SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2022

VOLUME TWELVE NUMBER ONE

SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2022

VOLUME TWELVE NUMBER ONE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

BAIKIDA CARROLL

(September 3-9)

BILLY DRUMMOND

(September 10-16)

BOBBY MCFERRIN

(September 17-23)

ALBERT KING

(September 24-30)

CLORA BRYANT

(October 1-7)

DEAN DIXON

(October 8-14)

DOROTHY DONEGAN

(October 15-21)

BOBBY BLUE BLAND

(October 22-28)

ZENOBIA POWELL PERRY

(October 29-November 4)

CARLOS SIMON

(November 5-11)

VALERIE CAPERS

(November 12-18)

ROLAND HAYES

(November 19-25)

https://www.kmfa.org/pages/570-dean-dixon-a-forgotten-american-conductor

This interview was originally published on June 12, 2015 as Dean Dixon: An Exceptional and Unknown American Conductor Revisited.

Dean Dixon is one of the great, albeit forgotten, conductors of the 20th Century. After graduating from both the Julliard School (with high honors) and Columbia University in the early 1930s, he found his attempts at starting his career in America stifled by his race. Dixon's parents had migrated to Harlem from the Caribbean; he was a Black American.

Initially, in 1931, he formed his own orchestra and choral society. He also guest conducted Arturo Toscanini’s NBC Symphony Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, and later, the orchestras of both Philadelphia and Boston. Despite these prestigious engagements, finding a more permanent position as a music director in his own country proved to be illusive. As a result, Dixon went on a self-imposed exile to Europe where he discovered that the kind of racism that had been part and parcel of his life in the United States was largely not present. He found both the respect and work that he had wanted so much back home.

He became Music Director of Sweden’s Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra (1953-1960) before settling down as the music director of the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra (1961-1974) where he remained for most of the rest of his life. He was also music director of Australia’s Sydney Symphony Orchestra (1964-1967) for a short time. It was during the 1970s that Dixon finally returned to his homeland and found the kind of success and recognition that he had long desired. He made a return appearance to New York where he again guest conducted the New York Philharmonic. He was also invited to conduct concerts with the National Symphony Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, Detroit Symphony, Milwaukee Symphony, Pittsburgh Symphony, St. Louis Symphony, and San Francisco Symphony. Dixon died in Zurich, Switzerland, in 1976 at the age of 61.

Dean Dixon is said to have defined his career in three ways: initially he was “The Black American conductor Dean Dixon,” then he was “the American conductor Dean Dixon,” and, finally he was known simply as “the conductor Dean Dixon.”

Dr. Rufus Jones, Jr. is an Alumni of the University of Texas and has written the first-ever biography of Dean Dixon. He will be in Austin on Saturday, June 20, 2015 (this event has passed) to sign copies of his new book. He spoke with KMFA's Music Director Chris Johnson about this forgotten artist. Listen to their conversation by clicking the play button above.

To see archival videos of Dean Dixon conducting the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra, please click the links below. Please note: the commentary and interviews in the videos and the website are in German. Viel Glück!

Visiting Dean Dixon

Brahms: Tragic Overture

Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dean_Dixon

Dean Dixon

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

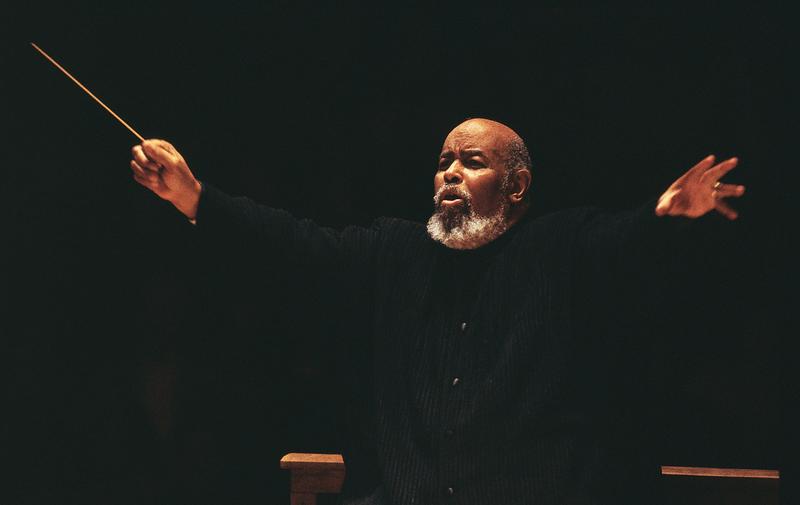

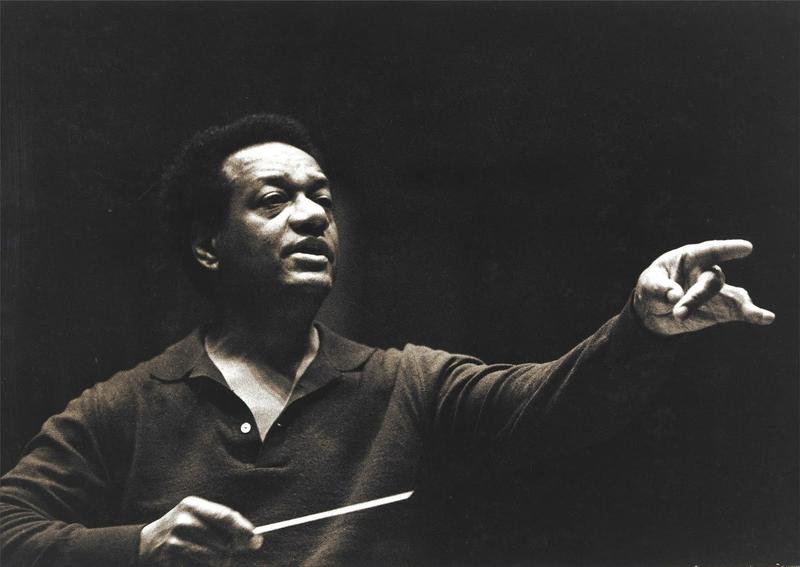

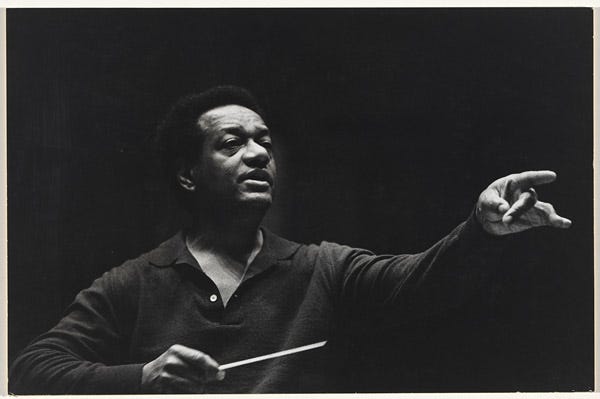

Charles Dean Dixon (January 10, 1915 – November 3, 1976) was an American conductor.

Career

Dixon was born in the upper-Manhattan neighborhood of Harlem in New York City to parents who had earlier migrated from the Caribbean.[1] He studied conducting with Albert Stoessel at the Juilliard School and Columbia University. When early pursuits of conducting engagements were stifled because of racial bias (he was African American), he formed his own orchestra and choral society in 1931. In 1941, he guest-conducted the NBC Symphony Orchestra, and the New York Philharmonic during its summer season. He later guest-conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra and Boston Symphony Orchestra. In 1948 he won the Ditson Conductor's Award.

In 1949, he left the United States for the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, which he directed during its 1950 and 1951 seasons. He was principal conductor of the Gothenburg Symphony in Sweden 1953–60, the Sydney Symphony Orchestra in Australia 1964–67, and the hr-Sinfonieorchester in Frankfurt 1961–74. During his time in Europe, Dixon guest-conducted with the WDR Sinfonieorchester in Cologne and the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks in Munich. He also made several recordings with the Prague Symphony Orchestra in 1968–73 for Bärenreiter, including works of Beethoven, Brahms, Haydn, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Schumann, Wagner, and Weber. For Westminster Records in the 1950s, his recordings included symphonies and incidental music for Rosamunde by Schubert, symphonic poems of Liszt (in London with the Royal Philharmonic), and symphonies of Schumann (in Vienna with the Volksoper Orchester). Dixon also recorded several American works for the American Recording Society in Vienna. Some of his WDR broadcast recordings were issued on Bertelsmann and other labels. Dean Dixon introduced the works of many American composers, such as William Grant Still, to European audiences.

During the 1968 Olympic Games, Dixon conducted the Mexican National Symphony Orchestra.

Dixon returned to the United States for guest-conducting engagements with the New York Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Detroit Symphony, Milwaukee Symphony, Pittsburgh Symphony, St. Louis Symphony, and San Francisco Symphony in the 1970s. He also served as the conductor of the Brooklyn Philharmonic, where he gained fame for his children's concerts. He also conducted most of the major symphony orchestras in Africa, Israel, and South America. Dixon's last appearance in the US was conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra in April 1975.

