AS OF JANUARY 13, 2023 FIVE HUNDRED MUSICAL ARTISTS HAVE BEEN FEATURED IN THE SOUND PROJECTIONS MAGAZINE THAT BEGAN ITS ONLINE PUBLICATION ON NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

THE 500th AND FINAL MUSICAL ARTIST ENTRY IN THIS NOW COMPLETED EIGHT YEAR SERIES WAS POSTED ON THIS SITE ON SATURDAY, JANUARY 7, 2023.

BEGINNING JANUARY 14, 2023 THIS SITE WILL CONTINUE TO FUNCTION AS AN ONGOING PUBLIC ARCHIVE AND SCHOLARLY RESEARCH AND REFERENCE RESOURCE FOR THOSE WHO ARE INTERESTED IN PURSUING THEIR LOVE OF AND INTEREST IN WHAT THE VARIOUS MUSICAL ARTISTS ON THIS SITE PROVIDES IN TERMS OF BACKGROUND INFORMATION AND VARIOUS CRITICAL ANALYSES AND COMMENTARY OFFERED ON BEHALF OF EACH ARTIST ENTRY SINCE NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE WHERE THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND ‘LABELS' (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) LINKS ARE LOCATED. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com

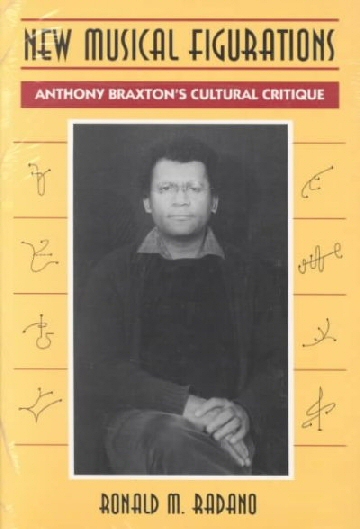

PHOTO: ANTHONY BRAXTON (b. June 4, 1945)

[The following excerpt is taken from the Panopticon Review archives and was originally posted on Mr. Braxton's 68th birthday on June 4, 2013]:

"Going Outside the Categories That Are Assigned To Me": The Profound & Visionary Life, Art, and Work of Anthony Braxton (b. 1945)-- Musician, Composer, Philosopher, Teacher, Artist, and Public Intellectual

ANTHONY BRAXTON

(b. JUNE 4, 1945)

New Musical Configurations:

Anthony Braxton's Cultural Critique

Hardback/Cloth

336 Pages

University Of Chicago Press, 1993

"New Musical Figurations" exemplifies a dramatically new way of configuring jazz music and history. By relating biography to the cultural and musical contours of contemporary American life, Ronald M. Radano observes jazz practice as part of the complex interweaving of postmodern culture--a culture that has eroded conventional categories defining jazz and the jazz musician. Radano accomplishes all this by analyzing the creative life of Anthony Braxton, one of the most emblematic figures of this cultural crisis.

Hardback/Cloth

336 Pages

University Of Chicago Press, 1993

"New Musical Figurations" exemplifies a dramatically new way of configuring jazz music and history. By relating biography to the cultural and musical contours of contemporary American life, Ronald M. Radano observes jazz practice as part of the complex interweaving of postmodern culture--a culture that has eroded conventional categories defining jazz and the jazz musician. Radano accomplishes all this by analyzing the creative life of Anthony Braxton, one of the most emblematic figures of this cultural crisis.

"I am viewed as the Negro who has gone outside of the categories assigned to me."

—Anthony Braxton

"I am interested in the study of music and the discipline of music and the experience of music and music as an esoteric mechanism to continue my real intentions."—Anthony Braxton

"I'm seeking to have an art that is engaged as a way for saying, 'Hurray for unity'."—Anthony Braxton

“For me the most basic assumption that dictated my early attempts to respond to creative music commentary was the mistaken belief that western journalists had some fundamental understanding of black creativity—or even western creativity—but this assumption was seriously in error.”―Anthony Braxton, The Tri-Axium Writings

"I know I’m an African-American, and I know I play the saxophone, but I’m not a jazz musician. I’m not a classical musician, either. My music is like my life: It’s in between these areas."—Anthony Braxton

"All great artists are beyond category."—Duke Ellington

All,

The aesthetic, social, and cultural history of music generally over the past century in the (so-called) 'Western world' not only represents an enormously complex, complicated, and contentious creativity and innovation but is rooted in and deeply dependent upon a vast array of generic and idiosyncratic styles, traditions, genres, idioms, methodologies, and expressive identities. These structural, spiritual, and analytical modes of music making encompass a very broad and expansive territory of human concerns, issues, and expectations within the larger society, as well as profound individual emotional and psychological needs and desires that are simultaneously embodied and represented by these (creative) musical acts in public concert and collaboration with others (both like-minded and opposed). These conscious and subconscious attempts to engage, enhance, critique, celebrate, and transform society and culture via the immense environmental forcefield and sustained focused power of sonic intervention and expression in all of its many permutations and elliptical methods (whether they be encrypted or encoded in the formal "traditional/conventional" vocabularies and systems of melody, harmony, and rhythm or via other paths of producing and reproducing sound constructs), constitute what is "meant" by the term "music" in our time (zone).

Thus the 'classical' and 'popular music' traditions, styles, conceptions and forms of composition and improvisation (be they described/defined by the imposed advertising and thus commercial labels of "Jazz", "blues", rhythm and blues", "pop", "gospel", "funk", "hiphop" etc. et al) have served as a largely deceptive yet accepted means of identifying and classifying what sound formations can and "should be" used to convey these powerful sonic messages within the institutional structures and strictures established by the self appointed arbiters of musical taste and consumption. However there has always been throughout this highly volatile, contradictory, and conflicted history a significant number of sonic pioneers, adventurers, and creative activists who have openly challenged this status quo and have educated us all to the power, beauty, and necessity of asserting alternative notions of what we can and choose to do with our collective (and individual) sonic legacies and inheritances. No matter what specific or general "fields" these 'planters of sound' happen to harvest we not only know their names (they are indeed legion!) but we absorb, inhabit, embrace, and greatly benefit from their creative and visceral gifts embodied in the art and science of their sound. In the U.S. and beyond they have come from every cultural, "ethnic", spiritual. and gender enclave on earth and have been instrumental (get it?) in openly confronting and transforming our very lives. Many sterling examples abound: Armstrong, Ellington, Coleman, Ives, Stockhausen, Henderson, Morton, Schoenberg, Monk, Glass, Stravinsky, Stitt, Gordon, Silver, Washington, Holiday, Basie, Sinatra, Hendrix, Parker, Sun Ra, Fitzgerald, Vaughan, Carter (Elliot, Benny, and Betty), Franklin, Mayfield, Marley, Fela, Jackson (Mahalia and Michael), Partch, Varese, Gershwin, Hindemith, Bartok, Dylan, Wilson, Cowell, Prince, Berry, Davis, Coltrane, Powell, Rollins, Blakey, Shorter, Tatum, Webern, Copland, Hancock, Williams, Stone, Webster, Young, Robeson, Gaye, Wonder, Taylor, Robinson, Warwick, Johnson, Bacharach, Wolf, Hooker, Hopkins, Waters, James (Elmore and Etta), Khan, Mitchell (Blue and Roscoe), Smith, Abrams, Ayler, Mingus, Dolphy, Gillespie, Xenakis, Cage, Kirk, Brown (James and Clifford), Shepp, Roach, Lincoln, etc. et al...

Thus it is no surprise that one of the major names in this grand pantheon (and has been now for nearly 50 years!) is Mr. Anthony Braxton who tirelessly works and creates within an immense omniverse of influences, inheritances, and legacies culled from a colossal living archive of sound in all its many dimensions and in all the worlds he and we inhabit and live in. We owe Anthony and his many legendary forebears, contemporaries, colleagues, and peers a very deep and lasting debt that can only truly be repaid by listening...Happy birthday Mr. Braxton and to the rest of us: ENJOY…

The New England Conservatory (NEC) awarded two honorary Doctor of Music

degrees to composer and keyboardist Bernie Worrell and composer,

saxophonist, clarinetist and pianist Anthony Braxton at the

Conservatory’s 145th annual Commencement Exercises on May 22.

A 1997 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductee, Worrell, 72, graduated from NEC in 1967, and is a founding member of the funk-rock collective Parliament-Funkadelic. Worrell contributed to the Red Hot Organization’s 1994 album Stolen Moments: Red Hot + Cool, a TIME magazine Album of the Year. His 2013 song “Get Your Hands Off” received the Independent Music Award for Best Funk/Fusion/Jam Song. Worrell received a Lifetime Achievement Award from NEC in 2010. In 2014 he released Elevation: The Upper Air, a solo piano album.

