THE 500th AND FINAL MUSICAL ARTIST ENTRY IN THIS NOW COMPLETED EIGHT YEAR SERIES WAS POSTED ON THIS SITE ON SATURDAY, JANUARY 7, 2023.

BEGINNING JANUARY 14, 2023 THIS SITE WILL CONTINUE TO FUNCTION AS AN ONGOING PUBLIC ARCHIVE AND SCHOLARLY RESEARCH AND REFERENCE RESOURCE FOR THOSE WHO ARE INTERESTED IN PURSUING THEIR LOVE OF AND INTEREST IN WHAT THE VARIOUS MUSICAL ARTISTS ON THIS SITE PROVIDES IN TERMS OF BACKGROUND INFORMATION AND VARIOUS CRITICAL ANALYSES AND COMMENTARY OFFERED ON BEHALF OF EACH ARTIST ENTRY SINCE NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2020/08/horace-tapscott-1934-1999-legendary.html

PHOTO: HORACE TAPSCOTT (1934-1999)

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/horacetapscott

Horace Tapscott

Born in 1934 in Houston, Texas, Horace came from a musical family centered around his mother, Mary Malone Tapscott, who worked professionally as a singer and pianist. When Horace was nine, the family moved to Los Angeles. As a teenager in the late 1940's, Horace was surrounded by the music of Central Avenue: Art Tatum, Charlie Parker, Coleman Hawkins, Dexter Gordon, were among the many cats on the set. Around this time, Horace also began to take music lessons from teachers Dr. Samuel R. Browne and Lloyd Reese, whose other students included Eric Dolphy and Frank Morgan. Horace's musical studies included trombone in addition to piano.

In 1952, Horace graduated from Jefferson High, got married to Cecilia Payne and went into the Air Force. Horace played in an Air Force Band while he was stationed in Wyoming for his term of duty. After mustering out, he returned to Los Angeles where he worked around on various gigs until he joined the Lionel Hampton Big Band as a trombonist.

In 1959, Horace finally went with the Hampton Big Band to New York, where his friend Eric Dolphy introduced him to John Coltrane. A tough winter, a lack of gigs, and too many nights on the floor of a friend's art gallery finally sent Horace packing for sunny Southern California, where a life with wife and family awaited his return.

The sixties saw Horace emerge as a die-hard leader of the Avant Garde. Horace began to gain public notice playing with his own group, that included alto saxophonist Arthur Blythe, bassist David Bryant, and drummer Everett Brown II. Horace also appeared on records for the first time (see discography).

Horace was always outspoken about racism, politics, stereotypes, and social ethics. His forward- minded vocal presence on and off the microphone is as much a part of his art as his piano playing. As a result, he was labeled a “dissident,” categorized as an “employment risk,” and black-listed from the music industry establishment in the early 1970's. None of this slowed Horace down. He began gigging sporadically at Parks and Recreation events and for churches around Watts. This “dark period,” with his only regular gig at his friend Doug Weston's Troubadour on Los Angeles' “Restaurant Row”, was also a time of intense creativity.

Around 1977, Horace reorganized the Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra with the help of several old friends and many new faces. The Arkestra performances involve singing, dancing, and poetry in addition to the music. Soon after the new group's debut, Horace came to the attention of producer Tom Albach who contracted Horace to record a number of albums for Nimbus Records (see discography). Albach also helped introduce Horace to an international audience by arranging several European tours.

In 1979, another producer, Tosh Tanaki, took Horace to New York to record with legendary drummer Roy Haynes and bassist Dr. Art Davis (see discography). This was the beginning of a musical friendship that continued; Horace often played with Art's group at gigs around Los Angeles.

The 80's saw Horace emerge as one of jazz's premiere solo pianists. He recorded several solo piano albums for Nimbus (see discography). This phase culminated in the late 80's, with Horace sharing the bill at the Wilshire Ebell theatre with other jazz legends Andrew Hill and Randy Weston for a historic solo piano concert.

Horace kept extremely busy thru the 90's, composing new music, recording albums, and leading his group on tours of Europe and the United States--not to mention his perpetual involvement in the local community and his role as the patriarch of a large family. In 1994, Horace finally took the whole Arkestra to Europe. This tour was a huge success highlighted by the return of Arthur Blythe to the group as primary soloist.

http://www.darktree-records.com/en/artistes/horace-tapscott-artiste

HORACE TAPSCOTT

Tapscott, Horace Elva

(b. Houston, 6 April 1934; d Los Angeles, 27 February 1999).

Pianist, composer, bandleader, and social activist. Began piano studies at six and trombone two years later. Moved with his family to Los Angeles in 1943, and was enveloped in the Central Avenue scene. Studied with Samuel Browne at Jefferson High School, where he played with alto saxophonist Frank Morgan. Private tutelage with Lloyd Reese followed, and mentoring by Gerald Wilson, Melba Liston, and composer William Grant Still. Friends included Don Cherry, Billy Higgins, and Larance Marable. Worked with Gerald Wilson’s orchestra before graduating from Jefferson in 1952. Enlisted in the air force in 1953, playing in the Ft. Warren band in Wyoming, until his discharge in 1957. Joined Lionel Hampton’s band in 1959, and toured until early 1961, at times sitting in on piano and arranging charts. By the early sixties piano had become Tapscott’s exclusive instrument, forced by persistent dental problems.

At the end of 1961 he formed the Underground Musicians Association (UGMA), ten years later evolving into the Union of God’s Musicians and Artists Ascension (UGMAA) with the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra (PAPA) as one of its components. Over the years some three hundred artists were involved, including Arthur Blythe, Everett Brown, Jr., Kamau Daáood, Azar Lawrence, Roberto Miranda, Butch Morris, Wilber Morris, Sonship Theus, and Dwight Trible. Fusing art with social activism, the Arkestra developed and preserved black music and art within their community, performing on street corners, in parks, schools, churches, senior homes, social facilities and gathering spots, arts centers, and at political rallies. Although its activities tapered off by the early 1980s, the Arkestra continued performing into the 21stcentury.

Tapscott’s music ran the gamut, from free-form improvisation to folk songs and spirituals. The content, structure, and stylings of many pieces drew from the problems and routines of community life. He translated these into complex rhythmic patterns, crashing dissonances, and bittersweet melodies, using the entire range and even all the material elements (wood, strings, metal, ivories) of the piano. He composed for solo piano and small groups, the Arkestra and its choir, and even for symphony orchestra in his magnum opus, Ancestral Echoes. He was attracted to dark ostinati and a heavy bottom sound, as in “The Giant Is Awakened,” “The Dark Tree,” “Thoughts of Dar Es Salaam,” and “To the Great House.” Even when dealing with older material, such as Strayhorn’s “Lush Life,” or favored tunes from the bop era, like “Oleo” and “Now’s the Time,” Tapscott found a way to heavily root the compositions, while still exploring unique harmonic extensions.

During the 1960s Tapscott recorded with Onzy Matthews, Lou Blackburn, arranged and conducted two albums for singer and subsequent Black Panther Party leader Elaine Brown, composed and conducted the music for Sonny Criss’s Sonny’sDream (Birth of the New Cool)(1968, Prestige). His first album as leader appeared one year later,The Giant Is Awakened (Flying Dutchman), also Arthur Blythe’s recording debut. From 1978 through the mid 1980s he recorded for Interplay and Nimbus Records, labels formed by enthusiasts for Tapscott’s music. He led the Arkestra on three albums, recorded many solo albums (eleven issued to date), one duo with drummer Everett Brown, Jr., four trio discs, including the two-part live performance at the Lobero Theater in Santa Barbara, California, and one sextet album. Landmark recordings for hat ART (The Dark Tree) followed in 1989, and then two CDs for Arabesque in the 1990s. As of 2010, Nimbus West Records continues to release additional sessions and live performances.

