AS OF JANUARY 13, 2023 FIVE HUNDRED MUSICAL ARTISTS HAVE BEEN FEATURED IN THE SOUND PROJECTIONS MAGAZINE THAT BEGAN ITS ONLINE PUBLICATION ON NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2017/06/julian-cannonball-adderley-1928-1975.html

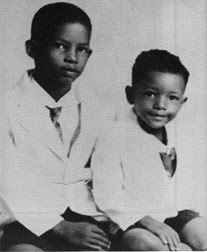

PHOTO: CANNONBALL ADDERLEY (1928-1975)

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/cannonball-adderley-mn0000548338/biography

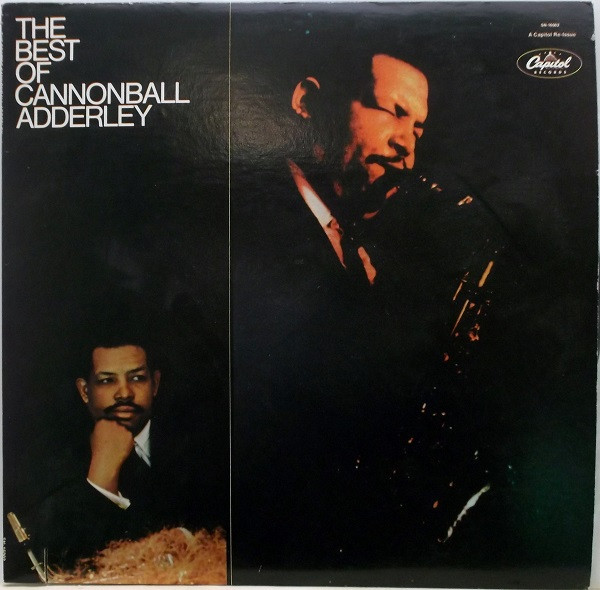

Julian "Cannonball" Adderley

(1928-1975)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

During its Riverside years (1959-1963), the Adderley Quintet primarily played soulful renditions of hard bop and Cannonball really excelled in the straight-ahead settings. During 1962-1963, Yusef Lateef made the group a sextet and pianist Joe Zawinul was an important new member. The collapse of Riverside resulted in Adderley signing with Capitol and his recordings became gradually more commercial. Charles Lloyd was in Lateef's place for a year (with less success) and then with his departure the group went back to being a quintet. Zawinul's 1966 composition "Mercy, Mercy, Mercy" was a huge hit for the group, Adderley

started doubling on soprano, and the quintet's later recordings

emphasized long melody statements, funky rhythms, and electronics.

However, during his last year, Cannonball Adderley was revisiting the past a bit and on Phenix he recorded new versions of many of his earlier numbers. But before he could evolve his music any further, Cannonball Adderley died suddenly from a stroke.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/cannonball-adderley/#bio-top

Cannonball Adderley

Both as the leader of his own bands as well as an alto and soprano saxophone stylist, Julian Edwin "Cannonball" Adderley was one of the progenitors of the swinging, rhythmically robust style of music that became known as hard-bop.

Born September 15, 1928, into a musical family in Florida, Adderley was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1950. He became leader of the 36th Army Dance Band, led his own band while studying music at the U.S. Naval Academy and then led an army band while stationed at Fort Knox, Kentucky. Originally nicknamed "Cannibal" in high school for his voracious appetite, the nickname mutated into "Cannonball" and stuck.

In 1955, Adderley traveled to New York City with his younger brother and lifelong musical partner, Nat Jr. (cornet). The elder Adderley sat in on a club date with bassist Oscar Pettiford and created such a furvor that he was signed almost immediately to a recording contract and was often (if not entirely accurately) called "the new Bird."

Adderley's direct style on alto was indebted to the biting clarity of Charlie Parker, but it also significantly drew from the warm, rounded tones of Benny Carter; hard swingers such as Louis Jordan and Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson were important influences as well. Adderly became a seminal influence on the hard-driving style known as hard-bop, and could swing ferociously at faster tempos, yet he was also an effective and soulful ballad stylist.

From 1956-57, Adderley led his own band featuring Nat, pianist Junior Mance and bassist Sam Jones. The group broke up when he was invited to join the Miles Davis Quintet in 1957. Davis expanded his group to a Sextet soon thereafter by hiring saxophonist John Coltrane. "I felt that Cannonball's blues-rooted alto sax up against Trane's harmonic, chordal way of playing, his more free-form approach, would create a new kind of feeling," Davis explained in his autobiography.

From 1957-59, Adderley recorded some of his best work on the landmark Davis albums Milestones and Kind of Blue within this sextet. Davis reciprocated with a guest appearance on Adderly's 1958 solo album Somethin' Else, which also included bassist Jones, pianist Hank Jones, and drummer Art Blakey.

