AS OF JANUARY 13, 2023 FIVE HUNDRED MUSICAL ARTISTS HAVE BEEN FEATURED IN THE SOUND PROJECTIONS MAGAZINE THAT BEGAN ITS ONLINE PUBLICATION ON NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND HERE, WHERE YOU CAN FIND THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND ‘LABELS' (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

PHOTO: HENRY THREADGILL (b. February 15, 1944)

Henry Threadgill

(b. February 15, 1944)

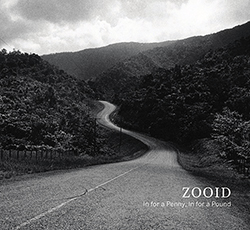

Biography by Chris Kelsey

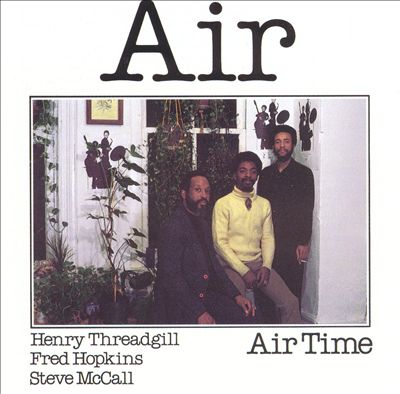

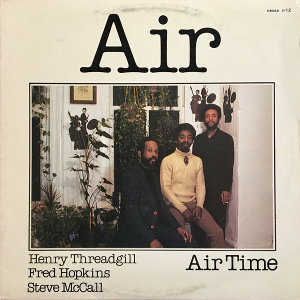

The jazz vanguard has produced hundreds of notable improvisers but relatively few great composers. Saxophonist and flutist Henry Threadgill is both. Alongside fellow Chicagoans Muhal Richard Abrams, Roscoe Mitchell, and Anthony Braxton, he ranks as one of the most original jazz composers to emerge from the 20th century. Threadgill's art transcends stylistic boundaries. He embraces the world of music wholesale, from ragtime, circus marches, classical, and bop to free jazz, reggae, and funk. He spent the 1970s in the groundbreaking experimental jazz trio Air with Fred Hopkins and Steve McCall. They issued profoundly forward-thinking albums such as Air Time. Following, his Henry Threadgill Sextett issued six albums between 1982 and 1989, including Just the Facts and Pass the Bucket and You Know the Number. After the Bill Laswell-produced Too Much Sugar for a Dime in 1993, he founded Make a Move and the first incarnation of Very Very Circus. Both were featured on 1995's Makin' a Move. With Everybody's Mouth's a Book in 2001, Threadgill moved over to Pi Recordings. That same year he created the ongoing Zooid, and released Up Popped the Two Lips. 2015's In for a Penny, In for a Pound won him a Pulitzer Prize. He debuted the octet Ensemble Double Up on Old Locks and Irregular Verbs in early 2016. In 2018, Threadgill issued Double Up, Plays Double Up Plus, followed by Zooid's Poof in 2021.

Threadgill took up music as a child, first playing percussion in marching bands, then learning baritone sax and clarinet. He was involved with the AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians) from its beginnings in the early '60s, collaborating with fellow members Joseph Jarman and Roscoe Mitchell and playing in Muhal Richard Abrams' legendary Experimental Band. From 1965 to 1967, he toured with the gospel singer Jo Jo Morris. He then served in the military for a time, performing with an army rock band. After his discharge, he returned to Chicago, where he played in a blues band and resumed his association with Abrams and the AACM. He went on to earn his bachelor's degree in music at the American Conservatory of Music; he also studied at Governor's State University.

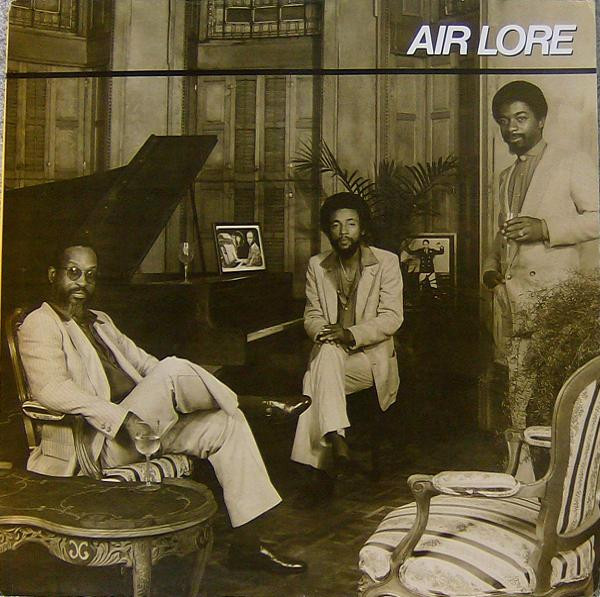

In 1971 he formed Reflection with drummer Steve McCall and bassist Fred Hopkins. The trio would re-form four years later as Air and would go on to record frequently to great acclaim. Their 1979 album Air Lore featured contemporary takes on such early jazz tunes as "King Porter Stomp" and "Buddy Bolden's Blues," prefiguring the wave of nostalgia that would dominate jazz in the following decade. Threadgill moved to New York in the mid-'70s, where he began forming and composing for a number of ensembles. Threadgill began showing a love for unusual instrumentation; for instance, his Sextett (actually a septet) used a cellist, and his Very Very Circus included two tubas. In the mid-'90s he landed a (short-lived) recording contract with Columbia, which produced a couple of excellent albums. Throughout the '80s and '90s Threadgill's music became increasingly polished and sophisticated.

A restless soul, he never stood still, creating for a variety of top-notch ensembles, every one of them different. A pair of 2001 releases for Pi Recordings illustrated this particularly well. On Up Popped the Two Lips, his Zooid ensemble combined Threadgill's alto and flute with acoustic guitar, oud, tuba, cello, and drums -- an un-jazz-like instrumentation that nevertheless grooved and swung with great agility. Everybody's Mouth's a Book featured his Make a Move band, which consisted of the leader's horns with vibes and marimba, electric and acoustic guitars, electric bass, and drums -- a more traditional setup in a way, but no less original in concept. In 2004, a live Zooid date entitled Pop Start the Tape, Stop was issued in limited edition by Hardedge. That same year, Threadgill played on Billy Bang's seminal Vietnam: Reflections.

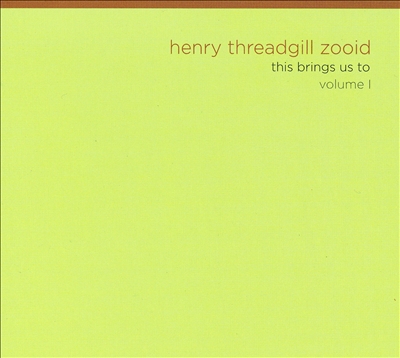

Threadgill performed and rehearsed with both Zooid and Make a Move, but he didn't record again with either until late in 2008. Zooid cut sessions in November of that year, resulting in a pair of albums, This Brings Us To, Vol. 1 issued in 2009, followed by Vol. 2 in 2010. The collector's label Mosaic honored Threadgill by compiling his Complete Novus & Columbia Recordings in a deluxe, limited-run box set. Make a Move hit the studio again in late 2011. The sessions yielded the album Tomorrow Sunny/The Revelry, Spp in June of 2013. In December, Threadgill, bassist John Lindberg, and drummer Jack DeJohnette played in Wadada Leo Smith's quartet for The Great Lakes Suites sessions -- released by TUM nearly two years later.

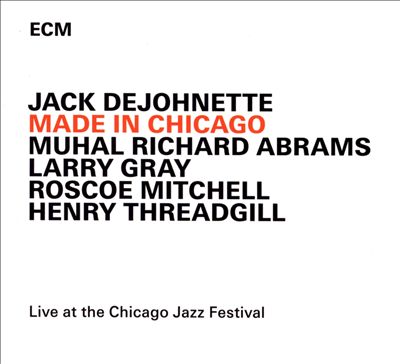

In May 2014, Zooid reconvened in a Brooklyn studio for two days. In August of that year, Threadgill played in DeJohnette's great AACM reunion quintet at the Chicago Jazz Festival, along with Roscoe Mitchell, Muhal Richard Abrams, and Larry Gray. The resulting album, Made in Chicago, was released by ECM in January 2015. In the spring, the previous year's Zooid sessions saw light as the double-disc In for a Penny, in for a Pound. The recording drew universal acclaim and topped the year-end jazz lists internationally. It also netted Threadgill the Pulitzer Prize for Music. The award was presented in April 2016, the same month that Ensemble Double Up (his new octet that included pianists David Virelles and Jason Moran) debuted with Old Locks and Irregular Verbs. In May, he received a Doris Duke Artist Award. In 2018, Threadgill returned with Double Up, Plays Double Up Plus on Pi.

