SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2021

VOLUME TEN NUMBER TWO

MARVIN GAYE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

JUNIUS PAUL

(July 10-16)

JAMES BRANDON LEWIS

(July 17-23)

MAZZ SWIFT

(July 24-30)

WARREN WOLF

(July 31-August 6)

VICTOR GOULD

(August 7-13)

SEAN JONES

(August 14-20)

JESSIE MONTGOMERY

(August 21-27)

KAMASI WASHINGTON

(August 28-September 3)

TERRACE MARTIN

(September 4-10)

FLORENCE PRICE

(September 11-17)

HUGH MASEKELA

(September 18-24)

ALFA MIST

(September 25-October 1)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/hugh-masekela-mn0000830319/biography

Hugh Masekela

(1939-2018)

Artist Biography

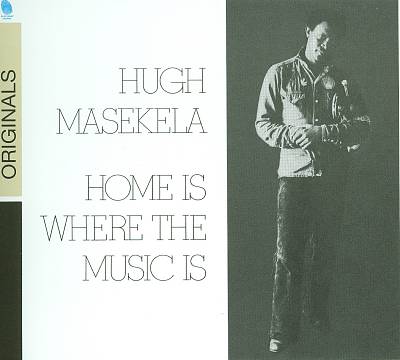

by Thom JurekThough South African trumpeter and bandleader Hugh Masekela possessed an extensive jazz background and credentials, he enjoyed major popular success as one of the earliest innovators in the world fusion genre. Masekela's vibrant trumpet and flügelhorn mixed jazz with South African styles and music from across the African continent and diaspora. His horn was also featured on dozens of recordings in pop, R&B, disco, Afro-pop, and jazz contexts. He had both American and international hits; his 1968 chart-topping cover of "Grazin' in the Grass" also hit the charts in five consecutive decades. He worked with bands around the world and collaborated with a startling array of musicians during a seven-decade career. Exiled from his country for 30 years, he was also a powerful singer/songwriter and activist against apartheid. 1966's The Americanization of Ooga Booga showcased his "township bop" original style. In 1972, Masekela issued the acclaimed double-length Home Is Where the Music Is, uniting funk and fusion with African jazz. Though he often simplified his playing to fit into restrictive pop formulas, Masekela was capable of outstanding ballad and bebop work. His 1979 live outing Main Event with Herb Alpert showcased a dazzling array of styles. While he spent most of the '80s cutting dance club hits, his concerts equally showcased jazz. Masekela resumed charting with his funky smooth jazz releases including 1990's Uptownship (the year he returned home) and 1994's Beatin' Aroun De Bush. In the 21st century, Masekela issued recordings from Johannesburg and Los Angeles including 2005's Rejoice and Just Like Falling in Jazz. 2010's Jabulani topped the South African charts. His final album during his lifetime was the funky world jazz fusion outing No Borders that appeared in 2016.

Masekela began singing and playing piano as a child, influenced by seeing the film Young Man with a Horn at 13. He picked up the trumpet at 14 and played in the Huddleston Jazz Band, which was led by anti-apartheid crusader and group head Trevor Huddleston. Huddleston was eventually deported, and Masekela co-founded the Merry Makers of Springs along with Jonas Gwangwa. He later joined Alfred Herbert's Jazz Revue and played in studio bands backing popular singers. Masekela was in the orchestra for the musical King Kong, whose cast included Miriam Makeba. He was also in the Jazz Epistles with Abdullah Ibrahim, Makaya Ntshoko, Gwanga, and Kippie Moeketsi.

In the aftermath of the March 1960 Sharpeville massacre, Masekela and Makeba, his wife at that time, left South Africa one year before Ibrahim and Sathima Bea Benjamin in 1961. Such musicians as Dizzy Gillespie, John Dankworth, and Harry Belafonte assisted him. Masekela studied at the Royal Academy of Music, then the Manhattan School of Music. During the early '60s, his career began to explode. He recorded for MGM, Mercury, and Verve, developing his hybrid African/pop/jazz style. Masekela moved to California and started his own record label, Chisa, to record himself and other exiled artists. He cut several albums expanding this formula and began to score pop success. The song "Grazing in the Grass" topped the charts in 1968 and eventually sold four million copies worldwide. That year Masekela sold out arenas nationwide during his tour, among them Carnegie Hall. He recorded in the early '70s with Monk Montgomery & the Crusaders.

Masekela moved in a more ethnic direction during the '70s. He traveled to London to play with Nigerian Afro-beat great Fela Kuti & Africa 70; then came a session with Dudu Pukwana, Eddie Gomez, and Ntshoko, among others, that resulted in his finest jazz/African album, Home Is Where the Music Is. Masekela toured Guinea with the Ghanian Afro-pop band Hedzoleh Soundz, then recorded a series of albums with them both in California and Africa, with guest stints from the Crusaders, Patti Austin, and others. Masekela alternated between America and Africa, cutting a successful pop/dance album with Herb Alpert in the late '70s. He was part of Paul Simon's Graceland tour in the mid-'80s, while he continued recording and produced sessions by Makeba.

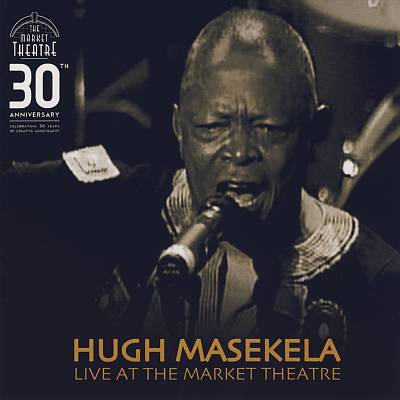

In 1990, when Nelson Mandela was released from prison, Masekela returned to South Africa. He visited Zimbabwe and Botswana, and recorded two albums with the Kalahari Band that once more merged jazz-rock, funk, and pop. Starting in the mid-'90s, Masekela began releasing a stream of albums and collections that showed his versatility and growth in South African jazz. He continued to be active into the first decade of the 21st century, issuing Live at the Market Theatre in 2007, Phola in 2009, and a pair of albums in 2012, Friends (with Larry Willis) and Jabulani, inspired by South African wedding traditions Masekela remembered from his childhood. Though the jazz content of his work varied over the years, Masekela had far more musical material on the plus side than the negative, and his significance as a worldwide symbol against oppression cannot be overemphasized. Hugh Masekela died in Johannesburg in January 2018 at the age of 78.

March of 2020 saw the release of Masekela's collaborative album with pioneering Afrobeat drummer Tony Allen, Rejoice, on World Circuit. Having been friends since they were introduced by Fela Kuti in the early '70s, Masekela and Allen shared many ideas about music and were determined to record together. The opportunity presented itself in 2010 when their touring schedules coincided. They recorded their encounter with producer Nick Gold. The unfinished sessions, consisting of all-original compositions by the pair, lay archived until Masekela passed away. With renewed resolution, Allen and Gold, with the full blessing and participation of Masekela's estate, released an album of collaborations with a host of players who included Joe Armon-Jones, Tom Herbert, Mutale Chashi, and Steve Williamson. They returned to the same London studio used to cut the original sessions. Rejoice was released in March of 2020, just five weeks before Allen's death on April 30, 2020; it marked the final album for both musicians.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/hugh-masekela/

Hugh Masekela

Hugh Masekela was a world-renowned flugelhornist, trumpeter, bandleader, composer, singer and defiant political voice who remained deeply connected at home, while his international career sparkled. He was born in the town of Witbank, South Africa in 1939. At the age of 14, the deeply respected advocator of equal rights in South Africa, Father Trevor Huddleston, provided Masekela with a trumpet and, soon after, the Huddleston Jazz Band was formed. Masekela began to hone his, now signature, Afro-Jazz sound in the late 1950s during a period of intense creative collaboration, most notably performing in the 1959 musical King Kong, written by Todd Matshikiza, and, soon thereafter, as a member of the now legendary South African group, the Jazz Epistles (featuring the classic line up of Kippie Moeketsi, Abdullah Ibrahim and Jonas Gwangwa).

