SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2021

VOLUME NINE NUMBER THREE

FARUQ Z. BEY

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

William Parker

(January 23-29)

Jason Palmer

(January 30-February 5)

Living Colour

(February 6-12)

Charles Tolliver

(February 13-19)

Henry Grimes

(February 20-26)

Marcus Strickland

(February 27-March 5)

Kendrick Scott

(March 6-March 12)

Seth Parker Woods

(March 13-19)

Kris Bowers

(March 20-26)

Ulysses Owens

(March 27-April 2)

Steve Nelson

(April 3-9)

Steve Wilson

(April 10-16)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/kris-bowers-mn0002391273/biography

Kris Bowers

(b. April 5, 1989)

Artist Biography by Matt Collar

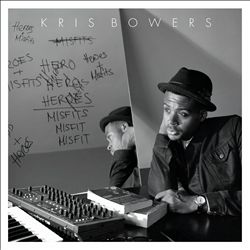

A gifted pianist and composer, Kris Bowers makes genre-bending jazz that touches upon contemporary R&B, electronica, and forward-thinking modal improvisation. Bowers gained wider prominence after winning the 2011 Thelonious Monk International Jazz Piano Competition; he released the expansive Heroes + Misfits on Concord in 2014. He also composes for film, having contributed the soundtracks to the 2013 documentary Elaine Stritch: Shoot Me, and 2017 television show Dear White People.

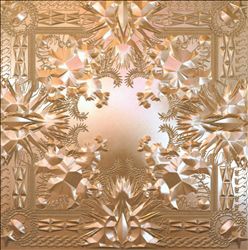

Born in Los Angeles, California in 1989, Bowers grew up listening to his parents classic soul records and hip-hop before falling under the spell of jazz, classical music, and film scores. He studied classical piano and jazz while attending Los Angeles County High School for the Arts, and performed in numerous festivals while still a teenager. After high school, Bowers earned both undergraduate and Master's degrees in jazz performance from Juilliard. It was there that Bowers began making a name for himself as a formidable jazz musician and he found regular work gigging around New York City. In 2011, Bowers won first place in the prestigious Thelonious Monk International Jazz Piano Competition. That same year, he showcased his versatility by appearing on Jay-Z and Kanye West's collaborative album Watch the Throne.

In 2014, Bowers released his experimental jazz, R&B, and electronic-influenced debut album Heroes + Misfits on Concord. Around the same time, he began branching out into film work, scoring the soundtrack to such productions as the 2013 documentary Seeds of Time, the 2013 documentary Elaine Stritch: Shoot Me, the 2016 documentary Norman Lear: Just Another Version of You, and the 2017 scripted drama Dear White People. In 2018, he supplied the soundtrack to the biopic film Green Book, about pianist Don Shirley.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/krisbowers

Kris Bowers

Kris Bowers

Pianist Kris Bowers is one of the newest and brightest lights on the jazz landscape. Schooled in jazz and classical music, raised amid the rap and hip- hop of the 1990s, inspired by the cinematic power of the great film composers of recent decades, Bowers’ sound – though rooted in traditional styles – is open to numerous external influences that keep the music fresh and vibrant for a new century. This rich and eclectic sensibility is evident from the very first notes of Heroes + Misfits, his debut recording on Concord Jazz.

Bowers' musical sensibilities were taking shape before he even saw the light of day. The story has it that his parents positioned headphones on his mother’s belly and piped soft jazz directly into his evolving consciousness in the months before he was born. And it was just the beginning.

Born in 1989 in Los Angeles, Bowers was raised by parents whose tastes ran to Stevie Wonder, Earth, Wind and Fire, Tower of Power, Marvin Gaye and other purveyors of old-school R&B and funk. He was learning the rudiments of piano via the Suzuki method by the time he was four, and taking private lessons at age nine. By the time he reached middle school, he had developed his ear to the point where he could learn the pop music of the day just by turning on a radio, picking up melodies and harmonies, and developing improvisational lines.

Despite his parents’ retro sensibilities, Bowers’ tastes leaned more toward the rap and hip-hop of the 1990s. In addition, he was drawn to the music of Howard Shore, Michael Giacchino, John Williams, Danny Elfman, John Powell and other high-profile film composers. Inspired by the diversity of music in the world around him and frustrated by the restrictions of his classical training, he threatened to give up the piano, so his parents countered by enrolling him in jazz lessons.

“When I started taking the jazz lessons, I felt like I was doing something different enough that I was appeased for a while,” says Bowers. “I liked the freedom of jazz. The truth is, a lot of popular music – including the music I was listening to as a teenager – came from jazz and the blues.”

High school was a dual musical track for Bowers, who attended the Los Angeles County High School for the Arts while also taking classical and jazz classes at the Colburn School for Performing Arts. Guided by some of the older students at Colburn, he discovered the solo recordings of Oscar Peterson, while at the same time performing at numerous jazz festivals as part of his LACHSA curriculum.

“We did a lot of festivals in high school, and a lot of touring, in places like Boston, Minnesota and upstate California,” says Bowers. “I had been gigging around since middle school, so by high school I had a clear sense that music in general – and jazz in particular – was the career track I wanted to be on.”

After high school, Bowers began his undergraduate studies at Juilliard in 2006. Once he arrived in New York, he realized he could earn a living as a jazz musician while attending school at the same time. He studied privately with Eric Reed, Fred Hersch, Frank Kimbrough and Kenny Barron.

“I think my high school experience helped prepare me for all that,” he says. “It wasn’t as overwhelming as it might have been otherwise. It wasn’t some crazy leap forward from what I was already used to.”

Bowers finished his undergraduate degree at Juilliard and stayed on to earn a master’s degree in jazz performance with a concentration in film composition. In September 2011, he won the coveted Thelonious Monk International Jazz Piano Competition at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC. Co-chairs of the program included Madeleine Albright, Quincy Jones, Debra Lee and Colin Powell, and the competition was judged by Herbie Hancock, Ellis Marsalis, Jason Moran, Danilo Perez and Renee Rosnes.

A year later, he was hand selected to perform at the 2012 NEA Jazz Masters Awards Ceremony at Jazz at Lincoln Center. His performance included guesting on a rendition of Frank Wess’ “Magic” with jazz masters Benny Golson, Wynton Marsalis, Wess, and the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra.

Although considered primarily a jazz artist, Bowers has never been afraid to step outside of the genre’s traditional boundaries and dabble in other forms of music. He performed on Watch the Throne, the 2011 collaborative album by hip-hop artists Jay-Z and Kanye West. In addition, he recently composed the score for Seeds of Time, a 2013 documentary by Sandy McCloud about the preservation of naturally occurring seed in an era of genetic engineering in agriculture. Bowers has toured with Jose James, worked with Marcus Miller and Aretha Franklin. Bowers was a featured artist with NEXT Collective’s “Cover Art,” released February 2013 via Concord Jazz.

Heroes + Misfits, scheduled for release on Concord Jazz in March 2014, is an ambitious debut album that positions Bowers at the forefront of a talented sextet and showcases a musical and compositional style that – while clearly rooted in the jazz tradition – is also reflective of an eclectic musical age.

Kris Bowers: In Love With Accompaniment

Kris Bowers is one of the humblest and most introverted composer/performers I have ever encountered which is astounded considering his accomplishments—winning the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Piano Competition at 20, a daytime Emmy four years ago, and now one of the most in-demand composers for film and television, most recently scoring the Netflix sensation Bridgerton. And yet it all makes sense when you begin exploring Bowers’s incredible versatility, his openness to all genres of music, and hear how attuned his music is to whatever project he is working on as well as all the musicians he has worked with.

“As a jazz pianist, one of the things that I fell in love with was accompaniment,” he acknowledged when we spoke with him about his music and career back in October. “I’ve never really wanted to be the center of attention in a performance space.”

