AS OF JANUARY 13, 2023 FIVE HUNDRED MUSICAL ARTISTS HAVE BEEN FEATURED IN THE SOUND PROJECTIONS MAGAZINE THAT BEGAN ITS ONLINE PUBLICATION ON NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2017/01/odetta-holmes-1930-2008-legendary.html

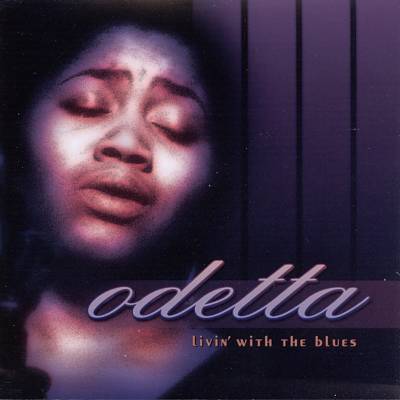

PHOTO: ODETTA HOLMES (1930-2008)

Odetta Holmes

(1930-2008)

Biography by Philip Van Vleck

One of the strongest voices in the folk revival and the civil rights movement, Odetta was born on New Year's Eve 1930 in Birmingham, AL. By the time she was six years old, she had moved with her younger sister and mother to Los Angeles. She showed a keen interest in music from the time she was a child, and when she was about ten years old, somewhere between church and school, her singing voice was discovered. Odetta's mother began saving money to pay for voice lessons for her, but was advised to wait until her daughter was 13 years old and well into puberty. Thanks to her mother, Odetta began voice lessons when she was 13. She received a classical training, which was interrupted when her mother could no longer afford to pay for the lessons. The puppeteer Harry Burnette interceded and paid for Odetta to continue her voice training.

When she was 19 years old, Odetta landed a role in the Los Angeles production of Finian's Rainbow, which was staged in the summer of 1949 at the Greek Theatre in Los Angeles. It was during the run of this show that she first heard the blues harmonica master Sonny Terry. The following summer, Odetta was again performing in summer stock in California. This time it was a production of Guys and Dolls, staged in San Francisco. Hanging out in North Beach during her days off, Odetta had her first experience with the growing local folk music scene. Following her summer in San Francisco, Odetta returned to Los Angeles, where she worked as a live-in housekeeper. During this time she performed on a show bill with Paul Robeson.

In 1953, Odetta took some time off from her housecleaning chores to travel to New York City and appear at the famed Blue Angel folk club. Pete Seeger and Harry Belafonte had both taken an interest in her career by this time, and her debut album, The Tin Angel, was released in 1954. From this time forward, Odetta worked to expand her repertoire and make full use of what she has always termed her "instrument." When she began singing, she was considered a coloratura soprano. As she matured, she became more of a mezzo-soprano. Her experience singing folk music led her to discover a vocal range that runs from coloratura to baritone.

Odetta's most productive decade as a recording artist came in the 1960s, when she released 16 albums, including Odetta at Carnegie Hall, Christmas Spirituals, Odetta and the Blues, It's a Mighty World, and Odetta Sings Dylan. In 1999 she released her first studio album in 14 years, Blues Everywhere I Go. On September 29, 1999, President Bill Clinton presented Odetta with the National Endowment for the Arts' Medal of the Arts, a fitting tribute to one of the great treasures of American music.

The next few years found Odetta releasing some new full-length albums, including Livin' with the Blues and a collection of Leadbelly tunes, Looking for a Home. She toured North America, Latvia, and Scotland and was mentioned in Martin Scorsese's 2005 documentary, No Direction Home. That same year Odetta released Gonna Let It Shine, which went on to receive a 2007 Grammy nomination for Best Traditional Folk Album. In December 2008, she died of heart disease in New York.

https://panopticonreview.blogspot.com/2008/12/odetta-revolutionary-artist-and-civil.html

FROM THE PANOPTICON REVIEW ARCHIVES

(Originally posted on December 3, 2008)

Wednesday, December 3, 2008

Odetta: Revolutionary Artist and Civil Rights Movement Icon, 1930-2008

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/03/arts/music/03odetta.html…

http://www.nytimes.com/packages/…/arts/20081203_odetta.html…

The Last Word: Odetta

Watch a full-length version of the video above, including an extended interview with the singer, whose voice was the soundtrack of the civil rights movement.

Last Word: Odetta

Odetta

became a force of the folk music revival in the 1950s. In the 1960s

her renditions of spirituals and blues became part of the soundtrack of

the civil rights movement.

Odetta, Voice of Civil Rights Movement, Dies at 77

All,

A cultural GIANT and a great artist died yesterday. Odetta was one of the true authentic icons of the Civil Rights Movement and a major influence on generations of socially conscious and engaged singers, songwriters, and activists. Her tremendous voice, stirring musical vision, and fierce committment to social, racial, and economic justice, as well as gender equality will be sorely missed. Her many and crucial contributions to the Movement were an inspiration and a clarion call for many to join and participate in the ongoing global struggle for Democracy and Peace. Her extraordinary legacy will never die so long as there are other artists and cultural workers to continue in her revolutionary path. Thank you Odetta and rest in peace sister...

Kofi

Odetta, the singer whose deep voice wove together the strongest songs of American folk music and the civil rights movement, died on Tuesday at Lenox Hill Hospital in Manhattan. She was 77.

Odetta became a force of the folk music revival in the 1950s. In the 1960s her renditions of spirituals and blues became part of the soundtrack of the civil rights movement.

The cause was heart disease, said her manager, Doug Yeager. He added that she had been hoping to sing at Barack Obama’s inauguration.

Odetta sang at coffeehouses and at Carnegie Hall, made highly influential recordings of blues and ballads, and became one of the most widely known folk-music artists of the 1950s and ’60s. She was a formative influence on dozens of artists, including Bob Dylan, Joan Baez and Janis Joplin.

Her voice was an accompaniment to the black-and-white images of the freedom marchers who walked the roads of Alabama and Mississippi and the boulevards of Washington in the quest to end racial discrimination.

Rosa Parks, the woman who started the boycott of segregated buses in Montgomery, Ala., was once asked which songs meant the most to her. She replied, “All of the songs Odetta sings.”

Odetta sang at the march on Washington, a pivotal event in the civil rights movement, in August 1963. Her song that day was “O Freedom,” dating to slavery days: “O freedom, O freedom, O freedom over me, And before I’d be a slave, I’d be buried in my grave, And go home to my Lord and be free.”

Odetta Holmes was born in Birmingham, Ala., on Dec. 31, 1930, in the depths of the Depression. The music of that time and place — particularly prison songs and work songs recorded in the fields of the Deep South — shaped her life.

“They were liberation songs,” she said in a videotaped interview with The New York Times in 2007 for its online feature “The Last Word.” “You’re walking down life’s road, society’s foot is on your throat, every which way you turn you can’t get from under that foot. And you reach a fork in the road and you can either lie down and die, or insist upon your life.”

Her father, Reuben Holmes, died when she was young, and in 1937 she and her mother, Flora Sanders, moved to Los Angeles. Three years later, Odetta discovered that she could sing.

“A teacher told my mother that I had a voice, that maybe I should study,” she recalled. “But I myself didn’t have anything to measure it by.”

She found her own voice by listening to blues, jazz and folk music from the African-American and Anglo-American traditions. She earned a music degree from Los Angeles City College. Her training in classical music and musical theater was “a nice exercise, but it had nothing to do with my life,” she said.

“The folk songs were — the anger,” she emphasized.

In a 2005 National Public Radio interview, she said: “School taught me how to count and taught me how to put a sentence together. But as far as the human spirit goes, I learned through folk music.”

In 1950, Odetta began singing professionally in a West Coast production of the musical “Finian’s Rainbow,” but she found a stronger calling in the bohemian coffeehouses of San Francisco. “We would finish our play, we’d go to the joint, and people would sit around playing guitars and singing songs and it felt like home,” she said.

She began singing in nightclubs, cutting a striking figure with her guitar and her close-cropped hair.

Her voice plunged deep and soared high, and her songs blended the personal and the political, the theatrical and the spiritual. Her first solo album, “Odetta Sings Ballads and Blues,” resonated with an audience hearing old songs made new.

Bob Dylan, referring to that recording, said in a 1978 interview, “The first thing that turned me on to folk singing was Odetta.” He said he heard something “vital and personal,” and added, “I learned all the songs on that record.” It was her first, and the songs were “Mule Skinner,” “Jack of Diamonds,” “Water Boy,” “ ’Buked and Scorned.”

