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, Linda Ronstadt, and a multitude of significant popular-music performers have recorded Berry’s songs.

Chuck Berry performing at the inauguration of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, U.S., on September 2, 1995.

An appropriate tribute to Berry’s centrality to rock and roll came when his song “Johnny B. Goode” was among the pieces of music placed on a copper phonograph record attached to the side of the Voyager 1 satellite, hurtling through outer space, in order to give distant or future civilizations a chance to acquaint themselves with the culture of the planet Earth in the 20th century. In 1984 he was presented with a Grammy Award for lifetime achievement. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1986.

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/chuck-berry-mn0000120521/biography

Artist Biography by Cub Koda

Of all the early breakthrough rock & roll

artists, none is more important to the development of the music than Chuck Berry.

He is its greatest songwriter, the main shaper of its instrumental

voice, one of its greatest guitarists, and one of its greatest

performers. Quite simply, without him there would be no Beatles, Rolling Stones, Beach Boys, Bob Dylan, nor a myriad others. There would be no standard "Chuck Berry

guitar intro," the instrument's clarion call to get the joint rockin'

in any setting. The clippety-clop rhythms of rockabilly would not have

been mainstreamed into the now standard 4/4 rock & roll beat. There

would be no obsessive wordplay by modern-day tunesmiths; in fact, the

whole history (and artistic level) of rock & roll songwriting would

have been much poorer without him. Like Brian Wilson

said, he wrote "all of the great songs and came up with all the rock

& roll beats." Those who do not claim him as a seminal influence or

profess a liking for his music and showmanship show their ignorance of

rock's development as well as his place as the music's first great

creator. Elvis may have fueled rock & roll's imagery, but Chuck Berry was its heartbeat and original mindset.

He was born Charles Edward Anderson Berry to a large family in St. Louis. A bright pupil, Berry developed a love for poetry and hard blues early on, winning a high school talent contest with a guitar-and-vocal rendition of Jay McShann's big band number, "Confessin' the Blues." With some local tutelage from the neighborhood barber, Berry progressed from a four-string tenor guitar up to an official six-string model and was soon working the local East St. Louis club scene, sitting in everywhere he could. He quickly found out that black audiences liked a wide variety of music and set himself to the task of being able to reproduce as much of it as possible. What he found they really liked -- besides the blues and Nat King Cole tunes -- was the sight and sound of a black man playing white hillbilly music, and Berry's showmanlike flair, coupled with his seemingly inexhaustible supply of fresh verses to old favorites, quickly made him a name on the circuit. In 1954, he ended up taking over pianist Johnny Johnson's small combo and a residency at the Cosmopolitan Club soon made the Chuck Berry Trio the top attraction in the black community, with Ike Turner's Kings of Rhythm their only real competition.

But Berry had bigger ideas; he yearned to make records, and a trip to Chicago netted a two-minute conversation with his idol Muddy Waters, who encouraged him to approach Chess Records. Upon listening to Berry's homemade demo tape, label president Leonard Chess professed a liking for a hillbilly tune on it named "Ida Red" and quickly scheduled a session for May 21, 1955. During the session the title was changed to "Maybellene" and rock & roll history was born. Although the record only made it to the mid-20s on the Billboard pop chart, its overall influence was massive and groundbreaking in its scope. Here was finally a black rock & roll record with across-the-board appeal, embraced by white teenagers and Southern hillbilly musicians (a young Elvis Presley, still a full year from national stardom, quickly added it to his stage show), that for once couldn't be successfully covered by a pop singer like Snooky Lanson on Your Hit Parade. Part of the secret to its originality was Berry's blazing 24-bar guitar solo in the middle of it, the imaginative rhyme schemes in the lyrics, and the sheer thump of the record, all signaling that rock & roll had arrived and it was no fad. Helping to put the record over to a white teenage audience was the highly influential New York disc jockey Alan Freed, who had been given part of the writers' credit by Chess in return for his spins and plugs. But to his credit, Freed was also the first white DJ/promoter to consistently use Berry on his rock & roll stage show extravaganzas at the Brooklyn Fox and Paramount theaters (playing to predominately white audiences); and when Hollywood came calling a year or so later, also made sure that Chuck appeared with him in Rock! Rock! Rock!, Go, Johnny, Go!, and Mister Rock'n'Roll. Within a years' time, Chuck had gone from a local St. Louis blues picker making 15 dollars a night to an overnight sensation commanding over a hundred times that, arriving at the dawn of a new strain of popular music called rock & roll.

The hits started coming thick and fast over the next few years, every one of them about to become a classic of the genre: "Roll Over Beethoven," "Thirty Days," "Too Much Monkey Business," "Brown Eyed Handsome Man," "You Can't Catch Me," "School Day," "Carol," "Back in the U.S.A.," "Little Queenie," "Memphis, Tennessee," "Johnny B. Goode," and the tune that defined the moment perfectly, "Rock and Roll Music." Berry was not only in constant demand, touring the country on mixed package shows and appearing on television and in movies, but smart enough to know exactly what to do with the spoils of a suddenly successful show business career. He started investing heavily in St. Louis area real estate and, ever one to push the envelope, opened up a racially mixed nightspot called the Club Bandstand in 1958 to the consternation of uptight locals. These were not the plans of your average R&B singers who contented themselves with a wardrobe of flashy suits, a new Cadillac, and the nicest house in the black section. Berry was smart with plenty of business savvy and was already making plans to open an amusement park in nearby Wentzville. When the St. Louis hierarchy found out that an underage hat-check girl Berry hired had also set up shop as a prostitute at a nearby hotel, trouble came down on Berry like a sledgehammer on a fly. Charged with transporting a minor over state lines (the Mann Act), Berry endured two trials and was sentenced to federal prison for two years as a result.

He emerged from prison a moody, embittered man. But two very important things had happened in his absence. First, British teenagers had discovered his music and were making his old songs hits all over again. Second, and perhaps most important, America had discovered the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, both of whom based their music on Berry's style, with the Stones' early albums looking like a Berry song list. Rather than being resigned to the has-been circuit, Berry found himself in the midst of a worldwide beat boom with his music as the centerpiece. He came back with a clutch of hits ("Nadine," "No Particular Place to Go," "You Never Can Tell"), toured Britain in triumph, and appeared on the big screen with his British disciples in the groundbreaking T.A.M.I. Show in 1964.