Scoring films and television series might be the ideal medium for Bowers since it allows him to immerse himself in the characters and plots which should be foregrounded rather than the music. Nevertheless the music he writes is always attention grabbing and works well as a listening experience independently of whatever it was originally written to enhance, whether it’s the score for the 2018 motion picture Green Book, which was based on the life of composer/pianist Don Shirley, or the 2019 EA Sports videogame Madden NFL 20. Whatever project he is working on, Bowers always operates from a zone of empathy.

“That’s the only way that I can really get to something honest,” he explained. “I think that it’s more likely that it will reach other people if it’s something that came from an honest and emotional place for me.”

Considering his need to relate to the characters he creates music for, it’s somewhat surprising that Bowers also composed the score for Mrs. America, a 2020 Hulu series about the conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly. “I actually really loved needing to represent this human side to this character that I didn’t agree with,” he admitted. “It even helped me understand or remind myself that those people that I might disagree with politically, especially in a time like this, that they’re humans at the end of the day. And that’s something to keep in mind and to really remember.”

As a Black composer who works in a medium that is still overwhelmingly dominated by White composers, it is also important for Bowers that his music not be typecast and the fact that he has worked on such a wide range of projects, in which he has explored an extraordinarily broad range of musical styles, is testimony to his music being impossible to typecast at this point.

Frank J. Oteri in conversation with Kris Bowers

October 22, 2020—12:30pm EST via Zoom

Call between Los Angeles CA and New York NY

Produced and recorded by Brigid Pierce; audio editing by Anthony Nieves

(Transcribed by Julia Lu)

Frank J. Oteri: The goal of writing for a narrative story is that it doesn’t get in the way of that story, and that it’s kind of there enhancing it, but not calling attention to itself. So, how do you navigate that since you’ve got great music that people want to hear?

Kris Bowers: You know, it’s funny, I feel like for me, it might have started because you know, as a jazz pianist, one of the things that I fell in love with was accompaniment. I’ve always been a pretty introverted person, and I’ve never really wanted to be the center of attention in a performance space. And I also started to discover these jazz pianists like Wynton Kelly or Kenny Kirkland or Mulgrew Miller that were incredible accompanists. Like whenever Miles plays something, Wynton Kelly is right there to supply the perfect chord to accompany that or fills in the hole as a response in the right way.

And so once I really discovered that, for me I felt like that was the biggest pride I had as a pianist was my ability to accompany. That translates pretty seamlessly for me into film scoring where I’ve always felt like that’s a bit of the magic about what a film score can do is that it makes you feel something and you might not even really register that it’s the music that’s contributing to that. I read somewhere once in a film scoring book that it should be like a really great massage. You shouldn’t realize when the hand comes off and when it comes back on. It should be seamless just like that and all those different things I think kind of make it so that that’s an aspect of film scoring that I actually really enjoy that people can discover later that it’s something that gives them an emotion and a feeling and they maybe didn’t realize it when they were watching the film.

FJO: It’s interesting you bring up Wynton Kelly. I was actually listening to one of his albums last night. He was a great player and a great accompanist, but also a great leader. And there aren’t too many examples of it, mostly trio stuff. But I was listening to this album, and there’s a great tune of his called “Keep It Moving”—

KB: —Oh yeah. I remember that tune.

FJO: It’s a fantastic orchestration, the way he navigates between flutes and horns.

KB: For sure.

FJO: And Mulgrew Miller, whom you actually studied with.

KB: He was just kind of more a mentor that whenever he was in town he would come over either to my parents’ house and give me a lesson, or I would go to wherever he was and we spent a lot of time together over the years.

FJO: The other thing about writing for film, TV, media, narrative drama and underscoring is that you really have to be a chameleon. You have to be able to embrace a zillion different styles. So you may love Wynton Kelly and his sound world and you’re coming out of jazz, but you have to be a jazz composer, a rock composer, a Baroque composer maybe if you’re doing a period piece, or any one of a million different kinds of styles have to be part of your language.

KB: It’s something that I also really have always loved about film scoring, because I’ve always been into different styles of music; it’s almost like I’ve had different periods of my life. Most of my childhood, I was listening to mostly popular music, or the music of my parents—like funk, R & B, and things like that. Then when I got to high school, I pretty much only listened to jazz. At some point, when I was in high school, I used to tell my parents that I wasn’t going to play anything else other than jazz, because I was that obsessed with it. All this while studying classical music and starting to fall in love with it. But specifically film score music was just something that was really important to me as well.

Then when I got to college, I started getting more into indie rock and hip hop and alternative music. I think for me that’s what attracted me to film scoring was that I kind of need to be this chameleon, or chose to be, because I think there are also composers that just do their thing and that’s the sound and the vibe that they bring to the films that they do and they don’t feel the need to be able to do everything. But I think for me, I’ve always been inspired by composers that are able to do everything, because I have so much love and appreciation for every style of music. There really isn’t a style of music that I could listen to and not find some sort of respect for, especially if it’s done really well, within that context. So, for me, it’s always just a learning experience. Every project, or every genre that I might need to look at that’s a little different than what I’m used to, for me I want to give it the level of respect that it deserves, which requires research, and spending a lot of time, like learning how to play it and getting into the feel of it. I’m only a better musician after spending that time with any genre. And so it’s kind of a fun aspect to this job.

FJO: That’s so wonderful to hear that open mindedness. But it’s also learning it, researching it, and then making it your own—finding your own solutions within those frameworks. I want to bounce off of something you said about certain film composers where you can identify their sound. Bernard Herrmann—I always know when a score is by him. It has that sound. John Williams has a sound; he loves the brass. There have been a few examples historically of jazz composers who did one-off scores for films. There’s that great example of Otto Preminger’s film with the Ellington score—

KB: —Anatomy of a Murder.

FJO: That was unprecedented at the time. And then, Miles Davis did a score for a French film in the ‘50s. Ornette even did one. David Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch, the William S. Burroughs adaptation, which is wild. But they were all brought on to bring in their sound, which is very different than being hired by somebody to have the music fit their vision of what the film is. So I wonder what your leeway is in terms of what you want to do versus what the assignment is, and how you navigate that.

KB: I always like giving myself limitations or rules, or a box, and then going wild within that space. One of my favorite things to do when I used to practice improvising during school was tell myself I’m only going to improvise within these five notes or within this octave. Or I’m only going to use these notes, and because of that, you then have to figure out how to be more varied with the rhythm, if you’re only using a couple of notes. So my first step usually when working with a director is having a conversation with them about their palette, what kind of music they like in general, even outside of the context of this film. Discovering some of the music that they might like or some of the sound that they might like that’s a little different than even what they’re articulating they want for this project, which is helpful. Once we start to figure out what palette they really want for a project or for the film, I usually like trying to figure out how to push the boundaries of that and how to experiment within that. Often I’ll start with a pitch of what I think might be an interesting way to do that.

Recently I was just talking to somebody about a sci-fi film. It’s set in the future, but it’s really about this married couple; one of them has a terminal illness. So with that, one of the things that came to mind for me was that this should feel a little bit more intimate as opposed to sci-fi. Like the sci-fi aspect should be maybe a backdrop to this, this story about these characters so that the music should really reflect that, and it’s something that they agreed with, and so that’s the direction that I might go with that. But within that context, I’ll probably stretch the boundaries and try a bunch of different things, but the one thing that I won’t do is have a very synth forward score for that because that’s what we talked about not working. You know, and so it’s like, now that I had that rule for myself, I can kind of play around and do all these crazy things within the context of the rules that we set which is a bit helpful for me.

FJO: That’s fascinating because sci-fi is always some kind of synth forward, like in the early days, you know, if it was a sci-fi film, there was always a theremin.