Her blues and spirituals led directly to her work for the civil rights movement. They were two rivers running together, she said in her interview with The Times. The words and music captured “the fury and frustration that I had growing up.”

Her fame hit a peak in 1963, when she marched with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and performed for President John F. Kennedy. But after King was assassinated in 1968, the wind went out of the sails of the civil rights movement and the songs of protest and resistance that had been the movement’s soundtrack. Odetta’s fame flagged for years thereafter.

In 1999 President Bill Clinton awarded Odetta the National Endowment for the Arts Medal of the Arts and Humanities.

Odetta was married three times: to Don Gordon, to Gary Shead, and, in 1977, to the blues musician Iverson Minter, known professionally as Louisiana Red. The first two marriages ended in divorce; Mr. Minter moved to Germany in 1983 to pursue his performing career.

She was singing and performing well into the 21st century, and her influence stayed strong.

In April 2007, half a century after Bob Dylan first heard her, she was on stage at a Carnegie Hall tribute to Bruce Springsteen. She turned one of his songs, “57 Channels,” into a chanted poem, and Mr. Springsteen came out from the wings to call it “the greatest version” of the song he had ever heard.

Reviewing a December 2006 performance, James Reed of The Boston Globe wrote: “Odetta’s voice is still a force of nature — something commented upon endlessly as folks exited the auditorium — and her phrasing and sensibility for a song have grown more complex and shaded.”

The critic called her “a majestic figure in American music, a direct gateway to bygone generations that feel so foreign today.”

Posted by Kofi Natambu at 1:29 PM

Labels: Civil Rights Movement, Folk music, Odetta, Revolutionary art, Musical genres, blues history, African American culture

http://www.biography.com/people/odetta-507480

Odetta

(1930-2008)

Odetta Holmes, later known simply as Odetta, was born on December 31, 1930, in Birmingham, Alabama. Before she even learned how to play an instrument, Odetta banged on the family piano in hopes of making music—until her family members got headaches and told her to stop. Growing up in the Deep South during the Great Depression, Odetta fell in love with the work songs she heard people singing to ease the pain of the times. "They were liberation songs," she later recalled. "You're walking down life's road, society's foot is on your throat, every which way you turn you can't get from under that foot. And you reach a fork in the road and you can either lie down and die or insist upon your life ... those people who made up the songs were the ones who insisted upon life."

Odetta's father, Reuben Holmes, died when Odetta was a child. In 1937 she and her mother, Flora Sanders, moved across the country to Los Angeles. It was on the train to California that Odetta had her first significant experience with racism. "We were on the train when, at one point, a conductor came back and said that all the colored people had to move out of this car and into another one," she remembered. "That was my first big wound."

Although Odetta loved singing, she never considered whether she had any particular vocal talent until one of her grammar school teachers heard her voice. The teacher insisted to Odetta's mother that she sign her up for classical training. In junior high, after several years of voice coaching, she landed a spot in a prestigious signing group called the Madrigal Singers. When Odetta graduated from Belmont High School in Los Angeles, she continued on to Los Angeles City College to study music. She later insisted, however, that her real education came from outside the classroom. "School taught me how to count and taught me how to put a sentence together," she acknowledged. "But as far as the human spirit goes, I learned through folk music." And as far as her musical development went, Odetta said her formal training was "a nice exercise, but it had nothing to do with my life."

'Soundtrack of the Civil Rights Movement'

In 1950, after graduating from college with a degree in music, Odetta landed a role in the chorus of a traveling production of Finian's Rainbow. She fell in love with folk music when, after a show in San Francisco, she went to a Bohemian coffee shop and experienced a late-night folk music session. "That night I heard hours and hours of songs that really touched where I live," she said. "I borrowed a guitar and learned three chords, and started to sing at parties." Later that year, she left the theater company and took a job singing at a San Francisco folk club. In 1953, she moved to New York City and soon became a fixture at Manhattan's famed Blue Angel nightclub. "As I did those songs, I could work on my hate and fury without being antisocial," she said. "Through those songs, I learned things about the history of black people in this country that the historians in school had not been willing to tell us about or had lied about."

She recorded her first solo album, Odetta Sings Ballads and Blues, in 1956, and it became an instant classic in American folk music. Bob Dylan later cited that album as the record that first turned him on to folk music, and Time magazine raved about "the meticulous care with which she tried to recreate the feeling of her folk songs." Odetta quickly followed with two more highly acclaimed folk albums: At the Gate of Horn (1957) and My Eyes Have Seen (1959). In 1960, Odetta delivered a famed concert at Carnegie Hall and released a live recording of the performance.

The 1960s, however, were Odetta's most prolific years. During that decade, she lent her powerful voice to the cause of black equality—so often so that her music has frequently been called the "soundtrack of the Civil Rights Movement." She performed at political rallies, demonstrations and benefits. In 1963, during the March on Washington, Odetta gave the most iconic performance of her life: Singing from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial after an introduction by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Odetta also recorded more than a dozen albums during the 1960s, most notably Odetta and the Blues, One Grain of Sand, It's a Mighty World and Odetta Sings Dylan.

Later Career

Odetta's popularity waned after the 1960s, and she recorded only several more albums over the remaining four decades of her life. Her most prominent later works include Movin' It On (1987), Blues Everywhere I Go (1999) and Looking for a Home (2001). One of the greatest American folk singers of all time, Odetta has been cited as a prominent influence by such legendary musicians as Bob Dylan, Joan Baez and Janis Joplin. President Bill Clinton presented her with a National Medal of Arts in 1999. In 2004, she was made a Kennedy Center honoree and in 2005, the Library of Congress awarded her its Living Legend Award. Her highly acclaimed final album, a live recording performed when she was 74 years old, was entitled Gonna Let It Shine (2005). Her music inspired a generation of civil rights activists who helped tear down the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow to build a more equal and just United States of America. In her later years, after the popularity of folk music had declined, Odetta made it her mission to share its potency with a new generation of youth. "The folk repertoire is our inheritance. Don't have to like it, but we need to hear it," she said. "I love getting to schools and telling kids there's something else out there. It's from their forebears, and it's an alternative to what they hear on the radio. As long as I am performing, I will be pointing out that heritage that is ours."

Odetta continued performing right up until almost the day of her death on December 2, 2008, at the age of 77. She had dreamed of performing at the inauguration of President Barack Obama, but tragically passed away just weeks before he took office.

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2008/dec/04/odetta-film-folk-music-obituary

Odetta

Her gap-toothed smile and commanding, yet warm, stage presence marked her out as an outstanding live entertainer, and one of the first black women to attract a large white audience. Odetta, who has died of kidney failure aged 77, received many honours during her life, most notably by Martin Luther King, who called her "the queen of American folk music", and the then president Bill Clinton, who in 1999 awarded her the National Medal of the Arts and Humanities. She had been due to sing at Barack Obama's inauguration in January.

Odetta was born in Birmingham, Alabama, to Reuben Holmes, a steel-mill worker, and his wife, Flora, a maid. Her father died when Odetta was a toddler. Her mother then remarried, to Zadock Felious, and the family moved to Los Angeles. Although she took her stepfather's surname, as a performer Odetta always used only her first name. Her parents played her jazz and classical music, her mother enrolling her in opera lessons when she was 13. On leaving high school, she went to work as a maid, while studying classical music and musical comedy at night school. She first sang professionally in Los Angeles in 1944, began to get work in musical theatre, and in 1949 sang in the touring production of Finian's Rainbow. In 1950 she was cast in a production of Guys and Dolls.

While performing in San Francisco with the show, Odetta became aware of the nascent folk music movement, and, having bought a guitar, tentatively began to perform. Woody Guthrie's protege Ramblin' Jack Elliott helped her get a booking in a folk club, and she soon won a residency and a loyal audience.

Returning to Los Angeles, she again worked as a maid while pursuing work as a singer. Around this time she developed a mix of folk, spirituals and blues that would change little across the following decades. "In school, you learn about American history through battles," she told the New York Times in 1981. "But I learned about the United States through this music, through the songs that I sing."

In 1953 she performed at the Blue Angel folk club in New York. There she met Pete Seeger and Harry Belafonte, who both began to champion her work. The following year, the San Francisco jazz label Fantasy Records released Odetta & Larry, an album shared with the folk singer Larry Mohr. Odetta's debut solo album, Odetta Sings Ballads and Blues, was released in 1956 by Tradition Records. Her 1957 album At the Horn was later cited by Bob Dylan as the recording that spurred him to play folk music.