--Steve Isoardi

BIBLIOGRAPHY

• G. Burk: “Heh-heh: Horace Tapscott in the Heart of It,” LA Weekly(July 28-August 3, 1989), 49

• B. Ratliff: “Horace Tapscott: Staring No in the Face,”CODA,no. 242 (March/April 1992), 7-11

• H. Tapscott and S. Isoardi:Songs of the Unsung: The Musical and Social Journey of Horace Tapscott (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001) [incl. discography]

• S. Isoardi: The Dark Tree: Jazz and the Community Arts in Los Angeles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006)

• D. Widener: Black Arts West: Culture and Struggle in Postwar Los Angeles (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010)

• S. Isoardi and M.D. Wilcots: Black Experience in the Fine Arts: An African American Community Arts Movement in a University Setting (Current Research in Jazz6, 2014

https://www.crj-online.org/v6/CRJ-BlackExperience.php)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horace_Tapscott

Horace Tapscott

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

HORACE TAPSCOTT IN 1986

Horace Elva Tapscott (April 6, 1934 – February 27, 1999) was an American jazz pianist and composer.[1] He formed the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra (also known as P.A.P.A., or The Ark) in 1961 and led the ensemble through the 1990s.[2]

Early life

Tapscott was born in Houston, Texas, and moved to Los Angeles, California, at the age of nine. By this time he had begun to study piano and trombone. He played with Frank Morgan, Don Cherry, and Billy Higgins as a teenager.

Later life and career

After service in the Air Force in Wyoming, he returned to Los Angeles and played trombone with various bands, notably Lionel Hampton (1959–61). Soon after, though, he quit playing trombone and focused on piano.[3]

In 1961 Tapscott formed the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra,[4] with the aim of preserving, developing and performing African-American music. As his vision grew, this became just one part of a larger organization in 1963, the Underground Musicians Association (UGMA), which later changed name to the Union of God's Musicians and Artists Ascension (UGMAA).[3] Arthur Blythe, Stanley Crouch, Butch Morris, Wilber Morris, David Murray, Jimmy Woods, Nate Morgan and Guido Sinclair all performed in Tapscott's Arkestra at one time or another.[2] Tapscott and his work are the subjects of the UCLA Horace Tapscott Jazz Collection.[5]

Enthusiasts of his music formed two labels in the 1970s and 1980s, Interplay and Nimbus, for which he recorded.[3]

From allmusicguide.com:

"His pianistic technique was hard and percussive, likened by some to that of Thelonious Monk and Herbie Nichols and every bit as distinctive. In contexts ranging from freely improvised duos to highly arranged big bands, Tapscott exhibited a solo and compositional voice that was his own."

Discography

As leader:

The Giant Is Awakened (Flying Dutchman, 1969) - as Horace Tapscott Quintet

Songs of the Unsung (Interplay, 1978)

In New York (Interplay, 1979)

Lighthouse 79, Vol. 1 (Nimbus West, 1979 [2009])

Lighthouse 79, Vol. 2 (Nimbus West, 1979 [2009])

At the Crossroads (with Everett Brown, Jr.) (Nimbus West, 1980)

Dial 'B' for Barbra (Nimbus West, 1981) - as Horace Tapscott Sextet

Live At Lobero (with Roberto Miranda and Sonship) (Nimbus West, 1981)

Live At Lobero, Vol. II (with Roberto Miranda and Sonship) (Nimbus West, 1981)

Little Africa (piano solo) (Art Union, 1983)

Dissent or Descent (Nimbus West, 1984 [1998])

Autumn Colors (Bopland, 1984; reissue: Interplay, 1990)

The Dark Tree (HatArt, 1991) - originally released as two separate volumes and re-released as a 2-CD set

Horace Tapscott's Arkestra Live in Chicago (1993)

Among Friends (with Sonny Simmons) (Jazz Friends Productions, 1995 [1999])

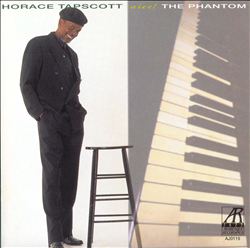

Aiee! The Phantom (Arabesque, 1996)

Thoughts of Dar es Salaam (Arabesque, 1997)

Live at Théâtre Du Chêne Noir - Avignon, France 1989 (with Michael Session) (The Village, 2020)

Legacies for Our Grandchildren - Live in Hollywood, 1995 (Dark Tree, 2022) - as Horace Tapscott Quintet

With the Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra

The Call (Nimbus West, 1978)

Flight 17 (Nimbus West, 1978)

Live at I.U.C.C. (Nimbus West, 1979)

Why Don't You Listen? Live at LACMA, 1998 (with the Great Voice of UGMAA) (Dark Tree, 2019)

Ancestral Echoes: The Covina Sessions, 1976 (Dark Tree, 2020)

Live at Century City Playhouse 9/9/79 (Nimbus West, 2020)

As sideman

With Lou Blackburn

Jazz Frontier (Imperial, 1963)

Two Note Samba (Imperial, 1963)

Both titles compiled on The Complete Imperial Sessions (Blue Note, 2006)

With Roberto Miranda's Home Music Ensemble

Live at Bing Theatre - Los Angeles, 1985 (Dark Tree, 2021)

As composer and arranger

With Sonny Criss

Crisscraft (Muse, 1975) - composer only

Bibliography

Dailey, Raleigh. "The Dark Tree: Jazz and the Community Arts in Los Angeles" (review). Notes Volume 63, Number 3, March 2007, pp. 632–634.

Isoardi, Steven L. The Dark Tree: Jazz and the Community Arts in Los Angeles. April 2006. 394p. illus. index. University of California, $34.95 (0-520-24591-1).

Isoardi, Steven L. Songs of the Unsung: The Musical and Social Journey of Horace Tapscott. Duke University Press, 2001.

Isoardi, Steven L. The Music Finds a Way: A PAPA/UGMAA Oral History of Growing Up In Postwar South Central Los Angeles. Dark Tree, 2020.

External links

Horace Tapscott discography at Discogs

Horace Tapscott "A Fireside Chat With Horace Tapscott", with Fred Jung in Jazz Weekly

Horace Tapscott "Listening In: An Interview with Horace Tapscott", with Bob Rosenbaum, Los Angeles, October 1982

Horace Tapscott Interview, Center for Oral History Research, UCLA

https://www.nhpr.org/post/horace-tapscotts-giant-re-awakened-reissue#stream/0

Horace Tapscott's Giant Re-Awakened In A Reissue

New Hamphire Public Radio

NHPR

Horace Tapscott led a big band in 1969, but his debut was for a quintet drawn from its ranks. Fresh Air jazz critic Kevin Whitehead reviews a reissue of The Giant is Awakened.

Copyright 2015 NPR.

To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.

Transcript:

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. In the 1960s and early '70s, Los Angeles-based pianist Horace Tapscott was one of the jazz musicians who identified with emerging African-American political and social movements. He was a mentor to many musicians. Jazz critic Kevin Whitehead has a review of a re-issue of Tapscott's 1969 debut album. He led a big band at the time, but this recording is with his quintet, which was drawn from the ranks of his big band.

(SOUNDBITE OF HORACE TAPSCOTT AND THE PAN-AFRIKAN PEOPLES ARKESTRA SONG, "THE GIANT IS AWAKENED")

KEVIN WHITEHEAD, BYLINE: That's "The Giant Is Awakened" from the newly reissued Horace Tapscott album of the same name. The title refers to a newly mobilized African-American public. It was recorded in 1969 when that decade's upheavals were much on Tapscott's mind. Back then, his dashiki clad Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra was a South Los Angeles institution playing concerts in the park and from the back of a truck. Even his quintet music could reflect community empowerment. The ascending, intensifying riff on "The Dark Tree" sounds like forces gathering and gaining strength.

(SOUNDBITE OF HORACE TAPSCOTT AND THE PAN-AFRIKAN PEOPLES ARKESTRA SONG, "THE DARK TREE")

WHITEHEAD: Playing "The Dark Tree" for years on the streets, seeing neighborhood kids dance to it, Horace Tapscott learned something. Even when his piano solos got kind of abstract, listeners would accept the music if the beat was good. His arkestra had multiple bass players, so it was no problem using two of them here - David Bryant and Walter Savage Jr. Sometimes one plucks the strings while the other bows.

(SOUNDBITE OF HORACE TAPSCOTT AND THE PAN-AFRIKAN PEOPLES ARKESTRA SONG, "THE DARK TREE")

WHITEHEAD: Everett Brown Jr. from Kansas City on drums. The band's horn player is the 28-year-old rhythm and blues trained alto saxophonist Arthur Blythe on his first recording. A decade later, Blythe would be a bona fide jazz star, partly due to his catchy tunes. There's a too-short version of one of them here, "For Fats."