Dixon was honoured by the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) with the Award of Merit for encouraging the participation of American youth in music. In 1948, Dixon was awarded the Alice M. Ditson award for distinguished service to American music.

Dixon was to tour Australia in the autumn of 1975 but had to cancel most of the tour due to heart problems. He returned to Europe and died in Zug, Switzerland, on November 4, 1976, after suffering a stroke. He was 61 years old.

He once defined the three phases of his career by the descriptions he was given: firstly, he was called "the black American conductor Dean Dixon"; when he started to be offered engagements he was "the American conductor Dean Dixon"; and after he had become fully accepted he was called simply "the conductor Dean Dixon".[2]

Personal life

Dixon was married three times. His first was to Vivian Rivkin, with whom he had a daughter, Diane, in 1948.[3] In the January 28, 1954 edition of Jet, it was announced that he and Rivkin had divorced and he was to marry Finnish Countess and playwright Mary Mandelin. The couple met in 1951 via an introduction when Dixon was directing a concert for the Red Cross in Finland.[4] Dixon and Mandelin were married on January 28, 1954. On July 28 that year, their daughter Nina was born.[5] This marriage also ended in divorce.

In the late 1960s Dixon unsuccessfully tried twice to make contact and re-establish a relationship with Diane, the daughter from his first marriage.[6]

His final marriage was to Ritha Blume in 1973.

See also

Dixon: Maestro Abroad, Stranger at Home

THE exile returns. On Tuesday night Dean Dixon, native New Yorker, will conduct the New York Philharmonic in Central Park — his first appearance on an American podium since he left this country 21 years ago be cause, he says, “I felt like I was on a sinking ship and if I stayed here, I'd drown.”

In 1945, when Dixon was 30, the late Olin Downes, then music critic of The New York Times, called Dixon “a coming man” and added him to a list of “ranking conduc tors” which included such luminous names as Tosca nini, Rodzinski and Stokow ski. But Dixon had a prob lem: he is black. What a novel and nervy idea, espe cially then, for a young Ne gro to aspire to be a symphony conductor!

Now, the man who is ad dressed as “Maestro” in oth er parts of the world, whose face and music are known all over Europe and as far away as Australia — where he was music director of the Sydney Symphony — is a stranger in his own country, virtually unknown to a whole generation of American con certgoers. He has guest‐con ducted as many as 125 con certs a year in Europe, served seven years as music director of the Goteborg Symphony in Sweden, and since 1960 has lived in Ger many where, as music direc tor of the Frankfurt Radio Symphony, he conducts “every day of the year, ex cept for three weeks' vaca tion.”

We met two weeks ago when Dixon paid a four‐day visit to New York prelimi nary to his American en gagements this summer. He will conduct two more Phil harmonic concerts this week —on Thursday night in Pros pect Park, and on Saturday night in Crocheron Park in Queens. His schedule also includes guest ‐ conductor stints with the Pittsburgh Symphony at Temple Univer sity's Ambler Festival, and with the St. Louis Symphony at the Mississippi River Fes tival.

Dean Dixon

1915-1976

Conductor

Dean Dixon was the first major African-American orchestral conductor in American classical music. As a young man he was not only talented but innovative, creating new ensembles that brought classical music closer to the communities it served. His efforts on the podium won critical praise and even the support of the First Lady of the United States. In spite of these successes, he was unable to land a position as music director of an American orchestra, and, like African-American musicians in other genres, he found a more appreciative market for his talent in Europe than he could at home. Dixon often said that early in his career he was known as "the Negro conductor Dean Dixon" (to use the wording of the time), then as "the American conductor Dean Dixon," but he was proudest when he was simply described as "the conductor Dean Dixon."

Charles Dean Dixon was born in New York on January 10, 1915. His father, trained as a lawyer in Jamaica, worked in New York as a hotel porter; his mother was Barbadian. Both parents loved classical music, banned popular music in the house, took their son to concerts at Carnegie Hall, and were dedicated to the idea that their son should become a musician. Dixon learned to read music at age three, before he could read text, and he played violin concerts to imaginary audiences at the suggestion of his mother, who had bought him a violin at a Harlem pawnshop for fifteen dollars. By the time he was nine years old he had made his debut on the radio, and the classmates who tormented him for his musical studies were volunteering to carry his equipment to the studio door.

Dixon's violin teacher, who saw trouble ahead for an African-American violinist in the highly segregated world of classical music, warned him against pursuing a musical career. But Harry Jennison, one of Dixon's teachers at DeWitt Clinton High School, thought enough of his talents to recommend him for admission to the Institute of Musical Art, soon to be renamed the Juilliard School. Dixon enrolled as a violinist but soon switched to the music pedagogy (education) program, taking conducting lessons on the side.

Formed Innovative Music Group

In between classes Dixon was doing things that no other young musician in New York was doing. While still a student at DeWitt Clinton in 1932, he had formed a musical ensemble that at first consisted of only a few of his violin and piano students but eventually grew to include about seventy members. He called it the Dean Dixon Symphony Orchestra, holding rehearsals at the Harlem branch of the YMCA. The orchestra's membership included players from ages twelve to seventy-two, men and women, blacks and whites. The orchestra gave yearly concerts, struggling financially at times but forging onward after a women's club provided an infusion of cash. It lasted until the early 1940s and performed for First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in 1941.

Dixon was graduated from Juilliard in 1936 and continued on as a graduate student, taking conducting classes with the American composer and arranger Albert Stoessel. Dixon also enrolled in a master's program in music pedagogy at Columbia University, receiving a master's degree in 1939. By that time he had made his formal debut as a conductor, leading a concert by a group called the Music Lovers Chamber Orchestra at the Town Hall concert space in 1938. The following year he founded another group oriented toward opening up the institutions of classical music: The New York Chamber Orchestra offered a New Talent prize for musicians who had not made debuts in any of New York's established venues. In 1939 he also conducted a Harlem musical-theater performance of the John Henry legend, starring actor Paul Robeson.

In the early 1940s Dixon's career in conventional venues likewise took big strides forward. Dixon led concerts by the New York City Orchestra in 1940 and the NBC Symphony Orchestra in 1941. In August of 1941 he conducted the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, at an outdoor concert, becoming the first African American to conduct the queen of the city's orchestral ensembles. That was followed by guest conducting slots with the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Boston Symphony Orchestra; Dixon was the first African American to mount the podium with either organization. Concerts with Dixon at the helm received good reviews, and he received two prestigious awards, a Rosenwald Fellowship from 1945 to 1947 and the Alice M. Ditson Award in 1948.

Headed to Europe

This level of professional experience would normally have propelled Dixon to a conducting post with a good-sized American orchestra. Married in 1948 to Vivian Rivkin, a fellow Juilliard student whom he had conducted in concertos for piano and orchestra, Dixon became frustrated with the lack of development in his career—as well as with displays of out-and-out discrimination such as a building manager who refused to admit him to a building for a needed meeting with an orchestra member. After he was invited in 1949 to conduct the French National Radio Symphony Orchestra, Dixon decided to try his luck in Europe. "I felt like I was on a sinking ship and if I stayed here, I'd drown," Dixon said in an interview quoted by D. Antoinette Handy in Black Conductors. "I'd made a start. I had the critics. But for five years after that, nothing happened."

To be sure, going to Europe did not completely insulate Dixon from racism. A Swedish promoter, apparently in all seriousness, suggested in 1952 that Dixon conduct in whiteface makeup, wearing white gloves, but by that time Dixon had already made enough Swedish appearances that he could point in response to his regular and successful experiences conducting in Sweden as a black man. He settled in Sweden and was named conductor of the Göteborg Symphony there, beginning in 1953. Dixon and Rivkin divorced in 1954, and he soon married a Finnish noblewoman, Mary Mandelin. Remaining in Göteborg until 1960, Dixon had guest conducting engagements in virtually all of Europe's major capitals and had offers of new permanent posts in several of them. He introduced European audiences to the music of a long list of American composers, black and white.

At a Glance …

Born Charles Dean Dixon on January 10, 1915, in New York, NY; died November 3, 1976, in Zug, Switzerland; son of Henry Charles and McClara Dixon; married Vivian Rivkin, 1948 (divorced, 1954); married Mary Mandelin (divorced); married Ritha Blume, 1973; children: (first marriage) Nina; (second marriage) Diane. Education: Juilliard School of Music, BM (violin), 1936; studied conducting at Juilliard, 1938-39; Columbia University, MA, 1939.

Career: Founded Dean Dixon Symphony Society (later Dean Dixon Symphony Orchestra), 1932; made debut, conducting League of Music Lovers Chamber Orchestra, 1938; founded New York Chamber Orchestra, 1939; conducted New York Philharmonic, 1941; founded American Youth Orchestra, 1944; conducting engagements in Europe, 1949-52; Göteborg Symphony Orchestra, Sweden, music director, 1953-60; Hessian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Frankfurt, Germany, music director, 1961-70; Sydney Symphony Orchestra, Australia, music director, 1964-67; conducting engagements with New York Philharmonic and other orchestras in United States, early 1970s.

Awards: Julius Rosenwald Fellowship, 1945-47; Alice M. Ditson Award, Columbia University, 1948.

