SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2021

VOLUME TEN NUMBER TWO

MARVIN GAYE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

JUNIUS PAUL

(July 10-16)

JAMES BRANDON LEWIS

(July 17-23)

MAZZ SWIFT

(July 24-30)

WARREN WOLF

(July 31-August 6)

VICTOR GOULD

(August 7-13)

SEAN JONES

(August 14-20)

JESSIE MONTGOMERY

(August 21-27)

KAMASI WASHINGTON

(August 28-September 3)

TERRACE MARTIN

(September 4-10)

FLORENCE PRICE

(September 11-17)

HUGH MASEKELA

(September 18-24)

ALFA MIST

(September 25-October 1)

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/09/arts/music/florence-price-arkansas-symphony-concerto.html

Welcoming a Black Female Composer Into the Canon. Finally.

In November 1943, the composer Florence Price wrote to Serge Koussevitzky, the music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, asking him to consider performing her scores.

“Unfortunately the work of a woman composer is preconceived by many to be light, froth, lacking in depth, logic and virility,” she said. “Add to that the incident of race — I have Colored blood in my veins — and you will understand some of the difficulties that confront one in such a position.”

It was her second letter to Koussevitzky; there is no evidence he ever replied to her.

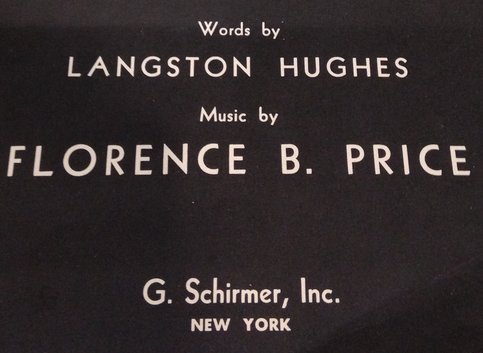

Price (1887-1953) was the first black woman to have her music played by a major American orchestra when the Chicago Symphony performed her Symphony in E Minor in 1933. She was a prominent member of the African-American intelligentsia, corresponding with W.E.B. Dubois and setting to music poems by Langston Hughes and Paul Laurence Dunbar.

But after her death, she swiftly faded into the background of a canon dominated by white men, and much of her work was thought to be lost until a trove of manuscripts was discovered in 2009, in what had been her summer home outside of Chicago. Among the pieces found were her two violin concertos, the first recording of which has been released this month by Albany Records, with Er-Gene Kahng as soloist and Ryan Cockerham conducting the Janacek Philharmonic.

“My first impression was that this was such gorgeous, accessible music,” Ms. Kahng said in an interview. She will also give a live performance of the Violin Concerto No. 2 with the Arkansas Philharmonic Orchestra in Bentonville on Feb. 17. It was dedicated to the violinist Minnie Cedargreen Jernberg, who performed it, a decade after Price’s death, at the dedication of an elementary school in Chicago named for Price, but it has never been played with an orchestra. (Full disclosure: Ms. Kahng and I are colleagues at the University of Arkansas’s Department of Music.)

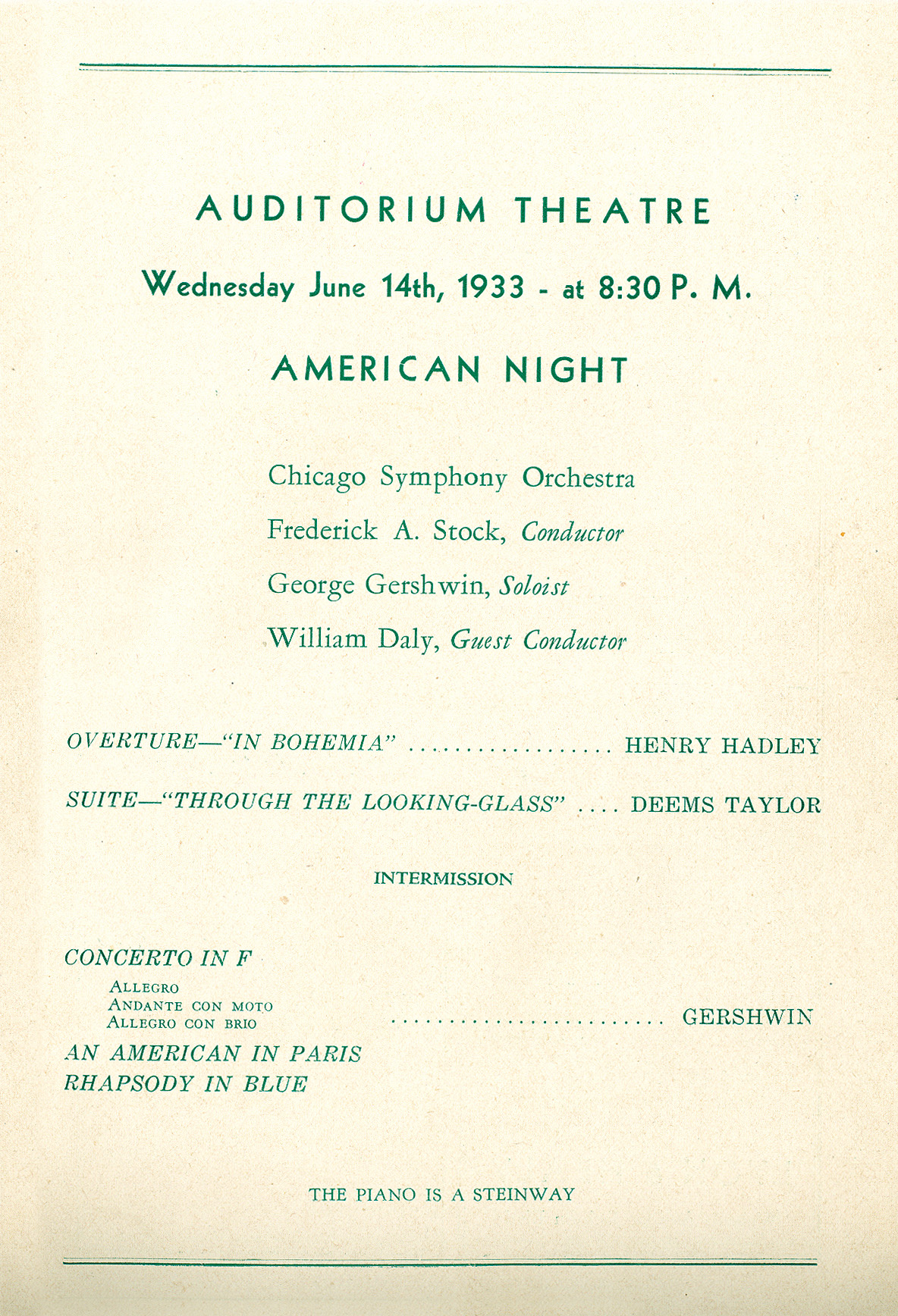

In 1893, the composer Antonin Dvorak proclaimed that an American art music should be built on African-American idioms. The musicologist Douglas Shadle has pointed out that, while white composers eagerly took up this directive — arguably culminating in George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” — many largely forgotten African-American composers did as well, and often took exception to what they saw as white appropriation.

Price was, Mr. Shadle said in an interview, “really the culmination of the African-American intellectual stream that followed in Dvorak’s footsteps.” She became well-known for her arrangements of spirituals; the great contralto Marian Anderson closed her historic 1939 concert at the Lincoln Memorial with Price’s arrangement of “My Soul’s Been Anchored in De Lord.”

But Price did not only quote folk songs. Describing her Symphony No. 3 in a 1943 letter to the conductor Frederick Schwass — her canvas began to broaden to the symphonic scale in the early 1930s — Price wrote that “it is intended to be Negroid in character and expression.”

“In it,” she went on, “no attempt, however, has been made to project Negro music solely in the purely traditional manner. None of the themes are adaptations or derivations of folk songs. The intention behind the writing of this work was a not too deliberate attempt to picture a cross-section of present-day Negro life and thought with its heritage of that which is past, paralleled or influenced by contacts of the present day.”

Marquese Carter, a doctoral student at Indiana University who specializes in Price’s work, said in an interview that she “uses the organizing material of spirituals. You may not hear direct quotation, but you will hear playing around with pentatonicism, playing around with call and response, some of these organizing principles that African-American scholars like Amiri Baraka have pointed out as indicative of black musical discourse.”

“Florence Price is a representation in music of what it means to be a black artist living within a white canon and trying to work within the classical realm,” Mr. Carter added. “How do we, through that, create a sound that sounds our culture, sounds our experience, sounds our embodied lives?”

The violin concertos offer an answer. The first, from 1939, sometimes sounds like a throwback, echoing Tchaikovsky’s famous concerto for that instrument and demonstrating Price’s thorough understanding of 19th-century harmony and orchestration. But the second, composed in a single movement in 1952 and long thought lost, is, while still highly lyrical, more concentrated and harmonically adventurous.

Clips from Price's Violin Concerto no. 1 in D Major (1939)

With Janacek Philharmonic Orchestra

Ryan Cockerham, conductor

Er-Gene Kahng, violin

Honza Košulič, audio engineer

Ostrava, Czechia

The second concerto also reflects the richly chromatic language of composers like William Schuman and Roy Harris. Mr. Shadle recently discovered that Price briefly studied with Harris in the 1940s.

“Everything she was doing was musically mainstream but at the same time idiosyncratic,” he said. “Her music has kind of a luminous quality that strikes me as her own. Our understanding of American modernism of the 1930s and 1940s is not complete without Price’s contribution.”