(SOUNDBITE OF HORACE TAPSCOTT AND THE PAN-AFRIKAN PEOPLES ARKESTRA SONG, "FOR FATS")

WHITEHEAD: Arthur Blythe has one of the most arresting saxophone sounds of our time, searing and bluesy with a serrated vibrato and pungent low notes. It was thrilling to be in a room when he played. He's still with us but no longer active, sidelined with Parkinson's. Well-regarded as Arthur Blythe is, he's probably not celebrated nearly enough.

(SOUNDBITE OF HORACE TAPSCOTT AND THE PAN-AFRIKAN PEOPLES ARKESTRA SONG, "NYJA'S THEME")

WHITEHEAD: Horace Tapscott wasn't totally happy with this album when it came out in 1969. He thought his piano was mixed too loud. One thing about Tapscott, he'd never put himself above anybody. He was an idealist and all-around good guy. "The Giant Is Awakened" didn't make him or Arthur Blythe instant stars; it only had four tracks, one almost too short for radio and two others way too long. But it started people talking. Horace Tapscott would go on to record in many settings, from solo to full orchestra. He'd play in Europe a lot and make a few records in New York. And when he was done, he'd head straight back to his city of angels.

(SOUNDBITE OF HORACE TAPSCOTT AND THE PAN-AFRIKAN PEOPLES ARKESTRA SONG, "NYJA'S THEME")

GROSS: Kevin Whitehead writes for Point of Departure and is the author of "Why Jazz?" Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/horace-tapscott-mn0000219530/biography

Horace Tapscott

(1934-1999)

Artist Biography by Chris Kelsey

While Los Angeles is the power center of the popular

music industry, it's always been a backwater as far as jazz is

concerned. That's not because L.A. hasn't produced more than it's share

of great players: a roll call of major players who made L.A. their home

at some point would include Art Pepper, Dexter Gordon, Ornette Coleman, Gerry Mulligan, Chet Baker, and Charles Mingus,

among many others. L.A.'s second-class status in the jazz world

probably has more to do with the fact that it's about as geographically

distant from the music's capitol -- New York City -- as is possible

while still remaining on the same continent. Given the fact that, over

the last several decades, New York critics have become probably the most

provincial in jazzdom, it's little wonder that so many great

California-based musicians are less critically vaunted than they might

justifiably be. Simply put, being famous is not something a jazz

musician from Los Angeles can count on. Horace Tapscott was the quintessence of the neglected Californian. Tapscott

was a powerful, highly individual, bop-tinged pianist with avant-garde

leanings; a legend and something of a father figure to latter

generations of L.A.-based free jazz players, Tapscott

labored mostly on the fringes of the critical mainstream, recording

prolifically, but mostly for the small, poorly distributed Nimbus label.

The quality of the music on those releases, however, was almost

invariably high. His pianistic technique was hard and percussive,

likened by some to that of Thelonious Monk and Herbie Nichols and every bit as distinctive. In contexts ranging from freely improvised duos to highly arranged big bands, Tapscott exhibited a solo and compositional voice that was his own.

Tapscott

was born in Houston, TX, to a musical family. His mother, Mary Malone

Tapscott, was a professional singer and pianist. At the age of nine, Tapscott moved with his family to Los Angeles. Tapscott reached maturity at a critical time in the history of L.A. jazz. The late '40s saw musicians the caliber of Dexter Gordon, Art Tatum, and Coleman Hawkins play the city's Central Avenue clubs with regularity; Charlie Parker also made the city home for a brief -- and infamous -- period. Saxophonist Buddy Collette and drummer Gerald Wilson were friends of the family. In his teens, Tapscott studied music with Dr. Samuel Brown and Lloyd Reese (students of the latter also included saxophonists Frank Morgan and Eric Dolphy). Tapscott

studied trombone and piano. He graduated from Jefferson High School in

1952. He enlisted in the Air Force and played in a service band while

stationed in Wyoming. After his discharge, Tapscott returned to Los Angeles, where he worked freelance. A stint as a trombonist with Lionel Hampton's big band took Tapscott to New York in 1959, where he was introduced by Eric Dolphy to John Coltrane. After a brief period in the city, Tapscott moved back to L.A. Around this time, Tapscott began concentrating on the piano. In the '60s, Tapscott

became involved with the jazz avant-garde and community activism. In

1961, he helped found the Union of God's Musicians and Artists

Ascension, which eventually spawned his Pan-African People's Arkestra.

Both groups were designed to further the interests of creative young

black jazz musicians. In 1968, Tapscott composed and arranged music for an acclaimed LP by the saxophonist Sonny Criss

entitled The Birth of the New Cool. He had also begun leading a small

group that included the soon-to-be-famous alto saxophonist Arthur Blythe. This band produced Tapscott's first album as a leader, The Giant Is Awakened, in 1969. Tapscott

spent the next decade playing his own music and working in the

community. His activism got him labeled as a troublemaker by many in the

musical establishment. Paying gigs were scarce in the '70s, although Tapscott

continued to create, performing at Parks and Recreation events and in

churches around Watts. During this period, his only regular gig was at

the Troubador on L.A.'s Restaurant Row. In 1977, Tapscott

revived the dormant Pan-Afrikan People's Arkestra. The band became a

multidisciplinary troupe, combining music with dance and poetry. The

group came to the attention of producer Tom Albach, who began recording Tapscott

for the Nimbus label. The long succession of albums to follow would

become the basis of the pianist/composer's small but growing reputation.

Albach also booked European tours for Tapscott, thus exposing his music worldwide. In 1979, Tapscott recorded with drummer Roy Haynes and bassist Art Taylor. In the '80s, Tapscott

continued to flourish creatively as he continued to record for Nimbus

(and in 1989, Hat Art) and perform both at home and abroad. In 1994, Tapscott took the entire Arkestra on a tour of Europe, with Blythe as a featured soloist. In the '90s, Tapscott had the opportunity -- long denied -- of recording for a well-distributed domestic label. Arabesque issued aiee! the Phantom, a quintet date that featured bassist Reggie Workman, drummer Andrew Cyrille, trumpeter Marcus Belgrave, and alto saxophonist Abraham Burton. Arabesque followed that with Thoughts of Dar-Es Salaam (1997), a trio set that included bassist Ray Drummond and drummer Billy Hart. At the time of his death in 1999 of lung cancer, it seemed that Tapscott's work was finally beginning to receive the attention it deserved.

Back in Los Angeles, he founded the first Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra in 1961. At first, the Arkestra played for free on street corners and in different churches. Tapscott and several other members of the Arkestra began conducting summer music workshops for the children of Watts. He also led his own small combo whose changing personnel included Azar Lawrence and Black Arthur (better known as Arthur Blythe). In the early days of the Arkestra there were other gigs with Slim Gaillard, Sarah Vaughan, Lorez Alexandria, and Freddie Hill, but soon the community music program began taking up more of his time.

Over two decades several hundred musicians passed through the ranks of the Arkestra. The Arkestra itself survived many difficult moments, including the Watts riots. At the height of the riots, the police drew their guns on the bandleader and ordered the musicians to stop playing, claiming that the music was inciting the people outside. When the police left, the musicians began playing again. For much of its existence the Arkestra’s regular home---on the last Sunday of each month---was Rev. E. Edwards's Immanuel United Church of Christ. But when the reverend became ill, Tapscott’s UGMAA Foundation (Union of God’s Musicians and Artists Ascension) set up shop in its own building, formerly a printer’s workshop. Tapscott described the Foundation’s main function as “the education of young musicians in a noncompetitive, commercial-free atmosphere of love and reverence for the music.”

Until the late 1970s, Tapscott’s only LP as a leader was the small combo recording The Giant Is Awakened (Flying Dutchman, 1969). His music started to reach a wider audience thanks to the independent label Nimbus Records, which proceeded to issue a number of small group and Arkestra recordings as well as eight volumes of solo piano sessions. Later recordings, in the 1980s and '90s, were made for the Hat Art and Arabesque labels.

The following interview took place at Tapscott’s home in the South Central section of Los Angeles, in April 1982, after his first appearances before European audiences.

As a musician you have been closely involved with the black community in Los Angeles for well over twenty years. What made you decide to concentrate your efforts on community music making rather than seek fame or fortune on the road?

