AS OF JANUARY 13, 2023 FIVE HUNDRED MUSICAL ARTISTS HAVE BEEN FEATURED IN THE SOUND PROJECTIONS MAGAZINE THAT BEGAN ITS ONLINE PUBLICATION ON NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2015/09/john-coltrane-1926-1967-legendary.html

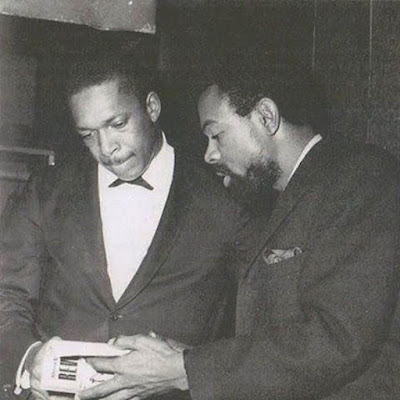

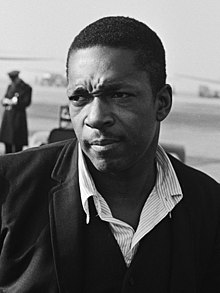

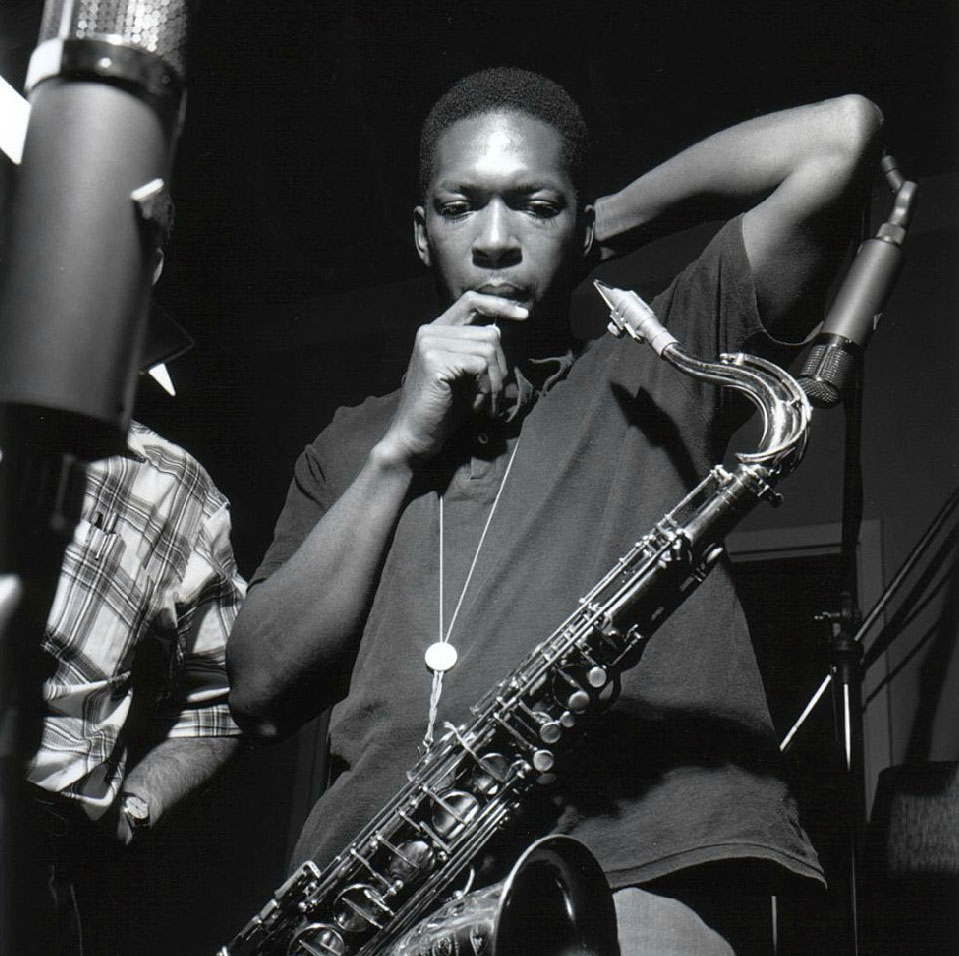

PHOTO: JOHN COLTRANE (1926-1967)

A titan of the 20th century, the saxophonist pioneered many of the jazz revolutions of the post-hard bop era

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/john-coltrane-mn0000175553#biography

John Coltrane

(1926-1967)

Biography

by William Ruhlmann

A towering musical figure of the 20th century, saxophonist John Coltrane reset the parameters of jazz during his decade as a leader. At the outset, he was a vigorous practitioner of hard bop, gaining prominence as a sideman for Miles Davis before setting out as a leader in 1957, when he released Coltrane on Prestige and Blue Train on Blue Note. Coltrane quickly expanded his horizons, pioneering a technique critic Ira Gitler dubbed "sheets of sound," consisting of the saxophonist playing a flurry of notes on his tenor within the confines of a few chords. During his last days with Davis, along with his earliest records for Atlantic, Coltrane leaned into this technique, but as he developed his career as a leader in the early '60s, he also turned lyrical. His sweet, fluid soprano sax distinguished My Favorite Things, which helped turn the album into a standard upon its release in 1961, but Coltrane soon backed away from mainstream acceptance. Working with pianist McCoy Tyner, drummer Elvin Jones, and bassist Jimmy Garrison -- a band that would be labeled the "Classic Quartet" -- Coltrane entered a fearless exploratory phase, explicitly incorporating his spiritual quest into his experimental music. A Love Supreme, an album released on Impulse! in 1965, marked the popular height of this period, but Coltrane continued to voyage to the outer edges of jazz in his final years, collaborating with Archie Shepp and Pharoah Sanders. Liver cancer ended his life prematurely: he died at the age of 40 in 1967, just ten years after his first LP as a leader -- but Coltrane's legacy was so varied and rich, he remained the touchstone for creativity in jazz for decades after his passing.

Coltrane was the son of John R. Coltrane, a tailor and amateur musician, and Alice (Blair) Coltrane. Two months after his birth, his maternal grandfather, the Reverend William Blair, was promoted to presiding elder in the A.M.E. Zion Church and moved his family, including his infant grandson, to High Point, North Carolina, where Coltrane grew up. Shortly after he graduated from grammar school in 1939, his father, his grandparents, and his uncle died, leaving him to be raised in a family consisting of his mother, his aunt, and his cousin. His mother worked as a domestic to support the family. The same year, he joined a community band in which he played clarinet and E flat alto horn; he took up the alto saxophone in his high school band. During World War II, Coltrane's mother, aunt, and cousin moved north to New Jersey to seek work, leaving him with family friends; in 1943, when he graduated from high school, he too headed north, settling in Philadelphia. Eventually, the family was reunited there.

While taking jobs outside music, Coltrane briefly attended the Ornstein School of Music and studied at Granoff Studios. He also began playing in local clubs. In 1945, he was drafted into the navy and stationed in Hawaii. He never saw combat, but he continued to play music and, in fact, made his first recording with a quartet of other sailors on July 13, 1946. A performance of Tadd Dameron's "Hot House," it was released in 1993 on the Rhino Records anthology The Last Giant. Coltrane was discharged in the summer of 1946 and returned to Philadelphia. That fall, he began playing in the Joe Webb Band. In early 1947, he switched to the King Kolax Band. During the year, he switched from alto to tenor saxophone. One account claims that this was as the result of encountering alto saxophonist Charlie Parker and feeling the better-known musician had exhausted the possibilities on the instrument; another says that the switch occurred simply because Coltrane next joined a band led by Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson, who was an alto player, forcing Coltrane to play tenor. He moved on to Jimmy Heath's group in mid-1948, staying with the band, which evolved into the Howard McGhee All Stars until early 1949, when he returned to Philadelphia. That fall, he joined a big band led by Dizzy Gillespie, remaining until the spring of 1951, by which time the band had been trimmed to a septet. On March 1, 1951, he took his first solo on record during a performance of "We Love to Boogie" with Gillespie.

At some point during this period, Coltrane became a heroin addict, which made him more difficult to employ. He played with various bands, mostly around Philadelphia, during the early '50s, his next important job coming in the spring of 1954, when Johnny Hodges, temporarily out of the Duke Ellington band, hired him. But he was fired because of his addiction in September 1954. He returned to Philadelphia, where he was playing when he was hired by Miles Davis a year later. His association with Davis was the big break that finally established him as an important jazz musician. Davis, a former drug addict himself, had kicked his habit and gained recognition at the Newport Jazz Festival in July 1955, resulting in a contract with Columbia Records and the opportunity to organize a permanent band, which, in addition to him and Coltrane, consisted of pianist Red Garland, bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer "Philly" Joe Jones. This unit immediately began to record extensively, not only because of the Columbia contract, but also because Davis had signed with the major label before fulfilling a deal with jazz independent Prestige Records that still had five albums to run. The trumpeter's Columbia debut, 'Round About Midnight, which he immediately commenced recording, did not appear until March 1957. The first fruits of his association with Coltrane came in April 1956 with the release of The New Miles Davis Quintet (aka Miles), recorded for Prestige on November 16, 1955. During 1956, in addition to his recordings for Columbia, Davis held two marathon sessions for Prestige to fulfill his obligation to the label, which released the material over a period of time under the titles Cookin' (1957), Relaxin' (1957), Workin' (1958), and Steamin' (1961).