He recorded with Zooid for 2021's Poof. In addition to his own alto sax and flute playing, the quintet included guitarist Liberty Ellman, tubist and trombonist Jose Davila, cellist Christopher Hoffman and drummer Elliot Humberto Kavee.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/henry-threadgill

Henry Threadgill

Henry Threadgill first performed as a percussionist in his high school marching band before taking up the baritone saxophone and later a large portion of the woodwind instrument family. He soon settled primarily upon the alto saxophone and the flute. He was one of the original members of the legendary AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians) in his hometown of Chicago and worked under the guidance of Muhal Richard Abrams before leaving to tour with a gospel band. He later served in the Army, where he played with a rock band. Upon his return to Chicago he rejoined fellow AACM members Fred Hopkins and Steve McCall, forming a trio which would eventually become the group Air, one of the most celebrated and critically acclaimed avant-garde jazz groups of the 1970s and 1980s. In the meantime, Threadgill had moved to New York City to begin pursuing his own musical visions, which explored musical genres in innovative ways thanks to his daringly unique group collaborations. His first group, X-75, was a nonet consisting of four reed players, four bass players and a vocalist. In the early 1980s, Threadgill created his first critically acclaimed ensemble as a leader, Sextett. The group actually had seven members: Threadgill, two drummers, bass, cello, trombone and trumpet. The seven albums the group recorded feature some of Threadgill's most accessible work, notably on the album You Know the Number. During the 1990s, Threadgill pushed the musical boundaries even further with his ensemble Very Very Circus. In addition to Threadgill, the group's core consisted of two tubas, two electric guitars and a drummer. With this group he explored more complex and highly structured forms of composition, augmenting the group with everything from latin percussion to French horn to violin to accordion and an array of exotic instruments and vocalists. By this time Threadgill's place amongst the upper echelon of the avant-garde was secured, so prolific in fact that he was signed by Columbia Records for three albums (a rarity for musicians of his kind). Since the dissolution of Very Very Circus, Threadgill has continued in his iconoclastic ways with ensembles such as Make A Move, Zooid and Flute Force Four. Although Threadgill's musical roots are in jazz, the blues and gospel music, he is considered to be one of the premiere "creative" or avant-garde composers in music today. His compositions are truly American, often representing a melting pot of musical genres; at any given time you may hear cleverly mixed elements of traditional African music, Latin music, folk music, New Orleans brass and opera in addition to his more obvious influences.

His compositions can be a very complex affair, with textures so dense and intricate (and in later years so strictly scored) as to border upon being through composed. While this seems to be in contrast to the loose, improvisatory feel of much jazz, his best compositions still bring that feeling to the forefront. Threadgill has recorded or performed with many of the legends of the jazz avant-garde, including Anthony Braxton, Muhal Richard Abrams, Roscoe Mitchell, Joseph Jarman, David Murray and Bill Laswell.

THE ART MUSIC LOUNGE

An Online Journal of Jazz and Classical Music

Henry Threadgill, Master of Musical Mosaics

I’ve been wanting to write in some detail about Henry Threadgill and his complex, difficult yet fascinating music for a while now, but every time I’ve tried to get started something else has interfered. And one of the things that has interfered the most is the fact that Threadgill’s music is so extraordinarily complex and so unique that it takes extreme concentration just to listen to it, let alone write about it, and to do so—particularly without access to the scores—is frustrating and somewhat intimidating.

I brought up some of Threadgill’s music with the trio Air in my book, From Baroque to Bop and Beyond, in which I surveyed the entire history of the interaction between classical music and jazz (click here to read it), but certainly not enough to do him justice. The reason was that, although Threadgill did indeed study composition at the American Conservatory of Music in Chicago, the music he produces is put together from jazz elements in a way that “speaks” jazz. The vernacular of his music is jazz; the way the elements are put together follow jazz principles; and although the finished products are extraordinary complex, and despite the fact that he has also written for large orchestras (particularly Run Silent, Run Deep, Run Loud, Run High), the finished results only bear a superficial resemblance to classical music in the way they are constructed. If Thelonious Monk, as Ralph Berton claimed, was the Stravinsky of jazz, Henry Threadgill uses principles found in Stravinsky, Schoenberg and Ligeti (perhaps particularly Ligeti) in a way that more closely resembles the more avant-garde work of Ornette Coleman, Michael Mantler and David Murray, while sounding like none of them.

It’s difficult, then, to describe the music of a particularly brilliant lone wolf who operates within his own specific musical universe. This doesn’t mean that it’s not necessary to write about him or impossible, just very difficult. The respected down beat critic John Litweiler summed it up best when he wrote, “He seems to be deliberately challenging the audience: ‘My lyricism and mastery come complete with thorns and spikes, and I promise to yank the props out from under you’.” Essentially, and I am in no way trying to pigeonhole his music by trying to describe it in its basics, Threadgill upsets the balance that exists not only in jazz but in all music in regards to the three principal elements, rhtyhm, melody and harmony. Whereas George Russell pulled the rug out from under the tonal system by declaring thatall music form Bach to Schoenberg, including jazz, was part of a continuum that could be defined by his Lydian Chromatic Concept, and whereas Ornette Coleman took one aspect of Russell’s concept—horizontal movement—to a new level by eliminating root chords and other signposts of tonality (which upset and alienated a great many traditional jazz musicians, though oddly enough, not John Lewis or Pee Wee Russell), Henry Threadgill works in small blocks of sound, sometimes thematic fragments, which he will then ask his musicians to play in the fashion of a round, with different players coming in at different places within the phrase or the beat. This in turn creates new melodic, harmonic and rhythmic forms. In a sense, it’s like taking three different takes of an Ornette Coleman composition and overlaying them, not in synchronization but delayed by a beat or a beat and a half one on top of the other.

Once you understand the principals, Threadgill’s music becomes easier to comprehend, but when I say “easier” I don’t mean that in the sense that modern-day retro bop is easy to comprehend. It’s more like saying that after a period of listening and study, Stravinsky’s late, thorny 12-tone compositions like Agon and the Requiem Canticles become easier to understand. No one is going to walk out of a Threadgill concert whistling tunes; they may not even be able to retain scraps of them to replay in the first place; but the totality of what Threadgill does will stay with you, however disturbing it may be to your expectations or musical sensibilities, for a long time.

Born in 1944, Threadgill studied not only composition but also piano and flute. An early member of the influential Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), Threadgill also studied the music of Stravinsky, Edgard Varèse, Luciano Berio and Mario Bauzá as well as the music of Bali, India, the West Indies and Japan. This is yet another reason, I think, why his finished music strikes me as not so much within a classical tradition as within a “world music” tradition. In addition to these sources, he filters his music through jazz, R&B and the blues to come up with compositions that are distinctly his own.

Since I have been unable to hear his Pulitzer Prize-winning composition, In for a Penny, In for a Pound, and cannot get a copy of his latest album for review, I cannot speak of these works, but I’m sure that they follow the principles of all his music I have heard. Threadgill never stands still, mind you—he refuses to rest on his laurels and doesn’t repeat, if he can help it, concepts or patterns he has already traversed—but there is a consistency in his inventiveness that makes every excursion into his music remarkable. Earlier I said that there are very few signposts of classical form (as such) in his music, but one of those is the insistence that most of the ideas presented be cogent, i.e., they must make sense somehow. There is very little in his music of the far-out explorations of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, though they must have been yet another group he heard while in that city, which prided itself on an amorphous journey through each piece. Threadgill’s music sounds so rigorously constructed that the listener almost feels surprised to discover the improvised solos within it.

A superb example of Threadgill at his best is All the Way Light Touch, an hour-long piece premiered on October 25, 2009 and aired on Roulette TV on April 14, 2010. You can watch and hear the performance here. I think one of the most attractive qualities of Threadgill’s music—and this piece is no exception—is that, despite its complexity, he often maintains a low volume level which draws the listener in. To some extent I think this is because he not only wants the audience to hear each thread of the music individually, but the participating musicians as well. More interesting, to me, is his consistently “quiet” orchestration. Threadgill rarely if ever uses upper-register instruments screaming away at any point in his music. Mostly he prefers to use, for instance, a real jazz guitarist rather than a distorted-sound blues guitarist (again, to promote clarity of execution and line), a cello (to enhance the texture, often playing high in its range, simulating a viola), and a tuba in place of a string bass (again, texture…ever since Gil Evans introduced the tuba to modern jazz back in the 1940s it has been a favorite instrument because of its inherently richer sound), although he does use a bass guitar. Threadgill himself on alto sax and flute provides in this work and others the most overtly “bluesy” sound, yet his innate sense of construction keeps him from squealing out-of-tonality licks for the sake of shock. He always stays within the parameters of the piece he has constructed, whether brief or, as in this case, lengthy, knowing how it is “supposed” to go even if the listener has no clue where it is headed.