Years ago, my mentor, Mr. Samuel Brown at Jefferson High, told me he would show me the ways if I promised to pass them on too. I couldn’t do it formally, that is to say through the schoolrooms. I wanted to do that, but I lost the feeling for it. I could do the same thing perhaps outside, directly. And so we started in little houses, garages. We had four or five different places.

You see, by growing up with the music and the musicians around here in Los Angeles, I had a chance to get a panoramic view and see what happened to certain cats, and why it happened. The main reason was because they had no support. At one point, when the people were coming off their jobs on Friday night and Saturday, they were looking forward to the music because they could dance and all that. So, the musician was thought of in this light. But it’s something else for the music to live through the years, and to last and have a meaning. Like the music of Duke Ellington, that will always live. Well, that’s the kind of music I like to be in, the classic type that maybe people can appreciate. I want to teach with it, and speak of a whole era and why it happened. But it needs all sides to teach it and balance it.

You originally studied trombone as well as piano. When did you put down the trombone for good?

When I was about nineteen, but I did go back with Lionel Hampton on ’bone for a year. That was in the last part of 1960. I was playing the piano then, writing and arranging, but I wasn’t working.

Probably the pianist Gerald Wilson told him about Lester Robertson. And Lester told him that he’d get the other cat. So, Lester called me one night and said. “Hey, man, you want to go to New York?” We didn’t have no job and the rent was due. And I said, “Yeah, man, let’s go.”

We went and there’s Lionel Hampton. We got put out in the snow after a while when the band stopped working. Hamp went to Africa and only took five pieces, so we were left in the city for about four months. When the band came back, we went through the South. That bus ride almost killed me, it was mean. We had to check to see if we could go in the front door to eat. The bus driver was white, so Lionel Hampton always sent him first. One night, the cats were so tired on the bus that we said, “Hey, man, no,” and we just busted on in. We was just ready for anything, tired. Oh man, that was a hell of a ride.

When the band came back here to Los Angeles to play at a club on Sunset Boulevard, I got off the bus. It was four o’clock in the morning, because the gig was over, and they was on their way back to New York. I was sitting there on the bus and said, “What am I doing here? I don’t want to go back to New York like this.” So I got off the bus. And then no one discovered I was gone until they got to Arizona.

What were the origins of the Underground Musicians Association?

Well, it started because of the actual players. There were several of us around in the area here in the early ’50s that were branching off into some other kinds of music. We’d be playing constantly, night and day, at Linda Hill’s home on 75th and Central. And then in my garage on 56th Street and Avalon, five or six of us started our band---Lester Robertson, Jimmy Woods, myself, and several other people. When we began in the early ’60s, the music started seeming like it had to go somewhere else. And I started playing Negro spirituals and all the music that was written by black composers. So, that in itself started a whole new thing for the cats. I had started doing a lot of my own kinds of writing.

When did you start writing your own music?

In the ’50s, but most of it I developed pretty much in the ’60s because I had a band. By that time, half of the cats in town were around. They got the word that we were rehearsing five nights a week, so they just came by. So we hooked up and we started writing. We started having to get everybody in the band to learn how to write, because you had musicians here to play whatever you wrote the next day.

After twenty years of working in Watts, do you think the UGMAA’s efforts have had some effect, even culturally, toward building a stable and constructive black community?

Songs of the Unsung

The Musical and Social Journey of Horace Tapscott

Illustrations: 46 b&w photos

February 2001

Author: Horace Tapscott

Editor: Steven L. Isoardi

Contributor(s): Steven L. Isoardi, William Marshall

Subjects: African American Studies and Black Diaspora, General Interest > Biography, Letters, Memoirs, Music > Jazz

Songs of the Unsung is the autobiography of Los Angeles jazz musician and activist Horace Tapscott (1934–1999). A pianist who ardently believed in the power of music to connect people, Tapscott was a beloved and influential character who touched many yet has remained unknown to the majority of Americans. In addition to being “his” story, Songs of the Unsung is the story of Los Angeles’s cultural and political evolution over the last half of the twentieth century, of the origins of many of the most important avant-garde musicians still on the scene today, and of a rich and varied body of music.

Tapscott’s narrative covers his early life in segregated Houston, his move to California in 1943, life as a player in the Air Force band in the early fifties, and his travels with the Lionel Hampton Band. He reflects on how the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra (the “Ark”), an organization he founded in 1961 to preserve and spread African and African-American music, eventually became the Union of God’s Musicians and Artists Ascension—a group that not only performed musically but was active in the civil rights movement, youth education, and community programs. Songs of the Unsung also includes Tapscott’s vivid descriptions of the Watts neighborhood insurrection of 1965 and the L.A. upheavals of 1992, interactions with both the Black Panthers and the L.A.P.D., his involvement in Motown’s West Coast scene, the growth of his musical reputation abroad, and stories about many of his musician-activist friends, including Billy Higgins, Don Cherry, Buddy Collette, Arthur Blythe, Lawrence and Wilber Morris, Linda Hill, Elaine Brown, Stanley Crouch, and Sun Ra.

With a foreword by Steven Isoardi, a brief introduction by actor William Marshall, a full discography of Tapscott’s recordings, and many fine photographs, Songs of the Unsung is the inspiring story of one of America’s most unassuming twentieth-century heroes.

Praise

“Songs of the Unsung is one of those special autobiographical narratives that comes along once in a while, and successfully captivates its reading audience with the complete candor of the person telling the story! This is an important sociological document, for it tells the life of Horace Tapscott, one of the most unique figures in the jazz of Black Los Angeles. . . . What is most unique about Songs of the Unsung is that it reveals a man who not only lived jazz, but contributed to it in meaningful ways, and was a walking masterpiece of the personal philosophy he advocated. He lived to teach, help others, perform, create. Horace Tapscott succeeded at each. Songs of the Unsung lets the reader see how he did it. Songs of the Unsung is excellent reading. This book entertains and enlightens at the same time, and is a fine reading experience!” — Lee Prosser, Jazz Review

“Songs of the Unsung offers a glimpse into the life of a jazz musician who resolved not to abandon the place where he started out—the streets of South-Central.” — Jonathan Kirsch, Los Angeles Times

“[A] raw, intimate autobiography of L.A. free jazz pianist, trombonist, and composer Tapscott. . . . [T]his retrospective will enable jazz enthusiasts to revel in the life of a unique and talented underground musician. . . .” — Publishers Weekly

“[Isoardi] preserves Tapscott’s part-preacher, part-hipster patois—in which, for example, he inflects the word ‘out’ to describe free jazz, police brutality, injustice, good luck, violent rage, unexpected generosity, spontaneous affection and insanity. Songs of the Unsung is a witness to hope, one man’s determination to create art of lasting value and the power of music to connect people. It is, in the profoundest sense, ‘out’ ” — Jim Gerard, Washington Post

“[O]ffers fascinating insights into Tapscott’s work as a composer and bandleader, as well as his memories of L.A. during the turbulent 1960s.” — Aaron Cohen, DownBeat

“[T]his engaging reminiscence reveals Tapscott as both a provocative musician and an iconoclastic community advocate. With a nontechnical narrative that flows like a novel, this memoir constitutes an appealing and informative document of musical and social history for readers at all levels.” — A. D. Franklin, Choice

“A valuable firsthand account of American music and culture that will make a welcome addition to any collection.” — Library Journal

“Horace Tapscott . . . emerges as an eternal symbol of all that is noble in the music in transition community. This highly advanced theme emerges from a detailed life history that is nothing short of stunning. . . . Songs of the Unsung is an important statement in the philosophy of improvised music. Highly recommended.” — James D. Armstrong, Jr., Jazz Now

“Isoardi has done a fine job of preserving Tapscott’s voice—the narrative is fluent, conversational in tone and packed with both colourful incident and tart social commentary. . . . [A]s a gripping account of a quietly heroic life, and as a rare document about the West Coast’s black cultural underground, Songs of the Unsung is essential reading.” — Graham Lock, Jazzwise“Page after page, Tapscott offhandedly knocks down stereotypes about African-American communities, like pines behind an eruption. . . . Tapscott’s controversial narrative, filled with stories about ‘the cats’ and their ‘out’ behavior is fascinating. . . . But more valuable than the book’s entertainment quotient is its map of possibilities.” — Greg Burk, LA Weekly

