AS OF JANUARY 13, 2023 FIVE HUNDRED MUSICAL ARTISTS HAVE BEEN FEATURED IN THE SOUND PROJECTIONS MAGAZINE THAT BEGAN ITS ONLINE PUBLICATION ON NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

THE 500th AND FINAL MUSICAL ARTIST ENTRY IN THIS NOW COMPLETED EIGHT YEAR SERIES WAS POSTED ON THIS SITE ON SATURDAY, JANUARY 7, 2023.ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2015/01/wayne-shorter-b-august-25-1933.html

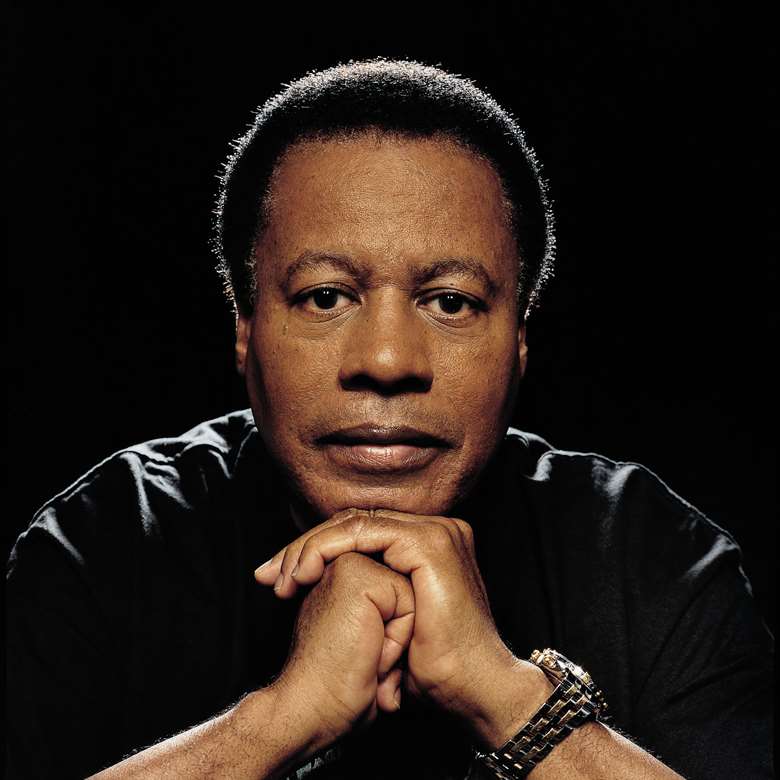

PHOTO: WAYNE SHORTER (1933-2023)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/wayne-shorter-mn0000250435

Wayne Shorter

(1933-2023)

Biography by Richard S. Ginell

Wayne Shorter was one of jazz's leading figures in the late 20th and early 21st centuries as both a composer and saxophonist. Though indebted to John Coltrane, with whom he practiced in the mid-'50s, Shorter developed his own voice and style on the tenor horn, retaining the tough tone quality and intensity and, in later years, adding elements of funk. On soprano, Shorter was almost another player entirely, his lovely tone attuned more to lyrical thoughts, his choice of notes more spare. As a composer, he wrote complex, long-limbed tunes, many of which are now standards. On his '60s albums for Blue Note, most notably Juju and Night Dreamer, the composer and the saxophone stylist meet. He co-founded Weather Report in 1970 and through 1986 released Grammy-winning albums. He issued jazz-funk recordings for Columbia and Verve in the late '80s and early '90s, including Joy Ryder and High Life. On 2002's Footprints Live!, and 2003's Alegria, Shorter showcased a new acoustic quartet dedicated to performing his compositions. As he entered his eighties, Shorter focused on impressively complex projects, including 2018's Emanon, a graphic novel combined with four-part studio suite and 2021's opera based on Greek myths titled Iphigenia.

Shorter started playing the clarinet at 16 but switched to tenor sax before entering New York University in 1952. After graduating with a BME in 1956, he played with Horace Silver for a short time until he was drafted into the Army for two years. Once out of the service, he joined Maynard Ferguson's band, meeting Ferguson's pianist Joe Zawinul in the process. The following year (1959), Shorter joined Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, where he remained until 1963, eventually becoming the band's music director. During the Blakey period, Shorter also made his debut on record as a leader, cutting several albums for Chicago's Vee-Jay label. After a few prior attempts to hire him away from Blakey, Miles Davis finally convinced Shorter to join his quintet in September 1964.

Staying with Davis until 1970, Shorter became one of the band's most prolific composer, contributing tunes like "E.S.P.," "Pinocchio," "Nefertiti," "Sanctuary," "Footprints," "Fall," and the signature description of Davis, "Prince of Darkness." While playing through Davis' transition from loose, post-bop acoustic jazz into electronic jazz-rock, Shorter also took up the soprano in late 1968, an instrument that turned out to be more suited to riding above the new electronic timbres than the tenor. As a prolific solo artist for Blue Note during this period, Shorter expanded his palette from hard bop almost into the atonal avant-garde, with fascinating excursions into jazz-rock territory toward the turn of the decade.

In November 1970, Shorter teamed up with old cohort Joe Zawinul and Miroslav Vitous to form Weather Report where, after a fierce start, Shorter's playing grew mellower and more consciously melodic in order to fit into Zawinul's concepts. By now he was playing mostly on soprano, though the tenor would re-emerge toward the end of the group's run. Shorter's solo career was mostly put on hold during the Weather Report days, though 1975's Native Dancer was an attractive side trip into Brazilian-American tropicalismo made in tandem with Milton Nascimento. Shorter also revisited the past in the late '70s by touring with Freddie Hubbard and ex-Davis sidemen Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams as V.S.O.P.

Shorter finally left Weather Report in 1985. Still committed to electronics and fusion, his recorded compositions from the period feature welcoming rhythms and harmonically complex arrangements. After three Columbia albums between 1986 and 1988 -- Atlantis, Phantom Navigator, and Joy Ryder -- and a tour with Santana (represented by the 2005 album Montreux 1988), he lapsed into silence, emerging again in 1992 with Wallace Roney and the V.S.O.P. rhythm section in the "A Tribute to Miles" band. In 1994, now on Verve, Shorter released High Life, an engaging electric collaboration with keyboardist Rachel Z.

He continued playing concerts with a wide range of groups and appeared on a number of recordings as a guest including the Rolling Stones' Bridges to Babylon in 1997 and Herbie Hancock's Gershwin's World in 1998. In 2001, he was back with Hancock for Future 2 Future and on Marcus Miller's M². Footprints Live! was released in 2002 under his own name with a new band that included pianist Danilo Pérez, bassist John Patitucci, and drummer Brian Blade, followed by Alegria in 2003 and Beyond the Sound Barrier in 2005.

Though absent from recording, Shorter continued to tour regularly with the same quartet after 2005. They re-emerged to record again in February of 2013 with a live outing from their 2011 tour. Without a Net, his first recording for Blue Note in 43 years, was issued in February of 2013 as a precursor to his 80th birthday. Just after that release, the Wayne Shorter Quartet performed four of the leader's compositions with the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra at Carnegie Hall in New York City. Shorter immediately brought the quartet and orchestra into the studio to record those same four pieces: "Pegasus," "Prometheus Unbound," "Lotus," and "The Three Marias," as a unified suite. The title of this four-composition orchestral suite is also Shorter’s title character for the graphic novel Emanon, or "no name" spelled backward. Each of the four movements has a corresponding theme in a graphic novel penned by Shorter and Monica Sly and illustrated by Randy DeBurke. It draws inspiration from the concept of a multiverse (where numerous universes co-exist simultaneously) and features a character named Emanon, an action-hero proxy of Shorter, a comic book aficionado since he was a boy. The story alludes to dystopian oppression and was clearly informed by the saxophonist's Buddhist studies. All told, the music -- performed by the quartet with and without the chamber orchestra -- was recorded live in London as well as in the studio, creating a triple album accompanied by the 84-page graphic novel. Emanon was issued in September of 2018, just after Shorter's 85th birthday. His next project proved just as ambitious, writing an opera based around the myth of Iphigenia, a Greek princess. Shorter co-created the work with librettist esperanza spalding and set designer Frank Gehry. The work merged jazz and classical themes and premiered in New York at the end of 2021. The following year Candid released Live at the Detroit Jazz Festival. Recorded at the 2017 event, it featured Shorter in a one-off quartet setting that included drummer Terri Lyne Carrington, bassist/vocalist esperanza spalding, and Argentine pianist Leo Genovese. It proved to be the last music issued during his lifetime, as he passed away in March of 2023 at the age of 89.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/wayne-shorter/

Wayne Shorter

Born in Newark, New Jersey on August 25, 1933, Wayne Shorter had his first great jazz epiphany as a teenager: “I remember seeing Lester Young when I was 15 years old. It was a Norman Granz Jazz at the Philharmonic show in Newark and he was late coming to the theater. Me and a couple of other guys were waiting out front of the Adams Theater and when he finally did show up, he had the pork pie hat and everything. So then we were trying to figure out how to get into the theater from the fire escape around the back. We eventually got into the mezzanine and saw that whole show — Stan Kenton and Dizzy Gillespie bands together on stage doing ‘Peanut Vendor,’ Charlie Parker with strings doing ‘Laura’ and stuff like that. And Russell Jacquet…Ilinois Jacquet. He was there doing his thing. That whole scene impressed me so much that I just decided, ‘Hey, man, let me get a clarinet.’ So I got one when I was 16, and that’s when I started music.