Coltrane's association with Davis inaugurated a period when he began to frequently record as a sideman. Davis may have been trying to end his association with Prestige, but Coltrane began appearing on many of the label's sessions. After he became better known in the '60s, Prestige and other labels began to repackage this work under his name, as if he had been the leader, a process that has continued to the present day. (Prestige was acquired by Fantasy Records in 1972, and many of the recordings in which Coltrane participated have been reissued on Fantasy's Original Jazz Classics [OJC] imprint.)

Coltrane tried and failed to kick heroin in the summer of 1956, and in October, Davis fired him, though the trumpeter had relented and taken him back by the end of November. Early in 1957, Coltrane formally signed with Prestige as a solo artist, though he remained in the Davis band and also continued to record as a sideman for other labels. In April, Davis fired him again. This may have given him the impetus to finally kick his drug habit, and freed of the necessity of playing gigs with Davis, he began to record even more frequently. On May 31, 1957, he finally made his recording debut as a leader, putting together a pickup band consisting of trumpeter Johnny Splawn, baritone saxophonist Sahib Shihab, pianists Mal Waldron and Red Garland (on different tracks), bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer Al "Tootie" Heath. They cut an album Prestige simply titled Coltrane upon release in September 1957. (It has since been reissued under the title First Trane.)

In June 1957, Coltrane joined the Thelonious Monk Quartet, consisting of Monk on piano, Wilbur Ware on bass, and Shadow Wilson on drums. During this period, he developed a technique of playing several notes at once, and his solos began to go on longer. In August, he recorded material belatedly released on the Prestige albums Lush Life (1960) and The Last Trane (1965), as well as the material for John Coltrane with the Red Garland Trio, released later in the year. (It was later reissued under the title Traneing In.) But Coltrane's second album to be recorded and released contemporaneously under his name alone was cut in September for Blue Note Records. This was Blue Train, featuring trumpeter Lee Morgan, trombonist Curtis Fuller, pianist Kenny Drew, and the Miles Davis rhythm section of Chambers and "Philly" Joe Jones; it was released in December 1957. That month, Coltrane rejoined Davis, playing in what was now a sextet that also featured Cannonball Adderley. In January 1958, he led a recording session for Prestige that produced tracks later released on Lush Life, The Last Trane, and The Believer (1964). In February and March, he recorded Davis' album Milestones, released later in 1958. In between the sessions, he cut his third album to be released under his name alone, Soultrane, issued in September by Prestige. Also in March 1958, he cut tracks as a leader that would be released later on the Prestige collection Settin' the Pace (1961). In May, he again recorded for Prestige as a leader, though the results would not be heard until the release of Black Pearls in 1964.

Coltrane appeared as part of the Miles Davis group at the Newport Jazz Festival in July 1958. The band's set was recorded and released in 1964 on an LP also featuring a performance by Thelonious Monk as Miles & Monk at Newport. In 1988, Columbia reissued the material on an album called Miles & Coltrane. The performance inspired a review in Down Beat, the leading jazz magazine, that was an early indication of the differing opinions on Coltrane that would be expressed throughout the rest of his career and long after his death. The review referred to his "angry tenor," which, it said, hampered the solidarity of the Davis band. The review led directly to an article published in the magazine on October 16, 1958, in which critic Ira Gitler defended the saxophonist and coined the much-repeated phrase "sheets of sound" to describe his playing.

Coltrane's next Prestige session as a leader occurred in July 1958 and resulted in tracks later released on the albums Standard Coltrane (1962), Stardust (1963), and Bahia (1965). All of these tracks were later compiled on a reissue called The Stardust Session. He did a final session for Prestige in December 1958, recording tracks later released on The Believer, Stardust, and Bahia. This completed his commitment to the label, and he signed to Atlantic Records, making his first recording for his new employers on January 15, 1959 with a session on which he was co-billed with vibes player Milt Jackson, though it did not appear until 1961 with the LP Bags and Trane. In March and April 1959, Coltrane participated with the Davis group on the album Kind of Blue. Released on August 17, 1959, this landmark album known for its "modal" playing (improvisations based on scales or "modes," rather than chords) became one of the best-selling and most-acclaimed recordings in the history of jazz.

By the end of 1959, Coltrane had recorded what would be his Atlantic debut, Giant Steps, released in early 1960. The album, consisting entirely of Coltrane compositions, in a sense marked his real debut as a leading jazz performer, even though the 33-year-old musician had released three previous solo albums and made numerous other recordings. His next Atlantic album, Coltrane Jazz, was mostly recorded in November and December 1959 and released in February 1961. In April 1960, he finally left the Davis band and formally launched his solo career, beginning an engagement at the Jazz Gallery in New York, accompanied by pianist Steve Kuhn (soon replaced by McCoy Tyner), bassist Steve Davis, and drummer Pete La Roca (later replaced by Billy Higgins and then Elvin Jones). During this period, he increasingly played soprano saxophone as well as tenor.

In October 1960, Coltrane recorded a series of sessions for Atlantic that would produce material for several albums, including a final track used on Coltrane Jazz and tunes used on My Favorite Things (March 1961), Coltrane Plays the Blues (July 1962), and Coltrane's Sound (June 1964). His soprano version of "My Favorite Things," from the Richard Rodgers/Oscar Hammerstein II musical The Sound of Music, would become a signature song for him. During the winter of 1960-1961, bassist Reggie Workman replaced Steve Davis in his band, and saxophone and flute player Eric Dolphy gradually became a member of the group.

In the wake of the commercial success of "My Favorite Things," Coltrane's star rose, and he was signed away from Atlantic as the flagship artist of the newly formed Impulse! Records label, an imprint of ABC-Paramount, though in May he cut a final album for Atlantic, Olé (February 1962). The following month, he completed his Impulse! debut, Africa/Brass. By this time, his playing was frequently in a style alternately dubbed "avant-garde," "free," or "The New Thing." Like Ornette Coleman, he played seemingly formless, extended solos that some listeners found tremendously impressive, and others decried as noise. In November 1961, John Tynan, writing in Down Beat, referred to Coltrane's playing as "anti-jazz." That month, however, Coltrane recorded one of his most celebrated albums, Live at the Village Vanguard, an LP paced by the 16-minute improvisation "Chasin' the Trane."

Between April and June 1962, Coltrane cut his next Impulse! studio album, another release called simply Coltrane when it appeared later in the year. Working with producer Bob Thiele, he began to do extensive studio sessions, far more than Impulse! could profitably release at the time, especially with Prestige and Atlantic still putting out their own archival albums. But the material would serve the label well after the saxophonist's untimely death. Thiele acknowledged that Coltrane's next three Impulse! albums to be released, Ballads, Duke Ellington and John Coltrane, and John Coltrane with Johnny Hartman (all 1963), were recorded at his behest to quiet the critics of Coltrane's more extreme playing. Impressions (1963), drawn from live and studio recordings made in 1962 and 1963, was a more representative effort, as was 1964's Live at Birdland, also a combination of live and studio tracks, despite its title. But Crescent, also released in 1964, seemed to find a middle ground between traditional and free playing, and was welcomed by critics. This trend was continued with 1965's A Love Supreme, one of Coltrane's best-loved albums, which earned him two Grammy nominations, for Jazz Composition and Performance, and became his biggest-selling record. Also during the year, Impulse! released the standards collection The John Coltrane Quartet Plays... and another album of "free" playing, Ascension, as well as New Thing at Newport, a live album consisting of one side by Coltrane and the other by Archie Shepp.

The year 1966 saw the release of the albums Kulu Se Mama and Meditations, Coltrane's last recordings to appear during his lifetime, though he had finished and approved release for his next album, Expression, the Friday before his death in July 1967. He died suddenly of liver cancer, entering the hospital on a Sunday and expiring in the early morning hours of the next day. He had left behind a considerable body of unreleased work that came out in subsequent years, including "Live" at the Village Vanguard Again! (1967), Om (1967), Cosmic Music (1968), Selflessness (1969), Transition (1969), Sun Ship (1971), Africa/Brass, Vol. 2 (1974), Interstellar Space (1974), and First Meditations (For Quartet) (1977), all on Impulse!