“Tapscott stuck pretty much to the straight and narrow and his story is one of music as embedded in community. . . . Tapscott, a thoughtful man and a fine storyteller, has a tale more interesting than the usual fare, and along the way he touches on numerous tales of racism, the merger of the black and white union locals in Los Angeles, reflections on the studio scene and drugs, the various travails of the black community in LA, and many of his musical and educational endeavors over the years, both in and out of the Arkestra. Isoardi’s editing . . . still preserves much of the flavor of someone just sitting back and talking. Anyone interested in the plights of the modern jazz performer, and of course jazz in LA, will find this book of great interest.” — Stuart Kremsky, IAJRC Journal

“The details and local lore of Songs are beautifully rendered, and Tapscott’s modesty and perseverance are qualities to behold.” — Hua Hsu, The Wire

“Topics such as food drives, grassroots educational activities, and the sharing of resources are all inextricable from the discussion of the Arkestra’s music, which makes this book quite a bit more substantive than the run-of-the-mill jazz bio from a broader cultural standpoint.” — George Drake, Signal to Noise

Songs of the Unsung . . . sets forth an astonishing, searingly honest view of one segment of music history that is indeed unsung. . . . [The] memoir reminds us with stunning candor that too much has happened under the radar of the jazz industry. . . . We need more books like Songs of the Unsung, by which we can come to understand creative musicians as agents of change at home, effecting local pockets of activity with universal ramifications. For Tapscott provides us with an unwritten truth behind this radically unfinished music called jazz." — Vijay Iyer, Current Musicology

“Songs of the Unsung—It’s about time! Horace Tapscott was one of the first guys doing it in the community. His life has been a big influence on me. He made sure younger and older people played music. He is one of the true giants of this music in the way he played it, wrote it, and lived it.” — Billy Higgins

“During those days the greatest thing happened to me. I got something I needed when I was on the radio . . . . While I was being interviewed, the telephone rang. It was a woman calling from almost her deathbed in the hospital to tell me that my music had helped to heal her, someone with a real soft voice, sobbing as she spoke, like she had been under some kind of dark cloth, saying that finally some light came in because of the sounds.

‘Thank you so very much for playing and please don’t stop.’ I never knew her name, never met her. I don’t know if she’s still alive or not. But what she said to me justified everything that I believed in. There wasn’t anything happening moneywise and sometimes you’re down in the dumps, but you have to pull your head up. When things like that happen, those little small things, well, that was the idea of the sounds in the first place.” — from Chapter Twelve

“This is a splendid book, a wonderfully accessible first person narrative by an important and unusual figure in the history of jazz and the history of Black Los Angeles. Tapscott has an important story to tell and he conveys his experiences, opinions, and philosophy clearly through an engaging and conversational style filled with rich descriptions and witty observations.”

—George Lipsitz, author of Dangerous Crossroads: Popular Music, Postmodernism, and the Poetics of Place

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Foreword / Steven Isoardi

Introduction / William Marshall

Photographs compiled by Michael Dett Wilcots

2. California

3. Setting the Pace

4. Central Avenue

5. Military Service

6. On the Road with Lionel Hampton

7. To Preserve and Develop Black Culture

8. The Fire This Time

9. In the Middle of It

10. Stayin’ Alive

11. The Union of God’s Musicians and Artists Ascension

12. Settling into the Community

13. Movements to the Present

14. Reflections and Directions

Postscript: From the Funeral Service

“For Cecilia” by Horace Tapscott

“PAPA, The Lean Griot” by Kamau Daáood

Appendix: A Partial List of UGMAA Artists, 1961–1998

Discography I: Horace Tapscott

Discography II: Music from the Ark

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/15/arts/music/horace-tapscott-pan-afrikan-peoples-arkestra.html

Horace Tapscott Was a Force in L.A. Jazz. A New Set May Expand His Reach.

“60 Years,” a compilation marking the 60th anniversary of his Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra, spotlights the pianist and community organizer, who died in 1999.

There’s a name engraved in the sidewalk along Degnan Boulevard in Los Angeles’ Leimert Park neighborhood: Horace Tapscott, the local pianist and organizer whose ensemble, the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra, gave many musicians their first gigs and helped heal a community impacted by racism.

“He saved Los Angeles when it comes to progressive music,” said the vocalist Dwight Trible, a performer with the Arkestra since 1987, in a telephone interview. “Because if you were going to get involved in that, you had to come through Horace Tapscott.”

Tapscott started the group in 1961 and maintained it until his death in 1999, at 64. Yet his name has never rung as loudly outside of L.A. He didn’t tour much and his albums of vigorous Afrocentric jazz weren’t released on mainstream record labels. A new compilation titled “60 Years,” out Friday, may change that.

The double LP set collects unreleased songs from every decade of the Arkestra’s existence, up to its present-day iteration with the drummer Mekala Session at the helm. Through a mix of home and live recordings, along with written track-by-track breakdowns from past and present members in the album’s liner notes, “60 Years” offers perspective on a group that’s largely flown under the radar.

Featuring Bill Madison on drums; David Bryant on bass; Lester Robertson on trombone; and Arthur Blythe, Jimmy Woods and Guido Sinclair on saxophone; the Arkestra started in Tapscott’s garage and grew dramatically over the following 17 years.

Tapscott founded the band and the Union of God’s Musicians and Artists Ascension, an artists’ collective, to provide more gigs for progressive jazz musicians living in L.A., and to get local children involved in the arts. His own journey in music began when he was young; his mother, Mary Lou Malone, was a stride pianist and tuba player and as a teen he played trombone locally before entering the Air Force.

After a tour of the South with the vibraphonist Lionel Hampton’s band, he wasn’t enamored with life on the road. During a stop in L.A., where Tapscott had lived since he was 9, he hopped off Hampton’s tour bus for good. “No one discovered I was gone until they got to Arizona,” he said in a 1982 interview.

“He was way more interested in feeling and sounding like himself with his friends, who were also really unique,” Session said on a video call from Los Angeles. Still, Tapscott’s mission stretched beyond music. During the Watts riots in 1965, he had the band play in the middle of the road on a flatbed truck. (Police responded, with guns drawn.) The group would often perform in churches, community centers, prisons and hospitals for little to no money, and at benefits for Black Panther leaders, drawing attention from the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Though Tapscott released his first album, “The Giant Is Awakened,” with a separate quintet in 1969, his debut LP with the Arkestra didn’t arrive until “The Call,” a mix of bluesy ballads and orchestral arrangements with grand flourishes, in 1978. Along the way, noted musicians and vocalists like Nate Morgan, Kamau Daaood, Adele Sebastian and Phil Ranelin played in the band.

Trible came across Tapscott in the late 1980s as a singer in another group who wanted to work with the Arkestra. Two weeks after they performed separately at a festival, Tapscott offered an invitation. “He said, ‘I want you to come to my house tomorrow at 3 o’clock,’ and he hung up the phone,” Trible remembered with a laugh. “And just about every concert that Horace played from that time on, I sang with him in some capacity.”

Trible performed a fiery rendition of “Little Africa,” a rapturous gospel song, with the current version of the Arkestra at National Sawdust in Brooklyn earlier this month. The festive night of shouts and praise featured older and younger Arkestra members, and served as a showcase for Session, the band’s leader since 2018; Mekala is the son of the saxophonist Michael Session, who led the band before him.

In an interview before the gig, Session recalled joining the band as a teen. “I’m 13 and my first gig with the Ark is with Azar Lawrence,” he exclaimed, referring to the noted saxophonist and sideman to Miles Davis, McCoy Tyner and Freddie Hubbard. “It’s actually a very humbling thing to be a medium, a conduit for the ancestors trying to spread this vibration as far and as hard as possible.”

The idea for the compilation arose shortly after the band’s 50th anniversary, which came and went without much fanfare. The collective vowed to not let that happen for its 60th. “We were like, ‘We’re going to make a product that will introduce a bunch of people to this band in a way that’s comprehensive and concise,” Session said. “This is for us, by us. We wanted to present something to the people from the band that can directly pay the band and support the band, and then be turned into other projects. It’s the first time the Ark has been able to do that, really.”

