ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2018/06/memphis-minnie-1897-1973-legendary.html

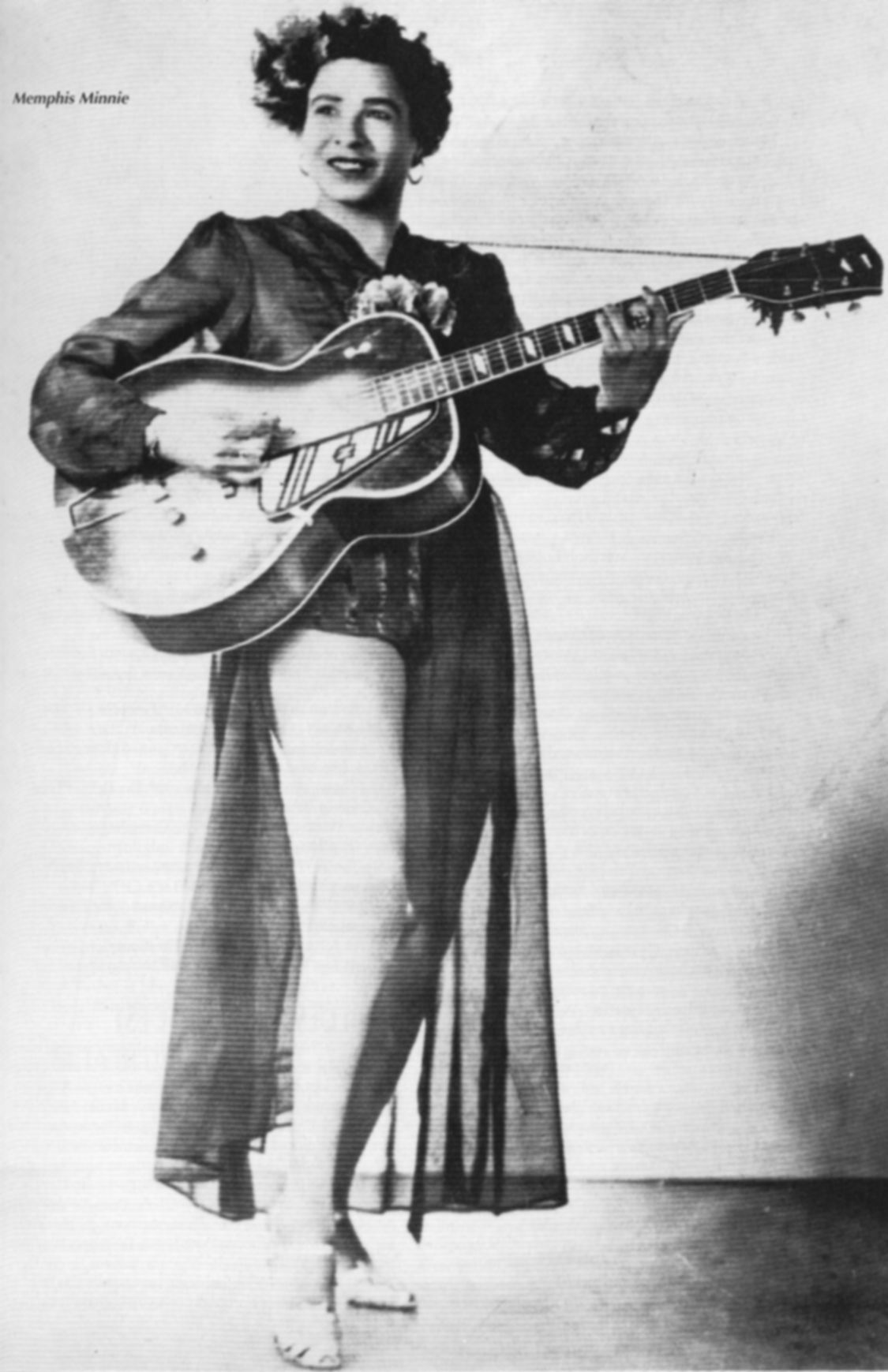

Memphis Minnie

Blues artist whose music was rooted in Memphis and Chicago styles; one of the first important female blues guitarists.

(1897- 1973)

Biography by Barry Lee Pearson

Tracking down the ultimate woman blues guitar hero is problematic because woman blues singers seldom recorded as guitar players and woman guitar players (such as Rosetta Tharpe and Sister O.M. Terrell) were seldom recorded playing blues. Excluding contemporary artists, the most notable exception to this pattern was Memphis Minnie. The most popular and prolific blueswoman outside the vaudeville tradition, she earned the respect of critics, the support of record-buying fans, and the unqualified praise of the blues artists she worked with throughout her long career. Despite her Southern roots and popularity, she was as much a Chicago blues artist as anyone in her day. Big Bill Broonzy recalls her beating both him and Tampa Red in a guitar contest and claims she was the best woman guitarist he had ever heard. Tough enough to endure in a hard business, she earned the respect of her peers with her solid musicianship and recorded good blues over four decades for Columbia, Vocalion, Bluebird, OKeh, Regal, Checker, and JOB. She also proved to have good taste in musical husbands as indicated in her sustained working marriages with guitarists Casey Bill Weldon, Joe McCoy, and Ernest Lawlars. Their guitar duets span the spectrum of African-American folk and popular music, including spirituals, comic dialogs, and old-time dance pieces, but Memphis Minnie's best work consisted of deep blues like "Moaning the Blues." More than a good woman blues guitarist and singer, Memphis Minnie holds her own against the best blues artists of her time, and her work has special resonance for today's aspiring guitarists.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memphis_MinnieMemphis Minnie

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Lizzie Douglas (June 3, 1897 – August 6, 1973), better known as Memphis Minnie, was a blues guitarist, vocalist, and songwriter whose recording career lasted for over three decades. She recorded around 200 songs, some of the best known being "When the Levee Breaks", "Me and My Chauffeur Blues", "Bumble Bee" and "Nothing in Rambling".

Childhood

Douglas was born on June 3, 1897, probably in Tunica County, Mississippi,[1] although she claimed to have been born in New Orleans, Louisiana and raised in the Algiers neighborhood.[2] She was the eldest of 13 siblings. Her parents, Abe and Gertrude Douglas, nicknamed her Kid when she was young, and her family called her that throughout her childhood. It is reported that she disliked the name Lizzie.[3] When she first began performing, she played under the name Kid Douglas.

When she was seven years old, she and her family moved to Walls, Mississippi, south of Memphis, Tennessee. The following year, she received her first guitar, as a Christmas present. She learned to play the banjo by the age of 10 and the guitar by the age of 11, when she started playing at parties.[2] The family later moved to Brunswick, Tennessee. After Minnie's mother died, in 1922, Abe Douglas moved back to Walls, where he died in 1935.[4]

Career

In 1910, at the age of 13, she ran away from home to live on Beale Street, in Memphis. She played on street corners for most of her teenage years, occasionally returning to her family's farm when she ran out of money.[5] Her sidewalk performances led to a tour of the South with the Ringling Brothers Circus from 1916 to 1920.[6] She then went back to Beale Street, with its thriving blues scene, and made her living by playing guitar and singing, supplementing her income with sex work (at that time, it was not uncommon for female performers to turn to sex work out of financial need).[7]

She began performing with Kansas Joe McCoy, her second husband, in 1929. They were discovered by a talent scout for Columbia Records, in front of a barber shop, where they were playing for dimes.[8] She and McCoy went to record in New York City and were given the names Kansas Joe and Memphis Minnie by a Columbia A&R man.[9] Over the next few years she and McCoy released a series of records, performing as a duet. In February 1930 they recorded the song "Bumble Bee" for the Vocalion label, which they had already recorded for Columbia but which had not yet been released.[10] It became one of Minnie's most popular songs; she eventually recorded five versions of it.[11] Minnie and McCoy continued to record for Vocalion until August 1934, when they recorded a few sessions for Decca Records. Their last session together was for Decca, in September.[12] They divorced in 1935.[2]

An anecdote from Big Bill Broonzy's autobiography, Big Bill Blues, recounts a cutting contest between Minnie and Broonzy in a Chicago nightclub on June 26, 1933, for the prize of a bottle of whiskey and a bottle of gin. Each singer was to sing two songs; after Broonzy sang "Just a Dream" and "Make My Getaway," Minnie won the prize with "Me and My Chauffeur Blues" and "Looking the World Over".[13] Paul and Beth Garon, in their biography Woman with Guitar: Memphis Minnie's Blues, suggested that Broonzy's account may have combined various contests at different dates, as these songs of Minnie's date from the 1940s rather than the 1930s.[14]

By 1935, Minnie was established in Chicago and had become one of a group of musicians who worked regularly for the record producer and talent scout Lester Melrose.[15] Back on her own after her divorce from McCoy, Minnie began to experiment with different styles and sounds. She recorded four sides for Bluebird Records in July 1935, returned to the Vocalion label in August, and then recorded another session for Bluebird in October, this time accompanied by Casey Bill Weldon, her first husband. By the end of the 1930s, in addition to her output for Vocalion, she had recorded nearly 20 sides for Decca and eight sides for Bluebird.[12] She also toured extensively in the 1930s, mainly in the South.[15]