Braxton, 70, released his first album, 3 Compositions of New Jazz, in 1968, and has collaborated with countless artists on dozens of albums, including Chick Corea, whose quartet Circle he joined in 1970. Known as an influential music educator, Braxton joined the faculty of Wesleyan University in 1990, and retired in 2013 as the John Spencer Camp Professor of Music. He received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1981, a MacArthur Fellowship in 1994, the 2013 Doris Duke Performing Artist Award and the 2014 Jazz Master Award from the National Endowment for the Arts. He was last featured in JT in 2014.

A 1997 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductee, Worrell, 72, graduated from NEC in 1967, and is a founding member of the funk-rock collective Parliament-Funkadelic. Worrell contributed to the Red Hot Organization’s 1994 album Stolen Moments: Red Hot + Cool, a TIME magazine Album of the Year. His 2013 song “Get Your Hands Off” received the Independent Music Award for Best Funk/Fusion/Jam Song. Worrell received a Lifetime Achievement Award from NEC in 2010. In 2014 he released Elevation: The Upper Air, a solo piano album.

Braxton, 70, released his first album, 3 Compositions of New Jazz, in 1968, and has collaborated with countless artists on dozens of albums, including Chick Corea, whose quartet Circle he joined in 1970. Known as an influential music educator, Braxton joined the faculty of Wesleyan University in 1990, and retired in 2013 as the John Spencer Camp Professor of Music. He received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1981, a MacArthur Fellowship in 1994, the 2013 Doris Duke Performing Artist Award and the 2014 Jazz Master Award from the National Endowment for the Arts. He was last featured in JT in 2014.

IN CELEBRATION OF THE LIFE, WORK, AND CAREER OF MASTER MUSICIAN AND COMPOSER ANTHONY BRAXTON ON HIS 68th BIRTHDAY!

http://www.jbhe.com/2013/05/wesleyan-universitys-anthony-braxton-wins-225000-doris-duke-artist-award/

All,

While doing personal research on this extensive tribute and retrospective in honor of Anthony Braxton's 68th birthday on June 4 I ran across this very good news item (see below). So hearty congratulations are due Brother Braxton who is not only an outstanding multi-instrumentalist, musician and composer but a very fine person as well. For once the well worn accolade/cliche "it couldn't happen to a nicer or more deserving guy" actually applies in a number of different ways. To say I'm sincerely happy for him and all that he has thus far accomplished in an extraordinary career and life would be an understatement. Well done Anthony...

Kofi

Wesleyan University’s Anthony Braxton Wins $225,000 Doris Duke Artist Award

Filed in Honors and Awards on May 17, 2013

Anthony Braxton, the John Spencer Camp Professor of Music at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, received a 2013 Doris Duke Artist Award. The award program, established in 2011, supports performing artists in contemporary dance, theatre, jazz, and related interdisciplinary work. The award comes with a $225,000 honorarium.

Professor Braxton is a composer, saxophonist, and educator. He won a MacArthur Foundation genius award in 1994. During his long career, he has released more than 100 albums.

http://www.pointofdeparture.org/PoD37/PoD37Braxton.html

All,

This is a great piece about "Jazz"/Jazz if only because it actually forces the reader to THINK for a change and to REFLECT about what the music is, has been, and could be--a process known historically as "listening to the music" ...Just like Anthony Braxton (and every other great and innovative musician IN the "Jazz"/Jazz tradition) ya really gotta love that truly creative impulse in ALL of its (multi)dimensions (in another parallel context the legendary Amiri Baraka identified it as "the Changing Same")... WORD!

Kofi

Braxton & Jazz: IN the Tradition

by Kevin Whitehead

[Lightly adapted from a talk given at Wesleyan University, 16 September 2005, as part of “Anthony Braxton at 60: A Celebration”]

Today I want to talk about Anthony Braxton’s relationship to the jazz tradition, a loaded topic which calls for a few disclaimers up front.

The “Braxton at 60” concert series, concentrating on his compositional output, makes it clear his interests stretch well beyond jazz, which barely figures in the programming. As Braxton once said to Steve Lake, “Jazz is only a very small part of what I do.” He prefers his music to be looked at in totality, and not separated into discrete genres.

By talking about him in a jazz context I don’t seek to discount or ignore his activities in other musical areas, or reduce him to a jazz musician only. I accept Ronald Radano’s view that Braxton has developed his music along twin paths as a jazz-oriented improviser and experimental composer, two areas that frequently overlap. Musical genres are convenient handles for talking about tendencies, but to think any music must conform to a single clear-cut category is to confuse the handle for the suitcase. As Braxton would say, don’t confuse the “isms” for the “is.”

As some jazz watchdogs have given him a frosty reception at times, let’s start by reviewing the cases of other musicians who’ve found themselves in similar predicaments, starting in 1943. Duke Ellington had premiered his suite Black, Brown and Beige on a program at Carnegie Hall, and critic John Hammond slammed the concert in the pages of Jazz magazine. A compressed version of his comments: “During the last 10 years [Duke] has... introduced complex harmonies solely for effect and has experimented with material farther and farther away from dance music. … But the more complicated his music becomes the less feeling his soloists are able to impart to their work. … It was unfortunate that Duke saw fit to tamper with the blues form in order to produce music of greater significance. By becoming more complex he has robbed jazz of most of its basic virtue and lost contact with his audience.”

Now, it’s a bit shocking that John Hammond couldn’t hear any blues content in Black, Brown and Beige, but he wasn’t the only one to have difficulty with Ellington’s suites. Few commentators perceived any cohesion in them, and the jazz literature had to wait 30 years for Brian Priestley and Alan Cohen’s analysis of BBB which highlighted its thematic unity on several levels. (You can find their article, and Hammond’s review, in the Duke Ellington Reader, edited by Mark Tucker, an excellent sourcebook on Ellington’s expansive art and its problematic reception. By the way that anthology also makes it clear that Duke had his critical supporters from the beginning. The myth of critics always missing the point needs deflating, but not here today.)

Ellington’s response to such criticism typically took one of two forms. The first was to sidestep the whole issue by taking jazz out of the equation: as in his famous retort, “There are only two kinds of music, good and the other kind.” Or, “I don’t write jazz, I write Negro folk music,” which is not much of an evasion.

His other response was to argue for a broader view of jazz than his critics applied. In a 1947 interview found in the Reader, Ellington calls jazz “The freest musical expression we have yet seen. To me, then, jazz means simply freedom of musical speech! And it is precisely because of this freedom that so many varied forms of jazz exist. The important thing to remember, however, is that not one of these forms represents jazz by itself. Jazz simply means the freedom to have many forms.”

This was a more constructive rejoinder, I’d argue, if only because Duke’s frequent appearances at jazz festivals and album titles like Jazz Party in Stereo make it clear he never really broke with jazz. Indeed a key part of his musical mission was to expand the resources available to jazz improvisers, and to composers seeking to harness their energy.

The jazz-watchdog files also contain cases where musicians who made a reputation in jazz are criticized just for playing other kinds of music. The way Herbie Hancock’s ‘70s funk was assailed by jazz fans as treasonous is a good example. As I’ve said before, for some folks jazz is like the mafia: once you’re in there’s no getting out, and don’t ever go against the family – as if jazz existed to restrict rather than expand a musician’s creative options.

In extreme cases, the minders of jazz purity may simply cancel the offending musician’s jazz credentials. (We’ll get back to this.) In this regard there are striking parallels between the Dixieland revival of the 1940s and the rise of neo-bop neo-conservative musicians in the 1980s. In both cases, recent developments in the music were discounted as outside the scope of the Real and True Jazz, and said musicians went back 15 or 20 years in search of appropriate stylistic models – even if ‘40s Dixieland doesn’t sound much like King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, and Wynton Marsalis’ fine early quintet with its pre-plotted rhythmic change-ups misses the daring of the spontaneously mutating arrangements of Miles Davis’s mid-‘60s quintet.

Faced with charges of stylistic illegitimacy, some musicians retreat from the battle, just to avoid a fight. Charlie Parker told Down Beat in 1949 that “‘bop is something totally separate and apart’ from the older tradition.” Which is a funny comment from a guy who liked to quote the classic “High Society” clarinet solo all the old New Orleans players knew.

II

Anyone who’s followed Braxton’s reception in jazz will recognize the thumping parallels laid out here: a broad-ranging and ambitious musician is accused of being unfaithful to jazz principles or his African-American roots.

But in Braxton’s case there’s a new wrinkle. Here we have the singular case of a musician widely perceived as a driving force behind jazz in the 1970s, recognized as a leader in every sense, who a decade or so later was branded a heretic, without having changed the basic thrust of his music in the meantime. It’s a case of moving the goal posts after the receiver has spiked the ball.

As Braxton told me in 1993, and has told many others in similar terms, “I’m not a jazz musician. I could not have done my work without the great continuum of trans-African music, the restructural music, all the way up to Ornette Coleman.” But: “By 1979, or even before, I started to move away from that term, when I began to understand that they were redefining the music in a way that would not include me. So I accepted it, because I was tired of the controversy. I only wanted the right to do my music.”

