SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING, 2021

VOLUME TEN NUMBER ONE

CHARLES MINGUSFeaturing the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

JEREMY PELT

(April 17-23)

WILLIAM GRANT STILL

(April 24-30)

AMINA CLAUDINE MYERS

(May 1-7)

KARRIEM RIGGINS

(May 8-14)

ETTA JONES

(May 15-21)

YUSEF LATEEF

(May 22-28)

CHRISTIAN SANDS

(May 29—June 4)

E. J. STRICKLAND

(June 5-11)

TAJ MAHAL

(June 12-18)

COLERIDGE-TAYLOR PERKINSON

(June 19-25)

DOM FLEMONS

(June 26-July 2)

HEROES ARE GANG LEADERS

(July 3-July 9)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/taj-mahal-mn0000790604/biography

Taj Mahal

(b. May 17, 1942)

Artist Biography by Steve Huey

One of the most prominent figures in late 20th century blues, singer/multi-instrumentalist Taj Mahal played an enormous role in revitalizing and preserving traditional acoustic blues. Not content to stay within that realm, Mahal soon broadened his approach, taking a musicologist's interest in a multitude of folk and roots music from around the world -- reggae and other Caribbean folk, jazz, gospel, R&B, zydeco, various West African styles, Latin, even Hawaiian. The African-derived heritage of most of those forms allowed Mahal to explore his own ethnicity from a global perspective and to present the blues as part of a wider musical context. Yet while he dabbled in many different genres, he never strayed too far from his laid-back country blues foundation. Blues purists naturally didn't have much use for Mahal's music, and according to some of his other detractors, his multi-ethnic fusions sometimes came off as indulgent, or overly self-conscious and academic. Still, Mahal's concept was vindicated in the '90s, when a cadre of young bluesmen began to follow his lead -- both acoustic revivalists (Keb' Mo', Guy Davis) and eclectic bohemians (Corey Harris, Alvin Youngblood Hart).

Taj Mahal was born Henry St. Clair Fredericks in New York on May 17, 1942. His parents -- his father a jazz pianist/composer/arranger of Jamaican descent, his mother a schoolteacher from South Carolina who sang gospel -- moved to Springfield, Massachusetts, when he was quite young, and while growing up there, he often listened to music from around the world on his father's short-wave radio. He particularly loved the blues -- both acoustic and electric -- and early rock & rollers like Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley. While studying agriculture and animal husbandry at the University of Massachusetts, he adopted the musical alias Taj Mahal (an idea that came to him in a dream) and formed Taj Mahal & the Elektras, who played around the area during the early '60s. After graduating, Mahal moved to Los Angeles in 1964 and, after making his name on the local folk-blues scene, formed the Rising Sons with guitarist Ry Cooder. The group signed to Columbia and released one single, but the label didn't quite know what to make of their forward-looking blend of Americana, which anticipated a number of roots rock fusions that would take shape in the next few years; as such, the album they recorded sat on the shelves, unreleased until 1992.

Frustrated, Mahal left the group and wound up staying with Columbia as a solo artist. His self-titled debut was released in early 1968 and its stripped-down approach to vintage blues sounds made it unlike virtually anything else on the blues scene at the time. It came to be regarded as a classic of the '60s blues revival, as did its follow-up, Natch'l Blues. The half-electric, half-acoustic double-LP set Giant Step followed in 1969, and taken together, those three records built Mahal's reputation as an authentic yet unique modern-day bluesman, gaining wide exposure and leading to collaborations or tours with a wide variety of prominent rockers and bluesmen. During the early '70s, Mahal's musical adventurousness began to take hold; 1971's Happy Just to Be Like I Am heralded his fascination with Caribbean rhythms, and the following year's double-live set, The Real Thing, added a New Orleans-flavored tuba section to several tunes. In 1973, Mahal branched out into movie soundtrack work with his compositions for Sounder, and the following year he recorded his most reggae-heavy outing, Mo' Roots.

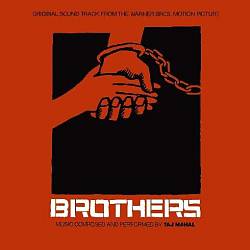

Mahal continued to record for Columbia through 1976, when he switched to Warner Bros.; he recorded three albums for that label, all in 1977 (including a soundtrack for the film Brothers). Changing musical climates, however, were decreasing interest in Mahal's work and he spent much of the '80s off record, eventually moving to Hawaii to immerse himself in another musical tradition. Mahal returned in 1987 with Taj, an album issued by Gramavision that explored this new interest; the following year, he inaugurated a string of successful, well-received children's albums with Shake Sugaree. The next few years brought a variety of side projects, including a musical score for the lost Langston Hughes/Zora Neale Hurston play Mule Bone that earned Mahal a Grammy nomination in 1991.

The same year marked Mahal's full-fledged return to regular recording and touring, kicked off with the first of a series of well-received albums on the Private Music label, Like Never Before. Follow-ups, such as Dancing the Blues (1993) and Phantom Blues (1996), drifted into more rock, pop, and R&B-flavored territory; in 1997, Mahal won a Grammy for Señor Blues. Meanwhile, he undertook a number of small-label side projects that constituted some of his most ambitious forays into world music. Released in 1995, Mumtaz Mahal teamed him with classical Indian musicians; 1998's Sacred Island was recorded with his new Hula Blues Band as he explored Hawaiian music in greater depth, and 1999's Kulanjan was a duo performance with Malian kora player Toumani Diabaté. Maestro appeared in 2008, boasting an array of all-star guests: Diabaté, Angélique Kidjo, Ziggy Marley, Los Lobos, Jack Johnson, and Ben Harper. A holiday album with the Blind Boys of Alabama, Talkin' Christmas, appeared in time for the season in 2014. In 2017, Mahal teamed with Keb' Mo' to spotlight the good-time side of the blues on TajMo.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/tajmahal

Taj Mahal

Taj Mahal - guitar, multi-instrumentalist, vocalist

Taj Mahal has spent more than 40 years exploring the roots and branches of the blues. Grounded in the acoustic pre-war blues sound but drawn to the eclectic sounds of world music, he revitalized a dying tradition and prepared the way for a new generation of blues men and women. While many African Americans shunned older musical styles during the 1960s, Mahal immersed himself in the roots of his past. “I was interested in the music because I felt something [got] lost in that transition of blacks trying to assimilate into society.” He had no intention of repeating what had come before, however, and drew deeply from the wells of the ethnic music of Africa, South America, and the Caribbean.

Taj Mahal was born Henry Saint Claire Fredericks in New York City in 1942. His father, who had emigrated from the Caribbean, wrote arrangements for Benny Goodman and played piano. His mother, Mildred Shields, had taught school in South Carolina. “Even though I have Southern and Caribbean roots, my background also crossed with indigenous European and African influences,” Mahal told Down Beat. “My parents introduced me to gospel, spiritual singing, to Ella, Sarah, Mahalia Jackson, Ray Charles.” Mahal also listened to music from around the world on his father's short-wave radio, and developed a love for blues artists like Leadbelly and Lightnin' Hopkins, and early rock-n-rollers like Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley.

Mahal's family moved when he was a young boy and he grew up in Massachusetts. Growing up in Springfield, Mass., Mahal was a rarity”a young African American who immersed himself in the study of his cultural heritage. At age 11 he witnessed the death of his father in a farming accident, but he found solace in music. When his mother remarried, he discovered his stepfather's guitar in the basement and learned to play it with a broken comb. He also took lessons from Lynnwood Perry and absorbed the radio sounds of jazz players like Illinois Jacquet and Ben Webster. Although he is primarily known as a guitarist, Mahal mastered an arsenal of instruments including piano, banjo, mandolin, and harmonica.

Mahal studied agriculture and animal husbandry at the University of Massachusetts. A dream inspired him to change his name from Fredericks, and he formed Taj Mahal and the Elektras in the early 1960s. He was lucky enough to have his ideas coincide with the '60s and the resurgence of the blues. He attended the Newport Folk Festival in the early 1960s to witness the folk and blues revival first hand. The opportunity to watch traditional blues players perform and meet the artists in person reinforced his decision to play acoustic guitar.

