https://www.allmusic.com/artist/orrin-evans-mn0000488518/biography

Orrin Evans

(b. March 28, 1975)

Biography by Thom Jurek

Orrin Evans is a jazz pianist, composer, and bandleader. He is well-versed in hard and post-bop, neo-soul, and R&B. In addition to leading dates, he is a prolific first-call sideman, and is particularly adept at backing singers. After woodshedding in various bands, he formed the Black Entertainment label in 1995 to release his leader debut, The Trio. He signed with Criss Cross in 1996 and worked in a number of contexts: On 1997's Justin Time he led a quintet, and followed with the acclaimed octet outing Captain Black in 1998. Two more quintet albums -- Grown Folk Bizness and Listen to the Band -- followed in 1999. Evans spent several years recording for Imani, issuing outings such as LuvPark in 2003 and Tarbaby's self-titled debut in 2006. In 2010, he issued three recordings in different settings for Posi-Tone including Tarbaby's The End of Fear, the live Captain Black Big Band, and Freedom with a quintet. Tarbaby and the Captain Black Big Band continued to record and tour with fluctuating lineups, but the pianist issued titles under his own name, too, including 2013's acclaimed trio set ...It Was Beauty and the live quintet date Liberation Blues -- his first for the Smoke Sessions label. In 2018, Evans replaced pianist Ethan Iverson in Bad Plus and they recorded the all-original Never Stop II followed by 2019's Activate Infinity. He left BP in the spring of 2021, and in July released The Magic of Now.

Evans was born in Trenton, New Jersey, but raised in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His mother, a classical opera singer, introduced him to music early and he began taking piano lessons as a child. The vastly musical city afforded him the opportunity to study -- informally -- with jazz legends such as Trudy Pitts, Shirley Scott, Mickey Roker, and others. He attended and graduated from the Girard Academic Music Program, and in 1993 was accepted into the Mason Gross School of The Arts at Rutgers University. While attending Mason Gross, he studied with Kenny Barron, Joanne Brackeen, Ralph Bowen, and Ted Dunbar.

Evans arrived in New York as one of the emerging class of Young Lions playing straight-ahead jazz, and hard bop in particular. Early on, he worked as a sideman with saxophonist Bobby Watson and drummer Ralph Peterson, as well as in the bands of Duane Eubanks, singer Lenora Zenzalai-Helm, and several others. In 1995 he set up the Black Entertainment label to release his debut leader date, The Trio, with bassist Matthew Parrish and drummer Byron Landham. Though the band played many club dates, Evans was busy working as a sideman with other musicians and couldn't undertake widespread touring.

He signed with Criss Cross in late 1996 and issued his label debut Justin Time in 1997, leading an "ortet" with Landham, trumpeter John Swana, saxophonist Tim Warfield (tenor sax), and bassist Rodney Whitaker. The record drew positive notice from critics. The octet outing Captain Black followed in 1998 with Warfield and Whitaker, but also included saxophonists Sam Newsome, Antonio Hart, and Ralph Bowen, as well as bassist Avishai Cohen and mentor Peterson on drums. 1999's Grown Folk Bizness offered a smaller version of the band, minus Warfield, Cohen, and Hart. Listen to the Band followed a year later and included drummer Nasheet Waits and Evans' old friend bassist Reid Anderson. Evans opened the new century with a new band, Seed, who issued a self-titled LP for Imani, as well as the quartet outing Blessed Ones -- with Eric Revis on bass -- and the mixed lineup outing Meant to Shine. What became obvious in observing the latter's personnel -- that included Revis, Bowen, and Newsome -- was how much stock Evans put into his personal and professional relationships: His recordings before and after this release feature many of the same players in ever-evolving settings; further, he is a first-call sideman for an astonishing variety of leaders.

In 2003, Evans formed Luvpark and issued its self-titled debut on Imani. In addition to Bowen, its lineup included drummer Donald Edwards, with guest vocals by his wife Dawn Warren-Evans and J.D. Walter. The following year he released Live at Widener University leading a quartet with Anderson, Waits, Newsome, and saxophonist J.D. Allen. After releasing Easy Now for Criss Cross, Evans formed the modernist Tarbaby, one of his most compelling bands. For its self-titled 2006 freshman offering, Evans brought back Allen, Revis, and Waits, and added young saxophonist Stacy Dillard. Tarbaby toured relentlessly with Evans adding and subtracting players in his lineup in order to accommodate busy schedules. In 2006 he issued Faith in Action; his first album for Posi-Tone, it featured Luques Curtis on bass. A revamped Tarbaby released The End of Fear in 2010, with trumpeter Nicholas Payton and saxophonist Oliver Lake playing alongside Allen, Waits, and Revis. The globally acclaimed album underscored Evans' ability to mold a slew of disparately matched players into a cohesive unit. That year also saw the release of a live self-titled offering from the Captain Black Big Band, and 2011's Freedom showcased a quintet outing that saw drummer/percussionist Byron Landham return to Evans' fold. 2012's Flip the Script indeed did, as one of Evans' somewhat rare trio offerings. The pianist worked on a slew of recordings that year, including Conrad Herwig's A Voice Through the Door and Wayne Escoffery's The Only Son of One. Evans returned to Criss Cross for It Was Beauty, with drummer Donald Edwards and a handful of alternating bass players. Tarbaby returned with two albums: Ballad of Sam Langford included Ambrose Akinmusire in the trumpet chair, while the live Fanon, recorded two years earlier, was released by RogueArt and included vanguard guitarist Marc Ducret in its lineup.