Adderley left the Davis band to reform his quintet in 1959, this time with his brother, Sam Jones, pianist Bobby Timmons and drummer Louis Hayes. Yusef Lateef made it a sextet around 1962; pianist Joe Zawinul replaced Timmons around 1963. Other band alumni include Charles Lloyd, and pianists Barry Harris, Victor Feldman and George Duke.

Adderley recorded for Riverside from 1959-63, for Capitol thereafter until 1973, and then for Fantasy. He suffered a stroke while on tour and died on August 8, 1975. He can also be found on recordings led by Bill Evans, John Coltrane, Wes Montgomery, Art Blakey and Oscar Peterson, and collaborated with singers Sarah Vaughan, Dinah Washington, Joe Williams, Lou Rawls, Sergio Mendes and Nancy Wilson.

http://panopticonreview.blogspot.com/2013/10/julian-cannonball-adderley-1928-1975.html

Monday, September 16, 2013

Julian "Cannonball" Adderley (1928-1975): Legendary Alto Saxophonist, Composer, and Bandleader--A Celebration of His Music, Life, and Legacy On the 85th Anniversary of His Birth

(b. September 15, 1928--d. August 8, 1975)

Cannonball Adderley

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaJulian Edwin "Cannonball" Adderley (September 15, 1928 – August 8, 1975) was an American jazz alto saxophonist of the hard bop era of the 1950s and 1960s.[1][2][3][4]

Adderley is perhaps best remembered for the 1966 soul jazz single "Mercy, Mercy, Mercy",[5] which was written for him by his keyboardist Joe Zawinul and became a major crossover hit on the pop and R&B charts. A cover version by the Buckinghams, who added lyrics, also reached No. 5 on the charts. Adderley worked with Miles Davis, first as a member of the Davis sextet, appearing on the seminal records Milestones (1958) and Kind of Blue (1959), and then on his own 1958 album Somethin' Else. He was the elder brother of jazz trumpeter Nat Adderley, who was a longtime member of his band.[6]

Early life and career

Julian Edwin Adderley was born on September 15, 1928, in Tampa, Florida to high school guidance counselor and cornet player Julian Carlyle Adderley and elementary school teacher Jessie Johnson.[7][8] Elementary school classmates called him "cannonball" (i.e., "cannibal") after his voracious appetite.[7]

Cannonball moved to Tallahassee when his parents obtained teaching positions at Florida A&M University.[9] Both Cannonball and brother Nat played with Ray Charles when Charles lived in Tallahassee during the early 1940s.[10] Adderley moved to Broward County, Florida, in 1948 after finishing his music studies at Florida A&M and became the band director at Dillard High School in Fort Lauderdale, a position which he held until 1950.[11]

Adderley was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1950 during the Korean War, serving as leader of the 36th Army Dance Band.[12] Cannonball left Southeast Florida and moved to New York City in 1955.[6][11] One of his known addresses in New York was in the neighborhood of Corona, Queens.[6][13] He left Florida originally to seek graduate studies at New York conservatories, but one night in 1955 he brought his saxophone with him to the Café Bohemia. Cannonball was asked to sit in with Oscar Pettiford in place of his band's regular saxophonist, Jerome Richardson, who was late for the gig. The "buzz" on the New York jazz scene after Adderley's performance announced him as the heir to the mantle of Charlie Parker.[11]

Adderley formed his own group with his brother Nat after signing onto the Savoy jazz label in 1955. He was noticed by Miles Davis, and it was because of his blues-rooted alto saxophone that Davis asked him to play with his group.[6] He joined the Davis band in October 1957, three months prior to the return of John Coltrane to the group. Davis notably appears on Adderley's solo album Somethin' Else (also featuring Art Blakey and Hank Jones), which was recorded shortly after the two met. Adderley then played on the seminal Davis records Milestones and Kind of Blue. This period also overlapped with pianist Bill Evans' time with the sextet, an association that led to Evans appearing on Portrait of Cannonball and Know What I Mean?.[6]

His interest as an educator carried over to his recordings. In 1961, Cannonball narrated The Child's Introduction to Jazz, released on Riverside Records.[6] In 1962, Cannonball married actress Olga James.[2]

Band leader

The Cannonball Adderley Quintet featured Cannonball on alto sax and his brother Nat Adderley on cornet. Cannonball's first quintet was not very successful;[14] however, after leaving Davis' group, he formed another group again with his brother. The new quintet, which later became the Cannonball Adderley Sextet, and Cannonball's other combos and groups, included such noted musicians as saxophonists Charles Lloyd and Yusef Lateef, pianists Bobby Timmons, Barry Harris, Victor Feldman, Joe Zawinul, Hal Galper, Michael Wolff, and George Duke, bassists Ray Brown, Sam Jones, Walter Booker, and Victor Gaskin, and drummers Louis Hayes and Roy McCurdy.[citation needed]