After graduating in 1964 Mahal moved to Los Angeles and formed the Rising Sons with Ry Cooder. The group signed with Columbia, but the label was unsure how to market the eclectic group. The band was unmatched on the L.A. scene, with a repertoire including electrified country blues and traditional folk tunes, although the Rising Sons released one single, the rest of the band's recorded material remained locked away in Columbia's vaults until 1992.

After the Rising Sons broke up, Mahal remained with Columbia and recorded his self-titled debut album, “Taj Mahal.” The album was a startling statement in its time and has held up remarkably well. The follow-up album, “The Natch'l Blues,” was equally well received. Mahal, however, soon revealed his penchant for going his own way, recording the half electric, half acoustic double album “Giant Step,” in 1969. Those three records built Mahal's reputation as an authentic yet unique modern-day bluesman.

Mahal continued to explore new directions in the 1970s. “Happy Just to Be Like I Am,” surveyed Caribbean rhythms, while “The Real Thing,” added New Orleans tubas. In 1973 he recorded the soundtrack for the movie “Sounder,” and the following year released “Mo' Roots,” an album heavily influenced by reggae. In 1976 Mahal left Columbia for Warner Brothers, where he recorded three albums in 1977 alone.

After remaining relatively silent through much of the 1980s, Mahal recorded the well-received “Taj,” in 1987. He then released “Shake Sugaree,” the first of several children's albums, and recorded a musical score for Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston's lost play, “Mule Bone,” for which he received a Grammy nomination.

He signed with Private Music and released “Dancing the Blues” in 1993 and “Phantom Blues,” in 1996. Mahal is a fine interpreter, breezy and light on love tunes, righteous and randy on cheatin' songs, and soulful and shouting on the dance numbers. “Phantom Blues,” also included high-profile guest appearances by guitarist Eric Clapton and singer Bonnie Raitt. In 1997 he won a Grammy for “Señor Blues.” He followed up with another Grammy for Best Contemporary Blues Album for “Shoutin' in Key: Taj Mahal and the Phantom Blues Band Live” in 2000.

Mahal's next music project grew out of his 15-year residency in Hawaii during the 1980s and 1990s. Joining with the Hula Blues Band, he recorded “Sacred Island,” in 1998, and followed it with “Taj Mahal and the Hula Blues” the same year and “Hanapepe Dream,” in 2003. This recording would also be the first of his albums to be released on his on label, Kan-Du. In 2005 he released “Taj Mahal and the Phantom Blues Band in St. Lucia.” This was followed with “Mkutano,” where he joined up with musicians from Zanzibar, displaying once again his versatility and global scope in music.

If the mixing of genres such as blues, Zydeco, gospel, and Latin music seems natural today, it is because of pioneers like Mahal. He opened up myriad possibilities for young artists who wanted to expand their musical palette beyond traditional blues. In the '90s, Guy Davis, Keb' Mo', Corey Harris, and Alvin Youngblood Hart, all flowing out of the surge in cultural consciousness that ensued as the offspring of the civil rights generation came into their own, prove Taj Mahal a pioneer.

While proud of his accomplishments, Mahal has remained more interested in pursuing current projects. He has recorded more than 25 albums and traveled throughout the world, continuing to explore new musical veins, playing as many as 200 dates a year, and releasing a steady stream of albums. Whether he's with a full band playing pop arrangements or stripped-down roots, Mahal has asserted himself as a keeper of the faith and a still vital force that continues to roam past musical boundaries.

Taj Mahal 2019

Taj Mahal doesn’t wait for permission. If a sound intrigues him, he sets out to make it. If origins mystify him, he moves to trace them. If rules get in his way, he unapologetically breaks them. To Taj, convention means nothing, but traditions are holy. He has pushed music and culture forward, all while looking lovingly back.

“I just want to be able to make the music that I’m hearing come to me––and that’s what I did,” Taj says. The 76-year-old is home in Berkeley, reflecting on six decades of music making. “When I say, ‘I did,’ I’m not coming from the ego. The music comes from somewhere. You’re just the conduit it comes through. You’re there to receive the gift.”

Taj is a towering musical figure––a legend who transcended the blues not by leaving them behind, but by revealing their magnificent scope to the world. “The blues is bigger than most people think,” he says. “You could hear Mozart play the blues. It might be more like a lament. It might be more melancholy. But I’m going to tell you: the blues is in there.”

If anyone knows where to find the blues, it’s Taj. A brilliant artist with a musicologist’s mind, he has pursued and elevated the roots of beloved sounds with boundless devotion and skill. Then, as he traced origins to the American South, the Caribbean, Africa, and elsewhere, he created entirely new sounds, over and over again. As a result, he’s not only a god to rock-and-roll icons such as Eric Clapton and the Rolling Stones, but also a hero to ambitious artists toiling in obscurity who are determined to combine sounds that have heretofore been ostracized from one another. No one is as simultaneously traditional and avant-garde.

“What inspires me most about my career is that I’ve been able to make a living playing the music that I always loved and wanted to play since the early 50s,” Mahal says. “And the fact that I still am involved in enjoying an exciting career at this point in time is truly priceless. I’m doing this the old fashioned way and it ain’t easy..”

Quantifying Taj’s significance is impossible, but people try anyway. A 2017 Grammy win for TajMo, his collaboration with Keb’ Mo’, brought his Grammy tally to three wins and 14 nominations, and underscored his undiminished relevance more than 50 years after his solo debut. Blues Hall of Fame membership, a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Americana Music Association, and other honors punctuate his résumé. He appreciates the accolades, but his motivation lies elsewhere. “It’s not a hunger, not a lust or even a thirst,” Taj says of what drives him. “It’s just more knowledge of self––to realize that almost everything is right here. We’re so used to looking outside of ourselves for things, and it’s right here.”

Taj’s exploration of music began as an exploration of self. He was born in 1942 in Harlem to musical parents––his father was a jazz pianist with Caribbean roots; mother was a gospel-singing schoolteacher from South Carolina––who cultivated an appreciation for both personal history and the arts in their son. “I was raised really conscious of my African roots,” Taj says. “So I was trying to find out: where does what we do here connect to what we left there?” In the early 1950s, his family moved to Springfield, Massachusetts––a microcosmic melting pot for immigrants from across the globe: the Caribbean, the American South, Europe, the Mediterranean, Syria, Lebanon. “Music was everywhere,” he says. “Things were different in those days. There weren’t a lot of places that African Americans had to go out to entertain themselves. So people did a lot of entertaining in their homes. Friday or Saturday night, you’d move the furniture, mop and wax the floor, and set things up so people could pop over and hear all the music.

From the beginning, Taj found the blues magnetic, even as most artists around him in the Northeast were exploring other sounds. “I could hear little strains of the blues coming through––you could feel that energy in the music that was being played,” he says. “I could also feel that energy of the blues inside myself.” Piano lessons didn’t stick––“I’d already heard what I wanted to play”––so when a blues guitarist from

North Carolina moved in next door, Taj found an early mentor and was off.

For college, Taj attended the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He graduated after studying agriculture and animal husbandry. “I knew I’d like to connect myself to something on this planet that’s meaningful,” he says. “That’s why I was interested in agriculture and music. Those were the two things that I recognized even as a very young child that people are never going to do without.”

In 1964, Taj packed up and headed west. In Los Angeles, he formed six-piece the Rising Sons with Ry Cooder. The group opened for Otis Redding, the Temptations, Martha and the Vandellas, and recorded an album, but it wasn’t released until about 30 years later. “I guess that’s when they decided, ‘Whoa. I guess this guy is real,’” Taj says, with a hint of a smirk. He’s referring to record executives––a breed for whom he has little patience. “For me, playing the old music was a refuge from all the stupid stuff that was going on,” he says, pausing for a moment to point out commercialization’s limiting effects on what was both recorded and heard.

In 1967, Taj’s self-titled debut announced the arrival of bold young bluesman. The following year ushered in two milestones: sophomore album The Natch’l Blues dropped, and Taj performed in The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus, a film featuring performances from the Stones, The Who, Marianne Faithfull, and others meant for the BBC but pulled and kept from public eyes until 1996. In 1969, full of music and only just beginning, Taj released Giant Step / De Ole Folks at Home, a massive double album that hinted at Taj’s refusal to be boxed in.