In 1938, Minnie returned to recording for the Vocalion label, this time accompanied by Charlie McCoy, Kansas Joe McCoy's brother, on mandolin.[12] Around this time she married the guitarist and singer Ernest Lawlars, known as Little Son Joe. They began recording together in 1939, with Son adding a more rhythmic backing to Minnie's guitar.[15] They recorded for Okeh Records in the 1940s and continued to record together through the decade. By 1941 Minnie had started playing electric guitar,[16] and in May of that year she recorded her biggest hit, "Me and My Chauffeur Blues". A follow-up date produced two more blues standards, "Looking the World Over" and Lawlars's "Black Rat Swing" (issued under the name "Mr. Memphis Minnie"). In the 1940s Minnie and Lawlars continued to work at their "home club," Chicago's popular 708 Club, where they were often joined by Broonzy, Sunnyland Slim, or Snooky Pryor, and also played at many of the other better-known Chicago nightclubs. During the 1940s Minnie and Lawlars performed together and separately in the Chicago and Indiana areas.[17] Minnie often played at "Blue Monday" parties at Ruby Lee Gatewood's, on Lake Street.[18] The poet Langston Hughes, who saw her perform at the 230 Club on New Year's Eve, 1942, wrote of her "hard and strong voice" being made harder and stronger by amplification and described the sound of her electric guitar as "a musical version of electric welders plus a rolling mill."[19]

Later in the 1940s, Minnie lived in Indianapolis and Detroit. She returned to Chicago in the early 1950s.[20] By the late 1940s, clubs had begun hiring younger and cheaper artists, and Columbia had begun dropping blues artists, including Memphis Minnie. Unable to adapt to changing tastes, she moved to smaller labels, such as Regal, Checker, and J.O.B.[21]

Later life and death

Minnie continued to record into the 1950s, but her health began to decline. With public interest in her music waning, she retired from her musical career, and in 1957 she and Lawlars returned to Memphis.[22] Periodically, she appeared on Memphis radio stations to encourage young blues musicians. In 1958 she played at a memorial concert for Big Bill Broonzy.[23] As the Garons wrote in Woman with Guitar, "She never laid her guitar down, until she could literally no longer pick it up." She suffered a stroke in 1960, which left her confined to a wheelchair. Lawlars died the following year, and Minnie had another stroke a short while after. She could no longer survive on her Social Security income. Magazines wrote about her plight, and readers sent her money for assistance.[24][25] She spent her last years in the Jell Nursing Home, in Memphis, where she died of a stroke in 1973.[26] She is buried at the New Hope Baptist Church Cemetery, in Walls, DeSoto County, Mississippi.[2] A headstone paid for by Bonnie Raitt was erected by the Mount Zion Memorial Fund on October 13, 1996, with 34 family members in attendance, including her sister Bob. The ceremony was taped for broadcast by the BBC.[27] Her headstone is inscribed:

Lizzie "Kid" Douglas Lawlers aka Memphis Minnie

The inscription on the back of her gravestone reads:

The hundreds of sides Minnie recorded are the perfect material to teach us about the blues. For the blues are at once general, and particular, speaking for millions, but in a highly singular, individual voice. Listening to Minnie's songs we hear her fantasies, her dreams, her desires, but we will hear them as if they were our own.[28]

Character and personal life

Minnie was known as a polished professional and an independent woman who knew how to take care of herself.[5] She presented herself to the public as being feminine and ladylike, wearing expensive dresses and jewelry, but she was aggressive when she needed to be and was not shy when it came to fighting.[29] According to the blues musician Johnny Shines, "Any men fool with her she'd go for them right away. She didn't take no foolishness off them. Guitar, pocket knife, pistol, anything she get her hand on she'd use it".[5] According to Homesick James, she chewed tobacco all the time, even while singing or playing the guitar, and always had a cup at hand in case she wanted to spit.[30] Most of the music she made was autobiographical; Minnie expressed a lot of her personal life in music.[citation needed]

Minnie was married three times,[2] although no marriage certificates have been found.[31] It is believed that her first husband was Casey Bill Weldon, whom she married in the early 1920s. Her second husband was the guitarist and mandolin player Kansas Joe McCoy, whom she married in 1929.[2] They filed for divorce in 1934. McCoy's jealousy of Minnie's professional success has been given as one reason for the breakup of their marriage.[32] Minnie was also reported to have lived with a man known as "Squirrel" in the mid- to late 1930s.[33] Around 1938 she met the guitarist Ernest Lawlars (Little Son Joe), who became her new musical partner, and they married shortly thereafter;[34] Minnie's union records, covering 1939 onwards, give her name as Minnie Lawlars.[35] He dedicated songs to her, including "Key to the World", in which he addresses her as "the woman I got now" and calls her "the key to the world."

Minnie was not religious and rarely went to church. The only time she was reported to have gone to church was to see a gospel group perform.[32] She was baptized shortly before she died, probably to please her sister Daisy Johnson.[36] A house in Memphis where she once lived, at 1355 Adelaide Street, still exists.[37]

Legacy

Memphis Minnie has been described as "the most popular female country blues singer of all time".[38] Big Bill Broonzy said that she could "pick a guitar and sing as good as any man I've ever heard."[13] Minnie lived to see a renewed appreciation of her recorded work during the revival of interest in blues music in the 1960s. She was an influence on later singers, such as Big Mama Thornton, Jo Ann Kelly[2] and Erin Harpe.[39] She was inducted into the Blues Foundation's Hall of Fame in 1980.[40]

"Me and My Chauffeur Blues" was recorded by Jefferson Airplane on their debut album, Jefferson Airplane Takes Off, with Signe Anderson as lead vocalist. "Can I Do It for You" was recorded by Donovan in 1965, under the title "Hey Gyp (Dig the Slowness)". A 1929 Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe McCoy song, "When the Levee Breaks",[41] was adapted (with altered lyrics and a different melody) by Led Zeppelin and released in 1971 on their fourth album. "I'm Sailin'" was covered by Mazzy Star on their 1990 debut album, She Hangs Brightly. Her family is currently suing record companies and some artists for royalties and for using her music without permission. In 2007, Minnie was honored with a marker on the Mississippi Blues Trail in Walls, Mississippi.[42]

Songs

Discography

Compilations

1964 Blues Classics by Memphis Minnie blues Blues Classics

c. 1967 Early Recordings with Kansas Joe McCoy, vol. 2 blues Blues Classics

1968 Love Changin' Blues: 1949, Blind Willie McTell and Memphis Minnie blues Biograph Records

1973 1934–1941 blues Flyright Records

1973 1941–1949 blues Flyright Records

1977 Hot Stuff: 1936–1949 blues Magpie Records

1982 World of Trouble blues Flyright Records

1983 Moaning the Blues blues MCA Records

1984 In My Girlish Days: 1930–1935 blues Travelin' Man

1987 1930–1941 blues Old Tramp

1988 I Ain't No Bad Gal blues CBS

1991 Hoodoo Lady (1933–1937) blues Columbia

1994 In My Girlish Days blues Blues Encore

1996 Let's Go to Town blues Orbis

1997 Queen of the Blues blues Columbia

1997 "The Queen of the Blues": 1929–1941 blues Frémeaux & Associés

2000 Pickin' the Blues blues Catfish Records

2003 Me and My Chauffeur Blues blues Proper Records Ltd.

2007

Complete Recorded Works 1935–1941 in Chronological Order, vol. 1, 10 January to 31 October 1935 blues Document Records

unknown Night Time Blues, Ma Rainey and Memphis Minnie blues History

2022 The Rough Guide to Memphis Minnie - Queen of the Country Blues blues World Music Networks

Sources

- Garon, Paul, and Garon, Beth (1992). Woman with Guitar: Memphis Minnie's Blues. New York: Da Capo Press.

- Harris, S, (1989). Blues Who's Who. 5th paperback ed. New York: Da Capo Press.

External links

https://memphisminnie.com/

Memphis Minnie

Guitar Queen, Hoodoo Lady and Songster

Memphis Minnie: Her Story

by Del Rey

Guitar Queen. Hoodoo Lady. Master finger-style guitar player. Elizabeth “Kid” Douglas, known as Memphis Minnie was an intricate guitarist, an astute songwriter and a stylistic innovator. Her work (over 200 recordings) leads the way through the development of blues guitar playing, starting with her first recordings in 1929. There have been a number of re-releases of her work, and her songs, especially Chauffeur Blues, When The Levee Breaks, Black Rat Swing and What’s The Matter With The Mill? are repertoire perennials. A full-length biography, “Woman With Guitar: Memphis Minnie’s Blues” by Paul and Beth Garon was published by DaCapo press in 1998 with a 2nd edition in 2014. Yet she remains comparatively unknown and under-studied in relation to her influence and importance to the development of blues music and guitar playing. Why has this musician , with her enormous body of recordings, who was well-loved by the Black blues audiences of the ’30s and ’40s been comparatively ignored by later, whiter audiences?

Perhaps it’s because Memphis Minnie doesn’t fit the myth of the young, tragic, haunted blues man and she is too complex of a character to be easily marketed. She shaped a life very different from the limited possibilities offered to the women of her time. She lived a long life, was at her best in middle age, and would spit tobacco wearing a chiffon ball gown. Memphis Minnie’s music remained popular over two decades because it was lyrically and instrumentally in tune with the lives of Black Americans. It remains vital and influential today because of her inventive, rhythmic guitar playing and her songs, which capture people and events and bring them to life across the years.