Compilations and releases of archival live recordings brought him a series of Grammy nominations, including Best Jazz Performance for the Atlantic album The Coltrane Legacy in 1970; Best Jazz Performance, Group, and Best Jazz Performance, Soloist, for "Giant Steps" from the Atlantic album Alternate Takes in 1974; and Best Jazz Performance, Group, and Best Jazz Performance, Soloist, for Afro Blue Impressions in 1977. He won the 1981 Grammy for Best Jazz Performance, Soloist, for Bye Bye Blackbird, an album of recordings made live in Europe in 1962, and he was given the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1992, 25 years after his death.

Even more previously unreleased material has surfaced since then, including the discovery of the Monk and Coltrane live concert At Carnegie Hall and a complete version of his 1966 Seattle concert, Offering: Live at Temple University. The saxophonist was also the subject of director John Scheinfeld's acclaimed 2017 film Chasing Trane: The John Coltrane Documentary. In 2018, Impulse! released Both Directions at Once: The Lost Album, an archival release documenting a previously unheard session from 1963. The next year brought another unreleased album, Blue World, which dated from a June 1964 session recorded in between the sessions for Crescent and A Love Supreme.

John Coltrane is sometimes described as one of jazz's most influential musicians, and certainly there are other artists whose playing is heavily indebted to him. Perhaps more to the point, Coltrane is influential by example, inspiring musicians to experiment, take chances, and devote themselves to their craft. The controversy about his work has never died down, but partially as a result, his name lives on and his recordings continue to remain available and to be reissued frequently.

5 Minutes That Will Make You Love John Coltrane

Coltrane

changed the game in American music a few times over. Here’s a guided

tour to his career, courtesy of 15 musicians, scholars, poets, writers

and other experts.

February 7, 2024

New York Times

Yes, it’s time for this series to focus on John Coltrane — perhaps the most sanctified musician in the whole Black American tradition, who other artists sometimes refer to simply as “St. John.”

Born in Hamlet, N.C., and raised in High Point, Coltrane arrived on the New York scene in the 1950s, by way of Philadelphia and the Miles Davis Quintet. In the short years between that arrival and his death, in 1967, the world around Coltrane would change dramatically. He reached the peak of his creative forces as a saxophonist just as American society was bursting apart in the 1960s, and as freedom movements drummed colonialism out of the African continent. Though introspective and soft-spoken, singularly allergic to grandstanding, Coltrane felt powerfully concerned with the fate of the world, and he was sure that music had a role to play in turning the tides.

He closely studied spiritual and musical systems from Africa and India, sensing that ancient, non-Western traditions might light the path toward a new creative approach. For many of his contemporaries, Trane’s saxophone became synonymous with a liberated mind and body. And, however ineffable, it carried a message. As A.B. Spellman wrote in a poem after the saxophonist’s death, “trane’s horn had words in it.”

Coltrane changed the game in American music a few times over: first, with a style that felt like such a force of nature, one critic labeled it “sheets of sound,” as if he were commanding monsoon rains. Then, in 1960, the flipbook-fast harmonies of “Giant Steps” upped the expectations for jazz improvisers by a big margin. Swinging in the other direction, Trane brought his whirling-dervish attack to a more stationary style of music: raga-like, harmonically planted “modal” tunes such as “Impressions,” “Africa” and “India.”

In the mid-60s, compelled by his own spirituality, by the outward-bound “free jazz” being made by artists like Sun Ra, Ornette Coleman and Eric Dolphy, and by the music he’d been playing at home with his second wife, the pianist and composer Alice (McLeod) Coltrane, the saxophonist wrote and recorded his masterpiece, “A Love Supreme.” A paean to God, it also sounds like an attempt to unleash purifying flames on a world gone wrong. And from there, he went even further; his last two years saw Coltrane pushing rhythm and tone beyond their breaking points.

Below you’ll find a guided tour of Coltrane’s career, courtesy of 15 musicians, scholars, poets, writers and other experts whose lives have been cleansed, and made brighter, by the sheets of sound. You can find a playlist at the bottom of the article, and be sure to leave your own favorites in the comments.

◆ ◆ ◆

A.B. Spellman, poet and author

“Blue Train”

When at the end I compile the elements of my life into debits and assets, near the top of the assets list will be my many cathartic evenings spent in clubs listening to John Coltrane live. If you think that the recordings are powerful, imagine sitting 15 feet from that power as it was in the making. I can vividly remember hearing Trane and Thelonious Monk, every set, every night, at the 5 Spot after Monk’s return to club gigs in New York in 1957. Before that summer, nobody in the New York jazz world would have marked Coltrane as the next big thing — he was thought to be a middle-of-the-pack hard-bop saxophonist. But he blossomed under Monk. The wonder of the 5 Spot evenings was in bearing witness to his blooming into this Godzilla expressionist who grew larger every set, every evening.

There was an open logic to his lines. “Blue Train,” the record that he made to satisfy his contract with Blue Note, was a masterpiece exemplification of that period. Of the tunes on that date, the title track was the summary statement. It had a sort of free grammar to it, a long solo comprising three themes all stated and developed with clarity, deep emotional meaning and perfect resolution. I have heard this solo hundreds of times, and it is new each time. “Blue Train” is why we return to art when the terrors of the material world chase us home.

◆ ◆ ◆

Dr. Farah Jasmine Griffin, scholar

“Naima”

A love song inspired by and named for John Coltrane’s first wife, “Naima” is a contemplative ballad that exudes a sense of reverence for the beloved. The saxophonist known for long, complex solos does not take one. He chooses instead to open and close with a slow, meditative statement, made all the more so because it glides over the sustained, repeated pedal tone played by Paul Chambers on bass. Following Wynton Kelly’s eloquent piano solo, Trane returns and we accompany him someplace close to heaven, and it’s oh so pretty there. This love song is a prayer. As such, it looks toward his more explicitly spiritual works that follow in the years to come. Is it any wonder that generations of jazz musicians approach “Naima” not only as a standard, but also as scripture? Listen closely and fall in love.

◆ ◆ ◆

Dr. Joshua Myers, scholar

“Alabama”

I could see the grief fill the eyes of the poet Askia Muhammad Touré: “It was like, oh, they are killing our babies?” Moments after recounting what it was to be Black and alive in the days after the Sept. 15, 1963, killings of children at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., he was the first person to fully capture for me the meaning of John Coltrane’s “Alabama.” Composed as an offering of solidarity in the wake of Black collective grief, these are melodic lines atop a pulsating rhythm, imploring us — then, and especially now — to never allow the children to be sacrificed again.

◆ ◆ ◆

Dave Liebman, saxophonist

“Crescent”

“Crescent” is my all-time favorite recording, presenting an amazing opportunity to get into the musical language that Trane was speaking. The power of the music lies in the great feel and skill of the rhythm section. “Crescent” has several outstanding elements. There is a very apparent, deep feeling that John carried with him all the time but especially in the late period, when his sound broadened and took on a darker tone quality. “Crescent” features some melodic passages that are clearly lyrical. Additionally, the harmony of the chord changes makes this track very interesting and moving. It demands attentive listening.

◆ ◆ ◆

Yusef Komunyakaa, poet

“My Favorite Things”

John Coltrane had come a long ways from Hamlet, N.C. Trane could wail through brass, and then create a lyrical contrast that catches the listener slightly off guard. He even could take a popular tune and internalize it until it was his, and such is the case with “My Favorite Things.” Yes, one hears a practiced reaching and ascension — a translation of 14-hour rehearsals. His tone was mind and body, honed into a ritual of purification. Coltrane did not believe his fellow musicians were mere sidemen. As a group, they could articulate and blow true feeling — without sentimentality. Because a conversation grows between instruments, the listener participates without being over-conscious of popping fingers, tapping feet or shaking hips. Thus, listening is active, and perhaps this is why Coltrane said, “When you begin to see the possibilities of music, you desire to do something good for people, to help humanity free itself from its hang-ups.”

To lift myself up, I tune into a joyful reminder — yes, I return to Coltrane’s version of “My Favorite Things” often. His spirit journeys to the melody, and we improvise our own personal catalog of delights. He elongates a tune into a precise tonal reckoning — no mishaps or blips on the cosmic screen. In fact, this man was blowing feeling as a way of dealing with the mind and heart at the same time, even holding himself accountable. There’s a taking apart, and then a putting back together tonally. Trane knew how to walk the listener to the edge of extended possibility, to peer down into the existential void, and then sweet-talk the listener to a sanctuary of the hour. And, in this sense, especially in a tune such as “My Favorite Things,” one may enter the John Coltrane Church, where we participants become co-creators of meaning.