In 1960, at the age of 21 he left South Africa to begin what would be 30 years in exile from the land of his birth. On arrival in New York he enrolled at the Manhattan School of Music. This coincided with a golden era of jazz music and the young Masekela immersed himself in the New York jazz scene where nightly he watched greats like Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, Charlie Mingus and Max Roach. Under the tutelage of Dizzy Gillespie and Louis Armstrong, Hugh was encouraged to develop his own unique style, feeding off African rather than American influences – his debut album, released in 1963, was entitled Trumpet Africaine.

In the late 1960s Hugh moved to Los Angeles in the heat of the ‘Summer of Love’, where he was befriended by hippie icons like David Crosby, Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper. In 1967 Hugh performed at the Monterey Pop Festival alongside Janis Joplin, Otis Redding, Ravi Shankar, The Who and Jimi Hendrix. In 1968, his instrumental single ‘Grazin’ in the Grass’ went to Number One on the American pop charts and was a worldwide smash, elevating Hugh onto the international stage.

His subsequent solo career has spanned 5 decades, during which time he has released over 40 albums (and been featured on countless more) and has worked with such diverse artists as Harry Belafonte, Dizzy Gillespie, The Byrds, Fela Kuti, Marvin Gaye, Herb Alpert, Paul Simon, Stevie Wonder and the late Miriam Makeba.

In 1990 Hugh returned home, following the unbanning of the ANC and the release of Nelson Mandela – an event anticipated in Hugh’s anti-apartheid anthem ‘Bring Home Nelson Mandela’ (1986) which had been a rallying cry around the world.

In 2004 Masekela published his compelling autobiography, Still Grazing: The Musical Journey of Hugh Masekela (co-authored with D. Michael Cheers), which Vanity Fair described thus: ‘…you’ll be in awe of the many lives packed into one.’

In June 2010 he opened the FIFA Soccer World Cup Kick-Off Concert to a global audience and performed at the event’s Opening Ceremony in Soweto’s Soccer City. Later that year he created the mesmerizing musical, Songs of Migration with director, James Ngcobo, which drew critical acclaim and played to packed houses.

That same year, President Zuma honoured him with the highest order in South Africa: The Order of Ikhamanga. 2011 saw Masekela receive a Lifetime Achievement award at the WOMEX World Music Expo in Copenhagen, the first of many. Numerous universities, including the University of York and the University of the Witwatersrand have awarded him honorary doctorates. The US Virgin Islands proclaimed ‘Hugh Masekela Day’ in March 2011, not long after Hugh joined U2 on stage during the Johannesburg leg of their 360 World Tour. U2 frontman Bono described meeting and playing with Hugh as one of the highlights of his career.

Never one to slow down, Bra Hugh toured Europe with Paul Simon on the Graceland 25th Anniversary Tour and opening his own studio and record label, House of Masekela at the age of 75. His final album, No Borders, picked up a SAMA for Best Adult Contemporary in 2017.

Continuing a busy international tour schedule, Hugh used his global reach to spread the word about heritage restoration in Africa – a topic that remained very close to his heart. He founded the Hugh Masekela Heritage Foundation in 2015 to continue this work for generations to come.

“My biggest obsession is to show Africans and the world who the people of Africa really are,”

Hugh Masekela

Early life

Hugh Ramapolo Masekela was born in the township of KwaGuqa in Witbank (now called Emalahleni), South Africa, to Thomas Selena Masekela, who was a health inspector and sculptor and his wife, Pauline Bowers Masekela, a social worker.[2] His younger sister Barbara Masekela is a poet, educator and ANC activist. As a child, he began singing and playing piano and was largely raised by his grandmother, who ran an illegal bar for miners.[2] At the age of 14, after seeing the 1950 film Young Man with a Horn (in which Kirk Douglas plays a character modelled on American jazz cornetist Bix Beiderbecke), Masekela took up playing the trumpet. His first trumpet was bought for him from a local music store by Archbishop Trevor Huddleston,[3] the anti-apartheid chaplain at St. Peter's Secondary School now known as St. Martin's School (Rosettenville).[4][5]

Huddleston asked the leader of the then Johannesburg "Native" Municipal Brass Band, Uncle Sauda, to teach Masekela the rudiments of trumpet playing.[6] Masekela quickly mastered the instrument. Soon, some of his schoolmates also became interested in playing instruments, leading to the formation of the Huddleston Jazz Band, South Africa's first youth orchestra.[6] When Louis Armstrong heard of this band from his friend Huddleston he sent one of his own trumpets as a gift for Hugh.[3] By 1956, after leading other ensembles, Masekela joined Alfred Herbert's African Jazz Revue.[7]

From 1954, Masekela played music that closely reflected his life experience. The agony, conflict, and exploitation faced by South Africa during the 1950s and 1960s inspired and influenced him to make music and also spread political change. He was an artist who in his music vividly portrayed the struggles and sorrows, as well as the joys and passions of his country. His music protested about apartheid, slavery, government; the hardships individuals were living. Masekela reached a large population that also felt oppressed due to the country's situation.[8][9]

Following a Manhattan Brothers tour of South Africa in 1958, Masekela wound up in the orchestra of the musical King Kong, written by Todd Matshikiza.[10] King Kong was South Africa's first blockbuster theatrical success, touring the country for a sold-out year with Miriam Makeba and the Manhattan Brothers' Nathan Mdledle in the lead. The musical later went to London's West End for two years.[11]

Career

At the end of 1959, Dollar Brand (later known as Abdullah Ibrahim), Kippie Moeketsi, Makhaya Ntshoko, Jonas Gwangwa, Johnny Gertze and Hugh formed the Jazz Epistles,[12] the first African jazz group to record an LP. They performed to record-breaking audiences in Johannesburg and Cape Town through late 1959 to early 1960.[2][13]

Following the 21 March 1960 Sharpeville massacre—where 69 protestors were shot dead in Sharpeville, and the South African government banned gatherings of ten or more people—and the increased brutality of the Apartheid state, Masekela left the country. He was helped by Trevor Huddleston and international friends such as Yehudi Menuhin and John Dankworth, who got him admitted into London's Guildhall School of Music in 1960.[14] During that period, Masekela visited the United States, where he was befriended by Harry Belafonte.[15] After securing a scholarship back in London,[2] Masekela moved to the United States to attend the Manhattan School of Music in New York, where he studied classical trumpet from 1960 to 1964.[16] In 1964, Miriam Makeba and Masekela were married, divorcing two years later.[16]

He had hits in the US with the pop jazz tunes "Up, Up and Away" (1967) and the number-one smash "Grazing in the Grass" (1968), which sold four million copies.[17] He also appeared at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, and was subsequently featured in the film Monterey Pop by D. A. Pennebaker. In 1974, Masekela and friend Stewart Levine organised the Zaire 74 music festival in Kinshasa set around the Rumble in the Jungle boxing match.[18]

He played primarily in jazz ensembles, with guest appearances on recordings by The Byrds ("So You Want to Be a Rock 'n' Roll Star" and "Lady Friend") and Paul Simon ("Further to Fly"). In 1984, Masekela released the album Techno Bush; from that album, a single entitled "Don't Go Lose It Baby" peaked at number two for two weeks on the dance charts.[19] In 1987, he had a hit single with "Bring Him Back Home". The song became enormously popular, and turned into an unofficial anthem of the anti-apartheid movement and an anthem for the movement to free Nelson Mandela.[20][21]