Starting in 1929, her records lead us through twenty years of recorded blues and illustrate her life, as she moved from the rural South to urban Chicago. Musically there were three basic phases to her style: the duet years with Kansas Joe, the “Melrose” band sound of the late thirties and early forties, and her later electric playing. She was always a finger picker, and played in Spanish (DGDGBD) and standard tunings, often using a capo. For guitar players, the first part of her career is definitely the most inspiring, as her inventive variations make masterpieces of tunes like “When The Levee Breaks”(1930) or “Let’s Go To Town”(1931). In terms of her influence on the development of blues, she was an important player in the Chicago clubs during the ’40s when musicians like Muddy Waters, Jimmy Rodgers and Johnny Shines, were coming up.

African, European and Indigenous traditions had begun to coalesce into the blues in the South much earlier than the ’20s, but our perception of history is usually based on recorded history: what gets recorded, written about and incorporated into our accepted common memory. In our society, what is deemed important is often what has commercial value, and that is precisely what pushes blues off the front porch and onto 78s. in the ’20s when record companies first perceived a market for the style. The commercial success of Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” in 1920, alerted record companies to the existence of black record buyers. The companies began to seek out and record other singers in the same vaudevillian genre. Theatrical, glamorous blues queens dominated the first decade of recorded blues. Primarily an urban, piano based music, it was perfect for the speciously prosperous “Jazz Age” atmosphere of the twenties, during which the music of Black Americans became increasingly influential to the mainstream.

As the realities of boom and bust economics became universal after the stock market crash of 1929, record companies began to seek out rural, guitar based music. Perhaps it was cheaper to record a country boy’s guitar than an established vaudeville professional. Perhaps the glamour of beaded and tiaraed blues royalty seemed wrong for a time of soup kitchens and extensive poverty, although blues listeners surely always lived in poverty. It is difficult to tell whether audiences demanded different music, or if they bought what was promoted and available. In any case, in 1929 Elizabeth Douglas, professionally known as Memphis Minnie, made her debut on record.

Memphis Minnie (known to her family as “Kid”) was born June 3, 1897, in Algiers Louisiana, the oldest of 13 brothers and sisters. She grew up in Walls Mississippi, about 20 miles from Memphis on Route 61, in a time before rural electrification and national media created a mass culture. Music (like most things) was still homemade: for entertainment, people threw parties–suppers where roast shoat, custard pies and candy sticks dipped in corn whiskey got worked off dancing the “shoofly”, the “scratch” and the “shimmy-she-wobble.” Minnie started playing banjo when she was seven years old, and was influenced by the string bands which played for dancers who partied all night and hit the fields at dawn. She got her first guitar at age ten or 11. The wretchedness of hitting the fields at dawn led some to try life with “the starvation box”, as Roosevelt Sykes called the guitar. A musicians’ life was an escape from endless labor, looked on with both admiration and resentment by the field hands and workers in the audience. The official job prospects for black women were limited to domestic service and farm work both of which demanded grueling labor and subservience for low pay. Memphis Minnie was never interested in physical labor and she began to play on the streets of Memphis and the towns surrounding Walls soon after getting her first guitar.

In 1907 a blues musician played in all kinds of places: house parties, barrel houses, work camps, traveling shows. It’s hard to imagine how prevalent live music was before the advent of consumer electronics. Anywhere you hear canned music now would probably have had a live musician–well, maybe not elevators. Sometimes a blues musician got paid with an apple or a can of sardines, sometimes she made as much as a hundred dollars. The traveling musician was often a lonely stranger, an outsider who might not know the local situation, and musicians often teamed up. One of Memphis Minnie’s first musical partnerships was with Willie Brown, who is is better known for his association with Charlie Patton. Brown provided the solid rhythm and bass lines she seemed to require from all her men. She and Brown began playing together around 1915 in the resort town of Bedford Mississippi, where tourists could take a ferryboat trip around nearby Lake Cormorant. Minnie and Brown would get aboard and entertain the primarily white pleasure seekers, once debarking at Biggs Arkansas with $119 in tips. They mixed blues with pop tunes, her favorite cover being “What Makes You Do Me Like You Do Do Do”. She also played for dances and store promotions. In guitarist Willie Moore’s recollection, (reported in Stephen Calt and Gayle Dean Wardlow’s King of the Delta Blues; The Life and Music of Charlie Patton, 1988 Rock Chapel Press) Minnie was the better guitarist, —“She was a guitar king”—-he said—- although Brown was better known.

Minnie is rumored to have joined a Ringling Bros. circus in Clarksdale around 1917. There were traveling shows of all kinds, from lowdown to grand, but they all included comedy, dancers and musicians of every type from jug bands to elegant pianists. Associating with circus and vaudeville performers must have been a step up for a street musician, and probably helped Minnie make her music more of an act.

Minnie settled Memphis in the early ’20s. Beale Street was at this time an important bit of pavement, a place where segregation forced dentists and church ladies to mix with gamblers and whores, creating quite a lively atmosphere.

Minnie worked the streets and parks with Jed Davenport’s Beale Street Jug Band, and her guitar playing was influenced by the popular jug band musician Frank Stokes, who’s guitar duets with Dan Sane are very similar to Minnie’s early style.

By 1929, Douglas had married another guitar-player, Joe McCoy, who was a good singer and guitarist, but reputedly a jealous fellow. One photo of the two has Minnie in an florid, drop-waisted day dress, with straightened flapper hair, looking distinctly unsteady on her feet as she grabs hold of a grim-faced Joe’s padded shoulder. They were playing together in a Beale street barbershop when a scout from Columbia offered to record them in New York. Their first session was on June 18, 1929, two weeks after Minnie’s 32nd birthday. The silly yet haunting “Bumble Bee Blues” became the popular song from that session– so popular that Minnie recorded several different versions of it for different labels. Columbia was responsible for bestowing their geographical monikers: Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe. Minnie used the name both publicly and privately, although her family still called her Kid.

Minnie and Joe began a steady series of recording dates in New York, and Memphis, first for Columbia, later for Vocalion, Decca, Okeh and Bluebird. Kansas Joe,and Minnie were guitarists of equal ability, and the interplay of their instruments is like a great conversation: with both of them switching between treble and bass. The back-up parts are as interesting as the melody parts, especially on tunes like “When the Levee Breaks”, recorded in 1929, in Spanish tuning capoed to Bb (the third fret) or “Crazy Crying Blues” from 1931, also in Spanish, capoed to C# (the sixth fret). It’s rural party music, with doubling of parts helping punch the sound through in a loud environment in the pre-electric age.

Minnie was quick to embrace the latest technologies in order to be heard above the crowds She was one of the first blues players to use a National in 1929, and to play an electric wood body National and various electric guitars in the ’40s and ’50s.

Minnie’s fame began to spread northward by word of mouth and records. Apparently people in Chicago, who had never actually seen her play, were skeptical–so far no women instrumentalists had become prominent on the tough country blues circuit, although some (like guitarist Mattie Delaney), made a brief, tantalizing appearance, then disappeared. Minnie’s arrival in Chicago precipitated a showdown with the reigning King, Big Bill Broonzy.1. In 1933, when Big Bill Broonzy was very popular in Chicago, a blues contest between him and Memphis Minnie took place in a night club. As Broonzy tells the story, in his autobiography Big Bill Blues, (Cassell and Co.London 1956) a jury of fellow musicians awarded Minnie the prize of a bottle of whiskey and a bottle of gin for her performance of “Chauffeur Blues” and “Looking the World Over”. Bill grabbed half the prize (the bottle of whiskey) and took it off to drink under a table. Two of the judges, John Estes and Richard Jones hoisted the victorious Minnie on their shoulders while Kansas Joe remarked sourly “Put her down. She can walk”. Broonzy and Minnie became good friends, and played together locally and on the road.

Joe and Minnie based themselves in Chicago throughout the early ’30s, playing clubs like the DeLisa and the Music Box, recording both together and separately. Their marriage and musical partnership fell apart in the mid-thirties, around the same time Minnie became increasingly featured as a guitarist, vocalist and songwriter.

Minnie toured a great deal in the ’30s, mostly in the south. It was during this period that Bob Wills and some of his Texas Playboys saw her playing in Texas; they would later make her “What’s The Matter With The Mill?” a part of their repetoire.

Some of her mid-thirties recordings incorporate piano, drums and a few horn players and after 1935, she joined the group of musicians who worked regularly for Lester Melrose, a producer and talent scout who supplied blues artists for a number of labels. He standardized the sound of his blues offerings, using musicians like Tampa Red, Big Bill Broonzy and Thomas Dorsey to back up different artists. In the studio Minnie worked with pianist Black Bob, drummer Fred Williams and other instrumentalists, from the occasional trumpeter to lap-steel and mandolin. During this period Minnie began playing much less; the guitar no longer combines bass, treble and rhythm parts, leaving that to the other instruments, and instead starts to sound more like what we think of as blues today, with soulful bends and well-placed twangs on songs like the swing influenced “Good Morning”(1936) and “Hot Stuff”(1937), both of which she played in standard tuning.