◆ ◆ ◆

Willard Jenkins, journalist and author

“Out of This World”

Pondering John Coltrane track recommendations, the inevitable faves float by the mind first: “Blue Train,” “My Favorite Things,” “Giant Steps,” “Africa” or the “A Love Supreme” suite. And don’t dare sleep on the hypnotic “Tunji,” used powerfully by Spike Lee in his 1990 film “Mo’ Better Blues.” But the more I contemplated, I kept coming back to Trane’s engagement with “Out of This World,” from the “Coltrane” album (Impulse!), a classic example of his transforming a Great American Songbook selection. The Coltrane quartet takes that piece to regions the songwriters Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer doubtless never imagined, deep to an African realm, particularly courtesy of Elvin Jones’s distinctive, roiling drums, with Jimmy Garrison’s cascading bass lines and McCoy Tyner’s insistent block chords propelling Coltrane’s tenor saxophone theme statement and subsequent essay. Clocking in at over 14 minutes, there’s plenty to dig into for both the Trane-addicted and the newly initiated.

◆ ◆ ◆

Giovanni Russonello, Times jazz critic

“Acknowledgment”

Coltrane’s landmark suite “A Love Supreme” ends with “Psalm,” a slow, seeking devotional, its melody set to a poem giving thanks to God. It is a remarkably direct conversation between a musician and the divine, channeled through his roaring quartet. But the part of the suite that will stick most firmly in your mind and body comes at the start. Part 1, “Acknowledgment,” features a plodding incantation, first set by Jimmy Garrison’s bass, then played by the saxophone, then intoned in Coltrane’s husky voice: “A love supreme. A love supreme.” It is among the simplest things that this master of midair complexity would ever play. It feels so foundational, so grounding, that it’s almost like a creation myth. But jazz, as a discipline, had already been around for more than 50 years when he wrote it. What, then, was he creating? Once it was recorded, Coltrane knew he had reached some kind of summit: This was the beginning of the end for his legendary quartet. It had made some of the most transcendent music of the 20th century; its mission was accomplished.

◆ ◆ ◆

Dr. Lewis Porter, pianist and Coltrane biographer

“Hackensack” (live)

In my continuing research on Coltrane, I find that listeners new to his work often have difficulty relating it to the jazz tradition. This excerpt from a TV program, taped on March 28, 1960, in Düsseldorf, Germany, is not part of his “official” legacy of recordings, but we are lucky that it was preserved. It is perfect evidence that Coltrane had established deep roots in swing and blues before moving out from there. The tune is “Hackensack,” by Thelonious Monk, and the AABA chord sequence is taken from Gershwin’s swing classic “Oh, Lady Be Good!”

Coltrane begins his improvisation at 1:05 with some down-home riffing, so that when he then brings on some incredibly fast notes, it makes a tremendously effective contrast. He always seemed to get right into “the zone,” and he generates so much power during his three-chorus solo that one almost marvels that the unflappable Stan Getz follows him at all. At 6:55, Coltrane brings in some new riffing, again illustrating how connected he is to the jazz tradition. Speaking of the tradition: At the bridge (7:12), the saxophonists look at each other, trying to decide who will take over, and then wordlessly decide to keep playing together.

◆ ◆ ◆

Marcus J. Moore, jazz writer

“Sun Ship”

When jazz purists consider John Coltrane’s discography, they often stop around 1965, when the saxophonist eschewed calm arrangements for harsher ones. The band, which included McCoy Tyner on piano, Jimmy Garrison on bass and Elvin Jones on drums, still sought communion with higher powers, but it seemed they wanted to play the loudest notes possible to foster it. So when people hear “Sun Ship,” they might hear noise. But I hear freedom in the stomping drums, in the volcanic wail of the horn. I hear a band breaking the rules of what jazz was supposed to be, and a bandleader sidestepping a box he never fit. In the song’s opening moments, Jones and Coltrane trade equally riotous commotion: The drum kit sounds like it’s being assaulted; the sax all belchy and heaving. By the time Garrison and Tyner join the fray, the intensity heightens, barreling through like a truck with no brakes. I realize this imagery makes the song seem unpleasant, but the beauty is in the challenge it presents. It’s a rewarding listen, conveying angst and autonomy at every turn.

◆ ◆ ◆

Laura Karpman, film composer

“Summertime”

I have spent most of my adult musical life thinking about how sound and imagery interact. What makes music dark, what makes it light. How can you create specific identifiable emotions? Music is a powerful tool to create multiple subtexts. John Coltrane would’ve been an absolutely spectacular film composer. The decisions he makes are so often rooted in drama.

In “My Favorite Things” (1961), he takes a simple tune at its most shell-like value, makes some rhythmic changes and enriches the harmonic language, but the piece gets truly radical in its long solo. Here, Coltrane creates an entirely new composition. He sticks fundamentally to one chord — an E major 9 — and stays with it. It is the brightest of lights: The music ascends and ascends, builds and bursts even greater blinding optimism, creating a new, powerful original composition. He builds an entire world out of a single chord.

“Summertime,” from the same album, is another perfect example of Coltrane’s ability to radically recontextualize pre-existing music. I’ve always thought that “Summertime” was highly influenced, even lifted, from the spiritual “Motherless Child.” In Gershwin’s original, as well as countless covers, it has a winsome, beautiful lullaby quality. But Coltrane attacks it in this version — it’s sharp, it’s angular, it has edges. He doesn’t want this “Summertime” to be a remembrance of things past, but a midcentury modernist call to action. Coltrane consistently takes existing tunes and recomposes them to add emotional drama and rich subtext. Pure genius.

Hear John Coltrane's Story

Soon after, Coltrane resolved to clean up his act. He would later write, in the 1964 liner notes to A Love Supreme, "In the year of 1957, I experienced, by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening, which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life."

But Coltrane didn't always stay the clean course. As he also wrote in the album's notes, "As time and events moved on, I entered into a phase which is contradictory to the pledge and away from the esteemed path. But thankfully now, through the merciful hand of God, I do perceive and have been fully reinformed of his omnipotence. It is truly a love supreme."

The album is, in many ways, a reaffirmation of faith. And the suite lays out what you might call its four phases: "Acknowledgement," "Resolution," "Pursuance" and "Psalms." A Love Supreme has even spawned something of a religious sect. Reverend Franzo Wayne King is pastor of the Saint John Coltrane African Orthodox Church in San Francisco. The congregation mixes African Orthodox liturgy with Coltrane's quotes and a heavy dose of his music. Pastor King calls the album the cornerstone of his 200-member church.

While it's unknown whether Coltrane would have wanted to be worshiped or have his art deified, it's clear in every way that he saw A Love Supreme as much more than just another recording. Coltrane took control of every detail of the album, unlike any of his other works, including writing the liner notes and an accompanying poem. The poem, it's been discovered, is written to match the slow music of the fourth movement, "Psalms." It's a connection Coltrane hints at cryptically in the liner notes.

Pastor King remembers the day his congregation made the discovery. "It was so funny. We were here. We had been collected as a community, and we used to just read it and try to put some passion in it, you know. And then one day, we were reading the album, because he said the last part is 'Psalms,' which is in context, written context. And we said, 'Well, what is he trying to say here?' And then we put it on and sang, 'A love supreme. I would do all I can to be worthy of you, oh, Lord.' It's kind of like Pentecostal preaching, you know," Pastor King says. "We had a great day. We woke up and found out that the music and the words went together, and that was like a further encouragement that John Coltrane was, indeed, you know, sent by God and that that sound had really jumped down from the throne of heaven, so to speak."

While Pastor King sees explicit Christian symbolism in A Love Supreme, others point out that Coltrane took a much more general view. Coltrane was careful to say that while he was raised Christian, his searchings had led him to realize that all religions had a piece of the truth.

"He told me, he says, 'I respond to what's around me,'" remembers Tyner. "That's the way it should be, you know? And it was just—I couldn't wait to go to work at night. It was just such a wonderful experience. I mean, I didn't know what we were going to do. We couldn't really explain why things came together so well, you know, and why it was, you know, meant to be. I mean, it's hard to explain things like that."

http://www.sfgate.com/entertainment/article/Coltrane-at-80-a-talent-supreme-2469266.php

Coltrane at 80 -- A talent supreme

by Greg Tate

Special to The San Francisco Chronicle

September 22, 2006

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Coltrane

John Coltrane

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

John Coltrane, 1963

John William Coltrane (September 23, 1926 – July 17, 1967) was an American jazz saxophonist, bandleader and composer. He is among the most influential and acclaimed figures in the history of jazz and 20th-century music.