Switching to tenor saxophone, Shorter formed a teenage band in Newark called The Jazz Informers. While still in high school, Shorter participated in several cutting contests on Newark’s jazz scene, including one memorable encounter with sax great Sonny Stitt. He attended college at New York University while also soaking up the Manhattan jazz scene by frequenting popular nightspots like Birdland and Cafe Bohemia. Wayne worked his way through college by playing with the Nat Phipps orchestra. Upon graduating in 1956, he worked briefly with Johnny Eaton and his Princetonians, earning the nickname “The Newark Flash” for his speed and facility on the tenor saxophone.

Just as he was beginning making his mark, Shorter was drafted into the Army. “A week before I went into the Army I went to the Cafe Bohemia to hear music, I said, for the last time in my life. I was standing at the bar having a cognac and I had my draft notice in my back pocket. That’s when I met Max Roach. He said, ‘You’re the kid from Newark, huh? You’re The Flash.’ And he asked me to sit in. They were changing drummers throughout the night, so Max played drums, then Art Taylor, then Art Blakey. Oscar Pettiford was on cello. Jimmy Smith came in the door with his organ. He drove to the club with his organ in a hearse. And outside we heard that Miles was looking for somebody named Cannonball. And I’m saying to myself, ‘All this stuff is going on and I gotta go to the Army in about five days!’”

Following his time in the service, Shorter had a brief stint in 1958 with Horace Silver and later played in the house band at Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem. It was around this time that Shorter began jamming with fellow tenor saxophonists John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins. In 1959, Shorter had a brief stint with the Maynard Ferguson big band before joining Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers in August of that year. He remained with the Jazz Messengers through 1963, becoming Blakey’s musical director and contributing several key compositions to the band’s book during those years. Shorter made his recording debut as a leader in 1959 for the Vee Jay label and in 1964 cut the first of a string of important recordings for the Blue Note label.”

In 1964 Miles Davis invited Wayne to go on the road. He joined Herbie Hancock (piano), Tony Williams (drums) and Ron Carter (bass). This tour turned into a 6 year run with Davis in which he recorded a number albums with him. Along with Davis, he helped craft a sound that changed the face of music In his autobiography, the late Miles Davis said about Wayne…“Wayne is a real composer…he knew that freedom in music was the ability to know the rules in order to bend them to your satisfaction and taste…” In his time with Miles he crafted what have become jazz standards like “Nefertiti,” “E.S.P.,” “Pinocchio,” “Sanctuary,” “Fall” and “Footprints.

Simultaneous with his time in the Miles Davis quintet, Shorter recorded several albums for Blue Note Records, featuring almost exclusively his own compositions, with a variety of line-ups, quartets and larger groups including Blue Note favourites such as Freddie Hubbard. His first Blue Note album (of nine in total) was Night Dreamer recorded at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in 1964 with Lee Morgan, McCoy Tyner, Reggie Workman and Elvin Jones. The later album The All Seeing Eye was a free-jazz workout with a larger group, while Adam’s Apple of 1966 was back to carefully constructed melodies by Shorter leading a quartet. Then a sextet again in the following year for Schizophrenia with his Miles Davis band mates Hancock and Carter plus trombonist Curtis Fuller, alto saxophonist/flautist James Spaulding and strong rhythms by drummer Joe Chambers. These albums have recently been remastered by Rudy Van Gelder.

In 1970, Shorter co-founded the group Weather Report with keyboardist and Miles Davis alum, Joe Zawinul. It remained the premier fusion group through the ’70s and into the early ’80s before disbanding in 1985 after 16 acclaimed recordings, including 1980’s Grammy Award-winning double-live LP set, 8:30. Shorter formed his own group in 1986 and produced a succession of electric jazz albums for the Columbia label — 1986’s Atlantis, 1987’s Phantom Navigator, 1988’s Joy Ryder. He re-emerged on the Verve label with 1995’s High Life. After the tragic loss of his wife in 1996 (she was aboard the ill-fated Paris-bound flight TWA 800), Shorter returned to the scene with 1997’s 1+1, an intimate duet recording with pianist and former Miles Davis quintet bandmate Herbie Hancock. The two spent 1998 touring as a duet.

After Weather Report, Shorter continued to record and lead groups in jazz fusion styles, including touring in 1988 with guitarist Carlos Santana, who appeared on the last Weather Report disc This is This! In 1989, he scored a hit on the rock charts, playing the sax solo on Don Henley’s song “The End of the Innocence” and also produced the album “Pilar” by the Portuguese singer-songwriter Pilar Homem de Melo.

In 1995, Shorter released the album High Life, his first solo recording for seven years. It was also Shorter’s debut as a leader for Verve Records. Shorter composed all the compositions on the album and co-produced it with the bassist Marcus Miller. High Life received the Grammy Award for best Contemporary Jazz Album in 1997.

Shorter would work with Hancock once again in 1997, on the much acclaimed and heralded album 1+1. The song “Aung San Suu Kyi” (named for the Burmese pro-democracy activist) won both Hancock and Shorter a Grammy Award. In 2009, he was announced as one of the headline acts at the Gnaoua World Music Festival in Essaouira, Morocco.

By the summer of 2001, Wayne began touring as the leader of a talented young lineup featuring pianist Danilo Perez, bassist John Patitucci and drummer Brian Blade, each a celebrated recording artist and bandleader in his own right. The group’s uncanny chemistry was well documented on 2002’s acclaimed Footprints Live! Shorter followed in 2003 with the ambitious Alegria, an expanded vision for large ensemble which earned him a Grammy Award. In 2005, Shorter released the live Beyond the Sound Barrier which earned him another Grammy Award. “It’s the same mission... fighting the good fight,” he said. “It’s making a statement about what life is, really. And I’m going to end the line with it.”

http://panopticonreview.blogspot.com/2013/08/its-time-to-celebrate-life-and-work-of.html

Sunday, August 25, 2013

It's Time To Celebrate the Life and Work of a GIANT in Our Midst: Today Marks the 80th Birthday of Legendary Musician and Composer Wayne Shorter

First, full disclosure: I am a flatout Wayne Shorter fanatic and a shamelessly devoted acolyte of him and his glorious music and have been for well over 40 years now. Widely considered by many musicians, composers, fans, and critics throughout the globe as one of the most captivating, significant, and downright inspiring artists of our time, Mr. Shorter has been active professionally for over six decades and has been recording since 1957. An absolutely essential and leading member of two of the most extraordinary ensembles in modern Jazz history Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers (of which he was the major composer and musical director from 1959-1964) and Miles Davis's legendary "second great quintet" for which Wayne played and composed from 1964-1970, Shorter not only led and recorded with many outstanding groups of his own but also went on to be the cofounder with pianist/composer Joe Zawinul of the very popular Jazz fusion ensemble Weather Report (1971-1985). Since then Shorter has continued over the past 30 years to display his masterly and virtuosic talents in a wide range of musical styles and genres and has been a mentor and major influence for an entire generation of musicians and composers throughout the world. In loving tribute to this living legend whose music as both multi-instrumentalist and composer alike is as strong or stronger today as it has ever been (please see and hear his stunning critically acclaimed and bestselling 2013 recording "Without A Net" on the famed Blue Note label for the wonderful evidence of that fact), click on, check out and enjoy listening to and watching Wayne and his equally legendary colleagues in the following video links to a wide range of Shorter's music since the early 1960s...LONG LIVE THE MAN AND HIS MUSIC...