Renewed interest in Tapscott and the Arkestra dates back at least seven years, when a new crop of L.A. jazz musicians — including the bassist Thundercat, the saxophonist Kamasi Washington and the producer and multi-instrumentalist Terrace Martin — helped the superstar rapper Kendrick Lamar create his avant jazz-rap opus “To Pimp a Butterfly,” shedding light on the city’s still-fertile jazz scene. Since then, various labels have reissued Tapscott’s work. But the music on “60 Years,” remastered from old cassettes and CDs, hasn’t been heard beyond the Arkestra.

Six decades since Tapscott formed the band, Session said the group’s mission hasn’t changed, and he vowed to continue pushing forward. “I want to get weirder. I want to get back to how Horace did shows at prisons and high schools and colleges for free,” he said. “We could sell out Carnegie Hall and then come home and do the same set for 50, 60 cats. I want that balance. It sounds impossible, but we can do it.”

An earlier version of this article misstated the title of the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra’s compilation in one instance. It is “60 Years,” not “At 60.”

When we learn of a mistake, we acknowledge it with a correction. If you spot an error, please let us know at nytnews@nytimes.com.Learn more

"Little Africa"

(Composition, lyrics, and arrangement by Horace Tapscott)

https://www.moca.org/program/los-angeles-filmforum-at-moca-presents-horace-tapscott-musical-griot

MOCA

Museum of Contemporary Art Logo: Return to homepage

Barbara McCullough: Director HORACE TAPSCOTT: MUSICAL GRIOT, 16mm to HD, color, sound, 72 minutes, 2017.

Los Angeles Filmforum at MOCA Presents HORACE TAPSCOTT: MUSICAL GRIOT

In person: Barbara McCullough

Barbara McCullough’s poetic new film HORACE TAPSCOTT: MUSICAL GRIOT is a profound meditation on the importance of Black music, art, and activism to the history of Los Angeles. Horace Tapscott (1934–99) was an important but underappreciated jazz musician and community activist blacklisted in the 1960s because of his political affiliations. During the Watts Rebellion of 1965, the LAPD shut down Tapscott’s performances, claiming his music incited people to riot. McCullough’s film shares Tapscott’s story in the manner of a griot, or West African storyteller who maintains the oral history of a culture.

https://www.lafilmforum.org/archive/winter-2017/horace-tapscott-musical-griot/

Horace Tapscott was an underappreciated musical genius and community activist deeply involved in one the most exciting periods of Los Angeles jazz history. Black-listed in the 1960s and ‘70s because of his political affiliations (his “Arkestra” was the band of choice to perform at political rallies), during the Watts Rebellion of 1965, police actually shut down his performances, accusing him of inciting people to riot with his music. HORACE TAPSCOTT: MUSICAL GRIOT tells his story in the manner of a griot, or story-teller, who in West African societies maintain the legacy, knowledge, and history of their group traditions in oral form. McCullough will be present to introduce and discuss the film.

Biography:

A native of New Orleans, Barbara McCullough spent most of her life in the Los Angeles area. Before documentaries, experimental film and video were her first love as she strove to “tap the spirit and richness of her community by exposing its magic, touching its textures and trampling old stereotypes while revealing the untold stories reflective of African American life.” Her film and video projects include: Water Ritual #1: An Urban Rite of Purification, Shopping Bag Spirits and Freeway Fetishes: Reflection on Ritual Space, Fragments, and The World Saxophone Quartet. Her works are screened in museums and galleries nationally and internationally.

Acknowledgements:

Los Angeles Filmforum at MOCA is supported through both organizations by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Arts Commission. Additional support of Filmforum's screening series comes from Bloomberg Philanthropies and the Department of Cultural Affairs, City of Los Angeles. We also depend on our members, ticket buyers, and individual donors.

Los Angeles Filmforum at MOCA furthers MOCA’s mission to question and adapt to the changing definitions of art and to care for the urgency of contemporary expression with bimonthly screenings of film and video organized and co-presented by Los Angeles Filmforum—the city’s longest-running organization dedicated to weekly screenings of experimental film, documentaries, video art, and experimental animation.

For more on Los Angeles Filmforum, visit lafilmforum.org, or email lafilmforum@yahoo.com.

For more information on The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, visit moca.org.

16mm to HD, color, sound, 72 minutes, 2017.

Producer: Chephren Rasika

Editor: Scott Brock

Cinematography: Johnny Simmons, Al Santana, Charles Burnett, Bernard Nicola

Nearly four decades in the making, Barbara McCullough’s new documentary is a vivid recounting of the life and times of Horace Tapscott, musical genius, composer, community activist, and jazz mentor. Born in Houston, Tapscott migrated to Los Angeles where he attended Jefferson High School and there met his mentor, Professor Samuel Brown. Tapscott made a serious commitment to Brown that he would pass on whatever knowledge he received to help preserve the art form. At Jefferson, he also met fellow musicians who became well known later in life; in addition to Tapscott’s own voice, jazz icons Don Cherry and Arthur Blythe share their reflections on the richness of their music heritage. Though blacklisted for his political affiliations, Tapscott continued to create and play music that was both for his community and reflective of it. Choosing always to remain in Los Angeles, where he composed, performed, and shared his wisdom on music and life, he mentored three generations of accomplished jazz musicians. Beautifully photographed by many of McCullough’s colleagues in the celebrated Los Angeles Rebellion—including Charles Burnett, Julie Dash, and Billy Woodberry—the film paints a loving portrait of Tapscott and black Los Angeles while capturing remarkable performances by Tapscott with the Pan African Peoples Arkestra.

When: Thursday, March 9, 2017

7pm

Where:

250 South Grand Ave Los Angeles, CA 90012

https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/horace-tapscott-1934-1999/

Horace Tapscott (1934-1999)

Posted on November 24, 2007

by Peter Walton

BlackPast

Horace Tapscott

Pianist, bandleader, and social activist Horace Tapscott committed his life to the empowerment of his South Central Los Angeles community. Tapscott founded the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra and its umbrella organization, the Union of God’s Musicians and Artists Ascension (UGMAA), both of which were at the forefront of the vibrant community arts movement in black Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s.

Tapscott was born on April 6, 1934 in segregated Houston, Texas. His mother, Mary Malone Tapscott, was a professional singer and pianist. Seeking employment opportunities in the California shipyards, Tapscott’s family moved to Los Angeles in 1943. Tapscott spent his childhood learning piano and trombone, immersed in the richly diverse Central Avenue night club scene. After attending Jefferson High School and, later, Los Angeles City College, Tapscott served in the US Air Force, playing trombone in a service band. Upon his discharge, Tapscott returned to Los Angeles to find that the LAPD, operating under Chief William H. Parker, had dismantled the Central Avenue arts scene. While on tour with the Lionel Hampton orchestra in 1959, Tapscott determined to resettle in Los Angeles, hoping to reforge the communicative link between black artists and the community that had been lost on Central Avenue.

Tapscott envisioned an orchestra which could simultaneously preserve black culture, perform original music, and foster community involvement. With local musicians Tapscott formed the Underground Musicians Association (UGMA) in 1962, which then established the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra (Ark as in Noah’s– to serve as a life raft for black history and culture). Responding to a perceived disconnect between black Los Angeles and its rich African history, the Arkestra engaged the youth through musical instruction, revised history courses, and remedial reading and math classes. The Arkestra frequently performed in public schools, parks, community centers, churches, hospitals, and prisons – places it felt its message was needed.

Although the Arkestra played in support of diverse political groups, internally it stressed only the importance of self-expression. The Arkestra did, however, develop a key relationship with the Black Panther Party. Tapscott and Elaine Brown composed “The Meeting,” which became the Panthers’ anthem, and the Arkestra performed original musical arrangements to back Elaine Brown on her albums Seize the Time (1969) and Elaine Brown (1973).

In 1975 Tapscott institutionalized the UGMAA as a nonprofit organization. This allowed the foundation to pursue grants and other forms of financial support, while also expanding its social programs. The Arkestra’s free breakfast program continued while free arts classes ranging from drama to music theory to painting and poetry were offered to the community.

Until his death from lung cancer in 1999, Tapscott continued to encourage any community member with an artistic spirit to perform in the Arkestra, embracing poets, dancers, and even improvisational martial artists. It was Tapscott’s hope that a positive experience in the arts would extend to other areas of life, and that these positive experiences would bind the community together.