Berry had moved with the times and found a new audience in the bargain and when the cries of "yeah-yeah-yeah" were replaced with peace signs, Berry altered his live act to include a passel of slow blues and quickly became a fixture on the festival and hippie ballroom circuit. After a disastrous stint with Mercury Records, he returned to Chess in the early '70s and scored his last hit with a live version of the salacious nursery rhyme, "My Ding a Ling," yielding Berry his first official gold record. By decade's end, he was as in demand as ever, working every oldies revival show, TV special, and festival that was thrown his way. But once again, troubles with the law reared their ugly head and 1979 saw Berry headed back to prison, this time for income tax evasion. Upon release this time, the creative days of Chuck Berry seemed to have come to an end. He appeared as himself in the Alan Freed bio-pic, American Hot Wax, and was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, but steadfastly refused to record any new material or even issue a live album. His live performances became increasingly erratic, with Berry working with terrible backup bands and turning in sloppy, out-of-tune performances that did much to tarnish his reputation with younger fans and oldtimers alike. In 1987, he published his first book, Chuck Berry: The Autobiography, and the same year saw the film release of what will likely be his lasting legacy, the rockumentary Hail! Hail! Rock'n'Roll, which included live footage from a 60th-birthday concert with Keith Richards as musical director and the usual bevy of superstars coming out for guest turns. But for all of his off-stage exploits and seemingly ongoing troubles with the law, Chuck Berry remains the epitome of rock & roll, and his music will endure long after his private escapades have faded from memory. Because when it comes down to his music, perhaps John Lennon said it best, "If you were going to give rock & roll another name, you might call it 'Chuck Berry'."

He was born Charles Edward Anderson Berry to a large family in St. Louis. A bright pupil, Berry developed a love for poetry and hard blues early on, winning a high school talent contest with a guitar-and-vocal rendition of Jay McShann's big band number, "Confessin' the Blues." With some local tutelage from the neighborhood barber, Berry progressed from a four-string tenor guitar up to an official six-string model and was soon working the local East St. Louis club scene, sitting in everywhere he could. He quickly found out that black audiences liked a wide variety of music and set himself to the task of being able to reproduce as much of it as possible. What he found they really liked -- besides the blues and Nat King Cole tunes -- was the sight and sound of a black man playing white hillbilly music, and Berry's showmanlike flair, coupled with his seemingly inexhaustible supply of fresh verses to old favorites, quickly made him a name on the circuit. In 1954, he ended up taking over pianist Johnny Johnson's small combo and a residency at the Cosmopolitan Club soon made the Chuck Berry Trio the top attraction in the black community, with Ike Turner's Kings of Rhythm their only real competition.

But Berry had bigger ideas; he yearned to make records, and a trip to Chicago netted a two-minute conversation with his idol Muddy Waters, who encouraged him to approach Chess Records. Upon listening to Berry's homemade demo tape, label president Leonard Chess professed a liking for a hillbilly tune on it named "Ida Red" and quickly scheduled a session for May 21, 1955. During the session the title was changed to "Maybellene" and rock & roll history was born. Although the record only made it to the mid-20s on the Billboard pop chart, its overall influence was massive and groundbreaking in its scope. Here was finally a black rock & roll record with across-the-board appeal, embraced by white teenagers and Southern hillbilly musicians (a young Elvis Presley, still a full year from national stardom, quickly added it to his stage show), that for once couldn't be successfully covered by a pop singer like Snooky Lanson on Your Hit Parade. Part of the secret to its originality was Berry's blazing 24-bar guitar solo in the middle of it, the imaginative rhyme schemes in the lyrics, and the sheer thump of the record, all signaling that rock & roll had arrived and it was no fad. Helping to put the record over to a white teenage audience was the highly influential New York disc jockey Alan Freed, who had been given part of the writers' credit by Chess in return for his spins and plugs. But to his credit, Freed was also the first white DJ/promoter to consistently use Berry on his rock & roll stage show extravaganzas at the Brooklyn Fox and Paramount theaters (playing to predominately white audiences); and when Hollywood came calling a year or so later, also made sure that Chuck appeared with him in Rock! Rock! Rock!, Go, Johnny, Go!, and Mister Rock'n'Roll. Within a years' time, Chuck had gone from a local St. Louis blues picker making 15 dollars a night to an overnight sensation commanding over a hundred times that, arriving at the dawn of a new strain of popular music called rock & roll.

The hits started coming thick and fast over the next few years, every one of them about to become a classic of the genre: "Roll Over Beethoven," "Thirty Days," "Too Much Monkey Business," "Brown Eyed Handsome Man," "You Can't Catch Me," "School Day," "Carol," "Back in the U.S.A.," "Little Queenie," "Memphis, Tennessee," "Johnny B. Goode," and the tune that defined the moment perfectly, "Rock and Roll Music." Berry was not only in constant demand, touring the country on mixed package shows and appearing on television and in movies, but smart enough to know exactly what to do with the spoils of a suddenly successful show business career. He started investing heavily in St. Louis area real estate and, ever one to push the envelope, opened up a racially mixed nightspot called the Club Bandstand in 1958 to the consternation of uptight locals. These were not the plans of your average R&B singers who contented themselves with a wardrobe of flashy suits, a new Cadillac, and the nicest house in the black section. Berry was smart with plenty of business savvy and was already making plans to open an amusement park in nearby Wentzville. When the St. Louis hierarchy found out that an underage hat-check girl Berry hired had also set up shop as a prostitute at a nearby hotel, trouble came down on Berry like a sledgehammer on a fly. Charged with transporting a minor over state lines (the Mann Act), Berry endured two trials and was sentenced to federal prison for two years as a result.

He emerged from prison a moody, embittered man. But two very important things had happened in his absence. First, British teenagers had discovered his music and were making his old songs hits all over again. Second, and perhaps most important, America had discovered the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, both of whom based their music on Berry's style, with the Stones' early albums looking like a Berry song list. Rather than being resigned to the has-been circuit, Berry found himself in the midst of a worldwide beat boom with his music as the centerpiece. He came back with a clutch of hits ("Nadine," "No Particular Place to Go," "You Never Can Tell"), toured Britain in triumph, and appeared on the big screen with his British disciples in the groundbreaking T.A.M.I. Show in 1964.

Berry had moved with the times and found a new audience in the bargain and when the cries of "yeah-yeah-yeah" were replaced with peace signs, Berry altered his live act to include a passel of slow blues and quickly became a fixture on the festival and hippie ballroom circuit. After a disastrous stint with Mercury Records, he returned to Chess in the early '70s and scored his last hit with a live version of the salacious nursery rhyme, "My Ding a Ling," yielding Berry his first official gold record. By decade's end, he was as in demand as ever, working every oldies revival show, TV special, and festival that was thrown his way. But once again, troubles with the law reared their ugly head and 1979 saw Berry headed back to prison, this time for income tax evasion. Upon release this time, the creative days of Chuck Berry seemed to have come to an end. He appeared as himself in the Alan Freed bio-pic, American Hot Wax, and was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, but steadfastly refused to record any new material or even issue a live album. His live performances became increasingly erratic, with Berry working with terrible backup bands and turning in sloppy, out-of-tune performances that did much to tarnish his reputation with younger fans and oldtimers alike. In 1987, he published his first book, Chuck Berry: The Autobiography, and the same year saw the film release of what will likely be his lasting legacy, the rockumentary Hail! Hail! Rock'n'Roll, which included live footage from a 60th-birthday concert with Keith Richards as musical director and the usual bevy of superstars coming out for guest turns. But for all of his off-stage exploits and seemingly ongoing troubles with the law, Chuck Berry remains the epitome of rock & roll, and his music will endure long after his private escapades have faded from memory. Because when it comes down to his music, perhaps John Lennon said it best, "If you were going to give rock & roll another name, you might call it 'Chuck Berry'."