Every so often in his extended works, as for instance around the 20-minute mark in All the Way Light Touch, Threadgill will relax the complex, multi-layered rhythm and come to what sounds to the listener like a standard 4/4, but this is an illusion. Threadgill’s meter is always an illusion. He never stays within one pulse for long, and within a minute or two of the listener feeling comfortable he or she will start feeling disoriented again…perhaps even more so than before, because they thought the rhythm was suddenly “normal” and now it’s not again, and you can’t even really tell at which point it changed. Threadgill morphs his beat-shifting gradually; indeed, there will probably be some listeners who won’t even notice, at first, that the band is no longer playing a straight 4 until it becomes so obvious that you can’t escape the change, by which time it is too late for you to realize that Threadgill has expanded his spider’s web of sound and that both you and his musicians are forced to run around the intersecting lines of the music in order to reach the center rather than cutting straight through to it. I can describe this music more technically though I wouldn’t dare attempt to without seeing a score, but this method of defining Threadgill’s operating methods is, I think, clearer for lay listeners to understand. One of Threadgill’s online comments explains the contradiction: “It’s funny when people say things like, ‘The section in 5/4,’ and I say, ‘I’d like to know where that was…I don’t know where you heard that,’ because basically I think in 1/4. Beat to beat, penny to penny, dollar to dollar…I don’t want any sense of meter because when you sense meter, you see and feel division.”[1]

This last statement by Threadgill is, of course, both true and a bit deceptive. He may indeed always think in terms of a single beat, but in performance the beats combine themselves in ways that, as I say, add up to more complex rhythms and layered meter. As another online commentator put it, “There is rarely a ‘1’ to be found anywhere.” In this specific piece Threadgill’s second alto solo, which begins at about 31:20 following a complex drum break, is one of the few times one hears him playing “outside” jazz in the sense I described it earlier; but again, Threadgill’s penchant for musical coherency keeps him from going too far off the deep end. He plays specific notes, no matter how distorted, and not just “sounds” or “emotions.” In other words, solo and composition remain all of a piece.

What I find even more fascinating about Threadgill’s music, and his basic aesthetic, is that he applies the same principles to his shorter pieces as to his longer ones. A good for-instance is his 2012 album, Tomorrow Sunny. Here, he presents us with individual pieces with separate titles, and they are fine and interesting pieces in themselves. Yet in a 73-minute live performance given at the Library of Congress on October 25, 2013 (click here to listen), Threadgill folded three of those pieces—A Day Off, Tomorrow Sunny and Ambient Pressure Thereby—into three others not of the same vintage but of the same general style (Chairmaster, To Undertake My Corners Open and Not White Flag) into a huge, continuous, single “performance piece.” And there is no cultural clash, so to speak, when this is done because of his consistency of approach. Threadgill’s music is essentially a huge chest full of Tinkertoys or Legos which he can mix or match at his whim and still come up with something valid and organic. And that is another reason (sorry, Henry!) why I can’t define his music as “classically oriented,” because no classical composer of any era has ever been able to do this.

Indeed, Threadgill has actually shifted and changed his composition style over the years. His earlier style, from the era of Too Much Sugar for a Dime, was much more funk-oriented and less complex, but he continued to morph and grow. He later took eight years off to create a new method of improvising in a group setting, which led to his most recent band, Zooid, named after a cell that is able to move independently of the larger organism to which it belongs. Interestingly, this change of aesthetic has led to a simplification of his composition methods. He now uses mostly “interval blocks” of three notes, each assigned to a different musician who is free to move around within them, improvising melodies and creating counterpoint against one another. This method may indeed sound classical to jazz critics who aren’t musically literate, but it is in effect an advanced version of the time-honored “chase chorus,” which has existed in jazz since the 1920s, brought into the digital era.

A final question, however, thus presents itself: Is Threadgill’s music all more or less similar? Does this ability to be interchangeable make it less individualistic? That’s a question every listener has to decide for him or herself, since everybody hears music differently. What I hear is a series of complex works that, because they lack definable melodic structure and because each of them is harmonically and rhythmically vague, can be tossed together like exotic salad ingredients into a bowl of iceberg lettuce. Threadgill’s music is a smorgasbord of different flavors and tastes that, like cilantro or pickled beets, completely change the flavor and texture of each musical salad. And you, as the auditor, may feel free to pour any flavor of mental salad dressing on to make it tasty for you.

— © 2016 Lynn René Bayley

Return to homepage OR

Read my book: From Baroque to Bop and Beyond: An extended and detailed history of the intersection of classical music and jazz

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/22/arts/music/henry-threadgill-review.html

Critic’s Pick

Review: Henry Threadgill’s Music From Two Perspectives

At Roulette, the composer and his ensemble performed a pair of multimedia sets based on a single composition.

- Henry Threadgill

- May 22, 2022

- NYT Critic's Pick

The most reductive observation I can provide about the composer and improvising multi-instrumentalist Henry Threadgill’s activity at Roulette this weekend is that he debuted some truly exciting new chamber music. Because he offered a lot more, too.

His multimedia programming stretched across Friday and Saturday, each evening running more than two hours. While the first set was titled “One” and the second — in playfully nonspecific fashion — was called “The Other One,” both contained takes on his composition “Of Valence,” for three saxophones, two bassoons, two cellos, along with a tuba, a violin, a viola, piano and percussion.

Threadgill, 78, has long deployed playfulness, ambition and unusual configurations in his work. His 1979 album “X-75 Volume 1” engaged a nonet of four basses, four winds and one vocalist.

In 2016 he won the Pulitzer Prize for music, for the double album “In for a Penny, in for a Pound,” which put the spotlight on Zooid — his late-career group that includes a tuba, acoustic guitar, cello, drums and Threadgill’s own flute and alto saxophone. Players in that ensemble improvise over quasi-serialized sequences of intervals (befitting a composer who in conversation is as likely to bring up Elliott Carter as Duke Ellington).

But this weekend’s shows were something new. The tuba player Jose Davila, the cellist Christopher Hoffman and pianist David Virelles are some of Threadgill’s closest collaborators, and capable of lending marching-band panache to his most contrapuntally complex music. Joining a larger group, their sound drew directly on the Zooid language — and some of its freer applications, as heard in Ensemble Double Up — while the multimedia cast a new light on this composer’s late style.

Those multimedia elements included collaged photographs of street debris that Threadgill took during the mass exodus from New York at the beginning of the pandemic, projected onto a screen; live recitations of prose written to accompany the images; looping, pretaped vocal choirs, with all parts voiced by Threadgill; and video essays that cut between footage of yet more chamber music and the composer’s droll sermonizing about smartphones and distraction.

Threadgill didn’t pick up an alto saxophone or a flute for live performance, though the video did feature him on bass flute. His instrumental contributions were limited to a pair of brief piano-plus-vocal moments, which were affecting in their vulnerability but a touch too tentative to come across as secure. (His pretaped choirs were more vocally assured.)

Otherwise, he focused on conducting the 12-player ensemble. On Saturday, they sounded as though in lock-step with his every surprise rhythmic feint — producing an obliquely danceable, straightforwardly joyous Threadgillian energy.

At one juncture, in the second hour of both nights, a string trio of the cellist Mariel Roberts, the violist Stephanie Griffin and the violinist Sara Caswell played staggered lines that seemed to tease traceable canonic patterning, but which remained melodically and rhythmically independent. It was tightly plotted, and resisted easy parsing; yet it didn’t sound much like Zooid’s zigzagging interplay.

A new sheen came from electronically manipulated cymbal tones, courtesy of the drummer Craig Weinrib. (The transducers he used to manipulate those metallic timbres were a tribute to the late percussionist Milford Graves, to whom the music was dedicated. The performances as a whole were dedicated to the pioneering critic and musicianGreg Tate, who died last year.)

These droning metallic timbres stood in subtle, ghostly contrast to the vibrato sound production of the string trio. Next, the tenor saxophonist Peyton Pleninger developed a solo from downward-plunging motifs in the strings. As he built up a frenetic, improvisatory energy from melodic cells, the string players began treading into extended technique, with scraping, at-the-bridge bowing and lightly plucked pizzicato.