In 2014, Evans signed with the venerable jazz indie Smoke Sessions. His label debut was Liberation Blues with Curtis on bass and Bill Stewart on drums, and included guest spots from Allen and trumpeter Sean Jones, whose recordings Evans regularly appeared on. That year the pianist played on Edwards' Evolution of an Influenced Mind, and vocalist Michelle Lordi's debut album Drive. Evans closed out the year with Mother's Touch by the Captain Black Big Band.

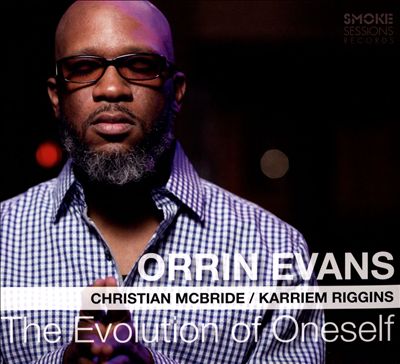

2015's The Evolution of Oneself proved a special album for the pianist. It was the very first time he'd recorded with bassist Christian McBride (a fellow Philadelphian) and Detroit drummer Karriem Riggins. Evans had shared an apartment with the pair during his early years in New York, and had worked with them on bandstands a few times, but this date marked the first time they shared a studio. The 18-track set included a stellar array of originals and standards -- including an iconic cover of Philly sax legend Grover Washington, Jr.'s "A Secret Place" -- and featured guest guitarist Marvin Sewell on a few tracks. That year Evans also played on Warfield's Spherical: Dedicated to Thelonious Sphere Monk, and on vocalist Joanna Pascale's fourth album Wildflower. The following year, Evans released #knowingishalfthebattle with a lineup that included alternating guitarists Kurt Rosenwinkel and Kevin Eubanks, Mark Whitfield, Jr. on drums, and Curtis on bass. Captain Black Big Band's Presence was also released that year, and he guested on albums by Eubanks, Josh Lawrence, and Jones.

In 2018, the Bad Plus simultaneously announced the departure of founding pianist Ethan Iverson and Evans replaced him for the release of Never Stop II. Like its 2010 predecessor, it uncharacteristically featured only original material. In 2019, Evans toured intensely with the Bad Plus, and released the Captain Black Big Band's The Intangible Between.

In October the Bad Plus' new label, Edition Records, debuted with Activate Infinity to near-universal critical acclaim. Evans' tenure with the trio proved short-lived, however; in the spring of 2021 he announced his departure. In July he released The Magic of Now on Smoke Sessions, leading a quartet that included Stewart on drums, bassist Vicente Archer, and 23-year-old alto saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/orrin-evans

Orrin Evans

The New York Times described the pianist as "...a poised artist with an impressive template of ideas at his command", a quality undoubtedly recognized by the legendary saxophonist Bobby Watson who engaged Evans as piano chair for his band, a position he has held for six years. Orrin has recorded with Bobby on Live and Learn (Palmetto Records), Quite as it's Kept (Red Records) which features one of Orrin's original compositions "Looking in Your Eyes". Bobby also recorded another of Orrin's compositions "Two Stepping with Dawn" on Bobby Watson & Curtis Lundy Project (Sound Hills Records). Orrin has been playing with the Charles Mingus Big Band for the past three years. He has also toured with such diverse talents as the evolutionary Wallace Roney, Stefon Harris, and Antonio Hart.

For Orrin Evans, however, the greatest joy is playing his own band which, at different times, has included such notables as the aforementioned Ralph Peterson, Sam Newsome, Ralph Bowen, Nasheet Waits, Reid Anderson, John Swana and Duane Eubanks. Besides touring and recording, Evans is also a teacher and musical commentator, having conducted workshops, clinics and master classes both in The United States and abroad. When not on the road, he teaches privately. The newest Orrin Evans adventures are; "Meant to Shine", his latest cd on the Palmetto Records label, two projects on his own label, IMANI Records, one from the group SEED, and "Dejavu" by the Orrin Evans Trio, (both available online).

Orrin Evans

Orrin Evans (born 28 March 1975)[1] is an American jazz pianist. Evans was born in Trenton, New Jersey and raised in Philadelphia.[2] He attended Rutgers University, and then studied with Kenny Barron.[2] He worked as a sideman for Bobby Watson, Ralph Peterson, Duane Eubanks, and Lenora Zenzalai-Helm, and released his debut as a leader in 1994. He signed with Criss Cross Jazz in 1997, recording prolifically with the label. He was awarded a 2010 Pew Fellowships in the Arts.[3]

In 2017, Evans was named the new pianist in The Bad Plus replacing Ethan Iverson.[4]

Evans is married to Dawn Warren Evans, who is his manager and an occasional vocalist.[5]

Discography

As leader

Year recorded

1995 The Trio Black Entertainment With Matthew Parrish (bass), Byron Landham (drums); reissued in 2001 as Deja Vu on Imani

1996 Justin Time Criss Cross With John Swana (trumpet), Tim Warfield (tenor sax), Rodney Whitaker (bass), Byron Landham (drums)

1997–98 Captain Black Criss Cross With Sam Newsome (soprano sax), Antonio Hart (alto sax), Ralph Bowen (tenor sax, soprano sax, alto sax), Tim Warfield (tenor sax), Avishai Cohen (bass), Rodney Whitaker (bass), Ralph Peterson (drums)

1998 Grown Folk Bizness Criss Cross With Sam Newsome (soprano sax), Ralph Bowen (tenor sax, alto sax), Rodney Whitaker (bass), Ralph Peterson (drums)

1999 Listen to the Band Criss Cross With Duane Eubanks (trumpet), Sam Newsome (soprano sax), Ralph Bowen (tenor sax, alto sax), Reid Anderson (bass), Nasheet Waits (drums)