KB: Yeah.

FJO: And then in the ‘70s, with Jerry Goldsmith, it’s like all these wacky analog synths, and doing all this oddball stuff. Now that synths are everywhere, synths are the present, so they’re not necessarily the future.

KB: Yeah. That’s true. It’s funny how it’s been set up as like you said so much of the vernacular. It’s the sound we expect; it’s not maybe what it actually will be in the future. I’m curious to see what that sound will actually be when we’re 50 years from now.

FJO: You did this amazing score for Green Book, which is all about Don Shirley, and the piano is the centerpiece of the orchestration for that. And obviously, it’s because you come from a piano background, but also because Don Shirley was a pianist. It would be really weird if there was no piano in that sound track.

KB: Yeah. Interesting. We had talked about possibly trying and, and decided not to, but yeah. I think that, to me, it’s like: what is that choice representing narratively, right? I’m working on another project. It’s a pianist, and the pianist ends up not being able to play piano for a while and with that, it probably makes sense for there to not be piano in the score because it’s representative of this thing they’re struggling with, even though they’re pianists or the idea could be—it’s something that hasn’t even started yet—it could be if we add piano to that, then maybe that’s something that makes us continually think about what this person doesn’t have in their life. You know. So it’s like kind of trying to figure out what makes the most sense. And with Green Book, like you said, I felt that the score represented more of the music and sound that I imagined to be inside of Don Shirley, because I felt like the music he created and the music that we hear in the film, a lot of it is stuff that he honestly didn’t really want to do, or felt like he was being forced to do. The music that he really loved was more classical or Negro spiritual and all that, and so trying to figure out a way to very slightly represent them in the score was my decision there.

FJO: And, of course, the challenge with somebody doing a score about Don Shirley is that you don’t want to be sounding like Don Shirley necessarily. Did you listen to a ton of Don Shirley before you wrote this score?

KB: Because we had to do all the songs beforehand, and all of that stuff, I had to transcribe. I was pretty drowned in Don Shirley for the few months before and during shooting. With my transcribing, and with the performance, I really wanted to try to play as close to his playing as possible. Then with the score, one of the things I chose to do was actually have another pianist play the score because I felt like I wanted it to be a different sound when you hear the Don Shirley music. There were a couple of score cues that are meant to kind of mimic his sound as well that we hear in the beginning of the film. And so that’s all me playing. And then, once we get into the orchestral stuff, we have another pianist that played primarily so that it had a different feel, a different touch, a different sound, so that it could feel a little bit less, like you said, like Don Shirley as far as the way it was played.

FJO: So to get into the zone of empathy with the characters you’re writing about—obviously with Don Shirley, there are lots of connections. He was a pianist, a composer, somebody straddling genres. That’s someone you can identify with. You’ve also done a number of scores for sports-related stuff. Kobe Bryant is—was, sadly—a hero to so much of the community. Somebody who’s easy to identify with. Or the Central Park Five, the outrage over that is definitely something that you can have a zone of empathy for, even though it was before your time.

KB: Yeah.

FJO: But then you just did a score about Phyllis Schlafly. I don’t think that she’s somebody that’s necessarily easy for you to identify with. Or maybe not.

KB: Yeah. Well you know, it’s funny. I feel like I could identify with the fact that I have a lot of family members that I don’t agree with on their views of the world, or their views of politics, or different aspects of life. But, at the same time, I have a profound love for them and appreciation for them and understanding. And so I think that when I first read the script for Mrs. America, that was the thing that made me most excited was that I read the first three episodes, but with that first episode, they wrote it in this way where you’re kind of rooting for this character and really want to see her win until you find out at the end of the episode what her new objective and goal is with the ERA.

Throughout the season, then, you are dealing with this character that’s very human, but then at the same time is doing something that a lot of us feel is really terrifying and horrifying. And so, for me, that’s where it gets really interesting, because that’s real life to me, you know. There’s so many people that, especially in a time like now, we’re so divisive and we feel like everybody that doesn’t see exactly the same way we see the world that they’re bad people, and it’s just so much more gray than that black and white, and those people are most likely good people to somebody in their lives. Like somebody in their life thinks that they’re a good person. They’re doing something for love. They’re trying to operate from a place of love in their mind, and so you know, trying to figure out how to see that human side of people I think is maybe the best way for us to not be in such a divisive horrifying place. So I think that content and films and TV that do that are really exciting to me.

I actually really loved needing to represent this human side to this character that I didn’t agree with, because it even helped me understand or remind myself that those people that I might disagree with politically, especially in a time like this, that they’re humans at the end of the day. And that’s something to keep in mind and to really remember.

FJO: Wow, beautifully said. To take it little further then though, so you do kind of have to develop a level of empathy for the characters you’re writing for, always.

KB: Yeah, that’s the only way that I can really get to something honest. I think that any time that I did not really feel that, whether it’s because of the acting or the writing, or just because I didn’t connect to the story for some reason, it was really difficult for me to write music. There are of course times where I write something that maybe I’m not as connected to that still affects somebody, but I think that it’s very difficult, and I think that it’s more likely that it will reach other people if it’s something that came from an honest and emotional place for me.

FJO: So are there projects you wouldn’t sign onto because there’s no way you can feel empathy for the character?

KB: If I’m not particularly connected to the writing, I think that sometimes that might be an instance where it’s difficult to feel empathy for a character, maybe because the character hasn’t been developed in a way that is allowing for that for me. If the writer or director—whomever has created the story—is not trying to represent these really honest aspects of people. I think that if somebody’s going to present a very shallow version of somebody, or a very stereotypical version of a character, that’s something else that I don’t really feel that excited by or connected to, being a Black man. Being a person of color and seeing how much the type of content that’s been made with people that look like me has affected my life, has affected the way that I see myself, especially growing up in the ‘90s and looking at how Black men were represented during that time, and looking at now, and looking at some of the ways that Black people are being represented today, and how beautiful that is and how it affects me. I feel like it’s really reaffirmed for me that anybody that’s not trying to push the boundaries and figure out how we can be represented even in really beautiful and complex and positive ways, I don’t really feel like I want to be a part of that, either, the negative side of that.

FJO: You’ve done a lot of scores for stories that have Black central characters, which is why the Phyllis Schlafly thing really stands out. But I’m also thinking of the show For the People, because there you have a very wide cast of all different kinds of folks. Why should you be typecast: “We’re only going to hire Kris Bowers when we have this story about a Black protagonist”? You should be able to writes scores about anybody, just like anybody else writes scores about anybody.

KB: That’s the hope, right? I think that we’re getting to a place where people are starting to understand that and see that and see the issues with not feeling that way. When you brought up some of the Black composers from the past and thinking about Quincy Jones’s story and how I just read recently that the first feature that he did that wasn’t any sort of jazz or Black thing. It was Henry Mancini that recommended him for it, recommended Quincy to this director, and the director essentially said, “I don’t really know if I want a Black score.”

And Henry Mancini had to tell him that Quincy really could do what he needed for it, and of course, he ended up hiring him and then the rest is history. But I just had a conversation with a director recently. They’re making a story about a Mexican character that comes to the States, and I expressed that they should maybe reach out to a Mexican composer or at least a LatinX composer and their response was, “Well I don’t really want a Mexican-sounding score for this film.” And I think the fact that 60 years later that conversation can still be had where somebody feels like they are worried about somebody only being able to write within a very small medium or genre is just a little disappointing. But I think that at the end of the day, we are getting a little bit further. Having conversations about it, I think, is a pretty amazing thing, and I feel really fortunate that I’m getting a lot of opportunities that don’t have to do with my race. And I feel like it’s kind of a newer thing for composers of color to be writing music for projects that don’t have to deal with that. And I think that has more to do with the directors and producers that are maybe now starting to feel a little less nervous about that than anything else, because I think the talent has always been there in these communities of color.