Alongside Weinrib at his drum kit, some crying alto sax figures from Noah Becker inspired beautiful portamento lines from Griffin’s viola, as well as the entry of both bassoonists playing brooding long tones at first, before turning to peppery, explosive bursts. The gradual swelling of instrumental forces continued; on Saturday, this section contained a galvanic sense of swing, even through Threadgill’s successive, minute changes in tempo.

Sometimes, when you wanted the groove to keep going, a quickly arcing exclamation from the ensemble and surprise jolt in the rhythm would bring everything to a dramatic, unexpected finish — at which point Threadgill would, for example, go back to reciting sections of his prose against projections of paintings by his daughter, Nhumi Threadgill. Or he would sit near the stage while some video played, showing Henry Threadgill moving various talismans around a horizontally resting mirror. In tandem, a voice-over track delivered the composer’s observations about contemporary life.

But while the audience was invited to join the composer in grouchy irritation, this wasn’t the sole purpose of the vignette. Instead, this morsel harmonized thematically with Threadgill’s broader concerns about what we throw away too easily, including our attention. When his spoken text referred to rat populations and their proximity to outdoor diners, his pretaped vocal choir started to chant about something “crawling up my leg.” Such lighthearted moments had a way of balancing out the text’s more serious attributes — not least about the nature of inequality in New York, before and during the pandemic.

While the precise placement of videos and spoken texts changed from night to night, the musical sequence was largely the same. The advantage of Saturday’s set was its increased tightness — in the ensemble as well as in the multimedia transitions. If some form of this vibrant chamber orchestra music makes it to a recording, it should be accompanied by documentation of the experience in the hall (similar to the way a studio recording of Anthony Braxton’s opera “Trillium J” contained a video of its semistaged premiere, also at Roulette).

Henry Threadgill

Performed on Friday and Saturday at Roulette, Brooklyn.

https://50ftf.kronosquartet.org/composers/henry-threadgill

Program Notes

Sixfivetwo

(2018)

Henry Threadgill

(b. 1944)

Composed for

50 For The Future:

The Kronos Learning

Repertoire

Henry Threadgill composed Sixfivetwo, a 12-minute work for string quartet that includes opportunities for players to improvise. “The improvisational component is very important,” he said in an interview while describing his philosophy which guided the creation of this piece. “Kronos knows it's important and I know it's important. It's a shame that the classical concert world doesn't understand how important it is… Everything is about exploration. We get to where we are because of exploration. That's why improvisation is so important… We won't improve anything unless we have an improvisational approach to life.”

Composer Interview

Henry Threadgill discusses his musical background, his composition process, the piece he wrote for 50 for the Future, and more.

Artist’s Bio

Henry Threadgill

USA

Only three jazz artists have won a Pulitzer Prize. In spring

2016, Henry Threadgill joined Ornette Coleman and Wynton Marsalis as

Pulitzer laureates, when he was honored for In For A Penny, In For A Pound, the latest album by Zooid, his unconventional sextet (reeds, acoustic guitar, cello, tuba, bass guitar, drums).

“Unconventional” describes not just Henry Threadgill’s music, but his life.

Born

in Chicago in 1944, Threadgill grew up on the South Side, where parade

bands and the blues filled the air. He played percussion, then clarinet

in the Englewood High School band, but switched to sax at 16. Idolizing

Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, and Lester Young, he

adored Fritz Reiner’s Chicago Symphony and avant-classical composers

like Luciano Berio. He was 17 when he joined the Muhal Richard Abrams’

Experimental Band, which later expanded into the Association for the

Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM); there he found like-minded

musical explorers.

When bebop broke, most swing players thought

it was nonsense and claimed boppers couldn’t play “real” jazz. The

members of what became the AACM faced a similar reaction. So Threadgill

performed at dances and parades, joined polka and Latin bands, sat in

theater pits, and raised the roof in churches. He played the blues at

joints like the South Side’s Blue Flame with local heroes like Left Hand

Frank. All the while, he kept studying Berio, Stravinsky, and Debussy.

In

1967, he enlisted in the Army as a clarinetist-saxophonist, was

upgraded to composer-arranger, and then shipped to Vietnam to join the

4th Infantry Division Band. Injured during the 1968 Tet offensive on his

way back from guard duty, he was sent home and honorably discharged

with two campaign ribbons. He returned home for Chicago and reenlisted

with what was now the AACM, but in 1970 left for the perennial lure of

jazz’s Big Apple, New York City.

For the next 40 years, while

Threadgill challenged bedrock ideas about jazz, he settled into New York

City, where he lives with his wife. Around the East Village, he’s a

familiar face on the streets and in the cafes; old friends like Philip

Glass and Allen Ginsburg and total strangers alike engage him in

animated conversation. But he regularly decamped for months at a time to

Goa to recharge his creativity in a faraway, very different world. That

openness to ideas and experiences has always been vital to who

Threadgill is and how his music works. As Charlie Parker put it, “If you

don’t live it, it won’t come out of your horn.”

It was in the

East Village—long a seedy, tumultuous haven for outsiders of all

types—that Henry Threadgill launched the unconventional concepts that

led to his Pulitzer-winning art.

AIR (Artists In Residence), his

1970s trio, reimagined ragtime without the piano—a lot like dropping the

electric guitar from rock. His 1980s Sextett, pairing complex

compositions and dynamic soloists, combined heft and agility, and

birthed the “little big band” sound. In the 1990s, Very Very Circus

stepped deeper into unorthodoxy, with two electric guitars, two tubas, a

trombone/French horn, drums, Threadgill’s alto sax and flute, and

frequent add-ons. With Make A Move, a fluid lineup mixing French horn,

tubas, electric and acoustic guitars, and cello, he began exploring the

approaches to composing and improvising that led to Zooid. From 2000 on,

Zooid became his primary vehicle.

As a composer and improviser,

Threadgill sees artistic process and product as inseparable, the essence

of jazz. Duke Ellington and Charles Mingus strove toward the same goal.

Rooted in that history, Threadgill’s solutions have taken radical new

tacks. For Zooid, the Pulitzer committee explained, “A set of three note

intervals assigned to each player…serves as the starting point for

improvisation.” Zooid’s musicians make in-the-moment decisions about

structure, shaping the work-in-process. The unpredictable results are

jazz’s “sound of surprise” updated for the 21st century.

After

decades of probing music, cult status, and critical acclaim,

Threadgill’s Pulitzer Prize caps growing high-culture recognition: 2016

Doris Duke Artist Award; 2015 Doris Duke Impact Award; 2008 United

States Artist Fellowship; 2003 Guggenheim Fellowship. He is especially

proud of being the first black non-classical musician to get a Copland

House Residency Award. In July 2016, the annual Leadership Conference of

the Vietnam Veterans of America honored him with their Excellence in

the Arts award—a very special moment for the only Vietnam veteran ever

awarded a Pulitzer for music.

With his new lineups Ensemble

Double-Up (two pianos, two alto saxes, tuba, cello, and drums) and 14 or

15 Kestra: AGG, this consummate creative shapeshifter is upending

artistic expectations yet again.

Because of Henry's jazz background, improvisation is the big thing here. One of my favorite aspects of this piece is how much trust he puts in the performers. When a composer gives you the freedom to do whatever you want with the music, there's something magical that happens.

[1]http://dothemath.typepad.com/dtm/interview-with-henry-threadgill-1-.html

https://bombmagazine.org/articles/henry-threadgill/

Henry Threadgill by Frederic Tuten

The Pulitzer Prize–winning jazz icon shares his personal history, musical origins, and the evolutionary leap his music will take in 2022.

Winter 2022

Henry Threadgill performing at the Public Theater in New York City, 1980. Photo by Barbara Weinberg Barefield.

[BOMB's performing arts features are supported in part by Select Equity Group]

For a long time, I’d see him with books under his arm walking quickly to or from the Tompkins Square Library on Tenth Street, where, I would later discover, we both lived a block apart. He always seemed to be wearing a different and marvelous hat and, unusual for our neighborhood, a sport jacket, perfectly fitting and a modest color. He was cool to an inch of his life. It may have been several months before we exchanged smiles.

For many years, I had spent time in a café on the corner of Tenth and First Avenue. It was a home for many of us in the neighborhood, especially in the back room, where it was warm and cozy and you could spend the morning writing to the whine of the espresso machine. He’d be at a table reading, not staying very long, and over time we’d smile and nod.

One spring day, twelve or more years ago, we sat at opposite tables on the café terrace—on the sidewalk, that is, but I like the snobby European twinge of “terrace.” He wasn’t reading. I felt that I could no longer stand wondering who he was, and I finally approached him.

He was Henry Threadgill, a musician, he said. And I was me, a writer. We had never heard of each other. After a while of little stuff, I asked who his favorite writer was. “James Joyce, for Ulysses,” he said without hesitation. “And you, for music?” he asked.