CHUCK BERRY

Why is Chuck Berry often considered the most important of the early Rock and Rollers?

OVERVIEW

“If you tried to give Rock and Roll another name, you might call it 'Chuck Berry.'”

-- John Lennon

Chuck Berry burst onto the Rock and Roll scene in 1955 with the

release of “Maybellene” on Chess Records. It shot to No. 1 on

Billboard’s R&B chart and No. 5 on the Pop chart, establishing Berry

as an artist with appeal to black and white audiences alike. By the end

of the decade, Berry had released a string of iconic songs – “Roll

Over, Beethoven,” “Schools Days,” “Rock and Roll Music,” “Sweet Little

Sixteen,” “Johnny B. Goode,” “Back in the U.S.A." – that would be

covered by everyone from the Beach Boys to the Grateful Dead.

Distinct from Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Fats Domino – all

piano players – Berry was a guitar player whose guitar was a central

component of his recordings. Gone were the horns, central to much

R&B, and gone was the piano as focal point. Guitar-based Rock and

Roll had its founding father.

In this lesson, students will analyze several of the elements that

combined to make Berry such an important and influential artist. They

will examine his pioneering guitar riffs, his carefully crafted lyrics

that spoke directly to the emerging market of white, middle-class

teen listeners, his blend of R&B and Country and Western

influences, and his energetic performance style, which helped pave the

way for a generation of guitar-playing showmen.

Chuck Berry

by Robert Christgau

by Robert Christgau

Chuck Berry is the greatest of the rock and rollers. Elvis competes with Frank Sinatra, Little Richard camps his way to self-negation, Fats Domino looks old, and Jerry Lee Lewis looks down his noble honker at all those who refuse to understand that Jerry Lee has chosen to become a great country singer. But for a fee--which went up markedly after the freak success of "My Ding-a-Ling," his first certified million-seller, in 1972, and has now diminished again--Chuck Berry will hop on a plane with his guitar and go play some rock and roll. He is the symbol of the music--the first man elected to a Rock Music Hall of Fame that exists thus far only in the projections of television profiteers; the man invited to come steal the show at the 1975 Grammys, although he has never been nominated for one himself, not even in the rock and roll or rhythm and blues categories. More important, he is also the music's substance--he taught George Harrison and Keith Richard to play guitar long before he met either, and his songs are still claimed as encores by everyone from folkies to heavy-metal kids. But Chuck Berry isn't merely the greatest of the rock and rollers, or rather, there's nothing mere about it. Say rather that unless we can somehow recycle the concept of the great artist so that it supports Chuck Berry as well as it does Marcel Proust, we might as well trash it altogether.

As with Charlie Chaplin or Walt Kelly or the Beatles, Chuck Berry's greatness doesn't depend entirely on the greatness or originality of his oeuvre. The body of his top-quality work isn't exactly vast, comprising three or perhaps four dozen songs that synthesize two related traditions: blues, and country and western. Although in some respects Berry's rock and roll is simpler and more vulgar than either of its musical sources, its simplicity and vulgarity are defensible in the snootiest high-art terms--how about "instinctive minimalism" or "demotic voice"? But his case doesn't rest on such defenses. It would be as perverse to argue that his songs are in themselves as rich as, say, Remembrance of Things Past. Their richness is rather a function of their active relationship with an audience--a complex relationship that shifts every time a song enters a new context, club or album or radio or mass singalong. Where Proust wrote about a dying subculture from a cork-lined room, Berry helped give life to a subculture, and both he and it change every time they confront each other. Even "My Ding-a-Ling," a fourth-grade wee-wee joke that used to mortify true believers at college concerts, permitted a lot of 12-year-olds new insight into the moribund concept of "dirty" when it hit the airwaves; the song changed again when an oldies crowd became as children to shout along with Uncle Chuck the night he received his gold record at Madison Square Garden. And what happened to "Brown Eyed Handsome Man," never a hit among whites, when Berry sang it at interracial rock and roll concerts in Northern cities in the Fifties? How many black kids took "eyed" as code for "skinned"? How many whites? How did that make them feel about each other, and about the song? And did any of that change the song itself?

Berry's own intentions, of course, remain a mystery. Typically, this public artist is an obsessively private person who has been known to drive reporters from his own amusement park, and the sketches of his life overlap and contradict each other. The way I tell it, Berry was born into a lower middle-class colored family in St. Louis in 1926. He was so quick and ambitious that he both served time in reform school on a robbery conviction and acquired a degree in hairdressing and cosmetology before taking a job on an auto assembly line to support a wife and kids. Yet his speed and ambition persisted. By 1953 he was working as a beautician and leading a three-piece blues group on a regular weekend gig. His gimmick was to cut the blues with country-influenced humorous narrative songs. These were rare in the black music of the time, although they had been common enough before phonograph records crystallized the blues form, and although Louis Jordan, a hero of Berry's, had been doing something vaguely similar in front of white audiences for years.

In 1955, Berry recorded two of his songs on a borrowed machine--"Wee Wee Hours," a blues that he and his pianist, Johnnie Johnson, hoped to sell, and an adapted country tune called "Ida Red." He traveled to Chicago and met Muddy Waters, the uncle of the blues, who sent him on to Leonard Chess of Chess Records. Chess liked "Wee Wee Hours" but flipped for "Ida Red," which was renamed "Maybellene," a hairdresser's dream, and forwarded to Allan Freed. Having mysteriously acquired one-third of the writer's credit with another DJ, Freed played "Maybellene" quite a lot, and it became one of the first nationwide rock 'n' roll hits.

At that time, any fair-minded person would have judged this process exploitative and pecuniary. A blues musician comes to a blues label to promote a blues song--"It was `Wee Wee Hours' we was proud of, that was our music," says Johnnie Johnson--but the owner of the label decides he wants to push a novelty: "The big beat, cars, and young love. It was a trend and we jumped on it," Chess has said. The owner then trades away a third of the blues singer's creative sweat to the symbol of payola, who hypes the novelty song into commercial success and leaves the artist in a quandry. Does he stick with his art, thus forgoing the first real recognition he's ever had, or does he pander to popular taste?