Horace Tapscott with the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra and the Great Voice of UGMAA: Why Don’t You Listen? Live at LACMA, 1998 (Dark Tree)

A review of the live album from a 1998 performance from the late pianist/composer/bandleader

September 11, 2019

JazzTimes

The cover of Why Don’t You Listen? Live at LACMA, 1998 by Horace Tapscott with the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra and the Great Voice of UGMAA

Yes, Horace Tapscott’s work was largely a holdover from the days of the Black Consciousness movement. (Its resolute mix of modal, spiritual, avant-garde, and Afro-jazz might have fit well on Strata-East Records if Tapscott hadn’t been in L.A., about as westerly as it gets.) Yet if anything, the pianist, composer, and bandleader’s music and message—they’re inextricable—have only become more urgent in the 20 years since his death. Why Don’t You Listen?, a live performance at the Los Angeles County Museum of Arts from July 1998, is as fresh and vital as if it were made yesterday.

Tapscott would be dead seven months later, of the lung cancer that was already ravaging his body this night at the museum. It didn’t impede his inventiveness or momentum, let alone that of the 10-piece version of his Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra or 12-voice Great Voice of UGMAA choir. They thoroughly recompose Ellington’s “Caravan” as an Afrobeat incantation. Dwight Trible’s shouting lead vocal is matched in intensity by a screaming alto saxophone solo from Michael Session—but it’s the rhythmic troika of drummer Donald Dean, conguero Najite Agindotan, and percussionist Bill Madison who hold the steady rolling sway. They’re even more firmly in command (though they share duties with another, bass-playing trio: Alan Hines, Trevor Ware, and Louis Large) on “Fela Fela,” then a brand-new tribute to the recently deceased Fela Kuti, with a harder-accented groove that carries the choir’s joyful Yoruba singing.

The museum’s visitors don’t seem particularly attentive; their audible chatter makes Tapscott’s “Why Don’t You Listen?” seem particularly on-the-nose. Perhaps frustration fuels that song’s especially fiery performance, with Tapscott’s piano percolating even more than Agindotan’s congas and the choir rising to a howl at the midpoint (interpolated by a melancholy solo vocal from Carolyn Whitaker). By its close, the audience responds fervently; you will too.

Check the price of Why Don’t You Listen? Live at LACMA, 1998 on Amazon!

Are you a musician or jazz enthusiast? Sign up for our weekly newsletter, full of reviews, profiles and more!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Michael J. West is a jazz journalist in Washington, D.C. In addition to his work on the national and international jazz scenes, he has been covering D.C.’s local jazz community since 2009. He is also a freelance writer, editor, and proofreader, and as such spends most days either hunkered down at a screen or inside his very big headphones. He lives in Washington with his wife and two children.

Tapscott Trailer for PanAfricaFF:

HORACE TAPSCOTT MUSICAL GRIOT documents the life of the late musical genius and community activist, Horace Tapscott, who was blacklisted in the 1960’s and 70’s because of his political affiliations. Mr. Tapscott is the storyteller, the griot whose life and words chronicle the development of jazz in Los Angeles. He is a cultural icon who promised his teacher and mentor to give back to the community what he learned. In fulfilling his commitment, Mr. Tapscott mentored to three generations of accomplished jazz musicians and later toured nationally and internationally sharing his talents before passing on to the “celestial arkestra” in 1999.

Originally shot in 16mm film from 1977 to 1991, the film was edited as HD BluRay and DVD. Total running time: 72minutes

Horace Tapscott & The Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra

Horace Tapscott & The Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra Live At I.U.C.C. (1979) [Full Album]

Nimbus West Records

NIMBUS No. 357

https://www.discogs.com/release/1769859

Recorded live in February to June 1979 at the Imannuel United Church of Christ, 85th and Holmes, Los Angeles

A Macrame 00:00 B1 Future 20:39 B2 Niossessprahs 31:57 C Village Dance 48:24 D1 L.T.T. 1:14:48 D2 Desert Fairy Princess 1:29:46 D3 Lift Every Voice 1:41:03 Baritone Saxophone – John Williams (tracks: B1 to D2) Bass – Alan Hines (tracks: A to D2) Roberto Miranda (tracks: B1 to D1) Drums – Billy Hinton (tracks: B1 to D1) Engineer [Recording Engineer] – Bruce Bidlack Flute – Adele Sebastian (tracks: B1 to D2), Aubrey Hart (tracks: B1 to D1) Liner Notes – Ron Pelletier Percussion – Daa'oud Woods (tracks: B1 to D2) Photography – Michael Pruessner Piano, Co-producer – Horace Tapscott (tracks: A, B1, C, D1, D2)

Producer – Tom Albach Soprano Saxophone – Billy Harris (tracks: B1 to D1) Tenor Saxophone – Sabia Matteen (tracks: A to D2) Trombone – Lester Robertson (tracks: B1 to D2)

Horace Tapscott – Songs Of The Unsung

Piano, Producer – Horace Tapscott A1 Song Of The Unsung 3:39 A2 Blue Essence 3:51 A3 Bakai 5:55 A4 In Times Like These 7:01 B1 Mary On Sunday 3:22 B2 Lush Life 6:34 B3 The Goat And Ram Jam 5:01 B4 Something For Kenny 5:58 Recorded - February 18, 1978 at United/Western Studios in Hollywood, California

Horace Tapscott " The Call ":

Horace Tapscott Conducting The Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra - The Call (1978) FULL ALBUM

VINYL RIP / Nimbus West Records – NIMBUS 246 (US, 1978)

https://www.discogs.com/Horace-Tapsco...

00:00 A1. The Call

08:25 A2. Quagmire Manor At Five A.M.

18:57 B1. Nakatini Suite

28:05 B2. Peyote Song No. III Recorded

April 8, 1978 Los Angeles, California.

The second LP by Horace Tapscott's Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra (a

16-piece trumpet-less big band) has four lengthy selections; three

originals by bandmembers plus Cal Massey's "Nakatini Suite". Best-known

among the sidemen are veteran Red Callender (doubling on tuba and bass)

and the powerful altoist Michael Session. Many of the other players

(including the pianist-leader) have some space to stretch out and the

ensembles (with their unusual voicings and free spots) are quite

colorful. Personnel:

Alto Clarinet – Herbert Callies

Alto Saxophone – Michael Session

Bass – David Bryant, Kamonta Lawrence Polk

Cello, Bass – Louis Spears

Conductor, Piano – Horace Tapscott

Drums – Everett Brown Jr.

Flute, Soprano Saxophone – Kafi Larry Roberts

Leader, Soprano Saxophone, Tenor Saxophone, Flute [Bamboo] – Jesse Sharps

Percussion, Drums – William Madison

Piano – Linda Hill Producer and Piano – Horace Tapscott Tom Albach

--Tenor Saxophone, Bass Clarinet

James Andrews

Trombone

Archie Johnson, Lester Robertson

Tuba, Bass – Red Callendar Vocals, Flute – Adele Sebastian

Horace Tapscott Piano Solo 1991

Horace Tapscott - The Dark Tree 1 & 2 (1999)

Horace Tapscott - The Dark Tree 1 & 2 (1999) [compilation]

Tracklist:

1.1 The Dark Tree 0:00

1.2 Sketches of Drunken Mary 20:56

1.3 Lino's Pad 32:28

1.4 One for Lately 49:13

2.1 Sandy and Niles 59:35

2.2 Bavarian Mist 1:10:54

2.3 The Dark Tree 2 1:24:09

2.4 A Dress for Renee 1:42:40

2.5 Nyja's Theme 1:47:35 HORACE TAPSCOTT QUARTET:

Horace Tapscott – piano

John Carter – clarinet Cecil McBee – contrabass Andrew Cyrille – drums Recorded live at Catalina Bar & Grill, Hollywood on December 14-17, 1989 Compositions

by Horace Tapscott (tracks: 1-1 to 1-3, 2-1, 2-3 to 2-5), Michael

Session (tracks: 2-2), Thurman Green (tracks: 1-4)

Horace Tapscott - Akirfa

Horace Tapscott - Akirfa

from the 1979 album In New York

Horace Tapscott - Macrame

Horace Tapscott - "Macrame"

Horace Tapscott With The Pan Afrikan Peoples-Desert Fairy

Horace Tapscott With Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra "Desert Fairy Princess"

Horace Tapscott: Musical Griot—LA Filmforum

LA Filmforum March 9, 2017

Q & A with Barbara McCullough at MoCA

"Horace Tapscott: Musical Griot":