FJO: I know that you’re involved with the panel for a program that we’re overseeing at New Music USA, which we’re calling the Reel Change Program, which is a way of incentivizing and creating opportunities for a much wider range of composers than the folks who are typically associated with writing music for film. I’m curious about how you got involved with this project, and what you can to do to be a role model for others now that you’ve made it, as it were.

KB: I don’t know about that, but I’ve been introduced to New Music USA a little while ago and I was talking to them about coming onto their advisory board and I have a couple of friends that have been funded, or given grants by New Music [USA] and had done a bit of research about the organization during that conversation and it was kind of just after that that they reached out to me about this program that they’re doing to increase diversity in this space, and I felt like it’s so exciting because it’s something that if it were around even a few years ago, I definitely would have applied to it. And I feel like it’s something that can continue to encourage composers of color to pursue what they’re trying to do on a level that maybe they didn’t think they could before. You know, being able to write a score for a film, and record it with a decent sized orchestra, or small chamber group, or whatever you’re able to do with the funding that they might get from this grant. I feel like it’s something that often doesn’t really happen until you have a full-budget project, and those are kind of hard to come by these days, especially for newer composers.

It’s something that I really hope for whomever is able to receive funding for it that it really gives them a boost in terms of not only visibility or their career, or things like that, but also the creative aspect. Up until I started doing scoring sessions, I wasn’t able to have a group of musicians of a large size, play my music since college. When you’re in school, you can ask people to do that for some pizza or something like that, but I think after that people are expecting to get paid and you have to have a budget to be able to do that. And that’s really difficult. And so whenever you’re able to do that is the first time you’re able to have a budget enough to have a large group of musicians get together and play your music, it’s such an amazing and special feeling as a composer. It’s something that really just allows you to hear your writing on that level, and hear where you’re at. And it’s something that I think that young composers of color would really benefit from and it could really inspire them to continue on the path that they’re already trying to go on. Especially at that early stage, which can be a bit difficult and trying.

FJO: I want to talk about this from a slightly different angle. It’s great that it’s an opportunity for all these composers, but it’s also a really important opportunity for audiences, for our society. Considering how wide-reaching film is, and even more wide reaching television is, and the stories that get told there. And they get told in part through the music. So it’s the people directing, it’s the people writing the screenplays, but it’s also the composers. Everybody. The more variety of people who are involved in this, the greater variety of stories are going to reach the public and hopefully give greater empathy to the people watching these things. If a work of art does something good, it moves you. It makes you think about something in a different way, and it gives you feelings of connectedness to these people. Then maybe we could have something to counter what you were saying earlier, that people aren’t understanding people who don’t agree with them. We’re at this terrible point. Maybe if more people got to tell these stories, and write the music that goes with these stories, that would change.

KB: Yeah. I totally agree with that.

FJO: And is that something you think about when you decide to take on a project?

KB: There are times where I think of that maybe in different parts of the process. I think that or most of it honestly is just focusing on trying to do the best job possible, and I think that I am almost challenging myself to be better today than I was yesterday, and push myself probably a little bit too much with that. And so I think that often I’m mostly consumed with trying to do as a good of a job as possible, not thinking so much about how a project might be received, or how it might be received that I’m working on something. But I do think that every now and then, especially in conversations with other people. It’s interesting to be mindful of that for my own community, for anybody else that’s watching. It’s interesting to talk to other young composers or people in the industry in general; that kind of talk about being excited about my career because of what it represents.

It’s such a weird thing for me, because you know, it’s something that most of my childhood and most of my life, I’ve thought about getting to, even this point and imagining what I wanted to do in my career. It’s only now that I’m starting to realize how interesting it was that I imagined all that as a young Black boy and didn’t have many role models as far as Black famous film composers that I could be looking up. And the few that I did have, like Quincy and Terence and Marcus Miller, I definitely was pretty obsessed with as well. But I also felt just as much kinship with John Williams as I did Quincy Jones and Terence Blanchard. I didn’t really see the barrier of race until I started dealing with it, until I got into the industry itself. It’s been interesting to navigate that and see how my career is being received. I don’t really think about that too much, probably just because it’s a bit strange to think about. But as far as other composers, I definitely see that and feel really excited by that and feel exactly what you’re talking about. Seeing someone like Germaine Franco or Michael Abels and what their music does for projects and what it’s doing for people that see their careers and see what’s happening with what they’re doing—it’s really, really beautiful.

FJO: So, let’s talk about where your career started, because we kind of talked around it all this time. You talked about announcing to your parents that you’re only going to listen to jazz; you’re only going to play jazz. Then you go on, you win the Thelonious Monk Competition which is one of the biggest things you can win as a young, emerging musician. But then your career goes in a completely different place. So what happened?

KB: Well, it’s really impatience, I think for me. When I graduated high school, I told my parents that my plan was to go to college for jazz piano and eventually tour with one of my favorite artists, which at that time was Terence, and tour with him for a few years, and then transition into touring with my own band, and do that for a few years, and then I’ll get into film scoring a little bit later. So film scoring has always been the goal, because when I was younger, my dad was a writer for film and TV. Movies were just always a big deal in our house. I started playing piano when I was four; that was the way that I really processed these films emotionally. I think that I loved the stories and all of the action on screen, all the movies in the ‘90s that really inspired me, but the thing that felt really magical to me was the fact that I could go listen to the score outside of the context of that and still feel the same excitement and nostalgia and emotions that I was feeling when I was watching the film. And so I got into film score music when I was probably maybe like 10 or 11 and again told my parents for a pretty long time that that was going to be my goal and my plan.

But then I started touring, and I think after being on tour, ultimately I ended touring for maybe about three or four years, but one of the first tours I did was with Marcus Miller for a year. And I think with that tour, we got into a bus accident and the driver passed away, and it was a pretty traumatic experience. Then I toured for a couple of years with this singer José James and my own band, and especially touring with my own band, feeling just the difficulty of being on tour. I think that it’s something that, some of the musicians used to joke about the fact that we don’t get paid to play. We get paid for everything else that goes into touring. Like the airport, the plane, the bus, all that stuff. And you know, especially as a band leader, where you’re doing all of that and usually not making money. Often losing money. Trying to take care of your band members and all those different things. I had a point where I realized I would rather be up until five in the morning at home working on a score than at five in the morning getting on a bus to go to the next city, essentially. And so I decided to try to find a way to get into it a bit sooner than I was planning. But it was kind of always the goal.

FJO: So that first break, getting the first gig scoring something—how did that happen?

KB: So I kind of think of it as two times. The very first thing I ever scored happened because after the Monk Competition I ended up connecting with Aretha Franklin, because she was getting an award that same year from the Monk Institute, which is now called the Herbie Hancock Institute, but she heard me play in the semi-finals and asked to meet me. She asked for my number and after the competition, she called me and just kept in touch with me, and I continued to play for her birthday and Christmas parties, and kept in touch with her for a number of years until she passed. The first conversation I had with her, she was like: “I think you need a manager. I think that’s the first thing you need. And to be honest, your manager should be your biggest cheerleader. So I think you should maybe consider hiring my publicist to be your manager because she would make a great manager just with the excitement and energy she has. If you have that kind of manager, that could be really good for you.” And so this woman, Tracey Jordan, she was my manager for maybe a year or something like that. But during that time, because I had talked about film scoring so much, she made it her mission to try to find a film for me to score. And the first film was this documentary about Elaine Stritch, the Broadway actress. And that came because of this woman, Tracey Jordan. She was friends with the director and they were looking for a jazz score. I had just won the Monk Competition. They brought Elaine to my senior recital at Juilliard, and then they all decided that the music I made was a good fit. And so that was my very first project.