Kofi

Wayne Shorter at a festival in January 2013

FROM THE PANOPTICON REVIEW ARCHIVES

(Originally posted on February 9, 2013):

Saturday, February 9, 2013

Wayne Shorter: The Living Legacy of a Great Musician, Composer, and Philosopher

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/03/arts/music/wayne-shorters-new-album-is-without-a-net.html?ref=arts&_r=0&pagewanted=all

"I knew Wayne Shorter first in Newark where we were both, malevolently, born. He was one of the two "weird" Shorter brothers that people mentioned occasionally, usually as a metaphorical reference, "...as weird as Wayne." --Leroi Jones, "Introducing Wayne Shorter", Jazz Review, 1959

“We have to beware the trapdoors of the self. You think you’re the only one that has a mission, and your mission is so unique, and you expound this missionary process over and over again with something you call a vocabulary, which in itself becomes old and decrepit.”

--Wayne Shorter, 2013

All,

A Great Artist. A Great Musician. A Great Composer. A Great Human Being (And a Bad Muthafucka!). My eternal goal remains to be fortunate enough to become "as weird as Wayne"...

Kofi

by NATE CHINEN

January 31, 2013

New York Times

THE STANDARD LINE on Wayne Shorter is that he’s the greatest living composer in jazz, and one of its greatest saxophonists. He would like you to forget all of that. Not the music, or his relationship to it, but rather the whole notion of pre-eminence, with its granite countenance and fixed coordinates. “We have to beware the trapdoors of the self,” he said recently.

“You think you’re the only one that has a mission,” he went on, “and your mission is so unique, and you expound this missionary process over and over again with something you call a vocabulary, which in itself becomes old and decrepit.” He laughed sharply.

Mr. Shorter will turn 80 this year. Decrepitude hasn’t had a chance to catch up to him. Last week he appeared at Carnegie Hall as a featured guest with the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, which played several of his compositions. On Tuesday “Without a Net,” easily the year’s most anticipated jazz album, will become his first release on Blue Note in more than four decades. And next Saturday he’ll be at the Walt Disney Concert Hall with the Los Angeles Philharmonic for the premiere of “Gaia,” which he wrote as a showcase for the bassist and singer Esperanza Spalding.

He hasn’t accrued this late-inning momentum alone. The vehicle for most of Mr. Shorter’s recent activity, including the orchestral work, is his superlative quartet with Danilo Pérez on piano, John Patitucci on bass and Brian Blade on drums. A band of spellbinding intuition, with an absolute commitment to the spirit of discovery, it has had an incalculable influence on the practice of jazz in the 21st century — and not necessarily for the same reasons that established Mr. Shorter’s legend in the 20th.

Since the emergence of the quartet, which released its first album on Verve in 2002, jazz’s aesthetic center has moved perceptibly: away from the hotshot soloist and toward a more collectivist, band-driven ideal. There has also been an unusual amount of dialogue between jazz’s tradition-minded base camp and its expeditionary outposts, where conventions exist to be challenged.

Mr. Shorter’s working band is far from the only one to embody these principles during the past decade, but it has been the most acclaimed and widely heard. Traces of its style can be detected in other groups, including those led by the saxophonist Chris Potter and the trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire. Its slippery methodology has also taken root in the conservatory, and not just at the Berklee College of Music, where Mr. Pérez is on the faculty, or at the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz, where Mr. Shorter is a resident guru.

“The students are very familiar with that quartet,” said Doug Weiss, who teaches a popular Wayne Shorter ensemble class at the New School for Jazz and Contemporary Music. “They come in having heard the way that band plays together, and a lot of them have no idea what’s going on, and that’s why they’re there.”

So in addition to Mr. Shorter’s body of work — his terse and insinuative compositions, which have been closely studied by jazz musicians for decades — this newer generation has also had the opportunity to grapple with his elusive philosophy of play.

Once, in an interview, Mr. Shorter was asked to account for his pursuit of music above other art forms. He replied that music has an inherent sense of velocity and mystery. It would be hard to find a more concise distillation of his priorities as a bandleader.

“When we go out onstage we always start from nothing,” said Mr. Patitucci by phone from Mr. Pérez’s native Panama, where the quartet headlined a jazz festival last month. “So anybody can spin the wheels in a certain direction, and then we develop those themes.”

What follows isn’t free jazz, exactly, though it uses some of the same tools. “It’s spontaneous composition,” Mr. Patitucci said, “with counterpoint and harmony and lyricism. All of those values are still there. It’s just being pressurized into milliseconds.”

Mr. Shorter framed the idea as an image: “We don’t count how much water there is in a wave when we see the ocean.” He was on the couch of a hotel suite overlooking Central Park South, during one of his recent visits from Los Angeles, where he lives. That evening he would perform at a gala for the David Lynch Foundation, along with the pianist Herbie Hancock, his former partner in the Miles Davis Quintet. He wore dress loafers and a fleece pullover embroidered with the logo of Soka Gakkai International, the Nichiren Buddhist organization to which he and Mr. Hancock belong.

A scheduled interview began with an unscheduled interruption: Ms. Spalding — who won the Grammy for best new artist in 2011, and was also booked at the gala — dropped by with the Argentine pianist Leo Genovese. For all of her success Ms. Spalding still belongs to the demographic that grew up with the notion of Wayne as sage: she and Mr. Genovese were there simply to give him a hug.

Mr. Shorter is a notoriously elliptical conversationalist, prone to cosmic digression and quick-fire allusion. During a spirited two-hour interview he touched on modern art, social politics and science fiction — among the books he produced for inspection was the dystopian “Ready Player One” by Ernest Cline — as well as music and movies, and movie music. “I’m looking at a lot of old silent films now,” he said, “and I listen to the new, hip boy bands. I was checking out some Selena Gomez.” On the subject of jazz, he said pithily, “The word ‘jazz’ to me only means ‘I dare you.’ ”

But he also painted his own jazz narrative in precise strokes, whether it was hearing Charlie Parker at Birdland at the age of 18 — what stuck with him was a quotation of “Petrushka,” the Stravinsky ballet, that Parker sneaked into one solo — or sensing the mortal urgency that burned in John Coltrane, his fellow saxophonist, and in some ways a mentor. And Mr. Shorter made several references to the cryptic wisdom of Miles Davis, slipping each time into an unusually convincing imitation of that trumpeter’s throaty rasp.

Davis’s celebrated quintet of the mid-’60s was one of the most aerodynamically advanced in the history of jazz, and apart from Davis himself Mr. Shorter was its chief in-house designer. One of his signature contributions was “Nefertiti,” a slithery 16-bar tune ambiguously shaded with altered and half-diminished chords.

On record, as the title track to a 1968 album, the song features Davis and Mr. Shorter tracing and retracing its melody while the rhythm section improvises in the background, with all the supple intrigue of a shadow creeping across the landscape. It’s a useful precedent for Mr. Shorter’s current band, which derives much of its dynamism from rhythm-section cohesion within the loosest possible framework.

Another precedent, less obvious, is the transitional band that Davis led before his swerve into jazz-funk, a quintet with Mr. Shorter, the pianist Chick Corea, the bassist Dave Holland and the drummer Jack DeJohnette. A boxed set released last week on Columbia/Legacy, “Live in Europe 1969: The Bootleg Series Vol. 2,” illuminates just how much liberty that group took with its materials, even to the point of feverish abstraction. It never sounds freer than on a concert in Stockholm, attacking three of Mr. Shorter’s compositions: “Paraphernalia,” “Nefertiti” and “Masqualero.”

Two of those have surfaced on Mr. Shorter’s recent albums with the quartet, along with other pieces from a broad swath of his career. “Without a Net,” a compilation of live recordings from 2011, opens with “Orbits,” a theme from the Davis quintet era. It also includes a majestic take on “Plaza Real,” from the songbook of Weather Report, the epochal ’70s fusion band that Mr. Shorter led with Joe Zawinul.

But the provenance of the music takes a back seat to its process, which Mr. Shorter said was meant to herald an ideal of self-actualized communal leadership. “This kind of stuff I’m talking about is a challenge to play onstage,” he allowed, and chuckled. “When Miles would hear someone talking about something philosophical, he would say” — here came the rasp — “ ‘Well, why don’t you go out there and play that?’ One thing we talk about is that to ‘play that’ we have to maybe play music that doesn’t sound like music.”