A renewed interest in his African roots led Masekela to collaborate with West and Central African musicians, and finally to reconnect with Southern African players when he set up with the help of Jive Records a mobile studio in Botswana, just over the South African border, from 1980 to 1984. Here he re-absorbed and re-used mbaqanga strains, a style he continued to use following his return to South Africa in the early 1990s.[22]

In 1985 Masekela founded the Botswana International School of Music (BISM), which held its first workshop in Gaborone in that year.[23][24] The event, still in existence, continues as the annual Botswana Music Camp, giving local musicians of all ages and from all backgrounds the opportunity to play and perform together. Masekela taught the jazz course at the first workshop, and performed at the final concert.[25][26][27]

Also in the 1980s, Masekela toured with Paul Simon in support of Simon's album Graceland, which featured other South African artists such as Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Miriam Makeba, Ray Phiri, and other elements of the band Kalahari, which was co-founded by guitarist Banjo Mosele and which backed Masekela in the 1980s.[28] As well as recording with Kalahari,[29] he also collaborated in the musical development for the Broadway play Sarafina!, which premiered in 1988.[30][31]

In 2003, he was featured in the documentary film Amandla!: A Revolution in Four-Part Harmony. In 2004, he released his autobiography, Still Grazing: The Musical Journey of Hugh Masekela, co-authored with journalist D. Michael Cheers,[32] which detailed Masekela's struggles against apartheid in his homeland, as well as his personal struggles with alcoholism from the late 1970s to the 1990s. In this period, he migrated, in his personal recording career, to mbaqanga, jazz/funk, and the blending of South African sounds, through two albums he recorded with Herb Alpert, and solo recordings, Techno-Bush (recorded in his studio in Botswana), Tomorrow (featuring the anthem "Bring Him Back Home"), Uptownship (a lush-sounding ode to American R&B), Beatin' Aroun de Bush, Sixty, Time, and Revival. His song "Soweto Blues", sung by his former wife, Miriam Makeba, is a blues/jazz piece that mourns the carnage of the Soweto riots in 1976.[33] He also provided interpretations of songs composed by Jorge Ben, Antônio Carlos Jobim, Caiphus Semenya, Jonas Gwangwa, Dorothy Masuka, and Fela Kuti.

In 2006 Masekela was described by Michael A. Gomez, professor of history and Middle Eastern and Islamic studies at New York University as "the father of African jazz."[34][35]

In 2009, Masekela released the album Phola (meaning "to get well, to heal"), his second recording for 4 Quarters Entertainment/Times Square Records. It includes some songs he wrote in the 1980s but never completed, as well as a reinterpretation of "The Joke of Life (Brinca de Vivre)", which he recorded in the mid-1980s. From October 2007, he was a board member of the Woyome Foundation for Africa.[36][37]

In 2010, Masekela was featured, with his son Selema Masekela, in a series of videos on ESPN. The series, called Umlando – Through My Father's Eyes, was aired in 10 parts during ESPN's coverage of the FIFA World Cup in South Africa. The series focused on Hugh's and Selema's travels through South Africa. Hugh brought his son to the places he grew up. It was Selema's first trip to his father's homeland.[38]

On 3 December 2013, Masekela guested with the Dave Matthews Band in Johannesburg, South Africa. He joined Rashawn Ross on trumpet for "Proudest Monkey" and "Grazing in the Grass".[39]

In 2016, at Emperors Palace, Johannesburg, Masekela and Abdullah Ibrahim performed together for the first time in 60 years, reuniting the Jazz Epistles in commemoration of the 40th anniversary of the historic 16 June 1976 youth demonstrations.[40][41][42]

Social initiatives

Masekela was involved in several social initiatives, and served as a director on the board of the Lunchbox Fund, a non-profit organization that provides a daily meal to students of township schools in Soweto.[43][44]

Personal life and death

From 1964 to 1966 Masekela was married to singer and activist Miriam Makeba.[45][46] He had subsequent marriages to Chris Calloway (daughter of Cab Calloway), Jabu Mbatha, and Elinam Cofie.[16] During the last few years of his life, he lived with the dancer Nomsa Manaka.[47] He was the father of American television host Sal Masekela.[44] Poet, educator, and activist Barbara Masekela is his younger sister.[48]

Masekela died in Johannesburg on the early morning of 23 January 2018 from prostate cancer, aged 78.[1][45][49]

Awards and honours

Masekela was honoured with a Google Doodle on 4 April 2019, which would have been his 80th birthday. The Doodle depicts Masekela, dressed in colourful shirt, playing a flugelhorn in front of a banner.

Grammy history

Masekela was nominated for an Grammy Award three times, including a nomination for Best World Music Album for his 2012 album Jabulani, one for Best Musical Cast Show Album for Sarafina! The Music Of Liberation (1989) and one for Best Contemporary Pop Performance for the song "Grazing in the Grass" (1968).[22][50][51]

Honours

- Rhodes University: Doctor of Music (honoris causa), 2015[52]

- University of York: Honorary Doctorate in Music 2014[53]

- Order of Ikhamanga: 2010 South African National Orders Ceremony, 27 April 2010[16]

- Ghana Music Awards: 2007 African Music Legend award[54]

- 2005 Channel O Music Video Awards: Lifetime Achievement Award[55]

- 2002 BBC Radio Jazz Awards: International Award of the Year[56]

- Nominated for Broadway's 1988 Tony Award for Best Score (Musical), with music and lyrics collaborator Mbongeni Ngema, for Sarafina![57]

- 2016 MTV Africa Music Awards (MAMAs): Legend Award[58]

Discography

Albums

| Year | Title | Label (original issue) |

|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Trumpet Africaine | Mercury (Aug)[59] |

| 1966 | Grrr | Mercury MG-21109, SR-61109 (Apr)[60] |

| 1966 | The Americanization of Ooga Booga | MGM E/SE-4372 (Jun)[61] |

| 1966 | Hugh Masekela's Next Album | MGM E/SE-4415 (Dec)[62] |

| 1966 | The Emancipation of Hugh Masekela | Chisa Records CHS-4101[60] |

| 1967 | Hugh Masekela's Latest | Uni 3010, 73010[60] |

| 1967 | Hugh Masekela Is Alive and Well at the Whisky | Uni 3015, 73015[60] |

| 1968 | The Promise of a Future | Uni 73028[60] |

| 1968 | Africa '68 | Uni 73020[63] |

| 1968 | The Lasting Impression of Hugh Masekela | MGM E/SE-4468 (Dec)[60] |

| 1969 | Masekela | Uni 73041[60] |

| 1970 | Reconstruction | Chisa CS 803 (Jul)[60] |

| 1971 | Hugh Masekela & The Union of South Africa | Chisa CS 808 (May)[60] |

| 1972 | Home Is Where the Music Is (aka The African Connection) | Blue Thumb Chisa BTS 6003[60] |