In 1961 Dixon accepted a post as music director of the Hessian Radio Symphony Orchestra in Frankfurt in what was then West Germany, remaining there until 1970. From 1964 to 1967 he also held the music directorship of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra in Australia, taking advantage of the reversal of the seasons in the Southern Hemisphere to work through two concert seasons in the same year. Dixon's second marriage dissolved, and he married a German woman, Ritha Blume. Each of his first two marriages produced one daughter (Nina and Diane, respectively). Dixon made about twenty recordings for Desto, Westminster, and other small labels; many of them are prized by record collectors.

Returned to United States

A major point of pride in Dixon's later life was his return to the United States in 1970, by which time—although quite familiar to European classical audiences—he was virtually unknown in his home country and had not appeared there for twenty-one years. Dixon conducted the New York Philharmonic in three outdoor concerts, appeared in 1970 with the Pittsburgh and St. Louis symphonies, and then embarked on a nationwide tour, sponsored by Schlitz beer, that included appearances with eight orchestras, including the Chicago and Detroit symphonies and the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, D.C. "It was not because I was suddenly a better conductor," Dixon observed in an interview quoted by Handy, "but because black was suddenly beautiful. And what could be more beautiful than a black conductor?" Although Dixon recalled that he took some criticism from younger African-American activists who believed that he had "opted out," he felt that his example was useful to young black musicians. "By getting away I have helped those at home," he said in the same interview. "I have shown what can be done."

Dixon returned to his home, by then in Switzerland, and continued to conduct in Europe. In 1975 he began a tour of twenty-four concerts in Australia. At the beginning of the tour Dixon discussed various aspects of his life with Australian journalists; it emerged that he and his German wife were vegetarians, environmentalists, and fitness buffs. Dixon also said (according to Handy) that working on amateur inventions was "essential to his sanity away from the conductor's podium"; his inventions included an improved bathroom cistern and a transparent piano top. Despite his healthful ways, however, his Australian tour was cut short by heart problems. He underwent open-heart surgery in Switzerland in December of 1975 and returned to work, but he died in Zug, Switzerland, on November 3, 1976.

Selected discography

Dvorak: Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104, Westminster, 1952.

Howard Swanson: Short Symphony, American Recording Society, 1952(?).

(With Geza Anda) Bartók: Piano Concerto No. 2, RAI, 1961.

The Black Composer in America, Desto, 1971(?).

Christian Ferras Portrait, Originals, 1995.

Ruggiero Ricci Plays Stravinsky, Shostakovich, Respighi, One-Eleven, 1997.

Liszt: Orchestral Music, Westminster.

(With Vivian Rifkin and Orchestra of the Vienna State Opera Orchestra) MacDowell: Piano Concertos # 1 & 2, Westminster.

(With American Recording Society Orchestra) Piston: Symphony No. 2, American Recording Society.

About twenty LPs, plus other performances, preserved in European radio archives.

Sources

Books

Handy, D. Antoinette, Black Conductors, Scarecrow, 1995.

Periodicals

American Visions, February-March 1993, p. 44.

Black Perspective in Music, Autumn 1976, p. 345.

Time, April 21, 1941.

Online

"Recordings of Dean Dixon," http://www.h4.dion.ne.jp/~hugo.z/DeanDixon/DixonRecordings.html (accessed March 17, 2008).

Contemporary Black Biography

https://www.wqxr.org/story/americas-lost-generation-black-conductors/

The 1970s are hardly ancient history, but the decade seems like a distant world that had African American symphony and opera conductors in a few highly visible positions. Though not exactly common, Black conductors were a definite presence — long-emerging careers blossomed and young firebrands soared out of left field, each in ways that intersected around that time.

This lost generation of African American conductors led major concerts by Arturo Toscanini’s NBC Symphony, gave the Philadelphia Orchestra premiere of the Shostakovich Symphony No. 8, and led the Metropolitan Opera’s celebrated rehabilitation of Meyerbeer’s Le Prophète. Most of them were robbed of that over-60 elder-statesman period when the world was likely to more widely celebrate their accumulation of artistic wisdom. But there’s ample proof that Dean Dixon (1915–76) and Calvin Simmons (1950–82) had many great moments well before then. They can be counted among the finest of any generation.

Their contemporaries include Henry Lewis (1932–96), who conducted 143 performances at the Met between 1972 and 1977 (including Le Prophète). James DePreist (1936–2013) built the Oregon Symphony over 20-plus years, and received the National Medal of Arts from George W. Bush. Paul Freeman (1936–2015) extensively recorded under-represented African American composers for Sony Classical, and went on to hold number of appointments, most notably the Victoria (BC) Symphony from 1979 to 1988. Isaiah Jackson (b. 1945) brought the massive Mahler Symphony No. 8 to Dayton, Ohio, and extensively conducted ballet at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden.

What happened to these particular musicians? You name it — including freaky strokes of bad luck. When in Prague recording Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7, Dixon was forced to make a hasty departure when the country was invaded by the Soviet Union. When he was in his late 20s, DePreist contracted polio while on a State Department–sponsored visit to Bangkok and was paralyzed in both legs. And during a brief, pre-dinner canoe trip while vacationing in the Adirondack Mountains, Simmons capsized and drowned at age 32.

A Maestro Abroad

Harlem-born Dixon was the first, perhaps the greatest so far — and the one most overtly blocked by racism: In a profession that’s about authority, some musicians rebelled against the very idea of a Black man telling them what to do. After early successes in 1940s America that had little follow-up, Dixon decamped to Europe where he more or less worked himself to death, arriving back in the U.S. in weakened condition in his last six years. Musicians still knew they were in the company of a towering talent, but at least one also observed that he had a colostomy bag.

His career has interesting parallels the Jewish-Hungarian Georg Solti, whose beginnings in post-war Germany had him facing hostile, anti-Semitic musicians, forcing him to make his career in London and Chicago while also building a recording profile with the Vienna Philharmonic. Dixon faced similar resistance in America; the Rufus Jones Jr. biography Dean Dixon: Negro at Home, Maestro Abroad (Rowman & Littlefield, 2015) recalls one story: Upon asking for a more “agitato” reading of the violin solo in Don Juan, Dixon was angrily accused of personally insulting the associate concertmaster of the NBC Summer Symphony. Reactions among other musicians were predominately sympathetic to Dixon, who had his own way of handling it. “Strauss has written agitato and I would like to have a bit more agigato,” was Dixon’s measured reply. Though both Solti and Dixon shared an almost defiantly vigorous approach musical interpretations of Beethoven, Bruckner, and Mahler, they were temperamental opposites: Solti shouted, Dixon did not.

And it was Dixon, much more than Solti, who thrived in Germany with guest-conducting gigs and recordings in Vienna during that post-war period when doors were open to conductors with no Nazis in their past. Early European successes landed him Sweden’s Gothenburg Symphony from 1953 to 1960, but he perhaps did his best work with the Frankfurt Radio Symphony from 1961 to 1974. He also pursued one particular musical passion: exploring the juxtaposition of Henze and Bruckner.

Two things delayed guest engagements in the U.S. until 1970: Dixon was too busy elsewhere, and, in New York, he was facing an alimony / child support lawsuit from his first wife, Vivian Rivkin. In modern currency, his child support payments were more than $2,000 a month, and the price of settling the 1969 suit was $91,000. Remember: at the time, symphony orchestra conductors weren’t paid then anything close to what they are now — travel and hotel expenses easily outstripped a guest-conducting fee. Still, after Rivkin died of cancer, his daughter Diane resisted his reconciliation attempts. Subsequently, Dixon had at least five years of successful U.S. engagements. Something more substantial was bound to come his way in time, but he suffered from an array of health issues, and eventually died of a stroke at age 61.

Dixon made plenty of recordings, but try finding them. The labels he frequented — Vox and Westminster — have been bought and sold so many times that it’s hard to know who owns them and if they know what they have. Some of his Prague Symphony Orchestra recordings turn up on YouTube, but I have never physically seen them in this country. At least the Audite label has issued Dixon’s excellent Beethoven Symphony No. 9, though mainly on the strength of the final movement’s tenor soloist, Fritz Wunderlich. Indeed, the final-movement vocalists are extremely fine, and would have to be in order to navigate Dixon’s spirited tempos. This is one of the better Beethoven Ninths out there, but were it not for Wunderlich’s devoted posthumous following, the recording would likely be sitting, unheard, in a German radio archive.

Doing What It Takes, In Spite of the Hurdles

The two pillars of any conducting career are orchestra building and recordings. But reading the politics of any recording company almost requires a degree in Kremlinology. It now seems astounding that Paul Freeman’s 1970s nine-disc survey of Black symphonic composers from the 18th to the 20th century was cultivated by Sony Classical (then Columbia). Freeman also recorded plenty of standard repertoire with the pianist Derek Han.

James DePreist recorded all of the Shostakovich symphonies with the Helsinki Philharmonic on the Ondine label, though most of his 60 recordings were with the Oregon Symphony Orchestra, which could play a Rite of Spring with the best of them. While Dixon’s music-making regularly pounded on heaven's door, DePreist drew his power from inner tension, rhythmic vitality, and, in new-music premieres, impeccable preparation — qualities that register well on recordings.