If that sounds like a Zen riddle, comfort yourself with the knowledge that even Mr. Shorter’s band mates have had to warm to the uncertainty. “It was scary, to be honest,” Mr. Pérez said of his early experience in the quartet. “It was a shock to put myself into a situation where I had no idea what was happening. Even when I listened back, I felt like an outsider: ‘What is that? What key are we in?’ ” He gradually made adjustments, including one to his practice regimen: for two or three hours at a stretch he would watch Tom and Jerry cartoons with the sound muted, making up a score.

The band hasn’t relaxed its pursuit of revelation, which expresses itself in myriad ways: Mr. Pérez’s on-the-fly cadenzas, the unexpected thunderclap of Mr. Blade’s crash cymbal, the dartlike insistence of Mr. Shorter’s improvisational flights. All this remains true even as Mr. Shorter steps up his output as a composer. “He’ll bring in this 10-page piece of music, and it’s gorgeous,” Mr. Patitucci said. “And he’ll say, ‘Just this 16 bars.’ He’s not even attached to what he wrote.”

The center of gravity on “Without a Net” is “Pegasus,” designed to feature Imani Winds, a classical wind ensemble. Through much of that track’s 23 minutes, the woodwinds deftly frame the dramatic fluctuations of Mr. Shorter’s band; at times the two factions achieve a compelling synthesis, advancing a dramatic theme.

It’s horizon-scanning music, but it also features glimpses of the past, like the fanfare from “Witch Hunt,” which led off Mr. Shorter’s landmark 1965 Blue Note album “Speak No Evil.” During his solo in “Pegasus” Mr. Shorter also nods to the old Sonny Rollins tune “Oleo.” Elsewhere on the new album he drops a quotation of the Afro-Cuban bebop standard “Manteca,” and leads the band through a cubist recasting of “Flying Down to Rio,” a movie theme originally sung by Fred Astaire.

“To me there’s no such thing as beginning or end,” Mr. Shorter said. “I always say don’t discard the past completely because you have to bring with you the most valuable elements of experience, to be sort of like a flashlight. A flashlight into the unknown.”

Posted by Kofi Natambu at 2:50 AM

Labels: African American music, Improvisation, Jazz composition, Jazz history, social philosophy, Wayne Shorter

http://archive.li/CSEJg

The Music of Wayne Shorter

by Bruno Råberg

Wayne Shorter is one of the musical geniuses of this century. He ranks among Ellington, Parker, Monk and Coltrane both as an improviser and as a composer. His influence on several generations of musicians is evident and speaks for itself. For nearly three decades he has been a prolific composer, always developing and working with new concepts and ideas. Like Miles Davis he has refused to stagnate and has had the ability to leave music that he loves behind in order to develop and explore. As a saxophonist he has it all, from the relentless swinging tenor with Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers to the lyrical and romantic soprano saxophone on many later recordings. He has during his career always belonged to the foremost and ground-breaking bands at the time: Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers, the legendary Miles Davis Quintet, the late 60's Miles Davis, Weather Report and currently his own Wayne Shorter Group. His own current group is one of the most successful and sought after acts on the jazz scene today.

Shorter was born in Newark, New Jersey, on August 26, 1933. His first creative sparks were not shown in music but in painting and sculpting. He was admitted to the Newark Arts High School and did not start to study music until he was 16. He was given a clarinet from his grandmother and started taking lessons with a local band leader. Soon he was to be exposed to the great jazz masters of the time. He went to hear performances by such acts as Duke Ellington, Thelonius Monk, Stan Kenton, Charlie Parker and just about everybody else that was on the scene at the time. After falling in love with this music he then got a tenor saxophone, switched to the music major during the last year of high school and started a band that he called The Group. He was now completely immersed in transcribing arrangements and compositions, especially from the bands that Dizzy Gillespie led at the time. He claims that the broad range he now has on his soprano comes from playing trumpet parts on his clarinet.

After graduation with honors in music and art from Newark Arts High School, he enrolled at New York University, majoring in music education. During these four years he started to do gigs around New York, sitting in at jam sessions at Birdland and all the jazz clubs that were blooming at the time. Just as he was about to get recognition he was drafted into the Army. He played with the Army band in Washington D.C. and during his stay there played a couple of concerts with Horace Silver's band. After leaving the army things really started to take off for Shorter. One of the most important experiences of Shorter's musical life was about to take place, namely his relationship with John Coltrane. They would practice and jam together, sharing conceptual ideas and even playing gigs together. Coltrane had heard about Shorter and was very exited about his playing, especially since he could relate to the way Shorter was trying new concepts and also stretching the limits of the tenor sax. Coltrane supposedly had said to Shorter that he liked the way he was "scrambling them eggs" referring to Shorter's highly imaginative sheets of sound. They both were practicing from violin and harp etude books in order to play wider leaps and intervals and these wide intervals became one of the trade marks of Shorter's improvisations and compositions. It was around this time Coltrane wrote Giant Steps using a tri-tonic system to break away from the be-bop and standard type of changes. One can hear how Shorter emulated this, and one can hear some clear evidence of Giant Steps soloing patterns in his solo on his composition E.S.P., from the 1964 Miles Davis Quintet album with the same name. Coltrane's influence on the overall mood is also obvious on most of the Blue Note recordings that Shorter did as a leader. Shorter also used Coltrane's rhythm sections or at least part of them on these recordings. The 26-year-old Shorter played with Coltrane one memorable night in December 1958, at Birdland. Among the other musicians were Freddie Hubbard, Cedar Walton and Elvin Jones. Cannonball and Nat Adderly's band were playing opposite Coltrane's band. Shorter says about this gig,"We had a rehearsal at his house, and that night we were playing. Opposite us were Cannonball with his brother Nat. Cannonball and Trane were working with Miles then, but they had time off and they split up and got different bands. Elvin Jones was on drums that night. It was historic; everybody realized it- we tore that place up. Ten years later when I went to California, people were still talking about it.- 'Yeah we heard about it out here, that memorable Monday night at Birdland.' That's when Trane started playing all the new stuff he had written. It was a new wave. 1"Shorter has said about his practicing during this time, "I used to practice about 6 hours a day, play the first thing that came into my head, which was always harder than a regular exercise."2

In 1959 Coltrane was about to leave Miles Davis' band and had been wanting to for a while. He told Shorter if he wanted to do it it was all his. Shorter called Davis only to get the response of "If I need a tenor player I'll get one." Obviously Davis did not know that Coltrane was about to leave his group, and next time he saw Coltrane he told him, "Don't be telling nobody to call me like that, and if you want to quit then just quit, but why don't you do it after we get back from Europe?" 3 Instead Shorter joined Maynard Ferguson's band for a short stint. This was upon recommendation of pianist Joe Zawinul. Zawinul and Shorter were at this time socializing a lot but did not play together other than with Ferguson' band. It would take another 10 years before they started their collaboration in Weather Report. After sitting in one night with Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers Shorter was offered the gig and joined them for a 5 year stint. After being with Blakey for a short while he was offered the gig with Miles Davis but opted to stay with the Jazz Messengers.

Together with Lee Morgan, Shorter formed one of the most formidable front lines at the time. The Messengers was a hard- swinging band driven by the propulsive, down to earth drummer Art Blakey. Even though the music became too limited for Shorter after a while, there is no doubt that it was here he developed a strong connection to the roots of jazz and built the foundation that allowed him to stretch and experiment later on. Shorter became the musical director and his compositions and arrangements would characterize the sound of the Jazz Messengers for the 5 years he was with them. During his stay with Blakey he also recorded several albums as a leader.

In 1964 Shorter left Art Blakey and spent the summer practicing and composing. Miles Davis returned from a tour of Japan and found out that Shorter had left Art Blakey. He then asked everybody in his band to call Shorter and convince him to join the quintet. And so he did. The first engagement was at the Hollywood Bowl in late 1964. "Getting Wayne made me feel good , because with him I just knew some great music was going to happen. And it did; it happened real soon,"4 Miles says in his autobiography. "If I was the inspiration and wisdom and the link for this band, Tony (Williams) was the fire, the creative spark; Wayne was the idea person, the conceptualizer of a whole lot of musical ideas we did; Ron (Carter) and Herbie (Hancock) were the anchors."5 Miles also says: "At first Wayne had been know as free-form player, but playing with Art Blakey for those years and being the band's musical director had brought him back in somewhat. He wanted to play freer than he could in Art's band, but he didn't want to be all the way out, either. Wayne has always been someone who experimented with form instead of someone who did it without form. That's why I thought he was perfect for where I wanted to see the music I played go. Wayne also brought in a kind of curiosity about working with musical rules. If they didn't work, then he broke them, but with a musical sense; he understood that freedom in music was the ability to know the rules in order to bend them to your own satisfaction and taste. Wayne was out there on his own plane, orbiting around his own planet. Everybody else in the band was walking down here on earth. He couldn't do in Art Blakey's band what he did in mine; he just seemed to bloom as a composer when he was in my band. That's why I say he was the intellectual musical catalyst for the band in his arrangement of his musical compositions that we recorded." 6 Shorter said about playing with Miles: "Everyone noticed a difference, it wasn't bish-bash, sock- em-dead routine we had with Blakey, with every solo a climax. With Miles, I felt like a cello, I felt viola, I felt liquid, dot-dash, and colors started really coming..." 7 This quintet dissolved in 1967-68 because Davis was again trying to break new ground. He brought in a lot of different musicians and a period of experimenting took place. Shorter still appeared on Davis' albums as late as 1969. During his stay with Davis he recorded a substantial amount of records as a leader, most of them on Blue Note. It is interesting to note that the music on these recordings although recorded during the same era as the Davis Quintet are much less experimental and stays closer to the jazz tradition. This is with the exception of Etcetera (1965) and the albums recorded after 1968.