In 1959 Belafonte included Odetta on his television special, helping her to win a wide audience. She signed with New York's Vanguard Records and released albums regularly, three in 1960 alone. In 1961 she sang with Belafonte on There's a Hole in the Bucket, a minor hit in the UK. She acted in the films Sanctuary (1961) and The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (1974).

Harry Belafonte & Odetta - A Hole in the Bucket (Live)

Odetta's afro hairstyle and pride in her African features made her a role model for many black Americans. She identified with the civil rights movement and sang at the March on Washington on August 28 1963, performed for President John F Kennedy at a civil rights presentation and marched with King from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama.

Her studio recordings often possessed a somewhat stilted atmosphere, but in concert she came into her own. Her live albums, Odetta at Carnegie Hall (1960) and Odetta at Town Hall (1962), captured her varied repertoire and strong, soulful persona. Yet, as popular music changed during the 1960s, she came to be regarded as old-fashioned. Her reliance on traditional material meant that she was overtaken by a new wave of folk-inspired singer-songwriters while her mezzo-soprano vocal appeared too formal compared with with the gospel/blues-derived voices then favoured in black music.

Although Odetta continued to perform, recording occasionally, her achievements were largely forgotten. In 1988 she signed up with a new manager, Doug Yeager, who immediately raised her profile, and she began recording and touring again, often playing the UK. Martin Scorsese's Bob Dylan documentary No Direction Home (2005) included a clip of her appearance on Tonight With Belafonte in 1959. Her 2007 album Gonna Let It Shine was nominated for the best traditional folk album Grammy. Earlier this year, she launched a US tour, performing from a wheelchair and campaigning for Obama from the stage.

She was married and divorced three times, to Don Gordon, Gary Shead and the blues musician Iverson Minter (Louisiana Red). She is survived by her adopted daughter Michelle Esrick.

• Odetta Holmes Felious, singer and actor, born December 31 1930; died December 2, 2008

· This article was amended on Friday December 5 2008. Odetta's duet with Harry Belafonte was called "There's a Hole in the Bucket", not "My Bucket's got a Hole in it", as we said originally. This has been corrected.

http://www.colorlines.com/articles/odetta-voice-civil-rights-movement-1930-2008

Odetta

"The Voice of the Civil Rights Movement" (1930-2008)

by Jonathan Adams

December 3, 2008

Colorlines

Odetta,

most famous for singing at the March on Washington in 1963, will not be

able to perform as she intended at Barack Obama's inauguration next

month. The woman, known as "the voice of the Civil Rights Movement,"

became famous among musicians like Joan Baez and Bob Dylan but did not

consider herself a folk singer.

"I'm

not a real folk singer," she told The Washington Post in 1983. "I don't

mind people calling me that, but I'm a musical historian. I'm a city

kid who has admired an area and who got into it. I've been fortunate.

With folk music, I can do my teaching and preaching, my propagandizing."

In The Washington Post interview, Odetta theorized that humans

developed music and dance because of fear, "fear of God, fear that the

sun would not come back, many things. I think it developed as a way of

worship or to appease something. ... The world hasn't improved, and so

there's always something to sing about."[Associated Press]

Odetta died Tuesday after battling heart disease. She was 77.

[Publication date: April 14, 2020]

The first in-depth biography of the legendary singer and “Voice of the Civil Rights Movement,” who combatted racism and prejudice through her music.

Odetta channeled her anger and despair into some of the most powerful folk music the world has ever heard. Through her lyrics and iconic persona, Odetta made lasting political, social, and cultural change.

A leader of the 1960s folk revival, Odetta is one of the most important singers of the last hundred years. Her music has influenced a huge number of artists over many decades, including Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, the Kinks, Jewel, and, more recently, Rhiannon Giddens and Miley Cyrus.

But Odetta’s importance extends far beyond music. Journalist Ian Zack follows Odetta from her beginnings in deeply segregated Birmingham, Alabama, to stardom in San Francisco and New York. Odetta used her fame to bring attention to the civil rights movement, working alongside Joan Baez, Harry Belafonte, and other artists. Her opera-trained voice echoed at the 1963 March on Washington and the Selma to Montgomery march, and she arranged a tour throughout the deeply segregated South. Her “Freedom Trilogy” songs became rallying cries for protesters everywhere.

Through interviews with Joan Baez, Harry Belafonte, Judy Collins, Carly Simon, and many others, Zack brings Odetta back into the spotlight, reminding the world of the folk music that powered the civil rights movement and continues to influence generations of musicians today.

Listen to the author’s top five Odetta hits while you read:

Access the playlist here: https://spoti.fi/3c2HnF4

REVIEWS:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Ian Zack has been a writer and editor for two decades. His writing has appeared in the New York Times, Forbes, and Acoustic Guitar. Zack’s award-winning first book, Say No to the Devil: The Life & Musical Genius of Rev. Gary Davis, was called “magisterial” by the Wall Street Journal.

Odetta Speaks About Her Life As An Activist:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Odetta

Odetta

Odetta Holmes (December 31, 1930 – December 2, 2008),[1][2] known as Odetta, was an American singer, actress, guitarist, lyricist, and civil rights activist, often referred to as "The Voice of the Civil Rights Movement".[3] Her musical repertoire consisted largely of American folk music, blues, jazz, and spirituals. An important figure in the American folk music revival of the 1950s and 1960s, she influenced many of the key figures of the folk-revival of that time, including Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Mavis Staples, and Janis Joplin. In 2011 Time magazine included her recording of "Take This Hammer" on its list of the 100 Greatest Popular Songs, stating that "Rosa Parks was her No. 1 fan, and Martin Luther King Jr. called her the queen of American folk music."[4]

Biography

Early life and career

Odetta was born Odetta Holmes in Birmingham, Alabama, United States.[1] Her father, Reuben Holmes, had died when she was young, and in 1937 she and her mother, Flora Sanders, moved to Los Angeles. When Flora remarried a man called Zadock Felious, Odetta took her stepfather's last name.[5] In 1940 Odetta's teacher noticed her vocal talents, “A teacher told my mother that I had a voice, that maybe I should study,” she recalled. “But I myself didn’t have anything to measure it by.”[6] She began operatic training at the age of thirteen. After attending Belmont High School, she studied music at Los Angeles City College supporting herself as a domestic worker. Flora had hoped to see her daughter follow in the footsteps of Marian Anderson, but Odetta doubted a large black girl like herself would ever perform at the Metropolitan Opera.[7] In 1944 she made her professional debut in musical theater as an ensemble member for four years with the Hollywood Turnabout Puppet Theatre, working alongside Elsa Lanchester. In 1949, she joined the national touring company of the musical Finian's Rainbow.

While on tour with Finian's Rainbow, Odetta "fell in with an enthusiastic group of young balladeers in San Francisco", and after 1950 she concentrated on folk singing.[8]

She made her name playing at the Blue Angel nightclub in New York City, and the hungry i in San Francisco. At Tin Angel also in San Francisco in 1953 and 1954, Odetta recorded the album Odetta and Larry with Larry Mohr for Fantasy Records.[9]

A solo career followed, with Odetta Sings Ballads and Blues (1956) and At the Gate of Horn (1957). Odetta Sings Folk Songs was one of the best-selling folk albums of 1963.

In 1959 she appeared on Tonight with Belafonte, a nationally televised special. She sang "Water Boy" and a duet with Belafonte, "There's a Hole in My Bucket".[10]

In 1961, Martin Luther King Jr. called her "The Queen of American Folk Music".[11] Also in 1961, the duo Harry Belafonte and Odetta made number 32 in the UK Singles Chart with the song "There's a Hole in the Bucket".[12] She is remembered for her performance at March on Washington, the 1963 civil rights demonstration, at which she sang "O Freedom".[13] She described her role in the civil rights movement as "one of the privates in a very big army".[14]

Broadening her musical scope, Odetta used band arrangements on several albums rather than playing alone. She released music of a more "jazz" style on albums like Odetta and the Blues (1962) and Odetta (1967). She gave a remarkable performance in 1968 at the Woody Guthrie memorial concert.[15]

Odetta acted in several films during this period, including Cinerama Holiday (1955); a cinematic production of William Faulkner's Sanctuary (1961); and The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (1974). In 1961 she appeared in an episode of the TV series Have Gun, Will Travel, playing the wife of a man sentenced to hang ("The Hanging of Aaron Gibbs").