Then that same director produced a project that I did after that and then I didn’t do anything for a couple of years. It wasn’t until a friend of mine from high school—we actually didn’t go the same high school together, but we were in a high school all-star jazz band together. I used to talk about film scoring so much back then that he came to a show of mine, and we hadn’t spoken to each since we were both in high school. He came to a show of mine, with my own band, and said, “I’m working on this documentary about Kobe Bryant. And I remember when we were kids, you used to talk about film scoring. And I’ve been checking out your music, and I really love your music. And I think it could be a good fit.”

That project really felt like the big, first break because that led to working with Kobe up until he passed, that led to doing three or four other documentaries for the same directors and producers. And also the music that I did for that is what helped me get into the Sundance Composers Lab, and also got me my first agent, and all that. So I really feel like the Kobe documentary was the one that really catapulted things. But the very first one was the Elaine Stritch documentary.

FJO: Fascinating. And did you get into the zone of empathy for Elaine Stritch writing that score?

KB: Yeah, definitely. Especially because she was dealing with so much at the time; she was diabetic, but then also an alcoholic, and also you couldn’t tell her that she wasn’t going to live her life the way she wanted to because of her personality and the way that she was. And so the feeling for that score was this balance of this side of her that was very sweet and loving—and you think about her relationship with her husband, and all that, and also representing the vulnerability that she was facing with her health—but then, at the same time, having this kind of bold and unapologetic side to the score as well. That was kind of like the first time that I started to figure out how to represent these aspects of somebody through a score.

FJO: So, I keep harping on this zone of empathy thing because I listened to an interview you did when you were talking about scoring the NFL videos games that you’ve done. And what I thought was interesting about that is you’re scoring for a user who you don’t necessarily know. So the zone of empathy you have to create is for somebody who could be anybody. It’s the end user. So how do you get in the zone where you don’t know who the person is that you’re scoring?

KB: Yeah. I think with that, it really came down to the genre, quote-unquote, or the sounds that was inspiring the music. You know, for the video game, there is a narrative that’s happening, where basically you’re trying to, you’re trying to be drafted. That’s the goal both years that I worked on Madden. And, because of that, the thing for me was establishing a theme for the character, and then figuring out ways to kind of play with that theme as they’re going toward this goal. But the sound of the theme, I think the first year for me it was almost more representative of myself in terms of the music that I’m into. And having this wide range of musical inspiration where I wanted the score to feel like it was inspired by Dirty Projectors just as much as it was Thomas Newman, just as much as it was some hip hop artist. And so I think that was kind of the idea there, trying to meld all these genres, and for me I felt like it was maybe a good approach just because of how much most young people these days are into a wide array of music. That’s kind of more what it was representative of was just the fact that like as a generation, I think that we are all so into all these different styles of music.

Then, for this most recent year, the head of music for EA Sports, Steve Schnur, really wanted to push it even further, into almost like more into the hip hip space, I think primarily because that’s the sound of Madden in general. Like when you’re playing, they have the game side of the game, and then there’s also this narrative side to the game. And the last two years, the narrative side to the game had much more of a cinematic sound. I think the year before I did it, it was John Debney, and the year before that, it was Jeff Russo, or maybe I got this reversed, but that’s the sound that they were bringing to it and then again, the first year that I did it, although I was melding all these genres, it still was primarily orchestral and very emotional and cinematic. And this year, we went full on production and it sounds more like beats than an orchestral score. There’s still a lot of moments where we have strings and emotional things, but it was trying to get a little bit closer to the sound of the rest of the game.

FJO: I haven’t played the game. I’m not really a gamer. But I did manage to track down a lot of the music and listen to it. And I loved the track that you did called “Game Time,” which sounds like it’s backward sound. So you were really able to experiment within that, too, which I thought was really cool.

KB: Yeah. Yeah, definitely. It’s really amazing to have that space where they didn’t have any notes or critiques, they just kind of took anything that I would throw at them, and so it really allowed for us to kind of play and do some really interesting and different things.

FJO: That leads to a question about the different kinds of media to score for. You know, the difference between writing for a narrative film, writing for an ongoing series that has new iterations each week, or a game. The music serves a similar function in these different mediums, but because the formats are very different, I think there are different things that you can do in them. And maybe different things that you have do in them. So I’m curious about how you approach the scoring project. You said something about Phyllis Schlafly. At first, you don’t know what she’s going for, so you’re writing music that’s really kind of on her side. And then eventually you find out in later episodes. Whereas, with a film, you don’t have that kind of sequential thing in the same way.

KB: Thematic development is the biggest difference with all of those. When you are working on a TV show the development not only happens over such a longer period of time, but it’s also how that develops through an episode versus through the whole series can be really different. And sometimes an episode is focusing on something that is maybe just another aspect to the story. And so there might be a time where you’re focusing on just this other character or this part of the story and so that’s the theme and that’s the idea that you’re trying to tie together by the end of the episode. And maybe that theme doesn’t even appear again throughout the rest of the season. Or maybe that theme only appears again at the very end when they revisit whatever it was that you were talking about in that episode. So the way it’s spaced out is not only different in that way, but also tough. For the most part, I do get scripts, so I do try to read ahead so I can have an idea of what the entire season is before we see it. But then outside of that, if we don’t have a script, we’re really learning about the show on a week-to-week basis as we work on it. So you know, we’ll be doing a spotting session, and then after the spotting session, I have maybe a week to ten days to turn around the score. And then we do the spotting session for the next episode. And because we’re usually so focused on a specific episode at that time, I’m not really looking ahead. So I’m focused on that episode, and I’m trusting the director really at that point to help guide what we should be feeling emotionally, and trusting their process with letting me know how big or small we should make something in an episode because of how it ties to the rest of the series.

With film, it’s much easier for me to have an idea of that because I’m watching the whole thing, but then you have so much more music usually that you’re trying to fit and create some sort of continuity and through line. The video game thing has been interesting because you have to find ways to create loops and these different things that as soon as this decision’s made on the game, now this other musical element comes in, so that it feels like something shifted. Those types of things are really interesting because you end up writing much more modularly where I can write something that they can build, with the build of a scene in the game. So if they have a track that has a drum beat, a horn part, and then a synth melody, they want that separated out so that they’re able to just do the drums and the horns first, and then they add the synth melody when this decision’s made or something like that. That’s kind of interesting as well.

FJO: The other challenge of video game music is that it’s non-linear, because depending on how you do in the game, you’ll go to different places in a different order. Music is all about existing in time, and this kind of shatters that.

KB: It’s almost like creating a mood and shifting with those small decisions, but that large kind of continuity or path is a little different or hard to or impossible to even track. So it’s kind of not written in that way, I guess.

FJO: I can’t believe almost an hour’s gone by and we haven’t talked about Heroes and Misfits, which is such an amazing album. And I did want to talk to you a bit about it. And now a lot of things about that album make sense now in terms of you saying what you like your role to be and being introverted and being collaborative because that album is so many different things.

KB: It’s funny because when I wrote it, one of the things that I felt really charged by is—I don’t know if it was a teacher or mine, or a friend of mine—somebody mentioned how whenever you hear a musician’s album, you know whose album it is by who’s the loudest on that album. Like you know it’s a bass player’s album because the bass is way louder than any other album you’ve ever heard before. And for me, I felt like I didn’t want that. Maybe it’s because I see myself as a composer just as much, if not more than a pianist. But I think that for me, it was like creating this feeling in this space, and the best way to get to that feeling. Often it’s not a piano feature or something that was going to feature me as a musician, but could I create or engineer a feeling compositionally, and so that was kind of the biggest driver for me for that album was just representing these different ideas that I was into about our generation and different things like that. But compositionally more than as a player.