2000 Seed Imani As Seed, with Mike Boone (bass), Rodney Green (Drums), and Dawn Warren (Vocals)

2001 Blessed Ones Criss Cross With Eric Revis (bass), Nasheet Waits and Edgar Bateman (drums)

2002 Meant to Shine Palmetto With Eric Revis (bass), Gene Jackson (drums); some tracks with Sam Newsome (soprano sax) added; some tracks with Ralph Bowen (tenor sax, bass clarinet, flute, soprano sax) added

2003 Luvpark Imani As Luvpark; with Ralph Bowen (sax), Donald Edwards (drums), J. D. Walter and Dawn Warren (vocals)

2004 Live At Widener University Imani As The Band, with J. D. Allen (tenor sax), Sam Newsome (soprano sax), Reid Anderson (bass), and Nasheet Waits (drums)

2004 Easy Now Criss Cross With Ralph Bowen (soprano sax, alto sax), Mike Boone and Eric Revis (bass), Byron Landham and Rodney Green (drums)

2006? The Trio – Live in Jackson, Mississippi Imani Trio, with Madison Rast (bass), Byron Landham (drums); in concert

2006 Tarbaby Imani As Tarbaby; with Stacy Dillard and J. D. Allen (tenor sax), Eric Revis (bass), Nasheet Waits (drums)

2009 Faith in Action Posi-Tone With Luques Curtis (bass), Nasheet Waits, Rocky Bryant and Gene Jackson (drums)

2010? The End of Fear Posi-Tone As Tarbaby; with J. D. Allen (tenor sax), Oliver Lake (alto sax), Nicholas Payton (trumpet), Eric Revis (bass), Nasheet Waits (drums )

2010 Captain Black Big Band Posi-Tone As Captain Black Big Band; in concert

2010 Freedom Posi-Tone With Larry McKenna (tenor sax), Dwayne Burno (bass), Byron Landham (drums, percussion), Anwar Marshall (drums)

2011 Fanon RogueArt As Tarbaby; with Oliver Lake (alto sax), Marc Ducret (guitar), Eric Revis (bass), Nasheet Waits (drums)

2011 Mother's Touch Posi-Tone As Captain Black Big Band

2012 Flip the Script Posi-Tone With Eric Revis, Ben Wolfe, Alex Claffy and Luques Curtis (bass), Donald Edwards (drums)

2013 ...It Was Beauty Criss Cross With Eric Revis (bass), Donald Edwards (drums)

2013 Ballad of Sam Langford Hipnotic As Tarbaby; with Oliver Lake (sax), Ambrose Akinmusire (trumpet), Eric Revis (bass), Nasheet Waits (drums)

2014 Liberation Blues Smoke Sessions With Sean Jones, J. D. Allen, Luques Curtis (bass), Bill Stewart (drums); in concert

2014 The Evolution of Oneself Smoke Sessions[6] With Christian McBride (bass), Karriem Riggins (drums); two tracks with Marvin Sewell (guitar) added; one track with J. D. Walter (vocals) added

2016 #knowingishalfthebattle Smoke Sessions Some tracks trio, with Luques Curtis (bass), Mark Whitfield Jr. (drums); Kurt Rosenwinkel and Kevin Eubanks (guitar), Caleb Wheeler Curtis (sax and flute), M'Balia Singley (vocals) are added on some tracks

2016 Presence Smoke Sessions With the Captain Black Big Band; Troy Roberts (tenor sax), Caleb Wheeler Curtis and Todd Bashore (alto sax), John Raymond, Josh Lawrence and Bryan Davids (trumpet), David Gibson, Stafford Hunter and Brent White (trombone), Madison Rast (bass), Anwar Marshall and Jason Brown (drums)

2019 The Intangible Between Smoke Sessions With the Captain Black Big Band; Troy Roberts (tenor sax), Stacy Dillard (tenor and soprano sax), Immanuel Wilkins (alto and soprano sax), Todd Bashore (flute and alto sax), Caleb Wheeler Curtis (alto sax), Sean Jones, Josh Lawrence and Thomas Marriott (trumpet), David Gibson, Stafford Hunter and Reggie Watkins (trombone), Dylan Reis, Eric Revis, Luques Curtis and Madison Rast (bass), Mark Whitfield Jr., Anwar Marshall and Jason Brown (drums)

2021 The Magic Of Now Smoke Sessions With Vicente Archer (bass), Bill Stewart (drums), Immanuel Wilkins (alto sax)

Ravi Coltrane says that Orrin Evans, above, “can reach that spirit.” (Photo: John Rogers)

On an early summer night in newly vaccinated New York, the Blue Note was packed with cheering clubgoers. And pianist Orrin Evans, coming off the first set, was, in his understated way, one of them.

True, the set had had its unsettling moments, among them a rumbling protest by Evans’ food-deprived stomach, an underamplified piano and a spottily lit stage that threatened to dampen what was the Ravi Coltrane Quartet’s post-COVID return to the Big Apple.

But the group seemed to feed off the snafus — no one more than Evans, a coolly commanding figure who alternately thundered and threaded his way through tunes by Alice Coltrane, Ornette Coleman and Charlie Parker. Now, affixed to a stool at the bar between sets, he was seeking sustenance and pondering the totality of a musician’s plight.

“Sometimes you’re fighting the elements,” he said, downing a drink. “You can give up or you can turn it up and go for it.”

Evans has been going for it for most of his 46 years. Sometimes that has meant running from it — specifically, he said, the specter of McCoy Tyner, another powerful Philadelphia pianist to whom he has been compared countless times. That association has only been strengthened by Evans’ longtime connection with saxophonist Ravi Coltrane, son of the jazz icon who famously led the trailblazing quartet of which Tyner was an integral part.