The 70s were a productive and ambitious recording period for Taj that included the Grammy-nominated soundtrack for the film Sounder. He began experimenting with global fusions and flirtations, signaling to listeners his restless intention to discover both new and old and disregard commercially imposed boundaries. In the 80s, Taj moved to Hawaii, and fell in love with sounds native to the island as he toured constantly, internationally. His gritty blues began to incorporate Latin, reggae, Caribbean, calypso, cajun, jazz, and more, all layered over a distinctly Afrocentric roots base he’d been raised to rediscover.

For Taj, the 90s were incredibly prolific. Back-to-back Grammy wins for the Best Contemporary Blues Album recognized two dynamic projects with the Phantom Blues Band: Señor Blues and Shoutin’ in Key. “I noticed that when it came to complicated pieces of blues music, they’d never get played,” Taj says. “It’s one of the reasons we put Señor Blues out––to say, ‘You guys, you know there is more that just the same old [imitates a beat] di da di di di da.’ It’s good when you believe it when you’re playing it. But just to play it as a cliche? That’s real boring. And real tiring.” Collaborations with Hawaiian, African, Indian, and other musicians helped define his decade.

Over the years, Taj had also emerged as a mind-boggling, multifaceted player. In addition to the guitar, he has become proficient on about 20 different instruments––and counting. “There weren’t an awful lot of people still playing these instruments that came from my culture,” Taj explains. “Not that they didn’t before, but nobody was playing them in the time I was. But I wanted to hear them. So I watched people play, got one, sat down, remembered the music that I was listening to, and started picking it out on the mandolin or banjo or 12-string.”

Taj didn’t slow down as he entered the 21st century. Maestro, marking the 40th anniversary of his recording career and featuring a global mix of voices ranging from Angelique Kidjo to Los Lobos to Ziggy Marley to Ben Harper, dropped in 2008. Last year, his highly anticipated collaboration with Keb’ Mo’––TajMo––netted Taj his third Grammy. Several projects are currently in the works, as Taj remains excited by fresh young voices trying new things and exhumed treasures that have been buried too long.

As Taj thinks about the dozens and dozens of albums, collaborations, live experiences, and captured sounds, he finds satisfaction in one main idea. “As long as I’m never sitting here, saying to myself, ‘You know? You had an idea 50 years ago, and you didn’t follow through,’ I’m really happy,” he says. “It doesn’t even matter that other people get to hear it. It matters that I get to hear it––that I did it.”

“Like ancient culture,” he adds, “the people are as much a part of the performance as the music. Live communication through music, oh yeah, it’s right up there with oxygen!”

Using traditional country blues as a starting place, Mahal perfumes the pot by mixing a spicy concoction of Afrocentric roots music, a blues gumbo kissed by reggae, Latin, R&B, Cajun, Caribbean rhythms, gospel, West African folk, jazz, calypso, and Hawaiian slack key. The savory dish he serves is both a satisfying and uplifting stew that actually transforms ‘singin’ the blues’ into something to be very happy about.

The Early Years

The parents of Harlem born Henry St. Claire Fredericks, Jr. (Mahal’s given name until his dreams of Gandhi, India and social tolerance inspired him to change it) came of age during the Harlem Renaissance and instilled in their son a sense of pride in his West Indian and African ancestry. Growing up in Springfield Massachusetts, Mahal’s father was a jazz pianist, composer and arranger of Caribbean descent (called “The Genius” by Ella Fitzgerald) who frequently hosted musicians from the Caribbean, Africa and the U.S. His mother was a schoolteacher and gospel singer from South Carolina. Henry Sr. had an extensive record collection and a shortwave radio that brought sounds from across the world into their home.

Back in the 1950s, Springfield was full of recent arrivals from all over the globe, allowing Mahal to understand and appreciate many world cultures. “We spoke several dialects in my house – Southern, Caribbean, African – and we heard dialects from eastern and western Europe,” he says. In addition, musicians from the Caribbean, Africa and all over the U.S. frequently visited the Fredericks home, and Mahal became even more fascinated with roots – the origins of the various forms of music he was hearing, the path they took to reach their current form, and how they influenced each other along the way. He threw himself into the study of older forms of African-American music, which the major record companies of the day largely ignored.

Mahal’s parents started him out on classical piano lessons, but he soon expanded his scope to include clarinet, trombone and harmonica and discovered his talent for singing. His stepfather (his mother remarried after Henry Sr. was killed in a tragic accident) owned a guitar and Mahal began playing it in his early teens, becoming serious when a guitarist from North Carolina moved in next door and taught him the various styles of Muddy Waters, Lightnin’ Hopkins, John Lee Hooker and Jimmy Reed and other titans of Delta and Chicago blues.

Before music became a viable option, Mahal – who first began working on a dairy farm at 16 and was a foreman by 19 – thought about pursuing a career in farming. Over the years, this ongoing passion has led to him performing regularly at Farm Aid concerts. In the early 60s, he studied agriculture (minoring in veterinary science and agronomy) at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, where he formed the popular U. Mass party band, the Elektras. After graduating, he headed west in 1964 to Los Angeles, where he formed the Rising Sons, a six-piece outfit that included guitarist Ry Cooder.

The band opened for numerous high-profile touring artists of the ‘60s, including Otis Redding, the Temptations and Martha and the Vandellas. Around this same time, Mahal also mingled with various blues legends, including Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Junior Wells, Buddy Guy, Lightnin’ Hopkins and Sleepy John Estes. He and Cooder also worked during this period with the Rolling Stones, and in 1968, he performed in the classic film “The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus.”

This diversity of musical experience served as the bedrock for Mahal’s first three recordings: Taj Mahal (1967), The Natch’l Blues (1968) and Giant Step (1969). Drawing on the eclectic sounds and styles he’d absorbed as a child and a young adult, these early albums showed signs of the musical exploration that would become Mahal’s hallmark in the years to come. In the 1970s, Mahal carved out a unique musical niche with a string of adventurous recordings, including Happy To be Just Like I Am (1971), Recycling the Blues and Other Related Stuff (1972), the GRAMMY®-nominated soundtrack to the movie Sounder (1973), Mo’ Roots (1974), Music Fuh Ya (Music Para Tu) (1977) and Evolution (The Most Recent) (1978). The type of blues he was playing in the early 70s showed an aptitude for spicing the mix with exotic flavors that kept him from being an out and out mainstream genre performer.

Mahal’s recorded output slowed somewhat during the 1980s as he toured relentlessly and immersed himself in the music and culture of his new home in Hawaii. Still, that decade saw the well-received release of Mahal in 1987, as well as the first three of his celebrated children’s albums on the Music For Little People label. He returned to a full recording and touring schedule in the 1990s, including such projects as the musical scores for the Langston Hughes/Zora Neale Hurston play Mule Bone (1991) and the movie Zebrahead (1992). Later in the decade, Mahal released a series of recordings with the Phantom Blues Band, including Dancing the Blues (1993), Phantom Blues (1996), and the two GRAMMY® winners, Señor Blues (1997) and the live Shoutin’ in Key (2000). Overall, he has been nominated for nine GRAMMY® Awards.

During this same period, Mahal continued to expand his multicultural horizons by joining Indian classical musicians on Mumtaz Mahal in 1995, and recording Sacred Island, a blend of Hawaiian music and blues, with the Hula Blues Band in 1998. Kulanjan, released in 1999, was a collaborative project with Malian kora master Toumani Diabate (the kora is a 21-string west African harp). Mahal felt that this recording embodied his musical and cultural spirit arriving full circle. He recorded a second album with the Hula Blues Band, Hanapepe Dream, in 2003, followed by the European release Zanzibar in 2005. His 2008 Heads Up International recording Maestro marked the 40th anniversary of his recording career and featured performances by Ben Harper, Jack Johnson, Angelique Kidjo, Los Lobos, Ziggy Marley and others – many of whom have been directly influenced by Mahal’s music and guidance.

“What inspires me most about my career is that I’ve been able to make a living playing the music that I always loved and wanted to play since the early 50s,” Mahal says. “And the fact that I still am involved in enjoying an exciting career at this point in time is truly priceless. I’m doing this the old fashioned way and it ain’t easy. I work it and I earn it. My relationship with my audience has been fun, with great respect going both ways! I am extremely lucky to have fans who have listened to the music I choose to play and have stayed with me for 50 years. These fans have also introduced their children, grandchildren and in some cases great-grand children to this fabulous treasure of music that I am privileged to represent. It’s very exciting, to say the least.