“Bach,” I said, “for everything.”

We did not need more glue than that. Soon it was as if we had known each other forever and were picking up our conversation from the day before

It has always stayed like that.

A few weeks later, Henry invited me to his concert at the Jazz Gallery. Henry primarily plays saxophone and flute, but his talents extend to many other instruments, including his famous hubcaphone, which he built from pipes and salvaged hubcaps. That night, Henry shaved notes—as Cézanne did forms—into planes and made silences into music. I did not have to wait for the performance to be over to realize that he was one of the most original and brilliant musicians and composers of our time.

—Frederic Tuten

Frederic Tuten: Henry, we know each other, but I don’t know your history.

Henry Threadgill: I grew up in Chicago in the 1940s and ’50s. My siblings and I used to come home from Sunday service and play church. I loved going to my mother’s mother’s church because it was a sanctified church where people go off and speak in tongues and get wild and all of that. Afterward, at home, we’d put on little stage shows and pretend to be the preachers and the singers.

FT: Did you ever perform with a church as a musician?

HT: Yes, I did. I met this minister out of Philadelphia named Horace Sheppard who had a troupe of the most talented people. We traveled and played music for holy ghost people—holy rollers. It was just like Billy Graham, but it was all Black. Horace would tell me, “Henry, I want you to walk down the aisle and play ‘Just a Closer Walk With Thee’ on your alto sax. When you get to the front of the church, I want everyone to be screaming. I want you to tear the place up.” By the time I’d get to the pulpit, people would be up on their feet screaming. Horace would run down the aisle and leap onto the stage, doing the split, and say, “Ride on, King Jesus!” (laughter) This was not a show. These were serious people, taking spirits out of people and stuff like that.

FT For how long did you do that?

HT A couple of years, from around age eighteen to twenty-one. I got drafted in 1966, and my views on religion changed after I got to Vietnam and met the indigenous people there. The US military used the Montagnard people as scouts. They could smell the wind and listen to the ground and say, “That’s an elephant not a truck.” In their village, there were no doors, and, from what I understood, the word lock did not exist for them. You could leave everything you had on the ground, and it would rot before others would even look at it. That changed me. I said, If the Montagnard aren’t “civilized,” then I’m with them.

FT Tell me about your parents.

HT I was named after both of my grandfathers. I’m Henry Luther Threadgill. My mother’s father was named Luther Pierce. My father’s father’s name was Henry Threadgill. He was one of the few Black men who worked for Al Capone. He was a bootlegger and drove liquor all over the country, all over Canada. He made enough money that he moved from Arkansas to Chicago.

My father worked for the mob and was a professional gambler. He ran casinos and stuff like that. He used to pick me up in a brand-new Cadillac every year. Everybody wanted to dress like my father. He was the sharpest man in town. He got all the women. But my father also loved jazz. He opened up a casino, and while he counted the money, he would give me a handful of nickels and say, “Hey, Moon. Go play some music.” (My father never called me Henry. He called me Moon.) There was nothing but jazz on the jukebox because that’s all he listened to, and he wasn’t going to be anywhere that didn’t have it. I got hooked on jazz right away.

FT It was illegal gambling?

HT Yeah. He worked for the Italians. And there were other guys just like him. They had broken up with their wives, but they all took care of their children. I remember this period when my father was taking bets from a funeral parlor, downstairs where the morticians worked. The kids would be upstairs where they held wakes, and we’d be running through with balls and jumping up onto the coffins. And my father would come up and say, “What you all doing here? Don’t you disturb any of these bodies.” (laughter)

I remember getting in some trouble because I was stealing and stuff, and my mother made me go stay at my father’s. He told me, “Moon, don’t ever do anything that you don’t have any talent to do. You ain’t got no talent if you go to jail.” I had a half brother, Russell, who got to the top of Golden Gloves boxing and then went for the championship. There, this guy beat him so bad. My father went down and told Russell, “Don’t ever call me again to pick you up with you looking like this. You don’t have the talent for this.”

My father had been everywhere and done everything and had more women than anybody I’d ever seen in my life, but he and my mother were still the best of friends. He had somebody bringing him reefers when he was taking chemotherapy in the hospital. My aunt told me he was taking bets until the night he died. She said they found him with money in his hand. That man was too much.

Henry Threadgill at the University of Chicago, 1972.

Photo by Frank Gruber.

Sextet performing at the Public Theater in New York City, 1980. Pictured from left to right: Craig Harris, Olu Dara, and Henry Threadgill. Photo by Barbara Weinberg Barefield.

FT Growing up in Chicago, were you exposed to a lot of live music?

HT Around 1958, when we were living on the South Side, my friend Milton Chapman told me about a big concert at Englewood High School. It was Chet Baker and Stan Getz with Frank Rosolino on trombone. I remember it cost about fifteen cents to get in. I was thirteen years old and stood near the stage. I unzipped my mouth and said, “Fucking Stan Getz and Chet Baker, man!”

FT Was that the first live jazz you heard?

HT I had already been to a lot of concerts. My mother took me to see everybody—Duke [Ellington], Louis Jordan, Count Basie. They all played in the major movie theaters in Chicago, and we’d be up in the balcony. Until I was about six years old, I had to stand on my seat so I could see down to the stage. My mother was into the arts, and she knew that music was going to be my thing. I think she always knew it. She supported me all the way.

FT When did you say to yourself, “I want to be a composer, a musician”?

HT From the very beginning.

FT How old were you?

HT Three. I taught myself. I used to sit at the piano every day and wait for boogie-woogie to come on the radio. Somebody like Albert Ammons would come on, and I’d try to play along. My hands were small, so I struggled. But I got it, and in the process I learned how to play the piano. Then, I wanted to understand how music was made. I’d listen to Tchaikovsky, Serbian music, Beethoven, hillbilly music, everything on the radio, and ask, How does somebody create this?

When I got older, my mother had me take piano lessons from Mrs. Holmes. I thought I’d been sent to hell. She was a church lady in a little round hat, and she came with the Bible, a music book, and a ruler. I’d keep one eye on the music and one eye on her ruler. When you do that, you’re going to make a mistake, and—pow! So I stopped coming home after school. I’d stay out shooting marbles or climbing trees, watching my house until Mrs. Holmes left, and then I’d go home.

Polish music and the music from Serbia had a big impact on me. One of the biggest Polish communities outside of Poland is in Chicago. And one of the biggest communities of Serbs outside of Serbia is in Chicago too. I grew up listening to their music. And—besides the blues—I listened to hillbilly music, because we had a whole community of Appalachian people. (singing) “I’m so lonesome, I could cry.”

I knew that the white people were ashamed of the hillbillies, because they didn’t wear shoes and didn’t go to school. But that music was the real white American folk music, and they were denying it, just like they were denying the people who made it. Then you see what happened? After a while, it became the Grand Ole Opry, and then it became country and western music, and then just dollar signs after that.

FT So you first learned to play music on the piano. When did you start playing other instruments?

HT I liked the sound of the tenor saxophone from listening to Gene Ammons, Sonny Rollins, and Lester Young. I started playing at the end of my freshman year in high school, in about 1958, all the way into college. My music teacher had me learn clarinet, too, because in the big band era, all the saxophone players also had to play clarinet. Later, I became interested in playing the flute because of so many great flute players like Frank Wess, Sam Most, and Hubert Laws. Around 1969, I started playing flute seriously.

I remember when I was about fifteen, on Monday nights there were rehearsals at the Chicago School of Music. George Hunter used to run the band. He was a famous band director, and the band was full of successful musicians. They were all white. All men. They owned houses. They had boats. They would play in Woody Herman’s band, Les Brown’s band, and the Raeburn Boyd orchestra when they came to town. I walked in with my tenor sax one night, and they didn’t really pay me much attention. They kind of glanced, you know? Mr. Hunter looked at me, then he looked at everybody, and he said, “Okay, pull up 25, 36, 102, 509, and 700.” They had over a thousand arrangements. I hadn’t seen music written by hand before, only printed music. Mr. Hunter counted us off: “1, 2, 1-2-3-4.” Boom. I hit the first note and that was all. The notes were flying all over the place. I said, “What the shit? Oh man, this is bad.” Mr. Hunter took us into a slower piece. “1, 2, 3, 4.” Same thing. I only got the first note. He called his next piece. And I couldn’t get it. I was a teenager, and I was very self-conscious. I thought, They don’t like me because I’m a Black kid, so they’re just washing my ass out. But it wasn’t true. I just wasn’t at their level as a musician.