FJO: Well I’m thinking of my two favorites tracks on that album which are very, very different from each other. The opening “Forever Spring,” which is this amazing sci-fi music in a way.

KB: Yeah.

FJO: Then the song “Forget-er,” which is so poignant, and there are so few words to it. And they just repeat over and over again. But it just sets this mood. It’s so evocative and it’s magical, but that’s something you co-wrote with Julia Easterlin, and I’m curious about your openness to collaborating not just in the performing of the music, but in the actual composing of it.

KB: Yeah. That was such a special process because I wrote a lot of that album when I was on tour, because basically I won the Monk Competition, and you get a record deal from that competition, but I also immediately started touring with Marcus Miller after that. And so we decided that it made more sense for me to continue to tour and push off my record release by like a year. I won the competition at the end of 2011, and so my album should have come out in 2012, but it didn’t come out until 2014 because of the touring and all that. And so I was writing a lot of that music while on tour and wanted to collaborate with people primarily because I always feel like collaboration pushes me in different directions that I don’t expect myself to go or wouldn’t have gone by myself.

And so songs like “Wake the Neighbors” that I wrote with Adam Agati, my guitarist, and “Forget-er,” the way that I wrote that with Julia was all remotely. Basically she sent me just the sounds. She was really into loop pedals and creating these soundscapes with just her mouth and she even does body percussion and things like that to create these interesting sounds and textures. And so she sent me a loop first that were just sounds that she created. And then I created a chord progression over that, and some kind of percussive ideas and then she sent me back a slight melody idea, then I kind of sent her back another section. And so the first time we actually ever worked on the song together in person was at the recording session because we had written it all virtually up until that point. And then in the recording session kind of figured out how to do it performance-wise. But that first part of the track, before it goes into the instrumental solo section and all that, that first part of the track was all conceived over email. And it was really cool to get something and then I added a little bit and sent it back to her. And you have no idea what you’re going to get back, and there are times where I would add just a little bit and get something back from her that took it in a totally different direction than I was expecting. But that’s the beautiful thing about collaboration.

FJO: You did a score for the Alvin Ailey Dance Company which is also media music, but it’s media music in a different way. Because there’s no spoken narrative, the music is allowed to shine. You’re focused on the dance with your eyes, but your ears don’t have any other distraction besides the music. So in a way, it allows the music to be more foregrounded, even though it’s still media music and still collaborative.

KB: Yeah, and often what’s interesting with that is how much the music was informing the movement as opposed to vice versa with film, where I’m responding to something else. And it’s always fascinating to me to work with dancers, with Kyle Abraham, who was the choreographer for that piece, we had worked together a little bit before. The way that he works is similarly talking about a feeling and this emotion that we’re trying to convey. That Alvin Ailey piece had to do with people that were talking to family members of theirs that either were incarcerated or previously incarcerated. And how that made them feel. And so there’s a very clear motion that we were dealing with, but I’m not writing to anything specific.

They have a little bit of movement, but for the most part, it was really about me just kind of creating a feeling and an emotion and then they find ways to react to that. And it’s always a fascinating process for me working with dancers because they hear things in the music that we usually don’t as musicians. Like there are so many times where a dancer will choreograph something to my piece and one thing that’s a very small, almost insignificant sound to me is incredibly important to them, and signifies a certain movement, or catalyzes a movement for them. And again, it’s just the collaboration thing that makes it so fascinating because you hear even your own music in a different way because of how somebody’s decided to set movement to it.

FJO: In terms of hearing things a different way, we talked a little bit about non-linearity and video games. But another thing I was struck by was Deconstructed Anthems. The music is foregrounded in that you’re not hearing anything else, but it’s part of a larger concept that’s a visual concept. And it’s not something people are necessarily hearing from start to finish in real time. It’s a sound installation, so that has a completely different way of interfacing with sound.

KB: That was an interesting project. What we did is take the national anthem and played it a number of times. I think it ended up being 15 times, and it was accompanied by this light installation that was reactive to sound. And so whenever sound was present, lights were on. And whenever sound was not present, the lights go off. And so the idea was that over those 15 repetitions of the national anthem, we would start removing notes by using an algorithm that the artist created. And we created all these rules as to why those notes were being removed, but they’re being removed at the rate of mass incarceration in the Black community over time.

And so basically, by the 15th time, we’re dealing with the highest percentage of incarcerated Black men because of whatever year we were using data-wise. But it also made it so that the anthem was completely silent or almost completely silent that last time. And the room we were in was completely dark because of the way the lights were reacting to it. I felt a bit nervous, messing around with the anthem is something that I think a lot of people take very personally. It’s very easy for people to think we’re making mistakes, because the notes are being removed at random. Basically the way it works is that we would feed these rules into the algorithm, every performance, so that it spits out a different version of the anthem. And then when we perform it, because those notes had been removed randomly, it feels like somebody’s taking scissors and just chopped up these different parts of the song. It just stops randomly in these different moments. And as the piece continues, it happens more and more frequently. And then it’s mostly silent, but watching people sit there for the 15 or 20 minutes that it took to go through that many iterations of it, it might even have been longer, I think maybe 30 minutes, it showed how much all those things coming together can create this profound emotional experience. We didn’t talk about what we were doing or why. We didn’t mention the mass incarceration aspect, or what the algorithm was doing. All we did was just perform it, and these lights were reacting to the performance. And people somehow were moved by hearing the sparseness of this anthem that is supposed to represent this country. It was a really, really special project to be a part of, for sure.

FJO: In a way, sort of the opposite of writing music for film. Because it’s so foreground that it’s about the process. It’s about these details. You might not necessarily know what’s behind it, but the more you hear it, the more you want to hear it; whereas, if you’re analyzing notes disappearing in a film score, you’re missing the story because you’re focusing too much on the music.

KB: Right. Yeah. Exactly. Yeah. Definitely. Very different.

FJO: I know you’re involved with five things now. You’re doing a score for film about Billie Holiday, which I’m very intrigued by because I love Billie Holiday. So I’m curious about how much her sound world gets into that score, and how you’re navigating that.

KB: Yeah. It’s been really interesting. Andra Day plays Billie and is really incredible, and Salaam Remi reproduced a lot of the Billie Holiday songs from the film. And for the score, it was kind of a little bit closer to my process for Green Book where there’s something about the feeling that I was trying to capture about Billie and the music isn’t very representative of her music. There’s a theme that’s inspired by “Strange Fruit,” that I think you can really hear, but other than that, the music is representing the emotional roller coaster that she was on dealing with the height of her career and how much of a star she was, and also how much of an incredibly strong woman she was, and powerful, but then at the same time, how she was a drug addict and was abused by most of the men in her life. And so finding ways to represent all of those things musically has been a journey.

FJO: I can’t wait to see it and hear it. Thank you so much for your time with us. This has been a wonderful window into your sonic world.

KB: Thanks for all the amazing questions.

https://soundcloud.com/new-music-usa/soundlives-kris-bowers-in-love-with-accompaniment

Follow New Music USA and others on SoundCloud.

Kris Bowers is among the humblest and most introverted composer/performers which is astounding considering his accomplishments—winning the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Piano Competition at 20, a daytime Emmy four years ago, and now one of the most in-demand composers for film and television, most recently scoring the popular Netflix series Bridgerton. And yet it all makes sense when you begin exploring Bowers’s incredible versatility, his openness to all genres of music, and hear how attuned his music is to whatever project he is working on--Kris Bowers creates music that is attuned to whatever project he is working on--whether it’s the score for the 2018 motion picture Green Book, the 2019 EA Sports videogame Madden NFL 20, the 2020 Phyllis Schlafly-inspired Hulu series Mrs. America, or the 2021 Netflix sensation Bridgerton.