“Like ancient culture,” he adds, “the people are as much a part of the performance as the music. Live communication through music, oh yeah, it’s right up there with oxygen!”

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/listening-booth-taj-mahal-unsung-blues-south

Listening Booth: Taj Mahal and the Unsung Blues of the South

The blues singer and multi-instrumentalist Taj Mahal began his career in the late sixties, making albums of stark vintage sounds. He has since embraced influences from Hawaii, the Caribbean, Africa, and many other places, but his heart lies with the unheralded musicians of the Deep South. He’s long been a supporter of the Music Maker Relief Foundation, a nonprofit based in Hillsborough, North Carolina, which for the past twenty years has been helping older blues artists to continue to perform.

On August 10th, the Music Maker Blues Revue comes to Lincoln Center. The show will feature Dom Flemons, a young multi-instrumentalist best known for his work with the Carolina Chocolate Drops; Beverly (Guitar) Watkins, a hard-stomping singer and guitarist; and Ironing Board Sam, a keyboardist who, when he started out, in the fifties, propped his instrument on an ironing board. Taj Mahal spoke to me recently about the importance of the Music Maker Relief Foundation, and shared a few of his favorite tracks by artists connected to the organization.

When the foundation was formed, in the nineties, Mahal told me, “so many so-called scholars and ethnomusicologists were certain that all the Southern music of any significance or importance had been chronicled and documented and there wasn’t any more to be had. Along comes M.M.R.F. and—bang!—we got a whole new ball of wax with tons of talent and not one with a familiar name at all. Colorful names, no less, but completely unknown outside their own community, local area, or ‘drink house’ (a modern-day combo of bar, social club, check-cashing facility, and sometime dance hall, usually located in someone’s house).”

“Many of these musicians were passed up by talent scouts, or were locally successful and made recordings years ago, or were never discovered at all,” Mahal continued. “Some left home in the South and plied their musical wares and talents in the industrial cities of the North. Many, tired of the constant noise and calamity of those cities, returned back South and, as often as not, to a poverty-stricken or nearly poverty-stricken life.”

Here is Mahal’s playlist, with his notes below. (Several songs feature Mahal on instruments.)

[audio url="https://api.soundcloud.com/playlists/44320332"]

1. Cootie Stark, “High Yellow,” featuring Taj Mahal. Stark spent his whole life playing on the streets of Southern cities, tobacco towns, and hamlets. Dressed sharp, he was always pleasant! Here’s his take on the topic of a certain kind of sought-after, good-lookin’ woman that many Southern men dreamed about having in their lives.

2. Neal (Big Daddy) Pattman, “Shortnin’ Bread,” featuring Taj Mahal. I learned this old-time song from my mom when I was a child of three or four years old, and continue to hear it from so many different people and sources (mostly Southern) to this very day. Pattman drops in some brand-new verses and creates a version that I had never heard in all my years of listening and knowing this Southern classic.

3. Precious Bryant, “If You Don’t Love Me, Would You Fool Me Good.” Every time I hear Bryant’s voice, it’s as if I’ve known her forever but am hearing the song for the very first time! She just engages you on the spot.

4. Beverly (Guitar) Watkins, “Back in Business!” This lady is a flat-out musician who can duke it out onstage with the best there is—man, woman, or child prodigy. You have not seen a show until you catch Ms. Beverly in action! I’m still feeling the effects, and have some great memories of touring the country and playing onstage with her.

5. Adolphus Bell, “Child Support Blues.” This man knew what entertainment was all about. Bell could take any group of folks—indoor, outdoor, onstage, in the park, on a cruise ship, in a club, wherever—and have them rollin’ with laughter and music. No topic was taboo.

6. Eddie Tigner, “Route 66.” Now this is some real cool, smooth music! Makes you want to get out on the road in a convertible and drive ole Route 66 to L.A. again. I’ve known this song since the late forties, a Nat King Cole record my parents had and played a lot at house parties along with other great music of that era.

7. Captain Luke, “Old Black Buck,” featuring Cool John Ferguson. The absolutely amazing coffee-and-deep-molasses voice of Captain Luke and the beautifully country-picked guitar of Cool John breathe new life and nuance into this rural classic. This song is sung in many different traditions in the South, where tales of exceptional animals abound.

8. John Dee Holeman, “Mistreated Blues,” featuring Taj Mahal. John Dee hails from Louisburg, North Carolina, where my late friend and first and only guitar teacher came from. Upon meeting John Dee and playing with him for the first time, I remarked that he played just like my guitar teacher Lynwood Perry, from Louisburg. He said, “I’m from Louisburg!” We’ve been fast friends and musical pals ever since.

9. Neal (Big Daddy) Pattman, “Catfish Blues,” featuring Taj Mahal and Cootie Stark.

A Mississippi Delta classic that made its way through the South,

bluesman by bluesman, and into countless repertoires. Here Pattman gives

us a soulful reading, as if we are being pulled downstream by the big

river itself.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Music legend Taj Mahal talks music, race and the Rolling Stones

|

Taj Mahal was not yet a blues legend when the Rolling Stones first heard him live in the mid-1960s at the Whiskey A Go Go in Los Angeles. But they immediately became avid fans of his no-nonsense instrumental prowess, earthy singing and charismatic stage presence.

Such avid fans, in fact, that Mahal was the only American artist the now-legendary English band invited to perform in London as part of their 1968 concert film, “The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus.” As the recently released expanded “Circus” DVD and CD box set vividly attests, he was a standout in a lineup that also included the Stones, The Who, John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Jethro Tull, Eric Clapton and Marianne Faithfull.

Clapton would later be a guest on an album by Mahal, who may well be the only veteran blues great to earn a degree in agriculture and animal husbandry from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst before launching his musical career. The New York-born Mahal’s many other collaborators range from Miles Davis, Bonnie Raitt, Los Lobos and the Pointer Sisters to John Lee Hooker, Ziggy Marley, Ben Harper and the Stones.

“The Stones came to see us in 1965 at the Whiskey and they were all dancing and enjoying our music. They were earnest, they really loved the American artists they were learning from and they had a lot of good things to say about them. They really helped my career,” said Mahal, who headlines Saturday’s AimLoan.com San Diego Blues Festival with his acclaimed Phantom Blues Band. The full performance schedule appears below.

Now in its ninth year, the festival is a fundraiser for the Jacobs & Cushman San Diego Food Bank’s hunger-relief programs. Since debuting in 2011, the nonprofit event has raised more than $955,000 and 14 tons of food to feed individuals and families in need throughout San Diego County. (Cash donations and cans of food will be accepted Saturday at the front gate of the festival.)

Mahal, fittingly, has long been a source of rich aural nourishment, recording more than 50 albums and performing countless concerts around the world. Along the way, he has won four Grammy Awards — the most recent just last year for his duo album with Keb’ Mo’ — and received an array of Lifetime Achievement awards and honorary doctorates.

From Ry Cooder to four tubas

A tireless musical crusader for nearly 60 of his 77 years, Mahal first gained regional attention in 1964. That was when he co-founded the Rising Sons, a talent-packed L.A. band that also included fellow singer and guitarist Ry Cooder and jazz drum veteran Ed Cassidy, who later was a charter member of the genre-leaping rock band Spirit.

Mahal, who was born Henry Saint Clair Fredericks, released four solo albums between early 1968 and late 1969. While steeped in various acoustic and electric blues traditions, his artistic scope was already broad and has only become more expansive in the intervening years.

An early landmark was his superb 1971 double-live album, “The Real Thing.” It showcases the singer and multi-instrumentalist leading a nine-piece band that includes a four-man tuba section featuring Howard Johnson and Bob Stewart.

“The tuba band was interesting,” Mahal recalled. “I’d done my first five albums and the ‘Sounder’ film soundtrack. I was a young, black musician, very well-liked by the counterculture, and I was doing a different thing from other people. The guys that came over with the British Invasion bands knew well who I was. But, somehow or other, I couldn’t seem to start jump-start my career... I didn’t have the correct business acumen with management.

“Howard and Bob had a band, Substructure, that had seven tuba players, piano, bass and drums. I was like: ‘What? Let me hear this!’ I did, and I was knocked out. I was ready to jump into something different. It was clear I should do what I wanted. I didn’t want to get to a point, later in life, of saying: ‘Man, I had these ideas...’ If I hear something I like and want to work it in, that’s what I do.”