Fair enough. But today I want to reintegrate Braxton into the jazz continuum. I mean, I’m a jazz person, and I want him for us. Why not? He still plays jazz when he wants to, and jazz has been enriched and influenced by his contributions, so it’s a no-brainer.

Jazz is after all a good fit for his musical appetites, for instance a strong desire to improvise with others. It’s part of what he sees as music’s function, to bring people together in a socially positive context.

Braxton is a superb free improviser, thanks in part to his ability to remember what his collaborators play and to develop it as thematic material. (Listen to his duets with German pianist Georg Graewe – Duo Amsterdam ‘91 on Okkadisk – to hear him with another musician who can play that game.) Still, Braxton’s drawn less to unstructured play than to the idea of “navigating through form,” mostly cyclical forms of his own devising. And jazz is a perfect vehicle for mediating between the impulse to improvise and to compose, on cyclical frameworks. And given that Braxton is an African-American from the south side of Chicago, where jazz musicians were handy role models for creative youngsters, you can understand the attraction.

One obvious point of departure is the album of jazz standards In the Tradition, recorded for SteepleChase in 1974 when Braxton was hastily recruited to replace Dexter Gordon on a quartet date with Gordon’s swinging rhythm section with Tete Montoliu, NHØP and Tootie Heath. It was Braxton’s decision to play standards for ease of communication – a strange thing, back then, for a musician who already had a rep for being the outest of the outcats (although he’d recorded a couple of standards already). Braxton showed it was possible to honor bebop phraseology while approaching it from a direction you didn’t expect – for example wailing (and swinging) through the Charlie Parker vehicle “Ornithology” on contrabass clarinet.

One important aspect of Braxton’s personality and musical persona is, he’s a very funny guy. His pieces, and his use of extremely low and high-pitched instruments often carry a whiff of breezy jocularity that’s easy to overlook in serious discussions of his music. (And of course that jocularity is something he shares with such American masters as Armstrong, Fats Waller and Dizzy Gillespie.)

Anyway, the album In the Tradition was a pacesetter. Its title became a catchphrase for experimental improvisers honoring and testing themselves on classic jazz material; Arthur Blythe made one such record that even had the same name. And Braxton himself has returned to standards programs often since then, including programs targeting specific composers like Monk and Andrew Hill.

“Ornithology” is credited to Bird on the LP sleeve; it’s more often credited to trumpeter Benny Harris. So like Miles Davis’s “Donna Lee” it’s one of those typical Parker tunes attributed to someone else – that is to say, built around Parker’s language as an improviser. For Bird, as for Monk, or Steve Lacy, the composition and the improvisation should make a tightly integrated package – you don’t just play the tune and ignore it when you solo over the chords. Or to put it another way, new sorts of written lines will inspire improvised responses that address those written heads on their own terms.

And Braxton has always been interested in material that spurs improvisers into new ways to be creative, and integrate the composed and improvised. You can look in vain in his five books of Composition Notes published in the late 1980s for any mention of a tune’s chord changes – the usual means of organizing improvisation on a jazz theme. Generalizing about his composing is tricky, given the hundreds of pieces he’s written, but it’s safe to say Braxton’s pieces for improvisers focus more on the shape of the line than an underlying harmonic scheme.

III

When commentators reach for adjectives to describe Braxton’s music, the first word that comes up is “angular,” that is to say, sharp-angled, that is to say, often characterized by quick sequences of wide intervals. A classic example is “Composition 6F” (aka “73 degrees A Kelvin”) recorded a couple of times with the Braxton/Corea/Holland/Altschul quartet Circle in 1970. As Braxton’s detractors have helpfully pointed out, this approach parallels certain tendencies in 20th century composed music; one might hear kinship with, say, the short last movement of the Webern “Concerto for Nine Instruments (Opus 24)” from 1934.

But “Composition 6F” doesn’t really sound like that, and the ear tells you why immediately. Even when Webern adopts a peppy Stravinskyian beat, there’s none of the propulsive rhythmic energy and focus that are at the root of Braxton’s piece. Indeed, as Braxton says in the Composition Notes, the akilter rhythm pattern is what really matters, not the melodic contour; he even proposed a revised version of the score that would specify the rhythms but not the pitches. And the specific function of that written line is to put the players into a unique vibrational space for improvising – in the same rhythmic zone as the composed line.

“Composition 6F” was the first piece in his Kelvin series of repetitive music structures one might roughly characterize as minimalist – minimalism being a style of composed music whose influence in jazz has been far greater than is generally acknowledged. (There’s a good doctoral thesis in that for someone.) But the particular sort of momentum “6F” has – a saw tooth rhythm, with a few quick sextuplets or other ‘tuplets thrown in to push things off kilter for a second – is typical of many Braxton pieces, including far more recent ones in the Ghost Trance sequence, like “Composition 245” as heard on Delmark’s Four Compositions (GTM) 2000.

A certain kind of hectic momentum is a major part of Braxton’s esthetic, and one not necessarily incompatible with swing. Take for example 1975’s “Composition 52,” as played by a Braxton quartet with Anthony Davis, Mark Helias and Edward Blackwell on Six Compositions Quartet (1982) (Antilles). One thing I particularly like about that record is that there are pieces like “52” where Davis on piano is clearly playing on chord changes, at least sometimes. Until I started working on this talk I underestimated the attraction of playing on chords to Braxton, and indeed one of the notable things about his many standards programs is how gleefully he enters into that particular game.

In “Composition 52,” we may note in his improvising the serrated rhythms and angles, and some of regular syncopations of ragtime amid the ‘tuplety subdivisions of the ground beat. That’s typical Braxton, and there’s no mistaking its rhythmic sophistication or drive. That he values momentum may be inferred from a few of the master drummers he’s employed or recorded with, including Blackwell, Heath, Steve McCall, Philly Joe Jones, Max Roach, and Victor Lewis.

When even non-wind players enter the realm of pieces like “Composition 6F” and “52,” they are apt to favor breath-like phrasing. The robotic music comes alive, which of course is the point: improvisation breathes life into formal structures. And jazz from early on has sought increasingly challenging material to test and inspire the improviser – even if it means breaking with long-established practice. (Not for nothing does Braxton cite Ornette Coleman’s example.) Braxton’s lines all but preclude a solo made of old-school licks learned at Berklee.

And his innovations go way beyond the shape or rhythm of a line. Some of his pieces call for musicians to isolate certain registers, or specific attacks or strategies at different times. Even when he uses familiar devices, he flips them on their backs or sides. A piece may emulate bop phrasing or celebrate Count Basie or evoke the good feeling he got as a kid spying his father at a Chicago street parade in the middle of a work-school day. But the source material is always transformed – as with Ellington, come to think of it. Like Duke he paints a picture of the community in action: an ideal community with room and tolerance for collective and individual initiatives.

In the Composition Notes, Braxton lays out unconventional strategies for improvisation built into many pieces: a call for drummer and bassist to play opposing rhythms, or for a soloist to play in deliberate opposition to the ensemble – encouraging you to hear the music in several layers or dimensions at once: the Charles Ives principle, as I hope it’s known in Connecticut. Even in solo saxophone pieces he’ll create the illusion of spatial distance, juxtaposing very loud and very soft passages, as if coming from different points in space: a self-contained call-and-response sequence. Or he’ll ask a soloist to improvise up to a written theme rather than away from it – so the composition seems to flower from the improvising, rather like the way Charlie Parker’s tunes sound like they began as improvisations on familiar chords. (“Ornithology” takes off from a line Bird played with Jay McShann.)

In time Braxton’s regular collaborators internalized such procedures and could apply them to any material in the band’s book. One reason why many of us cherish his 1986-1994 quartet – the one with Marilyn Crispell, Mark Dresser and Gerry Hemingway – was that they really knew the rules of the game.

Incidentally around the same time, a similar process was going on independently in Holland, with Misha Mengelberg and ICP. The musicians would take procedures Misha instructed them to use on certain pieces, and then apply them on their own initiative in any appropriate spot. The whole band would then pick up on that, so the boss’s esthetic becomes a self-sustaining musical system – a perpetuum mobile. ICP really perfected this in the 1980s, but Braxton was already working toward and through such ideas in the ‘70s.

IV

Not long after making In the Tradition Braxton signed with Arista records, a major major label at the time, for whom he made a series of nine high-profile albums, which include memorable time studies for quartets; “Composition 58,” a big band march that sounds like John Phillip Sousa having a breakdown over a skipping record which remains one of Braxton’s best-loved compositions; an even better march for quartet with George Lewis on trombone (“6C,” recorded live in Berlin in 1976); a duet with Muhal Richard Abrams on Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag”; a saxophone quartet for which Braxton kindly brought together three-quarters of what would soon be the World Saxophone Quartet, who never remembered to thank him for it. He also got to record “Composition 82” for four orchestras, and “95” for two pianos, so he didn’t only get to document only the jazzy stuff.