I put my sax in my case and slammed it shut. The whole place got quiet. When I left, I slammed the door so hard I almost knocked the glass out the window. I got home, stormed in the house, found my mother and my grandmother, and told them, “I’m moving to the basement.” I covered up all the windows and went downstairs to practice. I was devastated, completely fucking emotionally devastated. I didn’t think I was worth shit. They used to bring my food to the door and leave it on the floor. Kids would come around saying, “Henry doesn’t like us anymore. He never comes out to play.” My whole spirit had been broken. I had to find out what I was called to do in my life.

I started living in the basement probably in June. School started in September. The first Monday after that I went back to the rehearsals. Again, they didn’t pay me much attention, but I got my music out. “Pull up 19, 44, 16, 108. And 1, 2—” Boom. When they took off, I was right with them. I missed some stuff, but I had figured out how to stay with it even if I messed up. I heard these white guys say, “The kid is alright, huh?” (laughter)

If I had gone back there and failed again, that would have been too much. My teachers had told me: You haven’t failed when you make a mistake. You have to stumble forward. If you let a mistake register on you physically and emotionally, you’ll lose your position. But if you just stay with the program, you’ll be back in the saddle. You have to keep riding. Don’t let the horse throw you. Later, when they come back and play that piece again, you can say, “I remember you. You threw me before, but I’ll get you this time.”

FT Tell me about the hubcaphone. How did you make your own instruments from hubcaps?

HT Around 1970, I was driving down Maxwell Street in Chicago, and there was a place that sold nothing but hubcaps. I made a rack with metal pipes so that the hubcaps could lay on top. When I started playing it, the whole thing fell over. I didn’t even know how to play it. You had to dance to play it. About that time, I left Chicago and went to Amsterdam, where I lived with the painter Quan Tilting. He was way out there as a painter. He had built a platform with canvases on two sides. He would take two or three brushes in each hand, and whirl and jump and spin through the middle of the platform. I started practicing his painting movements. And that’s how I figured out how to play the hubcaphone.

FT How did you start your own group? For example, how did you start Zooid?

HTZooid is the most recent group. My first group didn’t even really have a name. It was just the Henry Threadgill Ensemble. And then I had a group doing music and theater happenings. I started working with avant-garde theater in the early ’70s. I did a couple of shows with Arnold Weinstein, worked in guerrilla theater in San Francisco, and with Shirley Mordine’s dance company. And then came this theater director who wanted me to use Scott Joplin rags and my own music for this production. The theater company had moved into this hotel, The Diplomat, where you had country western people living, a former hillbilly star, and a woman who had been in theater and was still dressing up in the same costumes she used to wear when she performed on stage, like she was reliving the past. The Italian mob had control of the liquor store, and behind it was a gambling place. The people in the theater company studied the weird characters in there, and then they wrote a script called Hotel Diplomat. When the mob came and threatened the director, Don Saunders, he changed the name to 99 Rooms. That was the birth of my group Air, and after that, it was history. Air was the group that was famous. We just took off. The critics demanded that we be recorded. We didn’t have to ask anybody for a recording contract.

FT That’s almost unheard of.

HT I know. That was unbelievable. We came to New York from Chicago in ’75, and I later started another group called the Sextet—that was a seven-piece group. I kept that for a long time. We did a lot of recording and traveled all over Europe and other places. Then I had a five-piece group called The Windstream Ensemble. I did a lot of theater and dance work with that group at the Public Theater and other places. Then came Very Very Circus, which everybody knew all over the world. After Very Very Circus, came Make a Move. After Make a Move came Zooid. I’ve had that group for about fifteen years. I also had a dance band called the Society Situation Dance Band. That band was never recorded, and it was never supposed to be. It was for live performances where people could dance to it.

FT You’ve said you’re a different person with each instrument you play.

HT That’s right. I have to create a solo sound. There’s a lot of flute players, and I don’t want to sound like them. There’s a lot of alto sax players, and I don’t want to sound like them either. I’ve developed my own voice, and I use a different approach when I’m moving from one instrument to another. When I’m changing instruments, it should be another person coming to you. You just heard me coming to you as Maria Callas, now I’m Beverly Sills or Madonna or Beyoncé. (laughter)

FT What we’re really talking about is your drive to go forward, not to continue doing the same thing that you did well and that you got money for, but to do something that you want to do.

HT That’s in my nature. I feel I will literally die if I don’t go forward. Going back has always been a mistake for me, like when I went back to smoking or went back to this woman I had a bad time with. Why did I go back there?

FT When I was getting to know you, you told me Ulysses was one of your influences. I thought that was a pill.

HT I don’t get a lot of my information from music anymore. It comes from dance. It comes from theater. It comes from film. It comes from literature. It comes from painting. It comes from photography. I only listen to music for enjoyment. I’ve been looking at Albert Oehlen’s paintings, studying them for days, looking at their rhythmic possibilities. When I’m looking at a photograph, I’m looking at the light, at the background and middle ground and foreground. I can’t even think about that in terms of most music, you know.

FT Henry, did you go to college?

HT Of course. I started out at Woodrow Wilson Junior College. Then I went to University of Chicago for a while, then Manhattan University in Kansas. Eventually, I came back to Chicago, where I went to the American Conservatory of Music. I graduated in 1974, but I was a student there for about eight years.

FT That’s amazing.

HT I didn’t go to school to get a degree. I went to school to take every course that they had. I kept changing majors so I wouldn’t have to get a degree. I said, “You think I’m going to let you give me a degree in four years? You offer a hundred courses but I’ll have only taken fifteen of them. Keep your degree. I want every piece of information you got.“

Henry Threadgill. Photo by John Rogers. Courtesy of

FT Were you playing music and going to school at the same time?

HT Yeah. It was very difficult. I had trouble with a lot of professors at the conservatories. One professor said I’d never learn anything because I wouldn’t do what he wanted. I said, “I know you want me to prove that I can write a concerto. But I’ve analyzed every piece of music and I got the highest grades. Why do I need to prove it?” The dean didn’t know what to do with me. The great Stella Roberts was supposed to be retiring, but she said, “I’ll take him.” And she became my composition teacher.

Stella Roberts has been written out of history. When she was eighteen, she was accepted to study with Nadia Boulanger in Paris. So she went to Paris on a boat. She was a little country girl who didn’t know anything about reefers, nothing about gay people. But then she sailed to France with Man Ray, Virgil Thomson, and Aaron Copland, and went straight to Gertrude Stein’s. (laughter) And who turned up? Picasso. She met Alice B. Toklas, Stravinsky, everybody. She was in that group, but she was a woman, and women just weren’t getting credit

You know why Stella Roberts was such a great teacher? Because she didn’t teach me anything.

Generally, when you walk away from great people, they’ve left their fingerprints all over you. You become the little Roy Lichtenstein and the little Mozart and the little Charlie Parker. But Stella Roberts was different. I’d come in and she’d be sitting there at the piano. I’d pull out my music and she’d put it on the piano. There was always a little spot that could be better or cleaned up, but would she comment on it? No. She would never criticize or even point it out. She knew I knew where it was. Once, she looked out the window and said, “Come here, Henry.” I helped her up, and we went to the window. She asked me, “You know who designed that building over there?” I didn’t. She said, “That’s Frank Lloyd Wright. Look in my cabinet, in the architecture section, and find the book on Wright and take it home.” The next time I came back, she said, “Do you know Ulysses?” I said no. She said, “Look in the cabinet.” We never discussed any of the books. I was like, Are you fucking kidding me? What does this have to do with what I’m doing? I’d try to figure out what I was doing musically that was parallel to the books—how they could inform me about the mistakes I made in my music. But even if I didn’t figure it out, I’d learn other things about literature and architecture. She took me back down the course of reeducation in those departments. What did Stella Roberts show me? She taught me to be the teacher.

FT She taught you how to teach yourself.

HT Exactly.

When I play music, I don’t know how it will touch the listener. There’s materiality in literature, painting, and photography, but not in sound.

FT Well, even if you can’t touch it, music vibrates in your body.

HT But it vibrates differently in each person’s body.

FT That’s true for painting too, though. Each person sees what he or she sees. We don’t know what they see.

HT But where the painter is trying to get something on the canvas, I’m trying to get off the canvas. The musical score is a form of calligraphy. You have to lift the music off the paper and put it in the air. It’s not like the word acoustic. You pronounce it the same way all the time. Acoustic is acoustic is acoustic is acoustic. But music is a matter of idiom and style and different folkways.

I want to enjoy music the way the novice enjoys it, and not because I have more technical information than somebody else—that’s not enjoying music because then you’re explaining it, and you shouldn’t have to explain music.

I don’t play down to people; I play up to people. If you play down to people, you don’t have respect for people. I have a high opinion of people, so I play up to people.