If Evans is like Tyner, the similarity is reflected less in his choice of notes than in an ineffable quality that allows him, by his mere presence, to raise the game of those around him. That is why, when Tyner died on March 6 of last year, Coltrane recruited Evans to play the next night on a Tyner tribute — a high-flying affair that became one of the last performances on the Blue Note stage before the COVID lockdown.

“He can reach that spirit,” Coltrane said.

Evans’ spirit has infused his COVID-era activities. His livestream series serves as a perfect example. Run weekly from the patio of his home or, on rainy days, from a studio in nearby Glendale, Pennsylvania, the series provided a reliable link to inspired musicmaking and the occasional lesson in adaptability. One set, at the studio on a Sunday before the Blue Note gig, found Evans forced to make do with the available electric piano — a category of instrument he professed to “despise” playing — adjusting his touch to conjure two hours of sonorous display.

The series has not come cheap; the Glendale set required securing the space and the services of talents like vibraphonist Warren Wolf, bassist Buster Williams and drummer Clarence Penn. Nonetheless, Evans said, he has strived to make the sets available for free, even as he acknowledged that, with voluntary donations declining as venues reopen, the series would likely end this summer.

While running this series, Evans has played at others. Notably at Smalls, the Greenwich Village basement that turned to a nonprofit model to keep the music going. Though the space was closed to the wider public during the lockdown livestreams, Evans appeared at one at which trombonist David Gibson, a stalwart of his Captain Black Big Band, dropped in. Instrument in hand, he enlivened the subterranean party — and kept the big-band connection alive.

But the peak of Evans’ livestream efforts may have been a two-night marathon at Smoke, the cozy room on upper Broadway operated by Paul Stache, who also runs the Smoke Sessions recording label, on which Evans’ recent albums have been released. The two nights, in December, have yielded The Magic Of Now, a seven-track collection.

During a Zoom call, Evans said turning the livestream into an album was an afterthought: “It’s so hard to have a conversation about this record as a record when it wasn’t ever supposed to be a record. This was truly a party, an opportunity in the middle of the pandemic to get together and play some music with some humans — something that wasn’t happening in that time.”

For the livestream, Evans enlisted two veterans, bassist Vicente Archer and drummer Bill Stewart, and 23-year-old alto saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins. Not long out of Juilliard, Wilkins’ star had been rapidly rising with the release four months earlier of his acclaimed debut album, Omega (Blue Note). But Evans said he first met Wilkins more than a decade ago, when the saxophonist was a participant in youth programs run by the Kimmel Center and Clef Club in Philadelphia.

“What impressed me about Immanuel was how mature he was, his sense of fashion and the way he carried himself,” Evans said.

For his part, Wilkins, in a phone interview, recalled Evans as a constant figure in the lives of local aspiring musicians: “He was just always kind of around as somebody who was doing stuff with our heroes and was one of our heroes. He was kind of our connection to any of that.”

In 2016, when Wilkins arrived in New York, Evans offered him work in his well-regarded Smoke series, Philly Meets New York. The gig, Wilkins said, introduced him to Evans’ first-take mentality; “I didn’t realize how loose Orrin is. He has a particular approach to bandleading, which is pretty much all about spontaneity. It comes through in the way that he leans into that initial reaction to the music.”

Wilkins’ first encounter with Evans at a recording session came with an invitation to play on the Captain Black Big Band album The Intangible Between (Smoke Sessions). Recorded in October 2019 and released in May 2020, the album, which earned a Grammy nomination, thrust him into a cutting contest with longtime Captain Black saxophonist and arranger Todd Bashore. The vehicle was “That Too,” a spiky piece Evans wrote for the WDR Big Band. The verdict, inevitably, was a draw.

“‘That Too’ is about the flexibility of being able to play with other people and still get what you need out of them for your band,” Evans explained. “The band has had Todd Bashore in it for years. Then there’s Caleb Wheeler Curtis and Stacy Dillard. But now, here’s Immanuel Wilkins, somebody I’ve seen grow. Here’s Todd Bashore’s solo; here’s Immanuel Wilkins’ solo. Which is better? Neither.”

Encouraging a meeting of minds by means of a ritual trial-by-fire is vintage Evans. “The music is always all about connection,” Gibson said. “That’s what makes Orrin the leader he is. He has this ability to invite everyone to contribute to the conversation. He may even press back to allow you to get a firmer footing.”

As a player on The Intangible Between, Wilkins more than proved his mettle. But Evans hired him for the December livestream more to explore his compositions, which gave the event a blueprint. Without it, Evans said, “There is no story. The best story is the good margaritas we got across the street, and then we just came and played two nights of music, two sets of music, and listened back and said, ‘Wow.’

“The only ‘plan’ was to play some of Immanuel’s music. I really like playing Immanuel’s music. I love his ballads.”

Wilkins’ balladic contribution to the album, “The Poor Fisherman,” is epic. Written in his junior year at Juilliard and based on an 1881 painting of that name by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, it is a work of melancholy and, according to Wilkins, an ode to the Trinity. Suggested by the painting’s images — a series of triangular patterns featuring Jesus-like figures — the music is built around three tonal centers with an overarching melodic structure.

“I was letting the melody guide me,” Wilkins said.

Even without knowing the story behind the piece, Evans said he embraced it as a kind of trippy journey. “Immanuel’s ballads are so beautiful, and they allow you to really, truly improvise. It’s a language everybody can’t do. You feel like you’re going to different islands on one song, and they feel like they’re connected. You’re just picking up different things before you get home.”