In the 1970s Braxton was also on the road a lot, playing festivals, and getting his live music documented. Beginning with his late-‘70s concert recordings you can hear his genius for assembling a set of music, using the various collage structures and multi-dimensional opposition strategies just mentioned. Say what you will about Braxton’s swing micro-timing, he’s a master of macro-timing. The way a good drummer makes a single bar swing with internal surges and hesitations, Braxton can make the overarching structure of a whole set swing like that one bar. And on the micro-level, the various layers of activity from moment to moment provide a vibrant listening experience that little in jazz can equal. With his Crispell/Dresser/Hemingway quartet in particular, he got into complex layering of independently written pieces that fit together as aspects of one giant mega-composition, analogous perhaps to the way the seemingly disparate parts of Ellington’s suites fit together.

The composer has stressed how the multiple levels on which these performances work can help us deal with modern life in which we’re bombarded by more and more sensory input. To be able to follow a quartet performance where, say, the pianist is playing a totally notated composition, the saxophonist is improvising a solo line, perhaps off another tune, and the bass player and drummer are playing two different “pulse tracks” – dynamic, syncopated rhythmic patterns – to be able to follow that is not so different from listening to your iPod while flipping through the cable channels as you check your email while waiting for your phone to ring.

In Braxton’s (or Mengelberg’s) collage structures and constellations of events and mutable forms, one may recognize certain ideas creeping in from the classical avant-garde of the ‘50s and ‘60s, the whole big Earle Brown to Stockhausen mix. But then it’s only natural that Braxton’s varied musical influences and tastes infiltrate each other. By the late 1960s, he was already melding separate musical disciplines in open soundscapes. As Braxton points out, we all have cosmopolitan backgrounds, and are under the sway of many influences from diverse cultures, which open up new ranges of possibilities – which is where he runs into 1943 John Hammond-type objections from certain listeners, for opening up the possibilities too much.

I speak mainly of Wynton Marsalis and his allies Stanley Crouch and Tom Piazza – not so many people, really, although they’ve certainly been diligent about trashing Braxton over the years.

You can understand the predicament Braxton’s music created for educated young musicians who’d polished the whole jazz school bop-to-Brecker skill set till it shone like the good silverware. Braxton was raising a whole other set of options that required a very different conceptual toolbox. That was bound to make people uncomfortable. I don’t think that’s grounds to vilify a musician who never sought to do anyone any harm, but if you were looking to hype a derivative composer like Wynton as modern jazz’s big thinker, you may find it necessary to brush back the competition.

So, as mentioned earlier, they raised what amounts to the old Dixieland argument against bebop: these strange new procedures are not what real jazz is about. But this position rests on an absurd premise: that jazz should be kept pure, when it had evolved and taken shape as a mutt form.

Starting around 1900 the music’s creators applied the improvisational impulse to any material within earshot: hymns, street cries, field hollers, march and social dance and blues forms, the classical themes that ragtime and jazz pianists would extemporize on, barnyard animal impressions, handclap patterns harking back to West African polyrhythms, Islamic isorhythms, modified Congolese beats arriving via Cuba – and myriad echoes of Sousa-type concert bands, with their a cappella breaks and virtuoso solos in contrasting hot and sweet styles, and said solos’ operatic high-note endings. Also the syncopated songs of Tin Pan Alley which often embedded quotes from other tunes, the exquisite vocal timing of black vaudeville comic Bert Williams, the rhythms of trains and the sounds of new technology.

Think of Jelly Roll Morton’s car horns on “Sidewalk Blues,” Armstrong faking the sound of a skipping record on “I’m Not Rough,” and the nasal speech-like brass solos on Ellington’s early classics, resembling a remote voice heard over a telephone. Braxtonian multi-dimensionalism was already part of the music by 1926 and ‘7.

That’s why I call jazz a mutt. The hound can really run, but no amount of wishful thinking or ethnic cleansing can transform a mutt into a pure breed. To suggest that jazz, to honor its heritage, limit itself to only certain specific episodes from its own past is absurd – like asking a jury to disregard a witness’s earlier remark. As Braxton put it in 2001: “Every music is still relevant – whatever the projection.”

V

No one has to tell Braxton about the richness of the jazz tradition – he teaches it at Wesleyan. His eight CDs of standard tunes for quartet, recorded in 2003 and released in two boxes on Leo, demonstrate his broad tastes in jazz material: tunes from the 1920s, bossa novas, and pieces by Cole Porter, Wayne Shorter, Monk, Coltrane, Joe Henderson, Eddie Harris – and the unfashionable Dave Brubeck, whom Braxton has long championed, a musician whose endearingly clunky timing turns some jazz fans off.

Every Braxtonian has heard the objection that he’s not the swingingest jazz musician, and I’ll concede as much. But if someone else swinging harder than you cancels your jazz credentials, there’d only be one jazz musician left: Billy Higgins? Jelly Roll Morton may not have been the swingingest cat of the 1920s, but we recognize him as a jazz master for his restructuralist tendencies. His Red Hot Peppers records of 1926 had the conceptual daring to reformulate much of what jazz was and had been constructed from, adding lowbrow humor and the sounds of the modern city.

Braxton’s compositional language began with his saxophone language, in which I’ve always heard the sharp-angled, against-the-grain improvising of Eric Dolphy, who recorded a few solo pieces in that time before Braxton made solo recitals fashionable. The leaps that bookend Dolphy’s 1963 solo take on Victor Young’s “Love Me” make the parallel explicit.

Anyone who, say, attended last night’s solo concert knows Braxton can play the heck out of the saxophone. To quote from something I wrote last year, “Like all great jazz musicians he understands that timing, timbre and note-choices are intimately connected: how slowing the rhythm ever so slightly, sputtering that note, and placing it just off center pitch, all work to give it triple impact. His tone may be aggressive or growling one moment, parched or disarmingly vulnerable the next.”

“He may stomp on the offbeat like a ragtime pianist. Sometimes his line will attack the rhythm head-on; sometimes it’ll slide backwards over the pulse, moon-walking on ice; sometimes he’ll divide a fast phrase into complex groupings ... or speed up in the middle of an already speedy phrase.” His accentual patterns are more complex than the alternating strong-weak strong-weak accents of your average sure-fire swinger.

The jittery nature of his improvising is one thing that bugs folks who like their swing nice and round all the time, but that’s no reason to ignore everything else going on, in terms of thinking on one’s feet, and improvising complex phrases while honoring the tune – all that good stuff his detractors claim to be for. The idea that jazz’s rhythmic development is already complete, and 4/4 swing is the only way to fly is ridiculous: how can the development of a living music ever be finished?

Braxton’s influence as a saxophonist since the 1970s has been much greater than the jazz folks give credit for. I was going to compile a list of saxophonists who bear his influence, but let me just mention one: in Greg Osby’s up and down beat-parsing and shifting accents, one can hear a lot of Braxton creeping through. (That’s true of Osby’s old ally Steve Coleman too.) The connection to the ‘80s M-BASE saxophonists is particularly interesting because Osby hears how those accentual patterns relate to hip-hop. (You can hear all this come together in his “Concepticus in C” from Zone.) But then jazz usually comes to grips with pop music of its time, one way or another.

You could even talk about a Dolphy-Braxton-Osby rhythmic continuum, if you like – Greg’s low opinion of Dolphy notwithstanding. Osby’s style is on one level a more limber version of the master’s angularity.

So anyway, I say, as long as Braxton has done so much to add new tools to the improviser’s and bandleader’s arsenal, since he’s such a keen student of the music and such a striking horn player, since he’s a fundamental influence on many of today’s players (not least his many successful former students from Mills and Wesleyan), let’s make it official and reaffirm his connection to the jazz fold he never really left – even as he remains free to operate outside of jazz.

There’s another reason for that reaffirmation, which we writers don’t talk about enough. The jazz wars of the early ‘90s, where the gatekeepers decided to purge Braxton from the ranks? Those guys lost that war. At Lincoln Center, they finally let in Misha Mengelberg and recently paid tribute to ‘60s Coltrane, if not Anthony Braxton. And many of the so-called young lions who were assumed to share Marsalis’ outlook have shown that their interests are considerably more broad – look, for example, to funk records by Roy Hargrove or Terence Blanchard or Branford Marsalis, or Christian McBride’s salute to Steely Dan. It sometimes appears the only jazz musicians who haven’t flirted with funk are Wynton Marsalis and Anthony Braxton.

Turning back the clock is always a loser’s game, except at the end of daylight savings. That’s how the jazz wars played out in the ‘40s, and in the ‘90s. The music will keep changing as long as it’s alive; and in the last 35 or 40 years no one has pumped more oxygen into jazz than Braxton. For that, jazz might be a little more grateful.

Nobody can really speak for jazz, but as long as some people make the attempt, and since I have the podium, Anthony Braxton, jazz welcomes you back. Like you never even left. Even if you reject it, you can’t change that. Mr. Braxton: Thank you for your music sir.