Writing to a conductor in the ’40s, Price described “an accumulation of hundreds of unpublished and unsubmitted manuscripts.” She continued to compose up to her death; absent her tenacity and advocacy for her own music, her legacy was incompletely preserved and has had to be reconstructed piece by piece. But she was also meticulous, and the manuscripts that were discovered nine years ago, now in the University of Arkansas library with many of her other papers, are mostly complete and easily performed.

The question is, who will perform them. Even by late last year, when challenged by a group of local musicians to diversify their programming, the Boston Symphony replied that, while it was working on the problem, audiences still wanted to hear “specifically the universal masterworks composed between 1600 and the mid-1900s.” The orchestra had programmed music by Price some months prior, but only a string quartet in a community concert, not one of the larger symphonic pieces she created as her style matured.

If American orchestras truly wish to diversify their programming — the Chicago Symphony and Philadelphia Orchestra, to name just two important examples, recently announced seasons without music by a single female composer, living or dead — Price is one of the many artists who deserves greater exposure. The Fort Smith Symphony in Arkansas is beginning a project to record her four symphonies for the Naxos label, based on editions prepared by the composer James Greeson, and in May will perform her First Symphony and (in a world premiere) the Fourth, another of the works unearthed in her summer house.

“While Price was quite proud of her accomplishments, she always felt like there was a limitation on the reception of her music, because of her race and because of her gender,” Mr. Carter said. When she tried to find a publisher for her song “Sympathy,” set to a Dunbar poem that later inspired Maya Angelou, one told her it was just a little bit too chromatic.

Mr. Carter speculates that Price identified with the caged bird in the poem. But, as we hear the soprano move into her upper register on the line “But a plea, that upward to Heaven he flings/I know why the caged bird sings,” we can also hear the full flowering Price has always deserved.

The Rediscovery of Florence Price

In 2009, Vicki and Darrell Gatwood, of St. Anne, Illinois, were preparing to renovate an abandoned house on the outskirts of town. The structure was in poor condition: vandals had ransacked it, and a fallen tree had torn a hole in the roof. In a part of the house that had remained dry, the Gatwoods made a curious discovery: piles of musical manuscripts, books, personal papers, and other documents. The name that kept appearing in the materials was that of Florence Price. The Gatwoods looked her up on the Internet, and found that she was a moderately well-known composer, based in Chicago, who had died in 1953. The dilapidated house had once been her summer home. The couple got in touch with librarians at the University of Arkansas, which already had some of Price’s papers. Archivists realized, with excitement, that the collection contained dozens of Price scores that had been thought lost. Two of these pieces, the Violin Concertos Nos. 1 and 2, have recently been recorded by the Albany label: the soloist is Er-Gene Kahng, who is based at the University of Arkansas.

The reasons for the shocking neglect of Price’s legacy are not hard to find. In a 1943 letter to the conductor Serge Koussevitzky, she introduced herself thus: “My dear Dr. Koussevitzky, To begin with I have two handicaps—those of sex and race. I am a woman; and I have some Negro blood in my veins.” She plainly saw these factors as obstacles to her career, because she then spoke of Koussevitzky “knowing the worst.” Indeed, she had a difficult time making headway in a culture that defined composers as white, male, and dead. One prominent conductor took up her cause—Frederick Stock, the German-born music director of the Chicago Symphony—but most others ignored her, Koussevitzky included. Only in the past couple of decades have Price’s major works begun to receive recordings and performances, and these are still infrequent.

The musicologist Douglas Shadle, who has documented the vagaries of Price’s career, describes her reputation as “spectral.” She is widely cited as one of the first African-American classical composers to win national attention, and she was unquestionably the first black woman to be so recognized. Yet she is mentioned more often than she is heard. Shadle points out that the classical canon is rooted in “conscious selection performed by individuals in positions of power.” Not only did Price fail to enter the canon; a large quantity of her music came perilously close to obliteration. That run-down house in St. Anne is a potent symbol of how a country can forget its cultural history.

Price was born in 1887, in Little Rock, Arkansas, and grew up in a middle-class household. She returned home after attending the New England Conservatory, one of the few conservatories that admitted African-Americans at the time. Her early adulthood was devoted largely to teaching and to raising a family. Life in Arkansas was oppressive; lynchings were routine. In 1927, Price moved with her family to Chicago, where her horizons began to expand. She divorced her husband, who had become abusive, and struck out on her own. Until then, her compositional output had consisted mostly of songs, short pieces, and music for children. She increasingly essayed larger symphonic and concerto forms, winning support from Stock, a conductor of rare broad-mindedness.

Beginning in 1931, Price wrote or sketched a total of four symphonies. The First and the Third have been published by A-R Editions, under the scholarly guidance of the late Rae Linda Brown, and recorded by the New Black Music Repertory Ensemble and the Women’s Philharmonic, respectively. The Second was apparently never finished; the Fourth, whose score turned up in the St. Anne house, will receive its première by the Fort Smith Symphony, in Arkansas, in May. These works are conservative in style, adhering to the template established by Dvořák in his Ninth Symphony, the unavoidable “New World,” of 1893. Her melodies often follow the modal contour of African-American spirituals, avoiding the outré jazz touches that appear in contemporaneous scores by black and white composers alike. Yet a distinctive sensibility emerges in Price’s pervasively elegant and subtle handling of familiar idioms.

In the First Symphony, Price is still finding her way; the harmonic writing sometimes falls back on nineteenth-century clichés, such as portentous diminished-seventh chords and insistent sequences in the Tchaikovsky manner. But her orchestration is arresting; she has a tendency to contrast tutti passages with spare, luminous writing for winds, showing a special feeling for the bassoon. The slow movement of the First achieves a hypnotic stillness, as the brass section repeatedly unfurls a stately chorale alongside a varied, kaleidoscopic accompaniment that includes African drums and cathedral chimes. The Third Symphony is a bigger, brasher work: a brooding brass opening smacks of Wagner, then begins shifting between Dvořákian hoedowns and hazy whole-tone harmonies. The music has a restless, quicksilver air, seldom staying in one mood for long: the almost kooky third movement is made up of a juba dance and a habanera. (On YouTube, there’s a good performance by the Yale Symphony.)

Kahng’s new recording of the Violin Concertos, with Ryan Cockerham conducting the Janáček Philharmonic, is Price’s best outing on disk to date. Kahng plays the solo parts with lustrous tone and glistening facility. A few passages are so obviously indebted to famous Romantic concertos that one suspects Price of putting us on. The accompaniment keeps dancing around the expected, sidestepping into a bluesy progression here, a sultry dissonance there. The second concerto, which Price wrote in 1952, shortly before her death, begins with jarring chords of D major and F minor, establishing unstable harmonic terrain. The hyper-Romantic solo part now seems like a visitor from another world. This terse, beguiling piece has an autumnal quality reminiscent of the final works of Richard Strauss. It deserves to be widely heard.

The obvious objection that could be lodged against the modest Florence Price revival—Radio 3, the BBC classical station, will also participate by airing previously unheard Price works during an International Women’s Day broadcast, on March 8th—is that the composer benefits from special pleading. If she were not black and a woman, would she be played? But other hypotheticals could be asked as well. If racism and misogyny had not so profoundly defined European and American culture, would as many white male composers have prospered? Granted, the repertory of older music cannot be drastically reëngineered to reflect contemporary values. The idea is not to replace all performances of the “New World” with renditions of Price’s symphonies and concertos. But her pieces warrant more attention than they are receiving now—especially from major orchestras. The same goes for neglected figures like Amy Beach, whose “Gaelic” Symphony (1896) packs a considerable punch, or William Dawson, whose “Negro Folk Symphony” (1934) is a brilliant, idiosyncratic creation.

In progressive musicological circles these days, you hear much talk about the canon and about the bad assumptions that underpin it. Classical music, perhaps more than any other field, suffers from what the acidulous critic-composer Virgil Thomson liked to call the “masterpiece cult.” He complained about the idea of an “unbridgeable chasm between ‘great work’ and the rest of production . . . a distinction as radical as that recognized in theology between the elect and the damned.” The adulation of the master, the genius, the divinely gifted creator all too easily lapses into a cult of the white-male hero, to whom such traits are almost unthinkingly attached.

I feel some ambivalence about the anti-masterpiece line. Having grown up with the notion of musical genius, I am reluctant to let it go entirely. What I value most as a listener is the sense of a singular creative personality coalescing from anonymous sounds. I wonder whether the profile of genius could simply evolve to include a broader range of personalities and faces. But there’s no doubt that the jargon of greatness has become musty, and more than a little toxic. I recently had a social-media exchange with the Harvard-based scholar Anne Shreffler, who wrote of instilling different values in her classes. She said, “Instead of telling students it’s Great, you can say it’s worth their while: historically fascinating, well crafted, genre bending, or just listen-to-this-amazing-moment-at-the-end. Rather than a religious icon.” If we are going to treat music as a full-fledged art form—and, surprisingly often, we don’t—we need to be open to the bewildering richness of everything that has been written during the past thousand years. To reduce music history to a pageant of masters is, at bottom, lazy. We stick with the known in order to avoid the hard work of exploring the unknown.