Blues, rock, folk, soul, swing, ragtime, calypso, reggae, Hawaiian and various African music styles are all part of Mahal’s creative palate. He wouldn’t have it any other way.

“I have five different bands, and each has a particular sound that I write a certain way for and then cross-reference. I’m having fun, man! I’m not waiting for anyone to tell me what to do,” Mahal said, speaking by phone from his Northern California home.

“I just hope people are excited that I’m excited about music. Maybe they are, maybe they aren’t. But they certainly show up when we play.”

That was not the case when he began performing as a teenager.

One of the few young artists of his generation to embrace rural acoustic blues in the 1960s, as well as the electrified Chicago blues style pioneered by Muddy Waters and Little Walter, Mahal initially found difficulty drawing audiences. His devotion at the time to raw, stripped-down folk-blues was an advantage, artistically, but a major impediment, commercially speaking.

“Stripped of all your possibilities, you don’t have any concept of who you are, so you don’t know what’s real when you hear it,” he said.

“Growing up, I was taught there was all this beautiful culture and that I should honor and support it. A lot of people, black people, are not raised that way. They’re raised to be negative — and older music reminds them of a time when they didn’t have control over their lives, as opposed to being able to see the beauty of the music for what it is.

“You don’t have to be religious to love great gospel music by Baptist people! I do what I want to, because I want to. Nobody can pay me to play music. They can pay me to put up with all of what I have to do in order to get to play music. But I play music for free. That’s why it sounds like it does. I’m a free man and will express myself freely through the music.”

‘The U.S. is a young country’

Like other American blues and jazz greats before him, Mahal has been embraced by audiences in Europe, Japan, Africa and South America. Those audiences often display greater respect for, and knowledge of, rootsy American music than audiences here.

“Those countries are not an experiment — the U.S. is a young country and we are experimenting and constantly evolving,” Mahal noted. “People in Europe are not insecure about who they are. They have classical music, they’re looking beyond that, and they revere what’s beyond that. Americans really don’t think deeply of their own history, which is so rich.”

There are also business factors, Mahal maintains, that hindered many blues and jazz artists in the U.S.

“There were no black-owned record companies that really knew the music business; if there were, it would have been different,” he said. “But there were white companies. And when they made all the money, they chewed all the flavor out. The black artists didn’t own anything; it was just their voices on a record. You signed a contract and the record company can sell your music as long as they want, in perpetuity. It’s just crazy.

“But it wasn’t just black people. A lot of these British Invasion bands in the first half of the 1960s — like the Stones and The Beatles — didn’t know any better, and they signed bad record contracts, too.”

In any country, Mahal reaches out to audiences by making music from the heart and by refusing to take his listeners for granted.

“You don’t play down to the people; you play up to them so that you bring people up,” he said. “People think the blues brings people down. No! It’s to lift you up, and I do so by looking down on me, in front of you. There’s plenty of hope for people. That’s why I play music.”

When: Noon to 8 p.m. Saturday; gates open at 11:30 a.m.

Where: Embarcadero Marina Park North, 400 Kettner Blvd., downtown

https://www.pressdemocrat.com/article/news/taj-mahals-world-of-music/

Taj Mahal doesn't just play world music; he embodies it. Rooted in American blues, his songs' influences range from West African to Hawaiian.

But they do have something in common: "The one thing I've always demanded of the records I've made is that they be danceable," he says on his site, www.tajblues.com.

And that's why even when Mahal plays theaters, like his show at Napa's Uptown on Sunday night, he'll have people leaping out of their seats to dance.

Born Henry St. Claire Fredericks in Harlem on May 17, 1942, Mahal grew up in Springfield, Mass.

His father, of West Indian descent, was a jazz pianist, composer and arranger; his mother a teacher and gospel singer from South Carolina.

As a boy, Mahal listened to the family's shortwave radio, captivated by music from around the world.

His father, who was called a musical "genius" by Ella Fitzgerald, was killed in a tractor accident when Mahal was 11. His mother remarried and when Mahal was about 13, he picked up his stepfather's guitar and mastered the instrument.

Mahal also learned to play banjo, trombone and harmonica, absorbing musical styles that would pour out later in his unconventional, genre-hopping songs.

But he never forgot where he came from.

"My parents grew up during the Harlem renaissance," says Mahal, in an interview for arts site Straight.com.

"I was connected with my African ancestry through their stories. My grandparents on my father's side came to this country from the Caribbean with a strong connection to Africa and no shame about it.

"As I got more involved in music one of the things that made me excited, from the time I was a child, was that clear link between our ancestors and the sounds we hear today."

A Taj Mahal show can be a journey through diverse worlds. He'll bounce from Caribbean-inflected rhythms to West African highlife, with a layover in Hawaii for some hula blues.

But Indian raga? Probably not, despite his adopted name. So where does Taj Mahal, the moniker he started using around 1960, come from?

"Dreams," Mahal says cryptically. An admirer of Gandhi, he says he dreamed of India and social tolerance. And it's probably no accident that he named himself after a pearly palace built in the name of love.

Mahal expresses his love through his singing, embracing his audiences with his ebullient voice. He greets audiences like old friends, and lots of his devoted fans have seen him many times, so the feeling is mutual. In some ways, Mahal's shows feel more like parties than concerts.

Yet Mahal, 68, wasn't always clear that he'd pursue a musical career.

After studying agriculture at the University of Massachusetts and working on a dairy farm - which he loved even though he had to rise before dawn - Mahal moved to Los Angeles to pursue music.

There he formed a band with Ry Cooder called the Rising Sons, opening for Otis Redding, the Temptations and other '60s legends.

In this early stage of his career Mahal performed with such legends as Howlin' Wolf, Lightnin' Hopkins and Muddy Waters. He's also worked with the Rolling Stones.

In 1967, Mahal released an eponymous album, his first effort under his own name, reveling in the gumbo of styles he'd absorbed as a youth.

Over the next four decades he traveled from Maui to Mali, seeking out local musicians and collaborating with them.

He's won two Grammys, his first in 1997 for "Se?r Blues," the second in 2000 for "Shoutin' in Key."

Mahal celebrated four decades of diverse music on his 2008 album "Maestro," which garnered a Grammy nomination.

"This record is danceable, it's listenable, it has lots of different rhythms," he says, though he doesn't see it as the culmination of his career.

This album, he says, is "just the beginning of another chapter, one that's going to be open to more music and more ideas. Even at the end of forty years, in many ways my music is just getting started."

Michael Shapiro writes about the arts for The Press Democrat. Contact him at shapiro@sonic.net.

Taj Mahal: His Musical Stomping Ground is the World

Read More: Taj Mahal: His Musical Stomping Ground is the World | Beartrap Summer Festival | Casper, Wyoming | https://beartrapsummerfestival.com/taj-mahal-his-musical-stomping-ground-is-the-world/?utm_source=tsmclip&utm_medium=referral

Relix 44: Taj Mahal

| |

| Play the Latest Hits on Amazon Music Unlimited (ad) | |

photo by Jay Blakesberg

Welcome to the Relix 44. To commemorate the past 44 years of our

existence, we’ve created a list of people, places and things that

inspire us today, appearing in our September 2018 issue and rolling out

on Relix.com throughout this fall. See all the articles posted so far here.

The Real Thing: Taj Mahal

Harlem-born singer, multi- instrumentalist and composer Henry Saint Clair Fredericks Jr. made a bold move in taking his unforgettable stage name from a magnificent 17th century Indian holy structure, but it was also a conscious decision to convey himself as something to behold, a true wonder. Like the original, Taj Mahal projects an image of dignity and awe even while keeping it all as real as real gets.

For more than half a century now, Taj Mahal has continued to radiate a rare authenticity in an increasingly less authentic world. Whatever he undertakes—when he sings the blues, reggae or when he delves into the music of Hawaii, the Caribbean or Africa—he throws his entire being into it, embodying its essence. From his self-titled debut album in 1968 to his Grammy-winning 2017 collaboration with disciple Keb’ Mo’—appropriately titled TajMo—Taj Mahal has always been an explorer, a pursuer of the genuine. Many other survivors of the era in which he came up have long since left their roots behind, but Taj Mahal has never tired of digging deeper at the source, never hesitating to turn down another road to investigate what lies ahead.