Born and raised in North Carolina, Coltrane moved to Philadelphia after graduating from high school, where he studied music. Working in the bebop and hard bop idioms early in his career, Coltrane helped pioneer the use of modes and was one of the players at the forefront of free jazz. He led at least fifty recording sessions and appeared on many albums by other musicians, including trumpeter Miles Davis and pianist Thelonious Monk. Over the course of his career, Coltrane's music took on an increasingly spiritual dimension, as exemplified on his most acclaimed album A Love Supreme (1965) and others.[1] Decades after his death, Coltrane remains influential, and he has received numerous posthumous awards, including a special Pulitzer Prize, and was canonized by the African Orthodox Church.[2]

His second wife was pianist and harpist Alice Coltrane. The couple had three children: John Jr.[3] (1964–1982), a bassist; Ravi (born 1965), a saxophonist; and Oran (born 1967), a saxophonist, guitarist, drummer and singer.[4][5][6]

Biography

1926–1945: Early life

Coltrane was born in his parents' apartment at 200 Hamlet Avenue in Hamlet, North Carolina, on September 23, 1926.[7] His father was John R. Coltrane[8] and his mother was Alice Blair.[9] He grew up in High Point, North Carolina, and attended William Penn High School. While in high school, Coltrane played clarinet and alto horn in a community band[10] before switching to the saxophone, after being influenced by the likes of Lester Young and Johnny Hodges.[11][12] Beginning in December 1938, his father, aunt, and grandparents died within a few months of one another, leaving him to be raised by his mother and a close cousin.[13] In June 1943, shortly after graduating from high school, Coltrane and his family moved to Philadelphia, where he got a job at a sugar refinery. In September that year, his 17th birthday, his mother bought him his first saxophone, an alto.[9] From 1944 to 1945, Coltrane took saxophone lessons at the Ornstein School of Music with Mike Guerra.[14] From early to mid-1945, he had his first professional work as a musician: a "cocktail lounge trio" with piano and guitar.[15]

An important moment in the progression of Coltrane's musical development occurred on June 5, 1945, when he saw Charlie Parker perform for the first time. In a DownBeat magazine article in 1960 he recalled: "the first time I heard Bird play, it hit me right between the eyes."

1945–1946: Military service

To avoid being drafted by the Army, Coltrane enlisted in the Navy on August 6, 1945, the day the first U.S. atomic bomb was dropped on Japan.[16] He was trained as an apprentice seaman at Sampson Naval Training Station in upstate New York before he was shipped to Pearl Harbor,[16] where he was stationed at Manana Barracks,[17] the largest posting of African American servicemen in the world.[18] By the time he got to Hawaii in late 1945, the Navy was downsizing. Coltrane's musical talent was recognized, and he became one of the few Navy men to serve as a musician without having been granted musician's rating when he joined the Melody Masters, the base swing band.[16] Because the Melody Masters was an all-white band, Coltrane was treated as a guest performer to avoid alerting superior officers of his participation in the band.[19] He continued to perform other duties when not playing with the band, including kitchen and security details. By the end of his service, he had assumed a leadership role in the band. His first recordings, an informal session in Hawaii with Navy musicians, occurred on July 13, 1946.[20] He played alto saxophone on a selection of jazz standards and bebop tunes.[21] He was officially discharged from the Navy on August 8, 1946. He was awarded the American Campaign Medal, Asiatic–Pacific Campaign Medal and the World War II Victory Medal.

1946–1954: Immediate post-war career

After being discharged from the Navy as a seaman first class in August 1946, Coltrane returned to Philadelphia, where the city's bustling jazz scene offered him many opportunities for both learning and playing.[22] Coltrane used the G.I. Bill to enroll at the Granoff School of Music, where he studied music theory with jazz guitarist and composer Dennis Sandole.[23] Coltrane would continue to be under Sandole's tutelage from 1946 into the early 1950s.[24] Coltrane also took saxophone lessons with Matthew Rastelli, a saxophone teacher at Granoff once a week for about two or three years, but the lessons stopped when Coltrane's G.I. Bill funds ran out.[25] After touring with King Kolax, he joined a band led by Jimmy Heath, who was introduced to Coltrane's playing by his former Navy buddy, trumpeter William Massey, who had played with Coltrane in the Melody Masters.[26] Although he started on alto saxophone, he began playing tenor saxophone in 1947 with Eddie Vinson.[27]

Coltrane called this a time when "a wider area of listening opened up for me. There were many things that people like Hawk [Coleman Hawkins], and Ben [Webster] and Tab Smith were doing in the '40s that I didn't understand, but that I felt emotionally."[28] A significant influence, according to tenor saxophonist Odean Pope, was the Philadelphia pianist, composer, and theorist Hasaan Ibn Ali. "Hasaan was the clue to...the system that Trane uses. Hasaan was the great influence on Trane's melodic concept."[29] Coltrane became fanatical about practicing and developing his craft, practicing "25 hours a day" according to Jimmy Heath. Heath recalls an incident in a hotel in San Francisco when after a complaint was issued, Coltrane took the horn out of his mouth and practiced fingering for a full hour.[30] Such was his dedication; it was common for him to fall asleep with the horn still in his mouth or practice a single note for hours on end.[31]

Charlie Parker, who Coltrane had first heard perform before his time in the Navy, became an idol, and he and Coltrane would play together occasionally in the late 1940s. He was a member of groups led by Dizzy Gillespie, Earl Bostic, and Johnny Hodges in the early to mid-1950s.

1955–1957: Miles and Monk period

In 1955, Coltrane was freelancing in Philadelphia while studying with Sandole when he received a call from trumpeter Miles Davis. Davis had been successful in the 1940s, but his reputation and work had been damaged in part by heroin addiction; he was again active and about to form a quintet. Coltrane was with this edition of the Davis band (known as the "First Great Quintet"—along with Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, and Philly Joe Jones on drums) from October 1955 to April 1957 (with a few absences). During this period Davis released several influential recordings that revealed the first signs of Coltrane's growing ability. This quintet, represented by two marathon recording sessions for Prestige in 1956, resulted in the albums Cookin', Relaxin', Workin', and Steamin'. The "First Great Quintet" disbanded due in part to Coltrane's heroin addiction.[32]

During the later part of 1957, Coltrane worked with Thelonious Monk at New York's Five Spot Café, and played in Monk's quartet (July–December 1957), but, owing to contractual conflicts, took part in only one official studio recording session with this group. Coltrane recorded many sessions for Prestige under his own name at this time, but Monk refused to record for his old label.[33] A private recording made by Juanita Naima Coltrane of a 1958 reunion of the group was issued by Blue Note Records as Live at the Five Spot—Discovery! in 1993. A high quality tape of a concert given by this quartet in November 1957 was found later, and was released by Blue Note in 2005. Recorded by Voice of America, the performances confirm the group's reputation, and the resulting album, Thelonious Monk Quartet with John Coltrane at Carnegie Hall, is very highly rated.

Blue Train, Coltrane's sole date as leader for Blue Note, featuring trumpeter Lee Morgan, bassist Paul Chambers, and trombonist Curtis Fuller, is often considered his best album from this period. Four of its five tracks are original Coltrane compositions, and the title track, "Moment's Notice", and "Lazy Bird", have become standards.

1958: Davis and Coltrane

Coltrane rejoined Davis in January 1958. In October of that year, jazz critic Ira Gitler coined the term "sheets of sound"[34] to describe the style Coltrane developed with Monk and was perfecting in Davis's group, now a sextet. His playing was compressed, with rapid runs cascading in very many notes per minute. Coltrane recalled: "I found that there were a certain number of chord progressions to play in a given time, and sometimes what I played didn't work out in eighth notes, sixteenth notes, or triplets. I had to put the notes in uneven groups like fives and sevens in order to get them all in."[35]

Coltrane stayed with Davis until April 1960, working with alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley; pianists Red Garland, Bill Evans, and Wynton Kelly; bassist Paul Chambers; and drummers Philly Joe Jones and Jimmy Cobb. During this time he participated in the Davis sessions Milestones and Kind of Blue, and the concert recordings Miles & Monk at Newport (1963) and Jazz at the Plaza (1958).

1959–1961: Period with Atlantic Records

At the end of this period, Coltrane recorded Giant Steps (1960), his issued album as leader for Atlantic which contained only his compositions.[36] The album's title track is generally considered to have one of the most difficult chord progressions of any widely played jazz composition,[37] eventually referred to as Coltrane changes.[38] His development of these cycles led to further experimentation with improvised melody and harmony that he continued throughout his career.[39]

Coltrane formed his first quartet for live performances in 1960 for an appearance at the Jazz Gallery in New York City.[40] After moving through different personnel, including Steve Kuhn, Pete La Roca, and Billy Higgins, he kept pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Steve Davis, and drummer Elvin Jones.[41][42] Tyner, a native of Philadelphia, had been a friend of Coltrane for some years, and the two men had an understanding that Tyner would join the band when he felt ready.[43][44] My Favorite Things (1961) was the first album recorded by this band.[45] It was Coltrane's first album on soprano saxophone,[46] which he began practicing while with Miles Davis.[47] It was considered an unconventional move because the instrument was more associated with earlier jazz.[48]

1961–1962: First years with Impulse! Records

In May 1961, Coltrane's contract with Atlantic was bought by Impulse!.[49] The move to Impulse! meant that Coltrane resumed his recording relationship with engineer Rudy Van Gelder, who had recorded his and Davis's sessions for Prestige. He recorded most of his albums for Impulse! at Van Gelder's studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