She was married twice, first to Dan Gordon and then, after their divorce, to Gary Shead. Her second marriage also ended in divorce. The blues singer-guitarist Louisiana Red was a former companion of hers.[7]

Later career

In May 1975 she appeared on public television's Say Brother program, performing "Give Me Your Hand" in the studio. She spoke about her spirituality, the music tradition from which she drew, and her involvement in civil rights struggles.[16]

In 1976, Odetta performed in the U.S. Bicentennial opera Be Glad Then, America by John La Montaine, as the Muse for America; with Donald Gramm, Richard Lewis and the Penn State University Choir and the Pittsburgh Symphony. The production was directed by Sarah Caldwell who was the director of the Opera Company of Boston at the time.

In 1982, Odetta was an artist-in-residence at the Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington. [17]

Odetta released two albums in the 20-year period from 1977 to 1997: Movin' It On, in 1987 and a new version of Christmas Spirituals, produced by Rachel Faro, in 1988.

Beginning in 1998, she returned to recording and touring. The new CD To Ella (recorded live and dedicated to her friend Ella Fitzgerald upon hearing of her death before walking on stage),[18] was released in 1998 on Silverwolf Records, followed by three releases on M.C. Records in partnership with pianist/arranger/producer Seth Farber and record producer Mark Carpentieri. These included Blues Everywhere I Go, a 2000 Grammy-nominated blues/jazz band tribute album to the great lady blues singers of the 1920s and 1930s; Looking for a Home, a 2002 W.C. Handy Award-nominated band tribute to Lead Belly; and the 2007 Grammy-nominated Gonna Let It Shine, a live album of gospel and spiritual songs supported by Seth Farber and The Holmes Brothers. These recordings and active touring led to guest appearance on fourteen new albums by other artists between 1999 and 2006 and the re-release of 45 old Odetta albums and compilation appearances.

On September 29, 1999, President Bill Clinton presented Odetta with the National Endowment for the Arts' National Medal of Arts. In 2004, Odetta was honored at the Kennedy Center with the "Visionary Award" along with a tribute performance by Tracy Chapman. In 2005, the Library of Congress honored her with its "Living Legend Award".

In mid-September 2001, Odetta performed with the Boys' Choir of Harlem on the Late Show with David Letterman, appearing on the first show after Letterman resumed broadcasting, having been off the air for several nights following the events of September 11; they performed "This Little Light of Mine".

The 2005 documentary film No Direction Home, directed by Martin Scorsese, highlights her musical influence on Bob Dylan, the subject of the documentary. The film contains an archive clip of Odetta performing "Waterboy" on TV in 1959, as well as her "Mule Skinner Blues" and "No More Auction Block for Me".

In 2006, Odetta opened shows for jazz vocalist Madeleine Peyroux, and in 2006 she toured the U.S., Canada, and Europe accompanied by her pianist, which included being presented by the U.S. Embassy in Latvia as the keynote speaker at a human rights conference, and also in a concert in Riga's historic 1,000-year-old Maza Guild Hall. In December 2006, the Winnipeg Folk Festival honored Odetta with their "Lifetime Achievement Award". In February 2007, the International Folk Alliance awarded Odetta as "Traditional Folk Artist of the Year".

On March 24, 2007, a tribute concert to Odetta was presented at the Rachel Schlesinger Theatre by the World Folk Music Association with live performance and video tributes by Pete Seeger, Madeleine Peyroux, Harry Belafonte, Janis Ian, Sweet Honey in the Rock, Josh White Jr., Peter, Paul and Mary, Oscar Brand, Tom Rush, Jesse Winchester, Eric Andersen, Wavy Gravy, David Amram, Roger McGuinn, Robert Sims, Carolyn Hester, Donal Leace, Marie Knight, Side by Side, and Laura McGhee.[19]

In 2007, Odetta's album Gonna Let It Shine was nominated for a Grammy, and she completed a major Fall Concert Tour in the "Songs of Spirit" show, which included artists from all over the world. She toured around North America in late 2006 and early 2007 to support this CD.[20]

Final tour

On January 21, 2008, Odetta was the keynote speaker at San Diego's Martin Luther King Jr. commemoration, followed by concert performances in San Diego, Santa Barbara, Santa Monica, and Mill Valley, in addition to being the sole guest for the evening on PBS-TV's The Tavis Smiley Show.

Odetta was honored on May 8, 2008, at a historic tribute night,[21] hosted by Wavy Gravy, held at Banjo Jim's in the East Village. Included in the billing that night were David Amram, Vincent Cross, Guy Davis, Timothy Hill, Jack Landron, Christine Lavin, Madeleine Peyroux and Chaney Sims.[21]

In summer 2008, at the age of 77, she launched a North American tour, where she sang from a wheelchair.[22][23] Her set in later years included "This Little Light of Mine (I'm Gonna Let It Shine)",[24] Lead Belly's "The Bourgeois Blues",[24][25][26] "(Something Inside) So Strong", "Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child" and "House of the Rising Sun".[23]

She made an appearance on June 30, 2008, at The Bitter End on Bleecker Street, in New York City for a concert in tribute to Liam Clancy. Her last big concert, before thousands of people, was in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park on October 4, 2008, for the Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Festival.[2] Her last performance was at Hugh's Room in Toronto on October 25.[2]

Death

In November 2008, Odetta's health began to decline and she began receiving treatment at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York. She had hoped to perform at Barack Obama's inauguration on January 20, 2009,[2][27] but she died of heart disease, twenty-nine days before her 78th birthday, on December 2, 2008, in New York City, at the age of 77.[2][28][29]

At a memorial service for her in February 2009 at Riverside Church in New York City, participants included Maya Angelou, Pete Seeger, Harry Belafonte, Geoffrey Holder, Steve Earle, Sweet Honey in the Rock, Peter Yarrow, Maria Muldaur, Tom Chapin, Josh White Jr. (son of Josh White), Emory Joseph, Rattlesnake Annie, the Brooklyn Technical High School Chamber Chorus, and videotaped tributes from Tavis Smiley and Joan Baez.[30]

Legacy

Odetta influenced Harry Belafonte, who "cited her as a key influence" on his musical career;[2] Bob Dylan, who said, "The first thing that turned me on to folk singing was Odetta. I heard a record of hers Odetta Sings Ballads and Blues in a record store, back when you could listen to records right there in the store. Right then and there, I went out and traded my electric guitar and amplifier for an acoustical guitar, a flat-top Gibson. . . . [That album was] just something vital and personal. I learned all the songs on that record";[31] Joan Baez, who said, "Odetta was a goddess. Her passion moved me. I learned everything she sang";[32] Janis Joplin, who "spent much of her adolescence listening to Odetta, who was also the first person Janis imitated when she started singing";[33] the poet Maya Angelou, who once said, "If only one could be sure that every 50 years a voice and a soul like Odetta's would come along, the centuries would pass so quickly and painlessly we would hardly recognize time";[34] John Waters, whose original screenplay for Hairspray mentions her as an influence on beatniks;[35] and Carly Simon, who cited Odetta as a major influence and told of "going weak in the knees" when she had the opportunity to meet her in Greenwich Village.[36] In 2023, Rolling Stone ranked Odetta at number 171 on its list of the 200 Greatest Singers of All Time.[37]

Discography

Filmography

| Film/programme title | Info | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Cinerama Holiday | Film | 1955 |

| Lamp Unto My Feet | TV | 1956 |

| Tonight with Belafonte | TV musical variety (Emmy Award) | 1959 |

| Toast of the Town | TV[38] | 1960 |

| Sanctuary | Dramatic film[39] | 1961 |

| Have Gun—Will Travel episode 159/226: "The Hanging of Aaron Gibbs" |

TV drama[40] | 1961 |

| Les Crane Show | TV talk, variety | 1965 |

| Tennessee Ernie Ford Show | TV[41] talk, variety | 1965 |

| Festival | Film documentary[42] | 1967 |

| Live from the Bitter End | TV concert | 1967 |

| Clown Town starring Odetta & Bobby Vinton |

NBC-TV music special | 1968 |

| The Dick Cavett Show | TV talk, variety | 1969 |

| The Johnny Cash Show | TV musical variety | 1969 |

| Sesame Street | Episode 117 | 1970 |

| The Virginia Graham Show | TV[43] | 1971 |

| The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman | TV film | 1974 |

| Soundstage: Just Folks with Odetta, Tom Paxton, Josh White Jr. and Bob Gibson |