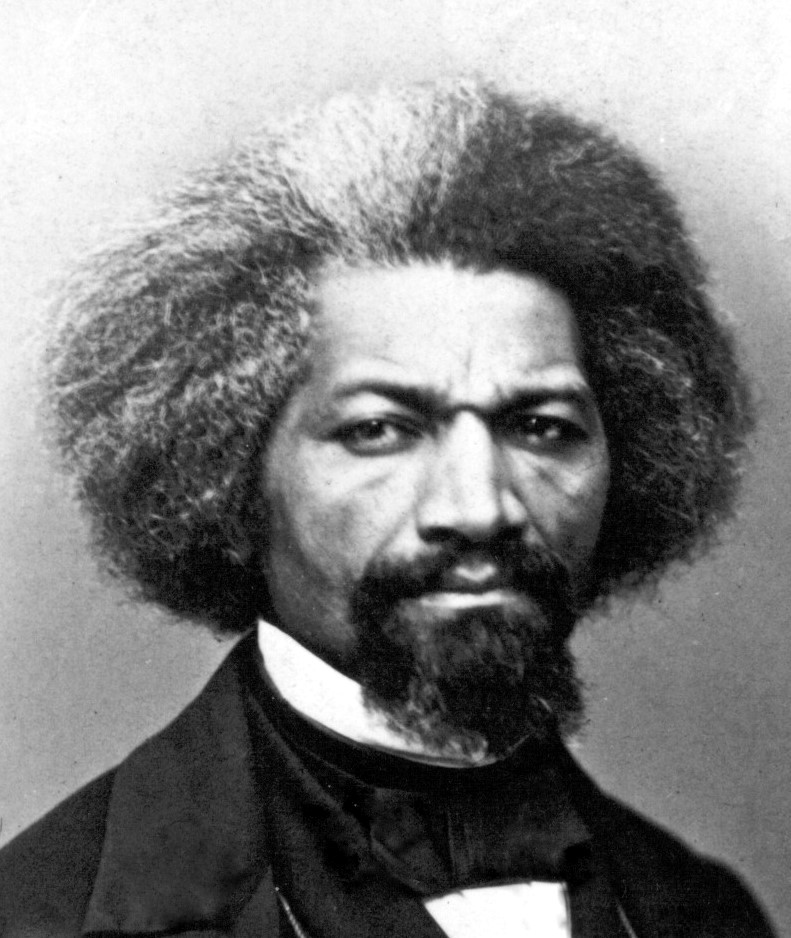

The anachronisms in Florence Price’s music are, in the end, no flaw. Listening to her, I have the uncanny sense of hearing the symphonies and operas that women and African-Americans were all but barred from writing during the Romantic heyday, when the busts on the piano were being carved. She seems to speak from an imaginary past, from an alternative history of an America that lived up to its stated ideals. Frederick Douglass, in his great speech “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?,” said, “We have to do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present and to the future.” In music, too, we can use the past to build a less imperfect world. ♦

https://florenceprice.com/biography/

BIOGRAPHY OF FLORENCE BEATRICE PRICE

Born: April 9, 1887 - Little Rock, Arkansas

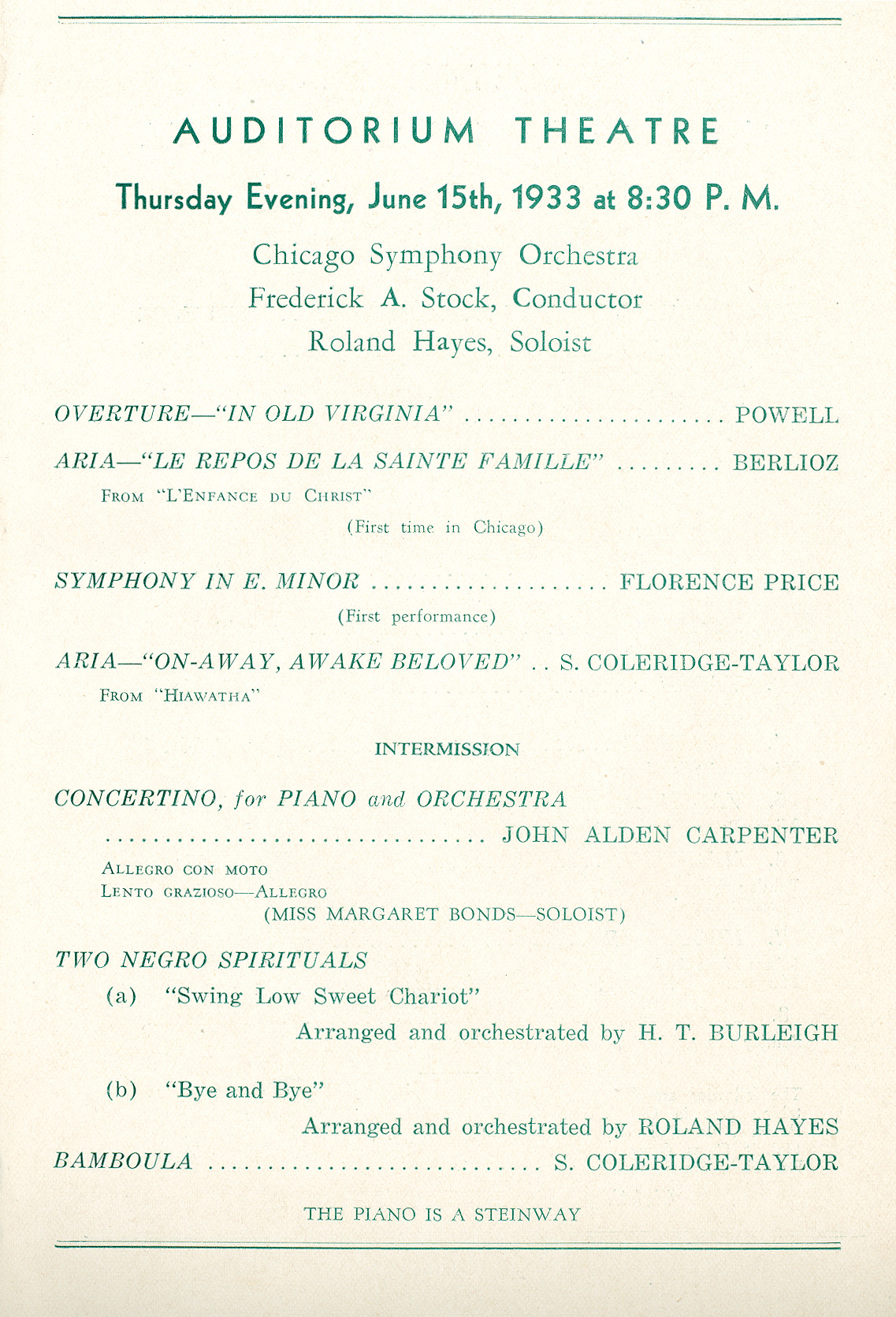

Florence Beatrice (Smith) Price became the first black female composer to have a symphony performed by a major American orchestra when Music Director Frederick Stock and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra played the world premiere of her Symphony No. 1 in E minor on June 15, 1933, on one of four concerts presented at The Auditorium Theatre from June 14 through June 17 during Chicago’s Century of Progress Exposition. The historic June 15th concert entitled “The Negro in Music” also included works by Harry T. Burleigh, Roland Hayes, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and John Alden Carpenter performed by Margaret A. Bonds, pianist and tenor Roland Hayes with the orchestra. Florence Price’s symphony had come to the attention of Stock when it won first prize in the prestigious Wanamaker Competition held the previous year.

The Chicago Daily News reported: “It is a faultless work, a work that speaks its own message with restraint and yet with passion . . . worthy of a place in the regular symphonic repertory.” Later it would become known through the archival records of Chicago Music Association (CMA) that Maude Roberts George, classical music critic for The Chicago Defender and President of CMA of which Price was a member, underwrote the cost of the June 15, 1933 concert.

A FIGHT FOR RECOGNITION

A Young Beginning

Professor Dominique-René de Lerma, distinguished American musicologist and eminent historian states “Florence Price was born in a racially-integrated community in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1887 where, at the age of four, she played in her first piano recital and her first composition was published at the age of eleven, all under her mother’s guidance.” De Lerma continues, “Her mother Florence Irene Smith Nee Gulliver, had been a school teacher in Indianapolis, Indiana before her marriage, and in Little Rock had a restaurant, sold real estate, and served as secretary of the International Loan and Trust Company. Her father, James H. Smith, was the city’s only black dentist (his patients included the state’s governor) who had moved to Little Rock in 1876.”

Price graduated as high school valedictorian at age 14 and left Little Rock in 1904 to attend the New England Conservatory and, after following her mother’s advice to present herself as being of Mexican descent, earned a bachelor of music degree in 1906, the only one of 2,000 students to pursue a double major (organ and piano performance) studying with Frederick S. Converse (piano), George Whitefield Chadwick (music theory), and Henry M. Dunham (organ). Dr. De Lerma states that it was about this time that Price “started to think seriously about composition.” Following graduation she taught for one year at the Cotton Plant-Arkadelphia Presbyterian Academy campus in northeastern Arkansas (the main campus was located in the southwestern Arkansas city of Arkadelphia) then at Little Rock’s Shorter College, and from 1910 to 1912 at Clark University in Atlanta before returning to Little Rock where she taught privately and became active in composition.

Before the Birth of Florence Price

The McCoys were free blacks from North Carolina. They were a part of a very small percentage of blacks that were free during this time. They moved north before the Civil War for hopes of better opportunities of employment and education. Uniquely, everyone in the McCoy family could read and write.