In 1939 she married Ernest “Little Son Joe” Lawlars, a Memphis based guitarist who was her partner for the next 23 years. Her recordings with Son Joe are in duet style, with piano, bass or drums added on some sessions. Although Son’s playing has an impelling pulse and solidness their instrumental interplay is less intricate than what Minnie and Kansas Joe recorded. Some of Minnie’s best lyrics come from this period, like those in the autobiographical “In My Girlish Days”, (1941)which she played in G in standard tuning. In the same session Son Joe sang “Black Rat Swing”, and sounded so much like Minnie he must have borrowed her chewing tobacco. Minnie’s fantastically vituperative vocal delivery on some songs may be due in part to having a cheek full of Copenhagen. She was known to spit mid-song without losing a beat.

Their sessions in May and December of 1941 fused her more urban sound, (for example her vocal delivery on “Nothin’ In Ramblin”), with Son Joe’s back-up style, which combined big chords with an insistent beat to create a chunky swing feel. He seems to play with a flatpick, mostly in standard tuning. The forties treated Minnie and Son Joe well and they performed both together and separately depending on finances, (they could make more money playing separate gigs). Minnie, presided over Blue Monday parties at Ruby Lee Gatewood’s Tavern playing an electrified National arch top in front of a band that included bass and drums. The poet Langston Hughes saw her perform New Year’s Eve 1942, at the 230 Club, and was thoroughly overwhelmed by her “scientific” (i.e. loud) sound. He described the sound of her electric guitar as ” a musical version of electric welders plus a rolling mill”. Clearly she had by that time embraced the next phase of the blues.

The poet Langston Hughes was overwhelmed by Minnie’s “rolling mill” sounds. Courtesy Vintage Books USA.

As a working musician, Minnie’s guitar style evolved partly in response to the kind of places she played and the people for whom she played. Her recorded output is not necessarily the same as her live set. Record companies are remarkably mono-thematic about marketing, and Minnie, like many other blues musicians, played jazz and swing tunes as well, although there are only hints of this in her 200 recorded sides. Paul and Beth Garon include a fascinating photo of Minnie’s set list in “Woman with Guitar”, that includes songs like “Marie”, “Woody Woodpecker”, Lady Be Good”, “I Love You For Sentimental Reasons” and “How High The Moon.” Son Joe and Minnie played until their health broke down. Even though sales of their recordings slowed down by the end of the forties, their audience remained available to them in the clubs. Styles were shifting toward jump blues bands and by the mid ’50s the record industry had changed irrevocably with the fabrication of rock and roll. The major labels pulled out of the blues market, and Minnie’s last recordings were for Regal in 1949. The best tune of that session, in which Minnie generally sounded tired and overwrought, is “Downhome Girl” which is sung with great feeling but too many notes on the wrong frets. These sides were never issued by Regal but can now be heard on the Biograph CD Memphis Minnie: Early Rhythm and Blues 1949.

In 1957 Minnie had an incapacitating heart attack, and Son Joe became too ill to perform. They returned to Memphis where Minnie’s sister Daisy took care of them. After Son Joe’s death in 1962 Minnie lived in a nursing home until she died on August 6,1973, at the age of 76.

Although Memphis Minnie is gone, her music is still full of life, and her influence can be heard in the music of the many Chicago blues players who came up during her reign in the thirties and forties. Her guitar playing embodies the best of blues: it takes a simple form and makes each iteration fresh and inventive. Many of her hits are still standards in more than one genre, like “What’s The Matter With The Mill?”, “Chauffeur Blues” or “When The Levee Breaks”. Her recordings were reissued by Chris Strachwitz on Blues Classics in the late sixties, and had a profound influence on several young musicians, particularly the late guitarist JoAnn Kelly, and Maria Muldaur who still sings Minnie’s songs today. Suzy Thompson, who plays blues fiddle and guitar is another current interpreter of Minnie’s songs.

Minnie’s voice is rarely heard, even today: it is the voice of an independent, childless woman, an artist who never puts up with abuse, and who managed to find pleasure while living through tough times.

by Del Rey copyright 1997 Hobemian Records

(a version of this article was originally published in Acoustic Guitar Magazine 1997)

Sources not cited in the text are from record labels and personal conversations with musicians. Photo courtesy the Frank Driggs collection. Langston Hughes quote courtesy Vintage Books USA.

Visit Del Rey and Suzy Thompson for modern interpretations.

To buy Minnie’s original recordings check Document .

If you are interested in Minnie’s guitar style, I’ve made a Homespun video on how to figure her guitar parts in the various keys she plays in. There are also additional hints as to positions, and links to sound recordings on the Playing Memphis Minnie page. Have fun!

http://deeperrootsradio.com/blog/memphis-minnie-on-the-ice-box/

Memphis Minnie on the Ice Box

Langston Hughes is a favorite writer of mine, right along Lincoln Steffens, Peter Guralnick, Mark Twain, Bill Bryson…but I digress.

In 1942, the Chicago Defender published a review of a Memphis Minnie performance written by Hughes. It’s made its way around the horn many times and is, in my mind, priceless as it gives us the opportunity to witness a performance by Memphis Minnie without every seeing one. It’s a perfectly viable alternative to a YouTube video.

Memphis Minnie sits on top of the icebox at the 230 Club in Chicago and beats out blues on an electric guitar. A little dung-colored drummer who chews gum in tempo accompanies her, as the year’s end — 1942 — flickers to nothing, and goes out like a melted candle.

Midnight. The electric guitar is very loud, science having magnified all its softness away. Memphis Minnie sings through a microphone and her voice — hard and strong anyhow for a little woman’s — is made harder and stronger by scientific sound. The singing, the electric guitar, and the drums are so hard and so loud, amplified as they are by General Electric on top of the icebox, that sometimes the voice, the words, and melody get lost under sheer noise, leaving only the rhythm to come through clear. The rhythm fills the 230 Club with a deep and dusky heartbeat that overides all modern amplification. The rhythm is as old as Minnie’s most remote ancestor.

Memphis Minnie’s feet in her high-heeled shoes keep time to the music of her electric guitar. Her thin legs move like musical pistons. She is a slender, light-brown woman who looks like an old-maid school teacher, with a sly sense of humor. She wears glasses that fail to hide her bright bird-like eyes. She dresses neatly and sits straight in her chair perched on top of the refrigerator where the beer is kept. Before she plays she cocks her head on one side like a bird, glances from her place on the box to the crowded bar below, frowns quizzically, and looks more than ever like a colored lady teacher in a neat Southern school about to say, “Children, the lesson is on page 14 today, paragraph 2.” ….

But Memphis Minnie says nothing of the sort. Instead she grabs the microphone and yells, “Hey, now!” Then she hits a few deep chords at random, leans forward ever so slightly over her guitar, bows her head and begins to beat out a good old steady down-home rhythm on the strings — a rhythm so contagious that often it, makes the crowd holler out loud.

Then Minnie smiles. Her gold teeth flash for a split second. Her ear-rings tremble. Her left hand with dark red nails moves up and down the strings of the guitar’s neck. Her right hand with the dice ring on it picks out the tune, throbs out the rhythm, beats out the blues.

Then, through the smoke and racket of the noisy Chicago bar float Louisiana bayous, muddy old swamps, Mississippi dust and sun, cotton fields, lonesome roads, train whistles in the night, mosquitoes at dawn, and the Rural Free Delivery, that never brings the right letter. All these things cry through the strings on Memphis Minnie’s electric guitar, amplified to machine proportions — a musical version of electric welders plus a rolling mill.

Big rough old Delta Cities float in the smoke, too. Also border cities, Northern cities, Relief, W.P.A., Muscle Shoals, the jooks, “Has Anybody Seen My Pigmeat On The Line,” “See-See Rider,” St. Louis, Antoine Street, Willow Run, folks on the move who leave and don’t care. The hand with the dice-ring picks out music like this. Music with so much in it folks remember that sometimes it makes them holler out loud….

It was last year, 1941, that the war broke out, wasn’t it? Before that there wasn’t no defense work much. And the President hadn’t told the factory bosses that they had to hire colored. Before that it was W.P.A. and the Relief. It was 1939 and 1935 and 1932 and 1928 and the years that you don’t remember when your clothes got shabby and the insurance relapsed. Now, it’s 1942 — and different. Folks have jobs. Money’s circulating again. Relatives are in the Army with big insurances if they die.

Memphis Minnie, at year’s end, picks up those nuances and tunes them into the strings of her guitar, weaves them into runs and trills and deep steady chords that come through the amplifiers like the Negro heartbeats mixed with iron and steel. The way Memphis Minnie swings it sometimes makes folks snap their fingers, women get up and move their bodies, men holler, “Yes!” When they do, Minnie smiles.

But the men who run the place — they are not Negroes — never smile. They never snap their fingers, clap their hands, or move in time to the music. They just stand at the licker counter and ring up sales on the cash register. At this year’s end the sales are better than they used to be. But Memphis Minnie’s music is harder than the coins that roll across the counter. Does that mean that she understands? Or is it just science that makes the guitar strings so hard and so loud?