Interview with Kris Bowers – DEAR WHITE PEOPLE, GREEN BOOK Composer | On The Fly Filmmaking

Popcorn Talk Network University, the online broadcast network that features movie discussion, news, interviews and commentary proudly presents “On The Fly Filmmaking (OTFF).

Marielou Mandl interviews filmmakers and artists, from different facets of the industry, and discuss their involvements with production. Here you will learn free tips and tricks of filmmaking that they do not teach you in film school, and then you too can produce a movie!

Host & Producer Marielou Mandl (@MarielouMandl) interviews Composer, Kris Bowers!

ABOUT KRIS BOWERS: Emmy-winning composer, Kris Bowers, scores compositions that step beyond the traditional boundaries of genre to form new and thrilling music. Bowers currently scores Netflix’s critically acclaimed “Dear White People,” and Shonda Rhimes’ “For The People,” starring Hope Davis. As a composer of color in network television, Bowers is in a small group of composers closing the diversity gap, and at 29 years old, stands as the youngest composer scoring a network TV show. Bowers recently wrote the music and lyrics for an original song featured as the main theme and end credits for “Madden NFL 19: Longshot,” the latest ‘story mode’ entry in the long-running “Madden” video game franchise, launching August 10. Earlier this year, Bowers scored the critically-acclaimed drama, “Monsters and Men” which premiered at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival, and is having its Canadian premiere in September at the Toronto International Film Festival before releasing in theaters October 5. He recently completed the score for Peter Farrelly’s latest drama, “Green Book,” starring Academy Award-winner Mahershala Ali and Academy Award-nominee Viggo Mortensen, in theaters November 21. In addition to scoring the film, Bowers was the piano-playing double for Ali and performed all the on-camera piano playing in the film. Bowers has scored a wide range of films including Amazon’s TV movie “The Snowy Day,” for which Bowers won a Daytime Emmy. He composed for “Elaine Stritch: Shoot Me,” starring Alec Baldwin and Tina Fey, “Seeds of Time,” “Play it Forward,” “Kobe Bryant’s Muse,” featuring Kobe Bryant, and “I Am Giant: Victor Cruz.” He also scored “Norman Lear: Just Another Version of You,” which premiered at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival, and “Little Boxes” which premiered at the 2017 Tribeca Film Festival and was purchased by Netflix. In addition to composing for film and television, Bowers has recorded and performed with artists such as Q-Tip, Aretha Franklin, Marcus Miller, José James, Ludacris, Christian Rich, Jay-Z, and Kanye West. He was commissioned by the Alvin Ailey dance company to create an original composition for “Untitled America,” a modern ballet piece that shines a light on the impact of the prison system on Africa-American families. The ballet was choreographed by Kyle Abraham, a MacArthur Genius Grant winner, with whom Bowers is a long-time collaborator. Furthermore, Bowers’ rich and eclectic sensibilities can be heard in his debut album with Concord Jazz, “Heroes + Misfits”, which opened at number one on the iTunes jazz chart. Bowers, a Juilliard-trained musician, has received numerous awards and accolades for his excellence in jazz performance. Bowers was one of 40 artists selected to perform at the White House for the 2016 International Jazz Day, hosted by President Barack and First Lady Michelle Obama. In 2011, he also won the coveted Thelonious Monk International Jazz Piano Competition at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, where Aretha Franklin picked Bowers as a favorite to win during the semi-finals concert. Moreover, he was named a Steinway Artist, one of twelve iTunes “Artists to Watch” and was one of six composers to participate in the Sundance Film Composers Lab at Skywalker Sound in 2015. Bowers resides in Los Angeles, CA.

Make sure to subscribe to Popcorn Talk! – http://youtube.com/popcorntalknetwork

HELPFUL LINKS:

Website – http://popcorntalk.com

Follow us on Twitter – https://twitter.com/thepopcorntalk

Merch – http://shop.spreadshirt.com/PopcornTalk/

ABOUT POPCORN TALK: Popcorn Talk Network is the online broadcast network with programming dedicated exclusively to movie discussion, news, interviews and commentary. Popcorn Talk Network is comprised of the leading members and personalities of the film press and community including E!’s Maria Menounos, Scott “Movie” Mantz, The Wrap’s Jeff Sneider, Screen Junkies and the Schmoes Know, Kristian Harloff and Mark Ellis who are the 1st and only YouTube reviewers to be certified by Rotten Tomatoes and accredited by the MPAA.

Marielou Mandl is a tech blogger, photographer, filmmaker and host with a healthy appetite for gadgets + glam. In addition to creating tech based content for her YouTube channel, she has produced photo/video content for clients such as Nickelodeon, HBO, Sesame Workshop, Nintendo, Cupcake Vineyards and more. When she is not playing with new gadgets or dancing in glitter, she can be seen as the host of her podcast On the Fly Filmmaking, featured on the hit online network Popcorn Talk.

Host & Producer Marielou Mandl (@MarielouMandl) interviews Composer, Kris Bowers!

ABOUT KRIS BOWERS: Emmy-winning composer, Kris Bowers, scores compositions that step beyond the traditional boundaries of genre to form new and thrilling music. Bowers currently scores Netflix’s critically acclaimed “Dear White People,” and Shonda Rhimes’ “For The People,” starring Hope Davis. As a composer of color in network television, Bowers is in a small group of composers closing the diversity gap, and at 29 years old, stands as the youngest composer scoring a network TV show. Bowers recently wrote the music and lyrics for an original song featured as the main theme and end credits for “Madden NFL 19: Longshot,” the latest ‘story mode’ entry in the long-running “Madden” video game franchise, launching August 10. Earlier this year, Bowers scored the critically-acclaimed drama, “Monsters and Men” which premiered at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival, and is having its Canadian premiere in September at the Toronto International Film Festival before releasing in theaters October 5. He recently completed the score for Peter Farrelly’s latest drama, “Green Book," starring Academy Award-winner Mahershala Ali and Academy Award-nominee Viggo Mortensen, in theaters November 21. In addition to scoring the film, Bowers was the piano-playing double for Ali and performed all the on-camera piano playing in the film. Bowers has scored a wide range of films including Amazon’s TV movie “The Snowy Day,” for which Bowers won a Daytime Emmy. He composed for “Elaine Stritch: Shoot Me,” starring Alec Baldwin and Tina Fey, “Seeds of Time,” “Play it Forward,” “Kobe Bryant’s Muse,” featuring Kobe Bryant, and “I Am Giant: Victor Cruz.” He also scored “Norman Lear: Just Another Version of You,” which premiered at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival, and “Little Boxes” which premiered at the 2017 Tribeca Film Festival and was purchased by Netflix. In addition to composing for film and television, Bowers has recorded and performed with artists such as Q-Tip, Aretha Franklin, Marcus Miller, José James, Ludacris, Christian Rich, Jay-Z, and Kanye West. He was commissioned by the Alvin Ailey dance company to create an original composition for “Untitled America,” a modern ballet piece that shines a light on the impact of the prison system on Africa-American families. The ballet was choreographed by Kyle Abraham, a MacArthur Genius Grant winner, with whom Bowers is a long-time collaborator. Furthermore, Bowers’ rich and eclectic sensibilities can be heard in his debut album with Concord Jazz, “Heroes + Misfits”, which opened at number one on the iTunes jazz chart. Bowers, a Juilliard-trained musician, has received numerous awards and accolades for his excellence in jazz performance. Bowers was one of 40 artists selected to perform at the White House for the 2016 International Jazz Day, hosted by President Barack and First Lady Michelle Obama. In 2011, he also won the coveted Thelonious Monk International Jazz Piano Competition at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, where Aretha Franklin picked Bowers as a favorite to win during the semi-finals concert. Moreover, he was named a Steinway Artist, one of twelve iTunes “Artists to Watch” and was one of six composers to participate in the Sundance Film Composers Lab at Skywalker Sound in 2015.