The grandfather of Florence B. Price was named William Gulliver. Mr. Gulliver was also considered a mulatto. He was born in Virginia in 1831. He moved from Virginia to Indianapolis. The Gulliver’s eventually would own multiple barbershops. With such success during this period for blacks, the Gulliver’s were considered as part of the black middle class. Many slaves who had escaped from slavery in the South found work in Indianapolis and along with free blacks, would eventually make up the small population of the black middle class.

Mr. Gulliver met the McCoy family in Indianapolis and would eventually marry their daughter, Florence Irene Gulliver in 1854. Growing up in a middle-class home, Florence Irene, the mother of Florence Beatrice, was born into a beautiful home environment with the ability for her to have piano lessons. She had an aunt who was a dressmaker and another aunt who was a teacher which for some period of time, both would live with the family which meant that Florence Irene had strong black women as mentors as she grew up. Florence Irene became a teacher and taught Elementary school which included all courses and music as well. It is suggested that she may have been the only black teacher who was teaching in an all white school. As well, Florence Irene was an amateur singer and would become an accomplished pianist.

Parents

Dr. Smith opened up his dentistry business in Chicago and became politically active in the black community. Unfortunately, the great Chicago fire of 1871 would destroy his business and home along with thousands of community members would lose everything. Over 100,000 people lost their homes and businesses. Many blacks would then move to Little Rock including Dr. Smith.

Dr. Smith married Florence Irene on November 15, 1876. They moved to Little Rock and began their family.

Growing Up in the Smith's Home

At the time of Florence Beatrice Price’s birth, April 9, 1887, the home was elegant and lavishly decorated. Dr. Smith had a very successful dental business with black and white clients. He was also very involved in the community and was politically active as well. Her mother, who was an accomplished pianist, regularly entertained guests and would often play for the guests. It was known that she owned a Ivers and Pond piano, a very expensive instrument made with exotic woods with beautiful ornate designs in the cabinet of the instrument. Click Read More to see an advertisement of the Ivers and Pond piano during the late 1800’s:

THE SMITH'S HOME

Their home had such rooms as a formal library as there were no libraries for blacks. He owned many medical books and journals which Florence Beatrice enjoyed reading. They had carpeted floors, lavishly decorated parlor, a sewing room, a kitchen, and three bedrooms with walnut and oak furniture. Read about the famous guests that stayed in the Smith’s home by clicking Read More:

Home

Guests such as Langston Hughes, seen below, would stay with the Smiths.

John Blind Boone, one of the first black concert pianists to gain a national reputation stayed with the Smiths and would become a mentor for little Florence Beatrice.

Frederick Douglass was another guest that little Florence Beatrice would meet at the tender age of two when he stayed at the Smith’s home.

At this time, there were only two black owned hotels in Little Rock during the late 1800s. Many would stay at the Smith’s home and other well to do black homes. One of the Smith’s neighbors were the Stills, the parents of William Grant Still, seen below, who grew up with Florence Beatrice.

Early Lessons and Composition

Early Composition

She had completed and published her first composition by age 11. One of her teachers was Mrs. Charlotte Andrews Stephens, who had been educated at Oberlin and had returned to Little Rock to teach public schools. She proved to be very inspiration for Little Florence Beatrice.

Secondary School Days

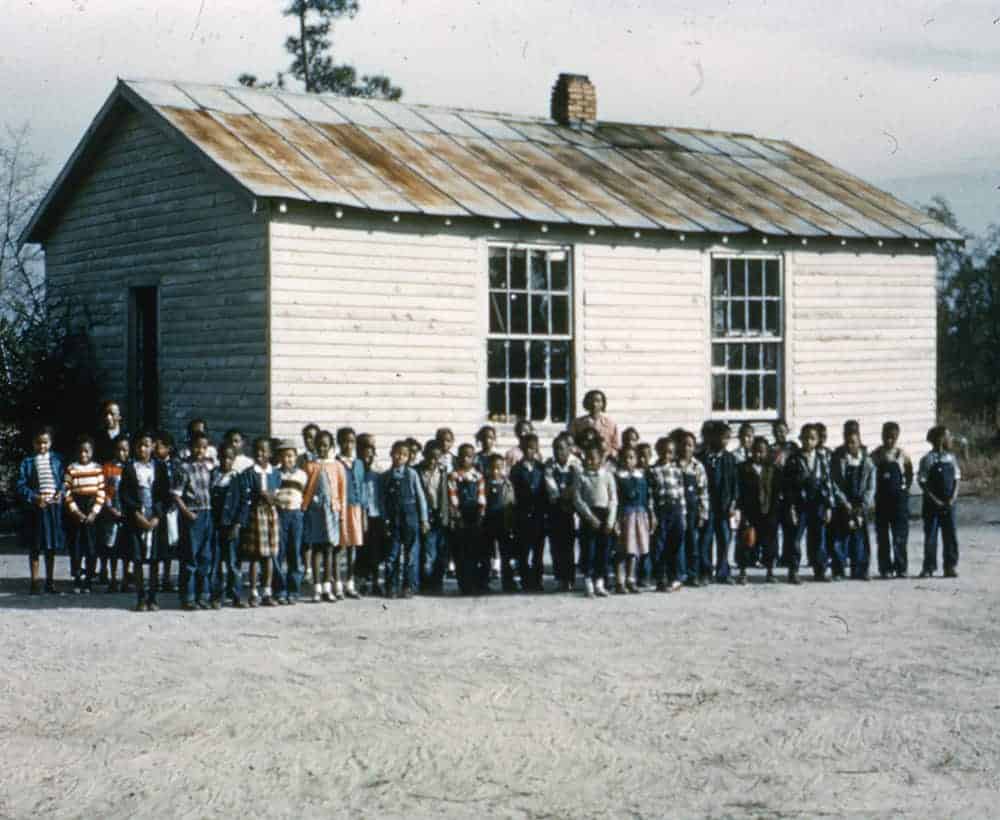

Florence Beatrice attended Union School which later became known as Capitol Hill High. Union School was at first an elementary school and a night school for blacks. Eventually it would expand to junior and senior school. Florence Beatrice enjoyed school and had such subjects as reading, spelling, writing, grammar, diction, history, geography, arithmetic, and music. Read about conditions of schools during the 1890’s for black students:

Secondary School

In 1896, racial segregation was allowed, separate but equal. (Plessy vs. Ferguson). Because most of the facilities that blacks had access to were far less funded than their white counterparts, most blacks did not have the education that would allow for them with whites and immigrants for jobs. The schools were understaffed, inferior books, but Florence Beatrice did not let that stop her. In high school, she studied Greek, Latin, algebra, history, physics, English along with painting, sewing, cooking among a host of other crafts.

An example of a one room school like the one Dr. Smith taught at is seen below:

High School

Her mother also instilled in her a sense of strength and independence. Florence Beatrice had made a decision to pursue music knowing that there only three successful American women composers who had their large-scale works performed by major symphony orchestras: Margaret Rutheven Lang, Helen Hopekirk and Amy Cheney Beach. It is quite an amazing realization that a few decades later Florence Price would be programmed along with Amy Beach as seen below:

Duo Elvire de Paiva and Pona & Joana Rolo perform works by women composers seen above.

Pursuing A Double Major At New England Conservatory

Preparing for College

NEC

Florence B. Price attended her first year of college at the New England Conservatory at the age of 16. She enrolled in two majors, one in organ and one in piano. Price studied a litany of grueling courses such as Ear Training, Dictation, Harmony, Orgran construction, the History of Organ Literature, Counterpoint, Music History Orchestral Score Reading, among a number of other subjects.

The Normal Program was a program that Price studied which would provide training for music teachers in music education. Price focused on areas in teaching and in organ performance.

Florence B. Price attended NEC from 1903-1906.

Composition at NEC

Chadwick supported women composers and had accepted them into his studio. Price would utilize melodies from spirituals as well as rhythms and harmonies. Her use of these materials were supported by Chadwick.

Compositions

Many of Prices titles of compositions depict the history of the harsh realities of life that existed for the African American that was enslaved just a mere two decades before her birth.

The Cotton Gin, from In the Land O’ Cotton Suite for solo piano is a beautiful work with gentle rhythms that expose sentiments of the difficult days of slavery. One can hear the gentle ongoing action of the cotton gin. In the last movement of the suite, Dance, one hears the Juba dance. The Juba dance arrived to the US by slaves from West Africa. The dance was usually an impromptu dance in celebration or other ceremonies calling for clapping and stomping plus the slapping of hands on the body to act as instruments. Price grew up not far from Little Rock’s fourth largest cotton farm.

In the Land O’Cotton Suite won second prize in a composition

competition sponsored by Casper Holstein, a black businessman from new

York who offered fellowships and awards along with the Rockefeller and

Rosenwald Fellowships. The award was announced in the Opportunity Magazine.

Compositions Reflecting History

Studying at NEC

Study

Price was the only student in her class to receive two degrees. And as mentioned, both of these degrees were completed within three years, not four, the normal period of time for just one degree.

Price's Class at New England Conservatory

Apartment

Ms. Smith paid for an apartment off campus so that her daughter would live by herself in a protected environment. As quoted from The Heart of a Woman by Rae Linda Brown, ” My grandmother didn’t want my mother to be a Negro so when she took her to Boston, she rented an expensive apartment with a maid and forced my mother to say her birthplace was not Little Rock but Mexico. “

During the turn of the century in America, the Negro was suffering from many challenges ranging from those that lived in the south where the practices of the Jim Crow laws were strongly enforced to the North where many were in competitions for jobs with immigrants and foreigners. The conflict within the black race was increasingly becoming a challenge between the perceived lighter and darker complected as the lighter complected Negro was assumed to be smarter because there were more indications of white descent which translated as being smarter than the darker complected Negro. This would lead to jealousy and lack of support in addition to the usual racial components as a black from the counterpart white person. Read how Ms. Smith handled this situation with her daughter, Florence Beatrice at NEC:

Newa

Music and media enables the world to hear the music of overlooked Black composer Florence Price

The world-class facilities and expertise within the University of Surrey’s Department of Music and Media (DMM), including the state-of-the-art Studio 1 and its new Steinway Model D piano, have helped to facilitate an important contribution to diversity in music.