By early 1961, bassist Davis had been replaced by Reggie Workman, while Eric Dolphy joined the group as a second horn. The quintet had a celebrated and extensively recorded residency at the Village Vanguard, which demonstrated Coltrane's new direction. It included the most experimental music he had played, influenced by Indian ragas, modal jazz, and free jazz. John Gilmore, a longtime saxophonist with musician Sun Ra, was particularly influential; after hearing a Gilmore performance, Coltrane is reported to have said, "He's got it! Gilmore's got the concept!"[50] The most celebrated of the Vanguard tunes, the 15-minute blues "Chasin' the 'Trane", was strongly inspired by Gilmore's music.[51]

In 1961, Coltrane began pairing Workman with a second bassist, usually Art Davis or Donald Garrett. Garrett recalled playing a tape for Coltrane where "I was playing with another bass player. We were doing some things rhythmically, and Coltrane became excited about the sound. We got the same kind of sound you get from the East Indian water drum. One bass remains in the lower register and is the stabilizing, pulsating thing, while the other bass is free to improvise, like the right hand would be on the drum. So Coltrane liked the idea."[52] Coltrane also recalled: "I thought another bass would add that certain rhythmic sound. We were playing a lot of stuff with a sort of suspended rhythm, with one bass playing a series of notes around one point, and it seemed that another bass could fill in the spaces."[53] According to Eric Dolphy, one night: "Wilbur Ware came in and up on the stand so they had three basses going. John and I got off the stand and listened."[53] Coltrane employed two basses on the 1961 albums Olé Coltrane and Africa/Brass, and later on The John Coltrane Quartet Plays and Ascension. Both Reggie Workman and Jimmy Garrison play bass on the 1961 Village Vanguard recordings of "India" and "Miles' Mode". [54]

During this period, critics were divided in their estimation of Coltrane, who had radically altered his style. Audiences, too, were perplexed; in France he was booed during his final tour with Davis. In 1961, DownBeat magazine called Coltrane and Dolphy players of "anti-jazz" in an article that bewildered and upset the musicians.[51] Coltrane admitted some of his early solos were based mostly on technical ideas. Furthermore, Dolphy's angular, voice-like playing earned him a reputation as a figurehead of the "New Thing", also known as free jazz, a movement led by Ornette Coleman which was denigrated by some jazz musicians (including Davis) and critics. But as Coltrane's style developed, he was determined to make every performance "a whole expression of one's being".[55]

1962–1965: Classic Quartet period

In 1962, Dolphy departed and Jimmy Garrison replaced Workman as bassist. From then on, the "Classic Quartet", as it came to be known, with Tyner, Garrison, and Jones, produced searching, spiritually driven work. Coltrane was moving toward a more harmonically static style that allowed him to expand his improvisations rhythmically, melodically, and motivically. Harmonically complex music was still present, but on stage Coltrane heavily favored continually reworking his "standards": "Impressions", "My Favorite Things", and "I Want to Talk About You".

The criticism of the quintet with Dolphy may have affected Coltrane. In contrast to the radicalism of his 1961 recordings at the Village Vanguard, his studio albums in the following two years (with the exception of Coltrane, 1962, which featured a blistering version of Harold Arlen's "Out of This World") were much more conservative. He recorded an album of ballads and participated in album collaborations with Duke Ellington and singer Johnny Hartman, a baritone who specialized in ballads. The album Ballads (recorded 1961–62) is emblematic of Coltrane's versatility, as the quartet shed new light on standards such as "It's Easy to Remember". Despite a more polished approach in the studio, in concert the quartet continued to balance "standards" and its own more exploratory and challenging music, as can be heard on the albums Impressions (recorded 1961–63), Live at Birdland and Newport '63 (both recorded 1963). Impressions consists of two extended jams including the title track along with "Dear Old Stockholm", "After the Rain" and a blues. Coltrane later said he enjoyed having a "balanced catalogue".[56]

On March 6, 1963, the group entered Van Gelder Studio in New Jersey and recorded a session that was lost for decades after its master tape was destroyed by Impulse Records to cut down on storage space. On June 29, 2018, Impulse! released Both Directions at Once: The Lost Album, made up of seven tracks made from a spare copy Coltrane had given to his wife.[57][58] On March 7, 1963, they were joined in the studio by Hartman for the recording of six tracks for the John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman album, released that July.

Impulse! followed the successful "lost album" release with 2019's Blue World, made up of a 1964 soundtrack to the film The Cat in the Bag, recorded in June 1964.

The Classic Quartet produced their best-selling album, A Love Supreme, in December 1964. A culmination of much of Coltrane's work up to this point, this four-part suite is an ode to his faith in and love for God. These spiritual concerns characterized much of Coltrane's composing and playing from this point onwards—as can be seen from album titles such as Ascension, Om and Meditations. The fourth movement of A Love Supreme, "Psalm", is, in fact, a musical setting for an original poem to God written by Coltrane, and printed in the album's liner notes. Coltrane plays almost exactly one note for each syllable of the poem, and bases his phrasing on the words. The album was composed at Coltrane's home in Dix Hills on Long Island.

The quartet played A Love Supreme live only three times, recorded twice – in July 1965 at a concert in Antibes, France and in October 1965 in Seattle, Washington.[59] A recording of the Antibes concert was released by Impulse! in 2002 on the remastered Deluxe Edition of A Love Supreme,[60] and again in 2015 on the "Super Deluxe Edition" of The Complete Masters.[61] A recently discovered second amateur recording titled "A Love Supreme: Live in Seattle" was released in 2021.[62]

1965: Adding to the quartet and Avant-garde Jazz

In his late period, Coltrane showed an interest in the avant-garde jazz of Ornette Coleman,[63] Albert Ayler,[64] and Sun Ra. He was especially influenced by the dissonance of Ayler's trio with bassist Gary Peacock,[65] who had worked with Paul Bley, and drummer Sunny Murray, whose playing was honed with Cecil Taylor as leader. Coltrane championed many young free jazz musicians such as Archie Shepp,[66] and under his influence Impulse! became a leading free jazz label.

After A Love Supreme was recorded, Ayler's style became more prominent in Coltrane's music. A series of recordings with the Classic Quartet in the first half of 1965 show Coltrane's playing becoming abstract, with greater incorporation of devices like multiphonics, use of overtones, and playing in the altissimo register, as well as a mutated return of Coltrane's sheets of sound. In the studio, he all but abandoned soprano saxophone to concentrate on tenor. The quartet responded by playing with increasing freedom. The group's evolution can be traced through the albums The John Coltrane Quartet Plays, Living Space, Transition, New Thing at Newport, Sun Ship, and First Meditations.

In June 1965, he went into Van Gelder's studio with ten other musicians (including Shepp,[67] Pharoah Sanders,[67] Freddie Hubbard,[67] Marion Brown, and John Tchicai[67]) to record Ascension, a 38-minute piece that included solos by young avant-garde musicians.[66] The album was controversial primarily for the collective improvisation sections that separated the solos. After recording with the quartet over the next few months, Coltrane invited Sanders to join the band in September 1965. While Coltrane frequently used overblowing as an emotional exclamation-point, Sanders "was involved in the search for 'human' sounds on his instrument,"[68] employing "a tone which blasted like a blow torch"[69] and drastically expanding the vocabulary of his horn by employing multiphonics, growling, and "high register squeals [that] could imitate not only the human song but the human cry and shriek as well."[70] Regarding Coltrane's decision to add Sanders to the band, Gary Giddins wrote "Those who had followed Coltrane to the edge of the galaxy now had the added challenge of a player who appeared to have little contact with earth."[71]

1965–1967: The second quartet

By late 1965, Coltrane was regularly augmenting his group with Sanders and other free jazz musicians. Rashied Ali joined the group as a second drummer. This was the end of the quartet. Claiming he was unable to hear himself over the two drummers, Tyner left the band shortly after the recording of Meditations. Jones left in early 1966, dissatisfied by sharing drumming duties with Ali and stating that, concerning Coltrane's latest music, "only poets can understand it".[72] In interviews, Tyner and Jones both voiced their displeasure with the music's direction; however, they would incorporate some of the intensity of free jazz in their solo work. Later, both musicians expressed tremendous respect for Coltrane: regarding his late music, Jones stated: "Well, of course it's far out, because this is a tremendous mind that's involved, you know. You wouldn't expect Einstein to be playing jacks, would you?"[73] Tyner recalled: "He was constantly pushing forward. He never rested on his laurels, he was always looking for what's next... he was always searching, like a scientist in a lab, looking for something new, a different direction... He kept hearing these sounds in his head..."[74] Jones and Tyner both recorded tributes to Coltrane, Tyner with Echoes of a Friend (1972) and Blues for Coltrane: A Tribute to John Coltrane (1987), and Jones with Live in Japan 1978: Dear John C. (1978) and Tribute to John Coltrane "A Love Supreme" (1994).