“He always seemed very musical, knew his scores, had a clear baton technique, and the musicians of the orchestra really respected him. And that, perhaps, is the best barometer there is,” said Pulitzer Prize–winning composer Jennifer Higdon, whose 1995 piece Shine, a major career stepping-stone, was premiered by DePreist. “He had a commanding presence on the podium and on the stage. I never heard anyone complain about him at all.” And that, she says, is unusual.

DePreist was also the most successful in orchestra building, turning a low-profile ensemble into a high-profile one during his 1980–2003 Oregon Symphony tenure. Similarly, Lewis built the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra, from 1968 to 1976, into an organization that no doubt drew many New York listeners with niche programming such as the loved-but-seldom-heard Hans Pfitzner opera Palestrina performed in excerpts with star tenor Nicolai Gedda. Amid any number of other orchestral appointments, Freeman founded and led the Chicago Sinfonietta in 1987, and it’s still alive some 15 years after his death.

Isaiah Jackson headed the orchestras in Dayton as well as Flint, Michigan, only to experience hearing loss starting in his 50s. His career suggests another kind of trap: The statuesque Jackson lost time when associate conductor of the Rochester (NY) Philharmonic in its late-1970s / early-1980s golden age: He was the orchestra’s public face, made the organization seem like the coolest place to be, and showed every sign of enjoying being second in command. But that number-two position comes with a lot of quickly-assembled lighter-weight concerts, when he was far better with more ambitious and better-rehearsed programs featuring, say, the infrequently mounted complete ballet version of Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloe.

Prodigious on the Podium

Calvin Simmons might’ve had a similar fate when on staff at England’s congenial Glyndebourne Festival — according to Rinna Evelyn Wolfe’s 1994 biography The Calvin Simmons Story or Don’t Call Me Maestro (Muse Wood Press) — but was kicked out of the nest, and from there, seemed to defy all gravity. Born in San Francisco, he had emerged from the ranks of the San Francisco Opera, and, in 1978, had three major breakthroughs: He was appointed to the Oakland Symphony and the Ojai Festival, and made his Metropolitan Opera debut. He was age 28, and a classic case of a conductor who innately knew all the things that can’t be taught. Artistry came so naturally to him that teachers told him to take matters a bit more seriously, no doubt because he was having great fun — and sharing it with his delightfully unbuttoned humor.

Once, when asking the Philadelphia Orchestra for a typical hairpin crescendo, he confided, “You know … those hairpins … I don’t use them anymore.” A number of his masterclasses survive, and they’re as insightful as they are buoyant. Broadcast performance recordings survive — not officially published, but passed around by collectors. Has any opera cast seemed to have so much fun as his Hansel and Gretel debut run at the Met? Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk in the 1981 San Francisco Opera season, starring Anja Silja, is fearlessly explosive, with razor-sharp precision. His analytical powers were also evident in panel discussions where he argued against the conventional wisdom that then surrounded the opera.

He was irrepressible, which could be one explanation why the six-foot-plus Simmons made the fatal split-second decision to stand up in a canoe on that chilly 1982 evening in the Adirondack Mountains, when someone on shore was taking his picture. Simmons had dressed in layers — not including a life jacket. But then, he was not the type to take precautions. Perhaps none of them were.

Conducting is a profession that’s taken up either out of unquenchable inner need (when artists can’t express themselves any other way) or absolute necessity (composers who need to double as performers to ensure their works are properly heard). Even when all doors are open to an emerging conductor, the climb to the top is extraordinarily steep. Has it grown steeper? Explaining the comparative lack of African American conductors today is beyond the scope of this article. But I bet that the 21st century classical world would look very different had these artists lived longer and inspired the world with the possibilities that they represented.

https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,772721,00.html

TIME

Music: Negro Conductor

Follow @TIME

A broad-faced, close-cropped, 26-year-old Harlem musician named Dean Dixon was well on his way last week to doing what no Negro has ever done—conduct a first-rank symphony orchestra. Musician Dixon had already waved a crisp, confident baton over the New York City Symphony (see above), the National Youth Administration radio orchestra, and an amateur symphony of his own in Harlem. At a Town Hall recital, Conductor Dixon made more news. He directed a 38-piece white outfit which he had founded—the New York Chamber Orchestra—in concertos with a debutante pianist, Vivian Rivkin.

Critics gave them all a hand, agreed that Dean Dixon had scored a point. For Town Hall debuts, ordinarily a dime a dozen sound like bigtime with an orchestra on the stage. Dean Dixon's can be hired for $400 to $1,000, depending on the number of players required—union scale for one rehearsal and the performance.

Dean Dixon read music when he was three and a half, gave concerts to imaginary audiences (his mother's idea) when he was five. The Juilliard Institute took him in as a violinist, later spotted conducting possibilities in him. Musician Dixon took a master's degree at the Juilliard Graduate School, is now working at Columbia on a Ph.D. thesis: "The Justification for Editing Classical Scores." In Harlem, between times, he founded Dean Dixon 's Symphony Orchestra, which now has amateur but well-drilled players of every race, aged 12 to 72. The orchestra rehearses weekly, gives one concert a year; next month there will be a special request performance for Mrs. Roosevelt. Conductor Dixon got up his chamber orchestra three years ago. Its' expert players— from the Philharmonic, NBC and other symphonies — are his friends, play together for fun, get union wages for playing in public.

Busy Dean Dixon also works with a choral group, gives three free weekly music appreciation courses to both Negro and white children. These he teaches by inventing melodramatic stories, substituting musical notes for letters and words. "I try to use as much Superman stuff as possible," says Dean Dixon.

http://www.brooklyn.cuny.edu/web/academics/centers/hitchcock/publications/amr/v43-1/oja.php

Academics

Centers and Institutes

H. Wiley Hitchcock Institute for American Music

Publications

American Music Review

American Music Review, Vol. XLIII, No. 1, Fall 2013

Everett Lee and the Racial Politics of Orchestral Conducting

American Music Review

Vol. XLIII, No. 1, Fall 2013

Everett Lee and the Racial Politics of Orchestral Conducting

By Carol J. Oja, Harvard University

While researching a book about the Broadway musical On the Town, I quickly realized that the show's initial production in 1944 was remarkable for its progressive deployment of a mixed-race cast.1 On the Town marked the Broadway debut of Leonard Bernstein, Betty Comden, Adolph Green, and Jerome Robbins. Its star was the Japanese American dancer Sono Osato, and its cast included six African Americans out of a total of fifty-four. Today, those numbers would appear as tokenism. Within the context of World War II, however, with a contentiously segregated military, detainment of Japanese Americans as "alien enemies," and racial stereotypes of the minstrel show fully in practice, On the Town aimed to challenge the status quo. Black and white males in military uniforms stood side-by-side on stage, modeling a desegregated military, and black men held hands with white women in scenes of inter-racial dancing. The show's intentional desegregation made a statement.

An equally important racial landmark occurred nine months into the run of On the Town, when during the week of 9 September 1945 Everett Lee, an African American conductor, ascended to the podium of the show's otherwise all-white pit orchestra. Previously, Lee had been the orchestra's concertmaster. In an era of Jim Crow segregation in performance, Lee's appointment was downright remarkable, and it has been followed by an equally exceptional career. His first wife Sylvia Olden Lee (ca. 1918-2004) emerged professionally at the same time as her husband, and their development as musicians was deeply intertwined. She ultimately became a celebrated accompanist and vocal coach, working with African American divas such as Jessye Norman and Kathleen Battle.

While considerable attention has been directed to the racial desegregation of jazz, far less scholarship has focused on how the process unfolded in New York City's classical-music industry and in musical theater. Key moments stand out—such as Todd Duncan's debut with the New York City Opera in 1945 or Marian Anderson's debut with the Metropolitan Opera in 1955, which was the first time that the famed company featured an African American singer on stage. The Met took this step at a shockingly late date. Among black conductors struggling with racial limitations, Dean Dixon was best known among Lee's contemporaries. Both conductors faced a climate of "orchestrated discrimination," as the Civil Rights leader Vernon E. Jordan, Jr. once rued the stubbornly slow desegregation of American symphonies, and they devised resourceful strategies to keep working.2

courier-journal.com">

Everett Lee with Reverend J. C. Olden, Civil Rights leader and father of Lee’s first wife, Sylvia Olden Lee, Courtesy of The Courier-Journal and courier-journal.com

Here, I explore the central outline of Everett Lee's career, which offers an inside view of racial segregation's impact on gifted black performers. I was fortunate enough to have two extended telephone interviews with Lee at his home in Norrköping, Sweden, where he continues to thrive in his nineties. Added to that, the digitization of historically black newspapers has opened access to valuable information about the world in which he was launched.