Musicologist and pianist Dr Samantha Ege made the first full recording of all four of Florence Price’s virtuosic Fantasie Nègre showpieces at Surrey’s Performing Arts Technology Studios (PATS) on 19 and 20 December 2020.

The works were recorded for an album by the LORELT label, which was founded by Surrey alumna Odaline de la Martinez (currently an Honorary Visiting Professor in the Department of Music and Media), and is dedicated to recording work by important, neglected composers.

Born in Guildford, Dr Ege is a Junior Research Fellow at the University of Oxford, a leading interpreter and scholar of Price, and passionate about using her music as a platform to highlight composers from underrepresented backgrounds. This recording represents a mark of respect for Florence Price as well as a conscious effort to bring the issue of racism to the fore in the discipline.

Dr Ege, supported by Surrey's BMus Music Programme Director Dr Chris Wiley, will also be providing the academic texts and sleeve-notes to accompany, support and contextualise the release, to address the ethnicity and gender issues which have largely hidden the works thus far.

Dr Ege said:

“As a young pianist, discovering Florence Price made me feel visible. She belonged to a long legacy of Black composers who channelled their African heritage into classical forms. The classical mainstream must now work to realize the future that Price no doubt hoped to see, one where the concert hall welcomes Black classical artists, not only posthumously.”

Professor Tony Myatt, Head of Department of Music and Media, said:

“We are passionate about engaging with solutions to some of the long-standing and systemic race issues in music. I hope that exposing the much overlooked, yet beautifully crafted compositions of Florence Price to wider contemporary audiences might go some way to redress the historical oversight of the wonderful talents and music created by Black women composers of the twentieth century.”

The recording will be released on the 13 April 2021. It is also supported by the Ambache Charitable Trust.

Who was Florence Price?

Florence Price (1887-1953) was an African-American composer born in Arkansas. Having been taught to play by her mother, Price graduated from the New England Conservatory aged 19 with two degrees in piano teaching and organ performance. She is best known for her Symphony No. 1 in E minor, which, when it was performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1933, made her the first African-American woman to have her music presented by a major American orchestra.

The systemic and violent racism of early twentieth-century USA society shaped her personal, professional and academic life. Mindful of the ways in which her Black identity would hold her progress back, as a student she presented herself as Mexican. Later, race riots and routine lynchings forced Price and her family to move to Chicago’s South Side. There, however, she found a vibrant community of African American musicians, composers, critics, and sponsors – including a number of women – participating in what would later become known as the Black Chicago Renaissance.

Her

compositions, which number more than 300, are characterised by their

blend of European Romantic idioms and those drawn from African-American

traditional music including call-and-response procedures, use of the

pentatonic scale, and allusions to spirituals.

Black Composers Matter : Florence Beatrice Price

Florence Beatrice Price

(April 9, 1877 – June 3, 1953)

Florence Beatrice Price (nee Smith) was born in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1887. Her father was a dentist and her mother was a music teacher who guided Florence’s early musical training. Price gave her first piano recital at the age of four. Upon graduating from high school (as valedictorian, at the age of fourteen!), Price enrolled at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, Massachusetts. She graduated from the NEC in 1906 with a Bachelor of Music degree in organ and piano performance.

She returned to Arkansas, where she taught briefly before moving to Atlanta, Georgia, in 1910. There she became the head of the music department of Clark Atlanta University. In 1912, she married Thomas J. Price, a lawyer. She moved back to Little Rock, Arkansas, where he had his practice. After a series of racial incidents in Little Rock, particularly a lynching of a black man in 1927, the Price family decided to leave the south and settled in Chicago.

Florence Price as a teenager

While in Chicago, Price began a period of compositional creativity and study and was at various times enrolled at the Chicago Musical College, Chicago Teacher’s College, University of Chicago, and American Conservatory of Music, studying languages and liberal arts subjects as well as music composition and orchestration.

Financial struggles and abuse by her husband resulted in Price getting a divorce in 1931. She became a single mother to her two daughters. To make ends meet, Price wrote radio jingles, popular songs under the name “Vee Jay” and also accompanied silent films at the organ. She eventually moved in with her student, friend, and fellow composer Margaret Bonds (who was profiled earlier this semester on our blog).

Price is noted as the first African-American woman to be recognized as a symphonic composer, and the first to have a composition played by a major orchestra. In 1932, Pric submitted compositions for the Wanamaker Foundation Awards. Price won first prize with her Symphony in E minor, and third for her Piano Sonata, earning her a $500 prize. Her symphony was performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and she was catapulted into her life as a composer.

Price’s music brings together the European classical tradition in which she was trained and the haunting melodies of African American spirituals and folk tunes. Other musical influences include African American church music and European Romantic composers like Dvořák and Tchaikovsky. During the course of her life, Florence Price wrote symphonies, concertos, instrumental chamber music, music for voice and piano, works for piano, works for organ, and arrangements of spirituals.

Her best known vocal work, the setting of the Negro Spiritual, “My Soul’s Been Anchored in the Lord,” for medium voice and piano, was published by Gamble Hinged Music in 1937. Famed contralto Marian Anderson recorded the song for Victor that same year and regularly performed the song in concert. In 1949, Price published two of her spiritual arrangements, “I Am Bound for the Kingdom,” and “I’m Workin’ on My Buildin'”, and dedicated them to Anderson, who performed them on a regular basis.

When Price died in 1953, many of her concert pieces remained in manuscript and unpublished. Following her death, much of her work was overshadowed as new musical styles emerged that fit the changing tastes of modern society. Some of her work was lost, but as more African-American and female composers have gained attention for their works, so has Price. Many of her manuscripts and papers can now be found at the library of the University of Arkansas. Some items in this collection have been digitized and can be seen here: https://digitalcollections.uark.edu/digital/collection/p17212coll3.

In 2009, a substantial cache of Price’s works were found in a dilapidated house in Saint Anne, Illinois. The collection contained dozens of Price’s scores that had been thought to be lost. Here’s a 2018 piece from The New Yorker about the find: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/02/05/the-rediscovery-of-florence-price.

If you’d like to learn more about Florence Price, here are some items from the Music Library’s collection:

* The Caged Bird: The Life and Music of Florence Price (DVD)

* Symphonies Nos. 1 and 3 (Score)

* Sonata in E Minor for Piano (Score)

* Black Diamonds: Althea Waites plays music by Afro-American Composers (CD)

* Got the Saint Louis blues classical music in the jazz age / VocalEssence (Streaming audio)

Here is a recent piece about Price from NPR Music:This entry was posted in Black Composers Matter, Collection, Exhibit tie-in and tagged Black Composers, Black Composers Matter, composers, Florence B. Price, Florence Price by marmstr3. Bookmark the permalink.

https://www.theatreartlife.com/music-sound/florence-price-composer-undiscovered-work-premieres/

A forgotten work from the pioneering composer, Florence Price, has been discovered and was premiered on International Women’s Day 2021. The piece, which was previously thought to be lost, was discovered in the composer’s former home in 2009, but hadn’t been archived until recently by musicologist Samantha Ege.

About Florence Price

Florence Beatrice Price (née Smith; April 9, 1887 – June 3, 1953) was an American classical composer, pianist, organist and music teacher. Price is credited with being the first African-American woman to be recognised as a symphonic composer, and the first to have a composition played by a major orchestra.

Her mother was a music teacher who guided Florence’s early musical training. She gave her first piano performance at the age of four and had her first composition published at the age of 11. By the time she was 14, Florence had graduated as valedictorian of her class before continuing her studies at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, Massachusetts with a major in piano and organ. At the Conservatory, she studied composition and counterpoint with composers George Chadwick and Frederick Converse. While there, she wrote her first string trio and symphony. Florence graduated in 1906 with honours, and with both an artist diploma in organ and a teaching certificate.

Florence became the head of the music department of what is now Clark Atlanta University, a historically black college. In 1912, she married Thomas J. Price, a lawyer, and moved back to Little Rock, Arkansas, where he had his practice. After a series of racial incidents in Little Rock, particularly a lynching of a Black man in 1927, the Price family decided to leave. Like many Black families living in the Deep South, they moved north in the Great Migration to escape Jim Crow conditions, and settled in Chicago, a major industrial city.

In Chicago, Florence Price began a new and fulfilling period in her composition career. She studied with the leading teachers in the city, including Arthur Olaf Andersen, Carl Busch, Wesley La Violette, and Leo Sowerby, and published four pieces for piano in 1928. While in Chicago, Price was at various times enrolled at the Chicago Musical College, Chicago Teacher’s College, University of Chicago, and American Conservatory of Music, studying languages and liberal arts subjects as well as music.

Financial struggles and abuse by her husband resulted in Price getting a divorce in 1931. She became a single mother to her two daughters. To make ends meet, she worked as an organist for silent film screenings and composed songs for radio ads under a pen name. During this time, Price lived with friends. She eventually moved in with her student and friend, Margaret Bonds, also a Black pianist and composer. This friendship connected Price with writer Langston Hughes and contralto Marian Anderson, both prominent figures in the art world who aided in Price’s future success as a composer.