Later life

By the end of the 1960s, Adderley's playing began to reflect the influence of electric jazz. In this period, he released albums such as Accent on Africa (1968) and The Price You Got to Pay to Be Free (1970). In that same year, his quintet appeared at the Monterey Jazz Festival in California, and a brief scene of that performance was featured in the 1971 psychological thriller Play Misty for Me, starring Clint Eastwood. In 1975 he also appeared in an acting role alongside José Feliciano and David Carradine in the episode "Battle Hymn" in the third season of the TV series Kung Fu.[15]

Songs made famous by Adderley and his bands include "This Here" (written by Bobby Timmons), "The Jive Samba", "Work Song" (written by Nat Adderley), "Mercy, Mercy, Mercy" (written by Joe Zawinul) and "Walk Tall" (written by Zawinul, Marrow, and Rein). A cover version of Pops Staples' "Why (Am I Treated So Bad)?" also entered the charts. His instrumental "Sack o' Woe" was covered by Manfred Mann on their debut album, The Five Faces of Manfred Mann.[16]

Death and legacy

In July 1975, Adderley suffered a stroke from a cerebral hemorrhage and died four weeks later, on August 8, 1975, at St. Mary Methodist Hospital in Gary, Indiana.[2] He was 46 years old.[2] He was survived by his wife Olga James Adderley, parents Julian Carlyle and Jessie Lee Adderley, and brother Nat Adderley.[17] He was buried in the Southside Cemetery, Tallahassee.[18]

Later in 1975, he was inducted into the DownBeat Jazz Hall of Fame.[6][19] Joe Zawinul's composition "Cannon Ball" on Weather Report's Black Market album is a tribute to his former leader.[6] Pepper Adams and George Mraz dedicated the composition "Julian" on the 1975 Pepper Adams album of the same name days after Cannonball's death.[20]

Adderley was initiated as an honorary member of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia fraternity (Gamma Theta chapter, University of North Texas, '60, and Xi Omega chapter, Frostburg State University, '70) and Alpha Phi Alpha[21] (Beta Nu chapter, Florida A&M University).

Discography

Cannonball Adderley - archive interview

Location: Opposite Lock Club, Birmingham

Year: 1971

(Article copyright by John Watson)

Broadway

Electrifying

Commercial

Two driving new tunes - The Chocolate Nuisance, written by Roy McCurdy, and The Steam Drill, written by George Duke - had proved particularly popular with the audience at the Opposite Lock.'Those tunes are on an album we did, The Black Messiah, recorded live at the Troubadour Club. But we make all our records live, frankly. Even in the studio, we work live. Even if we say "We're not going to record in a night club, we're going to record in a studio", we still have a live audience, because we would rather play to a live audience rather than just play to microphones.'

Technical

Colleges

Frightened

Community

|

Published in Coda Magazine, issue number 186 (1982)

My brother Nat and I had heard all these stories about the New York Musicians' Union; how they would fine you for sitting in, so when the clubowner came over to them and said "Who's that guy playing saxophone?" rather than give him my name, Nat said, "Well, that's Cannonball," So I became known as Cannonball once again, after so many years of being just plain Mr. Adderley, schoolteacher

Years ago when I started to play the saxophone I wanted to play tenor. This was during World War Two, and there were no saxophones available, period. So I bought this beat-up alto from a guy when I was still in high school, because it was the only saxophone available. So I tried to play like a tenor player on the alto; I used to play Lester Young solos, Coleman Hawkins solos, and lesser-known tenor players who were important to me: Budd Johnson, who was with Earl Hines; Julian Dash and Paul Bascomb, who were with Erskine Hawkins, Buddy Tate, I'd play their solos, if I could, I developed a sort of hard, explosive style on the alto because there was nobody doing it. And when I heard Charlie Parker I was immediately disappointed in myself, because here was a guy who was playing explosively, and excellently, with complete control, and I was still a student player. So immediately I went out and bought all the things I could by Jay McShann, because it really clicked me into another- thing. I started on alto in about 1942,I was about 14.

When you made your first records, I imagine most of the musicians around New York wanted to hear this new guy, and probably you were in a certain amount of demand for recording sessions...