Everett Lee (b. 1916) grew up in a middle-class family dedicated to his development as a musician. The wild card was race. Born in Wheeling, West Virginia, Lee moved with his parents to Cleveland in 1927 as part of the Great Migration.3 His father, Everett Lee, Sr., climbed up through the civil service, achieving leadership roles in largely white contexts and providing a model for his talented son. During WWII, the elder Lee became Executive Secretary of Ration Board 11 in Cleveland and was credited with inaugurating "a system of making the rationing program fit the individual, [which] stamped out all discrimination involving race or riches."4 As a teenager Everett had a job at a local hotel as an elevator operator and busboy. There, he met Artur Rodzinski, conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra. "And Rodzinski," Lee recalled in one of our interviews, "somebody told him that this kid is a very promising musician, and he just asked me ‘who are you,' and I told him, and he said, ‘well, come to my concerts.' Every Saturday I could go to the Cleveland Orchestra concerts."5 Rodzinski became central to Lee's development. "My early conducting aspirations were nurtured by him," Lee told a reporter from the Pittsburgh Courier in 1948. "Rodzinski helped me in many ways—he would go over scores with me and give me pointers."6 During this period, Lee studied violin at the Cleveland Institute of Music, a historically white conservatory, where he was awarded a Ranney Scholarship and his primary teacher was the famed violin virtuoso Joseph Fuchs.7

Lee enlisted in the military in June of 1943, becoming an "aviation cadet at the Tuskegee Army Air Field."8 He was released early because of an injury and recruited for the pit orchestra of the all-black show Carmen Jones, which included a new libretto by Oscar Hammerstein II and a new arrangement of Bizet's score by Robert Russell Bennett. "To the right of renowned conductor, Joseph Littau," reported the New York Amsterdam Newsin late January 1944, nearly two months into the show's run, "sits the concertmeister, in this particular instance a young man of comely appearance, with a face that brightens and shines when you talk about music, and probably the only Negro ever to have held that title."9 The rest of the orchestra was white, with the exception of the black jazz drummer William "Cozy" Cole, who also appeared on stage.10 Very quickly, Lee's talent was recognized, and he substituted as a conductor of Carmen Jones even before his debut with On the Town; he also had a brief conducting opportunity with a revival of Porgy and Bess in the spring of 1944.11

Lee's appointment as music director of On the Town put him fully in charge of a Broadway pit orchestra for an extended period. In an interview with the Daily Worker in October 1945, Lee praised On the Town, saying it "has done some splendid pioneering work on Broadway." Beth McHenry, reporter for the Worker, expounded on Lee's statement:

What he referred to particularly, he said, was the integration of Negro artists with others in the cast of On the Town, not in the usual ‘specialty number' category but in the regular assembly of dancers. Mr. Lee attributes this to the honest and democratic ideas and efforts of the musical's authors—Betty Comden and Adolph Green and to the cooperative efforts of the whole cast. He himself was urged to come to this show by Leonard Bernstein, the composer.12

In the mid-1940s, even as On the Town was still in its run, Lee was also on the rise within top-flight, pre-dominantly white institutions of classical music. He was one of the soloists in Vivaldi's Concerto for Four Violins, performed in late February 1945 by the New York City Symphony, conducted by Leopold Stokowski. Another violinist that evening was the renowned Roman Totenberg, which signals the level of Lee's virtuosity.13 As segregation was challenged, interracial networks began to form. In Lee's case, Rodzinski probably recommended him to Stokowski. Based in part in their shared Polish heritage, Stokowski had been responsible for bringing Rodzinski to the United States as his assistant in 1925. Furthermore, when Rodzinski left Ohio in 1943 to become conductor of the New York Philharmonic, he hired Bernstein as his assistant conductor.14

Bernstein and Lee continued to work together after On the Town closed. In the summer of 1946, both Everett and Sylvia Lee attended Tanglewood, the summer home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in the Berkshire Mountains. "Lenny talked to Koussevitzky and I got the Koussevitzky scholarship, and I was up at Tanglewood," Lee recalls, "and boy that was a wonderful experience."15 There Lee not only studied conducting with Koussevitzky, but also worked with Boris Goldovsky in the opera department.16 Just as importantly, he observed Bernstein prepare the American premiere of Peter Grimes by Benjamin Britten. The summer at Tanglewood was equally valuable for Sylvia Lee, who served as technical assistant to Goldovsky, which meant she helped coach singers and apprenticed with one of the great opera directors of the day.17 From late September through October 1946—right after the Tanglewood experience—Everett Lee played first violin for the New York City Symphony, which Bernstein continued to conduct (through the 1947-48 season).18 But his engagement with the orchestra was limited. "I wish I could be playing with you," Lee wrote to Bernstein, "but . . . it would be impossible for you to release me when my promised show comes up. Of course you understand how important that is with jobs so scarce!"19 At some point in the late 1940s, Lee was also a staff violinist with the CBS Orchestra.

Lee faced formidable obstacles. In an interview decades later with the New York Amsterdam News, he recalled asking Rodzinski for an audition with the New York Philharmonic. This occurred at some point between 1943 and 1947, when Rodzinski was the orchestra's music director. "He was afraid to encourage me to try because he didn't want me to be hurt," Lee told the Amsterdam News. "He knew that I would not be accepted into the orchestra. This was one of the factors which helped me decide to try conducting."20 This episode offers a revealing glimpse of Lee's resilience: when told that an opportunity was closed to him, he turned around and aimed for a higher rung on the ladder.

Taking matters into his own hands, Lee formed the Cosmopolitan Symphony Society, an interracial orchestra, in New York in 1947. Other outsider conductors have implemented the same strategy, including Dean Dixon in the 1930s and Marin Alsop in the 1980s. Lee's Cosmopolitan Symphony included "Americans of Chinese, Russian, Jewish, Negro, Italian and Slavic origin," as well as several female players.21 Women were also systematically excluded from American orchestras during this period. The resounding success of the Cosmopolitan Symphony demonstrated not only Lee's musical gifts but also his organizational skill and flair for attracting an audience. The orchestra had a civil rights mission at its core, as the Amsterdam News reported:

The working together of various races for mutual sympathy and understanding has been successfully accomplished in churches, choral groups and other endeavors, and this effort to combine highly competent musicians in a grand orchestral ensemble as a cultural venture deserves the support and good will of every faithful adherent to the principles of our democracy.22

"My own group is coming along fairly well, but of course there is no money in it as yet," Lee wrote to Bernstein. "I hope to make it grow into something good however, and it may be the beginning of breaking down a lot of foolish barriers."23 Musicians' Local 802 assisted the Cosmopolitan Symphony by waiving its rates for rehearsals. Lee had to pay union scale for performances, however.24 The orchestra rehearsed in the basement of Grace Congregational Church in Harlem through the aegis of its minister, Dr. Herbert King. Sylvia Olden Lee was organist at the same church, and her father James Clarence Olden was a Congregational minister in Washington, D.C. Everett recalls that James Olden provided a crucial link between Grace Congregational and the Cosmopolitan Symphony.25

The first concert of the Cosmopolitan Symphony Society took place at the Great Hall of City College in Harlem on 9 November 1947. "A capacity audience" that reacted with "enthusiasm and unstinted applause" to this "cultural effort which has such historic implications," reported the Amsterdam News.26 The concert blended standard European symphonic literature (Beethoven's First Symphony) with an aria and recitative fromLa Traviata performed by the black soprano June McMechen. Five Mosaics by the African American composer Ulysses Kay received its premiere, and Sylvia Olden Lee was the featured soloist for Schumann's Piano Concerto in A Minor (first movement).

The Cosmopolitan Orchestra gave a notable concert on May 21, 1948 at Town Hall, a midtown concert facility noted for its egalitarian policies. The New York Times covered the event, which was unusual for the time for any concert of classical music that involved black musicians, praising Lee as a conductor "who possesses decided talent" and the orchestra as a "gifted group."27 Like Lee's first concert, this one blended European classics with a new work by Kay, Brief Elegy, and included black soloists. Concerts by the organization continued at Harlem churches, and another at the Great Hall of City College in 1952 yielded the orchestra's "finest performance," according to Nora Holt, classical music critic for the Amsterdam News. Described as "thrilling" by Holt, that event played to a "sold-out audience" of 2,100 "uptown music lovers."28 During this period, Lee conducted elsewhere as well, including for the Boston Pops in July 1949, albeit as part of its "traditional Colored American Night."29

Navigating a career in the United States "was a struggle," Lee told me in an interview. He recalled a sobering conversation with the famed lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II:

First as a violinist, that's how I first made my name, made a splash. Made concertmaster of two orchestras, and then getting on staff at CBS. . . .And then I began to conduct, and naturally my name spread around like fire. And I remember when. . . Oscar Hammerstein had a big party, and I don't know whether it was at his home or Richard Rodgers's home. And so everybody in the musical world was there, both from the Broadway world and classical world. And so Oscar said, ‘Everett, come in here, I want to talk to you.' He said, ‘Everett, we've got to explain something to you.' So we went into another room, and yeah it was at Rodgers's home – apartment. He said, ‘You know, Dick and I.' Dick, you know, Richard. ‘Dick and I have talked about you, and you know we have so many big shows going. We thought to bring you in on one, but you would be the boss. We were going to, we had talked about putting you on the road, sending you on the road with one of our big shows. But you're too well known. If a colored boy is the conductor, and we go into the South, we would lose, we would not be—they would deny our coming in. But I want you to know, Everett, that we had thought about you, and we had planned one of our big shows.30

In other words, Lee had achieved enough success so that his name would be recognized in Jim Crow territory, and according to the warped racial logic of the day that meant he was too accomplished and well-known to be hired.