Bowers resides in Los Angeles, California

http://www.krisbowers.com

https://www.npr.org/2021/02/26/971058488/kris-bowers-reflects-on-coming-full-circle-in-composing-the-score-for-respect

Kris Bowers Reflects On Coming 'Full Circle' In Composing The Score For 'Respect'

Kris Bowers performs onstage during Soundcheck: A Netflix Film and Series Music Showcase on Nov. 4, 2019 in Los Angeles, Calif.

Kris Bowers' film-scoring career started, strangely enough, with a word of praise from the Queen of Soul — Aretha Franklin.

The 31-year-old composer has been tickling the ivories since he was a little kid, growing up in the Mid-City neighborhood of Los Angeles. He always loved film scores (E.T. was a heavy favorite), and he was one of the few Black students at his arts high school. He studied at Juilliard, and in 2011 he won the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Piano Competition.

That's when he met Aretha Franklin.

"She came to the semifinals," Bowers recalls. "Somebody was like, 'Would you mind meeting someone?' And as I'm getting out there, they're like, 'By the way, it's Aretha Franklin.' And I was like, okay, that's pretty ridiculous — and one of the only times I felt speechless in my life. She told me she enjoyed my playing, and then asked for my information. And maybe like a week or two later, she called me, you know, asked me what my plans were, and if I had any ideas about my next steps in my career."

Franklin's publicist became Bowers' first agent, and landed him his first film scoring gig: the 2013 documentary Elaine Stritch: Shoot Me. He had always planned on touring as a jazz pianist for many years after college, maybe start his own band, before transitioning into his dream of being a film composer — but Ms. Franklin, and the universe, had other plans.

Kris Bowers with Aretha Franklin.

"Some of that, I think, is even my own impatience," he says. "I went on tour for like two or three years, and I was like, man, I can't do this. I'm not made for this."

But he clearly was made for film scoring. Before he turned 30, Bowers composed the music for the documentary Muse for Kobe Bryant, the Justin Simien series Dear White People on Netflix, and the Oscar-winning film Green Book. The piano-playing hands in that film are actually his.

The appeal of this craft, he says, is "the alchemy of music and emotion and storytelling. I didn't necessarily like the attention of being on stage. I thought that was nice, but that wasn't the thing that gave me joy. The reason why I love being a pianist, especially in the jazz context, is because there are moments where I can maybe be featured — but most of the time I'm accompanying people."

His latest accompaniment is the score for The United States vs. Billie Holiday, starring Andra Day as the famous blues singer. One of the first things director Lee Daniels told his composer was that he doesn't care for jazz. (Bowers laughs when this gets brought up.) He wanted the score to juxtapose against the Holiday songs in the film, to express the character's interior.

There's a dreamlike montage where Holiday revisits a horrible lynching she witnessed as a little girl. Daniels had originally conceived the sequence being scored from a childlike perspective, but Bowers transformed it by "bringing the macabre." "I thought that the macabre was the cross, the macabre was the kids crying, the macabre was the woman hanging from the tree," Daniels says. "I thought that that was enough. I told him in the beginning to just try to lean into the childlike Billie. What would a child be like watching this? And he brought out the hauntingness of the childlikeness of it all."

Besides being a gentleman and a class act, Bowers is "uber smart," says Daniels. "It bleeds into his work, his sophistication. I think he has a sophisticated approach to his work that ordinary composers don't have."

Which is partly what drew director Ava DuVernay to him for the 2019 miniseries When They See Us, about the five boys wrongfully imprisoned for a murder in Central Park in 1989 (the year Bowers was born). Her Selma composer, Jason Moran, recommended Bowers knowing she specifically wanted a Black man for the job. "I felt like the experiences of the boys, and the environments in which they were raised and came up in, really lent itself to having as many crew people of likeminded experience as possible," DuVernay says.

She and Bowers "had deeply personal conversations about the things that we were seeing in the images," the director says. "He also brought a lot of his own feelings of being disconnected from the approval of the white gaze at different times. And so all of that made its way into the music."

DuVernay just hired Bowers again to score her Netflix series about Colin Kaepernick. She also produced a short documentary about Bowers, which he co-directed with Ben Proudfoot. On the surface, A Concerto is a Conversation is about the violin concerto Bowers premiered with the American Youth Symphony last spring at Walt Disney Concert Hall. But it's really about Horace Bowers — a man who fled Jim Crow Florida and hitchhiked to southern California, where he overcame a more invisible form of racism to become a successful business owner — and the "conversation" between two generations. The film premiered at Sundance last month, and it's on the Academy Awards shortlist.

"I saw the film," says DuVernay, "and was deeply moved by it, and just kind of awestruck by the simplicity of the idea. A conversation, you know, and the musicality of memory, and just taking some time to sit down and talk eye to eye, heart to heart. I mean, especially in this pandemic time where everything's so fragile, it just hit my heart."

The pandemic couldn't slow Bowers down — although he and his new wife (they got married under lockdown) both contracted COVID-19 in December. The composer recorded his music for both the Hulu series Mrs. America and the Netflix series Bridgerton with musicians piping in remotely, and he adjusted to the protocols and restrictions on the L.A. scoring stages for Billie Holiday. He's about to record the score for the Space Jam sequel starring LeBron James, which comes out this summer.

He already finished scoring another summer movie: Respect, the biopic about the late Aretha Franklin, played by Jennifer Hudson. Doing so was "really full circle, and actually somewhat emotional," Bowers says, "just kind of thinking about the things that I didn't really maybe even think about, interacting with her, that I now know about her life. I already had a respect for her as an artist, but I think just as a woman and as a human being, I have so much more respect and admiration for her after watching this film. And to not be able to express that to her is tough."

Bowers says he never forgot while composing the score that his film career started because Aretha Franklin liked the way he played piano.

https://filmmusicinstitute.com/interview-with-kris-bowers/

Interview with Kris Bowers

by Daniel Schweiger

Film Music Institute

In a well-intentioned Hollywood that preaches inclusivity while not often allowing all composers to play the band in its social justice march, Kris Bowers is continuing to make giant strides in telling stories that hear a commonality in its characters. If there’s any comparison in Bowers’ artistic growth, one could look to Quincy Jones, a jazz artist who transitioned to become one of film and television’s most in-demand artists decades ago, scoring films where his identity was often not even a consideration. Where that often hasn’t been the case for deserving musicians infinitely capable of playing who they aren’t, Bowers is a shiningly tuneful, and dramatic light in leading that charge without outrightly making it his destination.

Jamming with the likes of Kanye West, Marcus Miller and Jay Z, Bowers segued to albums, dance pieces and collaborating with Kobe Bryant. Yet Bowers’ film start was decidedly unique, and in a feminist groove as he accompanied a Broadway legend for the documentary “Elaine Stritch: Shoot Me.” Bowers heard the wily energy of another elder entertainment lion for “Norman Lear: Just Another Version of You” before getting his first fictional movie gig with the black family out of water in white suburbia for 2016’s “Little Boxes. He’d then score the cop shooting drama “Monsters and Men” and the documentary series “Religion of Sports.” But it was Bowers’ masterful channeling of the progressive jazz-classical chops of Dr. Donald Shirley in 2018’s Best Picture winner “Green Book” that really put him on the map. Though Bowers’ standout dramatic score for the 60’s set race-relations film somehow left on the nomination curb, Bowers was on his way – particularly with series work “For the People,” “Raising Dion,” “Dear White People, “Black Monday” and Ava Duvernay’s devastating vindication of The Central Park 5 with “When They See Us.”