Not really, there was not too much going on in the way of recording in New York then. All the action was on the West Coast, Everybody was starving to death, as a matter of fact. That's why I got the chance to play with everybody early. There were a few organized bands that were making it: The Modern Jazz Ouartet, Max Roach and Clifford Brown,... Horace Silver and Art Blakey had formed The Jazz Messengers, but they weren't working either. They had a date every Sunday at a place called The Open Door. That's why Horace was working with Oscar Pettiford, he didn't have a job, he was just a sideman then. Dizzy Gillespie had a band that played in a lot of places that were, well, strange for a jazz group. And he had some strange, well, different musicians let's put it that way. He had some guys out of Buffalo, New York playing with him, and Sahib Shihab, and Joe Carroll singing with him. So he had an organized group, but Miles Davis for instance was just kind of messing around, it was the doldrums for him, and in fact for nearly everyone in New York, 1955. I'd go to Birdland and the bill would read John Greas, the French-horn player, or Bud Shank, Shorty Rogers, Claude Williamson, the West Coast Jazz syndrome. That kind of band would be there, or maybe Kenton - who had a great band then as a matter of fact, with Mel Lewis and Lee Konitz, Conte Candoli and guys like that.

Nat and I first recorded together on Savoy, with Kenny Clarke. Kenny set up a date with Herman Lubinsky, and Ozzie Cadena, who was Herman's representative, on Savoy. "Bohemia After Dark" (Savoy 4514): my first recording, Nat's first, Paul Chambers' first, Donald Byrd's first, Jerome Richardson was on it, Horace Silver....we did Hear Me Talkin' To Ya, Bohemia After Dark, lots of beautiful things. That led to my first date as leader, "Presenting Cannonball" on Savoy (45151 with Hank Jones, Kenny, Paul Chambers, Nat and me. Then Nat did his first date as leader, "That's Nat," on Savoy (MG 1.2021). Then we signed a contract with Mercury, and started to take care of business there.

Nat and I played together for many years ,and we developed lots of things, based on other peoples' materials, and some ideas of our own, We were basically just simple players. We had never been exposed to the blood and guts, dog-eat-dog syndrome, we were just Florida guys. So we played a lot of blues, a lot of funk, a lot of gospel-sounding stuff, and cute things based on Bird and Dizzy, Bird and Miles, based on that feeling.

But with Horace, and the New York guys on there, there was another feeling going on. Paul Chambers was an instant genius. He fit right into things, he was probably the most important bass player of that era. I don't mean that he was more important than Ray Brown, in terms of his playing and so forth, but Ray Brown was playing with Oscar Peterson, he was not a date player, when he played dates it was for that Jazz At The Philharmonic group thing - and Paul was there in New York and just doing it.

In fact, speaking of Paul, I played on a date with him for VeeJay (LP1O14), in Chicago, and we needed a brass player. So I sent to New York for this kid I'd heard playing in Brooklyn - and it was the first recording fo Freddie Hubbard.

Actually, there was a series of funny events Coltrane left the band because he had some personal problems with his health and so on and he decided he was going to reform, so he went to Philadelphia and stayed about four or five months. He used to drink and so other things that were unsavory, and by the time he came back to New York he had completely changed his image, he no longer did anything, he was an instant Christian.

When Trane left, Miles hired me essentially because he didn't dig any of the tenor players around. Plus he was always having problems with Red and Joe and so on - not because they were bad guys, they were all beautiful cats, but everybody had his own style and attitude about what he was due, and so forth.

It was verv interesting, because Red used teach Miles boxing; Red was an ex-boxer....

Anyhow I broke up my band, because we weren't doing anything anyhow, we were mostly unemployed, and Nat had been offered a job by Gerry Mulligan; and Miles had been' pestering me to come with him, because Miles wasn't doing anything. So I went with him and we went out on tour, as just a quintet, with Tommy Flanagan playing piano, Arthur Taylor playing drums, Paul Chambers and me. That was strange, and Miles couldn't really use that we just made that one tour. By the time we got back to New York he sent for everybody. At this time, Trane had come back to New York, it was '57 and he'd begun to work with Thelonious Monk at the old Five Spot: they had a sensational group with Shadow Wilson and Wilbur Ware, who was replaced by Aimed Abdul-Malik.

Anyhow, Miles called his original quintet back, and kept me on, so after I'd been with him two months we became a sextet.

I think I really began to grow there, because the band was such a classically good band: in fact the band was like a workshop; Miles really talked to everybody and told everybody what to not do, rather than what to do. He never told anybody what to play, he would just say, Man, you don't need to do that. And I heard him and dug it. I think up to that point I'd never played so well.

After I left the group, there was a lot still going on; but of course forming my own group with good musicians, in fact great musicians, who didn't sound like Philly Joe or Wynton Kelly. it made a difference, because a band is a marriage; a family, a team and so forth.

It was interesting being in Miles's band with Coltrane, because Trane at that time had an extremely light, fluid sound ; and my alto sound has always been influenced by the tenor, so it was heavy, and sometimes it was difficult to tell where one instrument stopped and the other instrument started, it would sound like one continual phrase.

It was interesting having Bill Evans in the band too. He replaced Red Garland. We used to go to Philadelphia to play, maybe three timet a year. Red had some very valid, personal reasons for not wanting to play in Philly. Miles would tell him, "Look man, you're playing in the band, you're supposed to go where the band goes" . But Red wouldn't go.