More barriers appeared. Based on the success of his Town Hall concerts with the Cosmopolitan Symphony, Lee approached Arthur Judson, the foremost concert manager of the day, hoping to get work as a guest conductor with established orchestras. Judson managed the New York Philharmonic and the Philadelphia Orchestra, as well as other major American concert organizations and virtuosi. Sylvia Lee recalled what Everett told her about the interview: "Judson turned and said, ‘Oh, come in, young man. I'm reading these reviews. They are out of this world. You really have something. But I might as well tell you, right now, I don't believe in Negro symphony conductors. . . . No, you may play solo with our symphonies, all over this country. You can dance with them, sing with them. But a Negro, standing in front of a white symphony group? No. I'm sorry."31 Everett reported to Sylvia that he was "stupefied," adding that Judson concluded, "I'm sorry, young man. I told the same thing to Dean Dixon." Everett responded by saying, "Yes, Dean Dixon had to leave his country to be a man and a musician." Judson then suggested that Everett consider going abroad.

In 1952, Everett and Sylvia Lee did just that, receiving Fulbright fellowships to study in France, Germany, and Italy, and their departure marked the first stage in Everett's career-in-exile. This strategy was chosen by many African-American performers after World War II. When the Lee's left the country, the Cosmopolitan Symphony came to an end.32 The couple returned to the United States one year later in what turned out to be a temporary step. In 1953, Everett was guest conductor with the Louisville Orchestra, in what the New York Times claimed to be "one of the first concerts in which a Negro has led an orchestra of white musicians."33 The concert was not part of the orchestra's regular season but rather was billed as a "special" event, outside of the subscription series.34

Everett Lee conducting the Louisville Orchestra in 1953 as published in Jet, 1 October 1953

Other major breakthroughs took place for both Everett and Sylvia Lee in the early 1950s. In 1953, Sylvia was hired by the Metropolitan Opera's Kathryn Turney Long Department, and she was credited as the first African American on the Met's staff.35 As a result, Sylvia was in residence when Marian Anderson made her Metropolitan Opera debut. Both she and Everett developed a close working relationship with Max Rudolph, a conductor and central figure in the Met's management. In 1955, another major development occurred when Everett conducted La Traviata at the New York City Opera, becoming "the first Negro conductor to be engaged by the company," according to the New York Times.36 He went on to conduct La Bohème with City Opera the following fall.37 In 1956, he reportedly signed a contract with the National Artists Corporation, one of the most influential management companies for American musicians.38

Yet Lee still became an expatriate. Beginning in 1957, he and Sylvia moved to Munich, where he conducted the opera and founded the Amerika Haus Orchestra.39 That same year, Leonard Bernstein was appointed conductor of the New York Philharmonic, yielding a sharp contrast in the trajectory of their careers. In 1963 Lee became music director of the symphony orchestra in Norrköping, Sweden, southwest of Stockholm.40 Dean Dixon had conducted the Gothenburg Symphony in Sweden from 1953 to 1960, and Lee held his own Swedish post for over a decade, finding Sweden to be a place where he could make music without racial complications.

In 1965, Symphony of the New World was formed in New York City, and Lee became a central figure. An interracial orchestra, Symphony of the New World essentially picked up where the Cosmopolitan Symphony had left off. Out of eighty-eight "top musicians," it included thirty-six African Americans and thirty women.41 Initially, Everett Lee, Henry Lewis, and James DePriest were the main conductors.42 DePriest was the nephew of Marian Anderson, and Lewis was then married to mezzo-soprano Marilyn Horne, with whom he collaborated professionally. Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson also became one of the organization's principal conductors. When Lee returned to the U.S. to conduct the new orchestra in 1966, the New York Times reported that the engagement marked "his first appearances in this country since he conducted for the New York City Opera in 1956."43 Once again, a Harlem church provided an anchor for the orchestra—this time, the Metropolitan Community Church.

Lee made his debut with the New York Philharmonic as a guest conductor on 15 January 1976. He was then sixty years old, and the concert took place on the birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr. Similar to programming of the Cosmopolitan Symphony, the concert included Sibelius's Violin Concerto, Rachmaninoff's Third Symphony, and Kosbro by the African American composer David Baker. Harold Schonberg of the New York Times gave Lee a positive if somewhat patronizing review, stating that he "conducted a fine concert" and "made good music without bending over backward to impress." While "a Philharmonic debut can be heady stuff," Schonberg concluded sardonically, "Mr. Lee . . . refus[ed] to be drawn into the temptation to give the audience cheap thrills."44 This breakthrough for Lee occurred during the U.S. Bicentennial, when awareness of supporting African-American performers and composers was at an all-time high.45 Bernstein was then the orchestra's Laureate Conductor.

In the ensuing years, Lee has continued to have a successful career working with orchestras around the world. During the 1940s and 1950s, when he built his reputation as a conductor and stepped onto major stages in Europe, American conductors were absent from podiums in the United States, no matter what their race. For a conductor of color, however, barriers defined the game. No prominent African American conductor of classical music from the generation born before 1925—not Dean Dixon, not Everett Lee—was permitted a sustained position on the playing field. Yet Lee resiliently created opportunities for himself, essentially establishing his own league.

Notes 1 This article is drawn from my forthcoming book, Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art in a Time of War (Oxford University Press, to be published in 2014).

2 Vernon E. Jordan, Jr., "Orchestrated Discrimination," New Pittsburgh Courier, 7 December 1974.

3 Much of the biographical information in this paragraph comes from Joseph M. Goldwasser, "Where There's A Will, There's Everett Lee and Family," Cleveland Call and Post, 10 November 1945.

4 Ibid.

5 Everett Lee, interview with the author, 25 March 2009.

6 "Everett Lee to Conduct Symphony: Town Hall Concert on May 21 Awaited," Pittsburgh Courier, 8 May 1948.

7 Lee's scholarship is mentioned in many newspaper articles, including "Give Reception for Newlyweds,"Chicago Defender, 26 February 1944.

8 "Pilot's Wings are Sought by Violinist," Chicago Defender, 19 June 1943.

9 Nora Holt, "Everett Lee, First Negro Concert Meister, Soloist in ‘Carmen Jones,'" New York Amsterdam News, 29 January 1944.

10 Lee interview, 25 March 2009.

11 Regarding Lee and Carmen Jones: "Violinist in ‘Carmen' Hits for Another," Chicago Defender, 13 May 1944; and "Everett Lee Youngest Conductor on Broadway," Pittsburgh Courier, 3 June 1944. Lee's work withCarmen Jones is discussed in Annegret Fauser, "‘Dixie Carmen': War, Race, and Identity in Oscar Hammerstein's Carmen Jones (1943)," Journal of the Society for American Music 4/2 (2010): 164. Regarding Lee and Porgy: Lee was reported as conducting the orchestra of Porgy "last week," in Constance Curtis, "New Yorker's Album," New York Amsterdam News, 8 April 1944.

12 Beth McHenry, "Everett Lee, First Negro Musician To Lead Orchestra in Bway Play," Daily Worker, 13 October 1945.

13 "Stokowski Offers Concert Novelties," New York Times, 27 February 1945.

14 The New York Times stated that Bernstein heard Lee conducting Carmen Jones "and engaged him to conduct his musical, ‘On the Town'" (Ross Parmenter, "The World of Music: Season's Start," New York Times, 31 August 1947). Also, an article in the Pittsburgh Courier (8 May 1948), "Everett Lee to Conduct Symphony: Town Hall Concert on May 21 Awaited," credited Rodzinski with having "helped him [Lee] make useful contacts in the musical world."

15 Lee interview, 25 March 2009.

16 Wallace McClain Cheatham and Sylvia Lee, "Lady Sylvia Speaks," Black Music Research Journal 16/1 (Spring 1996): 201-202. This interview was also published in Dialogues on Opera and the African-American Experience, ed. Wallace McClain Cheatham (The Scarecrow Press, 1997), 42-67. That same volume includes a terrific interview with Everett Lee (pp. 24-42).

17 "Violinist, Wife in Joint Recital," Chicago Defender, 22 June 1946.

18 Lee is listed as first violin in programs from the week of 30 September through the week of 28 October 1946 (The Program-Magazine of the New York City Center 4/4-4/9, Bernstein Collection, Library of Congress, Box 335/Folder 3).

19 Lee, letter to Bernstein (perhaps in 1947), Bernstein Collection, Box 35/Folder 15.

20 Raoul Abdul, "Reading the Score: Conversation with Everett Lee," New York Amsterdam News, 8 October 1977.

21 Regarding races and nationalities represented: "Everett Lee to Present Mixed Symphony Group," New York Amsterdam News, 25 October 1947. Regarding women: N.S. [Noel Straus], "Symphony Group in Formal Debut," New York Times, 22 May 1948.