TV concert special | 1980 |

| Ramblin': With Odetta | TV concert special | 1981 |

| Chords of Fame | Film documentary[44] | 1984 |

| Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade | 1989 | |

| Boston Pops with Odetta, Shirley Verrett and Boys Choir of Harlem |

TV concert | 1991 |

| Tommy Makem & Friends | TV concert | 1992 |

| The Fire Next Time | TV film[45] | 1993 |

| Turnabout: The Story of the Yale Puppeteers | Film documentary[46] | 1993 |

| Odetta: Woman In (E)motion | German TV concert special | 1995 |

| Peter, Paul and Mary: Lifelines | TV[47] | 1996 |

| National Medal of Arts and Humanities Presentations | TV (C-SPAN) | 1999 |

| The Ballad of Ramblin' Jack | Drama[48] | 2000 |

| 21st Annual W.C. Handy Blues Awards | Awards ceremony[49] | 2000 |

| Songs for a Better World | TV concert special | 2000 |

| Later... with Jools Holland with Odetta and Bill Wyman & His Rhythm Kings |

BBC-TV | 2001 |

| Politically Incorrect with Bill Maher | TV talk show | 2001 |

| Late Show with David Letterman | TV talk show, variety | 2001 |

| Pure Oxygen | TV talk show | 2002 |

| Newport Folk Festival | TV concert special | 2002 |

| Janis Joplin: Pieces of My Heart | BBC-TV biography special | 2002 |

| Get Up, Stand Up: The Story of Pop and Protest |

Film documentary[50] | 2003 |

| Tennessee Ernie Ford Show | TV musical variety, rebroadcast | 2003 |

| Ralph Bunche: An American Odyssey | PBS-TV biography | 2003 |

| Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin | PBS-TV biography | 2003 |

| Visionary Awards Presentation | PBS-TV award presentation | 2004 |

| Lightning in a Bottle – Salute to the Blues | Film documentary | 2004 |

| No Direction Home | Film documentary | 2005 |

| Talking Bob Dylan Blues | BBC-TV concert special | 2005 |

| Odetta: Blues Diva | PBS-TV concert special | 2005 |

| Odetta: Viss Notiek | Latvian TV Weekly Journal | 2006 |

| A Tribute to the Teachers of America | PBS-TV special: Concert at Town Hall, New York City Odetta sings a medley of the children's songs "Rock Island Line", "Here We Go Looptie-Lou", "Bring Me Little Water Sylvie" |

2007 |

| The Tavis Smiley Show | PBS-TV discussion, performance of "Keep on Movin' It On" | January 25, 2008 |

| Mountain Stage HD: John Hammond, Odetta, and Jorma Kaukonen | PBS-TV concert special | 2008 |

| Odetta Remembers | BBC Four interview and concert footage[51] | February 6, 2009 |

| The Yellow Bittern | Film biography of Liam Clancy, of the Clancy Brothers | 2009 |

External links

- Odetta's oral history video excerpts at The National Visionary Leadership Project

- AP Obituary in The New York Times

- Windsor now

Odetta, the classically trained folk, blues and gospel singer who used her powerfully rich and dusky voice to champion African American music and civil rights issues for more than half a century starting in the folk revival of the 1950s,died on Dec. 3, 2008, She was 77.

She was admitted to Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City for a checkup in mid-November but went into kidney failure. She died there Tuesday of heart disease, her manager, Doug Yeager, told the Associated Press.

With a repertoire that included 19th century slave songs and spirituals as well as the topical ballads of such 20th century folk icons as Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger, Odetta became one of the most beloved figures in folk music.

She was said to have influenced the emergence of artists as varied as Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Janis Joplin and Tracy Chapman.

"The first thing that turned me on to folk singing was Odetta," Dylan once said. "From Odetta, I went to Harry Belafonte, the Kingston Trio, little by little uncovering more as I went along."

Her affinity for traditional African American folk songs was a hallmark of her long career, along with a voice that could easily sweep from dark, husky low notes to delicate yet goose bump-inducing high register tones.

"The first time I heard Odetta sing," Seeger once said, "she sang Leadbelly's ‘Take This Hammer’ and I went and told her how I wish Leadbelly was still alive so he could have heard her."

She was born Odetta Holmes in Birmingham, Ala., on Dec. 31, 1930. Her father died when she was young and she moved to Los Angeles at age 6 with her mother, sister and stepfather. She took the surname of her stepfather Zadock Felious, but throughout her career she used just her given name.

And although Los Angeles wasn't as overtly racist as the Deep South, she suffered some of the same indignities that came with being black.

"We lived within walking distance of Marshall High School," Odetta told The Times some years ago, "but they didn't let colored people go there, so we had to get on the bus and go to Belmont High School."

She attended Los Angeles City College after high school and earned a degree in music.

Trained as a classical vocalist as a child, she won a spot with a group called the Madrigal Singers in junior high school. She also realized early that despite her classical training, her options in that area were going to be limited because of the racism at the time.

By 19, Odetta had turned her attention to other forms of music and landed a part in a production of "Finian's Rainbow" as a chorus member. When the musical went on the road to San Francisco, she went with it.

The trip marked an important crossroads in her emergence as a folk singer.

She met an old friend from school who had settled in the city's North Beach neighborhood, and during a visit Odetta was exposed to a late-night session of folk songs.

"That night I heard hours and hours of songs that really touched where I live," she told The Times. "I borrowed a guitar and learned three chords, and started to sing at parties."

The traditional prison songs that she learned in her early days hit home the hardest and helped her come to terms with what she called the deep-seated hate and fury in her.

"As I did those songs, I could work on my hate and fury without being antisocial," she recalled. "Through those songs, I learned things about the history of black people in this country that the historians in school had not been willing to tell us about or had lied about."

Odetta left the theater company in 1950 and took a job at a folk club in San Francisco. She soon began to tour and recorded her first album, "The Tin Angel," in 1954. She soon caught the attention of such folk-music icons as Guthrie, Seeger and Ramblin' Jack Elliott. She was a fixture on the folk music scene by the time the genre's commercial boom came in the late 1950s and early '60s.

She played at the Newport Folk Festival, the showcase event for folk music, four times between 1959 and 1965. She also had a recording contract with Vanguard Records, which at the height of the folk music craze was the genre's leading label.

Over the years, Odetta branched into acting, with dramatic and singing roles in film and television including "Cinerama Holiday," "Sanctuary" and "The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman."

But traditional folk music remained her forte.

Source: Randy Lewis & Mike Boehm

http://www.mnblues.com/review/2002/odetta-intv-dm.html

Interview:

Odetta

"The Music is Energy"

by Danny Murray

2000

Photography copyright © 2002 by Chuck Winans, all rights reserved

Keeping the Blues Alive Award Winner: Achievement for Blues on the Internet. Presented by the Blues Foundation

music bar

Odetta

celebrated her 50th year in Show Business with the release of "Blues

Everywhere I Go," the 27th solo album of her career. She will be the

headliner at this year's Limestone City Blues Festival in Kingston

August 24, 2000. With this recording, which has received a 2000 Grammy

Award Nomination in the Traditional Blues Album category and two W.C.

Handy Award nominations, Odetta pays homage to the great Blues women of

the 20's and 30's.

Born in Alabama in 1930, she began her music

career as one of the first woman folk artists of the fifties. Along with

her new album, a must have is the "Odetta: Best of the Vanguard Years"

collection, which includes a 1963 concert at Carnegie Hall with bassist

Bill Lee (Spike's dad). She influenced such artists as Joan Baez, Janis

Joplin, and even Bob Dylan, who said, "I learned all the songs on her

first record word for word."

The Sixties witnessed Odetta as a

major voice in America's Civil Rights Movement. She marched with Martin

Luther King, and performed for President Kennedy on a nationally

televised Civil Rights Program. She has appeared on stage and screen,

appearing at Stratford, and in the 1960 film "Sanctuary" starring with

Lee Remick and Yves Montand. She was the first recipient, in 1972,along

with Marian Anderson and Paul Robeson of the "Duke Ellington Fellowship

Award."

Blues Picture

In 1975 she hosted the Montreux

(Switzerland) Jazz Festival, and since then has starred at virtually

every other major festival around the world. She has performed in plays

by Toni Morrison, and has been a best friend of poet Maya Angelou for

over fifty years. She was recently honoured by President Clinton on the

Anniversary of her 50th year as an entertainer. She was quoted once as

saying, "Music is outside the path we walk every day. Ever since

primitive man we have been lifted by it, and we want to be lifted by it.