“Music at Year’s End”

by Langston Hughes

From The Chicago Defender

January 9, 1943

Reprinted in “Oxford American Magazine”

Spring, 2003

https://64parishes.org/entry/memphis-minnie

Memphis Minnie

Known as “Kid” all her life to her family and re-named “Memphis Minnie” by the recording industry, New Orleans native Lizzie Douglas was a prominent and pioneering guitarist, vocalist, songwriter, and blues recording artist.

Courtesy of The Nashville Bridge. Memphis Minnie with "Kansas Joe" McCoy.

New Orleans native Lizzie Douglas was a pioneering blues vocalist, guitarist, songwriter, and recording artist from the 1930s to the 1950s. She added a woman’s perspective to a music genre largely dominated by men and was also among the first blues musicians to experiment with the electrically amplified guitar. Known as “Kid” all her life to her family, she was given the moniker “Memphis Minnie” by the recording industry. Douglas honed her performing skills during the Jazz Age before coming into her own during the Great Depression. She continued to perform and record into the post-World War II era, but following her retirement in the mid-1950s, Douglas fell from widespread public notice, despite her more than 200 recordings. Her fall into obscurity ended when a roots music revival around the turn of the twenty-first century restored her as a much-admired icon of modern feminism and an inspiration to contemporary blues musicians.

Songs written by Douglas circulated widely in the mid-twentieth century, from “What’s the Matter with the Mill?”–an early hit for Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys–to “Bumble Bee,” which was remade as “I’m a King Bee” by Muddy Waters. Other songs surfaced in later decades, including Jefferson Airplane’s recording of “Me and My Chauffeur Blues” in the mid-1960s and Led Zeppelin’s revised version of “When the Levee Breaks,” recorded on the British rock band’s fourth album in 1971. With her late-century reinstatement in the pantheon of major blues figures, a new interest emerged in Douglas’s instrumental abilities, particularly the finesse and driving rhythms of her acoustic playing. These aspects of her artistry shine in a series of guitar duets with several male partners playing backup guitar. Douglas took an early interest in the electric guitar, which she adapted for popular Chicago blues ensembles. Arguably, she contributed to the developing sound of electric blues bands more than previously acknowledged and may have been the first blues musician to record with an electrically amplified guitar.

Early Life in New Orleans and Memphis

Lizzie Douglas was born on June 3, 1897, the eldest of thirteen children born to Abe and Gertrude Douglas, Baptist sharecroppers of African American heritage who had settled in the Algiers neighborhood of New Orleans. At the time Douglas was born, Algiers was a major industrial hub, with shipbuilding and repair yards, stockyards and slaughterhouses, and a sprawling rail yard that attracted hundreds of immigrant workers and their families, including those with German, Irish, Sicilian, and African American heritage.

To provide entertainment for these hard-working laborers and their families, Algiers boasted more than forty bars and dance halls. This vibrant environment produced a wealth of musical talent, including such well-known bandleaders and jazz musicians as Oscar “Papa” Celestine, “Kid” Thomas Valentine, and Henry “Red” Allen. Although the Douglas family relocated to Walls, Mississippi, roughly twenty miles southwest of Memphis, when Lizzie was seven, the musical ambience of her early childhood years made a strong impression on the headstrong, defiantly independent young girl. She asked for a guitar for her first Christmas away from New Orleans, and she often ran away from home, guitar in tow, to partake of the music scene around Beale Street in downtown Memphis. These frequent, short periods away took place even before Douglas reached adolescence. Before long, she left home for good, making a name for herself in the highly competitive music scene of Memphis while still a teenager.

Queen of Chicago Blues

Douglas began to travel with vaudeville and tent shows, including the Ringling Brothers Circus, where she learned showmanship. For several years, she partnered with the highly respected Delta-style guitarist Willie Brown, performing regularly for tourists on a scenic boat ride on a lake near Memphis. While Douglas worked on perfecting her own style, Brown complemented her by playing background rhythm and bass runs. Both experiences prepared Douglas for her life in music: although she collaborated with three different guitar-playing husbands, none outshone her own larger-than-life musical persona. By most accounts, Douglas’s stage presence stemmed from her admiration of vaudeville blues pioneer Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, particularly her self-confident spirit and stylishly exotic wardrobe.

After several years, Douglas moved back to the city to partner with Memphis Jug Band guitarist Casey Bill Weldon, who would become her first husband. She relentlessly promoted herself and her career, playing with jug bands, as a duo with her husband and others, and by herself in clubs and on street corners. She switched partners once again in 1929, marrying guitarist Joe McCoy, and soon after recorded for Columbia Records, which billed the duo as “Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe.” Their recordings sold well, which encouraged the couple to relocate to Chicago, then considered the blues capital. Her reputation preceded her, so that it was not long before the reigning “king” of Chicago blues, Lee Conley Bradley, better known as “Big Bill Broonzy,” challenged Douglas to a “cutting contest.” Legend tells that, while Douglas won the contest based on intensity of the audience applause, Broonzy nonetheless walked away with the bottle of whiskey, the contest’s formal award. More verifiable is the fact that Douglas established herself as the queen of Chicago blues, a status unchallenged through World War II, and that she and Broonzy remained close friends for the rest of their lives.

Memphis Minnie’s Legacy

Throughout the 1930s, Douglas recorded frequently and performed to great acclaim on both the Chicago blues scene and tours throughout the Midwest. By 1935, she parted ways with her second guitarist-husband. She signed on as a client of producer, music publisher, and entertainment promoter Lester Melrose, an association that provided a modicum of professional stability and placed her among his nationally known stars. On the other hand, Melrose focused on producing records geared toward commercial success, with sometimes formulaic results. His management contrasted with Douglas’s virtuosity and restless spirit, as demonstrated in her late 1920s experiments with the steel-bodied resonator guitars produced by the National Guitar Company. After leaving “Kansas Joe,” Douglas began performing with a full backup band that included piano, bass, and drums.

During the late 1930s and early 1940s, Douglas experimented with electrically amplified guitar. Unfortunately, her recordings during this time reflect a more conservative style, with restrained studio musicians, standard vocals by Douglas, and conventional solo guitar runs. These records do not bear witness to the true depth of her musicianship. As music journalist JoBeth Briton wrote in tribute, “Memphis Minnie was a phenomenal musician who [eventually] moved beyond intricate blues fingerpicking and phrasing to play ferocious stand-up electric guitar live on stage in Chicago at least one year before Muddy Waters. … Unfortunately, no vinyl exists to verify what she surely was: the foremother of electric, blues-based rock guitar.” Briton suggests that Melrose’s conservative approach left no room for her “hard-driving electric guitar.”

While the recorded output fails to give full testimony to Douglas’s musical prowess, written impressions offer a glimpse of Memphis Minnie in her prime. Harlem Renaissance writer and poet Langston Hughes published an account of her performance for a 1942 New Year’s Eve audience in The Chicago Defender newspaper:

The singing, the electric guitar, and the drums are so hard and so loud, amplified as they are by General Electric … that sometimes the voice, the words, and melody get lost under sheer noise, leaving only the rhythm to come through clear. … The rhythm is as old as Minnie’s most remote ancestor. … Then, through the smoke and racket of the noisy Chicago bar float Louisiana bayous, muddy old swamps, Mississippi dust and sun, cotton fields, lonesome roads, train whistles in the night, mosquitoes at dawn, and the Rural Free Delivery, that never brings the right letter. All these things cry through the strings on Memphis Minnie’s electric guitar, amplified to machine proportions—a musical version of electric welders plus a rolling mill.

Prior to the recording ban imposed from 1942 to 1944, when musicians’ unions struggled to gain royalties from record sales, Douglas established herself as a major figure, with 158 recorded releases between 1920 and 1942, almost as many as Bessie Smith’s 160. Douglas continued to record well into the mid-1950s, accompanied now by her third husband, guitarist Ernest “Little Son Joe” Lawlers, whom she married in 1939; the couple remained together for more than twenty years. By the late 1950s, Douglas’s health began to fail and, after playing with Little Son Joe in a 1958 tribute concert for Big Bill Broonzy, she headed back to her family in Memphis. There she assumed the role of a senior blues mentor, playing occasionally on the radio and encouraging young blues artists, just as she had done most of her life. Despite more than two hundred recorded tracks and the distinction of towering success for over two decades in the male-dominated, hardscrabble world of blues, Douglas lived the last years of her life in poverty and anonymity.

A Critical Reevaluation and Historical Reassessment Begins

In 1960, at sixty-three years old, Douglas suffered a debilitating stroke that confined her to a wheelchair. Douglas was too poor to afford a nursing home and was cared for by a sister, and by the time she died on August 6, 1973, her family could not even afford a headstone for her grave. Nevertheless, Douglas had left a legacy in both her music and her independent spirit. Readers of the British publication Blues Unlimited voted Douglas “Best Female Vocalist,” just ahead of Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey, in 1973, perhaps in acknowledgment of her death. Douglas was among the Blues Foundation and Blues Hall of Fame’s first twenty inductees when it was established in Memphis in 1980. Douglas was the only woman in the group besides Bessie Smith.

In 1996 blues singer and songwriter Bonnie Raitt had a headstone installed at Douglas’s grave at the Mt. Zion Baptist Church in Walls, Mississippi. An inscription reads, “The hundreds of sides Minnie recorded are the perfect material to teach us about the blues. For the blues are at once general, and particular, speaking for millions, but in a highly singular, individual voice. Listening to Minnie’s songs we hear her fantasies, her dreams, her desires, but we will hear them as if they were our own.”