Together, Price and Bonds began to achieve national recognition for their compositions and performances. In 1932, both Price and Bonds submitted compositions for the Wanamaker Foundation Awards. Price won first prize with her Symphony in E minor, and third for her Piano Sonata, earning her a $500 prize. Bonds came in first place in the song category, with a song entitled Sea Ghost.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Frederick Stock, premiered the Symphony on June 15, 1933, making Price’s piece the first composition by an African-American woman to be played by a major orchestra.

A number of Price’s other orchestral works were played by the WPA Symphony Orchestra of Detroit, the Chicago Women’s Symphony, and the Women’s Symphony Orchestra of Chicago. Price wrote other extended works for orchestra, chamber works, art songs, works for violin, organ anthems, piano pieces, spiritual arrangements, four symphonies, three piano concertos, and a violin concerto.

Price made considerable use of characteristic African-American melodies and rhythms in many of her works. Her Concert Overture on Negro Spirituals, Symphony in E minor, and Negro Folksongs in Counterpoint for string quartet, all serve as excellent examples of her idiomatic work. Price was inducted into the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers in 1940 for her work as a composer. In 1949, Price published two of her spiritual arrangements, I Am Bound for the Kingdom, and I’m Workin’ on My Buildin‘, and dedicated them to Marian Anderson, who performed them on a regular basis.

Following her death from a stroke at the age of 66, much of Price’s work was overshadowed as new musical styles emerged that fit the changing tastes of modern society. Some of her work was lost, but as more African-American and female composers have gained attention for their works, so has Price. In 2001, the Women’s Philharmonic created an album of some of her work. Pianist Karen Walwyn and The New Black Repertory Ensemble performed Price’s Concerto in One Movement and Symphony in E minor in December 2011. Three settings of her work Abraham Lincoln Walks at Midnight were rediscovered in 2009 (a setting for orchestra, organ, chorus, and soloists, premiered on April 12, 2019 by the Du Bois Orchestra and Lyricora Chamber Choir in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Undiscovered works

In 2009, a substantial collection of Price’s works and papers were found in an abandoned dilapidated house on the outskirts of St. Anne, Illinois. These consisted of dozens of her scores, including her two violin concertos and her fourth symphony. As Alex Ross stated in The New Yorker in February 2018, “not only did Price fail to enter the canon; a large quantity of her music came perilously close to obliteration. That run-down house in St. Anne is a potent symbol of how a country can forget its cultural history.”

In November 2018, the New York-based firm of G. Schirmer announced that it had acquired the exclusive worldwide rights to Florence Price’s complete catalogue.

Talking to the BBC about the discovery, Samantha Ege explained that there are plans to record and publicise the many more pieces that were discovered in 2009, and that a festival dedicated to Florence Price is scheduled for later in the year. She explained,

“These pieces now need to be performed, and we need to hear them, so that we can we can appreciate Florence Price today, not just in terms of her history, but in terms of the works and the artistry that she created.

Each one takes various ideas from a Black folkloric musical tradition and blends [them] with the late 19th Century Romantic tradition. The first Fantasy Nègre is based on a spiritual, Please Don’t Let This Harvest Pass… and I think of each one as different chapters in a very elaborate novel.

Even though they were never published during her lifetime, she wrote them down and noted that they were some of her most worthy compositions, and so it’s really moving to be able to bring that together and perform them together.”

Fantasie Nègre No.3 in F Minor by Florence Price performed by Samantha Ege

Revisiting The Pioneering Composer Florence Price

Florence Price was the first African-American woman to have her music performed by a major symphony orchestra.

In 1933, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra gave the world premiere of Symphony No. 1 by a then little-known composer named Florence Price. The performance marked the first time a major orchestra played music by an African-American woman.

Price's First Symphony, along with her Fourth, has just been released on an album featuring the Fort Smith Symphony, conducted by John Jeter.

Fans of Price, especially in the African-American community, may argue that her music has never really been forgotten. But some of it has been lost. Not long ago, a couple bought a fixer-upper, south of Chicago, and discovered nearly 30 boxes of manuscripts and papers. Among the discoveries in what turned out to be Price's abandoned summer home was her Fourth Symphony, composed in 1945. This world-premiere recording is another new piece of the puzzle to understanding the life and music of Price, and a particular time in America's cultural history.

Price was born in 1887 in Little Rock, Ark. Her mother gave her music lessons since none of the leading white teachers in town would take her. In 1904, Price enrolled at the New England Conservatory in Boston, one of the few music schools to accept black students at the time. After earning two diplomas, she returned to Little Rock, where she taught, got married, and began raising a family. But racial tensions were on the rise, and a downtown public lynching in 1927 triggered a move to Chicago. There, Price blossomed as a composer. Her First Symphony won a composing prize, which caught the attention of conductor Frederick Stock, who led the premiere of the piece with his Chicago Symphony Orchestra. The music is a blend of two traditions — African-American and European. The opening movement is reminiscent of Dvorak's "New World" Symphony, with its portentous sweep and lyrical melodies.

Price might be searching for her own voice in her First Symphony, but she adds distinctive touches. Cathedral chimes glisten in the serene slow movement, where a brass choir converses with delicate winds. In the third movement, African drums accompany a syncopated "Juba Dance," a folk tradition that originated in Angola and moved, with slaves, to American plantations.

Price and her music were well received in Chicago. The great contralto Marian Anderson closed her legendary 1939 Lincoln Memorial concert with a piece arranged by Price. Still, she scraped to make ends meet, writing pop tunes and accompanying silent films. In 1943, she sent a letter to Serge Koussevitzky, conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, acknowledging what she was up against. "I have two handicaps," she wrote: "I am a woman and I have some Negro blood in my veins."

But Price pushed on. Two years later, she wrote her final symphony, the newly resurrected Fourth. In the opening movement, she quotes one of the most famous spirituals, "Wade in the Water." Price adds another "Juba Dance" for the third movement, and concludes with a bustling Scherzo that alternates serious and lighthearted episodes, ending with a bang.

Florence Price was celebrated in her day. But her untimely death in 1953, and the amount of music she composed but was never heard, helped dim her reputation over the years — until now. Tucked away in those 30 recently discovered boxes are some 200 compositions, which librarians and scholars are currently poring over. Clearly, Florence Price's story is far from over.

An Unlikely Discovery and New Recording Revive the Story of Composer Florence Price

Maybe we have Antiques Roadshow to thank. Because of the cultural phenomenon of that PBS television show, many of us view anything found in an attic, basement or forgotten closet as a potential treasure. And now in the Digital Age, it’s easier than ever to quickly research and back up a hunch about the value of found items.

New finds and rediscoveries can even amend history as we know it. Composer Florence Price has been, in large part due to race and gender, a footnote in American musical history when she should have been a chapter. But an unlikely unearthing of Price papers has revived her story and brought to light music that was thought to be lost.

Florence Beatrice Smith Price (1887-1953) was born and educated in the segregated South of Little Rock, Arkansas. In 1903, she enrolled in the New England Conservatory, one of the few prestigious music schools that would admit black students at the time.

After graduation, Price returned to Arkansas, married an attorney and started a family while teaching music. But increasingly violent race relations and an abusive husband led Price to leave the South. She turned first to Harlem and then to Chicago, both of which offered better and more musical opportunities for African-Americans.

Conductor Frederick Stock and the Chicago Symphony performed her Symphony in E minor in 1933, making Price the first African-American woman composer to have a symphony performed by a major American orchestra.

Eleanor Roosevelt praised Price’s Third Symphony in her syndicated newspaper column, My Day, and Marian Anderson performed Price's arrangement of the spiritual “My Soul’s Been Anchored in the Lord” in her groundbreaking recital on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

But Serge Koussevitzky froze out Price's numerous gentle requests to consider her scores for the Boston Symphony, and recognition as a "serious" symphonic composer was elusive. She relied on publishing popular songs and short piano pieces for a steadier stream of income, and played the organ in movie theaters to supplement when money was tight.

When Price died suddenly in 1953, her unpublished manuscripts went to her daughter, who was unconnected in the music world and unable to advocate effectively for her mother’s legacy. After her daughter’s death in 1975, it seemed likely that Price’s manuscripts were lost.

Fast forward to 2009, when Vicky and Darrell Gatwood begin renovating a dilapidated, vandalized house in St. Anne, Illinois. In one part of the house, which has miraculously remained dry, they discover a stash of papers, mostly manuscripts and letters. And one name keeps appearing: Florence Price.

A quick search online reveals that they have stumbled upon the papers of a moderately well known, but extremely important, African-American composer. The house they're renovating had been Price's summer home for a time.

The rest, as they say, is history.

During their research, the Gatwoods discovered that the University of Arkansas held some of Price's papers, so they contacted librarians there. It turns out they had rescued dozens of scores that were thought to have been lost.

Just last month, Albany Records released a new recording of two of those rediscovered works. Violinist Er-Gene Kahng and the Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra offer elegant performances of Price's two violin concertos, along with conductor-composer Ryan Cockerham’s Before, It was Golden.

Classical 101 is airing the 1952 Violin Concerto No. 2 at noon Saturday, March 24. Here's a taste:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A50gEwDu6bU

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florence_Price

Florence Price

https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-56322440

A forgotten work by the pioneering composer Florence Price has been rediscovered and performed for the first time in nearly 80 years.