© Kevin Whitehead 2011

INTERVIEWS WITH ANTHONY BRAXTON:

Uploaded on September 16, 2008

Anthony Braxton speaks about his work, experiences and other artists such as John Coltrane, Marilyn Crispell, Sun Ra & Max Roach.

http://tricentricfoundation.org/

http://www.myspace.com/anthonybraxton...

INTERVIEW WITH ANTHONY BRAXTON - North Sea Jazz 1997:

Radio 6 / NTR reporter Co de Kloet talks with Anthony Braxton in Holland, North Sea Jazz 1997

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h8C_iolinyA

MUSIC OF ANTHONY BRAXTON ON YOUTUBE:

http://www.youtube.com/artist/anthony-braxton

INTERVIEW WITH ANTHONY BRAXTON IN NEW YORK 2006:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xp4d6sQIqLg

ANTHONY BRAXTON ON CHESS, MATH, AND MUSIC:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jgn1gdvgYQo

LECTURE BY ANTHONY BRAXTON

MUSIC SEMINAR IN INSTANBUL, TURKEY:

Part 1 of 6

http://www.akamu.net/braxton/biography.htm

Biography:

Anthony Braxton was born in Chicago (Illinois) on 4 June 1945.

An American composer as well as well as a highly versatile musician who plays various saxophones, clarinet, flute and piano he has created a large body of highly complex work.

While not known by the general public, Braxton is one of the most prolific American musicians/composers to date, having released well over 100 albums of his works since the 1960s.

Among the vast array of instruments he utilizes are the flute; the sopranino, soprano, C-Melody, F alto, E-flat alto, baritone, bass, and contrabass saxophones; and the E-flat, B-flat, and contrabass clarinets.

Braxton studied at the Chicago School of Music and at Roosevelt University. At Wilson Junior College, he met Roscoe Mitchell and Jack DeJohnette.

After a stint in the army, Braxton joined the AACM.

After moving to Paris with the Anthony Braxton Trio (which evolved into the Creative Construction Company), he returned to the US, where he stayed at Ornette Coleman's house, gave up music, and worked as a chess hustler in the city's Washington Square Park.

In 1970, he and Chick Corea studied scores by Stockhausen, Boulez, Xenakis and Schoenberg together, and Braxton joined Corea's Circle.

In 1972, he made his bandleader debut (leading duos, trios, and quintets) and played solo at Carnegie Hall.

In the early 1970s, he worked with the "Musica Elettronica Viva", which performed contemporary classical and improvised music.

In 1974, he signed a recording contract with Arista Records.

One of the first black abstract musicians to acknowledge a debt to contemporary European art music, Braxton is known as much as a composer as an improviser. The output ranges from solo pieces to For Four Orchestras, a work work that has been described as "a colossal work, longer than any of Gustav Mahler's symphonies and larger in instrumentation than most of Richard Wagner's operas."

His 1968 solo alto saxophone double LP For Alto (finally released in 1971) remains a jazz landmark, for its encouragement of solo instrumental recordings. Other important recordings include Three Compositions of New Jazz (1968, Delmark), his 1970s releases on Arista, Composition No. 96 (1981; Leo), Quartet (London) 1985; Quartet (Birmingham) 1985; Quartet (Coventry) 1985 (all on Leo), Seven Compositions (Trio) 1989 (hat Art), Duo (London) 1993 & Trio (London), both on the Leo record label.

Critic Chris Kelsey writes that "Although Braxton exhibited a genuine if highly idiosyncratic ability to play older forms (influenced especially by saxophonists Warne Marsh, John Coltrane, Paul Desmond, and Eric Dolphy), he was never really accepted by the jazz establishment, due to his manifest infatuation with the practices of such non-jazz artists as John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen".

The timing of this crowning achievement couldn't be better for Braxton's most recent professional goals: he is the founding Artistic Director of the newly incorporated Tri-Centric Foundation, Inc., a New York-based not-for-profit corporation including an ensemble of some 38 musicians, four to eight vocalists, and computer-graphic video artists assembled to perform his compositions.

The ensemble's debut at New York's The Kitchen sold out the last and most of the first two of three nights, through the press excitement it generated; the reviews--in Down Beat and the Chicago Tribune (John Corbett), the Village Voice (Kevin Whitehead), and the New York Times (Jon Pareles)--ranged from positive to ecstatic.

Most importantly, the musical success of the event inspired Braxton to pursue the “three-day and -night” program concept for this ensemble, including lectures/informances, and splinter chamber performances, around the world.

The second New York event, indeed, expanded on the concept: The Knitting Factory presented six nights of Anthony Braxton and his music, in all the variety of its vision. The first night showcased the composer's solo alto saxophone playing; the second his treatments of jazz-traditional material, both as reeds player and pianist; the third, his music for solo piano, and for synthesizer and acoustic sextet; the fourth showcased his new “Ghost Trance” music for small-to-medium groups; and the fifth and sixth his large-ensemble music, including Composition 102, with giant puppets. As with The Kitchen, all six nights included a full house and enthusiastic response.

This successful first season paid off: the second season has been virtually paid for by grants from the Mary Flagler Carey Charitable Trust and the Rockefeller Foundation in New York City. It will feature the world premiere of the four-hour opera Trillium R at the John Jay Theater in New York, and the theatrical Composition 173 (for actors, improvisers, and ensemble) in collaboration with New York's Living Theater members, at The Kitchen.

Anthony Braxton is widely and critically acclaimed as a seminal figure in the music of the late 20th century. His work, both as a saxophonist and a composer, has broken new conceptual and technical ground in the trans-African and trans-European (a.k.a. “jazz” and “American Experimental”) musical traditions in North America as defined by master improvisers such as Warne Marsh, John Coltrane, Paul Desmond, Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, and he and his own peers in the historic Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM, founded in Chicago in the late '60s); and by composers such as Charles Ives, Harry Partch, and John Cage.

He has further worked his own extensions of instrumental technique, timbre, meter and rhythm, voicing and ensemble make-up, harmony and melody, and improvisation and notation into a personal synthesis of those traditions with 20th-century European art music as defined by Schoenberg, Stockhausen, Xenakis, Varese and others.

Braxton's three decades worth of recorded output is kaleidescopic and prolific, and has won and continues to win prestigious awards and critical praise. Books, anthology chapters, scholarly studies, reviews and interviews and other media and academic attention to him and his work have also accumulated steadily and increasingly throughout those years, and continue to do so. His own self-published writings about the musical traditions from which he works and their historical and cultural contexts (Tri-Axium Writings 1-3) and his five-volume Composition Notes A-E are unparalleled by artists from the oral and unmatched by those in the literate tradition.

Braxton is also a tenured professor at Wesleyan University, one of the world's centers of world music. His teaching career, begun at Mills College in Oakland, California, has become as much a part of his creative life as his own work, and includes training and leading performance ensembles and private tutorials in his own music, computer and electronic music, and history courses in the music of his major musical influences, from the Western Medieval composer Hildegard of Bingen to contemporary masters with whom he himself has worked (e.g. Cage, Coleman).

Braxton's name continues to stand for the broadest integration of such oft-conflicting poles as “creative freedom” and “responsibility,” discipline and energy, and vision of the future and respect for tradition in the current cultural debates about the nature and place of the Western and African-American musical traditions in America. His newly formed New York-based ensemble company is bringing to that debate a voice that is fresh and strong, still as new as ever even as it takes on the authority of a seasoned master.

http://tricentricfoundation.org/anthony-braxton/bio/

Anthony Braxton (b. June 4, 1945) has boldly redefined the boundaries of American music for more than 40 years. Drawing on such lifelong influences as jazz saxophonists Warne Marsh and Albert Ayler, innovative American composers John Cage and Charles Ives and pioneering European Avant-Garde figures Karlheinz Stockhausen and Iannis Xenakis, he created a unique musical system, with its own classifications and graphics-based language that embraces a variety of traditions and genres while defying categorization of its own.

His multi-faceted career includes hundreds of recordings, performances all over the world with fellow legends and younger musicians alike, an influential legacy as an educator and author of scholarly writings, and an ardent international fan base that passionately supports and documents it all. From his early work as a pioneering solo performer in the late 1960’s through his eclectic experiments on Arista Records in the 1970’s, his landmark quartet of the 1980’s, and more recent endeavors, such as his cycle of Trillium operas, a piece for 100 tubas and the day-long, installation-based Sonic Genome Project, his vast body of work is unparalleled.

In 2010, he revived the Tri-Centric Foundation which had been dormant for 10 years. In 2011, he released his first studio-recorded opera Trillium E; that year also saw the 4-evening Tri-Centric Festival (held at Roulette in Brooklyn), which was the most comprehensive portrait of Braxton’s five-decade career yet presented in the United States. Braxton is a tenured professor at Wesleyan University, which has one of the nation’s leading programs for world and experimental music, and his many awards include a MacArthur Fellowship, a Guggenheim Fellowship, a 2009 honorary doctorate from the Université de Liège, Belgium, a 2013 Doris Duke Performing Artist Award and a 2013 New Music USA Letter of Distinction. His next four-act opera, Trillium J, will be premiered in April 2014 at Brooklyn’s Roulette, headlining a two-week festival of Tri-Centric music.