| 1973 | Introducing Hedzoleh Soundz | Blue Thumb Chisa BTS 62[60] |

| 1974 | I Am Not Afraid | Blue Thumb Chisa BTS 6015[60] |

| 1975 | The Boy's Doin' It | Casablanca NBLP-7017 (Jun)[60] |

| 1976 | Colonial Man | Casablanca NBLP-7023 (Jan)[60] |

| 1976 | Melody Maker | Casablanca NBLP-7036[60] |

| 1977 | You Told Your Mama Not to Worry | Casablanca NBLP-7079[60] |

| 1978 | Herb Alpert / Hugh Masekela | Horizon SP-728[60] |

| 1978 | Main Event Live (with Herb Alpert) | A&M SP-4727[60] |

| 1982 | Home | Moonshine/Columbia[60] |

| 1984 | Techno-Bush | Jive Afrika[60] |

| 1985 | Waiting for the Rain | Jive Afrika[60] |

| 1987 | Tomorrow | Warner Bros.[60] |

| 1987 | Uptownship | Jive/Novus Records[60] |

| 1992 | Beatin' Aroun de Bush | Novus Records[60] |

| 1994 | Hope | Triloka Records[60] |

| 1994 | Stimela | Connoisseur Collection[64] |

| 1996 | Notes of Life | Columbia/Music[60] |

| 1998 | Black to the Future | Shanachie Records[60] |

| 1999 | The Best of Hugh Masekela on Novus | RCA[65] |

| 1999 | Sixty | Shanachie[60] |

| 2001 | Grazing in the Grass: The Best of Hugh Masekela | Sony[66] |

| 2002 | Time | Columbia[60] |

| 2002 | Live at the BBC | Strange Fruit[60] |

| 2003 | The Collection | Universal/Spectrum[67] |

| 2004 | Still Grazing | Blue Thumb[68] |

| 2005 | Revival | Heads Up[60] |

| 2005 | Almost Like Being in Jazz | Chissa Records[69] |

| 2006 | The Chisa Years: 1965–1975 (Rare and Unreleased) | BBE[70] |

| 2007 | Live at the Market Theatre | Four-Quarters Ent[60] |

| 2009 | Phola | Four-Quarters Ent[60] |

| 2012 | Jabulani | Listen 2[71] |

| 2011 | Friends (Hugh Masekela and Larry Willis) | House of Masekela[72] |

| 2012 | Playing @ Work | House of Masekela[73] |

| 2016 | No Borders | Universal Music |

| 2020 | Rejoice (Tony Allen and Hugh Masekela) | World Circuit |

Autobiography

- With D. Michael Cheers (2004). Still Grazing: The Musical Journey of Hugh Masekela, Crown, ISBN 978-0-609-60957-6

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/23/obituaries/hugh-masekela-dies.html

Hugh Masekela, Trumpeter and Anti-Apartheid Activist, Dies at 78

Hugh Masekela, a South African trumpeter, singer and activist whose music became symbolic of the country’s anti-apartheid movement, even as he spent three decades in exile, died on Tuesday in Johannesburg. He was 78.

His death was confirmed by Dreamcatcher, a communications agency that represented him.

Mr. Masekela came to the forefront of his country’s music scene in the 1950s, when he became a pioneer of South African jazz as a member of the Jazz Epistles, a bebop sextet that included the pianist Abdullah Ibrahim and other future stars. After a move to the United States in 1960, he won international acclaim and carried the mantle of his country’s freedom struggle.

His biggest hit was “Grazing in the Grass,” a peppy instrumental from 1968 with a twirling trumpet hook and a jangly cowbell rhythm. In the 1980s, as the struggle against apartheid hit a fever pitch, he worked often with fellow expatriate musicians, and with others from different African nations. On songs like “Stimela (Coal Train),” “Mace and Grenades” and the anthem “Mandela (Bring Him Back Home),” he played spiraling, plump-toned trumpet lines and sang of fortitude and resisting oppression in a gravelly tenor, landing somewhere between a storyteller’s incantation and a folk singer’s croon.

In the 1970s and ’80s, he collaborated with musicians across sub-Saharan Africa, constantly expanding his style to accommodate a range of traditions.

In 1986, Mr. Masekela founded the Botswana International School of Music, a nonprofit organization aimed at educating young African musicians. The next year, he played with Paul Simon and Ladysmith Black Mambazo on the “Graceland” tour, which was not allowed in South Africa but made stops in nearby countries. On that tour, Mr. Masekela often performed “Mandela (Bring Him Back Home),” a hit song demanding justice for Nelson Mandela, who was imprisoned on Robben Island at the time.

Reviewing a 1989 performance by Mr. Masekela in New York City, Peter Watrous wrote in The New York Times:

“Mr. Masekela, playing the cornet, contrasted short melodies against

bristling long lines that flowed with the authority and phrasing

reminiscent of the trumpeter Clifford Brown. When he sang, in the hoarse

shout of the township music from Johannesburg, the band percolated

behind him. The show ended with a tribute to Nelson Mandela, which had

the audience both dancing and holding fists in the air.”

Mr. Masekela tended to emphasize the breadth of the musical tradition that inspired him. “I was marinated in jazz, and I was seasoned in music from home,” he said in a 2009 interview with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. “Song is the literature of South Africa.”

He added, “There’s no political rally that ever happened in South Africa without singing being the main feature.”

Throughout his time in exile, Mr. Masekela remained committed to seeing democracy implemented in his home country. His son, Sal Masekela, noted in a statement that “despite the open arms of many countries, for 30 years he refused to take citizenship anywhere else on this earth” because of his belief “that the pure evil of a systematic racist oppression could and would be crushed.”

Ramopolo Hugh Masekela was born on April 4, 1939, in Witbank, South Africa, a coal-mining town near Johannesburg. His father, Thomas Selema Masekela, was a health inspector and noted sculptor; his mother, Pauline Bowers Masekela, was a social worker.

As a young child, Mr. Masekela was raised primarily by his grandmother, who ran an illegal bar for mine workers. “One of the great things also about Witbank was that all these people brought their different music and their different stories about where they came from,” he said of the miners. “As a little kid, I hung out with them in the backyard and the kitchen and I knew all about their countries.”

When he was 12, he entered St. Peter’s Secondary School, a boarding school in Rosettenville, closer to Johannesburg. By that point he had already begun to pursue music, singing in groups on the street and learning piano in private lessons.

He grew infatuated with the trumpet in 1950, after seeing Kirk Douglas in the film “Young Man With a Horn,” based on a novel inspired by the life of the trumpeter Bix Beiderbecke.

At St. Peter’s, he was encouraged to pursue music by Archbishop Trevor Huddleston, an influential anti-apartheid advocate and organizer. He took lessons from Uncle Sauda, an esteemed local trumpeter, and quickly mastered the basics. Archbishop Huddleston established the Huddleston Jazz Band, a youth orchestra, partly to give Mr. Masekela an opportunity to play, and later, during a trip to the United States, he met Louis Armstrong, who had a trumpet sent to the band. The instrument made its way into Mr. Masekela’s hands.

By 1956, Mr. Masekela was performing in dance bands around Johannesburg and in cities across the country. In 1959, he played in the pit band of the hit musical “King Kong,” with music composed by the seminal South African pianist Todd Matshikiza.

The next year he joined Abdullah Ibrahim (then known as Dollar Brand) and four other upstart instrumentalists in the Jazz Epistles, South Africa’s first bebop band of note. With a heavy, driving pulse and warm, arcing melodies, their music was distinctly South African, even as its swing rhythms and flittering improvisations reflected affinities with American jazz.

“There had never been a group like the Epistles in South Africa,” Mr. Masekela said in his 2004 autobiography, “Still Grazing: The Musical Journey of Hugh Masekela,” written with D. Michael Cheers. “Our tireless energy, complex arrangements, tight ensemble play, languid slow ballads and heart-melting, hymnlike dirges won us a following, and soon we were breaking all attendance records in Cape Town.”

The group recorded just one album, which was printed in a run of 500 and eventually became a kind of Holy Grail for collectors.

After the so-called Sharpeville massacre in March 1960, in which 69 protesters were killed by police officers in a township outside Johannesburg, the government banned public gatherings of more than 10 black people. This forced groups like the Jazz Epistles to take their performances underground; Mr. Masekela and Mr. Ibrahim soon chose to leave the country.

In 1960, Mr. Masekela moved briefly to London, where he studied at the Guildhall School of Music, before the singers Harry Belafonte and Miriam Makeba helped him secure a scholarship to attend the Manhattan School of Music. He studied classical trumpet there for four years.

In 1962, he recorded his debut album, “Trumpet Africaine,” for the Mercury label. He followed it in 1964 with “Grrr,” also on Mercury. That album — which featured the trombonist Jonas Gwangwa, a veteran of the Jazz Epistles who had also relocated to New York — included a number of Masekela originals that reflected his devotion to his musical roots. On tunes like “Sharpeville,” the effortless churn of the rhythms and the thrumming harmonies reflected the influence of marabi, an instrumental style developed in the early 20th century by workers in the townships outside Johannesburg.