Miles had a little Mercedes 190SL. and one night he said to me, "Cannon, I'd like you to take a ride with me." Which is dangerous. I said okay. We were driving up the West Side Highway, and he said man have you ever heard Bill Evans. I said yes, I had because Nat had finished working with Woody herman and was freelancing in New York. He worked someplace in the Village with a drummer, and the drummer had hired Bill Evans. I went down to see him and I heard this cat and I said Wow, this is beautiful piano playing, and I met him and heard him and enjoyed him, Miles asked me what I thought of him and I said, "I think he's beautiful." He said, "Good, I'm going to take him to Philly." So Bill Evans joined the band to play Philadelphia, and we had so much fun with what we could do with him - other dimensions, other sounds - that Miles just told Red, "I'm going to keep Bill, because he can play everywhere we play." Somewhere at this point I began to take care of the band's business - collect the money, pay off the cats, keep the records, and so on. It was a good way to insure my own wages as well. Philly Joe had drawn up all his pay while we worked at Cafe Bohemia, so at the end of the gig he didn't have any money coming, and he insisted that he hadn't drawn everything that he had drawn, and I said, man, all you get is what you're supposed to get, and that's it. Philly for a long time had some problems, so he said, well, you play in Boston without me. So we went to Boston and Miles said, Joe ain't coming, right? Call Jimmy Cobb.

So I called Jimmy and he joined the band in Boston, 50 it was him, Paul Chambers, Bill Evans, Coltrane, me and Miles, That band stayed pretty much intact for six months', and Bill told Miles that he was making him feel uncomfortable, because Miles used to mess with him; not about his music or anything, but he used to call him "whitey" and stuff like that, So Bill put in his notice, and Miles hired Red back, We went into Birdland, and Red was the kind of cat who was notoriously late, We always started playing without a piano; in fact it became no problem at all, because we knew we were going to start playing without a piano. So one night before we went into Birdland, we went down to Brooklyn to see Oizzy's band, He had a fantastic band, with Sam Jones, Wynton Kelly, Candido, Sonny Stitt and a drummer whom I don't remember, Miles spent all evening listening to Wynton Kelly, So we'd been at Birdland about a week, Red was always late, and one night Wynton was there when we started, so Miles asked Wynton to Sit in, When Red came in, Wynton was playing, and Miles told Red, "Hey man, Wynton's got the gig," Just like that, I could never quite understand Red, Incidentally, last year I played a show at the Apollo Theater, and someone told me that Red Garland was downstairs, I went downstairs and Red was surrounded by musicians, everybody was hugging and talking. But he said, "Listen, I've got to go, I'm supposed to start work at nine o'clock," And it was ten then. He had a gig with Philly Joe and Wilbur Ware somewhere.

With this present group (Cannonball Adderley, alto saxophone; Nat Adderley, trumpet; George Duke, piano; Walter Booker, bass; Roy McCurdy, drums) we work all the time. Nat and I decided that we would get musicians who had that complete capability, and that we would play all the music we enjoy playing. Consequently we don't look down on any music, and we don't play anything simply for effect, Everything we play we choose to play, I announce to the audience that we don't take requests; we play things that we've recorded, so nobody has to tell me to play Mercy Mercy Mercy or anything like that, because we're going to play it anyhow. And we have a ball - that's the only way music can be for real, We do what we want to do and try to keep the audience with us. Because those are the only things that are important; whether we enjoy what we're doing and whether people enjoy what we're doing. But we can't gear anything to anybody because that's rank commercialism: "Here's an audience that likes this, so we're going to play this." That way you're not being a complete person, or a complete creative musician, and you're not really saying what you want to say.

What is your feeling about helping to continue jazz, by getting it to the kids - which I'm convinced is the only way it's going to continue?

We're just organizing something in Los Angeles that we call the L.A. Bandwagon. We've got a committee of folks together who agree that music - not just jazz, but all kinds of artistic music should be made available to people who are not able to or old enough to go to night clubs or to colleges and universities - because of course they won't hear it anywhere else, the radio scene is a total disaster

Yes, the government is so sticky about who and what is on the radio, but they never screen people for good taste when it comes to music, or whatever they present.

Well, the government doesn't have any taste. Who is going to screen it : President Nixon? Martha Mitchell? Because that's exactly who it would be if there were a screening committee. That would be the worst kind of censorship, I would never want to see a government agency designed to screen what was going out.

I wanted to set up some kind of amalgamation with the LA Bandwagon and Jazzmobile in New York, but Jazzmobile's employees seemed to think I was trying to take over, which was far from my intent, I don't want to be any kind of businessman, I don't want to be responsible for any community's music tastes; but I do feel that since I have some influence in the community where I live, so we formed a committee of which I am not a member, to organize, the LA Bandwagon, to take music all over the city.