Wherever he has gone, the blues has never been far away—it’s at the core of who he is. Even in his earliest days, with the Rising Sons—a band that included kindred spirit Ry Cooder and should’ve but didn’t make the big time—Taj was on to something new while mining his beloved traditional American roots music. He came into his own on his first albums for Columbia, among them the gutsy, self-explanatory The Natch’l Blues from 1968, the same year he was invited to take part in the historic concert film The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus. Singing the Sleepy John Estes blues “Leavin’ Trunk” on that program, surrounded by A-level musicians, including guitarist Jesse Ed Davis, Mahal blew harp and sang and quickly found love among the rock-and-rollers craving the rawness and honesty he offered. As he found his way onto multi-bill gigs at emerging shrines like the Fillmores West and East, he soon rose from opening act to headliner.

By 1971, when he recorded a live album at the latter, The Real Thing, he’d already changed gears, performing his show with a stunning new band that included no less than four tuba players. Taj left Columbia for Warner Bros. during the second half of the decade, and other labels have come and gone, but his musical wanderlust only intensified with each passing year: Mahal habitually branched out, applying the same boundless curiosity whether he probed Indian music (1995’s Mumtaz Mahal), Malian grooves (1999’s Kulanjan, with kora player Toumani Diabaté) or gospel (2014’s Talkin’ Christmas!, with the Blind Boys of Alabama).

That he continues to find colleagues who are enthusiastic to join him in the studio is a testament to Mahal’s influence. His 2008 Maestro album features a long list of guests including Los Lobos, Ben Harper and Ziggy Marley, while the aforementioned TajMo collaboration features appearances by fellow blues mavens Bonnie Raitt, Joe Walsh, Sheila E. and others. During the past few years, he’s sat in with friends like the Stones, Eric Clapton and the Allman Brothers Band, all of whom continued to treasure his authenticity.

Taj Mahal, at age 76, remains totally committed to that quality he defined as “The Real Thing” many decades ago. Like the shrine from which he took his name, he continues to dazzle and inspire reverence.

This article originally appears in the September 2018 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe here.

https://online.berklee.edu/takenote/podcast-episode-022-taj-mahal/

Music is My Life: Episode 022

Taj Mahal on Working with Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, the Rolling Stones, and More

Emerging in the late 1960s as an enthusiast of blues and folk music, Taj Mahal has spent his career bending genres to his own signature style. His work includes moving explorations in jazz, funk, reggae, country, rock ‘n’ roll, and more. He has worked with everybody from Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters to the Rolling Stones to Bob Marley and the Wailers. His songs have been covered by Eric Clapton, the Black Keys, the Blues Brothers, Natalie Cole, and more. And like the range of his influences (those he has been influenced by, and those who he has influenced) the artists that pop up in conversation really run the gamut. Read a transcript of the interview below:

Pat Healy: What was the first instrument you picked up?

Yeah. I remember hearing an anecdote that your mom danced until she was 80, or in her 80s. Was music always around the house, and were they playing as well?

The maestro!

Yeah. I just love what he does.

It’s

interesting you talk about people passing down songs and putting their

own spins on it. When I think about your music, one of the songs that I

think is such a defining song is “Stagger Lee,” which has been with you

since the beginning, as far as I can tell.

Oh, yeah. It was

actually before I started playing music. I mean, it’s an old song, but

how I got it, I got it through kind of the R&B . . .

The Lloyd Price version?

The

Lloyd Price one, yeah. Just in the midst of one day listening to the

lyrics, I was like, “This is an older song than this. This didn’t just

happen right now.” You know, “Somebody didn’t just write this for rock

and roll, or even R&B.” But yeah. It made me always keep my ears

open, and then of course in the 60s when a lot of that music was coming

around, particularly through the university, and the university of

Massachusetts where I was going was … I realize now, if I probably had

gone to HBC, a historically Black college in the south, I probably would

have missed the music that I actually got in touch with. Yeah, because

you know, Springfield had a … Well, Springfield was a big terminal in

the Underground Railroad, and that whole area was a big abolitionist

area. They used to have a stronghold. So there was a lot going on to

bring people into society there, but nationally and for the record

industry and the music business, there was a large black population

there, or a significant one. Therefore, they were marketing to that

population. If you came with stuff, you could go

In those days with record stores, you could ask for what you knew you wanted and they could go and get it. They had distributors and they could ask for it. So it was a lot different than what it is today where whatever it is they got is what you get, you know? Also, so that kind of like put everybody in a particular lane. Unless you heard the blues beyond, say, Jimmy Rushing and maybe Count Basie, or just been into the jump blues stuff, you didn’t really hear the down home stuff except kinda closer to Jimmy Reed and Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf and those guys, late at night. There was a guy over in I think even Rochester or Buffalo, “Hound Dog” Lorenzi used to play stuff. If you was a radio kid like I was, I listened to the radio deep into the night. There was always a lot of different kinda music that was on. You’d hear music out of Chicago, hear music out of Memphis, Louisiana. As far away as New Orleans. When all the radio stations went down and it would roll up on the skip. But the thing is, the point I’m making, is that I would have been just … If I hadn’t heard music before the programming of rock and roll or R&B to people, I would have gone along with what everything was.

But

then I went to the university, and all of a sudden there was this whole

kinda folk music thing which I didn’t particularly care about in the

beginning, because it kinda was like Burl Ives and I didn’t really get

it. You know, my mom really liked Burl Ives. No disrespect for Burl.

Hey, the guy had an idea, he had a way of putting it across and he

followed through. Made records, had a career around it. You know, as you

get older, a lot of stuff that you really think about when you were

younger, you just realize that, “Boy, I was nuts.” Anyway. What was

really great was that neighbors in my neighborhood … I mean,

circumstance set itself up that [when I was] around 12, my dad was

killed. After that, my mom spent a few years really adjusting herself to

the fact that she was a housewife and a substitute schoolteacher with a

degree from South Carolina and a big family.

How many siblings did you have?

At that point, I had two brothers and two sisters. There were five of us and I’m the eldest. So here she was. She didn’t have any concept of how to handle the business. My father was from a Caribbean background and Caribbean men handle the business for the house. So anyway, a number of years later, not that many, she remarried to another man from the Caribbean. This time from Jamaica. With him unbeknownst to me came a guitar.

Then that guitar eventually got spoken about to a neighbor

that moved up from South to North Carolina, and he could play. He could

really play. And I mean, he had the natural keys to everything. He was

not a schooled musician, which is fine by me, because I kept noting that

there was a certain kind of snobbery that went along with schooled

musicians that unschooled musicians didn’t have. So anyway, he came to

North Carolina and then up the block from me was a bunch of guys that

came from Clarksdale, Mississippi. Stovall, actually, outside of

Clarksdale. On Colonel Stovall’s farm out there. So they played that

kinda John Lee Hooker, Mississippi boogie stuff, you know? Then the

inside music was like Jimmy Reed, Muddy Waters, T-Bone Walker. Both

T-Bone and B.B. [King] were, I found very hard to listen to at first

because I had been listening to a lot of jazz, which is always moving

and improvising. This was a different kinda set. So it took me a little

bit to get to that, but all along the music was there in those versions

of the blues that were there. The classic blues, the stuff that W.C.

Handy and those kind of guys wrote. But yeah, I just know that I heard

it, I felt it, we danced to it. It just was something that I never

thought it was a good idea to let go of.

Yeah. So you’re a teenager and you’re listening to all of this, but are you playing all this stuff too?

Mostly

I was playing pretty much, as far as vocally I could go anywhere. As

far as my playing was concerned, I pretty much stuck it around Jimmy

Reed and Muddy Waters. In or around there. It wasn’t until I started

going to the university that I got a chance to see some of the other

guys in the same way I learned from my next-door neighbor. I picked up

from them, and created my own stuff.

You had a different track at university, right? You were going to do farming?

Yeah. I was doing it before university. I was doing it in high school.

What finally made you commit to music?

I

was committed to music one way or another. If the farming came first

then the music would just be what I did. If the music came first,

hopefully then I’d have an opportunity to put together a farm or be

involved with it one way or another. What I was doing was like, dealing

with the fact that traditionally the music and the agriculture and the

culture and the life were inseparable, and here it tended to be

separated because of probably Western ideals, where you sit in the

audience and you are separate from the performer and the performer

performs and you wait till the end, as opposed to if you went to say, a

black gospel church, people are shouting in the audience and encouraging

the singer to do something. It’s just a different kind of aesthetic,

you know? I was always trying to impart that to an audience, say, “Hey,

you. Don’t you understand, when you get involved in this music you are a

part of the performance? And nobody’s going to tell you no!”