Price made history in 1933 when she became the first African-American woman to have a symphony performed by a major US orchestra, in Chicago.

But her work faded into obscurity after her death in 1953.

Much of it was thought to be lost, until a cache of music was found in her former summer house in Chicago in 2009.

Musicologist Samantha Ege has spent the past two years trawling through those archives to reconstruct her solo piano pieces. Among them was Fantasie Nègre No 3 in F Minor, which was long presumed to be incomplete.

'Gathering dust'

"The music just ended after two pages really abruptly," Ege told the BBC. She made it her mission to find the missing pieces in Price's archive, which is now held in the University of Arkansas.

The problem was that, while the piece starts in F minor, the second page ends in a different key - A♭ major.

Using Price's previous compositions as a template, Ege assumed the Fantasie would return to the original key in its closing passages.

"I tried to imagine where the music could go," she said. "But I didn't have a piano [in the archives] so I was really just trying to work it all out in my head."

The eureka moment came when Ege realised Price "had more to say" in the second key of A♭ major.

She quickly found pages of manuscript that seemed match the first two sheets of Fantasie Nègre No 3 just "gathering dust" in a box on a shelf.

She wasn't convinced of her breakthrough until she went home and tried the piece out on her piano.

"When I was playing through the music and it was under my fingers it just felt magical. It felt that history was coming to life," she told BBC arts correspondent Rebecca Jones.

"I sort of had chills thinking about the fact that I am hearing this music for the first time in this century."

Ege subsequently recorded the piece - the first time it has been committed to tape - for a new CD, Fantasie Nègre - The Piano Music of Florence Price.

It was released on Monday, International Women's Day, alongside recordings of Price's other Fantasies and various "sketches and snapshots" that Ege found in the archive.

"Each one takes various ideas from a black folkloric musical tradition and blends [them] with the late 19th Century Romantic tradition," she said. "The first Fantasy Nègre is based on a spiritual, Please Don't Let This Harvest Pass... and I think of each one as different chapters in a very elaborate novel.

"Even though they were never published during her lifetime, she wrote them down and noted that they were some of her most worthy compositions, and so it's really moving to be able to bring that together and perform them together."

Composer's story

Ege's work is the latest chapter in the rediscovery and reappraisal of Price's work.

She was born Florence Smith in 1887 in Little Rock, Arkansas, to a dentist father and piano teacher mother, who encouraged her to take up the instrument.

She went on to study at the New England Conservatory of Music, one of the few music schools to accept black students at the time, and earned two diplomas in piano and organ. By 1910, she was head of the music department at Clark Atlanta University in Atlanta, Georgia.

In 1912, she married Thomas J Price and they moved back to her home town - but racial tensions were on the rise and, after a public lynching in 1927, the family moved to Chicago.

When her husband struggled to find work, the couple divorced, but Price retained her married name and made ends meet by teaching piano, playing the organ for silent film screenings and writing advertising jingles under the name Vee Jay.

At the same time, she started entering composing competitions, winning several prizes. Her big break came in 1932, when her First Symphony won the orchestral category in the Wanamaker Music Composition Contest. That caught the attention of conductor Frederick Stock, who premiered the symphony with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra the following year.

Despite that success, she often struggled to get her music played in a more sexist and segregated era. It was a problem she acknowledged in a 1943 letter to the music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Serge Koussevitzky, asking him to consider performing her music.

"I have two handicaps," she wrote. "I am a woman and I have some Negro blood in my veins."

She continued to write, and her music was performed in concert halls in Detroit, Michigan, and Brooklyn, New York.

The contralto Marian Anderson also sang Price's arrangement of My Soul's Been Anchored in De Lord as the closing song of her historic concert at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington DC in 1939.

After her death in 1953, Price's music was largely overlooked by the classical music establishment, but her reputation was preserved by black musicians and newspapers, which championed her legacy.

The discovery of her archive in 2009 helped bring her music to wider audiences again, with BBC Radio 3 dedicating a five-part documentary to her story last year.

Ege said there were many more works in Price's repertoire that remain to be recorded and publicised - and with the first festival dedicated to the composer due to take place later this year, she hopes her place in the classical music canon will be maintained.

"These pieces now need to be performed, and we need to hear them, so that we can we can appreciate Florence Price today, not just in terms of her history, but in terms of the works and the artistry that she created," she said.

https://experience.cso.org/article/2865/florence-price-receives-her-moment-on-the-work

Florence Price receives her moment on the world stage

Florence Price

Few composers have experienced the kind of meteoric rediscovery that Florence Price has enjoyed in the last decade. Nearly forgotten after she died in 1953 because she was a woman and African-American, her works can be heard on some two dozen new recordings in just the past few years alone. In addition, G. Schirmer announced in November 2018 that it had acquired the international publishing rights to Price’s music, and the firm has published nearly six dozen works to date, with more on the way in 2021.

“That is the most sustained revival of public and scholarly interest in a composer since the mid-20th century rediscovered Mahler,” said Michael Cooper, professor of music at Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas. “And I think we’re looking at something that is more than a moment here. I think it has the potential to be a movement in the sense that the Bach revival became a movement in the early 19th century or the Mahler revival became a movement in the late 20th century.”

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra, which presented the premiere of Price’s Symphony No. 1 in conjunction with the World’s Fair of 1933, was scheduled to perform her 1932 orchestral suite, Ethiopia’s Shadow in America, in November, before coronavirus restrictions forced the orchestra to cancel its planned 2020-21 season. A group of Chicago Symphony musicians will perform Price’s Five American Folksongs in Counterpoint for String Quartet as part of a CSO Sessions program premiering Feb. 25.

After spending the first part of her career in Little Rock, Ark., the composer left in the late 1920s for Chicago, fleeing rising racial violence in her native city and domestic abuse at the hands of her first husband. She went on to enjoy her greatest successes in the succeeding decades, filling out a lifetime catalog of compositions that includes four symphonies, three concertos and abundant chamber music and organ works.

As part of his ongoing musicological research, Cooper discovered the few works of Price that were known in the 1980s; since then he has been a fan. “She was clearly a serious composer to be reckoned with,” he said. In 2011, on “kind of a lark,” he began compiling a list of her works and working to find where some of the missing ones were housed. “Because someone who could produce music of that quality so consistently had to have produced many, many other works, and I knew that she had a long and incredibly productive career.”

A few years later, Cooper traveled to the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, where about 70 percent of her manuscripts are held, with the mission of editing some of the works and preparing them for publication. All composers have up and down days, and he expected to find pieces that were good, some that were very good and maybe a few that were excellent but also ones that were not exactly top drawer. “What I found instead was one piece after another that was just stunning in its originality, invention, tunefulness, harmonic richness and instrumentation — everything. Even though you could tell that they all flowed from a single stream, as it were, every work was so different form every other one that I was driven to keep editing.”

When G. Schirmer acquired the publishing rights to Price’s compositions, the firm learned that Cooper had already edited a group of her works, most in 2017-18, and approached him about publishing those editions and doing more. To date, 60 of his editions (all but one previously unpublished) have been released, starting in September 2019 with the debut edition of Price’s String Quartet No. 2 in A Minor (1935). In late December, he submitted a new edition of Price’s Seven Descriptive Pieces for Piano Solo, which will likely be published later this month. Ten more of his Price editions are slated for the spring.

Many of Price’s works remain unpublished, but Cooper said he has a lead on a cache of them, which he believes contains at least three major works. But he won’t be able to confirm what is there until the lifting of coronavirus restrictions makes travel possible. “They’re actually not hard to locate,” he said of Price’s manuscripts. “They’re kind of hiding in plain sight. It’s just that no one has actually looked for them.”

One work Cooper has not yet edited and G. Schirmer has not yet published is Five American Folksongs in Counterpoint for String Quartet, so CSO musicians will be using an edition from another source. Price wrote her first string quartet in 1929, about 1½ years after moving to Chicago, and her second one came in 1935, but it went unpublished until Cooper’s edition. She didn’t return to the form until the 1940s, when she wrote Negro Folksongs for String Quartet, which consisted of Price’s takes on four spirituals and folk songs. It was performed in Chicago in 1946. Then in 1951 or slightly later, according to Cooper, she wrote what was first known as the String Quartet on Negro Themes, which consisted of adaptations of three songs, including "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot." She then added two more songs, including "Clementine," changing the name of the 20-minute work first to Five Folksongs in Counterpoint and then Five American Folksongs in Counterpoint for String Quartet. Because of the similarity of their titles, the 1940s and ’50s works are sometime confused.

On the question of why Price created instrumental versions of well-known spirituals and folk songs for string quartet, Cooper conjectures that she would have been well versed in the history of the string quartet from her extensive studies at the New England Conservatory and elsewhere. One theme running through those discussions was what Cooper described as Goethe’s notion of the form as a “conversation among four equally intelligent gentlemen.” Because counterpoint is all about the equitable interaction of all the parts, the string quartet became a natural vehicle for these undertakings. “And that’s how all of these songs are written,” he said. “Every instrument participates as an equal partner in the conversation among the four.”

At the same time, a significant aspect of Price’s music was finding ways to integrate musical genres that were traditionally segregated from one another — in this case, African-American folk songs and the string quartet. There was little or no precedent or model for such a fusion, so it provided her with a compositional challenge — one she obviously relished — to treat these songs in a contrapuntal fashion and explore the musical potential of these time-honored classics.