As for jazz education, I do think it could be more comprehensive, to say the least, I've seen things such as: "Jazz Artist In Residence: Pete Fountain" which is criminal under the circumstances, I don't mean to cast aspersions on the musicianship of people like that: their technique, their knowledgeability or "the wonderfulness of their minds," to steal something from Bill Cosby. But to masquerade a program as "jazz" and then not have jazz people doing it there appears to me something sinful about that, It's like saying "we're going to have string quartet," and then putting in four guitar.

On the other hand, people like Cecil Taylor become jazz artists in residence at a university and it's a constant hassle: the kids are all for it, but the faculty gets uptight: especially the establishment music department.

Well, I don't care about those people anymore who have that kind of chauvinism, For anybody to question the musicianship, or the authenticity, or the preparation. of a man such as a Cecil Taylor is ridiculous, because Ceci plays piano as well as anybody playing anything He could have very easily been a concert pianisit had he chosen to be that, That kind of stupidity on the part of music faculty is one of the thing that makes kids incomplete, I've told kids for years that in order to play a musical instrument you should understand what music is all about And there's only one music; music speaks for itself; you can't departmentalize things or compartmentalize them, in order to sell it or "establish a commercial basis" or whatever you want to do; it does not change the fact that music is either going to be music or non-music (because there's no good or bad music to me ; there's only music and the rest of it is nonmusic. If we continue to propagate things like having kids sing Frere Jacques as public school music for children, it will be an unfortunate Situation. And music faculties are constantly keeping this kind of crap going on in our lives; and that is criminal. To complain about the presence of a genius, who is a creator, and who can create some atmosphere for music, and create some music there; in order to continue the same old pap is sinful.

I'm pretty well convinced that music educators, taken generally, still consider jazz to be whorehouse music.I don't mind that. Because, see, they're the ones who patronize the whorehouses.

I was talking to Merian McPartland about this, and she feels strongly that kids can be taught to improvise, I question this, How do you feel about that?

They can be taught the basis of improvisation, taught what improvisation is, and they can be taught what they're allegedly to improvise upon. You can improvise on three things: harmony things, melodic things, and rhythmic things. You can play the same melodic element but change the rhythm so that it's spaced differently; or you can play the same harmonic elements and change the melody; or you can play the same melody and put in completely different changes underneath. In improvisation you can deal with any of these elements, or all of them, if you want to.

But our principle is recomposition; which means that the player composes a solo as he goes along; he doesn't necessarily really improvise, which is why we came up with tunes like Charlie Parker's Ornithology, which is a copyrightable tune even though it was based on How High The Moon. So people can be taught to improvise, they can be taught what it's all about; but you don't teach them what to say or how to say it, just let them know what basis you' re dealing with.

I have a lot to learn about human nature, I guess because having been a teacher, I may or may not have been a good teacher, but I knew what I wanted to teach; I knew how I wanted my people to be able to play, and I never discriminated within music. Because music is only one thing, There is music out there, and it's up to us to grab it. Playing a musical instrument is only a means to an end. Because you can play well doesn't mean you're going to play any music on that instrument. We have some great technologists performing about, doing lots of things, who never say anything musical. Now I think people should have that kind of command of their instrument, and better, because that liberates them from having to think about how to play.

That approaches the question of today's free players; their music may be an extension of Ornette Coleman, and their music may be something new and important; but a lot of people wonder if they can really play, or are simply shocking.

I don't know; I enjoy a lot of things that are being said by people who are so-called "free" players or "avantgarde" or whatever you want to call it, and I approach them like I approach any other art. You see a painting and it can be by Michelangelo; but if you don't dig it, it doesn't make any difference who did it. My point is, cults of personality have long been one of the problems of playing music. That is, once you become as important to the creative world as a Duke Ellington, the cult of personality says that because you are Ellington, whatever you have to say is credible. And it is not necessarily so. Duke is my all-time favorite musician, he's the person for whom I have probably the most respect in the history of our art form - but I don't like everything he does, and I don't think that I'm supposed to. Because if I did, I wouldn't have any discretion myself. The same thing goes for, for example, Joseph Jarman or Archie Shepp; Archie's done some things that I like very much, and some things I thought were horrendous. But that's just me. I'm sure there are people who like some of the things I do and cannot understand why I do some other things. I don't want everybody to like me because it wouldn't give me any dimension. I like to be able to have my beginnings and my endings and I'd like my listeners to have the same privilege, and if they don't like something, don't give up to it!

Do you think what Miles is doing now is important in breaking new ground in music?