So you get out of school in 1960-what?

63-64.

Then I came up to Cambridge. I was going to see a lot of different

people, listening to a lot of music. I had the time to be able to do it.

I also had kind of a college R&B band at that time, called The

Electras. We played around the east coast, all the Ivy League colleges.

We went to a big northeastern mixer at Smith College. Our drummer was a

business major, and he made up some cards and passed them out. We worked

every weekend, and sometimes even during the week, while we were in

school. Did that, but all along I was really working on my guitar jobs.

Banjo and mandolin, and attempting to figure out harmonica. Came out to

the west coast with a friend of mine who knew some people out there,

knew some clubs. Most importantly, he knew Ry Cooder and he knew The Ash

Grove and McCaig’s Guitar Store. Wallichs Music City. A few other

places. Got involved when I came out to the West Coast, and started

working with him. Ry was phenomenal. I knew a lot of guys that played

guitar and they were okay, but he was just leaps and heaps ahead of

everybody.

Yeah. Had he already found success commercially by that point? He was just a young guy too, right?

Just

a young kid that … Well I mean, he had some success working with people

like Jackie DeShannon and maybe some other people. I don’t really

recall right now. In that musical pond out there, he was well-known, and

for a 17-year-old, 18-year-old kid, he was really playing the music,

you know? A lot of guys brought the notes. The thing of Ry, Ry not only

brought the notes, the melody, the notes, but he brought the body of the

music and he also was really, totally onomatopoeic about the swing and

the rhythm. I mean, he could transfer that, and a lot of guys couldn’t

do that. Didn’t even know how to. They didn’t know. I mean, they would

either speed up or slow down, or slow down and speed up. In his pace, he

was really consistent.

So he was playing with you. Who else? Was Jesse Davis playing?

No.

Jesse Davis was not in the picture. Jesse Davis didn’t start until I

started my solo career. We were, all of us, were signed to Columbia

Records as The Rising Sons as a group, and individually.

Oh wow, I didn’t know that.

Yeah.

So it was Ry Cooder, myself, Gary Marker played bass. Ed Cassidy, who

eventually became the drummer with Spirit. He was our drummer at that

time. Yeah. And Jessie Lee Kincaid, he was the other guitar player and

writer. So yeah, we were a bunch of guys that came with a lot of

information. We didn’t have a group leader or anything. We just really

had a group, and we would love to go and work with each other’s ideas,

which was a little bit difficult for the record company. I see now that

it was difficult for the record companies, because they are like …

Because these are brown hi-top shoes, and we can sell those. You know,

on the other side, they don’t understand if you’ve got anything

different than that. So the problem with them is that they didn’t have

any … They couldn’t see the future, because what we were doing was

eventually about a year and a half after they stopped with us, everybody

was doing the same thing, you know? But you know how they are, they

won’t leap in to something. They wait till it’s happening all around

them. So anyway, that and a bunch of crazy politics around the group

kinda put everybody at odds with the industry. Then we just sort of, all

of us just decided that, okay we’ve had enough. Rather than break up

our friendships and go away disgusted with one another, we just cleared

out. Then here I was, teaching harmonica and guitar and a little banjo.

But you had your solo deal, right?

Yeah,

but I didn’t really know how well that was. Finally what I did was I

went like, “You know what? You’re signed individually to Columbia. Pick

the phone up and call them. Call Clive Davis.” That’s exactly what I

did.

And he answered?

No, his secretary did.

No, his secretary did and I told her what was going on: that I was on

their label and I had some ideas and I wanted to record and I’d like to

talk to Clive Davis, Mr. Davis. She said, “Alright, well I’ll take your

number down and that’s Taj Mahal?” “Yeah, yeah, yeah.”

So you were going by Taj Mahal at that point?

I was going by Taj Mahal since 1959. So anyway, what happened then was about three hours later, phone rings and it’s Clive Davis. You know, it’s exactly like a certain 45 says: “Don’t talk to the people downstairs in the basement. Talk to the top.” Call him. He’s going to say no, or you’re going to get a message, or you won’t get no message at all. Which is the message. You know? So anyway, I told him what I wanted to do and he quickly said, “Well look. I’ll tell you what we can do here. How about we send you out some producers?” They were willing to put that kinda money in, so I don’t think they sent but the one guy out, and that turned out to be David Rubinson. I didn’t need to hear anything else. We clicked. We kinda came out of the same neighborhood in Brooklyn that my grandparents were in … he was really deeply into Latin music.

He was a wonderful person to hang with, and he kinda did me like Damon Dash did Jay-Z. He did the business, and I did the music. He just left me to the music. That was what I wanted. I knew what songs I wanted to record, and then the only thing that was difficult was I didn’t have a band. I was kinda like, sitting in with different bands. I sat in with Gandhi a few different times and this one and that one, and then I was like, helping people make demos and that kinda thing. I ran into a guy that was playing in a band with a woman named Pamela Polland. Pamela Polland, Riley Wildflower and I don’t know who was the bassist in that, but a guy named Sandy Konikoff was the drummer.

This guy named Gordon Shryock, he always had … people were making demos so they needed a harmonica player or a rhythm guitar player to make the demo. So I did a couple things with him, and then he asked me, well, what kinda music was I up to? I said, well I really liked blues a lot and I was thinking about putting some stuff together. He says, “Well you know, I think I’ve got somebody that you might really like to work with.” He said, “Now, he’s an Indian.” I said, “Well, okay. Is there a problem?” He said no. I said, “Well where can I hear this guy?” He says, “Well they’re playing up in Topanga Canyon Corral, him and a bunch of guys. Junior Markham and who was this guy? The Old Boatman I think was playing. Chuck Blackwell. A whole bunch of them had all come out from Oklahoma, behind Gary Lewis and the Playboys and Leon Russell. You know, they saw there was something happening out here and they were playing in a different band. James Burton was part of that thing. So I went up ultimately to hear him play. I just heard five notes and I knew this was the guy. You know? It’s like, first of all he wasn’t derivative. It wasn’t like, “Oh, he’s really great. He’s white and he plays like B.B. King.” No, no. I don’t need that guy. You know, “He’s white and he sounds just like Albert King.” Nope, I don’t need that guy. I’m talking about I don’t care who you are: what is your sound? Who are you? That’s who I wanted in my music, and so when I heard him play, he just … I never heard anybody play like him, you know? I mean, there hasn’t been. I mean, I think probably the closest guy tonally to him would probably be Robbie Robertson.

Robbie Robertson plays kind of understated,

where Jesse can really get out there and sing it up real loud. You know,

I mean Robbie could play that way too, but his tendency is this

wonderful, understated, beautiful tone. Then there’s another guy named

Willie Hona. He’s a Maori down in New Zealand. He’s the only other guy I

heard that had that, just had magic coming from wherever it came from.

So yeah, got hold of him and then the guy Sandy Konikoff who I mentioned

before was the drummer. He kinda grew up in I think Buffalo or

Rochester, and grew up around the real deep music that was happening at

the time. Jazz, groove, Oregon trails. All that kinda stuff. He could

play. I was listening to how he was playing behind Leaving Trunk the

other night, just listening. Just sometimes I go back and listen to the

records, just listen to the bass player. The bass player, Jimmy Thomas,

he was somebody I used to see coming in this club and playing with a lot

of, play with people … See, he was playing with … Who was he playing

with? I’m trying to think. Maybe he was playing behind Big Mama Thornton

or somebody like that. It was good, you know. I thought he should be in

there. Then Cooder came in and played rhythm guitar on most tracks.

Jesse Davis played slide. So basically, I just told them, “Be at the

studio on Monday night.” We had no rehearsal.

None?!