In 2012 folk, blues, and jazz vocalist and record producer Maria Muldaur put together First Came Memphis Minnie,

a collection of Memphis Minnie’s best-known songs performed by female

blues artists such as Raitt, Ruthie Foster, Rory Block, Phoebe Snow, and

Koko Taylor.

Author

Suggested Reading:

Garon, Paul, and Beth Garon. Woman with Guitar: Memphis Minnie’s Blues. New York: Da Capo, 1992.

Rey, Del. “Guitar Queen: The Groundbreaking Blues of Memphis Minnie, from Delta Styles to the Chicago Sound.” Acoustic Guitar Magazine, no. 33 (September 1995).

https://www.musicianguide.com/biographies/1608002338/Memphis-Minnie.html

Memphis Minnie Biography

Born Lizzie Douglas on June 3, 1897, in Algiers, LA ( died August 6, 1973); married: Will Weldon (a.k.a. Casey Bill), circa 1920s; Joe McCoy, 1929-1934; Earnest Lawlars (a.k.a. Little Son Joe), 1939.

For nearly three decades, Memphis Minnie was one of the most influential blues artists in the United States. From the early 1920s until she retired in the mid-1950s, she released more than 180 songs, in addition to those released after her death in 1973. Minnie's songwriting and performances thrived in a genre dominated by men. Unlike most female blues singers of the time, Minnie also wrote her own songs and played guitar. She cemented her place in blues history with such classics as "Bumble Bee," "Hoodoo Lady," and "I Want Something for You." Her repertoire included country blues, urban blues, the Melrose sound, Chicago blues, and postwar blues.

Born Lizzie Douglas in Algiers, Louisiana, Memphis Minnie was the eldest of Abe and Gertrude Wells Douglas' 13 children. Throughout her childhood, her family always called her "Kid." When she was seven years old, the Douglas family moved to Wall, Mississippi, just south of Memphis. The following year, she received her first guitar for Christmas. She learned to play both the guitar and banjo and performed under the name Kid Douglas.

In 1910, at the age of 13, she ran away from home to live on Beale Street in Memphis, Tennessee. Throughout her teenage years, she would periodically return to her family's farm when she ran out of money. The majority of the time, she played and sang on street corners. Her sidewalk performances eventually led to a tour of the South with the Ringling Brothers Circus.

Still performing under the name Kid Douglas, she returned to Memphis and became embroiled in the Beale Street blues scene. At the time, women were highly valued-along with whiskey and cocaine-and Beale Street was one of the first places in the country where women could perform in public. In order to survive financially, most of the female performers on Beale Street were also prostitutes, and Minnie was no exception. She received $12 for her services-an outrageous fee for the time.

Beyond the buzz she created as a performer, she also developed a reputation as a woman who could take care of herself. "Any men fool with her, she'd go for them right away," blues guitarist/vocalist Johnny Shines told Paul and Beth Garon in Woman With Guitar. "She didn't take no foolishness off them. Guitar, pocket-knife, pistol, anything she got her hands on, she'd use it; y'know Memphis Minnie used to be a hell-cat."

During the 1920s, she reportedly married Will Weldon, also known as Casey Bill. However, some historians claim the two didn't meet until their first recording sessions together in 1935 and never married. If she did marry Weldon, she had left him within the decade, and married guitarist Kansas Joe McCoy in 1929. Minnie and McCoy often performed together and were discovered by a talent scout from Columbia Records that same year. They went to New York City for their first recording sessions, and it was then that she changed her name to Memphis Minnie.

McCoy and Minnie released the single "When the Levee Breaks" backed with "That Will Be Alright," but McCoy performed all the vocals. Two months later, they released "Frisco Town" and "Going Back to Texas." Minnie sang alone on "Frisco Town" and sang a duet with McCoy on "Going Back to Texas."

In 1930, Minnie released one of her favorite songs "Bumble Bee," which led to a recording contract with the Vocalion label. Later that year, she and McCoy released "I'm Talking About You" on Vocalion. The couple continued to produce records for Vocalion for two more years, then left the label and decided to move to Chicago. It didn't take long before Minnie and McCoy had become a part of the city's blues scene, and they had introduced country blues into an urban environment.

Divorce Expanded Musical Horizons

McCoy and Minnie recorded songs together and on their own for Decca Records until they divorced in 1934. According to several reports, McCoy's increasing jealousy of Minnie's fame and success caused the breakup. The two-part single "You Got To Move (You Ain't Got To Move)" was the last record issued by the couple.

Back on her own, Minnie began to experiment with different styles and sounds. She recorded four sides for the Bluebird label in 1935 under the name Texas Tessie. They included "Good Mornin'," "You Wrecked My Happy Home," "I'm Waiting on You," and "Keep on Goin'." In August of that year, she returned to the Vocalion label to record two songs in tribute to boxing champion Joe Louis: "He's in the Ring (Doing That Same Old Thing" and "Joe Louis Strut." Columbia later released "He's in the Ring" on the collection The Great Depression: American Music in the '30s in 1994.

In October of 1935, Minnie recorded with Casey Bill Weldon for the first time on "When the Sun Goes Down, Part 2" and Hustlin' Woman Blues." It was about this time that Minnie had teamed up with manager Lester Melrose, the single most powerful and influential executive in the blues industry during the 1930s and 1940s. By the end of the 1930s, Minnie had recorded nearly 20 sides for Decca Records and eight sides for the Bluebird label. In 1939, she returned to the Vocalion label. She had also met and married her new musical partner, guitarist Earnest Lawlars, also known as Little Son Joe.

Minnie and Little Son Joe also began to release material on Okeh Records in the 1940s. Their earliest recordings together included "Nothin' in Ramblin'" and "Me and My Chauffeur Blues." The couple continued to record together throughout the decade. In 1952, Minnie recorded a session for the legendary Chess label, when it was just two months old. Singles from the session included "Broken Heart" and a re-recording of "Me and My Chauffeur Blues." The following year, she released her last commercial recording after 24 years in blues music, "Kissing in the Dark" and "World of Trouble" on the JOB label.

Within the next few years, Minnie's health began to fail. She retired from her music career and returned to Memphis. She performed one last time at a memorial for her friend, blues artist Big Bill Broozny in 1958. Periodically, she would appear on Memphis radio stations to encourage younger blues musicians. As the Garons wrote in Woman with Guitar, "She never laid her guitar down, until she could literally no longer pick it up." In 1960, Minnie suffered from a stroke and was bound to a wheelchair. The following year, Little Son Joe passed away. The trauma provoked Minnie to have a second stroke.

Illness Forced Retirement

By the mid-1960s Minnie had entered the Jell Nursing Home and she could no longer survive on her social security income. The news of her plight began to spread, and magazines such as Living Bluesand Blues Unlimited appealed to their readers for assistance. Many fans quickly sent money for her care, and several musicians held benefits to help her. On August 6, 1973, Memphis Minnie died of a stroke in the nursing home. In true blues fashion, she was buried in an unmarked grave at the New Hope Cemetery in Memphis.

In 1980, Memphis Minnie was one of the first 20 artists inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame. Her work was featured on several blues compilations throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Compilations of her own work also continued to surface, including I Ain't No Bad Girl in 1989 and Queen of the Blues in 1997.

by Sonya Shelton

Memphis Minnie's Career

Began performing on the streets of Memphis, Tennessee, 1910; signed recording contract with Columbia Records, 1929; released more than 180 songs on various labels until her retirement in 1953, including Columbia Records, Vocalion, Decca, Bluebird, Okeh, and Checker.

Famous Works

- Selected discography

- Singles

- "When the Levee Breaks"/"That Will Be Alright," Columbia, 1929.

- "Frisco Town"/"Going Back to Texas," Columbia, 1929.

- "Bumble Bee," Columbia, 1930.

- "Stinging Snake Blues," Vocalion, 1934.

- "You Got to Move (You Ain't Got to Move)," Decca Records, 1934.

- "He's in the Ring (Doing That Same Old Thing)," Vocalion, 1935.

- "Joe Louis Strut," Vocalion, 1935.

- "When the Sun Goes Down, Part 2," Bluebird, 1935.

- "Hustlin' Woman Blues," Bluebird, 1935.

- "Me and My Chauffeur Blues," Okeh Records, 1941; re-released, Chess Records, 1952.

- "In My Girlish Days," Okeh Records, 1941.

- "Looking the World Over," Okeh Records, 1941.

- "Broken Heart," Chess Records, 1952.

- "Kissing in the Dark"/"World of Trouble," JOB, 1953.

- Albums

- I Ain't No Bad Girl , Portrait/CBS Records, 1989.

- Queen of the Blues , Sony Music, 1997.

Further Reading

Sources

- Garon, Paul and Beth, Woman with Guitar: Memphis Minnie's Blues , Da Capo Press, New York, 1992.

- American Heritage , September 1994.

- Down Beat , May 1995; March 1998.

- High Fidelity , April 1989.

- http://www.blueflamecare.com/Memphis_Minnie.html (September 23, 1998).