The performance makes clear the full range of Evans’ pianistic powers as his natural muscularity is superseded by an equal and opposite passion for delicacy. Picking up on Wilkins’ fluttery effusions, he favors strings of exquisitely rendered lines that seem to traverse the painting’s turf. The painter’s spirit comes alive.

His gentle side reemerges in a deceptively prosaic “Dave,” the album’s closer. Evans wrote the tune for saxophonist Bill McHenry, whose presence as a houseguest one holiday season proved an inadvertent inspiration when Evans’ mother-in-law, also a guest, inexplicably kept referring to Bill as Dave despite being corrected.

“I thought it was the most hilarious thing,” Evans said. “So I sat down at the piano and started playing that little melody and came up with the name ‘Dave.’”

The melody’s repeated figure becomes a mantra that suggests a simple meditation. But the real message — one of personal responsibility — is brought home near the end as a creeping dissonance roils the narrative, only to resolve to a harmonious conclusion.

“The first two bars are you knowing what needs to be done,” Evans explained. “The second two bars are you not doing it. And hopefully that comfortable Stevie Wonder cadence at the end is you dealing with what needs to be done. It’s really a song about seeing what you want to see, about seeing what’s comfortable rather than dealing with what really needs to be dealt with.”

That “Dave” closes the album makes sense. The need for personal responsibility is central to Evans’ ethos, musical and otherwise. It reaches back to a childhood shaped in no small measure by his father, playwright Donald T. Evans, a figure in the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and ’70s whose fictitious scenarios, Evans said, often foretold the dynamic in their home.

The elder Evans’ death in 2003 hit Evans hard; his spare, mournful rendition of Horace Silver’s “Song For My Father” — the track that appears on 2005’s Easy Now — attests to the depth of his pain. So, perhaps, does his assertion when asked whether “Orrin,” the playwright’s domestic drama about a wayward son at odds with his father — produced in New York in 1972 — bore any relationship to reality.

“I hope not,” he said.

While grief might not be central to Evans’ aesthetic, he does make space in his songbook for homages to recently fallen colleagues, like drummer Lawrence Leathers (his plaintive “I’m So Glad I Got To Know You”) and trumpeter Roy Hargrove (Gibson’s astute arrangement of Hargrove’s “Into Dawn”). Both tributes appear on The Intangible Between.

At the keyboard, Evans said, he keeps the possibility of imminent demise in his thoughts: “I always prefer to do things as if it were my last day on earth. That might sound morbid to some, but when I jump on the bandstand I want to play like that, when I jump into the studio I want to play like that.”

To be sure, death has touched Evans during the COVID era. As he traveled to the Blue Note for the Tyner tribute last year, he said, he resolved to act on long-delayed plans to record with Williams, drummer Gene Jackson and trumpeter Wallace Roney. He did so four days later, and by the end of the month Roney had succumbed to the virus. Evans’ godparents followed.

But now, he was back at the Blue Note and looking at bluer skies. After a three-year run with The Bad Plus, he has left the trio — on good terms, he said — to pursue more of his own projects. He has recordings in the can, including a duo with guitarist Kevin Eubanks. He has set summer release parties for The Magic Of Now at New York’s Birdland and Philadelphia’s South. And he is negotiating a residency for the big band. All of which, he said, allow for a bit of cheer.

“Music deserves some credit for being just as fine and sexy as she was, as he was, pre-pandemic,” he said. “So many people came out of this still in love with her, still in love with him. That’s how I look at this pandemic. It either strengthened your love or showed you some other options.” DB

In the booklet notes for Orrin Evans’ second album, Captain Black, recorded in 1998, the pianist, then 23, made a remark that encapsulates the aesthetic he’s followed ever since on his kaleidoscopic artistic journey. “I go head-first for a lot of things,” Evans said. “I like to stretch out. Wherever the music takes me, I’m going there.”

That attitude backdrops the title of Evans’ 20th album, Magic of Now (Smoke Sessions), which documents a livestream engagement at Smoke Jazz Club during the second weekend of December 2020. Evans and a multi-generational cohort of A-list partners – first-call New York bassist Vicente Archer; iconic drummer Bill Stewart; and dynamic rising star alto saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins, now 23 himself – generate an eight-piece program that exemplifies state-of-the-art modern jazz. From the first note to the last, the quartet, convening as a unit for the first time, displays the cohesion and creative confidence of old friends, mirroring the leader’s predisposition for finding beauty in the heat of the moment.

As he does on five prior albums for Smoke Sessions, eight self-issued albums on Imani Records (his imprint), and earlier recordings for Criss Cross, Palmetto and Posi-Tone, Evans guides the creative flow from the piano, showcasing his authoritative mastery of his instrument and deep assimilation of the fundamentals. A deft tune deconstructor, he traverses a broad timeline of the vocabularies of swinging, blues-infused hardcore jazz and spiritual jazz/avant garde jazz traditions, as well as the Euro-canon, with the intuitive spontaneity of an ear player. He projects an instantly recognizable sound, sometimes eliciting flowing rubato poetry, sometimes evoking the notion that the piano comprises 88 tuned drums. It’s taken a while, but the jazz gatekeepers have noticed – in 2018, Evans topped the “Rising Star Pianist” category in DownBeat Critics Poll, and a feature article about him appears in DownBeat’s September 2021 edition.

Evans’ stylistically polyglot compositions – influenced by the expansive, individuality-first Black Music culture of his native Philadelphia and by a decade playing Charles Mingus’ beyond-category music in the Mingus Big Band – similarly postulate an environment of “structured freedom” that instigates the personnel to push the envelope in all his multifarious leader and collaborative projects.