I don't know - but at the same time: I don't care. Miles is a lifestyle unto himself. There are people who emulate everything he does, so "breaking new ground" will mean that there are people who will emulate what he does, and maybe they'll get into other things. I don't care if a person is a revolutionary force, or whether he's perceived as so important that everything he's got to say automatically will be acceptable. I don't like everything he's doing now, but I think there are some great things in "Bitches Brew," and there are some other things that don't move me - but there again, that's me. There are people who love everything in it, and people who hate everything in it. My attitude to Miles is this: I like to hear him play his horn. I don't think he's particularly a great composer, but I like to hear him play anything, because he has a vitality and another dimension of communication in his instrument. And I'm going to like him even If I hate his band!

What about the period when you had Yusef Lateef in your group? Having two reedmen was sort of a departure. How did you happen to add him?

Yusef is one of the sweetest human beings I've ever encountered. A professional musician who has an architectural approach to playing music; he really builds from a foundation. He's sort of like Miles in that whatever he plays through his horn is worth listening to. We wanted to have Yusef in the band, but we didn't know how to cope with it at first; in fact we did some "small band/big band" kind of things, based on the old John Kirby principle, completely written. We did albums with arrangements of Dizzy Gillespie big band pieces, arranged for the sextet. When Charles Lloyd replaced Yusef we couldn't do that, because his sound and his feel for playing with other people wasn't quite the same, so we became six soloists rather than an ensemble. But it wasn't particularly unusual; Miles had a sextet with two saxophone players.

I'm not thinking of changing my present quintet format, because my brother and I play well together. I think if we were to split up I would just not have a band again. Having a band is a luxury; it gives you the chance to play your music and to luxuriate in an atmosphere of excellence. I care a lot more about having a good band than I do about the money. I always try to get good guys and keep them a long time.

Duke always said that he looked upon his band as a way of hearing his new compositions; as a workshop more than a commercial proposition.

Yes, If he couldn't have subsidized his band he could never have operated. A band can't make enough money to function just on what it earns (in performance fees). We have to take money from publishing, from records, everywhere we can get it in order to keep going.

What would you say your band you and Nat had in Florida, before you came to New York, sounded like?

We were strongly influenced by blues bands: Louis Jordan, Eddie Cleanhead Vinson, bands like that. It was a small group like we have now. Except for the quality of the musicianship it sounded quite a bit like the records we first made when we got to New York, except that we played more real, fundamental blues. We could and did play rhythm and blues; we had to cover the hit records just to survive. There was no market for a jazz group in Fort - Lauderdale, Florida, or Tallahassee !You can forget it ! But we played jazz anyway, and also the current favorites because it was necessary; we had singers. That was just the way that it was. But we used to play things by Dizzy, and Miles, and Bird - but they would come right behind Caledonia, or Cherry Red Blues.

To provide a sketch of this colorful, articulate jazzman, here are a number of excerpts from interviews with Julian reassembled in chronological order. Also included are essential comments from Nat Adderley pertaining to Julian's youth and New York City debut. These interviews are extracted from a number periodicals referenced in the Bibliography.

http://walktall.halleonardbooks.com/

Walk Tall: The Music and Life of Julian "Cannonball" Adderley by Cary Ginell, Hal Leonard Books, 2013

Cannonball Adderley introduces his 1967 recording of "Walk Tall," by saying, "There are times when things don't lay the way they're supposed to lay. But regardless, you're supposed to hold your head up high and walk tall." This sums up the life of Julian "Cannonball" Adderley, a man who used a gargantuan technique on the alto saxophone, pride in heritage, devotion to educating youngsters, and insatiable musical curiosity to bridge gaps between jazz and popular music in the 1960s and '70s. His career began in 1955 with a Cinderella-like cameo in a New York nightclub, resulting in the jazz world's looking to him as "the New Bird," the successor to the late Charlie Parker. But Adderley refused to be typecast. His work with Miles Davis on the landmark Kind of Blue album helped further his reputation as a unique stylist, but Adderley's greatest fame came with his own quintet's breakthrough engagement at San Francisco's Jazz Workshop in 1959, which launched the popularization of soul jazz in the 1960s. With his loyal brother Nat by his side, along with stellar sidemen, such as keyboardist Joe Zawinul, Adderley used an engaging, erudite personality as only Duke Ellington had done before him. All this and more are captured in this engaging read by author Cary Ginell.