- http://www.memphisguide.com/music2/blues/bluesartists/minnie.html (September 23, 1998).

Lizzie "Kid" Douglas, "Memphis Minnie"

Born June 3, 1897, in Algiers, Louisiana, Lizzie Douglas was raised

on a farm before moving in 1904 to Walls in northern Mississippi. The

following year Douglas was given a guitar for her birthday and quickly

learned to play. A child prodigy, she began playing local parties as

"Kid" Douglas before running away from home to play for tips at Church's

Park ( the current W.C. Handy Park) on Beale Street in Memphis. During

the 1910s and early 1920s, Douglas adopted the handle of Memphis Minnie

and toured the South, playing tent shows with the Ringling Brothers

Circus.

During the late 1920s Minnie began playing guitar with a variety of ad hoc jug bands during Memphis's jug band craze. Minnie also began a common law marriage with Kansas Joe McCoy, a musician with whom she had begun playing and would soon record. Their very first session yielded the hit song "Bumble Bee" (later recorded by Muddy Waters as "Honey Bee"), and McCoy would be her musical partner for the next six years. Within a year of her first recording date, Minnie had logged a half-dozen more sessions, including a reprise of "Bumble Bee" with the Memphis Jug Band. Bukka White claimed that Minnie sang backup on his 1930 gospel recordings. By the time the effects of the Great Depression had shackled the recording industry, Minnie had recorded fifty sides that showcased her powerful voice and energetic guitar picking. She affected wealth as her idol Ma Rainey had done, traveling to shows in luxury cars and wearing bracelets made of silver dollars on her wrists.

During the 1930s, Minnie moved to Chicago where she set the musical

style by taking up bass and drum accompaniment, anticipating the sound

of the 1950s Chicago blues. After her breakup with Kansas Joe, Minnie

married Ernest Lawlars, known as "Little Son Joe," and continued to

record into the early 1950s. Poor health prompted her to return to

Memphis and forsake the musician's life in 1958. Memphis Minnie was the

greatest female country blues singer, and the popularity of her songs

made her one of the blues most influential artists.

Memphis Minnie died August 6, 1973, in Memphis, Tennessee, and is buried in New Hope Cemetery in Walls, Mississippi.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Me_and_My_Chauffeur_Blues#References

Me and My Chauffeur Blues

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Me and My Chauffeur Blues"

"Me and My Chauffeur Blues" is a song written and recorded by blues singer and guitarist Memphis Minnie in 1941.[1] It was added to the U.S. National Recording Registry in 2019. A number of other musicians have recorded the song, or adaptations of it, often under shortened titles.

Memphis Minnie's song

Memphis Minnie recorded "Me and My Chauffeur Blues" in Chicago on May 21, 1941, for Okeh Records, with her husband Ernest "Little Son Joe" Lawlars on additional guitar. She used the tune of "Good Morning, School Girl", recorded by John Lee "Sonny Boy" Williamson in 1937.[2] The 78 rpm record listed "Lawlar" as the songwriter,[3] but it is thought Minnie wrote the song herself.[4] Performing rights organizations show both Minnie and Ernest Lawler [sic] as the writers.[5][6] The song was selected by the Library of Congress in 2019 for preservation in the National Recording Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[7]

Adaptations by other musicians

Big Mama Thornton recorded a version of the song as "Me and My Chauffeur" backed by guitarist Johnny Talbot and his band in Berkeley, California, in March 1964 for producer James C. Moore. It was released that year as a single with "Before Day", the only record ever issued on Moore's Sharp label. Moore leased the two tracks to the Bihari brothers, who issued them on a Kent Records single in 1965.[8] Thornton also recorded it with backing by Mississippi Fred McDowell on slide guitar in the recording session for the Big Mama Thornton – In Europe album in London on October 20, 1965.[9] The track was omitted from the original album, but added as a bonus track titled "Chauffeur Blues" on the 2005 CD reissue.[10]

Nina Simone first heard the piece sung by Thornton. Andy Stroud, Simone's husband and manager, adapted it for her and she recorded it as "Chauffeur" on her Let It All Out album, released in February 1966.[11]

Jefferson Airplane recorded a version as "Chauffeur Blues" on the album Jefferson Airplane Takes Off, released in August 1966, with Signe Anderson as the lead vocalist. The album lists Lester Melrose, the influential early blues record producer, as the songwriter. It is performed at a faster tempo than Minnie's version and uses only three of her four verses. Anderson performed the song with strong contralto vocals. According to Jeff Tamarkin, author of Got a Revolution! The Turbulent Flight of Jefferson Airplane, Jorma Kaukonen brought in "Chauffeur Blues" for Signe to sing.[12] It was not included in the repertoire of Jefferson Airplane's early gigs and was performed only occasionally. It was last performed by the Airplane on October 15, 1966, at the concert recorded as Signe's Last. An extended version of the song is included in the remastered version of Jefferson Airplane Takes Off. The blues writer and historian Thomas Millroth claims Memphis Minnie received no royalties from Jefferson Airplane.[13]

Versions of the song have been recorded by a number of other artists.

Died: August 6, 1973, Memphis, TN

From Memphis Hall of Fame:

Memphis Minnie: Keep On Goin’ 1930–1953

A revealing wide-angle snapshot of one of the great blueswomen.

Our experienced team has worked for some of the biggest brands in music. From testing headphones to reviewing albums, our experts aim to create reviews you can trust. Find out more about how we review.

When Memphis Minnie made her first recordings, in 1929, she was 32 – a contemporary of Tommy Johnson, a few years older than Son House and Skip James. More than 20 years later, when all those men were forgotten, she was still drawing an audience in clubs, still making records. Her professional career in blues is matched by no other female musician, and by very few men.

How she managed that is clear from this compilation, from the intricate guitar duets of the early 30s with her then-husband Kansas Joe McCoy through the small-band sides of the later 30s, the plugged-in 1941 recordings with her next husband Ernest ‘Little Son Joe’ Lawlars such as her hit Me And My Chauffeur Blues, and the still-punchy music she made in the 50s like Kissing In The Dark and Broken Heart. What Minnie had was adaptability. Like Big Bill Broonzy, she heard how the sounds and themes of the blues were changing with the times and she kept pace with them.

Listen to the shift from the gentle rural rhythms of her first success, Bumble Bee from 1930 to the biting guitar line and vituperative lyrics of Killer Diller Blues from 1946, or the party harmonising on the following year’s Shout The Boogie. Johnson, House and James were greats, but this kind of musical re-invention would have been beyond them.

She did have excellent help. Kansas Joe and Little Son Joe were adept guitarists, and she could draw on pianists like Blind John Davis or Black Bob. But she could carry a song perfectly well by herself, as numbers like Chickasaw Train Blues or Butcher Man Blues demonstrate with their easy-swinging guitar lines. And always there’s that confident, sexy voice, the sound of a tough cookie with a velvet tongue, heard to particularly moving effect in her tribute to an earlier blueswoman, Ma Rainey, and a song that may be autobiographical, In My Girlish Days.

Memphis Minnie – The Best Thing Goin’ In The Woman Line

Memphis Minnie’s legacy is not just that she recorded across four decades, she was practically the lone female voice in the increasingly male dominated 1930’s urban Blues scene

| |

| Play This Week’s Top Tracks on Amazon Music Unlimited (ad) | |

Whether or not Will or Casey Bill Weldon are one in the same person has been the subject of much debate by blues historians down the years. What’s also open to debate is which one of them was ever married to Memphis Minnie is also open to conjecture. What is irrefutable is the fact that Casey Bill recorded with Minnie. On the same day as the bluesman cut his first Bluebird sides in October 1935 he backed Minnie on four numbers.

Memphis Minnie’s legacy is not just that she recorded across four decades, she was practically the lone female voice in the increasingly male dominated 1930’s urban Blues scene. The blues since the early days of the great vaudeville blues women, Ma Rainey, Bessie and Mamie Smith, had largely become the preserve men… but the woman born Lizzie douglas in Algiers, Louisiana in 1897 gave them a serious run for their money.

Her style was rooted on the country but flowered in the vibrant pre war Chicago music scene, which is where she recorded the majority of over one hundred pre-war releases. She worked with a whole host of excellent blues performers, which bears testament to her talent, she is even supposed to have beaten Big Bill Broonzy in a musical cutting contest. Among those that recorded with her were, Joe McCoy her husband from the late 1920’s, the Jed Devenport Jug Band, Georgia Tom, Tampa Red, Black Bob, Blind John Davis and Little Son Joe. She also sat in with Little Son, Bumble Bee Slim and the Memphis Jug Band. She also worked live with Big Bill Broonzy, Sunnyland Slim and Roosevelt Sykes. By 1935 Minnie and Joe McCoy had split up, and Minnie married Little Son Joe in the late 30s.

Minnie was an early convert to the electric guitar which she used to good effect in her biggest hit, ‘Me and My Chauffeur Blues’, recorded in 1941 with Little Son. The song, which used the same tune as ‘Good Morning Little Schoolgirl’, became influential to many that heard it. Koko Taylor said, “it was the first Blues record I ever heard.” Lightnin’ Hopkins even ‘answered’ Minnie with his 1960 song, Automobile Blues. Chuck Berry based his ‘I Want to be Your Driver on the Chauffeur’, while Jefferson Airplane adapted it as ‘Chauffeur Blues’ on their 1966 debut album. Unfortunately Jefferson Airplane neglected to acknowledge Minnie’s recording and failed to pay any royalties as a result.