In none of Evans’ units of recent years is that no-holds-barred attitude more prevalent than the Captain Black Big Band, a communitarian-oriented ensemble whose fourth and latest album is The Intangible Between (Smoke Sessions), preceded by Presence (Smoke Sessions). Both earned Grammy nominations.

A more recent venture is the Eubanks Evans Experience, a duo in which Evans and eminent guitarist Kevin Eubanks extemporize on repertoire spanning Tom Browne to Geri Allen. (Eubanks and Kurt Rosenwinkel, both fellow Philadelphians, played on Evans’ #knowingishalfthebattle [Smoke Sessions] in 2016.) “EEE” debuted in the pre-Covid winter of 2020; they will resume public performance in spring 2022, behind a new recording.

Also on Evans’ 2022 docket are gigs by Terreno Comum, a Brazilian project for which, responding to a commission from the Pittsburgh Jazz Festival, he convened bassist Luques Curtis and drummer Clarence Penn along with Brazilians Alexia Bomtempo (vocals) and Leandro Pellegrino (guitar).

Curtis and drummer Mark Whitfield, Jr. – who played on #knowingishalfthebattle and The Intangible Between – are Evans’ partners in his working trio, which also comprises the rhythm section for the great trumpeter Sean Jones.

Evans is also deeply involved in Tar Baby, a freewheeling unit with bassist Eric Revis and drummer Nasheet Waits that has embodied the equilateral triangle concept of the piano trio since they convened in 2001 to make Blessed Ones for Criss Cross. In 2022, the French label RogueArt will release a 2015 Tar Baby recording with guest alto saxophonist Oliver Lake, while Evans’ Imani imprint will release a newer session on which the trio – joined by guest saxophonists Branford Marsalis, J.D. Allen and Bill McHenry – performs tunes from the jazz canon.

Evans and his wife, Dawn, founded Imani in 2001 as a vehicle for Evans to release leader projects that couldn’t otherwise find a home. The label relaunched in 2018, with the release of albums by saxophonist Caleb Wheeler Curtis and bassist Jonathan Michel.

In creating and operating Imani Records, in organizing bands that navigate streams of expression outside his wheelhouse, in booking venues from the Philadelphia room Blue Moon (where he ran a Monday jam session from his late teens until early twenties) to the D.C. Jazz Festival (which recently appointed him Artist in Residence), Evans drew inspiration from his parents. His father, Donald Evans, was a playwright and educator who self-produced his plays; his mother, Frances, an opera singer who put on concerts in various alternative venues.

“I like to make things happen,” is a key Evans mantra. Another is the notion that the broad network of musicians with whom he intersects – including the members of his various bands – comprise an extended family, or village. “I like to connect the dots, get a bunch of people together and see what happens from that mix,” he says, referring to an as-yet unreleased multi-generational Philadelphia-centric project with local saxophone legend Larry McKenna, the late master trumpeter Wallace Roney, and drummer Gene Jackson.

More recently Evans curated the concert series “What’s Happening Wednesdays” at South Jazz Kitchen, which exposed Philadelphia audiences to important national artists; and “Philly Meets New York,” which brought Philadelphia talent to Smoke Jazz Club in Manhattan.

Evans applied both his entrepreneurial and curatorial sides during the Covid summer when he set up Club Patio, a series of livestreamed outdoor concerts in front of his Philadelphia home with the likes of Jeff Tain Watts, Buster Williams, Russell Malone and a host of other luminaries. “It’s simple,” he says. “I love people. And I love community. My door is open. When the pandemic shut things down, I decided to do it on my patio so I could still see people. It’s great to introduce a trombonist from Pittsburgh to a saxophonist from Philadelphia and see them do a concert 10 months later.”

During formative years, Evans – who made his first album, Justin Time (Criss Cross), at 21 – learned about diving into the deep end of the pool in the sink-or-swim milieu of Philadelphia’s jam sessions where world class artists like pianist Shirley Scott, Trudy Pitts and Sid Simmons, bassists Arthur Harper and Charles Fambrough, and drummer Mickey Roker served as de facto mentors. During his early twenties he received similarly illuminating tough love from taskmaster leaders like Bobby Watson, Branford Marsalis and Ralph Peterson. Thus nurtured, he’s displayed reverence for legacy and roots by leaving the nest and creating one of his own.

In addition to teaching on the bandstand, Evans has conveyed knowledge in more formal contexts. For a full year, he curated weekly jazz curriculum in Philadelphia public schools, sponsored by the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts’ Jazz Standards programming division. For three years he instructed high school students at Germantown Friends School. He’s served on the faculty of Connecticut’s Litchfield Jazz Camp since 2013 (one student was the phenomenal 15-year-old pianist Brandon Goldberg) and the Kimmel Center Jazz Camp, headed by bassist/producer Anthony Tidd (where Evans taught Immanuel Wilkins).

“I’m learning every day,” Evans says. “If someone calls to ask if I have a Brazilian project, I won’t say no. I’ll dive into it, call some great Brazilian musicians and put together a Brazilian project. If someone asks if I have a big band, I’ll educate myself and try to put a big band together. I don’t know how to sit and wait.”

© 2022 Orrin Evans. All rights reserved | Photography by Christopher Kayfield | Web Design by JohnChristensenWebDesign.com

https://orrinevansmusic.com/discography/

https://orrinevansmusic.com/projects/

https://orrinevansmusic.com/portfolio/captain-black-big-band/

Captain Black Big Band

Boasting a raw, vigorous sound, a raucous, unpredictable vibe, and a membership ranging from elders to rising stars, the Grammy nominated Captain Black Big Band has rapidly seized the attention of the jazz world to become one of the most vital big bands on the modern scene. That’s no surprise given the leadership of pianist/composer Orrin Evans, who imbues the ensemble with his distinctively bold, bracing sensibility.