During this time, Mr. Masekela often wrote instrumental arrangements for Ms. Makeba. Their partnership turned romantic, and the couple married in 1964. The marriage ended in divorce two years later, but the two later continued to collaborate.

Mr. Masekela is survived by a son, Sal Masekela, from his relationship with Jessie Marie Lapierre; a daughter, Pula Twala, from his relationship with Motshidisi Jennifer Ndamse; and his sisters, Elaine and Barbara Masekela. Three other marriages — to Chris Calloway, Jabu Mbatha and Elinam Cofie — also ended in divorce.

In 1964, Mr. Masekela and Stewart Levine, a fellow student at the Manhattan School, established the independent label Chisa, named for the Zulu word for “burn.” The two would remain lifelong collaborators and friends.

The label struck gold in 1968 when Mr. Masekela released the album “The Promise of a Future,” featuring “Grazing in the Grass.” With a sanguine two-chord hook, the song registered as a beatific ode to summer; it was released in May and hit No. 1 on the Billboard charts in mid-July.

By that time, Mr. Masekela had begun to sing; on other tracks on the album, including “Vuca (Wake Up)” and “Bajabula Bonke (The Healing Song),” he sang in Zulu, sounding tones of uplift and resistance.

But alongside success came overindulgence. Mr. Masekela developed a dependence on alcohol early in his career, and by the early 1970s he was addicted to cocaine, as well. His substance abuse began to inhibit his work. “No recording company was interested in me,” he told the music historian Gwen Ansell last year.

He sought solace on his home continent. “For me, songs come like a tidal wave,” he said. “At this low point, for some reason, the tidal wave that whooshed in on me came all the way from the other side of the Atlantic: from Africa, from home.”

In the 1970s, Mr. Masekela toured sub-Sarahan Africa and began a partnership with the Nigerian musician Fela Kuti, who had recently pioneered the genre known as Afrobeat. He also worked with the exiled South African saxophonist Dudu Pukwana and began fronting the Ghanaian group Hedzoleh Soundz. He recorded two albums with the group, “Introducing Hedzoleh Soundz” and “I Am Not Afraid,” and toured the United States with them in 1974.

Partly thanks to Mr. Kuti’s influence, Mr. Masekela began to record longer, more immersive tracks, using electronic effects and letting grooves linger for minutes on end. That style is heard to perhaps its greatest effect on “The Boy’s Doin’ It,” which Mr. Masekela recorded in Lagos with Nigerian musicians in 1975.

When he kicked his addictions in the 1990s, Mr. Masekela established the Musicians and Artists Assistance Program of South Africa, to help South Africans battle substance abuse.

In 1980, Mr. Masekela returned to Africa. He settled in Botswana, where he set up a mobile recording studio and recorded two albums. In 1987, he traveled to London to record the album “Tomorrow,” which included “Mandela (Bring Him Back Home).”

Mr. Masekela moved back to South Africa in 1990, the year Mandela was released from prison. He continued to record and tour around the world into his mid-70s.

In 2010, Mr. Masekela was awarded the Order of Ikhamanga in gold, South Africa’s highest medal of honor. Since 2014, Soweto has been the site of an annual Hugh Masekela Heritage Festival, with the stated aim “to restore our South African heritage and to uplift the local artisans of Soweto.”

IN TRIBUTE TO THE INSPIRING AND LEGENDARY MUSICIAN, COMPOSER, ACTIVIST, ARTIST, AND TEACHER

HUGH MASEKELA (1939-2018). MAY HIS MAGNIFICENT MUSIC AND SPIRIT CONTINUE TO PERVADE OUR LIVES FOREVER AND FOREVERMORE...

RIP BROTHER...

Hugh Masekela "Celebrate Mama Africa" - Estival Jazz Lugano 2011

Italy

News Assupol presents the 4th annual Hugh Masekela Heritage Festival 3rd October 2017 The line-up is curated by Bra Hugh who is passionate about the power and potential

of our nation’s cultural diversity.

Published on May 19, 2014

http://www.hughmasekela.co.za/, http://www.estivaljazz.ch/

Hugh Masekela - flugelhorn and vocals

Lira - voc

Thandiswa - voc

Vusi Mahlasela - voc, g

John Cameron Ward - g

Fana Zulu - b

Randal Skippers - keys

Lee Roy Sauls - dr

Francis Manneh Fuster - perc

Hugh Masekela: "Celebrate Mama Africa"

Live at Estival Jazz Lugano 2011

Biography

Hugh Masekela was a world-renowned flugelhornist, trumpeter, bandleader, composer, singer and defiant political voice who remained deeply connected at home, while his international career sparkled. He was born in the town of Witbank, South Africa in 1939. At the age of 14, the deeply respected advocator of equal rights in South Africa, Father Trevor Huddleston, provided Masekela with a trumpet and, soon after, the Huddleston Jazz Band was formed. Masekela began to hone his, now signature, Afro-Jazz sound in the late 1950s during a period of intense creative collaboration, most notably performing in the 1959 musical King Kong, written by Todd Matshikiza, and, soon thereafter, as a member of the now legendary South African group, the Jazz Epistles (featuring the classic line up of Kippie Moeketsi, Abdullah Ibrahim and Jonas Gwangwa).

In 1960, at the age of 21 he left South Africa to begin what would be 30 years in exile from the land of his birth. On arrival in New York he enrolled at the Manhattan School of Music. This coincided with a golden era of jazz music and the young Masekela immersed himself in the New York jazz scene where nightly he watched greats like Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, Charlie Mingus and Max Roach. Under the tutelage of Dizzy Gillespie and Louis Armstrong, Hugh was encouraged to develop his own unique style, feeding off African rather than American influences – his debut album, released in 1963, was entitled Trumpet Africaine.

In the late 1960s Hugh moved to Los Angeles in the heat of the ‘Summer of Love’, where he was befriended by hippie icons like David Crosby, Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper. In 1967 Hugh performed at the Monterey Pop Festival alongside Janis Joplin, Otis Redding, Ravi Shankar, The Who and Jimi Hendrix. In 1968, his instrumental single ‘Grazin’ in the Grass’ went to Number One on the American pop charts and was a worldwide smash, elevating Hugh onto the international stage.

His subsequent solo career has spanned 5 decades, during which time he has released over 40 albums (and been featured on countless more) and has worked with such diverse artists as Harry Belafonte, Dizzy Gillespie, The Byrds, Fela Kuti, Marvin Gaye, Herb Alpert, Paul Simon, Stevie Wonder and the late Miriam Makeba.

In 1990 Hugh returned home, following the unbanning of the ANC and the release of Nelson Mandela – an event anticipated in Hugh’s anti-apartheid anthem ‘Bring Home Nelson Mandela’ (1986) which had been a rallying cry around the world.

In 2004 Masekela published his compelling autobiography, Still Grazing: The Musical Journey of Hugh Masekela (co-authored with D. Michael Cheers), which Vanity Fair described thus: ‘…you’ll be in awe of the many lives packed into one.’

In June 2010 he opened the FIFA Soccer World Cup Kick-Off Concert to a global audience and performed at the event’s Opening Ceremony in Soweto’s Soccer City. Later that year he created the mesmerizing musical, Songs of Migration with director, James Ngcobo, which drew critical acclaim and played to packed houses.

That same year, President Zuma honoured him with the highest order in South Africa: The Order of Ikhamanga. 2011 saw Masekela receive a Lifetime Achievement award at the WOMEX World Music Expo in Copenhagen, the first of many. Numerous universities, including the University of York and the University of the Witwatersrand have awarded him honorary doctorates. The US Virgin Islands proclaimed ‘Hugh Masekela Day’ in March 2011, not long after Hugh joined U2 on stage during the Johannesburg leg of their 360 World Tour. U2 frontman Bono described meeting and playing with Hugh as one of the highlights of his career.