Even though we're heading for Mars and a push-button world, we still

have our basic emotions to deal with and that's where songs are coming

from."

Odetta spoke to me by phone from her home in New York City.

DM: You have a very busy schedule this year.

ODETTA:

(Laughing) Yes, isn't that great! You sound like you are in a tunnel. I

don't hear the crackling, which means I can concentrate on what your

voice is saying. You're recording. Yes. Good, good, good, good.

DM:

Douglas Yaeger (her manager) sent me a ten-page information sheet on

your background and I must say you have an amazing life and I really

appreciate the opportunity to talk with you.

ODETTA: May I say

that that's a two way street. (I laugh) I really do. I really do admire

the fact that there is someone here who wants to get into whatever we're

going to get into. (She laughs)

DM: Thank you. I am a big fan of

the Blues myself, and I really think that it is great the way it is

becoming more appreciated these days.

Blues Picture

ODETTA: It really is growing in audience isn't it.

DM:

Years ago when you came out with your first Blues album in the early

Sixties people were upset because you were moving away from the folk

genre.

ODETTA: Those were our purest days. Ha ha. The people were

pure. It had to be folk or it had to be blues. We didn't know back

then. We weren't told by the people who researched the music, and they

probably didn't recognize it either. You know this is a country the US

of separation. We separate each other. I don't know if we do that of our

own accord. We do that because industry does that. Puts one against the

other. In order to pay lower wages for the other. Ok. And we didn't

recognize back then that there was no way to put up a wall between one

music and another. As people came into this country, we did not hang out

with each other in our churches, our mosques or our synagogues, in our

homes, hovels or out on the street. We didn't invite each other over to

our own places, but the music. Each of us heard each other's music. And

as we heard there is no way you can delete what you have heard out of

your mind. Whether it be your parents scolding you. Ok a sidebar here. I

wonder if you can remember things your parents told you and you thought

it went in one ear and out the other ear. And then years later recalled

what they said. (We both laugh) Well there was no way to separate

music. Although that was the way we were thinking because that was the

way of our earning a living, and the people we believed. So one thing

has led into another. The cousins, the brothers and sisters, each of the

music areas coming out of the United States. Unless it is a pure

Appalachian song, or a pure Irish song with the fiddles and whatever,

when they got here honey they got mixed up with stuff, as a matter of

fact I was always curious as to an Englishman by the name of Child's.

Child's ballads, he collected there and then he came over to Appalachia

and he collected there similar songs. When you come from a country into

another country you bring what you learned there in country A. You bring

country A with you and then when you are chopping down the trees and

building houses and do whatever else you are going to build you have

other experiences. So you add and this is not a conscious thing. You add

what your experience is to what you come out of and from. So the

people's experience here, whether black or white or Mexican, now the

originals here. they put there experience together and the music is the

result of what their experiences have been. That is why the wide stroke

of music that is coming out of United States, and I have a feeling that

the rest of the world is absolutely fascinated with this cup of soup.

DM: This is your first album in fourteen years and you chose the Blues.

Blues Picture

ODETTA:

Because Mark Carpentieri at MC records came to us and he was interested

in doing a blues record and that was right up my alley.

DM: Even in your folk there is blues.

ODETTA:

Did you hear what I was saying to you in the last ten minutes. It isn't

separated. All that folk stuff is a part of what the blues is.

DM: It is just what you lived.

ODETTA: No not what I lived. I am a historian, an observer; I have noticed things and that is all that I can claim.

DM:

But you have not just been observing, you've been doing and I have

noticed that you have been doing some great things as well. I have

picked up your Village Vanguard release and your voice is amazing. And

the songs with just you and Bill Lee's bass are special.

ODETTA:

While we are talking I would like to just say here that one of the

greatest teachers that I have ever had was Alberta Hunter. She was

wonderful. As I was a youngster listening to old blues records I heard

energy, and I thought you get that energy by yelling hollering and

screaming. And if you compare those two records, the old blues record

and this new one. I have not done this yet, but one of these days I

would like to compare what I did when I was a younger one and what I did

after I learned lessons from Alberta Hunter. This little wee biddy lady

at the age of 84, as she was singing she didn't yell scream or holler.

She just dug her little feet into the floor. And pushed up from the

bottom, the diaphragm, and she focused, she told a story. And that's

what I am working on. I started working on this record, and as Seth

Farber (piano player, producer) and I go around I am working on trying

not to over say anything, and keeping away from yelling screaming and

hollering.

DM: While you do that beautifully.

ODETTA: Thank you

DM: Have you met Alberta Hunter.

ODETTA:

I did meet her, but it was like she was a teacher, and I never did sit

and talk with teachers. I thanked them and then sat off and listened. I

did so appreciate her, and she was quite gracious to me also. But I

mostly learned from watching her perform and listening to her perform.

DM:

Your biography seems very linear. Were there times where you didn't

perform? It looks like you have been on the road for fifty years doing

your thing, and always had great audiences wherever you went. Were there

hard times as well?

ODETTA: I have always performed. I have been

able to earn my living via love of the music. I might have been 22 or

23 when I received unemployment checks for two weeks. Outside of that I

have been able to earn my living

DM: Amazing

ODETTA: It

truly is. You know the world's greatest voice could be walking around

and trying to get someone to listen to them. It has an awful lot to do

with luck and timing.

DM: Luck and timing, but you went out there and did it.

Blues Picture

ODETTA:

Well, you have to have a little something. (Laughs) Maybe not just a

little something. Because I have heard an awful lot of people who ain't

got nothing honey, and they project it, and there is somebody putting

money in back of it. So, it's not a given.

DM: You have always seemed to stay true to your love, and what you wanted to do.

ODETTA:

Fortunately I have been politicized by Paul Robeson, and Marian

Anderson, and I have been politicized by the people around the area of

folk music. I truly need to feel like I am useful. I know there are

people who would like to disconnect what our living is from politics,

but there is just no way you can do that. So I have been involved with

being supportive of what I call righteous causes and that keeps my feet

on the ground.

DM: When you are coming to Kingston, who is coming with you.

ODETTA: Seth Farber. There is one concert I am bringing my guitar, and I don't know if this is the one.

DM: You can bring your guitar. And if you need one we will find one for you.

ODETTA: Well thank you, I have been with Seth over a year now, and he is simply wonderful.

DM: What are some of the other things you will be doing this summer.

ODETTA: Our next thing is the Cambridge Festival in England, and the Knitting Factory in California

DM: There are many Odetta sites now on the Internet, is it possible to e-mail you directly.

ODETTA: Honey I have just mastered the touch tone phone.

DM: The Kingston Blues Festival is looking forward to having you.

ODETTA: Are you going to come up to me and say hi.

DM: Certainly, and one last question. If you could wave your magic wand and change anything in the world what would it be?

ODETTA:

(Long pause) I think maybe I would wave the magic wand and take the

meanness, the callousness, and the need to hurt, along with the area of

greed. I think I would erase that out of the human person.

DM: I think the world would still survive if you did that, and it might be a better world.

Blues Picture

ODETTA:

That is the only way we are going to survive. We can't survive on war.

We still have land mines and children are losing limbs, we are still

having embargoes where children can't get medicine or food. Oh, please

we can't survive on that.

DM: You have done so much for music breaking ground for women and women of color.

ODETTA:

As an observer you see all that. But with a performer, or a writer, or a

poet or an architect they're on to the next thing. They're not looking

back. You are observing. And it would take you to make mention of what

has come before and the stuff that they have done. I am not back there. I

am wondering what I am going to do the day after tomorrow.

DM: Thank you very much, you are a beautiful person, and I look forward to seeing you at the Kingston Blues Fest.

ODETTA: It takes a beautiful person to know one, and I enjoyed talking to you too.

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/how-odetta-revolutionized-folk-music

How Odetta Revolutionized Folk Music

In 1937, Odetta Felious Holmes moved from Birmingham, Alabama, to Los Angeles. Only six, she was already bigger than the other kids when she arrived in East Hollywood with her mother, Flora, and her younger sister Jimmie Lee. At home, Flora stressed the importance of “proper diction” and straightened her daughters’ hair. On Saturday afternoons, Odetta and Jimmie Lee listened to the Metropolitan Opera on KECA. Her stepfather, Zadock Felious, had a different taste in music. He took over the radio on Saturday nights and tuned in to the Grand Ole Opry, broadcast directly from Nashville. Odetta raised her eyebrows at the rough-hewn songs and comic sketches, but she listened. Twenty years later, Odetta would redirect the path of something called “folk music” by synthesizing the stagecraft of opera and country on prime-time television. But, in 1937, few people outside the academy were talking about folk music, and there wasn’t a single figure in popular culture who looked like Odetta.