In 1970 Shorter formed Weather Report together with Joe Zawinul and Miroslav Vitous. He had played with both in different constellations during 1968-69, with Davis and in his own formations as a leader. Weather Report was to be at the forefront of the jazz fusion era, breaking new ground for 15 years, and a new unique sound was born. He shared the role as composer with Zawinul on the 15 albums that they recorded. His improvisations became almost minimalistic on some of the recordings, since compositions and group playing was the main focus of the group. His ability to think compositionally while improvising, and to say a lot with a few right notes, still makes his solos very interesting. The freedom to stretch out on longer improvisations is evident on their live album 8:30 recorded in 1979.

In 1985 Weather Report and the collaboration with Zawinul came to an end. Shorter started his own band and recorded Atlantis. This was his first album as leader since Native Dancer, a collaboration with Brazilian singer-composer Milton Nascimento that was recorded in 1974. The music on Atlantis was all through-composed, almost a form of jazz-fusion chamber music. It seemed like this was material that he did not get to record with Weather Report and now, not having to compromise, he got to control every aspect of the music. The writing on this album is very complex and utilizes many different compositional techniques. It also has an interesting blend of acoustic and synthesized instruments in the arrangements. There is hardly any improvisation except for short soloistic statements similar to the Weather Report recordings. As with Weather Report though, the same material is opened up for long improvisations in live performances and contains a lot of group interaction. After Atlantis two more albums were released, Phantom Navigator in 1987 and Joy Ryder in 1989. These are similar in style but have more of a high-tech sound, with sequenced drum and keyboard parts.

The Artist and Philosopher

Some of the words that come to mind when trying to describe Wayne Shorter are: mysterious, intuitive, spontaneous, artistic, imaginative, universal, free, black esthetics, naive, swinging, traditional and unpredictable.

The early curiosity and involvement in painting and sculpting is something that became a part of Shorter's artistry throughout his career. The majority of his tunes have very vivid images that go with them. When talking about his compositions Shorter always mentions a particular feeling or mood that he was thinking about when he was writing a particular tune. Also specific movements, shapes and even stories and science-fiction become the script that the composition is based on. Sometimes it is the overall mood and sometimes there is a very specific and more direct relation. An example of the latter would be the tune Lester Left Town (Art Blakey-The Big Beat) which is about Lester Young. Shorter illustrates the way Lester Young walked with the melody line. Shorter says,"He had a way of walking, and the descending chromatic notes, which have a tempo of their own, pictorialize Lester Young walking at a fast pace." 8 The strong igniting role that these images played is evident when Shorter comments on how certain compositions were conceived. He says about Lester Left Town : " I was sort of thinking about the 40's and I was in my 20's when I wrote it. I was thinking, "Lester Young". The writing just went by itself." 9 Another example of a direct physical image used as inspiration is the tune The Last Silk Hat (Atlantis). This tune was written for Nat "King" Cole and specifically his ambidextrousness at playing the piano and singing at the same time. Saying that these images would serve as inspiration for his composing seems like an understatement. Rather, these images seems to be crucial as the creative spark that sets forth the process of composing and stays closely knit to the final product.

On his pivotal album Speak No Evil , recorded in 1964 for Blue Note, Shorter drew on folklore, black magic and legends. About the collection of compositions on this album Shorter says, "I was thinking of misty landscapes with wild flowers and strange, dimly-seen shapes- the kind of places where folklore and legends are born." He goes on. "I'm getting more stimuli from things outside of my self. Before I was concerned with myself, with my ethnic roots, and so forth. But now, and especially from here on, I'm trying to fan out, to concern myself with the universe instead of just my own corner of it." 10 All the compositions on this album have very specific images in mind. Witch Hunt is about the Salem witch burnings. Fee-fi-fo-fum is inspired by a couplet spoken by the giant in the story of Jack and the Beanstalk. About Dance Cadaverous Shorter says, " I was thinking of some of these doctor pictures in which you see a classroom and they're getting ready to work on a cadaver." 11 Speak No Evil is the last part of the saying, see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil "This piece is about caution, be careful about what you say: What comes out of your mouth can cause some horrendous effects or beautiful ones." 12 says Shorter in the liner notes. Shorter's inspiration can also come from more real life experiences as is the case with Infant Eyes , which is a ballad referring to Shorter's daughter, Miyako. Wildflower is simply an ode to a wild flower.

Despite these statements that suggest a departure from the jazz and other black music traditions, the music on Speak No Evil is still imbued with blues and swinging rhythms. The development here does not mean leaving the roots behind but rather expanding the range of influences and emotions. This is of course crucial for any art form if it is to develop and not stagnate.

As an improviser Shorter never succumbs to patterns and practiced "licks". There are many trademarks and melodic materials that he uses in his writing and improvising, but these are motives that are his own and are used in a very flexible manner. He will use quotes from his own solos from 20 years ago in his playing today, but these melodic motives are so strong that although they were improvised at the time they have become part of the composition. His composer and improviser self are very symbiotic and work closely together. His compositions never become contrived and academic but rather seem to spring out like improvised spontaneous phrases that are left alone to grow on their own as much or little as they want. A good example of this is the classic Nefertiti (Nefertiti , Miles Davis Quintet, 1967) which he claims to have written in less than 3-4 minutes. His improvisations are much the same way, especially after he joined Miles Davis and stepped into his own leaving the hard-bop tenor identity behind. He does not force himself or any preconceived ideas on the music. Instead, he has full confidence in himself as a medium for creativity, and lets the music play through him. He also has the prowess to stick to the essence of the song, and not play music that is far removed from the compositions. One can hear the original melody of the composition following his lines like a shadow. He also takes himself and the musical ideas that come out of his instrument very seriously. Every idea is treated with respect and won't be dismissed and hurriedly buried by another unrelated line. Even in his most erratic flurries of sounds he can at any moment state fragments from the melody. As a listener one can feel the sense of cohesion at all times.

In his later works, Atlantis, Phantom Navigator and Joy Ryder, his interest in science-fiction movies and extraterrestrial phenomena are evident. Shorter says about Flagships from Phantom Navigator, "This piece was actually meant to be cinematic. It's a large field, late evening, a big huge UFO descending and hovering over this field. Two children actually starting out to play and getting entangled in something that is totally alien to them, but at the same time, experiencing, from a listening point of view, something that's warm with excitement." He goes on to say, "I wanted to have this piece of music result in anticipation for the future." 13 Forbidden Plan-iT ! from the same album is also the title of a 50's science-fiction movie, the first movie to use an all electronic sound track. From the same album titles like Condition Red and Remote Control are actual movie titles. "Yamanja was inspired by the Brazilian legend of the goddess of the sea." 14 says Shorter about another title.