Bio | The Tri-Centric Foundation

tricentricfoundation.org

New Braxton House Records

http://www.scaruffi.com/jazz/braxton.html

Chicago's saxophonist Anthony Braxton (1945) was the creative musician who displayed the most obvious affinity with western classical music, scoring chamber music (both for solo instrument and for small ensembles), as well as orchestral music, that seemed aimed at extending the vocabulary of European music rather than the vocabulary of jazz music. If his was jazz music, it was the most cerebral jazz ever.

Better than any other jazz musician, Braxton represented the quantum leap forward that jazz music experienced after free jazz opened the doors of abstract composition. The music that was born as an evolution of blues and ragtime suddenly competed with the white avantgarde for radical redefinitions of the concept of harmony. Following in the footsteps of John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen, Braxton introduced new graphic notations to capture the subtleties of his scores, and even titled his pieces with diagrams instead of words. He invented new ways of composing and performing music. He also loved to write about his musical theory.

As a virtuoso of woodwind instruments (particularly of the alto saxophone), Braxton worked to extend the timbre and the technique. But, unlike his predecessors, Braxton was motivated by science rather than by emotion. Originally inspired by John Coltrane, he impersonated Coltrane's antithesis.

In 1967 Braxton formed a trio with violinist Leroy Jenkins and trumpeter Leo Smith, the Creative Construction Company, that gladly dispensed with the rhythm section, with melody and with traditional harmony. Three Compositions of New Jazz (april 1968), that also featured Muhal Richard Abrams on piano, contained the 20-minute Comp. 6E, the manifesto of Braxton's style (at the same time abstract, visceral and geometric). The record sleeve provided the graphic scores of the music, that looked more like mathematical equations, and explained the chance-based technique that were incorporated in those scores (a` la John Cage's aleatory music). A few months later Braxton became the first musician ever to record an album of saxophone solos, For Alto (february 1969). This groundbreaking double-LP album contained eight extended pieces (each cryptically dedicated to a musician), culminating with another 20-minute juggernaut, Comp. 8B. His playing showed little respect for jazz traditions, but a lot of curiosity for textures and patterns. While this was mostly music of the brain, it was performed with an almost hysterical intensity. Braxton himself seemed reluctant to continue the project.

The trio's contemporary Silence (july 1969), released only six years later, contained Jenkins' 17-minute Off The Top Of My Head and Smith's 15-minute Silence, two pieces that were less radical and more obviously in the free-jazz vein. The French album Anthony Braxton (september 1969) sounded like an appendix to the trio's music, with Smith's ten-minute The Light On The Dalta and Jenkins' nine-minute Simple Like, but also included a new Braxton vision, the 20-minute Comp. 6G. The line-up consisted of the trio plus drummer Steve McCall. It looked more conventional on paper, but Braxton played all sorts of woodwinds, Smith played horns and siren besides trumpet, and Jenkins toyed with viola, flute, harmonica, etc. Adding pianist Muhal Richard Abrams and drummer Steve McCall, Creative Construction Company (may 1970), released in 1976, was mainly taken up by a 34-minute Jenkins composition, Muhal. The second volume (same session) was, again, a colossal Jenkins track, No More White Gloves.

In the meantime, Braxton had formed Circle, a quartet with pianist Chick Corea, double-bassist Dave Holland and drummer Barry Altschul. Their first document, Circulus (august 1970), credited to Corea when released as a double-LP in 1975, contained three lengthy collective improvisations titled Quartet Piece. Circling In (october 1970), again credited to Corea when released as a double-LP in 1978, was a less cryptic recording, highlighted by Chimes and Braxton's Comp. 6F. The Complete (february 1971) offered more of Braxton's compositions employing Holland, Altschul, Corea, plus trumpeter Kenny Wheeler and multiple tubas, in different settings. The Gathering (may 1971), the first studio album credited to Circle, contained only one 42-minute Corea composition, the title-track, and each of the four members played multiple instruments.

Relocating to New York in 1970, Braxton became the recognized guru of creative music. Together Alone (december 1971), released in 1975, inaugurated the series of Braxton duets. This one was with Joseph Jarman (both alternating at multiple instruments), highlighted by Jarman's 14-minute Dawn Dance One and Braxton's 15-minute Comp. 20.

Finally, Braxton gave For Alto a successor, and it almost sounded like everything he had done in between the two masterpieces was merely a long rehearsal. Saxophone Improvisations Series F (february 1972) was again a double-LP collection of lengthy tracks dedicated to musicians. The longest, 104 Kelvin M12 (or, better, Comp. 26F), was dedicated to minimalist composer Philip Glass, and for a good reason: the influence of minimalist iteration was strong, lending the album its hypnotic, otherworldly quality. Braxton's process was obscure and often not very musical, but the concentration was worthy of a physicist discovering a new substance. These pieces openly unveiled the process of distortion, variation and repetition that underlay the neurotic, claustrophonic feeling of Braxton's music.

The three-LP live album Creative Music Orchestra (march 1972) introduced a new side of Braxton. Four trumpets, four saxophones, tuba, piano, two bassists and two percussionists performed twelve Braxton compositions.

Town Hall 1972 (may 1972) included the 35-minute Comp 6P for Braxton, Altschul, Holland, Jeanne Lee (vocals) and John Stubblefield (woodwinds).

Braxton's new quartet, that basically replaced Corea's piano with Kenny Wheeler's trumpet (keeping Holland and Altschul), debuted on Live at Moers Festival (june 1974), a double-LP that contained six of Braxton's cryptic and overlong compositions.

But the prolific Braxton was recording non-stop, rarely replicating the powerful atmosphere of his masterpieces: Four Compositions (january 1973) for a trio with percussionist Masahiko Sato and bassist Keiki Midorikawa; First Duo Concert (june 1974) and Royal (july 1974) with British guitarist Derek Bailey; Trio and Duet (october 1974), that contained Comp 36 for Braxton (clarinets), Smith (trumpet) and Richard Teitelbaum (synthesizer); New York Fall 1974 (september 1974), that contained Comp 37 for a saxophone quartet (Braxton, Julius Hemphill, Oliver Lake and Hamiet Bluiett), Comp 38A for saxophone and synthesizer (Richard Teitelbaum), Comp 23A for sax-violin-trumpet quintet (Wheeler, Jenkins, Holland, drummer Jerome Cooper); Five Pieces (july 1975), that contained Comp 23E for the quartet (Braxton, Holland, Altschul and Wheeler); etc. Most of these albums were trivial, although each contained something that opened new directions for experimental music.

Braxton returned to the most ambitious idea of his career with Creative Orchestra Music (february 1976), six relatively short pieces for a mid-size ensemble that constituted his most eclectic output yet.

In between these seminal recordings, Braxton wasted his talent in erratic collaborations. Duets with trombonist George Lewis yielded Elements of Surprise (june 1976), dominated by Lewis' Music For Trombone and Bb Soprano, and Donaueschingen (october 1976), dominated by Lewis' 41-minute Fred's Garden. Duets with synthesist Richard Teitelbaum yielded Time Zones (june 1976), taken up by Teitelbaum's Crossing and Behemoth Dreams. Further collaborations accounted for Duets (august 1976) with pianist Muhal Richard Abrams and Duets (december 1976) with Roscoe Mitchell also on reeds.

Dortmund (october 1976) documented the new quartet with Lewis replacing Wheeler (especially in the long Comp 40F), while Quintet (june 1977) documented the quintet of Braxton, Lewis, Abrams, bassist Mark Helias and drummer Charles "Bobo" Shaw.

Among all these mediocre recordings one stood out: For Trio (september 1977), containing two versions of Comp 76 (one with Henry Threadgill and Douglas Ewart, and one with Roscoe Mitchell and Joseph Jarman). The sheer number of instruments played by each member of the two trios was unheard of in jazz music.

He revisited two of his greatest ideas in rather inferior albums: Solo (may 1978) and Creative Orchestra (may 1978), that he only conducted (without playing). But then he outdid himself on For Four Orchestras (may 1978), that contained just one colossal piece, the two-hour Comp 82 for 160 musicians and four conductors: the four orchestras surrounded the audience, that was given a chance to hear the chaotic interplay as it strove to evolve towards organic music. Braxton planned to score similar symphonies for six, eight, ten, and eventually 100 orchestras. The Alto Saxophone Improvisations (november 1979) were also more interesting, although a far cry from his two solo masterpieces. At last, his algorithmic music was heading for magniloquent drama.

Two of his best albums of this period were collaborations with veteran drummer Max Roach: Birth and Rebirth (september 1978) and One In Two - Two In One (august 1979).

Performance (september 1979) and Seven Compositions (november 1979) introduced a piano-less quartet with trombonist Ray Anderson.