FT I write for the kind of reader that wants to read me, and I hope that they like it.

HT: There lies the big difference between literature and music. Words are definite. Notes have no meaning at all. Music has no meaning at all. Songs with people singing are suggestive at best. If you take away the words, what does it mean? Each person will get something different.

My objective with Zooid, and with all of my groups, is to make music. I take what I write to the rehearsals, and if somebody plays it wrong, I say, Wait a minute. Go ahead and play that wrong again, because you did something right. You know what I’m saying? A rehearsal is an exploration. I don’t care what I’ve written. In rehearsal, I throw it away or turn it upside down. I move this over here and that over there. I don’t care because my objective is to make music.

FT That’s all that matters.

HT Years ago when I was working for the University of Chicago hospital, I learned something about the value of making mistakes.

FT What were you doing there?

HT I collected tests the doctors ran on patients and took them to the labs. I was about nineteen or twenty. I was working full-time and going to school part-time, trying to save enough money to go to the conservatory in the fall. Eventually I got caught not being in school full-time, and got drafted.

One day, a guy brought me down to the research lab, where they had animals and were growing things in petri dishes. This guy told me it’s only through mistakes that we progress. All great discoveries have come through mistakes. Without mistakes, we’d remain in the same place. That’s how I compose music. You try to come up with the best solution, the best order for the music to be taken in by the musicians. But when you get into rehearsal, the work, the exploration, really begins.

FT What are you working on now?

HT I’m getting ready to make another turn with my work. I’ve been lucky in my musical life; I only change when I find the material to make a change. I’ve now found a way to advance rhythmically through Morse code. That communication system is dot–dash, but dot–dash is not enough. Two notes are considered a dyad. You need three elements, because harmony is always three notes. So you need dot–dash–dot. There’s a short phrase, and there’s a long phrase, and then there’s another short phrase; Morse code uses letters, but I’m saying those are phrases.

FT Is that a rhythmic system?

HT It’s rhythmic design.

FT How does that translate into performance?

HT Here, let me show you an example. I’ll write, “Mary hates Fred. Fred doesn’t care what Mary’s opinion is. Mary tells Fred to fuck off.” Can you see this? “Mary hates Fred.”

FT Oh, good. I’m glad I found out.

HT That’s short. Then you say, “Fred doesn’t care what Mary’s opinion is.” That’s long. “Mary tells Fred to fuck off.” That’s shorter. Short, long, short. You following me? It’s rhythmic design. That’s what I’ve taken from Morse code.

FT How does the improvisational aspect fit into the design?

HT I’m going to attach it to the body, to the musician’s own meter. Nobody has done this. It is the new frontier. This is going to take me all the way.

FT Okay, so explain.

HT I will record the heartbeats of four musicians for twenty seconds each, and then put that in a continuous loop so they can keep hearing it.

FT They’re listening to their heartbeat as they’re performing.

HT Right. And then what they’ll play will be both written and improvised, according to what they hear coming from their body. The improvisation has guidelines, and a lot of that is the rhythmic design. Or they have to stay within parameters: I’ll tell one musician that the only intervals they can play are a minor second, a major third, an augmented fourth, and a sixth. I’ll tell another musician, “You can play a major second, a minor third, a fifth, and a seventh.” Those are the only intervals they can use to play a short phrase, a long phrase, and then a short phrase.

It’ll be my job to make it work, to create the synthesis. I’ll examine the differences between these four musicians’ heartbeats. Is it like finding the medium or the mean? What is the difference between my heartbeat and your heartbeat? I’ll be making decisions coming out of the organic aspect of each person’s body. It’s not just made up. It’s real, because it’s you. It is you.

FT It’s biology as music.

HT Yeah. And, you know how clothing is made in a factory? One person makes this part, another person makes that part.

FT An assembly line.

HT But it’s not going to fit together like a normal shirt. My hand might be coming out my knee, and my foot might be coming out my ear. (laughter) It’s still my body. It’s still the same body parts. Only the positions have changed.

FT Like a Picasso painting.

HT Exactly. It worked because nothing had changed. Everything was just reassembled.

This is all going to be at Roulette, right down the street from the Brooklyn Academy of Music, for two days. May 20 through 21, 2022. It’s a multimedia piece, starting with films that I made a couple of years ago in the Tilton Gallery and Luhring Augustine. The performance will open my film, Plain as Plain in Plain Sight. The second night will open with my other film Plain as Plain, but Different.

I’ve written a book called Migration and the Return of the Cheap Suit, and during the performance, the text and photographs from the book will be projected on a screen. The first part of the book is about people who left the city willingly. The second part of the book is about people getting evicted. I took the photographs last year when this COVID-19 thing hit us, and all the yuppies were moving out of the East Village. Every day, I’d go out for my evening walks and see all this stuff the yuppies were leaving in the street: fabulous women’s shoes, $4,000 speakers. It was money in the street. There were moving trucks everywhere.

At Roulette, I’ll project the pictures I took of all that onto the screen. Then I’m going to perform the text. I’ll read some to you, and how I might improvise it: “Now we sing the coming of empty space, the unwanted shifting.” Now, for the performance: “Now we sing the coming of empty space. It’s not about what’s crawling up my leg, or something wet going down my back. Empty space. It’s about the unwanted, unwanted, unwanted, shifting.” I’ve also been working on synthesized choruses. I’m going to sample my voice to create a choir effect. Solo, duet, or trio.

FT Henry, this is an evolution for you, right?

HT Yes, it is.

FT You’ve built your work over all these years, and now you see another thing. You’re in a state of grace.

HT I’m lucky. I’ve been fortunate with this. I’ve always feared that a day might come when there won’t be another move for me on the chessboard. I started out doing one thing in music and I took it as far as I could go.

I didn’t change for novelty’s sake. I changed when I used up all the information I had. Then I had new ideas that took me to the next place. That’s my musical history.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Frederic Tuten is the author of five novels; a collection of short stories, Self Portrait: Fictions; and My Young Life, a memoir. His fiction, art, and criticism have appeared in Artforum, BOMB, the New York Times, Vogue, Granta, Harper’s, and elsewhere. Tuten is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship for Fiction and the Award for Distinguished Writing from the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

jazz

free jazz

chicago

saxophone

HENRY THREADGILL IS THE 2016 RECIPIENT OF THE PULITZER PRIZE IN MUSIC

http://soundprojections.blogspot.com/…/henry-threadgill-b-f…

Saturday, December 12, 2015

HENRY THREADGILL (b. February 15, 1944): Legendary, iconic, and highly versatile musician, composer, arranger, orchestrator, conductor, ensemble leader, and teacher

HENRY THREADGILL IS THE 2016 RECIPIENT OF THE PULITZER PRIZE IN MUSIC

http://soundprojections.blogspot.com/…/henry-threadgill-b-f…

Saturday, December 12, 2015

HENRY THREADGILL (b. February 15, 1944): Legendary, iconic, and highly versatile musician, composer, arranger, orchestrator, conductor, ensemble leader, and teacher

From the album OPEN AIR SUIT (1978) by the trio ensemble known as AIR

"Card Two: The Jick Or Mandrill's Cosmic Ass"

(Composition and arrangement by Henry Threadgill)

AIR is:

Henry Threadgill - alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, baritone saxophone, flute

Fred Hopkins - bass, maracas

Steve McCall - drums, percussion

VIDEO: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V4St23cJN5A

<iframe width="420" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/V4St23cJN5A" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Henry Threadgill (Air) - Card Two: The Jick Or Mandrill's Cosmic Ass

Henry Threadgill: Alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, baritone saxophone, flute

Fred Hopkins: Bass, maracas

Steve McCall: Drums, percussion

Henry Threadgill - "Bermuda Blues" from the 1986

Threadgill/ Hopkins/ McCall - "Keep Right On Playing Thru The Mirror Over The Water"

(Composition and arrangement by AIR)

Henry Threadgill/ Fred Hopkins/ Steve McCall - "Live Air", Black Saint, BSR 0034 CD, 1980.

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/19/arts/music/henry-threadgill-pulitzer-prize-penny-pound.html?_r=1

Music | Critic’s Notebook

At Last, a Box Henry Threadgill Fits Nicely Into: Pulitzer Winner

by NATE CHINEN

April 18, 2016

New York Times

Henry Threadgill, who on Monday was awarded this year’s Pulitzer Prize for music, is a composer and bandleader of intense, unyielding originality, nobody’s idea of a compromise. An alto saxophonist and flutist with a distinguished career in the post-1960s American avant-garde, he has amassed a body of work with its own functional metabolism, perpetually humming in a state of flux. He has certain affinities with, but no particular allegiance to, the jazz tradition.