The early Shorter compositions are stylistically in a typical neo-bop style with 8th note runs in the melody over II-V oriented progressions. There are also many Dom7 passing chords and deceptive resolutions that give them Shorter's distinctive touch. A lot of typical be-bop tunes were written over familiar chord changes from standards. Charlie Parker's Donna Lee was written over the chord changes to Indiana . George Gershwin's I Got Rhythm is another example of a tune that has had hundreds of different melodies written for it. In these cases it was often the familiar harmonic progressions, with logical and clear tonal centers, that gave a composition cohesiveness. The melody could afford to be very flexible and less "catchy" or singable because the harmony provided stability. What Shorter started to do was to have the melody give cohesiveness over unfamiliar, complex, and vagrant harmonic progressions. Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk and others had, of course, already started to compose independently of these familiar chord changes. Monk especially had written very complex progressions. In the light of this one can say that Shorter's compositions were not at this point that ahead of their time or by any means revolutionary. What put them in a class by themselves was Shorter's distinctive personal voice that is even today unmistakable. Shorter further developed this on the albums that he recorded as a leader for Blue Note Records. Tunes like Armageddon, Deluge, Speak No Evil, Witch Hunt and Wild Flower have melodies that are very simple. They have none of the complex 8th note runs and melodic twists typical of 50's be-bop. Instead the melodies are very limited in terms of pitch set and the rhythms are spacious and repetitive. Some of the melodies (Armageddon and Deluge ) stick almost exclusively to a minor pentatonic scale. This scale is also the basis for the blues scale and therefore these tunes have a very "bluesy" character. As a contrast to the simple inside melodic part of the tune there is always a bridge, that provides variation and interest enough to make the composition complete. What also provides variation and makes these compositions very different from earlier writing is the harmony. Underneath these quite singable and simple sounding melodies lie very complex harmonic progressions. What we get is a perfect balance between complexity and simple lyricism. Understanding this relation between melody and harmony is also often the key to learning how to improvise over Shorter's tunes. Just like the melody bridges the distance between the chords, one can improvise in a similar linear manner to achieve an organic connection between the chords. A mix of a linear and vertical approach works best, as does of course staying close to the melody. The harmonic progressions break the common written and unwritten rules, and especially the root motion changes its role from providing simple movements in 4'ths and 5'ths to being vagrant and taking very unexpected paths. Due to Shorter's uncanny sense for tension and release, and an obvious knowledge of the basics of harmony, we still feel the organic flow of logical harmonic progressions. One important contributor to this is the fact that Shorter never over-writes, i.e. he has very good sense of when to stop introducing more new music material. Especially since the unfamiliar and often very charged harmonic motions give away so much more information than what regular diatonic progressions would do, it is very important as a composer to be able to "hear" when the "painting" has had the final stroke. In Shorter's writing from this time, and especially through the Miles Davis Quintet period, one can also have a sense that in the composing process the melody and harmony take turns unfolding the composition. As a listener one is equally drawn to listen to the melody at times and to the chords at other times. In Shorter's writing for Miles Davis Quintet there is also an openness inherent in the compositions which allows the rest of the band to fully explore the song with improvisational statements. Herbie Hancock's unmistakable genius at reharmonization and both rhythmic and harmonic embellishment was here at its peak. Tony Williams' propulsive and rhythmic inventiveness was allowed to flourish in the space that was built into the compositions. Shorter's harmony also freed up the bass role and Ron Carter was a master at changing the root of a chord, sometimes staying on a pedal point throughout an extended section and thus making a section having a modal sound. All this took place at the same time as he was providing the band with cohesiveness, swing and rhythmic interest. Miles Davis steered the "ship" and gave it soul, connected it with the past. Above all, he had an explicit sense for when to bring everybody, and the music, back and therefore not allow the "painting" to get blurry. On later recordings, when the same members, without Davis, play the same material with the same concept of interplay, the music takes on a nearly grotesque quality of overplaying. This is of course in comparison with the original setting. What made this whole process possible was the chemistry between the musicians, the deeply rooted sense of collective improvisation stemming back to the African roots of musical and social sensibilities. Although they allowed themselves a lot of individualistic freedom the whole did not suffer because their common firm roots in the jazz tradition held them together.

Major Changes

The two years before Zawinul, Vitous and Shorter started Weather Report, Shorter had been experimenting in the true sense of the word, both with Miles Davis and on his own projects. The years of 1967-70 were a revolutionary time politically, and it showed in the music of the time also. Davis had started mixing in elements from outside the jazz tradition. Elements from rock, funk and rhythm & blues were present. American styles were not the only ones. Indian and African influences were also present. In a sense it was a kind of "world music" 20 years before the term was invented. It made the biggest change within the rhythm sections, where the acoustic bass was replaced by the electric and the typical jazz drummer was replaced by a funk rock drummer. The other big change was the emergence of electronic instruments, electric pianos and synthesizers. When Shorter together with Zawinul and Vitous started Weather Report it was actually a step back "inside" compared with what Shorter had been doing on his previous albums such as Super Nova, Moto Grosso Feio and Odyssey of Iska. All the new ingredients discussed above were present, and added to that were new recording techniques like over-dubbing and "cutting and pasting". Miroslav Vitous once described how he on one of his compositions played chords on the piano but had the engineer not start recording until after the attack thus creating a spacious and not easily identified sound. What was more "inside" now than before was the sense of composed form structures instead of improvised form. The first album Weather Report (recorded in 1971) is the most loosely conceived. Shorter's compositions did not change drastically from his writing for Miles Davis Quintet in the mid 60's. For example, Shorter's Tears from Weather Report (1971), could also have been played by a regular jazz quintet, but is played on this recording with a back beat and a heap of percussion that add additional colors. Since up through 1968 the rhythms were all based on jazz tradition with influences from Latin, Afro-Cuban and Brazilian rhythms, the biggest change was maybe not in the harmony, melody or form but rather the way the melodic rhythms and overall feel were tailored.

With the change of rhythm section on their album Mysterious Traveler (in 1974) the band took on a funkier and more groove- oriented character. The rhythm section with roots in black American music styles pulled the band closer to the popular rhythms of the time and thus won big audiences world-wide. Now Shorter's compositions started to change more drastically. Particularly the 16th note rhythms and the back beat from funk and rock were what stood out as being what changed in the compositions. The harmony took on a more modal character with sometimes catch 3-4 chord repetitive vamps. The melodies went from being long floating phrases to short and sometimes catchy statements. Shorter's compositions still kept artistic integrity at the same time as they communicated with a large audience.

The main change in Shorter's compositions after Weather Report, on the albums he released as a leader, is the strong presence of counterpoint. On Atlantis, one can hear the very intricate counterpoint between the bass and melody. This is really the first examples of completely written out bass parts although his awareness of the important relation between bass and melody has been present throughout his career. His composition Joy Ryder, from Joy Ryder, is solely built on two counter lines that interact in a sort of improvised free counterpoint with occasional hints at tonal centers. Not until after the main body of the tune, at the solo section is there a clear sense of tonality and actual chord changes. What has not changed in Shorter's music is his keen sense of melody, explicable taste for harmony, his rhythmic understanding and his own unmistaken voice. As a Coda I will let Shorter speak with his own words, " Life to me is like an art, because life has been created by an artist, the Chief Architect."15

Copyright © Bruno Råberg 1995

1 Chambers Jack, Milestones, (Quill), p. 303.

2 Third Earth Productions, Wayne Shorter, (Hal Leonard Pub. Corp.), p. 4.

3 Troupe, Quincy , Davis, Miles , Miles the Autobiography, (Touchstone, Simon and Schuster), p 247.

4 Ibid., p.270.

5 Ibid., p.273.

6 Ibid., p. 273.

7 Third Earth Productions, Wayne Shorter, (Hal Leonard Pub. Corp.), p.5.

8 Third Earth Productions, Wayne Shorter, (Hal Leonard Pub. Corp.), p. 47.

9 Ibid., p.47.

10 Heckman,Don, quote from liner notes to Speak No Evil.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Third Earth Productions, Wayne Shorter, (Hal Leonard Pub. Corp.), p. 32.

14 Ibid., p.106.

15 Shorter, Wayne, Creativity and Change, (Down Beat 12/12/68)

http://artsmeme.com/2012/10/23/wayne-shorter-blows-horn-for-l-a-jazz-society/

At a swank do at the Universal Hilton Hotel Sunday evening, the Los Angeles Jazz Society, for the past 29 years the labor of love of Flip Manne (she’s the surviving widow of drummer Shelly Manne), honored saxophonist Wayne Shorter as its 2012 Jazz Tribute Honoree.

Movie maven Leonard Maltin, also a jazz lover, smoothly emceed the event.

A grand master of the art form both as composer and player, Shorter, whose jazz pedigree peaked with his mid-1960s membership in Miles Davis’s quintet (or was it his launching of the fusion group Weather Report?), thrilled the audience, all supporters of the Society’s jazz educational programs.

Among the evening’s other honorees was guitarist John Pisano, garnering a Lifetime Achievement Award, and Denise Donatelli, recipient for Jazz Vocalist. A cool cat named Gordon Goodwin accepted the award for arranger/composer, then led his Big Phat Band in his Grammy-winning blast-out of Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.” So colorful and so well played by Goodwin’s rambunctious 16-piece orchestra.