Founded in late 2009, Captain Black was conceived as a vehicle for Evans to combine the power and scale of a big band with the freedom and spontaneity of a small group. From its beginnings at Chris’ Jazz Cafe in Evans’ native Philadelphia through its long-running Monday night residency at New York’s Smoke Jazz & Supper Club, the band has evolved into just that — a flexible and tightrope-walking unit whose daring approach lends the music an exhilarating edge.

The band now has two critically-acclaimed albums to its name — its 2011 self-titled debut and 2014’s Mother’s Touch (both Posi-Tone) — with a third due this winter via the Smoke Sessions label. They were named Rising Star Big Band of the Year in the 61st annual DownBeat Critics Poll, and placed in the top five for Big Band of the Year in the most recent poll. The magazine’s review called Mother’s Touch “extraordinary… a sweet summertime powerhouse of a record that slips and slides with breathtaking compositions, arrangements, solos and grandeur.”

More recently the band has been called upon for more ambitious projects, including two high-profile commissions: a suite honoring the centennial year of cosmic bandleader Sun Ra, premiered at Jazz at Lincoln Center; and another inspired by Thomas Hart Benton’s mural “America Today,” performed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art accompanied by scrolling photos of the artwork.

Captain Black’s origins can be traced back to 2007, when Evans was invited to lead a big band at Portugal’s Guimaraes Jazz Festival. As a longtime member of the Mingus Big Band, he had years of experience performing with a large ensemble, but the success of that concert convinced him to try to lead his own big band, despite the obvious financial and logistical obstacles. It was christened for Evans’ father’s preferred brand of tobacco, which had previously lent its name to Evans’ 1998 Criss Cross release Captain Black.

The band’s original incarnation was largely culled from students in the jazz programs at Philly’s Temple University and University of the Arts, supplemented by veteran players from Evans’ New York rolodex. By the time of the band’s debut album, recorded live at Chris’ Jazz Cafe and at New York’s Jazz Gallery, the line-up included such notable names as saxophonists Tia Fuller, Wayne Escoffery, Tim Warfield, and Jaleel Shaw; trumpeters Duane Eubanks and Jack Walrath; trombonist Frank Lacy; bassists Mike Boone and Luques Curtis; and drummers Donald Edwards and Gene Jackson. Mother’s Touch added names like saxophonists Stacy Dillard, Tim Green and Marcus Strickland; trombonist Conrad Herwig; and drummer Ralph Peterson.

The band has become more compact over time, reduced from 17 to 10 pieces, without losing its forceful identity. It features a rotating cast of brilliantly skilled talent, including saxophonists Todd Bashore, Victor North, Chelsea Baratz, Mark Allen; trumpeters Tatum Greenblatt, Josh Lawrence, Tanya Darby, Brian Kilpatrick; trombonists David Gibson, Stafford Hunter, Brent White; and drummer Anwar Marshall.

Since its beginnings, Evans has given ample credit for Captain Black’s success to the arrangers who transform his and other composers’ work into raw material for the band to bring to life. Both trombonist David Gibson and saxophonist Todd Bashore have not only contributed a wealth of arrangements but both step in to lead the band when Evans is touring or pursuing other projects. The pianist now sees the ensemble like a father views a child — as an independent entity with its own life, in which he plays a continuing and key part. The child remains recognizable, however, sharing its father’s penchant for risk-taking, robust expression, and independent vision.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/21/arts/music/orrin-evans-the-bad-plus.html

The New Vanguard

Orrin Evans Has Been Playing Jazz for Years. So Why Is He a Rising Star?

PHILADELPHIA — When the renowned power trio the Bad Plus announced in 2017 that Orrin Evans would come aboard, replacing its founding pianist Ethan Iverson after nearly 18 years, it was a moment to stop and wonder. No one expected this. But why did it seem to make such devilish sense?

In some ways the news marked a kind of arrival for Mr. Evans. At 43, based for most of his career in Philadelphia, he had never been on the cover of a major jazz magazine, and all of his roughly 25 albums as a leader have come out on small labels. He has spent over two decades stubbornly committed to his own vision as a musician and community leader, but he’s never been fully accepted as a marquee bandleader, perhaps because of his proudly unpretentious persona.

Still, his arrival might have been an even bigger blessing for the Bad Plus. Though under-hyped, Mr. Evans is a viable candidate for jazz’s most resourceful and invigorating contemporary pianist. He is probably the closest heir we have to Geri Allen — the first postmodern piano master in jazz, who died last year at 60 — and a homier counterpart to the pianist Jason Moran, a MacArthur fellow and leading figure in improvised music.

In DownBeat magazine’s annual critics poll this year, Mr. Evans, propelled by the Bad Plus hype, won the “Rising Star” award among pianists. It was a victory with a sour aftertaste: He already has decades of work behind him, and by now is considered an elder statesman by a fleet of younger musicians.

Sorting through a sheaf of old musical scores in the dim light of his basement on a recent evening, Mr. Evans puzzled at the DownBeat accolade. “I’m not looking down on it, but I’m just like: If I had waited on you, I’d have been a falling star,” he said, addressing the critical establishment. “There was no way I was going to wait on you to tell me when I’m a star.”

The Bad Plus — a collective trio lugging almost two decades of its own history behind it, with an arm’s-length relationship to the black musical tradition — would seem a strange vessel of deliverance for Mr. Evans. But he has adapted quickly, and has made gentle adjustments to the band’s approach, rearranging the furniture if not knocking down entire walls.