“That is typical of Price,” Cooper said. “In a world that worked so hard to dehumanize her and lessen her as a woman and an African-American, she was determined, not in an overcompensating way but just being honest, to show that she could do this. Almost every composition I know by her, and there are still many that we haven’t seen, appears to be something where she has an unstoppable musical imagination that is spurred by a challenge, something like what we described here, taking two things that are never ever put together and finding a way to make sense together, to integrate them.”

Florence Price: Five Folksongs in Counterpoint for String Quartet:

April 16, 2021

Plus Ça Change: Florence B. Price in the #BlackLivesMatter Era

“While more and more blacks are being driven into homelessness,” a classical music fan fumed, “Mostly Mozart is rewarded with government, corporate, and media support.” The problem? No black composers on the program—not even Mozart’s great contemporary, Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges.

We can easily imagine this critique as a sick Twitter burn from last summer, or last week. Calls to diversify classical music programs intensify regularly. But the sad truth is that many organizations are reluctant to pursue any path other than business as usual. (Others certainly aren’t.) Perhaps sadder still, the comment above dates from 1987. Mike Snell, a reader of Raoul Abdul’s music column in the New York-based Amsterdam News, wrote Abdul to eviscerate the media for not highlighting the systemic racism underpinning the lack of black representation on the concert stage.

Plus ça change.

Returning to the present: the music of one black composer, Florence B. Price, has experienced an extraordinary surge of public interest over the past year, mainly on the heels of extensive coverage of violinist Er-Gene Kahng’s world premiere recording of her two violin concertos in The New Yorker and The New York Times. Prominent U.S. orchestras, including the New Jersey Symphony, North Carolina Symphony, and Minnesota Orchestra, programmed Price’s music during their 2018–19 seasons. The Fort Smith Symphony Orchestra recently released the world premiere recording of her Fourth Symphony on Naxos Records. And more ensembles will likely take up the mantle, both in the United States and around the globe. The Chicago Symphony, for example, recently announced that it would perform Price’s Third Symphony in the 2019–20 season.

Given the longstanding historical exclusion of African American composers, Price’s sudden rise to stardom might raise a few eyebrows. Is the sudden widespread interest in Price’s music a convenient fad? Are predominantly white institutions exploiting her legacy for short-term gain—what Nancy Leong has called “racial capitalism”? These are the right questions to ask. Their skeptical slant is justified when a major trade publication can obliviously describe women composers as “in vogue.” And it would be far from the first time that white musicians bolstered their careers on the musical labor of black women, or that black women’s musical accomplishments have faced unfair scrutiny upon entering white public consciousness.

We can only speculate about how Price’s resurgent presence on the concert stage might bring about deeper structural changes over the long term. But, if we listen carefully, her unique experiences as a composer and as a black woman present us with a more immediate opportunity to name and fight racial injustice today. Mike Snell’s complaints—and those of concerned musicians before and after him—show that time has refracted these injustices to the present.

Plus ça change, indeed.

Open Our Ears

The persistence of anti-black racism in classical music spaces stems largely from the white majority’s refusal to engage meaningfully with black voices—or even to listen. In a detailed critique of the new music communities in which he has participated, composer Anthony R. Green encourages us to “trust these voices. Be critical, but respectful. Engage in exchange. Be patient. When our work is blatantly ignored, disrespected, not studied, and not programmed, our voice is all we have.” White people, even those with anti-racist sympathies, often recoil at the suggestion that they have harmed people of color and shift the discussion to defend their motivations—a phenomenon multicultural education expert Robin DiAngelo calls “white fragility.” But the fact that Green’s observations are not new simply proves the point.

Green’s critiques revolve around the classical music industry’s propensity to pigeonhole black composers as “one-trick ponies.” This dehumanization, he argues, occurs when concert organizers think about music by black composers only during Black History Month or, in more recent years, for concerts with a social justice theme. “While this is not necessarily negative,” he adds, “the injustice arises when absolute music or music with non-social themes by black composers is overlooked.” Florence Price’s daughter, Florence Robinson, expressed similar frustrations after Price died in 1953. Artists were happy to perform Price’s arrangements of Negro spirituals, but she found no advocates for her mother’s symphonic compositions.

Once a black composer finds an advocate, however, another problem is that concert organizers do not always think through the implications of poor framing. Price’s Symphony in E Minor, which Frederick Stock and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra famously premiered in June 1933, appeared on a program ostensibly devoted to celebrating black musical achievement.

Chicago Symphony Orchestra, 15 June 1933

It featured tenor Roland Hayes and pianist Margaret Bonds as soloists in addition to pieces by Price and Afro-British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. But the opening number was an overture by John Powell, an avowed anti-black eugenicist. Powell’s presence was an acute indignity for Price and the other black performers, especially since Chicago’s black newspaper, the Defender, had publicly criticized Powell earlier that year.

- John Powell, “Music and the Nation” (1923)

- Oscar E. Saffold, “How American Folk Songs Started,” Chicago Defender, 25 Feb. 1933

To make matters worse, the event occurred the night after a concert celebrating American music, which had not only neglected to include any black musicians, but highlighted George Gershwin’s symphonic jazz compositions—pieces epitomizing white appropriation and presumed “elevation” of a fundamentally black style. Were African American musicians not American? The juxtaposition is startling.

Chicago Symphony Orchestra, 14 June 1933

Critical comparisons between the two shows were inevitable. One critic wrote about both as a unit. “Gershwin,” she observed, “looks like his music,” while John Alden Carpenter (whose Concertino had appeared on the second program with Margaret Bonds as soloist) “took up the white man’s burden” for the evening. Price, in contrast, “was given to little communicative inspiration.” By what standard we’ll never know. And black musicians of the era were painfully aware of these racist gaffes and slights, as William Grant Still, a composer who had grown up with Price in Arkansas, demonstrated in scathing commentary published in the Pittsburgh Courier in 1950.

But what choice do black composers have in the matter given the racist status quo? Is saying no to a major opportunity a viable option, especially if it puts food on the table? In September 1940, a conductor in Detroit approached Price about setting up a performance of her orchestral music. He was “quite anxious to do something from your pen,” he told her, and asked for information about her orchestrations of black folk dances. Sensing the urgency of the situation, she sent him her abstract Third Symphony instead, along with a letter that has since become one her best-known artistic manifestos. Making sure he knew the character of the piece was unlike what he had requested, she added, “The other two movements—the first and the last—were meant to follow conventional lines of form and development.” The conductor had no choice but to program the piece, given few ready alternatives. But Price took a significant professional risk by not conceding to his original demands.

Price to Frederick Schwass, Florence Price Papers, Special Collections Division, University of Arkansas Mullins Library

As these episodes show, ignorant, racist framing of black music prevents black composers from fully expressing their artistic visions and hampers listeners from approaching a piece on its own terms. Unilateral concert planning carries the risk of reifying racist norms. Creating a just environment means working with composers to find a frame that shows their music at its best. And here we can take a cue from history as well—from a 1935 performance of Price’s Piano Concerto given by the Bronx Symphony Orchestra in which the evening’s featured black musicians had taken an integral role in planning.

#BlackLivesMatter and Classical Music

Following Trayvon Martin’s brutal murder in 2012, Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tomeli inaugurated the Black Lives Matter movement to publicize the precariousness of life itself for black Americans in a violently racist society—and, of course, to rectify the injustices underpinning it.[1] The halls of classical music may seem far removed from these issues, but only because they have remained predominantly white spaces. Indeed, as historian Kira Thurman has shown, classical music (even whistling it) could not protect Draylen Mason, a young bassist from Austin, Texas, from the bomber who targeted African American homes and ultimately killed him. White people must confront this stark reality, despite the luxury of being able to avoid it.

In her reflections on Mason’s death, Kira Thurman has explained that “we don’t know how to talk about” black classical musicians because “to be black and a classical musician is to be considered a contradiction.” This insight suggests that conventional writing about classical music and musicians tends to emphasize white (male) lineage and benevolence, usually at the expense of people of color. Stating one’s position in a prominent network, for example, is meant to be a signal that talent and grit, rather than race, gender, or status, led to success. Doing the work of justice will therefore entail developing a language that breaks reliance on white patriarchal norms and captures the nuance of an individual’s full humanity.

The experience of blackness cannot be reduced to violence, but I emphasize violence here since it has experienced its own series of refractions over the past several centuries—from family separation and horrific physical abuse under slavery, to lynching under Jim Crow and decades of unchecked police brutality. The pall of violence is so pervasive that many African American parents pass strategies for navigating it to their children in a family ritual known as “the talk.” And, as black feminist theorists such as Patricia Hill Collins and bell hooks have argued, black women are uniquely vulnerable.

Price was no exception, since violence had dramatically shaped both of her parents’ lives. A group of Irish bullies, for example, nearly assaulted Price’s father when he was a young man living in New York City simply for “wearing a tall silk hat” on the sidewalk. In a draft of his memoirs, Price annotated this moment as “the lynching.” Price’s mother, meanwhile, was abducted and nearly raped as a teenager in Indianapolis. Both were squarely middle-class, indicating that a relatively high socioeconomic status could not mitigate their victimization.

- Price memoir about father, Special Collections Division, University of Arkansas Libraries

- “Attempted Seduction,” Indianapolis News, 12 Aug. 1975

Conventional biographical writing about classical musicians leaves virtually no room for examining race-based experiences like these that might shape a musical career. The official biography of Price featured on the website of her current publisher, G. Schirmer, emphasizes her relationships to white institutions and teachers but elides the circumstances that brought her into contact with these individuals in the first place.