22 "Everett Lee to Present Mixed Symphony Group."

23 Lee, letter to Bernstein, undated; Bernstein Collection, Box 35/ Folder 15.

24 The "cooperation" of Local 802 is noted in: "Everett Lee Organizes Interracial Symphony," New York Amsterdam News, 30 August 1947. Also Lee explained his arrangement with the union in an interview with me: "I asked the musician's union if I could just get a bunch of musicians together. The union gave me permission to rehearse these people. And of course with stipulations, there was no recordings, and if I were to have a concert, then I would have to, naturally they would have to be paid (28 March 2009).

25 Everett Lee, interview with the author, 28 March 2009.

26 "Cosmopolitan First Concert Wins Acclaim," New York Amsterdam News, 15 November, 1947.

27 N.S. [Noel Straus], "Symphony Group in Formal Debut."

28 Nora Holt, "Cosmopolitan Symphony in its Finest Performance: Sold-Out Audience of 2,100 Acclaims Lee's Production," New York Amsterdam News, 8 March 1952.

29 "Guest Conductor for Boston Concert," Chicago Defender, 2 July 1949.

30 Lee interview, 28 March 2009.

31 Everett Lee, as paraphrased by Sylvia Olden Lee, in "Dialogue with Sylvia Olden Lee," Fidelio Magazine, 7/1 (Spring 1998), http://www.schillerinstitute.org/fid_97-01/fid_981_lee_interview.html, accessed 18 January 2013. The remaining quotations in this paragraph come from the same interview.

32 "Plan ‘Bon Voyage' Affair for Everett Lee and Wife," New York Amsterdam News, 13 September 1952.

33 "Negro to Direct in South: Everett Lee Will Conduct White Musicians in Louisville Concert," New York Times, 19 September 1953.

34 This information comes from the program for the Louisville concert, as conveyed by Addie Peyronnin, Operations Assistant, Louisville Orchestra (email to the author, 18 March 2009).

35 Sylvia Lee recalled that the Kathryn Turney Long Department did not allow women to work there during the main opera season, so Lee was employed for six weeks before the season and six weeks afterwards (Cheatham and Lee, 202).

36 "City Opera Engages Two Conductors," New York Times, 10 February 1955.

37 "New York City Opera Chores," New York Times, 22 September 1955.

38 "Conductor," New York Times, 29 April 1956.

39 "To Conduct UN Concert at Philharmonic Hall," New York Amsterdam News, 15 October 1966.

40 Ross Parmenter, "The World of Music," New York Times, 8 July 1962.

41 Sara Slack, "Symphony of the New World A Truly Integrated Group," New York Amsterdam News, 5 March 1966.

42 "New World Symphony Will Play," New York Amsterdam News, 17 April 1965.

43 Raymond Ericson, "Two Elek(c)tras Come to Town," New York Times, 23 October 1966. In 1974, Lee became head conductor of the orchestra (Donal Henahan, "‘New and Newer Music' Begins its Fourth Season," New York Times, 29 January 1974).

44 Harold C. Schonberg, "Everett Lee Leads Philharmonic in Debut," New York Times, 16 January 1976.

45 For example, Columbia Records issued its important "Black Composers Series" between 1974 and 1979.

Dean Dixon

Negro at Home, Maestro Abroad

Dean Dixon: Negro at Home, Maestro Abroad will interest anyone who wants to know more about Black American history, American musical culture, and Black American concert music and musicians.

More information is available at:

"Dean Dixon: Negro at Home, Maestro Abroad" Book Signing

About

Dr. Rufus Jones Jr. is a Texan and a graduate of the University of Texas at Austin. His new book "Dean Dixon: Negro at Home, Maestro Abroad" tells the the compelling true story of the great American conductor, Dean Dixon. He was the first Black American to conduct the New York Philharmonic, and rose to great fame after departing the United States for Europe.

The Barnes and Noble at the Arboretum has scheduled a book signing with author Dr. Jones on June 20, 2015 from 2-4pm.

FULL SYNOPSIS

Despite pervasive intolerance, Dean Dixon became in 1941 the first Black

American to conduct the New York Philharmonic. Yet the acclaim that

followed in his wake could not prevent him from departing his home

country eight years later for Europe. There Dixon moved to a full roster

of prestigious guest conducting appearances across several continents

before returning to conduct once more in the United States. In Dean

Dixon: Negro at Home, Maestro Abroad, conductor and scholar Rufus Jones,

Jr., brings to light a literal treasure trove of unpublished primary

sources to tell the compelling story of this great American conductor. A

testament to Dixon’s resolve, this first ever full-length biography of

this American musical hero chronicles Dixon’s musical upbringing,

beginnings as a conductor, painful decision to leave his own country,

rise to fame in Europe and his triumphant stand twenty-one years later

when he returned to the United States to serve as a model to other black

classical musician, guest conducting at a

number of major symphonies.

Event Details

- Date: June 20, 2015

- Time: 2 - 4 PM

- Venue: Barnes and Noble at the Arboretum

Ticket Information

- Cost: Free

https://www.blogtalkradio.com/patrickdmccoy/2020/07/06/the-maestro-series-a-chat-with-conductor-scholar-and-author-dr-rufus-jones

Presenter Details

THE MAESTRO SERIES: A chat with conductor, scholar and author Dr. Rufus Jones

- Broadcast in Music

Charles Dean Dixon, conductor, was born January 10, 1915 in New York, New York to West Indian parents Henry Charles Dixon and McClara Rolston Dixon. Dixon’s parents exposed him to classical music at an early age and his mother taught him to play the violin, along with a number of other instruments. By the age of nine he was considered a musical prodigy and performed on local radio stations in New York. Dixon enrolled at Juilliard School of Music in 1932 as a violin major, but soon switched to the music pedagogy program and graduated in 1936. He then enrolled in Columbia University and earned a Master’s Degree in Music Pedagogy there in 1939. While at Julliard Dixon discovered conducting and upon graduating he formed the “Dean Dixon Symphony Orchestra,” the first racially integrated group of its type in New York City. Dixon finally returned to the United States in 1970 after his hugely successful career in Europe and Australia.

https://www.overgrownpath.com/2015/04/negro-at-home-maestro-abroad.html

Dean Dixon: Negro at Home, Maestro Abroad is a sobering story of racism, abandonment, self-imposed exile, health problems, spiritual searching, and financial difficulties. But it is also the story of towering achievement. It tells how Dixon returned to conduct the New York Philharmonic in 1970. He had been shunned by the American classical music establishment and this was his first concert in the U.S. for twenty-one years. His conducting moved the Newsweek critic to write:

This was a ripe Dixon, authoritative and precise. He is not a showboat conductor, yet he showered his program with lilting lyricism and controlled grace. And he gave Brahms’s Second Symphony a rich romantic sweep that brought the great throng to its feet in a standing, especially thrilling ovation.But, despite this triumph, the story ends with a diminuendo, with Dr. Jones recounting how the American Dream of the West Indian American from Harlem finally came true - abroad.

With his health broken by the long struggle against discrimination, Dean Dixon died in Switzerland aged just 61 in 1976. But this new biography is much more than an important retelling of history. Speaking at Carnegie Hall in October 2013, Aaron Dworkin founder and president of the Sphinx Organization - a charity promoting diversity in the arts - accused orchestras of failing to diversify. In his speech he pointed out that just four percent of orchestra players in the U.S. are Black and Latino; by comparison the Black and Latino ethnic groups comprise twenty-nine percent of the U.S. population. Aaron Dworkin was especially critical of the New York Philharmonic, highlighting that, at the time, the orchestra had not had a Black member in five years. (The first small step to rectify this imbalance was taken, coincidentally or otherwise, in the following year when clarinettist Anthony McGill became the orchestra's first African-American principal). It is yet another overlooked irony of classical music that so much attention is paid to the deplorable gender imbalance in the Vienna Philharmonic, but so little attention is paid to the equally deplorable but less click baitable ethnic imbalance in virtually every major orchestra. Let us hope that Rufus Jones' timely biography of Dean Dixon helps to draw attention to that imbalance.

* Dean Dixon: Negro at Home, Maestro Abroad by Dr. Rufus Jones is published by Rowman & Littlefield on June 16, 2015.

https://donatocabrera.medium.com/the-music-plays-on-dean-dixon-826c07bf616d

The Music Plays On — Dean Dixon

June 2, 2020

Medium

Charles Dean Dixon was born in Harlem in 1915 to immigrant parents from the West Indies. At an early age his parents exposed him to classical music, and his mother began teaching him violin as well as other instruments. By the age of nine, he was considered a prodigy and was performing on radio stations, and at the age of seventeen was admitted to the Juilliard School as a violin major. He decided to switch his studies and graduated with a music pedagogy degree in 1936. He then pursued a Master’s degree in music pedagogy, graduating from Columbia University in 1936.

While at Juilliard, however, Dixon discovered conducting and when he graduated in 1936 formed the Dean Dixon Symphony Orchestra, which was the first fully integrated orchestra in New York City. Four years later, he conducted the New York City Symphony. In 1941, he conducted the NBC Symphony Orchestra and became the first black conductor to ever lead the New York Philharmonic. During the forties, he also received two prestigious awards, Julius Rosenwald Fellowship and the Alice M. Ditson Award.