In the meantime the routine of avantgarde compositions resumed. Composition No. 94 (april 1980) contained two versions of the piece (forward and backward reading) for saxophone or clarinet, guitar and trombone. For Two Pianos (september 1980) contained Braxton's 50-minute Comp. 95 performed by Frederic Rzewski and Ursula Oppens. Braxton returned to the large ensemble for Composition N. 96 (may 1981). Open Aspects (march 1982) was another session with Richard Teitelbaum (now a specialist of computer interaction), but this time it was dominated by Braxton's compositions.

Composition 113 (december 1983) was a new solo album, but different from anything he had done before. First of all, Braxton played only soprano saxophone. Second, the album contained a six-movement suite that told a story. It was one of his most "humane" works.

Four Pieces (november 1981) documents a long lost studio collaboration between pianist Giorgio Gaslini and Anthony Braxton.

The quartet remained Braxton's favorite format, but it began to include the piano. Composition 98 (january 1981) documented a transitional quartet with Anderson and pianist Marilyn Crispell. The quartet consisted of pianist Anthony Davis, bassist Mark Helias and drummer Edward Blackwell on Six Compositions - Quartet (october 1981), and for once the players prevailed over the composer. Four Compositions - Quartet (march 1983) was a more composition-oriented effort by a quartet with Lewis, bassist John Lindberg and percussionist Gerry Hemingway. Six Compositions - Quartet (1984) featured Crispell, Lingberg and Hemingway. Quartet (november 1985) had stabilized with pianist Marilyn Crispell, double-bassist Mark Dresser and drummer Gerry Hemingway, although Five Compositions - Quartet (july 1986) replaced Crispell with David Rosenboom.

The list of experiments was virtually infinite. The Aggregate (august 1986), a collaboration with the Rova Saxophone Quartet, contained Composition 129. 19 [Solo] Compositions 1988 (april 1988) contains 16 brief originals and three standards. Ensemble (october 1988) contained the 41-minute Composition No. 141 for Braxton's saxophones, trombone (Lewis), tenor saxophone (Evan Parker), trumpet, vibraphone, bass and percussion. The Seven Compositions (march 1989) were scored for trio. Eugene (january 1989) collected eight compositions for orchestra. Composition No. 165 (february 1992) was scored for 18 instruments. Two Lines (october 1992) contained duets with David Rosenboom at software-controlled piano. The twelve alto solos of Wesleyan (november 1992) and the Four Ensemble Compositions (march 1993) were, again, pale imitations of past masterpieces. 11 Compositions (march 1995) were duets with a koto player. 10 Compositions (Duet) 1995 (august 1995) documents a collaboration between Anthony Braxton (on various saxes, clarinet and flute) and bassist Joe Fonda. Octet (november 1995) contained Comp. 188, almost one-hour long. Ensemble (november 1995) contained Comp. 187 for a ten-piece combo. Tentet (june 1996) contained the 67-minute Comp. 193. The most fascinating album of the period, Composition 192 (june 1996), was a duet with vocalist Lauren Newton.

Eight (+1) Tristano Compositions 1989 For Warne Marsh was a Lennie Tristano tribute.

However, Braxton's focus was finally changing. Composition 174 (february 1994) was a sort of soundtrack for a theatrical event, scored for ten percussionists and narrating voice. Anthony Braxton with the Creative Jazz Orchestra (may 1994) debuted his Trillium Dialogues M, his version of the opera. Composition 173 (december 1994) was another piece for both actors and musicians. Composition No. 102 (march 1996) was even music for puppet theater. Trillium R - Shala Fears For The Poor (october 1996) contained Composition 162, an opera in four acts for nine singers, nine instrumentalists (tenor saxophone, soprano saxophone, baritone saxophone, flute, oboe, bass clarinet, clarinet, French horn, trombone) and tri-centric orchestra (alto and soprano saxophones, two trumpets, three clarinets, bass clarinet, two flutes, oboe, bassoon, harp, six violins, two violas, two cellos, two basses, accordion, two French horns, trombone, tuba, three percussionists).

Four Compositions (august 1995) for quartet and Composition 193 (june 1996) for tentet inaugurated yet another strand of Braxton's art, "ghost trance music". And several hour-long compositions performed with the students of his classes indulged in all aspects of his musical exploration: the four-disc Ninetet at Yoshi's (august 1997) for six reed players, guitar, bass and percussion (containing the compositions numbered 207-214); Two Compositions (april 1998) for trio of reeds; Four Compositions (may 1998), notably Composition 223 for 15-piece ensemble, Four Compositions (may 2000) for piano-based quartet, Composition 247 (may 2000) for two saxophonists and bagpipes, Composition 249 (may 2000) with fellow saxophonist Brandon Evans, Composition 169 + (186 + 206 + 214) (june 2000) for saxophone quartet and symphonic orchestra, Six Compositions (january 2001) for duo, trio, quartet, quintet and tentet (the 91-minute Composition 286).

However, Braxton also delivered the shorter improvisations/compositions of 10 Solo Bagpipe Compositions (may 2000), Eight Compositions (march 2001) for quintet, Solo (may 2002). He also recorded a few albums of other people's music.

Braxton temporarily abandoned "ghost trance music" for the live duets with Leo Smith on Organic Resonance (april 2003), namely Comp. 314 and Comp. 315, and Comp. 316, on their next collaboration, Saturn Conjunct the Grand Canyon in a Sweet Embrace (april 2003).

Quintet (november 2004) contains Composition 343 for reeds, cornet, guitar, bass and percussion.

Sextet (may 2005) contains the 68-minute Composition 345 for saxophones, trumpet, viola/violin, tuba, bass and percussion.

Trio Glasgow (june 2005), i.e. the 56-minute Composition 323a and the 60-minute Composition 323b, featured Tom Crean on guitar and Taylor Ho Bynum on trumpets. Its companion was the four-disc set Solo Live At Gasthof Heidelberg Loppem (june 2005), containing Compositions 307-309 and a few covers.

4 Compositions - Phonomanie VIII (june 2005) contains the 35-minute Comp. 301 for solo piano, the 47-minute Comp. 323 A ("tri-centric version" for reeds, electronics, cornet and percussion), and two compositions for large ensemble (reeds, electronics, piano, clarinets, alto saxophones, trumpet, trombone, tuba, guitar, violins, viola, cello, bass, including two conductors besides himself, a synchronous conductor and a polarity conductor): the 56-minute Comp. 96 + 134 and the 65-minute Comp. 169 + 147.

The nine-disc set 9 Compositions - Iridium (march 2006) documented the world premieres of Compositions 350 through 358 (each about one hour long) as performed by his 12+1tet (roughly four saxophonists, trumpet, guitar, flute, viola, trombone, tuba, bassoon, bass, percussion) over the course of four nights in a New York club, the final works in the "Ghost Trance Music" series.

Notable collaborations included: Compositions/ Improvisations (june 2000) with saxophonist Scott Rosenberg, Four Compositions (october 2000) with vocalist Alex Horwitz, Duets (january 2002) with cornetist Taylor Ho Bynum, the double-disc Duo Palindrome (october 2002) with drummer Andrew Cyrille, ABCD (july 2003) with bassist Chris Dahlgren, Shadow Company (february 2004) with percussionist Milo Fine, Improvisations (may 2004) with pianist Walter Frank, Duo (may 2005) with British guitarist with Fred Frith.

Solo Willisau (september 2003) documented live solo alto saxophone pieces.

12+1tet (august 2007) was another work for large ensemble. The four-disc box-set 4 Improvisations (Duo) 2007 (july 2007) documents a collaboration with Joe Morris.

The four-disc Quartet Ghost Trance Music (may 2005) contains four compositions performed by Braxton on reeds, Carl Testa on bass, Aaron Siegal on percussion and Max Heath on piano.

Beyond Quantum (may 2008) documents five improvisations with bassist Milford Graves and drummer William Parker.

Quartet Moscow (june 2008) documents a live performance the 70-minute Composition 367B with Braxton on alto, soprano, sopranino and contrabass clarinet, Taylor Ho Bynum on cornet, flugelhorn, piccolo trumpet and bass trumpet, Mary Halvorson on electric guitar and Katherine Young on bassoon. >

The DVD release Nine Compositions 2003 (2008) compiles more of his "Ghost Trance Music": compositions number 328, 72, 74, 23, 190, 75, 292, 322, 327.

The double-disc Improvisations (july 2008) was a collaboration with pianist Maral Yakshieva.

Duo Heidelberg Loppem (march 2007) contains duets between Braxton (on sopranino, soprano and alto saxophones and contrabass clarinet) and bassist Joëlle Léandre.

The six-disc box-set, Standards (Brussels) 2006 (november 2006) collects live performances by a quartet formed with an Italian trio (pianist Alessandro Giachero, bassist Antonio Borghini, and drummer Cristiano Calcagnile).