Never one to slow down, Bra Hugh toured Europe with Paul Simon on the Graceland 25th Anniversary Tour and opening his own studio and record label, House of Masekela at the age of 75. His final album, No Borders, picked up a SAMA for Best Adult Contemporary in 2017.

Continuing a busy international tour schedule, Hugh used his global reach to spread the word about heritage restoration in Africa – a topic that remained very close to his heart. He founded the Hugh Masekela Heritage Foundation in 2015 to continue this work for generations to come.

“My biggest obsession is to show Africans and the world who the people of Africa really are,”

Masekela confided – It was this commitment to his home continent that propelled him forward since he first began playing the trumpet.

Hugh Masekela – 4 April 1939 to 23 January 2018

nonfiction

Hugh Masekela: The Horn of Freedom

Karen J. Borek, University of Pennsylvania

South African jazz musician, composer, and singer Hugh Masekela has combined African rhythmic patterns and mbhaqanga strains with Western swing and jazz to create his “hybrid style” of popular music. Mbhaqanga, as Masekela claims in his autobiography, “was the dominant music of the townships in South Africa,” and consisted of traditional chanting and drumming with jazz (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 3). Masekela was born in Witbank, South Africa, a coal-mining town near Johannesburg, on April 4, 1939. Although he grew up in a culture surrounded by rallies and protests against the apartheid government, Masekela commented that he did not intend to use music for political activism. Masekela’s music, however, does reflect the turbulent times, and it stirred anti-apartheid sentiments and concern for human rights. During an interview with television host Charlie Rose, Masekela noted that “Music was the major catalyst for our freedom” (Masekela 2009). Named after his 1968 popular instrumental song “Grazing in the Grass,” Masekela’s 2004 autobiography Still Grazing: The Musical Journey of Hugh Masekela, co-authored by photo-journalist and professor D. Michael Cheers, traces his life experiences and musical career. Several of Masekela’s songs, including “Grazing in the Grass,” “Stimela,” “Been Such a Long Time Gone,” “Bring Him Back Home,” and “Ikhaya Lami” illustrate his musical versatility and African heritage. Africa’s beauty, freedom, oppression of people under apartheid rule, and celebration are some themes in his songs. Masekela’s songs express the traditions and social issues of his country’s ethnic cultures: Xhosa, Zulu, Sotho, Khoi-san, Shangaan, Ndebele, and others, as well as the urban sounds of the townships. As his talent evolved, Hugh Masekela’s music played a crucial role in the nation’s transition from apartheid to a non-racial democracy.

Masekela’s fascination with musical sounds, especially jazz rhythms, began in his early childhood. He started singing to the records on his uncle’s gramophone at the age of three without knowing what the words meant (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 9). At his grandmother’s shebeen, or illegal drinking place, Masekela witnessed drunken miners and other people who sang their troubles away. During his grade school years, Masekela’s parents gave him piano lessons. At the age of fourteen, Masekela watched the 1949 movie Young Man with a Horn about American jazz trumpeter Leon “Bix” Beiderbecke, played by Kirk Douglas, which inspired him to play the trumpet. Masekela envisioned the trumpet as a symbol of freedom.

While Masekela attended St. Peter’s Secondary School, a boarding school in Sophiatown, the Anglican anti-apartheid chaplain Father Trevor Huddleston had a major impact on Masekela’s musical talent. Huddleston arranged for Masekela to receive a used trumpet from a local shop and to take trumpet lessons from Uncle Sauda of the Johannesburg Native Municipal Brass Band. When other schoolmates acquired musical instruments, Father Huddleston started the Huddleston Jazz Band, the first youth band in South Africa. Eventually, Huddleston was deported to England as a result of his protest of the 1953 Bantu Education Act and the school’s closing. The Bantu Education Act provided government control over schools, including missionary schools like St. Peter’s, formerly run by a church. This act also created segregated education, which gave black students a substandard curriculum.

Before returning to England, Father Huddleston went to the United States to visit a friend. In Rochester, New York, Huddleston went to a concert, met Louis Armstrong backstage, and mentioned the South African youth band. Louis Armstrong hoped to inspire a young musician from this distant place by donating one of his horns, which was mailed to South Africa by his wife Lucille. When Hugh Masekela received Armstrong’s trumpet at the age of seventeen, he was thrilled. Masekela later wrote that receiving Armstrong’s trumpet made him feel “something like a spiritual connection with Satchmo and those musicians back in the states”: a connection to a “tradition that had crisscrossed the Atlantic from Africa to America and back” (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 82). The cover of his 2004 autobiography shows the young Hugh Masekela jumping for joy with his new trumpet in Sophiatown before the forced relocation of its black residents during apartheid. Although he had toured other African countries, “Satchmo” was denied entry into South Africa in 1960 “because Armstrong refused to play to segregated audiences” (Musinguzi 2012). Masekela finally met and thanked Louis Armstrong for the trumpet when Masekela accompanied singer Miriam Makeba at the 1964 Grammy Awards at the Hotel Astor in New York City. Armstrong won the award that year for Best Male Vocal Performance for the play Hello Dolly. Currently, the trumpet remains on display at the Cape Town Heritage Museum (Poole 2004).

As a teenager, Masekela performed with various groups, including the Huddleston Jazz Band, the Merry Makers, and Alfred Herbert’s African Jazz and Variety Show. Masekela also performed with the Manhattan Brothers, and he played the trumpet in the orchestra for Todd Matshikiza’s musical King Kong (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 97). A few years after receiving Armstrong’s trumpet, Hugh Masekela, in 1959, co-founded the Jazz Epistles band with pianist Dollar Brand (Abdullah Ibrahaim). In January 1960, a turning point for Masekela took place when he was accepted “through the intercession of musicians Yehudi Menuhin and Johnny Dankworth,” associates of his former mentor Father Huddleston, to London’s Guildhall School of Music (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 104). While planning a nationwide tour with the Jazz Epistles and awaiting a passport to attend school in London, Masekela experienced another turning point on both a personal and a national level. On March 21, 1960, the Sharpeville Massacre occurred in South Africa. The apartheid police force fired at and killed sixty-nine people and injured many more who were peacefully demonstrating against pass laws that required every non-white African to carry a pass book. A state of emergency was declared by the government, which forbid meetings of more than ten people (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 106). Consequently, Masekela’s tour with the Jazz Epistles was canceled, and so he left the country in May of 1960 to study music in London. Later, African singer Miriam Makeba came to London. Makeba together with jazz musicians Dizzy Gillespie and John Mehegan helped Masekela obtain an American scholarship and acceptance “into the Manhattan School of Music in New York” where he studied from 1960 to 1964 (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 119).

Although Masekela had previously recorded an album with the Jazz Epistles band, he completed his first solo album, Trumpet Africaine, in 1962; this first recording from Masekela echoed American jazz styles. The album was unpopular, so Masekela and his mentor, Harry Belafonte, became convinced that Masekela should combine some African township rhythms with American jazz styles in future records. Later, Masekela went on a pilgrimage to different African countries where he met the Ghanian band Hedzoleh Soundz, Afrobeat musician Fela Kuti, and others who influenced his style.