Despite all of these accolades, it became clear to Dixon that a career in conducting for a black man in the United States was not going to happen. In 1949, he moved to Europe and remained abroad for the next two decades. His move to Europe paid off, for he had an extraordinary career there and elsewhere, becoming the music director of the Gothenburg Symphony in Sweden (1953–1960), Frankfurt Radio Symphony (1961–1974), and also in Australia as music director of the Sydney Symphony (1964–1967).

His recordings are propulsive and full of life. He made a series of recordings for Westminster and I’ve particularly enjoyed his Schumann symphonies with the Vienna State Opera Orchestra (Vienna Philharmonic) from the early fifties.

A sensitive and stylish Mozart Piano Concerto №22 from 1956 with his then wife, Vivian Rivkin.

A passionate and determined 1953 recording of Liszt’s Les Preludes with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.

Dixon would return to the U.S. in the early 70’s for several guest conducting engagements but returned to his Swiss home in 1975 due to a prevailing heart condition. Dean Dixon passed away in Zug, Switzerland on November 4, 1976. He was 61

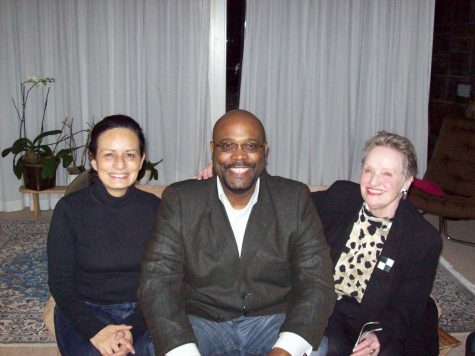

“Just Tell the Story:” Music Director Rufus Jones Paints the Life of Maestro Dean Dixon in Acclaimed 2015 Biography

Music

Director Dr. Rufus Jones published his first autobiography in 2015,

“Dean Dixon: Negro At Home, Maestro Abroad.” The acclaimed book told the

story of trailblazing black orchestral conductor Dean Dixon.

by Kathleen Lewis

Editor-in-Chief

May 17, 2021

It was 2009, and Music Director Dr. Rufus Jones was a professor at Georgetown University and paving his career as an orchestral conductor and educator. He was also deep in the research process of his first biography: that of Dean Dixon, the first black American to lead the New York Philharmonic and NBC Symphony orchestras in 1941.

Jones first discovered Dixon twenty years earlier in an article published in the February 1989 edition of Ebony magazine, which told the stories of twelve trailblazing black symphony conductors. Jones describes coming across the article as a serendipitous, but life-changing moment. Pursuing success in a primarily white-dominated field, Jones was no stranger to racism and prejudice himself, and found Dixon’s story to be an enormous source of inspiration.

“It’s important when you don’t see a lot of people in a profession that look like you to have someone you can be inspired by,” said Jones. “I appreciate [Dixon’s] sacrifice and how it made it more plausible for me to have a career. Despite all the obstacles this man had to face, he became one of the most respected orchestral conductors of the twentieth century.”

When Jones began further researching Dixon, he was surprised to discover that he had no full-length biography, and much of the existing information about him was riddled with inaccuracies. Jones decided to take on the task himself, first with a 2009 article published in the Journal of the Conductor’s Guild. He then continued his work into a nearly 200-page book titled Dean Dixon: Negro At Home, Maestro Abroad.

Jones wanted the book not only to demonstrate the challenges Dixon faced, but also his talents in the genre of classical music and his genius as an orchestral conductor. Yet another surprise arrived when Jones discovered a collection of Dixon’s personal effects and detailed documentation of his life at the Schomburg Center Library in Harlem, N.Y. Jones spent the summer of 2009 examining what grew to become thousands of papers and gathering the necessary information to compile his biography.

“It was really like putting together a puzzle,” recalled Jones. “I wanted for the book to read like a novel and paint all the important moments in [Dixon’s] life. In the end, I was writing in a way that I never thought I was capable of doing.”

Then, Jones made a decision that would become a critical part of the biography’s production: to contact Dixon’s wife and widow Ritha.

During the research process of his book, Jones visited Dean Dixon’s wife Ritha (right) and his daughter Nina (left) in Switzerland in 2009. He describes meeting people who were close to Dixon as a critical step in developing the biography, and dedicated the book to Ritha Dixon. (Rufus Jones)

She invited him and his wife Felicia to visit her home in Switzerland, where they discussed his ideas for the biography, a concept about which the Dixon family had frequently been approached, but never seen completed. Jones promised the skeptical Ritha to fulfill her wish for a written legacy of her husband, and most importantly, to “just tell the story.” The quote became an epigraph credited to co-Pastor at Greater Mount Calvary Holy Church in Washington, D.C., Susie C. Owens, at the beginning of the novel.

After six years of writing, Jones presented the Dixon family with a finished draft of the biography, and chose to dedicate the book to Ritha.

“When Ritha saw the manuscript, she even helped me write the last chapter because I didn’t quite know how to end the story,” said Jones. “She really wanted this story to be told, and all I needed was that she was pleased. She passed away shortly after the book was published, but I think she was at peace.”

When Dean Dixon was published in 2015, Jones was met with responses of gratitude from some of Dixon’s most avid European fans, as well as other successful black musicians and conductors that ones lists in a special “On My Shoulders” section of the book.

The biography has also received significant recognition, such as one of The New Yorker’s most notable music books of 2015.

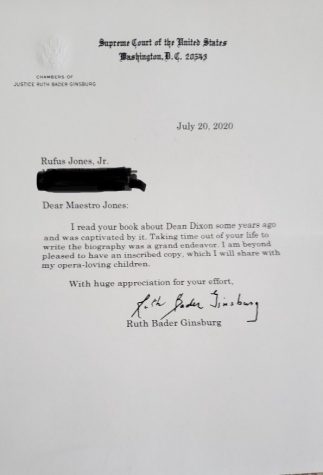

After sending a signed copy of “Dean Dixon” to Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in July 2020, Jones was ecstatic to receive a personal response from Ginsburg. The letter and the magazine article that introduced Jones to Dixon both hang framed in his office today. (Rufus Jones)

“[Dean Dixon’s story] is still very relevant today, and people want to hear about how people have survived obstacles and succeeded as a result,” reflected Jones. “It’s an important story to tell on so many levels, from the musicianship of an orchestral conductor to the struggles of a black man.”

Another personal connection that came out of the biography occurred five years later in July 2020, when Jones decided to send an inscribed copy of the book to Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, notably a lover of classical music.

Jones mentions Ginsburg in the book as one of Dixon’s most appreciative listeners, as she even has spoken about meeting him in person as a child.

No more than two weeks later, Jones received a response written and signed by Ginsburg herself, describing her admiration of Dixon and his music, and her gratitude to Jones for telling his story. The letter harmonizes a framed copy of the original Ebony magazine article on a wall of Jones’ office today as symbols of pride and inspiration, reminding him of the obstacles and challenges that he and others have overcome to achieve success.

https://www.overgrownpath.com/2008/10/dean-dixon-i-owe-him-huge-debt.html

Dear Pliable, As a lonely youngster growing up in Sydney in the sixties, one of the great experiences I had was to hear Dean Dixon in many concerts with the SSO. I got to know the basic classical repetory at the old Sydney Town Hall. Dixon seems to have been forgotten, and I couldn't then judge how good a conductor he was, but I owe him a huge debt. Keep up the good work and remember Dean Dixon!!! Yours David SudlowDavid, thank you for that memory, and for the opportunity to make sure that Dean Dixon, who features in my photos, is neither forgotten nor underrated. He was born in 1915 in New York City and studied at DeWitt Clinton High School in Harlem, then at the Juilliard School and Columbia University. At the age of 26 Dixon became the youngest conductor to lead the then New York Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra, and in 1941 he conducted the NBC Symphony in the orchestra's summer season. He made many recordings of American contemporary music including Henry Cowell's Symphony No. 5, Edward McDowell's Indian Suite, and Douglas Moore's Symphony in A with electronic resources for the the American Recording Society label. In later years Dixon worked with the Philadelphia and Boston orchestras.

From 1949 onwards Dean Dixon enjoyed a distinguished international career that included the position of principal conductor of the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra in Sweden from 1953 to 1960, a post now held by none other than Gustavo Dudamel. Dixon was also principal conductor of the Hess Radio Symphony Orchestra (now HR Symphonie Orchester) in Germany from 1961 to 1970 where the present incumbent is Paavo Järvi, and he also guest conducted with the Israel Philharmonic.

It was a mark of Dixon's reputation that über-modernist William Glock invited him to conduct Mahler's Seventh Symphony with the BBC Symphony Orchestra in the orchestra's 1963-4 season. This was way before the Mahler revival gathered steam; the first complete recorded cycle of Mahler's symphonies was not completed by Leonard Bernstein until 1968, with those of Georg Solti and Bernard Haitink following in the 1970s.