At eleven, Odetta began taking piano lessons. One day, while singing scales with a friend, Odetta hit a high C. Her piano teacher told Flora that Odetta should start taking voice lessons. When Flora began working as a custodian for a puppet show called the Turnabout Theatre, one of its founders, Harry Burnett, heard Odetta singing—or “screeching,” as Odetta described it—and decided to pay for her lessons with a voice teacher named Janet Spencer. A contralto who recorded some of the earliest opera sides for Victor Talking Machine Company’s Red Seal label, Spencer taught Odetta German lieder and other art songs. After high school, Odetta worked in a department store and a button factory while studying European classical music at Los Angeles City College in the evenings. “I had a dream of getting a quartet together,” Odetta said, years later, “learning the repertoire of the oratorios, and then offering ourselves to schools and churches.” Marian Anderson and Roland Hayes had found fame in both Europe and America, so the idea of a Black classical-music career was not unrealistic.

In 1950, “Finian’s Rainbow,” first a Broadway hit in 1947, was revived for an outdoor presentation at the Greek Theatre in Los Angeles’s Griffith Park. A romp about a leprechaun laced with a dash of social-justice pedagogy, “Finian’s Rainbow” tells the story of a racist senator who is zapped into being Black, so that he may experience the sting of Jim Crow laws firsthand. Odetta joined the show as a chorus member, and received positive reviews. Her childhood voice coach had died, and Odetta had started working with a singer from New York named Paul Reese, who coaxed her considerable lower range into a true contralto voice. Reese also encouraged Odetta to open herself up to the burgeoning folk movement but, as Ian Zack writes in “Odetta: A Life in Music and Protest,” she had been “taught to look down on such lowbrow fare, [and] wasn’t quite ready to heed that advice.”

That summer, in 1950, the folk quartet the Weavers put their chirpy, orchestral version of Lead Belly’s “Goodnight, Irene” at No. 1 for thirteen weeks in America. “No American could escape that song unless you plugged up your ears and went out into the wilderness,” Pete Seeger, then a member of the Weavers, later said. Lead Belly’s original, itself likely a remodelling of a Texas folk ballad, talks of a woman who is “too young” and who vexes the singer so much that he talks of “jumping in, into the river” and drowning. The Weavers dropped the statutory rape, kept the river, and tacked a marriage announcement to the top of the song. Their version sounds like a field of Disney bluebells breaking into song.

In July, 1951, Odetta visited San Francisco as part of a summer-stock performance of “Finian’s Rainbow,” her first trip away from home. Her childhood friend Jo Mapes was living there, and came out to see the woman she knew as ’Detta. “She was one of the Ziegfeld girls, dressed up like one, who came down the famous Ziegfeld stairway,” Mapes said. “And there was ’Detta, anything but slim, anything but a dainty beauty.” Mapes and Odetta went to a bar called Vesuvio that night and returned to Mapes’s apartment, where they stayed up singing songs that were generally categorized as blues or gospel but were beginning to be described as folk: “Take This Hammer,” “Another Man Done Gone,” “I’ve Been ’Buked and I’ve Been Scorned.”

“In the songs I heard that night, including prison songs,” Odetta told Sing Out! magazine, in 1991, “I found the sadness, the loneliness, the fear that I was feeling at the time. It turned my life around.” The earliest chart versions of folk music had presented songs from a vague but anodyne past, unspecific in politics and cultural origin. Electric instruments were mostly verboten, giving the movement a conservative aesthetic. Even as the music was being slowly tied to Communism (sometimes accurately), the demeanor of the genre was cheerful and unthreatening. Then Odetta developed a form that had the elastic power to change popular music. The same qualities that made her music radical in the fifties also make her work sound antiquated now: a Black woman animated the horror and emotional intensity in American labor songs by projecting them like a European opera singer. If we are to speak of “dunks” in twentieth-century popular culture, this is up there. Odetta was the secret-agent contralto, amplifying a history of pain others were using for sing-alongs.

Once back in Los Angeles, Odetta began to build her project. She studied Carl Sandburg’s “The American Songbag” anthology and found recordings of prison songs archived by the Library of Congress, preserved on tape by John and Alan Lomax. Folk music, paradoxically, is one of the most mediated forms of song we have. Odetta didn’t only sing songs handed down to her through the ages. She located many of her sources in libraries, and likely heard others on records and the radio. The basic idea, that the songs in question are part of a homegrown, amateur tradition not rooted in commercial entertainment, is not completely untrue, but the necessary interventions of the recording era make the idea sort of fanciful. The decisions made in preserving folk music create as much artifice as a producer sending a vocal through a stack of effects—the difference being that the song being revived may have represented a practice (singing outside while breaking rocks) or tradition (telling stories through song) that would otherwise have been lost. But once you factor in the bowdlerizations of the Weavers and the rewriting that even Lead Belly did on a song like “Goodnight, Irene,” you’re not looking at an act so different from quoting a tune in a solo or sampling a break beat. A musician found some preëxisting piece she liked and decided to use it in her own music.

Odetta had a specific archival focus, though. As Matthew Frye Jacobson writes in “Odetta’s One Grain of Sand,” his novella-length analysis of the Odetta album of the same name, “Odetta rescued black artistry from the often disparaging—if romantic—world of American folklorists themselves, whose own problematic practices she was clearly alert to.” She worked on her guitar technique with a teen virtuoso named Frank Hamilton, who helped her develop “the Odetta strum,” a variation on the musician Josh White’s double-thumb rhythm technique. Her voice was already an incredible force, and her guitar playing became deft and powerful. She could have gone into any number of fields, most obviously stage and film, but she’d found an error of affect in folk music that she could correct. “As I sang those songs, nobody knew where the prisoner began and Odetta stopped, and vice versa,” she told NPR, in 2005. “So I could get my rocks off, being furious.”

Odetta and Elvis Presley both put out their first records in 1954, when there was nothing like pop music as we know it now. Color TV had just arrived but was not yet common. There had not yet been any Beatles, James Brown, Aretha Franklin, or Rolling Stones records. Some of the songs that would become staples of the (white) English blues movement were about to be introduced into the popular consciousness—by Odetta. It was precisely Odetta’s ability to convey spiritual elevation and personal pride that allowed her to convince a suspicious public that “Another Man Done Gone” was as important as “Goodnight, Irene,” and that Black Americans had a right to hear stories of their history in the present as popular culture. Listening to her fifties records now, though, they don’t sound like popular music, as a Lead Belly recording from 1935 often does. Odetta’s dignity is precisely what might alienate a younger listener wanting a more unfettered kind of anger; there’s something missing from her regal delivery and allegorical songs.

If “Blade Runner” and “Seinfeld” were early manifestations of the twenty-first century, Odetta was the last glowing ember of the nineteenth century, a performer who made her name on the stage with a voice that could reach the cheap seats and the town square, too. Bob Dylan’s early records are omnipresent, whereas Odetta’s are not. Certainly a matrix of biases helped bring about this outcome, most of them unfair. But at least one deals with the character of her singing itself. Her 1957 album “At the Gate of Horn” is recorded well, and Odetta’s vocal quality is as heavy and shiny as gold. She did not let go of her opera willingly. Until the seventies, when she began to loosen her vocals, Odetta rarely missed a chance to use her chest voice, extend a note, and twist it with vibrato. If you’re wondering what makes her music sound like opera, it’s that. In pop, whether you’re Ariana Grande or Phoebe Bridgers, you generally hold long notes without vibrato. You can do vibratoless singing at any volume, in any setting—it’s how most people sing. Pop is dedicated to the elevation of amateurs (or the idea of them being amateurs, just like you), and this changed the larger frame of how we hear and interpret operatic singing: not generally the pursuit of hobbyists, to a contemporary ear, it does not sound like pop.