The question is loaded, of course. "Ida Red" was Chuck Berry's music as much as "Wee Wee Hours," which in retrospect seems rather uninspired. In fact, maybe the integrity problem went the other way. Maybe Johnson was afraid that the innovations of "Ida Red"--country guitar lines adapted to blues-style picking, with the ceaseless legato of his own piano adding rhythmic excitement to the steady backbeat--were too far out to sell. What happened instead was that Berry's limited but brilliant vocabulary of guitar riffs quickly came to epitomize rock 'n' roll. Ultimately, every great white guitar group of the early Sixties imitated Berry's style, and Johnson's piano technique was almost as influential. In other words, it turned out that Berry and Johnson weren't basically bluesmen at all. Through some magic combination of inspiration and cultural destiny, they had hit upon something more contemporary than blues, and a young audience, for whom the Depression was one more thing that bugged their parents, understood this better than the musicians themselves. Leonard Chess simply functioned as a music businessman should, though only rarely does one combine the courage and insight (and opportunity) to pull it off, even once. Chess became a surrogate audience, picking up on new music and making sure that it received enough exposure for everyone else to pick up on it, too.

Obviously, Chuck Berry wasn't racked with doubt about artistic compromise. A good blues single usually sold around 10,000 copies and a big rhythm and blues hit might go into the hundreds of thousands, but "Maybellene" probably moved a million, even if Chess never sponsored the audit to prove it. Berry had achieved a grip on the white audience and the solid future it could promise, and, remarkably, he had in no way diluted his genius to do it. On the contrary, that was his genius. He would never have fulfilled himself if he hadn't explored his relationship to the white world--a relationship which was much different for him, an urban black man who was used to machines and had never known brutal poverty, than it was for, say, Muddy Waters.

Berry was the first blues-based performer to successfully reclaim guitar tricks that country and western innovators had appropriated from black people and adapted to their own uses 25 or 50 years before. By adding blues tone to some fast country runs, and yoking them to a rhythm and blues beat and some unembarrassed electrification, he created an instrumental style with biracial appeal. Alternating guitar chords augmented the beat while Berry sang in an insouciant tenor that, while recognizably Afro-American in accent, stayed clear of the melisma and blurred overtones of blues singing, both of which enter only at carefully premeditated moments. His few detractors still complain about the repetitiveness of this style, but they miss the point. Repetition without tedium is the backbone of rock and roll, and the components of Berry's music proved so durable that they still provoke instant excitement at concerts durable that they still provoke instant excitement at concerts two decades later. And in any case, the instrumental repetition was counterbalanced by unprecedented and virtually unduplicated verbal variety.

Chuck Berry is the greatest rock lyricist this side of Bob Dylan, and sometimes I prefer him to Dylan. Both communicate an abundance of the childlike delight in linguistic discovery that page poets are supposed to convey and too often don't, but Berry's most ambitious lyrics, unlike Dylan's, never seem pretentious or forced. True, his language is ersatz and barbaric, full of mispronounced foreignisms and advertising coinages, but then, so was Whitman's. Like Whitman, Berry is excessive because he is totally immersed in America--the America of Melville and the Edsel, burlesque and installment-plan funerals, pemmican and pomade. Unlike Whitman, though, he doesn't quite permit you to take him seriously--he can't really think it's pronounced "a la carty," can he? He is a little surreal. How else can a black man as sensitive as Chuck Berry respond to the affluence of white America--an affluence suddenly his for the taking.

Chuck Berry is not only a little surreal but also a little schizy; even after he committed himself to rock 'n' roll story songs, relegating the bluesman in him to B sides and album fillers, he found his persona split in two. In three of the four singles that followed "Maybellene," he amplified the black half of his artistic personality, the brown-eyed handsome man who always came up short in his quest for the small-time hedonism American promises everyone. By implication, Brown Eyes' sharp sense of life's nettlesome and even oppressive details provided a kind of salvation by humor, especially in "Too Much Monkey Business," a catalog of hassles that included work, school and the army. But the white teenagers who were the only audience with the cultural experience to respond to Berry's art weren't buying this kind of salvation, not en masse. They wanted something more optimistic and more specific to themselves; of the four singles that followed "Maybellene," only "Roll Over Beethoven," which introduced Berry's other half, the rock 'n' roller, achieved any real success. Chuck got the message. His next release, "School Day," was another complaint song, but this time the complaints were explicitly adolescent and were relieved by the direct action of the rock 'n' roller. In fact, the song has been construed as a prophecy of the Free Speech Movement: "Close your books, get out of your seat/Down the halls and into the street."

It has become a cliché to attribute the rise of rock and roll to a new parallelism between white teenagers and black Americans; a common "alienation" and even "suffering" are often cited. As with most clichés, this one has its basis in fact--teenagers in the Fifties certainly showed an unprecedented consciousness of themselves as a circumscribed group, though how much that had to do with marketing refinements and how much with the Bomb remains unresolved. In any case, Chuck Berry's history points up the limits of this notion. For Berry was closer to white teenagers both economically (that reform school stint suggests a JD exploit, albeit combined with a racist judicial system) and in spirit (he shares his penchant for youthfulness with Satchel Paige but not Henry Aaron, with Leslie Fiedler but not Norman Podhoretz) than the average black man. And even at that, he had to make a conscious (not to say calculated) leap of the imagination to reach them, and sometimes fell short.

Although he scored lots of minor hits, Chuck Berry made only three additional Billboard Top Ten singles in the Fifties--"Rock and Roll Music," "Sweet Little Sixteen," and "Johnny B. Goode"--and every one of them ignored Brown Eyes for the assertive, optimistic, and somewhat simpleminded rock 'n' roller. In a pattern common among popular artists, his truest and most personal work didn't flop, but it wasn't overwhelmingly popular either. For such artists, the audience can be like a drug. A little of it is so good for them that they assume a lot of it would be even better, but instead the big dose saps their autonomy, often so subtly that they don't notice it. For Chuck Berry, the craving for overwhelming popularity proved slightly dangerous. At the same time that he was enlivening his best songs with faintly Latin rhythms, which he was convinced were the coming thing, he was also writing silly exercises with titles like "Hey Pedro." Nevertheless, his pursuit of the market also worked a communion with his audience, with whom he continued to have an instinctive rapport remarkable in a 30-year-old black man. For there is also a sense in which the popular artist is a drug for the audience, and a doctor, too--he has to know how much of his vital essence he can administer at one time, and in what compound.