There is speculation that in 1965 Coltrane began using LSD,[75][76] informing the "cosmic" transcendence of his late period. Nat Hentoff wrote: "it is as if he and Sanders were speaking with 'the gift of tongues' - as if their insights were of such compelling force that they have to transcend ordinary ways of musical speech and ordinary textures to be able to convey that part of the essence of being they have touched."[77] After the departure of Tyner and Jones, Coltrane led a quintet with Sanders on tenor saxophone, his second wife Alice Coltrane on piano, Garrison on bass, and Ali on drums. When touring, the group was known for playing long versions of their repertoire, many stretching beyond 30 minutes to an hour. In concert, solos by band members often extended beyond fifteen minutes.

The group can be heard on several concert recordings from 1966, including Live at the Village Vanguard Again! and Live in Japan. In 1967, Coltrane entered the studio several times. Although pieces with Sanders have surfaced (the unusual "To Be" has both men on flute), most of the recordings were either with the quartet minus Sanders (Expression and Stellar Regions) or as a duo with Ali. The latter duo produced six performances that appear on the album Interstellar Space. Coltrane also continued to tour with the second quartet up until two months before his death; his penultimate live performance and final recorded one, a radio broadcast for the Olatunji Center of African Culture in New York City, was eventually released as an album in 2001.

1967: Illness and death

Coltrane died of liver cancer at the age of 40 on July 17, 1967, at Huntington Hospital on Long Island. His funeral was held four days later at St. Peter's Lutheran Church in New York City. The service was started by the Albert Ayler Quartet and finished by the Ornette Coleman Quartet.[78] Coltrane is buried at Pinelawn Cemetery in Farmingdale, New York.

Coltrane's death surprised many in the music community who were unaware of his condition. Miles Davis said, "Coltrane's death shocked everyone, took everyone by surprise. I knew he hadn't looked too good ... But I didn't know he was that sick—or even sick at all."[82]

Instruments

Coltrane started out on alto saxophone, but in 1947, when he joined King Kolax's band, he switched to tenor saxophone, the instrument he became known for playing.[83] In the early 1960s, during his contract with Atlantic, he also played soprano saxophone.[83]

His preference for playing melody higher on the range of the tenor saxophone is attributed to his training on alto horn and clarinet. His "sound concept", manipulated in one's vocal tract, of the tenor was set higher than the normal range of the instrument.[84] Coltrane observed how his experience playing the soprano saxophone gradually affected his style on the tenor, stating "the soprano, by being this small instrument, I found that playing the lowest note on it was like playing ... one of the middle notes in the tenor ... I found that I would play all over this instrument ... And on tenor, I hadn't always played all over it, because I was playing certain ideas which would just run in certain ranges ... By playing on the soprano and becoming accustomed to playing from that low B-flat on up, it soon got so when I went to tenor, I found myself doing the same thing ... And this caused ... the willingness to change and just try to play... as much of the instrument as possible."[85]

Toward the end of his career, he experimented with flute in his live performances and studio recordings (Live at the Village Vanguard Again!, Expression). After Eric Dolphy died in June 1964, his mother gave Coltrane his flute and bass clarinet.[86]

According to drummer Rashied Ali, Coltrane had an interest in the drums.[87] He would often have a spare drum set on concert stages that he would play.[88] His interest in the drums and his penchant for having solos with the drums resonated on tracks such as "Pursuance" and "The Drum Thing" from A Love Supreme and Crescent, respectively. It resulted in the album Interstellar Space with Ali.[89] In an interview with Nat Hentoff in late 1965 or early 1966, Coltrane stated: "I feel the need for more time, more rhythm all around me. And with more than one drummer, the rhythm can be more multi-directional."[77] In an August 1966 interview with Frank Kofsky, Coltrane repeatedly emphasized his affinity for drums, saying "I feel so strongly about drums, I really do."[90] Later that year, Coltrane would record the music released posthumously on Offering: Live at Temple University, which features Ali on drums supplemented by three percussionists.

Coltrane's tenor (Selmer Mark VI, serial number 125571, dated 1965) and soprano (Selmer Mark VI, serial number 99626, dated 1962) saxophones were auctioned on February 20, 2005, to raise money for the John Coltrane Foundation.[91]

Although he rarely played alto, he owned a prototype Yamaha alto saxophone given to him by the company as an endorsement in 1966. He can be heard playing it on live albums recorded in Japan, such as Second Night in Tokyo, and is pictured using it on the cover of the compilation Live in Japan. He can also be heard playing the Yamaha alto on the album Stellar Regions.[92]

Personal life and religious beliefs

Upbringing and early influences

Coltrane was born and raised in a Christian home. He was influenced by religion and spirituality beginning in childhood. His maternal grandfather, the Reverend William Blair, was a minister at an African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church[93][94] in High Point, North Carolina, and his paternal grandfather, the Reverend William H. Coltrane, was an A.M.E. Zion minister in Hamlet, North Carolina.[93] Critic Norman Weinstein observed the parallel between Coltrane's music and his experience in the southern church,[95] which included practicing music there as a youth.

First marriage

In 1955, Coltrane married Naima (née Juanita Grubbs). Naima Coltrane, a Muslim convert, heavily influenced his spirituality. When the couple married, she had a five-year-old daughter named Antonia, later named Syeeda. Coltrane adopted Syeeda. He met Naima at the home of bassist Steve Davis in Philadelphia. The love ballad he wrote to honor his wife, "Naima", was Coltrane's favorite composition. In 1956, the couple left Philadelphia with their six-year-old daughter in tow and moved to New York City. In August 1957, Coltrane, Naima and Syeeda moved into an apartment on 103rd Street and Amsterdam Avenue in New York. A few years later, John and Naima Coltrane purchased a home at 116-60 Mexico Street in St. Albans, Queens.[96] This is the house where they would break up in 1963.[97]

About the breakup, Naima said in J. C. Thomas's Chasin' the Trane: "I could feel it was going to happen sooner or later, so I wasn't really surprised when John moved out of the house in the summer of 1963. He didn't offer any explanation. He just told me there were things he had to do, and he left only with his clothes and his horns. He stayed in a hotel sometimes, other times with his mother in Philadelphia. All he said was, 'Naima, I'm going to make a change.' Even though I could feel it coming, it hurt, and I didn't get over it for at least another year." But Coltrane kept a close relationship with Naima, even calling her in 1964 to tell her that 90% of his playing would be prayer. They remained in touch until his death in 1967. Naima Coltrane died of a heart attack in October 1996.

1957 "spiritual awakening"

In 1957, Coltrane had a religious experience that may have helped him overcome the heroin addiction[98][99] and alcoholism[99] he had struggled with since 1948.[100] In the liner notes of A Love Supreme, Coltrane states that in 1957 he experienced "by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life. At that time, in gratitude, I humbly asked to be given the means and privilege to make others happy through music." The liner notes appear to mention God in a Universalist sense and do not advocate one religion over another.[101] Further evidence of this universal view can be found in the liner notes of Meditations (1965) in which Coltrane declares, "I believe in all religions."[102]

Second marriage

In 1963, he met pianist Alice McLeod.[103] He and Alice moved in together and had two sons before he became "officially divorced from Naima in 1966, at which time [he] and Alice were immediately married."[102] John Jr. was born in 1964, Ravi in 1965, and Oranyan ("Oran") in 1967.[102] According to the musician Peter Lavezzoli, "Alice brought happiness and stability to John's life, not only because they had children, but also because they shared many of the same spiritual beliefs, particularly a mutual interest in Indian philosophy. Alice also understood what it was like to be a professional musician."[102]

Spiritual influence in music, religious exploration

After A Love Supreme, many of the titles of his songs and albums had spiritual connotations: Ascension, Meditations, Om, Selflessness, "Amen", "Ascent", "Attaining", "Dear Lord", "Prayer and Meditation Suite", and "The Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost".[102] His library of books included The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, the Bhagavad Gita, and Paramahansa Yogananda's Autobiography of a Yogi. The last of these describes, in Lavezzoli's words, a "search for universal truth, a journey that Coltrane had also undertaken. Yogananda believed that both Eastern and Western spiritual paths were efficacious, and wrote of the similarities between Krishna and Christ. This openness to different traditions resonated with Coltrane, who studied the Qur'an, the Bible, Kabbalah, and astrology with equal sincerity."[104] He also explored Hinduism, Jiddu Krishnamurti, African history, the philosophical teachings of Plato and Aristotle,[105] and Zen Buddhism.[106]

In October 1965, Coltrane recorded Om, referring to the sacred syllable in Hinduism, which symbolizes the infinite or the entire universe. Coltrane described Om as the "first syllable, the primal word, the word of power".[107] The 29-minute recording contains chants from the Hindu Bhagavad Gita[108] and the Buddhist Tibetan Book of the Dead,[109] and a recitation of a passage describing the primal verbalization "om" as a cosmic/spiritual common denominator in all things.