Presenting Shorter with the award (recent recipients include Arturo Sandoval, Poncho Sanchez, George Duke, and James Moody), singer Patti Austin quipped, “I spoke to Wayne a little while ago and asked him, ‘Why me?’ He told me he thought a woman should present his award. But then he asked me to send him “binders of women”!

“Wayne’s from New Jersey; from the school of innovators. He’s going to turn 80 next year. He’s a Leo-Virgo cusp. He’s my favorite Buddhist,” she said.

Shorter also made comments: “One word keeps coming to me. The word is singularity. When I talk to young people, I ask them what music is for — beyond money and fun. What is anything for? It has to be worth trusting being in the moment. That’s what jazz is. Being in the moment is creating singularity in your life.

“Tragedy is temporary. A single moment is an eternity. Singularity is about handling the unexpected.

“How do you rehearse the unknown? Not to be arrogant or scared … you have to start with courage or fearlessness. You have to turn a train wreck into an opportunity,” he offered, with slight solemnity.

Then breaking into a devilish grin he added, “and … have fun wid’ dat!”

With those words, Shorter repaired across the stage and joined a clutch of jazz kids from UCLA’s Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz Performance. Leading them, he laid down heavy sounds. Launching with his soprano saxophone into a super slow anthem, he built a wall of noise that erupted into the occasional screech, or blaring. It was all deliberate, all muscular; yes, he blew a mighty horn.

A huge thrill to hear Wayne Shorter in such great form.

International Jazz Day 2014: Wayne Shorter: Philosophy of Life Through Jazz:

INTERVIEW WITH THE GREAT WAYNE SHORTER FROM 2002

TODAY IS THE 80TH BIRTHDAY OF ONE OF THE GREATEST MUSICIANS AND COMPOSERS ON THIS PLANET: WAYNE SHORTER, (b. August 25, 1933)

THE FOLLOWING INTERVIEW FROM 2002 WAS CONDUCTED BY BOSTON-BASED JAZZ CRITIC AND HISTORIAN BOB BLUMENTHAL

by Bob Blumenthal

Of the many interviews that I have conducted in Burlington, Vermont at the city's Discover Jazz festival, none has proven more memorable than my conversation with Wayne Shorter in 2002. As is the case with a handful of artists (Ornette Coleman and the late Andrew Hill come to mind), Shorter is a thinker of substance who speaks in images all his own, images that can sometimes be tricky to follow. In addition, I had seen interviews by others where a focus on historic and technical specifics evoked terse responses from Shorter, at best.

As you will see, Shorter was relaxed, loquacious and humorous, often slipping into voices or following his own stream-of-consciousness leads, but always addressing the issue at hand. The only moment of discomfort occurred in the section of audience questions, when someone asked what needed to be done to save jazz; but even then, after scowling, Shorter made his point. Ive tried to retain as much of the flow and the flavor of the conversation as possible, and want to thank Shorter for his permission to publish our exchange.

A lot of musicians are identified with their home towns, and you often hear talk of all the greats from Philadelphia, Detroit. You come from a place that I suspect was also a hotbed of music, Newark, New Jersey. What was the music scene like growing up in Newark?

WS: I didn't pay any attention to what was going on, because I was not into music until about the age of 15. I had been drawing, majoring in Fine Arts. Knowing about music only meant, to me, what I heard in film scores, but we didnt use those words. We called it a soundtrack, or background. I had heard about the background stuff that the organ player played in the Twenties, behind silent films. My mother would tell me about how people sat in the theaters, listening, and would say, Uh oh, the organ player's drunk! They could really tell when they were doing that Follow the bouncing ball stuff. So my parents generation was really glad when sound came in (in films). But thats the earliest recollection of something staying inside of me. Id go to the Capitol Theatre and see Captive Wild Woman with John Carradine and the guy who played Doc on Gunsmoke

Milburn Stone?

WS: Yes, that guy. He was the lion tamer, and the actresss name was Aquanita. She only had one name, like Burgess Merediths wife, Margo. Those are the things I was noticing people with one name, and the music behind Bela Lugosi when he played Igor in Frankenstein [WS pronounces it Frankensteen], the Son of Frankenstein. Then The Wolf Man. Now The Wolf Man was the start of something, the first time we went to the movies at night. When you were eight years old, going with your parents at night was a big thing. And they had two films, The Wolf Man and a movie with Olivia De Haviland called To Each His Own. It was a soap opera, but she was good in it. But as kids, we were waiting for The Wolf Man.

I always identified your piece Children of the Night with Bela Lugosi and Dracula.

Yes, but then Children of the Night became astronauts, going out into the darkness of the unknown. But that film music, the backgrounds when Lon Chaney was changing into a werewolf, or The Mummy. It seemed like those composers had carte blanche. No one was leaning over their shoulder saying, We want a hit. Lets get my cousin to write a hit song. That kind of writing in those films got me interested about sound, and I just got curious and more curious.

Then I heard a lot of stuff on the radio, and I got really interested when I heard Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Max Roach and all those guys. I remember one evening, just when I was turning sixteen, some of the guys saying You ever heard of Charles Christopher Parker? These three or four guys, they were hip. We were the only ones in the school who were paying attention to Charlie Parker. We went to this theater around the corner from school, the Adams Theatre, they would have a movie and a show there, and they had all the bands there: Stan Kenton, Woody Herman. I saw Jimmie Luncefords band there, and of course Dizzy Gillespie, Illinois Jacquet, his brother Russell Jacquet, Andy Kirk. And comedians like Timmie Rogers. He used to say Oh yeah! all the time, and wed say Oh no! So all of that, sight and sound, was getting to me.

I played hooky a lot my third year of high school, going to that theatre. They caught me because I wrote a bunch of notes falsifying my mothers signature. This was the first high school to have an intercom and an elevator; when they called you down on the intercom, the whole school heard it. Miisster Shhhorter [imitates a bad intercom], report to the Viice Prrincipalls offfice immediately." To me, the whole school stopped, because I was supposed to be one of the nice guys. He played hooky? See, I would skip one class to hear the band at the Adams, go back for another class, and then skip again later in the day when the band would come back on. I had 56 absences in a short period of time. So they called my parents in and the Vice Principal asked, Where do you go when you play hooky?

The Adams Theatre.

Oh, do you like movies?

Yes, but also the bands there.

Oh, do you like music?

So they called in the music teacher, Achilles DAmico and told me, Were going to put you in a music class, so you can study music from the ground up. But this is primarily disciplinary, because Mr. DAmico is a disciplinarian. And the first day I was in his class and this is the hook; this is the hit he stood up after we had listened to Mozarts G minor 40[th Symphony] and said, Musics going to go in three directions. Then he held up The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky, another record that I had been hearing by Yma Sumac, Xtabay, and a third record, which was Charlie Parker. That was the stuff on the radio.

So I remember what Charlie Parker was doing, and I remember the bunny hop at the prom. The band would play the bunny hop, but I wasnt in the band. They have to play the bunny hop, and wear band uniforms? Get out of here, man.Then at 15 or 16, I started taking clarinet lessons, but I was checking out the college guys. They had the brown and white bucks, the seersucker jackets and suits. Some had cars, and some of the other guys, with the leather jackets, had motorcycles. This was around the time that The Wild One came out, with Brando. Our schoolyard had a whole section for motorcycles, and another for cars. They guys who didnt have cars or motorcycles walked home. I was walking home, carrying my saxophone and a bag of books, thinking The guys getting rich are the guys making hits; but this stuff bebop, progressive music, because I was interested in all modern music.

I used to listen to a program every Saturday afternoon, New Ideas in Music, about the evolution of classical music into contemporary and onward. Anyway, I knew that this was going to be a long, long struggle, a long road. Because everybody I knew, at the parties and the dances, if you brought a modern record and put it onThey wanted the slow drag stuff, so the guys could dance with the girls, hook up and make time. But put something interesting on and shhhhhhhh [imitates a needle dragged over vinyl], Take that off! My brother and myself and another guy, Pete Lonesome, made it a point to keep going straight ahead. At the universities, they [Alan Shorter and Pete] would crash the fraternity parties to get new ideas from the records they were playing there.

Thats the only way that I can talk about music. Playing music, to me, reflects whats happening and whats not happening. And what some people wish could happen. Sometimes you get in a fantasy place all by yourself, you can be self-contained. Get a little cash flow, just do music for yourself while not being selfish. Dont record, just make music at home and little videos, like that. An interviewer asked me what I would do if I didnt do music, and I said it didnt make any difference because everything is connected. But the way things are going now - what is considered top-drawer, what a lot of young people consider great in music, books and films, towering this and that.