The reason Berry's rock 'n' roller was capable of such insightful excursions into the teen psyche--"Sweet Little Sixteen," a celebration of everything lovely about fanhood; or "Almost Grown," a basically unalianated first-person expression of teen rebellion that Sixties youth-cult pundits should have taken seriously--was that he shared a crucial American value with the humorous Brown Eyes. That value was fun. Even among rock critics, who ought to know better, fun doesn't have much of a rep, so that they commiserate with someone like LaVern Baker, a second-rate blues and gospel singer who felt she was selling her soul every time she launched into a first-rate whoop of nonsense like "Jim Dandy" or "Bumble Bee." But fun was what adolescent revolt had to be about--inebriated affluence versus the hangover of the work ethic. It was the only practicable value in the Peter Pan utopia of the American dream. Because black music had always thrived on exuberance--not just the otherworldly transport of gospel, but the candidly physical good times of great pop blues singers like Washboard Sam, who is most often dismissed as a lightweight by the heavy blues critics--it turned into the perfect vehicle for generational convulsion. Black musicians, however, had rarely achieved an optimism that was cultural as well as personal--those few who did, like Louis Armstrong, left themselves open to charges of Tomming. Chuck Berry never Tommed. The trouble he'd seen just made his sly, bad-boy voice and the splits and waddles of his stage show that much more credible.

Then, late in 1959, fun turned into trouble. Berry had imported a Spanish-speaking Apache prostitute he'd picked up in El Paso to check hats in his St. Louis nightclub, and then fired her. She went to the police, and Berry was indicted under the Mann Act. After two trials, the first so blatantly racist that it was disallowed, he went to prison for two years. When he got out, in 1964, he and his wife had separated, apparently a major tragedy for him. The Beatles and the Rolling Stones had paid him such explicit and appropriate tribute that his career was probably in better shape after his jail term than before, but he couldn't capitalize. He had a few hits--"Nadine" and "No Particular Place to Go" (John Lennon is one of the many who believe they were written before he went in)--but the well was dry. Between 1965 and 1970 he didn't release one-even passable new song, and he died as a recording artist.

In late 1966, Berry left Chess for a big advance from Mercury Records. The legends of his money woes at Chess are numerous, but apparently the Chess brothers knew how to record him--the stuff he produced himself for Mercury was terrible. Working alone with pickup bands, he still performed a great deal, mostly to make money for Berry Park, a recreation haven 30 miles from St. Louis. And as he toured, he found that something had happened to his old audience--it was getting older, with troubles of its own, and it dug blues. At auditoriums like the Fillmore, where he did a disappointing live LP with the Steve Miller Blues Band, Chuck was more than willing to stretch out on a blues. One of his favorites was from Elmore James: "When things go wrong, wrong with you, it hurts me too."

By 1970, he was back home at Chess, and suddenly his new audience called forth a miracle. Berry was a natural head--no drugs, no alcohol--and most of his attempts to cash in on hippie talk had been embarrassments. But "Tulane," one of his greatest story songs, was the perfect fantasy. It was about two dope dealers: "Tulane and Johnny opened a novelty shop/ Back under the counter was the cream of the crop." Johnny is nabbed by narcs, but Tulane, his girlfriend, escapes, and Johnny confidently predicts that she will buy off the judge. Apparently she does, for there is a sequel, a blues. In "Have Mercy Judge," Johnny has been caught again, and this time he expects to be sent to "some stony mansion." Berry devotes the last stanza to Tulane, who is "too alive to live alone." The last line makes me wonder just how he felt about his own wife when he went to prison: "Just tell her to live, and I'll forgive her, and even love her more when I come back home."

Taken together, the two songs are Berry's peak, although Leonard Chess would no doubt have vetoed the vocal double-track on "Tulane" that blurs its impact a bit. Remarkably, "Have Mercy Judge" is the first important blues Berry ever wrote, and like all his best work it isn't quite traditional, utilizing an abc line structure instead of the usual aab. Where did it come from? Is it unreasonable to suspect that part of Berry really was a bluesman all along, and that this time, instead of him going to his audience, his audience came to him and provided the juice for one last masterpiece?

Berry's career would appear closed. He is a rock and roll monument at 50, a pleasing performer whose days of inspiration are over. Sometime in the next 30 years he will probably die, and while his songs have already stuck in the public memory a lot longer than Washboard Sam's, it's likely that most of them will fade away too. So is he, was he, will he be a great artist? It won't be we judging, but perhaps we can think of it this way. Maybe the true measure of his greatness was not whether his songs "lasted"--a term which as of now means persisted through centuries instead of decades--but that he was one of the ones to make us understand that the greatest thing about art is the way it happens between people. I am grateful for aesthetic artifacts, and I suspect that a few of Berry's songs, a few of his recordings, will live on in that way. I only hope that they prove too alive to live alone. If they do, and if by some mishap Berry's name itself is forgotten, that will nevertheless be an entirely apposite kind of triumph for him.

Discography

"Maybellene" (Chess 1604; * 5, r* 1, 1955).

"Thirty Days" (Chess 1610; r* 8, 1955).

"No Money Down" (Chess 1615; r* 11, 1956).

"Roll Over Beethoven" (Chess 1626; r* 7, *29, 1956).

"Too Much Monkey Business" b/w "Brown Eyed Handsome Man" (Chess 1635; r* 7, 1956).

"School Day" (Chess 1653; r* 1, *5, 1957).

"Oh Baby Doll" (Chess 1664; * 57, 1957).

"Rock and Roll Music" (Chess 1671; * 8, r* 6, 1957).

"Sweet Little Sixteen" (Chess 1683; r* 1, *2, 1958).

"Johnny B. Goode" (Chess 1691; r* 5, * 8, 1958).

"Carol" (Chess 1700; r* 12, * 18, 1958).

"Sweet Little Rock and Roll" (Chess 1709; r* 13, * 47, 1958).

"Anthony Boy" (Chess 1716; * 60, 1959).

"Almost Grown" (Chess 1722; r* 3, * 32, 1959).

"Back in the U.S.A." (Chess 1729; r* 16, * 37, 1959).

"Too Pooped to Pop" (Chess 1747; r* 18, * 42, 1960).

"Nadine" (Chess 1883; * 23, 1964).

"No Particular Place to Go" (Chess 1898; * 10, 1964).

"You Never Can Tell" (Chess 1906; * 14, 1964).

"Little Marie" (Chess 1912; * 54, 1964).

"Promised Land" (Chess 1916; * 41, 1964).

"My Ding-a-Ling" (Chess 2131; * 1, 1972).

"Reelin' and Rockin'" (Chess 2136; * 27, 1972).

(Chart positions compiled from Joel Whitburn's Record Research, based on Billboard Pop chart, unless otherwise indicated; r* = position on Billboard Rhythm and Blues chart.)