The Anthony Braxton Quartet (Kevin O'Neil on guitar, Kevin Norton on percussion and Andy Eulau on bass) collected over 60 jazz standards on the multiple-cd sets 23 Standards(Quartet) 2003, 20 Standards (Quartet) 2003 and 19 Standards (Quartet) 2003. New originals surfaced on Composition 255 & 265 (2003), i.e. Composition 255, a saxophone duet with Jonas, and Composition 265, a trio with Jonas and vocalist Molly Sturges, and on Composition 339 & 340 (2007), duets with soprano Ann Rhodes.

Old Dogs (august 2007) is a quadruple-CD box-set that collects four studio inventions improvised by Braxton (here on Eb Sopranino, Bb Soprano, Eb Alto, C Melody, Eb Baritone, Bb Bass and Bb Contrabass saxes) and Gerry Hemingway (who sings and plays drums, marimba, vibraphone, samplers, and harmonica) to celebrate Braxton's 65th birthday.

Creative Orchestra 2007 (september 2007), a collaboration with an 18-member orchestra, includes compositions No. 306, 307 and 91.

Quartet (Mestre) 2008 documents a live performance of july 2008 of Composition 367c by himself (soprano & alto sax, contrabass clarinet and live electronics), Taylor Ho Bynum (cornet, flugelhorn, piccolo, bass trumpet, valve trombone), Mary Halvorson (electric guitar) and Katherine Young (bassoon).

6 Duos (Wesleyan) 2006 (july 2006) was a duo collaboration with trumpetist John McDonough.

Anthony Braxton's Septet Pittsburgh 2008 (may 2008) documents Composition No. 355, accompanied by Taylor Ho Bynum (flugelhorn, trombone, cornet, bass trumpet and piccolo trumpet), Jessica Pavone (violin, electric bass and viola), Jay Rozen (tuba), Mary Halvorson (guitar), Carl Testa (acoustic bass and bass clarinet), and Aaron Siegel (drums, percussion and vibraphone).

The four-disc box-set Trillium E (composed in 2000 but recorded in march 2010) contains his Composition No 237 - Opera in Four Acts for 12 vocalists, 12 solo instrumentalists and a 40-piece orchestra, the follow-up to Trillium A (staged in San Diego in 1985), Trillium M (premiered in London in 1994), and Trillium R (Composition n° 162). "There is no single story line in Trillium because there is no point of focus being generated. Instead the audience is given a multi-level event state that fulfills vertical and horizontal strategies".

Ensemble Pittsburgh 2008 (may 2008) delivered Composition 173, Composition 100, Composition 134 and Composition 165. as performed by 12 musicians conducted by Braxton himself. The double-disc Duets Pittsburgh 2008 (may 2008) was a collaboration with saxophonist Ben Opi that yielded Composition 220 (+ 278 & 29B) and Composition 340 (+ 173).

Credited to the duo Anthony Braxton/Buell Neidlinger, 2 BY 2: Duets (april 1989) was released only a decade later.

Creative Music Orchestra (NYC) 2011 (october 2011) is actually a performance by the Tri-Centric Orchestra conducted by Aaron Siegel, Jessica Pavone and Taylor Ho Bynum, a one-hour suite that also recycles old themes.

GTM (Iridium) 2007 Volume 1 - Set 1 (march 2007) contains Composition No.254 performed by a septet with Carl Testa (bass), Taylor Ho Bynum (cornet), Mary Halvorson (Guitar), Aaron Siegel (percussion), Jay Rozen (tuba) and Jessica Pavone (viola). Volume 1, Set 2 (march 2007) contains Composition No.322. Volume 2, set 1 (march 2007) contains Composition No.255. Volume 2, Set 2 (march 2007) contains Composition No.362. Volume 3 - Set 1 (march 2007) contains Composition No.259. Volume 3, Set 2 (march 2007) containes Composition No.362 Volume 4, set 1 contains Composition No.266 (april 2007) Volume 4, set 2 (april 2007) contains Composition No.348. All of them featured the same line-up.

Composition No. 376, off Echo Echo Mirror House (NYC) 2011 (october 2011), was scored for samples (played by all musicians on iPods) and jazz instruments (five saxes, bassoon, cornet, trombone, tuba, viola, violin, guitar, bass and percussion).

Tentet (Wesleyan) 1999 (november 1999) contains the colossal Composition 235 and Composition 236, performed with James Fei, Brian Glick, Chris Jonas, Steve Lehman, Seth Misterka and Jackson Moore (all, with the leader, on reeds), Kevin O'Neil (electric guitar), Seth Dillinger (contrabass) and Kevin Norton (percussion).

The live Echo Echo Mirror House (2011) contains Composition 347 for a septet with Taylor Ho Bynum (cornet, bugle, trombone), Mary Halvorson (electric guitar), Jessica Pavone (alto violin), Jay Rozen (tuba), AAron Siegel (percussion, vibraphone) and Carl Testa (bass and clarinet) and all of them also on iPods.

http://tricentricfoundation.org/

WELCOME TO TRICENTRICFOUNDATION.ORG

THE ONLINE HOME OF COMPOSER ANTHONY BRAXTON AND THE TRI-CENTRIC FOUNDATION

The Tri-Centric Foundation is a not-for-profit organization that supports the ongoing work and legacy of Anthony Braxton, while also cultivating and inspiring the next generation of creative artists to pursue their own visions with the kind of idealism and integrity Braxton has demonstrated throughout his long and distinguished career.

Specifically, TCF encourages broad dissemination of Braxton’s music through creation of, and support for, performances, productions, recordings and other new media technologies. It also documents, archives, preserves and disseminates Braxton’s scores, writings, performances and recordings and advocates for a broader audience,

appreciation, funding and support base for Braxton’s work.

This website also houses New Braxton House Records, releasing monthly download-only albums in addition to the 4-CD box set for Trillium E, the first-ever studio recording of a Braxton opera. Albums released by the old Braxton House imprint (1996-1999) and a curated collection of free bootlegs are also available in downloadable format for the first time.

June releases: Quartet (FRM) 2007 Vol. 1 & 2. Vol. 1 is member download, Vol. 2 is a la carte only. With Anthony Braxton, Erica Dicker, Katie Young, Sally Norris.

THIS MONTH'S RELEASE

(Free to Members!)

Quartet (FRM) 2007 Vol. 1

Recorded on December 6, 2007

Wesleyan Univeristy, CT

MEMBERSHIP:

For $7.99 per month, TCF members receive a free album-length download every month, in addition to 30% off all back-catalog digital items. Members also get surprise bonuses: exclusive free downloads, autographed merchandise, and invitations to concerts and events. All the proceeds directly support the ongoing activities of the Tri-Centric Foundation.

Home | The Tri-Centric Foundation

tricentricfoundation.org

New Braxton House Records

http://tricentricfoundation.org/anthony-braxton/writings/

WRITINGS BY ANTHONY BRAXTON:

GLOBAL MUSICS:

Africa: Triangle Land

‘Circle House’ No-1

African Ritual Funeral Music (Dogon Culture: Three Snapshots)

Jola Initiation Ritual: Mapping No-1

SCIENCE:

Known/The Unknown/and Belief

The Logic of Animate Behaviour

ISOLATED PAPERS

Africa: The Pulse Model Perspective

Architecture Style in West Africa

Cultural Fusion & Composite Reality

‘The First of the Mohicans’

Recognition and Change

Redemptive Transformation No-1

POETIC LOGICS:

The Clansman

Initial Encounters: (Ante-Bellum/Focus)

Pirandello: Transcendent Strategies

Story-Mythology Progressionism in Asia

The Jew of Malta

Allegory and Form

Tri-Centric-’Merchant’

Poetic Logics: Medieval Period

‘Moor or Less’

PHILOSOPHY:

Experience and ‘Surprise’

Narrative Structures

http://www.jbhe.com/2013/05/wesleyan-universitys-anthony-braxton-wins-225000-doris-duke-artist-award/

All,

While doing personal research on this extensive tribute and retrospective in honor of Anthony Braxton's 68th birthday on June 4 I ran across this very good news item (see below). So hearty congratulations are due Brother Braxton who is not only an outstanding multi-instrumentalist, musician and composer but a very fine person as well. For once the well worn accolade/cliche "it couldn't happen to a nicer or more deserving guy" actually applies in a number of different ways. To say I'm sincerely happy for him and all that he has thus far accomplished in an extraordinary career and life would be an understatement. Well done Anthony...

Kofi

Wesleyan University’s Anthony Braxton Wins $225,000 Doris Duke Artist Award

Filed in Honors and Awards on May 17, 2013

Anthony Braxton, the John Spencer Camp Professor of Music at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, received a 2013 Doris Duke Artist Award. The award program, established in 2011, supports performing artists in contemporary dance, theatre, jazz, and related interdisciplinary work. The award comes with a $225,000 honorarium.

Professor Braxton is a composer, saxophonist, and educator. He won a MacArthur Foundation genius award in 1994. During his long career, he has released more than 100 albums.

http://www.pointofdeparture.org/PoD37/PoD37Braxton.html

All,