The longevity of Minnie’s career meant that her records cover a wide range of subject matter. Many of her songs, like ‘Bumble Bee’, ‘Dirty Mother For You’ and ‘Butcher Man’, were openly sexual, all delivered in her confident, sassy way. Others like ‘Ma Rainey’ and ‘He’s in the Ring (Doing That Same Old Thing)’ were about celebrities. ‘Ma Rainey’ was recorded just 6 months after the vaudeville blues singer’s death, while the other was a 1935 tribute to the boxer Joe Louis. In her songs Minnie also tackled crime, voodoo, trains, health and the perennial subject of chickens! Minnie was constantly touring, playing jukes and fish fries, which certainly helped in maintaining her popularity. She stayed in touch with her audience, singing about what they both knew, and understood.

The lady who was at the forefront of transforming the blues into ‘Pop Music’ continued to record up until 1954. By then her health was failing, after she and Little Son Joe retired to live in Memphis. Little Son died in 1961 and soon after the woman who was remembered by many of her musical contemporaries from Chicago as “a hard drinking women” had a stroke.

Jo Ann Kelly the British Blues singer who recorded in the late 1960s and 70s always claimed Memphis Minnie as an inspiration. She and her brother raised money for Minnie at a Blues club benefit and arranged for a Memphian Blues fan deliver it to her in the nursing home.

Her sister looked after her for a while and then she moved into a nursing home. Despite her huge popularity and considerable record sales Minnie had little or no money, but after various magazines printed appeals fans began sending her donations. Minnie, who Bukka White described as “the best thing goin’ in the woman line”, died on 6 August 1973.

Listen to the Memphis Minnie Vol. 5 collection on Apple Music and Spotify to hear her complete works from 1940-1941.

When The Levee Breaks:

Memphis Minnie - Early Rhythm & Blues 1949:

Tracklist:

0:00 Memphis Minnie - Down Home Girl

2:44 Memphis Minnie - Night Watchman Blues (take 1)

5:59 Memphis Minnie - Night Watchman Blues (take 2)

8:36 Memphis Minnie - Why Did I Make You Cry

11:19 Memphis Minnie - Kid Man Blues

13:52 Jimmy Rogers - Ludella

15:49 St. Louis Jimmy - Hard Work Boogie

18:41 St. Louis Jimmy - Your Evil Ways

21:35 St. Louis Jimmy - I Sit Up All Night

24:30 St. Louis Jimmy - State Street Blues

27:07 Sunnyland Slim - When I Was Young

29:33 Little Brother Montgomery - Vicksburg Blues

32:45 Little Brother Montgomery - A & B Blues

35:41 Little Brother Montgomery - After Hour Blues

38:24 Pee Wee Hughes - Sugar Mama Blues

40:52 Pee Wee Hughes

Shreveport Blue Credits

Tracks 1 to 5:

Vocals and guitar --Memphis Minnie

Piano - Sunnyland Slim

Bass and drums - unknown

Tracks 6-16:

Vocals and guitar - Jimmy Rogers

Guitar - Muddy Waters (not confirmed)

Bass - Big Crawford

Harmonica - Little Walter

Piano- Johnny Jones (not confirmed)

Tracks 7 to 10

Vocals - St. Louis Jimmy

Guitar - Jimmy Rogers (not confirmed)

Piano - Roosevelt Sykes (not confirmed)

Bass and drums - unknown

Track 11

Vocals and piano - Sunnyland Slim

Tenor saxophone, guitar, bass and drums - unknown

Tracks 12 to 14

Piano - Little Brother Montgomery

Tracks 15 and 16

Vocals, guitar and harmonica - Pee Wee Hughes

Drums - unknown

Label: Biograph - BCD 124

Year: 1992

https://travsd.wordpress.com/2015/06/03/memphis-minnie-straddling-the-blues/

(Travalanche)

The observations of actor, author, comedian, critic, director, humorist, journalist, m.c., performance artist, playwright, producer, publicist, public speaker, songwriter, and variety booker Trav S.D.

Memphis Minnie: Straddling the Blues

Today is the birthday of Memphis Minnie (Lizzie “Kid” Douglas a.k.a. Minnie Lawlers, 1897-1973).

To me, she is one of the most incredible figures in blues history, on account of she straddles so many different KINDS of blues (yes, I pretty much meant that verb). Her recording career started in 1929. What is interesting to me is that she entered the field when it was dominated by female singers (Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, Mamie Smith) and some of her records have that classic blues orchestration (largely piano driven). BUT (here’s where she’s almost entirely unique) she’s even better known for playing the rural style of Delta country blues; she didn’t just sing but she played guitar, and that was a field entirely dominated by men (guys like Robert Johnson, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Son House etc etc). Furthermore, her career went long enough that she also entered the era of amplification and, the more urban big city Chicago blues of the sort we associate with Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf etc etc that eventually led to rock ‘n’ roll). She is a bridge to everywhere.

Memphis Minnie grew up in Mississippi and Louisiana, started playing the banjo at age 10, and ran off to play guitar of Beale Street sidewalks in Memphis by age 13. (She also turned tricks to support herself — and her rough lifestyle shows up in her songs, whoo boy, did she record some dirty and rough and funny songs). She is also said to have toured for four years with Ringling Brothers Circus (1916-1920) as a musician.

To give you an idea of the many sounds and eras she spanned…

“Bumble Bee”, 1930 (country blues):

“Down in the Alley”, 1937 (classic blues):

“Night Watchman Blues”, 1949 (Chicago blues):

http://memphismusichalloffame.com/inductee/memphisminnie/

Vocalion Promotional Photo. Courtesy Photo Archive, Delta Haze Corporation. Background: DSC03454 by jeremy1choo, Some rights reserved

But there were plenty of men who wanted to play guitar like Memphis Minnie. She once even beat the great Big Bill Broonzy in a picking contest. Her title “Queen of the Country Blues” was no hype. Minnie did everything the boys could do, and she did it in a fancy gown with full hair and makeup. She had it all: stellar guitar chops, a powerful voice, a huge repertoire including many original, signature songs and a stage presence simultaneously glamorous, bawdy and tough.

She transcended both gender and genre. Her recording career reached from the 1920s heyday of country blues to cutting electric sides in 1950s Chicago studios for the Chess subsidiary Checker. Minnie helped form the roots of electric Chicago blues, as well as R&B and rock ‘n’ roll, long before she plugged in. Her unique storytelling style of songwriting drew such surprising fans as Country Music Hall of Famer Bob Wills, the King of Western Swing, who covered her song about a favorite horse, “Frankie Jean,” right down to copying Minnie’s whistling. Though she inspired as many men as women, her influence was particularly strong on female musicians, her disciples including her niece Lavern Baker, a rock and R&B pioneer in her own right, as well as Maria Muldaur (who released a 2012 tribute CD) Bonnie Raitt (who paid for her headstone), Rory Block, Tracy Nelson, Saffire and virtually every other guitar-slinging woman since.

A Tough Kid

She sang about being “born in Louisiana, raised in Algiers” (a town just across from New Orleans), but that was poetic license. She was actually born in Mississippi, raised in Walls, a small farming community in DeSoto County south of Memphis, according to US Census data uncovered by Dr. Bill Ellis. She learned music early on, getting a guitar for Christmas at the age of 8. She was a wild child, running away from home for the last time at 13, heading for the bright lights of Beale Street, where, as “Kid” Douglas, she quickly made a name for herself with the jug bands and string groups that played on the street and at Memphis’ Church Park. Life was hard for a homeless kid and she grew up fast, earning a reputation for toughness, both personally and musically.

In the early 1920s, the most popular blues performers were Bessie Smith and the other classic blues singers - bejeweled women standing in front of jazz bands singing Tin Pan Alley blues. By contrast, Minnie’s style was far more raw and personal, and it endured long after that first blues craze.

She described her life in “In My Girlish Days” & “Nothing in Rambling” sang about a favorite cafe in “North Memphis Blues” documented local events in “Garage Fire Blues” and paid tribute to the great African-American boxer Joe Louis in “The Joe Louis Strut.”

Bumble Bee Blues

She recorded her most popular song, “Bumble Bee Blues,” at her first session in 1929 and re-recorded the song repeatedly throughout her career, including a session with The Memphis Jug Band. That version, with its laid-back, behind-the-beat, jug-driven groove, points the way to the Memphis Beat later perfected at Stax Records.

Soo Cow Soo

Her guitar playing was just as visionary; her

up-the-neck solo on 1931’s “Soo Cow Soo” foreshadowing the rockabilly

revolution to come. On record, her second guitarist was usually one of

her guitar-playing husbands, first “Kansas Joe” McCoy, and then Ernest

“Little Son Joe” Lawlers.

https://www.bluesblastmagazine.com/woman-with-guitar-memphis-minnies-blues-book-review/

Woman With Guitar – Memphis Minnie’s Blues Book Review

Woman With Guitar – Memphis Minnie Blues

by Paul & Beth Garon

City Lights Books

407 pages