The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll, 1976

As with Charlie Chaplin or Walt Kelly or the Beatles, Chuck Berry's greatness doesn't depend entirely on the greatness or originality of his oeuvre. The body of his top-quality work isn't exactly vast, comprising three or perhaps four dozen songs that synthesize two related traditions: blues, and country and western. Although in some respects Berry's rock and roll is simpler and more vulgar than either of its musical sources, its simplicity and vulgarity are defensible in the snootiest high-art terms--how about "instinctive minimalism" or "demotic voice"? But his case doesn't rest on such defenses. It would be as perverse to argue that his songs are in themselves as rich as, say, Remembrance of Things Past. Their richness is rather a function of their active relationship with an audience--a complex relationship that shifts every time a song enters a new context, club or album or radio or mass singalong. Where Proust wrote about a dying subculture from a cork-lined room, Berry helped give life to a subculture, and both he and it change every time they confront each other. Even "My Ding-a-Ling," a fourth-grade wee-wee joke that used to mortify true believers at college concerts, permitted a lot of 12-year-olds new insight into the moribund concept of "dirty" when it hit the airwaves; the song changed again when an oldies crowd became as children to shout along with Uncle Chuck the night he received his gold record at Madison Square Garden. And what happened to "Brown Eyed Handsome Man," never a hit among whites, when Berry sang it at interracial rock and roll concerts in Northern cities in the Fifties? How many black kids took "eyed" as code for "skinned"? How many whites? How did that make them feel about each other, and about the song? And did any of that change the song itself?

Berry's own intentions, of course, remain a mystery. Typically, this public artist is an obsessively private person who has been known to drive reporters from his own amusement park, and the sketches of his life overlap and contradict each other. The way I tell it, Berry was born into a lower middle-class colored family in St. Louis in 1926. He was so quick and ambitious that he both served time in reform school on a robbery conviction and acquired a degree in hairdressing and cosmetology before taking a job on an auto assembly line to support a wife and kids. Yet his speed and ambition persisted. By 1953 he was working as a beautician and leading a three-piece blues group on a regular weekend gig. His gimmick was to cut the blues with country-influenced humorous narrative songs. These were rare in the black music of the time, although they had been common enough before phonograph records crystallized the blues form, and although Louis Jordan, a hero of Berry's, had been doing something vaguely similar in front of white audiences for years.

In 1955, Berry recorded two of his songs on a borrowed machine--"Wee Wee Hours," a blues that he and his pianist, Johnnie Johnson, hoped to sell, and an adapted country tune called "Ida Red." He traveled to Chicago and met Muddy Waters, the uncle of the blues, who sent him on to Leonard Chess of Chess Records. Chess liked "Wee Wee Hours" but flipped for "Ida Red," which was renamed "Maybellene," a hairdresser's dream, and forwarded to Allan Freed. Having mysteriously acquired one-third of the writer's credit with another DJ, Freed played "Maybellene" quite a lot, and it became one of the first nationwide rock 'n' roll hits.

At that time, any fair-minded person would have judged this process exploitative and pecuniary. A blues musician comes to a blues label to promote a blues song--"It was `Wee Wee Hours' we was proud of, that was our music," says Johnnie Johnson--but the owner of the label decides he wants to push a novelty: "The big beat, cars, and young love. It was a trend and we jumped on it," Chess has said. The owner then trades away a third of the blues singer's creative sweat to the symbol of payola, who hypes the novelty song into commercial success and leaves the artist in a quandry. Does he stick with his art, thus forgoing the first real recognition he's ever had, or does he pander to popular taste?

The question is loaded, of course. "Ida Red" was Chuck Berry's music as much as "Wee Wee Hours," which in retrospect seems rather uninspired. In fact, maybe the integrity problem went the other way. Maybe Johnson was afraid that the innovations of "Ida Red"--country guitar lines adapted to blues-style picking, with the ceaseless legato of his own piano adding rhythmic excitement to the steady backbeat--were too far out to sell. What happened instead was that Berry's limited but brilliant vocabulary of guitar riffs quickly came to epitomize rock 'n' roll. Ultimately, every great white guitar group of the early Sixties imitated Berry's style, and Johnson's piano technique was almost as influential. In other words, it turned out that Berry and Johnson weren't basically bluesmen at all. Through some magic combination of inspiration and cultural destiny, they had hit upon something more contemporary than blues, and a young audience, for whom the Depression was one more thing that bugged their parents, understood this better than the musicians themselves. Leonard Chess simply functioned as a music businessman should, though only rarely does one combine the courage and insight (and opportunity) to pull it off, even once. Chess became a surrogate audience, picking up on new music and making sure that it received enough exposure for everyone else to pick up on it, too.

Obviously, Chuck Berry wasn't racked with doubt about artistic compromise. A good blues single usually sold around 10,000 copies and a big rhythm and blues hit might go into the hundreds of thousands, but "Maybellene" probably moved a million, even if Chess never sponsored the audit to prove it. Berry had achieved a grip on the white audience and the solid future it could promise, and, remarkably, he had in no way diluted his genius to do it. On the contrary, that was his genius. He would never have fulfilled himself if he hadn't explored his relationship to the white world--a relationship which was much different for him, an urban black man who was used to machines and had never known brutal poverty, than it was for, say, Muddy Waters.

Berry was the first blues-based performer to successfully reclaim guitar tricks that country and western innovators had appropriated from black people and adapted to their own uses 25 or 50 years before. By adding blues tone to some fast country runs, and yoking them to a rhythm and blues beat and some unembarrassed electrification, he created an instrumental style with biracial appeal. Alternating guitar chords augmented the beat while Berry sang in an insouciant tenor that, while recognizably Afro-American in accent, stayed clear of the melisma and blurred overtones of blues singing, both of which enter only at carefully premeditated moments. His few detractors still complain about the repetitiveness of this style, but they miss the point. Repetition without tedium is the backbone of rock and roll, and the components of Berry's music proved so durable that they still provoke instant excitement at concerts durable that they still provoke instant excitement at concerts two decades later. And in any case, the instrumental repetition was counterbalanced by unprecedented and virtually unduplicated verbal variety.

Chuck Berry is the greatest rock lyricist this side of Bob Dylan, and sometimes I prefer him to Dylan. Both communicate an abundance of the childlike delight in linguistic discovery that page poets are supposed to convey and too often don't, but Berry's most ambitious lyrics, unlike Dylan's, never seem pretentious or forced. True, his language is ersatz and barbaric, full of mispronounced foreignisms and advertising coinages, but then, so was Whitman's. Like Whitman, Berry is excessive because he is totally immersed in America--the America of Melville and the Edsel, burlesque and installment-plan funerals, pemmican and pomade. Unlike Whitman, though, he doesn't quite permit you to take him seriously--he can't really think it's pronounced "a la carty," can he? He is a little surreal. How else can a black man as sensitive as Chuck Berry respond to the affluence of white America--an affluence suddenly his for the taking.