An early jazz pop instrumental song “Grazing in the Grass,” with its combination of jazz and African rhythms, made Hugh Masekela famous. Composed by Philemon Hou in 1968, it became a number one hit, “a first for an African musician” according to D. Michael Cheers (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 213). This instrumental version of “Grazing in the Grass” placed South Africa on the world music map. The song sold more than four million copies in the United States and around the world. Recognition from the song allowed Masekela to become an influential voice in his country’s freedom struggle. “Grazing in the Grass” was included in Masekela’s album Promise of a Future (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 194). The song has an upbeat melody with Masekela beating on a cowbell and playing his trumpet. Also, the song suggests the instinctual freedom of cattle grazing on the veld. Some people thought that the song might refer to being high from smoking marijuana, also known by its nickname grass, but this has not been proven. In 1969, Harry Elston of The Friends of Distinction group wrote lyrics to the song including the words: “Grazin’ in the grass is a gas, baby, can you dig it?” Their recording with lyrics and a faster tempo also became a popular hit song.

A year before recording “Grazing in the Grass,” Masekela played his trumpet with the Byrds at the Monterey International Pop Festival in Monterey, California in 1967. They performed their pop hit “So You Want to be a Rock’ n’ Roll Star” (Kubernik and Kubernik 2011, 122). In addition, Masekela played a part in the documentary film Monterey Pop about the festival.

When returning to live in Woodstock, New York, Hugh Masekela experienced a creative streak one day upon recalling his birthplace of Witbank. Lyrics spontaneously came into his head, and Masekela composed the song “Stimela (The Coal Train).” Masekela recalled the sounds made by coal-operated steam trains, and, perhaps, he also thought about the American jazz saxophonist John Coltrane (nicknamed Trane), who performed in New York at the time. As he wrote in his autobiography, Masekela recorded “Stimela” later in 1974 in the United States in collaboration with the Hedzoleh Soundz band for the album I Am Not Afraid. Masekela stated that this album “was instrumental in shifting our style more toward a heavy mix of jazz, highlife, mbhaqanga, Congolese rhumba, and rhythm and blues” (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 288). The album contained a mixture of both African and American musical traditions.

With his flugelhorn, cow bell, and voice, Masekela creates the sounds of a train and a miner’s drill in “Stimela.” Echoing the sounds of a coal train’s movement, Masekela sings the words “a chugging, and a puffing, and a smoking.” He also sings out high notes of “toot, toot!” for the train’s whistle. Celia Wren, a reporter for The Washington Times, notes that Masekela with a pumping noise makes the sound of a “drill chopping away at rock,” and he “lets the word ‘deep’ sing out for several seconds” to suggest “the miners’ daily descent underground” (Wren 2012).

The train image in the song has both positive and negative associations. It transports migrant miners to work. The lyrics about the miners’ work, however, suggest exploitative labor practices: “sixteen hours or more a day/For almost no pay.” In addition to connection between two places, the train simultaneously symbolizes separation, since it is also a vehicle that separates miners from their families while they live in crowded hostels away from home.

In the later Amandla documentary film of 2003, Masekela has commented that the “train was South Africa’s first tragedy.” His words express the pain of exploited mineworkers, and the separation and loss of family members who sometimes never return home from work as a result of death or finding another loved one. The train, in real life, also has a connection with Masekela’s mother’s death. While in Liberia after visiting Ghana, Masekela received a telegram from his father about his mother’s death. His mother Pauline was driving her normal route to work on the day she was killed. Masekela stated: “While crossing a railroad track, her car stalled and a train hit it” (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 312). During this traumatic time, Masekela was unable to return from exile to bury his mother. This hardship caused him to become a more devoted activist against apartheid.

Besides “Stimela,” Masekela recorded with Hedzoleh Soundz the song titled “Been Such a Long Time Gone” for the I Am Not Afraid album of 1974. The lyrics “Been such a long time gone/I often try to remember how it was” suggest the pain of exile, feelings of displacement, the diasporic consciousness of wanting to return to one’s roots (Africa), and the singer’s desire to prevent memories of the homeland from fading. Besides English, Masekela speaks eight languages. He experienced homesickness during his time in New York. In his autobiography, Masekela wrote that he often went to Central Park and talked to himself in different languages from his homeland. One day when Masekela talked “township slang” with “hands waving, torso angling to get the point just right,” a group of people in the park thought he was crazy and asked a policeman to intervene. When stopped by the policeman, Masekela replied that he was from South Africa and was “pretending to be conversing” with “buddies back home” (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 147). This was Masekela’s way to cope with displacement.

While in exile from 1960 to 1990, Masekela frequently wished to return home. Because of his outspoken nature and activism, Masekela was advised not to return to South Africa by his sister Barbara and his parents. If Masekela returned home, he would perhaps be arrested. Apartheid Security Branch policemen were at his parents’ home looking for him after he left the country. Anyone who criticized the apartheid regime could be silenced, arrested, and detained indefinitely under the Suppression of Communism Act regardless of whether or not they had Communist beliefs. In addition, singer and activist Harry Belafonte convinced Masekela that he would become a mere statistic at home in the anti-apartheid movement. Belafonte told Masekela that he would receive more publicity and have a greater impact on the freedom struggle by protesting through music while living abroad.

Turning back to “Been Such a Long Time Gone,” several African images emerge in the song including the marketplace, caravan, Sahara, oasis, and the River Nile, as he remembers his homeland. The lyric “Been such a long time gone, I’ve got to cross over” suggests freedom of crossing borders, a reconnection, traveling, mobility, and a metaphorical united rather than fragmented self, which is torn between the host-land and the homeland. The image of white soldiers opening fire with their guns presents a stark contrast to the natural images of the hot sun and desert and suggests colonial rule and oppression. At the song’s ending, the tempo becomes faster, which suggests the excitement of getting closer to home.

Masekela’s fame also increased in 1974 when he collaborated with Stewart Levine, his former roommate from the Manhattan School of Music, and singer Lloyd Price to produce the three-night music festival prior to the “Rumble in the Jungle,” a heavyweight boxing match between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman in Kinshasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) planned by boxing promoter Don King (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 275, 285). The music festival connected some African-American artists including James Brown, B. B. King, Bill Withers, and others with their roots in Africa and African musicians including Miriam Makeba and Ladysmith Black Mambazo (Masekela 283, 285). A film about the concert and the boxing match brought global attention to Zaire.

In 1984, Masekela composed “Bring Him Back Home (Nelson Mandela),” which became a popular song of hope for the nation’s freedom from apartheid. Lyrics of this song came to Masekela in Botswana after he surprisingly received a card for his forty-fifth birthday from Nelson Mandela. The card was smuggled out of Pollsmoor Prison where Mandela was incarcerated at the time. Nelson Mandela (1918–2013), a fan of Hugh Masekela’s music, gave him encouragement for the mobile recording studio and music school that Masekela had founded in Botswana with Khabi Mngoma (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 338). Masekela’s father, Thomas Selema Masekela, a health inspector, told his friend Winnie Mandela about these accomplishments, and Winnie later relayed them to Nelson Mandela in prison. Also, Mr. Mbatha, the father of Masekela’s ex-wife Jabu, was Mandela’s former “schoolmate at Fort Hare University,” and, perhaps, he told Winnie as well (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 338). Masekela was so moved by the birthday wish and encouragement that he went to his piano and spontaneously sang the lyrics: “Bring back Nelson Mandela/Bring him back home to Soweto/I want to see him walking down the streets of South Africa/I want to see him walking hand in hand with Winnie Mandela.” These words relate to Soweto, the place where Nelson first saw Winnie as she waited for a bus. Soweto also refers to the Mandelas’ home at the address of 8115 Orlando West, Soweto. In addition, the lyrics suggest Masekela’s hope for Mandela’s freedom and the reunion of the man popularly called “father” of the anti-apartheid struggle with his wife Winnie.

After returning to the United States from Botswana, Masekela and his Kalahari band members (from Ghana) recorded “Bring Him Back Home” for the Tomorrow album in 1987. Although the song using Mandela’s name was banned in South Africa, it became the international anthem for the Release Mandela Campaign. The song kept Nelson Mandela’s image alive during his absence from the public gaze while he was incarcerated.