Two thumbs up?

Yeah. I dont see a lot of people in the science fiction section of bookstores. The imagination thing. You dont have to be a bad person to use your imagination, but if you have an imagination you can be 10,000 steps ahead of a lot of bad people. And this country is the greatest country for having this open-door policy, open-end for thinking and ideas. Everything stopped with classical, modern contemporary, with Gershwin and Copland and Leonard Bernstein. Weve got to keep going, but now guys are writing for movies: John Willians, Goldsmith, James Horner. But we need more than that from Hollywood, with its closed-door policy. If its racism, to hell with racism. Weve got to keep moving. As far as the imagination, there are a lot of people slipping through the cracks who could be inspiration for the salvation of the whole planet. A lot of us will say, Oh, I wont do it, I cant do it. But go back into your little dream box that you were in as a kid, and hey.

I'm ready to kick ass. I'm going to be 70 in August 2004, and it feels like [in conspiratorial voice] theres a red door down there, waiting for me. But before I go through that door, Im going to go to the end of the line and stick with what Im doing. But Im bringing things in. My next record has music from the 13th Century, a Villa Lobos thing, something from Wales, something I wrote about Angola, something from Spain that Miles had given me the sheet music for in 1965 and said [imitating Davis] Do something with this. Also, music I did as an assignment in my modern harmony class in 1952. Maybe eight measures that I had put away and brought back out in 1997 and developed a little bit. Herbie and I recorded it. Its about the lady in I still call it Burma Aung San Suu Kyi. So when I talk about recording as I go to the end of the line, for me its to celebrate everybody, all humanity, and the eternity that we all possess.

If you can remember the first thing of consciousness when you were a baby, if you can remember and can put a word to it. Some people cant, but when I go back I can see the high chair. After that high chair theres nothing, but there is a word, and the word that comes back to me now is always. want to celebrate eternity. Celebrating eternity means to me to manifest all of the time as a human being. Eternity presents surprises. Im celebrating lifes adventure. I like that guy on Oprah Winfrey who said that life is the story of everyone's soul. Its a one-time story, meaning one-time to me; but there are billions of stories, and they are linked. To be original, to me, is to want to celebrate something so hard that you want to give it a present. The more original you get, the deeper your confirmation of eternity itself. To celebrate oneself selflessly, not selfishly; to say that life is the damn religion. The entire alphabet cant exist without A, a million dollars cant exist without one penny.

This is what I think about when Im talking to myself, when Im checking out movies, books. Theres a good book called Drinking Midnight Wine by Simon Green, another one I have. The guy, Glenn Kleier, wrote one book, what is its nameabout a woman wandering around in the desert who is the sister of Jesus. Shes called Jeza, and she goes to Rome and says, I come not to kiss the ring of St. Paul, but to reclaim it. Its called The Last Day, and its a damned good book. Some lawyers read it and said, Damn, if they make a movie out of this one, everybodys going to go to court.

I have fun, I dont get serious. [In haughty voice] Oh, you take a minor third, and I use a Rico #4, Im looking for a Mark VI. I cant get into that. I get into what is anything for? I dont talk about music like Me and my horn, me and my little saxophone. Im not the cellist who grows up hiding behind the cello, or some actors who hide behind their characters. Thats okay, you can hide behind them, because its never too late to come out. I think life is supposed to be a lot of fun. The reason for life is happening, its happening right now. I dont like words like beginning and end. We lean on them for our sanity, but they are artificial, and they create a lot of other artificial stuff in our head, boundaries that we can tear down. People who stutter and want to break that habit, or bite their nails or twitch. Im not making fun of that but they dont really stutter, its something they are determined to break through. I think playing music and hearing more variety of stories and celebration in music, instead of only seeing red, blue and yellow, or having just CBS and NBC, or people trying to control the internetIf we all had our own newspaper, how about that? It would be like Network, Im not going to take it anymore! The internet is one breakthrough, but there is going to be another breakthrough, I think, in home entertainment. Soon well have Laundromats in our homes, nursing homes with a robotic paramedic.

In the notes to Night Dreamer, you say that up to a point you created music out of your own experience, but now wanted to start connecting your experience to the world. I read that recently and was reminded of when Joe Zawinul told me that you were the first person he met with what he called the new thinking. Were there particular experiences that brought you to these turning points and revelations?

The first book I read when I was 13 was Charles Kingsleys The Water Babies. I just called London and talked to an old lady who has a shop near the Thames. I wanted an 18-something edition, and I got a book by Charles Kingsleys son. She said [in halting, old voice], I-have-a-1935-edition, but-I-think-I-have-an-older-one. I-just-have-to-look-in-the-cupboard. And I was thinking, Man, thats where I want to be with her, going into the cupboard. I have about five or six copies. The first one I read had nice pictures; it was for children. Its about what happens when the hero goes to the ocean to see whats happening. Theres some stuff in there, wow.

Then, at 15, I read Occams Razor. What a nice title, though now it would be considered too Middle-Eastern. That book is about slicing time and walking through it. Then I crawled through Dune. Then I came to a screeching halt with The Fountainhead. Ayn Rand came to my school, NYUI took a class in philosophy there, and the professor used to walk around, reach over you and put the final grade on your paper before you were finished. On the day of the final exam, he reached over my shoulder, put a mark on my paper Im not going to tell you what he gave me said Why dont you major in philosophy? and kept on going.

I really dig science fiction, or science reality. I did a record with a Japanese friend, and a friend of his used to escort Stephen Hawking around Tokyo. So when my friend did a record about galaxies, he got Stephen Hawking to open it, [imitating Hawking] There are at least two hundred million stars in our galaxy, and he goes on. Anyway, Hawking enjoyed the project so much that he sent my friend some lectures on quantum physics, and he opens one with a limerick:

There once was a lady from Wight Who could travel much faster than light She took off one day In a relative way And arrived on the previous night.

I read that and said, Stephen Hawking, my man! As to the lectures, I read them a line at a time, think about them, go back to a science fiction book or a movie. But thats whats going on. I seem to attract that kind of thing now. I was seeking it when I was 16. I used to stay in the library when it closed, back on the floor reading about Beethoven or something else.

With so many vivid interests, why did you choose to pursue music?

Music has a sense of velocity in it. Theres also a sense of mystery. But everything is really mysterious. I used to look at my hand and say, What is this? Everything in life is not down pat. With music, its another kind of meal, another dimension, not just a language but another miracle. Its a gift not to do music, but just that music is there. And what else is there, that were not harvesting? So move over Bill Gates and Albert Einstein.

[Question from the audience] What influence did your brother Alan have on you?

We were influencing each other from the beginning, hipping each other to something, checking things out while walking down the street. My brother just talked out and said what he thought. He saw constraints in life that he didnt want to deal with, like the dating thing. He just skipped through all of that, and said, Nobodys ready for me. He played an alto sax for a while, and he painted Doc Strange on the side of his case. People used to call us Strange and Weird, so I put on my clarinet case Mr. Weird. Then we had this band together, nine guys. Another band at the time in New Jersey had bandstands, uniforms, lights, girlfriends who would carry their instruments, everything. Wed go to the gig, and my brother would bring his horn in a shopping bag, and play it with gloves on. Hed wear galoshes when the sun was shining; and wed take the chairs and turn them around and start playing Emanon or Godchild or :Jeru by ear, with newspapers on our music stands, making fun of people who read music. We made sure our clothes were wrinkled, because if you played bebop you were raggedy, not smooth. You didnt go out on dates, you made it with your instrument.

[Question from the audience] What can we do to save jazz?

I think that taking chances is the beginning. Being unafraid of losing this and that, jobs, friends. You dont have to have the extreme you see in biographies of Van Gogh, always being by himself or arguing with others, but youve got a lot of leeway. Knowing the difference between what youre told and what you find out for yourself; starting as an individual, being alone. We dont have to preserve jazz; we have to start preserving the stuff that comes before all of that.

[Question from the audience] Can you talk about playing with Miles Davis?

I had the most fun playing with Miles Davis, and John Coltrane told me that, too. Now, the same kind of fun is happening with John Patitucci and Brian Blade and Danilo Perez, and over the years I had fun playing with Joe Zawinul and Herbie Hancock. But Miles was a source kind of guy. You know how Captain Marvel would go to Delphi, to get his shazam stuff together? Miles was like that, and he was a buddy, too.