Cannonball Adderley Sextet in Switzerland 1963 - "Bohemia After Dark":

Cannonball Adderley Sextet- "Bossa Nova Nemo" (aka "Jive Samba"):

Cannonball Adderley Quintet:

Nat Adderley, Yusef Lateef, Joe Zawinul, Sam Jones, Louis Hayes from Oscar Brown Jr's 'Jazz Scene'--1962

Jazz Casual - Cannonball Adderley Quintet (1961):

Cannonball Adderley - Live 1963 Jazz Icons DVD:

Switzerland (Tracklist):

1. Jessica's Day

2. Angel Eyes

3. Jive Samba

4. Bohemia After Dark

5. Dizzy's Business

6. Trouble In Mind

7. Work Song

8. Unit 7

Germany (Tracklist):

9. Jessica's Day

10.Brother John

11. Jive Samba

Cannonball Adderley - "Somethin' Else"-- (1958) [FULL ALBUM]:

Cannonball Adderley--alto saxophone

Miles Davis — trumpet

Hank Jones — piano

Sam Jones — bass

Art Blakey — drums

Cannonball Adderley-- "Brother John 1963":

The Cannonball Adderley Sextet - In New York (1962):

Tracklist:

A1 Introduction by Cannonball 0:00

A2 Gemini 2:00

A3 Planet Earth 13:42

B1 Dizzy's Business 21:43

B2 Syn-anthesia 28:45

B3 Scotch and Water 35:49

B4 Cannon's Theme 41:45

Cannonball Adderley Quintet--"This Here":

"Thank you very much, ladies and gentlemen. Now it's time to carry on some. Can we have the lights out please, for atmosphere? Now we're about to play a new composition, by our pianist, Bobby Timmons. This one is a jazz waltz, however, it has all sorts of properties. It's simultaneously a shout and a chant, depending upon whether you know anything about the roots of church music, and all that kinda stuff - meaning soul church music - I don't mean, uh, Bach chorales and so, that's different. You know what I mean? This is SOUL, you know what I mean? You know what I mean? Allright. Now we gonna play this, by Bobby Timmons. It's really called "This Here". However, for reasons of soul and description, we have corrupted it to become "Dish-ere". So that's the name: "Dish-ere"

--Introduction by Cannonball Adderley

Cannonball Adderley -- alto saxophone

Nat Adderley -- cornet

Bobby Timmons -- piano

Sam Jones -- bass

Louis Hayes -- drums

BEAUTIFUL CLASSIC 1961 RECORDING BY NANCY WILSON AND CANNONBALL ADDERLEY QUINTET

CAPITOL RECORDS:

Year: 1961

Label: Capitol

An excellent collaboration of the Nancy Wilson voice with the Cannonball Adderley alto sax from the early '60s. While this 1961 recording was the first time Wilson was with Adderley in the studio, it was not the first time they had worked together. After singing with Rusty Bryant's band, Wilson had worked with Adderley in Columbus, OH. (It was there that Adderley encouraged her to go to N.Y.C. to do some recording, eventually leading to this session.) Not entirely a vocal album, five of the 12 cuts are instrumentals. A highlight of the album is the gentle cornet playing of Nat Adderley behind Wilson, especially on "Save Your Love for Me" and on "The Old Country." Cannonball Adderley's swinging, boppish sax is heard to excellent effect throughout. Joe Zawinul's work behind Wilson on "The Masquerade Is Over" demonstrates that he is a talented, sensitive accompanist. On the instrumental side, "Teaneck" and "One Man's Dream" are especially good group blowing sessions. On the other end of the spectrum, Adderley's alto offers a lovely slow-tempo treatment of the Vernon Duke-Ira Gershwin masterpiece, "I Can't Get Started." To keep the listeners on their musical toes, the first couple of bars of "Save Your Love for Me" are quotes from "So What" from the Miles Davis Sextet seminal Kind of Blue session. Given the play list and the outstanding artists performing it, why any serious jazz collection would be without this classic album is difficult to comprehend.

Cannonball Adderley Quintet "Mercy Mercy Mercy" (1966):

All,

A GREAT SPOKEN INTRODUCTION BY THE ALWAYS SOULFUL AND ELOQUENT CANNONBALL ADDERLEY TO A GREAT SONG PLAYED BEAUTIFULLY BY A GREAT, GREAT BAND. THE YEAR IS 1966. LISTEN AND REVEL IN WHAT THIS MUSIC ALWAYS DOES AND EVOKES AT ITS VERY BEST NO MATTER WHAT 'STYLE" OR 'GENRE" IT HAPPENS TO USE OR REFERENCE. YESSSSS...

Kofi

Cannonball Adderley Quintet - "Mercy, Mercy, Mercy" (1966):

"You know, sometimes we're not prepared for adversity. When it happens sometimes, we're caught short. We don't know exactly how to handle it when it comes up. Sometimes, we don't know just what to do when adversity takes over. And I have advice for all of us, I got it from my pianist Joe Zawinul who wrote this tune. And it sounds like what you're supposed to say when you have that kind of problem. It's called Mercy...Mercy...Mercy..."

--Cannonball Adderley "Live at the Club" (Capitol, 1966)

Cannonball Adderley Quintet:

Cannonball Adderley (alto saxophone);

Nat Adderley (cornet)

Joe Zawinul (acoustic & electric pianos);

Victor Gaskin (bass)

Roy McCurdy (drums)