“Bring Him Back Home” became a message of hope for Nelson Mandela’s freedom when it was performed by Masekela during Paul Simon’s 1987 and 1989 Graceland tours throughout Europe and the United States. Later, the song accompanied Nelson Mandela on his world tour after his release from prison. Hugh Masekela continues to end his concerts with “Bring Him Back Home” in tribute to the revered leader of the anti-apartheid movement and former South African President.

After the Graceland tours, Hugh Masekela’s fame increased in 1989 when he participated in the musical production for the Broadway play, Sarafina, which was written and composed by Mbongeni Ngema (Masekela 346). Sarafina exposes the violence of the June 16, 1976 tragedy known as the Soweto Uprising in which approximately twenty-thousand black high-school students protested against Bantu education and the apartheid government’s decree to use Afrikaans as the language of instruction in schools rather than English or their own native languages (du Preez 2011, 163). During the actual protest, police fired at children who had been peacefully demonstrating, many of whom were injured or killed.

Another protest song related to the Soweto Uprising of 1976, “Soweto Blues,” was composed by Masekela and recorded by his ex-wife Miriam Makeba. It was banned in South Africa until 1990, the beginning of the dissolution of apartheid legislation. The song includes anti-apartheid lyrics and the words “children being shot,” suggesting pathos with the massacre of high-school students who were killed by the Security Branch Police instead of protecting them.

In 1990, after Nelson Mandela’s release from prison, and the government’s unbanning of political parties, Masekela’s sister Barbara called and told him to return home. Barbara eventually became Nelson Mandela’s “chief of staff” in charge of “managing his life during this transitional period” (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 351). After living in self-exile from 1960 to 1990, Hugh Masekela returned to his homeland during September 1990. Masekela was finally free to visit his mother’s grave and blow his horn in tribute to her (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 351).

Later, Masekela celebrated his homecoming with the song “Ikhaya Lami,” which he performed for his seventieth birthday concert titled Welcome Home to South Africa at London’s Barbican Concert Hall in 2009. Although he did not write the song, Masekela’s played the trumpet with the London Symphony Orchestra and St. Luke’s Community Choir. The words ikhaya lami in the song’s title mean “my home” in Zulu, and it is also “a song about homesickness” (www.HughMasekela.co.za). After such a long time away, it is a fitting tribute to Masekela’s birthday and his return to his country.

Clearly, Hugh Masekela’s horn and voice had a powerful impact on the freedom of South Africa’s people and the country’s transition to a democracy with the election of 1994. In his autobiography, Masekela wrote that singer Miriam Makeba encouraged him while living abroad to help the people “suffering back home in South Africa,” and she made him aware that he could bring about “changes against apartheid through music” (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 130). Despite the pain of exile for thirty years, Hugh Masekela always remembered the people from his homeland. Since his return to South Africa in 1990, Masekela has done much for his people, including the establishment of a drug rehabilitation program. On April 9, 2015, Hugh Masekela received an honorary doctorate from Rhodes University in Grahamstown for his expansive career and commitment to the music of South Africa (http://www.musicianAfrica.net/hugh-masekela).

While continuing to blow his horn of freedom, Masekela has remained a voice for the oppressed and an inspiration to the South African people. In his words:

Let the music play. (Masekela and Cheers 2004, 376)

Works Cited

du Preez, Max. 2011. The rough guide to Nelson Mandela. New York: Penguin Group.

“Hugh Masekela: The Official Site,” accessed April 3, 2017. www.HughMasekela.co.za

Kubernik, Harvey, and Kenneth Kubernik. 2011. A perfect haze: The illustrated history of the Monterey International Pop Festival. Solana Beach: Santa Monica Press LLC.

Masekela, Hugh, interview by Charlie Rose, Charlie Rose, Public Broadcasting System, 13 August 2009.

Masekela, Hugh and D. Michael Cheers. 2004. Still grazing: The musical journey of Hugh Masekela. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Musinguzi, Bamuturraki. 2012. “I always say a note is a note in any language.” Daily Nation (5 January 2012).

Poole, Shelia M. 2004. Q&A/Hugh Masekela, musician and activist: ‘Freedom is very sweet’ in S. Africa; Jazz great’s life now open book. Atlanta Journal-Constitution (26 May 2004).

Wren, Celia. 2012. In Hugh Masekela’s “Songs of Migration,” a fantastic voyage. The Washington Times. 19 October 2012.

Copyright © 2017 by Association of Graduate Liberal Studies Programs

https://www.paulsimon.com/news/hugh-masekela-1939-2018/

Hugh Masekela (1939 – 2018)

"Hugh Masekela taught me more about South

African culture and politics than anyone I ever met. A great musician

and songwriter, he was also one of the wittiest people I’ve known. I

never had a bad moment in his company."--Paul Simon

Hugh Masekela--"Bring Him Back Home" (Nelson Mandela) live

December 10, 2013

Hugh Masekela - "Bring Him Back Home (Nelson Mandela)" from Paul Simon's "Graceland - The African Concert" (Zimbabwe, 1987)

IN TRIBUTE TO THE INSPIRING AND LEGENDARY MUSICIAN, COMPOSER, ACTIVIST, ARTIST, AND TEACHER HUGH MASEKELA (1939-2018). MAY HIS MAGNIFICENT MUSIC AND SPIRIT CONTINUE TO PERVADE OUR LIVES FOREVER AND FOREVERMORE...

RIP BROTHER...

Miriam Makeba & Hugh Masekela --"Soweto Blues"--1976

(Music and Lyrics by Hugh Masekela)

Live performance from the Nelson Mandela 70th birthday tribute concert in 1988 sung by the legendary singer and activist and the former wife of Masekela, Miriam Makeba

"Soweto Blues" is a protest song written by Hugh Masekela and performed by Miriam Makeba. The song is about the Soweto uprising that occurred in June, 1976, following the decision by the apartheid government of South Africa to make Afrikaans a medium of instruction at school. The uprising was forcefully put down by the police, leading to the death of between 176 and 700 people. The song was released in 1977 as part of Masekela's album You Told Your Mama Not to Worry. The song became a staple at Makeba's live concerts, and is considered a notable example of music in the movement against apartheid.

SOWETO BLUES

(Lyrics & Music by Hugh Masekela, 1976)

The children got a letter from the master

It said: no more Xhosa, Sotho, no more Zulu

Refusing to comply they sent an answer

That's when the policemen came to the rescue

Children were flying bullets dying

The mothers screaming and crying

The fathers were working in the cities

The evening news brought out all the publicity:

Chorus: "Just a little atrocity, deep in the city"

Soweto blues

Soweto blues

Soweto blues

Soweto blues

Benikuphi ma madoda (where were the men)

Abantwana beshaywa (when the children were throwing stones)

Ngezimbokodo Mabedubula abantwana (when the children were being shot)

Benikhupi na (where were you?)

There was a full moon on the golden city

Looking at the door was the man without pity

Accusing everyone of conspiracy

Tightening the curfew charging people with walking

Yes, the border is where he was awaiting

Waiting for the children, frightened and running

A handful got away but all the others

Hurried their chain without any publicity

Chorus: "Just a little atrocity, deep in the city"

Soweto blues

Soweto blues

Soweto blues

Soweto blues

Chorus: Benikuphi ma madoda (where were the men) abantwana beshaywa (when the children were throwing stones) ngezimbokodo

Mabedubula abantwana (when the children were being shot) Benikhupi na (where were you?)

Soweto blues

Soweto blues

Soweto blues - abu yethu a mama

Soweto blues - they are killing all the children

Soweto blues - without any publicity

Soweto blues - oh, they are finishing the nation

Soweto blues - while calling it black on black

Soweto blues - but everybody knows they are behind it

Soweto Blues - without any publicity

Soweto blues - they are finishing the nation

Soweto blues - god, somebody, help!

Soweto blues - (abu yethu a mama)

Soweto blues