Study of world music

Coltrane's spiritual journey was interwoven with his investigation of world music. He believed in not only a universal musical structure that transcended ethnic distinctions, but also being able to harness the mystical language of music itself. His study of Indian music led him to believe that certain sounds and scales could "produce specific emotional meanings." According to Coltrane, the goal of a musician was to understand these forces, control them, and elicit a response from the audience. He said, "I would like to bring to people something like happiness. I would like to discover a method so that if I want it to rain, it will start right away to rain. If one of my friends is ill, I'd like to play a certain song and he will be cured; when he'd be broke, I'd bring out a different song and immediately he'd receive all the money he needed."[110]

Veneration

Saint John Coltrane | |

|---|---|

Coltrane icon at St. John Coltrane African Orthodox Church | |

| Born | September 23, 1926 Hamlet, North Carolina, US |

| Died | July 17, 1967 (aged 40) Huntington, New York, US |

| Venerated in | African Orthodox Church Episcopal Church |

| Canonized | 1982, St. John Coltrane Church, 2097 Turk Blvd, San Francisco, CA 94115 by African Orthodox Church[111] |

| Feast | December 8 (AOC) |

| Patronage | All Artists |

After Coltrane's death, a congregation called the Yardbird Temple in San Francisco began worshipping him as God incarnate.[112] The group was named after Charlie "Yardbird" Parker, whom they equated to John the Baptist.[112] The congregation became affiliated with the African Orthodox Church; this involved changing Coltrane's status from a god to a saint.[112] The resultant St. John Coltrane African Orthodox Church, San Francisco, is the only African Orthodox church that incorporates Coltrane's music and his lyrics as prayers in its liturgy.[113]

Rev. F. W. King, describing the African Orthodox Church of Saint John Coltrane, said "We are Coltrane-conscious...God dwells in the musical majesty of his sounds."[114]

Samuel G. Freedman wrote in The New York Times that

... the Coltrane church is not a gimmick or a forced alloy of nightclub music and ethereal faith. Its message of deliverance through divine sound is actually quite consistent with Coltrane's own experience and message. ... In both implicit and explicit ways, Coltrane also functioned as a religious figure. Addicted to heroin in the 1950s, he quit cold turkey, and later explained that he had heard the voice of God during his anguishing withdrawal. ... In 1966, an interviewer in Japan asked Coltrane what he hoped to be in five years, and Coltrane replied, "a saint".[112]

Coltrane is depicted as one of the 90 saints in the Dancing Saints icon of St. Gregory of Nyssa Episcopal Church in San Francisco. The icon is a 3,000-square-foot (280 m2) painting in the Byzantine iconographic style that wraps around the entire church rotunda. It was executed by Mark Dukes, an ordained deacon at the Saint John Coltrane African Orthodox Church who painted other icons of Coltrane for the Coltrane Church.[115] Saint Barnabas Episcopal Church in Newark, New Jersey, included Coltrane on its list of historical black saints and made a "case for sainthood" for him in an article on its website.[116]

Documentaries about Coltrane and the church include Alan Klingenstein's The Church of Saint Coltrane (1996),[111][117] and a 2004 program presented by Alan Yentob for the BBC.[118]

Selected discography

The discography below lists albums conceived and approved by Coltrane as a leader during his lifetime. It does not include his many releases as a sideman, sessions assembled into albums by various record labels after Coltrane's contract expired, sessions with Coltrane as a sideman later reissued with his name featured more prominently, or posthumous compilations, except for the one he approved before his death. See main discography link above for full list.

Prestige and Blue Note records

- Coltrane (debut solo LP; 1957)

- Blue Train (1958)

- John Coltrane with the Red Garland Trio (1958)

- Soultrane (1958)

Atlantic records

- Giant Steps (1960)

- Coltrane Jazz (1961)

- My Favorite Things (1961)

- Olé Coltrane (1961)

Impulse! Records

- Africa/Brass (1961)

- "Live" at the Village Vanguard (1962)

- Coltrane (1962)

- Duke Ellington & John Coltrane (1963)

- Ballads (1963)

- John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman (1963)

- Impressions (1963)

- Live at Birdland (1964)

- Crescent (1964)

- A Love Supreme (1965)

- The John Coltrane Quartet Plays (1965)

- Ascension (1966)

- New Thing at Newport (1966)

- Meditations (1966)

- Live at the Village Vanguard Again! (1966)

- Kulu Sé Mama (1967)

- Expression (1967)

Sessionography

Awards and honors

In 1965, Coltrane was inducted into the Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame. In 1972, A Love Supreme was certified gold by the RIAA for selling over half a million copies in Japan. This album was certified gold in the United States in 2001. In 1982 he was awarded a posthumous Grammy for Best Jazz Solo Performance on the album Bye Bye Blackbird, and in 1997 he was awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.[28] In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante named him one of his 100 Greatest African Americans.[119] He was awarded a special Pulitzer Prize in 2007 citing his "masterful improvisation, supreme musicianship and iconic centrality to the history of jazz."[2] He was inducted into the North Carolina Music Hall of Fame in 2009.[120]

A former home, the John Coltrane House in Philadelphia, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1999. His last home, the John Coltrane Home in the Dix Hills district of Huntington, New York, where he resided from 1964 until his death, was added to the National Register of Historic Places on June 29, 2007.

In media

A documentary on Jazz was made in 1990 by fellow musician Robert Palmer, called The World According to John Coltrane.

Chasing Trane: The John Coltrane Documentary, is a 2016 American film directed by John Scheinfeld.[121]

External links

- Official website

- John Coltrane at Curlie

- John Coltrane discography at Discogs

- John Coltrane infography

- John Coltrane discography

- Coltrane Church Website site

- John Coltrane 1957 Carnegie Hall performance in transcription and analysis

- John Coltrane Images of Trane by Lee Tanner in Jazz Times, June 1997

- Interviews from 1958–1966

LINER NOTES TO 'JOHN COLTRANE: LIVE AT BIRDLAND' BY LEROI JONES (aka) AMIRI BARAKA--Impulse label-- October 8, 1963

Live at Birdland – John Coltrane

*Bonus Track

JOHN COLTRANE QUARTET:

Original Liner Notes by Leroi Jones (aka Amiri Baraka)

Live At Birdland, Impulse Records, AS-50

October 8, 1963

One of the most baffling things about America is that despite its essentially vile profile, so much beauty continues to exist here. Perhaps it's as so many thinkers have said, that it is because of the vileness, or call it adversity, that such beauty does exist. (As balance?).

Thinking along these lines, even the title of this album can be rendered "symbolic" and more directly meaningful. John Coltrane Live At Birdland. To me, Birdland is only America in microcosm, and we know how high the mortality rate is for artists in this instant tomb. Yet, the title tells us that John Coltrane is there live. In this tiny America where the most delirious happiness can only be caused by the dollar, a man continues to make daring reference to some other kind of thought. Impossible? Listen to I Want To Talk About You.

Coltrane apparently doesn't need an ivory tower. Now that he is a master, and the slightest sound from his instrument is valuable, he is able, literally, to make his statements anywhere. Birdland included. It does not seem to matter to him (nor should it) that hovering in the background are people and artifacts that have no more to do with his music than silence.

But now I forget why I went off into this direction. Nightclubs are, finally, nightclubs. And their value is that even though they are raised or opened strictly for gain (and not the musician's) if we go to them and are able to sit, as I was for this session, and hold on, if it is a master we are listening to, we are very likely to be moved beyond the pettiness and stupidity of our beautiful enemies. John Coltrane can do this for us. He has done it for me many times, and his music is one of the reasons suicide seems so boring.

There are three numbers on the album that were recorded Live at Birdland, Afro-Blue, I Want To Talk About You, and The Promise. And while some of the non-musical hysteria has vanished from the recording, that is, after riding a subway through New York's bowels, and that subway full of all the things any man should expect to find in some thing's bowels, and then coming up stairs, to the street, and walking slowly, head down, through the traffic and failure that does shape the area, and then entering "The Jazz Corner Of The World" (a temple erected in praise of what God?), and then finally amidst that noise and glare to hear a man destroy all of it, completely, like Sodom, with just the first few notes from his horn, your "critical" sense can be erased completely, and that experience can place you somewhere a long way off from anything ugly. Still, what was of musical value that I heard that night does remain, and the emotions ... some of them completely new ... that I experience at each "objective" rehearing of this music are as valuable as anything else I know about. And all of this is on this record, and the studio pieces, Alabama and Your Lady, are among the strongest efforts on the album.

But since records, recorded "Live" or otherwise, are artifacts, that is the way they should be talked about. The few people who were at Birdland the night of October 8 who really beard what Coltrane, Jones, Tyner and Garrison were doing will probably tell you, if you ever run into them, just "exactly" what went on, and how we all reacted. I wish I had a list of all those people so that interested parties could call them and get the whole story, but then, almost anyone who's heard John and the others at a nightclub or some kind of live performance has got stories of their own. I know I've got a lot of them.