Chuck Berry is not only a little surreal but also a little schizy; even after he committed himself to rock 'n' roll story songs, relegating the bluesman in him to B sides and album fillers, he found his persona split in two. In three of the four singles that followed "Maybellene," he amplified the black half of his artistic personality, the brown-eyed handsome man who always came up short in his quest for the small-time hedonism American promises everyone. By implication, Brown Eyes' sharp sense of life's nettlesome and even oppressive details provided a kind of salvation by humor, especially in "Too Much Monkey Business," a catalog of hassles that included work, school and the army. But the white teenagers who were the only audience with the cultural experience to respond to Berry's art weren't buying this kind of salvation, not en masse. They wanted something more optimistic and more specific to themselves; of the four singles that followed "Maybellene," only "Roll Over Beethoven," which introduced Berry's other half, the rock 'n' roller, achieved any real success. Chuck got the message. His next release, "School Day," was another complaint song, but this time the complaints were explicitly adolescent and were relieved by the direct action of the rock 'n' roller. In fact, the song has been construed as a prophecy of the Free Speech Movement: "Close your books, get out of your seat/Down the halls and into the street."

It has become a cliché to attribute the rise of rock and roll to a new parallelism between white teenagers and black Americans; a common "alienation" and even "suffering" are often cited. As with most clichés, this one has its basis in fact--teenagers in the Fifties certainly showed an unprecedented consciousness of themselves as a circumscribed group, though how much that had to do with marketing refinements and how much with the Bomb remains unresolved. In any case, Chuck Berry's history points up the limits of this notion. For Berry was closer to white teenagers both economically (that reform school stint suggests a JD exploit, albeit combined with a racist judicial system) and in spirit (he shares his penchant for youthfulness with Satchel Paige but not Henry Aaron, with Leslie Fiedler but not Norman Podhoretz) than the average black man. And even at that, he had to make a conscious (not to say calculated) leap of the imagination to reach them, and sometimes fell short.

Although he scored lots of minor hits, Chuck Berry made only three additional Billboard Top Ten singles in the Fifties--"Rock and Roll Music," "Sweet Little Sixteen," and "Johnny B. Goode"--and every one of them ignored Brown Eyes for the assertive, optimistic, and somewhat simpleminded rock 'n' roller. In a pattern common among popular artists, his truest and most personal work didn't flop, but it wasn't overwhelmingly popular either. For such artists, the audience can be like a drug. A little of it is so good for them that they assume a lot of it would be even better, but instead the big dose saps their autonomy, often so subtly that they don't notice it. For Chuck Berry, the craving for overwhelming popularity proved slightly dangerous. At the same time that he was enlivening his best songs with faintly Latin rhythms, which he was convinced were the coming thing, he was also writing silly exercises with titles like "Hey Pedro." Nevertheless, his pursuit of the market also worked a communion with his audience, with whom he continued to have an instinctive rapport remarkable in a 30-year-old black man. For there is also a sense in which the popular artist is a drug for the audience, and a doctor, too--he has to know how much of his vital essence he can administer at one time, and in what compound.

The reason Berry's rock 'n' roller was capable of such insightful excursions into the teen psyche--"Sweet Little Sixteen," a celebration of everything lovely about fanhood; or "Almost Grown," a basically unalianated first-person expression of teen rebellion that Sixties youth-cult pundits should have taken seriously--was that he shared a crucial American value with the humorous Brown Eyes. That value was fun. Even among rock critics, who ought to know better, fun doesn't have much of a rep, so that they commiserate with someone like LaVern Baker, a second-rate blues and gospel singer who felt she was selling her soul every time she launched into a first-rate whoop of nonsense like "Jim Dandy" or "Bumble Bee." But fun was what adolescent revolt had to be about--inebriated affluence versus the hangover of the work ethic. It was the only practicable value in the Peter Pan utopia of the American dream. Because black music had always thrived on exuberance--not just the otherworldly transport of gospel, but the candidly physical good times of great pop blues singers like Washboard Sam, who is most often dismissed as a lightweight by the heavy blues critics--it turned into the perfect vehicle for generational convulsion. Black musicians, however, had rarely achieved an optimism that was cultural as well as personal--those few who did, like Louis Armstrong, left themselves open to charges of Tomming. Chuck Berry never Tommed. The trouble he'd seen just made his sly, bad-boy voice and the splits and waddles of his stage show that much more credible.

Then, late in 1959, fun turned into trouble. Berry had imported a Spanish-speaking Apache prostitute he'd picked up in El Paso to check hats in his St. Louis nightclub, and then fired her. She went to the police, and Berry was indicted under the Mann Act. After two trials, the first so blatantly racist that it was disallowed, he went to prison for two years. When he got out, in 1964, he and his wife had separated, apparently a major tragedy for him. The Beatles and the Rolling Stones had paid him such explicit and appropriate tribute that his career was probably in better shape after his jail term than before, but he couldn't capitalize. He had a few hits--"Nadine" and "No Particular Place to Go" (John Lennon is one of the many who believe they were written before he went in)--but the well was dry. Between 1965 and 1970 he didn't release one-even passable new song, and he died as a recording artist.

In late 1966, Berry left Chess for a big advance from Mercury Records. The legends of his money woes at Chess are numerous, but apparently the Chess brothers knew how to record him--the stuff he produced himself for Mercury was terrible. Working alone with pickup bands, he still performed a great deal, mostly to make money for Berry Park, a recreation haven 30 miles from St. Louis. And as he toured, he found that something had happened to his old audience--it was getting older, with troubles of its own, and it dug blues. At auditoriums like the Fillmore, where he did a disappointing live LP with the Steve Miller Blues Band, Chuck was more than willing to stretch out on a blues. One of his favorites was from Elmore James: "When things go wrong, wrong with you, it hurts me too."

By 1970, he was back home at Chess, and suddenly his new audience called forth a miracle. Berry was a natural head--no drugs, no alcohol--and most of his attempts to cash in on hippie talk had been embarrassments. But "Tulane," one of his greatest story songs, was the perfect fantasy. It was about two dope dealers: "Tulane and Johnny opened a novelty shop/ Back under the counter was the cream of the crop." Johnny is nabbed by narcs, but Tulane, his girlfriend, escapes, and Johnny confidently predicts that she will buy off the judge. Apparently she does, for there is a sequel, a blues. In "Have Mercy Judge," Johnny has been caught again, and this time he expects to be sent to "some stony mansion." Berry devotes the last stanza to Tulane, who is "too alive to live alone." The last line makes me wonder just how he felt about his own wife when he went to prison: "Just tell her to live, and I'll forgive her, and even love her more when I come back home."