“In for a Penny, in for a Pound,” Mr. Threadgill’s award-winning album, is a suite-like composition released on two discs by Pi Recordings last year. It’s an intricate and thoroughly enigmatic piece of music, but above all it stands as a showcase for his longtime flagship, Zooid. (The group takes its name from a biological term for a cell that is capable of movement independent of its parent organism.) From the first moments of the title track, which opens the album, you experience a distinctively slanted feeling, the byproduct of an unstable but carefully coordinated form of counterpoint. The music has formal rigor and forward pull, but it doesn’t provide an orienting framework, or any clear distinctions between composition and improvisation.

When Mr. Threadgill got the call on Monday that he had been awarded a Pulitzer, he was beyond surprised.

“I was speechless,” Mr. Threadgill, 72, said in a telephone interview. “I said, ‘What for?’”

Asked how he categorized his music, or where it falls on the jazz-avant-garde continuum, he demurred.

“I create what I create,” he said. “When I’m fortunate enough to create a work, that’s the end of it in my mind. Where it’s placed, where it goes, what people say about it, that is really not my department. I’m in Lingerie, I’m not in Hardware, you know?”

If you do call him a jazz composer, he is the third to be awarded a Pulitzer in the history of the awards; Wynton Marsalis was awarded for his oratorio “Blood on the Fields” in 1997 and Ornette Coleman was awarded for his album “Sound Grammar” in 2007.

Mr. Threadgill is a longtime resident of the East Village. He has been a musician of multidimensional interests since his youth in Chicago: He had formative experience in marching bands and with a traveling Church of God evangelist, before joining the first wave of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. In the mid-1970s he formed a trio, Air, that was one of the most celebrated groups to emerge from that cohort. (His other groups have included the Henry Threadgill Sextet and Very Very Circus.)

Last year, in addition to releasing his own album, he took part in a 50th anniversary celebration for the association, presenting a new chamber piece and appearing on “Made in Chicago,” an ECM album featuring his fellow members Muhal Richard Abrams on piano, Roscoe Mitchell on saxophones and Jack DeJohnette on drums.

That’s a council of elders, with longstanding bonds between them. “In for a Penny, in for a Pound” puts Mr. Threadgill more in a position of authority, though he wields it lightly. The album features the extravagantly sensitive interplay among his band mates: Liberty Ellman on acoustic guitar, Jose Davila on trombone and tuba, Christopher Hoffman on cello and Elliot Humberto Kavee on drums. Zooid has been a working unit for more than 15 years, its rapport honed through extensive workshopping and rehearsals.

During a series of conversations in 2009, members of the ensemble described Mr. Threadgill’s methodology as intimidatingly complex but also deeply intuitive. He explained it as “a serial intervallic language” ruled partly by mathematical principles and inspired, obliquely, by the 20th-century composer Edgard Varèse. But part of the magic in the music is that its predetermined structures give way, unpredictably, to various sorts of spontaneous digression.

“For people who listen to jazz music in the traditional sense, it’s easier to follow the form if you know the piece,” Mr. Ellman said. “But Henry isn’t really concerned with that formality. In this music we have a lot of through-composed things, and we might play one section in a piece, and there might be room for a solo in that particular section, or there might be two or three solos before we go back to the written material. Every piece has a completely different form.”

Mr. Threadgill wrote four concerto-like movements for “In for a Penny, in for a Pound,” each designed to spotlight a member of Zooid. (Mr. Ellman’s is “Unoepic (for guitar).”) But each piece, and the album’s two other tracks, is as likely to feature digressions from someone other than the featured improviser.

He happens to have another album out as of this month: “Old Locks and Irregular Verbs,” featuring the new group he calls Ensemble Double Up, whose members include Mr. Hoffman and Mr. Davila. Divided into four parts, it’s another statement of grave but wriggling purpose, just as easy to picture in Pulitzer contention. What that illustrates, among other things, is the abundance of Mr. Threadgill’s restless creative energy. Becoming a Pulitzer winner should be welcome validation for him, but it seems unlikely that he’ll be resting on any laurels.

Michael Cooper contributed reporting.

Sir Simpleton

"Sir Simpleton"X-75 Volume 1 is the debut album by Henry Threadgill released on the Arista Novus label in 1979. The album and features four of Threadgill's compositions performed by Threadgill with Douglas Ewart, Joseph Jarman, Wallace McMillan, Leonard Jones, Brian Smith, Rufus Reid, Fred Hopkins and vocals by Amina Claudine Myers. The Allmusic review by Brian Olewnick states, "Henry Threadgill's first album as a leader immediately plunged into experimental waters. He utilized a nonet the likes of which had certainly never been heard before and probably not since... Threadgill's massive talent for mid-size band arrangements is immediately apparent... As of 2002, X-75, Vol. 1 was unreleased on disc and, even more disappointingly, there was never a "Vol. 2." But Threadgill fans looking for a link between Air and his Sextett owe it to themselves to search this one out".

Track listing

All compositions by Henry Threadgill

- "Sir Simpleton" - 6:26

- "Celebration" - 13:21

- "Air Song" - 10:21

- "Fe Fi Fo Fum" - 13:00

Recorded at CI Recording Studios, New York City on January 13, 1979

- Henry Threadgill - alto saxophone, flute, bass flute

- Douglas Ewart - bass clarinet, piccolo, flute

- Joseph Jarman - soprano saxophone, flute

- Wallace McMillan - piccolo, alto flute, tenor saxophone

- Leonard Jones - bass

- Brian Smith - piccolo bass, bass

- Rufus Reid - bass

- Fred Hopkins - bass

- Amina Claudine Myers - vocals

The Henry Threadgill Sextet – "When Was That?"

Olu Dara - cornet

Craig Harris - trombone

Henry Threadgill - alto, tenor saxophone, clarinet, flute, bass flute

Brian Smith - piccolo bass

Fred Hopkins - bass

Pheeroan akLaff - drums

John Betsch - drums

Tracklist:

1 Melin - 00:00

2 10 To 1 - 03:40

3 Just B - 15:10

4 When Was That? - 19:35

5 Soft Suicide At The Baths - 29:57

All compositions by Henry Threadgill. Recorded at Sound Ideas Studios, NYC, on September 30 and October 1, 1981.

About Time Records – 1982.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/henry-threadgill-9-plus-essential-albums

Building a Jazz Library

Henry Threadgill: 9 Plus Essential Albums

PHOTO: Henry Threadgill (center) Courtesy Julie Gulenko

PHOTO: Henry Threadgill (center) Courtesy Julie Gulenko

by Steve Cook

July 25, 2022

AllAboutJazz

The beauty of Henry Threadgill is how he upends the idea that listeners need to 'get' music to enjoy what they hear.

More people should listen to the music of Henry Threadgill. Without any actual statistics at hand, it's safe to say that one could consider his market to be niche. Yes, many jazz fans know him as a long-established creative force. He even won a Pulitzer. But he probably does not ring a bell among the many more who know jazz through legacy artists with curated, major label back catalogs or newer performers with huge-selling breakthrough albums—often, but not always, vocalists. It should not be this way as Threadgill's music is uniquely exciting and just plain fun.

Thankfully, we live in a relative golden age to listen to him. Albums by Threadgill and his ensembles have been released by more than ten labels, most of them small independents. With disparate entities involved with their care, building a jazz library with his albums used to require a patient, piece-by-piece approach. Scouring used records stores and crate digging do have a certain appeal. Besides the episodic sense of accomplishment it brings, the process can take you to new places and introduce you to new people and friends. But one would not expect such resolute determination from those yet to sign on for all things Threadgill. With the benefit of specialty reissues, online retailers, streaming services and digital sales platforms, collectors and the curious can now get their hands and ears on most of the albums mentioned below in one fashion or the other with relative ease. Any future Threadgill completists inspired by this BAJL entry may need to make periodic checks of Discogs and Ebay to fill some gaps, but Threadgill's work is now remarkably discoverable compared to an earlier time.

Threadgill's discography has many doors through which to enter. All of them and where they go merit attention. With this being said, to present 9 Plus Essential Albums intends neither to snub nor to vacillate. Given his deliberate playfulness with words and numbers, it would seem out of place to make a Top Ten, too. Readers are invited to share their own Threadgill "essentials" in the comments section below. Preferred outlets and stratagems for building a Threadgill library are heartily welcomed.

Zooid

Poof

Pi

2021

Zooid

In for a Penny, In for a Pound

Pi

2015

Threadgill's work with his longest running band, Zooid, provides as appropriate a place as any to introduce people to him. For as much as he seems to change, Zooid could be just a new variation on his long-running interest in jazz bands as classical chamber groups—or maybe it should be the other way around.