None! I just knew that these guys could play, and I knew that I could walk around and tell each guy what I wanted them to play, and then when we hit, it would all hit. Then I mean, that was one, two … I’d say probably about three, maybe three or four songs on there went that way. Then the other stuff went, Jesse Davis did some arranging. I would sit with him and play the song, and then he’d take his pick and put it in the cleft of his chin and give you a 20 thousand mile stare and hang out there and come back, and then he’d tell Chuck what to play, or Gilmour what to play, or I would tell Gilmour, like, in the case of a specific bass line that I wanted or rhythm that I wanted, just like “Leaving Trunk,”

I told everybody the parts I wanted to play except for Davis and Cooder. Them guys could play, whatever it was. I gave instruction to the drummer and the bass player, I wanted to play. Then we right there on the spot said, “Well how are we going to start this?” I said, “Well okay, I’ll just open it up with a harmonica.” I said, “We’ll do it this way.” Soon as I played that part, Davis knew to just set it up that way. So a lot of it was very telepathic. Because I mean, you know, oftentimes got a call: “Hey man, I got a gig and we got no singer. We need somebody who plays the harmonica. Can you come down?” Sure, come down. You know, “Okay. What key do you want to do it in? G, shuffle, one, two, three.” Then you go.

So these guys were really, just really good. Got

started there. The second record, we were a bit more … By that time, we

really had a group. It was Chuck Blackwell on drums, Gary Gilmour on

bass and Jesse Davis on guitar and me on dobro and harmonica and vocals.

The second record, we got real … it was more crafting what we did. By

the third record, the Giant Step record, we really got more

sophisticated. That was one of the things that I saw happen as the

evolution of the music, and that’s why I put the second album on there,

of all the acoustic stuff. Because I said, “This is like what raw

material sounds like, and older forms of music.” I didn’t realize how

much of a bible that was for so many people. I had no idea. It was just a

whim. Because I listened to a lot, I saw a lot of double albums

arriving in at that time. Basically double albums were like, sort of

more of what went on on the first one, then here’s some more on the

second one. Not bad, but it didn’t inform nobody with anything.

Right.

You talked a little bit before about frustrations with the record

labels. Did they go for the double album right away when you proposed

that?

Yeah. I mean, like I said, David Rubinson did the

business. Whatever it was that I wanted to do. Even when we did the

double album with the tubas and recorded it in New York at the Fillmore,

Wally Heider’s truck was there, and all the equipment plugged in, so we

made that great live record. You know, it’s like, “I dare somebody else

to make a record like that!”

So what changed after you

were getting your own production credit on the records? I mean, I don’t

hear that much of a departure in the sound.

Well, I mean basically he worked pretty much up through, you know, there’s Taj Mahal, Natch’l Blues, Giant Step, and De Ole Folks at Home, and then there was The Real Thing with the tubas. Happy Just to Be Like I Am, and then Sounder, Recycling The Blues and then Oooh So Good ‘n Blues. By then, that’s when I started being involved.

Right. And you produced, was Mo’ Roots, was that the first one you did?

One of them, yeah.

I

remember reading a story about Bob Marley coming to record and finding

that some of the tracks had already been recorded without him.

Well he came, yeah. Yeah, well the long of the story is, I knew some people. I had some people I’m really friendly with in England. When I went over in 1968 to The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus. That was Denny Cordell and his people. Rondor Music, I think it was called. There was a woman named Janet Dicker, who was a friend of mine. I think she convinced somebody to send me two copies of Catch a Fire. Maybe one copy and then another one showed up from somewhere else.

I can remember the day I got it. I opened it up, and is aid, “Wow, that looks like a cigarette lighter.” Opened it up and sure enough, it was like a cigarette lighter. Turned it over, and like I said, “Ooh, that’s a rough looking bunch of characters there. Jamaicans here, alright. Wonder what this sounds like.”

I put that thing down on there, and as soon as I heard the bass booming out of the speaker, I said, “They will never play that on AM radio!” And they never did! But anyway, Bob, Rudy became a huge fan. I mean, I’d already listened to Jamaican and Caribbean music through my family. Particularly through my stepfather. Not so much reggae, but a lot of mento and ska, and that kinda stuff, you know? So Bob and those guys had come to the United States and I was keeping my antennas up for them. I think they were on tour with Sly and The Family Stone, and Sly was pretty much full of himself in those days. He couldn’t … You know, he didn’t know who these guys were and didn’t pay any attention until he figured out that the music was actually grabbing the audience. Whoa. He threw those guys off the tour, and just left them all scattered around the Bay Area.

I found out about it, and I was like, really perturbed. I was like, “Are you serious? You mean to tell me that the music that you’re playing, you would be threatened by somebody else playing good music to your audience?” I don’t get that. The audience comes there to see you, and it also hears this group. That means your stock goes up. But he didn’t see it that way. Threw those guys off. I thought it was the worst thing I ever heard of a fellow musician. You know, doing it nationally, let alone internationally.

So I hooked those guys up, and we found kind of a kitchenette, motel kind of place where there was rooms for everybody, and helped them get settled until they could get things. You know, I guess probably get Chris Blackwell involved with them to pull them together. So you know, they were always grateful for that. Not that, no pressures, like just do stuff. Then eventually, I thought about wanting to work or have Bob involved somewhere in around, so he did. Eventually came he and Family Man [Aston Barrett], the bass player, and Skill Cole, the great soccer player and a guy named Augustus Pablo came to my house and kind of had a jam session.

That’s where he came up with the idea of “Talkin’ Blues.” At my house. You know, “Walkin’ blues, your feet are too big for your shoes.” We had a great night playing music and then I got word out to them that I was working in the studio, but by the time we got hold of him or by the time he got there, we had already been down the line because, you know, we were sticking to the schedule and here’s the time you gotta record. But he came in, he was in the studio and he listened to it. Family Man requested that they put more treble guitar tops on the bass. He was, “Put a little more tops on de bass. More tops on de bass, yes, yes. More tops on the bass.”

You’ve experimented

with so many different types of music. That’s just one example, with the

reggae, and I know your stepfather was from Jamaica. Was there any type

of music that you have … When you’re approaching a genre that is not

native to you, or that’s outside of your own experience, how do you

approach it?

Like, what you’re talking, like, what kind, when you say “genre”?

Basically like you have stuck your foot in every single genre. You’ve done folk, blues . . .

I think you’re dealing it from the record company’s perspective.

Ha ha! You may be right!

If

you deal it from culture, how are you going to bring millions of black

people into the Western civilization, in some cases mix them up, and not

in 500 years when we’ve been here and … unless you buy … The land I’m

in is the land I know. Without it, I never bought that. That’s really

clear.

I know, but I guess, how did you just, so confidently . . .

Because

they’re my cousins. They’re my cousins. They’re my relatives. You know,

it’s like, because I listen to, when they play toward our music. See,

when you’re in the Caribbean or even Africa or South America, you hear

American music. You don’t hear American music in boxes. When we’re here,

we hear the world in boxes. You know, it’s, “Oh, this is African

music.” Then, no. It’s like, that’s a real narrow box for what’s Africa,

you know?

Right.

So no. I mean, my thought

is that I’m … I mean, the whole experience of coming out of Africa into

the Western civilization just broke up family, culture, blah blah blah.

So at this point, for me, it’s just connecting the dots between family I

recognize musically. Probably the farthest out one for people to be

able to deal with has been the Hawaiian music, and that came as a result

to me being … As a kid, I would note that some music went through my

head and I didn’t feel it in my body. Some music went through my body

and I felt it in my head, in my soul, my spirit and my heart. The first

time I heard Hawaiian music was somewhere around maybe between seven and

nine years old. I was just shook to the core, how deep that music was

already in there. And I don’t even know these people. My thought then

was, “I don’t know how it’s going to happen, but someday I want to find

out why. What is it about this music and these people that reached me at

that deep level?” Because I’ve listened to a lot of music. From all

different types of sources. Some, I would sit back and let the musicians

that play that music play, because I don’t have any direct relationship

or connection to it, but most of the stuff that I’m involved with has

been, just as I say: getting connected, and familial. You know, after

having been split up in the diaspora, so . . .

Is there anything you wouldn’t try?

Oh, I mean I could jokingly make a heavy metal record.

I bet it would be awesome, though.

Rap isn’t difficult.

Yeah?

No,

not at all. Because I mean, there’s a way. There’s a way to do it. I

mean, as an elder musician I’m not against what the young kids play. A

lot of people think that they have to have an opinion about it, and we

know what we have to say about opinions. You know, I mean the thing is

to me it’s like bebop, you know? Everybody didn’t like bebop either. I