Taken together, the two songs are Berry's peak, although Leonard Chess would no doubt have vetoed the vocal double-track on "Tulane" that blurs its impact a bit. Remarkably, "Have Mercy Judge" is the first important blues Berry ever wrote, and like all his best work it isn't quite traditional, utilizing an abc line structure instead of the usual aab. Where did it come from? Is it unreasonable to suspect that part of Berry really was a bluesman all along, and that this time, instead of him going to his audience, his audience came to him and provided the juice for one last masterpiece?

Berry's career would appear closed. He is a rock and roll monument at 50, a pleasing performer whose days of inspiration are over. Sometime in the next 30 years he will probably die, and while his songs have already stuck in the public memory a lot longer than Washboard Sam's, it's likely that most of them will fade away too. So is he, was he, will he be a great artist? It won't be we judging, but perhaps we can think of it this way. Maybe the true measure of his greatness was not whether his songs "lasted"--a term which as of now means persisted through centuries instead of decades--but that he was one of the ones to make us understand that the greatest thing about art is the way it happens between people. I am grateful for aesthetic artifacts, and I suspect that a few of Berry's songs, a few of his recordings, will live on in that way. I only hope that they prove too alive to live alone. If they do, and if by some mishap Berry's name itself is forgotten, that will nevertheless be an entirely apposite kind of triumph for him.

Discography

"Maybellene" (Chess 1604; * 5, r* 1, 1955).

"Thirty Days" (Chess 1610; r* 8, 1955).

"No Money Down" (Chess 1615; r* 11, 1956).

"Roll Over Beethoven" (Chess 1626; r* 7, *29, 1956).

"Too Much Monkey Business" b/w "Brown Eyed Handsome Man" (Chess 1635; r* 7, 1956).

"School Day" (Chess 1653; r* 1, *5, 1957).

"Oh Baby Doll" (Chess 1664; * 57, 1957).

"Rock and Roll Music" (Chess 1671; * 8, r* 6, 1957).

"Sweet Little Sixteen" (Chess 1683; r* 1, *2, 1958).

"Johnny B. Goode" (Chess 1691; r* 5, * 8, 1958).

"Carol" (Chess 1700; r* 12, * 18, 1958).

"Sweet Little Rock and Roll" (Chess 1709; r* 13, * 47, 1958).

"Anthony Boy" (Chess 1716; * 60, 1959).

"Almost Grown" (Chess 1722; r* 3, * 32, 1959).

"Back in the U.S.A." (Chess 1729; r* 16, * 37, 1959).

"Too Pooped to Pop" (Chess 1747; r* 18, * 42, 1960).

"Nadine" (Chess 1883; * 23, 1964).

"No Particular Place to Go" (Chess 1898; * 10, 1964).

"You Never Can Tell" (Chess 1906; * 14, 1964).

"Little Marie" (Chess 1912; * 54, 1964).

"Promised Land" (Chess 1916; * 41, 1964).

"My Ding-a-Ling" (Chess 2131; * 1, 1972).

"Reelin' and Rockin'" (Chess 2136; * 27, 1972).

(Chart positions compiled from Joel Whitburn's Record Research, based on Billboard Pop chart, unless otherwise indicated; r* = position on Billboard Rhythm and Blues chart.)

The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll, 1976

From his songwriting and lyrics, to his guitar playing and stage antics, perhaps nobody else short of Elvis Presley was as influential on the young Beatles as Chuck Berry. As John Lennon once put it, "When I hear rock, good rock, the calibre of Chuck Berry, I just fall apart and I have no other interest in life. The world could be ending if rock 'n' roll is playing" (Anthology, page 11). Where Presley's strength was as a performer, as an interpretive artist, Berry was more creative and multi-dimensional: He wrote, performed, and recorded his own words and music.

Throughout the Quarrymen/Beatles' existence, they played a total of at least 15 Chuck Berry songs in their live shows (as dictated in Lewisohn, page 361-65), listed here in chronological order.

- "Roll Over Beethoven", 1957-64

- "Sweet Little Sixteen", 1957-62

- "Johnny B. Goode", 1958-62

- "Maybellene", 1959-61

- "Rock and Roll Music", 1959-66

- "Almost Grown", 1960-62

- "Carol", 1960-62

- "Little Queenie", 1960-63

- "Reelin' and Rockin'", 1960-61

- "Thirty Days", 1960-61

- "Vacation Time", 1960-61

- "Memphis, Tennessee", 1960-62

- "Too Much Monkey Business", 1960-62

- "I Got to Find my Baby", 1961-62

- "I'm Talking About You", 1962

Unusually in this series of American Rock 'n' Roll and its influence on the Beatles, Beatles recordings survive of all but one of those 15 tunes.

In addition to 8 years' of stage performances, the Beatles also officially recorded and released "Roll Over Beethoven" on With the Beatles.

A

live recording of the same song (with Lennon singing lead) was also

made on an unknown date (it must have been no later than 1961 because

that's when Harrison took over lead vocals) and later released on the

album The Beatles Live at the BBC...

...

and a different version (with Harrison singing lead) was recorded on an

unknown date (must have been no earlier than 1961) and later released

on the album On Air – Live At The BBC Volume 2, heard in the YouTube video below from 30:07-32:29.

The

Beatles also played two sets at Carnegie Hall in New York City on 12

February 1964, opening both with "Roll Over Beethoven". Unfortunately,

neither was recorded.

"Sweet Little Sixteen" was recorded twice by the Beatles. First at the Star Club in Hamburg in 1962 and released on the album Live! At the Star Club...

"Sweet Little Sixteen" was recorded twice by the Beatles. First at the Star Club in Hamburg in 1962 and released on the album Live! At the Star Club...

... and second on 10 July 1963 at the Aeolian Hall in London for the radio show Pop Goes the Beatles. This latter recording was included on the album The Beatles Live at the BBC.

Lennon also recorded and released the song on his 1975 album Rock 'n' Roll.

Many Berry tunes were included on the 1994 album The Beatles Live at the BBC, including "Johnny B Goode", "Roll Over Beethoven", "Carol", "Too Much Monkey Business" , "I Got to Find my Baby", and "Memphis, Tennessee".

This last number was recorded by the Beatles on New Year's Day 1962, as part of their ill-fated Decca audition.

Many Berry tunes were included on the 1994 album The Beatles Live at the BBC, including "Johnny B Goode", "Roll Over Beethoven", "Carol", "Too Much Monkey Business" , "I Got to Find my Baby", and "Memphis, Tennessee".

This last number was recorded by the Beatles on New Year's Day 1962, as part of their ill-fated Decca audition.

After

"Roll Over Beethoven", the only other Berry song to be released on an