At his first New York show with the group, at the Blue Note in May, playing “1972 Bronze Medalist,” an old standby composed by the drummer Dave King, Mr. Evans pumped a mercurial sway into the piece’s chunky, heavy-knit chords. Still, he wasn’t softening or smoothing things down: His right hand kept a loopy, almost inebriated feel as it traced the odd melody, and he pulled Mr. King and the bassist Reid Anderson even more deeply into their caustic groove.

“He has such astonishing technique and touch that he always makes my music sound better,” Mr. King said in an interview. “A lot of my music from the old book has been reborn under Orrin.”

Since the mid-1990s, Mr. Evans has led a range of outstanding bands, composing and recording nonstop while also mentoring scores of younger musicians. The home he shares with Dawn Warren Evans, his wife and creative partner, has long been a kind of community gathering place. Meanwhile, he’s kept up a busy touring schedule as a side musician for artists like David Murray and Sean Jones. And he also continues to play here and there with Tarbaby, an all-star trio featuring the bassist Eric Revis and the drummer Nasheet Waits, which has an impressive new album on the way.

The most representative project of Mr. Evans’s personal ethic is his Captain Black Big Band, a Philadelphia-based group that’s a family as much as an ensemble. On Friday, the Smoke Sessions label released “Presence,” the band’s third album. Captain Black grew out of a weekly residency at Chris’ Jazz Café 10 years ago, and the new album features live recordings from Chris’ and another Philadelphia club, South.

“When we started the band, we weren’t making much money, but the energy was so great in the room each weekend,” Mr. Evans said. “That’s what’s really important about this band: Not just the people on the bandstand, but the people in the audience.”

On “Presence” the group has slimmed down from 17 pieces to nine, allowing it a looser, more rugged range of motion while still illuminating the layers of harmonic fortification that Mr. Evans builds into his music. And the music is not just his own: Half of the tunes on “Presence” were composed by other band members.

“The charts are movable, which is really important,” Mr. Evans said. “Everybody is like, ‘All right, well let’s try this. Let’s open this section up.’ No one’s saying, ‘Don’t mess up my tunes!’ Everybody’s amenable to change.”

Mr. Evans was born in Trenton, N.J., in 1975, and moved to Philadelphia as a child. His mother, Frances Gooding, was an opera singer, and his father, Don Evans, was a well-known playwright and professor. In grade school Orrin took lessons from musicians around Philadelphia, then spent a couple of years studying jazz at Rutgers University, but eventually dropped out.

He was interested in a liberated approach, unconcerned with the divide between the free-improvising avant-garde and Philadelphia’s more soul-adjacent straight-ahead-jazz world. He never quite found a teacher who could give him the full spectrum, so he went his own way.

“Some of the older people I met in Philly, they were very supportive, but they also didn’t know how to deal with me. I understand that now, because I was on a different track,” he said. “I always had a drive not only to compose but to be a bandleader.”

He added: “If it wasn’t for my mother and particularly my father, I don’t know if I would have continued down that track.”

By the mid-1990s, when he began releasing records under his own name on the Criss-Cross imprint, Mr. Evans’s style had cohered into something commanding and distinctive. On early albums like “Captain Black” (a small-group effort, not with the big band) and “Deja Vu,” he offered magnetic up-tempo compositions and plangent ballads, usually with a hint of melancholy at every speed.

At first, it can be easy to hear his playing and think you’re listening to a mainline jazz musician — perhaps a close acolyte of the post-bop doyen Cedar Walton. But that’s missing Mr. Evans’s vast library of personal innovations. One signature is his way of riding a fast swing feel, bustling to the point of bursting, its momentum built of weight more than speed. Often he’ll land on an ostinato pattern, repeating an insistent phrase until it becomes its own song. Then there’s his way of lacing harmonies together, giving a subtle emphasis to a single note within each chord. By shining a light on particular tones, he makes his juicy-red clusters of harmony feel crisp and narrative.

And when Evans veers outward, toward a free-jazz style, he never seems to be going for esotericism or abstraction. If he delivers a scalding smash of dissonance, it’s because he’s offering a clear message that just happens to contain a ton: blistering energy, power, pathos, optimism and frustration.

It all springs from experience. When it became clear in the late 1990s that no big label intended to pick him up, Mr. Evans and Mrs. Evans — an occasional vocalist who serves as her husband’s manager, as well as holding down a full-time job — decided to found Imani Records, and put out his music themselves.

“He’s always been an entrepreneur — so he’s always been self-employed,” Mrs. Evans said. But most of his activity is communitarian, and a lot of it centers on mentorship. “His phone just rings all day with people needing advice,” she said, “whether it’s on marriage or music or relationships or parenting.”

This year, the couple restarted Imani Records, which had been dormant for about 10 years. This time the plan is to use the label to promote younger musicians’ work. One of its first new albums will be from Jonathan Michel, a bassist who spent the early years of his professional career in Philadelphia.

He’s one of many young musicians who describe Mr. Evans’s influence as formative. “I saw Orrin asserting himself to make sure that the music is staying alive and still appreciated,” Mr. Michel said, recalling Mr. Evans booking concert series at local restaurants, and leading educational events at Philadelphia’s Kimmel Center.

“You feel it on and off the bandstand,” Mr. Michel added. “He would just invite me over to come eat at his house. It had nothing to do with music, but just with community and family, which has everything to do with music.”

Articles in this series examine jazz musicians who are helping reshape the art form, often beyond the glare of the spotlight.

Orrin

Evans will perform with the Captain Black Big Band at Dizzy’s Club

Coca-Cola on Monday, playing sets at 7:30 and 9:30 p.m.; 212 258-9595, jazz.org/dizzys