Horace Tapscott: Musical Griot—LA Filmforum March 9, 2017

Horace Tapscott - 1993-09-12, Petrillo Music Shell, Grant Park, Chicago, IL:

Horace Tapscott with The Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra

15th Annual Chicago Jazz Festival

Petrillo Music Shell, Grant Park, Chicago, IL

1993-09-12 - FM 01. Introduction by Arthur Hoyle - 0:00 02. One for Lately - 2:20 03. Band introduction 23:33 04. The Black Apostles - 25:26 05. Song introduction - 37:38 06. Sandy and Niles - 39:01 07. Tapscott interview with Neil Tesser (incomplete) - 45:55 HORACE TAPSCOTT ARKESTRA:

Horace Tapscott - piano Arthur Blythe - alto sax Teddy Edwards - tenor sax Michael Session - baritone sax Oscar Brasheer - trumpet Thurman Green - trombone Roberto Miranda - bass Fritz Wise - drumsHorace Tapscott - Aiee! The Phantom

Horace Tapscott - "Aiee! The Phantom"

Horace Tapscott – Aiee! the Phantom Record Label: Arabesque Jazz Release Date: 1995 Style(s): Modal Horace Tapscott - Piano Marcus Belgrave - Trumpet Abraham Burton - Alto Sax Reggie Workman - Bass

Andrew Cyrille - Drums

Horace Tapscott - Mothership

Horace Tapscott - "Mothership"

Horace Tapscott – "Aiee! the Phantom"

Record Label: Arabesque Jazz

Release Date: 1995

Style(s): Modal Horace Tapscott - Piano Marcus Belgrave - Trumpet Abraham Burton - Alto Sax

Reggie Workman - Bass

Andrew Cyrille - Drums

Horace Tapscott Quintet USA, 1969

The Giant is Awakened ...

Horace Tapscott - The Giant Is Awakened (full album)

00:00 - The Giant Is Awakened

17:27 - For Fats

19:51 - The Dark Tree

26:55 - Niger's Theme

Horace Tapscott - piano

Arthur Blythe - alto saxophone

David Bryant, Walter Savage Jr. - bass

Everett Brown Jr. - drums

Flying Dutchman Records, 1969

Track listing:

All compositions by Horace Tapscott except as noted:

- "The Giant Is Awakened" - 17:23

- "For Fats" (Arthur Blythe) - 2:20

- "The Dark Tree" - 7:01

- "Niger's Theme" - 11:55

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Giant_Is_Awakened

The Giant is Awakened is the debut album by American jazz pianist/composer Horace Tapscott recorded in 1969 and released on the Flying Dutchman label.[1][2][3]

AllMusic awarded the album 4½ stars.[4] The Chicago Reader

noted "Tapscott was leery of the music business in general, and of this

deal in particular—and considering a promise that he'd be involved in

the mixing process was subsequently broken, his skepticism was

prescient. He didn't record again for another decade, and then only for

small independents like Nimbus and Interplay. In any case, as listeners,

we should be grateful Tapscott agreed to make The Giant at all".[6]

Lloyd Sachs, writing for DownBeat,

called the album "A sometimes hypnotic, sometimes starkly expressive

reflection of those fractious times," and commented: "With its swooshing

effects and two bassists... the album is ahead of its time. To the

great disappointment of those who thrilled at this music, Tapscott

didn't make another recording for 10 years. But Giant is as enrapturing now as it was then."[5]

Horace Tapscott " Peyote Song No. III

Horace Tapscott " Peyote Song No. III "

From " The Call " 1978 Nimbus recording label. Horace Tapscott piano Jesse Sharps soprano and tenor saxophones, flute Linda Hill piano Adele Sebastian vocal, flute Lester Robertson trombone David Bryant bass Everett Brown, Jr. drums Herbert Callies alto clarinet James Andrews tenor saxophone, bass clarinet Michael Session alto saxophone Kafi Larry Roberts flute, soprano saxophone Archie Johnson trombone Red Callendar tuba, bass William Madison percussions, drums Louis Spears cello, bass Kamonta Lawrence Polk bass

Horace Tapscott - To the Great House

Horace Tapscott - "To the Great House"

(Composition and arrangement by Horace Tapscott):

Horace Tapscott – Aiee! the Phantom Record Label: Arabesque Jazz

Release Date: 1995 ▪ Style(s): Modal Horace Tapscott - Piano Marcus Belgrave - Trumpet Abraham Burton - Alto Sax Reggie Workman - Bass Andrew Cyrille - Drums

Horace Tapscott - If You Could See Me Now

Horace Tapscott - "If You Could See Me Now":

From the 1979 album 'In New York'

Horace Tapscott - Sketches Of Drunken Mary

Horace Tapscott - "Sketches Of Drunken Mary":

From the 1979 album 'In New York'

Horace Tapscott " The Call ":

Horace Tapscott Conducting The Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra - The Call (1978) FULL ALBUM

VINYL RIP / Nimbus West Records – NIMBUS 246 (US, 1978) https://www.discogs.com/Horace-Tapsco... 00:00Horace Tapscott Piano Solo 1991

Horace Tapscott - The Dark Tree 1 & 2 (1999)

Horace Tapscott - The Dark Tree 1 & 2 (1999) [compilation]

Tracklist: 1.1 The Dark Tree 0:00 1.2 Sketches of Drunken Mary 20:56 1.3 Lino's Pad 32:28 1.4 One for Lately 49:13 2.1 Sandy and Niles 59:35 2.2 Bavarian Mist 1:10:54 2.3 The Dark Tree 2 1:24:09 2.4 A Dress for Renee 1:42:40 2.5 Nyja's Theme 1:47:35Horace Tapscott - Akirfa

Horace Tapscott - Akirfa

from the 1979 album In New York

Horace Tapscott - Macrame

Horace Tapscott - "Macrame"

Horace Tapscott With The Pan Afrikan Peoples-Desert Fairy

Horace Tapscott With Pan-Afrikan Peoples Arkestra "Desert Fairy Princess"

Horace Tapscott: Musical Griot—LA Filmforum

LA Filmforum March 9, 2017

Q & A with Barbara McCullough at MoCA

"Horace Tapscott: Musical Griot":

Horace Tapscott: Musical Griot—LA Filmforum March 9, 2017

Horace Tapscott - 1993-09-12, Petrillo Music Shell, Grant Park, Chicago, IL:

Horace Tapscott - Aiee! The Phantom

Horace Tapscott - "Aiee! The Phantom"

Horace Tapscott – Aiee! the PhantomHorace Tapscott - Mothership

Horace Tapscott - "Mothership"

Horace Tapscott – "Aiee! the Phantom"Horace Tapscott Quintet USA, 1969

The Giant is Awakened ...

Horace Tapscott - The Giant Is Awakened (full album)

00:00 - The Giant Is Awakened

17:27 - For Fats

19:51 - The Dark Tree

26:55 - Niger's Theme

Horace Tapscott - piano

Arthur Blythe - alto saxophone

David Bryant, Walter Savage Jr. - bass

Everett Brown Jr. - drums

Flying Dutchman Records, 1969

Track listing:

All compositions by Horace Tapscott except as noted:

- "The Giant Is Awakened" - 17:23

- "For Fats" (Arthur Blythe) - 2:20

- "The Dark Tree" - 7:01

- "Niger's Theme" - 11:55

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Giant_Is_Awakened

The Giant is Awakened is the debut album by American jazz pianist/composer Horace Tapscott recorded in 1969 and released on the Flying Dutchman label.[1][2][3]

AllMusic awarded the album 4½ stars.[4] The Chicago Reader noted "Tapscott was leery of the music business in general, and of this deal in particular—and considering a promise that he'd be involved in the mixing process was subsequently broken, his skepticism was prescient. He didn't record again for another decade, and then only for small independents like Nimbus and Interplay. In any case, as listeners, we should be grateful Tapscott agreed to make The Giant at all".[6]

Lloyd Sachs, writing for DownBeat, called the album "A sometimes hypnotic, sometimes starkly expressive reflection of those fractious times," and commented: "With its swooshing effects and two bassists... the album is ahead of its time. To the great disappointment of those who thrilled at this music, Tapscott didn't make another recording for 10 years. But Giant is as enrapturing now as it was then."[5]