Odetta’s song selection on that 1957 album? As atomized as America itself. “The Fox” (yes, the “little one chewed on the bones oh” song) and “Gallows Tree (Gallows Pole)” (yes, the old English ballad rewritten by Lead Belly and later stolen by Led Zeppelin) and “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” (yes, the Black American spiritual that ended up in a Volvo ad)—all of these, on one record. And then there’s her version of “Greensleeves,” which sounds like it’s being sung by a matron standing erect with hands gently folded before her. This is followed by the roots romp “Devilish Mary,” a nineteenth-century American song covered by both Seeger and the Grateful Dead. You see the problem with trying to revive a record like this: this kind of sprawl has been replaced by commercial specialization. The record was a mix of kids’ songs and blues and spirituals—if you did that now, you’re probably seen largely as a kids’ performer. And yet even Odetta’s children’s music threatened white America. When she went on the “Today” show in 1957, her first national television appearance, she was presented in a minimized form. Zack quotes Odetta’s manager at the time, Dean Gitter, as saying that the co-host of the show, Jack Lescoulie, “didn’t know what to make of Odetta, didn’t know what to make of folk music.” She ended up singing “The Fox,” which Gitter said “was all the Today Show could stand.”

A recording and film star who had a deep respect for Odetta’s work, Harry Belafonte, was tapped by Revlon in 1959 to do a prime-time live variety show. Belafonte “started envisioning a portrait of Negro life in America told through music.” Asked by executives who he would have on, he said, “First and foremost will be Odetta.” When asked what she looked like, he responded, “She’s a Nubian Queen. She is the mother of history, of all of Africa. Her beauty reigns as supreme.” Maybe the Beatles on Ed Sullivan was a big deal—I wasn’t there. But the clip of Odetta singing “Water Boy” on Belafonte’s special can still stop time, even in a compressed YouTube video.

Odetta opens with a summoning, voice hard and slightly above her lowest notes. The camera slowly zooms in on her, in a long-sleeved dress, lit by one spotlight. A prisoner, as unnamed as the original songwriter, yells to the water boy, only slightly more free than he is, “Waterboy / Where are you hiding? / If you don’t come right now / I’m going to tell your pa on you.” The singer changes from teasing to bragging. “There ain’t no hammer / That’s on this mountain / That ring like mine, boy.” For the second verse, she drops into a conversational register. For the third verse, she adds a wordless yelp and bangs her hand on the guitar for emphasis. It is the sound of the hammer. Very much like Kurt Cobain performing Lead Belly’s “In the Pines” for television thirty-four years later, Odetta erased the idea of music as entertainment. She happened, on television. For any viewers somehow still under the spell of Lost Cause politics, imagining satisfied Black workers all over the land, Odetta suggested something else. The Black worker, the Black prisoner, the Black singer—they were all of them alone.

By 1959, Odetta had transformed how people conceived of popular music in America. “If I had to pick one person responsible for the establishment of the Newport Folk Festival in 1959, it would be Odetta,” George Wein, the founder of the festival, recalled. Dylan told Playboy magazine, in 1978, “The first thing that turned me on to folk singing was Odetta.” Talking about his activities in 1961, he went on to say, “I heard a record of hers in a record store, back when you could listen to records right there in the store. . . . Right then and there, I went out and traded my electric guitar and amplifier for an acoustical guitar, a flat-top Gibson,” the same model Odetta played.

In 1960, right after that TV special, Odetta and Belafonte recorded one of her biggest hits, “A Hole in the Bucket,” a rendition of the German children’s song. If Odetta hasn’t made it back into your conception of either emancipatory politics or popular music, it is not just because she sang like an opera star. Her commitment to her own vision simply didn’t waver. The songs she thought were important—sometimes songs for children—did not cohere with the kind of smooth self-similarity that evolved with pop music and is demanded by brands now.

When she recorded “Odetta and the Blues” in April of 1962, at only thirty-one years old and in an era still very early in the arc of the blues revival, she and producer Orrin Keepnews made the decision to use a Dixieland sextet complete with clarinet and trombone, a formation decades out of fashion. Add that outmoded setup to a selection of songs made popular by prewar singers such as Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith, and the resulting aesthetic could be fairly called old. The critic John S. Wilson, at the time, said of this album that Odetta “lacks the warmth and sense of involvement that make a blues singer,” a statement that becomes increasingly confusing if you imagine what “blues singer” would even mean today. If this album sounded out of step in 1962, now it comes across as a historical reconstruction.

Many of the fences Odetta vaulted no longer exist, but nor do the sites of her success. Her early triumphs happened in a series of coffeehouses and small clubs that are long gone. When singers such as Joan Baez and Carly Simon talked about being converted to Odetta as young adults, they were talking not about seeing her on television but about seeing her live in small rooms, where her force must have been like the space program: implausible and transformative. And even those television variety shows, long a way of calibrating America’s cultural equator, are gone. For unknown reasons, there’s also very little footage of Odetta playing live in her early years; most of her appearance at the 1963 March on Washington went unfilmed. A few more clips and she might have found her way into the Ken Burns slipstream.

In August, 2020, during an online conversation about Odetta, Jacobson said that Odetta is “almost unknown among younger Americans right now.” My own experience with Odetta’s music is nearly as limited as that of Professor Jacobson’s students. Through decades of rustling and listening and collecting, Odetta has barely crossed my view. I’ve heard Odetta’s music but never owned one of her records. Even d.j.s committed to blending histories into their mixes have mostly avoided Odetta’s songs. Two d.j.s did not, though, and this could be why people know Odetta now. In a 1999 collaborative mix called “Brainfreeze,” DJ Shadow and Cut Chemist manipulated the vinyl of Odetta’s song “Hit or Miss,” a bass-heavy track from her 1970 album, “Odetta Sings.” Upon hearing it, a music supervisor at GEMS sought out the original, later licensing it as the soundtrack for a popular ad, created by Wieden+Kennedy, for Southern Comfort, in 2012, for which they won three Clio Awards. In the spot, we see a chunky, oiled-up man—wearing leather shoes, a Speedo, sunglasses, and nothing else—walking purposefully and slowly along a beach. He steps over an old man! He dips his shoulder to a young woman! This gentleman knows what is comfortable, we gather. Odetta didn’t get us here—Russ Kunkel’s stolid, slow backbeat and Bob West’s wandering bass line put Odetta back in business—but the vocal nails it all the way down. Odetta opens with a wordless series—“la l-la la”—that gives the track a lightly drunk feeling. “Oh, can’t you see? / I gotta be me” the lyrics start, acting as the thought bubble for our beach champion. She still sounds proper, though she is loosened up, more than a little like Joan Armatrading. That stagy feel comes from the chest voice and vibrato, slightly recalling Bryan Ferry’s meretricious wobble here. “Ain’t nobody just like this / I gotta be me, baby / Hit or miss.” On the same album, there’s even a version of the Rolling Stones’s “No Expectations,” which finds a Black woman from the South reshaping the performance of a white British man trying to sound like some kind of pan-racial American wanderer: “I’ve got no expectations / To pass by here again.” Jagger plays this as nihilism lite, but Odetta has no truck with detachment, and sings the Stones song like a mournful god giving up on a world that won’t listen. “Hit or Miss” wasn’t wrong: Odetta did, in fact, have to be herself, and had a career that matches nobody else’s. “Odetta Sings” is one of many moments where you can hear how far she was able to go, and also how little she cared about commodity cohesion.

When the brilliant singer and instrumentalist Rhiannon Giddens made her début on David Letterman, in 2016, she performed Odetta’s arrangement of “Water Boy,” accompanied by a band. The musicians barely capture the force of Odetta by herself, and that excellence was also one of Odetta’s political gestures. Once she began her recording career in earnest, her entire mission was political, from the songs—which she described as “a history of us, and was definitely not in our history books”—to her Afro, one of the first seen in popular culture. When asked years later about her decision to wear her hair untreated, she said, “Nothing but political.” Her work also established the possibility of a certain collective action. As Jacobson writes, “If the movement for racial justice was going to make good use of the pro-democracy leverage that world affairs afforded after the war, it was first going to have to create a viable Civil Rights public amid the smoldering wreckage of the Old Left.” That “Civil Rights public” did not come into rude health until Odetta was there, in coffeehouses and on television shows, turning prison songs back into struggle songs.

Odetta - "House of the Rising Sun"

"If only one could be sure that every 50 years a voice and a soul like Odetta's would come along, the centuries would pass so quickly and painlessly we would hardly recognize time"

"Jim Crow Blues"

Performed by Odetta Holmes (2003)

originally performed by Lead Belly (1930)

From the movie: Lightning In a Bottle: A One Night History of the Blues concert:

New York's Radio City Music Hall (February 2003)

Director : Antoine Fuqua

Executive Producer: Martin Scorsese